Abstract

Background: The increased utilization of oral factor Xa inhibitors (FXaI) has led to a growing interest in the clinical utility of FXaI-specific anti-Xa concentrations. Critically ill populations are at risk of bleeding secondary to FXaI accumulation in the setting of end-organ dysfunction. To mitigate this risk, an FXaI anti-Xa concentration-guided approach to transitioning between oral and parenteral anticoagulation has been explored. Objective: To compare the incidence of bleeding upon intensive care unit (ICU) admission between 2 different FXaI transition strategies: concentration versus non-concentration-guided. Methods: We performed a retrospective chart review of patients admitted between January 2019 and May 2022 with objective evidence of FXaI exposure within 48 hours preceding ICU admission. Patients were excluded if they were admitted to the ICU with a primary diagnosis related to a bleeding event, received a non-FXaI anticoagulant 48 hours preceding ICU admission, remained off anticoagulation during their ICU admission, or underwent surgical procedures. The primary outcome was the incidence of major bleeding within 5 days of ICU admission. Thromboembolic events were evaluated as a secondary endpoint. Results: A total of 433 patients (184 concentration-guided vs 249 non-concentration-guided) were included. There was no difference in major bleeding between groups (2.7% in concentration-guided vs 3.6% in non-concentration-guided; P = 0.79). Thromboembolic complications were similar between groups (1.6% in concentration-guided vs 2.0% in non-concentration-guided; P = 1.00) despite a longer time from last FXaI dose to anticoagulant transition in the concentration-guided group (29.9 hours vs 19.4 hours; P < 0.01). Conclusion and relevance: Use of FXaI concentrations to guide anticoagulation transition in the ICU had no impact on major bleeding events or thromboembolic complications. Further analyses are needed to validate FXaI concentration-guided strategies and solidify anti-Xa cutoffs to create a standardized approach to FXaI transitions in the critically ill patient population.

Keywords: DOAC, anti-Xa level, anticoagulation, transition, ICU

Background

The oral factor Xa inhibitors (FXaIs), rivaroxaban and apixaban, are commonly prescribed for the prevention and treatment of thrombosis. 1 Both agents undergo varying degrees of hepatic and/or renal clearance, and package insert transition recommendations do not account for these pharmacokinetic changes in dynamic, critically ill patients.1,2 For patients with end-organ dysfunction, traditional recommendations for oral-to-parenteral anticoagulant transitions may not allow for adequate FXaI drug clearance and can result in additive effects. As such, the clinical utility of anti-Xa concentrations calibrated with the FXaI drug of interest continues to gain widespread attention.3 -9 Prior literature suggests a higher rate of major bleeding in FXaI-treated patients who have a greater severity of illness, acute kidney injury (AKI), and/or higher median anti-Xa concentrations.10 -12 Although data remains limited in the critically ill, using anti-Xa concentrations to guide inpatient transitions from oral to parenteral anticoagulants could represent a risk-mitigating strategy.12,13 In the current study, we compared the incidence of major bleeding upon intensive care unit (ICU) admission between 2 different FXaI transition strategies: an anti-Xa concentration-guided versus a non-concentration-guided approach.

