Abstract

Extracellular glutamate (Glu) concentration measured in the brain using microdialysis sampling is regulated differently from that expected for classical neurotransmitters; e.g., the basal Glu concentration is not affected by blocking action potentials. Additionally, other sources, such as glial cells, contribute to Glu extracellular concentration making it difficult to interpret detected changes. We have found that infusing 2.5 μM 13C5-glutamine (Gln) through a microdialysis probe inserted in the rat cortex results in collection of 144 ± 35 nM (n = 11) 13C5-Glu in dialysate. The recovered 13C5-Glu was reduced by 33% by infusion of 20 mM α-(methylamino)isobutyric acid and 58% by 500 mM riluzole, inhibitors of glutamine transport into neurons. The 13C5-Glu measured was reduced by 62% with tetrodotoxin (TTX), a sodium channel blocker, and 59% with (1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (ACPD), a metabotropic glutamate agonist, while endogenous Glu remained unchanged. These results support the hypothesis that the measured 13C5-Glu is derived from neurons via the Gln-Glu shuttle. To further investigate regulation of 13C5-Glu, we applied a stressor (tail pinch), observing a 155% increase in dialysate 13C5-Glu concentration. This effect was blocked by infusion of TTX indicating neuronal release. Local infusion of l-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid (PDC), a Glu uptake inhibitor, increased both endogenous Glu and 13C5-Glu concentrations, consistent with reverse transport and spread of neuronal release. Taken together, these experiments show that metabolic labeling of Glu via Gln delivered through a microdialysis probe allows differentiation of neuronal and other sources of Glu in the brain. The results support the concept of compartmentalized Glu in the brain.

Keywords: microdialysis, glutamate-glutamine shuttle, astrocyte, neuronal glutamate, mass spectrometry

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Glutamate (Glu) neurotransmission is believed to be facilitated by a tripartite synapse consisting of a presynaptic neuron, a postsynaptic neuron, and an astrocyte.1–4 In this model, neurons release a neurotransmitter into a synaptic cleft, raising the concentration to ~1 mM in a few ms.5 The concentration is rapidly reduced by diffusion and reuptake by excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs). Astrocytes are critical to controlling Glu neurotransmission because they provide barriers to diffusion and express ~90% of the EAAT.6 It is estimated that a 10- to 100-fold difference in concentration exists from inside to outside the glial cover, suggesting low spillover from the synapse to extracellular space.6 The extent of spillover may depend on neuronal activity and the amount of glial cover over the synapse. Astrocytes may also release Glu by a variety of mechanisms such as the Cys-Glu antiporter,7 fusion-related release activated by a voltage-dependent calcium channel,8,9 and reverse transport.10 Astrocytic release may maintain Glu tone, modulate neurotransmission, or send signals to more distant synapses.1,7,11 Astrocytes also support neurons by providing Glu via a Glu-glutamine (Gln) shuttle. In the Glu-Gln shuttle, Glu that is taken up by glia12 is converted to Gln by glutamine synthetase. This Gln is released by glia and taken up by neurons, where it is converted to Glu by glutaminase in neurons. In this way, glial cells maintain a supply of neuronal Glu for signaling.13–17

The multiple cellular sources of Glu and synaptic organization complicate the study of Glu signaling by chemical measurements in vivo. In vivo measurements in the brain extracellular space by microdialysis show Glu concentrations of 1–5 μM.18–21 In contrast to other neurotransmitters, the basal Glu concentration measured by microdialysis appears to contain little Glu that was directly released by neurons because it is unaffected by blocking Na+ channels with tetrodotoxin (TTX).22–27 Rather, evidence suggests that at least some of the basal extracellular Glu is released from astrocytes.7,22 Some extracellular Glu may also come from the blood supply.26 These observations imply that minimal neuronal Glu escapes the synapse to extracellular space where microdialysis can sample it under basal conditions.26,28 In contrast, in vivo studies using enzyme electrode sensors have reported somewhat higher Glu concentrations that can be reduced by ~40% by microinjection of TTX near the electrode.29 These results suggest that appreciable Glu does escape the synapse under basal conditions. The difference in observation between microdialysis and electrochemical sensors may relate to the ability of these different size probes to access different spatial concentration domains; however, methodological issues with sensor electrodes, such as effects of enzyme immobilization on selectivity, may also play a role in discrepancies.30

Although the basal Glu measured by microdialysis is not regulated as expected for neuronal release, under some conditions, a change in extracellular Glu that appears to directly relate to neuronal activity can be elicited.31–34 Electrical stimulation of corticostriatal neurons,31 drug-seeking,32 and stress33,34 have all been shown to evoke TTX-sensitive increases in Glu using microdialysis. This latter result agrees with electrochemical sensor measurements showing TTX-sensitive increases in Glu with stress.29,35 These results have been interpreted as spillover from strong neuronal activity. Spillover from Glu synapses under strong stimulation can also be detected by electrophysiology.36 In other experiments, it appears that non-neuronal Glu changes dominate responses.2,7,22,37,38 Although these changes are associated with the astrocytic rather than neuronal release of Glu, they have been shown to have physiological significance.

Given the complexity of extracellular Glu concentration regulation, we sought to develop an approach to distinguish the source of Glu that is detected in vivo using metabolic labeling. Metabolic labeling by stable isotope precursors coupled with measurements by NMR, GC-MS, and LC-MS has been used extensively to study brain metabolism and help elucidate aspects of energy coupling to Glu neurotransmission, Glu metabolism, and the Glu-Gln shuttle.17,39–51 Particularly relevant to this work is a study that followed intravenous infusion of 13C-labeled glucose with detection of 13C-labeled Glu using NMR and microdialysis.52 That work concluded that a large fraction of basal Glu was released from neurons.

Here, we use microdialysis and local metabolic labeling of Glu via the Glu-Gln shuttle, with 13C-labeled Gln delivered by the probe, to discern neuronal Glu from other sources in vivo. We reasoned that if 13C5-Gln was delivered to the brain, it would form 13C5-Glu in neurons near the probe by the Glu-Gln shuttle. Detection of 13C5-Glu would in turn allow measurement of neuronally derived Glu despite a high background of Glu from non-neuronal sources normally detected. We find that 13C5-Glu is detected and is differentially regulated from endogenous Glu, which is primarily 12C-Glu because 12C is the dominant natural isotope for C. These results suggest two distinct pools of Glu, one primarily neuronal and one not, can be measured in vivo. The results also support the idea that Gln-Glu cycling is rapid, with newly formed Glu being readily released by neurons. This approach provides a way to study neuronal Glu by using microdialysis sampling.

2. METHODS

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents.

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. The artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) comprised 145 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 1.01 mM MgSO4, 1.22 mM CaCl2, 1.55 mM Na2HPO4, and 0.45 mM NaH2PO4 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). 13C5-Glu was purchased from Cambridge Isotopes (Andover, MA).

2.2. Microdialysis Probes.

Most experiments used probes constructed as previously described.53 Briefly, 40/100 μm (i.d./o.d.) fused silica capillaries (Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ) were glued side-by-side with a 2 mm offset. The capillaries were ensheathed in a 250 μm o.d. regenerated cellulose membrane with both ends sealed by polyimide sealing resin (Grace, Deerfield, IL). For other experiments (Figures 1 and 2 and Figures SI 1, 3, and 5), CMA12 Elite probes (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) with a 2 mm long, 0.5 mm o.d., and 20 kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane were used. The flow rate of the perfusion fluid through the probe was 1 μL/min.

