Summary

In metastasis, the dynamics of tumor-immune interactions during micrometastasis remain unclear. Identifying the vulnerabilities of micrometastases before outbreaking into macrometastases can reveal therapeutic opportunities for metastasis. Here, we report a function of T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM3) in tumor cells during micrometastasis using breast cancer (BC) metastasis mouse models. TIM3 is highly upregulated in micrometastases, promoting survival, stemness, and immune escape. TIM3+ tumor cells are specifically selected during early seeding of micrometastasis. Mechanistically, TIM3 increases β-catenin/interleukin-1β (IL-1β) signaling, leading to stemness and immune-evasion by inducing immunosuppressive γδ T cells and reducing CD8 T cells during micrometastasis. Clinical data confirm increased TIM3+ tumor cells in BC metastasis and TIM3+ tumor cells as a biomarker of poor outcome in BC patients. (Neo)adjuvant TIM3 blockade reduces the metastatic seeding and incidence in preclinical models. These findings unveil a specific mechanism of micrometastasis immune-evasion and the potential use of TIM3 blockade for subclinical metastasis.

Keywords: micrometastasis, cancer immunoediting, metastasis, breast cancer, TIM3, immune-evasion, EMT, stemness, γδ T cells, TIM3 blockade

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Immune pressure at distant organs selects TIM3+ tumor cells during micrometastasis

-

•

TIM3+ tumor cells exhibit stemness, EMT, and immune-evasive features

-

•

TIM3 in tumor cells is a biomarker of relapse and poor prognosis in BC patients

-

•

(Neo)adjuvant TIM3 blockade prevents metastatic seeding and metastasis initiation

Rozalén et al. report that TIM3 in breast cancer drives a specific mechanism of immune escape during micrometastasis. TIM3+ tumor cells exhibit stemness/EMT features and promote immune-evasion by inducing immunosuppressive γδ T cells. TIM3 is a biomarker of poor outcome, and its blockade targets metastasis initiating cells during micrometastasis.

Introduction

Metastatic breast cancer is not curable with current therapies and accounts for nearly 700,000 deaths every year.1 Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapeutic strategies aim to prevent and/or eradicate micrometastatic disease and hence progression to overt metastatic disease. However, micrometastasis immunity is poorly understood due to preclinical and clinical challenges. In order to improve these strategies, we need a comprehensive understanding of the biology of small early micrometastasis and their tumor microenvironment.

During metastasis, most of the disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) fail to adapt to distant tissue conditions upon arrival and die, resulting in a selection of the fittest cells. Among these hurdles, the immune system’s anti-tumor activity is one of the main barriers for metastatic colonization.2,3 Then, metastasis-initiating cells (MICs) are a selection of few tumor cells with distinctive properties enabling the seeding and growth in distant sites.4,5 Tumor phenotypes considered highly metastatic or MICs, such as cancer stem cell (CSC) and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like phenotypes,4,5 have also been described as immune-evasive in other studies.6,7,8,9 The immune landscape of distant organs impose immune pressure on tumor cells engaging a process of tumor-immune coevolution and selection of immune-evasive tumor cells, in a process called cancer immunoediting.10 Functional and genomic studies have reported the existence of immunoediting during metastasis in humans and experimental mouse models.11,12,13 Moreover, different organs display different immune requisites and pressures. For instance the liver metastasis immunity is of major interest due to its tolerogenic immune cell populations, which make these metastases more resistant to immunotherapy than other organs.14 Yet, the tumor phenotype dynamics overcoming the immune pressure require further investigation during micrometastasis.

TIM3 (T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3), also known as HAVCR2, is a cellular receptor typically expressed in immune cells where it functions as an immune checkpoint receptor. In particular, it is expressed in interferon gamma (IFN-γ) activated T cells and is important in T cell dysfunction in cancer15. Therefore, TIM3 blockade has been proposed as an immune-checkpoint inhibitor (ICI), and there are ongoing clinical trials in advanced metastatic disease for acute myeloid leukemia (AML),16 lung cancer,17 and melanoma.18 However, TIM3 expression is not only restricted to immune cells, and recent studies have reported TIM3 expression in normal epithelial cells and tumor cells,19 including leukemia stem cells20 and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG)21 triggering AKT and β-catenin signaling. Importantly, the biology of TIM3 and its potential therapeutic effects on metastatic tumor cells have not been explored, nor has its use in time-tailored therapies to block metastasis initiation. Here, we show how TIM3 expression in breast cancer cells is a biomarker of poor outcome and high-risk of relapse in breast cancer (BC) patients and plays a unique role in MICs specific of micrometastasis, including survival, stemness, and immune-evasion.

Results

Modeling experimental metastasis immunoediting

To measure the immune pressure executed on tumor cells during metastatic colonization at distant organs, we conducted comparative experimental metastasis in (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) NOD scid gamma (NSG) immunodeficient (ID) and Balb/c immunocompetent (IC) mice. We used EpRas breast tumor-transformed mouse cells, which have never been previously immunoedited as they are not derived from tumor tissues in vivo,22 and are an established model of breast cancer metastasis.23,24,25 First, EpRas-FLuc-GFP cells were selected with low-GFP expression (Figure S1A) to avoid immunogenicity as previously suggested,26 and transplanted with low cell number via intracardiac injection (i.c.) for systemic delivery in ID and IC mice, monitored by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) (Figures 1A and S1B). As expected, the metastatic growth was reduced in IC mice compared to ID mice indicating the selective effect of the host immune system (Figure S1B). Twenty days after injection, lung, liver, and brain metastasis were dissected, detected by BLI ex vivo (Figure S1C) and tumor cells were isolated by flow cytometry based on GFP. Next, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of ID and IC-derived metastatic tumor cells revealed differences in the transcriptomic profiles based on the immunoediting selection suffered in IC hosts. RNA-seq data validated the specificity of the tumor cell isolation methodology since no immune-exclusive genes were detected, such as Cd45 (Figure S1D). Principal-component analysis (PCA) and unsupervised hierarchical clustering showed how the transcriptomic profiles of metastases from IC hosts were differentially clustered from ID hosts (Figures 1B and 1C). The IC and ID-derived metastasis samples clustered independently of the metastatic site, indicating that the immune pressure is a dominant selective factor of tumor cell traits during metastasis (Figures 1B and 1C).

Figure 1.

Metastasis immune pressure positively selects TIM3+ metastatic cells

(A) Experimental design using immunocompetent (IC) Balb/c mice and immunodeficient (ID) NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice for the assessment of metastatic immune pressure.

(B) Principal-component analysis (PCA) of the RNA-seq from EpRas cells isolated from three organ (lung, liver, and brain) metastatic samples in IC and ID hosts.

(C) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering from lung, liver and brain metastasis (Z score) in ID and IC hosts (n = 3 IC and n = 3 ID independent biological replicates).

(D) Gene ontology enrichment analysis of top 50 upregulated genes in all organs from IC mice.

(E) GSEA of indicated gene lists with the ranked gene expression list of IC vs. ID in all organ samples.

(F) Volcano plot of gene expression in all organs comparing IC and ID mice samples (n = 3 independent biological replicates).

(G) Dot plot representing TIM3 expression of human breast cancer cell lines from the CCLE. Primary tumor-derived cells (gray) and metastasis-derived cells (pink).

(H) Dot plot representing TIM3 protein levels measured by flow cytometry of mouse breast cancer cell lines with metastatic potential in experimental models. Color code as (G).

(I) TIM3 immunofluorescence of liver tissue metastasis derived from 4T07 intracardiac injection in ID and IC mice. Representative image of TIM3 immunofluorescence. Scale bars, 100 μm. Dashed line delineates metastasis tissue. Boxplot quantification of TIM3 staining mean fluorescent intensity in from 5 independent mice (n = 5 independent biological replicates). Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by unpaired Student’s t test.

Looking for commonalities in the 3 metastatic organs (brain, lung, and liver) IC vs. ID, gene ontology (GO) analysis showed that IC-derived metastatic cells were enriched in pathways related to negative immune system regulation (GO:002683) (Figures 1D, S1E, and S1F), validating our experimental design to measure metastatic immune pressure. IC-derived metastasis showed enrichment in stem cell-like pathways including LIM_mammary stem cells27 and the hallmarks of EMT (MSigDB-M5930) datasets by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)28 (Figure 1E). These results suggested that immunoedited metastatic cells are enriched in immune-evasive and EMT stem cell-like properties, which are aligned with computational studies associating stemness and immune-evasion in clinical metastasis.29,30 Among the upregulated genes in immunoedited metastases, we focused on potential druggable targets. Strikingly, we found high levels of Tim3 expression in tumor cells in all organs (Figure 1F and Table S1), particularly in liver metastasis (Figure S1G). This was unexpected since TIM3 is a T cell immunoglobulin mucin family member typically expressed in immune cells31 and functioning as an immune-checkpoint receptor in lymphocytes.32 Its role in epithelial cells has been underestimated and only recently few reports have started to explore it.19,21

Using the cancer cell line encyclopedia (CCLE), we checked that human breast cancer cells indeed express TIM3 with high variability across different cell lines (Figure 1G). To choose the best syngeneic BC metastasis models to interrogate TIM3 functions in vivo, we analyzed TIM3 protein levels by flow cytometry in mouse BC cells (Figure 1H). Similarly, mouse BC cells express TIM3, and detected the highest levels of TIM3 in 66cl4, 4T07, and 4T1 cells (Figure 1H), which are triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) metastasis models. We selected 4T07 with high TIM3 levels to perturb TIM3 in functional experimental metastasis in vivo. 4T07 cells cause multi-organ metastasis when injected i.c.33 Similar to EpRas, the i.c. injection of 4T07-FLuc-GFP cells in IC and ID hosts showed less metastases in IC conditions as expected due to immune pressure (Figure S1H), and thus increased levels of TIM3 in IC hosts (Figures 1I and S1I). Luciferase tissue staining validated the faithful monitoring of metastasis by BLI (Figure S1J).

