ABSTRACT

Aims

This review summarizes the role and future prospects of nuclear medicine in ovarian cancer, focusing on novel radiopharmaceuticals beyond FDG for diagnostic, predictive, and therapeutic applications within a theranostic framework.

Materials and Methods

A narrative literature review was conducted using major databases. Peer‐reviewed articles addressing non‐FDG radiopharmaceuticals in ovarian cancer were identified and assessed; FDG‐based studies were excluded due to the availability of prior comprehensive reviews.

Results

Novel radiopharmaceuticals show potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy, allow early evaluation of treatment response, predict chemotherapy resistance, and support stratification for targeted therapies. Several tracers are under investigation for theranostic use, offering combined diagnostic and therapeutic benefits.

Discussion

Incorporating novel radiopharmaceuticals into ovarian cancer management may help overcome limitations of conventional imaging and systemic therapy. Theranostic strategies, uniting molecular imaging with radionuclide therapy, represent a promising step toward personalized medicine and could significantly influence clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Nuclear medicine, through innovative radiopharmaceuticals and theranostic approaches beyond FDG, is expected to expand its role in ovarian cancer care. Further research is needed to validate these applications and facilitate their integration into clinical practice.

Keywords: diagnostic imaging, nuclear medicine, ovarian neoplasms, positron emission tomography, precision medicine, radionuclide imaging

Emerging radiopharmaceuticals in nuclear medicine could improve ovarian cancer diagnosis and staging, while also enabling assessment of treatment response, therapy resistance, and suitability for targeted therapies.

Abbreviations

- BRCA

breast cancer gene

- CA‐125

carbohydrate antigen‐125

- CD13

aminopeptidase N

- CT

computed tomography

- CXCL12

C‐X‐C motif chemokine 12

- CXCR4

C‐X‐C chemokine receptor 4

- DWI

diffusion weight imaging

- FAPI

fibroblast activation protein inhibitor

- FDG

fluorodeoxyglucose

- FES

fluoro‐17β‐oestradiol

- FLT

fluorothymidine

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HSP90

heat shock protein 90

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MUC16

mucin‐16

- NGR

asparagine‐glycine‐arginine

- PARP

poly (adenosine diphosphate‐ribose) polymerase

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PSMA

prostate specific membrane antigen

- RGD

arginylglycylaspartic acid

- SPECT

single‐photon emission computed tomography

- SUV

standardised uptake value

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is a heterogeneous and challenging disease, with high‐grade serous cancer being the most common type [1]. Most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage and often experience recurrence despite treatment with cytoreductive surgery, platinum‐based chemotherapy, and maintenance therapies [2, 3]. Recurrence is commonly retreated with chemotherapy, sometimes combined with targeted therapies. However, platinum resistance remains a significant hurdle, [4] contributing to a poor prognosis with a 5‐year overall survival rate of just 45% [5].

Imaging is crucial for diagnosing, staging and managing ovarian cancer. Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) are recommended in case of a suspicion of ovarian cancer [6]. Ultrasound, the primary diagnostic tool, is non‐invasive and inexpensive, but operator‐dependent [7]. CT is used for preoperative staging and postoperative monitoring [8]; but it struggles with differentiating malignant from benign (residual) lesions and detecting early stage cancer or small metastases [9, 10, 11]. For example, paracardiac lymph nodes can be hard to differentiate, but their disease status can distinguish between Stage III and Stage IV disease and therefore has treatment implications. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) outperforms CT in detecting peritoneal metastasis [12, 13, 14, 15], and diffusion‐weighted imaging can further improve lesion differentiation [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. However, MRI is limited in its ability to differentiate lymph nodes based solely on diameter, requires advanced imaging sequences to minimise artefacts, and is highly reader dependent [21].

Nuclear medicine, particularly positron emission tomography (PET), has seen significant growth, although its use in ovarian cancer is not yet fully established. [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is the most widely used PET radiopharmaceutical, primarily used in ovarian cancer for detecting lymph node and distant metastases [22, 23, 24]. However, its accuracy can be limited by background glucose metabolism in the gastrointestinal tract and excretion via the urinary tract. Alternative radiopharmaceuticals may offer better solutions for assessing ovarian cancer.

This review focuses on recent advancements in nuclear medicine for ovarian cancer, specifically non‐[18F]FDG radiopharmaceuticals (Figure 1) and explores their roles in diagnosis, staging, treatment selection, chemoresistance prediction, therapeutic monitoring, and their potential for radionuclide therapy.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic overview of the radiopharmaceuticals that are mentioned in this review. The radiopharmaceutical is administered through intravenous injection, where it enters the blood stream and attaches to its binding site: The binding site can be located on the cell surface, within the nucleus or on a different cell type from the tumour microenvironment. CA125, carbohydrate antigen 125; CD13, aminopeptidase N; CTLs, choline transporter‐like proteins; CXCL12, C‐X‐C motif chemokine 12; CXCR4, C‐X‐C chemokine receptor 4; E2, oestradiol; FAP(I), fibroblast activation protein (inhibitor); FES, fluoro‐17β‐oestradiol; FLT, fluorothymidine; GPER, G protein‐coupled oestrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; MUC16, mucin 16; NGR, asparagine‐glycine‐arginine; PARP(i), Poly(adenosine diphosphate‐ribose) polymerase (inhibitor); PSMA, prostate specific membrane antigen; RGD, arginylglycylaspartic acid; SLC43A2, solute carrier family 43 member 2; TK1, thymidine kinase 1; VEGF(R), vascular endothelial growth factor (receptor). Created in BioRender. Veenstra (2025) https://BioRender.com/s16u284.

2. Radiopharmaceuticals for Diagnosis and Staging of Ovarian Cancer

Over the last decade, several novel radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic use in ovarian cancer have been studied.

2.1. Cell Proliferation Markers

Fluorothymidine (FLT), a thymidine (DNA precursor) analogue, can be used to image cell proliferation, which is, almost by definition, upregulated in malignancies. Apart from preclinical studies using ovarian cancer xenografts, [18F]FLT PET/CT has been tested in two studies that included women with ovarian cancer [25, 26]. Both studies involved three patients and found increased tumour uptake. Physiological [18F]FLT uptake is seen in bone marrow, liver, and the urinary tract, but not in the gastrointestinal tract like [18F]FDG [27]. A positive correlation between [18F]FLT uptake and Ki67 mitotic index was found [25], and [18F]FLT uptake correlated better with size reduction on CT after chemotherapy in three patients with recurrent ovarian cancer than [18F]FDG uptake [26].

Methionine is an essential amino acid for cell growth and division. [11C]methionine PET/CT for ovarian cancer has been studied in mice and patients (n = 13) [28, 29]. Tumours in mice showed high [11C]methionine uptake. In the patients, high [11C]methionine accumulation was observed in malignant tumours, while borderline malignant and benign lesions did not show any uptake. These studies, though small, implicate a possibility of using [18F]FLT and [11C]methionine as a diagnostic agent for ovarian cancer. Their performance compared with current standard imaging modalities, however, has yet to be evaluated.

Choline, a building block for cell membranes and thus essential for rapidly dividing cancer cells, is involved in several biological mechanisms and plays a role in cell membrane integrity [30]. Therefore, the increased proliferative activity in tumours can be visualised through radioactively labelled choline. Choline labelled with 11C or 18F has been used as a radiotracer for prostate cancer, and it is still used for localization of parathyroid adenomas. The use of [11C]choline PET compared with [18F]FDG PET in gynecologic cancers, mostly uterine (endometrial adenocarcinoma and carcinosarcoma), cervical (squamous cell), or ovarian cancer has previously been described in a cohort of 21 patients, of whom 18 had primary tumours (ovarian cancer n = 1) and three had recurrent ovarian cancer (total ovarian cancer n = 4) [31]. [11C]Choline PET was able to correctly identify more primary tumours than [18F]FDG PET (16/18 cases vs. 14/18 cases, respectively), but standardised uptake values (SUVs) were significantly higher for [18F]FDG. Both scans identified the primary tumour in the ovarian cancer patient. In the three patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, both scans were false‐negative in two and true‐positive in one of the patients. Also, [11C]choline PET showed physiologic bowel uptake that concealed para‐iliac lymph node metastases where [18F]FDG PET showed clear visibility, limiting its potential for ovarian cancer patients.

