Highlights

-

•

There is a critical gap in effective laryngeal mucosal tissue regeneration.

-

•

Biopolymer scaffolds promote healing of laryngeal mucosa in a dog model.

-

•

PGS-treated wounds showed least granulation and best epithelial recovery.

-

•

Histology confirmed improved structure in PGS and alginate-treated defects.

-

•

Applied tissue engineering reduced fibrosis and enhances mucosal regeneration.

Keywords: Biopolymer, Laryngeal epithelium, Repair, Surgical incision

Abstract

Introduction

The airway mucosa plays a crucial role in protection and various physiological functions. Current methods for restoring airway mucosa, such as myocutaneous flaps or split skin grafts, create a stratified squamous layer that lacks the cilia and mucus-secreting glands of the native columnar-lined airway. This study examines the application of various injectable biopolymers as active molecules for a potential approach to regenerating laryngeal epithelial tissue.

Methods

The sample includes nine healthy dogs of the same breed. First, the medical engineering team prepared three types of biosynthetic materials (alginate, PGS, and chitosan) in a standard laboratory setting. After the induction of anesthesia in animals, the upper surface of the true vocal cords was bilaterally incised and denuded to create a uniform injury site. Biomaterials were applied to one side (intervention side), while the contralateral side served as the control and received no treatment. The length of the affected area after induction of injury, as observed in the microscopic view, was analyzed in relation to the effects of biomaterials, including epithelial hyperplasia, inflammation, granulation bed formation, angiogenesis, and fibroplasia.

Results

The mean standard deviation (SD) of epithelial hyperplasia scores, inflammatory scores, angiogenesis scores, and fibroplasia scores were not significantly different between the groups. However, the mean (SD) of granulation tissue bed score among the alginate [3.33 (1.15)], PGS [2.33 (0.58)], chitosan [3.33 (0.58)], and control [4.67 (0.58)] groups was significantly different between groups (p = 0.03).

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that a biopolymer has a positive effect on the repair of laryngeal epithelial tissue in an animal model without considering the impact of laryngeal movements.

Introduction

The vocal folds are functional organs located in the larynx that play a critical role in our daily breathing, speaking, and swallowing functions [1,2]. Vocal fold scarring, a specific vocal fold injury, is accompanied by a marked decrease in voice quality and control secondary to pathophysiologic changes of the vocal fold lamina propria extracellular matrix (ECM). These changes directly alter the vocal quality and create debilitating dysphonias due to a loss of normal vibratory function [3]. Fibrosis-induced vis-à-vis vocal fold scarring significantly increases stiffness and viscosity of the lamina propria, contributing to glottic incompetence [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. Treatment outcomes for patients with vocal fold ECM injury, loss, or scarring remain largely ineffective despite substantial remediation efforts that have been taken to date [5]. Surgery, as a leading cause of vocal fold scarring, was performed on the deeper layers of the lamina propria, and the vocal ligament is associated with scar tissue formation, trauma, or surgery [6].

Current methods aimed at restoring airway mucosa use either myocutaneous flaps or split skin grafts, resulting in a stratified squamous layer that lacks the ciliation and mucus-secreting glands of the columnar-lined airway. This is of particular concern within the upper respiratory tract, where poor mucociliary clearance necessitates daily nebulization and can lead to life-threatening airway obstruction due to mucus plugging. Grafting is associated with donor site morbidity and is limited by the suitability and availability of donor tissue. These limitations make flaps and grafting suboptimal or unsuitable for several portions of the airway, such as the trachea and larynx. Transplantation has been proposed for significant defects, but it is associated with severe morbidity from immunosuppression and has ethical and practical problems. Tissue engineering has been applied clinically to replace damaged sections of the trachea and larynx [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]]; however, the observed mucosa regeneration is slow and suboptimal, significantly limiting functional recovery. Developing an effective engineered mucosal solution would greatly extend the reach of these and other hollow organ replacement technologies. Indeed, effective early mucosalization may significantly shift the cost-benefit ratio in favor of commercial viability.

