Abstract

Aziridines, structurally related to epoxides, are among the most challenging and fascinating heterocycles in organic chemistry due to their increasing applications in asymmetric synthesis, medicinal chemistry, and materials science. These three-membered nitrogen-containing rings serve as key intermediates in the synthesis of chiral amines, complex molecules, and pharmaceutically relevant compounds. This review provides an overview of recent progress in catalytic asymmetric aziridination, focusing on novel methodologies, an analysis of the scope and limitations of each approach, and mechanistic insights.

Keywords: Aza-Darzens, 2H-azirines, Chiral aziridines, Enantioselective aziridination, Kinetic resolution

Introduction

Aziridines are a class of three-membered saturated nitrogen-containing heterocycles that, like other strained systems such as epoxides and cyclopropanes, exhibit significant ring strain due to their small bond angles (~ 60°) [1]. This inherent strain, combined with the electronegativity of the nitrogen atom, renders aziridines highly reactive toward regio- and stereoselective ring-opening reactions under mild conditions [2–5]. Such reactivity facilitates the generation of nitrogen-containing compounds, which are particularly valuable for the synthesis of amines with diverse stereochemical and structural properties. Additionally, they benefit asymmetric synthesis by employing chiral aziridines as versatile chiral substrates, auxiliaries, and reagents, thereby enhancing the available methods for producing chiral amines with high stereoselectivity [6, 7]. As a result, aziridines have become valuable intermediates in synthetic chemistry, enabling the introduction of diverse functional groups and the construction of more complex molecular architectures.

Despite being structurally related to epoxides, aziridines are considerably less explored, and methods for their synthesis and functionalization have developed at a slower pace. However, the past few decades have witnessed significant advances in aziridine chemistry [8–12], leading to their increased application in asymmetric synthesis, medicinal chemistry, and materials science. These compounds serve as key intermediates in the synthesis of chiral amines, and the development of pharmaceutically relevant compounds [13, 14]. Furthermore, their intrinsic reactivity makes the isolation of aziridine-containing natural products particularly challenging. These compounds are found in a wide range of biologically active agents, natural products, and related molecules. The antitumor and antibiotic properties of some of these compounds, including azinomycin B [15, 16], mitomycin C [17, 18], maduropeptin [19], and FR-900482 [20–22], a close relative of mitomycin C due to their structural similarity, are well known (Fig. 1). N,N′,N″-Triethylenethiophosphoramide (thiotepa) is a trifunctional alkylating agent that it has regained interest as one of the most effective anticancer drugs in high-dose treatment regimens [23]. The therapeutic applications of others are more diverse [24]. For instance, ficellomycin [25, 26] exhibits high in vivo activity against Gram-positive bacteria, as well as, multidrug resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. In contrast, azicemicin A [27, 28] demonstrates inhibitory activity against Gram-negative bacteria and mycobacteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Representative examples of aziridine-bearing covalent drugs. Aziridine ring is highlighted

The aziridine ring present in these chemotherapeutics appears to induce DNA monoalkylation via acid-activation, leading to the formation of a protonated aziridine that undergoes ring opening, thereby relieving the strain associated with the three-membered ring [29, 30]. Therefore, aziridines are potent alkylating agents that can function as covalent drugs due to their ability to act as DNA cross-linking agents via nucleophilic ring opening of the three-membered heterocycle [31].

Conversely, the ease of aziridine chemical transformations has gained significant attention for the generation of compound libraries, particularly for their role in ring-expansion reactions, which serve as a crucial step in the total synthesis of active drugs. For instance, Michida et al. [32] reported a well-designed illustration describing the asymmetric synthesis of the renin inhibitor DS-8108b, where an aziridine ring-opening reaction served as the key step. DS-8108b has entered human clinical trials as a landmark drug, demonstrating superior activity, efficiency, and safety compared to previous antihypertensive agents (Fig. 2). Lacosamide (Vimpat®) [33], an antiepileptic drug; MK-3281 [34], an inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase; sumanirole [35], a highly selective dopamine D2 receptor agonist developed for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease; oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) [36], a top-selling drug used for the treatment and prevention of the seasonal influenza caused by mutant viral strains; and BIRT-377 [37], a potent negative allosteric modulator of LFA-1 (lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1) used for the treatment of inflammatory and immune disorders, are representative examples in which the regio- and stereoselective aziridine ring-opening reaction was used as the key step in their synthesis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Selected pharmaceutical and bioactive compounds resulting from transformations of aziridines. The ethylamine structural unit derived from the aziridine moiety is highlighted

With ongoing advancements in synthetic methodologies, aziridines continue to expand their role as indispensable tools in modern organic chemistry. In recent decades, several methodologies have emerged or been improved and are now available for the highly diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of aziridines. In this context, it might be observed that several reviews concerning the stereoselective synthesis of aziridines have appeared previously [7, 38–43]. Moreover, during the preparation of this review, a new publication on the synthesis of chiral aziridines was released [44].

This review highlights recent progress in the field of catalytic asymmetric aziridination, focusing on novel methodologies, analysis of the scope and limitations of each approach, and mechanistic insights. It is divided into four sections, covering asymmetric nucleophilic addition to 2H-azirines, aziridination of imines, aziridination of alkenes, and the kinetic resolution and desymmetrization of aziridines and 2H-azirines. The discussion will focus on those advances published in the last 7 years. This area was previously reviewed in 2018 [40], covering the literature until the end of 2017.

Catalytic Asymmetric Nucleophilic Addition to 2H-Azirines

Nucleophilic addition to 2H-azirines yields aziridine derivatives [45–51], and its asymmetric variant offers a promising approach to synthesizing chiral aziridines. The stereochemical outcome of these nucleophilic additions can be effectively controlled using chiral auxiliaries or, more efficiently, chiral catalysts. Nevertheless, enantioselective reactions of 2H-azirines with nucleophiles are uncommon.

Organocatalysis

The Nakamura group [52] reported in 2018 the first organocatalyzed enantioselective reaction of 2H-azirines with thiols as sulfur nucleophiles using N-heteroarenesulfonylated chinchona alkaloid amide catalysts (Scheme 1). The corresponding 2H-azirine 2, which was generated in situ by heating α-azidoacrylate 1 in dichloromethane at 150 °C in a sealed tube, reacted with different thiols in the presence of several cinchone-derived alkaloid catalyst. The best results were attained using 1 mol% loading of N-heteroarenesulfonylated chinchona alkaloid amide catalysts 3 and 4 affording aziridines 5 in good yields with high enantioselectivity (80–97% yield, 72–96% ee).

Scheme 1.

Organocatalytic enantioselective reaction of 2H-azirines with sulfur nucleophiles promoted by cinchona alkaloid sulfonamide catalysts

The reaction of azirine 2 with thiols, which contain electron-withdrawing groups such as bromo-, chloro-, fluorine-, and trifluoromethyl at the ortho-, meta-, or para-positions of the phenyl ring, resulted in the corresponding products 5 in good yields with high enantioselectivity (80–96% yield, 90–96% ee). Similarly, the reaction with benzenethiol or even electron-rich thiols, bearing methyl or methoxy groups, also produced products 5 with good enantioselectivity (90–93% ee). Several bulky thiols, including 2-naphthalenethiol and benzothiazolethiol, also proved to be effective nucleophiles in this transformation (Scheme 1). The selective use of catalysts 3 or 4 enabled the synthesis of enantiomer R or S, respectively.

The postulated transition state for the reaction of azirine 2 with thiols using catalyst 4 (as depicted in Scheme 2), occurs within the coordination sphere of the chiral catalyst 4. Consequently, the thiol approaches the Si face of the 2H-azirine to minimize steric hindrance, leading to the formation of the S-isomer of the final product.

Scheme 2.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the enantioselective reaction of 2H-azirines with thiols in the presence of cinchona alkaloid sulfonamide catalysts

Likewise, the authors suggested a catalytic cycle for the enantioselective addition of thiols to 2H-azirines. The acidic proton of catalyst 4 likely activates azirine 2 through hydrogen bonding to form intermediate I, while the quinuclidine moiety of catalyst 4 may simultaneously activate the thiol via hydrogen bonding. Subsequently, the activated thiol reacts with the azirine in intermediate II to form an adduct, which then undergoes protonation and decomplexation, producing aziridine 5 and regenerating catalyst 4. This reaction mechanism was further corroborated by ESI–MS analysis of the reaction mixture, which detected a signal corresponding to intermediate I (Scheme 2).

Despite the work of Nakamura et al. and a few other successful examples of asymmetric heteronucleophilic addition to 2H-azirines [53, 54] previously reported in the literature, asymmetric carbon nucleophilic addition remains uncommon due to significant steric hindrance or low nucleophilicity. In this context, the same group [55] reported the use of 8-quinolinesulfonylated 9-amino-9-deoxy-epi-cinchonine catalyst 4 (see Scheme 1) for the catalytic enantioselective reaction of 2H-azirines with oxazolones as carbon nucleophiles (Scheme 3). The in situ prepared azirine 2 reacted with various oxazolones 6 bearing electron-withdrawing or electron-rich groups or even oxazolones 6 with bulky naphthyl group organocatalyzed by cinchona alkaloid sulfonamide catalyst 4, yielding exclusively the C–2 addition products 7 as single regio- and diastereoisomers (dr > 95:5) in good to excellent yields (61–99% yield) and up to 98% ee (Scheme 3). However, the use of oxazolone 6 with an alkyl substituent (R1 = Bn) mediated by 4, afforded aziridine 7 in moderate yield and ee value (61% yield, 72% ee). This enantioselective approach enables the synthesis of aziridines 7 featuring vicinal tetrasubstituted stereocenters.

