Abstract

Radioanatomy, short for radiographic anatomy, is the study of anatomy through medical imaging. Its early‐stage introduction into medical curricula has been recommended in the literature. As with many other medical courses, it has seen a shift toward blended learning, including assessment on learning management systems such as Moodle, one advantage being automatic or at least assisted grading. The majority of previous studies in the realm of radioanatomy report only on the usage of multiple choice questions, due to several challenges related to computer‐based assessment. Nonetheless, we encourage radioanatomy teachers to include a more diverse set of question types. We consolidated the lessons learned during our experience over three academic years of carrying out summative assessments in radioanatomy courses on Moodle. Among others, we discuss technical aspects such as image optimization. Providing a lexicon for standardized answers fosters automatic grading. A student survey supports the idea of using stack visualizations for better image interpretation. We finally underline the importance of collaboration between different stakeholders to ensure a smooth assessment preparation, execution, and analysis. These findings offer valuable insights for improving e‐assessment in radioanatomy and potentially other medical courses.

Keywords: assessment, learning management system, radioanatomy

INTRODUCTION

Radioanatomy, short for radiographic anatomy, is the study of anatomy through medical imaging, such as X‐rays, CT scans, MRI, or ultrasound. A close relationship between clinical radiology and anatomy has been described. 1 In day‐to‐day practice, medical doctors encounter essentially two forms of anatomy: surface anatomy in physical exams and anatomy through radiological images. 2 Therefore, certain authors advocate for half of the curricular time for anatomy to be dedicated to radiology anatomy. 3

Introducing radioanatomy at an early stage in the medical curriculum enables students to understand the role of imaging in the patient's pathway and to learn the language to be used when requesting imaging or interpreting radiological reports. 1 According to Nagaraj et al., introducing radioanatomy already in the first year would increase interest in anatomy. 4 Introduction of radioanatomy or radiology content in undergraduate programs has been reported both for medical students 5 , 6 and dental students. 7 , 8 , 9 In the latter case, oral radiology allows for learning dento‐maxillomandibular radiographic anatomy 8 or diagnosing dental caries in panoramic images. 7

In recent years, enabled through technological advancements and certainly further accelerated by the COVID‐19 pandemic, radiology education has seen a push toward online solutions. 10 Such e‐learning approaches have been used in distance learning 8 or blended learning, 4 , 6 , 9 , 11 that is, classroom instruction combined with digital learning activities. Common features include theoretical explanations, image viewing, and assessment. These modules are often provided within a learning management system (LMS), such as Moodle, 7 , 8 , 11 Blackboard Learn, 6 , 12 , 13 or Canvas. 5

At the University of Luxembourg, radioanatomy is taught in the Bachelor of Medicine (three‐year undergraduate study program) in two dedicated French‐language courses in semesters 4 and 5. Of course, there are further semiology and pathology courses that integrate radiology content, alongside a physics course tailored to medical imaging, two anatomy and a neuroanatomy courses as well as an introduction to ultrasonography. The two radioanatomy courses were introduced in 2022, so they were never taught in a full distance learning setting, unlike courses affected by the lockdown of the COVID‐19 pandemic. In each session, classroom instruction comprises a theoretical introduction followed by practical exercises where students need to identify structures on medical imaging (X‐ray, MRI, CT scan, ultrasonography). 3D visualization of DICOM files is done on the Anatomage Table.*

Summative assessment at the end of our radioanatomy courses is conducted on Moodle. As mentioned by Gulati et al., oral exams become infeasible if there are few academic staff available. 5 There are several advantages to using an LMS for assessment in radioanatomy courses. First, grading can be automated or, for certain question types, at least assisted, which translates into less workload for teachers and fewer errors in grading. Next, an LMS can automatically calculate statistics that can be used for item analysis. Such metrics include the difficulty index and the discrimination index. 14 Finally, as radioanatomy exams often comprise a large number of images, a paper‐based exam would have a huge ecological footprint. On regular paper, image quality would be subpar, and high‐quality impression on glossy paper would be expensive and resource‐intensive. Laminated anatomical charts seem quite anachronistic in the digital age.