Based on fundamental tissue engineering principles, injectable, bioactive, and biodegradable polymers and hydrogels with appropriate chemical composition, structure characteristics, and tailored mechanical properties have been extensively employed to address voice disorders [9,10]. From a clinical perspective, this approach offers attractive advantages over traditional materials implantation, as it can potentially solidify injected materials into any desired shape at the injury site with enhanced interfacial interlocking with surrounding normal tissues. This strategy also minimizes the invasiveness and potential trauma to patients, limits the risk of infection and secondary scar formation, and reduces treatment costs with easy practice and increased patient accessibility [11]. Developing an optimal biomimetic matrix of bioactive molecules has become an increasingly important area of research in the fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. In this regard, several potential natural and synthetic biomaterials have been employed [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. Biomaterials such as collagen, alginate, chitosan, and synthetic polymers can be utilized for regenerating vocal folds. Poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) is a biodegradable and biocompatible polyester that has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and was first reported in 2002 by Wang et al. [16]. PGS has attracted attention for biomedical applications owing to its favorable combination of properties [17,18]. Chitosan is a marine–based polymer obtained by the deacetylation of chitin, which makes chitosan soluble in dilute acids. In contrast, alginate is extracted from brown seaweed and bacteria. The chitosan molecule contains amino and hydroxyl groups, and alginate has carboxyl groups, which confer a negative charge. Structurally, chitosan is similar to glycosaminoglycans, which are key components of the ECM [19,20]. This study aimed to determine the effect of bioactive molecules, including polysaccharides (chitosan/alginate)/synthetic polymers Poly(Glycerol Sebacate), on the repair status of laryngeal epithelial tissue in an animal model.

Materials and methods

Materials and sample preparation

Alginate and chitosan were obtained from Merck, Germany. Poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) resin was purchased from IZEPCO, IRAN. This study is an experimental intervention study using a nine-adult male mixed-breed dog model, weighing approximately 20–25 Kg. Healthy animals were evaluated and confirmed based on the opinion of a veterinary faculty team at Tehran University, Iran. The injectable biomaterial molecules were prepared using PGS, alginate, and chitosan under clean conditions. The animal ethical approval was obtained from the Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1399.886). All investigations were conducted by national guidelines and the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Animal studies

Animals were randomly assigned to three groups using the block randomization method (block size of 3), with each group receiving a specific biomaterial: PGS, alginate, or chitosan. Before the experiment, the animals adapted to the environment through a light/dark cycle. Animals were kept NPO (nothing by mouth) 6 h before surgery and were prevented from drinking water 2 h before surgery. Anesthesia was induced using a combination of ketamine (2mg/kg) and xylazine (5mg/kg) for preservation during surgery. Animals were intubated by a sterile animal surgeon under strict aseptic conditions.

To simulate the injury, a standardized defect (7–10 mm long and 2–3 mm wide) was created on the upper surface of the true vocal cords on both sides. Biomaterials (PGS, alginate, or chitosan) were applied to one side of the larynx, referred to as the intervention side. In contrast, the opposite side received no treatment and served as the control. This bilateral model allowed for a within-subject comparison between treated and untreated tissue. In the alginate group, the alginate was impregnated with one cc of alginate before application. In this study, the mean values of the contralateral (control) sides were considered as the control group for comparison in terms of epithelial hyperplasia, inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibroplasia scores. Animals were carefully monitored after surgery, with appropriate pain management protocols in place to ensure their well-being. Keeping the animals warm after anesthesia helped them recover before returning to their resting place.

After one week, animals were euthanized with sodium thiopental (100 mg/kg). Macroscopic images were taken after laryngectomy. Tissue samples were fixed in 10 % formalin for histopathological analysis. Microscopic sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, as well as histological slides, were examined for mucosal repair parameters, including epithelial hyperplasia, inflammation, granulation tissue, angiogenesis, and fibroplasia.