Mesothelin is a glycoprotein located at the cell surface that is believed to play a significant role in cell proliferation, growth, and adhesion signalling [32]. Mesothelin is overexpressed in many cancers and interacts with carbohydrate antigen‐125 (CA‐125, also known as mucin‐16 or MUC16). Normal tissue expression of mesothelin is limited to cells lining the peritoneum, pericardium, and pleura [33]. Mesothelin could potentially be used as an alternative to [18F]FDG to avoid uptake in the gastrointestinal tract, but small peritoneal and pleural metastases that frequently occur in ovarian cancer in particular may be missed, substantially reducing the usability of mesothelin. So far, 64Cu‐labelled mesothelin antibodies have been tested in mouse models of ovarian cancer and a total of four patients with ovarian cancer [34, 35]. Although initial in‐human results show promising visibility of ovarian cancer lesions mean SUVmax 14.5 (±8.7) and mean tumour‐to‐blood ratio 2.6 (±1.3), some peritoneal lesions were missed.

2.2. Angiogenesis Markers

Aminopeptidase N (also known as CD13) and integrin αvβ3 are two key regulators involved in tumour angiogenesis and tumour progression [36, 37]. Due to the varying expression levels of CD13 and integrin αvβ3 between ovarian cancer patients, their individual use as a target for radionuclide imaging is limited. To address this, Gai et al. [38] developed a dual‐receptor targeted radiopharmaceutical that consists of asparagine‐glycine‐arginine (NGR) and arginylglycylaspartic acid (RGD, the principal integrin‐binding domain in the extracellular matrix [39]). This tracer, called [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD, targets CD13 and integrin αvβ3. While this approach enhances the likelihood of tumour visualisation, it may not be effective in all patients, as some tumours do not overexpress either NGR or RGD. Long et al. [40] evaluated the effectiveness of [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD in ovarian cancer and found that [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD PET showed high tumour uptake in mouse models with subcutaneous xenografts. When compared with [18F]FDG PET, [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD PET also showed significantly higher tumour‐to‐muscle and tumour‐to‐liver ratios. [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD therefore provided better detail compared to [18F]FDG. In models of animals bearing abdominal metastasis, PET imaging with [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD enabled rapid and clear visualisation of both peritoneal and liver metastases (3–6 mm). In contrast, [18F]FDG failed to distinguish metastatic lesions due to the relatively low metabolic activity and higher physiological intestinal [18F]FDG uptake. The ability to detect small peritoneal metastases makes [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD PET an interesting tracer for further research in humans. If successful, [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD PET may allow for improved staging, improving clinical decision making.

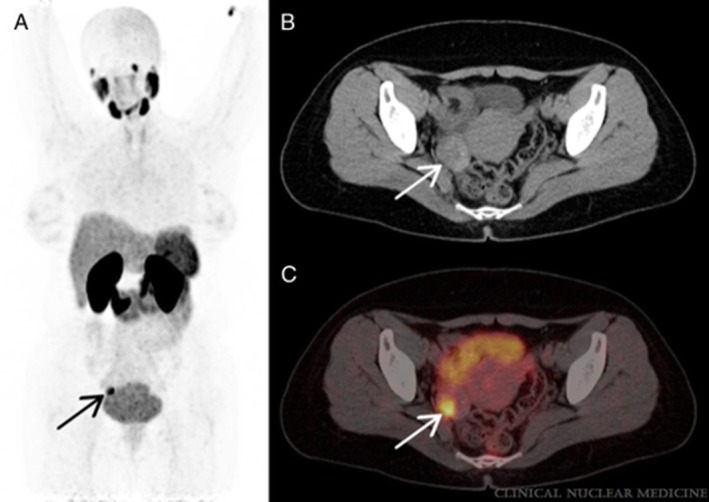

Another potential tumour vasculature target is the prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA), a type II membrane protein that is overexpressed in most prostate cancer cases and upregulated in the neovasculature of solid tumours [41, 42, 43]. Ligands targeting PSMA for locating ovarian cancer seem to be a feasible approach, as [68Ga]Ga‐PSMA‐11 showed increased tumour uptake on PET/CT, corresponding with contrast enhancement on diagnostic CT [44]. An example is shown in Figure 2. Similar results were found for [18F]DCFPyl PET/MRI, which also targets PSMA [45]. Metser et al. [46], however, found that [18F]DCFPyl PET/CT found fewer disease sites than CT, particularly in the upper abdomen and throughout the gastrointestinal tract, probably limiting its clinical utility. Whether or not [68Ga]Ga‐PSMA‐11 PET/CT has additional value over the currently used imaging modalities remains to be determined.

FIGURE 2.

PET/CT scan with [68Ga]Ga‐PSMA‐11 in a 40‐year‐old woman. From Kunikowska et al. [44] (A) Maximum intensity projection, arrow indicates the lesion with abnormal tracer accumulation. (B) CT, arrow indicates the lesion in the right ovary. (C) Fusion PET/CT, arrow indicates the high tracer accumulation in the right ovary lesion visible on CT with SUVmax 13.8. Final histopathology revealed borderline ovarian tumour. Copyright 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health Inc. All rights reserved.

2.3. C‐X‐C Chemokine Receptor 4

[68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4, a radiopharmaceutical for the C‐X‐C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), allows for sensitive and high‐contrast detection of the receptor's presence within the body [47, 48]. CXCR4 is expressed in primary ovarian tumours, [49] and [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 PET/CT has yielded positive results in studies investigating its use for the detection of ovarian cancer (Figure 3) [50, 51]. In these studies, a total of four patients underwent [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 PET/CT. Additional immunohistochemical analyses showed that tumours that were visible on [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 PET/CT (n = 2) had high CXCR4 expression, and tumours that were not (n = 2) had no or mild CXCR4 expression. Therefore, the diagnostic use of [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 PET/CT will probably be limited to tumours with high CXCR4 expression. However, Vag et al. [52] observed only low to moderate PET positivity using [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 in solid tumours that showed high CXCR4 expression in vitro. This discrepancy could indicate that transcript or whole‐cell protein level analysis results in different expression profiles than are seen using PET probes that bind to membrane‐associated chemokine receptors.

FIGURE 3.

CXCR4‐directed positron emission tomography in several malignancies. From Werner et al. [51] Maximum intensity projections. The figure primarily demonstrates moderate to no uptake on CXCR4‐directed imaging (arrows), with the exception of the ovarian cancer patient, where the tumour masses display fairly high CXCR4 expression. (A) PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; (B) PNET, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour; (C) Ovarian cancer; (D) RCC, renal cell carcinoma; (E) PCa, prostate cancer. Copyright 2019 Werner, Kircher, Higuchi, Kircher, Schirbel, Wester, Buck, Pomper, Rowe and Lapa.

2.4. Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor

Perhaps one of the most promising radiopharmaceuticals for imaging is the fibroblast activation protein (FAP) inhibitor (FAPI), which targets cancer‐associated fibroblasts that are present in the tumour microenvironment. FAP is proven to be absent in normal ovaries and most other organs, including the peritoneum, making it an appealing target for imaging of ovarian malignancies [53]. Several studies have compared 68Ga‐labelled FAPI with [18F]FDG PET in ovarian cancer patients (Figure 4). In all studies, FAPI PET outperformed [18F]FDG PET due to a higher sensitivity for diagnosing lymph node metastases [54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59]. Furthermore, very low unspecific intestinal and peritoneal uptake was described [60]. One study compared 68Ga‐labelled FAPI PET/CT with MRI diffusion‐weighted imaging (DWI), also showing more favourable results for 68Ga‐labelled FAPI PET/CT [61]. FAPI PET/CT was especially better for detecting peritoneal tumour depositions and retroperitoneal, peri‐, or supradiaphragmatic lymph node metastases. In one study, 14% of treatment‐naïve and 33% of relapsed patients were upstaged following 68Ga‐labelled FAPI PET/CT compared with [18F]FDG PET/CT, resulting in treatment changes in 10% and 19% of cases, respectively, highlighting the clinical impact of FAPI PET/CT in ovarian cancer [54].

FIGURE 4.

[18F]F‐FDG versus [68Ga]Ga‐FAPI‐04 positron emission tomography. From Zheng et al. [58] A 35‐year‐old woman who previously underwent surgery for poorly differentiated mucinous ovarian adenocarcinoma. Fluorine‐18‐fluorodeoxyglucose (18F‐FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) (a) and gallium‐68‐labelled fibroblast activation protein inhibitor (FAPI)‐04 PET/CT (b) demonstrate intense uptake in the right ilium (long arrow). 18F‐FDG PET/CT showed no abnormal uptake throughout the body, whilst 68Ga‐FAPI PET/CT showed increased uptake in a cervical lymph node, the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and the pelvic site of recurrence (bent arrow). Subsequent biopsy of the cervical node found metastatic ovarian serous carcinoma. Copyright 2022 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health Inc.