In particular, Moodle knows almost 160.000 registered sites at the time of writing.† It comes with different question types, such as multiple choice questions (MCQs), cloze (fill‐in‐the‐blanks), essay, matching, or drag‐and‐drop. You can specify an answering period, a time limit, the number of attempts, optional feedback to give to students, and shuffle the choices in MCQs. 7

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no article focusing on the challenges related to computer‐based assessment in radioanatomy courses. We consolidated the lessons learned during our experience over three academic years of carrying out summative assessment in radioanatomy courses on Moodle, hoping that they will be helpful to the interested reader.

DESCRIPTION

Lesson 1: Use a mix of question types

As previously mentioned, LMS typically support a variety of question types, such as multiple choice questions, cloze, or short answer questions. It is generally advised to compose exams by combining different question types and thereby addressing different depths of learning, such as recognition or recall. 15 However, the majority of studies in the realm of radioanatomy report using only MCQs. 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19

We use cloze questions mainly for annotation purposes. As shown in Figure 1, we would typically show one or several images (either from different anatomical planes or a stack), annotated with labels and arrows, and a form for students to fill in.

FIGURE 1.

Cloze questions for annotation purposes.

Lesson 2: Optimize images for the web

Medical imaging often comes in DICOM format, grouping underlying images in datasets, together with metadata, for example, the patient's identity or the date of the image taking. The underlying images are often in high resolution and large dimensions. 8 The images shown in the assessment should obviously still be of high quality, 1 but computer labs in universities typically do not have a higher resolution than Full HD (1920 × 1080 pixels), at least at the time of writing. For the sake of an assessment in radioanatomy courses, higher dimensions or zooming are typically not required. Howlett et al. proposed maximal dimensions of 1024 × 1024 pixels. The originals of the images used in our exams typically came in TIFF format, often in high dimensions such as 3182 × 1870 pixels. Using tools such as Adobe Photoshop, we converted them to PNG, a format which supports lossless compression as opposed to JPEG, and resized them to a maximum edge size of 2000 pixels. Finally, we use a service like TinyJPG‡ which optimizes compression to further reduce the file size. With this method, we start with a file of, for example, 23.8 MB and end up with a corresponding file size of 369 KB, so a reduction of 99%. We compare the original and final images to detect any significant quality loss, which typically was never the case considering their final usage on Moodle. It is evident that all personal data, both visible on the image or included in the metadata, need to be removed before any of these modifications and certainly before uploading the images on an LMS or a cloud service such as TinyJPG.

Lesson 3: Make labels unambiguous

If arrows, labels or numbering are put on top of an image, for example, to have students identify a structure, 8 make sure that these annotations are unambiguous. If several adjacent tissues have the same density, it might be unclear toward which an arrow is pointing. In case of superposition, for example, of bones, the question should also make it clear whether all structures should be mentioned.

Lesson 4: Benefit from automatic grading

The aforementioned popularity of MCQs in radioanatomy assessment might be due to its automatic grading through an LMS. However, creating high‐quality MCQs with plausible distractors is a non‐trivial task. Also, cloze questions showed to have a higher discriminatory power—at least in our case. On Moodle, cloze questions can also automatically recognize the correct answer by encoding it in the following syntax:

{1:SHORTANSWER:=Berlin} is the capital of Germany.

The part between curly braces will be presented as an empty text input. Its content is used for the automatic grading. The number 1 indicates the mark attributed in case of a correct answer. SHORTANSWER is the type of cloze field (as you could also propose a dropdown list). The correct answer (Berlin) is preceded by an equals sign (=). An optional feedback could be added to this automatic correction, which can be interesting in formative assessment settings. 20

This way, for each structure to be identified in our cloze annotation questions, the correct answer is already encoded in Moodle and recognized ….

Lesson 5: Double‐check automatic grading

… if the user has written the answer in the same way as the question author! While SHORTANSWER is case‐insensitive, there could be orthographic variations. Our radioanatomy courses are taught and assessed in French, a language making heavily use of letters with diacritics. If the correct answer expects diacritics (e.g., é) but the student wrote the plain letter without diacritics (e.g., e), the correct answer would not be recognized. It would be unfair to penalize students for this minor mistake. Hence, while automatic grading can help recognize correct answers, a human should still double‐check for such discrepancies.

