Abstract

Background:

It is unclear whether the current North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) trauma system will be effective in the setting of Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO). We sought to model the efficacy of the NATO trauma system in the setting of LSCO. We also intended to model novel scenarios that could better adapt the current system to LSCO.

Methods:

We developed a discrete-event simulation model for patients with combat musculoskeletal injuries treated within the standard NATO system. The primary outcome of the model was survival. The model’s health states were characterized as stable, hypovolemia, sepsis, shock, or death. The model simulated combat intensity by increasing the number of casualties up to 192 casualties per 24 hours. We explored how an augmented system (FC) and Field Hospital (FH) moved closer to the battlefront would change performance.

Results:

Mortality rates rose precipitously from a 10% baseline to 61% at 12 casualties per 24 hours in the base model. This performance was not significantly different from that of the FC model at any casualty rate. Successful evacuation of casualties was significantly more for the FH model versus the base model at 12 casualties/24 hours (47.5% vs. 39%; p = 0.046), 48 casualties/24 hours (45.5% vs. 33%; p = 0.008), and 192 casualties/24 hours (25% vs. 15.5%; p = 0.02).

Conclusions:

The current NATO model experiences high rates of mortality in LSCO. The most effective modification entails situating Field Hospitals within one-hour of ground transport from the battlefront.

Level of Evidence:

Level III. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The current North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military trauma system grew out of the United States and allied forces' experience in Vietnam and was refined in the 2 decades of conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan1-3. In this system, combat casualties are evacuated through prehospital care on the battlefield (level I), to damage control and resuscitation (level II/II+, and Forward Surgical Team [FST]), Field Hospital (FH) care (level III), and transfer out of theater for definitive treatment (levels IV and V)1-4. This system performed admirably during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan3. Prior studies emphasize that these outcomes were potentiated by rapid transportation to medical facilities, often by helicopter1,3-5.

It should be recognized that the nature of warfare for most of modern US military history has been counter-insurgency where US/NATO forces benefitted from relatively unchallenged air superiority allowing aeromedical evacuation and from better armament and protective equipment1-10. These characteristics are unlikely to be present in future Large Scale Combat Operations (LSCO), where allied forces would have to engage comparably-armed opponents with contested air space7-9,11. This is exemplified by the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war, where higher frequencies of combat injured with greater acuity, severe blast exposure, and delayed evacuation times are the norm8,12-14.

In this context, we sought to model the efficacy of the NATO trauma system in the setting of LSCO, merging US/NATO performance measures from the later phases of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan with the wounding patterns and logistical challenges encountered by Ukrainian forces in the current war. We also intended to model novel scenarios where FSTs were augmented with additional medical personnel, or more definitive care (e.g. FH) was moved closer to the battlefront. We hypothesized that moving the FH closer to the battlefront would result in the most efficient means of care delivery, with the lowest resultant case-fatality rates.

Methods

We developed a discrete-event simulation model using Python v3.12 (PSF) delineating the postinjury course of casualties through transitions between health states. We derived the transition probabilities from published literature. The primary outcome was survival. The standardized scenario was a bilateral lower extremity below the knee amputation sustained due to a blast mechanism15. This type of injury was selected as it is one of the characteristic injuries of modern combat and effectively allowed the modeling of blood loss, need for transfusion, emergency surgical intervention, infection, sepsis, and mortality in a manner that would be considered translatable to other serious battlefield injuries such as lumbopelvic dissociation, multilimb amputation, noncompressible chest, and/or abdominal wounds1-6,10-17.

The unit of exposure was 1 combat-infantry battalion (n = 1,000 soldiers). The maximum number of casualties that could be sustained (otherwise rendering the unit combat ineffective) was set at 250. Of these, 20% were estimated to be killed in action16. Therefore, the maximum number of casualties evacuated was set at 200. The standard area of operations represented the doctrinal approach in the current NATO trauma system1-3. This included 1 FST proximate to the front lines and a FH in the rear2. Owing to the absence of air superiority that underpins LSCO, the time from wounding to operative management was set at 1 hour from the battlefront to the FST, with 1 hour transport from the FST to the FH and 2-hour transport from the battlefront to the FH4,5. The base case assumed that combat injured would be evacuated to the FST first and then from the FST to the FH once stabilized. In the event that the FST was unable to treat additional casualties, they were diverted to the FH. Medical facility capabilities and exhaustion rules are presented in the Technical Appendix.