Histopathology

The larynges were harvested and fixed in 10 % neutral buffered formalin. Tissue samples (including coronal sections of the vocal folds) were processed and embedded in paraffin. Then, 5 mm thick sections were cut and stained using routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Masson’s trichrome staining (to determine collagen deposition), Verhoeff’s staining (to identify elastic fibers), and immunohistochemical staining for collagen type I (1:100; ab138492, Abcam). Stained sections were evaluated and photographed using a light microscope and digital camera system (Olympus CX33). The thickness of newly formed epithelium (µm) and granulation tissue in the lamina propria (mm) was measured at five different locations of each defect. Additionally, collagen deposition and disorganization of elastic fibers were scored semiquantitatively (0 = No, 1 = Mild, 2 = Moderate, 3 = Severe).

Statistical analysis

This study included three intervention groups and one control group. The minimum sample size of three animals per group was calculated using the Sample Size Calculation method. Quantitative data were summarized using means and standard deviations (SD), while qualitative data were presented as percentages. Group comparisons were performed using ANOVA or appropriate nonparametric tests, followed by post hoc analyses. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software version 22, with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results

The macroscopic appearance of vocal fold defects in the different treatment groups and their corresponding control (untreated) sides is demonstrated in Fig. 1. In the macroscopic evaluation of the vocal fold defects, untreated control sites exhibited swollen, edematous, and erythematous tissue at the defect area. In contrast, the treated sites demonstrated only mild erythema, with no evidence of protruding tissue masses. Among the treatment groups, PGS-treated defects showed the least macroscopic tissue changes compared to those treated with chitosan or alginate.

Fig. 1.

Macroscopic appearance of vocal fold defects. Untreated defects (left defects marked as control) showed swollen, edematous, and erythematous tissue in the defect area. Treated defects (Right defects marked as treatment) showed mild erythema, and no protruded tissue mass on the defect area was determined.