Methods

Study Design

This single-center, retrospective cohort study was conducted at Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas, between January 2019 and May 2022. Our institution is a non-trauma academic medical center with 1020 operating beds and 6 ICUs, comprising approximately 150 critical care beds. Institutional review board approval was obtained (PRO00035290). Patients were included if they were admitted to the ICU and had objective evidence of FXaI (apixaban or rivaroxaban) exposure within 48 hours preceding ICU admission defined as either a [1] detectable anti-Xa concentration confirming prior to admission FXaI use or an [2] electronic medical record-documented inpatient FXaI administration within 48 hours of ICU admission. Patients were excluded if they were admitted to the ICU with a primary diagnosis related to a bleeding event, received a non-FXaI anticoagulant 48 hours preceding ICU admission, remained off anticoagulation during their ICU admission, or underwent surgical procedures. Edoxaban was not included in this study given the minimal use at our institution. Patients were classified into 2 groups based on the anticoagulation transition strategy utilized. Patients were assigned to the concentration-guided cohort if an anti-Xa concentration was obtained on the day of ICU admission to assist with the anticoagulation transition. Decisions on transition strategy and timing were made by the multidisciplinary ICU team utilizing a patient-specific approach. The remainder of the patients constituted the non-concentration-guided cohort. FXaI chromogenic anti-Xa assay testing at our institution has been previously described.10 -12,14,15 The anti-Xa concentrations were determined using an STA-Liquid Anti-Xa Assay standardized with commercial calibrators. Results are routinely available within 3 hours of sample collection.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of major bleeding up to 5 days following ICU admission, until discharge, or death, whichever occurred first. Bleeding was defined using the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) criteria: fatal bleeding, bleeding in a critical site (intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome), or clinically overt bleeding resulting in a ≥2 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin or requiring ≥ 2 units of packed red blood cells within 24 hours. 16 The incidence of thromboembolic events, up to 10 days following ICU admission, was evaluated as a secondary endpoint. This timeframe was utilized to account for thromboembolic complications that may have been associated with a delay in the transition between anticoagulants.

Statistical Analysis

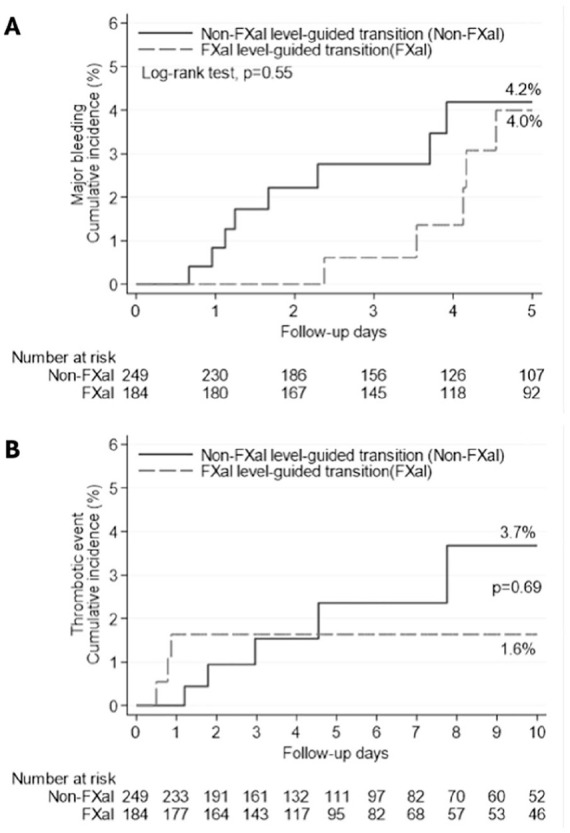

Patient characteristics were reported as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. Differences between groups were determined by χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum, as appropriate. Cumulative incidence of bleeding within 5 days and thrombotic events within 10 days were depicted using Kaplan-Meier curves. Difference in the incidence between groups was tested by the log-rank test. All the analyses were performed on Stata version 18.5 (StataCorp LLC). A 2-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Population

In total, 433 patients met the inclusion criteria with 184 patients versus 249 patients in the concentration-guided versus non-concentration-guided groups, respectively. Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. Both groups were balanced concerning sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores and coagulation parameters. The incidence of AKI was similar between groups (38.6% concentration-guided vs 30.5% non-concentration-guided; P = 0.08); however, patients in the concentration-guided cohort more often required continuous renal replacement therapy (13.6% vs 6.8%; P = 0.02). The prevalence of cirrhosis was similar between groups (11.5% concentration-guided vs 5.6% non-concentration-guided). Patients in the concentration-guided group were more likely to transition to parenteral anticoagulation upon ICU admission (81.5% vs 24.1%; P < 0.01) versus remaining on an FXaI drug (12.5% vs 65.9%; P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| FXaI concentration-guided transition (n = 184) | Non-FXaI concentration-guided transition (n = 249) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 72.5 (63.8-78.0) | 72.0 (63.0-79.0) | 0.87 |

