Abstract

Previous studies have revealed that skin T cells accumulate and maintain immune responses in the elderly. However, we questioned why these functional T cells fail to recognize and eliminate malignant cells, making elderly skin more prone to developing malignant tumors. To address this question, we examined the overall skin microenvironment in aging using the Nanostring nCounter system and 10x Xenium digital spatial RNA sequencing. The digital RNA counts of CIITA and HLA-DMA, which are involved in antigen presentation, were negatively correlated with age, whereas the counts of UBE2L3 and SOCS1, molecules that play roles in immune regulation, were positively correlated with aging. The upregulation of SOCS1 was detected in the microenvironment of the skin malignant tumors. Spatial transcriptome analysis revealed that cells with high levels of SOCS1 were distributed in upper dermis and periadnexal area, and some SOCS1-positive fibroblasts were closely lined with CD163-positive macrophages. Our study showed that the skin microenvironment in the elderly may shift to an immunoregulatory condition. Furthermore, modulating certain molecules that may be involved in shared immunoregulatory mechanisms between healthy elderly skin and malignant tumors could serve as a potential strategy for preventing malignancies in elderly skin.

Keywords: Aging, Microenvironment, SOCS1

Introduction

Previous studies revealed that aging is associated with progressive decline of immune function, called immunosenescence (Lee et al, 2022; Liu et al, 2023). In the innate immune system, phagocytic capacities of neutrophils and macrophages decrease (Butcher et al, 2001, 2000; Moss et al, 2024). Uptake and presentation of antigens by dendric cells and their homing to lymph nodes are impaired (Agrawal and Gupta, 2011; Wong and Goldstein, 2013). Elevated NK cell numbers and reduced cytotoxic function were reported (Brauning et al, 2022; Weiskopf et al, 2009). In the adaptive immune system, the number of naïve T cells and diversity of the T-cell repertoire decrease in the elderly (Naylor et al, 2005). The frequency of regulatory T cells is increased in the blood of elderly individuals (Lages et al, 2008). On the other hand, elevated plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF have been described in elderly populations and contribute to a lifelong continuous stimulation of the immune system, resulting in a subclinical inflammatory status defined as inflammaging (Koelman et al, 2019; Li et al, 2023; Weiskopf et al, 2009).

Recent studies unveiled that immune cells in tissue, including resident immune cells, form distinct local immunity different from that in blood (Farber, 2021). A few decades ago, it was considered that aged skin immune system was deteriorated in its adaptive capability (Sunderkötter et al, 1997). However, a previous study demonstrated that T cells in human elderly skin maintain their number, effector cytokine production, repertoire diversity, and antigen responses, whereas T cells in human blood lose the repertoire diversity and effective antigen responses (Koguchi-Yoshioka et al, 2021). Furthermore, CD8 resident memory T cells, which promote tumor immunity and whose infiltration in tumors is related to favorable prognosis (Edwards et al, 2018), are increased in the elderly skin (Koguchi-Yoshioka et al, 2021). However, although T cells in the elderly skin maintain their functionality, the incidence of skin malignant tumors such as basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) increases in line with age (Birch-Johansen et al, 2010; Dodds et al, 2014; Holmes et al, 2007; Ogata et al, 2023). These observations raised the question of why these functional T cells in the elderly skin overlook the mutant cells that allow the development of skin cancers. Recent reports have demonstrated that the phenotype of aged macrophages is accelerated by fibroblasts (Gather et al, 2022) and that even aged hair follicle stem cells can regenerate the hair follicles in the existence of young dermis (Ge et al, 2020). From these studies, we hypothesized that skin immune microenvironmental alteration in the elderly skin may induce inappropriate immune responses and allow the development of malignant tumors. We aimed to investigate the aging of the skin immune microenvironment using digital mRNA expression counts and spatial RNA-sequencing techniques.

Results

Immunoregulatory features in the elderly skin

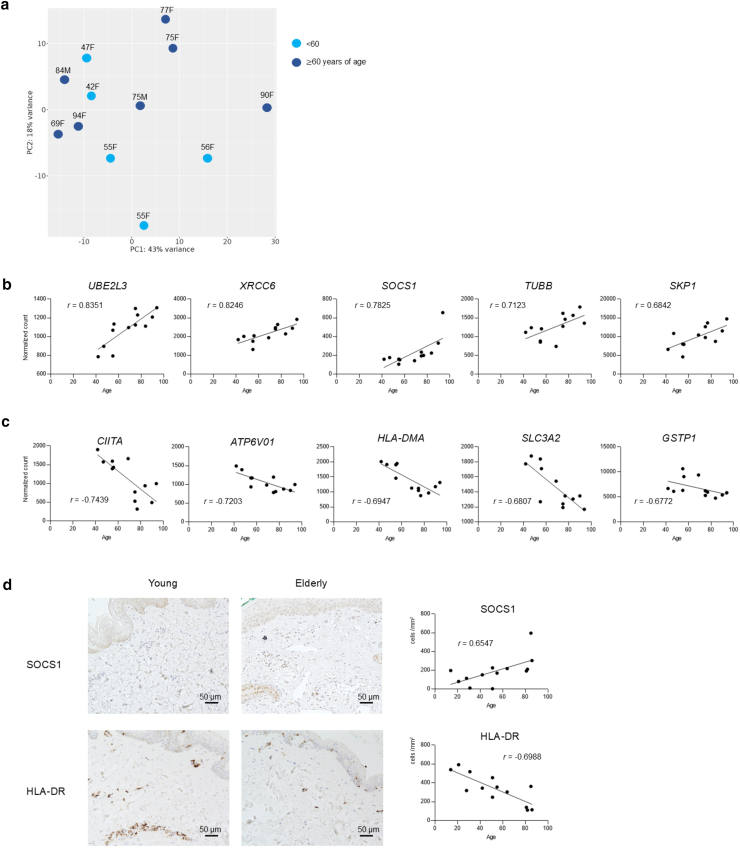

Normalized digital mRNA count data of 770 genes (Supplementary Data S1) from the nCounter Human AutoImmune Profiling Panel were subjected to principal component analysis to reveal that the overall gene profiles of the young and the elderly skin were evenly distributed (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Immunoregulatory features in elderly skin. (a) Primary component analysis of gene expression profiles. Light blue indicates individuals aged <60 years, and dark blue represents those aged ≥60 years. n = 12. (b) Top 5 genes showing the strongest positive correlation with aging, on the basis of Spearman correlation coefficients (r-values). n = 12. (c) Top 5 genes showing the strongest negative correlation with aging, on the basis of Spearman correlation coefficients (r-values). n = 12. (d) Immunohistochemistry of the indicated proteins in representative samples from young and elderly individuals. n = 13.

