Abstract

Heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) is a powerful strategy for natural product (NP) discovery, yet achieving consistent expression across microbial hosts remains challenging. Here, we developed cross-phyla vector systems enabling the expression of BGCs from cyanobacteria and other bacterial origins in Gram-negative Escherichia coli, Gram-positive Bacillus subtilis, and two model cyanobacterial strains including unicellular Synechocystis PCC 6803 and filamentous Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Following validation using constitutive and inducible expression of enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP), we applied these vectors to express the shinorine and violacein BGCs in all four hosts. Promoter tuning, substrate feeding, BGC refactoring, and inducible control enhanced NP production and mitigated host toxicity. Notably, we demonstrated that B. subtilis can serve as a chassis for cyanobacterial NP BGC expression. Our results provide versatile expression platforms for probing BGC function and accelerating natural product discovery from diverse cyanobacterial and other bacterial lineages.

Keywords: Biosynthetic gene clusters, broad-host-range vectors, synthetic biology, mycosporine-like amino acids, violacein, cyanobacteria

Graphical Abstract

Microbial natural products (NPs) possess remarkable structural and functional diversity, underpinning their broad applications in medicine, agriculture, and other fields. The genetic information required for NP biosynthesis typically resides in contiguous genomic regions known as biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Advances in DNA sequencing and bioinformatics have notably accelerated NP discovery through genome mining.1, 2 However, over 80% of identified BGCs remain cryptic under standard laboratory conditions, mainly due to unknown regulatory cues required for activation.3 This crypticity represents a significant bottleneck in uncovering microbial chemical diversity.

Heterologous expression of BGCs has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome crypticity, allowing researchers to produce and characterize novel NPs in genetically tractable host organisms.5–7 Indeed, successful heterologous expression not only facilitates the elucidation of biosynthetic mechanisms but also enhances product titers, enables discovery from environmental DNA, and generates novel NP derivatives. However, heterologous BGC expression remains unpredictable due to limiting factors such as precursor availability, transcriptional and translational regulation, enzyme modifications, and intermediate or product toxicity.6 To address these challenges, significant efforts have focused on developing synthetic biology tools such as optimized promoters, ribosome binding sites (RBSs), and CRISPR-based genome engineering to enhance predictable expression and reduce host metabolic burdens.5, 8–11 Recognizing the inherent uncertainties associated with expressing BGCs in any single host, recent synthetic biology approaches have prioritized multi-chassis platforms.12 Notably, chassis-independent recombinase-assisted genome engineering (CRAGE) enables heterologous expression of BGCs of different NP families in diverse Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria.13 Additional advances include broad-host-range plasmids facilitating gene expression across various Pseudomonadota14 and cross-kingdom systems enabling bacterial BGC expression in Gram-negative and -positive bacteria and yeast.15 Furthermore, a recent report demonstrated the dynamic regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis and Corynebacterium glutamicum.10

Cyanobacteria, a diverse group of Gram-negative photoautotrophic bacteria, produce structurally complex and bioactive NPs, some of which have inspired FDA-approved therapeutics.16 Recent genome mining initiatives identified approximately 56,000 cyanobacterial BGCs.17 Yet, their translation into tangible chemical products remains limited by difficulties in genetic manipulation of native producers, even if cultivable, and inadequate heterologous expression platforms.5, 8 Furthermore, microbial communities associated with cyanobacterial mats, often comprising Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinomycetes, represent untapped reservoirs of NP diversity,18, 19 hindered by the lack of effective synthetic biology tools for leveraging these complex microbial assemblages.

In this study, we developed versatile broad-host-range plasmid systems to facilitate the expression of cyanobacterial and other bacterial BGCs across multiple synthetic biology chassis. Utilizing the broad-host-range RSF1010 origin of replication (ori), our developed vectors contain constitutive and inducible promoters optimized for Gram-negative Escherichia coli, Gram-positive Bacillus subtilis, and two model cyanobacterial strains including unicellular Synechocystis PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis) and filamentous Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (hereafter Anabaena). Demonstrating the utility of these cross-phyla vectors for the expression of enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP), we successfully expressed the shinorine BGC from marine filamentous cyanobacterium Westiella intricata UH HT-29-120 and the violacein BGC from marine γ-proteobacterium Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea.21, 22 This work establishes a robust foundation for harnessing NP biosynthetic potential across diverse bacterial phyla, especially within complex cyanobacterial communities.

