Abstract

Background:

Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) is the only disease-modifying treatment for allergic rhinitis (AR), allergic asthma, and, potentially, atopic dermatitis (AD) in children. Despite demonstrated efficacy, AIT remains underutilized in the United States. Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) both reduce symptoms and medication use, although much supporting evidence comes from non-U.S. studies by using extracts not approved domestically. Moreover, most U.S. trials of multiallergen SCIT lack rigorous placebo controlled data.

Objective:

The objectives were to examine current evidence on pediatric AIT, evaluate clinical efficacy and safety, and highlight key research gaps, particularly within the U.S. context.

Methods:

A literature search was conducted by using terms that included pediatric AIT, SCIT, SLIT tablets; SLIT drops; and off-label SLIT. The review focused on AIT for AR, asthma, and AD in children, with comparative analysis of SCIT and SLIT in terms of efficacy, safety, and preventative potential.

Results:

Both SCIT and SLIT are effective for AR and, to a lesser extent, asthma and AD. SLIT tablets offer the advantages of at-home use and a favorable safety profile but in the U.S. are limited to single allergens, which poses challenges for patients who were polysensitized. AIT shows potential for tertiary prevention, such as delaying asthma onset or reducing new sensitizations, although more U.S.-based pediatric data are needed. SCIT carries a risk of systemic reactions; SLIT maintains excellent safety. Knowledge gaps remain with regard to optimal treatment duration, extract formulation, and multiallergen use in children who are polyallergic.

Conclusion:

AIT is a valuable disease-modifying option for pediatric allergic diseases, but broader U.S. adoption is hindered by regulatory, reimbursement, and evidence limitations. Shared decision-making is critical to align treatment with patient needs. High-quality U.S.-based studies are essential to optimize care and long-term outcomes for children who are allergic.

Keywords: Pediatric allergen immunotherapy, subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT), sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), SLIT off-label drops, SLIT tablet (SLIT-T), SLIT drops, new allergen sensitizations, multi-allergen immunotherapy, allergic rhinitis, asthma prevention, SCIT for atopic dermatitis, long-term efficacy, real-world evidence, immunologic tolerance, evidence gaps in AIT

Allergic rhinitis (AR), one of the most common chronic diseases in children, is estimated to affect 10.48% of pediatric patients when physician-diagnosed and 18.12% when self-reported in the United States.1 According to 2005 data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Center for Health Statistics, treating AR in adults and children is estimated to cost $11.2 billion annually.2 Having AR is significantly associated with the development of asthma (odds ratio [OR] 3.82 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 2.92– 4.99]).3 Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) both demonstrate efficacy in reducing AR and asthma symptoms while decreasing medication needs. Unlike pharmacotherapy, allergen immunotherapy (AIT) represents the sole treatment modality capable of modifying underlying T helper (Th) type 2 mediated immune responses.4,5 AIT has also been shown, with a moderate degree of certainty, to improve symptoms and quality of life (QoL) in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD). Moreover, the role of SCIT and SLIT in tertiary prevention of allergic disease progression is of major importance for the pediatric population. Whereas both SCIT and SLIT are associated with a high percentage of local reactions, systemic reactions (SR) are less frequent and less severe with SLIT. This article reviews the mechanism of action, indications and contraindications, efficacy, safety, and patient preference considerations of SCIT, standardized European and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved SLIT tablets (SLIT-T), standardized European SLIT drops on-label (SLIT-d-onL), and U.S. SLIT drops off-label (SLIT-d-offL).

AR, the most common indication for AIT in the United States, typically starts in childhood.6 In addition to allergic symptoms of the nose and eyes, many of these children have comorbid conditions, including asthma, sinusitis, conjunctions, and/or AD. These conditions significantly impair QoL and school performance, and create a substantial economic burden for both families and the health-care system. In 2021, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 27.2% of children in the United States have an “allergic condition,” defined as seasonal allergy, eczema, and/or food allergy.7 The percentage of U.S. patients (children and adults) placed on SCIT is estimated to be between 2% and 9% of those diagnosed to have AR, with 43% of these patients having comorbid asthma.8,9

Asthma is reported to affect 7% of U.S. children ages < 18 years, with 90% of these patients having allergic asthma, for an estimated total population of 3.7 million who could potentially be candidates for AIT.7 Whereas the information is limited and based predominantly on survey data, it is estimated that, in the United States, 45% of children with asthma have “controlled asthma,” a required criterion before starting AIT.10 Unfortunately, uncontrolled asthma is more prevalent among non-Hispanic ethnicities, children ages 0–9 years and 15–17 years, and in households with an annual income < $25,000.10 Asthma that is severe and uncontrolled with pharmacotherapy is a relative contraindication for initiating SCIT.11

In the United States, the prevalence of AD is estimated to be 10.8% in children ages 0–17 years, being highest in ages 6–11 years and in non-Hispanic Black children (14.2%).12 Although a study from the REAl-world effeCTiveness in allergy immunotherapy data base indicated that, among children receiving AIT, 20% had AD as a comorbidity, there are no available data on how many children have been started on AIT specifically to treat their AD.13 The 2023 Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters (JTFPP) Atopic Dermatitis guidelines14 suggest AIT for patients who are refractory, intolerant, or unable to use mid-potency topical treatments.

DEFINING THE TERMINOLOGY

When summarizing the evidence, it is important to be consistent in describing and defining the administration method, the allergen extract formulation used, the updosing schedule, the maintenance dose, the short- versus long-term efficacy, the single versus multiple allergen sensitization, the use of single or multiple allergens for treatment, and the study design. Many of these terms as used in this article are defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of terms

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; SLIT-GTT = Sublingual immunotherapy drops; HDM = house-dust mite; +sIgE = specific immunoglobulin IgE; ARC = allergic rhinitis conjunctivitis; SR = systemic reaction; Treg = T regulatory cells; IgG4 = immunoglobulin G4.

MECHANISM OF ACTION OF SCIT AND SLIT

The proposed mechanisms of immune tolerance are felt to be very similar for both SCIT and SLIT. Shortly after initiation of AIT, there is desensitization of mast cells and basophils, with diminished release of histamine and tryptase on allergen exposure.15 The induction of regulatory T cells, which release interleukin 10 and transforming growth factor β, results in suppression of the effector cells involved in allergic inflammation, including mast cells, basophils and eosinophils, T helper type 2 cells, and inflammatory dendritic cells. Furthermore, AIT prevents seasonal increases in group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Interleukin 10 and transforming growth factor β induce immunoglobulin class-switching from allergen specific immunoglobulin E (sIgE) to sIgG4 and sIgA, which compete with sIgE for allergen biding to mast cells and basophils. Furthermore, immature transitional B regulatory cells contribute to the development of allergen tolerance. These events result in a decreased sIgE-to-IgG4 ratio and reduced mast cells and eosinophils in the tissues.15 These changes are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of allergen-specific Immunotherapy. (Reproduced with permission from Ref. 15).

EVALUATING THE EVIDENCE FOR USING SLIT AND SCIT

The recognized criterion standard for guideline development uses the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology.16 Recommendations are developed by using an evidence-to-decision framework that incorporates problem priority, desirable effects, undesirable effects, certainty of evidence, values and preferences, balance of effects, resources required, certainty of evidence of required resources, cost-effectiveness, equity, acceptability, and feasibility. Although not all guidelines use such a rigorous method for developing recommendations, these elements provide the clinician with a mental checklist for approaching the patient for whom AIT is being considered.

Most well-controlled trials for both SCIT and SLIT focused on pollen and house-dust mite (HDM), with very few published trials on animal dander and fungi. When reviewing the published studies on AIT since the publication of the 2011 SCIT practice parameter,11 >90% of the new studies, for both children and adults, are with single allergens, are predominantly conducted in Europe, and use aluminum hydroxide (67%) or microcrystalline tyrosine (17%) absorbed extracts or allergoids (20%), which are not available in the United States (Table 2).17–19 SLIT-T has been the most widely studied form of SLIT in both Europe and the United States. The FDA-approved SLIT tablets are summarized in Table 3. A significant number of SLIT-d-onL studies conducted in Europe by using standardized aqueous extract have also been published and are included in most of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses herein reviewed.