We also modeled 2 novel approaches that better align the current NATO trauma system to the realities of LSCO. The “Flying Column” (FC) envisioned a reserve of specialty-trained personnel that would nimbly and rapidly deploy to the operational area of an FST during high-intensity combat. The FC was modeled as a self-contained surgical team capable of setting up its own area of medical operations by vehicle-borne Deployable Medical Systems and could treat as many patients as an FST2. The second approach moved the FH closer to the battlefront, such that surgical intervention occurred within 1 hour of injury.

The model’s health states were characterized as stable, hypovolemia, sepsis, shock, or death. We defined the efficacy of care as successful evacuation from theater. Casualties could transition to hypovolemia or sepsis from the baseline injured state. Patients could transition to shock and/or death from any health state. Transitions occurred at 1-hour intervals based on current health state, environment of care, treatments received, and any post-treatment events (e.g. complications, revision surgery). The time frame of the model was 30 days, or until all simulated patients died or were evacuated.

The ideal treatment protocol was initial surgery at the FST followed by transfer to the FH within 8 hours2-5. Definitive surgery could only be performed at the FH in the base model. All casualties transferred to the FH required 1 surgery within 24 hours of initial injury. Casualties treated in this manner would be held at the FH for 48 hours to ensure no development of complications. Complications were modeled to increase the need for further observation and the risk of mortality or, in specific situations, require revision. After 48 hours of confirmed stability, the casualty would be evacuated from theater.

Casualties were modeled to become hypovolemic, septic, or in shock if timely surgery was not performed3-5,15,18-21. The development of postinjury adverse events was associated with increased risk of mortality (Technical Appendix).

The base model simulated combat intensity by increasing the number of casualties per hour. The initial model of 1 casualty/24 hours was increased incrementally, up to 192 casualties/24 hours. In each instance, we assessed how many casualties were evacuated and how many casualties died (including those waiting for medical treatment and after receiving treatment). Representative casualty figures were selected for presentation in the results, including 12 casualties, 24 casualties, 48 casualties, 96 casualties, and 192 casualties per 24 hours. Comparisons between the performance of the different models, based on the number of live casualties evacuated, were made using the χ2 test (STATA v15.1; STATA Corp). Statistical significance was established, a priori, at p < 0.05. We used 2 sensitivity tests: The FH being moved within 45-minute ground transport from injury and within 30-minute transport.

Results

In the NATO model, mortality rates rose from a 10% baseline at 1 casualty per 24 hours, to 61% at 12 casualties per 24 hours (Fig. 1). A mortality figure exceeding 70% was initially appreciated once 60 casualties were incurred within 24 hours. The point at which the number of casualties dying while waiting for care exceeded those dying after treatment was at 72 casualties per day.

Fig. 1.

Mortality rates per number of combat casualties in a 24-hour period including overall figures and estimates for those dying while awaiting treatment (Pre-Rx) and after receiving treatment (Post-Rx) in the current NATO trauma system. NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

In the augmented (FC) model, mortality rates similarly rose quickly to 54.5% at 12 casualties per 24 hours (Fig. 2). A mortality figure exceeding 70% was not appreciated until 78 casualties were incurred within 24 hours. The point at which the number of casualties dying while waiting for care exceeded those dying after treatment was at 72 casualties per day.

Fig. 2.