Scheme 3.

Enantioselective addition of oxazolones to 2H-azirines organocatalyzed by cinchona alkaloid sulfonamide catalyst

A similar catalytic mechanism, previously proposed for the addition of thiols to 2H-azirines (see Scheme 2), was reported for the reaction of azirines 2 with oxazolones 6, as shown in Scheme 4. The sulfonamide moiety in 4 forms intramolecular hydrogen bonds and interacts with the 2H-azirine 2, leading to the formation of intermediate III, activating the electrophilicity of the 2H-azirine through hydrogen-bonding. Simultaneously, since catalyst 4 function as a dual-activating organocatalyst, the quinuclidine moiety in 4 generates an enol of oxazolone 6. Next, the reaction of activated oxazolone 6 and 2H-azirine 2 in intermediate IV afford the corresponding adduct, which after protonation and decomplexation delivered aziridines 7 and catalyst 4 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Postulated mechanism for the reaction of 2H-azirines with oxazolones promoted by cinchona alkaloid sulfonamide catalyst

Using ring-strained 2H-azirines as substrates, Peng et al. [56] explored the potential of N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC) as catalysts in the aza-benzoin reaction with aldehydes to build chiral aziridines. Thus, the aza-benzoin reaction of 2H-azirines 2 with aldehydes 8 catalyzed by l-phenylalanine-derived triazolium catalyst 9, in combination with Cs2CO3, provides the desired aziridines 10 in 57–97% yield with 70–98% ee (Scheme 5). Aromatic aldehydes bearing an electron-withdrawing group, electron-rich aldehydes, or aldehydes with halides (e.g. F, Cl, and Br) in ortho-, meta-, or para-position of the phenyl ring were well-tolerated and provided aziridines 10 in good yields with excellent ee values. Likewise, a number of heteroaromatic aldehydes successfully afforded the desired products 10 in good conversions and with excellent enantioselectivity. However, no conversion was observed when an aliphatic aldehyde such as butyraldehyde participate in the enantioselective aza-benzoin reaction, which is in accordance with the low reactivity of other aliphatic aldehydes in NHC-catalyzed aza-benzoin reactions.

Scheme 5.

Organocatalyzed asymmetric aza-benzoin reaction of aldehydes with 2H-azirines mediated by N-heterocyclic carbenes

Concerning the 2H-azirine scope, the steric and electronic influences on the aromatic ring of azirines 2 were assessed by systematically varying the substitution patterns (Scheme 5). Azirines containing either electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups in ortho-, meta-, or para-position of the phenyl ring, or substrates having either a heteroaryl group or a naphthyl motif, yielded the chiral aziridine derivatives 10 in good to high yields and high enantioselectivity. Replacing the aromatic ring in the azirine 2 with a benzyl group still resulted in a high ee value. However, when the azirine featured an alkyl substituent, the reaction exhibited relatively low activity but maintained high enantioselectivity.

Metal Catalysis

To date, the construction of chiral aziridines with vicinal tetrasubstituted stereocenters remains a significant challenge. Importantly, vicinal tetrasubstituted stereocenters are key structural motifs in pharmaceutically active compounds, making the development of new catalytic methods for their construction a highly sought-after goal in organic chemistry. In addition, enolates rank among the most important and versatile carbon nucleophiles for enantioselective carbon–carbon bond formation [57–59]. Consequently, the direct enantioselective Mannich reaction of enolates with 2H-azirines serve as an atom-economic strategy for the preparation of chiral aziridines. In this context, Hu et al. [60] reported in 2018 the first asymmetric Cu-catalyzed tertiary carbon nucleophilic addition of β-keto amides 12 to 2H-azirines 11 mediated by a chiral N,N′-dioxide ligand L1/Cu(II) complex catalytic system for the preparation of chiral aziridines 13 with vicinal tetrasubstituted stereocenters (Scheme 6). L-Ramipril-derived ligand L-RaPr3 L1 was selected for the investigation of the substrate scope. First, inden-1-one-derived β-keto amides with different substitution (electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups at C–4, C–5, C–6, or C–7 positions), β-keto amide incorporating a naphthyl group, β-keto amides derived from cyclopentanone or cyclohexanone, or even β-keto ester 12 are well-tolerated and participated in the reaction to afford the corresponding chiral aziridines 13 in 65–90% yields, moderate to high diastereoselectivity (45:55 to 95:5 dr), with moderate to excellent enantioselectivity (32–94% ee). Next, nucleophilic addition of 5-phenyl-substituted β-keto amide 12 (R2 = 5-Ph) to several 2H-azirines 11 was examined (Scheme 6). It seems that the electronic properties of the substituents at the 3- or 4-position of the phenyl ring (R) in azirine 11 had a negligible effect on both the yields and enantioselectivity. The preparation of disubstituted 2H-aziridine 13 (R = 3, 5-Me2C6H3) was also achieved in 80% chemical yield with 83% ee value. Fused rings and naphthyl substituents in R are also tolerated in the Cu-catalyzed nucleophilic addition of β-keto amides 12 to 2H-azirines 11. The effect of the substituent R1 in 2H-azirines 11 was also investigated, revealing that the electronic properties had minimal influence on the reaction, affording aziridines with excellent enantioselectivity (up to 92% ee) and good yields (up to 85%). Conversely, the use of 2H-azirines 11 (R1 = Bn, H) gave the poorest results, providing aziridines 13 with limited stereocontrol.

Scheme 6.

Copper-catalyzed asymmetric addition of tertiary carbon nucleophiles to 2H-azirines

The assumed transition state for the nucleophilic addition of β-keto amides 12 to 2H-azirines 11 using chiral N,N′-dioxide ligand L1/Cu (II) complex catalytic system is reported in Scheme 6. The enolate of β-keto amide 12 coordinated to Cu (II) in a bidentate manner via the oxygen atoms of the dicarbonyl groups, resulting in the formation of a rigid octahedral complex (TS–1). In all instances, β-keto amide 12 selectively attacks 2H-azirine 11 from the backside relative to the substituent at the 2-position of the 2H-azirine, due to reduced steric hindrance, giving to the formation of (1S,2S,3S)-aziridine 13.

As expected, the addition of the enolizable 1,3-dicarbonyl compound to the 2H-azirine produces an aziridine nitrogen anion intermediate. The direct deprotonation of the enolizable 1,3-dicarbonyl compound in the absence of a catalyst may be assisted by the strong basicity of the aziridine nitrogen anion in the product, severely compromising the stereoselectivity of the products. In order to mitigate the impact of the strong basicity of the aziridine nitrogen anion, Feng et al. used the additional free acidic amide N–H bond of the nucleophile. Less acidic nucleophiles, such as prochiral nonstabilized ketone enolates, might be more favorable, with the enantiodetermining step being the attack of the enolate on the imine. Treating ProPhenol with Et2Zn can produce dinuclear main group metal salts, which have been shown to be effective metal catalysts for the addition of nonstabilized enolates to activated imines. In this regard, Trost et al. [61–65] described the Zn-ProPhenol catalyzed enantioselective Mannich reactions of nonstabilized enolates with acyclic imines activated with electron-withdrawing groups. The same group has applied this concept to the Zn-ProPhenol catalyzed enantioselective Mannich reaction of 2H-azirines with alkynyl ketones [66], providing chiral aziridines with vicinal tetrasubstituted stereocenters in high yields with excellent enantioselectivity (Scheme 7). Thus, reaction of substituted alkynyl ketones 14 as nucleophiles with 2H-azirines 2 in the presence of Zn-ProPhenol catalyst L2 in tetrahydrofuran (THF) as solvent, afforded aziridine intermediates 15, which were converted into aziridines 16 after sequential quantitative N–H bond acetylation. Concerning the scope of alkynyl ketones 14 that can participate in this reaction, it seems that electron-neutral naphthalene and phenanthrene-substituted alkynyl ketones proved to be excellent substrates for this Zn-ProPhenol catalytic system. Alkynyl ketones with electron-withdrawing groups at the para-, meta-, and ortho-positions of the phenyl ring gave the desired aziridines 16 in high yield with high to excellent enantioselectivity. Likewise, alkynyl ketones with electron-donating methyl group at the phenyl ring, heteroaromatic groups or even alkylsilyl groups are well tolerated in the catalytic enantioselective Mannich reaction. It is worth mentioning that cyclobutyl, cyclopentyl, cyclopent-3-en-1-yl, and cycloheptyl substituents in alkynyl ketones 14 delivered adducts 16 in reasonable yield with up to 95% ee (Scheme 7). In relation to the scope of 2H-azirines 2, electron-withdrawing groups at different positions of the phenyl ring or electron-neutral 2-naphthyl and (1,1′-biphenyl)-4-yl substituted 2H-azirines 2, performed well providing the desired products 16 in high yields with high to excellent enantioselectivity (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

Zn-ProPhenol catalyzed asymmetric Mannich reaction of 2H-azirines with alkynyl ketones

Considering the configuration of the obtained N-acetyl-aziridine adduct 16, the researchers proposed the mechanism illustrated in Scheme 8, which starts with the formation of the dinuclear Zn-ProPhenol complex. The catalyst’s Brønsted basic site facilitates the coordination and deprotonation of the alkynyl ketone 14 generating zinc enolate V. Subsequently, the 2H-azirine 2 coordinates to the Lewis acidic site of V, forming complex VI, which directs the Re face attack of the alkynyl ketone on the 2H-azirine, leading to the formation of complex VII. Finally, protonation and decomplexation of VII by a second equivalent of alkynyl ketone 14 yield the Mannich adduct 15 while regenerating zinc enolate V.