Through recent years, several radiopharmaceuticals have been studied for their diagnostic use in ovarian cancer. The current development status of the radiopharmaceuticals mentioned in this review is shown in Table 1, and a short comparative overview can be found in Table 2. Choline, mainly used to study parathyroid disease, and PSMA, to diagnose and monitor prostate cancer, are already routinely used in clinical practice, possibly increasing their chances of being implemented in ovarian cancer diagnostics. Limitations of these radiopharmaceuticals, however, include physiological uptake within the gastrointestinal tract that could cause metastases to be missed, limiting sensitivity. Therefore, we suggest that FAPI seems to be the most promising tracer for future clinical implementation in ovarian cancer. FAPI is increasingly being studied for several cancer types in Phase 2 clinical trials (e.g., NCT05209750, NCT06355427, NCT05263700, NCT05898854, NCT05262855) and has been integrated into clinical practice in a few settings. Although FAPI PET/CT shows considerable diagnostic promise, its cost‐effectiveness has not yet been formally evaluated, highlighting the need for future health economic studies to assess its value relative to other established imaging modalities. 68Ga‐labelled FAPI for ovarian cancer is currently being investigated in a few clinical trials (NCT06232122, NCT05903807, NCT06061874) with results expected around 2026.

TABLE 1.

Current development status of radiopharmaceuticals used in ovarian cancer.

| Radiopharmaceutical | Research phase in ovarian cancer | Research phase in other diseases | Current clinical trials in ovarian cancer a |

|---|---|---|---|

| [89Zr]Bevacizumab | Preclinical | Phase 2 | — |

| [11C]Choline | Phase 1 | Phase 4 | — |

| [177Lu]Lu‐CHX‐A″‐DTPA‐huAR9.6 | Preclinical | Preclinical | — |

| [64Cu]Cu‐cyclam‐RAFT‐c(‐RGDfK‐)4 | Preclinical | Preclinical | — |

| [64Cu]Cu‐DOTA‐trastuzumab | Preclinical | Phase 1 | — |

| [18F]DCFPyL | Phase 1 | Phase 4 | — |

| [68Ga]Ga‐DOTA‐FAPI‐04 | Phase 1 | Phase 1 | NCT05824247 |

| [68Ga]Ga ‐FAPI‐02 | Phase 1 | Phase 1 | — |

| [68Ga]Ga ‐FAPI‐04 | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | — |

| [68Ga]Ga ‐FAPI‐46 | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |

| [18F]FAPI‐74 | Phase 2 | Phase 2 | NCT06503146 |

| [68Ga]Ga‐PNT6555 (FAPI) | Phase 1 | Phase 1 | NCT05956093 |

| [18F]FES | Phase 2 | Phase 4 | — |

| [18F]FLT | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | — |

| [18F]Fluoromethylcholine | Preclinical | Phase 3 | — |

| [18F]FPPRGD2 | Phase 1 | Phase 1 | — |

| [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |

| [64Cu]Cu‐Mesothelin | Preclinical | Preclinical | — |

| [89Zr]Mesothelin | Phase 1 | Phase 1 | — |

| [11C]Methionine | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | — |

| [68Ga]Ga‐NGR‐RGD | Preclinical | Preclinical | — |

| [64Cu]Cu‐NOTA‐pertuzumab F(ab')2 | Preclinical | Preclinical | — |

| [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | — |

| [177Lu]Lu‐CXCR4 | — | Phase 1 | |

| [90Y]Y‐CXCR4 | — | Phase 1 | |

| [68Ga]Ga‐PSMA‐11 | Phase 1 | Phase 4 | NCT04147494 |

| [18F]PyPARP | Preclinical | Phase 1 | — |

| [89Zr]Trastuzumab | Preclinical | Phase 2 | — |

Note: Overview of the radiopharmaceuticals that are explored in this review, including information on their current research phase.

Reviewed on ClinicalTrials.gov on January 28th 2025.

TABLE 2.

Key diagnostic and functional properties of radiopharmaceuticals studied in ovarian cancer.

| Radiopharmaceutical | Molecular target | Theranostic application | Key strengths | Key limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [89Zr]Bevacizumab | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | Potential | High specificity for angiogenesis imaging | Long half‐life of 89Zr; limited availability |

|

[11C]Choline [18F]Fluoromethylcholine |

Cell membrane synthesis | Potential | Evaluates tumour metabolism | Short half‐life of 11C requires on‐site cyclotron; limited data in ovarian cancer |

| [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 | C‐X‐C Chemokine Receptor 4 (CXCR4) | Yes | Potential for both imaging and therapy | CXCR4 expression may vary; limited clinical experience |

|

[18F]FAPI‐74 [68Ga]Ga‐FAPI‐46 |

Fibroblast activation protein | Yes | High tumour‐to‐background ratio; 18F‐label allows centralised production; early clinical use | Limited outcome data in ovarian cancer; still in early phase trials |

| [18F]FES | Oestrogen receptor (ER) | Potential | Clinically validated in breast cancer; ER‐targeted | Only applicable to ER+ tumours, limited ovarian use |

| [18F]FLT | Thymidine kinase‐1 | Potential | Non‐invasive marker of cellular proliferation | Uptake influenced by factors beyond proliferation; limited therapeutic translation so far |

| [18F]FPPRGD2 | Integrin αvβ3 | Potential | Visualises tumour angiogenesis and integrin expression | Limited availability; early phase clinical data only |

| [89Zr]Mesothelin | Mesothelin | Potential | Tumour‐specific antigen with therapeutic potential | Variable expression in ovarian cancer; early stage development |

| [11C]Methionine | Amino acid transport | Potential | Evaluates amino acid metabolism | Short half‐life of 11C; limited widespread use |

|

[18F]PARP1‐inhibitor [18F]PyPARP |

Poly(Adenosine diphosphate‐Ribose)Polymerase (PARP) | Potential | May inform PARP‐inhibitor therapy; DNA repair marker | Still investigational; limited clinical experience |

|

[68Ga]Ga‐PSMA‐11 [18F]DCFPyL |

Prostate specific membrane antigen | Yes | Theranostic potential; well established in prostate cancer | Limited expression in ovarian tumours |

|

[89Zr]Trastuzumab [64Cu]Cu‐DOTA‐trastuzumab |

Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 (HER2) | Potential | Targets HER2‐overexpressing tumours | Limited to HER2+ cases; long half‐life of 89Zr |

Note: Overview of clinically tested radiopharmaceuticals that are investigated in this review, highlighting their molecular targets, potential theranostic applications, and key strengths and limitations.

3. Patient Selection for Targeted Therapy

The previously mentioned radiopharmaceuticals may theoretically also be used to select patients for treatment. The following paragraphs review the current radiopharmaceutical developments in this regard.

3.1. Poly‐ADP‐Ribonuclease Inhibitors

One of the largest advances in the treatment of ovarian cancer is the use of poly(adenosine diphosphate‐ribose)polymerase (PARP) inhibitors. PARP enzymes attach to DNA breaks and attract other DNA damage repair proteins to repair the DNA [62]. PARP‐inhibitors block the enzyme on single‐strand DNA breaks, preventing the repair of DNA damage through poly(ADP‐ribosyl)ation (parylation), leading to the accumulation of DNA breaks and tumour cell death. This treatment is most effective in tumours with deficiencies in homologous recombination repair, which is responsible for repairing double‐strand breaks in the DNA. The PARP1 enzyme can be visualised using radiolabelled ligands, of which a fluorine‐labelled PARP1 inhibitor ([18F]PARP1‐inhibitor) currently seems the most promising [63, 64]. Interim analyses of an ongoing clinical trial (NCT02637934) evaluating [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor PET in ovarian cancer compared results of [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor PET with [18F]FDG PET in eight and 14 patients, respectively [65, 66]. [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor PET showed limited bladder activity because of biliary excretion and showed better identification of primary and recurrent lesions within the pelvis (Figure 5). Contrarily, [18F]FDG was better at detecting peritoneal metastasis. The authors found that high [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor uptake following carboplatin and paclitaxel treatment was indicative of chemoresistance, while low [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor uptake following the same therapy was indicative of chemosensitivity [65]. These results imply that [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor PET can be used to guide clinical management in combination with currently used biomarkers. Furthermore, differences in uptake were found within the tumour itself, suggesting that [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor PET may be able to visualise differences in PARP1 expression within a tumour and between different metastases in the same patient. In addition to this advantage over invasive biopsies, PARP inhibitor PET would also enable repeated imaging to determine (loss of) PARP1 expression during therapy. Interestingly, the authors described high uptake of [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor in five low‐grade ovarian cancer lesions [66]. If confirmed, [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor PET may serve as a biomarker to identify low‐grade ovarian cancer patients with unexpectedly high PARP1 expression, indicating potential sensitivity to PARP inhibitors, even if they do not have breast cancer gene (BRCA) mutations or homologous recombination deficiency. A disadvantage of [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor PET, however, would be its hepatobiliary excretion that could interfere with the detection of abdominal lesions. A novel PARP ligand, [18F]PyPARP, shows a much lower liver‐to‐kidney ratio, which could diminish the interference of hepatobiliary excretion [67]. On the other hand, the increased renal excretion may obscure pelvic lesions.