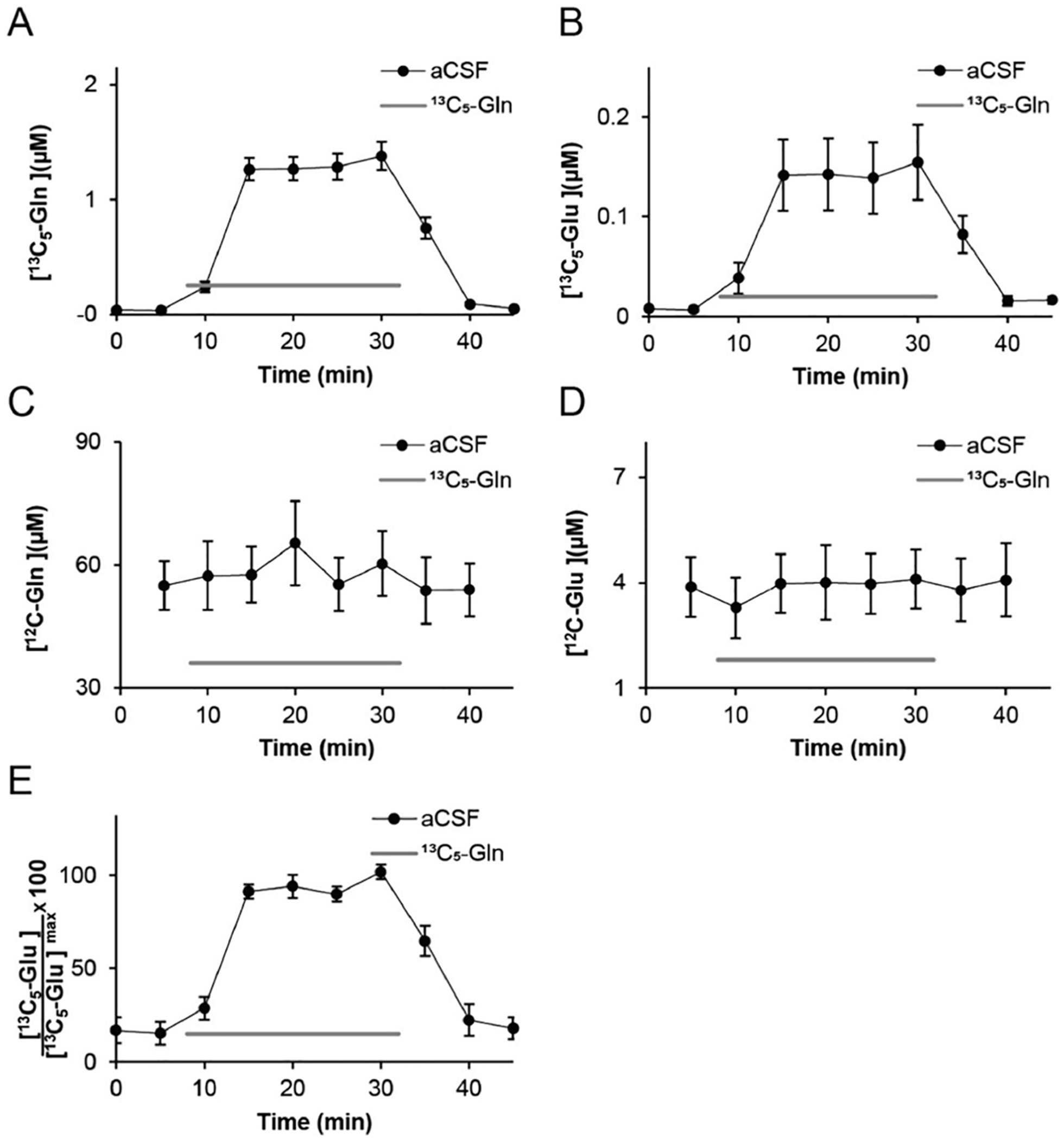

Figure 1.

Recovered concentrations (μM) of (A) 13C5-Gln, (B) 13C5-Glu, (C) 12C-Gln, and (D) 12C-Glu following infusion of 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (gray bar) into the microdialysis probe. (E) Normalized 13C5-Glu concentration from individual experiments. Each subject’s 13C5-Glu concentration was normalized to its maximal concentration reached during infusion of 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln, illustrating relative consistency across multiple infusion cycles (n = 11).

Figure 2.

Effect of Gln transport inhibitors on conversion of 13C-Gln to 13C-Glu. (A) The presence of 20 mM MEAIB in perfusion solution reduced the concentration of 13C5-Glu recovered in dialysate (open circles) compared to the aCSF control (filled circles) during infusion of 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (blank bar); (B) presence of 500 μM riluzole in perfusion solution reduced the concentration of 13C5-Glu recovered in dialysate (open circles) compared to the aCSF control (filled circles) during infusion of 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (gray bar). Data are average (n = 11 for A and n = 6 for B) with error bars showing ± SEM. Significantly different time points are indicated with *** for p ≤ 0.001, ** for p ≤ 0.01, and * for p ≤ 0.05.

2.3. Sample Derivatization and Analysis.

Each sample was derivatized with benzoyl chloride and analyzed as described previously.54 Briefly, samples were sequentially mixed with 100 mM sodium tetraborate, benzoyl chloride (2% in acetonitrile, v/v), and an internal standard in a 2:1:1:1 ratio. The internal standard consisted of standards labeled with 13C6-benzoyl chloride in 100 mM sodium tetraborate. The internal standard was diluted 1:100 in dimethyl sulfoxide and 1% formic acid (v/v). The samples were analyzed on a Waters UPLC with a Waters HSS T3 column (1 mm inner diameter × 100 mm long, with 1.8 μm particles). A Waters/Micromass Quattro Ultima triple quadrupole or an Agilent 6410 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer was used for detection. Mobile phase A was composed of 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.15% (v/v) formic acid in water. Mobile phase B was acetonitrile. The peak areas of each analyte were divided by the area of the internal standard for quantification.

2.4. Surgery.

All animal procedures were approved by the University Committee for the Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan. Male Sprague–Dawley rats were anesthetized with ketamine (65 mg/kg, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) and dexdomitor (0.25 mg/kg, Pfizer Animal Health, New York, NY) and placed in a stereotaxic frame. A burr hole was drilled +0.2 mm anterior and ±2.3 mm lateral from the bregma (Paxinos and Watson 2007). Additional burr holes were drilled for skull screws to hold the cap in place. The probes were lowered 3 mm from the top of the skull into the cortex through the burr hole. Dental cement (A-M Systems, Inc., Sequim, WA) was used to hold the probes in place. The day of the experiment, rats were lightly anesthetized in an isoflurane drop box. The microdialysis probes were attached to the syringes and perfused with aCSF at a flow rate of 1 μL/min. The rat was tethered to a Raturn instrument (Bioanalytical Systems, Inc., West Lafayette, IN).

2.5. Measuring 13C5-Glu Production during 13C5-Gln Infusion.

Solution perfused through the dialysis probe was switched from aCSF to 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln in aCSF using a four-port valve (Valco Instruments, Houston, TX) for 14 min, unless stated otherwise, and then switched back to aCSF. In some cases, a pharmacological agent was included in the solution. These were 2 μM TTX, 200 μM (1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (ACPD), or 200 μM (RS)-α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG, Tocris, Bristol, UK). If TTX, ACPD, or MCPG was tested, then they were perfused for 15 min prior to the 13C5-Gln switch and were also present during the 13C5-Gln infusion. For the 1 mM l-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid (PDC, Tocris) or high K+ treatment (75 mM), aCSF was perfused and the PDC or high K+ was perfused concurrently with the 13C5-Gln. Unless stated otherwise, samples were collected every 2 min. To evaluate the inhibition of the Gln transporter, 500 μM riluzole (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) or 20 mM α-(methylamino)isobutyric acid (MeAIB, Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) was perfused through the dialysis probe for 30 min prior to initiating the 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln switch. These inhibitors were also maintained throughout the subsequent 25 min 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln infusion. During the transporter inhibition experiments, samples were collected at 5 min intervals. For the tail pinch, aCSF containing 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln with and without 2 μM TTX was switched to the probe for 10 min prior to baseline collection. After three baseline fractions were collected, a binder clip was attached to the tail for 10 min. The clip was removed, and collection continued for an additional 14 min.

For testing the effect of minocycline treatment, animals were dosed via drinking water at 1 mg/mL for 2 weeks before measurement as described previously.55 Control animals were fed unadulterated water. Probes were implanted on the 10th day of treatment. For measurement, 13C5-Gln was infused as described above and comparisons of 13C5-Glu produced were made between these groups on fractions collected every 5 min.

2.6. Statistical Analysis.

Unless stated otherwise, values are reported as the mean with the standard error of the mean (SEM). For comparison of individual time points for 13C5-Glu produced with different drug treatments, paired t tests were performed. When comparing the aCSF and drug-treated production of 13C5-Glu, a linear mixed model regression was used to test the significance. SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for the mixed model regression. The rat identity was used as the subject, drug treatment was used as a factor, time was used as a covariate, and the measurement (i.e., % basal) was tested as the dependent variable.56 Results of these comparisons are reported as the overall effect.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Concentration of Glu and Gln in the Brain Extracellular Space.

In vivo calibration of a microdialysis probe is useful to correct for probe recovery and effects of the brain tissue on mass transport to the probe. We used a method that is based on infusing a stable isotope labeled (SIL) form of the analyte and measure its loss from the microdialysis probe.57–60 This loss is used to calculate the extraction fraction using

where is the concentration of the SIL compound infused into the probe and is the dialysate concentration measured at the outlet of the probe. The apparent extracellular concentration of the compound in the brain is

where is the measured concentration of the endogenous compound in dialysate.61,62 When infusing 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln, we recovered 1.73 ± 0.06 μM 13C5-Gln giving an Ed of 0.30 ± 0.03 and an extracellular concentration calculated as 179 ± 20 μM for Gln (n = 11). When infusing 5.0 μM 13C5-Glu, we recovered 3.5 ± 0.05 μM 13C5-Glu giving an Ed of 0.29 ± 0.01 and an extracellular concentration calculated as 9.4 ± 0.6 μM for Glu (n = 11).

