Abstract

Pompe disease is a glycogen storage disorder caused by mutations in the acid α-glucosidase (GAA) gene, leading to reduced GAA activity and glycogen accumulation in heart and skeletal muscles. Enzyme replacement therapy with recombinant GAA, the standard of care for Pompe disease, is limited by poor skeletal muscle distribution and immune responses after repeated administrations. The expression of GAA in muscle with adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors has shown limitations, mainly the low targeting efficiency and immune responses to the transgene. To address these issues, we developed AAV capsids with improved skeletal muscle targeting and reduced off-targeting. These capsids combined with codon optimization, muscle-specific cis-regulatory elements, and a synthetic promoter demonstrated a strong skeletal muscle tropism, reduced liver targeting, and enhanced GAA transgene expression and reduced glycogen accumulation in a Gaa−/− mouse model. However, increased muscle-specific expression led to a robust anti-hGAA immune response. To circumvent this, the AAVMYO2 capsid was tested in immunodeficient Gaa−/−Cd4−/− mice and compared to AAV9 at different doses. The combination of AAVMYO2 with an optimized transgene expression cassette provided a dose-dependent advantage for glycogen reduction in skeletal muscles of Gaa−/−Cd4−/− mice. These findings support the potential of muscle-specific AAV gene therapy for Pompe disease at lower doses with greater specificity.

Keywords: Pompe disease, AAV gene therapy, muscle targeting, liver detargeting, immune response

Graphical abstract

Pompe disease is caused by reduced GAA activity, leading to muscle glycogen accumulation and associated muscle pathology. Ronzitti and colleagues developed muscle-tropic AAV capsids and optimized the transgene for enhanced muscle targeting and liver detargeting, resulting in improved protein expression and glycogen clearance in Pompe mice compared to AAV9.

Introduction

Pompe disease (PD), also known as glycogen storage disease type II (GSDII, OMIM#232300), is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that affects approximately 1 in 40,000 births. It is caused by mutations in the GAA gene encoding the enzyme acid α-glucosidase (GAA). This enzyme plays a crucial role in the breakdown of glycogen in lysosomes, converting it into glucose. In PD, GAA deficiency leads to the abnormal accumulation of glycogen in lysosomes throughout the body.1,2 The most affected tissues being the cardiac and skeletal muscles; the disease is characterized by cardiac insufficiency, muscle weakness, and respiratory failure.3 Neurological complications may also arise due to glycogen accumulation in neurons and white matter abnormalities, such as delayed motor skill, cognitive deficiencies, or mildly delayed learning.4,5,6

The standard of care for PD is enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with recombinant human GAA (rhGAA).1 ERT is used to treat both forms of PD: infantile-onset (IOPD) and late-onset (LOPD). LOPD patients are characterized by residual GAA activity (>1%) and experience slower disease progression with limited heart involvement. Meta-data analysis of multiple clinical studies has shown that ERT significantly improves walking distance, stabilizes respiratory function, and enhances muscle strength in LOPD patients.7 Immune reactions to rhGAA have minimal to no impact on the effectiveness of ERT in LOPD patients.8 In contrast, IOPD patients have no detectable GAA activity (<1%). Without treatment, IOPD patients typically do not survive beyond the first few years of life.9,10,11 ERT has significantly increased IOPD patient’s lifespan by improving ventilator-free survival and cardiac function.12,13,14,15,16 However, long-term evaluation has revealed that respiratory and muscle functions decline over time, even in IOPD patients positive to cross-reactive immune material (CRIM+) treated from an early age.9,17,18 This decline is particularly evident in CRIM˗ patients, likely due to immune responses to rhGAA that greatly reduce the efficacy of ERT.

In recent years, multiple gene therapy approaches have been developed for PD, and many of them progressed to preclinical and clinical phases.19,20,21,22 Most of those approaches use adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors to target either the liver or the muscle. Early studies focusing on liver-targeted expression of GAA have shown promising results in reducing pathological glycogen accumulation in muscles.23,24,25,26,27 Further studies in animal models of the disease and in healthy non-human primates (NHPs) supported safety and efficacy of the approach.26 The use of liver gene transfer with AAV vectors for the treatment of IOPD patients is, however, limited by the replication of hepatocytes during liver growth that may lead to transgene dilution and a loss of efficacy over time.28

On the other hand, muscle-specific approaches demonstrated efficacy in expressing the hGAA enzyme and in reducing glycogen accumulation in relevant muscles.29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 However, the main limitation of the muscle-targeted approach currently lies in the high doses of vectors required to efficiently target muscles in humans often exceeding 1 × 1014 vg/kg.37,38,39 This high dose poses a risk of acute liver toxicities and complement activation.40,41,42 Overall, while both liver and muscle-directed gene therapy approaches have shown promises in addressing PD, challenges remain related to long-term efficacy, high doses, and potential side effects. Ongoing research aims at the optimization of these approaches to provide safer and more effective treatment for PD patients.

In this study, we took advantage of two recently developed AAV capsids (AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3) with known enhanced muscle targeting,43,44,45 and we tested them in combination with the synthetic SpC5-12 promoter (C512), a known skeletal muscle-specific promoter.46 Comparison with AAV9 showed superior targeting of skeletal muscles with the two engineered AAV capsids, as well as robust liver detargeting. The use of a muscle-targeted transcriptional cis-regulatory elements (CREs)45,47 coupled to the SPc5-12 muscle-specific promoter (CRE-C512), together with a codon-optimized version of hGAA cDNA (hGAAco), further improved protein expression in cardiac and skeletal muscles. However, as expected from our recent works,36,48 the increased muscle specificity resulted also in an increased humoral immune response to hGAA. To assess vector efficacy while mitigating the effect of the potential immune response to the transgene, a dose-response study was conducted in Gaa−/− immunodeficient mice.26 In this mouse model of PD, the combination of the AAVMYO2 capsid with the optimized expression cassette (AAVMYO2-CRE-C512-hGAAco) was tested at three doses and compared to the original construct (AAV9-C512-hGAAwt) as well as to the AAVMYO3-CRE-hGAAco vector. Interestingly, the combination of the engineered capsid and promoter resulted in a dose advantage with higher GAA expression in skeletal muscle and complete clearance of glycogen content measured three months after AAV administration.

These findings underline the potential of improved muscle targeting by combining engineered AAV capsids with enhanced expression cassettes for the treatment of PD. While the reduction of the doses is beneficial as it helps to minimize the risk of liver-related toxicities, this work also supports the hypothesis that complete liver detargeting may result in the activation of an anti-transgene immune response that may be detrimental to the efficacy of the treatment itself.

Results

Engineered AAV capsids combined with optimized transgene expression cassettes result in superior glycogen clearance in skeletal muscle of adult Gaa−/− mice

The high doses required to achieve efficacy by muscle-directed AAV gene transfer in a murine model of PD49 led us to exploit novel myotropic AAV capsids obtained by grafting shuffled AAV vectors with integrin-targeting peptides.44 The two capsids, named AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3, were used to express wild-type or codon-optimized human GAA (hGAAwt or hGAAco, respectively) under the transcriptional control of the SPc5-12 muscle promoter or the same promoter genetically linked to muscle-targeted transcriptional CREs (CRE-C512)45,47 (Figure S1).