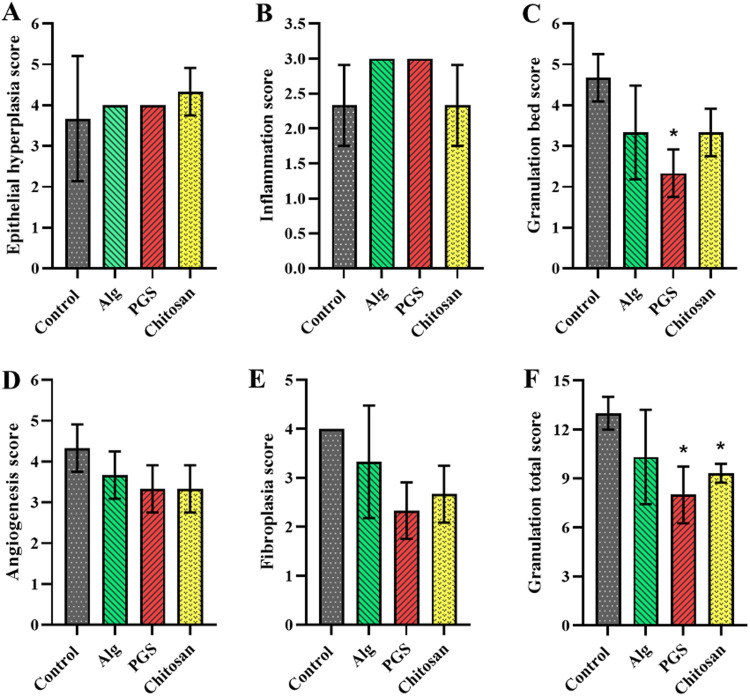

The obtained results from the epithelial hyperplasia score, as well as inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibroplasia score, revealed that no significant difference was observed between experimental groups (i.e., alginate, PGS, chitosan, and control). However, the granulation tissue bed score (SD) of alginate, PGS, chitosan, and control groups was recorded as 3.33 (1.15), 2.33 (0.58), 3.33 (0.58), and 4.67 (0.58), respectively, in which there was a significant difference between PGS and control group (p = 0.03). (Fig. 2). In addition, the granulation tissue total scores (SD) of the alginate, PGS, chitosan, and control groups were 10.33 (2.89), 8.00 (1.73), 9.33 (0.58), and 13.00 (1.00), respectively with a significant difference between PGS and chitosan groups compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Quantitative representation of epithelial hyperplasia (A), inflammation (B), granulation bed (C), angiogenesis (D), fibroplasia (E), and granulation total scores (F) related to control, alginate, PGS, and chitosan groups. All the experiments are performed in triplicate (n = 3); the data are shown as mean ± SD and * p < 0.05. Epithelial hyperplasia score, inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibroplasia, revealed no significant difference between the experimental groups. However, the granulation tissue bed score (SD) of alginate, PGS, chitosan, and control groups was recorded as 3.33 (1.15), 2.33 (0.58), 3.33 (0.58), and 4.67 (0.58), respectively, with a significant difference between the PGS and control group (p = 0.03). The granulation tissue total scores (SD) for the alginate, PGS, chitosan, and control groups were 10.33 (2.89), 8.00 (1.73), 9.33 (0.58), and 13.00 (1.00), respectively with a significant difference between PGS and chitosan groups compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

Histopathological evaluation revealed that the epithelialization completely covered the PGS- and alginate-treated defects, while chitosan-treated wounds showed partial re-epithelialization. In control (untreated) defects, no epithelial regeneration was detected except for limited areas of re-epithelialization just next to the wound edges. Epithelial thickness measurement revealed that the PGS significantly promotes epithelial reconstruction compared to the alginate and chitosan groups (p < 0.05).

The reparative (granulation tissue) depth within the lamina propria was measured in control and treated defects (Fig. 3). Control (untreated) and chitosan-treated defects, a large number of active fibroblasts, new small vessels, edema, and mononuclear inflammatory cells created significantly thicker granulation tissue than PGS-treated defects in which few fibroblasts were proliferated (p < 0.05). Although the alginate-treated defects showed relatively similar granulation tissue to that observed in the PGS, the inflammatory cell population was notably larger than that of the PGS group.

Fig. 3.

Representative photomicrographs of H&E-stained tissue sections of defect areas in treatment groups (alginate, chitosan, PGS) and untreated (control) defects. Epithelium (E) and its thickness are shown in the treatment groups. In the control defect, there is no reconstructed surface epithelium. Granulation tissue (G) extended from the epithelium to the deep lamina propria. Granulation tissue showed a greater extent and cellularity in the control and chitosan groups. Alginate showed more granulation tissue thickness and inflammatory cell infiltration than PGS-treated defects, in which a limited granulation tissue with minimal fibroblast population formed under a thick epithelium.

Fig. 4 represents the special stainings of the defect area. Elastic fibers in reparative tissue in lamina propria of the control and chitosan-treated defects completely disappeared, while some normal and relatively disorganized elastic fibers were determined in the defect area of PGS and alginate groups. Collagen-1 deposition was scored for all groups and showed abundant collagen-1 deposition in control defects, while in PGS, no collagen-1 deposition to mild deposition was found. Chitosan-treated defects showed mild to moderate collagen-1 deposition, and in alginate-treated wounds, mild distribution of collagen-1 was detected.

Fig. 4.

Special staining of defect area; Masson Trichrome staining for collagen matrix (blue color) formed in the defect areas of treated and untreated groups (A1, B1, C1, and D1), Verhoeff staining for detecting elastic fibers in the depth of reparative tissue of the defect area (A2, B2, C2, and D2) in which black thin fibers are shown in alginate (A2) and PGS (C2), immunostaining of defect areas for collagen-1 antibody (A3, B3, C3, and D3) is representing the most presence of collagen-1 in untreated control defect (D3).

Fig. 5 represents the comparisons between the control and treatment groups in terms of epithelial and granulation tissue thickness, collagen deposition, and elastic fibers disorganization.

