Graphical abstract

Key words: APG777, pharmacokinetics, IL-13, anti–IL-13 mAb, biologic therapy, human mAbs, atopic dermatitis, type 2 diseases, lebrikizumab, YTE, half-life extension, interleukin-13, type-2 inflammation

Abstract

Background

IL-13 plays a key role in the induction and perpetuation of type 2 immune responses associated with the development of atopic dermatitis and other chronic inflammatory diseases. mAbs targeting IL-13 have demonstrated efficacy in IL-13–driven diseases; however, current therapeutics require dosing every 2 to 4 weeks, resulting in significant injection burden for patients. APG777 is a humanized, IgG1 IL-13–targeting mAb that has been engineered to have an optimized pharmacokinetic profile, allowing for less frequent dosing.

Objective

We sought to investigate the in vitro potency and in vivo pharmacokinetics of APG777.

Methods

The affinity of APG777 was characterized using surface plasmon resonance; the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of APG777 was determined in various in vitro assays measuring inhibition of IL-13 signaling via signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 phosphorylation and chemokine release in relevant cell lines. Pharmacokinetics of APG777 were evaluated in nonhuman primates following a single intravenous or subcutaneous infusion. All studies included lebrikizumab produced based on the publicly available sequence as key comparator.

Results

APG777 demonstrated a similar in vitro potency across numerous assays compared with lebrikizumab and a 2-fold longer serum half-life following subcutaneous injection in nonhuman primates.

Conclusions

These data provide evidence in support of the clinical potential of APG777 in diseases where IL-13 signaling is a main driver of the inflammatory response. The prolonged half-life of APG777 may enable less frequent dosing compared with current treatments, which could reduce injection burden and increase compliance. APG777 is currently being investigated in a phase 2 randomized, controlled trial in patients with atopic dermatitis.

Type 2 inflammation is an important driver of atopic dermatitis (AD) and asthma.1, 2, 3 This immune response is characterized by the activation of TH2 cells and the subsequent release and overexpression of type 2 inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-13 and IL-4, which contribute to chronic inflammation and tissue damage.4, 5, 6

IL-13 induces and perpetuates the type 2 immune response cascade through the release of other proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, the recruitment of inflammatory cells, and isotype switching in B cells to induce production of IgE.7,8 IL-13 exerts its effects by binding to the IL-13α1 receptor (IL-13Rα1), which subsequently dimerizes with the IL-4α receptor (IL-4Rα) to form an active IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα heterodimer.9 Formation of the active IL-13Rα1/IL-13/IL-4Rα signaling complex results in activation of Janus kinase 1 and Janus kinase 2, and phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6), which translocates to the nucleus, where it induces transcription of IL-13–responsive genes, including thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC)/C-C chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17).7,10, 11, 12, 13 TARC is a disease-relevant biomarker in AD, correlating with disease severity.14,15 Reduction of TARC is consistently observed following administration of IL-13 and IL-4Rα–targeted agents.16

Pharmacologic approaches targeting the IL-13/IL-4 pathway include a number of biologics investigated over recent years for the treatment of inflammatory conditions. These therapies include the IL-13–specific mAbs lebrikizumab, cendakimab, and tralokinumab, as well as the IL-4Rα–specific mAb dupilumab, which blocks both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling. Lebrikizumab and tralokinumab have been approved by regulatory agencies for use in patients with moderate to severe AD.17, 18, 19, 20 Beyond AD, IL-13 also plays a critical role in asthma and eosinophilic esophagitis. A phase 2 study with the IL-13–selective antibody cendakimab (RPC4046) showed promising results in eosinophilic esophagitis,21 and dupilumab is now approved for this indication.18,19 In asthma, early studies of IL-13 inhibitors fell short in broad populations; however, emerging evidence suggests that efficacy may be observed in a subset of patients with elevated blood eosinophil count and a history of exacerbations, similar to the population where dupilumab has demonstrated benefit.22

There are 2 main mechanisms of action leveraged by mAbs targeting IL-13. Although lebrikizumab, tralokinumab, and cendakimab all bind directly to IL-13, tralokinumab and cendakimab bind to a different epitope on human IL-13 than does lebrikizumab. Tralokinumab and cendakimab inhibit the binding of IL-13 to the IL-13Rα1 and IL-13Rα2 chains.23 The IL-13Rα2 subunit has a higher affinity for IL-13 and is thought to mediate the natural clearance of excess IL-13 from circulation. Consequently, results from studies in AD suggest that tralokinumab and cendakimab may not provide the same level of clinical efficacy as lebrikizumab.24 Lebrikizumab has demonstrated efficacy in AD that is comparable to that of dupilumab24; however, it requires dosing every 2 to 4 weeks, which represents a significant injection and treatment burden for patients with chronic diseases.17,20 Because more frequent dosing is associated with poorer adherence to drug therapy,25 there is a need for longer-acting biologics with reduced dosing frequency for the treatment of type 2–mediated inflammatory conditions.