Table 2.

Types of allergen extracts for SCIT used in the United States and Europe*

SCIT = Subcutaneous immunotherapy; SR = systemic reaction; IgE = immunoglobulin E.

Ref. nos. 17, 18, 19, 55 were used to develop this table.

Table 3.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved sublingual tablets (2025)

EoE = Eosinophilic esophagitis; AIT = allergen immunotherapy; IR = index of reactivity (historical European unit used for standardizing SLIT extracts; not equivalent across products); SQ-T = standardized quality tablet (Allergologisk Laboratorium København [ALK] unit to standardize allergen potency, commonly used in Grastek and Oralair); BAU = bioequivalent allergy unit (used in U.S. standardized allergen products); Amb a 1 = major allergen of ragweed (used to standardize Ragwitek); HDM = house-dust mite; SQ-HDM = ALK unit specific for HDM SLIT tablet.

Allergists in the United States almost exclusively use unmodified aqueous extracts for SCIT and SLIT-d-offL, both mixable in the office for multiallergen extract vials. After the publication of the 2011 JTFPP third update on SCIT,11 only two adult (no pediatric) U.S. studies looked at the efficacy of SCIT when using aqueous extracts and both of these studies used biologics concomitantly with SCIT.20,21 Therefore, most of the recent evidence on SCIT efficacy and safety reviewed here derives from studies conducted outside the United States by using allergen extracts that are not available to U.S. allergists. Likewise, there have been very few peer-reviewed publications on the efficacy of aqueous SLIT-d-offL in the United States. Although no pediatric SLIT-d-offL efficacy studies could be found, there have been four SLIT-d-offL studies in adults, one that showed no improvement compared with placebo22 and three that showed efficacy with symptom reduction, improved bronchial allergen challenge thresholds, and/or an increase in sIgG4 levels.23–25 A work group of the American Academy of Otolaryngic Allergy published a dosing document for SLIT-d-offL in AR, based on an evidence-based literature review that used dosing recommendations previously published for SCIT and SLIT.26 This article did not cite any published studies on the efficacy of dosing schedules when using aqueous extracts for SLIT-d-offL. However, an Italian study that used standardized sublingual drops demonstrated that three daily doses were more effective than once-daily dosing for low-dose SLIT-d-onL.27

SINGLE- VERSUS MULTIALLERGEN SCIT AND SLIT

Most of the published short- and long-term efficacy studies on AIT used a single or a mixture of related allergens for AIT. However, this does not reflect the predominant clinical practice in the United States for either SCIT or SLIT-d-offL.

Multiallergen SCIT

In a U.S. survey of SCIT, 45% of allergy specialists reported treating with > 10 allergen extracts.28 It is likely that these were formulated in multiple vials because the responding specialists reported administering an average of 2.3 injections per SCIT visit.28 Whereas multiallergen aqueous SCIT and aqueous SLIT-d-offL in patients who are polysensitized are the most common types of AIT used in the United States, there are very limited multiallergen controlled trials that use U.S. products. Four studies, two in children29,30 and two in adults31,32 were conducted from 1965 to 1997. The two adult studies showed efficacy when using two or more unrelated pollen extracts.31,32 Of the two pediatric studies, the 14-year prospective placebo controlled study showed that multiallergen SCIT improved the long-term prognosis of children with bronchial asthma with both symptom reduction and a higher rate of asthma remission.29 The other pediatric study did not find any difference in asthma medication scores (MS) in children with moderate-to-severe asthma when comparing the 2-year multiallergen SCIT group with placebo.30 Since 2010 there have been three controlled35–37 and four observational studies,36,37 some including children, that supported the use of multiallergen SCIT, but none of these were conducted in the United States.33–38 In a 2022 review of multiallergen SCIT, the researchers concluded that there is no evidence from placebo controlled trials that multiallergen SCIT can reduce symptoms more than treatment with one clinically relevant allergen and that dose-finding trials for multiallergen SCIT are inadequate.38

There have been no multiallergen SCIT long-term efficacy studies. Recommendations for multiallergen SCIT continue to rely predominantly on the evidence derived from clinical experience and observations of U.S. allergists and the testimonials of patients treated in clinical practice over the past 100 years. There is an urgent need for real-world evidence from observational trials because this is likely to be the only practical, cost-effective means of showing multiallergen effectiveness. The establishment of SCIT registries that collect data by using standard protocols may be the best strategy to capture this very valuable real-world evidence.40

Multiallergen SLIT

The evidence for the use of multiallergen SLIT-T in patients who are polysensitized is very limited and has been predominantly restricted to the use of two tablets with unrelated allergens.41,42 An open-label 4-week study in adults showed that using timothy and ragweed SLIT-T concurrently was well tolerated.43 The efficacy of multiallergen SLIT-d-offL is even more limited. A 2009 randomized double-blind, placebo controlled trial that used SLIT-d-offL compared monotherapy with timothy grass extract with both a mixed extract of timothy grass combined with nine other pollens and with placebo.44 There was no significant difference between either the treatment group or the placebo for symptoms and MS, although biomarker and nasal challenge studies showed a benefit for the monotherapy group.44 One U.S. pilot study with 16 participants did not find any significant difference in efficacy compared with placebo, whether when using single- or multiallergen SLIT-d-offL in patients who were polysensitized.43

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

AIT is indicated for patients with AR, allergic asthma, and moderate-to-severe AD who have evidence of IgE sensitization to one or more clinically relevant allergens and who are on appropriate medical treatment and environmental control.46–48 After a shared decision-making discussion with the allergist, patients who choose AIT typically have moderate-to-severe symptoms that interfere with daily activities or sleep despite pharmacotherapy, or they prefer to avoid long-term medication use due to adverse effects or personal preference.46 However, AIT may also be considered for patients with AR who wish to pursue the potential long-term benefits, such as modifying the natural course of the disease and potentially preventing the development of comorbid conditions, particularly asthma.47–49 AIT has also been shown to reduce disease severity and improve QoL in patients with AD.14,50,51

The 2011 JTFPP AIT practice parameter11 states that medical conditions that reduce the patient’s ability to survive a systemic allergic reaction or the resultant treatment are relative contraindications for AIT. They provide several examples of patients’ diagnosis for which alternatives to AIT should be considered, with poorly controlled or severe asthma uncontrolled by pharmacotherapy being most applicable to pediatric patients. The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) AIT guidelines52 likewise list the contraindications for AIT, with uncontrolled or severe asthma being most relevant for children.46 Both guidelines11,46,52 emphasize that patients placed on AIT should be cooperative, compliant, and adherent to treatment. It is more important to have a shared decision-making conversation with the patient before initiation of AIT rather than setting absolute indications or contraindications for AIT. This conversation should discuss both the risks and benefits of AIT, the options of SCIT versus SLIT, and the alternative pharmacological options. Examples of contraindications, relative contraindications, and potential risk factors for AIT for both children and adults as provided by the most recent AIT guidelines by the JTFPP11 and the EAACI46 are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Risk factors for systemic reactions to allergen immunotherapy

JTFPP = Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; EAACI = European Allergy Asthma and Clinical Immunology; AIT = allergen immunotherapy; ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Adapted from Ref. 11.

Adapted from Ref. 46.