Mortality rates per number of combat casualties in a 24-hour period including overall figures and estimates for those dying while awaiting treatment (Pre-Rx) and after receiving treatment (Post-Rx) in the augmented NATO trauma system (e.g. “Flying Column” supporting a Forward Surgical Team). NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

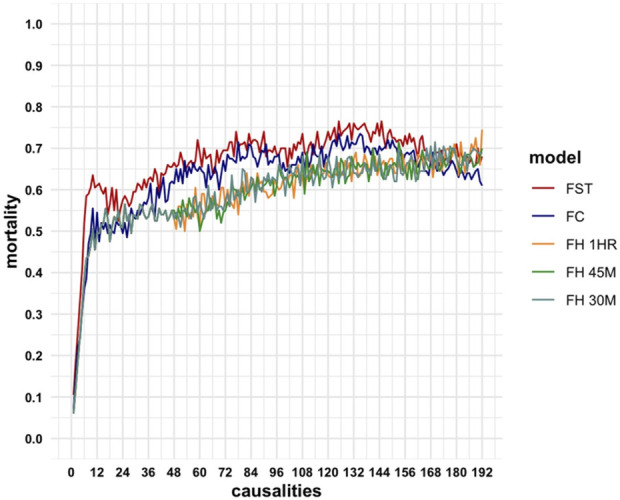

In the model where the FH was moved to within 1 hour of the battlefront, mortality at 12 casualties per 24 hours was 49.5% (Fig. 3). Overall mortality rates exceeding 70% were not encountered until more than 168 casualties presented per 24 hours. At no point in the model did the number of casualties who died while waiting for treatment exceed the number of casualties who died after treatment. The performance of the FC model was not significantly different from the current NATO system at any of the main casualty points considered (Table I). Successful evacuation of a live casualty was significantly more in the scenario where the FH was moved to within 1 hour of the battlefront, as compared with the current system at 12 casualties per 24 hours (47.5% vs. 39%; p = 0.046), 48 casualties per 24 hours (45.5% vs. 33%; p = 0.008), and 192 casualties per 24 hours (25% vs. 15.5%; p = 0.02). The performance of the models where the FH was moved even closer to the battlefront was not substantively different from that of the FH at a 1-hour distance (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Mortality rates per number of combat casualties in a 24-hour period including overall figures and estimates for those dying while awaiting treatment (Pre-Rx) and after receiving treatment (Post-Rx) when the Field Hospital is moved within one hour of ground transport from the battlefront.

Fig. 4.

Mortality rates per number of combat casualties in a 24-hour period for the current NATO trauma system (FST), augmented NATO trauma system (FC), Field Hospital moved within 1 hour of ground transport from the battlefront (FH-1HR), and the sensitivity tests where the Field Hospital was moved within 45 minutes (FH-45M) and 30 minutes of the frontline (FH-30M). FC = Flying Column, Fh = Field Hospital, FST = Forward Surgical Team, and NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

TABLE I.

The Number (Percentage) of Casualties Surviving to Evacuation Based on Total Casualties Presenting Per 24-Hour Period in the Current NATO System (FST), Augmented NATO Model (FC), and the Scenarios Where the FH is Moved to Within 1 Hour, 45 Minutes, and 30 Minutes of the Battlefront

| 12 Per Day (%) | 24 Per Day (%) | 48 Per Day (%) | 96 Per Day (%) | 192 Per Day (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FST | 78 (39.0) | 84 (42.0) | 66 (33.0) | 63 (31.5) | 31 (15.5) |

| FC | 90 (45.0) | 100 (50.0) | 75 (37.5) | 63 (31.5) | 45 (22.5) |

| FH | |||||

| 1 h | 95 (47.5) | 93 (46.5) | 91 (45.5) | 76 (38.0) | 50 (25.0) |

| 45 min | 95 (47.5) | 93 (46.5) | 87 (43.5) | 76 (38.0) | 56 (28.0) |

| 30 min | 95 (47.5) | 93 (46.5) | 91 (45.5) | 73 (36.5) | 59 (29.5) |

FC = Flying Column, FH = Field Hospital, FST = Forward Surgical Team, and NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Discussion

Over the last 50 years, the success of the NATO military system occurred primarily during low-intensity combat1-7,11,18. The realities of LSCO are appreciated when one considers that the total number of Ukrainian casualties from 2022 to 2024 (n = 450,000-500,000)22 are nearly an order of magnitude more than total casualties sustained by the United States and allied forces over the 20 years spanning the Iraq and Afghanistan wars23.

