Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), one of the most aggressive forms of pancreatic cancer, is associated with poor survival outcomes and currently ranks as the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Despite its clinical significance, the mechanisms of PDAC development and progression remain, in part, poorly understood. In this study, we provide evidence of a novel role of sorting nexin 10 (SNX10), a member of the sorting nexin family, in the regulation of KRAS-induced pancreatic carcinogenesis. We demonstrate that SNX10 is downregulated in PDAC, especially in advanced cases. Furthermore, mutational analysis revealed SNX10 genetic alterations in PDAC cases. Functional studies demonstrated that SNX10 overexpression in human PDAC cells inhibited cell proliferation and colony formation. Moreover, SNX10 overexpression induced G1-phase cell-cycle arrest and decreased KRAS signaling activity. Using a novel Snx10 knockout mouse crossed with a Kras-driven PDAC model, we observed reduced survival, increased tumor cell proliferation, enhanced aggression, and heightened inflammation. Collectively, these findings highlight SNX10 as a tumor suppressor candidate in PDAC and underscore its promise as a foundation for new therapeutic approaches.

Significance:

SNX10 plays a crucial role in reducing pancreatic tumorigenesis. This discovery offers valuable insights into PDAC’s biology and the development of new effective treatments.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most frequent histologic subtype of pancreatic cancer, is a dismal condition, currently ranking as the third leading cause of cancer-related fatalities (1–3) with a 5-year survival rate of 13% (4). The PDAC mutational and epigenetic landscapes have been extensively described over the past three decades (5). However, our understanding of the mechanisms underlying PDAC pathobiology, particularly the effectors controlling KRAS-induced PDAC initiation, remains, in part, poor. This carries significant disease relevance, as KRAS is mutated in nearly 90% of PDAC cases, and it has been demonstrated to be sufficient to initiate PDAC development (6). Consequently, increasing the knowledge of the molecular events underlying KRAS oncogenic function is essential for developing more promising therapeutic targets for this dismal condition.

In this study, we define a novel role of sorting nexin 10 (SNX10) as a candidate tumor suppressor in PDAC. SNX10 belongs to a family of phosphoinositide-binding proteins participating in cargo sorting and protein trafficking along the endocytic pathway (7). Characterization of the Snx10 knockout mouse model is essential for osteoclast formation and function (7). Moreover, we also illustrate that SNX10 interacts with PIKFYVE and FKBP12, key regulators of lysosomal biogenesis and vesicular trafficking (8, 9). Recently, we showed that SNX10 is essential for adipogenesis in human mesenchymal stem cells and is associated with waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for body mass index in women (10). In malignant disease, SNX10 has been reported to be downregulated in gastrointestinal malignancies, including PDAC, suggesting a potential tumor suppressor function (11–18). However, its role in cancer development remains underexplored. We have demonstrated that SNX10 expression decreases as PDAC progresses. Overexpression (OE) of SNX10 in human PDAC cells reduced cell proliferation. Furthermore, we found that SNX10 deficiency in genetically engineered mouse models promotes Kras-driven pancreatic tumorigenesis and reduces survival rates. Together, these findings establish SNX10 as a novel candidate tumor suppressor in PDAC, potentially antagonizing KRAS oncogenic function.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human pancreatic cancer cell lines: AsPC-1 (RRID: CVCL_0152), HPAF-II (RRID: CVCL_0313), PANC1 (RRID: CVCL_0480), Panc 05.04 (RRID: CVCL_1637), MiaPaCa2 (RRID: CVCL_0428), HPAC (RRID: CVCL_3517), and BXPC3 (RRID: CVCL_0186), were purchased from the ATCC. AsPC-1, Panc 05.04, and BXPC3 were grown in RPMI 1640 media (ATCC, #30-2001). HPAF-II was cultured in Eagle minimum essential medium (ATCC, #30-2003). All cell lines were grown in a medium supplemented with 5% FBS (Cytiva, #SH30396.03) and 1% antibiotic (Gibco, #15140122). PANC1 and MiaPaCa2 were grown in DMEM (ATCC, #30-2002), supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% antibiotic. HPAC cells were grown in DMEM with high glucose and Ham’s F-12 medium (1:1 mixture; ATCC, #30-2006), supplemented with 0.002 mg/mL insulin (Gibco, #12585014), 0.005 mg/mL transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich, #T8158), 40 ng/mL hydrocortisone (STEMCELL Technologies, #74142), 10 ng/mL mouse EGF (STEMCELL Technologies, #78016.1), 5% FBS, and 1% antibiotic at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 (RRID:SCR_026100). All cell lines were authenticated by a short tandem repeat method. All cell lines were tested negative for Mycoplasma contamination using the MycoProbe Mycoplasma Detection Kit (R&D Systems, # CUL001B) at the beginning of each experiment, and cells were cultured for no more than eight passages for all the experiments.