Scheme 8.

Proposed mechanism for the Zn-ProPhenol catalyzed asymmetric Mannich reaction

More recently, an enantioselective copper-catalyzed synthesis of aziridines with consecutive tetrasubstituted stereocenters has been reported by Xie et al. [67]. This procedure entails the Cu-mediated coupling of cyclic imino esters 17 with 2H-azirines 11 under mild reaction conditions (Scheme 9). Therefore, the model reaction between 2H-azirine 11 (R = Ph, R1 = H) and imino ester 17 (X = CH2, R2 = Ph) in the presence of Cu (MeCN)4PF6 (5 mol%), with different chiral Phosferrox ligands (5.5 mol%), and a catalytic amount of a base was explored. The reaction proceeded more efficiently when toluene was used as the solvent, using K2CO3 as the base, and the highest enantioselectivity with similar yields and diastereoselectivity was obtained using (S,Sp)-Ph-Phosferrox L3 as the ligand (83– > 99% ee, 61–99% yield, > 95:5dr, Scheme 9). Concerning the scope of the cyclic imino esters 17, it seems that the electronic properties and the position of substituents on the phenyl ring of ketimine esters have minimal influence on reactivity and stereoselectivity, except in the case of ortho-methyl substitution, which has a slightly negative effect on the enantiocontrol, mainly due to the increased steric hindrance. Likewise, not only aromatic cyclic imino esters 17 but also serine derived ketimine ester 17 (X = O, R2 = Ph) could efficiently participate in the reaction to afford aziridines 18 in excellent yields with high diastereo- and enantioselectivity. Notably, a wide variety of azirine substrates 11, including 3-aryl or 3-alkyl-2H-azirines and 2,3-diphenyl-2H-azirine, were well-tolerated, yielding the corresponding aziridines 18 with vicinal tetrasubstituted stereocenters in good to high yields with excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9.

Copper-catalyzed coupling of cyclic imino esters with 2H-azirines

The authors suggest that the reaction should initiate with the formation of a chiral Cu/(S,Sp)-L3 catalyst VIII and subsequently converts imino ester 17 into the nucleophilic N-metalated azomethine ylide IX in the presence of a base (Scheme 10). According to the absolute stereochemistry of aziridines 18 and based on previous reports [68–70], azirine 19 would approach the Si face of IX to minimize steric repulsion with the phenyl ring of the chiral ligand (S,Sp)-L3. Furthermore, the nitrogen atom of 2H-azirine 19 coordinates to the Cu(II) center in complex IX, which promotes a favorable nucleophilic attack from the Re face of 2H-azirine 19, leading to the formation of (S,S)-18 (TS–2). In contrast, without coordination to the Cu complex, nucleophilic attack from the Si face of 2H-azirine 19 would yield the (S,R)-18 product (TS–3).

Scheme 10.

Proposed transition state for the coupling reaction of cyclic imino esters with 2H-azirines

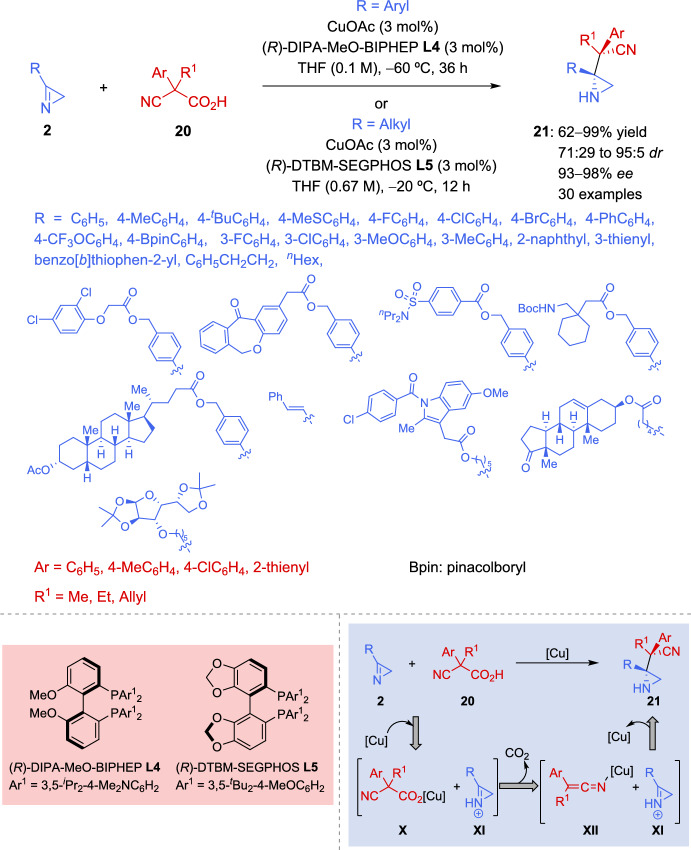

By combining nucleophilic generation through copper(I)-catalyzed decarboxylation and activation of poorly electrophilic 2H-azirines through protonation with carboxylic acids, Zhang et al. [71] reported an asymmetric decarboxylative Mannich-type reaction between α,α-disubstituted cyanoacetic acids 20 as pronucleophiles and 2H-azirines 2. This approach enables the formation of chiral aziridines 21 featuring vicinal tetrasubstituted and acyclic quaternary stereogenic carbon centers in good to excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity (Scheme 11). The authors studied the substrate scope of aromatic 2H-azirines 2 with 3 mol% of CuOAc-(R)-DIPA-MeO-BIPHEP (Cu(I)/L4) complex. Electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups were well tolerated at the para-position of the phenyl group. While diastereoselectivity was moderate in certain cases, the yield and enantioselectivity remained consistently high to excellent. 2H-Azirines 2 with a substituent at the meta-position of the phenyl ring performed well to afford aziridines 21 in good to excellent stereoselectivity. Conversely, ortho-substituted aromatic azirines 2 was not accepted largely due to the increased steric hindrance. As outlined in Scheme 11, aromatic 2H-azirines 2 containing complex moieties underwent the copper(I)-catalyzed decarboxylative Mannich reaction efficiently to afford aziridines 21 in excellent yield, high diastereoselectivity, and with excellent enantioselectivity. Additionally, aliphatic 2H-azirines 2 can also be used in this approach. However, since (R)-DTBM-SEGPHOS L5 provided better diastereoselectivity control than (R)-DIPA-MeO-BIPHEP L4 in the reaction with aliphatic 2H-azirine 2 (R = PhCH2CH2, 6:1 dr versus 4:1 dr), L5 was selected for substrate scope of aliphatic 2H-azirines. Although the diastereoselectivity was not satisfactory in some cases (71:29–86:14 dr) the yields and enantioselectivity were excellent in almost cases (Scheme 11). Furthermore, the aryl group of α,α-disubstituted cyanoacetic acid 20 was successfully broadened to include 4-MeC6H4, 4-ClC6H4, and 2-thienyl groups, achieving high to excellent stereoselectivity.

Scheme 11.

Catalytic asymmetric decarboxylative Mannich reaction of 2H-azirines

Taking into account the basicity and low electrophilicity of 2H-azirines, the authors proposed a strategy in which basic 2H-azirines may be activated via protonation by cyanoacetic acid 20, generating highly electrophilic iminium species XI [72, 73] (Scheme 11). Simultaneously, anion exchange results in the formation of copper(I) cyanoacetate X, which generates the nucleophilic copper(I) ketenimide XII through CO2 extrusion. Finally, the asymmetric addition of nucleophilic copper(I) ketenimide XII to the electrophilic iminium species XI enables the efficient formation of aziridines 21 featuring adjacent chiral tetrasubstituted and acyclic quaternary stereocenters.

Based on previous reports [74] on the development of copper-catalyzed enantioselective addition reactions to aldimines with silicon nucleophiles, Zhao et al. [75] described the uncovered enantioselective addition reactions of silicon nucleophiles to 2H-azirines. C-Silylated, N-unprotected aziridines with consistently high levels of enantioinduction were obtained by means of an asymmetric copper-catalyzed silylation of 2H-azirines 2 with a silyl boronic ester 22 as a silicon pronucleophile. The C-silylated aziridines 23 obtained as a result show high yields and excellent enantioselectivity (Scheme 12). Using McQuade’s catalyst [74, 76], 1.5 equiv of NaOMe, and 1.5 equiv of Me2PhSiBpin 22, C-silylated aziridines 23 were attained in 95% yield with only 81% ee. However, screening other catalyst systems successfully led with ligand (R,R)-Ph-BPE L6, which afforded 85% yield of C-silylated aziridine 23 with 95% ee in the presence of Cu(MeCN)4PF6 as the copper salt and LiOtBu as the alkoxide base (Scheme 12). This methodology demonstrated excellent functional group tolerance as it accommodated alkyl and aryl substituents at C–3 of the 2H-azirine 2 giving to the formation of adducts 23 in good yields and with high enantioselectivity. Conversely, a thienyl group as an example of a heteroaryl group afforded 23 with a low ee value of 77%.