AVAILABLE ALLERGENS AND DOSING GUIDELINES IN THE UNITED STATES

Allergy specialists typically use identical dosing strategies for children as for adults for both SCIT and SLIT because published studies indicate that there is no difference in local reactions or SRs between these age groups.53–56 A standardized HDM SLIT-T pediatric study found that the efficacy, safety, and immunologic changes were not dependent on body weight.57 The recommendation for the length of treatment for SCIT and SLIT is 3–5 years of maintenance therapy in both children and adults. The recommended maintenance doses for SCIT when using standardized and nonstandardized allergen extract were published in the 2011 JTFPP AIT practice parameter11; the only change is the substitution of ultrafiltered dog (15 µg of can f 1) for dog acetone precipitated extract.58

EFFICACY OF SCIT AND SLIT IN AR IN CHILDREN

U.S. guidelines11,59 and international60–62 consensus statements state with a high degree of certainty that SCIT and SLIT are safe and effective in children to treat AR and rhinoconjunctivitis.11,59–62 This recommendation is strong for SCIT and SLIT tablets, and moderate for non-U.S. SLIT-d-onL.61 The A systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCT) by Wise et al.61 found, with a moderate certainty of evidence, that SCIT improves asthma and rhinitis symptoms in children. A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 studies with 10,813 children with AR (SLIT, 4122; SCIT, 1852; no AIT, 4839) showed, in direct comparisons, that SLIT and SCIT produced comparable reduction in symptom (three studies) and MS (two studies) whereas SLIT was statistically superior in reducing symptom and/or MS (one study).62 In a subset analysis, it was found that, when AIT was used for >24 months, symptom scores were significantly lower in the SCIT group compared with the SLIT group (p < 0.001).62 When considering indirect comparisons, there was no significant difference in symptom scores, MS, new sensitization, and development of asthma between the SLIT and SCIT groups; however, SLIT had a lower incidence of treatment-related adverse events (risk ratio [RR] 0.45).62 Other studies concurred that there is no significant difference in the efficacy of SLIT between children and adults.63–65 Compared with pharmacological treatment, both SLIT and SCIT were superior for reducing symptoms scores in pediatric AR.62 Whereas most studies have excluded children < 5 years, there is no evidence to suggest that the efficacy and safety would be any different.54

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 160 studies with adults and children showed efficacy of SCIT and SLIT in both adults and children.55 Based largely on this systematic review, the EAACI 2017 guidelines46 for SCIT for AR concluded that short-term use of SCIT for seasonal and perennial AR was grades A and B for adults and grades B and C for children, respectively. Most U.S. allergists treat both seasonal and perennial allergens with perennial SCIT. A 2013 randomized double-blind, placebo controlled 3-year trial found that perennial SCIT was more effective than preseasonal SCIT for pollen allergy.66

In the United States, timothy grass and ragweed SLIT-Ts are only FDA approved for pre- and coseasonal administration, whereas the HDM tablet is approved for use throughout the year and the 5-grass tablet may be continued year-round for 3 consecutive years. Although there are no studies that directly compare the efficacy of perennial versus pre- and coseasonal SLIT-T for pollen-induced AR, an individual patient data meta-analysis of three open, prospective, observational trials of birch or 5-grass SLIT-d-onL did not find any difference in coseasonal and perennial administrative regimens.67 There are no head-to-head comparative studies on the safety of the pre- and coseasonal compared with the perennial SLIT regimen but the safety profiles for the 5-grass and the single-grass SLIT-T US clinical trials were similar.68 The pre- and coseasonal SLIT-T grass pollen dosing is associated with lower costs and potentially improved adherence.

EFFICACY OF SLIT AND SCIT FOR ASTHMA

Compared with AR, there are fewer studies in children on the use of AIT for the treatment of asthma. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 RCT trials found, with a moderate certainty of evidence, that SCIT reduces long-term asthma medication use but found low strength evidence that SCIT improves QoL and Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1).69 Similarly, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 RCT trials that used SLIT found low-quality evidence that SLIT improves asthma medication use and FEV1; there was insufficient evidence to determine the effect of SLIT on asthma symptoms and health-care utilization.69 A previous 2017 GRADE evidence-based guideline found only low-quality evidence to support the use of either SCIT or SLIT for the treatment of asthma.70 A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 RCTs that used HDM SCIT in children with asthma showed a decrease in short-term asthma scores (standardized mean difference [SMD] −1.19 [95% CI, −1.87 to −0.50]) and asthma medications (SMD 1.04 [95% CI, −1.54 to −0.54]).71 SCIT was found to improve QoL, to reduce annual asthma attacks and allergen-specific airway hypersensitivity; but there was no significant improvement in pulmonary function, asthma control, or number of hospitalizations.71 None of these studies reported on long-term efficacy. The benefit of SCIT and SLIT may depend on multiple factors, including asthma severity and the degree of asthma control, the allergen, the maintenance dose, and the duration of treatment.

EFFICACY OF AIT FOR AD

A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis, including 23 RCTs with 1957 participants, median age of 19 years (range of means, 4–34 years), on AIT, predominately HDM, concluded that both SCIT and SLIT could lead to significant improvements in AD.50 There was a 50% reduction in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis scores in 40% of patients receiving AIT versus 26% in the control groups, giving an RR of 1.53 (95% CI, 1.31–1.78).50 A ≥ 4-point improvement in the Dermatology Life Quality Index was shown in 56% of the actively treated versus 39% in controls (RR 1.44 [95% CI, 1.03–2.01]). Adverse events were higher in the SCIT (66%) and SLIT (13%) compared with the controls, 41% and 8%, respectively. The effect of the AIT on sleep disturbance and AD exacerbations was uncertain.50

THE PREVENTATIVE BENEFIT OF AIT

A significant potential benefit of starting AIT in young children is to prevent the development of allergies, new sensitizations, or asthma in patients with AR. Primary prevention aims to stop a disease process from starting, e.g., preventing allergic sensitization in individuals who are not allergic. Secondary prevention targets the onset of disease symptoms, e.g., preventing sensitized patients from developing a symptomatic allergic disease, e.g., AR. Tertiary prevention aims to prevent the development of new allergic diseases, new sensitizations, and/or reduce the impact of established diseases, such as preventing patients with AR from developing asthma, preventing asthma progression, or reducing the need for asthma medications.72,73 Achieving long-term tertiary prevention (during or at the end of AIT) is more difficult than achieving short-term (during AIT) tertiary prevention.

Long-Term Tertiary Prevention of Asthma

The 2002 landmark Preventative Asthma Treatment74 studied 147 subjects, 16–25 years of age, with the active group receiving grass and/or birch pollen SCIT for 3 years. This study demonstrated the prevention of asthma during the 3 years of treatment and for 7 years after SCIT cessation, with an OR for no asthma of 4.6 (CI, 1.5–13.7) in the SCIT group compared with the control group.74–76

Additional studies as discussed below have examined the long-term preventive effect of AIT on asthma, yielding less convincing results. In the Mite Allergy Prevention Study,77 a prospective double-blind, placebo controlled trial of 111 infants who were skin-test-negative and at high risk (two or more first-degree family members with an atopic disease) who received HDM SLIT for 12 months, there was no effect on wheezing. A follow-up study 6 years later compared these children with an observational birth cohort of infants at high risk who did not receive AIT.78 Although a trend toward reduced asthma rates was observed in the HDM-treated group, this did not reach statistical significance, and no differences were found between the groups in terms of lung function, Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FeNO), or bronchial hyperreactivity.78

A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis that included 12 RCTs and 12 nonrandomized studies of intervention conducted in adults and/or children looked at the effect of SCIT or SLIT on asthma prevention and found for the random-effect analysis a significant decrease in the risk of developing asthma, but this was not significant in the sensitivity analysis.79 After cessation of treatment, no SLIT and only three SCIT studies had a follow-up > 3 years. In subset analysis, children who received AIT (eight studies) showed a significant asthma preventative effect (RR 0.71 [95% CI, 0.47–0.88]), with SCIT and SLIT providing equal protection. However, when asthma was defined by using mixed criteria of pulmonary function, symptoms, and medications, or defined by medication use only, the results were no longer significant.79

Short-Term Tertiary Prevention of Asthma

A 2004 randomized, open-label study that treated children who were monoallergic with 3 years of grass SLIT found that the control group was 3.8 times (95% CI, 1.5–10.0) more likely to develop asthma at the end of the 3-year SLIT treatment.80 However, there was no long-term follow-up of these children. In another RCT, patients with AR (n = 46) treated with 3 years of Der P SCIT were less likely to develop asthma (p < 0.05) compared with the control group.81

