Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is a highly infectious disease of paramount public health importance. COVID-19 is mainly transmitted via human-to-human contact. This could be through self-inoculation resulting from failure to observe proper hand hygiene and infection control practices. Our objective was to develop a quantitative risk assessment (QRA) model for determining the efficacy of wearing makeup as a mitigation in reducing COVID-19 transmission between genders. Utilizing the epidemiologic problem oriented approach methodology, after reviewing different published literature, and data collected from different sources including Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), selected journals, and reports, a comprehensive knowledgebase was developed. A conceptual scenario tree drown based on the knowledgebase. Variables were grouped into five major parameters. Monte Carlo simulations of QRA parameters were run utilizing @Risk software. The probability of COVID-19 transmission due to the face-touching frequency times per hour ranged from 2.30 × 10−7 to 3.87 × 10−5 with the mean and standard deviation (SD) of 7.93 × 10−6 and 6.37 × 10−6 respectively. The probability of transmission due to T-zone touching frequency times per hour for all the participants and those females who usually wear makeup and both males and few females who do not, with values ranging from 9.66 × 10−8 to 7.20 × 10−6 with the mean and SD of 1.85 × 10−6 and 1.29 × 10−6 respectively. Females were the less likely to touch their faces (45%), compared to males (55%). Females were less likely to touch their faces and contact with the T-zone when wearing makeup (24%) than that of those who did not (62%). Wearing makeup is a way to create a barrier between your face, especially the T-zone and your contaminated hands. The use of makeup can be utilized as a mitigation, which reduces the likelihood of face touching and thus in the transmission of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Behavior, Gender, quantitative risk assessment, Sensitivity Analysis, Monte Carlo simulations

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly infectious viral disease of the respiratory system caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Coronaviruses belong to the family Coronaviridae. These viruses cause illnesses such as the common cold, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and was first discovered in 2019 in the Wuhan region of China. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on 30 January 2020, and a pandemic on 11 March 2020 (Mayo Clinic, 2020). When infectious diseases like COVID-19 are prevalent, the health of infected people is impaired, and individuals’ quality of life declines (Vietri et al., 2013). Therefore, infectious disease control is important for people’s healthy lives. This usually results in reduced economic losses, which are due to the burden of medical expenses, high absenteeism and even death (Bramley et al., 2002). Most respiratory infections are transmitted by self-inoculation. Self-inoculation can be defined as a form of contact transmission whereby, a person’s contaminated hands make subsequent contact with other body sites on oneself and introduces contaminated material to those sites (Nicas and Best, 2008; Di Giuseppe et al., 2008). Coronavirus is transmitted via human-to-human contact. This could be through self-inoculation resulting from failure to observe proper hand hygiene and infection control practices. During seasonal outbreaks, the face-touching frequency has the potential to become a mechanism of contamination and transmission. In some people, the face-touching behavior seems to be an unconscious, natural reaction (Barclay and Nyarko, 2020). The infection route through indirect contact is established by touching one’s own facial mucous membranes with fingers that have touched shared contaminated items exposed to infected people such as through coughing, sneezing and fomites (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005). In public places, it is useful to investigate the infection route by contact of fingers with the face because many people share many environmental surfaces. The quantification in the role of the face-touching in the spread of respiratory infections is difficult (Kwok et al., 2015). The literature on self-inoculation mechanisms of common respiratory infections (e.g., influenza, coronavirus) is lacking (Winther et al., 2007; Gwaltney and Hendley, 1982; Gu et al., 2015). The face-touching behavior in the community was commonly observed with individuals touching their faces on average 3.3 times per hour during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic (Macias, 2009). In the health care setting, the frequent face-touching, particularly during periods of seasonal endemics or outbreaks, has the theoretical potential to be a mechanism of acquisition and transmission (Nicas and Best, 2008). It has been reported that by touching your facial mucous membranes, you give a virus 11 chances every hour if you have touched contaminated surfaces. The risk of picking up a virus by hand contact with the face depends on many factors, including virus type, nonporous surface, the time the virus was left on the surface, the time the infected person spent in the surface, the temperature and humidity levels (The New York Times, 2020).

Although, the WHO notes that while it is not known how long the COVID-19 virus survives on surfaces, it seems to behave like other coronaviruses that is disturbing news (The New York Times, 2020). In a recent study, it was found that similar coronaviruses have been shown to survive on surfaces for up to nine days under ideal conditions, which is far longer than the flu virus that typically can survive only up to 24 hours on hard surfaces (The New York Times, 2020; Kampf et al., 2020). The infection risk from coronavirus (COVID-19) following contamination of the environment decreases over time. It is not yet clear at what point there is no risk. However, studies of other coronaviruses like SARS and MERS in the same family suggest that, in most circumstances, the risk is likely to be reduced significantly after 72 hours (The New York Times, 2020). In general, a virus will survive the longest on nonporous surfaces made of metal and plastics including doorknobs, counters and railings. A virus will die sooner on fabrics or tissues. Once on your hand, a virus begins to lose potency, but it will probably live long enough for you to touch your face (The New York Times, 2020).