Scheme 12.

Asymmetric copper-catalyzed silylation of 2H-azirines

Based on a well-established model for chiral copper(I) complexes with (R,R)-Ph-BPE L6 [77, 78], two reasonable transition states were proposed to outline the enantioinduction mechanism of the (R,R)-Ph-BPE-copper(I) catalyst (Scheme 12). Therefore, one of the available quadrants in the chiral catalyst’s pocket can host the substituent at C–3 of 2H-azirine 2 (left), whereas a less favorable transition state would experience steric hindrance between that substituent and a phenyl group of the ligand backbone (right). This supports the assignment of S as the induced absolute configuration.

Catalytic asymmetric hydrophosphination has been mainly limited to reactions with highly reactive Michael acceptors, and no catalytic methods have been described so far for the selective introduction of a phosphine moiety into the aziridine ring. However, a very recently report on the catalytic asymmetric nucleophilic addition of diarylphosphines to 2H-azirines assisted by Mn(I)-based systems has been reported by Ni et al. [79]. These Mn(I) catalysts exhibited high reactivity and excellent stereocontrol in hydrophosphination of Michael acceptors [80–82], which, in several instances, exceed catalytic systems based on noble metals. The author’s previous studies on the Clarke catalyst for the hydrophosphination of activated terminal alkenes [82] indicated that the NH moiety of the catalyst could play a crucial role in the stereoinduction step. This prompted the authors to propose that enantiodiscrimination could be improved by increasing steric bulk near the NH moiety. Then, Mn(I) complexes derived from the diastereoisomeric ligands (Rc,Sp,Sc)-L7 and (Rc,Sp,Rc)-L7, which differ from the Clarke catalyst’s ligand by the addition of a methyl group at the benzylic position adjacent to the pyridine moiety, could fulfill this role. Both Mn (I) complexes were tested in the enantioselective hydrophosphination of 2H-azirines 2. However, only (Rc, Sp, Rc)-L7/Mn yielded good results in terms of enantioselectivity (Scheme 13). Even though the base is crucial for catalyst and phosphine activation, studies on this reaction showed that it has a negligible impact on enantioselectivity. The aziridine phosphine sulfides 24 were obtained in yields ranging from 65 to 99% and with enantioselectivity of up to 98% ee, after protection of aziridine phosphine with elemental sulfur. 2H-Azirines 2 with different aryl and alkyl groups at the C–3 position demonstrated strong performance when reacted with diphenylphosphine. For instance, electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups, acetoxyl and phenyl functional groups at the para-position of the phenyl ring, methyl and methoxy substituents at the meta-position of the phenyl ring were properly fitted in this protocol providing products 24 in high yields with excellent enantioselectivity. An increased catalyst loading (6 mol%) is needed when sterically hindered 2H-azirines 2, containing methyl or fluoro substituents at the ortho-position of the phenyl ring, were used. The (Rc,Sp,Rc)-L7/Mn catalytic system demonstrated broad compatibility, effectively accommodating 2H-azirines 2 bearing heteroaryl groups (Scheme 13). Concerning alkyl substitution at the C–3 position of the starting azirine 2, either branched or linear alkyl groups led to the formation of products with yields ranging from high to excellent, along with excellent enantiomeric excess. Other diarylphosphines were also evaluated in the catalytic asymmetric nucleophilic addition of diarylphosphines to 2H-azirines. Thus, using (4-MeC6H4)2PH and (4-MeOC6H4)2PH for hydrophosphination led to the formation of the target products with excellent enantiomeric excess, though the yields were moderate.

Scheme 13.

Asymmetric Mn (I)-catalyzed nucleophilic addition of diarylphosphines to 2H-azirines

As outlined in Scheme 14, the process starts with the formation of the Mn-phosphido complex intermediate XIII, which is generated by the interaction of the (Rc, Sp, Rc)-L7/Mn catalytic system with HPPh2 and the base. Next, the hydrogen bonding between the NH group of the ligand and the nitrogen atom of the 2H-azirine 19 promotes the reaction of species XIII with the 2H-azirine 19, resulting in the formation of species XIV. Once the aziridine phosphine is liberated, it produces species XV, which, through reaction with HPPh2, restores species XIII, allowing it to participate in the subsequent catalytic cycle.

Scheme 14.

Proposed mechanism for the asymmetric nucleophilic addition of diarylphosphines to 2H-azirines

Catalytic Asymmetric Aziridination of Imines

The enantioselective aziridination of imines has emerged as a powerful strategy in modern organic synthesis, offering an efficient route to chiral aziridines. Despite its potential, conventional approaches often rely on pre-existing chiral starting materials or the use of stoichiometric chiral auxiliaries [83–88], limiting their practicality. Therefore, the development of catalytic methods that enable aziridination from readily available achiral precursors remains a crucial challenge in the field.

Organocatalysis

The aza-Darzens reaction has become one of the most straightforward and efficient approaches for the construction of aziridine-containing molecules [40, 89–92]. Asymmetric variants of the acid-catalyzed aza-Darzens reaction were reported by Huang et al., Hu et al., and Antilla et al. [93–95] and Hashimoto et al. [96], providing cis- or trans-disubstituted aziridines with excellent stereoselectivity. Nevertheless, the asymmetric synthesis of trisubstituted aziridines has been less studied [97, 98]. In this context, in 2019, Pan et al. and Wu et al. [99, 100] reported the first enantioselective aza-Darzens reaction of cyclic imines 26 and α-halogenated ketones 25 using a dipeptide-based chiral phosphonium salt 27 as a phase-transfer promoter for the preparation of structurally dense and stereodefined trisubstituted 28 (Scheme 15) and tetrasubstituted aziridines 30 (Scheme 16). Therefore, the O-TBDPS-L-Thr-D-tert-Leu-based phosphonium salt 27 was discovered to be satisfactory in stereochemical control, and the combination of a wide range of cyclic ketimines 26 bearing electron-neutral, electron-donating, or electron-withdrawing groups on the phenyl ring and several α-bromo acetophenones 25 with different substitution in the ortho-, meta-, and para-positions of the phenyl ring, furnished di- (R = H) and trisubstituted aziridines 28 (R ≠ H) in high yields (up to 98%) and with excellent diastereo- (> 95:5) and enantioselectivity (83– > 99.9%) (Scheme 15).

Scheme 15.

Aza-Darzens reaction of cyclic imines with α-halogenated ketones under dipeptide-based chiral phosphonium salt phase-transfer catalytic conditions

Scheme 16.

Enantioselective synthesis of tetrasubstituted aziridines using a dipeptide-based chiral phosphonium salt phase-transfer catalyst

As an extension of this methodology, a more challenging synthesis of aziridine derivatives with all-carbon quaternary stereocenters has been reported for the same group (Scheme 16) [99, 100]. The catalyzed aza-Darzens reaction between cyclic ketimines 26 and cyclic α-bromoketones 29 using a 10 mol% of the dipeptide-based chiral phosphonium salt 27, proceeded smoothly to give the tetrasubstituted aziridines 30 having complex spiro-fused scaffolds in excellent yields and in a highly stereoselective way. As reported in Scheme 16, the reaction is suitable for various cyclic ketimines 26 bearing different aromatic rings and a wide variety of cyclic ortho-, meta-, and para-substituted six-membered α-bromoketones 29 (X = CH2, n = 1), seven-membered α-bromoketones 29 (X = CH2, n = 2), and α-bromobenzopyrones (X = O, n = 1).

Metal Catalysis

The “aza-Darzens-like” reaction, catalyzed by Brønsted or Lewis acids, involving diazocarbonyl compounds and activated imines, stands as a highly reliable and widely employed approach for synthesizing aziridines. This process involves the nucleophilic attack of the diazo carbon on the activated imine, followed by a 3-exo-tet cyclization of the resulting diazonium ion intermediate. Bao et al. have undoubtedly made groundbreaking contributions to the field of enantioselective aziridination of imines using diazo compounds, particularly through the development of vaulted chiral biaryl ligands such as biphenanthrol (VAPOL) and binaphthol (VANOL) [101]. Both catalysts exhibited exceptional enantioselectivity, which contrasts with other reactions where one catalyst typically outperforms the other. This field has been extensively studied [94, 102–104], focusing on the impact of N-substitution in the imine partner [93, 105], the influence of the diazocarbonyl compound [106], and the nature and structural design of catalysts [107]. Within this last scope, in an effort to discover new chiral VANOL ligands, Guan et al. [108] turned their attention to the nature of the substituents in the 3- and 3′-positions of the ligand. As shown in Scheme 17, the ligands were incorporated into boroxinate catalysts, which were used to screen the catalytic asymmetric aziridination of benzhydryl imines 31 with ethyl diazoacetate (32). The cis-aziridines 33 were attained with asymmetric inductions ranging from 64 to 96%. Imines 31 prepared from both benzaldehyde and cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde were used for screening of ligands L8 in the aziridination reaction. Modifying the 3- and 3′-positions of the VANOL ligand L8 with various substituents resulted in catalysts that afford aziridines 33 with slightly enhanced asymmetric inductions for both imines, compared to the original VANOL ligand with the standard phenyl group, with the exception of the para-cyano ligand and the thiophene substituent ligands. The best asymmetric induction of 96% ee was observed with the phenyl imine and a catalyst generated from ligand L8 (R1 = 3,5-Me2-4-MeOC6H2). The incorporation of alkyl groups in the 3- and 3′-positions of VANOL resulted in a dramatic loss of asymmetric induction in the resulting aziridines 33.