3.2. Gln Is Rapidly Converted to Glu in the Brain.

Infusing 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln through the probe resulted in loss of 13C5-Gln into the brain so that the concentration in dialysate exiting the probe was 1.25 ± 0.1 μM (n = 11), Figure 1A. These experiments used different microdialysis probes with higher Ed than than those used for the original Ed calculation. We also found that 13C5-Glu was collected and reached a steady-state concentration of 144 ± 35 nM (n = 11) after starting the 13C5-Gln perfusion (Figure 1B). All experiments resulted in collection of 13C5-Glu despite some variability from subject to subject (see Figure SI 1 for individual traces). The variability could be reduced by normalizing to the maximal concentration observed for each subject (Figure 1E). The 13C5-Glu appeared with the 13C5-Gln implying that this Glu was formed and released within the temporal resolution of the measurement of 2–5 min (see Figure 1A,B and Figure SI 1). Once 13C5-Gln was removed from the probe, the 13C5-Glu signal declined to near baseline in the next fraction, showing rapid dissipation, e.g., by diffusion, reuptake, or metabolism, of the labeled Glu.

The concentrations of 13C5-Gln added to the brain and 13C5-Glu recovered were less than 2% of their estimated in vivo concentrations. This concentration appeared to be low enough to not alter endogenous neurochemistry or cause irreversible effects. For example, infusion of 13C5-Gln did not affect endogenous concentrations of Gln or Glu (Figure 1C,D) and the concentration of 13C5-Glu produced from 13C5-Gln was unchanged between sequential infusions in the same subject (Figure SI 2). The 13C5-Glu concentration remained stable for up to 60 min (Figure SI 4A), the longest time tested.

3.3. Gln Transporter Inhibition.

To determine if the 13C5-Glu produced could come from 13C5-Gln transported into neurons, as expected for the Glu-Gln shuttle, we examined the effect of Gln transporter inhibition. The complete mechanisms for Gln transport into neurons are still not resolved, but the system A transporter SNAT1 has been implicated. However, SNAT1 has been shown to be localized at cell bodies and dendrites but not axons or synapses in cortical neurons suggesting a lesser role for this transporter in Gln-Glu cycling to support neurotransmission.63 Other studies have suggested that system A transporters important for transporting Gln into neurons for metabololic purposes may not support Glu-Gln cycling for neurotransmitter release.64 An activity-dependent, functional Gln transporter system has also been identified.65 To test if the 13C5-Glu produced was due to 13C5-Gln transported into neurons, we measured 13C5-Glu produced when the dialysis probe was infused with 20 mM 2-(methylamino)isobutyric acid (MeAIB, a transportable inhibitor of SNAT1/2), and 500 μM riluzole, an inhibitor of activity-dependent Gln transport in neurons.64,65 As shown in Figure 2, MeAIB reduced the measured 13C5-Glu by 33 ± 8% (p ≤ 0.05 for time points 15–30, n = 11) and riluzole reduced it by 58 ± 3% (p ≤ 0.05 for time points 10–30, n = 8). MeAIB did not affect endogenous Glu, endogenous Gln, or 13C5-Gln (Figure SI 3). Riluzole did not affect any form of Gln but suppressed endogenous Glu by 33 ± 4% (p ≤ 0.05 for 8 time points, n = 8, see Figure SI 3).

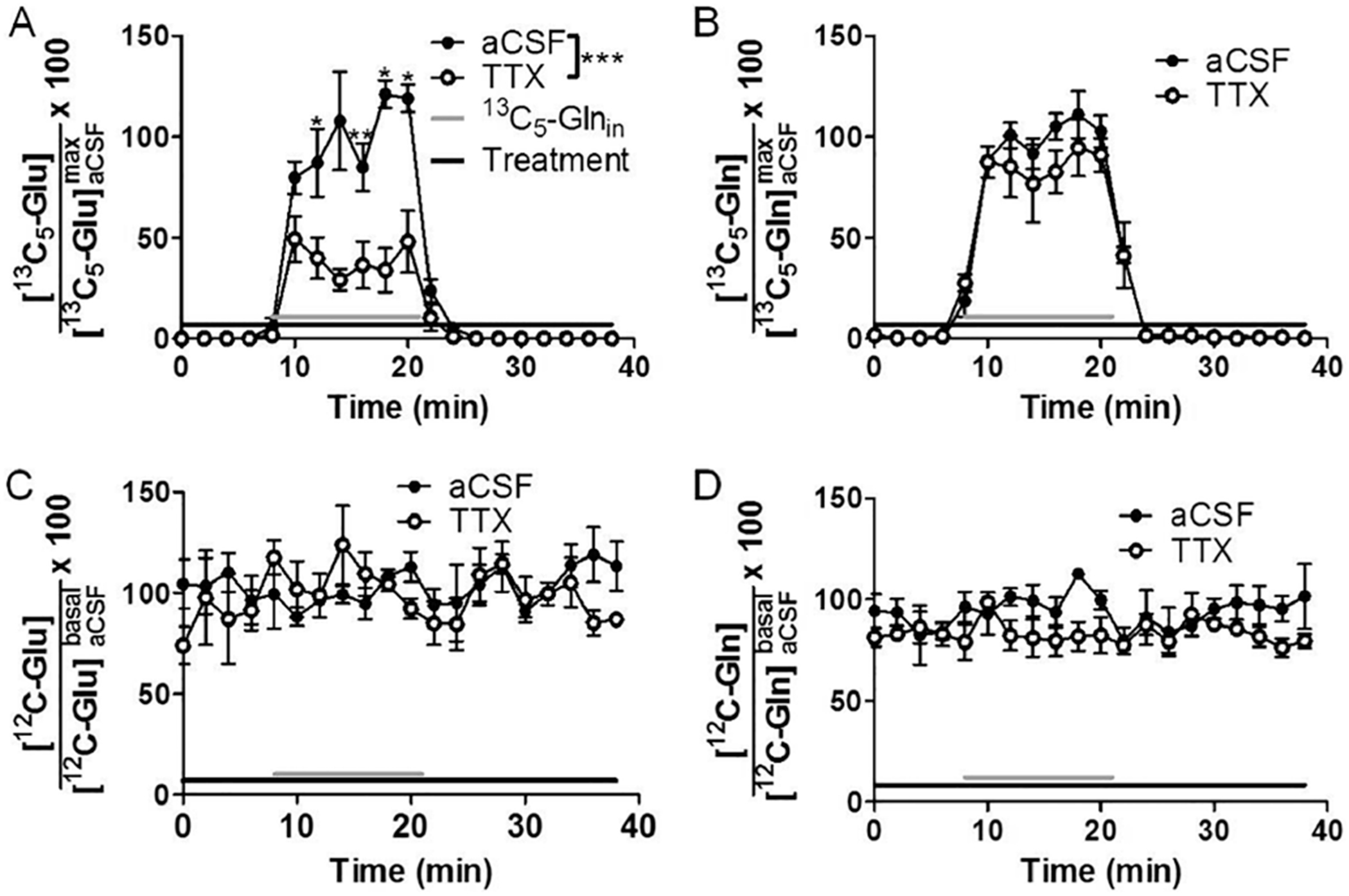

3.4. 13C5-Glu Concentration Is Regulated by TTX and mGluR.

We asked whether the concentration of 13C5-Glu was altered by treatments that would modify neuronal release. Infusion of 2 μM TTX prior to and during 13C5-Gln infusion suppressed the release of 13C5-Glu by 62 ± 7% (p ≤ 0.001 for all data during 13C5-Gln infusion, n = 3) as shown in Figure 3. Use of a higher concentration of TTX (50 μM) did not further reduce the 13C5-Glu concentration. Unlike 13C5-Glu, the endogenous 12C-Glu was unchanged by TTX treatment (Figure 3). This latter result agrees with other studies that have found little effect on dialysate Glu with local TTX treatment.22–27 TTX also did not affect endogenous Gln (Figure 3B,D). If TTX was applied 60 min after beginning 13C5-Gln infusion (Figure SI 4A), then the 13C5-Glu was reduced by 34 ± 3% (n = 4, p ≤ 0.001 for all data). This decrease, although smaller, was not statistically different from that induced by TTX after 14 min of 13C5-Gln infusion. Gln was unaffected by the longer treatment (Figure SI 4B).

Figure 3.