Among the 770 genes mentioned earlier, 17.4% of the genes (134 of 770) had an absolute Spearman correlation coefficient >0.4 (Supplementary Data S2). The top 5 genes that showed a positive Spearman correlation with age are depicted in Figure 1b. The count of UBE2L3, which regulates signaling pathways such as NF-κB and GSK3β/p65 (Zhang et al, 2022) and whose overexpression leads to evasion of apoptosis (Tao et al, 2020), and the count of XRCC6, exerting tumor-promoting effects through β-catenin/Wnt signaling pathway (Zhu et al, 2016), were positively correlated with aging (Figure 1b). The count of SOCS1 negatively regulates effector cytokine signaling and effective antitumor response (Bidgood et al, 2024; Ilangumaran and Rottapel, 2003; Liau et al, 2018); SKP1, S-phase kinase-associated protein, whose overexpression promotes cancer stemness, initiation, and progression (Hussain et al, 2022), and TUBB, encoding a beta-tubulin protein and greatly upregulated across various cancers (Zhu et al, 2024), were also positively correlated with aging (Figure 1b). On the other hand, the top 5 genes that showed a negative Spearman correlation with age are depicted in Figure 1c. The count of major histocompatibility complex class II–related genes, such as CIITA, major histocompatibility complex class II transactivator, and HLA-DMA, was negatively correlated with aging (Figure 1c). One of the HLA class II genes, HLA-DRB3/4, was also negatively correlated with aging, although its r-value was not ranked among the top 5 highest negative correlations (r = −0.5965). The ATPV601 gene, involved in lysosome acidification; GSTP1, protecting cells from oxidants and electrophilic-mediated genomic damage; and SLC3A2, whose downregulation mediates immune evasion (Wu et al, 2024), were also negatively correlated with aging (Figure 1c). Possibly owing to the small sample size (n = 12), none of the 770 genes we analyzed reached statistical significance after multiple testing correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate method (Supplementary Data S3). However, when we divided the samples into 2 age groups, the top 5 genes ranked by absolute Spearman correlation coefficient showed significantly increased or decreased expression in the older group (Supplementary Figure S1).

By immunohistochemistry, the density of SOCS1-positive cells was positively correlated with aging (r = 0.6547) (Figure 1d), whereas that of HLA-DR was negatively correlated with aging (r = −0.6988) (Figure 1d).

Collectively, our normalized digital mRNA count data suggest that elderly skin microenvironment may have immunoregulatory features and lesser ability of antigen presentation.

