Abstract

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by a varying degree of severity that correlates with the reduction of SMN protein levels. Motor neuron degeneration and skeletal muscle atrophy are hallmarks of SMA, but it is unknown whether other mechanisms contribute to the spectrum of clinical phenotypes. Here, through a combination of physiological and morphological studies in mouse models and SMA patients, we identify dysfunction and loss of proprioceptive sensory synapses as key signatures of SMA pathology. We demonstrate that Type 3 SMA patients exhibit impaired proprioception, and their proprioceptive synapses are dysfunctional as measured by the neurophysiological test of the Hoffmann reflex (H-reflex). We further show moderate loss of spinal motor neurons along with reduced excitatory afferent synapses and altered potassium channel expression in motor neurons from Type 1 SMA patients. These are conserved pathogenic events found in both severely affected patients and mouse models. Lastly, we report that improved motor function and fatigability in ambulatory Type 3 SMA patients and mouse models treated with SMN-inducing drugs correlate with increased function of sensory-motor circuits that can be accurately captured by the H-reflex assay. Thus, sensory synaptic dysfunction is a clinically relevant event in SMA, and the H-reflex is a suitable assay to monitor disease progression and treatment efficacy of motor circuit pathology.

Keywords: Spinal Muscular Atrophy, motor neuron, proprioception, sensory synapses, sensory-motor circuit, neurodegenerative disease

Introduction

Studies in mouse models of human diseases are critical to gain insights into pathogenic mechanisms as well as to determine the efficacy and safety of potential treatments. However, determining whether knowledge acquired from studies in mice is applicable to patients can be challenging. This is especially the case in neurodegenerative disorders due to the difficulty of accessing neuronal circuits within the central nervous system in living patients. A prominent example of neurodegenerative diseases that affect motor circuits embedded in the spinal cord is spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). The dysfunction of sensory-motor circuits is a major pathogenic factor contributing to disease progression and severity in mouse models of SMA.1-4 However, whether the same mechanisms apply in SMA patients is currently unknown. This question is of particular clinical importance since the therapeutic landscape of SMA patients has changed dramatically with the introduction of three FDA-approved treatments.5 The current treatments increase life expectancy but do not fully restore motor function, calling for better understanding of disease mechanisms and development of additive therapies.

SMA is caused by homozygous inactivation of the survival motor neuron 1 gene (SMN1) and retention of at least one copy of the paralog gene SMN2, which is hypomorphic and results in ubiquitous deficiency of the SMN protein.6 SMA is a childhood-onset disorder characterized by a varying degree of severity, which correlates with the copy number of SMN2 genes.5 Historically, the severe form of SMA (Type 1) resulted in death by approximately two years after birth.7, 8 Individuals affected by the intermediate (Type 2) form of the disease never walk independently.9 Type 3 SMA patients are more mildly affected, yet present with significant motor impairments even when ambulatory.10 The hallmarks of the disease are loss of spinal motor neurons, skeletal muscle atrophy, and severe motor impairment.11, 12 Recently, three different SMN-inducing therapies have been approved for treatment of SMA patients.13-15 Despite some clinical efficacy, especially in extending survival of Type 1 patients, significant motor impairments still persist in the majority of treated patients.

SMA affects primarily proximal and axial muscles in humans16, 17, and studies in animal models of the disease revealed that functional disruption of sensory-motor circuits controlling these muscles contributes to motor deficits.1, 2, 4, 18-20 Accordingly, the dysfunction and loss of proprioceptive sensory synapses onto motor neurons is one of the most conserved, early pathogenic events across different mouse models of SMA.4, 21, 22 In the SMNΔ7 mouse model of SMA23, proprioceptive synapses release less glutamate, resulting in the reduction of Kv2.1 channel expression on motor neurons, effectively rendering them unable to fire repetitively.2 This ultimately contributes to impaired muscle contraction and diminished limb movements. Further underlying the significance of sensory synaptic defects in SMA, restoration of proprioceptive synaptic function improves motor behavior in both mouse and fly models of SMA.2, 20, 24, 25 Importantly, however, it is unknown whether similar mechanisms involving proprioceptive synapses and consequent functional deficits in motor neuron output are at play in SMA patients and can be effectively targeted by current treatments.

Here, we utilized morphological and functional assays to determine whether proprioceptive sensory dysfunction characteristic of SMA mouse models is a disease feature in humans with SMA. We show that both SMNΔ7 mice and Type 3 ambulatory SMA patients display a marked reduction in the amplitude of the Hoffman reflex (H-reflex) compared to normal controls, demonstrating that proprioceptive sensory synapses are dysfunctional in SMA. This is further supported by evidence for the loss of proprioceptive synapses and dysregulated expression of Kv2.1 in SMA motor neurons from post-mortem tissue of Type 1 SMA patients. Lastly, we show that significant improvement in the H-reflex correlates with an increase in walking distance and a concomitant reduction in fatigability in Type 3 SMA patients treated with an SMN-inducing therapy. Taken together, our results demonstrate that proprioceptive synaptic dysfunction is a mechanistically conserved pathogenic event in both mouse models and SMA patients, which has the potential to modify disease severity if successfully targeted therapeutically.

Results

Ambulatory Type 3 SMA patients have defective proprioception

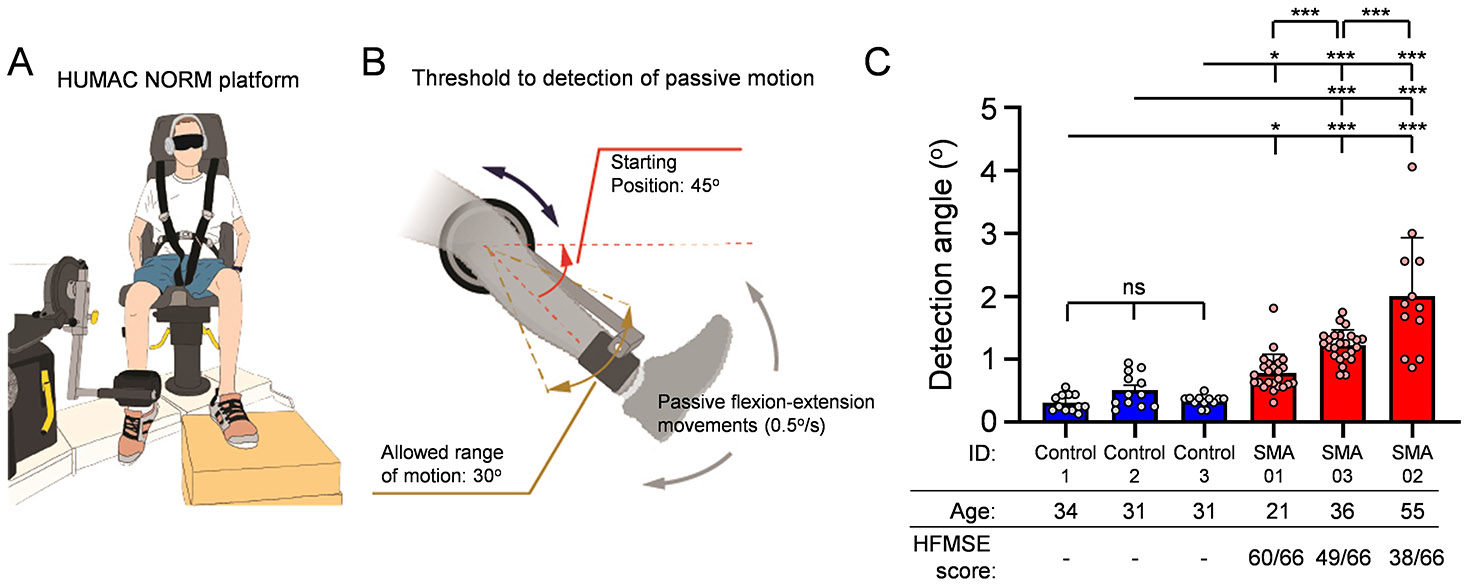

Despite strong evidence of proprioceptive sensory dysfunction in mouse models, it is unknown whether SMA patients exhibit any sensory deficits. Thus, we designed several sensitive assays to investigate whether proprioception is affected in ambulatory SMA patients. We first measured the angular difference in detection of passive movement of the knee at a constant speed of 0.5o/s, while the participants were both blind folded and aurally isolated (Fig. 1A). Three Type 3 SMA patients and three control participants were included in this study (see Methods and Table 2 in Supplemental Material). The test started from an initial position of the leg at 45° from the horizontal plane and then randomly selected flexion or extension movements were imposed to the knee joint (Fig. 1B). Remarkably, we found that all three SMA participants detected the movement at greater angles from the initial position compared to controls (Fig. 1C), indicative of impaired proprioception in SMA. Furthermore, we found that the deficit in detecting movement – illustrated by the higher detection angle – was proportional to the level of motor impairment for each participant as measured by the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded (HFMSE) score (the lower the score, the greater the impairment; Fig. 1C). These results provided the first indication that proprioception is impaired and correlates with disease severity in Type 3 SMA patients.

Figure 1. Proprioceptive dysfunction in SMA patients.