| Gender | 99 (53.8) | 144 (57.8) | 0.40 |

| Weight, kg | 81.7 (64.3-103.3) | 82.5 (68.0-99.8) | 0.49 |

| SOFA score | 4.0 (2.0-7.0) | 5.0 (2.0-7.0) | 0.53 |

| Acute kidney injury a | 71 (38.6) | 76 (30.5) | 0.08 |

| Renal replacement therapy | |||

| None | 143 (77.7) | 196 (78.7) | 0.80 |

| Hemodialysis | 16 (8.7) | 35 (14.1) | 0.09 |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | 25 (13.6) | 17 (6.8) | 0.02 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.39 |

| History of cirrhosis | 17 (11.5) | 14 (5.6) | 0.15 |

| Laboratory values at ICU admission | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 10.0 (8.7-11.8) | 9.8 (8.4-11.7) | 0.31 |

| Platelets, k/μL | 205.0 (148.0-266.5) | 213.0 (153.0-274.0) | 0.42 |

| INR | 1.6 (1.4-2.1) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) | 0.13 |

| Partial thromboplastin time, s | 39.2 (22.5-47.2) | 38.5 (31.5-44.9) | 0.08 |

| AST, U/L | 36.0 (24.0-73.0) | 29.0 (21.0-52.0) | 0.01 |

| ALT, U/L | 28.0 (16.0-53.0) | 22.0 (14.0-44.0) | 0.04 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 0.6 (0.4-1.0) | 0.27 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.4 (1.0-2.4) | 1.2 (0.8-2.0) | 0.02 |

| Initial FXaI concentration, ng/mL | 128.5 (78.0-215.0) | — | — |

| ICU length of stay, d | 5.3 (3.3-10.0) | 4.5 (2.2-9.1) | 0.02 |

| Concomitant antiplatelet therapy | |||

| None | 88 (47.8) | 155 (62.2) | <0.01 |

| Single antiplatelet therapy | 81 (44.0) | 89 (35.7) | 0.10 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 15 (8.2) | 5 (2.0) | <0.01 |

| Indication for anticoagulation | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 132 (71.7) | 153 (61.4) | 0.03 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 44 (23.9) | 88 (35.3) | 0.01 |

| Other | 8 (4.3) | 8 (3.2) | 0.54 |

| FXaI administered | |||

| Apixaban | 156 (84.8) | 212 (85.1) | 0.92 |

| Rivaroxaban | 28 (15.2) | 37 (14.9) | 0.92 |

| Anticoagulant transition strategy | |||

| Prophylaxis | 11 (6.0) | 25 (10.0) | 0.13 |

| Parenteral | 150 (81.5) | 60 (24.1) | <0.01 |

| Direct oral anticoagulant | 23 (12.5) | 164 (65.9) | <0.01 |

| Median duration of anticoagulation, h | |||

| Prophylaxis | 24.9 (12.8-42.8) | 22.5 (13.0-39.2) | 0.85 |

| Therapeutic | 67.4 (28.5-102.4) | 62.7 (27.5-98.1) | 0.58 |

| Median time from last FXaI dose to transition, h | 29.9 (17.9-50.2) | 19.4 (12.0-30.8) | <0.01 |

| Median FXaI concentration drawn prior to anticoagulation transition, ng/mL b | 99.5 (68.0-137.5) | — | — |

All values are presented as median (IQR) for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables, unless otherwise specified. FXaI, factor Xa inhibitor; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; kg, kilograms; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

AKI was defined using the Acute Kidney Injury Networks (AKIN) criteria. 17

Reference ranges for rivaroxaban and apixaban are 20 to 472 ng/mL and 20 to 452 ng/mL, respectively.

Major Bleeding and Thrombotic Complications

Clinical outcomes are presented in Table 2 and Kaplan-Meier curves are presented in Figure 1. There was no difference in the primary outcome of major bleeding in the concentration-guided versus non-concentration-guided groups (2.7% vs 3.6%; P = 0.79). Clinically overt bleeding associated with an acute hemoglobin drop (≥2 g/dL) accounted for 78.6% of all bleeding events, of which the majority (64.3%) occurred in patients transitioned to parenteral anticoagulation. In the concentration-guided group, 80% of major bleeding events were associated with anti-Xa concentrations above 100 ng/mL. There was no difference between groups for thromboembolic events (1.6% vs 2.0%, P = 1.00). Deep vein thrombosis was the most common thromboembolic event. All thrombotic events occurred in patients with ICU admission anti-Xa concentrations less than 100 ng/dL.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes.

