Abstract

In vivo genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 systems is generating worldwide attention and enthusiasm for the possible treatment of genetic disorders. However, the consequences of potential immunogenicity of the bacterial Cas9 protein and the AAV capsid have been the subject of considerable debate. Here, we model the antigen presentation in cells after in vivo gene editing by in vitro transduction of a human cell line with an AAV2 vector that delivers the Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 transgene. Through HLA class I enrichment, peptide elution, and highly sensitive LC-MS interrogation, we identified a highly conserved saCas9-derived T cell epitope in the catalytic domain of the enzyme that is restricted to HLA-A∗02:01 and induces CD8+ T cell activation and killing. We conclude that AAV delivery of Cas9 results in presentation of a T cell epitope that can activate CD8+ cells and induce killing of the transduced cell, with important ramifications for in vivo genome editing strategies.

Keywords: CRISPR, gene editing, genome editing, immunogenicity, immunotoxicity, MHC I, class I

Graphical abstract

AAV delivery of the saCas9 gene results in the presentation of an HLA-A∗02:01-restricted T cell epitope, which induces potent T cell cytotoxicity and cell death. Mazor et al.’s findings highlight the immunogenicity risks associated with in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing and underline the importance of developing strategies to mitigate these immune responses.

Introduction

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-Cas9 technology offers solutions to many genetic illnesses that do not have any alternative therapies.1,2 While most trials involve ex vivo gene editing followed by cell transplantation into the patient, in vivo delivery of CRISPR genome editing components offers great advantages to indications with systemic and multi-organ presentation that could not benefit from ex vivo genome editing.

To deliver the Cas9 in vivo, some investigators use adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors, which takes advantage of the natural tropism of the AAV and specific promoters to target specific organs. The saCas9 is derived from the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and is considered a favorable enzyme in AAV-mediated genome editing due to its relatively small size and ability to fit within the AAV capsid.3 However, its bacterial origin poses a high risk for immunogenicity. Indeed, studies show that pre-existing adaptive immune responses to saCas9 have been detected in various levels in human samples,4,5 and experimental work in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) mouse model showed that administration of AAV-CRISPR was immunogenic in adult mice, though not in neonatal mice.6 In addition, the viral origin of the AAV vector also holds a risk for immunotoxicities. Deleterious capsid cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses have been involved in loss of efficacy and potentially liver toxicities.7,8

Recent evidence showed that CD8+ T cell response was elicited when immunizing mice with SaCas9 prior to the transduction of hepatocytes with AAV-CRISPR-Cas9 vector, resulting in hepatocyte apoptosis and failure of the genome editing procedure.9 Chew et al. reported that Cas9 expression in mouse muscles resulted in Cas9-driven lymphocyte infiltration in the muscle tissue and the draining lymph nodes.10 Mouse studies using other Cas enzymes showed similar observations that suggest loss of efficacy due to pre-existing antibodies and T cell immunogenicity.11 Overall, immunogenicity of the Cas9 transgene in AAV gene editing strategies may cause antibody-mediated or T-cell-mediated attack of the transduced cells that express the Cas9 protein, thus precluding the safety and efficacy of this promising system.

Here, we model the antigen presentation that may occur in target cells after in vivo genome editing by transducing a human cell line with an AAV vector that has saCas9 transgene. We employ human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I-associated peptide immunoprecipitation, peptide elution, and deep liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis and identify a novel T cell epitope derived from saCas9 when delivered via AAV vectors. We show that this epitope induces potent T cell killing of the transduced cells, indicating potential involvement in immune-related toxicities of this technology.

Results

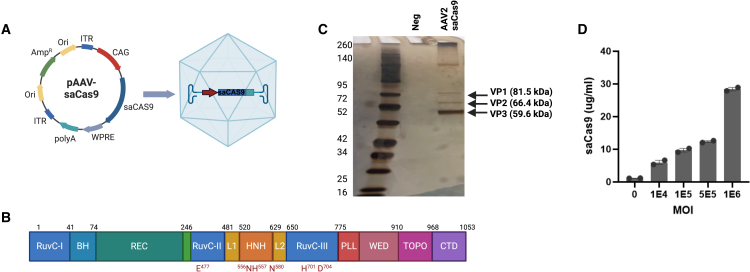

Design and manufacturing of AAV2-saCas9 results in effective transduction and high expression of saCAS9 protein

To introduce the saCas9 gene into AAV2, we synthesized and cloned the saCas9 gene into a parent plasmid pAAV-CAG-GFP, which contains two AAV2 ITRs, CAG promoter, WPRE sequence, and an SV40 poly(A) signal sequence (Figure 1A). The saCas9 transgene includes all structural domains of Cas protein (Figure 1B). Manufacturing of the new AAV vector resulted in a pure capsid, composed of VP1, VP2, and VP3 at the expected ratios of approximately 1:1:10 indicated by the band size in the silver stain gel (Figure 1C). To evaluate the transduction efficacy of AAV2-saCas9 in A375 cells and confirm production of sufficient amounts of saCas9 protein to support the mass spectrometric analysis, we transduced the cells with four MOIs and evaluated Cas9 expression using a specific saCas9 ELISA. Transduction of A375 cells with AAV2-saCas9 was effective and resulted in a dose-dependent production of saCAS9 (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Production of AAV2-saCas9 vector and transduction of saCas9 protein