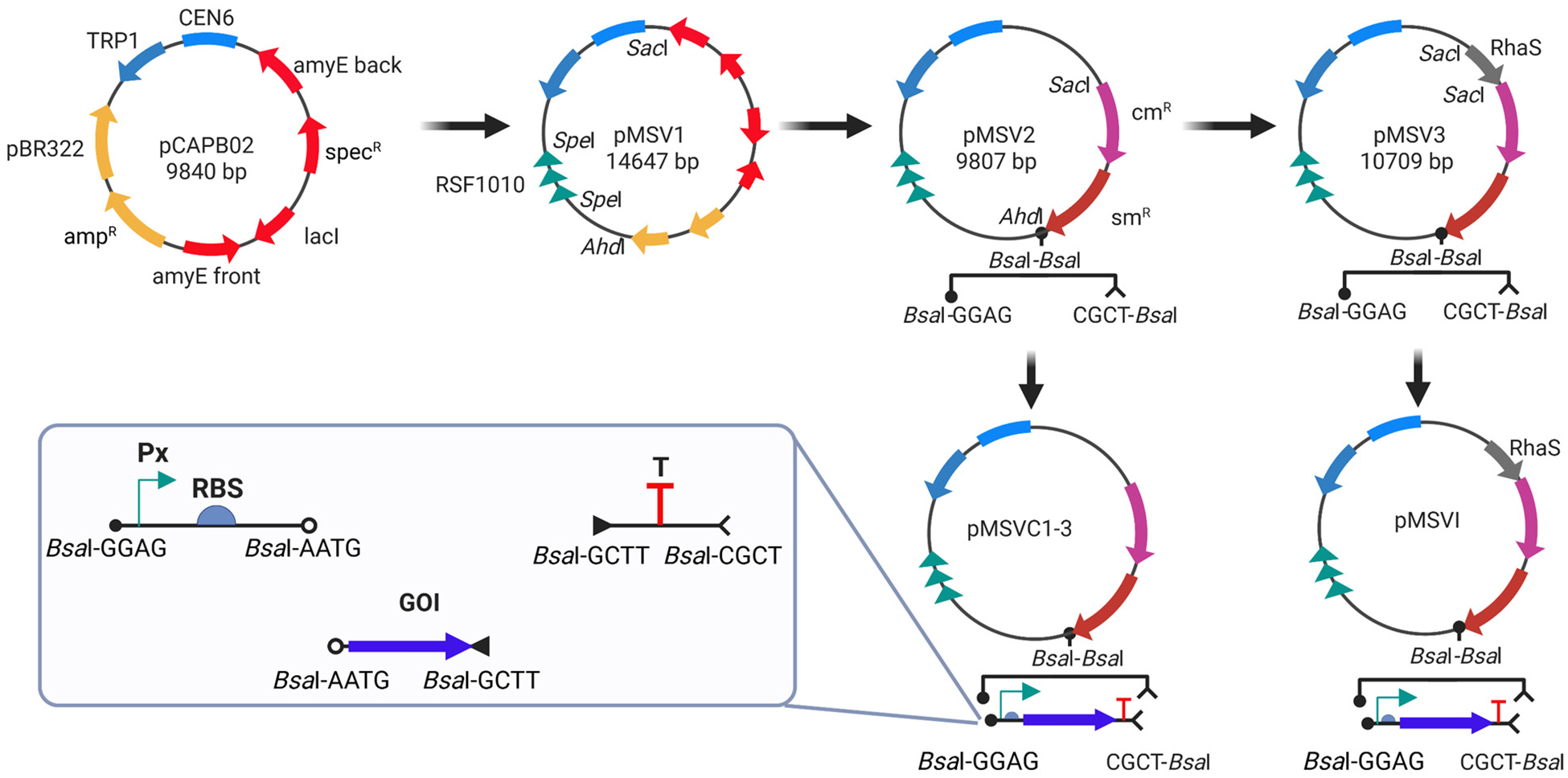

As illustrated in Figure 1, the construction of the expression vectors involved three essential design considerations: (1) selection of a broad-host-range ori enabling plasmid propagation across multiple bacterial hosts; (2) assembly of broad-host-range genetic elements including constitutive or inducible promoters of varying strengths, RBSs, and terminators; and (3) cloning of genes of interest (GOIs). We started constructing the basal vector, pMSV1 (Table S1), by inserting the broad-host-range ori RSF1010 into the SpeI site of the pCAPB02 backbone (Table S2).23 The RSF1010 origin has served as the foundation for several shuttle vector systems designed for dual-host applications, notably in E. coli and cyanobacteria, such as the pVZ and pPMQAK1 platforms.24, 25 The pCAPB02 is a transformation-associated recombination cloning and expression vector, optimized for capturing and expressing large BGCs in Bacillus subtilis.23 It combines yeast and bacterial replication elements, making it a shuttle vector across multiple hosts. To create vectors compatible with the Golden Gate MoClo syntax validated in both cyanobacteria26 and E. coli,27 we removed the segment spanning from pBR322 to amyE back in pMSV1 using the AhdI and SacI restriction sites (Figure 1). We then inserted both chloramphenicol (cmR) and streptomycin (smR) resistance markers at the same sites, generating vector pMSV2 (Table S1). The cmR and smR markers, amplified from pACYCDuet™-1 and pCAPB02 respectively, were fused through PCR prior to insertion. Importantly, two adjacent sites of Type IIS restriction enzyme BsaI were included in the reverse primer used for smR amplification for facilitating subsequent modular cloning of genetic elements such as promoters, RBSs, and terminators (Figure 1). In this study, we prioritized promoters previously validated for functionality in cyanobacterial strains, specifically constitutive promoters PJ23119, Ptrc, and Ptac, along with the rhamnose-inducible promoter Prham.26, 28 For translational and transcriptional control, we employed the broad-host-range RBS BBa_B0034 and the rrnB terminator (TrrnB).26 Leveraging the BsaI-based modular approach, we constructed three constitutive expression vectors from pMSV2, pMSVC1–3 with GOI expression under promoters PJ23119, Ptrc and Ptac, respectively (Table S1). To develop the rhamnose-inducible vector, we first amplified the transcriptional activator gene rhaS from the previously constructed pRL838-rApra.28 The rhaS gene was fused with the constitutive promoter PJ23119 and inserted into the SacI site of pMSV2, generating pMSV3 (Figure 1). The final inducible vector, pMSVI, was constructed by cloning the PrhaBAD promoter, RBS BBa_B0034, the rrnB terminator and GOI into pMSV3. All constructed vectors were verified by sequencing to ensure accuracy and eliminate any potential errors introduced during construction (Table S3).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram exhibiting approaches for generations of different constitutive and inducible expression cassettes.

We first evaluated the performance of the four expression vectors in E. coli, B. subtilis, Synechocystis, and Anabaena by expressing eYFP (Table S2).26 E. coli BAP1 was transformed using chemical methods,29 while B. subtilis 168 was transformed via natural competence.23 Both cyanobacterial strains, Synechocystis and Anabaena, were transformed by triparental mating.28, 30 Transformed E. coli and B. subtilis were selected on LB agar containing chloramphenicol and streptomycin, whereas successful transformation in cyanobacteria cultured in BG11 medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics was confirmed by PCR after several rounds of segregation (Figure S1). Considering the distinct growth characteristics of the tested strains, direct cross-chassis comparisons of eYFP expression were impractical. Instead, fluorescence signals driven by different promoters within each strain were normalized to growth for evaluation (Figure 2). Among the three constitutive promoters tested, PJ23119 consistently exhibited the strongest activity across all four chassis, generating normalized fluorescence signals 24 to 32% higher than the second strongest promoter (often Ptrc). Additionally, the rhamnose-inducible promoter Prham was functional in all chassis tested, showing an increase in normalized fluorescence intensity ranging from 8-fold in B. subtilis to 35-fold in Synechocystis compared to uninduced controls. These findings confirmed the successful development of versatile multi-chassis constitutive and inducible expression systems suitable for evaluating GOI expression across diverse bacterial phyla.