To validate the muscle-specific tropism of the capsid-promoter combinations, a three-month efficacy study was performed in adult Gaa−/− mice. In this first study, AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3 vectors were compared to AAV9 for the expression of hGAAwt under the control of the SPc5-12 promoter. In parallel, the AAVMYO3 vector was also used to express the hGAAco transgene under the control of the SPc5-12 promoter and to evaluate the strength of the CRE-C512 promoter in muscle tissues (Figure 1A). Three months after intravenous injection of the five AAV vectors at the dose of 1 × 1013 vg/kg, lower vector genome copy numbers (VGCNs) were observed in the heart of mice injected with AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3 capsids compared to AAV9 (Figure S2A). In line with the lower VGCN, the optimized vectors had tendentially lower GAA activity, similar transgene expression and glycogen clearance was observed in the heart when compared to the AAV9 reference vector (Figures 1B, 1C, and S2B; Table S1).

Figure 1.

Optimized AAV capsids and expression cassettes improve glycogen clearance in adult Gaa−/− mice

(A) Experimental design. Five-month-old Gaa−/− mice received a single injection of 5 different vectors: AAV9-C512-hGAAwt, AAVMYO2-C512-hGAAwt, AAVMYO3-C512-hGAAwt, AAVMYO3-C512-hGAAco, and AAVMYO3-CRE-hGAAwt, at 1 × 1013 vg/kg (n = 4 per group). PBS-injected Gaa+/+ (n = 4) and Gaa−/− (n = 5) mice were used as controls. Red drop symbols indicate the timing of blood collection in all cohorts. (B) GAA activity and (C) glycogen content measured in heart at sacrifice, three months after vector injection. (D) GAA activity and (E) glycogen content in skeletal muscles (diaphragm, quadriceps, triceps, and gastrocnemius) at sacrifice. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis: (B–E): one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test; ∗, #, and +p < 0.05; ∗∗, ##, and ++p < 0.01’ ∗∗∗, ###, and +++p < 0.001; and ∗∗∗∗, ####, and ++++p < 0.0001, vs. PBS-treated Gaa+/+ for #, vs. PBS-treated Gaa−/− for ∗ and vs. AAV9-treated Gaa−/− for +.

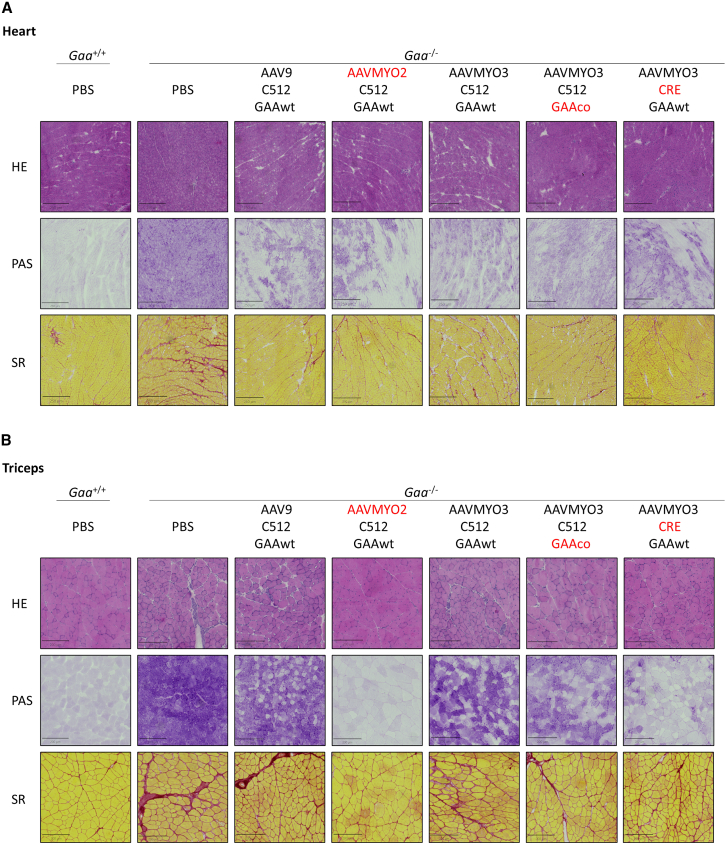

Skeletal muscle tissue targeting as measured by VGCNs was increased up to 5-fold in mice injected with the two engineered capsids compared to AAV9 (Figure S2C; Table S1). Gaa−/− mice treated with the AAVMYO3 capsid showed increased VGCN in diaphragm while AAVMYO2 was enriched in triceps (Figure S2C; Table S1). A robust increase in GAA activity and expression was observed in diaphragm, quadriceps, triceps, and gastrocnemius when mice were treated with AAVMYO2 compared to the AAV9 reference vector with the same transgene expression cassette (Figures 1D and S2D–S2G). Interestingly, an increase in GAA activity was observed in the diaphragm, quadriceps, triceps, and gastrocnemius when the AAVMYO3 capsid was combined with either a codon optimized transgene (GAAco) or the CRE-C512 promoter (Figure 1D). In accordance with the increased GAA activity, improved glycogen clearance was observed in muscles of mice treated with the AAVMYO2-C512 compared to AAV9. The combination of AAVMYO3 with different transgene codon optimization or the CRE-C512 promoter improved glycogen clearance in triceps compared to Gaa−/− mice treated with the AAVMYO3 capsid bearing the non-optimized transgene expression cassette (AAVMYO3-C512-hGAA, Figure 1E). Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining confirmed the clearance of glycogen in heart achieved by AAV treatment (Figure 2A) and the improved clearance in triceps by treatment with AAVMYO2-C512 and AAVMYO3-CRE-C512 vectors (Figure 2B). Sirius red (SR) staining showed reduced fibrosis in the heart of AAV-treated mice (Figure 2A) and a better reduction of fibrosis in triceps of Gaa−/− mice treated with the AAVMYO2-C512 vector compared to AAV9-treated mice (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Optimized AAV capsids and expression cassettes decrease glycogen accumulation and fibrosis in adult Gaa−/− mice

Five-month-old Gaa−/− mice were treated as described in Figure 1. (A and B) Representative picture of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), and Sirius red (SR) staining in heart (A) and triceps (B) three months after AAV vector injection.

Cognitive function impairment was recently described in patients with PD with an impact on the long-term quality of life in IOPD patients treated with ERT.4,5,6 We thus evaluated the expression profile of the novel engineered capsids in the central nervous system (CNS). At the dose of 1 × 1013 vg/kg, both AAV9, a known capsid for CNS targeting, and the engineered AAV vectors had very low VGCN and a GAA activity similar to PBS-treated Gaa−/− mice (Table S1; Figures S3A and S3B). Interestingly, while no GAA expression was observed in the brain by western blot, GAA expression in the spinal cord was observed only in mice receiving the AAVMYO2-C512 or AAVMYO3-GAAco vector (Figures S3C and S3D). In line with GAA expression, while no reduction in glycogen content was observed in the brain (Figure S3E), Gaa−/− mice treated with AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3 showed a partial reduction of glycogen content in the spinal cord when compared to AAV9-treated mice (Figure S3F).

AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3 capsids are known to detarget the liver.44 We confirmed the extensive liver detargeting by measuring VGCN in liver compared to AAV9. A more than 300-fold decrease in genome copies was measured in the liver of Gaa−/− mice treated with the two engineered capsids compared to AAV9 (Figure 3A). The use of the muscle-specific SPc5-12 promoter in the expression cassette resulted in undetectable GAA activity in the liver of AAV-treated mice (Figure 3B). A very low GAA expression was detected by western blot in mice treated with AAV9 possibly due to the promoter leakage in this tissue (Figure 3C). No GAA transgene product was detected in the plasma of AAV-treated mice (Figure S4A).

Figure 3.

Muscle-specific targeting with engineered AAV vectors and expression cassette increases immune response against-hGAA

Five-month-old Gaa−/− mice were treated as described in Figure 1. (A) VGCN, (B) GAA activity, and (C) western blot analysis of GAA expression in liver at sacrifice. (D) Circulating anti-hGAA IgG measured in plasma at sacrifice. (E) Mean circulating anti-hGAA IgG measured overtime. (A–D) Data are shown as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test; ∗and +p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗∗, ####, and ++++p < 0.0001, vs. PBS-treated Gaa+/+ for #, vs. PBS-treated Gaa−/− for ∗ and vs. AAV9-treated Gaa−/− for +.

The central role of the hepatic expression of a transgene in establishing peripheral tolerance to antigens expressed in muscle was demonstrated multiple times in PD.27,48,50,51 The use of a muscle-specific promoter led to the development of high-titer anti-hGAA antibodies in all the AAV-treated mice possibly due to the increased muscle expression and the decreased liver targeting (Figures 3D and S4B). Importantly, while simultaneous liver-muscle targeting is known to induce an only transient humoral response to hGAA,36 specific muscle targeting with extensive liver detargeting resulted in higher IgG levels continuously increasing over time (Figures 3E and S4B). Interestingly, mice treated with AAVMYO2-C512 and AAV9-C512 vectors had very similar levels of anti-GAA antibodies.

These data suggest that both AAVMYO2-C512-hGAAwt and AAVMYO3-C512-hGAAwt had better efficacy than AAV9-C512-hGAAwt in skeletal muscle, with AAVMYO2 capsid showing slightly better targeting of this tissue than AAV-MYO3. Interestingly, Gaa−/− mice treated with the AAVMYO2 capsid showed levels of anti-hGAA antibodies comparable to those receiving AAV9 despite the higher level of expression in muscle and the extensive liver detargeting achieved in mice treated with the engineered capsid (Figures 3D, 3E, and S4B).

Muscle-specific targeting with engineered AAV vectors achieves efficacy at lower vector doses compared to AAV9 in immunodeficient Gaa−/−Cd4−/− mice

Based on the previous efficacy results and on the anti-transgene antibody response formation, dose response experiment was performed in immunodeficient Gaa−/− Cd4−/− double knockout mice26 to evaluate the expression levels achieved by the engineered capsids and promoter avoiding any confounding effect of the immune response. The AAVMYO2 vector expressing the human codon optimized GAA under the control of the CRE-C512 promoter (AAVMYO2-CRE-hGAAco) was injected at the dose of 3, 8, or 16 × 1012 vg/kg in Gaa−/− Cd4−/− mice. AAV9-C512-hGAAwt and AAVMYO3-CRE-hGAAco vectors were injected at 8 × 1012 vg/kg and used as controls (Figure 4A).

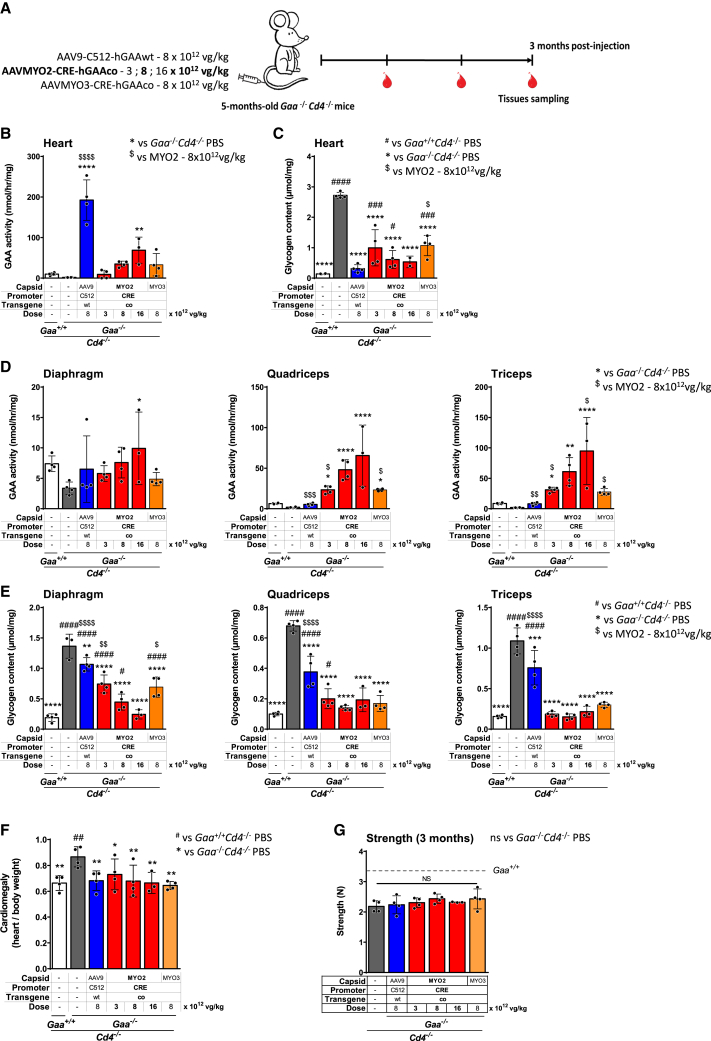

Figure 4.

Combination of AAVMYO2 and muscle-targeted CRE lower the dose of vector needed to reduce glycogen accumulation in skeletal muscle as compared to AAV9 in immunodeficient Gaa−/−Cd4−/− mice

(A) Experimental design. Five-month-old Gaa−/−Cd4−/− mice received a single injection of three different vectors: AAV9-C512-hGAAwt or AAVMYO3-CRE-hGAAco, at the dose of 8 × 1012 vg/kg or AAVMYO2-CRE-hGAAco at three different doses: 3 × 1012, 8 × 1012, and 1.6 × 1013 vg/kg (n = 4 per group). PBS-injected Gaa+/+Cd4−/− (n = 4) and Gaa−/−Cd4−/− (n = 4) mice were used as controls. Red symbols indicate the timing of blood collection in all cohorts. (B) GAA activity and (C) glycogen content measured in heart at sacrifice, three months after vector injection. (D) GAA activity and (E) glycogen content in skeletal muscles (diaphragm, quadriceps, and triceps) at sacrifice. (F) Cardiomegaly and (G) grip strength measure three months after AAV injection. Data shown as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis: (B–G): One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test; ∗, #, and $p < 0.05; ∗∗, ##, and $$p < 0.01; ∗∗∗, ###, and $$$p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗, ####, and $$$$p < 0.0001, vs. PBS-treated Gaa+/+ for #, vs. PBS-treated Gaa−/− for ∗ and vs. AAVMYO2-CRE-GAAco-treated Gaa−/− at 8 × 1012 vg/kg for $.