Scheme 17.

Catalytic asymmetric aziridination mediated by BOROX catalysts from 3,3′-disubstituted VANOL ligands

The synergetic effects of these ligands L8 and the electronic properties of the imines are also examined in the aziridination reaction. However, no significant improvement was observed in the asymmetric induction using the electron-rich imine derived from para-methoxybenzaldehyde and the electron-poor imine derived from para-nitrobenzaldehyde. The combination of substituents at both the 3,3′- and 7,7′-positions of the VANOL ligand L9 (Scheme 17) generally led to slightly improved results in the aziridination of the benzaldehyde-derived imine, compared to ligands L8 with substituents only at the 3,3′-positions. The authors also reported for the first time the X-ray structure of a boroxinate catalyst generated from a VANOL-derived ligand L8 (R1 = 3,5-Me2-4-MeOC6H2) and the imine 31 (R = Ph).

In another study of the same group [109], various alcohols and phenols are used for the generation of different boroxinate catalysts from either VANOL or VAPOL ligands. The aziridination reaction of benzhydryl imines 31 (R = Ph, C6H11) with ethyl diazoacetate (32) (see Scheme 17), using the generated catalysts, assume that the asymmetric induction in the aziridine product increases as the electron-donating ability of the alcohol or phenol becomes stronger. The authors support a mechanism where the boroxinate catalyst activates the imine through proton donation, with the resulting chiral anion organizing both the iminium and the diazo compound via hydrogen-bonding interactions. In the same study, the influence of electronic modulation in the VANOL ligand was investigated in the aziridination of imines 31 (R = Ph) with ethyl diazoacetate (32), using the boroxinate catalyst derived from a series of 5,5′-disubstituted VANOL ligands. However, after generating and evaluating all the catalysts, no correlation was observed between the asymmetric induction in the aziridines and the electronic properties of the substituents at the 5- and 5′-positions of the ligand.

A diastereo- and enantioselective Brønsted acid catalyzed aziridination of in situ formed aldimines and difluorodiazoethyl phenyl sulfone for the preparation of CF2-functionalized aziridines was described by the group of Tan et al. [110]. The multicomponent reaction involves 4-methoxyaniline (34), arylglyoxal monohydrate 35, and difluorodiazoethyl phenyl sulfone (38) (Scheme 18). Several chiral phosphoric acids were screened in the aziridination reaction; however, these efforts led to either a complete lack of conversion or an absence of enantioselectivity. Since arylboronic acids have been used to enhance Brønsted acidity in asymmetric organocatalysis when paired with chiral diols or chiral amino alcohols, the authors hypothesized that combining arylboronic acids with chiral Brønsted acids could establish a complementary catalytic platform. Indeed, a variety of BINOL-derived disulfonimides was employed as chiral additives in combination with 2-carboxyphenylboronic acid (36) for the multicomponent reaction. The best results in terms of both yields and enantioselectivity were observed by a combined strong Brønsted acid system consisting of chiral disulfonimide 37 and boronic acid 36 (Scheme 18). Given the limited solubility of aziridines 39, a dissolution–filtration process using isopropanol proved effective in enhancing the final dr (> 98:2), as well as the ee values (up to 99% ee). This procedure was not compatible with arylglyoxal monohydrates bearing strong electron-withdrawing groups.

Scheme 18.

Asymmetric aziridination of in situ imine formation catalyzed by disulfonimide-arylboronic acid combination

Supramolecular hosts are regarded as hybrid frameworks that emulate enzymes by achieving significant rate enhancements and selectivity through non-covalent interactions (NCIs), while retaining the simplicity and broad applicability of small-molecule catalysts [111–113]. Unlike enzymes and small-molecule systems, the importance of scaffold flexibility in promoting NCIs within supramolecular systems is often overlooked, and its impact on reaction rate and selectivity remains poorly understood. Supramolecular cage-mediated asymmetric catalysis offers an excellent opportunity to investigate the influence of cage flexibility on reaction outcomes; however, this area of supramolecular asymmetric catalysis remains largely unexplored [114, 115]. In addition, little progress has been made in the development of supramolecular host catalyst libraries. Recently, Bierschenk et al. [116] reported the preparation of a series of new chiral ligands to evaluate the impact of ligand architecture on reaction selectivity (Scheme 19). The diversification strategy for supramolecular host involved introducing various chiral amides at its apex. This was accomplished by constructing a library of chiral biscatecholate ligands through sequential amide bond formation reactions followed by boron tribromide-mediated deprotection of the catecholate oxygens. Enantiopure gallium-based supramolecular host serves as an effective catalyst for asymmetric aza-Darzens condensation between aromatic amines 40, aldehydes 41 and ethyl 2-diazopropanoate (42), delivering aziridine 43 (R1 = H, R2 = Et) with enantioselectivity of up to 98% ee along with excellent yield (Scheme 19). This level of selectivity is exceptional, especially given that this host lacks a high-performance chiral ligand, catalyst, or directing functional group, with enantioinduction solely arising from its supramolecular chirality. The study of different gallium-based hosts revealed that reactions with larger substrates exhibit varying reactivity, indicating that these hosts differ in their flexibility to accommodate the transition state. The selectivity observed in the aza-Darzens condensation was found to correlate with the exchange rate of a model non-reactive cationic salt, indicating that the most flexible hosts exhibit the highest selectivity for the condensation reaction. Aluminum-based host was less flexible and selective than the previous one, providing aziridine 43 (R1 = H, R2 = Et) in 47% yield and 77% ee. Whereas indium-based supramolecular host L10 (Scheme 19) appeared to be the most flexible and selective catalyst affording aziridines 43 in poor to high chemical yields (29–93%) with enantioselectivity ranging from 89 to 99% ee, except for aziridine 43 (R2 = H) derived from formaldehyde (5% ee).

Scheme 19.

Supramolecular host-promoted enantioselective aza-Darzens reaction of in situ imine formation

Catalytic Asymmetric Aziridination of Alkenes

Several methodologies for the synthesis of asymmetric aziridines use alkenes as starting materials. Some of them involved organocatalyzed reactions, while most rely on different metals for their synthesis. First, we review the organocatalyzed examples that have yielded enantioselective aziridines using different approaches.

Organocatalysis

In 2018, Mennie et al. described the diastereo- and enantioselective β-fluoroaziridination of cinnamyl tosylamide 44 derivatives, employing HF-pyridine as a nucleophilic fluoride source, together with mCPBA as a stoichiometric oxidant, and a chiral aryl iodide (R,R)-45 as the catalyst [117]. The ArI(III) intermediate 46 with an appropriately positioned nitrogen nucleophile, is crucial for the generation of the β-fluoroaziridine 47 as a single diastereoisomer with high enantioselectivity (80–97% ee). Electron-deficient substituents are required to undergo the reaction in a suitable manner, although hydroxyl derivatives can be obtained employing triflate-protected O-aryl substituents (Scheme 20). A considerable decrease in the reactivity and enantioselectivity was observed when a trisubstituted alkene was tested (48: 44% yield, 61% ee).

Scheme 20.

Catalytic diastereo- and enantioselective fluoroaziridination of alkenes

Chiral proline derivatives have been extensively used in catalytic asymmetric synthesis of a wide variety of organic compounds [118]. Monteiro et al. [119] used them for the asymmetric synthesis of 2-formylaziridines 52, which were subsequently employed to obtain reduced hydantoins. The reaction between protected amines 50 and α,β-unsaturated aldehydes 49 occurred under the catalysis of a chiral amine 51 via iminium and enamine activation, providing the related 2-formyl aziridines 52 with satisfactory yields and stereoselectivity when aliphatic enals were used (Scheme 21). Unfortunately, in the case of aromatic α,β-unsaturated aldehydes 49, aziridine ring opening was observed. A strong electron-withdrawing group and low temperatures (−20 ºC) were required to isolate the corresponding aziridine 52 in good yield, diastereoselectivity, and excellent enantioselectivity.

Scheme 21.

Synthesis of 2-formyl aziridines from α,β-unsaturated aldehydes

The same group took advantage of the developed aziridination reaction, followed by a one-pot Passerini multicomponent reaction, to deliver highly functionalized aziridine-α-acyloxycarboxamides 54 in a sustainable way, using environmentally benign solvents, a metal-free approach, and a step-economical protocol [120]. The procedure was slightly modified to make it greener; therefore, the organocatalyst was adapted to function in alcoholic media. Additionally, the base component was changed from sodium acetate to sodium carbonate to avoid the formation of acetic acid as by-product, which could compete with the acid component of the Passerini reaction. This adjustment enabled the reaction to be performed in a one-pot way (Scheme 22).

Scheme 22.