(A) Drawing of the testing platform. The Humac Norm was used to assess proprioception in SMA patients and controls. This platform allows for precise passive movement of the knee joint at minimal speed of 0.5°/s. (B) Protocol details of the proprioceptive assessment test. The initial position of the leg was at 45° from the horizontal plane. Randomly selected flexion or extension movements were imposed in the knee joint at a speed of 0.5°/s and a maximum range of motion of 30°. (C) Deficits in proprioception vs Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded (HMFSE) motor score in three SMA patients (red bars) and three control participants (blue bars). Each dot per participant represent the result from an individual trial. The HFMSE scores for the SMA participants are also shown (max value 66). Statistical comparisons were performed between each SMA patient to each participant from the control group. Statistical significance was calculated using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple post hoc comparisons test; *** p<0.001, * p<0.05; ns: no significance.

The H-reflex is affected in Type 3 SMA patients

To measure directly the functionality of sensory-motor synapses, we performed the H-reflex. We employed three Type 3 SMA participants who never received any SMN-inducing therapy, four Type 3 SMA patients that were under nusinersen treatment (between 9-18 months at the time of our investigation), and seven control participants (Table 3 in Supplemental Material and Methods). To quantify excitatory sensory drive to the spinal cord, we measured the strength of the monosynaptic reflex circuit with the H-reflex test from the left and right soleus muscle combined (Fig. 2A) and separately (Suppl. Fig. 1B-D). In all groups, the H-reflex was observed at the lowest stimulation intensities (Suppl. Fig. 1A), while the M-response (short for “Muscle”; caused by direct stimulation of motor neuron axons) was evident at higher stimulation intensities with a concomitant reduction of the H-reflex until its abolition (Fig. 2B and Suppl. Fig. 1A). The amplitude of the M-response was reduced by ~60% in participants with SMA compared to controls (Fig. 2B,C), likely reflecting neuromuscular junction (NMJ) denervation. Remarkably, the amplitude of the H-reflex was reduced by ~90% in naïve SMA individuals (Fig. 2B,D). Importantly, these absolute differences were reflected in the normalized H/M amplitude ratio (Fig. 2E), eliminating any confounds due to possible differences in muscle mass. The latency for the M response was unaltered while the latency for the H response was mildly increased in untreated SMA patients (Suppl. Fig. 1E,F). These findings demonstrate that the spinal monosynaptic reflex is affected in Type 3 SMA patients, indicating proprioceptive sensory dysfunction in humans. Interestingly, Type 3 SMA patients who were treated with nusinersen for ~1 year showed greater H-reflex amplitudes and significantly improved H/M ratios (Fig. 2B,D,E), but no difference in the amplitudes of the M responses (Fig. 2C) compared to untreated patients. Moreover, the same nusinersen-treated SMA patients performed significantly better in the six-minute walking test (6MWT) (Fig. 2F) and displayed less fatigability (Fig. 2G) than naïve SMA patients. These results highlight a correlation between increased H-reflex amplitude and improved motor function in Type 3 SMA patients following nusinersen treatment, which may reflect increased sensory-motor circuit function and preservation of proprioceptive synapses onto surviving motor neurons.

Figure 2. H-reflex is reduced in Type 3 SMA patients and improved following nusinersen treatment.

(A) Schematic showing the location of the electrodes for the H-reflex recorded from soleus muscles in human participant. (B) EMG recordings from soleus muscle following stimulation of the tibial nerve in control, untreated and nusinersen-treated SMA patients. Superimposed traces for maximum M- (green) and H- (magenta) responses are shown. Arrowheads indicate stimulus artefacts. Scale bar: 2mV, 10ms. Insets show magnified H-reflex responses. Scale bar: 1mV, 5ms. M-response amplitude (C), H-reflex amplitude (D) and H/M amplitude ratio (E) for control (N = 7) and SMA-untreated (N = 3) and nusinersen-treated (N = 4) of both left (triangle) and right (circle) legs of SMA Type 3 patients. Note that one treated SMA patient refused right side assessment (F) 6-minute-walk-test (6MWT) and (G) fatigability of the same untreated (N = 3) and nusinersen-treated (N = 4) SMA Type 3 patients. Data represent means and SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s test for (F), unpaired t test for (G), one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test (C-E).

The H-reflex is severely affected in sensory-motor circuits resistant to neurodegeneration

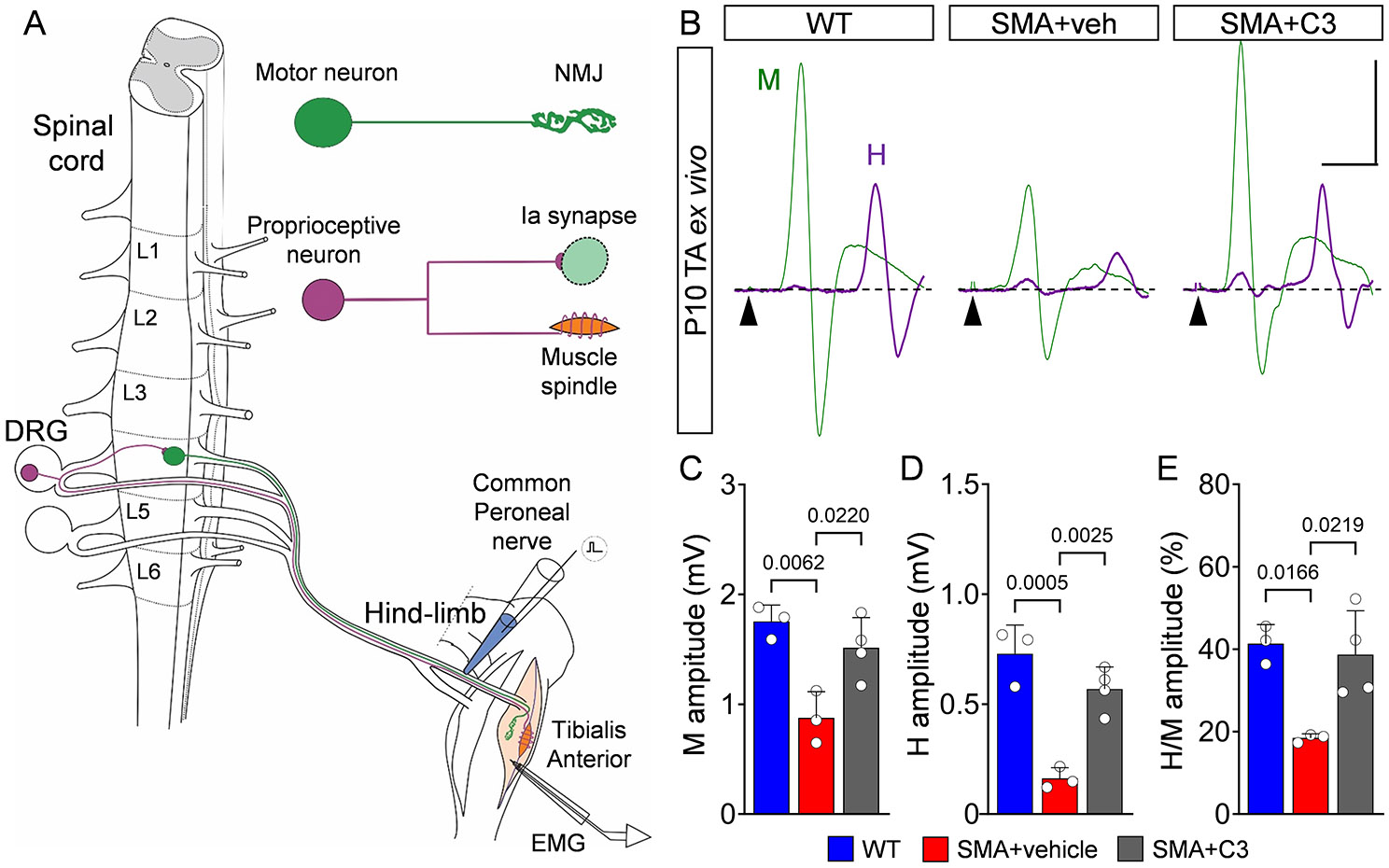

Proximal muscles are more vulnerable than distal ones in SMA patients16, 17 as well as in SMNΔ7 mice.1, 26 Accordingly, upper lumbar motor neurons (L1-L2) exhibit greater muscle denervation than caudal lumbar (L4-L5) motor neurons, which do not degenerate in SMA mice.1, 2, 27 Since mouse models that faithfully recapitulate milder SMA pathology are unavailable, we investigated neurodegeneration-resistant circuits in the caudal lumbar segments of SMNΔ7 mice as a proxy for motor circuits of Type 3 SMA patients. We employed the ex vivo spinal cord-hindlimb preparation and performed the H-reflex test from the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle in mice at P10 (Fig. 3A). Similar to humans, the H-reflex was evident at the lowest stimulation intensities of the common peroneal (CP) nerve (Suppl. Fig. 2A). At progressively greater stimulation intensities, the H-reflex was proportionally reduced while the M response increased in amplitude (Suppl. Fig. 2A). We confirmed the nature of the glutamatergic transmission of the H-reflex since pharmacological exposure to 10μM NBQX (AMPA receptor blocker) abolished the H-reflex leaving the cholinergic M-response relatively unaffected (Suppl. Fig. 2B). During early development, the H-reflex was also labile and prone to depression with eventual abolition following high frequency stimulation (10Hz), while the M-response was unaffected (Suppl. Fig. 2C). Importantly, SMA mice exhibited a marked reduction in both maximum M and H responses relative to normal controls (Fig. 3B-D), which was also reflected in reduction of the H/M ratio (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, the H-reflex amplitude was reduced by ~85% (Fig. 3D), whereas the M-response was reduced by ~45% in SMA (Fig. 3C). No differences were observed in the latency of either the M or H responses (Suppl. Fig. 2D), suggesting that the conduction velocities are not affected in either proprioceptive neurons or motor neurons. Akin to findings in milder Type 3 SMA patients, these results demonstrate that the H-reflex is severely affected in sensory-motor circuits of SMA mice that are resistant to neurodegeneration.