FIGURE 5.

[18F]PARP1‐inhibitor and [18F]FDG PET/CT images of a patient with ovarian cancer with vaginal cuff lesion. From Makvandi et al. [65] [18F]FTT (left) is a [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor. Minimal radiotracer in the urinary bladder with [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor PET allowed for clear visualisation of the lesion (green arrow) with no interference, despite some bowel uptake (yellow arrow on [18F]PARP1‐inhibitor image). Note excreted radiotracer in the bladder on [18F]FDG PET (yellow arrow on [18F]FDG PET). Copyright 2018, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

3.2. Anti‐Hormonal Treatment

A relatively less frequent subtype of ovarian cancer, low‐grade serous ovarian cancer, is often positive for the oestrogen and progesterone receptor, and whereas these tumours are relatively resistant to chemotherapy, they may respond to hormonal therapy [68, 69, 70]. Van Kruchten et al. [71] performed [18F]fluoro‐17β‐oestradiol (FES) PET/CT, that visualises the oestrogen receptor, in 15 suspected ovarian cancer patients that were planned to undergo surgery. A total of 28/32 (88%) lesions larger than 10 mm that were present on CT were quantified using [18F]FES PET/CT. The other four lesions were visible on PET, but not quantifiable due to high uptake levels in adjacent tissues. There were no new lesions that had not yet been found on diagnostic CT. This study also showed that [18F]FES PET/CT was consistent with histology at cytoreductive surgery [71]. These results indicate that [18F]FES PET/CT could potentially be used to indicate the current oestrogen receptor status, potentially identifying patients with high oestrogen receptor expression levels that could benefit from anti‐hormonal therapy.

3.3. Anti‐HER2 Treatment

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression and/or gene amplification can be found in a subset of ovarian cancer (in up to 30%–40%), depending on the cutoff for receptor positivity [72, 73, 74]. Hence, anti‐HER2 therapies such as trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been tested for HER2‐positive ovarian cancer. Newer agents also include antibody‐drug conjugates targeting the HER2 receptor, such as trastuzumab deruxtecan, for which response rates of up to 45% have been reported in ovarian cancer patients with HER2‐positive disease (HER2 3+ or amplification) [75]. Efficacy has also been observed in ovarian cancers with lower HER2 expression (20% response in HER2 1+) [75]. Radiopharmaceuticals can be used to non‐invasively monitor the expression of HER2, which is involved in tumour cell proliferation and metastasis. In preclinical ovarian cancer models, trastuzumab‐ and pertuzumab‐based imaging have demonstrated a decrease in HER2 expression following trastuzumab or heat shock protein 90 (HSP90)‐targeted therapy, providing a measurable response [76, 77, 78]. Performing a baseline HER2‐targeted PET/CT might therefore be able to detect patients with high HER2 expression levels, suggesting they could benefit from HER2‐directed treatments. The extent to which radiolabelled HER2 antibodies will be of clinical use, however, is still unknown.

3.4. Chemotherapy

C‐X‐C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) functions by binding to its ligand, the C‐X‐C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12), causing changes in cell skeleton rearrangement and prompting cell migration [79]. The activation of CXCR4 and the migration of cancer cells towards organs that express CXCL12 facilitate the directed metastasis of cancer cells [80, 81, 82]. Studies have found that interfering with CXCR4 expression or blocking the CXCR4‐CXCL12 axis using small interfering RNA (siRNA) or other inhibitors (i.e., Plerixafor, TN14003, AMD3100) significantly reduces cell viability, invasion, migration, and adhesion of cancer cells in vitro [83, 84, 85, 86, 87]. [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 PET/CT may therefore enable clinicians to identify patients who could benefit from CXCR4‐directed drugs, although these drugs are not yet available clinically. The CXCR4‐CXCL12 pathway could also be used to predict chemosensitivity. Literature has shown high CXCR4 levels to be associated with resistance to platinum‐based chemotherapy [85, 88, 89]. Visualisation of increased CXCR4 expression using [68Ga]Ga‐CXCR4 PET/CT might therefore be able to show a correlation between the level of CXCR4 and a patient's likelihood to be resistant to platinum‐based chemotherapy, which would be of great benefit for clinical decision making.

Similar prospects for the prediction of chemosensitivity have been described for [11C]choline and [18F]fluoromethylcholine. In a study by Jimbo et al. [90], metastatic castrate‐resistant prostate cancer patients with a ≥ 20% reduction in SUVmax as measured on [11C]Choline PET/CT following three cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy, compared with their baseline SUVmax prior to starting docetaxel, were 3.6 times more likely to have a complete response after six full cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy. Choline uptake and its relation to chemosensitivity have not yet been studied in patients with ovarian cancer, however. Bauerschlag et al. [91] reported that cisplatin‐resistant cells displayed lower [18F]fluoromethylcholine uptake than cisplatin‐sensitive cells, which is why baseline imaging using this ligand might also be able to predict which patients could benefit from cisplatin. So far, this method has not yet been translated to clinical use. The high prevalence of chemoresistance in ovarian cancer patients and the burden of undergoing systemic treatment, however, do provide a clinical incentive to further assess the full potential of these ligands.

4. Monitoring Response to Treatment

Radiopharmaceuticals that are capable of diagnosing cancer are often also useful to assess therapy response. Few studies on novel radiopharmaceuticals have investigated (early) response to ovarian cancer treatment; they are briefly presented in the following paragraphs.

4.1. Chemotherapy and/or Targeted Therapy

Evidence has been presented that [18F]fluorothymidine ([18F]FLT) PET can assess treatment efficacy following carboplatin, paclitaxel, belinostat, and nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase inhibitors (APO866) [92, 93, 94]. [18F]FLT PET has also been used to monitor early treatment response in cisplatin‐resistant ovarian tumours and those treated with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors [28, 95, 96]. Additionally, one clinical study that assessed gemcitabine‐based secondary systemic treatment in three women with recurrent ovarian cancer suggested that [18F]FLT PET may become the new monitoring standard for this indication, as [18F]FLT PET detected treatment response quicker than [18F]FDG PET and showed a decrease in standardised uptake values that was better correlated with CT than [18F]FDG PET [26]. Similar findings were found for the use of [11C]methionine in a study with mice showing a significant decrease in tumour size and lesion uptake following chemotherapy [28]. More extensive research is needed to confirm these findings.

4.2. Anti‐Angiogenic Therapy

Other studies assessed the use of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF plays an important role in tumour angiogenesis [97]. It can be targeted through the humanised monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, and can be visualised using the radioactively labelled [89Zr]bevacizumab. Studies using ovarian cancer mouse models have found that [89Zr]bevacizumab was successfully able to monitor treatment response following HSP90 and mTOR inhibitors [98, 99]. [89Zr]bevacizumab uptake decreased by 44% following 2 weeks of twice‐weekly HSP90‐inhibition therapy and by 22% following daily mTOR‐inhibition for 2 weeks. Simultaneously, tumours in the treatment groups showed significantly slower tumour growth compared with the control groups. It would be interesting to see if radiolabelled‐bevacizumab PET is effective in monitoring early treatment response in ovarian cancer patients.

A study that used radiolabelled arginylglycylaspartic acid (RGD) analogues also showed promising results for monitoring response to therapy. Minamimoto et al. [100] used [18F]FPPRGD2 PET/CT in a total of six patients suffering from ovarian or cervical cancer. Patients were treated with bevacizumab‐containing therapy and monitored by [18F]FPPRGD2 PET/CT scans. Results showed that uptake decreased significantly during the course of therapy, suggesting that [18F]FPPRGD2 has the potential to provide early predictions of response to bevacizumab‐containing treatments.

5. Radiopharmaceuticals as Treatment

Radiopharmaceuticals can also serve as therapeutic agents for delivering internal radiation, a strategy known as targeted radionuclide therapy. When radiopharmaceuticals are used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, they are referred to as theranostic pairs.