(A) AAV2-saCas9 vector design includes two AAV2 ITRs, chicken beta actin promoter, WPRE enhancer, and an SV40 poly(A) signal. (B) Structural domains of saCas9. RuvC, crossover junction endodeoxyribonuclease; H, bridge helix; REC, recognition lobe; HNH, His-Asn-His endonuclease; L, linker region; PLL, phosphate lock loop; WED, wedge domain; TOPO, topoisomerase homology domain; CTD, C-terminal domain. (C) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE protein gel of a negative sample (PBS buffer) and AAV2-saCas9 after purification. The arrows denote the viral capsid proteins VP1 (87kDa), VP2 (72kDa), and VP3 (62kDa). (D) Dose-dependent quantification of saCas9 protein production using an ELISA, after transducing A375 cells for 72 h with four different MOIs (1e4-1e6). ELISA results in (D) repeated with similar trends in three independent experiments with two technical replicates each.

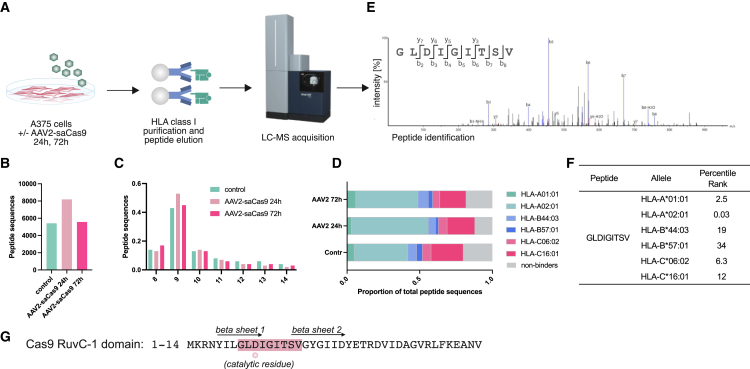

Interrogation of HLA presentation in AAV2-saCas9-transduced cells identifies an HLA-A∗02:01-restricted peptide encoded by the Cas9 gene

To model HLA class I transgene presentation after AAV gene therapy, A375 cells were transduced with AAV2-saCas9 for 24 or 72 h. HLA class I-peptide complexes were then immunoprecipitated, and peptides were eluted and analyzed using LC-MS (Figure 2A). We identified 5,017 peptides in the non-transduced cells and 7,892 and 5,195 peptides after 24 and 72 h of AAV2-saCas9 transduction, respectively (Figure 2B). Ninety-five percentage of the identified peptides were of a length of 8–14 amino acids (Figure 2C), as expected for HLA-associated peptide ligands. The A375 cell line expresses HLA-A∗01:01, A∗02:01, B∗44:03, B∗57:01, C∗06:02, and C∗16:01.12 We predicted the binding rank score for all peptides to all alleles present and assigned the HLA allele, resulting in the minimum rank score as the likely allele of origin. The overall proportion of 8–14mer peptides that were predicted to bind to an HLA allele were 79%, 88%, and 81% in samples 1, 2, and 3, respectively, confirming a high specificity of the experiment (Figure 2D). The predominant proportion of peptides were predicted to bind to A∗02:01 and C∗16:01 (Figure 2D). Although we did not identify peptides derived from the AAV2 capsid, we did identify a peptide that was prominent after 24 and 72 h transduction and originating from the saCas9 transgene (Figure 2E). Detection after 24 h indicates a rapid transduction, transcription, and translation from the AAV2-delivered transgene, followed by efficient antigen processing. In silico analysis of the HLA class I alleles in A375 cells predicted that this epitope is likely restricted by HLA-A∗02:01, and it suffices the amino acid requirements to A∗02:01 binding (Figure 2F).13 Further, HLA binding prediction showed that this epitope would be presented by all members of the HLA-A∗2 family that were evaluated. These alleles are prevalent in 49.5% and 54.2% of people in the United States and United Kingdom, respectively (Table S1).14 On the other hand, HLA binding prediction of this peptide to 27 HLA class I alleles with maximal population coverage15 did not identify other HLA class I alleles that may also be involved in presentation of this peptide (Table S2).

Figure 2.

Identification of a Cas9-derived, HLA∗02:01-restricted peptide in an in vitro AAV2 transduction model

(A) Workflow used to identify HLA-I binders to the saCas9 gene. A375 cells were treated with AAV2-saCas9 at an MOI of 1e4 for 24 and 72 h. Samples were harvested and processed, and eluted peptides were subjected to immunopeptidomics analysis. (B) Number of unique, HLA-presented peptide sequence identified in control cells and infected cells harvest after 24 and 72 h, as indicated. (C) Length distribution of eluted peptides. (D and E) Peptides stratified by their predicted alleles of origin, sorted by the lowest predicted rank score with NetMHCpan4.1. (E) LC-MS spectrum leading to identification of the target peptide GLDIGITSV in A375 after enrichment. N-terminal (b) and C-terminal (y) peptide fragment ions are indicated in the spectrum and numbered by their respective amino acid length. -H2O indicates the loss of a water molecule from the fragment ion. (F) NetMHCpan4.1 binding prediction for the saCas9-derived peptide indicating strong binding to HLA-A∗02:01. (G) Sequence of the RuvC-1 domain (amino acids 1–41) of saCas9; the location of the HLA-presented peptide identified is highlighted in red. Workflow was performed with three technical replicates and internal controls.