In a random-effects meta-analysis of 32 studies, which included both SCIT and SLIT, there was no conclusive evidence that AIT reduced the onset of a first allergic disease.82 However, AIT reduced asthma development in patients with preexisting AR in the short term (RR 0.40 [95% CI, 0.29–0.54]), but this protective effect was not sustained long-term.82 The 5-year SQ grass SLIT-T asthma prevention study randomized 812 children (5–12 years of age) with AR but without asthma, to 3 years of SLIT or placebo and followed up for 2 years after discontinuation of SLIT-T.83 Time to asthma onset, defined by reversible lung function impairment, did not differ between the active treatment and placebo groups. However, for the entire 5-year period, asthma symptoms and the use of asthma medications were reduced in the SLIT-T–treated group.81,83

The randomized open-label study by Marogna et al.84 enrolled children with rhinitis only (40.3%), mild intermittent asthma (49.7%), and/or methacholine positivity (56.9%) at baseline. Three years of single-allergen SLIT produced marked improvements in the treatment group: children with rhinitis only increased to 86.9%, mild intermittent asthma decreased to 11.5%, and methacholine positivity fell to 17.7%.84 All improvements were statistically significant compared with both baseline and controls (p < 0.001).84 However, long-term follow-up data are not available.

A comparison study of 3- versus 5-year SCIT for HDM in children with preexisting asthma found significant asthma remission in both groups, with greater reduction in inhaled corticosteroid use in the 5-year treatment group at study completion.85 This benefit was not sustained 3 years after treatment cessation, which suggests no long-term advantage of extended therapy.85 A separate, real-world, large cohort study in adults and adolescents with concurrent asthma demonstrated that AIT prevented the progression of asthma severity, as classified by the Global Initiative for Asthma.86,87

Prevention of New Sensitizations

The aforementioned study by Marogna et al.84 also demonstrated that the controls had significantly higher odds of developing new sensitizations compared with the SLIT group (OR 16.85 [95% CI, 5.74–49.13]). In supporting this finding, a 3-year HDM SCIT study reported new sensitizations in 15% of the treated participants compared with 47% of the controls (p < 0.05).16 A large systematic review of 18 AIT studies (SLIT/SCIT), which included 1049 children, found low-grade evidence that supports AIT’s preventative effect on new allergen sensitizations.88 The Mite Allergy Prevention Study78 in infants who are not sensitized showed that HDM SLIT reduced sensitization to common allergens (p = 0.03), although no protective effect occurred against HDM itself. However, these findings contrast with the 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis by Kristiansen et al.,82 which found no short- or long-term reduction in new sensitization with either SCIT or SLIT.

Summary of Preventative Effect of AIT

A 2024 pooled analysis of 33 studies of children and adolescents, including many of the individual studies reviewed above, concluded that primary prevention showed no allergen-specific effect on new sensitizations, that secondary prevention may induce regulatory T-cell–mediated immunotolerance, and that tertiary prevention with grass and/or tree pollen AIT could prevent disease progression from AR to asthma with the data on HDM and other allergen AIT being inconclusive.73 Based on indirect comparisons, the preventative effect of AIT was similar for SLIT and SCIT.73 In this analysis, the use of heterogeneous allergen mixtures, the most common approach in the United States, did not show any clear preventive effect.73

In summary, the tertiary preventive effect of SCIT and/or SLIT on the development of asthma in patients with AR as well as the prevention of new allergen sensitizations and the progression of asthma severity is supported by limited evidence, whereas primary prevention and secondary prevention have not been convincingly demonstrated.

MULTIMORBIDITY

There is evidence that suggests that AR alone, AR plus asthma, AR plus allergic conjunctivitis, and AR plus asthma plus allergic conjunctivitis represent four distinct phenotypes.89 For example, the presence of ocular symptoms is associated with more severe AR; furthermore, ocular symptoms are more common in AR plus asthma than in AR alone.90,91 Although research is limited, evidence indicates that in individuals with multimorbidity—such as allergic rhinitis co-existing with asthma or eczema—the severity of the primary disease tends to be greater, as demonstrated by lower FEV1 and poorer clinical outcomes.92–94 Although results of studies indicate that AIT is effective in patients with multimorbidity, it is unknown whether the response, e.g., efficacy, time to onset, and long-term benefit after cessation of treatment, varies depending on the specific combination of comorbidities and allergens treated.95,96

LONG-TERM EFFICACY OF AIT

Long-term AIT efficacy, benefit after cessation of treatment, is less well studied than short-term AIT efficacy (during or at the end of treatment). All of the studies reviewed, as listed and referenced in Table 5 and 6, with the exception of the 2002 Moller study72 used a single allergen or a mixture of very closely related allergens.

Table 5.

SCIT long-term follow-up RCT and/or observational studies in children 1995–2024 (≥3 years treatment, ≥2 years follow-up after cessation of SCIT)

SCIT = Subcutaneous immunotherapy; RCT = randomized controlled trial; DBPC = double-blind placebo-controlled; IgG4 = immunoglobulin G4; HDM = house-dust mite; AR = allergic rhinitis; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; Tx = Treatment; RQLQ = Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Table 6.

SLIT long-term follow-up RCT and/or observational studies in children 1995–2024 (≥3 years treatment, ≥2 years follow-up after cessation of SLIT)

SLIT = Sublingual immunotherapy; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SCIT = subcutaneous immunotherapy; HDM = house-dust mite; SLIT-d-onL = SLIT drops on-label; PFT = Pulmomary function tests; SLIT-T = SLIT tablet; DBPC = double-blind placebo-controlled; RC = randomized, controlled; TNSMS = Total Nasal Symptom and Medication Score; CSMS = combined symptom medication score.

Both children and adults are recommended to complete from 3–5 years of SCIT or SLIT for the best long-term outcomes. A 2023 observational study evaluated the long-term efficacy of HDM-SCIT administered under a cluster buildup schedule in 58 children compared with adults.97 All the patients were treated for 3 years with SCIT and then followed up for ≥3 years after cessation of SCIT. The children showed improvement in total nasal symptom scores at completion of the 3 years of SCIT and even further improvement 3 years after cessation of treatment (p = 0.030).97 In children, at a median follow-up of 6 years and a range of up to 13 years (three children), Total nasal symptom scores, MS, combined symptom MS, and rhinitis QoL questionnaire scores remained significantly lower than at baseline.97 The degree of improvement correlated with the severity of AR at baseline (r = 0.681, p < 0.001).97 The key studies published from 1995 to 2024 that support the long-term (2–13 years) efficacy of SCIT in children are summarized in Table 5.

In a 10-year prospective parallel-group, controlled HDM study, pediatric patients with asthma/AR were treated with 4–5 years of SLIT and then observed for 4–5 years after cessation of therapy.98 Compared with baseline, there was a significant reduction for the presence of asthma (p < 0.001) and the use of asthma medications (p < 0.01), whereas no difference was observed in the control group.98 Most SLIT long-term efficacy studies have been for only 2 years after cessation of treatment, as reflected in Table 6, which summarizes the key studies on the long-term efficacy of SLIT in children published from 1995 to 2024.

When assessing the long-term efficacy of SCIT and SLIT in children, the balance of evidence supports long-term efficacy of single-allergen AIT. There is inconclusive evidence as to whether the long-term efficacy achieved with single-allergen AIT in patients who are polysensitized is as effective as single-allergen AIT in patients who are monosensitized. Whereas AIT for < 3 years may provide long-term efficacy, the overall evidence suggests that a minimum of 3 years is needed for long-term allergen-specific tolerance.99–101 Whereas 70% of U.S. allergy specialists recommend 5 years of SCIT, 20% and 35% of patients complete 5 and 3 years of SCIT, respectively.102 The sustainability of clinical benefits beyond 5 years after cessation of AIT is largely unknown; additional research is warranted to confirm long-term outcomes.