The survival of COVID-19 have been evaluated, on different surfaces. The environmental stability of viable COVID-19 is up to 3 hours in the air post aerosolisation, 4 hours on copper, 24 hours on cardboard, and 2–3 days on plastic and stainless steel (van Doremalen, 2020). In restricted environment like that found in hospitals, COVID-19 was also detected on objects such as the self-service printers (20.0%), desktop/keyboards (16.8%) and doorknobs (16.0%). Virus was detected most commonly on gloves (15.4%) but rarely on eye protection devices (1.7%). Both hand sanitizer dispensers and gloves were the most contaminated Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) 20.3% and 15.4% respectively (Ye et al., 2020; Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, 2020). This evidence indicates that fomites may play a role in transmission of COVID-19 but the relative importance of this route of transmission compared to direct exposure to respiratory droplets is still unclear (Coronavirus disease 2019, 2020). One of the more difficult challenges in public health has been to teach people to wash their hands frequently with soap and to stop touching their facial mucous membranes of the eyes, nose and mouth (T-zone) (Figure 1) (Morita et al., 2019), all entry portals for the COVID-19 and many other germs. Scratching the nose, rubbing your eyes, leaning on your chin and your fingers go next to your mouth there are multiple ways it can be done. Everybody touches their face, and it is a difficult habit to break (Elder, et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Classification of the face-touching area (Modified from Morita et al., 2019).

The relationship between the differences in face-touching frequencies and individual characteristics showed that within the course of an hour on average face-touching frequency and T-zone-touching frequency were 17.8 and 8.0 times respectively (Morita et al., 2019). While in another study conducted by Kwok et al., 2015 showed that within the course of an hour, students touched their faces, on average, 23 times. Nearly half of the touches were to the eyes, nose or mouth (T-zone) (Kwok et al., 2015). Considering the gender, the face-touching frequency was significantly higher for the males than for the females. With increased face-touching frequency, the frequency of contact with the T-zone increased and this increase in face-touching frequency may increase the risk of infection. For all face-touching, 42.2% involved the mucous membranes (T-zone) and 57.8%, involved the non-mucosal membranes (Morita et al., 2019). Skin conditions have an effect in face-touching frequencies. Considering the presence or absence of makeup, over the course of an hour, participants who usually wear makeup touched their faces, on average 12.4 times and 22.0 times for those who do not. The face-touching frequency of those who did not wear makeup was significantly higher than that of those who did. It can be assumed that those who usually wear makeup irrespective of their gender may worry that their makeup could blotch due to face touching, and thereby, they tend to avoid touching their faces. There is a possibility that the face-touching frequency may be reduced in people with skin-related factors, such as makeup and skin symptoms, which need to be considered (Morita et al., 2019).

As a precaution to minimize the spread of COVID-19 pandemic, the primary advice from health care officials is for public to wash their hands frequently with soap. In addition, the public health expert’s message also should include a more forceful warning about the danger of transmission of this virus through face touching (The New York Times Report, 2020). Therefore, in this study our objective was to develop a quantitative risk assessment (QRA) model for determining the efficacy of wearing makeup in reducing COVID-19 transmission between genders. We hypothesized that focusing on gender, the face-touching frequency was significantly higher for the males than for the females. Focusing on the skin condition, the face-touching frequency of those who did not wear makeup was significantly higher than that of those who did. The significant gender differences may depend on the makeup. 301-890-2052

Materials and Methods

This Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA) for COVID-19 is based on a comprehensive review of published literature that addresses various aspects pertaining to viruses from the family Coronaviridae specifically to which COVID-19 belongs. The Epidemiologic Problem Oriented Approach (EPOA) methodology was used to gather the fundamental information and data, which are used in the variable and parameter estimations and analysis (biological, mathematical, statistical and computer simulations) used for risk assessments and modeling (Habtemariam, 1989; Yu et al., 1997; Nganwa et al., 2010). The EPOA consists of two generic steps; problem identification and problem solving. Using the EPOA, a knowledgebase was developed after reviewing several different published literature, and the data was collected from different sources including Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), selected journals and reports (Kwok et al., 2015; The New York Times Report, 2020; Kampf et al., 2020; Morita et al., 2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020; Zarracina, J., and Rodriguez, A., 2020).