Importantly, peptide GLDIGITSV is spanning the active site of the RuvC-I nuclease domain within saCas9 (aspartate at position 3)16 (Figure 1G). The sequence is spanning both the beta 1 and 2 sheets forming the active site. This region is highly conserved, and an identical sequence is found in 37 different Cas9 from Roseburia inulinivorans, Lachnospiraceae bacterium, Alicyclobacillus hesperidum etc. (Table S3).

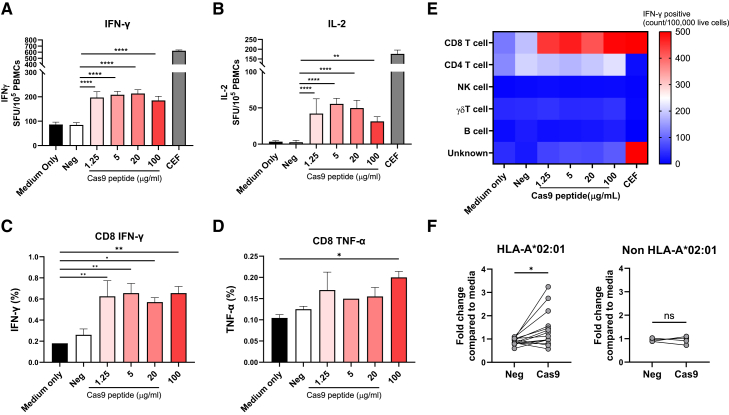

Peptide GLDIGITSV induces cytotoxic T cell activation in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

To evaluate if the peptide GLDIGITSV is a T cell epitope, we expanded peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HLA-A∗02:01-positive donors (Table S4) with peptide GLDIGITSV or an irrelevant peptide (negative peptide) and evaluated their response to peptide restimulation. PBMCs from donor #19 showed a statistically significant increase of 2.4- and 16-fold of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) secretion, respectively, compared to the negative peptide in ELISpot (Figures 3A and 3B). Intracellular cytokine staining of the PBMC from donor #19 showed similar results with a statistically significant fold increase of 3.5 in CD8+ cells that are IFN-γ positive, compared to untreated control (Figure 3C). Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) cytokine production in CD8+ cells was also statistically significantly increased, but only at the highest concentration of peptides (Figure 3D, gating strategy is shown in Figure S1).

Figure 3.

saCas9 peptide GLDIGITSV activates CD8+ T cells in A∗02:01 donors

(A and B) PBMCs from a healthy A∗02:01 donor were stimulated with either a negative (PGAPQPKAN) peptide or a saCas9 peptide (GLDIGITSV) and expanded for 10 days. Cells were re-stimulated with 10 μg/mL of negative peptide (neg), various doses (1.25, 5, 20, and 100 μg/mL) of Cas9 peptides, or a positive CEF peptide pool control in ELISpot plates coated with antibodies for IFN-γ (A) and IL-2 (B). (C–E) Immunophenotyping of the expanded PBMC using intracellular staining of IFN-γ (C) and TNF-α (D) using flow cytometry in CD8+ T cells or all PBMCs (E). (F) PBMCs from 14 healthy A∗02:01 donors and 4 non-A∗02:01 donors were stimulated with either a negative (PGAPQPKAN) peptide (neg) or a Cas9 peptide and expanded for 10 days. Cells were re-stimulated with 20 μg/mL of negative peptide or Cas9 peptide. Each bar shows the mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. p values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or paired t test (F). SFU, spot-forming cells. Each experiment in (A, B, C, D, and E) was repeated in at least two independent experiments with similar results.

To identify cells that responded to peptide stimulation and produced cytokines, the absolute number of each subset after gating on the cytokine-secreting cells was analyzed. CD8+ T cells were the main cells activated by the peptide (Figure 3E), indicating that epitope GLDIGITSV is restricted to CD8+ T cells. Next, PBMC samples from 14 HLA-A∗02:01-positive donors (Table S4) were evaluated for IFN-γ secretion, similarly to the approach in Figure 3A, and showed significant activation in most samples (Figure 3F). On the other hand, donors that were HLA-A∗02:01 negative did not show any IFN-γ activation, further demonstrating that HLA-A02::01 presentation is required for cell activation with the peptide.