Figure 2.

Expression of eYFP driven by constitutive and inducible promoters in E. coli (A), B. subtilis (B), Synechocystis (C) and Anabaena (D). Fluorescent signals of eYFP in these strains were normalized against their growth, OD600 for E. coli and B. subtilis and OD730 for cyanobacteria. E. coli and B. subtilis were cultured in LB, 37 °C, 250 rpm, 24 h before fluorescence measurement for constitutive eYFP expression. Synechocystis and Anabaena were cultured in BG11 for 48 h and 72 h, respectively, before fluorescence measurement. Strains transformed with empty vectors served as negative controls. For inducible expression, the inducer (I) rhamnose (1 mg/mL) was incubated with E. coli and B. subtilis for 12 h, whereas cyanobacterial strains were incubated for 24 h post-induction. Negative control (N) had no inducer. Data represents the mean ± S.D. of at least three replicates.

Next, we evaluated the application of these vectors for BGC expression across the four microbial chassis. The first BGC selected was the mycosporine-like amino acid (MAA) cluster from the marine filamentous cyanobacterium Westiella intricata UH HT-29-1.20 MAAs are natural UV protectants produced by diverse organisms, particularly cyanobacteria.31 This BGC encodes four enzymes: dehydroquinate synthase homolog MysA, O-methyltransferase MysB, ATP-grasp enzyme MysC, and nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-like enzyme MysE (Figure 3A). MysA-B catalyze the conversion of sedoheptulose 7-phosphate (SH7P) into 4-deoxygadusol (4-DG), subsequently converted into mycosporine-glycine (MG) by MysC, and finally shinorine by MysE.30 Notably, MysE requires post-translational modification by 4’-phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase), such as Sfp from B. subtilis32 or APPT from Anabaena.33 The shinorine BGC was amplified from W. intricata UH HT-29-1 genomic DNA and cloned into pMSVC1, pMSVC2, and pMSVC3 (Figure S2) using specific primers (Table S4). The resultant constructs pMSVC1M, pMSVC2M, and pMSVC3M (Table S1) were introduced into E. coli BAP1 (harboring sfp),29 B. subtilis, and Anabaena. For Synechocystis, we co-transformed the APPT gene cloned into pRL838 along with these constructs. Transformations in cyanobacterial cells were confirmed by PCR amplification of the mysA gene, yielding a product of the expected size (Figure S3). HPLC and LC-MS analyses of methanolic extracts revealed successful shinorine BGC expression in all chassis (Figures S4–S5), with E. coli BAP1 showing the highest yield and B. subtilis the lowest. Expression of the shinorine BGC from different vectors had negligible impact on the growth of each chassis (Table S5). These results suggest that Gram-positive B. subtilis, whose GC content (~43%) resembles that of many cyanobacterial genomes, can serve as a chassis for the heterologous production of cyanobacterial BGCs, an outcome not commonly observed without codon optimization or extensive engineering.34 In E. coli, the dominant product was the biosynthetic intermediate 4-DG (4.5 to 6.6 mg/L), followed by shinorine and MG (Figures 3B and S6), with relative product ratios varying according to promoter strength. In contrast, expression of the shinorine BGC in B. subtilis predominantly accumulated MG as the major product (Figure 3C), with the highest MG yield (0.4 mg/L) observed when expression was driven by Ptac. In Synechocystis and Anabaena, shinorine was the dominant product (0.6 to 1.5 mg/L) (Figure 3D–E), with PJ23119 yielding the highest shinorine production. Anabaena supported higher overall production of shinorine and biosynthetic intermediates than Synechocystis. Nonetheless, the accumulation of biosynthetic intermediates likely reflects imbalanced expression of MysC and MysE, as previously reported.30, 35 To test this hypothesis, we refactored the shinorine BGC in pMSVC1M by inserting an additional PJ23119 promoter and RBS upstream of mysC and mysE, generating pMSVC1MR (Figure S2). Refactoring significantly enhanced shinorine yields across all four chassis (Figure 3). For example, shinorine production in B. subtilis increased by seven folds (Figure 3C). Collectively, these results demonstrated the versatility of our vector systems for simultaneous evaluation of multiple chassis in the heterologous expression of cyanobacterial BGCs.