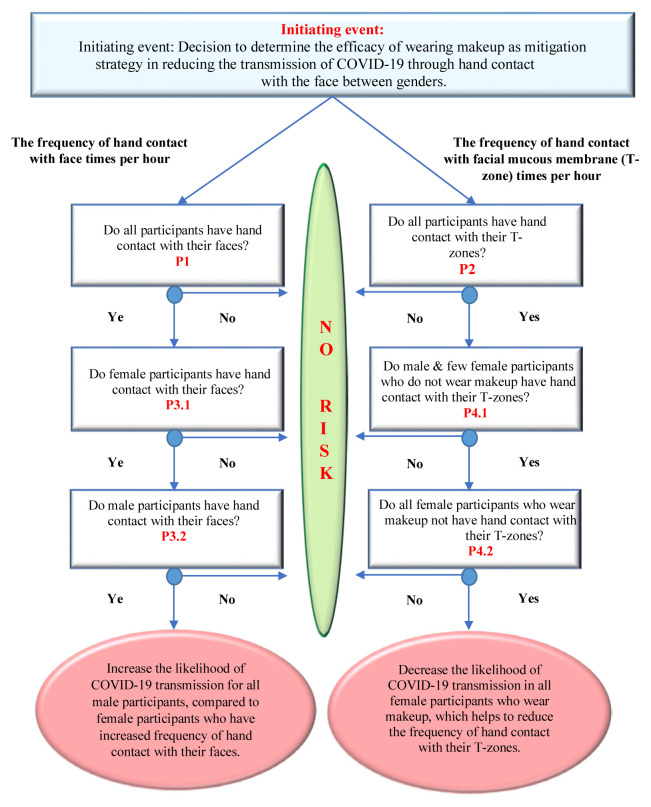

The risk pathway (Scenario Tree) presented in Figure 1 is a pictorial presentation of a sequence of specific events (nodes along the scenario tree) and at each node or even a specific question related to the risk of transmission of COVID-19 through face-touching frequencies is asked. A probability distribution is determined for each parameter using the collected data for each node. The product of these probability distributions to these questions will determine the final risk related to the likelihood of transmission of COVID-19 infection through hand contact with the face and facial mucous membranes of the eye, nose and mouth (T-zone) by gender. However, other relevant behavioral factors such as the face-touching frequency of those who usually wear makeup than that of those who do not, determines to some extent the efficacy of wearing makeup in reducing COVID-19 transmission between genders were also included in this study. The variables are organized into seven major parameter estimations or categories (Figure 2). These are the input parameters. Monte Carlo simulations with iterations set at 10,000 iterations for the QRA input parameters of COVID-19 transmission were executed utilizing @Risk software (Palisade Corporation). Sensitivity analysis was used to show the aggregate effect of what each input variable has on the likelihood of face-touching frequencies in the COVID-19 transmission. @ Risk Uniform distributions at each of the nodes were used to determining the efficacy of wearing makeup in reducing COVID-19 transmission between genders.

Figure 2.

Risk pathway (Scenario tree) for the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the face frequency and facial mucous membrane (T-zone) frequency times per hour by skin condition (makeup) and gender.

The QRA methods are extensions of standard statistical and epidemiological methods (Habtemariam, et al., 2005), which are expressed numerically and enable one to evaluate the likelihood and consequences of an adverse event occurring (Murray N, 2002). In a QRA, each parameter requires to be described and scientific evidence presented for the justification of the parameter estimates. In this study, we used the uniform distribution or rectangular distribution, which is a family of continuous probability distributions, and the minimum and maximum values are within a specified range of between 0 and 1. The quantified parameter values of the model were presented in terms of Risk Uniform function (Uniform distributions) (Engineering Statistic Handbook, 2012). This used to describe a form uniform probability distribution where every possible outcome has an equal likelihood of happening over a given range for a continuous distribution. For this reason, it is important as a reference distribution. One of the most important applications of the uniform distribution is in the generation of random numbers (Engineering Statics Handbook, 2012). In this study, uniform distributions were used to capture the uncertainty of the input parameters and variables, as this value is coming from a sample population. To see the effect of various inputs on the output, sensitivity analysis was performed using regression tornado graphs, and tables of regression coefficient.

Parameter estimations

Initiating event: Decision to determine the efficacy of wearing makeup as mitigation strategy in reducing the transmission of COVID-19 through hand contact with the face between genders.

N- The total number of participants who took part in the study.

Description: In a QRA using Monte Carlo simulation, uncertain inputs in a model are represented using ranges of possible values known as probability distributions. Using probability distributions, variables can have different probabilities of different outcomes occurring. Probability distributions are a much more realistic way of describing uncertainty in variables of a risk analysis (Palisade, Risk Analysis). As show in Table 1, in this study, the inputs are (N = minimum (40) and maximum (68), the probability distribution = 0.0054 (Morita et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Parameter estimations

| Notation | Definition | Distribution type, @Risk function and calculated values used in the model | Probability distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Number of participants | Uniform Distribution, @Risk Uniform (min, max), min= 40, max=68 | 48 |

| P1 | The probability of frequency of face-touching times per hour for all the participants is associated with the likelihood of transmission of COVID-19 infection through hand contact with the face. | Uniform Distribution, @Risk Uniform, (min, max) min= 0.0025, max= 0.0231 |

0.0054 |

| P2 | The probability of frequency of touching facial mucous membrane i.e. eyes, mouth and nose (T-zone) times per hour for all the participants is associated with the likelihood of infection transmission through hand contact with their T-zone. | Uniform Distribution, @Risk Uniform, (min, max) min= 0.0092, max= 0.0846 |

0.0346 |

| P3.1 | The probability of frequency of face-touching frequency times per hour for the female participants is associated with the likelihood of transmission of infection hand contact with the face. | Uniform Distribution, @Risk Uniform, (min, max) min= 0.00702, max= 0.0298 |

0.0292 |

| P3.2 | The probability of frequency of face-touching frequency times per hour for the male participants is associated with the likelihood of transmission of infection through hand contact with the face. | Uniform Distribution, @Risk Uniform, (min, max) min= 0.00780, max= 0.0593 |

0.0384 |

| P4.1 | The probability of frequency of facial mucous membrane touching (T-zone) frequency times per hour for both the female participants and male participants who do not wear makeup is associated with the likelihood of transmission of infection through hand contact with their T-zone. | Uniform Distribution, @Risk Uniform, (min, max) min= 0.00134, max= 0.0094 |

0.0049 |

| P4.2 | The probability of frequency of facial mucous membrane touching (T-zone) frequency times per hour for all the female participants who usually wear makeup is associated with the likelihood of infection transmission through hand contact with their T-zone. | Uniform Distribution, @Risk Uniform, (min, max) min= 0.0053, max= 0.0095 |

0.0084 |

Scientific evidence presented for the justification of the parameter estimates were obtained from the following sources:. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), selected journals, and reports (Kwok et al., 2015; The New York Times Report, 2020; Kampf et al., 2020; Morita et al., 2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020; Zarracina, J., and Rodriguez, A., 2020).