Lesson 6: Provide a lexicon

In order to both benefit from automatic grading and reduce the discrepancies mentioned above and thereby the workload of manual changes in the grading by the teacher, we introduced a lexicon that students need to copy the responses from. The correct answers in the different cloze fields are written according to the lexicon. If students identify the correct structure and copy it from the lexicon, manual grading becomes almost unnecessary. It is worth mentioning that the solution needs to map to a single entry in the lexicon, that is, synonyms need to be avoided.

One could argue that a lexicon would assess recognition instead of recall. However, the lexicon in both courses includes 400 respectively 900 structures, far more than asked in the exam, such that students still first need to recall a structure labeled on an image, then search for it in the lexicon and finally copy the answer into the form. As shown in Figure 2, structures are separated into different body parts respectively systems. To ease the second step, that is, finding the identified structure in the lexicon, a filter field allows students to limit the entries.

FIGURE 2.

Excerpt from the lexicon.

Lesson 7: Use stack visualizations if needed

Showing a sequence of MRI or CT scan images in a vertical sequence, one below the other, is unnatural, as medical imaging viewers used in clinical settings also show them as a stack (commonly known as cine mode scrolling) to better appreciate the transversal nature of anatomical structures.

We developed Radiology Stack, a Web Component for visualizing medical imaging stacks. The images inside the question text on an LMS just need to be surrounded by the HTML tags <radiology‐stack> and </radiology‐stack>, and the radiology‐stack.js, available as an open source Web Component on GitHub,§ needs to be included. The result will be a scrollable stack. The first image will be shown on top, and subsequent images will be shown while the student scrolls through the stack. A toggle button allows to switch between the scrolling stack and the sequential visualization. We intend to use this Web Component in an upcoming radioanatomy exam, after checking its usability with students.

Lesson 8: Provide training with a sample question

If students should use a lexicon or any other help, such as a separate diagnostic imaging viewer 5 during a radioanatomy exam, we advise providing some training beforehand. This could take the form of a dummy cloze question in order to make them familiar with the type of questions and the way of working with the lexicon. To reduce the split‐attention effect, 21 we suggest students open the lexicon in a new window and place it next to the one with the Moodle quiz.

Lesson 9: Prepare a backup solution

We once had a student connected to a workstation whose screen was darker than others due to a hardware issue. As medical imaging is already quite dark, a screen with low brightness would give the student a disadvantage. Good image visualization is required by students. 16 Connecting to another workstation, if available, can be a workaround, but might also take a few moments. We recommend instructors to have the original, high‐quality images ready on their computer to assist in such a situation. This could also be helpful for students suffering from a vision impairment.

Lesson 10: Seek help from an instructional designer

Radiologists have a busy schedule outside the classroom, and the aforementioned preparatory work (optimizing images, encoding questions in the LMS, ensuring automatic grading, typesetting the lexicon) might be time‐intensive and require in‐depth technical knowledge. While the item writing and lexicon creation need to be done by the instructor to ensure optimal pedagogical alignment with the learning objectives, it is best to seek help from an instructional designer with a techno‐pedagogical background. This person can also liaise with the IT department of the university, for example, to ensure the server load is balanced. Due to the image‐rich nature of radioanatomy exams, even after image optimization, a huge memory usage on the server side can be caused, which should be tested before the exam takes place.

Lesson 11: Mind the invigilation gap

Invigilation during an exam is of utmost importance to avoid academic misconduct and fraud. It might be a good idea to prepare a randomized seating plan according to which students should be seated. In a computer room, it might be best to stand at the back of the room to get an overview of all screens. Furthermore, as in every exam, multiple invigilators should be present to be able to respond to student inquiries while others keep surveilling. Finally, if technically possible, it could be a good idea to whitelist domains that can be accessed on the workstations during the exam (namely the domain of the LMS) and block all other traffic to refrain students from consulting Google or ChatGPT.

Lesson 12: Review item quality

After the exam, it might be useful to review the quality of the different assessment items, for example, based on the difficulty and discrimination indices. The value of these metrics varies with the size of the class, though. Common misconceptions, ambiguous, or even miskeyed items can be identified and improved for an upcoming edition.