Characteristic injuries resulting from modern military weaponry include multiple extremity amputations, ballistic trauma to the chest/abdomen, lumbosacral fractures/dissociations, and polytrauma2,6,10,15-17. The type of treatment required by casualties with these injuries, as well as the risks of adverse events, are well aligned with the model we used, with bilateral lower extremity amputation as a standardized scenario1,3–6,12–17. The base model incorporated rates of adverse outcomes informed by the United States and allied medical experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan1-6,10,16,20,21 distilled through the prism of LSCO in Ukraine8,12-14.

We believe that our findings are important for military medical planners, senior leaders, and medical personnel in countries that rely on the NATO trauma system. The models demonstrate that the capability of the current NATO system in providing effective care declines rapidly as the number of combat casualties escalates. This is compounded by the lack of air evacuation to divert wounded personnel to FHs or disperse injured personnel to other facilities and ensure treatment within the “golden hour” including trauma evaluation, tourniquet removal, and operative intervention. The etiologies behind these reductions in care efficacy include the limited number of medical personnel at the FST, the inability of the FST to provide long-term postsurgical management for combat injured, and restricted capacity for blood transfusions in terms of equipment and blood availability.

The FH is better resourced and can provide comprehensive casualty care, surgical interventions, postsurgical medical management, and blood transfusions. Doctrinally, these units have been situated further back from the battlefront, so they are not at risk of being attacked by the enemy2. This approach did not lead to compromise in care during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan due to the insurgent nature of those conflicts, on-demand helicopter transport, and low combat casualty rates.

In the LSCO environment, our models suggest that positioning the FH such that casualties can be comprehensively treated within the “golden hour” provides the most effective means of reducing mortality. The FH at 1 hour from the battlefront was the only model that consistently ensured the fewest number of casualties died while awaiting treatment, regardless of the number of casualties per 24-hour period. The performance of the FH at 1 hour distant from the front line was also robust to sensitivity testing. The lack of difference in outcomes for the FH 1 hour from the battlefront and the scenarios where it was moved even closer to the front line indicate that this represents the optimal balance between efficient casualty care for wounded personnel in LSCO and minimizing unnecessary risk to medical assets. During periods of heavy fighting, situating the FH with an FST would maximize the number of medical personnel and provide a centralized medical site that could care for wounded coming in from different localities. We do recognize that doing so puts medical assets at greater risk of harm. As such, in sectors where there is less active conflict, the FH could withdraw to a distant position or allow the FST to move forward in the wake of advancing combat units. These exigencies of the LSCO battlefield likely necessitate that the FH become more modular and/or mobile than its current configuration.

Several results are pertinent to orthopaedic surgeons on the whole. A good deal of orthopaedic care following combat injury is administered outside the military system by civilian surgeons24. In the setting of LSCO, it is anticipated that definitive care responsibilities will fall on civilian partner systems and their providers11,24. Moreover, our results reinforce the need for timely surgical intervention within the “golden-hour” for severe orthopaedic trauma, which is also applicable in the civilian sector.

We acknowledge several limitations. Foremost, this remains a simulation study relying on literature-based data for the performance of military medical assets in theater and use of a single type of musculoskeletal casualty for standardization. The care requirements and risks for adverse events of a bilateral lower extremity amputation are comparable with other high-acuity combat injuries encountered in modern war. While this is not the case in every instance, recent research from Ukraine suggests greater rates of severe combat casualties. Wounded soldiers with mild combat injuries may also be able to delay care without ramifications, and their care needs would not be expected to overwhelm, or exhaust, the capabilities of medical units in theater. While our model did not feature a triage system for care delineation, it is unclear how this would perform in the setting of large numbers of severely injured casualties during LSCO. We assumed that the medical units modeled (e.g. FST, FH, etc.) behaved according to doctrine and were staffed accordingly. As a theoretical unit, the FC was constrained by the limitations we devised for it, although these were based on historical FST performance. These assumptions may not hold in situations where staffing/capabilities are different. While our models did account for staffing fatigue, we are unable to effectively address logistic delays or disruption of evacuation chains, that may occur in combat.