To address this need, we developed and characterized APG777, a high-affinity, humanized IgG1 mAb targeting IL-13. APG777 has been engineered with modifications that extend its half-life and attenuate effector function, giving it an optimized pharmacokinetic (PK) profile. APG777 is designed to bind to IL-13 in a similar manner as that of lebrikizumab, which does not interfere with IL-13 binding to IL-13Rα but allosterically blocks IL-13Rα/IL-13 from complexing with IL-13Rα, thereby suppressing IL-13–induced signaling. By binding to IL-13, APG777 prevents IL-4Rα from binding to the IL-13Rα1/IL-13 precomplex, thereby blocking formation of the active IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα heterodimer and blocking downstream inflammatory signaling, which is similar to the mechanism of action of lebrikizumab. APG777 contains the triple amino acid modification M253Y/S255T/T257E (referred to as a “YTE” modification) in its Fc region, designed to increase the binding affinity to the human neonatal Fc receptor (huFcRn) under acidic pH conditions, thereby increasing its serum half-life by promoting recycling via the endosomal-lysosomal salvage pathway and returning IgG to circulation.26,27 Consequently, this may allow for less frequent dosing, thus enabling reduced injection burden for patients and potentially better treatment adherence. The Fc region of APG777 also contains 2 additional amino acid modifications—L235A/L236A (referred to as a “LALA” modification)—designed to attenuate Fc and complement effector functions.28

Here, we report preclinical data characterizing APG777. We evaluated the binding affinity of APG777 to IL-13 and the ability of APG777 to block receptor complex formation and downstream signaling in vitro and compared the PK of APG777 to that of a lebrikizumab analog in nonhuman primates (NHPs) following intravenous and subcutaneous (SC) administration. In our studies, lebrikizumab, produced based on the publicly available sequence, is the key benchmark for comparison.

Methods

mAbs/reagents

APG777 was expressed and purified from a recombinant CHO cell line (WuXi Biologics, Shanghai, China). A lebrikizumab analog (hereafter referred to as lebrikizumab) was expressed and purified from a recombinant CHO cell line based on the published sequence for lebrikizumab. Similarly, tralokinumab and cendakimab were expressed based on their published sequences and purified as research-grade material (WuXi Biologics, Shanghai, China). All other materials were obtained from commercially available sources as indicated.

Binding affinity for human IL-13

The affinities of test articles APG777 and lebrikizumab for recombinant human IL-13 (ACROBiosystems, Newark, Del) were measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Test articles were immobilized to a Series S Protein G sensor chip (Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, Mass), and the binding of IL-13 was evaluated using multicycle kinetics by associating the soluble IL-13 with the immobilized mAbs. SPR values were provided in nM.

Competitive SPR binding study

To characterize the epitope of anti–IL-13 mAbs lebrikizumab, APG777, tralokinumab, and cendakimab, competitive binding to a given antibody against every other antibody (including itself) was assessed. Generally, the first antibody was immobilized onto a Series S Sensor Chip surface through amine coupling, capable of measuring mAb-antigen interactions. IL-13 was first injected into the flow channel, where binding of IL-13 to the first antibody generated a response. The second antibody was subsequently injected into the flow channel, and the interaction response was recorded. All 4 antibodies— lebrikizumab, APG777, tralokinumab, and cendakimab—were thus tested in an immobilized context.

Binding affinity to human Fc receptors and C1q

The binding affinity of APG777 to human Fc receptors and C1q was determined by SPR and ELISA, respectively, and compared with that of a control IgG1, rituximab (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

To establish whether YTE modification increased binding affinity to huFcRn by SPR, APG777 and a non-YTE comparator, rituximab, were immobilized to a Series S CM5 sensor chip. The running buffer was PBS with Tween 20 at pH 5.8 or pH 7.4. Binding at acidic and neutral pH was tested because huFcRn exhibits pH-dependent binding to IgG where the acidic pH mimics the environment of the endosomal compartment. The YTE modification enables a higher affinity for huFcRn at acidic pH than the unmodified IgG. huFcRn binding was evaluated using an 8-point concentration series starting with a concentration of 1.5 μM for APG777 and 6.0 μM for the rituximab control with a 2-fold dilution between each point. Where distinct association/dissociation behavior was noted, a steady-state model was used to fit the data to determine an affinity value.