STUDENT SURVEY

We conducted an anonymous survey among 32 students. These students had already participated in the assessment of both radioanatomy courses, using the lexicon but without the stack visualization yet. The participation rate to this survey was 43.8%. The survey included 12 Likert items and 3 open questions on the types of questions used in the assessments, the image quality, the lexicon, the general impression of the exams, and the stack visualization.

Regarding the question types employed in the assessments (Figure 3), the variety was rated Good or Very good by 93% of the participants, while 71% agreed or strongly agreed that the different question types helped to demonstrate their knowledge effectively.

FIGURE 3.

Questions regarding the employed question types.

The quality of the used images was rated Good or Very good by 71% of the participants (Figure 4). Half of them considered the images to be clear and easy to interpret, and that the annotations helped to identify the structures.

FIGURE 4.

Questions regarding image quality.

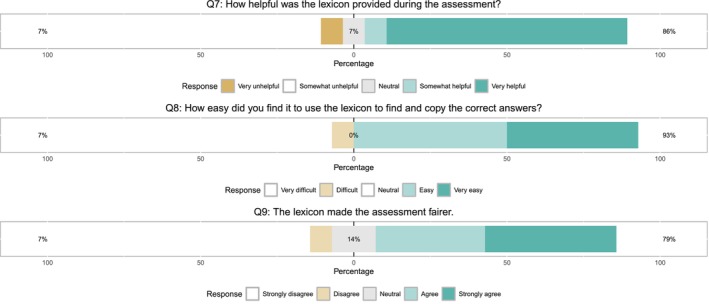

The lexicon was considered very helpful by 79% of participants (Figure 5). The same proportion agreed that the lexicon made the assessment fairer. 93% found its usage easy.

FIGURE 5.

Questions regarding the usage of the lexicon.

The perception of exam difficulty is balanced (Figure 6). 57% of participants considered the assessment to accurately reflect their knowledge and understanding of radioanatomy. 93% had a good or very good overall experience using Moodle for the radioanatomy exams.

FIGURE 6.

Questions regarding the general impression of the exam.

A demo video of the stack visualization was shown to the participants of the survey, as a suggestion for upcoming radioanatomy exams. 79% consider this proposal somewhat helpful or very helpful (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Question regarding the stack visualization proposal.

We asked participants which question type they found most challenging. 8 out of 11 responses mentioned questions with a long list of CT/MRI images. Students considered them time‐consuming and mentioned the risk of forgetting the number or the answer while scrolling. They also asked for the cine mode scrolling known from professional DICOM viewers. This was also the only technical issue that was identified. The third open question on suggestions for future assessment also saw five out of eight participants recommend the usage of the stack visualization.

DISCUSSION

We mentioned the importance of combining different question types in an assessment to address different depths of learning. The majority of studies in the realm of radioanatomy report to use only MCQs, but there are a few exceptions. Xiberta and Boada used questions where students needed to select a region or place a label or icon on a structure. 20 Similarly, Webb and Choi made use of drag‐and‐drop questions, selecting areas and cloze questions. 22 Seagull et al. proposed a dropdown list with 22 possible diagnoses from which students had to choose. 23 MCQs, drag‐and‐drop or dropdown lists foster recognition, whereas area selection or cloze questions assess knowledge recall. However, automatic correction for questions where a region needs to be selected or labels placed is error‐prone, as there is typically no possibility to indicate a tolerance distance. A few pixels next to the solution zone could be recognized as a mistake. In our case, we mainly used cloze questions, MCQs and a few short open questions. In our experience, cloze questions were more difficult than our MCQs, but not significantly so. However, they show a significantly higher discriminatory power (p < 0.001) compared to MCQs. As the results from the student survey showed, 71% agreed or strongly agreed that the different question types helped to demonstrate their knowledge effectively.

Given the diversity of question types used in our assessment, we can consider it to be more robust than exams limited to MCQs, a question type that presents an inherent risk to guessing and that fosters recognition over recall. Annotation questions better reflect students' knowledge, their logic, their critical thinking and deductive skills. As Hubbard et al. stated, open questions “provide a more authentic portrait of student thinking.” 24

The lexicon approach, less error‐prone with respect to automatic grading, was considered very helpful by 79% of participants, and 93% found its usage easy. Was it giving unknowledgeable students an advantage? We compared the difficulty index of cloze questions before and after the introduction of the lexicon in both radioanatomy courses. The difficulty index of cloze questions for the year where the lexicon was introduced was on average significantly lower than before, meaning less correct answers. Hence, the lexicon certainly did not make it easier, and it is unlikely that its introduction caused an additional difficulty either. We believe this phenomenon is correlated with the performance of the student population.