SOCS1 expression was upregulated in the microenvironment of both cSCC and BCC

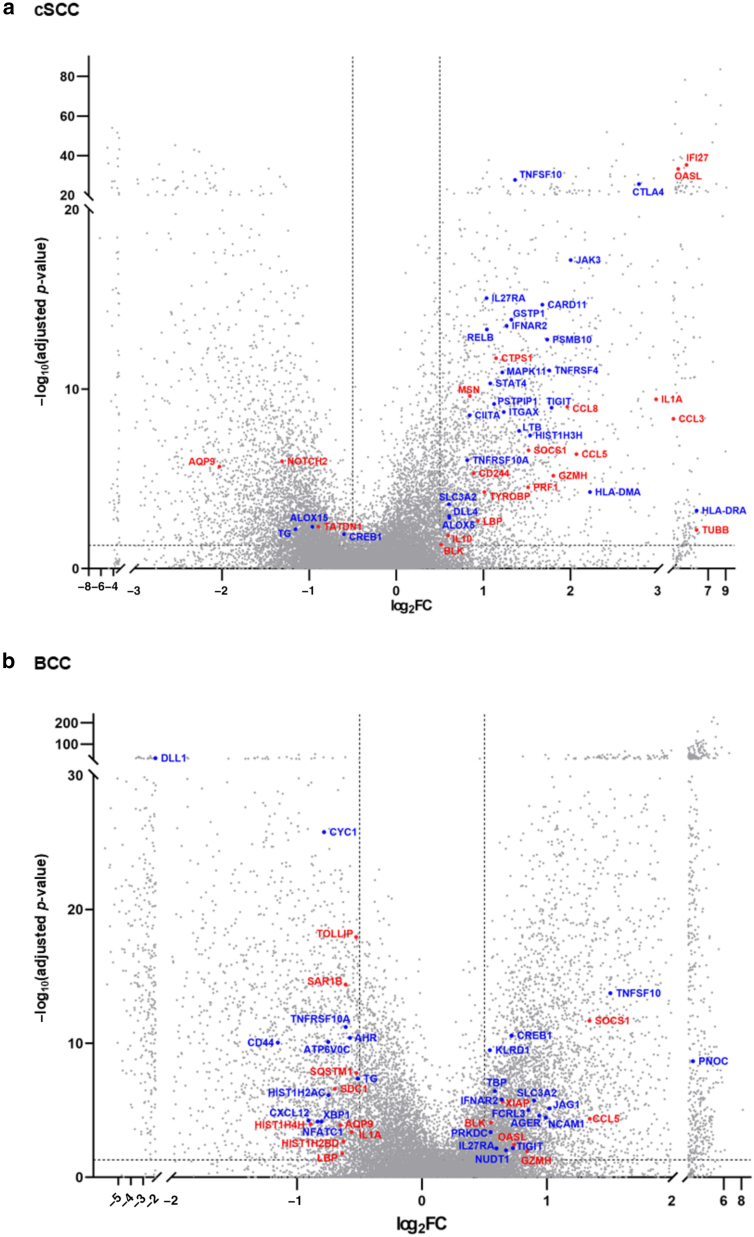

We next investigated whether the genes that showed a positive or negative correlation with aging in our previous Nanostring analysis were also upregulated or downregulated in the microenvironment of cSCC and BCC, whose incidence increases remarkably with age (Green and Olsen, 2017; Verkouteren et al, 2017), using publicly available bulk RNA-sequencing data. Among the differentially expressed genes with adjusted P < .05 and log2 fold change > 0.5 in cSCC (GSE139505) (Das Mahapatra et al, 2020) or BCC (GSE125285) (Wan et al, 2021) compared with healthy controls, the genes positively or negatively correlated with aging in our digital count analysis were highlighted in red (r > 0.4) or blue (r < −0.4), respectively (Figure 2a and b). We performed a hypergeometric test to examine whether the genes with an absolute correlation coefficient |r| > 0.4 in our digital count analysis significantly overlapped with the genes from bulk RNA sequencing of cSCC and BCC that met the criteria of adjusted P < .05 and log2 fold change > 0.5. Using the 758 genes shared between the bulk RNA-sequencing and our NanoString platforms, the results showed P = .99 for cSCC and P = .77 for BCC, indicating no statistically significant overlap between age-correlated genes in our digital count analysis and the significantly altered genes in cSCC or BCC. However, among these highlighted genes (Figure 2a and b), the expression of SOCS1, which was positively correlated with aging in our Nanostring data (r = 0.6547), was upregulated in both cSCC and BCC (cSCC: log2 fold change = 1.51, P = 1.36E-08; BCC: log2 fold change = 1.34, P = 1.25E-13).

Figure 2.

SOCS1 expression was upregulated in the microenvironment of both cSCC and BCC. (a) DEGs in cSCC compared with those in healthy controls, based on GSE139505. (b) DEGs in BCC compared with those in healthy controls, based on GSE125285. The x-axis represents log2FC, and the y-axis represents −log10 of the adjusted P-value. Among the DEGs with adjusted P < .05 and log2FC > 0.5, genes that are positively or negatively correlated with aging (red: r > 0.4, blue: r < −0.4) in the digital count analysis shown in Figure 1 are highlighted. BCC, basal cell carcinoma; DEG, differentially expressed gene; FC, fold change; cSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.

The 10x Xenium enables visualization of SOCS1-producing cells, their localization, and interacting cells

Because SOCS1 plays a critical role in limiting effector cytokine signaling and effective antitumor response (Bidgood et al, 2024) and because its expression was positively correlated with age and upregulated in skin malignancies, we focused on the sources of SOCS1 as a potential molecule that may protect aged skin from malignant tumors. The spatial transcriptome analysis using 10x Xenium using upper-arm skin specimens from 3 donors with different ages depicted that SOCS1-positive cells were distributed in the upper dermis and periadnexal area in all ages (Figure 3a). The differentially expressed gene analysis revealed that the sources of SOCS1 were fibroblasts, T cells, macrophages, sebocytes, and sweat gland cells, suggesting that SOCS1-positive cells are not restricted to a single cell type (Supplementary Data S4 and S5). We compared the normalized counts of cells classified as fibroblasts and CD8 T cells, which were identified as the source of SOCS1 in all samples (Supplementary Data S5), and found no significant age-related differences in expression among the 3 samples (Supplementary Figure S2) (fibroblasts: P = .2217; CD8 T cells: P = .1620). However, on the basis of the clustering data, we found that the populations with the highest total counts, clusters 1 and 2, in all samples were identified as fibroblasts (Supplementary Data S5). Thus, we next assessed the distribution of SOCS1-expressing fibroblasts, which were one of the most abundantly observed SOCS1-expressing cell types. These SOCS1-expressing fibroblasts either exist solely (Figure 3b), connect with other fibroblasts (Figure 3c), or interact with immune cells in the stroma in the skin. Some of these fibroblasts were adjacent to CD163-positive macrophages (Figure 3d), whereas CD163-positive macrophages were also found next to other cell types, such as endothelial cells (Figure 3e).

Figure 3.

The 10x Xenium enables visualization of SOCS1-producing cells, their localization, and interacting cells. (a) Top: H&E-stained control slides. Bottom: Visualization of SOCS1-expressing cells. Only transcripts of SOCS1 are shown. Transcript size was set to 17 and point opacity was set to 25 using the Xenium explorer. A small orange square/arrow indicates the area shown in Figure 3b, a yellow square/arrow in Figure 3c, a white square/arrow in Figure 3d, and a red square/arrow in Figure 3e. (b–d) SOCS1-producing fibroblasts are located either (b) solely, (c) adjacent to other fibroblasts, or (d) to CD163-positive macrophages. (e) CD163-positive macrophages are positioned adjacent to vascular endothelial cells. (b–e) Transcripts of SOCS1 and CD163 are shown. The transcript size was set to 10, and point opacity was set to 25 using Xenium Explorer. Cell types were identified on the basis of inspection in Xenium Explorer. “F” indicates fibroblasts, “M163” indicates CD163-positive macrophages, “M” indicates macrophages, “V” indicates vascular endothelial cells, and “Myo” indicates myofibroblasts. Red lines indicate the nuclei.

Discussion

We aimed to investigate the immune microenvironment of aging skin and found that major histocompatibility complex class II–related genes were negatively correlated with age, whereas immunoregulatory genes were positively correlated. This may suggest that elderly skin microenvironment loses effective immune responses and the ability of antigen presentation, implying that elderly skin microenvironment can be the environment where the tumor cells can be overlooked by immune cells.