Figure 3.

Biosynthetic pathway of shinorine (A) and constitutive expression of the wild type and refactored shinorine BGC in E. coli BAP1 (B), B. subtilis (C), Synechocystis (D) and Anabaena (E). The yields of 4-DG, MG and shinorinewere shown with gray, orange and green bars, respectively. Synechocystis and Anabaena were cultured in BG11 for 48 h and 72 h, respectively, before extraction and production analysis by HPLC. Strains transformed with empty vectors served as negative controls. Data represents the mean ± S.D. of at least three replicates. SH7P: sedoheptulose-7-phosphate; 4-DG: 4-deoxygadusol; MG: mycosporine-glycine.

To further evaluate the application of our vector systems across diverse bacterial BGCs, we expressed the violacein BGC from the marine γ-proteobacterium Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea.21, 22 Violacein biosynthesis begins with the oxidation of l-tryptophan into indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPA) imine by the FAD-dependent enzyme VioA. The heme-containing oxidase VioB then catalyzes dimer formation of IPA imine, which is converted into protodeoxyviolaceinic acid by the catalytic chaperone VioE (Figure S7).36 Sequential modifications by the flavin-dependent oxygenases VioC and VioD complete violacein biosynthesis.37 We separately amplified vioABE and vioCD from a plasmid (Addgene #7344033)38 using the specific primers (Table S4) and assembled them into a single BGC (Figure S8A), whose cloning resulted in pMSVC1V, pMSVC2V, and pMSVC3V for expression in all four chassis (Table S1). Transformations in cyanobacterial cells were confirmed by PCR amplification of the vioA gene, yielding a product of the expected size (Figure S9). HPLC and LC-MS analyses revealed that all constructs produced violacein in E. coli (Figures S10–S11) with yields ranging from 5.9 mg/L (Ptac) to 20.9 mg/L (PJ23119) (Figures 4A and S6). We also observed a low level of deoxyviolaceinic acid (up to 0.6 mg/L) as a side metabolite (Figure S12). The highest violacein yield in B. subtilis (0.7 mg/L) was also achieved using PJ23119 (Figure 4B). We found that expression of the violacein BGC from all vectors had negative impact on the growth of B. subtilis (Table S5). Indeed, violacein inhibits Gram-positive bacterial growth,39 and we determined its MIC against B. subtilis as 25 mg/L (Figure S13A), indicating room for further production improvement. In Synechocystis and Anabaena, low violacein levels (up to 0.4 mg/L under PJ23119) were detected only upon feeding 1 mM l-tryptophan (Figure 4C–D). To enhance production, we refactored the violacein BGC in pMSVC1V by inserting a PJ23119 promoter and RBS upstream vioDC, generating pMSVC1VR (Table S1, Figure S8B). Compared to the original construct (pMSVC1V), pMSVC1VR improved violacein yields by two- to five-fold across all four chassis (Figure 4). However, violacein accumulation in cyanobacteria remained limited (≤1.1 mg/L), likely due to its inhibitory effects, with determined MIC values of 6.25 mg/L for Synechocystis and 3.25 mg/L for Anabaena (Figure S13B). To mitigate potential toxicity, we constructed an inducible violacein expression system by separately controlling the expression of vioABE and vioDC by the Prham promoter in pMSVI, generating pMSVIVR pMSVC1VR (Table S1, Figure S8C). Except for in E. coli, inducible expression significantly improved violacein yields to 6.8 mg/L, 3.5 mg/L, and 2.3 mg/L in B. subtilis, Synechocystis, and Anabaena, respectively. Moreover, inducible expression enhanced the OD600 of B. subtilis from around 1.4 to 2.2 and resulted in a roughly 25% increase in Synechocystis biomass accumulation (Table S5). These results underscore the importance of testing different promoter systems to optimize BGC expression across diverse synthetic biology chassis. Furthermore, this work represents a rare example of successful heterologous production of a proteobacterial natural product in cyanobacterial chassis.

Figure 4.