Peptide GLDIGITSV induces T-cell-mediated killing of transduced A375 cells

To show that peptide GLDIGITSV induces not only T cell activation but also T-cell-mediated killing, we expanded PBMC from donor #19 with the peptide and tested if the expanded cells kill cells that are transduced with saCas9 gene. A375 cell line that stably expresses red fluorescent protein (RFP) was transduced with AAV2-saCas9 and co-cultured with expanded PBMC for 10 days (Figure 4A). To evaluate cell killing, the effector T cells were washed out and the target cells assessed for viability using CellTiter-Glo. We found that the target cells in the co-culture had a low viability, especially in the high ratios of target to effector cells, which was lower than the co-culture of T cells with negative peptide or no peptide (Figure 4B). Digital microscope confluency measurements showed a decreased cell confluency after 72 h of co-culture (Figures 4C and 4D). Similar cell death and growth inhibition are shown (Videos S1, S2, and S3), demonstrating enhanced cell death after 72 h of co-culture with the peptide-educated T cells. Intracellular cytokine analysis by flow cytometry of the T cells in the co-culture showed that the T cells developed an activated killing phenotype with a 3-fold increase in Ki67 proliferation markers compared to the negative peptide (Figure 4E), as well as a 2- to 3-fold increases in granzyme B and perforin expression (Figure 4F). This finding indicates that peptide GLDIGITSV induces CD8+ T-cell-mediated cytotoxic activity and causes cell death of target cells expressing saCas9.

Figure 4.

saCas9 peptide GLDIGITSV activates CD8+ T cells-mediated killing via AAV transduction

PBMCs from a healthy A∗02:01 donor were expanded with either a negative peptide or a Cas9 peptide for 10 days. CD8+ T cells were isolated from both groups and co-cultured with A375 cells that express RFP and were transduced 72 h earlier with AAV2-saCas9. (A) Schematic demonstration of the cell killing assay with A375 RFP-expressing cells. (B) Cell viability of target cells relative to untreated or negative peptide was measured using CellTiter-Glo viability assay. (C) Cell confluency percentages of AAV2-saCas9-transduced A375 cells after co-culture with T cells that were expanded with negative peptide or Cas9 peptide measured by Incucyte S3 platform. (D) Representative images of A375 cells after 72 h of co-culture were obtained via Incucyte S3. (E and F) Intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry analysis of CD8+ T cell activation measured by Ki67 expression, and (F) detection of perforin and granzyme B after gating on CD8+ cells in the coculture at 24 h. Each bar shows the mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. p values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Each experiment was repeated in two independent experiments, which were set up on the same day and run by two different technicians.

Peptide GLDIGITSV induces T-cell-mediated killing of HeLa A∗02:01 cells

To show that T cell killing is mediated by HLA-A02::01, cytotoxic activity was evaluated in co-cultures of HeLa A∗02:01-positive cells that were previously engineered to exclusively express monoallelic HLA-A∗02:01. Target cells were pulsed with GLDIGITSV or negative peptide and co-cultured for 72 h (Figure 5A). Similarly to the A375 cells, co-culture of peptide-pulsed HeLa A∗02:01 cells with the expanded CD8+ T cells resulted in striking cell killing; cell viability was reduced by 87% (Figure 5B), and cell confluency was reduced by 66% (Figure 5C). Similar cell death and growth inhibition are shown in Figure 5D and Videos S4, S5, and S6 by labeling the cytoplasm of the target cells with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) prior to co-culture. T cells in the co-culture showed a 2-fold increase in Ki67 proliferation markers compared to the negative peptide (Figure 5E) and 2-fold increase of granzyme B and perforin expression (Figure 5F). This further confirms that peptide GLDIGITSV is an HLA A∗02:01-restricted epitope that induced T-cell-mediated killing.

Figure 5.

saCas9 peptide GLDIGITSV activates CD8+ T cells-mediated killing via HLA-A02::01

PBMCs from a healthy A∗02:01 donor were expanded with either a negative peptide or a Cas9 peptide for 10 days. At day 10, CD8+ T cells were isolated from both groups and co-cultured with HeLa A∗02::01 target cells that were pulsed with the Cas9 peptide for 3 h and labeled with CFSE. (A) Cell killing assay designed with HeLa CFSE-expressing cells. (B) Viability of target cells relative to untreated or negative peptide was measured using CellTiter-Glo viability assay. (C) Cell confluency percentages of HeLa A∗02:01 cells of untreated, negative peptide and saCas9 peptide were measured by Incucyte S3. (D) Representative images of HeLa A∗02:01 cells stained with CSFE after 72 h of Cas9 peptide, negative peptide, and untreated co-cultures obtained via Incucyte S3. (E and F) Intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry analysis of CD8+ T cell activation measured by Ki67 expression, and (F) detection of perforin and granzyme B after gating on CD8+ cells in the coculture at 24 h. Each bar shows the mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. p values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Each experiment was repeated in two independent experiments, which were set up on the same day and run by two different technicians.

Discussion

In vivo genome editing using CRISPR-Cas9 technology is a promising approach to address rare genetic disorders that have not had cures until now. Due to the bacterial origin of the Cas9 gene, it has immunogenicity risks and challenges that have not yet been investigated in humans. Here, we show for the first time that AAV delivery of Cas9 protein results in presentation of a T cell epitope that can activate CTL response, inducing killing of the transduced cell.