By applying spatial transcriptome analysis, we could investigate in detail not only the transcripts retained by each cell type but also the proximity and potential interactions among various cell types. Our spatial transcriptome analysis revealed that SOCS1, which was positively correlated with aging in our analyses, is expressed not only by immune cells but also by stromal cells such as fibroblasts. This highlights the importance of considering the microenvironment, including stromal cells, when analyzing immune cells residing in tissues. Possible explanations for the positive correlation between SOCS1 expression and aged skin include previously reported factors, including chronic infections such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Carow et al, 2011), hepatitis C virus (Zhang et al, 2011), and cytomegalovirus (Shin et al, 2015) as well as oxidative stress (Kim et al, 2020) and accumulated epigenetic alterations (Cheng et al, 2014). Although the present Nanostring analysis was conducted using trunk skin samples, it is also plausible that cumulative exposure to UVR may contribute to this association (Friedrich et al, 2003). SOCS1-expressing fibroblasts, which constitute a major cell type expressing SOCS1, were found either as isolated cells within the stroma or adjacent to stromal cells or immune cells, such as CD163-positive macrophages, a marker of tumor-associated macrophages (Mathiesen et al, 2025) and immunomodulatory M2 macrophages (Chen et al, 2023).

The effects of SOCS1 vary depending on the cell type. Even within the same cell context, there are contrasting reports, ranging from studies demonstrating impaired antitumor immunity due to reduced cytokine production to those showing immunostimulatory and antitumor effects. In T cells, high expression of SOCS1 in T cells from patients correlates with low acute graft-versus-host disease occurrence after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, suggesting that SOCS1 suppresses T-cell activation (Guo et al, 2022). Moreover, in a mouse model, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated inactivation of SOCS1 in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes enhanced responsiveness to cytokine signaling and increased antitumor activity in vivo (Schlabach et al, 2023). In macrophages, TNF production was increased in SOCS1-knockout mice (Kinjyo et al, 2002), and silencing SOCS1 promoted polarization toward a proinflammatory M1 phenotype (Liang et al, 2017). Overall, SOCS1 plays an immunoregulatory role in immune cells. In fibroblasts, SOCS1 inhibited cell growth and induced cellular senescence (Calabrese et al, 2009). Another study showed that overexpression of SOCS1 suppressed collagen production (Shoda et al, 2007). In a chondrocytic cell line, overexpression of SOCS1 suppressed signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 pathway while enhancing the MAPK pathway (Ben-Zvi et al, 2006). In the tumor biology, repressed SOCS1 gene by epigenetic alteration such as promoter CpG methylation or microRNA has been reported in various cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma (Yoshikawa et al, 2001), multiple myeloma (Galm et al, 2003), prostate cancer (Kobayashi et al, 2012), and breast cancer (Jiang et al, 2010), among others, indicating the antitumor effects of SOCS1. Conversely, in melanoma cells, repression of SOCS1 has been shown to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis (Yu and Long, 2017), highlighting the dichotomous roles of SOCS1 in tumor, which may be context dependent on the basis of the organ and its microenvironment. Further studies are needed to elucidate the cell type–, organ-, and microenvironment-specific functions of SOCS1. Our study revealed that SOCS1 was positively correlated with aging and upregulated in common skin malignancies such as cSCC and BCC. Given that SOCS1 expression is elevated in aged skin and considering reports that SOCS1 inactivation enhances tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy (Schlabach et al, 2023) and that SOCS1-silenced dendritic cells improve the efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (Zheng et al, 2021) in mouse models, a comprehensive evaluation of cell-specific SOCS1 function in both the normal skin and tumor microenvironments may lead to a new strategy targeting SOCS1-expressing stromal cells to prevent tumor development in elderly skin.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small number of digital mRNA counts and spatial transcriptome analyses performed. In addition, the number of panel genes, particularly in the spatial transcriptome, was limited. Although the primary aim of this study was to investigate the skin microenvironment in aged individuals, further studies are warranted to validate our findings through in vitro experiments using human fibroblasts, which examine the role of SOCS1 and its interactions with immune cells, such as macrophages, as well as with skin cancer cells. Further accumulation of human sample data would overcome these limitations.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the microenvironment of elderly skin shifts toward an immunoregulatory states. The SOCS1, which is positively correlated with aging skin and upregulated in skin malignant tumors, is expressed by both immune cells and stromal cells, some of which are found in contact with regulatory immune cells. Modulating the functions and interactions of these molecules, which may be involved in a common immunoregulatory mechanism in both healthy elderly skin and malignant tumors, could potentially help to protect elderly skin from tumor development.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects

All study protocols were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka University Hospital (number 20158). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The list of samples obtained is provided in Supplementary Table S1. The specimens used for digital mRNA counting and immunohistochemical staining were obtained from individuals who visited our hospital between 2019 and 2023, whereas the specimens for the 10x Xenium analysis were obtained from individuals who visited between 2023 and 2024. The 10x Xenium (HC1–3) and Nanostring (sample number 1–12) data were obtained from 4-mm punch biopsies of healthy individuals with no evidence of skin or systemic disease. The immunohistochemical samples (sample numbers 13–25) were obtained from individuals without systemic disease and include surplus skin grafts collected during treatment for benign skin tumors that required grafting. These grafts were obtained from sites at least 30 cm away from the skin benign tumor and were confirmed by at least 1 board-certified dermatologist to be free of any skin lesions.

Preparation of mRNA and digital mRNA count

Total RNA was isolated from frozen 12 healthy human skin samples from the trunk (ages: 42–94 years) using E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (Omega Biotek), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were quantified, and the OD260/230 and the OD260/280 ratios were confirmed to be >1.6 and 1.8, respectively. Gene expression was quantified by NanoString nCounter system (NanoString Technologies) with nCounter Human AutoImmune Profiling Panel. Data analysis was conducted using nSolver 4.0. Normalized RNA counts data are provided in Supplementary Data S1. Heatmap was generated using iDEP1.1 (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/idep11/) and provided in Supplementary Data S2.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining for HLA-DR and SOCS1 was performed on serial paraffin-embedded sections of 13 normal skin samples (ages 14–86 years). The list of samples is provided in Supplementary Table S1. After standard deparaffinization, antigen retrieval was carried out as follows: for anti-SOCS1, heating in a 120 °C oil bath for 11 minutes with citrate buffer (pH 6.0), followed by incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature; for anti-HLA-DR, heating in an oil bath for 16 minutes with EDTA buffer (pH 9.0), followed by incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature. The sections were subsequently washed with Tween-PBS. To prevent nonspecific signals, sections were blocked with Blocking One Histo (Nacalai Tesque) for 30 minutes. Primary antibodies were then applied at room temperature for 30 minutes: a monoclonal rabbit antibody against HLA-DR (number ab92511; Abcam, dilution 1:10000) and a polyclonal rabbit antibody against SOCS1 (number ab137384; Abcam, dilution 1:100). Secondary staining was performed using the Dako REAL Detection System (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Reactions were visualized using the ABC developing system (Vector Laboratories), and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Vector Laboratories). All immunohistochemically stained sections were imaged using a Keyence BZ-X710 microscope (Keyence). The quantification using high-power fields was performed by a single individual who was blinded to the age of the participants. Five random high-power fields (×400 magnification) were selected, and the number of positive cells was counted in each field to calculate the average.