To determine the effect of the LALA modification on binding to Fcγ receptors (FcγRs), APG777 and, non-LALA modified comparator, rituximab were evaluated by SPR using a Series S CM5 sensor chip (Cytiva) functionalized with an anti-His tag antibody (Genscript, Piscataway NJ), which enabled immobilization of the His-tagged Fcγ receptors (Acrobiosystems). Binding affinity for several FcγRs that are known to mediate Fc-mediated effector function and their common variants were assessed by SPR. Samples were evaluated using a 7- to 9-point concentration series with a 2-fold dilution between each point (see this article’s additional Methods section in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Where distinct association/dissociation behavior was noted, a 1:1 Langmuir or steady-state model was used to fit the data to determine an affinity value.

Binding to C1q (Complement Technology, Tyler, Tex) was determined by ELISA with APG777 and a non–LALA-modified comparator, rituximab. Plates were coated with the test antibody and C1q was added as a half-log serial dilution to the wells. The plates were then washed and subsequently incubated with a secondary antibody—sheep antihuman C1q with horseradish peroxidase label. Tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution was added, and the enzymatic reaction was stopped. The absorbance at 450 nm (proportional to C1q binding) was measured. The data were fitted to a 4-parameter logistic model.

Cell-based IL-13 binding assay

To investigate the effect of APG777 on formation of the IL-13Rα1/IL-13/IL-4Rα complex, HEK293 cells (ChemPartner, Shanghai, China) coexpressing IL-13Rα1 and IL-4Rα were incubated with recombinant human IL-13 (biotin-hIL13-His-Avi; ACROBiosystems) at a final concentration of 0.05 μg/mL. APG777 or lebrikizumab was added to achieve final mAb concentrations of 100 nM, 20 nM, 4 nM, 2 nM, 1 nM, 0.8 nM, and 0.16 nM. Cells were allowed to incubate for 1 hour at 37°C. The binding of IL-13 to the cell surface was subsequently analyzed using flow cytometry with a fluorophore-labeled streptavidin (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, Calif). One theoretical limitation of this assay is interference between APG777 and the fluorescently labeled streptavidin tag used to detect IL-13. Although assay interference is a possibility, it is unlikely because detection of IL-13 relies on a C-terminal tag that extends beyond the canonical IL-13 sequence. All samples were evaluated in independent technical triplicates.

Raw data were automatically collected as each well was run by the BD FACSCanto II (BD Bioscience, San Jose, Calif), and subsequently analyzed using FlowJo v10 (FlowJo, Ashland, Ore) using the established gating strategy for each well. A subpopulation of the total events was “gated,” according to setup based on side-scatter versus forward-scatter. The mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of the channel was evaluated and values were exported. The MFI signals were then related back to the respective mAb concentrations. MFI versus antibody concentration was plotted in a sigmoidal response curve.

Inhibition of STAT6 phosphorylation

IL-13–induced phosphorylation of STAT6 was investigated in the HT-29 colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va) and in primary CD14+ and CD19+ cells from human PBMCs (BioIVT, Westbury, Vt). HT-29 cells or PBMCs were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of recombinant human IL-13 (PeproTech, ThermoFisher, Cranbury, NJ). APG777 or lebrikizumab was incubated for 1 hour at 37°C at different final concentrations of 100 nM, 20 nM, 4 nM, 2 nM, 1 nM, 0.5 nM, 0.1 nM, and 0.02 nM for HT-29 cells, and 10 nM, 5 nM, 2.5 nM, 1.25 nM, 0.63 nM, 0.31 nM, 0.16 nM, 0.08 nM, and 0.04 nM for PBMCs. Phosphorylation of STAT6 was subsequently assessed by flow cytometry detecting anti-pSTAT6 antibody (PE Mouse Anti-Stat6 [pY641], BD Bioscience) on fixed and permeabilized cells (see this article’s additional Methods section in the Online Repository).

IL-13–induced cell proliferation

TF-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection; CRL-2003), a human erythroblast cell line highly sensitive to IL-13, were stimulated with 4 ng/mL of recombinant IL-13. APG777 or lebrikizumab was added at different final concentrations of 5.000 nM, 1.667 nM, 0.556 nM, 0.278 nM, 0.185 nM, 0.139 nM, 0.046 nM, or 0.015 nM. Cells were incubated for 72 hours at 37°C. The resulting cell density was determined using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis), a luminescent substrate quantifying adenosine triphosphate levels, which are proportional to the number of metabolically active cells in culture.

TARC secretion from lung cell line

The effect of APG777 on TARC secretion was investigated in the lung epithelial cell line, A549 (American Type Culture Collection; CRM-CCL-185). A549 cells were treated with a combination of recombinant IL-13 (hIL-13-His-CP, ChemPartner) and recombinant TNF-α (PeproTech) at a final concentration of 20 ng/mL and 200 ng/mL, respectively. APG777 or lebrikizumab was added at different final concentrations of 100 nM, 20 nM, 4 nM, 1.6 nM, 0.8 nM, 0.32 nM, 0.16 nM, or 0.032 nM. These cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. The concentration of TARC in the culture supernatant was subsequently quantified using the human TARC/CCL17 DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn).