Probability distribution: The probability distributions of individual variables were determined by using the @Risk Uniform distributions, @RiskUniform (minimum, maximum) (Table 1). The general formula for the probability density function of the uniform distribution is (Engineering Statistics Handbook, 2012):

| (1) |

Where A is the location parameter and (B - A) is the scale parameter. The case where A = 0 and B = 1 is called the standard uniform distribution. The equation for the standard uniform distribution is

| (2) |

P1- The probability of face-touching frequency times per hour for all the participants is associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with their faces:

Total of the face-touching frequency: The general mathematical formula used for calculating the total (T) of the face-touching frequency (P1, P3.1, P3.2), and facial mucous membrane (T-zone)-touching frequency (P2, P4.1, P4.2) times per hour for all the participants is as follows:

| (3) |

Whereby, T(1–6) represent the parameters for all the face-touching frequencies (P1, P3.1, P3.2) and the T-zone-touching (P2, P4.1, P4.2) times per hour for all the participants (See Table 1 for details); Ave (1, 2) is the Average of hand contact with the face, 1, 2 is the face touching and T-zone-touching respectively; N is the number of participants; min, max is the minimum and maximum number of participants respectively.

Frequency percentage: The general mathematical formula used for calculating the frequency percentage (F) of the face-touching frequency (P1, P3.1, P3.2), and facial mucous membrane (T-zone)-touching frequency (P2, P4.1, P4.2) times per hour is as follows:

| (4) |

Whereby, F(min, max) is the minimum and maximum frequency percentage for all face-touching times per hour; N (min, max) (1–6)) is the minimum and maximum number for each of all the face-touching frequencies (P1, P3.1, P3.2) and the T-zone-touching (P2, P4.1, P4.2) times per hour for all the participants; T(1–6) represent the parameters for all the face-touching frequencies (P1, P3.1, P3.2) and the T-zone-touching (P2, P4.1, P4.2) times per hour (See Table 1 for details).

This specific variable is the frequency of hand contact with the face times per hour for all the participants. The inputs are (min = minimum (0.0025) and max = maximum (0.0231), the probability distribution is = 0.0054 (See Table 1) (Morita et al., 2019). The probability distribution values for this variable were determined by @RiskUniform as described previously in parameter N.

P2- The probability of facial mucous membrane i.e. eyes, mouth and nose (T-zone) touching frequency times per hour for all the participants is associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with their T-zones:

This specific variable is the frequency percentage of hand contact with the facial mucous membrane (T-zone) times per hour for all the participants. The variable input values for this parameter P2 are calculated using the same mathematical formulas (3) and (4) in parameter P1. The inputs are (min = minimum (0.0092) and max = maximum (0.0846), the probability distribution is = 0.0346 (See Table 1) (Morita et al., 2019). The probability distribution values for this variable were determined by @RiskUniform as described previously in parameter N.

P3.1- The probability of the face-touching frequency times per hour for the females is associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with their faces:

This specific variable is the frequency of hands contact with the face times per hour for the females. The variable input values for this parameter P2 are calculated using the same mathematical formulas (3) and (4) in parameter P3.1. The inputs are (min = minimum (0.00702) and max = maximum (0.0298), the probability distribution is = 0.0292 (See Table 1) (Morita et al., 2019). The probability distribution values for this variable were determined by @RiskUniform as described previously in parameter N.

P3.2 The probability of the face-touching frequency times per hour for the males is associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with their faces:

This specific variable is the frequency of hand contact with the facial mucous membrane (T-zone) times per hour for the males. The variable input values for this parameter P3.2 are calculated using the same mathematical formulas (3) and (4) in parameter P1. The inputs are (min = minimum (0.00780) and max = maximum (0.0593), the probability distribution is = 0.0384 (See Table 1) (Morita et al., 2019). The probability distribution values for this variable were determined by @RiskUniform as described previously in parameter N.

P4.1- The probability of the facial mucous membrane touching (T-zone) frequency times per hour for both the males and few females who do not wear makeup is associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission of through hand contact with their T-zones:

This specific variable is the frequency of hand contact with the T-zone times per hour for both the males and few females who do not wear makeup. The variable input values for this parameter P4.1 are calculated using the same mathematical formulas (3) and (4) in parameter P1. The inputs are (min = minimum (0.00134) and max = maximum (0.0094), the probability distribution is = 0.0049 (See Table 1) (Morita et al., 2019). The probability distribution values for this variable were determined by @RiskUniform as described previously in parameter N.

P4.2- The probability of the facial mucous membrane touching (T-zone) frequency times per hour for all the females who usually wear makeup is associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with their T-zones:

This specific variable is the frequency of hand contact with the T-zone times per hour for all the females who usually wear makeup. The variable input values for this parameter P4.2 are calculated using the same mathematical formulas (3) and (4) in parameter P1. The inputs are (min = minimum (0.0053) and maximum = max (0.0095), the probability distribution is = 0.0084 (See Table 1) (Morita et al., 2019). The probability distribution values for this variable were determined by @RiskUniform as described previously in parameter N. Morita et al., 2019 in their study showed that within a course of one hour all the female participants who wear makeup had at the minimum no hand contact with their T-zones. However, in our study when developing the QRA using the Uniform distribution we assumed that some of the female participants had hand contact with their T-zones for at least at minimum of two times per hour.