TIM3 promotes metastatic ability under immune pressure

In order to study the relevance of TIM3 during metastasis, we tested the metastatic ability of TIM3 gain- and loss-of-function in different mouse strains using 4T07, 4T1, and AT3 tumor cells, with Balb/c and C57BL/6 origin, respectively, with different immunity.34,35 The efficiency of KD and the overexpression (OE) of TIM3 in 4T07 was validated (Figure S2A). Systemic administration by intracardiac injection of 4T07-Fluc-GFP Tim3-KD (shRNA-86) cells significantly reduced their metastatic ability increasing the overall survival only in IC Balb/c hosts (Figures 2A and S2B). However, no significant KD effects were observed in ID hosts (Figures 2A and S2B), suggesting that TIM3 confers functional advantages in metastasis by overcoming immunosurveillance. The metastatic growth was reduced in all the organs, especially in the liver (Figure 2B). Additional experiments showed consistent reduced metastasis in Tim3-KD in IC hosts (Figure 2C) and also using multiple shRNAs (Figure S2C). In order to study the interference of the immunogenic GFP-Luc of our cell lines, we performed experiments with unlabeled 4T07-Tim3-KD cells which also reduced metastasis and increased mice survival compared to control cells (Figures 2D, 2E, and S2D). Consistently, AT3-Tim3-KD cells i.c. injected in IC C57BL/6 mice also showed extended survival than control cells, only in IC hosts (Figure S2E). Instead, 4T07-Tim3-OE showed increased metastasis and impaired survival compared to control mice (Figures S2F–S2H). Overall, these results demonstrate a selective immune-evasive pro-metastatic advantage of TIM3 in tumor cells.

Figure 2.

TIM3 drives breast cancer metastasis

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival plot after intracardiac injection of 4T07 control cells versus Tim3-KD cells in ID (NSG) and IC (Balb/c) mice with the indicated conditions. Statistical analysis using Log rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

(B) Relative photon flux BLI quantification of metastatic organs at day 16 after i.c. injection of 4T07 Ctrl and Tim3-KD cells. Data represents mean + SEM; dots represent independent biological replicates.

(C) Relative photon flux BLI quantification of whole-body metastasis of 4T07 Ctrl and Tim3-KD in IC mice. Data represents mean + SEM. n = 22 independent biological replicates.

(D) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of metastatic livers from unlabeled 4T07-Ctrl and -Tim3-KD cells. Arrows indicate metastatic lesions.

(E) Quantification of micro- and macro-metastatic lesions from (D).

(F) Mammary fat pad (MFP) injection of 4T1-Ctrl and -Tim3-KD cells in Balb/c mice. Data represents tumor growth by mean + SEM of n = 16 independent biological replicates.

(G) Incidence of spontaneous metastasis at day 40 after primary tumor resection (day 20) of 4T1-Crtl and 4T1-Tim3-KD MFP injected mice. Individual BLI images from upper body. n = 8 Ctrl and n = 6 KD mice followed after resection. Statistical significance; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by Chi-square test.

(H) Representative immunofluorescence of breast tumor cell marker Mamaglobulin-1 (MGB1) in red and TIM3 in green in human breast cancer tissue. Scale bars, 30 μm. Representative immunohistochemistry image of TIM3 showing tumor-epithelial cell staining. Dash line delineates the tumor areas. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(I) Percentage of tumor TIM3-positive samples from primary (P) and metastatic (M) matched clinical samples (ConvertHER cohort). TIM3 score percentage in primary and paired-metastatic samples (right panel). n = 75 for each condition P and M.

Data represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by two-tailed Student’s t test in (B), (C), (E), and (I).

Also see Figure S2.

Next, we used spontaneous experimental metastasis models by transplanting 4T1 metastatic cells into the mammary fat pad (MFP) followed by primary tumor resection upon 8 × 8 mm size and allow time to develop metastases. Interestingly, TIM3 did not affect the primary tumor growth; however, metastasis incidence in lung and liver organs was reduced by knocking-down Tim3 in 4T1 cells (Figures 2F and 2G). Primary tumor proliferation was not affected by Tim3-KD in 4T07 cells either (Figures S2I and S2J). These data indicate that TIM3 leads a prominent functional role specific of metastasis.

TIM3 is upregulated in metastatic clinical samples

TIM3 expression was confirmed to be expressed in tumor cells by co-localization with mammaglobin (MGB1), a marker of breast cancer epithelial cells,36 detected by immunofluorescence (IF), and by IHC TIM3 staining of 75 patients samples with primary-metastasis matched tissues from the ConvertHER cohort37 (NCT01377363) (Figure 2H). TIM3 positivity in tumor cells was increased in metastasis compared to primary-matched tumors and also the TIM3 tumor cell scoring (Figure 2I). TIM3 was also higher in metastatic samples in stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (sTILs), intratumoral-infiltrating lymphocytes (iTILs), and a trend in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (Figure S2K). These results confirmed the striking TIM3 expression in tumor cells in breast cancer patient samples of all subtypes and the TIM3 upregulation in metastatic clinical disease.

TIM3 is associated to EMT-like cells and triggers β-catenin signaling

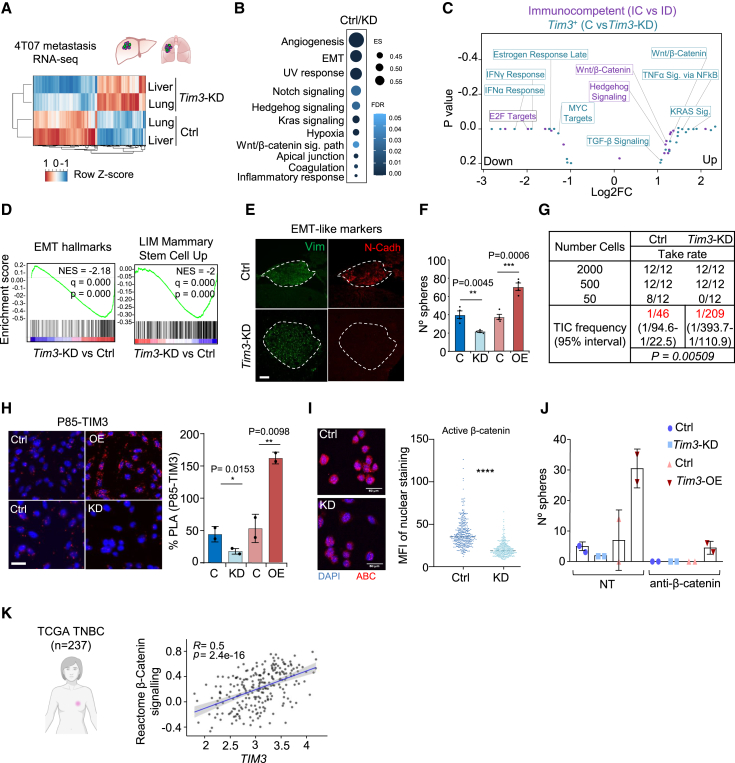

To understand the mechanistic actions of TIM3 in BC metastasis, we performed RNA-seq of Tim3-KD and control 4T07 tumor cells isolated from metastasis after 2 weeks of i.c. injection. Transcriptomic profiles of lung and liver metastasis samples clustered according to Tim3 status and not by colonized organs (Figures 3A and S3A). GSEA revealed EMT, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and other stemness related pathways enriched in Tim3-positive metastatic tumors (Figure 3B). CellMarker38 confirmed the enrichment of mesenchymal-like and stem cell-like pathways (Figure S3B). These results are aligned with the biology of MICs5,39 and the metastasis immunoediting experiments (Figure 1E). Wnt/β-catenin signaling was enriched in TIM3+ (Ctrl) vs. Tim3-KD datasets and in IC vs. ID (Figure 3C). TIM3+ (control) vs. Tim3-KD cells were enriched in EMT hallmarks and LIM Mammary stem cells27 genesets (Figure 3D). In addition, several β-catenin targets were upregulated (Figure S3C), related with β-catenin-mediated immunosuppression and stemness.40,41 Altogether, these observations suggest a pivotal role of TIM3 driving tumor immune-evasive stem cell-like phenotypes.

Figure 3.

TIM3+ MICs display Stemness/EMT-like features and β-catenin activation

(A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering heatmap of the indicated conditions from 4T07 metastases RNA-seq analysis (n = 2 independent biological replicates).

(B) GSEA from (A) experiment comparing Ctrl and Tim3-KD (n = 2 independent biological replicates).

(C) Gene ontology integration of the metastasis immunoediting RNA-seq from Figure 1A and the Tim3-KD metastasis RNA-seq (A).

(D) GSEA ranked list Ctrl and Tim3-KD 4T07 tumors (lung and liver metastases) interrogated with the indicated EMT-like and stem-like gene signatures.

(E) Tissue immunofluorescence representative image: for N-cadherin (red) and vimentin (green) in Ctrl and Tim3-KD metastatic livers. Dash line delineates the metastatic tissue. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(F) Tumorsphere quantification at day 5 after seeding 500 4T07 cells of indicated conditions (n = 3 independent biological replicates). Data represented as mean ± SEM.

(G) MFP injection and limiting dilution assay (LDA) of 4T07 Ctrl and Tim3-KD cells. Table represents serial dilution injections and tumor take rate. Tumor-initiating cell (TIC) frequency calculated by ELDA software shown in red. p value by Pearson’s Chi-squared two-tailed test.

(H) Proximity ligation assay showing the interaction (red dots) of P85 and TIM3 in 4T07 Ctrl and Tim3-KD cells. Quantification of the interactions per area. Data represented as mean ± SEM.

(I) Immunofluorescence of active β-catenin (ABC) in 4T07-Ctrl and Tim3-KD cells. Quantification of the nuclear staining of ABC.

(J) Tumorsphere quantification of 4T07 Control, Tim3-KD, and Tim3-overexpression upon 20 μM dose of β-catenin inhibitor.

(K) Rho correlation of TIM3 mRNA levels and the Reactome β-Catenin signaling signature in 237 TNBC patients TCGA. R2 and p value are shown. Statistical significance; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by two-tailed Student’s t test in (F) and (H); unpaired Student’s t test in (I).