Fig. 5.

Quantitative analysis of histopathological parameters in vocal fold defects after one week of treatment (n = 3 per group). Bar graphs showing mean ± SD with statistical significance indicated by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ANOVA with post-hoc tests); a) Epithelial thickness (μm) measured at five different locations per defect shows significantly greater epithelialization in PGS-treated defects compared to chitosan (*p < 0.05) and alginate (**p < 0.01) groups; b) Granulation tissue thickness (mm) in the lamina propria reveals significantly reduced granulation in PGS-treated defects compared to both control (***p < 0.001) and chitosan (**p < 0.01) groups, while control defects exhibited significantly thicker granulation tissue than alginate-treated defects (**p < 0.01); c) Semiquantitative scoring of collagen deposition (0=none to 3=severe) based on Masson’s trichrome staining demonstrates significantly higher collagen accumulation in control defects compared to PGS-treated defects (**p < 0.01), indicating increased fibrosis in untreated wounds; d) Semiquantitative assessment of elastic fiber disorganization (0=none to 3=severe) based on Verhoeff’s staining shows significantly greater preservation of standard elastic fiber architecture in PGS-treated defects compared to both chitosan (*p < 0.05) and control (*p < 0.05) groups.

Discussion

Failed repair and regeneration of the surgical site are among the most serious problems in the field of head and neck surgery, which can increase the risk of various complications, including adhesion, fibrosis, infection, inadequate recovery, and disease recurrence. The healing rate and quality of the surgical site can be influenced by various factors such as the surgeon's skill, suture materials, and post-operative care (10). Therefore, developing new strategies to improve the surgical site is of great importance for efficient improvement.

This study was designed and developed to evaluate the effect of alginate/PGS/chitosan hydrogel on the healing efficiency of surgical cuts of the laryngeal epithelium tissue in an animal model. By leveraging the benefits of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, the repair of surgical sites can be accelerated and enhanced both structurally and functionally. It is worth noting that tissue engineering can facilitate and improve the replacement or regeneration of tissues and organs by leveraging cells (e.g., stem cells and differentiated autologous cells), as well as reparative bioactive molecules (e.g., growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines) (11). Hence, organ failure can be overcome by implanting engineered tissues, semi-artificial or whole organs that mimic the function of native tissues (12). In this sense, bioactive molecules are key components that, if properly prepared, can lead to successful tissue regeneration even without cells and growth factors by attaching to the target site within the body.

Using this approach, successful reports have been published on cricoid cartilage reconstruction [14], trachea [15], nasal septal mucosa [21], and peripheral nerves [22]. Choi et al. [21] utilized silicone sheets and a hyaluronic acid composite to improve mucosal lesions in rabbit animal models. This study revealed that the lesion's average diameter in the control and silicone group reduced significantly during the five weeks post-surgery (i.e., from 5.1 to 0.05 and 4.35 to 0, respectively). Consistent with our results, they observed no significant difference in the epithelial thickness of treated animals vs. controls. In another in vivo study performed on a dog animal model, a new tracheal prosthesis was developed using a Prolene mesh that was reinforced with polypropylene rings and coated with gelatin [23]. The luminal surface of the construct was lined with autologous oral mucosa. Histological analysis of the transplanted prosthesis demonstrated a fully incorporated and vascularized graft after six months, by which a ciliated columnar epithelium was generated. Taking advantage of autologous cells and tissue-engineered constructs, autologous nasal respiratory epithelial cells and fibroblasts were resuspended in autologous fibrin to regenerate the tracheal epithelium in a sheep model [24]. Macroscopic and microscopic evaluations revealed a significant decrease in mucosal fibrosis in the experimental group (7 %) compared to the control group (71.8 %). This lessened fibrosis may be related to the function of autologous transplanted cells in the regeneration of native tissue. In this regard, the laryngeal mucosa MSCs were transplanted to the damaged vocal fold of dog models, which were differentiated into myofibroblasts and fibroblasts [[24], [25], [26], [27]]. The obtained data showed that these cells could modulate extracellular matrix production by reducing collagen synthesis and fibrosis, thereby preventing the decrease in elastic fibers and lessening inflammatory reactions within the healing microenvironment, which can result in the scarless formation of vocal folds. Another study [25] decellularized porcine larynges chemically and enzymatically under negative pressure and recellularized them with human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hBM-MSCs). The histological results demonstrated promoted epithelialization with no adverse effects on respiratory function. Highlighting the role of bioactive molecules, a propylene and collagen-based construct was pre-clotted and wrapped with autologous fascia lata and grafted to the laryngeal defect in a dog animal model [28,29]. Three months post-implantation, the tissue-engineered bioactive molecules were covered entirely with regenerated mucosa, while the muscle flap of control cases was repaired by scarred mucosa. However, based on histological results, a lined epithelium, subepithelial, and muscle tissue were regenerated in both the experimental and control groups.