Identification of differentially expressed genes in cSCC and BCC

We analyzed differentially expressed genes in cSCC and BCC using publicly available RNA-sequencing datasets from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (GSE139505 and GSE125285). The GSE139505 dataset includes 7 control samples and 9 cSCC cases (Das Mahapatra et al, 2020) (Supplementary Table S1), whereas the GSE125285 dataset comprises 25 control samples and 25 BCC cases (Wan et al, 2021) (Supplementary Table S1). Differential expression analysis was performed using the RaNAseq pipeline (https://ranaseq.eu/home). Raw FASTQ files were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38). Gene-level counts were obtained with featureCounts, and differential expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2, in which multiple testing correction of P-values in differential expression analysis is performed by default using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (Love et al, 2014). Genes with a P < .05 were considered differentially expressed. Volcano plots were generated using GraphPad Prism, version 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software).

The 10x Xenium in situ

In situ gene expression profiling was performed using the Xenium platform (10x Genomics), following the protocols provided by the manufacturer. Tissue sections, 5 μm in thickness, were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks according to the “Xenium In Situ for FFPE-Tissue Preparation Guide” (CG000578 Rev C, 10x Genomics). These sections were carefully mounted onto the sample area of a Xenium slide (PN-1000465), followed by deparaffinization and permeabilization as detailed in the Xenium Fixation and Permeabilization Protocol (CG000580 Rev C, 10x Genomics). The probe hybridization mix was prepared using the 10x Genomics Xenium Human Skin Gene Expression Panel (260 genes) with an additional customized panel (Xenium Custom Gene Expression Panel, design identification: P3HCWE) (Supplementary Data S6). The custom panel was designed using the Xenium Panel Designer following the Xenium Add-on Panel Design Technical Note (CG000643 Rev B, 10x Genomics). During the Xenium Analyzer workflow, the Xenium In Situ Cell Segmentation reagents (PN-100661) were used to automate cell boundary identification with a multitissue stain mix. This mix included antibodies for membrane labeling, antibodies for intracellular labeling, a universal ribosomal RNA label, and DAPI for nuclear staining. Probe hybridization, ligation, amplification, cell segmentation staining, and autofluorescence quenching were carried out according to the Xenium In Situ Gene Expression with Cell Segmentation Staining User Guide (CG000749 Rev A, 10x Genomics). The slides were then processed with the Xenium Analyzer for imaging and analysis, following the Decoding and Imaging User Guide (CG000584 Rev E, 10x Genomics). The instrument software (version 3.0.2.0) and analysis software (version 3.0.0.15) were used. Output images and gene expression profiles were evaluated using Xenium Explorer, version 3.1.0. After the Xenium analysis, H&E staining was applied to the Xenium slide. For quality control, the output summary HTML file generated by the Xenium Analyzer was reviewed, and no errors were reported.

Cell clustering was performed using the default pipeline implemented in the 10x Genomics Xenium platform. Briefly, raw transcript counts were aggregated for each segmented cell to generate a cell-by-gene expression matrix. The expression values were normalized and log transformed to minimize the influence of highly expressed genes and to stabilize variance across cells. Dimensionality reduction was then conducted using principal component analysis, followed by graph-based clustering. A k-nearest neighbor graph was constructed in the reduced principal component analysis space on the basis of transcriptomic similarity between cells. Clusters were identified using the Louvain community detection algorithm, which partitions the graph into groups of cells with high internal connectivity. For visualization, clustered cells were projected onto a 2-dimensional Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection embedding, and cluster identities were also mapped back onto the tissue section using spatial coordinates derived from cell segmentation. Each cluster was automatically assigned a unique color in the Xenium Explorer interface. Clusters were annotated manually on the basis of the following marker gene expression and histological location of the skin: LUM, COL5A2, COL6A2, and COL6A3 for fibroblast; keratin 5 gene K5 and TP63 for stratum basale; CLDN1 and keratin gene 2 gene K2 for stratum granulosum; KRTDAP for stratum spinosum; ACTA2, CALD1, and TAGLN for myofibroblasts; MLANA and PMEL for melanocytes; CD1A for Langerhans cell; VWF and CDH5 for vascular endothelial cell; PROX1 for LYVE1 for lymphatic endothelial cell; TAGLN and NR2F2 for vascular smooth muscle cell; CD3D, CD3E, CD3G, and CD4 for CD4 T cell; CD3D, CD3E, CD3G, and CD8A for CD8 T cell; FOXP3, CD3D, CD3E, and CD3G for regulatory T cell; CD68 for macrophage; CD68 and CD163 for CD163-positive macrophage; RHEB and FABP5 for sebocytes; keratin 5 gene K5 and INSIG1 for sebaceous gland-peripheral layer; keratin 15 gene K15, CXADR, and CRABP2 for sweat duct cell; keratin 15 gene K15 and MARCKSL1 for sweat gland secretory cell; FABP4 and ENPP1 for adipocyte; S100B, CDH19, and EDNRB for neural cell.

Spatial transcriptomic data were processed and visualized using 10x Genomics Xenium Explorer (version 3.1.0). Individual transcript molecules were detected through multiplexed in situ hybridization and decoded through sequential imaging and barcode readout. Each transcript was assigned to a specific gene target and mapped to its corresponding (x, y) spatial coordinates within the tissue section. For visualization, detected transcripts were rendered as individual spots (dots) overlaid on the tissue image and/or segmented cell boundaries. Transcripts were displayed at single-molecule resolution. Gene-specific expression could be viewed by selecting target genes within the Explorer interface, and transcript spots corresponding to the selected genes were shown in designated colors. Normalization of the data shown in Supplementary Figure S2 was performed using Seurat’s NormalizeData function with the parameter normalization.method set to 'LogNormalize.' Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was performed using GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software).