(A) The presence of 2 μM TTX (black bar) in perfusion solution reduced the concentration of 13C5-Glu recovered in dialysate (filled circles) compared to no TTX (open circles) during infusion of 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (gray bar). For the same experiment, TTX did not affect the dialysate concentration of 13C5-Gln (B), 12C-Glu (C), or 12C-Gln (D). Data are expressed as concentration in dialysate relative to maximal for each panel. The concentrations of 13C5-Glu and 13C5-Gln for each infusion were normalized to the mean concentrations of 13C5-Glu and 13C5-Gln, respectively, of all time points during the first infusion (labeled with subscript “max”), which reached a steady-state maximum. The 12C-Glu and 12C-Gln were normalized to basal levels. Data are average (n = 3 for all panels) with error bars showing ±SEM. Significantly different time points from TTX to without are indicated with *** for p ≤ 0.001, ** for p ≤ 0.01, and * for p ≤ 0.05.

The effect of TTX on 13C5-Glu detected was dependent on the concentration of 13C5-Gln infused. If 50 μM 13C5-Gln was infused instead of 2.5 μM, we collected 650 ± 50 nM 13C5-Glu (n = 3); however, this concentration was not suppressed by TTX infusions (Figure SI 4C). Other measured compounds are also not affected (Figure SI 4D–F).

Glu release can be modulated by metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR).66,67 In previous work, mGluR agonists have decreased basal Glu concentrations in the hippocampus,68 nucleus accumbens,69 and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC);29 however, other studies have shown that mGluR agonists and antagonists have little effect on basal Glu measured by microdialysis.31,70,71 We found that the 13C5-Glu detected was reduced by 59 ± 9% (p ≤ 0.001, n = 4) by ACPD, a group I/II mGluR agonist (Figure 4A). In contrast, infusion of 200 μM ACPD had no effect on 13C5-Gln or endogenous Glu and Gln (Figure 4B-D, n = 4). Simultaneous infusion of 200 μM MCPG (a group I/II mGluR antagonist) with ACPD completely blocked the effect of ACPD on 13C5-Glu (Figure 4E, n = 6) without altering the response to 13C5-Gln (Figure 4F, n = 6). MCPG infusion alone caused a small average increase in 13C5-Glu to 124 ± 17% (n = 3) relative to 13C5-Glu produced with aCSF treatment when 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln was infused through the probe, an effect that did not reach statistical significance for the small sample set (Figure 4G). MCPG did not affect 13C5-Gln (Figure 4H).

Figure 4.

(A) The presence of 200 μM ACPD (black bar) in perfusion solution reduced the concentration of 13C5-Glu recovered in dialysate (open circles) compared to without ACPD (filled circles) during infusion of 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (gray bar). The overall decrease was 59% (p ≤ 0.001, n = 4). (B) For the same experiment, ACPD did not affect the dialysate concentration of 13C5-Gln (n = 4), (C) 12C-Glu (n = 4), or (D) 12C-Gln (n = 4). (E) The effect of ACPD on 13C5-Glu was reversed by addition of 200 μM MCPG to infusion solution (black bar, n = 6). (F) Combined ACPD and MCPG had no effect on 13C5-Gln compared to aCSF (n = 6). (G) During infusion of 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (gray bar), the presence of 200 μM MCPG (black bar) in perfusion solution had no statistically significant effect on 13C5-Glu (n = 3) or (H) 13C5-Gln (n = 3) recovered in dialysate (open circles) compared to infusion of 13C5-Gln without MCPG (filled circles). The concentrations of 13C5-Glu and 13C5-Gln for each infusion were normalized to the mean concentrations of 13C5-Glu and 13C5-Gln, respectively, of all time points during the first infusion (labeled with subscript “max”), which reached a steady-state maximum. The 12C-Glu and 12C-Gln were normalized to basal levels. Data are average with error bars showing ±SEM. Significantly different time points from the control are indicated with ** for p ≤ 0.01 and * for p ≤ 0.05.

3.5. Uptake Inhibition.

PDC is a transportable Glu uptake inhibitor that significantly raises extracellular Glu concentration by both blocking reuptake and by being exchanged with intracellular Glu.72,73 Addition of 1 mM PDC to the dialysis perfusion fluid with 13C5-Gln increased 12C-Glu 342 ± 76% (p ≤ 0.001, n = 3) and 13C5-Glu 173 ± 8% (p ≤ 0.01, n = 3) relative to that without PDC. PDC did not affect 13C5-Gln or endogenous Gln (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(A) Infusion of 1 mM PDC (black bar) increased the dialysate concentration of 13C5-Glu (open black circles) to 173 ± 8% (p < 0.01) relative to aCSF treatment (filled black circles) while infusing 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (gray bar). (B) PDC had no effect on the loss of 13C5-Gln through the probe membrane. (C) During the same experiment, PDC increased [12C-Glu] by 342 ± 76% (p < 0.001) relative to no PDC perfused through the probe. (D) PDC had no effect on [12C-Gln]. The concentrations of 13C5-Glu and 13C5-Gln for each infusion were normalized to the mean concentrations of 13C5-Glu and 13C5-Gln, respectively, of all time points during the first infusion, which reached a steady-state maximum. Data are average (n = 4 for all panels) with error bars showing ±SEM. Significantly different time points from control are indicated with *** for p ≤ 0.001, ** for p ≤ 0.01, and * for p ≤ 0.05.

3.6. Stimulated Release of Glu.

We also investigated how different stimuli affected the Glu concentration. Elevated K+ concentration is expected to depolarize neurons and evoke release; however, it may also cause the release of Glu from astrocytes.8 Addition of 75 mM K+ to the dialysis perfusion fluid (n = 4) while 13C5-Gln was also infused increased only 12C-Glu (160 ± 20%, p < 0.05) with no increase in 13C5-Glu relative to that with physiological K+. The high K+ also caused an increase in GABA by 2270 ± 400% (p < 0.01) and decreased 12C-Gln to 48 ± 0.6% (p < 0.001) of basal concentration in the same experiments (Figure 6). The high K+ had no effect on [13C5-Gln]out compared with aCSF treatment.

Figure 6.

Infusion of 75 mM K+ aCSF (black bar) had no effect on the dialysate concentration of 13C5-Glu (A) or 13C5-Gln (B) relative to normal aCSF while infusing 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (gray bar). The high K+ treatment evoked (C) an increase in [12C-Glu] (p < 0.05), (D) a decrease in endogenous [12C-Gln] (p < 0.001), and (E) an increase in endogenous [12C-GABA] (p < 0.01). The concentrations of 13C5-Glu and 13C5-Gln were normalized to the average concentrations of each during the 13C5-Gln infusion with only aCSF, which reached a steady-state maximum. Data are averages (n = 4 for all panels) with error bars showing ±SEM. Significantly different individual time points from the control are indicated with *** for p ≤ 0.001, ** for p ≤ 0.01, and * for p ≤ 0.05.

Stressors such as tail pinch have previously been reported to increase extracellular Glu in the mPFC.29,33,35 Others have found that a stress response is highly variable.26 In our study, tail pinch had no effect on endogenous 12C-Glu or 12C-Gln in this region of the motor cortex; however, tail pinch did increase 13C5-Glu following infusion of 13C5-Gln by 155 ± 14% (p ≤ 0.05 for all data, 4 time points had p ≤ 0.05, n = 4). This increase was abolished by TTX infusion (p ≤ 0.05, n = 3; Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of tail pinch on Glu measurements. (A) Tail pinch (gray solid bar, n = 4) evoked a 155 ± 14% increase (p < 0.05) in dialysate concentration of 13C5-Glu (filled black circles) while infusing 2.5 μM 13C5-Gln (dashed line). This increase was blocked in the presence of TTX (open circles, n = 3). For the same experiment, no overall change in the [13C5-Gln]out (B), [12C-Glu]out, (C) or [12C-Gln]out (D) was observed. The concentrations of 13C5-Glu and 13C5-Gln were normalized to the average concentrations of each prior to the tail pinch. Data are averages (n = 4 for tail pinch, n = 3 for TTX) with error bars showing ±SEM. Significantly different time points from the control are indicated with * for p ≤ 0.05.