Results

Results of the analysis show that the face-touching frequency times per hour for all the participants (P1), the face-touching frequency times per hour for the females (P4.1) and the face-touching frequency times per hour for the males (P4.2) are associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the face. The value of the product (P1x P3.1 xP3.2) for the likelihood of infection transmission through hand contact with the face times per hour for all the participants, the face-touching frequency times per hour for the females and the face-touching frequency times per hour for the males. This ranged from 2.30 × 10−7 to 3.87 × 10−5 with the mean and standard deviation of 7.93 × 10−6 and 6.37 × 10−6 respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Output summary statistics for the probability of COVID-19 transmission between gender through hand contact with the face and hand contact with facial mucous membrane (T-zone).

| @RISK Output statistics | The probability of face-touching frequency Times per hour associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission, for all participants | The probability of facial mucous membrane (T-zone)-touching frequency times per hour associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission, with respect to skin condition (makeup) and gender |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 2.30E-07 | 9.66E-08 |

| Maximum | 3.87E-05 | 7.20E-06 |

| Mean | 7.93E-06 | 1.85E-06 |

| Standard deviation | 6.37E-06 | 1.29E-06 |

| Mode | 2.84E-06 | 6.11E-07 |

| 5% | 1.19E-06 | 3.41E-07 |

| 95% | 2.12E-05 | 4.40E-06 |

The results in Table 2, in addition, show the facial mucous membrane (T-zone) touching frequency times per hour for all the participants (P2), the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour for both the males and few females who do not wear makeup (P4.1) and the T-zone touching frequency times per hour for all the females who usually wear makeup (P4.2) are associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with their T-zone. The value of the product (P2 x P4.1 x P4.2) is for the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the T-zone. This is due to: the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour for all the participants; the T-zone touching frequency times per hour for both the males and few females who do not wear makeup; and the T-zone touching frequency times per hour for all the females who usually wear makeup. This value ranged from 9.66 × 10−8 to 7.20 × 10−6 with the mean and standard deviation of 1.85 × 10−6 and 1.29 × 10−6 respectively. Out of the 32 female participants and the 36 male participants, only two females were among the participants who responded that they did not wear makeup. Those two female participants who were not wear makeup were added to the male participants who did not wear makeup (Morita et al., 2019).

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis is the study of how the uncertainty in the output of a model or system (numerical or otherwise) can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in its inputs. A model can be highly complex, and as a result, its relationships between inputs and outputs may be poorly understood. Some or all of the model inputs are subject to sources of uncertainty, including errors of measurement, absence of information and poor or partial understanding of the driving forces and mechanisms (Tameru, et al., 2012). This uncertainty imposes a limit on the confidence in the response or output of the model. Further, models may have to cope with the natural intrinsic variability of the system. An evaluation of the confidence in the model is critical. This requires, first, a quantification of the uncertainty in any model results (uncertainty analysis); and second, an evaluation of how much each input is contributing to the output uncertainty. Sensitivity analysis addresses the second of these issues (although uncertainty analysis is usually a necessary precursor), performing the role of ordering by importance the strength and relevance of the inputs in determining the variation in the output. In models involving many input variables, sensitivity analysis is an essential ingredient of model building and quality assurance (Tameru et al., 2012).

Sensitivity analysis results of selected variables that were examined together with their sensitivity ranking with respect to the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the face due to the face-touching frequency times per hour are given in Table 3 (a). The results of sensitivity analysis of three variables that were also examined for the sensitivity ranking for the likelihood of infection transmission through hand contact with their T-zone due to the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour are also presented in Table 3 (b). Table 3 (a) shows that the frequency of hand contact with the face times per hour for the all participants (0.58), the frequency of hands contact with the face times per hour for the males (0.55), and the frequency of hands contact with the face times per hour for the females (0.45) were strong predictors of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with their faces. The results in Table 3 (b) indicate that the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour for all the participants (0.66), the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour for males and few females who do not wear makeup (0.62), and the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour for all the females who usually wear makeup (0.24) were strong predictors of infection transmission through hand contact with their T-zones.

Table 3.

Sensitivity ranking for the probability of COVID-19 transmission due to: (a) the face-touching frequency times per hour and (b) facial mucous membrane (T-zone)-touching frequency times per hour.

| Sensitivity Ranking by Coefficient Regression | Variables | Regression Coefficient Value |

|---|---|---|

| (a) The probability of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the face due to the face-touching frequency times per hour, for all participants. | ||

| 1 | The probability of the frequency of hand contact with the face times per hour for all participants | 0.58 |

| 2 | The probability of the frequency of hand contact with the face times per hour for the males | 0.55 |

| 3 | The probability of the frequency of hand contact with the face times per hour for the females | 0.45 |

|

| ||

| (b) The probability of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the facial mucous membrane (T-zone) due to the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour | ||

| 1 | The probability of the frequency of T-zone -touching times per hour for all participants | 0.66 |

| 2 | The probability of the frequency of T-zone-touching times per hour for males and few females who do not wear makeup | 0.62 |

| 3 | The probability of the frequency of T-zone-touching times per hour for all the females who wear makeup | 0.24 |

Tornado graphs Regression coefficients tell you the size of the effect each input has on the output

The tornado graphs (Figures 5 – 6) provide pictorial representations of sensitivity analyses of the simulation results and Tables 3 (a) and (b) show simulation results in tabular form. The tornado graph shows the influence of how much each specific input distribution has, on the change in the values of the corresponding specific output distribution (Gerbi et al., 2012). In these cases, the regression coefficients provide a measure of how much the output would change if the input were changed by one standard deviation (Palisade Insight, 2008). The tornado graph is useful for identifying the key variables and uncertain parameters that are driving the results of the model. They are also useful to check that the model is behaving as we expect. The horizontal range the bars cover give some measure the input distribution’s influence on the selected model output (Gerbi et al., 2012).