Expression of the wild type and refactored violacein BGC in E. coli (A), B. subtilis (B), Synechocystis (C) and Anabaena (D). Transformed E. coli and B. subtilis were cultured in LB at 37 °C, 250 rpm for 24 h before HPLC analysis of violacein yield. Synechocystis and Anabaena were cultured in BG11 fed with 1 mM L-Trp. For the induced expression of the refactored BGC, rhamnose (1 mg/mL) was added to the culture medium of E. coli and B. subtilis for 12 h and cyanobacterial strains for 24 h. Data represents the mean ± S.D. of at least three replicates.

In conclusion, we successfully developed four cross-phyla vector systems for expressing BGCs of cyanobacterial and other bacterial origins across E. coli, B. subtilis, Synechocystis, and Anabaena. The use of different types of promoters enabled dynamic control of BGC expression, facilitating successful outcomes. While recent studies have explored multi-chassis strategies for heterologous expression,10, 13–15 our work uniquely centers on the longstanding and difficult challenge of expressing cyanobacterial BGCs.5, 40 Importantly, these vector systems, incorporating the broad-host-range ori RSF1010 and a universal RBS, can be applied to express BGCs in many other common and uncommon Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria.26, 41 Furthermore, this work showcased multiple strategies to facilitate NP production from their BGCs, including substrate feeding, BGC refactoring, and inducible expression to alleviate product toxicity. Collectively, our work offers valuable synthetic biology tools for NP discovery from microbial BGCs, particularly those from cyanobacterial assemblages.