3.7. Effect of Minocycline on 13C-Glu Production.

Although the Glu-Gln shuttle relies on Gln conversion to Glu by glutaminase in neurons, some studies have found glutaminase in glial cells.74–76 Further, it is possible that activated microglia may also contribute some conversion of Gln to Glu. It has been shown that activated microglia (in culture) can express glutaminase and produce Glu, which can then be released from these cells.77,78 Insertion of microdialysis probes can activate microglia;79 therefore, an additional possible source of Glu-Gln conversion is activated microglia. To determine if such a process contributed to the observed production of 13C-Glu from 13C-Gln, we treated rats with minocycline using a regimen that has been shown to inhibit microglial activation.55,80,81 We found that this treatment tended to increase the amount of 13C-Glu detected but with only one time point reaching statistical significance as shown in Figure SI 5A. The average increase across all time points was 77 ± 23% (n = 10 from the treatment group and 11 from untreated controls). Interestingly, endogenous Glu was reduced in the minocycline-treated rates (Figure SI 5C) by 75 ± 3% (p < 0.05 for all data, n = 10 from the treatment group, 11 from untreated controls). The source of this decrease is not known but could relate to inhibition of microglia that produce some of the 12C-Glu normally detected in the dialysate. Gln was minimally affected by minocycline treatment (Figure SI 5B,D). A caveat to these results is that minocycline was shown to selectively inhibit M1 activation (proinflammatory) and not inhibit anti-inflammatory functions.82

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. 13C5-Glu Is Enriched in Neuronal Activity-Dependent Glutamate.

Our objective in perfusing a low concentration of 13C5-Gln was to use the Glu-Gln shuttle to isolate a neuronal component of Glu from the large, non-neuronal Glu background normally detected in the extracellular space. Figure 8 illustrates the sources of Glu sampled by microdialysis and the concept envisioned. Endogenous Glu released from neurons is primarily taken up by astrocytes, so that little Glu directly released by neurons can be sampled. A larger component may come from astrocytic release and potentially other sources. When 13C5-Gln is infused through the probe, it can be converted to 13C5-Glu by neurons near the probe. Under these conditions, any 13C5-Glu detected, at least initially, must be derived from exogenous 13C5-Gln. Because neurons convert Gln to Glu in the brain, this 13C5-Glu is expected to have been, at least in part, released from the neurons. We performed experiments to assess whether the detected 13C-Glu was consistent with this expected source.

Figure 8.

Illustration of sources of Glu sampled by a microdialysis probe. (A) Endogenous Glu is released by neurons and taken up by astrocytes. Little directly from the neurons reaches the dialysis probe (dashed line). Astrocytes may be a source of larger concentrations of Glu. (B) With 13C5-Gln (red) infused through the probe, it can be taken up and selectively converted to 13C5-Glu (light blue). Once released, it follows the same fate as endogenous Glu; however, the background is low allowing the neuronal fraction to be detected.

A first step for the production of Glu from Gln is neuronal uptake of Gln. The results with SNAT1/2 inhibitors support the idea that the 13C5-Glu at least partially results from 13C5-Gln transported into neurons by system A transporter. MeAIB was partially effective at reducing 13C5-Glu production, but riluzole produced a more robust suppression of 13C5-Glu.

The only partial inhibition of 13C5-Glu release by MeAIB may be due to incomplete inhibition of SNAT1 by MeAIB using this delivery method at the times used, perhaps due to competition from endogenous amino acids. Supporting this idea are previous microdialysis studies that have monitored increases in endogenous Gln as a proxy for blockade of Gln uptake in response to perfusion of MeAIB through a dialysis probe in vivo. One study using 50 mM MeAIB (2.5-fold greater than that used here) showed that Gln increased slowly over time and took 2 h to fully increase to 180% of basal but at 30 min was only 120% (estimated from Figure 2).40 In another study, an infusion of 20 mM MeAIB did not significantly increase Gln at 30 min.83 We found no increase in endogenous Gln with MeAIB used here. Taken together, these results suggest that at the lower concentrations and shorter time used in our study, we may have not fully blocked Gln transport i.e., enough to significantly alter basal Gln. A second factor that may play a role in the inability of 20 mM MeAIB to completely block 13C-Glu production from 13C-Gln is the presence of other non-MeAIB-sensitive Gln transporters. For example, in cortical slices, it was shown that while Gln transport activity was necessary to maintain Glu neurotransmitter pools, MeAIB did not block the filling of this pool, but rather, MeAIB was more potent at blocking a metabolic Gln pool that was less active.64

500 μM riluzole was a more potent inhibitor of extracellular 13C5-Glu production from 13C5-Gln than MeAIB. Riluzole derivatives attenuate an activity-dependent Gln transport system65 via a noncompetitive mechanism.84 These features may allow it to be more effective at inhibiting Gln transport involved in producing Glu than MeAIB. Riluzole also has several other targets including Na channels84 that may contribute to the effects on 13C-Glu detected here. The multiple targets and effects of riluzole likely contributed to its ability to reduce both 13C5-Glu and endogenous Glu.85–87

We also performed pharmacological experiments that were aimed at manipulating neuronal release to test the hypothesis that 13C5-Glu detected was released from neurons. The detected concentration of 13C5-Glu is sensitive to TTX and the activation of mGluR. This latter effect was blocked by mGluR antagonists. mGluR antagonists alone produced only a small increase in the level of 13C5-Glu. The results from mGluR agonists and antagonists are consistent with modest neuronal overflow of 13C5-Glu under basal conditions with control by autoreceptors, which is expected for an activity-dependent mechanism for Glu release. Taken together, these pharmacological experiments support the hypothesis that the detected 13C5-Glu is at least partially due to its release from neurons. With respect to TTX, a caveat is that it is possible that the 13C5-Glu detected comes from a source that is only dependent on neuronal activity rather than directly released from neurons; however, the TTX sensitivity of glutamatergic neurons supports the notion of neuronal release as the most parsimonious explanation. The incomplete ablation of 13C5-Glu with TTX treatment may be due to incomplete blockage of TTX from the delivery method used, or it may be an indicator of another source of 13C5-Glu such as a glial source associated with glutaminase activity in glia.74–76 Therefore, this method allows detection of an extracellular pool of Glu that is enriched in Glu derived from neurons under “basal conditions”, i.e., without specific behavioral, drug, or electrical activation of neurons. In contrast, endogenous 12C-Glu is unaffected by TTX or mGluR treatments. We conclude, like others, that the basal endogenous 12C-Glu must have a primarily non-neuronal source. This is not to say that there is no neuronal Glu detected, but rather, it is a small fraction of what is detected. Based on prior work, we expect the 12C-Glu to be at least partially astrocytic. Thus, the 13C5-Glu and 12C-Glu have different sources, one primarily neuronal (13C) and the other primarily non-neuronal (12C). These results show that local metabolic labeling with 13C5-Gln allows probing of neuronally derived Glu, which is partially independent of background Glu.

A previous study used intravenous infusion of 13C-labeled glucose and detected resulting 13C-Glu using both NMR and microdialysis.52 Based on fractions labeled and the rate of labeling, that work concluded that the basal Glu detected using microdialysis was primarily that released from neurons. This work did not test for pharmacological and stimulated changes in Glu, however, leaving open the question of the inability to manipulate such concentrations pharmacologically as expected for neuronal release. It would be interesting to further use both glucose and Gln precursors to determine whether they lead to different pools of extracellular Glu.

The results reported here support the conclusion that detected 13C5-Glu is enriched with Glu released from neurons. The presence of glutaminase in glia74,76 and activated microglia77,78 suggests that they may be another possible source of 13C5-Glu. The potential for glial production and release of Glu via Gln may contribute to incomplete inhibition of 13C-Glu detection in experiments such as the TTX treatment. Inhibition of microglial activation by minocycline did not decrease the amount of 13C5-Glu collected but increased it (Figure SI 5). These results are inconsistent, with activated microglia serving as a source of 13C5-Gln to 13C5-Glu conversion. It is possible that at longer times after probe insertion, a microglial source would become apparent since microglial activation evolves over time after a probe insertion.

4.2. Use of Metabolic Labeling for Detection of 13C5-Glu.

The results support the hypothesis that the infusion of 13C5-Gln allows the detection of 13C5-Glu that is enriched in neuronal Glu relative to the background. We speculate that the use of isotopically labeled Gln allows detection of Glu that is newly made and immediately released near the probe enabling distinction from the large background Glu due to the concentration gradients formed during infusion. When 13C5-Gln is infused, it will diffuse away from the probe, forming a concentration gradient with the highest concentration at the probe surface and decreasing with the distance from the probe. The 13C5-Glu formed likely follows this trend. Therefore, the highest concentration is near the probe surface for recovery. In contrast, endogenous 12C-Glu and 12C-Gln will have concentration gradients that decrease from the tissue to the probe surface. This difference may account for the observation that the ratio of 13C-Glu/13C-Gln in the dialysate is 11% (from Figure 1) and only 7% for endogenous Glu/Gln. That is, the probe is able to recover a higher fraction of the Gln converted to Glu for the infused forms. Further, if 13C-Glu is formed preferentially near the probe, it is more likely to be captured immediately after release from a neuron that endogenous Glu formed farther away. Detailed modeling would be useful in addressing these hypotheses.