Sequential organocatalyzed aziridination and Passerini multicomponent reaction

The authors observed three diastereoisomers in the crude 1H-NMR spectrum, and considering the coupling constants and the selectivity of the aziridination reaction, deduced that the major ones were the trans-aziridines (54a and 54b). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis was used to determine the stereochemistry of the major diastereoisomer, which was identified as 54a in all cases.

Another green method for the synthesis of aziridines was described in 2021 by Umeda et al. The aziridination of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds was carried out in the presence of a nitrogen source that was generated in situ by treating tert-butyl carbamate with the oxidant sodium hypochlorite pentahydrate, using a quaternary ammonium salt as a phase transfer catalyst [121]. After optimization of the reaction conditions, the authors demonstrated that the process could be performed in an enantio- and diastereoselective fashion using an optically active phase-transfer catalyst and low temperatures (Scheme 23). In the enantioselective example, the dimethylpyrazole α,β-unsaturated carbonyl derivative 57 and cinchonine-derived antracenylmethylated ammonium salt (S)-56 were used, achieving the corresponding aziridine 58 in satisfactory yield and enantioselectivity (77%, 84% ee). Meanwhile, the diastereselective reaction was effectively carried out using L-mentholpyrazole derivative 59 as a chiral auxiliary and cinchonidine-derived (R)-56 as catalyst. After completion of the reaction, the chiral auxiliary was efficiently removed, obtaining the methyl ester derivative without epimerization in the asymmetric center and recovering the chiral auxiliary.

Scheme 23.

Enantio- and diastereoselective aziridination of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds

Subsequently, the same reaction was described using a catalytic system developed by combining chiral amines with sterically demanding yet flexible phosphoric acids [122]. This catalytic system was suitable for several asymmetric organocatalyzed reaction of cyclic enones 61, including aziridination reaction, and allowed the achievement of both enantiomers simply by changing the configuration of the catalyst (Scheme 24). Cyclic enones 61 of different size were used in the reaction, including β-substituted enones (R ≠ H), which, after aziridination reaction, provided tetrasubstituted stereocenters with high enantioselectivity (88–89% ee). Additionally, the authors demonstrated that the reaction showed good tolerance not only toward cyclic enones 61 but also toward acyclic enones 62 although a slight detriment in enantioselectivity was observed in the latter case (64–72% ee).

Scheme 24.

Asymmetric aziridination of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds

A new approach for the synthesis of chiral aziridines was reported by McLean et al. Chiral phosphoric acids were employed to catalyze the enantioselective protonation of catalytically generated prochiral chloroenamines. Treatment of the obtained asymmetric vicinal chloroamines 71 with an appropriate base yielded the corresponding aziridines in good yield and high enantioselectivity [123]. Different chloro vinyl N-aryl derivatives 68 and several anilines 69 were used as substrates, and both transformations could be performed in a one-pot process (Scheme 25). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations and experimental results were in agreement demonstrating that the best results regarding reactivity and selectivity were achieved when cyclohexyl-substituted catalyst 70 was employed.

Scheme 25.

Asymmetric protonation of a catalytically generated chloroenamines and subsequent aziridination

Metal Catalysis

For millions of years, nature has been designing highly efficient catalysts, refining a diverse range of proteins that facilitate most chemical reactions essential for life. Scientists have aimed to integrate nature’s rich toolkit of metalloproteins with the unique reactivity of transition metals in non-biological chemistry. These efforts have largely centered on heme-binding proteins, as heme and its analogues play a fundamental role in synthetic transition-metal chemistry and have been extensively explored as key cofactors [124]. Expanding the repertoire of metalloenzymes beyond heme-dependent systems by developing catalysts that are new to nature, could open up an entirely novel environment of biocatalysis driven by transition metals. In this sense, Goldberg et al. [125] reported a nitrene transfer reaction of styrene assisted by a non-heme iron enzyme. This non-native process is facilitated by the binding of non-native small-molecule ligands (Scheme 26).

Scheme 26.

Activation of a non-heme iron center by small molecules for nitrene transfer reaction of styrene. Structural model of PsEFE with mutated residues highlighted in orange. The coordinating residues H189, D191, and H268 are displayed as sticks, with the Mn ion (used for crystallization) shown as a purple sphere

A set of seven purified α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent iron dioxygenase enzymes was screened for their activity in the intermolecular styrene aziridination reaction using p-toluenesulfonyl azide (73). However, only Pseudomonas savastanoi ethylene-forming enzyme (PsEFE 75) produced aziridine 76 at levels significantly above background. The native form of the enzyme shows a marked increase in aziridination activity when acetate L13 or N-oxalylglycine (NOG) L12 (a broad inhibitor of αKG-dependent enzymes) is introduced, in contrast to α-ketoglutarate L11. The authors’ strategy for enhancing PsEFE’s aziridination activity through directed evolution, focused on modifying the active-site residues using site-saturation mutagenesis, followed by screening to identify variants with improved catalytic performance. A variant with five mutations from the native enzyme was identified as capable of catalyzing the formation of 76, achieving a total turnover number (TTN) of 120 and an 88% ee, favoring the (R)-enantiomer.

Tan et al. [126] described a methodology for the asymmetric aminooxygenation of N-benzoyloxycarbamates of allylic alcohols using a “chiral-at-metal” ruthenium catalyst previously used for C-H amination reaction [127, 128]. When 1,2-disubstituted alkenes were used, the corresponding rearranged benzoylated cyclic carbamates were obtained. In contrast, the trisubstituted alkenes 77 lead to the formation of aziridines 79, which, unfortunately, were unstable and, consequently, difficult to isolate and purify. Therefore, the corresponding aziridines 79 were treated in situ with benzoic acid in the presence triphenylamine, yielding benzoylated cyclic carbamates 80 as single diastereoisomers with high enantioselectivity (Scheme 27). Only the geraniol-derived aziridine 81 proved to be stable and, therefore, could be isolated in good yield and with high stereoselectivity. The authors proposed that a ruthenium nitrenoid intermediate 82 is formed and adds to the alkene, producing intermediate 83. In the case of trisubstituted alkenes, the formation of aziridine 79 is favored over benzoate transfer (Scheme 28).

Scheme 27.

Ruthenium-catalyzed asymmetric aminooxygenation of trisubstituted allylic alcohols

Scheme 28.

Mechanistic proposal for the synthesis of aziridines through asymmetric aminooxygenation of allylic alcohols

An enantioselective radical aziridination reaction was developed in 2021 by Riart-Ferrer et al. [129]. 2,2,2-Trichloroethoxycarbonyl azide (85) was employed as nitrogen source, which, in contact with the appropriate Co(II)-metalloradical catalyst 86, generated a nitrogen radical capable of aziridinating aromatic and electron-deficient alkenes 84. The reaction tolerated a variety of substituents in the aromatic ring of styrenes, such as alkyl groups, halogens, electron-withdrawing groups, and even electron-donating substituents (51–99% yield, 82–94% ee) (Scheme 29). Interestingly, 1,1-disubstituted styrene derivative produced the corresponding aziridine 88, although in low yield and enantioselectivity (32% yield, 48% ee). Furthermore, the reaction was suitable for electron-deficient alkenes, such as alkyl acrylates; albeit, the addition of a catalytic amount of Pd(OAc)2 was required to achieve satisfactory results (42–43% yield, 52–82% ee). Unfortunately, the reactions was ineffective with heteroaromatic, aliphatic, and internal olefins.

Scheme 29.

Co(II)-catalyzed asymmetric aziridination of alkenes with carbonyl azide

A stepwise radical mechanism was proposed based on computational and experimental studies. DFT calculation suggested the formation of intermediate XVI, followed by the elimination of molecular nitrogen, producing the radical intermediate XVII. The next step, which had the highest activation barrier, was the addition of the radical to the styrene derivative. Finally, aziridine formation was exergonic and led to catalyst regeneration, thereby completing the catalytic cycle (Scheme 30).

Scheme 30.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the Co (II)-catalyzed asymmetric aziridination of alkenes with carbonyl azide

Very recently, the same group described the N-heterobicylization of N-sulfamoyl azides using a slightly modified Co(II)-based catalyst [130]. The metalloradical catalysis reaction allows the construction of chiral [3.1.0] bicyclic sulfamoyl aziridines in a stereoselective manner. After catalyst optimization, D2-symmetric chiral bridged amidoporphyrin 90 provided the best enantioselectivity for the homolitically activated intramolecular bicyclic formation. A wide variety of allylic sulfamoyl azides 89 were used in the radical reaction, including aliphatic and aromatic alkenes bearing electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents (Scheme 31). Additionally, the reaction also worked with Z-configured internal alkenes, generating the corresponding aziridines 91 in good yields (95–96%), excellent diastereoselectivity (> 99:1), and good enantioselectivity (62–71% ee).

Scheme 31.

Co(II)-catalyzed asymmetric intramolecular N-heterobicyclization of N-sulfamoyl azides

After experimental and DFT studies, a catalytic cyclic depicted in Scheme 31 was proposed by the authors. Initially, the aminyl radical XIX is generated. Subsequently, 6-endo-trig cyclization occurs producing the kinetically stable alkyl radical XX, which rapidly suffered intramolecular cyclization via 3-exo-tet radical reaction, generating the N-heterobicyclic 91 in a stereoselective fashion.