Statistics

Statistical analyses for Figure 1b–d were performed using Prism 10 (GraphPad Software). The Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated using the same software. For Figure 1b and c, the adjusted P-values were calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method for multiple testing correction, and the results are provided in Supplementary Data S3. In addition, the same dataset shown in Figure 1a–c was reanalyzed by dividing the samples into 2 groups using age 60 years as a cutoff, and the results are presented in Supplementary Figure S1. This analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney test in Prism 10 (GraphPad Software). The analysis methods for the public bulk RNA-sequencing data shown in Figure 2 and the 10x Xenium spatial transcriptomics data shown in Figure 3 are described in detail earlier.

Ethics Statement

All study protocols were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Osaka University Hospital (number 20158). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The spatial transcriptome data were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan database with the accession numbers JGAS000771 for the study and JGAD000913 for dataset (https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/index-e.html). Other data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ORCIDs

Yuri Shimizu: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8761-8847

Hanako Koguchi-Yoshioka: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3415-5727

Toshiki Kubo: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5696-4111

Shoichi Matsuda: http://orcid.org/0009-0000-5140-4783

Yutaka Matsumura: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2429-8732

Atsushi Tanemura: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5239-8474

Michiko Nomori: http://orcid.org/0009-0004-0255-3626

Naoya Otani: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3532-2267

Mifue Taminato: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9368-5878

Koichi Tomita: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1673-3367

Tateki Kubo: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1402-5383

Rei Watanabe: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8254-9176

Manabu Fujimoto: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3062-4872

Conflict of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the patients and their families for their invaluable cooperation. We also thank all members of the Department of Dermatology at Osaka University and Professor Katsumasa Fujita from the Department of Applied Physics at Osaka University for their involvement in this work. We appreciate KOTAI Biotechnologies for their assistance with the spatial transcriptome data analysis. This research is supported by Japanese Society for Investigative Dermatology's Fellowship Shiseido Research Grant to HK-Y, Research Acceleration Program by KOTAI Biotechnologies to HK-Y, Nakatomi Foundation to HK-Y, the Lydia O'Reilly Memorial Foundation for the Promotion of Dermatology to HK-Y, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (23K15267 to HK-Y and 24K02472 to RW), Takeda Science Foundation to RW, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (23gm6710019h9901) to RW, and COI-NEXT (a program on open innovation platform for industry-academia co-creation) (JPMJPF2009) to MF and RW.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: HK-Y, MF, RW; Data Curation: YS, HK-Y, YM, AT, MN, NO, MT, KT, TK, MF, RW; Formal Analysis: YS, HK-Y, RW; Funding Acquisition: HK-Y, RW, TK; Investigation: YS, HK-Y; Methodology: HK-Y, TK, MF, RW; Project Administration: HK-Y, MF, RW; Resources: YS, HK-Y, TK, SM, YM, AT, MN, NO, MT, KT, TK, RW, MF; Supervision: HK-Y, TK, MF, RW; Validation: YS, HK-Y, TK, SM, YM, AT, MN, NO, MT, KT, TK, RW, MF; Visualization: YS, HK-Y; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: YS, HK-Y, RW; Writing – Review and Editing: YS, HK-Y, TK, SM, YM, AT, MN, NO, MT, KT, TK, RW, MF

Declaration of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) or Large Language Models (LLMs)

The author(s) did not use AI/LLM in any part of the research process and/or manuscript preparation.

accepted manuscript published online XXX; corrected proof published online XXX

Footnotes

Cite this article as: JID Innovations 2025.100401

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.jidonline.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjidi.2025.100401.

Supplementary Materials

Normalized RNA counts. Normalized RNA counts data were quantified using NanoString nCounter system (NanoString Technologies) with nCounter Human AutoImmune Profiling Panel. n = 12.

Heatmaps of normalized counts. Heatmaps are divided into 4 groups on the basis of Spearman correlation analysis using an r-value cutoff of 0.4. A total of 770 genes from the nCounter Human AutoImmune Profiling Panel were analyzed. Samples are arranged from left to right in order of increasing age. n = 12.

Adjusted P-values for 770 genes from the nCounter Human AutoImmune Profiling Panel. Adjusted P-values were calculated for all 770 genes using the Benjamini–Hochberg method for FDR correction. n = 12. FDR, false discovery rate.

Mean counts, log2FC, and adjusted P-values for each cluster in each sample analyzed with 10x Xenium. This dataset includes gene expression data for each cell cluster from our spatial transcriptomic analysis, including mean counts, log2FC, and adjusted P-values. Cluster names were manually annotated on the basis of marker genes described in the Materials and Methods. FC, fold change.

Total counts of each cluster in each sample analyzed with 10x Xenium. If SOCS1 expression is higher in that cluster than in the other clusters within the same sample (log2FC > 1) (Supplementary Data S4), it is highlighted in yellow. FC, fold change.

Panels used in our 10x Xenium analyses. The 260 genes were part of the predesigned Xenium Human Skin Gene Expression Panel, and an additional 50 genes were included in a custom panel (design ID: P3HCWE). ID, identification.