Generation of PDAC mouse models

All animal experiments were performed by and under the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at our institution. These studies were compliant with all federal and local guidelines. Mice of mixed background FVB/C57BL6 were used in animal studies. KrasG12D/+; P48-Cre (KC; RRID:MGI:2670727) and the KrasLSL.G12D/+; Trp53LSL.R172H/+; P48-Cre mice (KPC; RRID: IMSR_JAX:008179) have been previously described in detail (19, 20). The generation of Snx10fl/fl mice was previously described in detail (21). In our study, we generated a pancreas-specific Snx10 deletion by crossing P48Cre mice (RRID: IMSR_JAX:023329) with Snx10fl/fl mice (RRID:IMSR_NM-CKO-226489) to generate P48-Cre; Snx10fl/fl(CSfl/fl) mice for studying the effect of Snx10 loss alone. To assess tumor initiation, we created the KrasG12D/+; P48Cre; Snx10fl/fl (KCS) model by crossing a male KC with a female CSfl/fl mouse. For tumor progression analysis, we developed the KrasG12D/+; P48Cre; Snx10fl/fl; Trp53fl/+ (KPCS) model by crossing a male KPC with a female CSfl/fl mouse. Although intermediate strains such as CSfl/+, KCSfl/+, and KPCSfl/+ were produced during breeding, only homozygous CSfl/fl, KCSfl/fl, and KPCSfl/fl mice were included for further experimental study. To ensure accurate genotyping, all mouse lines used in this study were first validated through TransnetYX, Inc. using qPCR, a genotyping method that determines wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous floxed alleles. Based on the genotyping results, 8- to 9-week-old healthy mice were included randomly in a mixture of males and females for all the experiments. A total of 10 to 14 mice were aged for survival, and Kaplan–Meier curves were generated per genotype. All mice included in the survival analysis were euthanized when they reached the endpoint or were 104 weeks old. The maximum tumor burden was limited to less than 2 cm in any direction, and this burden limit was not exceeded in the whole study. Pancreatic tumors were harvested and analyzed using gross pathology, histology, and molecular levels (mRNA and protein levels). Genomic DNA was also isolated from the pancreatic tissue to reconfirm the loss of genes in the mouse pancreas. Further recombination was confirmed by PCR for the final experimental strains. The wild-type Snx10 was at 224 bp, the Snx10fl/fl band was at 273 bp, the LSL-KrasG12D bands were at 500 bp, and the P53fl/+ was at 612 bp. The recombination primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from all PDAC cell lines and mouse tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, #15596026), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The purity and integrity of total RNA were confirmed by NanoDrop [Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (RRID:SCR_020309)]. For cDNA synthesis, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, #4368814). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on the QuantStudio 3 qPCR System (RRID:SCR_018712) using the TaqMan probes and fast advanced master mix (Applied Biosystems, #4444556). Thermal cycling parameters were as follows: 50°C for 2 minutes, with an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 20 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 second, annealing, and elongation at 60°C for 20 seconds. The expression relative to β-actin or RPL13A was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt comparative cycle threshold method to calculate the fold increase (22). For the human PDAC cell line, normal human pancreas RNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, # QS0621) was used as a control compared with all PDAC cell lines. The primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Immunofluorescence

The unstained tissue microarray (TMA) slide was deparaffinized and rehydrated. For antigen retrieval, the slide was incubated in a 6.0 pH buffer (Reveal Decloaking reagent, Biocare Medical) for 30 minutes at 95°C to 98°C. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by slide immersion in a 3% hydrogen peroxide/Tris buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST) solution. The slide was incubated in a blocking solution for 30 minutes. Next, the slide was incubated in conjugated primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The following day, the slide was washed with TBST and coverslipped using a diamond antifade mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen, #62248). The images were captured using a ZEISS Axio Imager M2 microscope (RRID:SCR_024706) and analyzed using ImageJ (RRID:SCR_003070), including parameters (Supplementary Table S2). The antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Tissue processing, histopathology, and IHC analysis

Freshly isolated pancreata are fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and stored in 70% ethanol. Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4 μm thick), and mounted on glass slides. For histopathology staining, slides were deparaffinized and hydrated. Slides were stained with Harris hematoxylin (made in BLS Histology Laboratory), rinsed in tap water, and dipped in ammonia water for bluing. The slides were counterstained with eosin Y (made in BLS Histology Laboratory) for 1 minute, dehydrated with 100% ethanol, and washed with xylene 3 times. After that, the slides were mounted with mounting media and coverslipped. Images were captured using a ZEISS Axio Imager M2 microscope (RRID:SCR_024706). Slides were blindly evaluated and scored by an expert pathologist (C.E. Hagen).

For IHC, antigen retrieval was performed by incubating slides in 6.0 pH citrate buffer (Reveal Decloaking reagent, Biocare Medical) for Ki-67 and F4/80 and EDTA 8.0 pH buffer for cytokeratin 19 (CK19) for 30 minutes at 95°C to 98°C. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution. Slides were blocked using Rodent Block M solution (Biocare Medical) for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT). Slides were incubated in primary antibody for 60 minutes at RT. After that, slides were washed with 1× TBST 3 times and incubated in a secondary antibody solution for 30 minutes at RT. All slides were washed with 1× TBST, incubated in avidin–biotin complex (Vector Laboratories), and detected with diaminobenzidine (BioLegend). Slides were counterstained with CAT Hematoxylin (Biocare Medical) for 5 minutes, dehydrated, and coverslipped. Images were captured using a ZEISS Axio Imager M2 microscope (RRID:SCR_024706). The antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table S1. For Masson’s trichrome staining, tissue sections were deparaffinized and hydrated in water. Sections were mordanted in preheated Bouin’s solution overnight at RT and then stained with Weigert’s iron hematoxylin for 10 minutes. After rinsing and washing, sections were stained with Biebrich scarlet–acid fuchsin for 2 minutes, followed by 15 minutes in phosphotungstic–phosphomolybdic acid solution. Slides were then stained with aniline blue for 5 minutes, treated with 1% acetic acid for 5 minutes, dehydrated sections, washed with xylene, and coverslipped using a synthetic mounting media. Images were captured using a ZEISS Axio Imager M2 microscope (RRID:SCR_024706). QuPath software (RRID:SCR_018257) was used to quantify the number of positive cells (nuclear brown signal) relative to the total number of cells for CK19, Ki-67, and F4/80 stains. For the Masson’s staining, the total blue signal of collagen over the entire tissue area was measured in each slide. Parameters applied for image analysis in QuPath are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Validation of the QuPath analysis was done blindly by an expert pathologist (C.E. Hagen).

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Human PDAC cells or mouse tissues were lysed in 1× RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #89900) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #78440), incubated for 30 minutes on ice, and then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C, as described previously (8). Total proteins were quantified using a Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, #5000002) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A total of 40 µg of protein was electrophoresed on a 4% to 15% gradient polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, #4561084) with SDS and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #88520). Membranes were blocked in 1× TBST (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #28360) with 5% nonfat milk (Bio-Rad, #1706404) and probed with primary antibodies. Bound proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies and SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #34075) using the iBright CL1500 Imaging System (Invitrogen; RRID:SCR_026565). Bands were quantified using ImageJ software (RRID:SCR_003070). The antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

SNX10 plasmid transfection, cell viability, and proliferation assay

AsPC1, HPAF-II, and PANC1 cells were transfected with 1 μg of SNX10 plasmid (NM_013322, Human Tagged ORF Clone, OriGene, cat. # RC206019; https://cdn.origene.com/datasheet/rc206019.pdf) and empty vector (OriGene; #pCMV6; RRID: Addgene_133867) using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Sigma, #6366244001) and Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #31985062) for 24 hours, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were plated for further experiments.