Figure 3. SMN therapy restores H-reflex in neonatal and juvenile SMA mice.

(A) Experimental setup to measure H-reflex using the spinal cord-hindlimb ex vivo preparation. The stretch reflex circuit consists of a motor neuron (MN) (green) and its neuromuscular junction (NMJ) synapse with its muscle, as well as a proprioceptive neuron (magenta) originating from a muscle spindle and making contact with a motor neuron via an Ia synapse. The common peroneal (CP) nerve was stimulated with an en passant electrode, while EMG was recorded from the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle. (B) TA EMG recordings following stimulation of the CP nerve in WT, vehicle-treated SMA and C3-treated SMA mice at P10. Superimposed traces for maximum M- (green) and H- (magenta) responses are shown. Arrowheads indicate stimulus artefacts. Scale bar: 0.5mV, 5ms. M-response amplitude (C), H-reflex amplitude (D) and H/M amplitude ratio (E) from WT (N = 4 mice) and SMA+vehicle (N = 4) and SMA+C3 (N = 5) mice at P10. (F) Drawing of a mouse highlighting the approximate location for stimulation of the sciatic nerve (red electrode) and the approximate location of the EMG electrode for the flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscle at the sole of the hindpaw. (G) In vivo EMG recordings form FDB muscle following stimulation of the sciatic nerve in WT and SMA mice treated daily with C3 compound at P30. Traces for M- and H- responses are shown in green. Arrowheads indicate stimulus artefact. Scale bar: 1mV, 2ms. Insets show magnified H-reflex in magenta. Scale bar: 50μV, 0.5ms. M-response amplitude (H), H-reflex amplitude (I), and H/M amplitude ratio (J) from WT (N = 4) and SMA+C3 (N = 9) mice at P30. Data represent means and SD. Statistical analysis was performed using an one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test (C-E), t-test (I) and Mann-Whitney test (H, J).

Pharmacological upregulation of SMN improves the H-reflex and sensory-motor circuit function in SMA mice

We sought to investigate whether upregulation of SMN would improve the H-reflex and sensory-motor circuit function in SMA mice. To do so, we treated SMNΔ7 mice with the SMN2 splicing modulator SMN-C328, an analogue of risdiplam which was previously shown to extend lifespan and significantly improve the overall SMA phenotype in this mouse model28. Accordingly, SMNΔ7 mice treated daily from P0 with 3mg/kg of C3 displayed elevated SMN protein levels in the spinal cord and increased number of gems in motor neurons (Suppl. Fig. 3A-D) resulting in a strong progressive improvement in righting (Fig. 4A), posture time (Fig. 4B), and weight gain (Fig. 4C). To evaluate the effect of SMN-C3 on sensory-motor circuit pathology, we performed a morphological analysis on the L1 vulnerable spinal segment of P10 SMNΔ7 mice. SMN-C3 treatment resulted in a modest rescue of vulnerable L1 motor neurons (Fig. 4D,E) and a reduction in p53 expression (Suppl. Fig. 3E,F), a pathway we previously identified as a driver of motor neuron death.25, 29, 30 SMN-C3 treated SMNΔ7 mice exhibited improved synaptic innervation of both proprioceptive neurons onto L1 motor neurons and NMJs on the axial muscle quadratus lumborum (Fig. 4F-I), consistent with the results of other studies.28, 31 We previously showed that the membrane expression of the potassium channel Kv2.1, which is essential for the functional output of motor neurons, is regulated by proprioceptive activity.2 The robust recovery of Kv2.1 membrane coverage in motor neurons of C3-treated SMNΔ7 mice indicates functional restoration of vulnerable motor neurons despite incomplete synaptic correction at the morphological level (Fig. 4J,K).

Figure 4. SMN therapy restores sensory-motor circuit function in SMA mice.

Righting time (A), posture time (B) and weight (C) of WT (blue, N = 12 mice), SMA+vehicle (red, N = 9), and SMA+C3 (grey, N = 14) mice. (D) Confocal images and (E) quantification of (ChAT+) L1 motor neurons in the same groups as in A-C at P10. WT (N = 3 mice) and SMA+vehicle (N = 4) and SMA+C3 (N = 3) mice. Scale bar: 50μm. (F) Confocal images and (G) quantification of NMJ innervation (neurofilament and SV2+ are presynaptic markers while bungarotoxin is a postsynaptic marker). WT (N = 4 mice) and SMA+vehicle (N = 3) and SMA+C3 (N = 4) mice, ~200-300 NMJs per animal have been analyzed. Scale bar: 50μm. (H) Confocal images and (I) quantification of VGluT1+ proprioceptive synapses onto ChAT+ L1 motor neurons. Number of proprioceptive synapses on spinal motor neurons from WT (n=29 MNs from N=3 mice), SMA+vehicle (n=40 MNs from N=4 mice) and SMA+C3 (n=40 MNs from N=4 mice) mice. Scale bar: 20μm. (J) Confocal images and (K) quantification of Kv2.1 coverage of the cell membrane of motor neurons from WT (n=30 MNs from N=3 mice), SMA+vehicle (n=30 MNs from N=3 mice) and SMA+C3 (n=40 MNs from N=4 mice) mice. Scale bar: 20μm. Data represent means and SD. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test (A,B,C) or one-way ANOVA (E, G, K) or Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn Posthoc (I) # indicates p <0.05.

We also found that both M and H responses recorded from the TA muscle (innervated by the death-resistant L4-5 motor neurons) of C3-treated SMA mice at P10 were fully rescued (Fig. 3B-E). To investigate whether the beneficial effects of C3 treatment in sensory-motor circuits of SMA mice were maintained at later times, we examined the H-reflex in the flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscle of wild-type and C3-treated SMA mice (untreated SMNΔ7 mice die after 2 weeks23) following stimulation of the sciatic nerve in vivo and under general anesthesia at P30 (Fig. 3F). Motor neurons innervating FDB muscle are located in the L4-L6 spinal segments32, and this muscle was chosen for its reliability in obtaining H-reflexes in vivo and vulnerability in SMA mice.26 We found that SMA-treated mice exhibited nearly normal M and H responses as well as H/M ratio compared to age-matched WT controls (Fig. 3G-J), while there were no differences in their corresponding latencies (Suppl. Fig. 2E). Together, these findings reveal that the behavioral benefit of treatment with an SMN-inducing drug correlates with improved H-reflex and sensory-motor circuit function in SMA mice.

Spinal sensory-motor circuits controlling hindlimb muscles become dysfunctional at late disease stages in SMA mice

The reduction in the H-reflex from L4-L5 sensory-motor circuits comprising degeneration-resistant motor neurons such as those controlling the TA muscles in SMNΔ7 mice prompted us to investigate their functional status in greater detail. To do so, we employed a modified version of the ex vivo spinal cord preparation33 and recorded L4/L5 motor neuron responses from P10 WT and SMNΔ7 mice intracellularly, following suprathreshold proprioceptive sensory fiber stimulation (see Methods and Fig. 5A,B). We found reduced amplitude of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) in SMA motor neurons compared to their WT counterparts (Fig. 5C,D), with no change in their latency (Fig. 5E). Monosynaptically-mediated EPSPs were not correlated with changes in motor neuron input resistance (Fig. 5F). Similarly, there was no correlation between input resistance and the cross-section soma area for all recorded motor neurons (Fig. 5G). We also examined whether the reduction in the EPSP amplitude might reflect a reduction of the number of synapses impinging on motor neurons. However, we found no differences in the number of proprioceptive (VGluT1+) synapses on the soma of WT and SMA motor neurons (Fig. 5H,I) and only a minimal decrease on proximal dendrites (Suppl. Fig. 4A).

Figure 5. Proprioceptive neurotransmission is impaired in motor neurons innervating distal muscles at late stages of disease in SMA mice.

(A) Schematic of the modified ex vivo spinal cord preparation in which the ventral funiculus was removed to aid visual access for patch clamp recordings. (B) Confocal image of CTb-488 (in green) motor neurons in a spinal cord preparation (L4/5 spinal segment). A motor neuron is shown in magenta which was intracellularly recorded, filled with Neurobiotin and visualized post hoc. Scale bar: 20μm. (C) Excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) following supramaximal L5 dorsal root stimulation in WT and SMA mice at P10. Dotted vertical lines indicate the onset of the response and where the EPSP amplitude is measured (2.5ms after the onset). Scale bar: 5mV, 2ms. (D) Peak amplitude and (E) latency of EPSPs in WT (n = 11 motor neurons) and SMA (n = 9) motor neurons at P10. At least N=4 mice used per genotype. Relationship between input resistance and peak EPSP amplitude (F) as well as input resistance and motor neuron soma area (G) from WT (n = 9) and SMA (n = 8) motor neurons at P10. (H) Confocal images of L5 motor neurons (ChAT, green) and proprioceptive synapses (VGluT1, magenta) from WT and SMA mice at P10. Scale bar: 20μm. (I) Number of VGluT1+ proprioceptive synapses onto the soma of L5 motor neurons from WT (n = 40 MNs, N = 4 mice) and SMA (n = 30 MNs, N = 3 mice) mice at P10. (J) First (black) and second (magenta) EPSP responses elicited in motor neurons after 10Hz dorsal root stimulation in P10 WT and SMA mice. Arrowheads indicate stimulus artefact. Vertical dotted line marks peak EPSP amplitude measured at 2.5ms after the onset of response. Scale bar: 2mV, 2.5ms. (K) Percentage changes in EPSP amplitude following 10 stimuli at 10Hz normalized to the first response for WT (n = 10) and SMA (n = 9) motor neurons at P10. Data represent means and SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Mann-Whitney test for (C, I), unpaired t test for (B, G), and simple linear regression (D, E).