Measurement of GAA activity in the heart showed supraphysiological activity in mice treated with the AAV9-C512-hGAAwt, a dose-dependent increase in GAA activity after treatment with AAVMYO2-CRE-hGAAco, and a more variable GAA activity in mice treated with the AAVMYO3-CRE-hGAAco vector (Figure 4B). Consistently, the highest glycogen reduction in the heart was observed in mice receiving the AAV9 vector while animals treated with the AAVMYO2-CRE-hGAAco vector showed a dose-dependent decrease in glycogen accumulation superior to that achieved by treatment with the AAVMYO3-CRE-hGAAco vector at the same dose (Figure 4C).

In skeletal muscle, a dose-dependent increase of GAA activity was observed after treatment with the AAVMYO2-CRE-hGAAco vector. At the dose of 8 × 1012 vg/kg, GAA activity was higher compared to Gaa−/− Cd4−/− mice treated with AAVMYO3-CRE-hGAAco and AAV9 bearing the non-optimized cassette thus supporting the choice of the candidate vector (Figure 4D). Importantly, in line with the GAA activity data, glycogen levels measured in the same muscle groups were generally lower in mice treated with the AAVMYO2-CRE-GAAco vector in comparison to AAV9-treated mice (Figure 4E). These data suggest that the combination of AAVMYO2 capsid with the improved transgene expression cassette resulted in enhanced GAA activity and glycogen clearance in quadriceps and triceps and complete correction of glycogen accumulation at the highest dose in all muscle tissues including heart.

Functional assessment was then conducted to investigate the potential correction of cardiomegaly and muscle strength in Gaa−/− Cd4−/− mice after treatment with the engineered AAVs. As expected, cardiomegaly, measured as the ratio of the heart and body weights, was present in PBS-treated Gaa−/− Cd4−/− mice. In line with the results obtained on glycogen accumulation, the AAV-treated mice exhibited lower heart/body weight ratios, similar to those measured in PBS-treated Gaa+/+ Cd4−/− mice (Figure 4F). Measurement of grip strength revealed a tendency to a slight increase in Gaa−/− Cd4−/− mice treated with the AAVMYO2-CRE-hGAAco vector although it did not reach significance (p value = 0.11) (Figure 4G). No differences in muscle strength were observed in AAV-treated Gaa−/− Cd4−/− mice as compared to PBS-treated Gaa+/+ Cd4−/− and Gaa−/− Cd4−/− mice, possibly due to the short duration of the protocol (Figure 4G).

As observed in the first study, liver detargeting was confirmed for the engineered capsids by the lower VGCN measured in the liver compared to AAV9 (Figure S5A). The use of muscle-specific promoters resulted in the absence of GAA activity measured in the liver of AAV-treated mice (Figure S5B).

The lungs, brain, and spinal cord were also analyzed, and the low AAV copies observed in these tissues (Table S2) led to no detectable GAA activity (Table S3) that invariably did not affect glycogen accumulation (Table S4).

Overall, these data demonstrate that the AAVMYO2-CRE-hGAAco capsid-promoter combination enhanced muscle gene transfer efficacy, with a significant increase of GAA activity and a reduction of glycogen content in skeletal muscles. Importantly, Gaa−/− Cd4−/− mice treated with medium and high doses of AAVMYO2-CRE-hGAAco showed correction of glycogen accumulation in skeletal muscle without overloading the heart and with a robust liver detargeting.

Discussion

PD is a rare inherited metabolic and muscle-wasting disorder with an urgent medical need.19,21,22 Children affected by the most severe form of this disease suffer from progressive skeletal muscle weakness and, without medical intervention, can die within their first year of life from cardiorespiratory failure. Current treatment for PD involves recurrent infusions with rhGAA or ERT. The introduction of this treatment represented a major advance in the treatment of PD, being lifesaving in infantile patients, although with only a moderate effect in the late-onset forms of the disease.7,13,52,53 Gene therapy, by potentially overcoming the current limitations of ERT, represents a promising alternative to treat skeletal muscles and CNS involvement.

Over the last years, muscle-directed AAV-based gene therapies for PD have shown great promise in preclinical evaluation, notably due to their capability to transduce skeletal muscle, diaphragm, heart, and CNS.33,54 AAV9 is also being used in a phase 1/2 clinical trial for heart and muscle targeting in patients with LOPD (NCT06391736).

However, one limitation of AAV9 for muscle targeting via the systemic route is that it requires doses of vector exceeding 1 × 1014 vg/kg, requiring considerable production efforts, when addressing an adult patient population. The use of such high vector doses may also represent a considerable risk, due to off-target toxicities and immune responses including complement activation observed at these doses.40,41 As an example, in the ASPIRO clinical trial (NCT03199469) for patients suffering from X-linked myotubular myopathy, 4 out of 23 subjects who received the AAV treatment showed signs of liver dysfunction, evolving into progressive liver failure and death possibly related to off-target tissue vector overload in the context of a pre-existing liver disease.55

To address these two limitations, efforts have been focused on the engineering of AAV capsids to improve skeletal muscle targeting while reducing off-target tissues overload. Combinations of rational design and directed evolution approaches have been employed to enhance muscle targeting of AAV vectors.36,43,44,45,56,57 To further increase muscle gene transfer efficacy and specificity, researchers are pursuing the development of novel promoters driving muscle-specific transgene expression at lower and safer vector doses.45,47,48

The results reported here underscore the potential of the combination of computationally designed promoters with evolved AAV capsids to reduce the minimum effective dose of AAV gene therapy and achieve a safer gene transfer in the context of myopathies, such as PD. In particular, the combination of the potent muscle-specific CRE/SPcC5-12 promoter45,47 with the use of innovative muscle-tropic AAV serotypes43,44 derived from peptide display and directed molecular evolution technologies resulted in a substantial dose advantage as compared to a state-of-the-art AAV vector/promoter combination. A dose 10-fold lower than the one currently used in several clinical trials with AAV9 (1 × 1014 vg/kg) seems to achieve therapeutic efficacy in PD mice. However, in the absence of data about the translation of these results in humans or in other large animal models, a clinically relevant starting dose may not be easily defined. In addition, both myotropic AAV vectors showed lower cardiac tropism than AAV9, which could also be beneficial in avoiding excessive protein expression in the cardiac tissue, one potential explanation for the cardiotoxicity was recently reported in clinical trials of AAV gene therapy.40,55 We also confirmed that the novel AAV vector/promoter combinations were markedly detargeted from the liver. The reduced risk of liver overload was the result of the combination of the specific design of these AAV variants and the use of muscle-specific promoters. An important consequence of the extensive liver detargeting of the engineered vectors is the formation of a robust immune response to the hGAA transgene. hGAA is immunogenic as shown in previous studies in mouse models of PD using muscle-specific promoters,48,49,58 but also in a phase 1/2 clinical trial using the ubiquitous cytomegalovirus promoter.59 An effective strategy to achieve immune tolerance to hGAA is to express the transgene in hepatocytes. Successful prevention of antibody production was achieved when employing a liver-specific promoter to express hGAA.24,48 However, hepatic expression of hGAA with AAV vectors can hardly be applied in IOPD patients due to the potential vector genome dilution in the developing liver. Although strategies for AAV vector readministration are being developed,60,61,62 muscle-directed gene transfer may represent a valid alternative to achieve stable transduction in IOPD patients. Muscle gene transfer is likely to provide better long-term stability compared to liver gene transfer in the pediatric population. However, the current work, by showing that highly specific muscle targeting led to anti-transgene immunity, reinforces the idea that novel approaches aimed at the improvement of muscle gene transfer may benefit from residual liver expression as already proposed by our team.36 Alternatively, transient immunomodulation may help to mitigate transgene immunogenicity.63