IL-13–induced upregulation of CD23 on monocytes and B cells

To evaluate the inhibition of CD23 expression, human PBMCs (BioIVT) were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of recombinant IL-13 (PeproTech). APG777 or lebrikizumab was added at different final concentrations from a 6-point concentration series starting with a concentration of 6.67 nM with a 2-fold dilution between each point. Cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. CD23 expression was subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry using an anti-CD23 antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, Calif). Raw data were collected as described above. Cells were gated within the specific immune population by lineage-specific markers CD3−, CD14+, and CD19+ (BioLegend). Within this CD19+ and CD14+ population, the MFI signals were then related back to the respective mAb concentrations. MFI versus antibody concentration was plotted and a sigmoidal response curve was fitted. All samples were evaluated in independent technical triplicates.

Pharmacokinetics of APG777 in NHPs

The PK of APG777 and lebrikizumab was studied in female cynomolgus monkeys at Charles River Laboratories (Mattawan, Mich). The study complied with all the applicable sections of the Final Rules of the Animal Welfare Act regulations (Code of Federal Regulations, Title 9) of the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the US Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the US National Research Council of the National Academies.

PK values were determined following a single intravenous or SC infusion of 3 mg/kg (n = 3 animals per dose route). Blood samples were collected serially starting with a sample predose and subsequently up to 2160 hours postdose. Anti-human kappa antibody was used for detection (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, Ala). Serum PK parameters that were calculated included maximum observed serum concentration, time to maximum observed serum concentration, area under the serum concentration versus time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity, clearance, volume of distribution at steady state, half-life, and absolute SC bioavailability.

Results

APG777 demonstrates strong binding affinity to IL-13, blocking the formation of the active IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα heterodimer

APG777 binds to both human and NHP IL-13 with pM affinity (dissociation constant [KD] of 77 pM for human IL-13 and KD of 208 pM for NHP IL-13), demonstrating cross-reactivity in these 2 species; APG777 did not bind to mouse or rat IL-13 (data not shown). By comparison, lebrikizumab has a KD of 131 pM and 309 pM for human IL-13 and NHP IL-13, respectively (Table I).

Table I.

Binding affinity of anti–IL-13 mAbs for human and NHP IL-13 as measured by SPR

| mAb | Human IL-13 KD (pM) |

NHPIL-13 KD (pM) |

|---|---|---|

| APG777 | 77 | 208 |

| Lebrikizumab | 131 | 309 |

Next, we evaluated the ability of APG777 to functionally disrupt IL-13 receptor complex formation, using a cell-based binding assay with HEK293 cells engineered to coexpress human IL-13Rα1 and IL-4Rα. In this system, IL-13 is stabilized on the cell surface only upon formation of the heterotrimeric receptor complex (IL-13Rα1/IL-13/IL-4Rα),29,30 because IL-13 initially interacts with IL-13Rα1 with low affinity31 and requires subsequent binding to IL-4Rα to stabilize the complex on the cell surface. Both APG777 and lebrikizumab were evaluated for their ability to disrupt this receptor complex formation and thereby reduce stable IL-13 binding to the cell surface. APG777 reduced IL-13 on the cell surface of HEK293 cells with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.89 nM, comparable to the IC50 of 1.11 nM observed for lebrikizumab (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

APG777 reduced IL-13 bound to its cell surface receptor. IL-13 bound to HEK293 cells engineered to coexpress human IL-13Rα1 and IL-4Rα was assessed by flow cytometry. MFI vs antibody concentration was plotted in a sigmoidal response curve fit by nonlinear regression. All samples were evaluated in technical triplicates.

The binding domain of APG777 to IL-13 was evaluated in a competitive SPR binding study using several benchmark mAbs including lebrikzumab, tralokinumab, and cendakimab. APG777 and lebrikizumab competitively bound IL-13 and were noncompetitive with tralokinumab and cendakimab (Table II). The competitive binding profile of APG777 was observed when it was immobilized and soluble. This provides evidence to support that lebrikizumab and APG777 bind to an overlapping epitope on IL-13. The noncompetitive binding of tralokinumab and cendakimab with lebrikizumab confirms that they bind a different epitope on IL-13, but that APG777 binds a similar epitope on IL-13 as that of lebrikizumab.

Table II.