5.1. C‐X‐C Chemokine Receptor 4

C‐X‐C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) is a theranostic agent that can be labelled with gallium‐68 for diagnostic purposes and lutetium‐177 or yttrium‐90 for treatment purposes. So far, [177Lu]Lu−/[90Y]Y‐CXCR4 has been used in patients suffering from several types of blood cancers [101, 102, 103, 104]. Their application served as neoadjuvant treatment before undergoing allogenic or autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Although [177Lu]Lu−/[90Y]Y‐CXCR4 will require stem cell replacement because of bone marrow ablation, this CXCR4‐targeted therapy could potentially also be administered to patients with solid tumours, such as end‐stage ovarian cancer patients, that show increased CXCR4 expression on PET [50, 105].

5.2. Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor

A suitable alternative for future theranostic applications could be radiolabelled fibroblast activation protein inhibitor (FAPI), as was recently concluded in a review by Privé and colleagues [106]. FAP‐targeted radionuclide therapy performed on a compassionate use basis has shown effectiveness in several malignancies, but response in ovarian cancer patients has not yet been analysed. So far, results show a favourable toxicity profile with limited high‐grade adverse events, which were manageable if present [106]. The most relevant side effects are related to bone marrow toxicity, such as anaemia, leukopenia, and low platelets. However, a limitation of FAPI‐based therapies is the short tumour retention of current FAPI tracers. This fast clearance from the tumour reduces the radiation dose that radiolabelled FAPI delivers to a tumour, limiting its therapeutic efficacy.

5.3. Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen

Fast clearance could also pose challenges for the use of prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) radioligand therapy. PSMA is often only expressed on neovasculature in non‐prostate cancer, which is why uptake on endothelial cells results in a rapid tumour washout [107, 108, 109]. 177Lu‐labelled PSMA therapy has, however, been studied extensively in prostate cancer patients and shows effectiveness with a well manageable toxicity profile [110, 111]. Like FAPI, PSMA targeted radioligand therapy is yet to be researched in ovarian cancer patients. The favourable safety profile and promising results for these therapies encourage further investigation into their use for several malignancies, including ovarian cancer.

5.4. Arginylglycylaspartic Acid and Carbohydrate Antigen‐125

Some other radiopharmaceuticals have been described for their potential therapeutic use in ovarian cancer. These include radiolabelled arginylglycylaspartic acid (RGD) analogues for the management of peritoneal metastases [112] and use of carbohydrate antigen‐125 (MUC16/CA‐125), which was analysed in a biodistribution study [113] [64Cu]Cu‐cyclam‐RAFT‐c(‐RGDfK‐)4 PET was able to adequately visualise peritoneal metastases in mice. A therapeutic dose resulted in decreased tumour cell proliferation and increased apoptosis. [177Lu]Lu‐CHX‐A″‐DTPAhuAR9.6, that targets MUC16, showed a strong cytotoxic effect in tumours with high MUC16‐expression levels. Mice treated with this agent survived significantly longer than mice treated with saline. Both theranostic agents showed negligible toxicity. Whether or not these treatments are suitable for clinical use in humans remains to be further explored.

6. Current Challenges: Translating Research Into Practice

Over the last years, exciting discoveries have been made within the field of nuclear medicine, especially using cancer cell lines and mouse models. However, many promising targets remain to be assessed in patients. Clinical results so far mainly originate from compassionate use. This implies that access to this therapy remains limited for certain populations globally, since guidelines regarding compassionate use vary per country. Prospective clinical trials are therefore urgently needed to translate promising research results to patients. The ability to translate novel radiopharmaceuticals into clinical care does not only depend on scientific progress, but also on the healthcare system in which they are introduced. Access to cyclotrons and radiopharmaceuticals varies greatly across healthcare settings. While well‐funded academic institutions may operate on‐site cyclotrons or collaborate with regional radiopharmacies, smaller or resource‐limited hospitals typically rely on commercially available or generator‐based agents. New radiopharmaceuticals often require extensive documentation, including toxicity, dosimetry, and clinical data, often calling for dedicated research staff to help guide regulatory submissions and ethics approval. Furthermore, for promising radiopharmaceutical therapies to be used in patients, hospitals need proper equipment such as a cyclotron or generator, secured facilities with up‐to‐date certifications to safely work with radioactive materials, and ample funds to perform this kind of research and clinical care. Alternatively, radiopharmaceuticals could be provided by external companies that specialise in this area. Moreover, due to the short half‐life of some radiopharmaceuticals used in patients, research and clinical facilities using these drugs must be located near the manufacturing companies. Consequently, translational research in nuclear medicine remains complex. The lack of in‐human results following promising preclinical findings does not necessarily indicate that a radiopharmaceutical is unsuitable for clinical application. Nevertheless, the rapid expansion of nuclear medicine highlights its integration into modern medicine, offering promising potential for future translations.

7. Conclusions

Several radiopharmaceuticals have been studied for their potential use in ovarian cancer through recent years. New radiopharmaceuticals such as radiolabelled FAPI may be of great diagnostic use for ovarian cancer by detecting small metastases or distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions. Even though the number of studied cases remains small, PET also has the prospect of successful use in monitoring disease (e.g., PARP‐targeted PET), monitoring therapeutic effects (e.g., FLT PET), predicting which patients are prone to therapy resistance (e.g., CXCR4 PET), and non‐invasively identifying patients who could benefit from novel pharmacological treatments (e.g., FES PET), while targeted radionuclide therapy has high potential for future clinical treatment in ovarian cancer.

Author Contributions

Mara M. K. Veenstra: investigation (lead), writing – original draft (lead). Sophie Veldhuijzen van Zanten: writing – review and editing (equal). Erik Vegt: writing – review and editing (equal). Ingrid A. Boere: writing – review and editing (equal). Heleen J. van Beekhuizen: writing – review and editing (equal). Julie Nonnekens: writing – review and editing (equal). Frederik A. Verburg: supervision (supporting), writing – review and editing (equal). Maarten G. J. Thomeer: conceptualization (lead), supervision (lead), writing – review and editing (equal).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com. Permission to reproduce Figures 2, 3, 4, 5 has been obtained.

Veenstra M. M. K., van Zanten S. V., Vegt E., et al., “Emerging Radiopharmaceuticals Beyond FDG for Ovarian Cancer: A Review of Advances in Nuclear Medicine,” Cancer Medicine 14, no. 17 (2025): e71167, 10.1002/cam4.71167.

Funding: The authors received no specific for this work.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were generated or analysed.