Kisetset al. synthesized and characterized new C3-symmetric tripodal tris(oxazoline) (TripTOX) ligand L14 in 2021 [131]. These ligands were successfully applied in the copper-catalyzed aziridination of chalcones 92, using of [N-(p-toluenesulfonyl)-imino]phenyliodinane (93) as the nitrogen source. After optimizing the reaction conditions, the process was effective with electron-neutral, weakly electron-withdrawing, and electron-donating groups (Scheme 32). However, heteroaromatic derivatives and strongly electron-withdrawing nitro group led to lower yields and enantioselectivity of the corresponding aziridines 94 (21–64% yield, 50–71% ee).

Scheme 32.

Cu(I)-catalyzed asymmetric aziridination of chalcones with [N-(p-toluenesulfonyl)-imino]phenyliodinane

The synthesis of trisubstituted enantioenriched aziridines has been an important milestone in alkene aziridination reactions. In 2022, Boquet et al. described a methodology for the asymmetric aziridination of diversely substituted alkenes, using aromatic sulfamates as the nitrogen source, iodine(III) as the oxidant, and a low catalyst loading of C4-symmetrical dirhodium(II) tetracarboxylates (Scheme 33) [132]. After optimizing the sulfamates and catalysts, p-tert-butylphenylsulfamate (96) and catalyst 97 were identified as the best reaction conditions. Subsequently, screening of iodine(III) oxidants, solvents, and temperature was carried out, selecting bis(tert-butylcarbonyloxy)iodobenzene, toluene, and –15 ºC, respectively, as the optimal conditions. Finally, the addition of a Brønsted acid improve the enantiocontrol of the reaction.

Scheme 33.

Rh(II)-catalyzed asymmetric aziridination of alkenes with p-tert-butylphenylsulfamate

Monosubstituted N-TBPhs-aziridines 98 (R1 = R2 = H) were successfully obtained from aromatic alkenes bearing either electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups, as well as from aliphatic alkenes (51–91% yield, 74–90% ee). In the case of disubstituted N-TBPhs-aziridines, the reaction was demonstrated to be stereospecific when using trans- and cis-methylstyrene as precursor, yielding the trans-98 (67% yield, 90% ee) and cis-aziridine 98 (90% yield, 70% ee), respectively. Furthermore, outstanding results were provided when trisubstituted alkenes were used. Diversely substituted styrene derivatives demonstrated the reaction’s efficiency in producing trisubstituted N-TBPhs-aziridines 98 in very good yields and with excellent enantiocontrol (51–95% yield, 98–99% ee). Moreover, by changing the catalyst configuration, both enantiomers could be accessed. It is worth mentioning that the reaction is not only enantioselective but also chemoselective, as it does not provide the allylic or benzylic amination reaction in the case of alkenes bearing these susceptible groups. DFT studies performed with 2,2-dimethylstyrene suggested that the key enantioselective step of the reaction is the initial C-N bond formation, occurring at the less hindered and, therefore, more accessible benzylic position, with the Si face being the favored one (Scheme 34).

Scheme 34.

Si approach of p-tert-butylphenylsulfamate to the benzylic position of styrene derivative

Chiral aziridine derivatives have proven to be key intermediates in some enantioselective transformations. For instance, Sun et al. [133] described a chiral salen Mn(III)-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular haloamination/cyclization reaction of alkenes 99. The formation and subsequent ring-opening of the chiral aziridinium ion intermediate 101 were crucial for the preparation of 2-halogenated pyrrolidine derivatives 102 (Scheme 35).

Scheme 35.

Enantioselective intramolecular haloamination of alkenes

Another interesting example in which asymmetric aziridine rings serve as key intermediates was developed by Akhtar et al. for the synthesis of 1H-benzo[c]azepines [134]. For this purpose, N-benzyl-N-cinnamyl amines 103 were treated with PhI = NNs in the presence of chiral Cu(II). Subsequently, the in situ generated aziridines 104 underwent a 7-endo-tet Friedel-Craft cyclization after the addition of an extra quantity of Cu(OTf)2 and an increase in temperature, providing the corresponding azepine derivatives 105 in very good yields, in almost all cases, with excellent stereoselectivity (Scheme 36). Both reaction conditions are suitable to carry out the transformation in a one-pot reaction. The authors suggested that the stereoselectivity of the reaction originates in the aziridination step. The reaction tolerates electron-withdrawing and electron-donating substituents in both aromatic rings.

Scheme 36.

One-pot catalytic asymmetric aminoarylation reaction of N-benzyl-N-cinammyl amines

An exhaustive study on the aziridination of different substituted alkenyl alcohols was performed in 2023 by Fanourakis et al. [135]. The reaction was catalyzed by a rhodium derived ion-paired chiral catalyst which provided a strong interaction with the primary alcohol of the substrate. The authors proposed that the chiral pocket formed by cinchona alkaloid-derived cations plays a key role in the stereoselectivity of the aziridination reaction. After optimization of the reaction conditions perfluorinated aminating agent 110 was selected as nitrogen source, and perfluoroiodosobenzene was used as the oxidant. Furthermore, the addition of C6F5I(OTFA)2 was beneficial, as it provided an easily measurable source of trifluoroacetic acid in solution. A broad scope of substrates was explored, incorporating different alcohol chains lengths and alkene substitution patterns. Successful results were achieved with homoallylic styrenyl alcohols 106 (Scheme 37a) and trishomoallylic styrenyl alcohols 107 (Scheme 37b). The reaction was also compatible with trans-108 (Scheme 37c) and exo-dialkyl alkenyl alcohols 109 (Scheme 37d).

Scheme 37.

Asymmetric aziridination of alkenyl alcohols

The authors proposed that the ion-paired rhodium catalyst 111 is able to discriminate between the prochiral faces of the alkene. For this purpose, the hydrogen-bonding interaction between the primary alcohol of the substrate, the chiral cation, and the sulfonate group is crucial. Simultaneously, the nitrogen source is coordinated to the rhodium, thereby ensuring that the aziridination reaction occurs in a chiral environment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mechanistic proposal for the asymmetric aziridination of alkenyl alcohols

In the case of trisubstituted alkenes 116, although the corresponding aziridines 117 were identified by analysis of the reaction crudes, the aziridine acted as an intermediate that further progressed to the corresponding cyclized tetrahydrofuran or tetrahydropyran 118. Therefore, cyclization was promoted by increasing the reaction temperature, obtaining satisfactory results (Scheme 38).

Scheme 38.

Asymmetric aziridination of trisubstituted alkenyl alcohols and subsequent cyclization

Unfortunately, tetrasubstituted alkenes were not appropriate substrates for the reaction, leading to complex mixtures, while short-chain allylic alcohol derivatives resulted in aziridines with low enantioselectivity. Very recently, the same authors overcame the enantioselectivity limitations of allylic alcohols by slightly modifying the catalyst and reaction conditions [136]. On the one hand, they changed the geminal dialkyl groups adjacent to the carboxylate on the anionic component of complex 120, replacing the cyclobutyl group in 111 with two methyl groups in 120. On the other hand, the linker between the arene and the sulfonate group was replaced by a biaryl derivative, which improved the enantioselectivity. This effect was further enhanced by lowering the reaction temperature. Several trisubstituted allylic alcohols 119 were tested in the optimized aziridination reaction, yielding successful results (Scheme 39). Furthermore, the site selectivity of the reaction was demonstrated with geraniol and nerol derivatives, showing a preference for the aziridination of the alkene closest to the alcohol group.

Scheme 39.

Asymmetric aziridination of trisubstituted allylic alcohols

In recent years, the intramolecular aziridination of alkenes have been scarcely investigated. A very interesting intramolecular nitrene-transfer aziridination was recently developed by Trinh et al. [137]. The reaction was carried out with carbamimidates 122 bearing a bulky protecting group, in the presence of silver catalyst and bisoxazoline-derived ligand L16 (Scheme 40). The transformation was effective with a wide range of disubstituted alkenes 122, such as aliphatic alkenes with several alkyl chain lengths and bulky groups, protected alcohols, heteroarenes, and even complex molecules. The styrene derivative alkene provided moderate yield and enantioselectivity (37% yield, 62% ee). On the other hand, trisubstituted alkenes 122 also could serve as suitable substrates, producing interesting bicyclic aziridine derivatives 123 bearing a enantioenriched tetrasubstituted stereocenter. DFT studies conducted by the authors demonstrated that the indane arms and cyclopropyl backbone of the ligand are necessary to obtain a rigid structure required to adopt a completely planar conformation, which lead to an effective transition state that induces stereoselectivity.

Scheme 40.

Asymmetric intramolecular aziridination of carbamimidates

Although many examples of aziridination of alkenes have been described in recent years, most of them employ activated alkenes as starting materials. Gross et al. focused their attention in the development of a general methodology of asymmetric aziridination of unactivated alkenes [138]. For this aim, a planar chiral rhodium(III) indenyl catalyst was used in combination with a base and a silver halide scavenger to activate the catalyst. The transformation was applicable to a broad range of alkyl chains, including functionalized ones with several heteroatoms, and was also effective with complex substrates bearing heterocycles (Scheme 41). Chiral alkenes 84 with the stereocenter at the γ-position relative to the alkene provided successful results. However, when the stereocenter was shifted to the β-position, a detriment in yield was observed, although the stereocontrol was maintained. Disubstituted alkenes were also evaluated. While 1,1-disubstituted derivatives were not appropriate substrates, an interesting result was obtained with 1,2-disubstituted alkene, yielding the corresponding cis-aziridine 127 with good stereocontrol.