To test the possibility that glutamate release may be the cause for the reduction in synaptic transmission, we performed dorsal root stimulation at different frequencies and measured the EPSP amplitudes between subsequent trials. We found no significant difference between WT and SMA mice at 0.1Hz (Suppl. Fig. 4C), and a ~25% reduction at 1Hz in SMA motor neurons after several stimuli (Suppl. Fig. 4B,D). In contrast, at the more physiologically-relevant stimulation frequency of 10Hz, there was a strong reduction (~50%) of the EPSP amplitude in SMA mice compared to a smaller reduction (~13%) in WT mice as early as the 2nd stimulus (Fig. 5J,K). These results suggest that the ~50% reduction in synaptic transmission occurs via presynaptic mechanisms through impairment of glutamate release by proprioceptive synapses onto degeneration-resistant motor neurons at later stages of the disease.

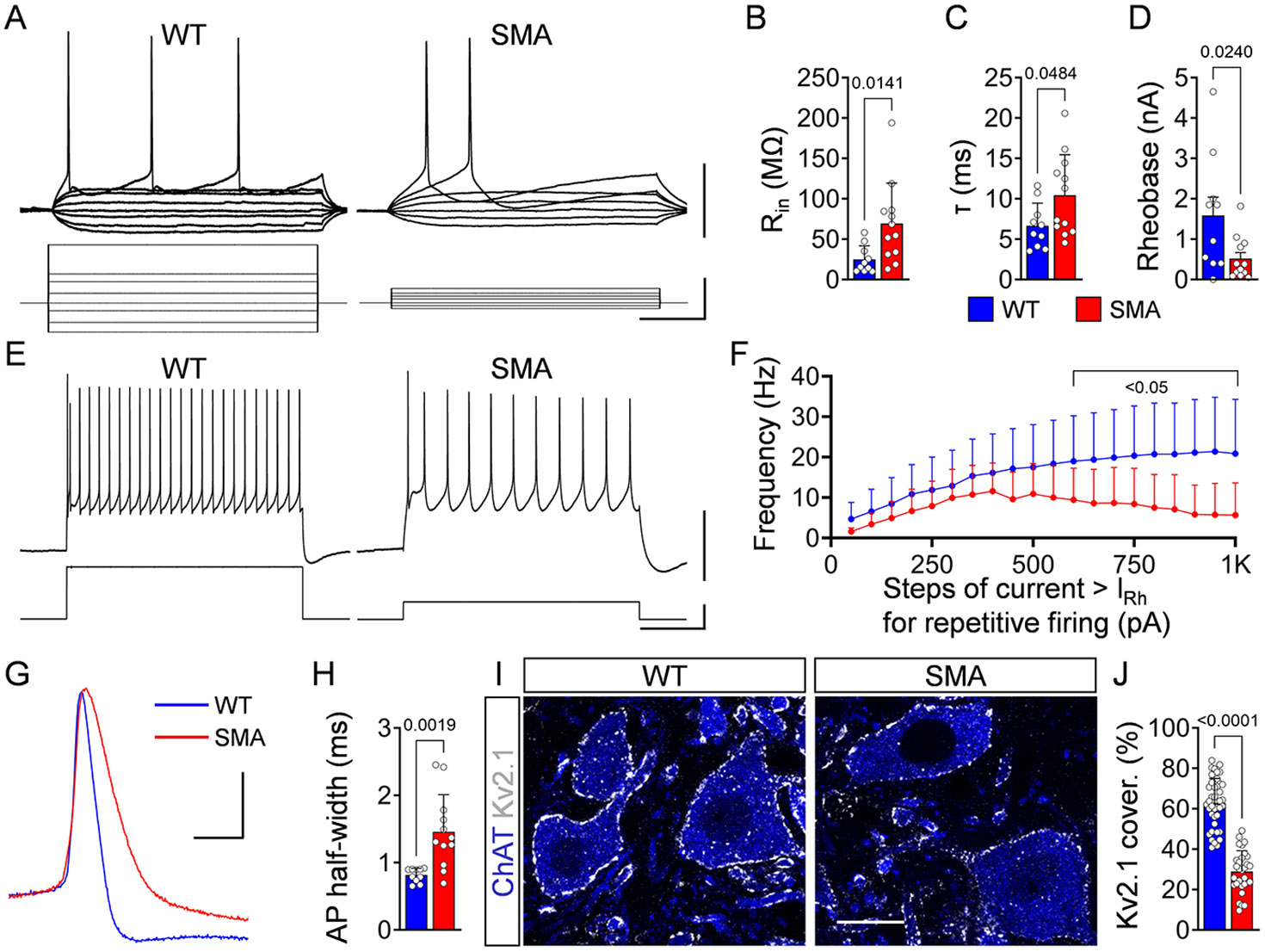

We have previously reported that dysfunction of proprioceptive synapses has profound effects on the output of vulnerable motor neurons in SMA mice.2 Therefore, we tested whether this applies to degeneration-resistant SMA motor neurons innervating the TA muscle through analysis of their intracellular properties at P10 in SMNΔ7 mice. We found no significant differences in resting membrane potential (Suppl. Fig. 5A). In contrast, the passive membrane properties of input resistance (Rin) and time constant (τ) revealed a significant increase in SMA neurons compared to controls (Fig. 6A-C). This increase was unlikely due to changes in soma size because the capacitance did not differ (Suppl. Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the rheobase was inversely and proportionally reduced in SMA motor neurons (Fig. 6A,D), pointing to changes in the distribution of ion channels at the cell membrane (specific membrane resistivity). Lastly, we examined the ability of TA motor neurons to fire repetitively by injecting steps of current and found that SMA motor neurons exhibited significantly lower maximum firing frequencies (Fig. 6E,F).

Figure 6. Motor neurons innervating distal muscles exhibit signs of dysfunction in symptomatic SMA mice.

(A) Membrane responses to current injections in a WT and SMA L5 motor neurons at P10. Scale bars: 20mV, 400pA, 100ms. (B) Input resistance, (C) Time constant and (D) Rheobase for WT (n = 10 motor neurons) and SMA (n = 12) motor neurons at P10. At least N=4 mice used per genotype. (E) Intracellular responses (top) showing repetitive firing at the maximum frequency attained during current injection (bottom) and (F) Frequency-to-current relationship for WT (n = 9) and SMA (n = 12) at P10. Scale bar: 40mV, 500pA, 200ms. (G) Superimposed action potentials during steady-state firing following current injection in a WT (blue) and SMA (red) motor neuron at P10. Scale bar: 20mV, 2ms. (H) Duration at half-width of action potentials for WT (n = 10) and SMA (n = 12) motor neurons. (I) Single-optical-plane confocal images of L5 motor neurons (ChAT, blue) expressing Kv2.1 channels (white) from P10 WT and SMA mice. Scale bar: 20μm. (J) Percentage somatic coverage of Kv2.1 expression in WT (n = 40 MNs, N = 4 mice) and SMA motor neurons (n = 30 MNs, N = 3 mice). Data represent means and SD. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t test for (B,C,J), Mann-Whitney test for (D, F) and Welch’s t test for (H).

A key molecular mechanism for the reduced firing ability of vulnerable SMA motor neurons is the reduction of Kv2.1 channel expression, a major contributor of the delayed rectification of motor neuron’s action potentials (AP).2 Therefore, we investigated several characteristics of the APs in WT and SMA motor neurons innervating the TA. We found no significant difference in the AP amplitude (Suppl. Fig. 5C), but a marked reduction in voltage threshold (Vthr) in SMA motor neurons compared to controls (Suppl. Fig. 5D). Importantly, the half-width of AP was significantly slower in the repolarizing phase in SMA motor neurons (Fig. 6G,H) and immunoreactivity against Kv2.1 channels revealed a significant >50% reduction in their coverage of soma membrane (Fig. 6I,J). These results indicate that even SMA motor neurons that are resistant to neuronal death become progressively dysfunctional during the course of the disease.

Proprioceptive synapses and Kv2.1 channels are reduced in motor neurons from SMA patients

While we observed dysfunction of proprioception and monosynaptic reflexes in humans with SMA, it is not known whether related pathogenic features such as loss of proprioceptive VGluT1+ synapses and reduced expression of Kv2.1 channels in spinal motor neurons that are found in mouse models also occur in humans with SMA. To address this, we investigated morphological signatures of sensory-motor circuit pathology in post-mortem spinal cords from Type 1 SMA patients and aged-matched controls (Table 4 in Supplemental Material and Methods).