For the MTT assay, 4 × 103 cells/well were seeded in the 96-well plates after 24 hours of SNX10 transfection. Cell proliferation was measured at different time points (6, 24, 48, and 72 hours), as described previously (23).

For the cell growth assay, 3 × 103 cells/well were seeded in the 12-well plates after 24 hours of SNX10 transfection. Cell growth was measured at different time points (days 1, 3, 5, and 7). At each time point, cells were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin (Gibco, #25200072) and counted with the help of a hemocytometer (RRID:SCR_025846).

For the colony formation assay, 1,000 to 1,500 cells were plated into six-well plates and grown for 15 days. The colonies were fixed in methanol and acetic acid (1:1) for 20 minutes and then washed 3 times with 1× PBS. Fixed colonies were stained for 30 minutes with 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # 548629) prepared in methanol. Colonies were counted after gently washing the dye with tap water and air-drying at RT.

For the cell-cycle assay, AsPC1 and HPAF-II (3 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in six-well plates after 24 hours of SNX10 transfection. Cell-cycle analysis was performed at different time points: 24, 48, and 72 hours. The cells were collected by trypsinization, washed twice in 1× PBS, fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol dropwise, and stored at −20°C. After fixation, the cells were washed with cold 1× PBS twice and resuspended in 500 μL of ready-to-use FxCycle propidium iodide (PI)/RNase staining solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #F10797) for 15 to 20 minutes at RT, protected from light. The cells were then run on a flow cytometer, BD FACSymphony A3 Cell Analyzer (RRID:SCR_023644). Data were analyzed using Floreada.io (January 30, 2025; RRID:SCR_025286).

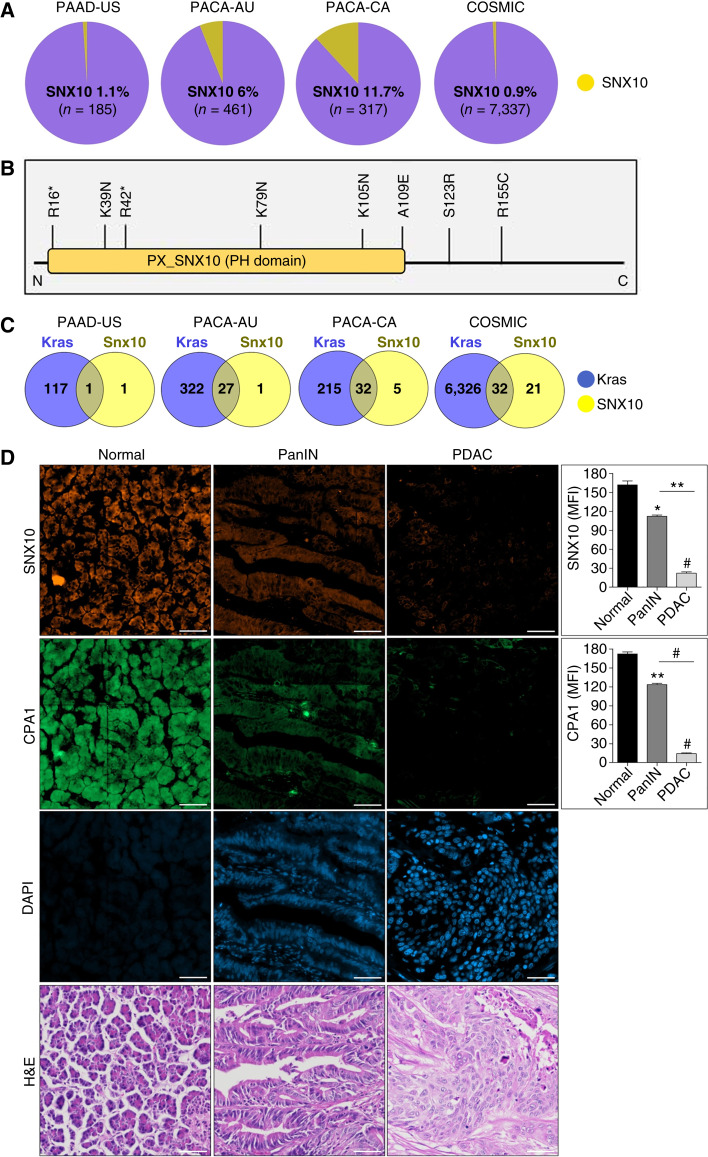

Human datasetsPI

The RNA sequencing data were downloaded from the Human Protein Atlas (RRID:SCR_006710) of patients with human PDAC [The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset, n = 176] and adjacent normal control tissues [The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) dataset, n = 328; refs. 24, 25]. The SNX10 genetic alterations in human PDAC were downloaded from the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC; RRID:SCR_021722) and the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC; RRID:SCR_002260). The following datasets with a total sample number are as follows: ICGC-PAAD-US, 185 samples (USA); ICGC-PACA-CA, 317 samples (Canada); ICGC-PACA-AU, 461 samples (Australia); and COSMIC, 7,337 samples (26, 27). The pie chart was generated using Canva (https://www.canva.com). Venn diagrams were created using Venny 2.1 (RRID:SCR_016561).