In conclusion, the current NATO model experiences high rates of mortality in LSCO. The most effective modification entails situating Field Hospitals within 1 hour of ground transport from the battlefront.

Appendix

Supporting material provided by the authors is posted with the online version of this article as a data supplement at jbjs.org (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A928). This content was not copyedited or verified by JBJS.

Footnotes

A.J. Schoenfeld and M.P. Cote had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: A.J. Schoenfeld, M.P. Cote. Acquisition of data: A.J. Schoenfeld, M.P. Cote, K.E. Holly, R.J. Schoenfeld. Analysis and interpretation of data: A.J. Schoenfeld, M.P. Cote, K.E. Holly, R.J. Schoenfeld, M.R. Bryan, M.O. Hatton, M.B. Harris, T.P. Koehlmoos. Drafting of the Manuscript: A.J. Schoenfeld, M.P. Cote, K.E. Holly, R.J. Schoenfeld, M.R. Bryan, M.O. Hatton, M.B. Harris, T.P. Koehlmoos. Critical Revision of the Manuscript for Important Intellectual Content: A.J. Schoenfeld, M.P. Cote, M.R. Bryan, M.O. Hatton, M.B. Harris, T.P. Koehlmoos. Statistical Analysis: A.J. Schoenfeld, M.P. Cote. Obtained Funding: N/A. Administrative, technical or material support: A.J. Schoenfeld, M.P. Cote, K.E. Holly, M.O. Hatton, R.J. Schoenfeld, T.P. Koehlmoos, M.B. Harris. Study Supervision: A.J. Schoenfeld, M.P. Cote.

The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, assertions, opinions, or policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), United States Military Academy (USMA; West Point), or the Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the US Government.

Investigation performed at Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Disclosure: The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A927).

Contributor Information

Mark P. Cote, Email: Mcote2@mgh.harvard.edu.

Kaitlyn E. Holly, Email: keholly@bwh.harvard.edu.

Roman J. Schoenfeld, Email: roman.schoenfeld@westpoint.edu.

Matthew R. Bryan, Email: mrbryan848@gmail.com.

Malina O. Hatton, Email: Malina_hatton@hms.harvard.edu.

Mitchel B. Harris, Email: mbharris@mgh.harvard.edu.

Tracey P. Koehlmoos, Email: Tracey.koehlmoos@usuhs.edu.

Andrew J. Schoenfeld, Email: roman.schoenfeld@westpoint.edu.