Antibody epitope determination by competitive binding

| Soluble mAb | Competitive binding to immobilized antibody bound to soluble IL-13 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lebrikizumab | APG777 | Tralokinumab | Cendakimab | |

| Lebrikizumab | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| APG777 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Tralokinumab | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cendakimab | No | No | Yes | Yes |

APG777 inhibits downstream signaling events of IL-13

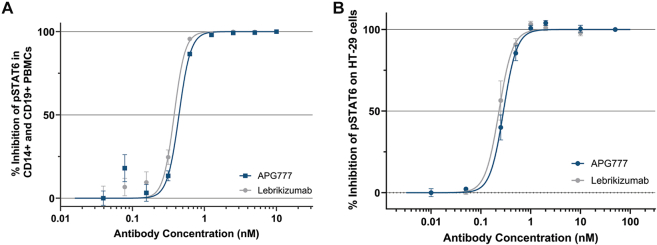

To evaluate the functional consequence of APG777 binding to IL-13, we assessed the ability of APG777 to inhibit IL-13–induced STAT6 phosphorylation in 2 independent cellular systems: primary human CD14+ and CD19+ cells isolated from PBMCs and the HT-29 colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line. In both models, APG777 inhibited IL-13–mediated STAT6 phosphorylation in a concentration-dependent manner. APG777 exhibited an IC50 of 0.44 nM, comparable to the IC50 of 0.38 nM observed for lebrikizumab in primary CD14+ and CD19+ cells (Fig 2, A), similar to HT-29 (Fig 2, B).

Fig 2.

APG777 inhibits phosphorylation of STAT6. A, Primary CD14+ and CD19+ cells from healthy donor PBMCs. B, HT-29. pSTAT was assessed by intercellular staining by flow cytometry. MFI vs antibody concentration was plotted in a sigmoidal response curve fit by nonlinear regression.

To further evaluate APG777 on downstream activity of IL-13, we assessed IL-13–induced cell proliferation of TF-1 cells, a human erythroleukemic cell line used to model cytokine-driven proliferation. APG777 potently inhibited IL-13–induced TF-1 proliferation in a dose-dependent manner, with an IC50 of 0.16 nM, similar to lebrikizumab (IC50 = 0.20 nM) (Fig 3, A).

Fig 3.

APG777 inhibits multiple downstream events of IL-13 and markers of type 2 inflammation. A, IL-13–mediated cell proliferation of TF-1 evaluated with viability assay. B, TARC release from lung cell line A549 measured by ELISA. C, Surface expression of CD23 on CD14+ and CD19+ immune cells from healthy donor PBMCs measured by flow cytometry.

We next examined the effect of APG777 on production of the chemokine TARC/CCL17. In A549 cells, a human alveolar epithelial cell line that endogenously expresses IL-13 receptors, costimulation with IL-13 and TNF-α, induced robust secretion of TARC, which was inhibited by APG777 in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 = 0.86 nM), comparable to lebrikizumab (IC50 = 0.74 nM) (Fig 3, B).

Finally, we investigated the impact of APG777 on IL-13–induced CD23 (FcεRII) expression. CD23 is a low-affinity receptor for IgE expressed on B cells and monocytes, where it contributes to IgE regulation and IgE-facilitated antigen presentation. Primary human PBMCs were stimulated with recombinant IL-13, and surface CD23 levels were measured by flow cytometry on CD19+ B cells and CD14+ monocytes. APG777 inhibited IL-13–induced CD23 expression in a dose-dependent manner, with an IC50 of 0.86 nM, similar to lebrikizumab (IC50 = 0.81 nM; Fig 3, C). These findings further demonstrate the ability of APG777 to suppress IL-13–mediated immune activation across multiple functional readouts.

APG777 optimized for extended half-life

Although APG777 demonstrates comparable functional activity to lebrikizumab in blocking IL-13 signaling, it incorporates 2 Fc-region modifications that confer distinct advantages in PK and effector function profiles.

APG777 contains the M253Y/S255T/T257E (“YTE”) triple modification, which enhances binding to huFcRn at acidic pH, facilitating endosomal recycling and protecting the antibody from lysosomal degradation. This modification is designed to prolong serum half-life. SPR studies demonstrated that APG777 binds to huFcRn with higher affinity than does an IgG1-positive control at pH 5.8. No measurable binding is observed at pH 7.4, consistent with the expected pH-dependent interaction profile of YTE-engineered antibodies (Table III).

Table III.

Binding affinity of APG777 for huFcRn, FcγR receptors, and C1q compared with IgG1 control mAb

| Ligand | APG777 KD (M) | IgG1 positive control KD (M) |

|---|---|---|

| huFcRn (pH 5.8) | 9.44 × 10−8 | 1.28 × 10−6 |

| huFcRn (pH 7.4) | No measurable binding | No measurable binding |

| FcγRI | 7.88 × 10−6 | 7.55 × 10−10 |

| FcγRIIa (H131) | No measurable binding | 2.93 × 10−6 |

| FcγRIIa (R131) | No measurable binding | 5.95 × 10−6 |

| FcγRIIb | No measurable binding | 1.53 × 10−5 |

| FcγRIIIa (F158) | 5.62 × 10−5 | 9.57 × 10−7 |

| FcγRIIIa (V158) | 1.21 × 10−5 | 1.93 × 10−7 |

| C1q | No measurable binding | 1.6 × 10−8 |

IgG1, Immunoglobulin gamma 1.