Student performance in the radioanatomy exams aligned with their performance in other subjects and with the teacher's impression during class: Students actively participating in class achieved the best results while students not going to class risked missing crucial information. Students struggling in class typically have lower results in the exam as well.

With regards to the medical imaging used in radioanatomy courses, including but not limited to assessment, it is of utmost importance to anonymize images before uploading them to any third‐party service or the LMS. No patient information should be shown on the image. Images sent inside a Word or PowerPoint document and cropped to hide the portion where patient information is written on give a false sense of security, as the full image can still be extracted. Proper cropping using a graphics editor is advised. Patient information could also be hidden in the metadata of an image or a DICOM file. Before sharing files outside the hospital, the medical doctor or imaging technician should make sure to remove any hidden or encrypted patient information. 1 The optimization steps we took did not hamper the quality, as confirmed by the student survey.

Using the proposed stack visualization to realize a cine mode scrolling experience for students during their assessment is definitely the most important item on our to‐do list for the next exam, as 79% of survey participants considered it helpful. Students mentioned that scrolling through a vertical list of many images led them to forget their answer for a certain label until reaching the answer form. One could argue that this is a form of the above‐mentioned split‐attention effect. The proposed stack visualization should reduce this, as the form would be immediately below the viewer, and scrolling would take place in situ. We consider our Web components approach to be even more lightweight and easy to set up, albeit limited in terms of features, as compared to integrating a full DICOM viewer into the LMS. 12

Compared to assessments in other subjects, where MCQs are the main question type, radioanatomy exams overall cause a bit more workload. The instructional designer has some overhead due to the preparation of the rather high quantity of images. Furthermore, he or she should ensure the recognition of the correct answers from the lexicon for each annotation question. This way, automatic grading is ensured. On the teacher's side, the creation of the lexicon takes a bit more time. In subsequent exams, only adaptations, if any, are necessary. In our experience, grading was significantly quicker, as the lexicon‐based approach improves the recognition of correct or wrong answers by the LMS by reducing answer ambiguity.

In the future, we also consider applying segmentation to images such that students could select requested structures. This could be more reliable than pin‐pointing on a single image, as the segmentation would go across multiple slices.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we covered the lessons learned regarding the assessment of radioanatomy courses on LMS, with a particular focus on Moodle. We have shown how teachers can integrate question types other than multiple choice while still benefiting from automatic grading through our lexicon‐based approach. The latter could be useful in any assessment involving questions related to anatomy or even histology. We shared our experience regarding technical aspects such as image optimization and finished on invigilation and item analysis. Preparing an e‐assessment in radioanatomy requires time and a close collaboration between the different stakeholders, notably the teacher and an instructional designer. In our experience, this resulted in smoothly running exams. We hope these hints will be helpful to other radioanatomy teachers.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Christian Grévisse: Conceptualization; software; writing – original draft; formal analysis; visualization. Françoise Kayser: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was received for this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all students who participated in the survey.

Biographies

Christian Grévisse, PhD, is an instructional designer in the Department of Life Sciences and Medicine at the University of Luxembourg. A computer scientist by training, his work focuses on the development and evaluation of e‐learning and e‐assessment tools. His current research interests revolve around the use of Large Language Models in simulation and assessment activities.

Françoise Kayser, MD, PhD, is Head of the radiology department at CHU UCL Namur, site Godinne, specialized in breast imaging, currently also a medical coordinator and radioanatomy teacher in the Department of Life Sciences and Medicine at the University of Luxembourg.