| FXaI concentration-guided transition (n = 184) |

Non-FXaI concentration-guided transition (n = 249) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major bleeding, No. (%) | 5 (2.7) | 9 (3.6) | 0.79 |

| Category of major bleeding | |||

| Acute drop in hemoglobin | 4 (80.0) | 7 (77.8) | 1.00 |

| Upper extremity hematoma | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1.00 |

| GI bleeding | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.36 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1.00 |

| Major bleeding by individual anticoagulant transition strategy | |||

| Prophylaxis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 1.00 |

| Parenteral | 5 (100.0) | 4 (44.5) | 0.28 |

| Direct oral anticoagulant | 0 (0.0) | 3 (33.3) | 1.00 |

| Major bleeding by initial FXaI administered | |||

| Apixaban | 4 (80.0) | 8 (88.9) | 0.65 |

| Rivaroxaban | 1 (20.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0.65 |

| Median time from last FXaI dose to major bleed, h | 111.5 (96.8-119.6) | 43.5 (32.9-66.5) | 0.01 |

| Median time from anticoagulation transition initiation to major bleed, h | 70.2 (65.3-79.2) | 7.3 (4.0-15.1) | 0.01 |

| Major bleed according to final FXaI concentration a | |||

| <100 ng/mL | 1 (1.1) | — | — |

| 100-200 ng/mL | 3 (3.8) | — | — |

| 200-300 ng/mL | 1 (9.1) | — | — |

| >300 ng/mL | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| Thrombotic event, No. (%) | 3 (1.6) | 5 (2.0) | 1.00 |

| Category of thrombotic event | |||

| Deep Vein Thrombosis | 1 (33.3) | 5 (100.0) | 0.11 |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.11 |

| Thrombotic event by individual anticoagulant transition strategy | |||

| Prophylaxis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1.00 |

| Parenteral | 3 (100.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0.09 |

| Direct oral anticoagulant | 0 (0.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1.00 |

| Thrombotic event by initial FXaI administered | |||

| Apixaban | 2 (66.7) | 3 (60.0) | 0.85 |

| Rivaroxaban | 1 (33.3) | 2 (40.0) | 0.85 |

| Median time from last FXaI dose to thrombotic event, h | 16.4 (3.8-29.1) | 6.3 (3.0-7.8) | 0.70 |

| Median time from anticoagulation transition initiation to thrombotic event, h | −3.9 (-24.1-3.9) | 50.4 (24.0-62.8) | 0.10 |

| Thrombosis according to final FXaI concentration a | |||

| <100 ng/mL | 3 (3.3) | — | — |

| 100-200 ng/mL | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| 200-300 ng/mL | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

| >300 ng/mL | 0 (0.0) | — | — |

All values are presented as median (IQR) for continuous variables and No. (%) for categorical variables, unless otherwise specified. FXaI, factor Xa inhibitor; IQR, interquartile range.

Reference ranges for rivaroxaban and apixaban are 20 to 472 ng/mL and 20 to 452 ng/mL, respectively.

Figure 1.

(A) Time-to-event analysis for major bleeding within 5 days of ICU admission analysis. (B) Time-to-event analysis for thrombotic events within 10 days of ICU admission.

Discussion

Despite the widespread benefits of oral FXaIs drugs, bleeding remains a major concern and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, health resource utilization, and costs.18,19 Given the pharmacokinetic alterations secondary to renal and hepatic dysfunction, bleeding risk with FXaI drugs is especially concerning in critically ill patients whose heterogeneity was not reflected in the pivotal FXaI trials which were exclusively conducted in the outpatient setting.20,21 Currently, there is no standardized approach for the management of these agents in patients with AKI. Studies have demonstrated a gradual increase in FXaI drug concentrations as renal function deteriorates leading to drug accumulation which subsequently heightens bleed risk.11,22 -25 In addition, with FXaI drugs varying degrees of hepatic metabolism, bleeding rates for patients with moderate-to-severe cirrhosis on oral FXaI drugs can be as high as 36%. 26 As such, guidelines recommend avoiding the use of FXaI drugs in cases of AKI or Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis. 27 Therefore, assessment of FXaI accumulation in the critically ill needs to be considered as traditional transition recommendations are based on kinetic data from health volunteers and do not account for FXaI drug accumulation.23,24