Tissue microarrays

A TMA comprising 80 samples, including various stages of pancreatic cancer and normal pancreatic tissue, was obtained from TissueArray.com (PA804a). The array includes information on pathology grade, tumor–node–metastasis classification, and clinical stage. Of the 80 samples, 35 are from early-stage cases, 35 are from mid-to-advanced stage cases, and 10 are normal pancreatic tissues. Each case is represented by a single core.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical significance between two groups was determined using an unpaired Student t test, two-tailed unless otherwise indicated. For multiple group comparisons, a one- or two-way ANOVA was performed, and Bonferroni’s posttests were employed to determine statistical differences from the control group unless otherwise indicated in the figure legend. For the survival data, power analysis was conducted to determine the sample size. Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted and compared using a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test, and a *, P < 0.05 was considered significant. Power analysis was performed using G*Power (RRID:SCR_013726). The statistical analysis and corresponding graphical representation were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (RRID:SCR_002798). Cell-cycle data were analyzed by Floreada.io (RRID:SCR_025286). All the experiments were performed as a set of three repeats for validation and expressed as mean ± SEM, and *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and #, P < 0.001 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

This study used publicly available datasets from COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), ICGC (https://dcc.icgc.org), TCGA via Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000086300-SNX10/cancer/pancreatic+cancer#PAAD_TCGA), and the GTEx dataset (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ ENSG00000086300-SNX10/tissue/pancreas). All data were accessed under the respective data usage policies. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials or from the corresponding author upon request.

Results

SNX10 genetic alterations and expression in human PDAC

We initially performed a detailed analysis of PDAC from the ICGC and the COSMIC datasets for SNX10 mutations. We found that somatic mutations were present in PDAC in 0.5% to 11% of the cases, depending on the dataset (Fig. 1A). A significant proportion of these mutations, including nonsense, missense, and substitution missense, were present within the coding region, including the Phox homology domain, a region critical for the regulation of SNX10 activity (Fig. 1B; refs. 28, 29). Further analysis of the datasets revealed that a significant proportion of SNX10 mutations cooccurred with Kras gain-of-function alterations (Fig. 1C). RNA sequencing data using PDAC samples (TCGA dataset, n = 176) and adjacent normal control tissues (GTEx dataset, n = 328) revealed a significant reduction in SNX10 expression in PDAC tissue (Supplementary Fig. S1A). IHC staining data comprising sections from cancer TMAs, sourced from the Human Protein Atlas database, confirmed a progressive decline in Snx10 protein expression as cancer advanced compared with normal tissues (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Validation using TMAs containing cases from various stages of PDAC, pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), and normal tissues showed a progressive reduction in SNX10 and carboxypeptidase A1 (CPA1) expression from PanIN through PDAC cases. CPA1 expression served as a positive control for normal cases (Fig. 1D). Finally, we examined SNX10 expression in human PDAC lines, AsPC-1, HPAF-II, PANC1, Panc05.04, MiaPaCa2, HPAC, and BXPC3 by qPCR. CPA1 and CK19 were used as positive controls for normal and tumor pancreas, respectively. Our results revealed that SNX10 is significantly decreased and CK19 expression is increased in all the PDAC cells compared with the normal pancreas (Supplementary Fig. S2A–S2C). Together, these results show the presence of mutations in key functional domains and reduced expression of SNX10, suggesting that this sorting may be relevant to the biology of PDAC.

Figure 1.

SNX10 genetic alterations and expression in human PDAC. A, Interrogation of PDAC from ICGC (https://dcc.icgc.org) and COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), showing mutations in the SNX10 gene. B, A schematic of the SNX10 gene shows the distribution of the mutations in the coding region (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic). C, Venn diagrams of SNX10 mutations that exist in conjunction with Kras gain-of-function alterations and overlap among SNX10 and Kras in PDAC (ICGC and COSMIC datasets; https://dcc.icgc.org/ and https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic). D, TMA of normal, PanIN, and PDAC samples (left) stained with fluorescent IHC for CPA1 (green) and SNX10 (orange) expression. Scale bar, 20 μm. Quantification (right) of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of SNX10 and CPA1. Results indicate a progressive reduction in SNX10 and CPA1 expression from PanIN through advanced PDAC stages. Statistically significant differences *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and #, P < 0.001 are represented as mean ± SEM. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; PH, Phox homology.

SNX10 OE suppresses cell proliferation

Based on the above findings, we sought to evaluate the effect of SNX10 on cell growth in KRAS mutant PDAC cells AsPC1 and HPAF-II. These cells were transfected with the SNX10 plasmid for 24 hours and analyzed by MTT, cell counting, and colony formation assay. The levels of OE were confirmed by qPCR and Western blot (Fig. 2A and B), showing that the SNX10 OE group had increased expression compared with the control cells transfected with the empty plasmid (control). Interestingly, OE of SNX10 in AsPC1 and HPAF-II cells led to a significant reduction in cell proliferation at 72 hours (Fig. 2C), cell numbers at days 5 and 7 (Fig. 2D), and fewer colonies compared with the control groups (Fig. 2E and F). We also found that in AsPC1 (Fig. 2G and I) and HPAF-II cells (Fig. 2H and J), the SNX10 OE group resulted in a significantly higher percentage of cells in the G1 phase at the 48- and 72-hour time points, whereas there was a significantly lower percentage of cells in the S-phase in the SNX10 OE group at 72 hours in the HPAF-II cells, but this was not significant in the AsPC1 cells compared with the control. Similar results were also seen in a PDAC line (Panc1), in which SNX10 OE results in reduced proliferation, total cell numbers, and colonies compared with the control group (Supplementary Fig. S3A–S3F). Finally, we determined the effect of OE of SNX10 on the levels of phosphorylation (as a measure of activation) of SRC (nonreceptor tyrosine kinase protein), STAT3, and ERK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), molecules known to promote or be downstream of oncogenic KRAS activity (30–33). All these molecules have significantly decreased levels in cells overexpressing SNX10 (Fig. 3A and B). These results support that SNX10 may play a tumor-suppressive role in mutant KRAS PDAC cells.

Figure 2.