Also see Figure S3.

Tissue immunofluorescence in TIM3+ (control) and Tim3-KD 4T07 cells metastasis samples showed high levels of N-cadherin, vimentin, and low E-cadherin (Figures 3E and S3D), which are classic EMT markers. Tim3 levels were found consistently upregulated during EMT induction using public datasets (Figure S3E). In addition, in vitro functional assays for stem cell-like properties showed increased tumorsphere formation according to TIM3 levels in 4T07 cells: Tim3-OE > control >Tim3-KD (Figure 3F). To assess the tumor initiating capacity (TIC) as a typical measure of tumorigenicity and stemness, limiting dilution assay (LDA)-MFP injection of 4T07 cells in immunodeficient mice showed reduction of TIC frequency when Tim3 was knocked down (Figure 3G). In agreement, gene expression analysis of embryonic stem cell factors involved in breast cancer42 were downregulated in Tim3-KD cells (Figure S3F). GSEA showed positive correlation of TIM3+ cells with Wong CSCs43 and Yamashita liver CSCs44 genesets (Figure S3G). In addition, GSVA45 confirmed the correlation of TIM3 expression with the CSC_GUPTA signature46 in TCGA-BRCA clinical samples (Figure S3H). Overall, these functional and computational analyses confirmed the EMT-like stemness phenotype of TIM3+ MICs supporting tumor-initiation capabilities.

TIM3 has a cytoplasmatic domain with tyrosine residues, and it is reported to interact with PI3K in immune cells31 and to activate AKT/β-catenin signaling in leukemia cells.47 Accordingly, we found β-catenin signaling enriched in our RNA-seq data (Figure 3C). Proximity ligation assay (PLA) of the PI3K subunit P85 and TIM3 showed strong interaction in BC cells (Figure 3H). Using a phospho-kinase array available for human cells, we observed a reduction in phosphorylation of the glycogen synthase kinase 3 α/β (GSK3-α/β) in TIM3-KD MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure S3I) and in mouse 4T07 Tim3-KD cells detected by western blot (Figure S3J). The dephosphorylated (active) from of GSK3 inhibits β-catenin.48 Hence, active β-catenin was reduced in 4T07 Tim3-KD cells measured by IF (Figure 3I). Instead, Tim3-OE increased nuclear β-catenin in 4T07 cells (Figure S3K). Moreover, β-catenin inhibition demonstrated that β-catenin was required for TIM3-mediated tumorsphere formation (Figure 3J) in agreement with the known functions of β-catenin in EMT and stemness.41,47,49,50 Moreover, using clinical data from the TCGA-BRCA TNBC cohort, TIM3 expression correlated with the β-catenin signaling (Figure 3K). Overall, TIM3+ MICs display pro-survival EMT-like stem cell phenotype related to the β-catenin signaling, which is also related to immunosuppressive effects.40,41

Spatiotemporal analysis of TIM3+ tumor cells in micrometastasis

In order to capture the initial events of metastasis seeding of TIM3+ cells in our models, we monitored 4T07-FLuc-GFP cells by BLI imaging at 0, 6 h, and 3 days after i.c. systemic delivery, showing tumor cells distributed in different organs after 6 h (Figures S4A and S4B). Microscopy of tissue sections demonstrated the presence of DTCs within the liver tissue parenchyma already 6 h after administration (Figure S4C). After 3 days, there was a drop of BLI signal in immunocompetent mice (Figure S4A–S4D), indicating that many DTCs perished at the early days of metastatic tissue seeding, in agreement with previous knowledge.51 Next, to study the temporal dynamics of TIM3 during the early and late stages of metastasis, we designed a dual-reporter system to follow Tim3 levels in vivo (Figure 4A). This system reports Tim3 promoter activity by mCherry fluorescence and nano-luciferase (Nluc) (high sensitivity) allowing monitoring Tim3 expression by BLI (Figure 4A). We validated the precision of the reporter using anti-TIM3 flow cytometry detection and mCherry positivity by flow cytometry in 4T07 cells (Figure S4E).

Figure 4.

TIM3 spatiotemporal dynamics in metastasis

(A) Dual reporter system designed to track bulk tumor metastasis (Firefly luciferase [Fluc]-eGFP) and Tim3 promoter activity (mCherry-Nanoluciferase [Nluc]).

(B) Representative BLI images of Fluc and Nluc signal in IC mice (Balb/c) upon i.c. injection of 4T07 cells experimental metastasis. BLI monitorization of metastatic growth: metastasis curve (blue line) and Tim3 reporter curve (orange line). Bar plot shows the BLI signal ratio of NLuc/FLuc representing the intensity of the Tim3 reporter signal versus the overall bulk tumor metastasis at micrometastasis and macrometastasis time points. n = 8 mice.

(C) BLI ratio of NLuc/FLuc of liver metastasis. n = 8 mice. Statistical significance; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by one-tailed Student’s t test.

(D) BLI ratio curve of NLuc/FLuc metastasis along days of experiment. Each line represents individual mice.

(E) Flow cytometry of 4T07-Tim3 reporter positivity measured by mCherry intensity of liver metastatic digested tissues from ID and IC at micrometastasis and macrometastasis time points. Representative plot of n = 3 individual mice per time point.

(F) IF images from liver micrometastasis and macrometastasis. Luciferase (red) and TIM3 (pink) stainings. Dash line delineates the metastatic tissue. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(G) Schematic representation of the lineage tracing system introduced in 4T07 cells (see STAR Methods for details). Tim3- cancer cells have red fluorescence of dsRed. Tim3+ cancer cells have green fluorescence of eGFP.

(H) In vitro lineage tracing test of Tim3+ and Tim3- 4T07 cells. Induction by 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OHT) O/N at 1 μM. Flow cytometry plots represent dsRed and GFP positive events in no induced cells (top) and 4-OHT induced cells (bottom).

(I) Metastasis lineage tracing using 4T07 cells after intracardiac injection in IC mice. Short TAM induction during the first 3 days of metastatic seeding (see STAR Methods). Bar plots quantifications of all lesions (113) present in livers of 6 independent experiments. Representative immunofluorescence images of liver sections showing TIM3+ (green) and TIM3- (red) metastasis in (I) and (J).

(J) Long-term TAM induction during 21 days after intracardiac injection of 4T07 cells in IC and ID mice. Bar plots quantifications of all lesions (61 IC and 37 ID) present in livers of 4 independent experiments.

Also see Figure S4.

Using this dual-reporter system (constitutive Fluc and TIM3-Nluc-reporter), we performed experimental metastasis assays with 4T07, 66cl4, and EpRas cells via intracardiac delivery. BLI measurements of metastasis and Tim3 activity were assessed by luciferin (Fluc signal) and coelenterazine administration (Nluc signal), respectively, six hours apart to avoid BLI signal overlap. This dual system showed how the whole tumor cell burden decreased suggesting massive cell death at the moment of organ seeding, while TIM3+ cells were positively selected and growing proving their survival advantage at initials days (Figures 4B and S4F). Using the Nluc/Fluc signal ratio, we revealed a remarkable increase of Tim3 levels specific of the early days (0–4 days) of metastasis seeding of 4T07 cells (Figures 4B–4D). After day 5, tumor cell burden started to increase, and Tim3+ cells showed a similar increase rate as the rest of the bulk tumor cells (Figure 4B). Consistently, similar Tim3 survival dynamics were observed using other metastasis models (Figure S4G). These results suggested that TIM3-negative cells mostly died during the initial days of seeding and TIM3+ cells were positively selected by surviving this phase of metastasis. BLI localized measurements captured the same Tim3 dynamics in liver, lung, and brain 4T07 micrometastasis when comparing metastasis at day 3 and 12 (Figures 4C and S4H), being the liver the organ with the highest ratio of TIM3+ levels in accordance to our results (Figures 2B and S1G). Remarkably, tumor cell attrition was not occurring in ID mice and accordingly TIM3 levels did not increase, indicating that Tim3+ cells were not critical to lead metastasis in ID mice (Figures 4D and S4I). These results suggest a crucial role of TIM3-mediated survival by immune-evasion during the metastatic seeding and micrometastasis progression to macrometastasis.

These results were further validated by harvesting 4T07 metastatic livers at day 3 and 12 after i.c. injection (Figures 4E, 4F, and S4J). Flow cytometry measurements showed that most of tumor cells were TIM3+ during the early days of micrometastasis in IC hosts but not in ID hosts (Figure 4E). Accordingly, tissue immunofluorescence confirmed that all tumor cells were TIM3+ at the moment of micrometastasis in the liver (Figure 4F). Instead, the percentage of TIM3+ cells decreased after 12 days in macrometastasis compared to the micrometastasis stage, suggesting cellular plasticity and differentiation of TIM3+ MICs into TIM3- tumors cells (Figures 4E and 4F).