We modeled the antigen presentation that may occur in cells after in vivo genome editing by transducing a human cell line with an AAV vector that has an saCas9 transgene. Using immunopeptidomics, we identified a novel T cell epitope in saCas9 that is restricted to HLA-A∗02:01 and showed that this epitope has a strong ability to activate CTL response and kill human cell lines that were transduced with AAV via granzyme B-mediated cytotoxicity. Interestingly, the epitope is located at the active site of the RuvC-I nuclease domain in saCas9 (Figure 1B) and is highly conserved across more than 30 different bacteria (Table S3). This is a prime example of the evolutionary arms race between hosts and pathogens, in which the HLA binding pocket is strongly aligned to present a highly conserved region that is critical for enzyme activity and bacterial survival. This epitope has recently been described by Raghavan et al.17 as the strongest T cell epitope in HLA-A∗02:01-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with a plasmid expressing SaCas9. It remains unclear how well our ex vivo CTL activation and in vitro cell-line-based toxicity model can recapitulate the immune response and immunotoxicity of saCas9 delivery by AAV. Future work using in vivo models is needed to show the impact of this T cell epitope or similar CTL epitopes on the immunotoxicity and efficacy of gene-editing-based therapeutic. The fact that the same immunodominant epitope was identified by Raghavan et al. and us using different transduction systems and different cell lines further confirms the validity of this epitope. Future work is needed to confirm if the dominance of the epitope remains with additional vectors such as lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) or lentiviral systems.

Among all Cas9 systems, saCas9 is the most prevalently used for in vivo AAV-delivered genome editing owing to its small size (compared to spCas9) and its efficacy. Therefore, identification of T cell epitopes in this protein provides valuable information for immunogenicity mitigation strategies such as peptide tolerance induction18 and engineering next-generation enzymes with reduced immunogenicity.16 To this end, we used in silico analysis (IEDB class I prediction) to predict every possible substitution in each possible position within the epitope (Figure S3). We identified more than 10 substitutions or deletions that are predicted to result in elimination of this epitope. Indeed, Raghavan et al. used proprietary computational designs and identified three mutations (V16A, L9A, and L9S) for immunogenicity mitigation.17 These three mutations were also highlighted in our analysis (Figure S3), although the predicted binding of V16A was lower than the other two mutations according to our analysis, suggesting lower immunogenicity reduction by V16A. Alternative approaches to immunogenicity mitigation may include immune suppression, immune tolerance induction, or use of alternative genome editing strategies.

This epitope is highly conserved and is present in many Cas9 proteins in other bacteria. Therefore, the elimination of this epitope will be applicable to CRISPR systems other than saCas9. Notably, Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, which is frequently used in ex vivo genome editing, shares only 78% alignment (GLDIGTNSV) with the epitope identified in our study. This may explain why this epitope was not found in T cell analysis of studies investigating spCas9.16 Our study focused on a restricted epitope to the HLA-A∗2 family. Similar work can be done with more cell lines representing more HLAs to identify more epitopes and provide higher population coverage.

Simhadri et al. identified helper T cell epitopes in saCas9.19 Their study included exogenous loading of saCas9 to dendritic cells and detection of HLA-class II-presented peptides that can activate CD4+ helper T cells. Such epitopes are expected to be involved in B cell help in a T-dependent immune response in which the cytokines secreted by the T cell help the B cell undergo class switching for robust antibody responses (also known as TH2 response). Alternately, CD4+ epitopes can help create a supportive immunological milieu for a cellular T cell response (also known as TH1 response). However, CD8+ T cell epitopes are the drivers of cytotoxic immune response and not CD4+ helper T cell epitopes. To identify the CD8+ T cell epitopes that activate cytotoxic immune responses, we needed to modulate the endogenous immune pathway that is expected to occur after in vivo delivery of CRISPR Cas9. In this model, the cells were transduced by the AAV with the saCas9 gene and produce the saCas9 enzyme endogenously in the cell, modeling with high accuracy the AAV or LNP in vivo delivery of genome editing. Therefore, the GLDIGITSV epitope described herein is the first human saCas9 cytotoxic T cell epitope that may be involved in immune toxicities or loss of efficacy in such modes of therapy. Of note, the GLDIGITSV epitope does not overlap with any of the CD4 epitopes described in sequence comparison of the CD4 epitopes described by Simhadri.19

The cell killing ability of T cells that were expanded with GLDIGITSV peptide was significantly higher than cells expanded with an irrelevant peptide derived from AAV9 capsid (Figures 4 and 5) or than cells expanded with no peptide (not shown). Though not statistically significant, some killing activity was noted in the cells expanded with the negative peptide, particularly in the high effector ratios. This is probably a side effect of the in vitro expansion process or presentation of mismatched HLA between the cell line and the PBMC.

The natural pathogenic pathway of the Staphylococcus aureus infections is exogenous and therefore, should have a strong CD4 response, but not necessarily CD8. Therefore, it is not surprising that our investigations only identified a single CD8 epitope in saCas9. Nevertheless, the presence of a cytotoxic epitope that demonstrates killing ability indicates the risk for potential-treatment-mediated toxicity and loss of efficacy. Additional work with cell lines that have HLAs other than A375 (Figure 2D) will likely reveal additional epitopes.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human epithelial cell line A-375 (ATCC) was cultured in DMEM (Fisher, #10569044) with penicillin (100 IU/mL, Sigma), streptomycin (100 μg/mL, Sigma), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma) and were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2. HeLa-A∗02:01 cells (a gift from Drs. David Margulies and Kannan Natarajan of NIAID) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium (RPMI; Thermo Fisher) with penicillin (100 IU/mL, Sigma), streptomycin (100 μg/mL, Sigma), and 10% FBS (Sigma) and were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Cloning of pAAV-CAG-GFP plasmid

The gene sequence for saCas9 was obtained from the genebank (AXB99496.1) and synthesized and cloned into a parent plasmid pAAV-CAG-GFP, which contains two AAV2 ITRs, a hybrid CMV enhancer and chicken beta actin promoter, WPRE sequence, and an SV40 poly(A) signal. pAAV-CAG-GFP was a gift from Edward Boyden (Addgene plasmid #37825; http://n2t.net/addgene:37825; RRID:Addgene_37825). The EGFP gene in the parent plasmid was replaced with the saCas9 gene (Figure 1A).