It is worth noting that a significant advantage of tissue engineering strategies is the local application of therapeutic constructs at the damaged site. For instance, an injectable alginate and hyaluronic acid hydrogel containing basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) was developed and injected into the laryngeal muscles of Sprague-Dawley rats. After 4 and 12 weeks, the bFGF-loaded hydrogel promoted the expression of myogenic regulatory factor-related genes, hypertrophy of muscle fibers, growth of muscle satellite cells, increased angiogenesis, and decreased interstitial fibrosis, resulting in successful glottal gap closure [30]. Generally, several approaches have been developed to reconstruct the surgical site of the larynx. However, there are still many challenges in choosing the appropriate treatment because surgeons face many problems, such as poor voice function after surgery and the demand for repeated operations to achieve proper laryngeal reconstruction.

Among the factors contributing to unfavorable surgical outcomes are the challenges in reconstructing delicate tissues and structures, the difficulty in restoring the native contour of the larynx, and the risk of infections [[31], [32], [33]]. Although autologous tissue and homografts have been used as implant materials for larynx reconstruction, the damage caused to the surgical site or the difficulty of surgical procedures necessitates more efficient clinical treatment approaches [34,35]. In addition, in cases where the tumor is present and invades the larynx, the deformities of the reconstructed site often make it challenging to monitor the tumor and check for its recurrence. In this regard, new restorative approaches for tissue regeneration are promising to overcome these challenges. Among the limitations of the present study, we can mention the use of animals, which may affect the ability to generalize the results to humans. The small sample size was another obstacle of the present study, as ethical principles limited it and prevented it from including a larger number. Another limitation of this study is the within-animal control design, in which the contralateral vocal fold served as the untreated control. At the same time, this approach reduces inter-individual variability and adheres to ethical principles; it may be subject to local or systemic cross-effects that could influence tissue healing and confound comparisons.

Future studies should incorporate functional assessments with more extended follow-up periods (4–12 weeks), including high-speed videolaryngoscopy for mucosal wave evaluation, acoustic analysis of phonation, and mucociliary clearance assessment, to establish clinical relevance. In addition, future studies building on this work will incorporate immunomodulatory analysis (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10), degradation kinetics assessment, growth factor profiling (TGF-β1, VEGF, PDGF), epithelialization markers, and broader gene expression analysis to elucidate the pathways involved in the observed healing differences. These enhancements will help refine biomaterial design and optimize translational potential for future laryngeal tissue engineering applications.

Conclusions

Related fields, such as regenerative medicine and tissue engineering, have been established to accelerate the improvement of surgical sites and enhance the functioning of the operated tissue. In fact, by combining stem cells and bioactive molecules with suitable growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines, these sciences can be used to improve, replace, or regenerate tissues and organs. Based on the results of the present study and other studies conducted on animals, it appears that techniques based on biopolymer methods have a positive effect on the healing process of surgical cuts in laryngeal epithelium tissue.