To understand the cellular plasticity of TIM3 expression and the potential origin of the metastasis related to TIM3-derived cells, we engineered a Tim3 lineage tracing system using the CreERT2 recombinase. We generated stable random integration LoxP-DsRed-STOP-LoxP-eGFP 4T07 cells with the CreERT2 expression driven by Tim3 promoter, activated after tamoxifen induction (Figure 4G). The system was tested in vitro and in vivo showing that it was precisely tamoxifen activated (Figure 4H), and no leakiness was detected in the absence of tamoxifen in vivo (Figure S4K). Of note, the in vitro test at day 0 showed similar percentage of TIM3-positive 4T07 cells as measured by flow cytometry, thus validating the specificity of the system (Figures 1H and S1E). Next, we performed i.c. experimental metastasis with 4T07 cells and activated the Cre with tamoxifen treatment right before injection of the cells and during the initial 3 days after injection, followed by treatment withdrawal. After 20 days of experiment, liver tissues were harvested and studied by microscopy to detect the fate-labeling of the metastases. The results showed >93% of GFP-positive cases, indicating that most of the metastases originated from the Tim3-lineage, with a rare minority coming from the Tim3-negative lineage (Figure 4I). Longer activation tamoxifen regimes (20 days) did not show additional % of metastases originated from the Tim3-lineage compared to 3-day induction (Figure 4J). This was in agreement with the peak of expression of TIM3 during the initial days of micrometastasis (Figures 4D–4F). In immunocompromised mice, the Tim3-lineage did not show to be as prevalent, with only 67.6% of GFP Tim3-lineage metastases (Figure 4J). This represents a modest increment considering the starting point of positivity in 4T07 cells in vitro was 36% at the moment of injection (Figure 4H). Therefore, the lineage tracing supported that most of metastases were derived from TIM3+ lineage MICs, and immune pressure executed a positive selection specific of the moment of micrometastasis. Yet, in permissive immunodeficient environments, TIM3+ cells participate in metastasis associated to intrinsic MICs properties, including EMT and stemness. Overall, TIM3+ MICs are specifically advantageous during micrometastasis, through extrinsic immune-evasive and intrinsic EMT/stem cell like properties. These findings are aligned with the EMT/stemness metastatic seeding and posterior reversion to form macrometastasis.39,50,52,53,54,55

TIM3+ MICs reconfigure the immunosuppressive immune landscape of micrometastasis

In order to understand the TIM3+ tumor cell-mediated immune-evasive effects during micrometastasis (in 4T07 Ctrl and Tim3-KD conditions), we isolated CD45+ immune cells as described56 and we performed single-cell RNA-seq from micro- and macro-metastatic liver and adjacent tissue (AT) (Figure 5A and S5A–S5C). Micrometastasis was taken by ex vivo BLI signals not detected by the human eye (Figure S5B). The Leiden algorithm generated 27 clusters of immune populations annotated according to differential gene expression (Figures S5D–S5F). Our analysis showed a good representation of lymphoid and myeloid lineages and subset populations validating the quality of immune cell isolation.

Figure 5.

TIM3+ MICs induce an immunosuppressive environment during micrometastasis

(A) Single cell RNA-seq uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of CD45+ immune cells isolated from liver metastasis after 4T07 Ctrl and Tim3-KD i.c. injection. UMAP representation of: Ctrl (red) and Tim3-KD (blue) in healthy liver adjacent tissue (AT), liver micrometastasis and liver macrometastasis.

(B) scRNA-seq bubble plot showing average expression (color) and percentage expression (size) of different genes defining lymphoid annotated cell compartments across metastatic conditions. Average expression legend is shared among populations. Percentage expression is relative within each immune population type.

(C) Idem B for the myeloid compartment.

(D) scRNA-seq cell fraction of the lymphoid cell compartment in micrometastatic samples from 4T07 Ctrl and Tim3-KD conditions.

(E) Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and γδ T cells from liver micrometastasis from 4T07-Ctrl and 4T07-Tim3-KD. Data represents mean ± SEM, n = 11 independent biological replicates in (E), (F), and (G).

(F) Flow cytometry of cytotoxic γδ T cells (GZMB+) and immunosuppressive (IL17+) γδ T cells. Dot plot represents fold change of IL-17 and GZMB γδ T cell populations in TIM3+ (Ctrl) vs. TIM3- (Tim3-KD) micrometastasis.

(G) Flow cytometry of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (GZMB+, CD69+) and exhausted T cells (PD1+) populations. Dot plot represents fold change of PD1, CD69, and GZMB positivity in TIM3+ (Ctrl) vs. TIM3- (Tim3-KD) micrometastasis. Statistical significance respect to the Ctrl; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by unpaired Student’s t test in (E), (F), and (G).

Also see Figures S5, S6, and Table S2.

Across our conditions of AT, micrometastasis and macrometastasis, we observed dynamic changes of the different immune cell fractions, and most relevant changes occurred in micrometastasis (Figures 5A and S5F). The biggest differences of immune populations between control (TIM3+) and Tim3-KD samples were also observed in micrometastasis. In general, there was a gain of immunosuppressive immune cells in TIM3+ micrometastasis compared to Tim3-KD (Figures 5B and 5C). In detail, comparing control (TIM3+) vs. Tim3-KD, we identified an increase of immunosuppressive populations, in particular of Il-17 γδ T cells in micrometastasis (Figure 5B) and myeloid immunosuppressive populations,57 such as Il-1β+,58 Mmp9, Trem1, Nos2, Prok2 neutrophils, and Arg1+, Tim3 monocytes59 (Figure 5C). B cell compartments were also affected and lost in Tim3-KD micrometastasis (Figure 5B). In contrast, anti-tumoral immune populations were reduced in TIM3+ (Ctrl) micrometastasis compared to the Tim3-KD, such as CD69+ and Gzmb effector CD8+ T cells, dendritic cells (DCs), or Elane+ Camp, Mpo neutrophils60,61,62 (Figures 5B and 5C). To further explore the potential immune-to-immune cell interactions based on the scRNA-seq data, we used the LIANA Tensor cell-cell algorithm.63 The interacting factors of receiving and sender cells were more enriched in micrometastases than macrometastases (Figure S5G). In silico, the LIANA factor-4 included a core of interactions of lymphocytes and γδ T cells with immunosuppressive myeloid cells, which was reduced in the Tim3-KD micrometastasis (Figure S5H and Table S2). Overall, the single-cell transcriptomic analysis was informative in understanding the immune landscape of micrometastasis, which revealed an early induction of an immunosuppressive immune microenvironment in liver micrometastasis mediated by TIM3+ MICs.

Next, spectral flow cytometry analysis of liver micrometastases (Figures S6A and S6B) validated the distribution and percentage of the different cell types of the lymphoid lineage and the myeloid lineage among TIM3+ (Ctrl) and Tim3-KD (Figures S6C–S6G) observed in the scRNA-seq results (Figures 5D and S6F). We confirmed the increase of immunosuppressive IL-17 γδ T cells in Ctrl (TIM3+) liver micrometastasis compared to Tim3-KD micrometastasis (Figure 5E). Cytotoxic GZMB γδ T cells did not show consistent changes among these conditions. Moreover, we also validated the reduction of activated (CD69 and GZMB) effector CD8+ T cells in TIM3+ (Ctrl) micrometastasis (Figure 5F) supporting the scRNA-seq analysis. Overall, these results suggest that TIM3+ MICs orchestrate a permissive immunosuppressive liver microenvironment specific of micrometastasis, with increased IL-17 γδ T cells and low cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.

γδ T cells are important players during liver micrometastasis

To functionally validate relevant immune cell populations mediating TIM3+-MIC effects in the transition from micro-to-macro metastasis, we used neutralizing antibodies to deplete or block specific immune cell populations in IC Balb/c mice, focusing in the most relevant observed in the scRNA-seq data: γδ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and also CD4+ T cells, NK cells, B cells, and neutrophils (Figures 6A and S7A). We performed metastasis rescue experiments comparing 4T07 TIM3+ (Ctrl) and the Tim3-KD condition subjected to blocking antibody treatments specific of the immune populations mentioned, and following the metastatic growth (liver and whole-body metastasis) and mice survival (Figures 6A, 6B, and S7B).

Figure 6.

Functional metastasis assessment of γδ T cells, CD8 T cells, and IL-1β in TIM3-mediated immunosuppression

(A) Blocking antibody scheme; intraperitoneal administration and doses indicated. Seven days before 4T07 tumor cell i.c. injection and, weekly reminder of 250 μg of antibody during the experiment.

(B) Representative BLI images of 4T07 whole body metastasis for the indicated immune blocking conditions.

(C) Boxplot quantification of liver metastasis at micro (day 3) and macro (day 14) time points upon IgG2b, CD8, γδ TCR, and double (CD8, γδ TCR) cell depletion. Each dot represents independent mice.

(D) Boxplot quantification of whole-body metastasis at micro (day 3) and macro (day 14) time points upon IgG2b, CD8, γδ TCR, and double (CD8, γδ TCR) cell depletion. Each dot represents independent mice.

(E) In vitro proliferation and co-culture of γδ T cells with 4T07 tumor cells and flow cytometry. See STAR Methods for details.

(F) Flow cytometry quantification of IL-17 γδ T cell levels after co-culture in non-treated (NT) conditions and upon anti-IL1β treatment. Data represents mean ± SEM, n = 6 (NT) and n = 4 (anti-IL1β) independent biological replicates.

(G) Whole-body metastasis assays after systemic delivery of 4T07-IL-1β-KO cells compared to 4T07 TIM3+ (Ctrl) cells. Representative BLI images of metastasis at the indicated conditions. BLI metastasis growth curves. Data represents mean ± SEM, n = 10 independent mice.

(H) Liver metastatic lesions at day 3 of metastatic seeding of 4T07-IL-1β-KO cells compared to 4T07 TIM3+ (Ctrl) cells.

(I) Representative BLI images of ex vivo metastatic livers at day 14 after i.c. injection of 4T07-Tim3+ (Ctrl) and 4T07-IL-1β-KO cells. Statistical significance respect to the Ctrl; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by two-tailed Student’s t test in (C), (D), (F), and (G); unpaired Student’s t test in (H).

Also see Figure S7.

γδ T cell neutralization decreased liver metastasis of TIM3+ control cells to a similar level of Tim3-KD cells suggesting that, without immunosuppressive γδ T cells, TIM3+ cells lose their selective advantage during liver micrometastasis to macrometastasis validating their implication in liver micrometastasis and overall metastasis (Figures 6C and 6D). These effects persisted at later time points liver metastasis, but not in other organs (Figures 6B and 6C) nor survival effects (Figure S7B), suggesting a more prominent role of γδ T cells in liver metastasis than other organs. Regarding CD8+ T cells, their blocking rescued the liver and whole-body metastatic ability of Tim3-KD cells reaching same capacity as TIM3+ cells at later time points (day 14) (Figures 6C and 6D). Moreover, this specific depletion resulted in poor mice survival of the Tim3-KD condition similar to the control-TIM3+ cells (Figure S7B). Considering the importance of the interplay between both populations during the dynamics of micro-to-macro metastasis, we performed a double neutralization of γδ T cells and CD8+ T cells, which resulted in a complete loss of the Tim3-KD differential effect in micrometastasis and macrometastasis time points, both in the liver (Figure 6C) and overall metastasis (Figure 6D), underscoring the relevance of both cell types in the process of micro-to-macro-metastasis. These results were aligned with the results obtained in NSG mice (Figures 2A and S2B). In contrast, when evaluating the depletion of CD4+ T cells, B cells, neutrophils, and NK cells, we did not observe conclusive effects as none of them showed a clear rescue in metastatic growth of Tim3-KD cells (Figures S7C and S7D) neither reduced the extended survival of Tim3-KD compared to control-Tim3+ conditions (Figure S7B). Overall, these results functionally validated the implications of γδ T cells mediating the TIM3+ licensing of micrometastasis, especially in the liver, and CD8+ T cells as key players preventing metastasis of TIM3- cells.