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at XXX Experimental procedure, lists of plasmids, primers and genetic parts used in this study, sequences of pMSV1, pMSV2 and pMSV3 and optical densities of BGC expressing strains (Tables S1–S5), PCR confirmation of transformants (Figures S1, S3, and S9), HPLC and MS traces as well as MS spectra of metabolites (Figures S4, S5, S10 and S11), standard curves (Figure S6), deoxyviolaceinic acid yield (Figure S12), schematic diagram of the cloning of BGCs (Figures S2 and S8) and optimal density measurement (Figure S13) (PDF).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michelle C. Moffitt for providing the genomic DNA of Westiella intricata UH HT-29-1 and Dr. Pei-Yuan Qian for providing B. subtilis 168 strain. This work is supported by NIH grant R35GM128742 (Y.D.) and NIH grant RM1GM145426 (H.L., Y.D.). H.L. is also supported by the Debbie and Sylvia DeSantis Chair professorship. Figure 1 was created using Biorender.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- (1).Atanasov AG; Zotchev SB; Dirsch VM; International Natural Product Sciences Taskforce; Supuran CT Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 200–216. DOI: 10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Medema MH; de Rond T; Moore BS Mining genomes to illuminate the specialized chemistry of life. Nat Rev Genet 2021, 22, 553–571. DOI: 10.1038/s41576-021-00363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Calteau A; Fewer DP; Latifi A; Coursin T; Laurent T; Jokela J; Kerfeld CA; Sivonen K; Piel J; Gugger M Phylum-wide comparative genomics unravel the diversity of secondary metabolism in cyanobacteria. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 977. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Baunach M; Guljamow A; Miguel-Gordo M; Dittmann E Harnessing the potential: advances in cyanobacterial natural product research and biotechnology. Nat Prod Rep 2024, 41, 347–369. DOI: 10.1039/d3np00045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Chen M; Dhakal D; Eckhardt CW; Luesch H; Ding Y Synthetic biology strategies for cyanobacterial systems to heterologously produce cyanobacterial natural products. Nat Prod Rep 2025. DOI: 10.1039/d5np00009b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kadjo AE; Eustaquio AS Bacterial natural product discovery by heterologous expression. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2023, 50, kuad044. DOI: 10.1093/jimb/kuad044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zhang JJ; Tang X; Moore BS Genetic platforms for heterologous expression of microbial natural products. Nat Prod Rep 2019, 36, 1313–1332. DOI: 10.1039/c9np00025a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Dhakal D; Chen M; Luesch H; Ding Y Heterologous production of cyanobacterial compounds. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 48, :kuab003. DOI: 10.1093/jimb/kuab003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lopatkin AJ; Collins JJ Predictive biology: modelling, understanding and harnessing microbial complexity. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020, 18, 507–520. DOI: 10.1038/s41579-020-0372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Li Y; Wu Y; Xu X; Liu Y; Li J; Du G; Lv X; Li Y; Liu L A cross-species inducible system for enhanced protein expression and multiplexed metabolic pathway fine-tuning in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, gkae1315. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkae1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhao F; Sun C; Liu Z; Cabrera A; Escobar M; Huang S; Yuan Q; Nie Q; Luo KL; Lin A; Vanegas JA; Zhu T; Hilton IB; Gao X Multiplex base-editing enables combinatorial epigenetic regulation for genome mining of fungal natural products. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145, 413–421. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.2c10211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ke J; Yoshikuni Y Multi-chassis engineering for heterologous production of microbial natural products. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2020, 62, 88–97. DOI: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Wang G; Zhao Z; Ke J; Engel Y; Shi YM; Robinson D; Bingol K; Zhang Z; Bowen B; Louie K; Wang B; Evans R; Miyamoto Y; Cheng K; Kosina S; De Raad M; Silva L; Luhrs A; Lubbe A; Hoyt DW; Francavilla C; Otani H; Deutsch S; Washton NM; Rubin EM; Mouncey NJ; Visel A; Northen T; Cheng JF; Bode HB; Yoshikuni Y CRAGE enables rapid activation of biosynthetic gene clusters in undomesticated bacteria. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4, 2498–2510. DOI: 10.1038/s41564-019-0573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Keating KW; Young EM Systematic part transfer by extending a modular toolkit to diverse bacteria. ACS Synth Biol 2023, 12, 2061–2072. DOI: 10.1021/acssynbio.3c00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Patel JR; Oh J; Wang S; Crawford JM; Isaacs FJ Cross-kingdom expression of synthetic genetic elements promotes discovery of metabolites in the human microbiome. Cell 2022, 185, 1487–1505 e1414. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Weiss MB; Borges RM; Sullivan P; Domingues JPB; da Silva FHS; Trindade VGS; Luo S; Orjala J; Crnkovic CM Chemical diversity of cyanobacterial natural products. Nat Prod Rep 2025, 42, 6–49. DOI: 10.1039/d4np00040d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Udwary DW; Doering DT; Foster B; Smirnova T; Kautsar SA; Mouncey NJ The secondary metabolism collaboratory: a database and web discussion portal for secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D717–D723. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkae1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Martin-Andres I; Sobrado J; Cavalcante E; Quesada A Survival of an Antarctic cyanobacterial mat under Martian conditions. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1350457. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1350457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bolhuis H; Stal LJ Analysis of bacterial and archaeal diversity in coastal microbial mats using massive parallel 16S rRNA gene tag sequencing. ISME J 2011, 5, 1701–1712. DOI: 10.1038/ismej.2011.