OE of SNX10 decreased cell proliferation in AsPC1 and HPAF-II PDAC cell lines. A, SNX10 transfection confirmation in AsPC1 and HPAF-II cells by qPCR fold change expression. Actin was used as a reference gene. B, Western blot of control vs. SNX10 OE with GAPDH was used as loading control for cell lines AsPC1 (left) and HPAF-II (right). C, Cell proliferation via MTT (absorbance at 570 nm) of AsPC1 (left) and HPAF-II (right) over 72 hours. D, The growth curve assay of AsPC1 (left) and HPAF-II (right) determined the growth rate over 7 days. E, Representative images of control vs. SNX10 OE colony-forming ability in AsPC1 and HPAF-II cell lines. F, Quantification of colony numbers in each group observed in E. Cell-cycle analysis of OE of SNX10 in (G) AsPC1 and (H) HPAF-II cells by flow cytometry shows that the percentage of cells in the G1 phase (blue) is higher than in the G2 phase (red) and S-phase (green) in the SNX10 OE group compared with the control. Cell-cycle data were analyzed using Floreada.io https://floreada.io/analysis. I and J, Quantification of cell-cycle analysis of the SNX10 OE group at all time points (24, 48, and 72 hours) compared with the control group in both AsPC1 and HPAF-II cell lines. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and #, P < 0.001 are represented as mean ± SEM. MW, molecular weight; OD, optical density; PI-A, propidium iodide area.

Figure 3.

OE of SNX10 participated in regulating the protumorigenic protein expression. A, Western blot of control vs. SNX10 OE in AsPC1 and HPAF-II cell lines probing for the expression of protumorigenic markers. Protumorigenic markers probed for both total and phosphorylation of SRC, STAT3, and ERK expression and SNX10 (48 hours after treatment). Three independent western blots were performed, and the same blot was stripped for all the genes. B, Quantification of relative protein expression of genes in each group from A, with GAPDH used as a loading control. AsPC1 cell line is shown at the top, and HPAF-II at the bottom. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and #, P < 0.001 are represented as mean ± SEM. SNX10 OE was compared with the control group. MW, molecular weight.

SNX10 depletion promotes tumor progression and aggressiveness and reduces survival in PDAC mouse models

To define the impact of SNX10 in the biology of PDAC, we used a P48-driven Cre recombinase to delete Snx10 specifically in exocrine pancreatic tissues, both in the presence and absence of oncogenic Kras and Tp53 mutations to generate the CSfl/fl, KCSfl/fl, and KPCSfl/fl mouse models (Supplementary Fig. S4A). All lines used in this study were genotyped through a probe-based assay distinguishing wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous floxed alleles. Recombination was confirmed in pancreatic tissues by PCR (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Furthermore, we observed that SNX10 expression is significantly reduced in the CSfl/fl, KCSfl/fl, and KPCSfl/fl groups compared with the P48 Cre (control mice), KC, and KPC mice, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4C). Moreover, we measured SNX10 expression at the protein level and found that SNX10 expression significantly declined in the CSfl/fl, KCSfl/fl, and KPCSfl/fl groups, whereas it significantly reduced in the KPC group compared with control mice (P48 Cre; Supplementary Fig. S4D).

Analysis of the crosses revealed that the CSfl/fl group does not affect the survival of mice, P = 0.1672 (Supplementary Fig. S4E), and showed a normal pancreas based on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Supplementary Fig. S4F). In KPCSfl/fl (P = 0.0049) and KCSfl/fl (P = 0.0016) mice, the decreased expression of SNX10 lowers survival compared with KPC and KC animals, respectively (Fig. 4A and B). In addition, there was a significant increment in the pancreas weight and size of the KPCSfl/fl group compared with KPC (Fig. 4D and F); however, there was no significant difference in the pancreas weight and size of the KCSfl/fl group compared with KC (Fig. 4C and E). Comprehensive necropsy (isolated pancreas) of all PDAC mouse models revealed more aggressive disease in the KPCSfl/fl mice but not in the KCSfl/fl mice compared with KPC and KC, respectively. Our gross observation of CSfl/fl mice indicated a normal pancreas. In contrast, we observed more abnormalities/tumors in the pancreas of the KPCSfl/fl mice and KCSfl/fl compared with the KPC and KC mice (Supplementary Table S3), which was further confirmed by histopathology analysis.

Figure 4.

Loss of Snx10 leads to adverse outcomes in PDAC. Kaplan–Meier curves of (A) KC (n = 12) and KCSfl/fl (n = 12) group (P = 0.0016). B, KPC (n = 12) and KPCSfl/fl (n = 14) group (P = 0.0049). Survival analyses were performed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. C and D, Pancreas weight measured in KC (n = 12), KCSfl/fl (n = 12), KPC (n = 12), and KPCSfl/fl (n = 14). E and F, Pancreas size measured in KC (n = 12), KCSfl/fl (n = 12), KPC (n = 12), and KPCSfl/fl (n = 14). G and H, Representative hematoxylin and eosin stains of KC (n = 12), KCSfl/fl (n = 12), KPC (n = 12), and KPCSfl/fl (n = 14). Scale bar, 20 μm. I and J, Pie charts represent the percentage incidence of poorly differentiated, moderately differentiated, chronic pancreatitis, and well-differentiated in KC (n = 12), KCSfl/fl (n = 12), KPC (n = 12), and KPCSfl/fl (n = 14). Statistically significant differences *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and #, P < 0.001 are represented as mean ± SEM.