First, we quantified the number of motor neurons, the loss of which is a hallmark of severe SMA in both humans and mice. Remarkably, we found that both α and γ motor neurons were significantly reduced in SMA spinal cords compared to controls (Fig. 7A-C). Despite limitations in tissue collection did not allow us to determine the identity of the specific spinal segments, the size of the surviving motor neurons in SMA patients was significantly smaller compared to controls (Fig. 7D). The finding that ~50% of the motor neurons survive until disease end stage and could be engaged in alleviating the severity of symptoms has important implications for SMA therapy.

Figure 7. Proprioceptive synapses and Kv2.1 channels are reduced in motor neurons from Type I SMA patients.

(A) Confocal image of α-motor neurons (MNs) (ChAT+, NeuN+) and γ-motor neurons (ChAT+, NeuN−) in a human control spinal cord. Scale bar: 50μm. Number of thoracic α-motor neurons (B) and γ-motor neurons (C) per spinal cord section in control (N = 4 subjects) and Type I SMA patients (N = 5 patients). (D) Perimeter of thoracic motor neuron soma in control (n = 30 MNs, N = 3 subjects) and Type I SMA spinal cords (n = 30 MNs, N = 3 patients). (E) Confocal images of motor neurons (ChAT; green) with proprioceptive synapses (VGluT1; magenta) from postmortem human spinal cord sections from a control and Type I SMA patient. Arrowheads point to proprioceptive synapses. Scale bar: 20μm. (F) Number of proprioceptive synapses on spinal motor neurons from control (n = 43 MNs, N = 4 subjects) and SMA type I patients (n = 55 MNs, N = 6 patients). (G) Inhibitory synapses (VGAT; magenta) on motor neurons (ChAT; green) from a control and SMA Type I patient. Scale bar: 20μm. (H) Number of inhibitory synapses on motor neurons from control (n = 30 MNs, N = 3 subjects) and SMA Type I patients (n = 30 MNs, N = 3 patients). (I) Number of C-boutons onto lumbar lateral motor neurons of control (n = 10 MNs, N = 1 subject) and Type I SMA patient (n =10 MNs, N = 1 patient). (J) Single-optical-plane confocal images of motor neurons (ChAT; blue) expressing Kv2.1 channels (white) from a control and SMA Type I patient. Scale bar: 20μm. (K) Percentage somatic coverage of Kv2.1 expression in control (n = 5 MNs, N = 2 subjects) and SMA Type I patients (n = 5 MNs, N = 2 patients) lumbar motor neurons. Data represent means and SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s t test for (B, C, F, I, K) and unpaired t test for (D, H).

Next, we quantified the number of VGluT1+ synapses on the soma of motor neurons. VGluT1 also marks corticospinal synapses34, 35 on human and non-human primate motor neurons36-40, but not rodent motor neurons.41-43 However, these corticomotoneuronal-VGluT1+ synapses develop late, at ~8-10 months after birth in non-human primates44 and a year after birth in humans.45, 46 Thus, the large majority of VGluT1+ synapses are considered of proprioceptive origin during early human development. Remarkably, we found a significant reduction in VGluT1+ synapses on motor neurons of Type 1 SMA patients compared to controls (Fig. 7E,F). Since only proprioceptive synapses are PV+, we also performed immunohistochemistry against parvalbumin (PV) together with VGluT1 and confirmed the significant reduction of VGluT1+/PV+ proprioceptive synapses on motor neurons between controls and SMA spinal cords (Suppl. Fig. 6C,D). The post-mortem interval (PMI) or age at the time of death did not play a significant role in this analysis (Suppl. Fig. 6A,B), and VGluT1 synaptic coverage was significantly reduced on both medially-located lumbar motor neurons (MMC) - which innervate axial muscles – and laterally-located motor neurons (LMC) - which innervate distal muscles (Suppl. Fig. 6E,F). Interestingly, we found that the number of cholinergic C-boutons on lumbar SMA motor neurons was also reduced (Fig. 7G,I), while the number of inhibitory synapses (marked by the vesicular transporter, VGAT) did not change between control subjects and SMA Type 1 patients (Fig. 7G,H). Lastly, we quantified the percentage coverage of Kv2.1 on the soma of motor neurons and found a significant ~60% reduction in SMA motor neurons (Fig. 7J,K).

Collectively, these findings indicate that key cellular and synaptic features of sensory-motor circuit pathology are conserved in severe mouse models and Type 1 SMA patients.

Discussion

This study reveals that impaired proprioceptive-mediated neurotransmission is a conserved pathogenic event that contributes to disease progression in both mouse models and patients affected by SMA. We show that the H-reflex is a reliable neurological test to assess the function of sensory-motor circuits in both animal models and ambulatory SMA patients. Moreover, through morphological analysis of post-mortem spinal cords from severe Type 1 SMA patients, we show that the ~50% of motor neurons that survive until disease end-stage exhibit widespread loss of sensory synapses and concomitant reduction in Kv2.1 channel expression. Importantly, the same defects occur in severe SMA mice and are responsible for reduced motor neuron firing that contributes to impaired muscle contraction. Lastly, we document that improved motor function upon treatment with SMN-inducing drugs such as nusinersen in SMA patients or the risdiplam-analogue C3 in SMA mice correlates with a strong increase in the H/M amplitude ratio. Thus, the H-reflex could be used as a reliable functional assay for monitoring both progression and therapeutic targeting of sensory-motor circuit pathology in SMA.

Our study provides a first-in-human demonstration that SMA patients exhibit compromised proprioception compared to healthy individuals. Our first indication that proprioception is impaired in humans with SMA comes from the conscious joint position sense experiments. This test is different from the H-reflex test in that conscious impairment in proprioception includes ascending pathway through dorsal column and various brain structures, from the cuneate and gracilis nuclei to the sensory cortex.47-49 It is currently unclear whether these brain pathways are affected in SMA patients and contribute to affect proprioception together with the dysfunction of sensory-motor synapses which we have uncovered with the H-reflex. Accordingly, we found that ambulatory SMA patients exhibited marked reductions in the H-reflex amplitude, which was more pronounced than that of the M-response. This finding indicates that central sensory synapses are more affected than NMJs, which is supported by the analysis of the H/M amplitude ratio. Our results may also help better explain the results of an earlier electromyographic study in which the absence of H-reflexes in patients suffering from Werdnig-Hoffmann disease was attributed to the severe muscle denervation and the reduction in the M-response.50 Together with our recent report of two cases of SMA with sensory involvement51, these results are well aligned with previous studies documenting dysfunction of proprioceptive synapses as a conserved disease feature in animal models.1, 2, 4, 20

What are the mechanisms of proprioceptive dysfunction in SMA patients? Key insights into this question initially came from studies in SMNΔ7 mice, which faithfully model severe forms of SMA. At the onset of disease, proprioceptive synapses release less glutamate at the physiological frequencies.2 These synapses are then gradually lost from their corresponding motor neurons, resulting in reduced expression of the potassium channel Kv2.1, as we report here in human SMA motor neurons. In turn, the reduction of Kv2.1 markedly affects the ability of motor neurons to fire repetitively2, and ultimately impairs muscle contraction. However, it is unknown whether this sequence of events applies to ambulatory Type 3 SMA patients. In the absence of reliable mouse models for milder forms of SMA, we sought to study degeneration-resistant motor neurons in the SMNΔ7 mice as a proxy for sensory-motor circuits that are less severely affected by SMN deficiency. We report here that, except for neuronal death, these motor neurons exhibit functional deficits akin to those found in vulnerable motor neurons but at later stages of disease. Thus, distinct SMA motor neurons become dysfunctional at different times during disease progression. These observations may help explain the slower, yet progressive motor decline in milder Type 3 SMA patients.52

Our analysis of post-mortem spinal cord preparations from Type 1 SMA patients provides direct evidence that proprioceptive synapses are lost from human motor neurons similar to mouse models.2, 4, 19, 25 In further agreement with mouse studies4, 21, the number of cholinergic synapses on the soma of motor neurons are also reduced in Type 1 SMA patients relative to controls. Proprioceptive and cholinergic synapses are key regulators of Kv2.1 channel’s expression in motor neurons.53 Strikingly, our study uncovered marked reduction of Kv2.1 channel expression in motor neurons from Type 1 SMA patients. Taken together, these findings provide strong evidence that the mechanisms of sensory-motor circuit pathology are conserved between mouse models and SMA patients.