The ability to discern this neuronal pool, however, is dependent upon the concentration of 13C5-Gln infused. Infusion of a higher concentration of 13C5-Gln (50 μM) resulted in no detectable decreases of 13C5-Glu with TTX treatment. This lack of TTX sensitivity is similar to what is observed for endogenous Gln. The higher Gln concentrations appear to access additional, non-TTX-sensitive processes of Gln to Glu conversion and release. This source of Glu apparently overwhelms the neuronal source when high concentrations of Gln are available. The mechanism underlying this effect is unclear, but it indicates that the high in vivo concentration of endogenous Gln may yield a similar effect, resulting in a large background of extracellular Glu that is not TTX-sensitive.

4.3. Differential Effects of Stimuli.

The use of 13C5-Gln allows for differentiation of how perturbations modulate different sources of Glu. Our results show that a stressor, tail pinch, evokes release of 13C5-Glu and that the release is blocked by TTX. In contrast, the 12C-Glu was relatively unaffected. We conclude that the Glu released is due to neuronal activation, with little response by astrocytes. A few previous studies have shown that this stimulus can evoke release of endogenous Glu in the mPFC29,33,35,88 that is TTX-sensitive. Those prior results indicate a significant increase in neuronal Glu evoked by tail pinch over the relatively high background. Our results indicate that in the motor cortex, the neuronal response is much more muted and would not be detectable by recording only endogenous Glu.

K+ evoked release of only 12C-Glu even though in principle K+ would depolarize neurons to evoke release. Astrocytes can release Glu in response to elevated K+; therefore, the increase in 12C-Glu is consistent with this mechanism.8 The lack of a 13C5-Glu or neuronal component is surprising given the known effects of depolarization on neuronal release; however, this finding is in agreement with a previous study, which showed that in cortical tissues, elevated K+ reduced glutamatergic miniexcitatory postsynaptic currents and potentials.89 This observation was due to the inhibition of Glu transporters by K+ and subsequent activation of mGluR to inhibit neuronal release. GABA may also play a role. In a previous study, elevated endogenous GABA concentrations were shown to attenuate the Glu-Gln cycle.90 We observed that GABA was increased 2270 ± 400% with 75 mM K+ compared to the 160 ± 20% for 12C-Glu (Figure 6). Because GABA increases substantially with K+, the activity of the Glu-Gln cycle may have been reduced, which would affect the availability of 13C5-Glu for release. Supporting this idea, we also found that K+ stimulation reduced 12C-Gln to 54 ± 1% of the basal levels. Additionally, the high concentration of GABA released may act directly on neurons to inhibit Glu release. Finally, this effect could also reflect an instance of depolarization-induced suppression of excitation mediated by endogenous cannabinoids acting on CB1 receptors91,92 or activation of mGluR.93

PDC is a transportable inhibitor and, therefore, could affect extracellular Glu in two ways. One is to allow the spread of Glu released from neurons or glial cells. A second action is the release of Glu due to exchange of the drug for intracellular Glu. Since Glu is primarily taken up by glial cells, we would expect that the exchange mechanism would cause glial cell release because they express the majority of EAAT. In agreement with these expectations, we saw a considerable increase in both 13C5-Glu and 12C-Glu with PDC treatment (Figure 5).

4.4. Other Implications.

These results provide evidence of two differentially regulated sources of Glu within the brain extracellular space. One source is detected as endogenous Glu and is likely at least partially due to the astrocytic release. The other source is detected as 13C5-Glu derived from 13C5-Gln and appears to be released from neurons. Detection of 13C5-Glu suggests that a small amount of Glu can leak from the synapses. The clear distinction in sources and regulation of Glu support the concept of compartmentalized Glu.94

The ability to detect neuronal release of Glu without any stimulation by adding a small amount of Gln also supports the idea that Glu neurons in the vicinity of the probe are functional because they take up Gln, convert it to Glu, and release it in a TTX-sensitive and mGluR-modulated manner. Thus, despite the physical effects of probe insertion, the probe can monitor regulated Glu neuron activity, as established for other neurotransmitters. These results do not rule out the possibility that some endogenous Glu that is detected normally by microdialysis is artifactual.

The results also show that the Glu-Gln shuttle operates on a short timescale. 13C5-Glu was released within 2 min of supplying 13C5-Gln showing that this new Glu is rapidly used by neurons for signaling. The ready manipulation of Glu by Gln supports the idea that this may be a route for astrocytes to influence neuronal signaling; i.e., changes in metabolic conversion of Glu to Gln or release of Gln could alter Glu signaling.

In conclusion, these experiments have revealed that exogenously applied Gln is rapidly converted to Glu. At least some of the Glu is released from neurons and enters the extracellular space sampled by microdialysis. The newly formed Glu shows pharmacological and physiological changes different from those of endogenous Glu. The results support the concept of different pools of Glu, one dominated by neuronal release and the other by release from different sources such as astrocytes. They also demonstrate a novel technique for detecting the neuronal release of Glu by microdialysis. While these observations support the potential of this approach to follow Glu neuronal release, further study is required to better understand if the concentration gradients are important and why at longer times and higher concentrations of 13C5-Gln infusion, the effect is lessened or absent.

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acschemneuro.5c00518.

Individual traces for each compound measured during 13C5-Gln infusion as dialysate concentration; data for repeated infusions of 13C5-Gln; data for Glu, Gln, and 13C-Gln during treatment with MeAIB and riluzole; effect of Gln infusion conditions on TTX sensitivity of recovered 13C5-Glu; effect of pretreatment with minocycline on all measured compounds (PDF)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH R37 EB003320 and R01 NS128522. We thank Caitlin Cain for creating the table of content graphic.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACPD

(1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid

- aCSF

artificial cerebral spinal fluid

- EAATs

excitatory amino acid transporters

- E d

extraction fraction

- Glu

glutamate

- Gln

glutamine

- MCPG

(RS)-α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine

- MeAIB

α-(methylamino)isobutyric acid

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- SIL

stable isotope labeled

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- PDC

l-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.5c00518

Contributor Information

Neil D. Hershey, Departments of Chemistry and Pharmacology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1055, United States

Pavlo Popov, Departments of Chemistry and Pharmacology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1055, United States.

Nick Oliver, Departments of Chemistry and Pharmacology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1055, United States.

Colleen E. Dugan, Departments of Chemistry and Pharmacology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1055, United States