In our study, there was no difference in major bleeding events between groups (2.7% in concentration-guided vs 3.6% in non-concentration-guided; P = 0.79). Despite a longer anticoagulant transition time from last FXaI drug dose in the concentration-guided group (29.9 hours vs 19.4 hours; P < 0.01), thromboembolic complications were similar between groups (1.6% in concentration-guided vs 2.0% in non-concentration-guided; P = 1.00). Coagulation studies, including FXaI anti-Xa concentrations, can provide valuable information on the degree of anticoagulation to help stratify bleed risk when transitioning between anticoagulants.3 -6,10 The use of chromogenic FXaI anti-Xa concentrations represents a novel approach to oral FXaI transitions and a potential risk-mitigating strategy for major bleeding.3 -6,10 -12,15 Recent data has demonstrated a significant reduction in major bleeding when an FXaI anti-Xa concentration was integrated in guiding transitions from oral to parenteral anticoagulation.12,13 At our institution, managing anticoagulant transitions with anti-Xa concentrations is tailored rather than protocol-driven. Each patient receives a thorough evaluation to identify risk factors for oral FXaI drug accumulation (such as acute renal and/or hepatic dysfunction), with anti-Xa levels serving as a valuable tool to guide clinical decisions. Our ICUs leverage a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach involving intensivists, critical care clinical pharmacists, and other specialists, to develop personalized anticoagulation transition plans for every patient. The threshold anti-Xa concentration prompting a transition varies based on individual risk factors for bleeding and thrombosis. Typically, anti-Xa concentrations are ordered upon ICU admission if there is suspicion of oral FXaI drug accumulation. Elevated levels prompt repeat testing within 12 to 24 hours and continued monitoring until the multidisciplinary team determines it safe to initiate anticoagulation therapy. Current data suggests an anti-Xa concentration below 100 ng/mL is generally considered safe for FXaI transition, while values between 100 to 200 ng/mL require further clinical evaluation.12,13 Levels exceeding 200 ng/mL may warrant temporarily withholding parenteral anticoagulation 12 ; however, reversal agents or blood products are not routinely administered solely based on these concentrations. Our study findings are consistent with these anti-Xa concentration thresholds as a majority of bleeding events occurred at concentrations above 100 ng/mL.11,12

This study has several limitations. First, the practice of ordering FXaI anti-Xa concentrations and acting upon the results is not standardized within our institution, and we acknowledge that this may introduce bias in patient selection, anticoagulation management, and the clinical interpretation of anti-Xa concentrations. Second, we were unable to control for certain risk factors associated with bleeding, such as comorbid conditions (chronic kidney disease, continuous renal replacement therapy, cirrhosis, malignancy, prior history of bleeding) given potentially unreliable chart documentation of patient past medical histories. Published studies from our institution demonstrated low utilization of additional agents known to interact with oral FXaIs; therefore, we did not capture major drug-drug interactions between known inhibitors and inducers of oral FXaI metabolism. 12 Third, thromboembolic risk factors were not accounted for and should be further investigated in future studies. Lastly, the oral FXaI drug dose appropriateness was not categorized given the nature of the patient population and their rapidly changing clinical status. However, in day-to-day practices, each of these factors not captured should influence the clinical assessment to ensure safe and effective anticoagulation strategies.