What is the clinical significance of impaired proprioception in SMA? The test performed with the angular difference in detection of passive movement of the knee indicated that the proprioceptive impairment correlated with the HFMSE score and the length of disease in the three ambulatory Type 3 SMA participants. This implies that dysfunction in proprioception is progressive and can be quantified using the H-reflex. Furthermore, increased amplitudes of the H-reflex correlated with improved walking distance and reduced fatigability in all three SMA participants treated with nusinersen. Importantly, these observations parallel those from SMA mouse experiments in which improved motor function following treatment with an analogue of risdiplam was associated with an increase in H-reflex amplitude. While these are correlative observations, a causal link between proprioceptive dysfunction and disease pathogenesis was previously established in mouse model.2, 25 Moreover, a recent study provided proof of principle that ambulatory SMA patients regain previously lost muscle strength and increase endurance following epidural spinal cord stimulation of proprioceptive afferents.54

Current therapies for SMA patients include an antisense oligonucleotide (nusinersen)55, a splice-modifier molecule (risdiplam)28, 56, 57 and SMN replacement by gene therapy (onasemnogene abeparvovec)58, 59, all of which aim to increase SMN protein via different mechanisms. Although all three therapies have demonstrated clinical efficacy9, 60-64, it is widely accepted that none of these represent a cure65-69 leaving many treated patients with significant motor deficits.5, 70, 71 The response to current SMA therapies is variable and there is an increasing need for reliable measures of functional improvement to assess efficacy of treatment.66, 72

Here, we show that Type 3 SMA patients exhibited significant improvements in the distance walked and fatigability following ~12 months on nusinersen which were correlated with an increase in the H-reflex and H/M ratio, indicating that this test could capture functional improvement. Thus, pending further validation in a larger cohort of SMA patients, we propose that analysis of the H-reflex could be implemented in clinical settings to serve as a sensitive and reliable measure of sensory-motor circuit pathology in SMA. The H-reflex could monitor disease progression, assess efficacy of treatment, and identify potential deleterious effects of therapies.73 H-reflex tests can be performed in different muscles of both upper and lower limbs in humans 74 as in patients with diabetic disorders.75 Upper limb muscles can be used for Type 2 SMA patients who are wheelchair bound, and lower limb muscles in ambulatory Type 3 SMA patients as in our study.

In summary, we conclude that proprioceptive synaptic dysfunction is a conserved pathogenic event in humans and mouse models and propose that proprioceptive sensory neurotransmission should be targeted therapeutically in SMA.

Material and Methods

Study design

Sample size and rules for stopping data collection was determined by previous experience and preliminary data. All data was included if the experiment was technically sound (perfusion, tissue preparation, staining, recordings, imaging etc.). The endpoints for animals were selected by previous experiments and literature references. Each experiment was at least three times replicated with a few exceptions of human tissue due to availability limitations, as described below. The research objectives were to investigate proprioceptive dysfunction in SMA patients and autopsy tissue as well as in a severe SMA mouse model. Different measurements of patients/patient material were performed in the following institutions: [Proprioception tests – University of Pittsburgh (Table 2 in Supplemental Material), EMG studies – Columbia University (Table 3 in Supplemental Material), Immunohistochemistry – University of Leipzig (except Kv2.1 – Columbia University) Table 4 in Supplemental Material]. The mice were randomized to treatment group, and the investigators who assessed the behavioral, histological and electrophysiological outcomes were blinded to the treatment group.

Animal procedure

Breeding and experiments were performed in the animal facilities of Columbia University, New York, USA and Leipzig University, Germany according to National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Care and Use of Animals and approved by the Columbia Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) for Columbia University or European (Council Directive 86/609/EEC) and German (Tierschutzgesetz) guidelines for the welfare of experimental animals and the regional directorate (Landesdirektion) of Leipzig for Leipzig University.

Mice were housed in a 12h/12h light/dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. The original breeding pairs for SMNΔ7 (Smn+/−; SMN2+/+; SMNΔ7+/+) mice on FVB background were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (stock #005025). Primers for genotyping: SMNΔ7: forward sequence (5’ to 3’) = GATGATTCTGACATTTGGGATG, reverse sequences (5’ to 3’) = TGGCTTATCTGGAGTTTCACAA and GAGTAACAACCCGTCGGATTC (wild-type band: 325bp, mSmn ko: 411bp). Control animals were littermates of mutants as previously reported for the SMNΔ7 line = Smn+/+; SMN2+/+; SMNΔ7+/+ .23 C3 compound was dissolved in sterile DMSO and delivered daily via intraperitoneal injection at a concentration of 3mg/kg from P1 to P30.

Mice from all experimental groups were monitored daily, and the body weight measurements, as well as the righting time and posture time (performed three times and averaged), were recorded as described previously1. Mice with a 25% reduction of body weight and an inability to right were euthanized to comply with IACUC guidelines for the welfare of experimental animals. Righting time was defined as the time for the pup to turn over on all its four limbs after being placed on its back and maintain its posture for at least 3 seconds. Posture time was defined as the time for which the pup could keep its balance when positioned in its four limbs. The cut-off test time for both tests was 60s. Approximately equal proportions of mice of both sexes were used and aggregated data are presented since gender-specific differences were not found nor have they been previously reported to be affected in SMA.

Intracellular recordings utilizing a modified ex vivo ventral funiculus-ablated mouse spinal cord preparation

The intracellular recordings from motor neurons’ experiments were conducted as previously reported1, 29, 33 at P10. The pups were decapitated, eviscerated and the carcass placed in a chamber filled with cold (~4°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) to dissect and remove the spinal cord. The aCSF was continuously oxygenated (95%O2/5%CO2) and contained: 113mM NaCl, 3mM KCl, 1mM NaH2PO4.H20, 25mM NaHCO3, 11mM D-Glucose, 2mM CaCl2.H20, and 2mM MgSO4.7H20. After the dissection, the L2 – L6 spinal cord segment was glued with the dorsal side facing up and with intact dorsal roots onto an agar block (~5%) prepared with PBS and 1% FastGreen. An oblique cut (~45°) was performed at the L2 – L3 region, to visualize the central canal. The agar with the spinal cord was glued into a vibratome chamber (HM 650 V, Microm, Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK) filled with ice-cold (~4°C) oxygenated aCSF used for the removal of the ventral funiculus (to improve the access to motor neurons). This type of aCSF was different and contained: 130mM K-Gluconate, 15mM KCl, 0.05mM EGTA, 20mM HEPES, 25mM D-Glucose, 3 mM Na-kynurenic acid, 2mM Na-pyruvate, 3mM Myoinositol, 1mM Na-l-ascorbate and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The vibratome razor blade was aligned with the edge being at the midpoint between the lower end of the central canal and the start of the ventral commissure. The spinal cord was coronally sectioned in a slow pace (0.02 mm/s) to remove the ventral funiculus. The spinal cord was subsequently transferred into a beaker for incubation containing a different aCSF (used for the recording session) at 35°C for 30 minutes. This aCSF was identical to that in which the dissection was performed in and described above. After the 30-minute incubation, the spinal cord was transferred into the recording chamber and perfused with aCSF at room temperature (21 – 23 °C). The dorsal root of the L5 segment was placed into a suction electrode for stimulation.

Motor neurons were visually targeted for patching. At an earlier age (~P1), pups were anesthetized with isoflurane and the TA muscle was injected with ~1μl of CTb conjugated with a fluorochrome (CTb-488 or CTb-555). CTb+ labelled motor neurons were selected for recordings with an Eclipse FN1 Nikon microscope outfitted with a digital camera (Moment, Teledyne Photometrics). In some experiments, intracellularly recorded neurons were validated as motor neurons with post-hoc immunoreactivity with a ChAT antibody. In these experiments, Neurobiotin was added to the intracellular solution to label the recorded motor neuron post-hoc. Patch pipettes were prepared from borosilicate glass (GB200F-10, Science Products Hofheim am Taunus) with a Flaming-Brown puller (P97, Sutter Instruments, CA) to a resistance of ~3-6 MΩ. The electrodes were then filled with an intracellular solution containing: 150 mM K-D-Gluconate, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, 3 mM Mg-ATP, 0.3mM Na-GTP, 0.05 mM EGTA dissolved in purified water and adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH and osmolarity of 290–300 mOsm/kg H2O76. The recorded potentials (DC – 3kHz, Cyberamp, Molecular Devices) were fed to an A/D interface HEKA EPC10/2 amplifier (HEKA humac platform) and amplified with HEKA Patchmaster (HEKA Electronics) at a sampling rate of 10 kHz. In current clamp mode, the membrane passive properties of motor neurons were estimated following brief current injections (300 ms) at 20 pA current steps. Frequency-to-current plots were performed in current clamp mode by injecting long (1sec) current steps (50 pA) of increasing intensity. Excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) were recorded from motor neurons in response to a brief (0.2ms) orthodromic stimulation (A365, current stimulus isolator, WPI, Sarasota, FL) of the L5 dorsal root, while holding the cell at membrane potential of −70 mV. The dorsal root was stimulated at 0.1Hz, 1Hz or 10Hz for ten stimuli and the resulting monosynaptic response recorded and analyzed off-line. Data were analyzed offline using HEKA Patchmaster (HEKA Electronics). The monosynaptic component of the EPSP amplitude was measured from the onset of response to 2.5 ms. The latency was determined by measuring the time from the stimulation to the onset of response.