The control of the anti-hGAA immune response is a concern for AAV-mediated gene therapy for PD, as the formation of neutralizing antibodies can be associated with poor prognosis, particularly in IOPD patients.1,11,13 Combination therapy, aimed at achieving immune tolerance in this patients’ population after ERT treatment, is being developed17,18 and may offer an opportunity to improve both the safety and efficacy of AAV gene therapy for PD. One specific limitation of our work is that we have not addressed the characterization of the immune response to the transgene in the context of muscle-specific gene transfer. However, such evaluations are complicated by the absence of tools to ascertain the mechanisms underlying the formation of immune responses in the muscle. In addition to this, immune responses are dependent on the disease background and the mouse models available recapitulate mainly the late-onset PD, where the impact of immune responses on treatment efficacy is limited when compared to the infantile form of the disease.8,19,21

While the use of AAVMYO capsids led to slightly improved transgene expression and glycogen reduction in spinal cord, complete CNS correction was not achieved in this study. Based on previous results, this partial correction is likely not sufficient to have any impact on the respiratory function.24 CNS targeting optimization may be achieved through alternative injection routes, such as intrathecal administration or a combination of intravenous and intrathecal routes.64,65 Additionally, treatment of younger mice with a more permeable blood-brain barrier has demonstrated enhanced efficacy.66,67

A formal dose finding study and further evaluations in NHP models and/or in human cells may be crucial to support the dose advantage shown in immunodeficient mice. Further evaluations are thus needed to ensure successful translation of this muscle gene transfer approach, supporting the biological potency and providing a comprehensive safety assessment of these new muscle-tropic capsid-promoter combinations. Altogether, the results obtained in this study confirm the potential of myotropic AAV vectors to improve the efficacy and safety of muscle-directed gene therapy for PD. Optimization of liver targeting in combination with efficient immunosuppression methods may enable safe and efficient gene transfer in diseases, such as PD, where anti-transgene immunity represents a clear limitation.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

The GAA plasmid was composed of a SPcC5-12 muscle promoter46 combined, or not, with muscle-targeted transcriptional CREs45,47 and a human GAA wild-type (hGAAwt) or codon-optimized (hGAAco) version of the native GAA described.24 The AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3 capsids were engineered via a semi-rational combination of DNA shuffling and peptide display to maximize gene delivery in skeletal and cardiac muscle as well as diaphragm.44

AAV vector production

AAV vectors were produced by triple transfection in HEK293 cells and purified using a double CsCl gradient-based purification protocol that renders vector preps of high purity with negligible amounts of empty capsids.68 Titers of AAV vectors were determined by PicoGreen (Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit, Invitrogen), using phage lambda DNA to generate the standard curve.68

Mouse model

Comparative efficacy studies were performed in male Gaa knockout mice (Gaa −/− and Gaa−/−Cd4−/−) purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (B6; 129-Gaatm1Rabn/J, stock no. 004154, 6neo) and originally generated by Raben et al.69 and Cd4−/− mice (B6.129S2-Cd4tm1Mak/J stock no. 002663) generated as described in the study by Costa-Verdera et al.26. Littermate male mice were used, either affected (Gaa−/− or Gaa−/− Cd4−/−) or healthy (Gaa+/+ or Gaa+/+ Cd4−/−). We have reported the phenotype of males Gaa−/− versus Gaa+/+ from our colonies in previous work.24

In-vivo studies in mice

In-vivo studies were performed in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations for animal testing and research. Notably, they were performed according to the French and European legislation on animal care and experimentation (2010/63/EU) and approved by Genethon’s ethical committee. In all mouse studies, animals were randomly assigned to treatment groups. To minimize potential bias during functional assessments in mice, operators were blinded to the study design. Operators in charge of sample analysis were blinded to study design.

Experiments in adult mice

Treatments with AAV vectors were performed in male Gaa−/− mice of five months of age, which received either intravenous injection of vehicle (PBS), the AAV9, or the different AAV vector candidates. Four animals per group were injected via tail vein infusion with 3 × 1012, 8 × 1012, 1 × 1013, or 1.6 × 1013 vg/kg of vector (in a volume of 200 μL). Age-matched and sex-matched Gaa+/+ littermates were used as healthy controls in the studies. In the Gaa−/− study, some PBS or AAV-injected mice died before the end of the protocol.

Grip test

Muscle strength was evaluated using a grip strength meter (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH).19 Briefly, mice were lifted by the tail to the level of the grip strength meter grid and moved horizontally until they could grasp it. The mice were then gently pulled away from the grid until they released their grip, and the force was recorded by the device. Each mouse underwent three independent measurements, and the mean value, expressed in Newtons, was reported.

Anti-hGAA IgG measurement

Blood samples were collected by retro-orbital sampling into heparinized capillary tubes and mixed with 3.8% w/v sodium citrate, followed by plasma isolation. The concentration of anti-hGAA IgG antibodies in mouse plasma was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).24

GAA activity and western blot analyses

Snap-frozen tissues were homogenized in UltraPure DNase/RNase-free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with FastPrep lysis tubes (MP Biomedicals, OH, USA), followed by centrifugation 20 min at 10,000×g to collect the supernatant. Protein content in lysates was quantified by BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). GAA activity measurement was performed as already described.24 SDS-page electrophoresis was performed with NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA). After transfer, the membrane was blocked with Odyssey buffer (Li-Cor Biosciences) and incubated with an anti-hGAA antibody (rabbit monoclonal, clone EPR4716(2), Abcam) and anti-Vinculin (mouse monoclonal, clone V9131, Sigma-Aldrich). The membrane was then washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (LI-COR Biosciences) and visualized with the Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). Densitometry analysis was conducted using Image Studio Lite (LI-COR Biosciences) version 4.0. The quantification of the hGAA bands in mouse tissues was normalized using housekeeping vinculin protein bands. Protein level was reported as arbitrary units (AU).

Glycogen content measurement

Tissue homogenates samples were prepared as described for the analysis of GAA activity. Glycogen assay was performed as already described.24

Vector genome copy number

Vector genome copies in mice were determined by qPCR on total tissue DNA. Total DNA was extracted from tissues homogenates using the NucleoMag Pathogen (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) extraction method according to manufacturer’s instructions. The number of vector copies per diploid genome was determined using primers to amplify the 5′-ITR sequence (forward: 5′-GGAACCCCTAGTGATGGAGTT-3′; reverse: 5′-CGGCCTCAGTGAGCGA-3′; probe: 5′-CACTCCCTCTCTGCGCGCTCG-3′). The number of vector copies was normalized by the copies of the titin gene, which was used as an internal control for each sample (forward: 5′-AAAACGAGCAGTGACGTGAGC-3′; reverse: 5′-TTCAGTCATGCTGCTAGCGC-3′; probe, 5′-TGCACGGAAGCGTCTCGTCTCAGT-3′). Data were expressed as vector genome copies per diploid genome.