References

- 1. Matulonis U. A., Sood A. K., Fallowfield L., Howitt B. E., Sehouli J., and Karlan B. Y., “Ovarian Cancer,” Nature Reviews. Disease Primers 2 (2016): 16061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lheureux S., Gourley C., Vergote I., and Oza A. M., “Epithelial Ovarian Cancer,” Lancet 393, no. 10177 (2019): 1240–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ledermann J. A., Raja F. A., Fotopoulou C., et al., “Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow‐Up,” Annals of Oncology 29 (2018): iv259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zaib S., Javed H., Rana N., Zaib Z., Iqbal S., and Khan I., “Therapeutic Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer: Emerging Hallmarks, Signaling Mechanisms and Alternative Pathways,” Current Medicinal Chemistry 32 (2024): 923–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. NHS , “Cancer Survival in England, Cancers Diagnosed 2016 to 2020, Followed up to 2021,” NHS Digital 22 (2023): 498. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gonzalez‐Martin A., Harter P., Leary A., et al., “Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow‐Up,” Annals of Oncology 34, no. 10 (2023): 833–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fischerova D., “Ultrasound Scanning of the Pelvis and Abdomen for Staging of Gynecological Tumors: A Review,” Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 38, no. 3 (2011): 246–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Expert Panel on Women's I , Kang S. K., Reinhold C., et al., “ACR Appropriateness Criteria((R)) Staging and Follow‐Up of Ovarian Cancer,” Journal of the American College of Radiology 15, no. 5S (2018): S198–S207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bharwani N., Reznek R. H., and Rockall A. G., “Ovarian Cancer Management: The Role of Imaging and Diagnostic Challenges,” European Journal of Radiology 78, no. 1 (2011): 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alt C. D., Brocker K. A., Eichbaum M., et al., “Imaging of Female Pelvic Malignancies Regarding MRI, CT, and PET/CT: Part 2,” Strahlentherapie und Onkologie 187, no. 11 (2011): 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kyriazi S., Kaye S. B., and deSouza N. M., “Imaging Ovarian Cancer and Peritoneal Metastases—Current and Emerging Techniques,” Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 7, no. 7 (2010): 381–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gadelhak B., Tawfik A. M., Saleh G. A., et al., “Extended Abdominopelvic MRI Versus CT at the Time of Adnexal Mass Characterization for Assessing Radiologic Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) Prior to Cytoreductive Surgery,” Abdominal Radiology 44, no. 6 (2019): 2254–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Torkzad M. R., Casta N., Bergman A., Ahlstrom H., Pahlman L., and Mahteme H., “Comparison Between MRI and CT in Prediction of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Index (PCI) in Patients Undergoing Cytoreductive Surgery in Relation to the Experience of the Radiologist,” Journal of Surgical Oncology 111, no. 6 (2015): 746–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Low R. N., Barone R. M., and Lucero J., “Comparison of MRI and CT for Predicting the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) Preoperatively in Patients Being Considered for Cytoreductive Surgical Procedures,” Annals of Surgical Oncology 22, no. 5 (2015): 1708–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dohan A., Hoeffel C., Soyer P., et al., “Evaluation of the Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Index With CT and MRI,” British Journal of Surgery 104, no. 9 (2017): 1244–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rizzo S., De Piano F., Buscarino V., et al., “Pre‐Operative Evaluation of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients: Role of Whole Body Diffusion Weighted Imaging MR and CT Scans in the Selection of Patients Suitable for Primary Debulking Surgery. A Single‐Centre Study,” European Journal of Radiology 123 (2020): 108786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Espada M., Garcia‐Flores J. R., Jimenez M., et al., “Diffusion‐Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging Evaluation of Intra‐Abdominal Sites of Implants to Predict Likelihood of Suboptimal Cytoreductive Surgery in Patients With Ovarian Carcinoma,” European Radiology 23, no. 9 (2013): 2636–2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Michielsen K., Dresen R., Vanslembrouck R., et al., “Diagnostic Value of Whole Body Diffusion‐Weighted MRI Compared to Computed Tomography for Pre‐Operative Assessment of Patients Suspected for Ovarian Cancer,” European Journal of Cancer 83 (2017): 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meng X. F., Zhu S. C., Sun S. J., Guo J. C., and Wang X., “Diffusion Weighted Imaging for the Differential Diagnosis of Benign vs. Malignant Ovarian Neoplasms,” Oncology Letters 11, no. 6 (2016): 3795–3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dai G., Liang K., Xiao Z., Yang Q., and Yang S., “A Meta‐Analysis on the Diagnostic Value of Diffusion‐Weighted Imaging on Ovarian Cancer,” Journal of BUON 24, no. 6 (2019): 2333–2340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rizzo S., Avesani G., Panico C., et al., “Ovarian Cancer Staging and Follow‐Up: Updated Guidelines From the European Society of Urogenital Radiology Female Pelvic Imaging Working Group,” European Radiology 35 (2025): 4029–4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khiewvan B., Torigian D. A., Emamzadehfard S., et al., “An Update on the Role of PET/CT and PET/MRI in Ovarian Cancer,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 44, no. 6 (2017): 1079–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Narayanan P. and Sahdev A., “The Role of (18)F‐FDG PET CT in Common Gynaecological Malignancies,” British Journal of Radiology 90, no. 1079 (2017): 20170283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang X., Yang L., and Wang Y., “Meta‐Analysis of the Diagnostic Value of (18)F‐FDG PET/CT in the Recurrence of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer,” Frontiers in Oncology 12 (2022): 1003465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Richard S. D., Bencherif B., Edwards R. P., et al., “Noninvasive Assessment of Cell Proliferation in Ovarian Cancer Using [18F] 3'deoxy‐3‐Fluorothymidine Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography Imaging,” Nuclear Medicine and Biology 38, no. 4 (2011): 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsuyoshi H., Morishita F., Orisaka M., Okazawa H., and Yoshida Y., “18F‐Fluorothymidine PET Is a Potential Predictive Imaging Biomarker of the Response to Gemcitabine‐Based Chemotherapeutic Treatment for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: Preliminary Results in Three Patients,” Clinical Nuclear Medicine 38, no. 7 (2013): 560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Been L. B., Suurmeijer A. J., Cobben D. C., Jager P. L., Hoekstra H. J., and Elsinga P. H., “[18F]FLT‐PET in Oncology: Current Status and Opportunities,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 31, no. 12 (2004): 1659–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trencsenyi G., Marian T., Lajtos I., et al., “18FDG, [18F]FLT, [18F]FAZA, and 11C‐Methionine Are Suitable Tracers for the Diagnosis and In Vivo Follow‐Up of the Efficacy of Chemotherapy by miniPET in Both Multidrug Resistant and Sensitive Human Gynecologic Tumor Xenografts,” BioMed Research International 2014 (2014): 787365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lapela M., Leskinen‐Kallio S., Varpula M., et al., “Metabolic Imaging of Ovarian Tumors With Carbon‐11‐Methionine: A PET Study,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 36, no. 12 (1995): 2196–2200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yao N., Li W., Xu G., Duan N., Yu G., and Qu J., “Choline Metabolism and Its Implications in Cancer,” Frontiers in Oncology 13 (2023): 1234887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Torizuka T., Kanno T., Futatsubashi M., et al., “Imaging of Gynecologic Tumors: Comparison of (11)C‐Choline PET With (18)F‐FDG PET,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 44, no. 7 (2003): 1051–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Faust J. R., Hamill D., Kolb E. A., Gopalakrishnapillai A., and Barwe S. P., “Mesothelin: An Immunotherapeutic Target Beyond Solid Tumors,” Cancers (Basel) 14, no. 6 (2022): 1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang K., Pastan I., and Willingham M. C., “Isolation and Characterization of a Monoclonal Antibody, K1, Reactive With Ovarian Cancers and Normal Mesothelium,” International Journal of Cancer 50, no. 3 (1992): 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kobayashi K., Sasaki T., Takenaka F., et al., “A Novel PET Imaging Using (6) (4)cu‐Labeled Monoclonal Antibody Against Mesothelin Commonly Expressed on Cancer Cells,” Journal of Immunology Research 2015 (2015): 268172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lamberts L. E., der Houven M.