References

- Agrawal A., Gupta S. Impact of aging on dendritic cell functions in humans. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zvi T., Yayon A., Gertler A., Monsonego-Ornan E. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) 1 and SOCS3 interact with and modulate fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:380–387. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidgood G.M., Keating N., Doggett K., Nicholson S.E. SOCS1 is a critical checkpoint in immune homeostasis, inflammation and tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1419951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch-Johansen F., Jensen A., Mortensen L., Olesen A.B., Kjær S.K. Trends in the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer in Denmark 1978-2007: rapid incidence increase among young Danish women. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2190–2198. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauning A., Rae M., Zhu G., Fulton E., Admasu T.D., Stolzing A., et al. Aging of the immune system: focus on natural killer cells phenotype and functions. Cells. 2022;11:1017. doi: 10.3390/cells11061017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher S., Chahel H., Lord J.M. Review article: ageing and the neutrophil: no appetite for killing? Immunology. 2000;100:411–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher S.K., Chahal H., Nayak L., Sinclair A., Henriquez N.V., Sapey E., et al. Senescence in innate immune responses: reduced neutrophil phagocytic capacity and CD16 expression in elderly humans. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:881–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese V., Mallette F.A., Deschênes-Simard X., Ramanathan S., Gagnon J., Moores A., et al. SOCS1 links cytokine signaling to p53 and senescence. Mol Cell. 2009;36:754–767. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carow B., Ye Xq, Gavier-Widén D., Bhuju S., Oehlmann W., Singh M., et al. Silencing suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS1) in macrophages improves Mycobacterium tuberculosis control in an interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma)-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:26873–26887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.238287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Saeed A.F.U.H., Liu Q., Jiang Q., Xu H., Xiao G.G., et al. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:207. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Huang C., Ma T.T., Bian E.B., He Y., Zhang L., et al. SOCS1 hypermethylation mediated by DNMT1 is associated with lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Toxicol Lett. 2014;225:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Mahapatra K., Pasquali L., Søndergaard J.N., Lapins J., Nemeth I.B., Baltás E., et al. A comprehensive analysis of coding and non-coding transcriptomic changes in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3637. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59660-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds A., Chia A., Shumack S. Actinic keratosis: rationale and management. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2014;4:11–31. doi: 10.1007/s13555-014-0049-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J., Wilmott J.S., Madore J., Gide T.N., Quek C., Tasker A., et al. CD103+ tumor-resident CD8+ T cells are associated with improved survival in immunotherapy-naïve melanoma patients and expand significantly during anti-PD-1 treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:3036–3045. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber D.L. Tissues, not blood, are where immune cells function. Nature. 2021;593:506–509. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01396-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich M., Holzmann R., Sterry W., Wolk K., Truppel A., Piazena H., et al. Ultraviolet B radiation-mediated inhibition of interferon-gamma-induced keratinocyte activation is independent of interleukin-10 and other soluble mediators but associated with enhanced intracellular suppressors of cytokine-signaling expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:845–852. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galm O., Yoshikawa H., Esteller M., Osieka R., Herman J.G. SOCS-1, a negative regulator of cytokine signaling, is frequently silenced by methylation in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;101:2784–2788. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gather L., Nath N., Falckenhayn C., Oterino-Sogo S., Bosch T., Wenck H., et al. Macrophages are polarized toward an inflammatory phenotype by their aged microenvironment in the human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:3136–3145.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2022.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y., Miao Y., Gur-Cohen S., Gomez N., Yang H., Nikolova M., et al. The aging skin microenvironment dictates stem cell behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:5339–5350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901720117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green A.C., Olsen C.M. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: an epidemiological review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:373–381. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Li R., Wang M., Hou Y., Liu S., Peng T., et al. Multiomics analysis identifies SOCS1 as restraining T cell activation and preventing graft-versus-host disease. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022;9 doi: 10.1002/advs.202200978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C., Foley P., Freeman M., Chong A.H. Solar keratosis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, presentation and treatment. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M., Lu Y., Tariq M., Jiang H., Shu Y., Luo S., et al. A small-molecule Skp1 inhibitor elicits cell death by p53-dependent mechanism. iScience. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilangumaran S., Rottapel R. Regulation of cytokine receptor signaling by SOCS1. Immunol Rev. 2003;192:196–211. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Zhang H.W., Lu M.H., He X.H., Li Y., Gu H., et al. MicroRNA-155 functions as an OncomiR in breast cancer by targeting the suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 gene. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3119–3127. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G.Y., Jeong H., Yoon H.Y., Yoo H.M., Lee J.Y., Park S.H., et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of suppressors of cytokine signaling target ROS via NRF-2/thioredoxin induction and inflammasome activation in macrophages. BMB Rep. 2020;53:640–645. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2020.53.12.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinjyo I., Hanada T., Inagaki-Ohara K., Mori H., Aki D., Ohishi M., et al. SOCS1/JAB is a negative regulator of LPS-induced macrophage activation. Immunity. 2002;17:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N., Uemura H., Nagahama K., Okudela K., Furuya M., Ino Y., et al. Identification of miR-30d as a novel prognostic maker of prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1455–1471. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelman L., Pivovarova-Ramich O., Pfeiffer A.F.H., Grune T., Aleksandrova K. Cytokines for evaluation of chronic inflammatory status in ageing research: reliability and phenotypic characterisation. Immun Ageing. 2019;16:11. doi: 10.1186/s12979-019-0151-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koguchi-Yoshioka H., Hoffer E., Cheuk S., Matsumura Y., Vo S., Kjellman P., et al. Skin T cells maintain their diversity and functionality in the elderly. Commun Biol. 2021;4:13. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-01551-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lages C.S., Suffia I., Velilla P.A., Huang B., Warshaw G., Hildeman D.A., et al. Functional regulatory T cells accumulate in aged hosts and promote chronic infectious disease reactivation. J Immunol. 2008;181:1835–1848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.A., Flores R.R., Jang I.H., Saathoff A., Robbins P.D. Immune senescence, immunosenescence and aging. Front Aging. 2022;3 doi: 10.3389/fragi.2022.900028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Li C., Zhang W., Wang Y., Qian P., Huang H. Inflammation and aging: signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:239. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01502-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y.B., Tang H., Chen Z.B., Zeng L.J., Wu J.G., Yang W., et al. Downregulated SOCS1 expression activates the JAK1/STAT1 pathway and promotes polarization of macrophages into M1 type. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:6405–6411. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liau N.P.D., Laktyushin A., Lucet I.S., Murphy J.M., Yao S., Whitlock E., et al. The molecular basis of JAK/STAT inhibition by SOCS1. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1558. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04013-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Liang Q., Ren Y., Guo C., Ge X., Wang L., et al. Immunosenescence: molecular mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:200. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01451-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen H., Juul-Madsen K., Tramm T., Vorup-Jensen T., Møller H.J., Etzerodt A., et al. Prognostic value of CD163+ macrophages in solid tumor malignancies: a scoping review. Immunol Lett. 2025;272 doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2025.106970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss C.E., Johnston S.A., Kimble J.V., Clements M., Codd V., Hamby S., et al. Aging-related defects in macrophage function are driven by MYC and USF1 transcriptional programs. Cell Rep. 2024;43 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor K., Li G., Vallejo A.N., Lee W.W., Koetz K., Bryl E., et al. The influence of age on T cell generation and TCR diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:7446–7452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata D., Namikawa K., Nakano E., Fujimori M., Uchitomi Y., Higashi T., et al. Epidemiology of skin cancer based on Japan's National Cancer Registry 2016-2017. Cancer Sci. 2023;114:2986–2992. doi: 10.1111/cas.15823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlabach M.R., Lin S., Collester Z.R., Wrocklage C., Shenker S., Calnan C., et al. Rational design of a SOCS1-edited tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy using CRISPR/Cas9 screens. J Clin Invest. 2023;133 doi: 10.1172/JCI163096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S.H., Lee J.Y., Lee T.H., Park S.H., Yahng S.A., Yoon J.H., et al. SOCS1 and SOCS3 are expressed in mononuclear cells in human cytomegalovirus viremia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Res. 2015;50:40–45. doi: 10.5045/br.2015.50.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoda H., Yokoyama A., Nishino R., Nakashima T., Ishikawa N., Haruta Y., et al. Overproduction of collagen and diminished SOCS1 expression are causally linked in fibroblasts from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:1004–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderkötter C., Kalden H., Luger T.A. Aging and the skin immune system. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1256–1262. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890460078009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao N.N., Zhang Z.Z., Ren J.H., Zhang J., Zhou Y.J., Wai Wong V.K., et al. Overexpression of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 L3 in hepatocellular carcinoma potentiates apoptosis evasion by inhibiting the GSK3β/p65 pathway. Cancer Lett. 2020;481:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkouteren J.A.C., Ramdas K.H.R., Wakkee M., Nijsten T. Epidemiology of basal cell carcinoma: scholarly review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:359–372. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J., Dai H., Zhang X., Liu S., Lin Y., Somani A.K., et al. Distinct transcriptomic landscapes of cutaneous basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Genes Dis. 2021;8:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiskopf D., Weinberger B., Grubeck-Loebenstein B. The aging of the immune system. Transpl Int. 2009;22:1041–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C., Goldstein D.R. Impact of aging on antigen presentation cell function of dendritic cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.E., Li Y., Hou J. Downregulation of SLC3A2 mediates immune evasion and accelerates metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28 doi: 10.1111/jcmm.18010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H., Matsubara K., Qian G.S., Jackson P., Groopman J.D., Manning J.E., et al. SOCS-1, a negative regulator of the JAK/STAT pathway, is silenced by methylation in human hepatocellular carcinoma and shows growth-suppression activity. Nat Genet. 2001;28:29–35. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S.J., Long Z.W. Effect of SOCS1 silencing on proliferation and apoptosis of melanoma cells: an in vivo and in vitro study. Tumour Biol. 2017;39 doi: 10.1177/1010428317694315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Huo C., Liu Y., Su R., Zhao Y., Li Y. Mechanism and disease association with a ubiquitin conjugating E2 enzyme: UBE2L3. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.793610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ma C.J., Ni L., Zhang C.L., Wu X.Y., Kumaraguru U., et al. Cross-talk between programmed death-1 and suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 in inhibition of IL-12 production by monocytes/macrophages in hepatitis C virus infection. J Immunol. 2011;186:3093–3103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Huang J., Ma W., Yang W., Hu B. The antitumor activity of CAR-T-PD1 cells enhanced by HPV16mE7-pulsed and SOCS1-silenced DCs in cervical cancer models. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:6045–6053. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S321402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Cheng D., Li S., Zhou S., Yang Q. High expression of XRCC6 promotes human osteosarcoma cell proliferation through the β-catenin/Wnt signaling pathway and is associated with poor prognosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1188. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Zhang W., Huo S., Huang T., Cao X., Zhang Y. TUBB, a robust biomarker with satisfying abilities in diagnosis, prognosis, and immune regulation via a comprehensive pan-cancer analysis. Front Mol Biosci. 2024;11 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2024.1365655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Normalized RNA counts. Normalized RNA counts data were quantified using NanoString nCounter system (NanoString Technologies) with nCounter Human AutoImmune Profiling Panel. n = 12.