To assess whether the YTE modification translates into improved PK in vivo, we conducted a head-to-head comparison of APG777 and lebrikizumab in NHPs. APG777 exhibited a 2-fold longer half-life of 27.0 days when administered SC; in comparison, lebrikizumab had a half-life of 13.5 days (Table IV; Fig 4). APG777 had a clearance rate of 1.48 (mL/d/kg) after SC administration; the clearance rate for lebrikizumab was 2.93 (mL/d/kg; Table IV; Fig 4). Both APG777 and lebrikizumab were well absorbed, with SC bioavailability determined to be 81.2% and 75.7%, respectively (Table IV).

Table IV.

Serum pharmacokinetic parameters of APG777 and lebrikizumab following a single-bolus IV or SC dose in cynomolgus monkeys

| Mean (SE) | APG777 |

Lebrikizumab∗ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | SC | IV | SC | |

| Tmax (d) | 0 | 3.33 (0.67) | 0 | 2.33 (0.89) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 1.03 × 105 (4.50 × 103) | 4.13 × 104 (1.65 × 103) | 9.68 × 104 (4.65 × 103) | 4.25 × 104 (1.16 × 103) |

| AUC0-inf (ng h/mL) | 5.05 × 107 (1.99 × 106) | 4.10 × 107 (5.39 × 106) | 2.66 × 107 (4.76 × 106) | 2.01 × 107 (4.18 × 106) |

| CL (mL/d/kg)† | 1.43 (0.05) | 1.48 (0.20) | 2.93 (0.61) | 2.93 (0.53) |

| Vss (mL/kg)† | 54.06 (1.18) | 57.24 (1.92) | 59.26 (5.79) | 44.95 (4.01) |

| F (%)‡ | NA | 81.22 (13.70) | NA | 75.70 (27.40) |

| Half-life (d) | 28.2 (1.16) | 27.0 (2.45) | 18.1 (3.87) | 13.5 (2.66) |

Serum PK parameters were assessed in female cynomolgus monkeys (n = 3).

AUC0-inf, Area under the serum concentration vs time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity; CL, clearance; Cmax, maximum observed serum concentration; F, bioavailability; IV, intravenous; NA, not applicable; Tmax, time to maximum observed serum concentration; Vss, volume of distribution at steady state.

mAb expressed based on the published sequence of lebrikizumab.

Both CL and Vss of SC administration were dose normalized using the SC bioavailability (F) indicated in the table.

F (%) was calculated by dividing the mean dose-normalized AUC0-inf following SC administration by the mean dose-normalized AUC0-inf following IV administration.

Fig 4.

APG777 exhibits a prolonged half-life compared with lebrikizumab in NHP. A, IV administration. B, SC administration. Data show serum concentration-time curves for APG777 and lebrikizumab in cynomolgus monkeys (n = 3 group, female). IV, Intravenous.

APG777 also includes a L235A/L236A (“LALA”) modification in the Fc domain, which is designed to attenuate binding to Fcγ receptors and complement component C1q, thereby reducing immune effector functions such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and complement-dependent cytotoxicity. SPR analysis confirmed that APG777 exhibited markedly reduced or undetectable binding to a panel of human Fc receptors—including FcγRI, FcγRIIa (H131), FcγRIIa (R131), FcγRIIb, FcγRIIIa (F158), and FcγRIIIa (V158)—as well as to C1q by ELISA, relative to an IgG1 control (Table III).

Discussion

Here, we characterize APG777, a novel humanized IgG1 mAb that binds to IL-13 with picomolar affinity, inhibits downstream IL-13 signaling, and has an optimized PK profile. APG777 demonstrated similar affinity for IL-13 and similar potency to lebrikizumab in multiple functional assays. The potent inhibition of TARC by APG777 is notable, because TARC is a clinically relevant biomarker in AD.14,15 Our results show that the binding epitope of APG777 to IL-13 overlaps with that of lebrikizumab, and supports a similar binding and efficacy profile for APG777 as that previously reported for lebrikizumab.32

APG777 exhibited enhanced pH-dependent binding affinity to huFcRn and attenuated binding to Fc-gamma receptors and C1q, which are consistent with functions of the introduced YTE and LALA amino acid modifications, respectively. These modifications are clinically validated because, to date, there have been 2 approved mAbs with YTE modifications, as well as numerous completed and ongoing studies of mAbs with similar modification.33,34 mAbs leveraging LALA modifications have also been tested in clinical studies without reported safety concerns and there are 6 approved therapies with this particular type of LALA modification, with numerous others under investigation.33,34

APG777 exhibited an extended half-life in NHPs relative to lebrikizumab. Half-life extension was also observed in a PK study in humans.35 Furthermore, the increase in half-life and exposure, and reduced clearance that we observed for APG777 compared with lebrikizumab, suggests that APG777 may be well suited for less frequent dosing. Together, the data provide preclinical evidence of the clinical potential of APG777, in terms of both efficacy and potency for the treatment of diseases where IL-13 signaling is the main driver of the inflammatory response.