SAFETY OF SCIT AND SLIT

SRs: Incidence and Presentation

SCIT is well tolerated in both children and adults, with the incidence of 1 in 160,000 visits for severe or near-fatal allergic reactions, 1 per million injections for severe anaphylaxis, and 1 per 7.2 million injection visits for fatal reactions.103,104 Of the 10 fatalities reported in the most recent U.S. survey (2008–2018), of those reporting patient age (8/10 fatalities), three were in teenagers but none were in children < 12 years of age.105 When adjusted for asthma, gender, and phase of SCIT, children do not have a significantly higher rate of SRs compared with adults; however, in one retrospective chart review, grades 1 and 2 SRs were 1.89 times higher in children compared with adults (p < 0.015), whereas grades 3–4 SRs were more frequent in adults.106

Data from the European Anaphylaxis Registry from 10 European countries from 2007 to 2023 indicated that, when anaphylaxis is defined as having two or more organ systems involved, only 1.1% (173 patients) could be attributed to AIT.107 Children ages 5–12 years and adolescents ages 13–18 years accounted for 55 and 30 patients, respectively.107 Boys made up a larger proportion of pediatric reactors (68%), whereas women were predominant reactors in adults (63%). Children presented with skin and/or mucosal and respiratory symptoms most commonly, whereas adults presented with skin and/or mucosal and cardiovascular symptoms.107 No grade 4 reactions were reported in children. One fatal case involved a 19-year-old patient receiving pollen SCIT who was reported as having “ongoing asthma.” The SR onset was within 30 minutes of receiving SCIT, was treated aggressively but with fatality 30–60 minutes after the onset of anaphylaxis.107

SRs to SLIT-T are very rare, reported to be 0.02% (versus 0.01% for placebo) in clinical trials (active = 8200; placebo = 7033), with none of the three treatment-related reactions being life-threatening.108 In these trials, epinephrine was administered in 0.2% of the patients on SLIT-T, 6 for systemic and 10 for local reactions.108 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 RCTs on single allergen SLIT safety (2001–2021), including adults and pediatric patients (no subset analysis) found a 1.09% incidence of systemic adverse effects and 0.13% anaphylaxis.109 Surveillance data for SCIT-d-offL in the United States, generally multiallergen, identified systemic allergic reactions in 1.4% of patients between 2012 and 2013, with nine grade 2 (0.3%) and one grade 3 (0.03%) reactions.110 There have been no confirmed fatalities from SLIT in the United States or Europe when using tablets or aqueous products.

To help explain the remarkably low SR rate in SLIT compared with SCIT, it is possible that the antigen processing by dendritic cells within the sublingual mucosa may lead to a tolerogenic phenotype, thereby reducing the proinflammatory cascade.111 Conversely, SCIT may lead to systemic absorption, triggering an inflammatory cascade.112 Nonetheless, U.S. guidelines59 as well as worldwide guidelines recommend that the first dose of SLIT be administered under medical supervision.59,113

Furthermore, the FDA package labeling of SLIT-T requires the prescription of and training in the use of an epinephrine autoinjector for patients using SLIT-T. The FDA was concerned about SLIT-T reactions that occur at home when the patient was not under medical supervision.114 An analysis of adverse reactions in 13 clinical trials (8152 patients) when using SLIT-T for timothy grass (5 trials), ragweed (5 trials), and HDM (11 trials), reported 16 trial-related epinephrine administrations: 6 for SRs and 10 for severe local reactions. Although not diagnosed to be anaphylactic, chest discomfort, cough, and dyspnea were described in some patients.115 Of these 16 patients, 5 occurred > 1 week after starting treatment.115

SRs: Risk Factors

When collecting data on SRs from AIT, the definition, classification, and comparison of SRs in SLIT versus SCIT can be challenging. In SLIT, the very commonly described oral pruritus, throat irritation, ear pruritus, oral paresthesia, mouth edema, stomatitis, pharyngeal edema, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are classified as local application-site reactions. If these same symptoms presented after SCIT, particularly in combination, it would be considered an SR.

Risk factors for SRs in SCIT and SLIT include a history of anaphylaxis or mast cell disorder, SRs to previous SLIT or SCIT administration, uncontrolled and/or moderate-to-severe asthma, a high sensitization pattern or SR during skin-prick testing, pollen polysensitization, patients who were highly sensitized and pollen allergic during peak pollen season, use of aqueous compared with alum absorbed (non–United States) or allergoids (non–United States), and treatment with grass extracts.49,116,117 Relative risk factors include the concurrent use of β-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.118 Increased risk at the time of AIT administration is likely present when any of the following are present: (1) highly active allergic symptoms, (2) sleep deprivation, (3) presence of extreme emotional stress, (4) during a concurrent infection, or (5) after recent high-intensity physical exercise. Furthermore, U.S. specialists may increase the risk of an SR when there is excess dose escalation during buildup (SCIT mainly), failure to reduce the dose for new extract vials (SCIT mainly), failure to reduce the dose after treatment interruption (SCIT or SLIT), and an accidental wrong dose or overdose (SCIT mainly).46 Primary risk factors for fatal SCIT include uncontrolled asthma, previous SRs, administration during the peak pollen seasons, dosing errors, and delayed recognition or treatment of anaphylaxis.105,119

Risk factors for severe SRs from SLIT include receiving the first dose (which should be administered under medical supervision), overdose of multiallergen SLIT, uncontrolled asthma, and previous SRs to SCIT or SCIT-induced asthma exacerbations.120 Contraindications for SLIT-T in the United States are severe, unstable, or uncontrolled asthma; a history of a severe SR (to any allergen) or severe local reactions to SLIT; and a history of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).121 Several studies found no significant differences in the safety of SLIT between children and adults.63–65

When anaphylaxis occurs after SCIT and/or SLIT, children are more likely to present with respiratory symptoms (92% children, 66% adults), whereas adults have more cardiovascular (78% adults, 40% children) and gastrointestinal symptoms (42% adults, 20% children).107

Local Adverse Effects

Local reactions to SCIT occur in 26–86% of patients and consist of local itching, redness, swelling, and heat at the injection sites.122 Local reactions can be treated with cold compresses, premedication with nonsedating antihistamines, and temporary dose adjustment for recurrent, persistent, large (>4 cm) local reactions that last > 24 hours. Only 27% of all local reactions are followed by another local reaction on the subsequent visit, which suggests that dose-adjustments are usually not necessary.123 Local reactions have only a 17% predictive value for the development of future SRs.124

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 studies and 7827 patients, SLIT local reactions were reported in 40.83% of the patients.109 When reviewing large clinical trials, local reactions are reported to occur in up to 70–85% of the patients, but they tend to be mild in nature and to occur most frequently in the buildup phase of treatment.125,126 Overall local adverse effects in the real world tend to be lower than those reported in clinical trials. The range of individual local adverse effects reported in large clinical trials125 and a more realistic expectation of these local adverse effects in clinical practice are summarized in Table 7.127–129 Lower gastrointestinal reactions can be challenging to assess; whereas nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are usually considered local reactions when they occur with other systemic manifestations, they should be classified as SRs.130 Only 4–8% of patients stop SLIT due to local reactions, and informing the patient to anticipate local reactions and reassuring them of the likely resolution over the first 2–3 weeks of treatment can reduce the SLIT discontinuation rate.46,109 The clinician can consider oral nonsedating antihistamines for prevention and treatment of troublesome local reactions.

Table 7.

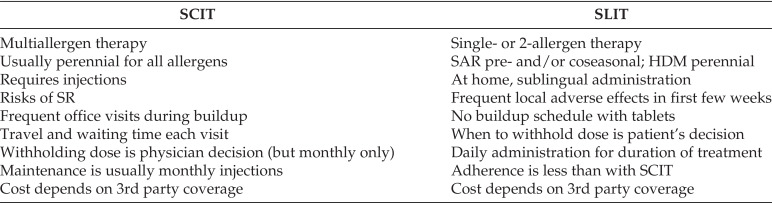

Patient preference considerations: SCIT vs SLIT

SCIT = Subcutaneous immunotherapy; SLIT = sublingual immunotherapy; SAR = Seasonal allergic rhinitis; HDM = house-dust mite; SR = systemic reaction.