Figure 5.

Sigmoid curve showing the probability (P2 × P4.1 × P4.2) of facial mucous membrane (T-zone)-touching frequency times per hour associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission with respect to skin condition (makeup) and gender.

Figure 6.

Tornado graph showing the probability of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the facial mucous membrane (T-zone), due to the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour, with respect to skin condition (makeup) and gender.

As shown in Figure 5, the uncertainties of the variables “the frequency of hand contact with the face times per hour for the all participants” was 0.58 and “the frequency of hands contact with face times per hour for the males” was 0.55. These were higher when compared with the uncertainties of the variable “the frequency of hands contact with the face times per hour for the females” was 0.45. Figure 6, shows that the uncertainties of the variables “the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour for all the participants” was 0.66 and “the T-zone-touching frequency times per hour for the males and few females who do not wear makeup” was 0.62. These were higher when compared with the uncertainties of the variable “the T-zone times per hour for all the females who usually wear makeup” was 0.24.

Discussion

As the COVID-19 pandemic spreads across the world canceling major events, closing schools, upending the stock markets and disrupting travel and normal life people are trying to adopt to this new phenomenon. Americans are taking precautions against the new coronavirus that causes the disease sickening and killing thousands worldwide (Zarracina and Rodriguez, 2020). In health care associated infections, hands are considered a common vector for transmission (Wertheim, et al., 2005; Wertheim, et al., 2006; Gebreyesus, et al., 2013) and have been implicated in the transmission of respiratory infections (Macias, 2009; Pittet, et al., 2006; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2019). The face-touching behavior in the community was commonly observed with individuals touching their faces on average 3.3 times per hour during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, (Macias, 2009).

In a previous study by Kwok et al., 2015, it was observed that the high frequency of mouth and nose touching behavior were on average, 4 times per hour for mout-touching and 3 times per hour for nose. For this reason, performing hand hygiene is considered as an essential and less expensive preventive method for breaking the cycle of colonization and transmission. In order to further expand our knowledge on the role of the face-touching for self-inoculation, models of infection transmission and comparison of transmission efficiency of self-inoculation against other transmission routes are required (Kwok et al., 2015).

In this study, an exhaustive review of literature on the epidemiology and determinants of infection transmission like COVID-19 has been organized into two major categories. From these categories relevant data for building the epidemiologic model for factors influencing infection transmission through hand contact with the face practices was derived. Touching behavior in a public place influences the risk of hand contact with contaminated surfaces because public places may have many environmental surfaces contaminated with pathogens. The face-touching behavior problems and negative belief about reducing the likelihood of this behavior may contribute to the high probability of COVID-19 infection transmission within high-risk populations (The New York Times Report, 2020). Epidemiologic modelling is an essential research tool that scientists can employ to quantify the contribution of each face touching risky behaviors to examine alternative strategies for effective interventions that lead to better planning and policy-making for all disease control and prevention efforts (Gerbi et al., 2012).

Morita et al., 2019 found that on average, each of the 68 observed participants participated in their study touched their face 17.8 times per hour. During on average of an hour participants touched their facial mucous membranes (T-zones) 8.0 times. When comparing the face-touching behavior frequency by gender, the face-touching frequency was significantly lower for the females than for the males. Morita et al., 2019 also showed that the frequency of the T-zone-touching behavior increased with increased the face-touching frequency. Of all the face-touching frequencies behavior, 42.2% involved contact with the T-zones, and 57.8%, with the non-mucosal membrane, the result of the mucosal contact ratio was similar to the past study by Kwok et al., 2015. While, Kwok et al., 2015, in their study highlighted the frightening of the face-touching frequency behavior in individuals. During on average of an hour, each of the 26 student participants touched their faces 23 times. Of all the face-touching frequencies behavior, 44% involved the T-zone touching, whereas 56% of contacts involved the nonmucosal membrane. Nearly half of the T-zone-touching were to the eyes, nose or mouth. Consequently, Kwok et al., 2015 discovered that the T-zone-touching frequency were 36% involved the mouth, 31% involved the nose, 27% involved the eyes, and 6% were a combination of these regions. When comparing the average of 17.8 times per hour of the 68 participants for their face-touching frequency (Morita et al., 2019) and the average of 23 times per hour for the 26 participants for their face-touching frequency (Kwok et al., 2015) observed in their studies respectively. This difference in average frequencies may be attributable to the behavior of wearing makeup, whereby of the 68 participants, 30 of them were wearing makeup, which reduces the face-touching frequency (Morita et al., 2019).

In addition, in a previous study the researchers reported that the randomly selected people in public places in Brazil and the US touched surfaces in public places about 3.3 times per hour, and their mouth or nose about 3.6 times per hour (National Health Service (NSH), 2012). The researchers also revealed that people are not likely to be able to wash their hands this frequently when they are out in public places. They suggest that during outbreaks, additional public health messages are needed to inform people of the risk of touching contaminated public surfaces in public places and then touching their faces. The study does not challenge the fact that handwashing is a simple, effective way to reduce your risk of being infected with bacteria and viruses that can be transmitted by hand contact with contaminated surfaces (National Health Service (NSH), 2012).