The induction of IL-17 γδ T cells has been reported to be mediated by IL-1β from immune cells.64 Moreover, β-catenin signaling induces IL-1β,65 which is confirmed in our models with high IL-1β expression in Tim3-OE cells and downregulated IL-1β in Tim3-KD 4T07 cells (Figure S7E). Hence, we performed co-culture of Tim3-OE tumor cells with isolated γδ T cells in vitro as described66,67 (Figure 6E). The co-culture of Tim3-OE cells modestly increased IL-17 levels in γδ T cells, although relevant in these in vitro settings. Importantly, blocking IL-1β prevented and reduced the levels of IL-17 γδ T cells (Figures 6F). Due to the limitations of working with γδ T cells in vitro,68 we explored the impact of IL-1β-KO (knock-out) in TIM3+ 4T07 cells in vivo (Figure S7F). IL-1β-KO TIM3+ cells drastically reduced their metastatic seeding in different organs (Figure 6G), specifically in the liver (Figure 6H), and impaired posterior development of liver metastasis (Figure 6I). Overall, these in vitro and in vivo functional assays revealed mechanistic insights validating the TIM3+/β-catenin/IL-1β axis in promoting IL-17 γδ T licensing micrometastasis.

TIM3-expressing tumor cells independently predict poor breast cancer patient outcome

To evaluate the risk of metastasis associated to TIM3 expression in tumor cells, we used 257 primary tumor samples from breast cancer patients including all subtypes and I-III disease stages (Figure S8A). IHC revealed that TIM3 expression in tumor cells was strongly associated to worse prognosis for disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in all subtypes (Figures 7A and S8B). Remarkably, TIM3 score in iTILs did not predict patient outcome (Figure 7B). The TIM3 expression score in tumor cells was significantly enriched in the relapsing patients (Figure 7C), which posits TIM3 as predictive biomarker determined by the univariate ROC analysis (Figure S8C). Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed how TIM3+ in tumor cells (eTIM3), but not in other compartments (TILs or fibroblasts), was an independent prognostic factor for DFS with a hazard ratio 7.2 CI 95% (Figure 7D). Among subtypes, TNBC concur with the worst prognosis of TIM3+ patients (Figure S8B) and across stages the worse prognosis was at high-risk stage-III (Figure S8D). These findings support the potential use of eTIM3 as biomarker for the stratification of high-risk relapse BC patients.

Figure 7.

Clinical and preclinical evaluation of TIM3 blockade for breast cancer metastasis

(A) Disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) Kaplan-Meier curves of IHC epithelial-tumor TIM3+ and TIM3- breast cancer primary tumor samples. Data obtained from Tissue microarrays (TMAs) with 257 breast cancer primary tumors from all subtypes. Statistical significance calculated by Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) for Chi-square and p value.

(B) DFS Kaplan-Meier curves of IHC intratumoral tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) TIM3+ and TIM3- breast cancer primary tumor samples. TMAs with 252 breast cancer primary tumors from all subtypes. Statistical significance calculated by Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) for Chi-square and p value.

(C) Violin plot of TIM3 score in patients stratified by relapse (n = 42) and non-relapse (n = 215) from breast cancer primary tumor samples. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by two-tailed Student’s t test.

(D) Multivariate Cox regression analysis of TIM3 IHC from previous samples including p value and hazard ratio (HR) with confidence interval. Factor names: TIM3 in tumor epithelial cells (eTIM3), intratumoral TILs (iTIM3), and fibroblasts (fTIM3). Estrogen-receptor positivity (ER), HER2 positivity (HER2), patient stage-II BC (pT2), patient stage-III BC (pT3), patient lymph node-1 (pN1), patient lymph node-2 (pN2), and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

(E) Intraportal 4T07 cell injection and anti-TIM3 treatment. Representative images of liver metastasis of anti-IgG2a and anti-TIM3 conditions. Boxplots representing liver metastatic growth by BLI measurements during early time points of the experiment. Each dot represents an individual mouse.

(F) Spontaneous metastasis assay using 4T1 MFP injection in Balb/c mice. At 4 × 4 mm size, anti-Tim3 treatment starts. On the left, the graph represents the primary tumor volume, and the scheme of neoadjuvant/adjuvant treatment regime of TIM3-blockade therapy (250 μg). On the right, bar plot quantification of spontaneous metastatic incidence at day 40 and take rate of metastasis incidence. Met (metastasis detection) or No-Met (no metastasis detection). n = 14 and n = 15 mice per condition. Statistical significance; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, by Chi-square test.

(G) Graphical abstract of TIM3+ tumor cells from early seeding to macrometastasis in the liver.

Also see Figure S8.

Anti-TIM3 therapy to thwart immune-evasive MICs

TIM3 blockade agents are already being used in clinical trials as ICIs. However, here, we used TIM3 blockade therapy to target MICs during micrometastasis. First, to study TIM3 blockade in liver metastasis seeding, we performed intraportal vein injection for liver metastasis. In this experimental model, anti-TIM3 (Bio X cell) therapy reduced metastatic seeding and survival at the early time points (days) of metastatic initiation in the liver (Figure 7E). Second, in experimental metastasis assays after i.c. 4T07 injection, mice were treated every 4 days with 250 μg/mL of anti-TIM3 via i.p. injection. Treated mice showed reduced overall metastasis compared to non-treated animals. More than 55% of the treated mice responded to anti-TIM3 therapy (Figure S8E). Of note, anti-TIM3 therapy phenocopied the metastatic decrease of Tim3-KD cells, and the administration of anti-TIM3 plus Tim3-KD condition did not present significant additional suppressive effects (Figure S8F), suggesting that the effects of anti-TIM3 are mostly mediated by targeting TIM3 in tumor cells.

Next, with the aim to mimic a clinical therapeutic scenario, we assessed TIM3 blockade therapy in a neoadjuvant/adjuvant (NA/A) setting to reduce and prevent breast cancer metastasis. For this purpose, we used spontaneous metastasis assays with MFP of 4T1 cells followed by tumor resection to allow posterior metastasis development. The neoadjuvant anti-TIM3 phase started when tumors reached 4 × 4 mm, and the adjuvant phase continued after tumor resection when tumors reached 8 × 8 mm. In this setting, anti-TIM3 therapy did not show difference in primary tumor growth, which phenocopies the lack of effect of Tim3-KD in primary tumor growth (Figure 2F). Remarkably, as occurring with the Tim3-KD (Figure 2A), the NA/A TIM3 blockade reduced metastasis and prevented 80% of lung and liver metastasis incidence at day 40 (Figures 7F and S8G, 8H), suggesting a promising MIC-targeting therapy to prevent metastasis. Thus, our results in clinical samples and preclinical models suggest the initiation of clinical studies of (neo)adjuvant TIM3 blockade for TIM3+ stage-II/III high-risk breast cancer patients to halt subclinical metastasis.

Discussion

In this study, by investigating the metastatic colonization dynamics influenced by the immune pressure in distant organs, we discovered a mechanism specific of micrometastasis immune evasion. We demonstrate that TIM3 is critical for the seeding and survival of micrometastasis, when stemness and immune-evasion are required to overcome the challenges of the distant tissues (Figure 7G). A main observation of our study is that the tumor biology and the immune microenvironment of micrometastasis are governed by distinct mechanisms compared to macrometastases, indicating a necessity to consider appropriate (neo)adjuvant therapeutic strategies, especially immune-based therapies at this disease stage.

Our results provide evidence for the existence of phenotypic metastasis immunoediting in distant organs. Experimental metastasis assays revealed how the immune selective pressure selects MIC-like aggressive tumor phenotypes escaping immunity associated with stemness and EMT traits. This is consistent with the phenotypes found in clinical breast cancer datasets from metastatic samples.29,30 Additionally, stem cell-like phenotypes have been shown to have immune evasive properties, from embryonic stem cells, adult stem cells, to cancer stem cells,7,9,69,70 including metastatic latency and regenerative programs in metastasis.6,71,72 Altogether suggests that stem cell programs are intrinsically linked to immune-evasion from development to malignant metastasis.

Distant organ seeding is a metastasis bottleneck that selects for the fittest cells. Our dynamic Tim3 reporter and Tim3-lineage tracing tools revealed the highest TIM3 levels during micrometastasis and underscored the essential role of TIM3 in supporting the survival of tumor cells in this vulnerable stage, thus originating metastasis. This is a result of TIM3-mediated immunosuppression operating in micrometastasis and further supported by tumor-intrinsic stem cell properties, as suggested by the moderate increase of Tim3+-lineage cells upon induction in immunodeficient mice, and the TIC ability of TIM3+ cells in LDA in vivo assays. In macrometastasis, TIM3 exhibits reversibility, although still maintaining higher levels compared to primary tumors as shown in our models and clinical data. These results suggest that TIM3+ cells are MICs, and the reversion is in consonance with the MIC principles of cellular plasticity, differentiation, and EMT reversion in overt macrometastasis.5,39,73,74

The unexpected expression of TIM3 in breast tumor cells found in this study is in consonance with other studies showing expression of TIM3 in malignant cells in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG),21 although the TIM3 blockade effects were mainly occurring in immune-TIM3+ microglia and macrophages causing major proinflammatory effects. TIM3 has also been reported to promote proliferation of myeloid leukemia stem cells,20,75 supporting a pro-tumoral role. In breast cancer, in vitro studies showed TIM3 expression in cancer cells that led to apoptosis inhibition, proliferation, invasion,19 and also T cell inhibition in vitro through galectin-9 secretion.76 In this context, our results provide important conceptual advance of the role TIM3 in tumor cells in breast cancer metastasis immunity, specifically of MICs at micrometastasis. Importantly, our BC clinical data and preclinical data suggest that TIM3 plays a more relevant role in metastatic tumor cells rather than in immune cells, supporting the use of TIM3 blockade to target tumor cells to prevent metastatic relapse.