Heatmaps of normalized counts. Heatmaps are divided into 4 groups on the basis of Spearman correlation analysis using an r-value cutoff of 0.4. A total of 770 genes from the nCounter Human AutoImmune Profiling Panel were analyzed. Samples are arranged from left to right in order of increasing age. n = 12.

Adjusted P-values for 770 genes from the nCounter Human AutoImmune Profiling Panel. Adjusted P-values were calculated for all 770 genes using the Benjamini–Hochberg method for FDR correction. n = 12. FDR, false discovery rate.

Mean counts, log2FC, and adjusted P-values for each cluster in each sample analyzed with 10x Xenium. This dataset includes gene expression data for each cell cluster from our spatial transcriptomic analysis, including mean counts, log2FC, and adjusted P-values. Cluster names were manually annotated on the basis of marker genes described in the Materials and Methods. FC, fold change.

Total counts of each cluster in each sample analyzed with 10x Xenium. If SOCS1 expression is higher in that cluster than in the other clusters within the same sample (log2FC > 1) (Supplementary Data S4), it is highlighted in yellow. FC, fold change.

Panels used in our 10x Xenium analyses. The 260 genes were part of the predesigned Xenium Human Skin Gene Expression Panel, and an additional 50 genes were included in a custom panel (design ID: P3HCWE). ID, identification.

Data Availability Statement

The spatial transcriptome data were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan database with the accession numbers JGAS000771 for the study and JGAD000913 for dataset (https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/index-e.html). Other data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.