Histology and staining

Immediately after euthanasia, muscles were snap-frozen in isopentane (−160°C) previously chilled in liquid nitrogen. Serial 8 mm cross-sections were cut in a Leica CM3050 S cryostat (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). To minimize sampling error, two or three sections of each specimen were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, PAS, and SR, according to standard procedures. Muscle images were acquired using an Axioscan slide scanner (ZEISS, Munich, Germany), using a plan-apochromat 10 × magnitude 0.45 numerical aperture objective.

Statistical analysis

All data shown in the present manuscript are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analyses. p value <0.05 was considered significant. The number of sampled units (n), upon which we reported statistics is the single animal. Parametric tests were used for data having a normal distribution with α = 0.05. One-way ANOVA with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test was used for comparisons of one variable between more than two groups. All statistical tests were performed two-sided. The statistical analysis performed for each dataset is indicated in the figure legends.

Data availability

All data presented in the manuscript are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Genethon and the French Muscular Dystrophy Association. It was also supported by the European Union’s research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 667751 (to M.K.C., T.V., D.G., F.M., and F.B.) by SAF2017-86266R funded by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Plan Nacional I + D + I (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033), Spain, and by ERDF/“ERDF A way of making Europe” by the European Union (to F.B.). T.V. and M.K.C. received grant support from Methusalem, the Vrije Universiteit Brussel Industrieel Onderzoeksfonds (IOF) Groups of Expertise in Advanced Research (GEAR), Strategic Research Project (SRP), F.W.O. (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen), and Koning Boudewijnstichting (Fonds Walter Pyleman, Cremers-Opdebeeck, Richard Depasse). The salary of Y.K.B. was covered by the “Plan France Relance” agreement no ANR-21-PRRRD-0002-01. We thank the Genethon Animal facilities and Histology Core for technical help. We also thank the Imaging and Cytometry Core Facility of Genethon.

Author contributions

P.S., F.C., and G.R. performed or directed experimental activities and contributed significantly to experimental design. V.J., X.L., and F.B. produced the vectors used in the present work. M.K.C. and T.V. developed and designed the muscle-targeted transcriptional elements (CREs). Q.H.P. contributed to the CRE testing. D.G. and J.E.A. developed and designed the AAVMYO2 and AAVMYO3 vectors. P.S., Y.K.B., and F.C. performed experiments and data analysis. N.D. managed animal and histology platforms. P.S. and G.R. wrote the manuscript. F.M. provided insights into the AAV vector development and disease pathophysiology. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