We showcase functions of TIM3 associated with EMT-like, stemness phenotypes, and immune-suppression. This includes the enrichment of Wnt, Hedgehog, and Notch pathways in TIM3+ cells, which are key EMT and stemness signaling pathways.41,77,78,79 These findings are in agreement with the current understanding of plastic EMT hybrid states considered “the seeds” of distant organs and leading aggressiveness.39,80 Mechanistically, we show TIM3/β-catenin signaling in our transcriptomic analyses and validations, in consonance with the TIM3 activation of AKT/β-catenin signaling in myeloid leukemia cells,20,47 and interaction with P85 (PI3KR1),15 which is known to inactivate the β-catenin inhibitor GSK3-β.81 Therefore, the TIM3/β-catenin axis has previous mechanistic evidence in hematopoietic cells. Importantly, β-catenin is a central player not only in EMT induction and stemness82 but also in tumor immunosuppression,9,83,84 aligned with the immune-evasive stem cell phenotype of TIM3+ cells and pro-survival signaling. We identified β-catenin targets upregulated in TIM3+ cells, notably IL-1β as a TIM3-mediated inducer of IL-17 in γδ T cells that are reported to have an immunosuppressive role in breast cancer metastasis.64,85 This is in agreement of our results in vivo showing that the blocking γδ T cells lose the TIM3 pro-metastatic effect during micrometastasis where TIM3 mediates increased IL-17 γδ T cells.64,86 Our conclusions propose that the TIM3/β-catenin/IL-1β axis is a cornerstone of the micrometastasis immunity.

We focused the study in liver metastasis since TIM3 showed a more prominent role in liver micrometastasis and metastatic outcome. Moreover, liver is a tolerogenic organ and the least responsive to current ICIs, therefore new immune-based therapies are a clinical need. Functional metastasis assays showed a leading effect mediated by γδ T cells, as their neutralization reduced liver micrometastasis to a similar level as Tim3-KD cells, suggesting no differential advantageous function of TIM3 in micrometastasis when γδ T cells are absent. Moreover, our results showed the relevant interplay of γδ T cells with CD8+ T cells in the dynamics of micro-to-macro metastasis, which mechanistically aligns with the fact that pro-tumoral γδ T cells can suppress CD8+ T cells.87,88 Therefore, we unveil a role of γδ T cell specific of micrometastasis.

We have found TIM3 expression as poor prognostic factor only when expressed in tumor cells for the different BC subtypes (TNBC, HER2, and HR+ subtypes), and not in TILs. Previous reports show confounding predictive value of TIM3, when TIM3 analysis was assessed only in TILs or in bulk tumor cells including stroma.89,90,91 Hence, our findings convey that TIM3 should be distinctively evaluated in the tumor compartment for clinical assessment. On the therapeutic side, TIM3 blockade has shown tolerability in clinical assays, without additional toxicity to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies. Our preclinical neoadjuvant-adjuvant TIM3 blockade strategy suggests the potential to eradicate minimal residual disease in high-risk patients, thereby preventing later metastatic outbreaks, an important challenge and unmet need in clinical oncology. This underscores the importance of spatiotemporal understanding of the disease for effective therapeutic intervention against micrometastases or residual disease. Altogether, these findings support the initiation of clinical trials targeting TIM3 to block micrometastasis in patients at high-risk of relapse and poor outcome (eTIM3+ stage-II/III patients).

Limitations of the study

A limitation of preclinical models in immuno-oncology research is the inability to use human cells in vivo without compromising immune system integrity. Hence, we used syngeneic mouse breast cancer models to study metastasis while preserving physiological immunity essential to our investigation. Additionally, fluorescent-labeling systems introduce immunogenicity; however, we showed that the TIM3-mediated phenotype was also maintained in unlabeled tumor cells. Our study focuses on immune escape mechanisms independent of neoantigen identity. We employed five distinct murine BC models, including EpRas cells, which are not derived under immune pressure and used in metastasis studies.22,23,24,25 We also used established murine metastasis models: 4T1, 4T07, and 66cl4 cells (Balb/c origin), and AT3 cells (C57BL/6 origin). We mostly used 4T07 cells, which offer a clear temporal window for metastasis after systemic delivery, and 4T1 cells, for spontaneous metastasis assays. Both 4T07 and 4T1 are TNBC models with Trp53 hot-spot mutations,92 mimicking the clinical features of human TNBC, which is the subtype with the highest clinical impact of TIM3.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Requests for further information should be directed to the lead contact, Toni Celià-Terrassa (acelia@researchmar.net).

Materials availability

Unique/stable materials generated in this study are available upon request.

Data and code availability

Raw transcriptomic data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and are available under accession no.; GEO: GSE260480 (4T07-Ctrl and Tim3-KD from lung and liver metastasis), GEO: GSE260481 (EpRas metastasis from different hosts), and GEO: GSE260482 (single cell-RNA sequencing of CD45+ cells from 4T07 liver metastasis). The study did not generate new code.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the AECC LAB grant (LABAE19007CELI), FERO foundation (FERO-MANGO, ref PFERO2020.2), Chiara Giorgetti 2021 Asociación Cáncer de Mama Metastásico, the Worldwide Cancer Research charity (grant 20-0156), Generalitat de Catalunya (SGR-22 00037), LaCaixa foundation (HR23-00392), and Instituto de Salud Carlos III-FSE (PI21/00020; CPII22/00001) to T.C.-T. This work was also supported by ISCIII (CIBERONC CB16/12/00241, PI21/00002), AGAUR (2021 SGR 00776), and FEDER to J.A. Also, Postdoctoral AECC 2023 (POSTD234709BLAS) to S.B.B. Also supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) with ERDF, ISCIII (AES Program, grant PI21/00142; CIBERONC; Biobank PT23/00114) to F.R. We thank the CRG/UPF flow cytometry assistance. We thank animal facility assistance. Cartoons created with BioRender.

Author contributions

Conceptualization C.R., I.S., and T.C.-T.; Conception, T.C.-T.; methodological and experimental lead, C.R. with the help of I.S., P.T., S.A., M.S.-F., S.B.-B., J.A.P., M.D., A.C.-M., and I.P.-N.; computational analysis, A.A., P.T., Y.G., and H.B.; tissue histology, S.P.B.; TIM3 IHC analysis, F.R., GEICAM, and J.I.C.; A.G.-Z., E.M.d.D., and B.B. provided the ConvertHER samples; T.M., S.S., J.A., F.R., B.B., and L.C. provided TMA of human samples and data; scientific analytical discussion M.C-A., A.B., J.A., and GEICAM; T.C.-T. and C.R. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results.

Declaration of interests

L.C. receives personal fees from Roche, MSD, AstraZeneca, Diaceutics; non-financial support Roche, MSD, AstraZeneca, Phillips. F.R. has Speaker/advisory role for Roche, AstraZeneca, MSD, BMS, Novartis, GSK, Astellas, Abbvie, Menarini, Pfizer, Sophia, Agilent, Merck, Amgen, Janssen, Lilly, BioGene Funding: Roche, AstraZeneca, Menarini, Pfizer, Agilent. J.A. receives advisory/speaker fees from Roche, Pfizer, MSD, Gilead, Menarini, Bayer, Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, AstraZeneca Daiichi-Sankyo; travel Gilead, AstraZeneca Daiichi-Sankyo. J.A. and T.C-T have patents on using LCOR for therapeutic purposes (not related to this study). B.B. receives fees for consulting or advisory role with Lilly, Pfizer, MSD, AstraZeneca, Menarini, Gilead. Speakers’ bureau with Roche, MSD, Daichii Sankio, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Lilly, Gilead. Travel accommodation by Pfizer, Roche and Daichii Sankio.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| IHC: Human TIM-3 Affinity Purified | R&D systems S.L | Cat#: AF2365; RRID: AB_355235 |

| IHC: Polyclonal Rabbit anti-Goat, HRP | Dako | Cat#: P0449; RRID: AB_2617143 |

| IF: TIM3 Monoclonal antibody | Proteintech | Cat#: 60355-1-Ig; RRID: AB_2881464 |

| IF: Purified Mouse Anti-N-Cadherin | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 610920; RRID: AB_2077527 |

| IF: Purified Mouse Anti-E-Cadherin | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 610182; RRID: AB_397581 |

| IF: Recombinant Alexa Fluor® 488 Anti-Vimentin antibody | Abcam | Cat#: AB185030 |

| IF: Purified Rat Anti-Mouse CD45R/B220 | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 553084; RRID: AB_394614 |

| IF: PE Armenian Hamster anti-mouse TCR γ/δ Antibody | BioLegend | Cat#: 118108; RRID: AB_313832 |

| IF: Mouse β-catenin antibody (E−5) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#: sc-7963; RRID: AB_626807 |

| IF: Rabbit non-phospho (Active) β-catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41) (Clone D13A1) | Cell signaling | Cat#: 8814; RRID:AB_11127203 |

| IF: mouse anti-GFP tag | Proteintech | Cat#: 66002-1-Ig; RRID: AB_11182611 |

| IF: rabbit anti-mCherry | Abcam | Cat#: AB167453; RRID: AB_2571870 |

| IF: Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 555 | Invitrogen | Cat#: A-21428; RRID: AB_141784 |

| IF: Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 647 | Invitrogen | Cat#: A-21245; RRID: AB_2535813 |

| IF: Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L), Superclonal™ Recombinant Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 555 | Invitrogen | Cat#: A28180; RRID: AB_2536164 |

| IF: Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L), Superclonal™ Recombinant Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 647 | Invitrogen | Cat#: A32728; RRID: AB_2633277 |