Immunohistochemistry on murine and human spinal cord and murine muscles

The detailed protocols used for immunohistochemistry in mouse tissues have been previously reported.4, 77 Briefly, mice were perfused with 1x PBS and 4% PFA following 4% PFA post-fixation overnight at 4°C. The following day, the spinal cords were removed and the lumbar L5 segments were identified by the ventral roots and briefly washed with PBS. Subsequently, single segments were embedded in warm 5% agar and serial transverse sections (75μm) were cut at the vibratome. The sections were blocked with 5% normal donkey serum in 0.01M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-T; pH 7.4) for 90 minutes and incubated overnight at room temperature in different combinations of the primary antibodies (Table 1: List of primary antibodies). VGluT1 antibodies were used as a marker for proprioceptive synapses, ChAT antibodies were used to label motor neurons. The following day, after 6 washes of 10 minutes with PBS, secondary antibody incubations were performed for 3 hours with the appropriate species-specific antiserum coupled to Alexa488, Cy3 or Alexa647 (Jackson labs) diluted at 1:1000 in PBS-T. After secondary antibody incubations, the sections were washed 6 times for 10 minutes in PBS, mounted on slides, and cover-slipped with an anti-fading solution made of Glycerol:PBS (3:7).29

For immunohistochemistry on post-mortem human tissue, some of the thoracic and lumbar segments of the spinal cord from patients with SMA and non-SMA controls were collected at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD: as controls: CNTL 12_04 (cause of death: unknown), CNTL 12_06 (Transverse myelitis; tissue collected and analyzed not affected by tr. myelitis), CNTL 13_01 (cardiac arrest), CNTL 17_01: (pneumonia); as SMA patients: SMA 10_01, SMA 14_04, SMA 14_05, SMA 17_04, SMA 19_01, SMA 21_01. The following patients were collected from Children’s National Hospital, George Washington University, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, in Washington, DC (IRB:15350): A-Wash and B-Wash (cardiac arrest) or at Columbia University in NY, NY: SMA CU1 and CU2 . Expedited autopsies were conducted under parental- or patient-informed consent in strict observance of the legal and institutional ethical regulations. Tissues from patients with SMA and age-matched controls with a short post-mortem interval were included. All patient and control tissues used in this study are listed in Table 4 (in Supplemental Material). The immunohistochemistry, scanning, and analysis for motor neuron counting and synaptic quantification have been performed at Leipzig University. Quantification of the Kv2.1 has been performed at Columbia University. Human spinal cord tissue was cryoprotected with a 15% sucrose solution for at least 2h until the tissue sank to the bottom of the tube. Afterwards, the tissue was transferred to a 30% sucrose solution and stored at 4°C overnight. The next day, the spinal cord tissue was embedded in Sakura Tissue Tek O.C.T. Compound and frozen in 2-Methylbutan cooled with liquid nitrogen. Two spinal cords (one SMA and one control) were flash frozen immediately upon removal from the patient and without fixation. Tissues were cut at a Leica CM3050 S cryostat into 20μm serial transverse sections at −20°C and subsequently stored at −80°C. Human spinal cord sections were incubated for 20min in Polyscience L.A.B. solution for antigen retrieval at room temperature. Afterwards they were washed 3x with PBS and blocked in 5 % normal donkey serum in 0.03% PBS-T for 90min. They were then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies (see Table 1) at 4°C overnight followed by 3x 10min washes with PBS and incubated for 3h with the appropriate secondary antibodies diluted 1:1000 in PBS-Triton. VGAT was used as a marker for inhibitory synapses and NeuN in combination with ChAT to identify α-MNs. After washing 3x 10 minutes with PBS the slides were cover-slipped with Glycerol: PBS (3:7) medium. In a few experiments, triplicates of analysis could not be performed due to over-fixation or reduced availability of human tissue.

For immunostaining of NMJs, mice were sacrificed or perfused and the muscle was dissected and immediately fixed with 4% PFA overnight. After fixation, single muscle fibers were teased and washed 3 times in PBS for 10 min each followed by staining of the postsynaptic part of the NMJ with a-bungarotoxin (BTX) Alexa Fluor 555 in PBS for 20 min. Subsequently, the muscle fibers were washed 5 times in PBS for 10 min and blocked with 5% donkey serum in 0.01 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-T) for 1 h. Mouse anti-Neurofilament (NF) and anti-Synaptic vesicle 2 (SV2) antibodies to immunolabel the presynaptic aspect of the NMJ were applied in blocking solution overnight at 4oC (Table 1). The muscle fibers were then washed 3 times for 10 min in PBS. Secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h in PBS-T at room temperature. Finally, the muscle fibers were washed 3 times in PBS for 10 min and mounted on slides covered with Glycerol:PBS (3:7) as previously described.4

Confocal microscopy and analysis

Detailed information are shown in the Supplemental Material.

H-reflex in neonatal and juvenile mice

Detailed information are shown in the Supplemental Material.

H-Reflex in SMA and control patients

Detailed information are shown in the Supplemental Material.

Proprioception test in control and Type 3 SMA participants

Detailed information are shown in the Supplemental Material.

6-minute-walk test (6MWT) distance and fatigability in SMA patients

Detailed information are shown in the Supplemental Material.

Western blot

Detailed information are shown in the Supplemental Material.

Statistics

Detailed information are shown in the Supplemental Material.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Acknowledgments

We thank the generous autopsy tissue donations from patients and their families and the financial support provided by the SMA Foundation. We also want to thank all SMA patients and healthy participants in the H-reflex investigations. We thank Dr. Michio Hirano for providing critical comments to our study and Dr. Marco Beato and Dr. Filipe Nascimento for providing guidance to establish the ventral funiculus-ablated ex vivo spinal cord preparation. We also want to thank Dr. Thomas Kaas for his help in exporting EMG traces.