References

- 1.Kotwal RS, Staudt AM, Mazuchowski EL, Gurney JM, Shackelford SA, Butler FK, Stockinger ZT, Holcomb JB, Nessen SC, Mann-Salinas EA. A US military role 2 forward surgical team database study of combat mortality in Afghanistan. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(3):603-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenfeld AJ. The combat experience of military surgical assets in Iraq and Afghanistan: a historical review. Am J Surg. 2012;204(3):377-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard JT, Kotwal RS, Stern CA, Janak JC, Mazuchowski EL, Butler FK, Stockinger ZT, Holcomb BR, Bono RC, Smith DJ. Use of combat casualty care data to assess the US military trauma system during the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts, 2001-2017. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(7):600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langan NR, Eckert M, Martin MJ. Changing patterns of in-hospital deaths following implementation of damage control resuscitation practices in US forward military treatment facilities. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(9):904-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotwal RS, Howard JT, Orman JA, Tarpey BW, Bailey JA, Champion HR, Mabry RL, Holcomb JB, Gross KR. The effect of a golden hour policy on the morbidity and mortality of combat casualties. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(1):15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenfeld AJ, Newcomb RL, Pallis MP, Cleveland AW, Serrano JA, Bader JO, Waterman BR, Belmont PJ. Characterization of spinal injuries sustained by American service members killed in Iraq and Afghanistan: a study of 2,089 instances of spine trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(4):1112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Remondelli MH, Remick KN, Shackelford SA, Gurney JM, Pamplin JC, Polk TM, Potter BK, Holt DB. Casualty care implications of large-scale combat operations. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(2S):S180-S184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawry LL, Mani V, Hamm TE, Janvrin M, Juman L, Korona-Bailey J, Maddox J, Berezyuk O, Schoenfeld A, Koehlmoos T. Qualitative assessment of combat-related injury patterns and injury prevention in Ukraine since the Russian invasion. BMJ Mil Health. 2025:military 2024-002863. [epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1136/military-2024-002863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas B. Preparing for the future of combat casualty care: opportunities to refine the military health system's alignment with the national defense strategy. Rand Health Q. 2022;9(3):18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godfrey BW, Martin A, Chestovich PJ, Lee GH, Ingalls NK, Saldanha V. Patients with multiple traumatic amputations: an analysis of operation enduring freedom joint theatre trauma registry data. Injury. 2017;48(1):75-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holly KE, Hatton MO, Bryan MR, Freedman BA, Helgeson MD, Koehlmoos TP, Schoenfeld AJ. Spinal injuries and spine care in the U.S. military health system (2001-Present). Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2025;50(3):207-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gumeniuk K, Lurin IA, Tsema I, Malynovska L, Gorobeiko M, Dinets A. Gunshot injury to the colon by expanding bullets in combat patients wounded in hybrid period of the Russian-Ukrainian war during 2014-2020. BMC Surg. 2023;23(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazmirchuk A, Yarmoliuk Y, Lurin I, Gybalo R, Burianov O, Derkach S, Karpenko K. Ukraine's Eeperience with Mmnagement of Ccmbat Ccsualties Uuing NATO's Fofour-tr “Changing as Needed” Hehlthcare System. World J Surg. 2022;46(12):2858-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn J, Panasenko SI, Leshchenko Y, Gumeniuk K, Onderková A, Stewart D, Gimpelson AJ, Buriachyk M, Martinez M, Parnell TA, Brain L, Sciulli L, Holcomb JB. Prehospital lessons from the war in Ukraine: damage control resuscitation and surgery experiences from point of injury to role 2. Mil Med. 2024;189(1-2):17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapira S, Goldman S, Givon A, Katorza E, Dudkiewicz I, Epstein D, Prat D. Risk factors for limb amputations in modern warfare trauma: new perspectives. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2025. [epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-24-00935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belmont PJJr, Goodman GP, Zacchilli M, Posner M, Evans C, Owens BD. Incidence and epidemiology of combat injuries sustained during “The Surge” portion of operation Iraqi freedom by a US army brigade combat team. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2010;68(1):204-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapira S, Givon A, Nadler R, et al. The impact of modern warfare on the nature of spinal injuries in combat trauma: A retrospective cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2025;50(16):E324-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belmont PJJr, Davey S, Orr JD, Ochoa LM, Bader JO, Schoenfeld AJ. Risk factors for 30-day postoperative complications and mortality after below-knee amputation: a study of 2,911 patients from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(3):370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montoya KF, Charry JD, Calle-Toro JS, Núñez LR, Poveda G. Shock index as a mortality predictor in patients with acute polytrauma. J Acute Dis. 2015;4(3):202-4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weintrob AC, Murray CK, Xu J, Krauss M, Bradley W, Warkentien TE, Lloyd BA, Tribble DR. Early infections complicating the care of combat casualties from Iraq and Afghanistan. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2018;19(3):286-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carius BM, Bebarta GE, April MD, Fisher AD, Rizzo J, Ketter P, Wenke JC, Salinas J, Bebarta VS, Schauer SG. A retrospective analysis of combat injury patterns and prehospital interventions associated with the development of sepsis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(1):18-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Economist. How many Ukrainian soldiers have died? 2024. Available at: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2024/11/26/how-many-ukrainian-soldiers-have-died. Accessed May 10, 2025.

- 23.USA Facts. How many people have died in the US military, and how? 2024. Available at: https://usafacts.org/articles/how-have-military-deaths-changed-over-time/. Accessed May 19, 2025.

- 24.Dalton MK, Jarman MP, Manful A, Koehlmoos TP, Cooper Z, Weissman JS, Schoenfeld AJ. The hidden costs of war: healthcare utilization among individuals sustaining combat-related trauma (2007-2018). Ann Surg. 2023;277(1):159-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]