| IF: Goat anti-Rat IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 555 | Invitrogen | Cat#: A-21434; RRID: AB_2535855 |

| IF: Goat anti-Armenian Hamster IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 647 | Invitrogen | Cat#: A78967; RRID: AB_2925790 |

| FC: Pe/Cy7 anti-TIM3 (Clone RMT3-23) | Biolegend | Cat#: 119716; RRID: AB_2571933 |

| FC: APC/Cy7 anti-CD45 (Clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat#: 103115; RRID: AB_312980 |

| FC: FITCI anti-CD45 (Clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat#: 103108; RRID: AB_312973 |

| FC: Pe/Cy5 anti-CD3 (Clone 145-2C11) | Biolegend | Cat#: 100310; RRID: AB_312675 |

| FC: PE/Dazzle594 anti-CD3e (Clone 145-2C11) | Biolegend | Cat#: 100347; RRID: AB_2564028 |

| FC: PE anti-CD8 (Clone 53–6.7) | Biolegend | Cat#: 100708; RRID: AB_312747 |

| FC: PercP/Cy5.5 anti-CD4 (Clone GK15) | Biolegend | Cat#: 100434; RRID: AB_893324 |

| FC: FITCI anti-NK1.1 (Clone PK136) | Biolenged | Cat#: 108706; RRID: AB_313393 |

| FC: Pe/Cy7 anti-CD220 (Clone RA3-6B2) | Biolegend | Cat#: 103201; RRID: AB_312986 |

| FC: Texas Red anti-CD19 (Clone 6D5) | Biolegend | Cat#: 115501; RRID: AB_313636 |

| FC: Pe/Cy7 anti-γδ TCR (Clone GL3) | Biolegend | Cat#: 118123; RRID: AB_11203530 |

| FC: PE anti-hTIM3 (Clone F38-2E2) | Biolegend | Cat#: 345006; RRID: AB_2116576 |

| FC: BV421 anti-hCD24 (Clone ML5) | BD Biosicences | Cat#: 562789; RRID: AB_2737796 |

| FC: Pe/Cy7 anti-hCD44 (Clone IM7) | Biolegend | Cat#: 103028; RRID: AB_830785 |

| sFC: BUV395 anti-CD8 (Clone 53–6.7) | BD Biosicences | Cat#: 565968; RRID: AB_2739421 |

| sFC: BV421 anti-IL-17a (Clone TC11-18H10.1) | Biolegend | Cat#: 506925; RRID: AB_10900442 |

| sFC: cFluor v547 anti-CD45 (Clone 30-F11) | Cytek | Cat#: R7-20571 |

| sFC: BV750 anti-CD4 (Clone GK1.5) | Biolegend | Cat#: 100467; RRID: AB_2734150 |

| sFC: AF488 anti-Gzmb (Clone QA18A28) | Biolegend | Cat#: 396423; RRID: AB_2924601 |

| sFC: RB744 anti-CD3 (Clone 17A2) | BD Biosicences | Cat#: 570649; RRID: AB_3685926 |

| sFC: PE-CF594 anti-CD69 (Clone H1.2F3) | BD Biosicences | Cat#: 562455; RRID: AB_11154217 |

| sFC: Pe-Cy5 anti-Foxp3 (Clone FJK-16s) | Thermo | Cat#: 15-5773-80; RRID: AB_468805 |

| sFC: APC anti-PD1 (Clone 29F.IAI2) | Biolegend | Cat#: 135210; RRID: AB_2159183 |

| sFC: BUV395 anti-CD11b (Clone M1/70) | BD Biosicences | Cat#: 565976; RRID: AB_2721166 |

| sFC: BUV737 anti-CD11c (Clone N418) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 367-0114-80; RRID: AB_2895934 |

| sFC: BV785 anti-F4/80 (Clone BM8) | Biolegend | Cat#: 123141; RRID: AB_2563667 |

| sFC: cFluor B584 anti-Ly6G (Clone 1A-8) | Cytek | Cat#: R7-20543 |

| sFC: APC-Fire810 anti-Ly6C (Clone HK1-4) | Biolegend | Cat#: 128055; RRID: AB_2910291 |

| WB: Mouse monoclonal anti-vinculin (clone 7F9) | Santa Cruz | Cat#: sc-73614; RRID: AB_1131294 |

| WB: anti-phospho GSK3 alpha/beta (S21/9) | Cell Signaling | Cat#: 9331S; RRID: AB_329830 |

| WB: Goat anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) | Abcam | Cat#: AB6721; RRID: AB_955447 |

| WB: Rabbit anti-Mouse IgG H&L (HRP) | Abcam | Cat#: AB6728; RRID: AB_955440 |

| In vivo: anti-IgG2b isotype (Clone MPC-11) | BioXCell | Cat#: BE0086; RRID: AB_1107791 |

| In vivo: anti-IgG1 isotype (Clone TNP6A7) | BioXCell | Cat#: BP0290; RRID: AB_2687813 |

| In vivo: anti-mouse CD4 (Clone GK1.5) | BioXCell | Cat#: BE0003-1; RRID: AB_1107636 |

| In vivo: anti-mouse CD8 (Clone YTS169.4) | BioXCell | Cat#: BE0117; RRID: AB_10950145 |

| In vivo: anti-mouse TCRγδ (Clone UC7-13D5) | BioXCell | Cat#: BE0070; RRID: AB_1107751 |

| In vivo: anti-rat Kappa immunoglobulin (Clone MAR 18.5) | BioXCell | Cat#: BE0122; RRID: AB_10951292 |

| In vivo: anti-mouse Ly6G (Clone 1A8) | BioXCell | Cat#: BP0075-1; RRID: AB_1107721 |

| In vivo: anti-mouse IL-1b | BioXCell | Cat#: BE0246; RRID: AB_2687727 |

| In vivo: anti-mouse TIM3, InVivoPlus (Clone RMT3-23) | BioXCell | Cat#: BP0115; RRID: AB_10949464 |

| In vivo: Ultra-LEAF anti-mouse CD20 (Clone SA2711G2) | BioLegend | Cat#: 152116; RRID: AB_2629619 |

| In vivo: anti-asialo GM1 | Wako Chemicals | Cat#: 98610001; RRID: AB_516844 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Tim3-mCherry-IRES-Nluc | VectorBuilder | VB211227-1106hky |

| Cre reporter (EF1a-LoxP-DsRed-STOP-LoxP-eGFP) | Addgene | Cat#: 62732 |

| Tim3-CreERT2-Neo | VectorBuilder | VB230412-1204pkn |

| Px330-mCherry | Addgene | Cat#: 98750 |

| pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) | Addgene | Cat#: 48138 |

| Chemical, peptides and recombinant proteins | ||

| BSA Bovine Serum Albumin | Sigma-Aldrich Quimica S.L. | Cat#: A790_6 |

| Collagenase | Sigma-Aldrich Quimica S.L. | Cat#: C2674 |

| DNase I | Merck Life Sciences S.L.U | Cat#: D5025 |

| Hyaluronidase type 4 | Sigma-Aldrich Quimica S.L. | Cat#: H3506 |

| Percoll | ACEFE S.A.U. | Cat#: 17-0891-02 |

| Recombinant mouse IL-2 | TEBU-BIO SPAIN S.L. | Cat#: 212-12B |

| Recombinant mouse IL-15 | TEBU-BIO SPAIN S.L. | Cat#: 210-15 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| TCRγ/δ + T cell Isolation kit | Milteny Biotec | 130-092-125 |

| Gentlemac C Tubes | Milteny Biotec | 130-093-237 |

| LD selection column | Milteny Biotec | 130-042-901 |

| Dynabeads Mouse T-activator CD3/CD28 | Gibco | Cat·: 11456D |

| Experimental models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Balb/cAnNCrl, H2d | Charles Rivers | Strain code: 028 |

| NOD.Cg-PrkdcSCID Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ | Charles Rivers | Strain code: 614 |

| C57BL/6J | Animal Facility | Strain code: 632 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| EpRas | Y.Kang, Princeton | |

| 4T07 | Y.Kang, Princeton | |

| 4T1 | Y.Kang, Princeton | |

| AT3 | Y.Kang, Princeton | |

| HEK | ATCC | |

| Experimental models: Human Samples | ||

| Primary Breast Cancer tumors | MAR Biobanc, Barcelona Fundación Jiménez Díaz Biobank, Madrid Clinic Hospital Biobank, Valencia |

|

| Primary and metastatic samples | Geicam | |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| mGapdh qRT-PCR primer FW | Integrated DNA Technologies | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

| mGapdh qRT-PCR primer REV | Integrated DNA Technologies | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

| mHmbs qRT-PCR primer FW | Integrated DNA Technologies | CGGGAAAACCCTTGTGATGC |

| mHmbs qRT-PCR primer REV | Integrated DNA Technologies | CTCAGAGAGCTGGTTCCCAC |

| mTim3 qRT-PCR primer FW | Integrated DNA Technologies | AGACATCAAAGCAGCCAAGGT |

| mTim3 qRT-PCR primer REV | Integrated DNA Technologies | TCCGTGGTTAGGGTTCTTGG |

| mPou5f1 qRT-PCR primer FW | Integrated DNA Technologies | CCCGGAAGAGAAAGCGAACT |

| mPou5f1 qRT-PCR primer REV | Integrated DNA Technologies | CCAAGCTGATTGGCGATGTG |

| mNanog qRT-PCR primer FW | Integrated DNA Technologies | GATTCAGGGCTCAGCACCA |

| mNanog qRT-PCR primer REV | Integrated DNA Technologies | AAGGCTTCCAGATGCGTTCA |

| mSox2 qRT-PCR primer FW | Integrated DNA Technologies | AGAGCTAGACTCCGGGCGATG |

| mSox2 qRT-PCR primer REV | Integrated DNA Technologies | ACCCAGCAAGAACCCTTTCCTCG |

| mSnai2 qRT-PCR primer FW | Integrated DNA Technologies | CTCACCTCGGGAGCATACAG |