Next, we performed hematoxylin and eosin staining of pancreas tissues from the KC, KCSfl/fl, KPC, and KPCSfl/fl groups of all survival mice (Fig. 4G and H) and analyzed them based on cancer grades. Fifty percent of KPCSfl/fl animals developed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, while only 8% of KCSfl/fl animals developed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma compared with KPC and KC, respectively. The overall tumor occurrence was higher in KPCS (86%) compared with KPC (83%), as depicted in the pie chart (Fig. 4I and J) with detailed pathology analysis (Supplementary Table S4). We also examined common malignancy markers such as the ductal marker CK19, the proliferation marker Ki-67, the macrophage marker F4/80 to assess activated macrophages/inflammatory conditions, and the collagen fiber marker Masson’s trichrome staining during PDAC progression. We found that the expression of collagen fibers was significantly increased in the KPCSfl/fl mice compared with KPC, whereas the KCSfl/fl mice had no significant difference compared with KC (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, IHC of CK19 expression showed significantly higher expression in the KPCSfl/fl compared with KPC, but there was no significant difference in KCSfl/fl compared with KC (Fig. 5B). Also, we observed significantly higher Ki-67 expression in the KPCSfl/fl tissue compared with KPC, and KCSfl/fl had no significant difference compared with KC (Fig. 5C). Finally, IHC was performed to determine inflammation/activated macrophages (F4/80) in all genotypes and found significantly increased expression in the KPCSfl/fl and KCSfl/fl groups compared with KPC and KC, respectively (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, similar to in vitro findings, we found a substantially increased activation of ERK and STAT3 in KPCSfl/fl mice compared with KPC (Supplementary Fig. S5A and S5B). Altogether, our results demonstrated that the loss of SNX10 significantly reduced mice survival, modified the PDAC tumor microenvironment, and promoted tumor proliferation, thus further supporting the tumor suppressor function of this molecule in PDAC biology.

Figure 5.

Depletion of Snx10 enhances malignancy markers in PDAC mice: A–D, Number of mice per group: P48 Cre (control mouse, n = 4), KPC (n = 4), KPCSfl/fl (n = 4), KC (n = 4), and KCSfl/fl (n = 4; PDAC mouse). All scale bars, 100 μm. A, Masson’s trichrome staining representative (left) images and quantification (right) of total collagen (percentage of area fraction; blue signal). B, Representative IHC images (left) and quantification (right) for the ductal marker CK19 and percentage of positive cells (brown signal). C, Representative IHC images (left) and quantification (right) for the cell proliferation marker Ki-67 and percentage of positive cells (brown signal). D, Representative IHC images (left) and quantification (right) for the macrophage marker F4/80 and percentage of positive cells (brown signal). Significance levels *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and #, P < 0.001 are represented as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

SNX family proteins are generally involved in intracellular trafficking (34); their roles in cancer remain complex. Some members, such as SNX1, SNX6, and SNX27, have oncogenic properties, promoting proliferation and metastasis by activating the TGF-β signaling pathway and recycling cancer-associated proteins in gastric, pancreatic, and colon cancer, respectively (35–37). In contrast, SNX10 has been implicated as a tumor suppressor in gastric, colorectal, and liver cancers (11, 12, 14, 16–18) though its role in PDAC has remained unexplored. This study identifies SNX10 as a novel tumor suppressor candidate in PDAC. Our findings reveal that mutations in SNX10 occur in a significant proportion of PDAC tumors (0.5%–11.7%), with many cooccurring with KRAS gain-of-function mutations. KRAS is a well-established oncogene in PDAC, with mutations present in nearly 90% of cases (32, 38–40), driving tumorigenesis through activation of downstream signaling pathways such as MAPK, mTOR, and Ral (32, 33). SNX10 plays a crucial role in endosomal trafficking (34), a process known to regulate KRAS signaling (41). We observed that SNX10 expression is significantly downregulated in PDAC tissues compared with adjacent normal tissue, at both mRNA and protein levels. Given that alterations in other key tumor suppressors (CDKN2A, SMAD4, and TP53) contribute to PDAC progression (20, 42–45), our data suggest that SNX10 loss may act as a secondary or tertiary change in PDAC pathogenesis.

Previous studies indicated that SNX10 exerts tumor-suppressive effects by regulating autophagy through modulating lysosomal degradation pathways via cargo-mediated autophagy in colorectal cancer (18). Autophagy plays a dual role in pancreatic cancer by supporting tumor cell survival under stress and resistance against therapy (46, 47). Our current data do not address autophagic activity directly. We observed that SNX10 OE in human PDAC cells significantly reduced cell proliferation, tumor initiation, and protumorigenic protein activity. It also induced G1-phase cell-cycle arrest, further confirming its role in inhibiting tumor growth. Notably, SNX10 downregulates SRC activity, a key mediator of oncogenic signaling that interacts with receptor tyrosine kinases and G protein–coupled receptors, ultimately activating MAPK, STAT3, and mTOR pathways (12, 14, 18). Given that SRC activation is linked to KRAS mutations and PDAC progression (48–50), our findings suggest that SNX10 loss enhances oncogenic signaling through deregulated SRC activity.

Using a Snx10 knockout PDAC mouse model, we observed significantly increased tumorigenesis, tumor size, and aggressiveness, particularly in KPCSfl/fl mice. Previously reported PDAC mouse tissues exhibited greater tumor burden, enhanced CK19 expression (a ductal marker), and increased cell proliferation (Ki-67) and macrophage infiltration (F4/80+ tumor-associated macrophages), indicating a more aggressive tumor microenvironment compared with control mouse tissues (51–53). Notably, although KPCSfl/fl mice exhibited significantly worse outcomes and a higher incidence of disease compared with KPC mice, KCSfl/fl mice (lacking Snx10 but without the full KPC background) showed reduced survival but did not develop significantly larger tumors, suggesting that SNX10 loss alone is insufficient to drive aggressive PDAC. IHC analysis further confirmed that SNX10 depletion enhances desmoplasia, inflammation, and tumor proliferation. We observed increased collagen fiber deposition, heightened CK19 and Ki-67 expression, and a significant increase in tumor-associated macrophages in KPCSfl/fl mice compared with KPC controls. These findings indicated a more aggressive tumor microenvironment and increased stromal remodeling in the absence of Snx10. Additionally, the loss of SNX10 led to upregulation of key protumorigenic proteins, including ERK and STAT3. Interestingly, although phosphorylated ERK and STAT3 levels were significantly increased, only moderate changes were observed in total ERK and STAT3. This suggests that SNX10 loss contributes to PDAC progression primarily by activating the ERK and STAT3 pathways, major drivers of cell proliferation and survival in pancreatic cancer.