Two mAbs targeting IL-13—lebrikizumab and tralokinumab—have been approved by regulatory agencies for use in patients with moderate to severe AD.17,20,36,37 Both drugs are dosed SC every other week, with the treatment window extended to every 4 weeks in patients who show a therapeutic response.17,20,36,37 Clinical data from a phase 1 study in healthy human volunteers demonstrated that APG777 has a half-life in humans that is 2 to 3 times longer than those of lebrikizumab and tralokinumab.35 A 2-part, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of APG777 in patients with moderate to severe AD (NCT06395948) was initiated in May 2024 and is testing both higher exposures in an induction setting and less frequent dosing intervals in a maintenance setting than have been explored with other anti–IL-13 mAbs.17,20,36,37 The determined prolonged half-life of APG777 compared with that of lebrikizumab in NHPs supports the potential for a wider clinical dosing interval in humans, which may decrease the injection burden for patients and also improve patient adherence. Given the promising preclinical and early clinical profile of APG777, investigations in other chronic type 2 inflammatory diseases may also be considered in the future.

Clinical implications.

APG777 exhibits similar affinity and potency to lebrikizumab, an anti–IL-13 mAb approved for AD; however, it demonstrates a 2-fold longer serum half-life, potentially allowing for reduced injection burden in type 2 inflammatory diseases such as AD.

Disclosure statement

The research reported in this study was funded by Apogee Therapeutics, Inc.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: E. Zhu, J. Oh, and H. Shaheen are employees of Paragon Therapeutics, Inc, and may own Paragon stock/stock options. R. Dabora, N. A. Gandhi, G. Wickman, C. Dambkowski, and L. Dillinger are employees of Apogee Therapeutics, Inc, and may own Apogee stock/stock options. H. Prentice is a paid consultant of Apogee Therapeutics, Inc.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lee Miller and Lucy Kanan of Miller Medical Communications (on behalf of Apogee Therapeutics, Inc) and Josh Cirulli and Annalise M. Nawrocki (of Apogee Therapeutics, Inc) for medical writing and editorial support. We also thank Kristine Nograles and Jennifer Mohawk (of Apogee Therapeutics, Inc) for their critical review of the manuscript.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Davidson W.F., Leung D.Y.M., Beck L.A., Berin C.M., Boguniewicz M., Busse W.W., et al. Report from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases workshop on “Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march: Mechanisms and interventions”. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:894–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irvine A.D., Mina-Osorio P. Disease trajectories in childhood atopic dermatitis: an update and practitioner’s guide. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:895–906. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izuhara K., Arima K., Yasunaga S. IL-4 and IL-13: their pathological roles in allergic diseases and their potential in developing new therapies. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2002;1:263–269. doi: 10.2174/1568010023344661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck L.A., Cork M.J., Amagai M., De Benedetto A., Kabashima K., Hamilton J.D., et al. Type 2 inflammation contributes to skin barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. JID Innov. 2022;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2022.100131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maspero J., Adir Y., Al-Ahmad M., Celis-Preciado C.A., Colodenco F.D., Giavina-Bianchi P., et al. Type 2 inflammation in asthma and other airway diseases. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8:00576–2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00576-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roediger B., Weninger W. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells in the regulation of immune responses. Adv Immunol. 2015;125:111–154. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormick S.M., Heller N.M. Commentary: IL-4 and IL-13 receptors and signaling. Cytokine. 2015;75:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynn T.A. IL-13 effector functions. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito T., Suzuki S., Kanaji S., Shiraishi H., Ohta S., Arima K., et al. Distinct structural requirements for interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 binding to the shared IL-13 receptor facilitate cellular tuning of cytokine responsiveness. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24289–24296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liddiard K., Welch J.S., Lozach J., Heinz S., Glass C.K., Greaves D.R. Interleukin-4 induction of the CC chemokine TARC (CCL17) in murine macrophages is mediated by multiple STAT6 sites in the TARC gene promoter. BMC Mol Biol. 2006;7:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaPorte S.L., Juo Z.S., Vaclavikova J., Colf L.A., Qi X., Heller N.M., et al. Molecular and structural basis of cytokine receptor pleiotropy in the interleukin-4/13 system. Cell. 2008;132:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goenka S., Kaplan M.H. Transcriptional regulation by STAT6. Immunol Res. 2011;50:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s12026-011-8205-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S., Olde Heuvel F., Rehman R., Aousji O., Froehlich A., Li Z., et al. Interleukin-13 and its receptor are synaptic proteins involved in plasticity and neuroprotection. Nat Commun. 2023;14:200. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-35806-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umeda M., Origuchi T., Kawashiri S.Y., Koga T., Ichinose K., Furukawa K., et al. Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine as a biomarker for IgG4-related disease. Sci Rep. 2020;10:6010. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62941-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hijnen D., De Bruin-Weller M., Oosting B., Lebre C., De Jong E., Bruijnzeel-Koomen C., et al. Serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) and cutaneous T cell- attracting chemokine (CTACK) levels in allergic diseases: TARC and CTACK are disease-specific markers for atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratchataswan T., Banzon T.M., Thyssen J.P., Weidinger S., Guttman-Yassky E., Phipatanakul W. Biologics for treatment of atopic dermatitis: current status and future prospect. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1053–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Medicines Agency Ebglyss (lebrikizumab) Summary of Product Characteristics. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ebglyss-epar-product-information_en.pdf Available at:

- 18.European Medicines Agency Dupixent (dupilumab) Summary of Product Characteristics. 2024. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/dupixent-epar-product-information_en.pdf Available at:

- 19.Food and Drug Administration Dupixent (dupilumab) Prescribing Information. 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/761055s066lbl.pdf Available at:

- 20.Food and Drug Administration Ebglyss (lebrikizumab) Prescribing Information. 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/761306s000lbledt.pdf

- 21.Hirano I., Collins M.H., Assouline-Dayan Y., Evans L., Gupta S., Schoepfer A.M., et al. RPC4046, a monoclonal antibody against IL13, reduces histologic and endoscopic activity in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:592–603.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corren J., Szefler S.J., Sher E., Korenblat P., Soong W., Hanania N.A., et al. Lebrikizumab in uncontrolled asthma: reanalysis in a well-defined type 2 population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12:1215–1224.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2024.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okragly A.J., Ryuzoji A., Wulur I., Daniels M., Van Horn R.D., Patel C.N., et al. Binding, neutralization and internalization of the interleukin-13 antibody, lebrikizumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023;13:1535–1547. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00947-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverberg J.I., Bieber T., Paller A.S., Beck L., Kamata M., Puig L., et al. Lebrikizumab vs other systemic monotherapies for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: network meta-analysis of efficacy. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2025;15:615–633. doi: 10.1007/s13555-025-01357-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weeda E.R., Muraoka A.K., Brock M.D., Cannon J.M. Medication adherence to injectable glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists dosed once weekly vs once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dall’Acqua W.F., Kiener P.A., Wu H. Properties of human IgG1s engineered for enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23514–23524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu E., Shaheen H., Dambkowski C., Oh J. APG777, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, binds to IL-13 with high affinity and potently blocks IL-13 signaling in multiple in vitro assays. SKIN J Cut Med. 2024;8 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lund J., Winter G., Jones P.T., Pound J.D., Tanaka T., Walker M.R., et al. Human Fc gamma RI and Fc gamma RII interact with distinct but overlapping sites on human IgG. J Immunol. 1991;147:2657–2662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilton D.J., Zhang J.G., Metcalf D., Alexander W.S., Nicola N.A., Willson T.A. Cloning and characterization of a binding subunit of the interleukin 13 receptor that is also a component of the interleukin 4 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:497–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews A.L., Holloway J.W., Puddicombe S.M., Holgate S.T., Davies D.E. Kinetic analysis of the interleukin-13 receptor complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46073–46078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Vries J.E. The role of IL-13 and its receptor in allergy and inflammatory responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ultsch M., Bevers J., Nakamura G., Vandlen R., Kelley R.F., Wu L.C., et al. Structural basis of signaling blockade by anti-IL-13 antibody Lebrikizumab. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:1330–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hale G. Living in LALA land? Forty years of attenuating Fc effector functions. Immunol Rev. 2024;328:422–437. doi: 10.1111/imr.13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdeldaim D.T., Schindowski K. Fc-Engineered therapeutic antibodies: recent advances and future directions. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:2402. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15102402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim X., Winter E., Nograles K., Thankamony S., Dillinger L., Dambkowski C. APG777, anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody, demonstrates extended half-life and sustained inhibition of type 2 inflammatory biomarkers. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024;133 [Google Scholar]

- 36.European Medicines Agency Adtralza (tralokinumab) Summary of Product Characteristics. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/adtralza-epar-product-information_en.pdf Available at:

- 37.Food and Drug Administration Adbry (tralokinumab) Prescribing Information. 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/761180s001lbl.pdf Available at:

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.