Funding

This work is supported by R01-NS078375 (GZM), R01-NS125362 (GZM), R01-AA027079 (GZM), The SMA Foundation (GZM), Project ALS (GZM); German Research Foundation grants SI-1969/2-1 (CMS), SI-1969/3-1 (CMS), SMA-Europe (CMS), CMS was also the recipient of Young Investigator award by ROCHE; R01-NS102451 (LP), R01-NS114218 (LP), R01-NS116400 (LP); SMA Foundation (CJS), R35 NS122306 (NINDS to CJS); K12HD001399 (PK), American SIDS Institute (PK), Raynor Cerebellum Project (PK); K01-HD084690 (JM) and Cure SMA (CU18-2886; JM), Grant from F. Hoffmann–La Roche (MC).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary material. Raw data were generated at: Columbia University, Leipzig University, and University of Pittsburgh. Some of the data are not publicly available due to patient-related restrictions (containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants). Some of the derived data from mouse experiments that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Mentis GZ, et al. , Early functional impairment of sensory-motor connectivity in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neuron, 2011. 69(3): p. 453–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher EV, et al. , Reduced sensory synaptic excitation impairs motor neuron function via Kv2.1 in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Neurosci, 2017. 20(7): p. 905–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shorrock HK, Gillingwater TH, and Groen EJN, Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Sensory-Motor Circuit Dysfunction in SMA. Front Mol Neurosci, 2019. 12: p. 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buettner JM, et al. , Central synaptopathy is the most conserved feature of motor circuit pathology across spinal muscular atrophy mouse models. iScience, 2021. 24(11): p. 103376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercuri E., et al. , Spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2022. 8(1): p. 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lefebvre S., et al. , Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell, 1995. 80(1): p. 155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercuri E, Bertini E, and Iannaccone ST, Childhood spinal muscular atrophy: controversies and challenges. Lancet Neurol, 2012. 11(5): p. 443–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tizzano EF and Finkel RS, Spinal muscular atrophy: A changing phenotype beyond the clinical trials. Neuromuscul Disord, 2017. 27(10): p. 883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercuri E., et al. , Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 1: Recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord, 2018. 28(2): p. 103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pera MC, et al. , 6MWT can identify type 3 SMA patients with neuromuscular junction dysfunction. Neuromuscul Disord, 2017. 27(10): p. 879–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tisdale S and Pellizzoni L, Disease mechanisms and therapeutic approaches in spinal muscular atrophy. J Neurosci, 2015. 35(23): p. 8691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sumner CJ and Crawford TO, Two breakthrough gene-targeted treatments for spinal muscular atrophy: challenges remain. J Clin Invest, 2018. 128(8): p. 3219–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercuri E., et al. , Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med, 2018. 378(7): p. 625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erdos J and Wild C, Mid- and long-term (at least 12 months) follow-up of patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) treated with nusinersen, onasemnogene abeparvovec, risdiplam or combination therapies: A systematic review of real-world study data. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2022. 39: p. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendell JR, et al. , Single-Dose Gene-Replacement Therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med, 2017. 377(18): p. 1713–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brogna C., et al. , MRI patterns of muscle involvement in type 2 and 3 spinal muscular atrophy patients. J Neurol, 2020. 267(4): p. 898–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deymeer F., et al. , Segmental distribution of muscle weakness in SMA III: implications for deterioration in muscle strength with time. Neuromuscul Disord, 1997. 7(8): p. 521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon CM, et al. , A Stem Cell Model of the Motor Circuit Uncouples Motor Neuron Death from Hyperexcitability Induced by SMN Deficiency. Cell Rep, 2016. 16(5): p. 1416–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shorrock HK, et al. , UBA1/GARS-dependent pathways drive sensory-motor connectivity defects in spinal muscular atrophy. Brain, 2018. 141(10): p. 2878–2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imlach WL, et al. , SMN is required for sensory-motor circuit function in Drosophila. Cell, 2012. 151(2): p. 427–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerveró C., et al. , Glial Activation and Central Synapse Loss, but Not Motoneuron Degeneration, Are Prevented by the Sigma-1 Receptor Agonist PRE-084 in the Smn2B/- Mouse Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2018. 77(7): p. 577–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlini MJ, Triplett MK, and Pellizzoni L, Neuromuscular denervation and deafferentation but not motor neuron death are disease features in the Smn2B/- mouse model of SMA. PLoS One, 2022. 17(8): p. e0267990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le TT, et al. , SMNDelta7, the major product of the centromeric survival motor neuron (SMN2) gene, extends survival in mice with spinal muscular atrophy and associates with full-length SMN. Hum Mol Genet, 2005. 14(6): p. 845–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lotti F., et al. , An SMN-dependent U12 splicing event essential for motor circuit function. Cell, 2012. 151(2): p. 440–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon CM, et al. , Stasimon Contributes to the Loss of Sensory Synapses and Motor Neuron Death in a Mouse Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Cell Rep, 2019. 29(12): p. 3885–3901.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling KK, et al. , Severe neuromuscular denervation of clinically relevant muscles in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet, 2012. 21(1): p. 185–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong L., et al. , Impaired prenatal motor axon development necessitates early therapeutic intervention in severe SMA. Sci Transl Med, 2021. 13(578). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naryshkin NA, et al. , Motor neuron disease. SMN2 splicing modifiers improve motor function and longevity in mice with spinal muscular atrophy. Science, 2014. 345(6197): p. 688–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon CM, et al. , Converging Mechanisms of p53 Activation Drive Motor Neuron Degeneration in Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Cell Rep, 2017. 21(13): p. 3767–3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Alstyne M., et al. , Dysregulation of Mdm2 and Mdm4 alternative splicing underlies motor neuron death in spinal muscular atrophy. Genes Dev, 2018. 32(15-16): p. 1045–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao X., et al. , Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of a small-molecule SMN2 splicing modifier in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet, 2016. 25(10): p. 1885–1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bácskai T., et al. , Musculotopic organization of the motor neurons supplying the mouse hindlimb muscles: a quantitative study using Fluoro-Gold retrograde tracing. Brain Struct Funct, 2014. 219(1): p. 303–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Özyurt MG, et al. , In vitro longitudinal lumbar spinal cord preparations to study sensory and recurrent motor microcircuits of juvenile mice. J Neurophysiol, 2022. 128(3): p. 711–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persson S., et al. , Distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 in the rat spinal cord, with a note on the spinocervical tract. J Comp Neurol, 2006. 497(5): p. 683–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lodato S., et al. , Gene co-regulation by Fezf2 selects neurotransmitter identity and connectivity of corticospinal neurons. Nat Neurosci, 2014. 17(8): p. 1046–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemon RN, Descending pathways in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci, 2008. 31: p. 195–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer E and Ashby P, Corticospinal projections to upper limb motoneurones in humans. J Physiol, 1992. 448: p. 397–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baldissera F and Cavallari P, Short-latency subliminal effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on forearm motoneurones. Exp Brain Res, 1993. 96(3): p. 513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Noordhout AM, et al. , Corticomotoneuronal synaptic connections in normal man: an electrophysiological study. Brain, 1999. 122 ( Pt 7): p. 1327–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jo HJ, et al. , Multisite Hebbian Plasticity Restores Function in Humans with Spinal Cord Injury. Ann Neurol, 2023. 93(6): p. 1198–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang HW and Lemon RN, An electron microscopic examination of the corticospinal projection to the cervical spinal cord in the rat: lack of evidence for cortico-motoneuronal synapses. Exp Brain Res, 2003. 149(4): p. 458–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu Z., et al. , Control of species-dependent cortico-motoneuronal connections underlying manual dexterity. Science, 2017. 357(6349): p. 400–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alstermark B, Ogawa J, and Isa T, Lack of monosynaptic corticomotoneuronal EPSPs in rats: disynaptic EPSPs mediated via reticulospinal neurons and polysynaptic EPSPs via segmental interneurons. J Neurophysiol, 2004. 91(4): p. 1832–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawrence DG and Hopkins DA, The development of motor control in the rhesus monkey: evidence concerning the role of corticomotoneuronal connections. Brain, 1976. 99(2): p. 235–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lundberg A., Gross and fine motor performance in healthy Swedish children aged fifteen and eighteen months. Neuropadiatrie, 1979. 10(1): p. 35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matijević V., et al. , The most common deviations in the development of hand motoricity in children from birth to one year of age. Acta Clin Croat, 2013. 52(3): p. 295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salles JI, et al. , Electrophysiological analysis of the perception of passive movement. Neurosci Lett, 2011. 501(2): p. 61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dykes RW, et al. , Submodality segregation and receptive-field sequences in cuneate, gracile, and external cuneate nuclei of the cat. J Neurophysiol, 1982. 47(3): p. 389–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nyberg G and Blomqvist A, The termination of forelimb nerves in the feline cuneate nucleus demonstrated by the transganglionic transport method. Brain Res, 1982. 248(2): p. 209–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renault F., et al. , [Electromyographic study of 50 cases of Werdnig-Hoffmann disease]. Rev Electroencephalogr Neurophysiol Clin, 1983. 13(3): p. 301–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oskoui M., et al. , Transient hyperreflexia: An early diagnostic clue in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin Pract, 2020. 10(6): p. e66–e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salort-Campana E and Quijano-Roy S, Clinical features of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 3 (Kugelberg-Welander disease). Arch Pediatr, 2020. 27(7s): p. 7s23–7s28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deardorff AS, Romer SH, and Fyffe REW, Location, location, location: the organization and roles of potassium channels in mammalian motoneurons. J Physiol, 2021. 599(5): p. 1391–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prat-Ortega G E. S; Donadio S; Borda L; Boos A; Yadav Y; Verma N; Ho J; Frazier-Kim S; Fields DP; Fisher LE; Weber DJ; Duong T; Weinstein S; Eliasson M; Montes J; Chen KS; Clemens P; Gerszten P; Mentis GZ; Pirondini E; Friedlander RM; Capogrosso M, TARGETED STIMULATION OF THE SENSORY AFFERENTS IMPROVES MOTONEURON FUNCTION IN HUMANS WITH A DEGENERATIVE MOTONEURON DISEASE. medRxiv, 2024. 10.1101/2024.02.14.24302709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood MJA, Talbot K, and Bowerman M, Spinal muscular atrophy: antisense oligonucleotide therapy opens the door to an integrated therapeutic landscape. Hum Mol Genet, 2017. 26(R2): p. R151–r159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hua Y., et al. , Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature, 2011. 478(7367): p. 123–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palacino J., et al. , SMN2 splice modulators enhance U1-pre-mRNA association and rescue SMA mice. Nat Chem Biol, 2015. 11(7): p. 511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kotulska K, Fattal-Valevski A, and Haberlova J, Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 9 Gene Therapy in Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Front Neurol, 2021. 12: p. 726468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Passini MA, et al. , CNS-targeted gene therapy improves survival and motor function in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J Clin Invest, 2010. 120(4): p. 1253–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Finkel RS, et al. , Treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen: final report of a phase 2, open-label, multicentre, dose-escalation study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2021. 5(7): p. 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Finkel RS, et al. , Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 2: Pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord, 2018. 28(3): p. 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mendell JR, et al. , Five-Year Extension Results of the Phase 1 START Trial of Onasemnogene Abeparvovec in Spinal Muscular Atrophy. JAMA Neurol, 2021. 78(7): p. 834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aslesh T and Yokota T, Restoring SMN Expression: An Overview of the Therapeutic Developments for the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Cells, 2022. 11(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Vivo DC, et al. , Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: Interim efficacy and safety results from the Phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul Disord, 2019. 29(11): p. 842–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wirth B., Spinal Muscular Atrophy: In the Challenge Lies a Solution. Trends Neurosci, 2021. 44(4): p. 306–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reilly A, Chehade L, and Kothary R, Curing SMA: Are we there yet? Gene Ther, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mercuri E., et al. , Spinal muscular atrophy - insights and challenges in the treatment era. Nat Rev Neurol, 2020. 16(12): p. 706–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strauss KA, et al. , Onasemnogene abeparvovec for presymptomatic infants with two copies of SMN2 at risk for spinal muscular atrophy type 1: the Phase III SPR1NT trial. Nat Med, 2022: p. 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Strauss KA, et al. , Onasemnogene abeparvovec for presymptomatic infants with three copies of SMN2 at risk for spinal muscular atrophy: the Phase III SPR1NT trial. Nat Med, 2022. 28(7): p. 1390–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Day JW, et al. , Advances and limitations for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. BMC Pediatr, 2022. 22(1): p. 632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nicolau S., et al. , Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Semin Pediatr Neurol, 2021. 37: p. 100878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oskoui M., et al. , Two-year efficacy and safety of risdiplam in patients with type 2 or non-ambulant type 3 spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). J Neurol, 2023. 270(5): p. 2531–2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Alstyne M., et al. , Gain of toxic function by long-term AAV9-mediated SMN overexpression in the sensorimotor circuit. Nat Neurosci, 2021. 24(7): p. 930–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zehr EP, Considerations for use of the Hoffmann reflex in exercise studies. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2002. 86(6): p. 455–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kababie-Ameo R, Gutiérrez-Salmeán G, and Cuellar CA, Evidence of impaired H-reflex and H-reflex rate-dependent depression in diabetes, prediabetes and obesity: a mini-review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2023. 14: p. 1206552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bornschein G, Brachtendorf S, and Schmidt H, Developmental Increase of Neocortical Presynaptic Efficacy via Maturation of Vesicle Replenishment. Front Synaptic Neurosci, 2019. 11: p. 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Buettner JM, et al. , Laser microscopy acquisition and analysis of premotor synapses in the murine spinal cord. STAR Protoc, 2022. 3(1): p. 101236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary material. Raw data were generated at: Columbia University, Leipzig University, and University of Pittsburgh. Some of the data are not publicly available due to patient-related restrictions (containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants). Some of the derived data from mouse experiments that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.