Production and purification of AAV vectors

The AAV2-saCas9 vector was manufactured according to a laboratory protocol as previously described.20 Suspension HEK293 Viral Production Cells 2.0 were transduced with three plasmids: saCas9 plasmid (described above), pAAV2/2 RepCap (Addgene #104963), and a pHelper plasmid (Cell Biolabs #340202).

Quantification of AAV2-saCas9

Quantification of the AAV viral genome was performed by TaqMan (qPCR) as previously described20 using the following primers that target the AAV2 ITR: ITR (forward: 5ʹ-CGGCCTCAGTGAGCGA-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ- GGAACCCCTAGTGATGGAGTT-3ʹ). The targets were amplified using SsoAdvanced Universal Probes Supermix (1,725,281, Bio-Rad), and thermocycling conditions were 3 min at 95°C and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 58°C for 30 s on a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ Multicolor Real-Time PCR Detection System.

Evaluation of vector purity using SDS-PAGE and silver staining

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed using 4%–12% Bis-Tris gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the gel was loaded with a total volume of 40 μL that contains 20 μL of AAV, 10 μL of resuspension buffer, and 10 μL of 4× purple dye sample buffer. VP1 (87 kDa), VP2 (73 kDa), and VP3 (62 kDa) were detected with fast silver staining to assess the purity of viral preparations.

CRISPR-saCas9 ELISA assay

Quantification of expressed saCas9 transgene in A375 cells was done according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Epigentek #P-4062). Briefly, cells were treated in a 24-well plate at a density of 1e5cells/mL and treated with AAV2-saCas9 at four different MOIs (1e4 to 1e6 viral genomes per cell). At 72 h, cells were harvested by trypsinization and lysis using RIPA buffer (Fisher, #PI89900) and protease inhibitors (Sigma, #11836170001), and total protein in whole-cell extract was quantified using a nanodrop. Equal protein levels of each sample were added onto the pre-coated plates in duplicates. The amount of whole cell extract for each assay can be between 0.5 μg and 5 μg with an optimal range of 1–2 μg. Plates were read using a GEN5 microplate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm. The concentration of saCas9 in each sample was interpolated from a standard curve.

AAV transduction of A375 cells

A375 were expanded in T175 flasks in complete DMEM media (described above). Prior to transduction, cells were seeded in 24 cm cell culture trays at a concentration of 1E6 cells/mL for 24 h. Prior to AAV transduction, media was aspirated and replaced with incomplete DMEM media (with no serum or antibiotics) to improve transduction. Cells were then transduced with AAV2-saCas9 at an MOI of 1E4 for 24 or 72 h. Media was replaced 24 h post-transduction with complete DMEM. Cells were harvested by scraping the culture tray, and pellet was collected, frozen, and shipped for immunopeptidomics analysis.

HLA enrichment and peptide purification from A375 cells transduced with AAV-saCas9

AAV-transduced cell pellets (5∗107 cells) were lysed in 1 mL/109 cells lysis buffer (0.5% Igepal, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 1x Roche Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, EDTA-free) for 30 min on ice, before pelleting and removing the nuclei at 300 g for 10 min and clearing the lysates at 21,000 g for 45 min at 4°C. pHLA complexes were captured with anti-HLA-class I W6/32 antibody cross-linked to Sepharose A beads (preparation previously described21) overnight at 4°C. The resign was collected though gravity flow and washed 4x with 50 mM Tris buffer containing 400 mM NaCl, 150 mM NaCl, and finally no salt. Peptides were eluted from the captured HLA complexes with 10% acetic acid. Peptides were then further filtered through a 5 kDa cutoff filter (Merck Millipore #UFC3LCCNB-HMT) and the flow-through vacuum dried. Eluted peptides were resuspended in 10 μL 1% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA in water prior to mass spectrometry analysis.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Samples were acquired with the nanoElute liquid chromatography system (Bruker) coupled to a timsTOF SCP mass spectrometer (Bruker). Peptides were loaded onto an Aurora C18 column, 25 cm × 75 μm, 1.7 μm particle size (IonOptics) and separated by applying a linear gradient of 2%–25% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid over 60 min at a flow rate of 150 nL/min. The column was heated to 50°C. Peptides were ionized with the CaptiveSpray source (Bruker) at 1,400 V and 180°C. Data were acquired in DDA PASEF mode with one TIMS-MS survey and 10 PASEF MS2 scans per cycle. Ion accumulation and ramp time in the TIMS analyzer were set to 166 ms/each. The ion mobility range for peptide analysis was set to 1/K0 = 1.7 to 0.7 Vs/cm2, and the m/z range was 100–1,700. Precursors with charge states 1–3 and a minimum threshold of 500 arbitrary units (AU) were fragmented and re-sequenced until reaching a “target value” of 20,000 AU. Collision energies were 70 eV at 1/K0 = 1.7 Vs/cm2; 40 eV at 1/K0 = 1.34 Vs/cm2; 40 eV at 1/K0 = 1.1 Vs/cm2; 30 eV at 1/K0 = 1.06 Vs/cm2; and 20 eV at 1/K0 = 0.7 Vs/cm2.