F.C., F.M., and G.R. are inventors of patents applications concerning the treatment of PD by AAV. D.G. is a cofounder of AaviGen GmbH. D.G. and J.E.A. are inventors of patent applications related to the myotropic AAV capsids; T.V. and M.C. are inventors of patent applications related to the transcriptional CREs. The AAVMYO helper plasmids including a full map can be obtained by academic institutions via a standard non-commercial MTA from Heidelberg University Hospital.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2025.101464.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Kishnani P.S., Hwu W.L., Mandel H., Nicolino M., Yong F., Corzo D., Infantile-Onset Pompe Disease Natural History Study Group Pompe Disease Natural History Study. J. Pediatr. 2006;148:671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohler L., Puertollano R., Raben N. Pompe Disease: From Basic Science to Therapy. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:928–942. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0655-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Ploeg A.T., Reuser A.J. Pompe's disease. Lancet. 2008;372:1342–1353. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61555-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne B.J., Fuller D.D., Smith B.K., Clement N., Coleman K., Cleaver B., Vaught L., Falk D.J., McCall A., Corti M. Pompe disease gene therapy: neural manifestations require consideration of CNS directed therapy. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019;7:290. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.05.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebbink B.J., Poelman E., Plug I., Lequin M.H., van Doorn P.A., Aarsen F.K., van der Ploeg A.T., van den Hout J.M.P. Cognitive decline in classic infantile Pompe disease: An underacknowledged challenge. Neurology. 2016;86:1260–1261. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korlimarla A., Lim J.A., Kishnani P.S., Sun B. An emerging phenotype of central nervous system involvement in Pompe disease: from bench to bedside and beyond. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019;7:289. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.04.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarah B., Giovanna B., Emanuela K., Nadi N., Josè V., Alberto P. Clinical efficacy of the enzyme replacement therapy in patients with late-onset Pompe disease: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2022;269:733–741. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10526-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masat E., Laforêt P., De Antonio M., Corre G., Perniconi B., Taouagh N., Mariampillai K., Amelin D., Mauhin W., Hogrel J.Y., et al. Long-term exposure to Myozyme results in a decrease of anti-drug antibodies in late-onset Pompe disease patients. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep36182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amalfitano A., Bengur A.R., Morse R.P., Majure J.M., Case L.E., Veerling D.L., Mackey J., Kishnani P., Smith W., McVie-Wylie A., et al. Recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase enzyme therapy for infantile glycogen storage disease type II: results of a phase I/II clinical trial. Genet. Med. 2001;3:132–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishnani P.S., Corzo D., Nicolino M., Byrne B., Mandel H., Hwu W.L., Leslie N., Levine J., Spencer C., McDonald M., et al. Recombinant human acid [alpha]-glucosidase: major clinical benefits in infantile-onset Pompe disease. Neurology. 2007;68:99–109. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251268.41188.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolino M., Byrne B., Wraith J.E., Leslie N., Mandel H., Freyer D.R., Arnold G.L., Pivnick E.K., Ottinger C.J., Robinson P.H., et al. Clinical outcomes after long-term treatment with alglucosidase alfa in infants and children with advanced Pompe disease. Genet. Med. 2009;11:210–219. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31819d0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chien Y.H., Lee N.C., Thurberg B.L., Chiang S.C., Zhang X.K., Keutzer J., Huang A.C., Wu M.H., Huang P.H., Tsai F.J., et al. Pompe disease in infants: improving the prognosis by newborn screening and early treatment. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1116–e1125. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tardieu M., Cudejko C., Cano A., Hoebeke C., Bernoux D., Goetz V., Pichard S., Brassier A., Schiff M., Feillet F., et al. Long-term follow-up of 64 children with classical infantile-onset Pompe disease since 2004: A French real-life observational study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023;30:2828–2837. doi: 10.1111/ene.15894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prater S.N., Banugaria S.G., DeArmey S.M., Botha E.G., Stege E.M., Case L.E., Jones H.N., Phornphutkul C., Wang R.Y., Young S.P., Kishnani P.S. The emerging phenotype of long-term survivors with infantile Pompe disease. Genet. Med. 2012;14:800–810. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prater S.N., Patel T.T., Buckley A.F., Mandel H., Vlodavski E., Banugaria S.G., Feeney E.J., Raben N., Kishnani P.S. Skeletal muscle pathology of infantile Pompe disease during long-term enzyme replacement therapy. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013;8:90. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chien Y.H., Lee N.C., Chen C.A., Tsai F.J., Tsai W.H., Shieh J.Y., Huang H.J., Hsu W.C., Tsai T.H., Hwu W.L. Long-term prognosis of patients with infantile-onset Pompe disease diagnosed by newborn screening and treated since birth. J. Pediatr. 2015;166:985–991.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curelaru S., Desai A.K., Fink D., Zehavi Y., Kishnani P.S., Spiegel R. A favorable outcome in an infantile-onset Pompe patient with cross reactive immunological material (CRIM) negative disease with high dose enzyme replacement therapy and adjusted immunomodulation. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2022;32 doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2022.100893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kishnani P.S., Goldenberg P.C., DeArmey S.L., Heller J., Benjamin D., Young S., Bali D., Smith S.A., Li J.S., Mandel H., et al. Cross-reactive immunologic material status affects treatment outcomes in Pompe disease infants. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;99:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ronzitti G., Collaud F., Laforet P., Mingozzi F. Progress and challenges of gene therapy for Pompe disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019;7:287. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.04.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unnisa Z., Yoon J.K., Schindler J.W., Mason C., van Til N.P. Gene Therapy Developments for Pompe Disease. Biomedicines. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10020302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colella P., Mingozzi F. Gene Therapy for Pompe Disease: The Time is now. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019;30:1245–1262. doi: 10.1089/hum.2019.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colella P. Advances in Pompe Disease Treatment: From Enzyme Replacement to Gene Therapy. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2024;28:703–719. doi: 10.1007/s40291-024-00733-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franco L.M., Sun B., Yang X., Bird A., Zhang H., Schneider A., Brown T., Young S.P., Clay T.M., Amalfitano A., et al. Evasion of immune responses to introduced human acid alpha-glucosidase by liver-restricted expression in glycogen storage disease type II. Mol. Ther. 2005;12:876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puzzo F., Colella P., Biferi M.G., Bali D., Paulk N.K., Vidal P., Collaud F., Simon-Sola M., Charles S., Hardet R., et al. Rescue of Pompe disease in mice by AAV-mediated liver delivery of secretable acid alpha-glucosidase. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam6375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cagin U., Puzzo F., Gomez M.J., Moya-Nilges M., Sellier P., Abad C., Van Wittenberghe L., Daniele N., Guerchet N., Gjata B., et al. Rescue of Advanced Pompe Disease in Mice with Hepatic Expression of Secretable Acid alpha-Glucosidase. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:2056–2072. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa-Verdera H., Collaud F., Riling C.R., Sellier P., Nordin J.M.L., Preston G.M., Cagin U., Fabregue J., Barral S., Moya-Nilges M., et al. Hepatic expression of GAA results in enhanced enzyme bioavailability in mice and non-human primates. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6393. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26744-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han S.O., Ronzitti G., Arnson B., Leborgne C., Li S., Mingozzi F., Koeberl D. Low-Dose Liver-Targeted Gene Therapy for Pompe Disease Enhances Therapeutic Efficacy of ERT via Immune Tolerance Induction. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2017;4:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bortolussi G., Baj G., Vodret S., Viviani G., Bittolo T., Muro A.F. Age-dependent pattern of cerebellar susceptibility to bilirubin neurotoxicity in vivo in mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 2014;7:1057–1068. doi: 10.1242/dmm.016535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraites T.J., Jr., Schleissing M.R., Shanely R.A., Walter G.A., Cloutier D.A., Zolotukhin I., Pauly D.F., Raben N., Plotz P.H., Powers S.K., et al. Correction of the enzymatic and functional deficits in a model of Pompe disease using adeno-associated virus vectors. Mol. Ther. 2002;5:571–578. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rucker M., Fraites T.J., Jr., Porvasnik S.L., Lewis M.A., Zolotukhin I., Cloutier D.A., Byrne B.J. Rescue of enzyme deficiency in embryonic diaphragm in a mouse model of metabolic myopathy: Pompe disease. Development. 2004;131:3007–3019. doi: 10.1242/dev.01169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cresawn K.O., Fraites T.J., Wasserfall C., Atkinson M., Lewis M., Porvasnik S., Liu C., Mah C., Byrne B.J. Impact of humoral immune response on distribution and efficacy of recombinant adeno-associated virus-derived acid alpha-glucosidase in a model of glycogen storage disease type II. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005;16:68–80. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mah C., Cresawn K.O., Fraites T.J., Jr., Pacak C.A., Lewis M.A., Zolotukhin I., Byrne B.J. Sustained correction of glycogen storage disease type II using adeno-associated virus serotype 1 vectors. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1405–1409. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falk D.J., Mah C.S., Soustek M.S., Lee K.Z., Elmallah M.K., Cloutier D.A., Fuller D.D., Byrne B.J. Intrapleural administration of AAV9 improves neural and cardiorespiratory function in Pompe disease. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:1661–1667. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falk D.J., Soustek M.S., Todd A.G., Mah C.S., Cloutier D.A., Kelley J.S., Clement N., Fuller D.D., Byrne B.J. Comparative impact of AAV and enzyme replacement therapy on respiratory and cardiac function in adult Pompe mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2015;2 doi: 10.1038/mtm.2015.