Similarly, given the habitual face-touching behavior observed in our study we developed a QRA model for determining the efficacy of wearing makeup in reducing COVID-19 transmission between genders. As a result, the mean for the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the T-zone was significantly less likely (1.85 × 10−6 times per hour), for all the participants including the females who wear makeup and those males and few females who do not. This was compared to the participants who touch their faces; their mean for the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission by the face-touching frequency was significantly higher (7.93 × 10−6 times per hour). Considering the gender, our study also showed that the females were less likely to touch their faces (45%), compared to the males who were more likely to touch their faces (55%).

In a previous study, considering the presence or absence of makeup, within a course of an hour the average face-touching frequency was 12.4 times for the participants who usually wear makeup, and 22.0 times for those who do not. It has been shown that the frequency of face-touching and contact with facial mucous membranes (T-zone) of those who do not wear makeup was significantly higher compared with those who do. Only two females were among the participants did not wear makeup. The significant differences by gender might be due to the makeup, which is possible to reduce effectively face-touching frequency and, hence, infection risk (Morita et al., 2019). In their study, they assumed that those who usually wear makeup tend to avoid touching their faces because they might be worried that their makeup would blotch due to face-touching (Morita et al., 2019). Similarly, in this study we ascertained the effectiveness of wearing makeup in reducing the likelihood of hand contact with face and hence reducing COVID-19 transmission between genders. Females were less likely to touch their faces, especially the T-zone when wearing makeup (24%) than that of those who did not (62%). Wearing makeup is a way to create a barrier between your face, especially the T-zone and your contaminated hands.

Conclusion

To date, only a limited number of studies have examined the impact of hand hygiene as an essential and inexpensive preventive method to break the COVID-19 colonization and transmission cycle associated with self-inoculation. In this study, we measured and determined the efficacy of wearing makeup in reducing effectively the face-touching frequency behavior and, hence, COVID-19 transmission risk between genders. The frequency of face touching behavior and contact with the T-zone was higher for the males than for the females. The difference may depend on the use of makeup, as the face-touching frequency of those who did wear makeup was significantly lower than that of those who did not. Epidemiological Models of COVID-19 transmission and comparison of transmission efficiency of self-inoculation against other transmission routes are required to further expand our knowledge on the role of the face-touching behavior of self-inoculation. These models can also be used to compare the efficacy of different mitigations of COVID-19 that might reduce the likelihood of a high level of hand-to-face contacts behavior with the mucosal or nonmucosal membranes, self-inoculation and, hence, transmission risk.

Recommendations

One of the more difficult challenges in public health has been to teach people to wash their hands frequently and to stop touching their facial mucous membranes of the eyes, nose and mouth known as the T-zone, all entry portals for the new coronavirus and many other germs. In this study, we suggest that during outbreaks, additional urgent public health messages are needed to inform people of the risk of touching contaminated public surfaces and then touching their faces. Therefore, we recommend that:

The first step to breaking or altering a habit is to develop a strong awareness of when and why you engage in such behavior. For something like the face-touching or nail biting, it can be an impulsive thing done out of boredom, anxiety or a sensory need.

Further epidemiological research is needed to replicate and expand upon these findings. As this study has focused on individual-level behavior risk factors. Future research and interventions related to COVID-19 transmission must focus more keenly on demographic and socioeconomic factors, different skin conditions (e.g., the presence or absence of dry, sensitive skin), pollution awareness of the environmental surfaces in public places, behavior content conditions (e.g., the face-touching frequency should be measured while participants are using their smartphone).

Figure 3.

Sigmoid curve showing the probability (P1 × P3.1 × P3.2) of the face-touching frequency times per hour associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission for all participants.

Figure 4.

Tornado graph showing the probability of COVID-19 transmission through hand contact with the face due to the face-touching frequency times per hour, for all participants.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Tuskegee University Center for Biomedical Research/Research Centers in Minority Institutions (TU CBR/RCMI) Program at the National Institute of Health (NIH) with a CBR/RCMI U54 grant, with grant number MD007585.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Ehsan Abdalla, DVM, MSc (Hons) (Vet PATH), MSc & PhD (Epidemiology and Risk Analysis): Is the first author and major conceiver and designer of the manuscript. Participated and made major contributions to the analysis, interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. Critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

David Nganwa, DVM, MPH: Is the second author, have given significant intellectual inputs to the work, participated in the conceiving and designing of the manuscript. Made major contributions to analysis, interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. Critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

Authors Note: This study was funded by the Tuskegee University Center for Biomedical Research/Research Centers in Minority Institutions (TU CBR/RCMI) Program at the National Institute of Health (NIH) with a CBR/RCMI U54 grant, with grant number MD007585. The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

References

- Mayo Clinic. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/symptoms-causes/syc-20479963.