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Micallef ML; D’Agostino PM; Sharma D; Viswanathan R; Moffitt MC Genome mining for natural product biosynthetic gene clusters in the Subsection V cyanobacteria. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 669. DOI: 10.1186/s12864-015-1855-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Pemberton JM; Vincent KM; Penfold RJ Cloning and heterologous expression of the violacein biosynthesis gene-cluster from Chromobacterium violaceum. Curr Microbiol 1991, 22, 355–358. DOI: Doi 10.1007/Bf02092154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yang LH; Xiong H; Lee OO; Qi SH; Qian PY Effect of agitation on violacein production in isolated from a marine sponge. Lett Appl Microbiol 2007, 44, 625–630. DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Li Y; Li Z; Yamanaka K; Xu Y; Zhang W; Vlamakis H; Kolter R; Moore BS; Qian PY Directed natural product biosynthesis gene cluster capture and expression in the model bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 9383. DOI: 10.1038/srep09383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Huang HH; Camsund D; Lindblad P; Heidorn T Design and characterization of molecular tools for a Synthetic Biology approach towards developing cyanobacterial biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, 2577–2593. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkq164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zinchenko VV; Piven IV; Melnik VA; Shestakov SV Vectors for the complementation analysis of cyanobacterial mutants. Russ J Genet 1999, 35, 228–232. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Vasudevan R; Gale GAR; Schiavon AA; Puzorjov A; Malin J; Gillespie MD; Vavitsas K; Zulkower V; Wang B; Howe CJ; Lea-Smith DJ; McCormick AJ CyanoGate: A modular cloning suite for engineering cyanobacteria based on the plant MoClo syntax. Plant Physiol 2019, 180, 39–55. DOI: 10.1104/pp.18.01401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Moore SJ; Lai HE; Kelwick RJ; Chee SM; Bell DJ; Polizzi KM; Freemont PS EcoFlex: A multifunctional MoClo kit for E. coli synthetic biology. ACS Synth Biol 2016, 5, 1059–1069. DOI: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Dhakal D; Kallifidas D; Chen M; Kokkaliari S; Chen QY; Paul VJ; Ding Y; Luesch H Heterologous production of the C33-C45 polyketide fragment of anticancer apratoxins in a cyanobacterial host. Org Lett 2023, 25, 2238–2242. DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Pfeifer BA; Admiraal SJ; Gramajo H; Cane DE; Khosla C Biosynthesis of complex polyketides in a metabolically engineered strain of E. coli. Science 2001, 291, 1790–1792. DOI: 10.1126/science.1058092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Yang G; Cozad MA; Holland DA; Zhang Y; Luesch H; Ding Y Photosynthetic production of sunscreen shinorine using an engineered cyanobacterium. ACS Synth Biol 2018, 7, 664–671. DOI: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Chen M; Jiang Y; Ding Y Recent progress in unraveling the biosynthesis of natural sunscreens mycosporine-like amino acids. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2023, 50, kuad038 DOI: 10.1093/jimb/kuad038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Quadri LE; Weinreb PH; Lei M; Nakano MM; Zuber P; Walsh CT Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 1585–1595. DOI: 10.1021/bi9719861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Yang G; Zhang Y; Lee NK; Cozad MA; Kearney SE; Luesch H; Ding Y Cyanobacterial Sfp-type phosphopantetheinyl transferases functionalize carrier proteins of diverse biosynthetic pathways. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11888. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-12244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Castillo-Hair SM; Baerman EA; Fujita M; Igoshin OA; Tabor JJ Optogenetic control of Bacillus subtilis gene expression. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3099. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-10906-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Chen M; Rubin GM; Jiang G; Raad Z; Ding Y Biosynthesis and heterologous production of mycosporine-like amino acid palythines. J Org Chem 2021, 86, 11160–11168. DOI: 10.1021/acs.joc.1c00368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ryan KS; Balibar CJ; Turo KE; Walsh CT; Drennan CL The violacein biosynthetic enzyme VioE shares a fold with lipoprotein transporter proteins. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 6467–6475. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M708573200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Balibar CJ; Walsh CT In vitro biosynthesis of violacein from L-tryptophan by the enzymes VioA-E from Chromobacterium violaceum. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 15444–15457. DOI: 10.1021/bi061998z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Cress BF; Jones JA; Kim DC; Leitz QD; Englaender JA; Collins SM; Linhardt RJ; Koffas MA Rapid generation of CRISPR/dCas9-regulated, orthogonally repressible hybrid T7-lac promoters for modular, tuneable control of metabolic pathway fluxes in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 4472–4485. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkw231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Cauz ACG; Carretero GPB; Saraiva GKV; Park P; Mortara L; Cuccovia IM; Brocchi M; Gueiros-Filho FJ Violacein targets the cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria. ACS Infect Dis 2019, 5, 539–549. DOI: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Philmus B; Avalon NE; Ding Y; Doering DT; Eustaquio AS; Gerwick WH; Luesch H; Orjala J; Sutherland S; Taton A; Udwary D Green genes from blue greens: challenges and solutions to unlocking the potential of cyanobacteria in drug discovery. Nat Prod Rep 2025. DOI: 10.1039/d5np00016e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Scherzinger E; Bagdasarian MM; Scholz P; Lurz R; Ruckert B; Bagdasarian M Replication of the broad host range plasmid RSF1010: requirement for three plasmid-encoded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1984, 81, 654–658. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.