‐v., van Oordt C. W., et al., “ImmunoPET With Anti‐Mesothelin Antibody in Patients With Pancreatic and Ovarian Cancer Before Anti‐Mesothelin Antibody‐Drug Conjugate Treatment,” Clinical Cancer Research 22, no. 7 (2016): 1642–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Danhier F., Le Breton A., and Preat V., “RGD‐Based Strategies to Target Alpha(v) Beta(3) Integrin in Cancer Therapy and Diagnosis,” Molecular Pharmaceutics 9, no. 11 (2012): 2961–2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luan Y. and Xu W., “The Structure and Main Functions of Aminopeptidase N,” Current Medicinal Chemistry 14, no. 6 (2007): 639–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gai Y., Jiang Y., Long Y., et al., “Evaluation of an Integrin Alpha(v)beta(3) and Aminopeptidase N Dual‐Receptor Targeting Tracer for Breast Cancer Imaging,” Molecular Pharmaceutics 17, no. 1 (2020): 349–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arnaout M. A., Mahalingam B., and Xiong J. P., “Integrin Structure, Allostery, and Bidirectional Signaling,” Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 21 (2005): 381–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Long Y., Shao F., Ji H., et al., “Evaluation of a CD13 and Integrin Alpha(v)beta(3) Dual‐Receptor Targeted Tracer (68)Ga‐NGR‐RGD for Ovarian Tumor Imaging: Comparison With (18)F‐FDG,” Frontiers in Oncology 12 (2022): 884554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bostwick D. G., Pacelli A., Blute M., Roche P., and Murphy G. P., “Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen Expression in Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Adenocarcinoma: A Study of 184 Cases,” Cancer 82, no. 11 (1998): 2256–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mannweiler S., Amersdorfer P., Trajanoski S., Terrett J. A., King D., and Mehes G., “Heterogeneity of Prostate‐Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Expression in Prostate Carcinoma With Distant Metastasis,” Pathology Oncology Research 15, no. 2 (2009): 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Van de Wiele C., Sathekge M., de Spiegeleer B., et al., “PSMA Expression on Neovasculature of Solid Tumors,” Histology and Histopathology 35, no. 9 (2020): 919–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kunikowska J., Bizon M., Pelka K., Derlatka P., Olszewski M., and Krolicki L., “68 Ga‐Prostate‐Specific Membrane Antigen PET/CT in Ovarian Tumors: Potential to Differentiate Benign and Malignant Tumors Before Surgery: A Preliminary Report,” Clinical Nuclear Medicine 48, no. 2 (2023): e60–e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sadowski E. A., Lees B., McMillian A. B., Kusmirek J. E., Cho S. Y., and Barroilhet L. M., “Distribution of Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) on PET‐MRI in Patients With and Without Ovarian Cancer,” Abdominal Radiology 48, no. 12 (2023): 3643–3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Metser U., Kulanthaivelu R., Chawla T., et al., “(18)F‐DCFPyL PET/CT in Advanced High‐Grade Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Prospective Pilot Study,” Frontiers in Oncology 12 (2022): 1025475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Demmer O., Gourni E., Schumacher U., Kessler H., and Wester H. J., “PET Imaging of CXCR4 Receptors in Cancer by a New Optimized Ligand,” ChemMedChem 6, no. 10 (2011): 1789–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gourni E., Demmer O., Schottelius M., et al., “PET of CXCR4 Expression by a (68)Ga‐Labeled Highly Specific Targeted Contrast Agent,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 52, no. 11 (2011): 1803–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu C. F., Liu S. Y., Min X. Y., et al., “The Prognostic Value of CXCR4 in Ovarian Cancer: A Meta‐Analysis,” PLoS One 9, no. 3 (2014): e92629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Buck A. K., Haug A., Dreher N., et al., “Imaging of C‐X‐C Motif Chemokine Receptor 4 Expression in 690 Patients With Solid or Hematologic Neoplasms Using (68)Ga‐Pentixafor PET,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 63, no. 11 (2022): 1687–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Werner R. A., Kircher S., Higuchi T., et al., “CXCR4‐Directed Imaging in Solid Tumors,” Frontiers in Oncology 9 (2019): 770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vag T., Gerngross C., Herhaus P., et al., “First Experience With Chemokine Receptor CXCR4‐Targeted PET Imaging of Patients With Solid Cancers,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 57, no. 5 (2016): 741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mhawech‐Fauceglia P., Yan L., Sharifian M., et al., “Stromal Expression of Fibroblast Activation Protein Alpha (FAP) Predicts Platinum Resistance and Shorter Recurrence in Patients With Epithelial Ovarian Cancer,” Cancer Microenvironment 8, no. 1 (2015): 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chen J., Xu K., Li C., et al., “[(68)Ga]Ga‐FAPI‐04 PET/CT in the Evaluation of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Comparison With [(18)F]F‐FDG PET/CT,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 50, no. 13 (2023): 4064–4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dendl K., Koerber S. A., Finck R., et al., “(68)Ga‐FAPI‐PET/CT in Patients With Various Gynecological Malignancies,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 48, no. 12 (2021): 4089–4100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu S., Feng Z., Xu X., et al., “Head‐To‐Head Comparison of [(18)F]‐FDG and [(68) Ga]‐DOTA‐FAPI‐04 PET/CT for Radiological Evaluation of Platinum‐Sensitive Recurrent Ovarian Cancer,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 50, no. 5 (2023): 1521–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xi Y., Sun L., Che X., et al., “A Comparative Study of [(68)Ga]Ga‐FAPI‐04 PET/MR and [(18)F]FDG PET/CT in the Diagnostic Accuracy and Resectability Prediction of Ovarian Cancer,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 50, no. 9 (2023): 2885–2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zheng W., Liu L., Feng Y., Wang L., and Chen Y., “Comparison of 68 Ga‐FAPI‐04 and Fluorine‐18‐Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/Computed Tomography in the Detection of Ovarian Malignancies,” Nuclear Medicine Communications 44, no. 3 (2023): 194–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu Y., Pan J., Jing F., et al., “Comparison of (68)Ga‐FAPI‐04 and (18)F‐FDG PET/CT in Diagnosing Ovarian Cancer,” Abdominal Radiology 49, no. 12 (2024): 4531–4542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kratochwil C., Flechsig P., Lindner T., et al., “(68)Ga‐FAPI PET/CT: Tracer Uptake in 28 Different Kinds of Cancer,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 60, no. 6 (2019): 801–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li X., Lv X., Quan Z., et al., “Surgical Evidence‐Based Comparison of [(68)Ga]Ga‐FAPI‐04 PET and MRI‐DWI for Assisting Debulking Surgery in Ovarian Cancer Patients,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 51, no. 6 (2024): 1773–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pommier Y., O'Connor M. J., and de Bono J., “Laying a Trap to Kill Cancer Cells: PARP Inhibitors and Their Mechanisms of Action,” Science Translational Medicine 8, no. 362 (2016): 362ps17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Edmonds C. E., Makvandi M., Lieberman B. P., et al., “[(18)F]FluorThanatrace Uptake as a Marker of PARP1 Expression and Activity in Breast Cancer,” American Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 6, no. 1 (2016): 94–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhou D., Chu W., Xu J., et al., “Synthesis, [(1) (8)F] Radiolabeling, and Evaluation of Poly (ADP‐Ribose) Polymerase‐1 (PARP‐1) Inhibitors for In Vivo Imaging of PARP‐1 Using Positron Emission Tomography,” Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 22, no. 5 (2014): 1700–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Makvandi M., Pantel A., Schwartz L., et al., “A PET Imaging Agent for Evaluating PARP‐1 Expression in Ovarian Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 128, no. 5 (2018): 2116–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Weeks J. K., Pantel A. R., Gitto S. B., et al., “[(18)F]Fluorthanatrace PET in Ovarian Cancer: Comparison With [(18)F]FDG PET, Lesion Location, Tumor Grade, and Breast Cancer Gene Mutation Status,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 66, no. 1 (2025): 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Stotz S., Kinzler J., Nies A. T., Schwab M., and Maurer A., “Two Experts and a Newbie: [(18)F]PARPi vs [(18)F]FTT vs [(18)F]FPyPARP—A Comparison of PARP Imaging Agents,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 49, no. 3 (2022): 834–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gershenson D. M., Bodurka D. C., Coleman R. L., Lu K. H., Malpica A., and Sun C. C., “Hormonal Maintenance Therapy for Women With Low‐Grade Serous Cancer of the Ovary or Peritoneum,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 35, no. 10 (2017): 1103–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sieh W., Kobel M., Longacre T. A., et al., “Hormone‐Receptor Expression and Ovarian Cancer Survival: An Ovarian Tumor Tissue Analysis Consortium Study,” Lancet Oncology 14, no. 9 (2013): 853–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Vetter M., Stadlmann S., Bischof E., et al., “Hormone Receptor Expression in Primary and Recurrent High‐Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer and Its Implications in Early Maintenance Treatment,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 22 (2022): 14242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. van Kruchten M., de Vries E. F., Arts H. J., et al., “Assessment of Estrogen Receptor Expression in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients Using 16alpha‐18F‐Fluoro‐17beta‐Estradiol PET/CT,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 56, no. 1 (2015): 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Oh D. Y. and Bang Y. J., “HER2‐Targeted Therapies – A Role Beyond Breast Cancer,” Nature Reviews. Clinical Oncology 17, no. 1 (2020): 33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pils D., Pinter A., Reibenwein J., et al., “In Ovarian Cancer the Prognostic Influence of HER2/Neu Is Not Dependent on the CXCR4/SDF‐1 Signalling Pathway,” British Journal of Cancer 96, no. 3 (2007): 485–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Uzunparmak B., Haymaker C., Raso G., et al., “HER2‐Low Expression in Patients With Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors,” Annals of Oncology 34, no. 11 (2023): 1035–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Meric‐Bernstam F., Makker V., Oaknin A., et al., “Efficacy and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2‐Expressing Solid Tumors: Primary Results From the DESTINY‐PanTumor02 Phase II Trial,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 42, no. 1 (2024): 47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lam K., Chan C., and Reilly R. M., “Development and Preclinical Studies of (64)cu‐NOTA‐Pertuzumab F(Ab') (2) for Imaging Changes in Tumor HER2 Expression Associated With Response to Trastuzumab by PET/CT,” MAbs 9, no. 1 (2017): 154–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Niu G., Li Z., Cao Q., and Chen X., “Monitoring Therapeutic Response of Human Ovarian Cancer to 17‐DMAG by Noninvasive