Mass spectrometry data analysis

Analysis of the raw data was performed with Peaks XPro (Bioinformatics Solutions), applying a de-novo-assisted peptidomics workflow with a database consisting of the UniProt referenced proteome (SwissProt) from 06/03/2023, with saCas9 (entry J7RUA5) and a 6-frame translation of the Addgene plasmid #37825 proteome appended. Searches were conducted allowing one variable post-translational modification per peptide, including cysteinylation on cysteine, deamidation of glutamine and asparagine, and oxidation on methionine residues. Mass tolerance was set to 20 ppm for peptide precursors and 0.02 Da for fragment ions. The false discovery rate was set to 1%, as evaluated through a software internal control search of a randomized appended database. Peptide-HLA binding was determined using MHCMotifDecon 1.0.22

PBMC isolation and HLA typing

PBMCs were isolated from apheresis samples under protocols approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board (CBER-047) as previously described.20

In vitro expansion of PBMCs

PBMCs from A∗02:01 donors were thawed, washed, counted, and resuspended at a concentration of 2E6 cells/mL in RPMI media containing 5% heat-inactivated human serum, 1% Glutamax (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 mM HEPES (Thermo Fisher Scientific), MEM non-essential amino acids (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were cultured with a mixture of two peptides: an irrelevant peptide (PGAPQPKAN) used as a negative control and saCas9 (GLDIGITSV) peptides at a final concentration of 1 μg/mL. The negative peptide is derived from the capsid of AAV9 and was predicted to have low binding to HLA-A02::01. Cells were supplemented with fresh assay medium containing 20 units of IL-2 (MilliporeSigma), 5 μg/mL of IL-7 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), and 25 μg/mL of IL-15 (BioLegend) every 3–4 days.

ELISpot assay

IFN-γ secretion following stimulation with individual peptides was assayed using an ELISpot assay according to manufacturer’s recommendations (Mabtech). After cell expansion, cells were harvested, washed, and plated in ELISpot plates that were pre-coated with anti-human IFN-γ antibodies. Cells were re-stimulated with peptides and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Internal positive controls were treated with either CEF or phytohemagglutinin (PHA, MilliporeSigma). Spot detection and enumeration were performed as previously described.20

Flow cytometry

Expanded cells were harvested, washed, and re-stimulated with individual peptides for 24 h at 37°C. Cytokine secretion in cell cultures was blocked by the addition of GolgiPlug/GolgiStop (BD Biosciences ) for 4 h prior to cell harvesting and staining. Afterward, cells were washed and stained for surface markers CD3 (clone UCHT1), CD4 (clone SK3), CD8 (clone RPA-T8), CD19 (SJ25C1), CD56 (clone HCD56), and TCRγδ (clone 11F2). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) followed by intracellular staining for cytokines using antibodies against IFN-γ (clone B27) and TNF-α (clone MAb11). Acquisition was performed using a Cytek Aurora (Cytek Biosciences, Fremont, CA), and analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

CD8+ T cell killing assay

PBMCs from A∗02:01 donors were expanded with peptide GLDIGITSV or a negative peptide as described above. After 10 days of expansion, cells were harvested and CD8+ T cells were isolated using magnetic bead positive selection (Miltenyi biotech #130-097-057). CD8+ cell purity >90% was confirmed by flow cytometry. One day prior to PBMC harvest, RFPs expressing A375 cell line and HeLa A∗02:01 cell line were transduced with AAV2--saCas9 at an MOI of 1E4 or pulsed with peptide GLDIGITSV or a negative peptide. On the day of PBMC harvest, CD8+ cells were introduced to the AAV-transduced or -pulsed cell lines at various effector-to-target ratios. Cells were monitored using live cell imaging (Incucyte, Sartorius) and after 72 h, and cell viability was assessed using CellTiter-Glo (Promega #G9242) and Ghost Dye Red 780/Calcein AM (Cytek Biosciences #13-0865-T100).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, v.10.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplemental information.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Margulies and Dr. Kannan Natarajan from NIAID for providing HeLa-A∗02:01 cells, Dr. Zhaohui Ye and Dr. Michael Norcross for reviewing and providing helpful comments on the manuscript, and Dr. Takele Argaw for providing scientific mentorship. This project was supported by an appointment to the ORISE Research Participation Program at the CBER, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and FDA.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, S.N., R.M., and N.T.; methodology, S.N., A.N., S.J.B., and A.M.S.; supervision, R.M. and N.T.; writing, S.N., R.M., and N.T.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2025.101506.

Contributor Information

Nicola Ternette, Email: nternette001@dundee.ac.uk.