| mSnai2 qRT-PCR primer REV | Integrated DNA Technologies | GACTTACACGCCCCAAGGATG |

| mIL1b qRT-PCR primer FW | Integrated DNA Technologies | GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT |

| mIL1b qRT-PCR primer REV | Integrated DNA Technologies | ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT |

| IL1b gRNA 1 | Integrated DNA Technologies | ACAAGGAAGCTTGGCTGGAG |

| IL1b gRNA 2 | Integrated DNA Technologies | GGCATTTCACAGTTGAGTTC |

| IL1b gRNA 3 | Integrated DNA Technologies | GTCCGTCAACTTCAAAGAAC |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw transcriptomic data: EpRas metastasis from different mouse strains | This Paper | GEO: GSE260481 |

| Raw transcriptomic data: 4T07-Ctrl and Tim3-KD from lung and liver metastasis | This Paper | GEO: GSE260480 |

| scRNA-seq of CD45+ cells from 4T07 liver metastasis | This Paper | GEO: GSE260482 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FlowJo 10 | ||

| Galore | ||

| Plolty R package (v4.9.1) | ||

| Prism 8 | ||

| R Studio | ||

| Other | ||

| FACSAria Cell Sorter | BD Bioscience | UPF-PRBB Facility |

| S8 Cell Sorter | BD Bioscience | |

| Fortessa | BD Bioscience | |

| Aurora | BD Bioscience | |

| Gentle MACS Octo Dissociator | Milteny Biotec | Cat#: 130-096-427 |

| QuantStudio 12K | Applied Biosystems | UPF-PRBB Facility |

| Pump perfusion | BIOGEN CIENTIFICA S.L. | Cat#: P-DKIT |

| Nikon Eclipse | EMBL-PRBB Facility | |

| TCS SP5 Confocal Microscope | Leica | |

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

Mice were housed in pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of the Barcelona Biomedical Park Research (PRBB). All animal procedures performed in this study were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Research of the PRBB and by the Catalonia Government. Euthanasia was applied when animal health was compromised.

Cell lines

Cancer cell lines (4T07, 4T1, 66cl4, EpRas, MDAMD231 and AT3) were obtained from Y.Kang at Princeton University and cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% of Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 2mM L-Glutamine (Glu) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S). HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC. Full splenocytes and CD8 T cells extracted from OT-I mice were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (Life Technologies, Cat.21875-034) supplemented with 10% of Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S).

Human samples

Surgical resection specimens from primary breast tumors obtained from Hospital del Mar Biobank (MARBiobanc, Barcelona, Spain), Fundación Jiménez Díaz Biobank (Madrid, Spain) and Valencia Clinic Hospital Biobank (Valencia, Spain) have the approval from the Ethical Committee of Clinical Investigation. All individuals gave their informed consent before inclusion.

Method details

Animal studies

In this study, Balb/c, C57BL/6J, and NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mouse strains were used. For metastasis assays, mice were anaesthetized using medetomidine (1 mg/Kg) and ketamine (100 mg/Kg) intraperitoneal administration. Mice were shaved and intracardiac injections were performed with 20,000 cells resuspended in 100 μL of sterile PBS 1X injected in the left ventricle of the mice using a 26G insulin syringe. After intracardiac injection, 100 μL of luciferin (DISMED S.A, LUCK-1) was administered via retroorbital injection to ensure systemic bloodstream delivery, while mice were under isoflurane inhalation (3.5% isoflurane + O2, 0.8L/min). Metastatic growth was measured by bioluminescence (BLI) acquisition using the IVIS system, once or twice per week depending on the experiment for 4–5 weeks. All images were acquired using 1 min of exposure and binning 4. Photon flux quantification was performed with the same ROI for all timepoints using Living-Imaging Software (Perkin Elmer 4.7.3). Orthotopic mammary fat pad (MFP) injection was performed into the fourth mammary gland in the right and left side. After isoflurane inhalation, the incision was done to expose the transplantation site. Cells were resuspended in 1:1 PBS:Matrigel and 10 μl were injected just above the lymph node using a 26 gauge-Hamilton syringe. Wound clips were used to close the incision site. For tumor initiating capacity (TIC) examination, immunocompromised NSG female mice were orthotopically transplanted with series of limiting- cell dilution assays (LDA). Tumor growth rate was measured weekly using a calibrated digital caliper (Merck, Z503576-1EA). For spontaneous metastasis experiments, tumors were surgically resected at 7 × 7mm and metastasis appearance was controlled by BLI measurements. Only upper body images were shown to avoid masking of BLI from primary tumor regrowth. Liver metastasis assay was performed using intraportal vein injection. After anesthesia administration, the surgical area was cleaned with an alcohol pad. Mice were placed in a supine position and the incision was performed in the ventral left side. Using sterile cotton swabs, large and small intestines were pulled out into a gauze pad. Once portal vein was visualized, 10 μL of cells resuspended in PBS 1X were injected using a customized Hamilton of 32G. The hemostatic gauze was held in the injection site until blood flow ceased completely. Then, internal organs were placed back into the abdominal cavity and the peritoneal area was closed with 4-0 vicryl suture. The skin was closed using sterile clips. Liver metastasis growth was measured using bioluminescence acquisition in the IVIS system. After all procedures, buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was injected for 3 days to control post-procedural pain. For organ analysis, animals were euthanized after luciferin administration and ex-vivo organs were placed into a petri dish for BLI measurement using IVIS system. After image acquisition, organs were digested for tumor cells or immune cells isolation according to the follow-up procedures.

In vivo therapies and specific cell depletion/neutralization

For in vivo depletion, 250 μg of antibody were administered by intraperitoneal injection every 4 days during the 3–4 weeks of experiments. Anti-mouse CD4 (Clone GK1.5, Cat. BE0003-1; BioXCell), anti-mouse CD8 (Clone YTS169.4, Cat. BE0117, BioXcell); Ultra-LEAF Purified Rat Ig2b Isotype Control (Clone TRK4530, Cat. 400671, BioLegend); Ultra-LEAF Purified anti-mouse CD20 (Clone SA271G2, Cat. 152116, BioLegend); anti-rat IgG2a isotype control (Clone 2A3, Cat. BP0089, BioXCell); anti-TCRγδ (Clone UC7-13D5, Cat. BE0070, BioXCell); anti-Rat Kappa immunoglobulin (Clone MAR 18.5, Cat BP0290, BioXCell); anti-mouse Ly6G (Clone 1A8, cat BP0075-1, BioXCell) were used. For NK depletion, 100 μL of anti-asialo-GM1 (Wako Chemicals Cat. 98610001) were administered. Immune cell depletion was confirmed by labelling peripheral blood and it was analyzed by flow cytometry. For TIM3 blockade therapy, anti-mouse TIM3 (InVivoPlus Clone RMT3-23, Cat. BP0115, BioXcell) was used for intraperitoneal injection.

Cell lines treatments

For this study, FH353 (β-catenin inhibitor, Merck Millipore CAS108409-83-2); mIL-2 (Tebu-Bio Spain S.L., Cat.212-12B) were used. For the lineage tracing; in vitro, cell lines were induced with 1 μM of 4-OHT (Merck, H7904). In vivo, mice were injected via i.p. with 1.2 mg of tamoxifen (Merck, T5648).

Molecular cloning and plasmids

The FiG (Firefly-IREs-GFP) plasmid was kindly provided by Y.Kang Lab. For mouse Tim3 knock-down (KD) experiments, shRNAs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (nos. TRCN0000099986, TRCN0000099987, TRCN0000099988, TRCN0000099989) in pLKO-Puro lentiviral backbone along with pLKO.1 control vector targeting a scramble RNA. For overexpression (OE) experiments, mouse Tim3 was amplified by PCR and inserted into pLEX-MCS plasmid after SpeI and AgeI digestion (NEB). For the lineage tracing, the Cre Reporter plasmid (EF1a-LoxP-DsRed-STOP-LoxP-eGFP) was purchased from Addgene (Plasmid #62732). The CreERT2 under the promoter of Tim3 was generated by VectorBuilder. For 4T07 IL-1β KO generation, three independent guides (STAR table) were annealed and cloned into digested pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (px458) and pSpCas9(BB)-2A-mCherry (px330) with FastDigest Bpil (Fisher Scientific, catalog no. FD1014). Two pairs of guides cloned into GFP and mCherry Cas9 plasmids respectively were co-transfected into 4T07 through electroporation (1 pulse of 1700 V and 20 ms width). After 48h, double positive cells were sorted in single-cell and collected into 96-well plates. Il1β KO clones were validated by PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Luciferase-based reporter assay

Tim3-reporter was designed using mCherry under the promoter of Tim3 followed by internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) and nanoluciferase (Nluc). This construct was generated by VectorBuilder. For the Tim3-reporter assay, in vitro mCherry mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. In vivo, nano-light substrate (Promega) was retro-orbitally injected to the mice and BLI was measured by IVIS. For Firefly-luciferase metastasis tumor bulk assessment, after 6h of nanolight administration, luciferin (Dismed S.A.) was retro-orbitally injected to obtain total metastatic quantification.

Lineage tracing

CRE reporter construct (EF1a LoxP-DsRed-STOP-LoxP-eGFP) labels cells in red, and switch to green upon LoxP excision. Tim3-CreERT2 construct drives CreERT2 expression under the promoter of Tim3. CreERT2 recombinase activity depends on Tamoxifen binding and leads to the excision of DsRed from the EF1a-LoxP-DsRed-STOP-LoxP-eGFP cassette, thereby permanently labeling cells in green (eGFP). TIM3- cancer cells have red fluorescence by expressing DsRed. Tim3+ cancer cells have green fluorescence by expressing eGFP, and not DsRed anymore. Short-term induction: The system is activated in vitro 48h before injection and 1.2 mg of TAM during the first 3 days of metastatic seeding. Treatment withdrawal at day 3 and organs were harvested at day 20. Long-term induction: The system is activated in vitro 48h before injection and 1.2 mg of TAM during the entire experiment duration, up to 20 days. Organs were harvested at the end point of the experiment.

Viral production and infection of cell lines