PET Imaging With (64)cu‐DOTA‐Trastuzumab,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 36, no. 9 (2009): 1510–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Oude Munnink T. H., Korte M. A., Nagengast W. B., et al., “(89)Zr‐Trastuzumab PET Visualises HER2 Downregulation by the HSP90 Inhibitor NVP‐AUY922 in a Human Tumour Xenograft,” European Journal of Cancer 46, no. 3 (2010): 678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kucia M., Jankowski K., Reca R., et al., “CXCR4‐SDF‐1 Signalling, Locomotion, Chemotaxis and Adhesion,” Journal of Molecular Histology 35, no. 3 (2004): 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. De Falco V., Guarino V., Avilla E., et al., “Biological Role and Potential Therapeutic Targeting of the Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 in Undifferentiated Thyroid Cancer,” Cancer Research 67, no. 24 (2007): 11821–11829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hassan S., Buchanan M., Jahan K., et al., “CXCR4 Peptide Antagonist Inhibits Primary Breast Tumor Growth, Metastasis and Enhances the Efficacy of Anti‐VEGF Treatment or Docetaxel in a Transgenic Mouse Model,” International Journal of Cancer 129, no. 1 (2011): 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Martin M., Mayer I. A., Walenkamp A. M. E., Lapa C., Andreeff M., and Bobirca A., “At the Bedside: Profiling and Treating Patients With CXCR4‐Expressing Cancers,” Journal of Leukocyte Biology 109, no. 5 (2021): 953–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Domanska U. M., Timmer‐Bosscha H., Nagengast W. B., et al., “CXCR4 Inhibition With AMD3100 Sensitizes Prostate Cancer to Docetaxel Chemotherapy,” Neoplasia 14, no. 8 (2012): 709–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Yu T., Wu Y., Huang Y., et al., “RNAi Targeting CXCR4 Inhibits Tumor Growth Through Inducing Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis,” Molecular Therapy 20, no. 2 (2012): 398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Li J., Jiang K., Qiu X., et al., “Overexpression of CXCR4 Is Significantly Associated With Cisplatin‐Based Chemotherapy Resistance and Can Be a Prognostic Factor in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer,” BMB Reports 47, no. 1 (2014): 33–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wang S., Wang L., and Chen S. W., “Pan‐Cancer Analysis of CXCR4 Carcinogenesis in Human Tumors,” Translational Cancer Research 10, no. 9 (2021): 4180–4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Figueras A., Alsina‐Sanchis E., Lahiguera A., et al., “A Role for CXCR4 in Peritoneal and Hematogenous Ovarian Cancer Dissemination,” Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 17, no. 2 (2018): 532–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Dubrovska A., Hartung A., Bouchez L. C., et al., “CXCR4 Activation Maintains a Stem Cell Population in Tamoxifen‐Resistant Breast Cancer Cells Through AhR Signalling,” British Journal of Cancer 107, no. 1 (2012): 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Chen G., Chen S. M., Wang X., Ding X. F., Ding J., and Meng L. H., “Inhibition of Chemokine (CXC Motif) Ligand 12/Chemokine (CXC Motif) Receptor 4 Axis (CXCL12/CXCR4)‐Mediated Cell Migration by Targeting Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Pathway in Human Gastric Carcinoma Cells,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 287, no. 15 (2012): 12132–12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jimbo M., Andrews J. R., Ahmed M. E., et al., “Prognostic Role of 11C‐Choline PET/CT Scan in Patients With Metastatic Castrate Resistant Prostate Cancer Undergoing Primary Docetaxel Chemotherapy,” Prostate 82, no. 1 (2022): 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bauerschlag D. O., Maass N., Leonhardt P., et al., “Fatty Acid Synthase Overexpression: Target for Therapy and Reversal of Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer,” Journal of Translational Medicine 13 (2015): 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Jensen M. M., Erichsen K. D., Johnbeck C. B., et al., “[18F]FDG and [18F]FLT Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Following Treatment With Belinostat in Human Ovary Cancer Xenografts in Mice,” BMC Cancer 13 (2013): 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Munk Jensen M., Erichsen K. D., Bjorkling F., et al., “Imaging of Treatment Response to the Combination of Carboplatin and Paclitaxel in Human Ovarian Cancer Xenograft Tumors in Mice Using FDG and FLT PET,” PLoS One 8, no. 12 (2013): e85126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Jensen M. M., Erichsen K. D., Johnbeck C. B., et al., “[18F]FLT and [18F]FDG PET for Non‐Invasive Treatment Monitoring of the Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase Inhibitor APO866 in Human Xenografts,” PLoS One 8, no. 1 (2013): e53410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Aide N., Kinross K., Cullinane C., et al., “18F‐FLT PET as a Surrogate Marker of Drug Efficacy During mTOR Inhibition by Everolimus in a Preclinical Cisplatin‐Resistant Ovarian Tumor Model,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 51, no. 10 (2010): 1559–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Perumal M., Stronach E. A., Gabra H., and Aboagye E. O., “Evaluation of 2‐Deoxy‐2‐[18F]Fluoro‐D‐Glucose‐ and 3′‐Deoxy‐3′‐[18F]Fluorothymidine‐Positron Emission Tomography as Biomarkers of Therapy Response in Platinum‐Resistant Ovarian Cancer,” Molecular Imaging and Biology 14, no. 6 (2012): 753–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ferrara N., “Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor: Basic Science and Clinical Progress,” Endocrine Reviews 25, no. 4 (2004): 581–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Nagengast W. B., de Korte M. A., Oude Munnink T. H., et al., “89Zr‐Bevacizumab PET of Early Antiangiogenic Tumor Response to Treatment With HSP90 Inhibitor NVP‐AUY922,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 51, no. 5 (2010): 761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. van der Bilt A. R., Terwisscha van Scheltinga A. G., Timmer‐Bosscha H., et al., “Measurement of Tumor VEGF‐A Levels With 89Zr‐Bevacizumab PET as an Early Biomarker for the Antiangiogenic Effect of Everolimus Treatment in an Ovarian Cancer Xenograft Model,” Clinical Cancer Research 18, no. 22 (2012): 6306–6314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Minamimoto R., Karam A., Jamali M., et al., “Pilot Prospective Evaluation of (18)F‐FPPRGD2 PET/CT in Patients With Cervical and Ovarian Cancer,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 43, no. 6 (2016): 1047–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Habringer S., Lapa C., Herhaus P., et al., “Dual Targeting of Acute Leukemia and Supporting Niche by CXCR4‐Directed Theranostics,” Theranostics 8, no. 2 (2018): 369–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Lapa C., Hanscheid H., Kircher M., et al., “Feasibility of CXCR4‐Directed Radioligand Therapy in Advanced Diffuse Large B‐Cell Lymphoma,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 60, no. 1 (2019): 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Herrmann K., Schottelius M., Lapa C., et al., “First‐In‐Human Experience of CXCR4‐Directed Endoradiotherapy With 177Lu‐ and 90Y‐Labeled Pentixather in Advanced‐Stage Multiple Myeloma With Extensive Intra‐ and Extramedullary Disease,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 57, no. 2 (2016): 248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Lapa C., Herrmann K., Schirbel A., et al., “CXCR4‐Directed Endoradiotherapy Induces High Response Rates in Extramedullary Relapsed Multiple Myeloma,” Theranostics 7, no. 6 (2017): 1589–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Maurer S., Herhaus P., Lippenmeyer R., et al., “Side Effects of CXC‐Chemokine Receptor 4‐Directed Endoradiotherapy With Pentixather Before Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 60, no. 10 (2019): 1399–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Prive B. M., Boussihmad M. A., Timmermans B., et al., “Fibroblast Activation Protein‐Targeted Radionuclide Therapy: Background, Opportunities, and Challenges of First (Pre)clinical Studies,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 50, no. 7 (2023): 1906–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kunikowska J., Charzynska I., Kulinski R., Pawlak D., Maurin M., and Krolicki L., “Tumor Uptake in Glioblastoma Multiforme After IV Injection of [(177)Lu]Lu‐PSMA‐617,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 47, no. 6 (2020): 1605–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Kunikowska J., Cieslak B., Gierej B., et al., “[(68) Ga]Ga‐Prostate‐Specific Membrane Antigen PET/CT: A Novel Method for Imaging Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 48, no. 3 (2021): 883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Bogsrud T. V., Engelsen O., Lu T. T. T., et al., “All That Glitters Is Not Gold: High Uptake on PSMA PET in Non‐Prostate Cancers Does Not Mean That Treatment With [(177)Lu]Lu‐PSMA‐Radioligand Will Be Successful,” EJNMMI Research 14, no. 1 (2024): 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Hofman M. S., Violet J., Hicks R. J., et al., “[(177)Lu]‐PSMA‐617 Radionuclide Treatment in Patients With Metastatic Castration‐Resistant Prostate Cancer (LuPSMA Trial): A Single‐Centre, Single‐Arm, Phase 2 Study,” Lancet Oncology 19, no. 6 (2018): 825–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Rahbar K., Schmidt M., Heinzel A., et al., “Response and Tolerability of a Single Dose of 177Lu‐PSMA‐617 in Patients With Metastatic Castration‐Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 57, no. 9 (2016): 1334–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Jin Z. H., Tsuji A. B., Degardin M., et al., “Radiotheranostic Agent (64)cu‐Cyclam‐RAFT‐c(‐RGDfK‐) (4) for Management of Peritoneal Metastasis in Ovarian Cancer,” Clinical Cancer Research 26, no. 23 (2020): 6230–6241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Mack K. N., Samuels Z. V., Carter L. M., et al., “Interrogating the Theranostic Capacity of a MUC16‐Targeted Antibody for Ovarian Cancer,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 65, no. 4 (2024): 580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were generated or analysed.