AEROALLERGEN SLIT-ASSOCIATED EoE

Biopsy-confirmed EoE after aeroallergen SLIT has been documented in 16 patients: 14 with SLIT drops that involved tree pollen, grass, Alternaria, and/or dust mite allergens (9 pediatric cases)131–135 and 2 with SLIT tablets that used HDM and cedar pollen in adult patients.136,137 EoE typically manifests early in treatment, often in the buildup phase, although cases during maintenance have been reported. Symptoms consistently resolve or improve after SLIT discontinuation.

CLINICAL PATTERNS OF AIT USE IN THE UNITED STATES

SCIT remains the dominant route for inhalant AIT in the United States. Analysis of recent data indicated that 80–90% of U.S. patients receiving AIT are treated via SCIT and 10–20% via SLIT.138,139 Reports indicate that 2.6 million Americans per year receive SCIT for allergic diseases whereas a few hundred thousand receive SLIT.140 Children as well as adults in the United States are more likely to be started on SCIT (>78%) than SLIT (22%) but younger children may be more likely to opt for SLIT than adults.138 In a survey, primary care physicians who use AIT within their practice were more likely to use SLIT (68%), particularly SLIT-d-offL, than allergists (45%) and otolaryngologists (35%).141

In 2007 and 2011, when there were no FDA-approved SLIT products, only 5.9% and 11.4%, respectively, of allergists reported using SLIT.142 The proportion of allergists prescribing some SLIT products increased to 73.5% in 2018 after FDA approval for standardized grass, ragweed, and HDM SLIT-T.143 In a 2019 survey of all allergists who used SLIT, 68.6% used only FDA-approved SLIT-T, 23.4% used both SLIT-T and SLIT-d-offL, and 8.0% used only SLIT-d-offL.143 However, U.S. allergists continue to have low utilization of SLIT-T in clinical practice due, in part, to a lack of FDA-approved multiallergen protocols and the associated insurance reimbursement issues. All approved pollen SLIT-Ts require dosing to start 12–16 weeks before the season and to continue throughout the season. The initial SLIT-T dose is also the maintenance dose except for the 5-grass SLIT-T, which requires a buildup phase in children. However, SLIT-d-offL use in the United States is generally associated with a buildup phase, which allows the clinician to use a slow buildup in patients who are highly sensitive.

Practical consideration for SLIT prescribing and administration, including safety in patients with asthma, contraindications, how to handle gaps in treatment, and patient education tools for when not to administer SLIT, how to recognize a serious allergic reaction, and when to administer epinephrine have been addressed by Epstein et al.114

One of the challenges for both SCIT and SLIT is in motivating the patient to adhere to immunotherapy on a long-term basis, e.g., 3–5 years. A 2012 survey of U.S./Canadian allergists found that 25% of patients discontinue SCIT before 3 years.102 The most common reason patients gave for stopping SCIT was scheduling problems, followed by a change in reimbursement and adverse events.102 When patients continue SCIT beyond 5 years (estimated to be 10% of patients), this is due to a return of symptoms on stopping or the fear of relapse.102 In a 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis, when comparing SCIT and SLIT adherence, the RR for adherence favored SCIT (RR 1.16 [95% CI, 0.92–1.47]).144

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review145 uses a standard cost-effectiveness threshold of $100,000 to $150,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) when determining if a medical treatment is cost-effective. When comparing the cost-effectiveness of SCIT versus SLIT, one U.S. study estimated that, over 12 months, when assuming 80% compliance and clinical efficacy of 70% and 80% for SLIT and SCIT, respectively, that the QALY for SLIT (U.S. $1196) would be more cost-effective than SCIT (U.S. $2691).146 However, in a study from Portugal, the cost-effectiveness in children with HDM allergic asthma favored SCIT (€1281 for SCIT; €7717 for SLIT-T).147 Another study from Portugal evaluated the cost-effectives of SCIT and SLIT versus standard of care and similarly found SCIT to be most cost-effective per QALY (U.S. $1463 for SCIT; U.S. $8814 for SLIT).148 Both SCIT and SLIT are highly cost-effective for patients, with costs well below accepted Institute for Clinical and Economic Review145 QALY thresholds.

Shared Decision-Making for SCIT or SLIT

When allergists, based on the best available evidence, make recommendations to the patient to consider AIT, both the decision to start AIT as well as the type of AIT should be presented during a patient-centered discussion. The allergist should discuss with the patient the allergens to include in the duration of treatment, expected onset of action, the short- and long-term benefit of treatment, the time commitment and out-of-pocket cost for each treatment option, and the potential adverse effects. The shared decision-making conversation should include all of the potential risks and benefits, and consider the patient’s and their family’s values and preferences, and the acceptability of all available treatment interventions, including pharmacotherapy.149,150 Some of the patient preference considerations when comparing SCIT versus SLIT are summarized in Table 7.

CONCLUSION

AIT remains the only disease-modifying treatment option for children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and allergic asthma; and it may be disease modifying for patients with AD. An estimated 2.2% of patients with asthma or AR receive AIT.151 Several factors likely contribute to this low usage, including the following: (1) limited health care and patient awareness, (2) access to specialists, (3) time commitment, (4) insurance coverage, and (5) perceived risks.151

In the United States, multiallergen SCIT continues to be the predominant AIT modality, particularly for children who are polyallergic, given its flexibility to address sensitization to multiple inhalant allergens by using standardized and unstandardized extracts. Although SLIT prescribing has increased, primarily FDA-approved SLIT-T, due to its excellent safety profile and at-home administration, the use of SLIT remains limited relative to SCIT, especially in pediatric populations with multiple sensitizations.

Clinical trials support the short-term efficacy of the single-allergen AIT in children, with both SCIT and SLIT showing improvements in symptom scores, medication use, and QoL measures. However, evidence for multiallergen AIT efficacy and the prevention of new allergic diseases remains extremely limited. Long-term benefits are unclear because few trials have followed up patients beyond 2–3 years after treatment, which leaves questions about the duration of therapeutic effects and whether extended treatment courses would enhance sustained immune tolerance.

Significant gaps in knowledge and extract availability persist and warrant targeted investigation, including the following: (1) predictive biomarkers that can identify responders and guide treatment duration; (2) evidence for the efficacy of multiallergen SCIT when using U.S. aqueous extracts and SLIT-T and SLIT-d-offL; (3) the optimal number of allergens to include in treatment in patients who are polyallergic to achieve maximum long-term efficacy; (4) the influence of extract formulation (e.g., aqueous versus alum-precipitated or modified-allergen SCIT and aqueous SLIT-d-onL and SLIT-d-offL versus SLIT-T) on efficacy and tolerability; and (5) the availability of U.S. standardization aqueous extracts and SLIT-T for all major pollen, animal danders, and fungi allergens.

In summary, although AIT is a well-established option for pediatric allergic disease, particularly through SCIT, many critical questions remain. Addressing these evidence gaps through large-scale, well-designed pediatric studies will be essential to optimize treatment protocols, improve patient outcomes, and expand the safe, effective use of AIT in broader pediatric populations.