Ronit Mazor, Email: ronit.mazor@fda.hhs.gov.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J.A., Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li T., Yang Y., Qi H., Cui W., Zhang L., Fu X., He X., Liu M., Li P.F., Yu T. CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics: progress and prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023;8:36. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01309-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helfer-Hungerbuehler A.K., Shah J., Meili T., Boenzli E., Li P., Hofmann-Lehmann R. Adeno-Associated Vector-Delivered CRISPR/SaCas9 System Reduces Feline Leukemia Virus Production In Vitro. Viruses. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/v13081636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simhadri V.L., McGill J., McMahon S., Wang J., Jiang H., Sauna Z.E. Prevalence of Pre-existing Antibodies to CRISPR-Associated Nuclease Cas9 in the USA Population. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018;10:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cearley C.N., Vandenberghe L.H., Parente M.K., Carnish E.R., Wilson J.M., Wolfe J.H. Expanded repertoire of AAV vector serotypes mediate unique patterns of transduction in mouse brain. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1710–1718. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson C.E., Wu Y., Gemberling M.P., Oliver M.L., Waller M.A., Bohning J.D., Robinson-Hamm J.N., Bulaklak K., Castellanos Rivera R.M., Collier J.H., et al. Long-term evaluation of AAV-CRISPR genome editing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Med. 2019;25:427–432. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0344-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mingozzi F., Maus M.V., Hui D.J., Sabatino D.E., Murphy S.L., Rasko J.E.J., Ragni M.V., Manno C.S., Sommer J., Jiang H., et al. CD8(+) T-cell responses to adeno-associated virus capsid in humans. Nat. Med. 2007;13:419–422. doi: 10.1038/nm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mingozzi F., High K.A. Therapeutic in vivo gene transfer for genetic disease using AAV: progress and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:341–355. doi: 10.1038/nrg2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li A., Tanner M.R., Lee C.M., Hurley A.E., De Giorgi M., Jarrett K.E., Davis T.H., Doerfler A.M., Bao G., Beeton C., Lagor W.R. AAV-CRISPR Gene Editing Is Negated by Pre-existing Immunity to Cas9. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:1432–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chew W.L., Tabebordbar M., Cheng J.K.W., Mali P., Wu E.Y., Ng A.H.M., Zhu K., Wagers A.J., Church G.M. A multifunctional AAV-CRISPR-Cas9 and its host response. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewaisha R., Anderson K.S. Immunogenicity of CRISPR therapeutics-Critical considerations for clinical translation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1138596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boegel S., Löwer M., Bukur T., Sahin U., Castle J.C. A catalog of HLA type, HLA expression, and neo-epitope candidates in human cancer cell lines. OncoImmunology. 2014;3 doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.954893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynisson B., Alvarez B., Paul S., Peters B., Nielsen M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:W449–W454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Galarza F.F., McCabe A., Santos E.J.M.D., Jones J., Takeshita L., Ortega-Rivera N.D., Cid-Pavon G.M.D., Ramsbottom K., Ghattaoraya G., Alfirevic A., et al. Allele frequency net database (AFND) 2020 update: gold-standard data classification, open access genotype data and new query tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D783–D788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiskopf D., Angelo M.A., de Azeredo E.L., Sidney J., Greenbaum J.A., Fernando A.N., Broadwater A., Kolla R.V., De Silva A.D., de Silva A.M., et al. Comprehensive analysis of dengue virus-specific responses supports an HLA-linked protective role for CD8+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E2046–E2053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305227110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferdosi S.R., Ewaisha R., Moghadam F., Krishna S., Park J.G., Ebrahimkhani M.R., Kiani S., Anderson K.S. Multifunctional CRISPR-Cas9 with engineered immunosilenced human T cell epitopes. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1842. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09693-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghavan R., Friedrich M.J., King I., Chau-Duy-Tam Vo S., Strebinger D., Lash B., Kilian M., Platten M., Macrae R.K., Song Y., et al. Rational engineering of minimally immunogenic nucleases for gene therapy. Nat. Commun. 2025;16:105. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-55522-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maldonado R.A., LaMothe R.A., Ferrari J.D., Zhang A.H., Rossi R.J., Kolte P.N., Griset A.P., O'Neil C., Altreuter D.H., Browning E., et al. Polymeric synthetic nanoparticles for the induction of antigen-specific immunological tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E156–E165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408686111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simhadri V.L., Hopkins L., McGill J.R., Duke B.R., Mukherjee S., Zhang K., Sauna Z.E. Cas9-derived peptides presented by MHC Class II that elicit proliferation of CD4(+) T-cells. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:5090. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25414-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bing S.J., Justesen S., Wu W.W., Sajib A.M., Warrington S., Baer A., Thorgrimsen S., Shen R.F., Mazor R. Differential T cell immune responses to deamidated adeno-associated virus vector. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022;24:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salek M., Förster J.D., Becker J.P., Meyer M., Charoentong P., Lyu Y., Lindner K., Lotsch C., Volkmar M., Momburg F., et al. optiPRM: A Targeted Immunopeptidomics LC-MS Workflow With Ultra-High Sensitivity for the Detection of Mutation-Derived Tumor Neoepitopes From Limited Input Material. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2024;23 doi: 10.1016/j.mcpro.2024.100825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.High-dose AAV gene therapy deaths. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:910. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplemental information.