Scheme 41.

Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric aziridination of unactivated alkenes

Next, the authors studied the regioselectivity of the transformation using terminal alkenes with an additional activated alkene, demonstrating the selectivity of the reaction favors the unactivated terminal alkene (Scheme 42).

Scheme 42.

Asymmetric aziridination of substrates bearing activated and unactivated alkenes

DFT studies conducted after evaluating different mechanistic proposals suggested that the formation of amide XXI, followed by the subsequent olefin insertion step, was crucial for the enantioselectivity of the reaction. A plausible catalytic cycle is depicted in Scheme 43.

Scheme 43.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the asymmetric aziridination of unactivated alkenes

Wang et al. published a nearly simultaneous report on the aziridination of unactivated alkenes [139]. In this case, the best results were achieved with the chiral cyclopentadienyl-rhodium(III) catalyst 132 (Scheme 44). The reaction showed broad applicability, converting a wide variety of aliphatic unactivated alkenes 84 into enantioenriched aziridines 133. The reaction tolerated several functional groups, such as halogen atoms, ether, ester, hydroxyl, O-tosyl, O-tert-buthyldimethylsilyl, nitro, amino, acyloxy, and phthalimide groups. In all cases, aziridines 133 were obtained in moderate to excellent yields with high enantioselectivity. Similarly, the regioselectivity of the reaction was confirmed by adding activated alkenes into the substrate and observing that the transformation selectivity occurred at the unactivated terminal alkene. Unfortunately, the aziridination reaction failed when aromatic alkenes, such as styrene, or disubstituted 1,1- or 1,2-alkenes were employed.

Scheme 44.

Catalytic asymmetric aziridination of unactivated alkenes

On the other hand, the authors also studied the scope of the nitrene source by varying the substituents on the aromatic ring of the N-pivalolyloxy sulfonamide 131. Successful yields and enantioselectivity were obtained with substituents of varying electronic properties (Scheme 44). The reaction also tolerated bulky groups and thiophene derivatives. Although a decrease in yields and enantioselectivity was observed with alkyl derivatives (77–84% ee), the expected aziridines 133 were successfully isolated.

Deuterium-labeling studies were performed to understand the reaction mechanism. The obtained results suggested that a multistep process was involved in the aziridination reaction. The authors proposed that the rhodium first coordinates with the amine group of sulfonamide 131, followed by the alkene migratory insertion in a stereocontrolled fashion, providing intermediate XXVI or XXVII. After N–O bond cleavage and C-N bond formation, the desired aziridine 133 is obtained, regenerating the catalyst and completing the catalytic cycle (Scheme 45).

Scheme 45.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the asymmetric aziridination of unactivated alkenes

Kinetic Resolution and Desymmetrization

Kinetic Resolution and Desymmetrization of Aziridines

Significant progress in catalytic asymmetric approaches was achieved in 2009 when Larson et al. pioneered the desymmetrization of meso-aziridines. This strategy was applied to functionalized aromatic thiols in combination with VAPOL phosphoric acid. The resulting α-thioamides were obtained in good to excellent yields with excellent enantioselectivity [140].

In 2021, Sun et al. [141] described the first organocatalytic kinetic resolution of unactivated aziridines using sulfur nucleophiles, achieving excellent enantioselectivity. A wide range of racemic aziridines 134 bearing different substituents proved to be suitable substrates for this ring-opening reaction, using 2-mercaptobenzothiazole 135 as the nucleophile. Additionally, various chiral phosphoric acids (CPAs) were examined as potential catalysts, with catalyst 136 providing the highest enantioselectivity. The corresponding β-amino thioether products 137 and the remaining aziridines (S)-134 were all obtained with good to high enantioselectivity (Scheme 46). Additionally, different substituted mercaptobenzothiazoles 135 were tested, with the 6-ethoxy-substituted (R1 = 6-EtO, 135) exhibiting excellent selectivity factor (s > 200). However, other sulfur nucleophiles, such as thiophenol, aliphatic thiols, and thioacids, did not react under the standard conditions. Remarkably, the results obtained in a large scale (2 mmol of rac-134) were similar in efficiency and stereoselectivity, highlighting the robustness of this methodology.

Scheme 46.

Organocatalytic kinetic resolution of unactivated racemic aziridines using 2-mercaptobenzothiazoles as nucleophiles

There are only a few asymmetric methods available for the synthesis of chiral heterocyclic systems containing fused aziridine rings, such as aziridinoquinoxaline. In 2023, Jhang et al. [142] described a highly selective parallel kinetic resolution, providing access to new chiral aziridinoquinoxalines. This resolution was achieved using racemic aziridinoquinoxaline 138 under transfer hydrogenation conditions with the standard tert-butyl-substituted Hantzsch esters, in the presence of 5 mol% (R)-TRIP 139 as the catalyst. The resolution was successfully accomplished for 16 different substrates, yielding highly enantioenriched diastereoisomers with the (R)-configuration of the newly formed stereocenter: 32–61% yield with 64–99% ee for the (R,R,R)-diastereoisomers 140, and 7–46% yield with 97–99% ee for the (S,S,R)-diastereoisomers 140 (Scheme 47). A detailed analysis of the product and starting material distribution suggests a complex interplay of the catalyst- and substrate-imposed factors effecting the enantio- and diastereoselectivity. In all cases, a highly enantioselective formation of the diastereoisomer (S,S,R)-140 was observed, as the enantiomer (R,R,S)-140 would result from a double-mismatched reaction. Similarly, high enantioselectivity for (R,R,R)-140 are attributed to the faster formation of the double-matched enantiomer (R,R,R)-140 in comparison to the mismatched enantiomer (S,S,S)-140, which suffers from opposing catalyst- and substrate-dictated selectivity (Scheme 47a).

Scheme 47.

a Enantioselective parallel kinetic resolution of aziridinoquinoxalines. b Addition of thiophenol to the reaction mixture at the end of the reduction of aziridinoquinoxalines

The reduction conditions could be used to produce p-nitrophenyl- and p-trifluoromethyl-substituted products, but the resulting mixtures of diastereoisomers (R,R,R)-140/(S,S,R)-140 could not be readily separated by flash chromatography. To address this challenge, a one-pot functionalization protocol was employed to selectively convert (S,S,R)-140 into a more easily separable compound 141. Notably, the aryl-substituted aziridines (S,S,R)-140 were found to be significantly more reactive toward thiophenol than their corresponding diastereoisomers (R,R,R)-140. Thus, the simple addition of thiophenol to the reaction mixture at the end of the reduction lead to quantitative and selective formation of the ring-opened product 141 in 99% ee. The resulting reaction mixture could be conveniently purified to separate (R,R,R)-140 from 141 (Scheme 47b).

The ring-opening of racemic aziridines via kinetic resolution with sulfur nucleophiles can lead to both enantiomerically enriched β-amino thioethers and aziridines. In 2019, Zhang et al. [143] developed an efficient kinetic resolution of racemic trans-2-acyl-3-aryl-N-tosylaziridines 142 using La(OTf)3 and chiral N,N-dioxide ligands L17 as catalyst, along with 2-mercaptobenzothiazoles 135 as active sulfur nucleophiles. A variety of enantioenriched β-amino thioethers 143 and chiral trans-aziridines 142 were obtained in good yields with high levels of stereocontrol (up to 96% ee). Furthermore, 4,5-dihydrothiazole-2-thiol 135, lacking the phenyl ring, also afford promising results in kinetic resolution. Other sulfur nucleophiles, such as 4-methylthiophenol and 2-thionaphtol, were tested but resulted in low yields (< 10%), while cyclohexanethiol showed no reaction under these conditions (Scheme 48).

Scheme 48.

Kinetic resolution of racemic trans-2-acyl-3-aryl-N-tosylaziridines via Lewis acid catalysis using sulfur nucleophiles

Zhang et al. reported an efficient catalytic kinetic resolution (KR) and dinamic kinetic asymmetric transformation (DyKAT) of racemic N-tosylaziridines 134 via [3 + 3] annulation with isatin-derived enals 144, by the cooperative catalysis with chiral NHCs and copper complexes. This approach led to highly enantioenriched spirooxindoles 146 and (R)-N-tosylaziridine derivatives 134. Through process optimization, the best results were obtained using chiral NHC precatalyst 145 and the chiral diphosphine ligand L18. The presence of a base significantly improved reaction efficiency. In the absence of either copper, the chiral diphosphine ligand, or NHC precatalyst, the reaction yielded less than 5% product, confirming their essential role (Scheme 49) [144].

Scheme 49.

Kinetic resolution of racemic N-tosylaziridines via NHC/Cu cooperative catalysis

The authors carried out a series of mechanistic studies, which suggested that the NHC catalyst 145 plays a dual role: acting both as a Lewis base organocatalyst and as a ligand coordinating with the copper-diphosphine complex to modulate the catalytic activity. The chemoselectivity between the KR and DyKAT could be switched by adjusting the dosage of the chiral NHC. Furthermore, the presence or absence of the Cu-diphosphine complex determines the reaction pathway.