Our findings establish SNX10’s antitumor function in PDAC, with potential implications for treatment. Given that SNX10 expression is significantly reduced in PDAC tissues, it may serve as a potential therapeutic target. SNX10’s previously reported role in regulating autophagy suggests that it may similarly affect autophagic pathways in pancreatic cancer and contribute to tumor progression. However, further research is needed to elucidate this potential mechanistic connection in PDAC. Future studies should focus on investigating SNX10 expression and its correlation with clinical outcomes in samples from patients with PDAC as well as to identify its direct molecular targets and determining whether restoring SNX10 function can effectively inhibit tumor progression. It is important to evaluate how SNX10 loss influences PDAC metastasis. Although our current study focused primarily on macrophage-driven changes in the tumor microenvironment, the potential role of SNX10 in regulating cancer-associated fibroblasts and broader stromal remodeling permits further study. Although our findings suggest an interplay between SNX10 loss and activation of the SRC/ERK/STAT3 signaling pathways, this relationship remains unclear. Future studies are needed to determine the mechanism underlying this correlation, and whether pharmacologic targeting of the SRC, ERK, or STAT3 pathways can modulate the consequences of SNX10 loss may provide insights into potential therapeutic strategies for PDAC.

Conclusion

This study establishes SNX10 as a tumor suppressor candidate in PDAC, with its loss contributing to increased tumor growth, aggressiveness, and reduced survival. These findings highlight SNX10 as a potential therapeutic target. Further research on SNX10’s regulatory mechanisms may pave the way for novel treatment strategies aimed at improving patient outcomes in this highly lethal disease.

Supplementary Material

Supp Fig 1

Supp Fig 2

Supp Fig 3

Supp Fig 4

Supp Fig 5

Supp Table 1

Supp Table 2

Supp Table 3

Supp Table 4

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Minnesota. OpenAI was used for language refinement and manuscript editing. This research received assistance from BLS Histology Services at the University of Minnesota’s Biorepository and Laboratory Services program.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Communications Online (https://aacrjournals.org/cancerrescommun/).

Authors’ Disclosures

No disclosures were reported.