- Vietri J, Prajapati G, El Khoury ACBMC. The burden of hepatitis C in Europe from the patients’ perspective: a survey in 5 countries. Gastroenterol. 2013;17(13):16. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramley TJ, Lerner D, Sames M. Productivity losses related to the common cold. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(9):822–829. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicas M, Best D. A study quantifying the hand-to-face contact rate and its potential application to predicting respiratory tract infection. J Occup Environ Hygiene. 2008;5(6):347–52. doi: 10.1080/15459620802003896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiuseppe G, Abbate R, Albano L, Marienelli P, Angelillo I. A survey of knowledge, attitudes and practices towards avian influenza in an adult population of Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay L, Nyarko E.COVID-19: Medscape Education Clinical Briefs: What Do We Know About Transmission Routes and Surface Survival? 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/927708.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Pandemic Influenza Plan, Supplement 4 Infection Control. 2005. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pdf/professionals/hhspandemicinfluenzaplan.pdf.

- Winther B, McCue K, Ashe K, Rubino J, Hendley J. Environmental contaminationwith rhinovirus and transfer to fingers of healthy individuals by daily life activity. J Med Virol. 2007;79(10):1606–10. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney J, Hendley J. Transmission of experimental rhinovirus infection by contaminated surfaces. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;116(5):828–33. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Zhong Y, Hao Y, Zhou D, Tsui H, Hao C, et al. Preventive behaviors and mental distress in response to H1N1 among University students in Guangzhou China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP1867–79. doi: 10.1177/1010539512443699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias A, Torre A, Moreno-Espinosa S, Leal P, Bourlon M, Palacios G. Controlling the novel A (H1N1) influenza virus: don’t touch your face! J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(3):280–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok YLA, Gralton J, McLaws ML. American Journal of Infection Control. 2015;43(2):112–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times. Stop Touching Your Face! 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/02/well/live/coronavirus-spread-transmission-face-touching-hands.html.

- Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2020;104(3):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. Doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye G, Lin H, Chen L, Wang S, Zeng Z, Wang W, et al. Environmental contamination of the SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare premises: An urgent call for protection for healthcare workers. medRxiv. 2020. Retrieved from: https://europepmc.org/article/PPR/PPR117559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – seventh update, 25 March 2020. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/symptoms-causes/syc-20479963.

- Elder NC. Hand hygiene and face touching in family medicine offices: a Cincinnati Area Research and Improvement Group (CARInG) network study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(3):339–46. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.03.130242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K, Hashimoto K, Ogata M, Tsutsumi H, Tanabe S, Hori S. Measurement of Face-touching Frequency in a Simulated Train. E3. SWeb of Conferences. 2019;111(22027):4. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/201911102027. Doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Habtemariam T. Utility of epidemiologic simulations model in the planning of trypanosomiasis control programs. 1989. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 69(Suppl 1):109–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Habtemariam T, Wilson S, Oryang D, Nganwa D, Obasa M, Robnett V. A risk analysis model of foot and mouth disease (FMD) virus introduction through deboned beef importation. Preventive Veterinary medicine. 1997;1997;30:49–59. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(96)01085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nganwa D, Habtemariam T, Tameru B, et al. 2010Applying the epidemiologic problem oriented approach (EPOA) methodology in developing a knowledge base for the modeling of HIV/ADSEthn Dis201 Suppl 1S1-173–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Cases, Data, and Surveillance. 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/index.html.

- Zarracina J, Rodriguez A.What does the coronavirus do to your body? Everything to know about the infection process: A visual guide of coronavirus infection, symptoms of COVID-19 and the effects of the virus inside the body, in graphics. 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/2020/03/13/what-coronavirus-does-body-covid-19-infection-process-symptoms/5009057002/

- Habtemariam T, Tameru B, Ahmed A, Nganwa D, Ayanwale L, Beyene G, Robnett V. Role of Risk Assessment in Managing Risk. Agriculture Outlook Forum. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Murray N. Import Risk Analysis: Animal and Animal Products, Ministry of Agricultural and Forestry. New Zealand: Wellington; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Engineering Statics Handbook. Uniform Distribution. 2012. Retrieved from: https://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/eda/section3/eda3662.htm. Doi: [DOI]

- Tameru B, Gerbi G, Nganwa D, Bogale A, Robnett V, Habtemariam T. The Association between Interrelationships and Linkages of Knowledge about HIV/AIDS and its Related Risky Behaviors in People Living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of AIDS and Clinical Research. 2012;3(7):1–7. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.S7-002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim H, Melles D, Vos M, Van Leeuwen W, Van Belkum A, Verbrugh H, et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(12)(05):751–62. 70295. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Sax H, Dharan S, Pessoa-Silva C, Donaldson L, et al. Evidence-based model for hand transmission during patient care and the role of improved particles. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(10):641–52. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70600-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebreyesus A, Gebre-Selassie S, Mihert A. Nasal and hand carriage rate of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among healthcare workers in Mekelle hospital, North Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2013;51(1):41–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Clinical signs and symptoms of influenza: influenza prevention & control recommendations. 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/clinical.htm.

- Gerbi GB, Habtemariam T, Tameru B, Nganwa D, Robnett V. A quantitative risk assessment of multiple factors influencing HIV/AIDS transmission through unprotected sex among HIVseropositive men. AIDS Car. 2012;24(3):331–339. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.608418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palisade Insight. Tornado Graphs: Basic Interpretation. 2008. Retrieved from: https://blog.palisade.com/2008/10/24/tornado-graphs-basic-interpretation/

- Kwok YLA, Gralton J, McLaws ML. Face touching: a frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(2):112–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service (NSH) Coronavirus: stay at home: Not touching face may help cut flu risk. 2012. Retrieved from: https://www.nhs.uk/news/medical-practice/not-touching-face-may-help-cut-flu-risk/