Grévisse C, Kayser F. Lessons learned from conducting assessments in radioanatomy courses on learning management systems. Anat Sci Educ. 2025;18:1004–1012. 10.1002/ase.70077

Footnotes

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Caswell FR, Venkatesh A, Denison AR. Twelve tips for enhancing anatomy teaching and learning using radiology. Med Teach. 2015;37(12):1067–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McHanwell S, Davies D, Morris J, Parkin I, Whiten S, Atkinson M, et al. A core syllabus in anatomy for medical students—adding common sense to need to know. Eur J Anat. 2007;11:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3. McLachlan JC, Patten D. Anatomy teaching: ghosts of the past, present and future. Med Educ. 2006;40(3):243–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nagaraj C, Yadurappa SB, Anantharaman LT, Ravindranath Y, Shankar N. Effectiveness of blended learning in radiological anatomy for first year undergraduate medical students. Surg Radiol Anat. 2021;43(4):489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gulati A, Schwarzlmüller T, du Plessis E, Søfteland E, Gray R, Biermann M. Evaluation of a new e‐learning framework for teaching nuclear medicine and radiology to undergraduate medical students. Acta Radiol Open. 2019;8(7):2058460119860231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howlett D, Vincent T, Watson G, Owens E, Webb R, Gainsborough N, et al. Blending online techniques with traditional face to face teaching methods to deliver final year undergraduate radiology learning content. Eur J Radiol. 2011;78(3):334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang HJ, Symkhampha K, Huh KH, Yi WJ, Heo MS, Lee SS, et al. The development of a learning management system for dental radiology education: a technical report. Imaging Sci Dent. 2017;47(1):51–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cruz AD, Costa JJ, Almeida SM. Distance learning in dental radiology: immediate impact of the implementation. Braz Dent Sci. 2014;17(4):90–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kavadella A, Tsiklakis K, Vougiouklakis G, Lionarakis A. Evaluation of a blended learning course for teaching oral radiology to undergraduate dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012;16(1):e88–e95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Biswas SS, Biswas S, Awal SS, Goyal H. Current status of radiology education online: a comprehensive update. SN Compr Clin Med. 2022;4(1):182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vavasseur A, Muscari F, Meyrignac O, Nodot M, Dedouit F, Revel‐Mouroz P, et al. Blended learning of radiology improves medical students' performance, satisfaction, and engagement. Insights Imaging. 2020;11(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burbridge B, Kalra N, Malin G, Trinder K, Pinelle D. University of Saskatchewan Radiology Courseware (USRC): an assessment of its utility for teaching diagnostic imaging in the medical school curriculum. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(1):91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salajegheh A, Jahangiri A, Dolan‐Evans E, Pakneshan S. A combination of traditional learning and e‐learning can be more effective on radiological interpretation skills in medical students: a pre‐ and post‐intervention study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tavakol M, Dennick R. Post‐examination analysis of objective tests. Med Teach. 2011;33(6):447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burrows S, Gurevych I, Stein B. The eras and trends of automatic short answer grading. Int J Artif Intell Educ. 2015;25(1):60–117. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buendía F, Gayoso‐Cabada J, Sierra JL. From digital medical collections to radiology training e‐learning courses. Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, TEEM'18. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery; 2018. p. 488–494. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Foran DJ, Nosher JL, Siegel R, Schmidling M, Raskova J. Dynamic quiz Bank: a portable tool set for authoring and managing distributed, web‐based educational programs in radiology. Acad Radiol. 2003;10(1):52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lewis PJ, Chen JY, Lin DJ, McNulty NJ. Radiology ExamWeb: development and implementation of a national web‐based examination system for medical students in radiology. Acad Radiol. 2013;20(3):290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marker DR, Bansal AK, Juluru K, Magid D. Developing a radiology‐based teaching approach for gross anatomy in the digital era. Acad Radiol. 2010;17(8):1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xiberta P, Boada I. A new e‐learning platform for radiology education (RadEd). Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2016;126:63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chandler P, Sweller J. The split‐attention effect as a factor in the design of instruction. Br J Educ Psychol. 1992;62(2):233–246. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Webb AL, Choi S. Interactive radiological anatomy eLearning solution for first year medical students: development, integration, and impact on learning. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7(5):350–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seagull FJ, Bailey JE, Trout A, Cohan RH, Lypson ML. Residents' ability to interpret radiology images: development and improvement of an assessment tool. Acad Radiol. 2014;21(7):909–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hubbard JK, Potts MA, Couch BA. How question types reveal student thinking: an experimental comparison of multiple‐true‐false and free‐response formats. CBE‐Life Sci Educ. 2017;16(2):ar26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.