Authors’ Contributions

K. Khan: Conceptualization, data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. M. Shameem: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. A.N. Sigafoos: Data curation, formal analysis, writing–review and editing. L. Kiey: Data curation, validation, methodology. C.E. Hagen: Data curation, formal analysis, methodology. G. Ramakrishnan: Formal analysis, methodology, writing–review and editing. L. Morse: Resources, supervision, funding acquisition, project administration, writing–review and editing. M.E. Fernandez-Zapico: Conceptualization, supervision, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, project administration, writing–review and editing. R.A. Battaglino: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Rahib L, Wehner MR, Matrisian LM, Nead KT. Estimated projection of US cancer incidence and death to 2040. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e214708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:12–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025;75:10–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch AM, Chang DK, Kassahn KS, Bailey P, et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015;518:495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Jesus VHF, Mathias-Machado MC, de Farias JPF, Aruquipa MPS, Jácome AA, Peixoto RD. Targeting KRAS in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: the long road to cure. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu CH, Morse LR, Battaglino RA. SNX10 is required for osteoclast formation and resorption activity. J Cell Biochem 2012;113:1608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sultana F, Morse LR, Picotto G, Liu W, Jha PK, Odgren PR, et al. Snx10 and PIKfyve are required for lysosome formation in osteoclasts. J Cell Biochem 2020;121:2927–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Battaglino RA, Jha P, Sultana F, Liu W, Morse LR. FKBP12: a partner of Snx10 required for vesicular trafficking in osteoclasts. J Cell Biochem 2019;120:13321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansen GT, Sobreira DR, Weber ZT, Thornburg AG, Aneas I, Zhang L, et al. Genetics of sexually dimorphic adipose distribution in humans. Nat Genet 2023;55:461–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deng RR, Yuan YP. Ropivacaine inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of gastric cancer cells via the SNX10/SRC/STAT3 pathway. Chem Biol Drug Des 2024;103:e14405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feng H, Tan J, Wang Q, Zhou T, Li L, Sun D, et al. α-hederin regulates glucose metabolism in intestinal epithelial cells by increasing SNX10 expression. Phytomedicine 2023;111:154677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gerber MM, Hampel H, Zhou XP, Schulz NP, Suhy A, Deveci M, et al. Allele-specific imbalance mapping at human orthologs of mouse susceptibility to colon cancer (Scc) loci. Int J Cancer 2015;137:2323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Le Y, Zhang S, Ni J, You Y, Luo K, Yu Y, et al. Sorting nexin 10 controls mTOR activation through regulating amino-acid metabolism in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis 2018;9:666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cervantes-Anaya N, Ponciano-Gómez A, López-Álvarez GS, Gonzalez-Reyes C, Hernández-Garcia S, Cabañas-Cortes MA, et al. Downregulation of sorting nexin 10 is associated with overexpression of miR-30d during liver cancer progression in rats. Tumour Biol 2017;39:1010428317695932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang J, Wu Y, Jin HY, Guo S, Dong Z, Zheng ZC, et al. Prognostic value of sorting nexin 10 weak expression in stomach adenocarcinoma revealed by weighted gene co-expression network analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:4906–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang S, Hu B, You Y, Yang Z, Liu L, Tang H, et al. Sorting nexin 10 acts as a tumor suppressor in tumorigenesis and progression of colorectal cancer through regulating chaperone mediated autophagy degradation of p21(Cip1/WAF1). Cancer Lett 2018;419:116–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang S, Yang Z, Bao W, Liu L, You Y, Wang X, et al. SNX10 (sorting nexin 10) inhibits colorectal cancer initiation and progression by controlling autophagic degradation of SRC. Autophagy 2020;16:735–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell 2003;4:437–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell 2005;7:469–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ye L, Morse LR, Zhang L, Sasaki H, Mills JC, Odgren PR, et al. Osteopetrorickets due to Snx10 deficiency in mice results from both failed osteoclast activity and loss of gastric acid-dependent calcium absorption. PLoS Genet 2015;11:e1005057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001;25:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shameem M, Kumar R, Krishna S, Kumar C, Siddiqi MI, Kundu B, et al. Synthetic modified pyrrolo[1,4] benzodiazepine molecules demonstrate selective anticancer activity by targeting the human ligase 1 enzyme: an in silico and in vitro mechanistic study. Chem Biol Interact 2015;237:115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berglund L, Björling E, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, Asplund A, Szigyarto CA, et al. A genecentric Human Protein Atlas for expression profiles based on antibodies. Mol Cell Proteomics 2008;7:2019–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uhlén M, Björling E, Agaton C, Szigyarto CA, Amini B, Andersen E, et al. A human protein atlas for normal and cancer tissues based on antibody proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2005;4:1920–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang J, Bajari R, Andric D, Gerthoffert F, Lepsa A, Nahal-Bose H, et al. The international cancer Genome Consortium data portal. Nat Biotechnol 2019;37:367–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, Sondka Z, Beare DM, Bindal N, et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:D941–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qin B, He M, Chen X, Pei D. Sorting nexin 10 induces giant vacuoles in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 2006;281:36891–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu J, Qiu H, Zhao J, Pavlos NJ. The molecular structure and function of sorting nexin 10 in skeletal disorders, cancers, and other pathological conditions. J Cell Physiol 2021;236:4207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rozengurt E, Eibl G. Crosstalk between KRAS, SRC and YAP signaling in pancreatic cancer: interactions leading to aggressive disease and drug resistance. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Corcoran RB, Contino G, Deshpande V, Tzatsos A, Conrad C, Benes CH, et al. STAT3 plays a critical role in KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 2011;71:5020–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Padavano J, Henkhaus RS, Chen H, Skovan BA, Cui H, Ignatenko NA. Mutant K-RAS promotes invasion and metastasis in pancreatic cancer through GTPase signaling pathways. Cancer Growth Metastasis 2015;8(Suppl 1):95–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luo J. KRAS mutation in pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol 2021;48:10–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elson A, Stein M, Rabie G, Barnea-Zohar M, Winograd-Katz S, Reuven N, et al. Sorting nexin 10 as a key regulator of membrane trafficking in bone-resorbing osteoclasts: lessons learned from osteopetrosis. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021;9:671210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bao Z, Zhou S, Zhou H. Sorting nexin 27 as a potential target in G protein coupled receptor recycling for cancer therapy (Review). Oncol Rep 2020;44:1779–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hu P, Liang Y, Hu Q, Wang H, Cai Z, He J, et al. SNX6 predicts poor prognosis and contributes to the metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells via activating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2018;50:1075–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhan XY, Zhang Y, Zhai E, Zhu QY, He Y. Sorting nexin-1 is a candidate tumor suppressor and potential prognostic marker in gastric cancer. PeerJ 2018;6:e4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2008;455:1069–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bonnot PE, Passot G. RAS mutation: site of disease and recurrence pattern in colorectal cancer. Chin Clin Oncol 2019;8:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McFadden DG, Politi K, Bhutkar A, Chen FK, Song X, Pirun M, et al. Mutational landscape of EGFR-MYC-and Kras-driven genetically engineered mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:E6409–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu A, Tebar F, Alvarez-Moya B, López-Alcalá C, Calvo M, Enrich C, et al. A clathrin-dependent pathway leads to KRas signaling on late endosomes en route to lysosomes. J Cell Biol 2009;184:863–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bardeesy N, Aguirre AJ, Chu GC, Cheng KH, Lopez LV, Hezel AF, et al. Both p16(Ink4a) and the p19(Arf)-p53 pathway constrain progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:5947–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bardeesy N, Cheng KH, Berger JH, Chu GC, Pahler J, Olson P, et al. Smad4 is dispensable for normal pancreas development yet critical in progression and tumor biology of pancreas cancer. Genes Dev 2006;20:3130–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aguirre AJ, Bardeesy N, Sinha M, Lopez L, Tuveson DA, Horner J, et al. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev 2003;17:3112–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Izeradjene K, Combs C, Best M, Gopinathan A, Wagner A, Grady WM, et al. Kras(G12D) and Smad4/Dpc4 haploinsufficiency cooperate to induce mucinous cystic neoplasms and invasive adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer Cell 2007;11:229–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kimmelman AC, White E. Autophagy and tumor metabolism. Cell Metab 2017;25:1037–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang S, Wang X, Contino G, Liesa M, Sahin E, Ying H, et al. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes Dev 2011;25:717–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ishizawar R, Parsons SJ. c-Src and cooperating partners in human cancer. Cancer Cell 2004;6:209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Frame MC. Newest findings on the oldest oncogene; how activated src does it. J Cell Sci 2004;117:989–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Poh AR, Ernst M. Functional roles of SRC signaling in pancreatic cancer: recent insights provide novel therapeutic opportunities. Oncogene 2023;42:1786–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jeong S, Lee DH, Lee JI, Lee JW, Kwon KS, Kim PS, et al. Expression of Ki-67, p53, and K-ras in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:6765–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zuo C, Baer JM, Knolhoff BL, Belle JI, Liu X, Alarcon De La Lastra A, et al. Stromal and therapy-induced macrophage proliferation promotes PDAC progression and susceptibility to innate immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2023;220:e20212062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sigafoos AN, Tolosa EJ, Carr RM, Fernandez-Barrena MG, Almada LL, Pease DR, et al. KRAS promotes GLI2-dependent transcription during pancreatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Res Commun 2024;4:1677–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supp Fig 1

Supp Fig 2

Supp Fig 3

Supp Fig 4

Supp Fig 5

Supp Table 1

Supp Table 2

Supp Table 3

Supp Table 4

Data Availability Statement

This study used publicly available datasets from COSMIC (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), ICGC (https://dcc.icgc.org), TCGA via Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000086300-SNX10/cancer/pancreatic+cancer#PAAD_TCGA), and the GTEx dataset (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ ENSG00000086300-SNX10/tissue/pancreas). All data were accessed under the respective data usage policies. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials or from the corresponding author upon request.