Conclusion and Relevance

In this study, the use of FXaI drug concentrations to guide anticoagulation transition in the ICU setting demonstrated no significant difference in major bleeding events or thromboembolic complications. Further analyses are needed to validate FXaI drug concentration-guided transition strategies and solidify anti-Xa cutoffs to create a standardized approach to FXaI anticoagulation management into critically ill patient populations.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Mariah I. Sigala  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7196-3259

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7196-3259

Duc T. Nguyen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5059-4404

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5059-4404

References

- 1. Chen A, Stecker E, Warden BA. Direct oral anticoagulant use: a practical guide to common clinical challenges. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(13):e017559. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rali P, Gangemi A, Moores A, Mohrien K, Moores L. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants in critically ill patients. Chest. 2019;156(3):604-618. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gosselin RC, Adcock DM, Bates SM, et al. International Council for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH) recommendations for laboratory measurement of direct oral anticoagulants. Thromb Haemost. 2018;118(3):437-450. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1627480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Testa S, Legnani C, Antonucci E, et al. Drug levels and bleeding complications in atrial fibrillation patients treated with direct oral anticoagulants. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(7):1064-1072. doi: 10.1111/jth.14457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright C, Brown R, Cuker A. Laboratory measurement of the direct oral anticoagulants: indications and impact on management in clinical practice. Int J Lab Hematol. 2017;39(suppl 1):31-36. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rottenstreich A, Zacks N, Kleinstern G, et al. Direct-acting oral anticoagulant drug level monitoring in clinical patient management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;45(4):543-549. doi: 10.1007/s11239-018-1643-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Samuelson BT, Cuker A, Siegal DM, Crowther M, Garcia DA. Laboratory assessment of the anticoagulant activity of direct oral anticoagulants: a systematic review. Chest. 2017;151(1):127-138. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Association between edoxaban dose, concentration, anti-Factor Xa activity, and outcomes: an analysis of data from the randomised, double-blind ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2288-2295. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61943-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Samuelson BT, Cuker A. Measurement and reversal of the direct oral anticoagulants. Blood Rev. 2017;31(1):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2016.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lopez CN, Succar L, Varnado S, Donahue KR. Direct oral to parenteral anticoagulants: strategies for inpatient transition. J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;61(1):32-40. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Towers W, Nguyen SN, Ruegger MC, Salazar E, Donahue KR. Apixaban and rivaroxaban anti-Xa level monitoring versus standard monitoring in hospitalized patients with acute kidney injury. Ann Pharmacother. 2022;56(6):656-663. doi: 10.1177/10600280211046087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dinunno CV, Lopez CN, Succar L, et al. Direct oral to parenteral anticoagulant transitions: role of factor Xa inhibitor-specific anti-Xa concentrations. Pharmacotherapy. 2022;42(10):768-779. doi: 10.1002/phar.2726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dingus SJ, Smith AR, Dager WE, Zochert S, Nothdurft SA, Gulseth MP. Comparison of managing factor Xa inhibitor to unfractionated heparin transitions by aPTT versus a treatment guideline utilizing heparin anti-Xa levels. Ann Pharmacother. 2022;56(12):1289-1298. doi: 10.1177/10600280221090211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jakowenko N, Nguyen S, Ruegger M, Dinh A, Salazar E, Donahue KR. Apixaban and rivaroxaban anti-Xa level utilization and associated bleeding events within an academic health system. Thromb Res. 2020;196:276-282. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nguyen SN, Ruegger MC, Salazar E, Dreucean D, Tatara AW, Donahue KR. Evaluation of anti-xa apixaban and rivaroxaban levels with respect to known doses in relation to major bleeding events. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35:836-845. doi: 10.1177/08971900211009075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fernando SM, Mok G, Castellucci LA, et al. Impact of anticoagulation on mortality and resource utilization among critically ill patients with major bleeding. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(4):515-524. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Connolly SJ. Anticoagulant-related bleeding and mortality. J AM Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(23):2522-2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883-891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, et al. Apixa-ban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981-992. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1107039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jackevicius CA, Lu L, Ghaznavi Z, Warner AL. Bleeding risk of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(2):e007230. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eliquis (apixaban) [package insert]. Princeton, N.J.: Bristol–Myers Squibb; 2012. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/202155s000lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24. Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc. Xarelto® (rivaroxaban) Prescribing Information. 2014. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215859s000lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wahab A, Patnaik R, Gurjar M. Use of direct oral anticoagulants in ICU patients. Part I—applied pharmacology. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2021;53(5):429-439. doi: 10.5114/ait.2021.110607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oldham M, Palkimas S, Hedrick A. Safety and efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with moderate to severe cirrhosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2022;56(7):782-790. doi: 10.1177/10600280211047433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, et al. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-Vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(16):1330-1393. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]