Robert T. Kennedy, Departments of Chemistry and Pharmacology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1055, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Araque A; Parpura V; Sanzgiri RP; Haydon PG Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends in Neurosciences 1999, 22 (5), 208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Del Arco A; Segovia G; Fuxe K; Mora F Changes in dialysate concentrations of glutamate and GABA in the brain: an index of volume transmission mediated actions? Journal of Neurochemistry 2003, 85 (1), 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Haydon PG Glia: Listening and talking to the synapse. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2001, 2 (3), 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Machado-Vieira R; Manji HK; Zarate CA The Role of the Tripartite Glutamatergic Synapse in the Pathophysiology and Therapeutics of Mood Disorders. Neuroscientist 2009, 15 (5), 525–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Clements JD; Lester RAJ; Tong G; Jahr CE; Westbrook GL The time course of glutamate in the synaptic cleft. Science 1992, 258 (5087), 1498–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Rusakov DA The role of perisynaptic glial sheaths in glutamate spillover and extracellular Ca2+ depletion. Biophys. J 2001, 81 (4), 1947–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Baker DA; Xi ZX; Shen H; Swanson CJ; Kalivas PW The origin and neuronal function of in vivo nonsynaptic glutamate. J. Neurosci 2002, 22 (20), 9134–9141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yaguchi T; Nishizaki T Extracellular High K+ Stimulates Vesicular Glutamate Release From Astrocytes by Activating Voltage-Dependent Calcium Channels. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2010, 225 (2), 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zhang Q; Pangrsic T; Kreft M; Krzan M; Li NZ; Sul JY; Halassa M; Van Bockstaele E; Zorec R; Haydon PG Fusion-related release of glutamate from astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279 (13), 12724–12733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sasaki Y; Takimoto M; Oda K; Fruh T; Takai M; Okada T; Hori S Endothelin evokes efflux of glutamate in cultures of rat astrocytes. Journal of Neurochemistry 1997, 68 (5), 2194–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Perea G; Araque A Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science 2007, 317 (5841), 1083–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Danbolt NC Glutamate uptake. Progress in Neurobiology 2001, 65 (1), 1–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Barnett NL; Pow DV; Robinson SR Inhibition of Muller cell glutamine synthetase rapidly impairs the retinal response to light. Glia 2000, 30 (1), 64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Gibbs ME; Odowd BS; Hertz L; Robinson SR; Sedman GL; Ng KT Inhibition of glutamine synthetase activity prevents memory consolidation. Cognit. Brain Res 1996, 4 (1), 5764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Laake JH; Slyngstad TA; Haug FMS; Ottersen OP Glutamine from glial-cells is essential for the maintenance of the nerve-terminal pool of glutamate - immunogold evidence from hippocampal slice cultures. Journal of Neurochemistry 1995, 65 (2), 871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Pow DV; Robinson SR Glutamate in some retinal neurons is derived solely from glia. Neuroscience 1994, 60 (2), 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Sibson NR; Mason GF; Shen J; Cline GW; Herskovits AZ; Wall JEM; Behar KL; Rothman DL; Shulman RG In vivo C-13 NMR measurement of neurotransmitter glutamate cycling, anaplerosis and TCA cycle flux in rat brain during 2-C-13 glucose infusion. Journal of Neurochemistry 2001, 76 (4), 975–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Carboni S; Rossetti ZL Increased extracellular glutamate in rat prefrontal cortex: movement artifact contribution. Brain Res. 2001, 890 (1), 189–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ding ZM; Ingraham CM; Hauser SR; Lasek AW; Bell RL; McBride WJ Reduced Levels of mGlu2 Receptors within the Prelimbic Cortex Are Not Associated with Elevated Glutamate Transmission or High Alcohol Drinking. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research 2017, 41 (11), 1896–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Miele M; Berners M; Boutelle MG; Kusakabe H; Fillenz M The determination of the extracellular concentration of brain glutamate using quantitative microdialysis. Brain Res. 1996, 707 (1), 131–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Touret M; Parrot S; Denoroy L; Belin MF; Didier-Bazes M Glutamatergic alterations in the cortex of genetic absence epilepsy rats. BMC Neurosci. 2007, 8, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Miele M; Boutelle MG; Fillenz M The source of physiologically stimulated glutamate efflux from the striatum of conscious rats. Journal of Physiology-London 1996, 497 (3), 745–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Oldenziel WH; Dijkstra G; Cremers T; Westerink BHC In vivo monitoring of extracellular glutamate in the brain with a microsensor. Brain Res. 2006, 1118, 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Paulsen RE; Fonnum F Role of glial-cells for the basal and ca-2+-dependent k+-evoked release of transmitter amino-acids investigated by microdialysis. Journal of Neurochemistry 1989, 52 (6), 1823–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Shiraishi M; Kamiyama Y; Huttemeier PC; Benveniste H Extracellular glutamate and dopamine measured by microdialysis in the rat striatum during blockade of synaptic transmission in anesthetized and awake rats. Brain Res. 1997, 759 (2), 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Timmerman W; Westerink BHC Brain microdialysis of GABA and glutamate: What does it signify? Synapse 1997, 27 (3), 242–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).van der Zeyden M; Oldenziel WH; Rea K; Cremers TI; Westerink BH Microdialysis of GABA and glutamate: Analysis, interpretation and comparison with microsensors. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav 2008, 90 (2), 135–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Day BK; Pomerleau F; Burmeister JJ; Huettl P; Gerhardt GA Microelectrode array studies of basal and potassium-evoked release of L-glutamate in the anesthetized rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry 2006, 96 (6), 1626–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hascup ER; Hascup KN; Stephens M; Pomerleau F; Huettl P; Gratton A; Gerhardt GA Rapid microelectrode measurements and the origin and regulation of extracellular glutamate in rat prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurochemistry 2010, 115 (6), 1608–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Vasylieva N; Maucler C; Meiller A; Viscogliosi H; Lieutaud T; Barbier D; Marinesco S Immobilization Method to Preserve Enzyme Specificity in Biosensors: Consequences for Brain Glutamate Detection. Anal. Chem 2013, 85 (4), 2507–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lada MW; Vickroy TW; Kennedy RT Evidence for neuronal origin and metabotropic receptor-mediated regulation of extracellular glutamate and aspartate in rat striatum in vivo following electrical stimulation of the prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neurochemistry 1998, 70 (2), 617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).LaLumiere RT; Kalivas PW Glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens core is necessary for heroin seeking. J. Neurosci 2008, 28 (12), 3170–3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lupinsky D; Moquin L; Gratton A Interhemispheric Regulation of the Medial Prefrontal Cortical Glutamate Stress Response in Rats. J. Neurosci 2010, 30 (22), 7624–7633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Moghaddam B Stress preferentially increases extraneuronal levels of excitatory amino-acids in the prefrontal cortex - comparison to hippocampus and basal ganglia. Journal of Neurochemistry 1993, 60 (5), 1650–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Rutherford EC; Pomerleau F; Huettl P; Stromberg I; Gerhardt GA Chronic second-by-second measures of L-glutamate in the central nervous system of freely moving rats. Journal of Neurochemistry 2007, 102 (3), 712–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Scanziani M; Salin PA; Vogt KE; Malenka RC; Nicoll RA Use-dependent increases in glutamate concentration activate presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature 1997, 385 (6617), 630–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kalivas PW Behaviorally relevant measures of glutamate transmission? Estimation of in-vivo neurotransmitter release by brain microdialysis: The issue of validity - Commentary. Behav. Pharmacol 1996, 7 (7), 658–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wolf ME; Xue CJ; Li Y; Wavak D Amphetamine increases glutamate efflux in the rat ventral tegmental area by a mechanism involving glutamate transporters and reactive oxygen species. Journal of Neurochemistry 2000, 75 (4), 1634–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kanamori K; Kondrat RW; Ross BD 13C enrichment of extracellular neurotransmitter glutamate in rat brain - Combined mass spectrometry and NMR studies of neurotransmitter turnover and uptake into glia in vivo. Cell. Mol. Biol 2003, 49 (5), 819–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kanamori K; Ross BD Quantitative determination of extracellular glutamine concentration in rat brain, and its elevation in vivo by system A transport inhibitor, alpha-(methylamino)isobutyrate. Journal of Neurochemistry 2004, 90 (1), 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kanamori K; Ross BD Suppression of glial glutamine release to the extracellular fluid studied in vivo by NMR and microdialysis in hyperammonemic rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry 2005, 94 (1), 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Kanamori K; Ross BD Kinetics of glial glutamine efflux and the mechanism of neuronal uptake studied in vivo in mildly hyperammonemic rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry 2006, 99 (4), 1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bachelard H Landmarks in the application of C-magnetic resonance spectroscopy to studies of neuronal/glial relationships. Dev. Neurosci 1998, 20 (4–5), 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kapetanovic IM; Yonekawa WD; Kupferberg HJ Use of stable isotopes and gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry in the study of different pools of neurotransmitter amino-acids in brain-slices. J. Chromatogr 1990, 500, 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).McNair LM; Andersen JV; Waagepetersen HS Stable isotope tracing reveals disturbed cellular energy and glutamate metabolism in hippocampal slices of aged male mice. Neurochem. Int 2023, 171, No. 105626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Shen J; Rothman DL Magnetic resonance spectroscopic approaches to studying neuronal: Glial interactions. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 52 (7), 694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Wood PL; Kim HS; Cheney DL; Cosi C; Marien M; Rao TS; Martin LL Constant infusion of c-13(6) glucose - simultaneous measurement of turnover of gaba and glutamate in defined regions of the brain of individual animals. Neuropharmacology 1988, 27 (7), 669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Yudkoff M; Daikhin Y; Lin ZP; Nissim I; Stern J; Pleasure D; Nissim I Interrelationships of leucine and glutamate metabolism in cultured astrocytes. Journal of Neurochemistry 1994, 62 (3), 1192–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Yudkoff M; Nissim I; Nelson D; Lin ZP; Erecinska M Glutamate-dehydrogenase reaction as a source of glutamic-acid in synaptosomes. Journal of Neurochemistry 1991, 57 (1), 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Zwingmann C; Butterworth R An update on the role of brain glutamine synthesis and its relation to cell-specific energy metabolism in the hyperammonemic brain: Further studies using NMR spectroscopy. Neurochem. Int 2005, 47 (1–2), 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Olsen GM; Sonnewald U Glutamate: Where does it come from and where does it go? Neurochem. Int 2015, 88, 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Kondrat RW; Kanamori K; Ross BD In vivo microdialysis and gas-chromatography/mass-spectrometry for < SUP > 13</SUP > C-enrichment measurement of extracellular glutamate in rat brain. J. Neurosci. Methods 2002, 120 (2), 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Church WH; Justice JB Rapid sampling and determination of extracellular dopamine invivo. Anal. Chem 1987, 59 (5), 712–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Song P; Mabrouk OS; Hershey ND; Kennedy RT In Vivo Neurochemical Monitoring Using Benzoyl Chloride Derivatization and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2012, 84 (1), 412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Maras PM; Blandino P; Hebda-Bauer EK; Watson SJ; Akil H Differences in microglia morphological profiles reflect divergent emotional temperaments: insights from a selective breeding model. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12 (1), 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Shin HJ Partial functional linear regression. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference 2009, 139 (10), 3405–3418. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Beagles KE; Morrison PF; Heyes MP Quinolinic acid in vivo synthesis rates, extracellular concentrations, and intercompartmental distributions in normal and immune-activated brain as determined by multiple-isotope microdialysis. Journal of Neurochemistry 1998, 70 (1), 281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Bengtsson J; Bostrom E; Hammarlund-Udenaes M The use of a deuterated calibrator for in vivo recovery estimations in microdialysis studies. J. Pharm. Sci 2008, 97 (8), 3433–3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Hershey ND; Kennedy RT In Vivo Calibration of Microdialysis Using Infusion of Stable-Isotope Labeled Neuro-transmitters. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2013, 4 (5), 729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Sun L; Stenken JA; Brunner JE; Michel KB; Adelsberger JK; Yang AY; Zhao JJ; Musson DG An in vivo microdialysis coupled with liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry study of cortisol metabolism in monkey adipose tissue. Anal. Biochem 2008, 381 (2), 214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Olson RJ; Justice JB Quantitative microdialysis under transient conditions. Anal. Chem 1993, 65 (8), 1017–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Parsons LH; Justice JB Extracellular concentration and invivo recovery of dopamine in the nucleus-accumbens using microdialysis. Journal of Neurochemistry 1992, 58 (1), 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Melone M; Quagliano F; Barbaresi P; Varoqui H; Erickson JD; Conti F Localization of the glutamine transporter SNAT1 in rat cerebral cortex and neighboring structures, with a note on its localization in human cortex. Cerebral Cortex 2004, 14 (5), 562–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Rae C; Hare N; Bubb WA; McEwan SR; Bröer A; McQuillan JA; Balcar VJ; Conigrave AD; Bröer S Inhibition of glutamine transport depletes glutamate and GABA neurotransmitter pools: further evidence for metabolic compartmentation. J. Neurochem 2003, 85 (2), 503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Erickson JD Functional identification of activity-regulated, high-affinity glutamine transport in hippocampal neurons inhibited by riluzole. Journal of Neurochemistry 2017, 142 (1), 29–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Conn PJ; Battaglia G; Marino MJ; Nicoletti F Metabotropic glutamate receptors in the basal ganglia motor circuit. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2005, 6 (10), 787–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Conn PJ; Pin JP Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 1997, 37, 205–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Smolders I; Lindekens H; Clinckers R; Meurs A; O’Neill MJ; Lodge D; Ebinger G; Michotte Y In vivo modulation of extracellular hippocampal glutamate and GABA levels and limbic seizures by group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands. Journal of Neurochemistry 2004, 88 (5), 1068–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Xi ZX; Baker DA; Shen H; Carson DS; Kalivas PW Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate extracellular glutamate in the nucleus Accumbens. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2002, 300 (1), 162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Battaglia G; Monn JA; Schoepp DD In vivo inhibition of veratridine-evoked release of striatal excitatory amino acids by the group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist LY354740 in rats. Neurosci. Lett 1997, 229 (3), 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Lorrain DS; Baccei CS; Bristow LJ; Anderson JJ; Varney MA Effects of ketamine and N-methyl-D-aspartate on glutamate and dopamine release in the rat prefrontal cortex: Modulation by a group II selective metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist LY379268. Neuroscience 2003, 117 (3), 697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Chefer V; Meis J; Wang G; Kuzmin A; Bakalkin G; Shippenberg T Repeated exposure to moderate doses of ethanol augments hippocampal glutamate neurotransmission by increasing release. Addiction Biology 2011, 16 (2), 229–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Montiel T; Camacho A; Estrada-Sanchez AM; Massieu L Differential effects of the substrate inhibitor L-trans-pyrrolidine-2,4-dicarboxylate (PDC) and the non-substrate inhibitor DL-threo-beta-benzyloxyaspartate (DL-TBOA) of glutamate transporters on neuronal damage and extracellular amino acid levels in rat brain in vivo. Neuroscience 2005, 133 (3), 667–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Aoki C; Kaneko T; Starr A; Pickel VM Identification of mitochondrial and nonmitochondrial glutaminase within select neurons and glia of rat forebrain by Elecron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Journal of Neuroscience Research 1991, 28 (4), 531–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Ding L; Xu XN; Li CC; Wang Y; Xia XH; Zheng JLC Glutaminase in microglia: A novel regulator of neuroinflammation. Brain Behavior and Immunity 2021, 92, 139–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Wurdig S; Kugler P Histochemistry of glutamate metabolizing enzymes in the rat cerebellar cortex. Neurosci. Lett 1991, 130 (2), 165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Takeuchi H; Jin SJ; Wang JY; Zhang GQ; Kawanokuchi J; Kuno R; Sonobe Y; Mizuno T; Suzumura A Tumor necrosis factor-α induces neurotoxicity via glutamate release from hemichannels of activated microglia in an autocrine manner. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281 (30), 21362–21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Thomas AG; O’Driscoll CM; Bressler J; Kaufmann WE; Rojas CJ; Slusher BS Small molecule glutaminase inhibitors block glutamate release from stimulated microglia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2014, 443 (1), 32–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Kozai TDY; Jaquins-Gerstl AS; Vazquez AL; Michael AC; Cui XT Dexamethasone retrodialysis attenuates microglial response to implanted probes in vivo. Biomaterials 2016, 87, 157–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Tikka T; Fiebich BL; Goldsteins G; Keinänen R; Koistinaho J Minocycline, a tetracycline derivative, is neuro-protective against excitotoxicity by inhibiting activation and proliferation of microglia. J. Neurosci 2001, 21 (8), 2580–2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Yrjänheikki J; Keinänen R; Pellikka M; Hökfelt T; Koistinaho J Tetracyclines inhibit microglial activation and are neuroprotective in global brain ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1998, 95 (26), 15769–15774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Kobayashi K; Imagama S; Ohgomori T; Hirano K; Uchimura K; Sakamoto K; Hirakawa A; Takeuchi H; Suzumura A; Ishiguro N; et al. Minocycline selectively inhibits M1 polarization of microglia. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, No. e525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Dolgodilina E; Imobersteg S; Laczko E; Welt T; Verrey F; Makrides V Brain interstitial fluid glutamine homeostasis is controlled by blood-brain barrier SLC7A5/LAT1 amino acid transporter. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2016, 36 (11), 1929–1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Kyllo T; Singh V; Shim H; Latika S; Chen YJ; Terry E; Wulff H; Erickson JD; Nguyen HM Riluzole and novel naphthalenyl substituted aminothiazole derivatives prevent acute neural excitotoxic injury in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropharmacology 2023, 224, No. 109349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Lingamaneni R; Hemmings HC Effects of anticonvulsants on veratridine- and KCl-evoked glutamate release from rat cortical synaptosomes. Neurosci. Lett 1999, 276 (2), 127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Martin D; Thompson MA; Nadler JV The neuro-protective agent riluzole inhibits release of glutamate and aspartate from slices of hippocampal area ca1. Eur. J. Pharmacol 1993, 250 (3), 473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Wang SJ; Wang KY; Wang WC Mechanisms underlying the riluzole inhibition of glutamate release from rat cerebral cortex nerve terminals (synaptosomes). Neuroscience 2004, 125 (1), 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Bagley J; Moghaddam B Temporal dynamics of glutamate efflux in the prefrontal cortex and in the hippocampus following repeated stress: Effects of pretreatment with saline or diazepam. Neuroscience 1997, 77 (1), 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Rimmele TS; Rocher AB; Wellbourne-Wood J; Chatton JY Control of Glutamate Transport by Extracellular Potassium: Basis for a Negative Feedback on Synaptic Transmission. Cerebral Cortex 2017, 27 (6), 3272–3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Yang J; Shen J Elevated endogenous GABA concentration attenuates glutamate-glutamine cycling between neurons and astroglia. Journal of Neural Transmission 2009, 116 (3), 291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Kreitzer AC; Regehr WG Cerebellar depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition is mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. J. Neurosci 2001, 21 (20), RC174–RC174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Maejima T; Ohno-Shosaku T; Kano M Endogenous cannabinoid as a retrograde messenger from depolarized postsynaptic neurons to presynaptic terminals. Neuroscience Research 2001, 40 (3), 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Guo BL; Wang JQ; Yao H; Ren KK; Chen J; Yang J; Cai GH; Liu HY; Fan YL; Wang WT; et al. Chronic Inflammatory Pain Impairs mGluR5-Mediated Depolarization-Induced Suppression of Excitation in the Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Cerebral Cortex 2018, 28 (6), 2118–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Moussawi K; Riegel A; Nair S; Kalivas PW Extracellular glutamate: functional compartments operate in different concentration ranges. Front. Syst. Neurosci 2011, 5, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.