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Todd A.G., McElroy J.A., Grange R.W., Fuller D.D., Walter G.A., Byrne B.J., Falk D.J. Correcting Neuromuscular Deficits With Gene Therapy in Pompe Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2015;78:222–234. doi: 10.1002/ana.24433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sellier P., Vidal P., Bertin B., Gicquel E., Bertil-Froidevaux E., Georger C., van Wittenberghe L., Miranda A., Daniele N., Richard I., et al. Muscle-specific, liver-detargeted adeno-associated virus gene therapy rescues Pompe phenotype in adult and neonate Gaa(-/-) mice. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2024;47:119–134. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Childers M.K., Joubert R., Poulard K., Moal C., Grange R.W., Doering J.A., Lawlor M.W., Rider B.E., Jamet T., Danièle N., et al. Gene therapy prolongs survival and restores function in murine and canine models of myotubular myopathy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:220ra10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Guiner C., Servais L., Montus M., Larcher T., Fraysse B., Moullec S., Allais M., François V., Dutilleul M., Malerba A., et al. Long-term microdystrophin gene therapy is effective in a canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms16105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mack D.L., Poulard K., Goddard M.A., Latournerie V., Snyder J.M., Grange R.W., Elverman M.R., Denard J., Veron P., Buscara L., et al. Systemic AAV8-Mediated Gene Therapy Drives Whole-Body Correction of Myotubular Myopathy in Dogs. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:839–854. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ertl H.C.J. Immunogenicity and toxicity of AAV gene therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.975803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West C., Federspiel J.D., Rogers K., Khatri A., Rao-Dayton S., Ocana M.F., Lim S., D'Antona A.M., Casinghino S., Somanathan S. Complement Activation by Adeno-Associated Virus-Neutralizing Antibody Complexes. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023;34:554–566. doi: 10.1089/hum.2023.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lek A., Wong B., Keeler A., Blackwood M., Ma K., Huang S., Sylvia K., Batista A.R., Artinian R., Kokoski D., et al. Death after High-Dose rAAV9 Gene Therapy in a Patient with Duchenne's Muscular Dystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;389:1203–1210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2307798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinmann J., Weis S., Sippel J., Tulalamba W., Remes A., El Andari J., Herrmann A.K., Pham Q.H., Borowski C., Hille S., et al. Identification of a myotropic AAV by massively parallel in vivo evaluation of barcoded capsid variants. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5432. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19230-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El Andari J., Renaud-Gabardos E., Tulalamba W., Weinmann J., Mangin L., Pham Q.H., Hille S., Bennett A., Attebi E., Bourges E., et al. Semirational bioengineering of AAV vectors with increased potency and specificity for systemic gene therapy of muscle disorders. Sci. Adv. 2022;8:eabn4704. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abn4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munoz S., Bertolin J., Jimenez V., Jaen M.L., Garcia M., Pujol A., Vila L., Sacristan V., Barbon E., Ronzitti G., et al. Treatment of infantile-onset Pompe disease in a rat model with muscle-directed AAV gene therapy. Mol. Metab. 2024;81 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2024.101899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li X., Eastman E.M., Schwartz R.J., Draghia-Akli R. Synthetic muscle promoters: activities exceeding naturally occurring regulatory sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999;17:241–245. doi: 10.1038/6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarcar S., Tulalamba W., Rincon M.Y., Tipanee J., Pham H.Q., Evens H., Boon D., Samara-Kuko E., Keyaerts M., Loperfido M., et al. Next-generation muscle-directed gene therapy by in silico vector design. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:492. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08283-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colella P., Sellier P., Costa Verdera H., Puzzo F., van Wittenberghe L., Guerchet N., Daniele N., Gjata B., Marmier S., Charles S., et al. AAV Gene Transfer with Tandem Promoter Design Prevents Anti-transgene Immunity and Provides Persistent Efficacy in Neonate Pompe Mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019;12:85–101. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eggers M., Vannoy C.H., Huang J., Purushothaman P., Brassard J., Fonck C., Meng H., Prom M.J., Lawlor M.W., Cunningham J., et al. Muscle-directed gene therapy corrects Pompe disease and uncovers species-specific GAA immunogenicity. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.15252/emmm.202113968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang P., Sun B., Osada T., Rodriguiz R., Yang X.Y., Luo X., Kemper A.R., Clay T.M., Koeberl D.D. Immunodominant liver-specific expression suppresses transgene-directed immune responses in murine pompe disease. Hum. Gene Ther. 2012;23:460–472. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poupiot J., Costa Verdera H., Hardet R., Colella P., Collaud F., Bartolo L., Davoust J., Sanatine P., Mingozzi F., Richard I., Ronzitti G. Role of Regulatory T Cell and Effector T Cell Exhaustion in Liver-Mediated Transgene Tolerance in Muscle. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019;15:83–100. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dornelles A.D., Junges A.P.P., Pereira T.V., Krug B.C., Gonçalves C.B.T., Llerena J.C., Jr., Kishnani P.S., de Oliveira H.A., Jr., Schwartz I.V.D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Late-Onset Pompe Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/jcm10214828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ripolone M., Violano R., Ronchi D., Mondello S., Nascimbeni A., Colombo I., Fagiolari G., Bordoni A., Fortunato F., Lucchini V., et al. Effects of short-to-long term enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) on skeletal muscle tissue in late onset Pompe disease (LOPD) Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2018;44:449–462. doi: 10.1111/nan.12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elmallah M.K., Falk D.J., Nayak S., Federico R.A., Sandhu M.S., Poirier A., Byrne B.J., Fuller D.D. Sustained correction of motoneuron histopathology following intramuscular delivery of AAV in pompe mice. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:702–712. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shieh P.B., Kuntz N.L., Dowling J.J., Müller-Felber W., Bönnemann C.G., Seferian A.M., Servais L., Smith B.K., Muntoni F., Blaschek A., et al. Safety and efficacy of gene replacement therapy for X-linked myotubular myopathy (ASPIRO): a multinational, open-label, dose-escalation trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22:1125–1139. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tabebordbar M., Lagerborg K.A., Stanton A., King E.M., Ye S., Tellez L., Krunnfusz A., Tavakoli S., Widrick J.J., Messemer K.A., et al. Directed evolution of a family of AAV capsid variants enabling potent muscle-directed gene delivery across species. Cell. 2021;184:4919–4938.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vu Hong A., Suel L., Petat E., Dubois A., Le Brun P.R., Guerchet N., Veron P., Poupiot J., Richard I. An engineered AAV targeting integrin alpha V beta 6 presents improved myotropism across species. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:7965. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-52002-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun B., Li S., Bird A., Yi H., Kemper A., Thurberg B.L., Koeberl D.D. Antibody formation and mannose-6-phosphate receptor expression impact the efficacy of muscle-specific transgene expression in murine Pompe disease. J. Gene Med. 2010;12:881–891. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Byrne P.I.B.J., Collins S., Mah C.C., Smith B., Conlon T., Martin S.D., Corti M., Cleaver B., Islam S., Lawson L.A. Phase I/II trial of diaphragm delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus acid alpha-glucosidase (rAAaV1-CMV-GAA) gene vector in patients with Pompe disease. Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev. 2014;25:134–163. doi: 10.1089/humc.2014.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Earley J., Piletska E., Ronzitti G., Piletsky S. Evading and overcoming AAV neutralization in gene therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41:836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gross D.A., Tedesco N., Leborgne C., Ronzitti G. Overcoming the Challenges Imposed by Humoral Immunity to AAV Vectors to Achieve Safe and Efficient Gene Transfer in Seropositive Patients. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.857276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leborgne C., Barbon E., Alexander J.M., Hanby H., Delignat S., Cohen D.M., Collaud F., Muraleetharan S., Lupo D., Silverberg J., et al. IgG-cleaving endopeptidase enables in vivo gene therapy in the presence of anti-AAV neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1096–1101. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arruda V.R., Stedman H.H., Haurigot V., Buchlis G., Baila S., Favaro P., Chen Y., Franck H.G., Zhou S., Wright J.F., et al. Peripheral transvenular delivery of adeno-associated viral vectors to skeletal muscle as a novel therapy for hemophilia B. Blood. 2010;115:4678–4688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-261156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chauhan M., Daugherty A.L., Khadir F.E., Duzenli O.F., Hoffman A., Tinklenberg J.A., Kang P.B., Aslanidi G., Pacak C.A. AAV-DJ is superior to AAV9 for targeting brain and spinal cord, and de-targeting liver across multiple delivery routes in mice. J. Transl. Med. 2024;22:824. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05599-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hordeaux J., Dubreil L., Robveille C., Deniaud J., Pascal Q., Dequéant B., Pailloux J., Lagalice L., Ledevin M., Babarit C., et al. Long-term neurologic and cardiac correction by intrathecal gene therapy in Pompe disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017;5:66. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0464-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Foust K.D., Nurre E., Montgomery C.L., Hernandez A., Chan C.M., Kaspar B.K. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miyake N., Miyake K., Yamamoto M., Hirai Y., Shimada T. Global gene transfer into the CNS across the BBB after neonatal systemic delivery of single-stranded AAV vectors. Brain Res. 2011;1389:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ayuso E., Mingozzi F., Montane J., Leon X., Anguela X.M., Haurigot V., Edmonson S.A., Africa L., Zhou S., High K.A., et al. High AAV vector purity results in serotype- and tissue-independent enhancement of transduction efficiency. Gene Ther. 2010;17:503–510. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boerkoel C.F., Exelbert R., Nicastri C., Nichols R.C., Miller F.W., Plotz P.H., Raben N. Leaky splicing mutation in the acid maltase gene is associated with delayed onset of glycogenosis type II. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;56:887–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in the manuscript are available upon reasonable request.