Footnotes

This paper was presented at the Fifth Annual Joseph A. Bellanti, M.D. Lectureship at Pediatric Grand Rounds, Departments of Pediatrics and Microbiology-Immunology, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C., May 2, 2025

REFERENCES

- 1.Licari A, Magri P, De Silvestri A, et al. Epidemiology of allergic rhinitis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023; 11:2547–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaiss MS. Allergic rhinitis: direct and indirect costs. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010; 31:375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tohidinik HR, Mallah N, Takkouche B. History of allergic rhinitis and risk of asthma; a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Allergy Organ J. 2019; 12:100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfaar O, Gerth van Wijk R, Klimek L, et al. Clinical trials in allergen immunotherapy in the age group of children and adolescents: Current concepts and future needs. Clin Transl Allergy. 2020; 10:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tosca MA, Licari A, Olcese R, et al. Immunotherapy and asthma in children. Front Pediatr. 2018; 6:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zablotsky B, Black LI, Akinbami LJ. Diagnosed allergic conditions in children aged 0–17 years: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2023; (459):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Asthma - Health, United States - CDC. 2024. Available online at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/topics/asthma.htm; accessed 26 July, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hankin CS, Cox L, Lang D, et al. Allergy immunotherapy among Medicaid-enrolled children with allergic rhinitis: patterns of care, resource use, and costs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 121:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blume SW, Yeomans K, Allen-Ramey F, et al. Administration and burden of subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis in U.S. and Canadian clinical practice.. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015; 21:982–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habte BM, Beyene KA, Patel SA, et al. Asthma control and associated factors among children with current asthma - findings from the 2019 Child Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System - Asthma Call-Back Survey. J Asthma Allergy. 2024; 17:611–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zablotsky B, Black LI, Akinbami LJ. Diagnosed allergic conditions in children aged 0–17 years: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief, no 459. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis J, Black LI. Diagnosed Allergic Conditions in Children Aged 0–17 Years: United States, 2021. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritsching B. High baseline prevalence of atopic comorbidities and medication use in children treated with allergy immunotherapy in the REAl-world effeCtiveness in allergy immunoTherapy (REACT) study. Allergy. 2023; 78:1234–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AAAAI/ACAAI JT Atopic Dermatitis Guideline Panel; Chu DK, Schneider L, et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE- and Institute of Medicine-based recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024; 132:274–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Głobińska A, Boonpiyathad T, Satitsuksanoa P, et al. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy: diverse mechanisms of immune tolerance to allergens. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018; 121:306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schünemann HJ, Brennan S, Akl EA, et al. The development methods of official GRADE articles and requirements for claiming the use of GRADE - a statement by the GRADE guidance group. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023; 159:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahler V, Esch RE, Kleine-Tebbe J, et al. Understanding differences in allergen immunotherapy products and practices in North America and Europe. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019; 144:1140. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen-Jarolim E, Roth-Walter F, Jordakieva G, et al. Allergens and adjuvants in allergen immunotherapy for immune activation, tolerance, and resilience. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021; 9:1780–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhami S, Kakourou A, Asamoah F, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2017; 72:1825–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corren J, Larson D, Altman MC, et al. Effects of combination treatment with tezepelumab and allergen immunotherapy on nasal responses to allergen: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023; 151:192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corren J, Saini SS, Gagnon R, et al. Short-term subcutaneous allergy immunotherapy and dupilumab are well tolerated in allergic rhinitis: a randomized trial. J Asthma Allergy. 2021; 14:1045–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson HS, Oppenheimer J, Vatsia GA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of sublingual immunotherapy with standardized cat extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993; 92:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skoner D, Gentile D, Bush R, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy in patients with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis caused by ragweed pollen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125:660–666, 666e1–666.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bush RK, Swenson C, Fahlberg B, et al. House dust mite sublingual immunotherapy: results of a US trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 127:974–981.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creticos PS, Esch RE, Couroux P, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of standardized ragweed sublingual-liquid immunotherapy for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014; 133:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leatherman BD, Khalid A, Lee S, et al. Dosing of sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis: evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015; 5:773–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bordignon V, Burastero SE. Multiple daily administrations of low-dose sublingual immunotherapy in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006; 97:158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winders T, DuBuske L, Bukstein DA, et al. Shifts in allergy practice in a COVID-19 world: implications of pre-COVID-19 national health care provider and patient surveys of treatments for nasal allergies. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2021; 42:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnstone DE, Dutton A. The value of hyposensitization therapy for bronchial asthma in children–a 14-year study. Pediatrics. 1968; 42:793–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adkinson NF, Jr, Eggleston PA, Eney D, et al. A controlled trial of immunotherapy for asthma in allergic children. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336:324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowell FC, Franklin W. A double-blind study of the effectiveness and specificity of injection therapy in ragweed hay fever. N Engl J Med. 1965; 273:675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franklin W, Lowell FC. Comparison of two dosages of ragweed extract in the treatment of pollinosis. JAMA. 1967; 201:915–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaar O, Biedermann T, Klimek L, et al. Depigmented-polymerized mixed grass/birch pollen extract immunotherapy is effective in polysensitized patients. Allergy. 2013; 68:1306–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z-X, Shi H. Single-allergen sublingual immunotherapy versus multi-allergen subcutaneous immunotherapy for children with allergic rhinitis. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2017; 37:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim CK, Callaway Z, Park J-S, et al. Efficacy of subcutaneous immunotherapy for patients with asthma and allergic rhinitis in Korea: effect on eosinophilic inflammation. Asia Pac Allergy. 2021; 11:e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nevot-Falcó S, Mancebo EG, Martorell A, et al. Safety and effectiveness of a single multiallergen subcutaneous immunotherapy in polyallergic patients. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2021; 182:1226–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li L, Guan K. Effect on quality of life of the mixed house dust mite/weed pollen extract immunotherapy. Asia Pac Allergy. 2016; 6:168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhyou HI, Nam YH. Efficacy of allergen immunotherapy for allergic asthma in real world practice. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020; 12:99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calderon MA, Casale TB, Nelson HS, et al. Extrapolating evidence-based medicine of AIT into clinical practice in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023; 11:1100–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paoletti G, Di Bona D, Chu DK, et al. Allergen immunotherapy: the growing role of observational and randomized trial “Real-World Evidence.” Allergy. 2021; 76:2663–2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calderon MA, Cox L, Casale TB, et al. Multiple-allergen and single-allergen immunotherapy strategies in polysensitized patients: looking at the published evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 129:929–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson HS. To mix or not to mix in allergy immunotherapy vaccines. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021; 21:583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maloney J, Berman G, Gagnon R, et al. Sequential treatment initiation with timothy grass and ragweed sublingual immunotherapy tablets followed by simultaneous treatment is well tolerated. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016; 4:301–309.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amar SM, Harbeck RJ, Sills M, et al. Response to sublingual immunotherapy with grass pollen extract: monotherapy versus combination in a multiallergen extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 124:150–156.e1-e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ortiz AS, McMains KC, Laury AM. Single vs multiallergen sublingual immunotherapy in the polysensitized patient: a pilot study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018; 8:490–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts G, Pfaar O, Akdis CA, et al. EAACI Guidelines on Allergen Immunotherapy: allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Allergy. 2018; 73:765–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moote W, Kim H, Ellis AK. Allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018; 14(suppl 2):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dykewicz MS, Wallace DV, Amrol DJ, et al. Rhinitis 2020: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020; 146:721–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ellis AK, Cook V, Keith PK, et al. Focused allergic rhinitis practice parameter for Canada. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2024; 20:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Guyatt GH, Gómez-Escobar LG, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for atopic dermatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023; 151:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al. European guideline (EuroGuiDerm) on atopic eczema - part II: non-systemic treatments and treatment recommendations for special AE patient populations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022; 36:1904–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pajno GB, Fernandez-Rivas M, Arasi S, et al. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy. 2018; 73:799–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parashar S, Pandya A, Portnoy JM. Pediatric subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2022; 43:286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pitsios C, Demoly P, Bilò MB, et al. Clinical contraindications to allergen immunotherapy: an EAACI position paper. Allergy. 2015; 70:897–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dhami S, Nurmatov U, Arasi S, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Allergy. 2017; 72:1597–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caffarelli C, Cangemi J, Mastrorilli C, et al. Allergen-specific immunotherapy for inhalant allergens in children. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2020; 16:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sato S, Hata H, Kobayashi S, et al. Efficacy, safety and immunological response with SQ house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy-tablet by body weight in children. Arerugi. 2020; 69:918–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pollock J, Watson N, Pittman L, et al. Ultrafiltered dog allergen skin test compared with acetone precipitated and conventional dog: a retrospective study. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2024; 45:453–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greenhawt M, Oppenheimer J, Nelson M, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy: a focused allergen immunotherapy practice parameter update. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017; 118:276–282.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wise SK, Lin SY, Toskala E, et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: allergic rhinitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018; 8:108–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wise SK, Damask C, Roland LT, et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Allergic Rhinitis - 2023. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2023; 13:293–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang J, Lei S. Efficacy and safety of sublingual versus subcutaneous immunotherapy in children with allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2023; 14:1274241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuta A, Ogawa Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Comparison of clinical efficacy and safety between children and adults before and 1 year after mite sublingual immunotherapy for perennial allergic rhinitis. Arerugi. 2021; 70:186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim JY, Rhee C-S, Cho SH, et al. House dust mite sublingual immunotherapy in children versus adults with allergic rhinitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2021; 35:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaur A, Skoner D, Ibrahim J, et al. Effect of grass sublingual tablet immunotherapy is similar in children and adults: a Bayesian approach to design pediatric sublingual immunotherapy trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018; 141:1744–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tworek D, Bochenska-Marciniak M, Kuprys-Lipinska I, et al. Perennial is more effective than preseasonal subcutaneous immunotherapy in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013; 27:304–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sieber J, Koberlein J, Mosges R. Sublingual immunotherapy in daily medical practice: effectiveness of different treatment schedules - IPD meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010; 26:925–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Demoly P, Calderon MA, Casale TB, et al. “The value of pre- and co-seasonal sublingual immunotherapy in pollen-induced allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.” Clin Transl Allergy. 2015; 5:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rice JL, Diette GB, Suarez-Cuervo C, et al. Allergen-specific immunotherapy in the treatment of pediatric asthma: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2018; 141:e20173833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van de Griendt E-J, Tuut MK, de Groot H, et al. Applicability of evidence from previous systematic reviews on immunotherapy in current practice of childhood asthma treatment: a GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017; 7:e016326. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zheng C, Xu H, Huang S, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous immunotherapy in asthmatic children allergic to house dust mite: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2023; 11:1137478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Detels R, Gulliford M, Karim QA, et al. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dwivedi V, Kopanja S, Schmidthaler K, et al. Preventive allergen immunotherapy with inhalant allergens in children. Allergy. 2024; 79: 2065–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Möller C, Dreborg S, Ferdousi HA, et al. Pollen immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis (the PAT-study). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 109:251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niggemann B, Jacobsen L, Dreborg S, et al. Five-year follow-up on the PAT study: specific immunotherapy and long-term prevention of asthma in children. Allergy. 2006; 61:855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jacobsen L, Niggemann B, Dreborg S, et al. Specific immunotherapy has long-term preventive effect of seasonal and perennial asthma: 10-year follow-up on the PAT study. Allergy. 2007; 62:943–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zolkipli Z, Roberts G, Cornelius V, et al. Randomized controlled trial of primary prevention of atopy using house dust mite allergen oral immunotherapy in early childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015; 136:1541–1547.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alviani C, Roberts G, Mitchell F, et al. Primary prevention of asthma in high-risk children using HDM SLIT: assessment at age 6 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020; 145:1711–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Farraia M, Paciência I, Castro Mendes F, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of house dust mite allergen immunotherapy in children with allergic asthma. Allergy. 2022; 77:2688–2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Novembre E, Galli E, Landi F, et al. Coseasonal sublingual immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 114:851–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang C-S, Wang X-D, Zhang W, et al. Long-term efficacy of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus immunotherapy in patients with allergic rhinitis: a 3-year prospective study. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2012; 47:804–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kristiansen M, Dhami S, Netuveli G, et al. Allergen immunotherapy for the prevention of allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017; 28:18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Valovirta E, Petersen TH, Piotrowska T, et al. Results from the 5-year SQ grass sublingual immunotherapy tablet asthma prevention (GAP) trial in children with grass pollen allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018; 141:529–538.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marogna M, Tomassetti D, Bernasconi A, et al. Preventive effects of sublingual immunotherapy in childhood: an open randomized controlled study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008; 101:206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stelmach I, Sobocińska A, Majak P, et al. Comparison of the long-term efficacy of 3- and 5-year house dust mite allergen immunotherapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012; 109:274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schmitt J, Wustenberg E, Kuster D, et al. The moderating role of allergy immunotherapy in asthma progression: results of a population-based cohort study. Allergy. 2020; 75:596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Venkatesan P. GINA report for asthma. Lancet Respir Med. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Di Bona D, Plaia A, Leto-Barone MS, et al. Efficacy of allergen immunotherapy in reducing the likelihood of developing new allergen sensitizations: a systematic review. Allergy. 2017; 72:691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bousquet J, Melén E, Haahtela T, et al. Rhinitis associated with asthma is distinct from rhinitis alone: the ARIA-MeDALL hypothesis. Allergy. 2023; 78:1169–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Amaral R, Bousquet J, Pereira AM, et al. Disentangling the heterogeneity of allergic respiratory diseases by latent class analysis reveals novel phenotypes. Allergy. 2019; 74:698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Raciborski F, Bousquet J, Bousqet J, et al. Dissociating polysensitization and multimorbidity in children and adults from a Polish general population cohort. Clin Transl Allergy. 2019; 9:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Blöndal V, Sundbom F, Borres MP, et al. Study of atopic multimorbidity in subjects with rhinitis using multiplex allergen component analysis. Clin Transl Allergy. 2020; 10:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee J-H, Hong C, Oh JS, et al. Electronic medical record–based machine learning predicts the relapse of asthma exacerbation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023; 131:270–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cingi C, Gevaert P, Mösges R, et al. Multi-morbidities of allergic rhinitis in adults: European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Task Force Report. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017; 7:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Papadopoulos NG, Delgado L, Casale TB, et al. Impact of comorbid allergic rhinitis in patients with asthma: A Position Paper from the EAACI Task Force on Allergic Rhinitis Comorbidities. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017; 71:17. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guo B-C, Wu K-H, Chen C-Y, et al. Advancements in allergen immunotherapy for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25:1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ren L, Wang C, Xi L, et al. Long-term efficacy of HDM-SCIT in pediatric and adult patients with allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2023; 19:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Di Rienzo V, Marcucci F, Puccinelli P, et al. Long-lasting effect of sublingual immunotherapy in children with asthma due to house dust mite: a 10-year prospective study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003; 33:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Penagos M, Eifan AO, Durham SR, et al. Duration of allergen immunotherapy for long-term efficacy in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2018; 5:275–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Scadding GW, Calderon MA, Shamji MH, et al. Effect of 2 years of treatment with sublingual grass pollen immunotherapy on nasal response to allergen challenge at 3 years among patients with moderate to severe seasonal allergic rhinitis: the GRASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017; 317:615–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Renand A, Shamji MH, Harris KM, et al. Synchronous immune alterations mirror clinical response during allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018; 141:1750–1760.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Larenas-Linnemann DES, Gupta P, Mithani S, et al. Survey on immunotherapy practice patterns: dose, dose adjustments, and duration. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012; 108:373–378.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schmidlin KA, Bernstein DI. Safety of allergen immunotherapy in children. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023; 23:514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Epstein TG, Murphy-Berendts K, Liss GM, et al. Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal reactions to immunotherapy (2008–2018): postinjection monitoring and severe asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021; 127:64–69.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Epstein TG, Liss GM, Berendts KM, et al. AAAAI/ACAAI Subcutaneous Immunotherapy Surveillance Study (2013–2017): Fatalities, Infections, Delayed Reactions, and Use of Epinephrine Autoinjectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019; 7:1996–2003.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lim CE, Sison CP, Ponda P. Comparison of pediatric and adult systemic reactions to subcutaneous immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017; 5:1241–1247.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Almaci M, Treudler R, Breiding M, et al. Allergen immunotherapy-induced anaphylaxis: data from the European Anaphylaxis Registry. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2025; 134:724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nolte H, Calderon MA, Bernstein DI, et al. Anaphylaxis in clinical trials of sublingual immunotherapy tablets. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024; 12:85–95.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]