Funding

This study was supported by the ENT and Head and Neck Research Center and Department, the Five Senses Health Institute, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Medical writing/editorial assistance

This manuscript was edited with the assistance of Grammarly and ChatGPT for English copy editing.

Ethical approval

The ethical committee at the Iran University of Medical Sciences approved this study (IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1399.886).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohsen Salary: Writing – original draft, Validation, Resources. Saleh Mohebbi: Visualization, Supervision, Project administration. Aslan Ahmadi: Project administration, Investigation. Zohreh Bagher: Writing – original draft, Visualization. Mohamad Pezeshki-Modaress: Visualization, Methodology. Hossein Aminianfar: Formal analysis. Saeed Farzad‐Mohajeri: Resources, Formal analysis. Nazanin Samiei: Resources. Farzad Taghizadeh-Hesary: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Hadi Ghanbari: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable

Contributor Information

Farzad Taghizadeh-Hesary, Email: farzadth89@gmail.com, taghizadeh_hesary.f@iums.ac.ir.

Hadi Ghanbari, Email: ghanbari_MD@iums.ac.ir.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Dekker J., Rossen J.W., HA B. The MUC family: an obituary. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:126–131. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martini H., Bartholomew E.F. Pierson; London: 2011. Essentials of anatomy & physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levendoski E.E., Leydon C., Thibeault S.L. Vocal fold epithelial barrier in health and injury: a research review. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2014;57:1679. doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-S-13-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miri A.K., Li N.Y.K., Avazmohammadi R., Thibeault S.L., Mongrain R., Mongeau L. Study of extracellular matrix in vocal fold biomechanics using a two-phase model. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14:49. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benninger M.S., Alessi D., Archer S. Vocal fold scarring; current concepts and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;115:474–482. doi: 10.1177/019459989611500521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo P., Casper J., Colton R., Brewer D. Diagnosis and treatment of persistent dysphonia after laryngeal surgery: a retrospective analysis of 62 patients. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1084–1091. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rakhorst G., Ploeg R. World Scientific Publishing Co., Inc; 2008. Biomaterials in modern medicine: the groningen perspective.https://catalog.nlm.nih.gov/discovery/fulldisplay/alma9913166183406676/01NLM_INST:01NLM_INST [Online]. Available. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heness G., Ben-Nissan B. Innovative bioceramics. Mater Forum. 2004;27:104–114. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green F.R., Shubber N.M., Koumpa F.S., Hamilton N.J.I. Regenerative medicine for end-stage fibrosis and tissue loss in the upper aerodigestive tract: a twenty-first century review. J Laryngol Otol. 2021;135:473. doi: 10.1017/S002221512100092X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guha G., Saha S., Kundu I. Surgical repair of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistulas. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007;59(2):103–107. doi: 10.1007/s12070-007-0032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vacanti J.P., Langer R. Tissue engineering: the design and fabrication of living replacement devices for surgical reconstruction and transplantation. The lancet. 1999;354 doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)90247-7. S32-S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giardino R., Aldini N.N., Torricelli P., Fini M., Giavaresi G., Rocca M. A resorbable biomaterial shaped as a tubular chamber and containing stem cells: a pilot study on artificial bone regeneration. Int J Artif Organs. 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bianco P., Robey P.G. Stem cells in tissue engineering. Nature. 2001;414(6859):118–121. doi: 10.1038/35102181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omori K., et al. Cricoid regeneration using in situ tissue engineering in canine larynx for the treatment of subglottic stenosis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2004;113(8):623–627. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omori K., Nakamura T., Kanemaru S., Magrufov A., Yamashita M., Shimizu Y. In situ tissue engineering of the cricoid and trachea in a canine model. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2008;117(8):609–613. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y., Ameer G.A., Sheppard B.J., Langer R. A tough biodegradable elastomer. Nat. Biotechnol. Jun. 2002;20(6):602–606. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arabsorkhi-Mishabi A., Zandi M., Askari F., Pezeshki-Modaress M. Biocompatible poly(glycerol sebacate) base segmented co-polymer with interesting chemical structure and tunable mechanical properties: in vitro and in vivo study. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. Aug. 2023;140(29) doi: 10.1002/app.54064. e54064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogt L., Ruther F., Salehi S., Boccaccini A.R. Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) in Biomedical Applications-A review of the recent literature. Adv. Healthc. Mater. May 2021;10(9) doi: 10.1002/adhm.202002026. e2002026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H., et al. Covalently antibacterial alginate-chitosan hydrogel dressing integrated gelatin microspheres containing tetracycline hydrochloride for wound healing. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Jan. 2017;70:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chahsetareh H., et al. Alginate hydrogel-PCL/gelatin nanofibers composite scaffold containing mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes sustain release for regeneration of tympanic membrane perforation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. Mar. 2024;262 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130141. Pt 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi K.Y., et al. Healing of the nasal septal mucosa in an experimental rabbit model of mucosal injury. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. Mar. 2017;3(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stocco E., et al. Development and preclinical evaluation of bioactive nerve conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration: a comparative study. Mater. Today Bio. Oct. 2023;22 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suh S.W., Kim J., Baek C.H., Han J., Kim H. Replacement of a tracheal defect with autogenous mucosa lined tracheal prosthesis made from polypropylene mesh. ASAIO J. 2001;47(5):496–500. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200109000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heikal M.M., Aminuddin B., Jeevanan J., Chen H., Sharifah S., Ruszymah B. Autologous implantation of bilayered tissue-engineered respiratory epithelium for tracheal mucosal regenesis in a sheep model. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;192(5):292–302. doi: 10.1159/000318675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ansari T., Lange P., Southgate A., Greco K., Carvalho C., Partington L. Stem cell-based tissue-engineered laryngeal replacement. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017;6(2):677–687. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2016-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L., Stiadle J.M., Lau H.K., Zerdoum A.B., Jia X., Thibeault S.L. Tissue engineering-based therapeutic strategies for vocal fold repair and regeneration. Biomaterials. 2016;108:91–110. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng H., Ming L., Yang R., Liu Y., Liang Y., Zhao Y. The use of laryngeal mucosa mesenchymal stem cells for the repair the vocal fold injury. Biomaterials. 2013;34(36):9026–9035. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hertegård S. Tissue engineering in the larynx and airway. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016;24(6):469–476. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamashita M., S-i K., Hirano S., Umeda H., Kitani Y., Omori K. Glottal reconstruction with a tissue engineering technique using polypropylene mesh: a canine experiment. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2010;119(2):110–117. doi: 10.1177/000348941011900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi Y.H., Kim S.H., Kim I.G., Lee J.H., Kwon S.K. Injectable basic fibroblast growth factor-loaded alginate/hyaluronic acid hydrogel for rejuvenation of geriatric larynx. Acta Biomater. 2019;89:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samandari Najafabadi M., Shahrabi Farahani S., Kheirollahi H. Histological evaluation of human amniotic membrane graft on oral keratinizing mucosa in the rabbit model (A pilot study. J. Dent. Med. 2007;20(2):144–149. [Google Scholar]

- 32.CONLEY J. One-stage radical resection of cervical esophagus, larynx, pharynx, and neck, with immediate reconstruction. AMA Arch. Otolaryngol. 1953;58(6):645–654. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1953.00710040672001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Som M. Reconstruction of the larynx and the trachea; report of a case of extensive cicatrical stenosis. J. Mt. Sinai Hosp. N. Y. 1951;17(6):1117–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biacabe B., Crevier-Buchman L., Hans S., Laccourreye O., Brasnu D. Vocal function after vertical partial laryngectomy with glottic reconstruction by false vocal fold flap: durational and frequency measures. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(5):698–704. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biacabe B., Crevier-Buchman L., Laccourreye O., Hans S., Brasnu D. Phonatory mechanisms after vertical partial laryngectomy with glottic reconstruction by false vocal fold flap. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2001;110(10):935–940. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.