Abstract

Background and purpose:

Fibrotic remodeling of the lung post-respiratory viral infection represents a debilitating clinical sequela. Studying or managing viral-fibrotic sequela remains challenging due to limited therapeutic options, and a lack of understanding of mechanisms. This study aims to determine whether PDIA3 and SPP1, which are associated with sporadic pulmonary fibrosis, promote influenza-induced lung fibrotic remodeling and whether inhibition of PDIA3 or SPP1 has the potential to resolve viral-mediated fibrotic remodeling.

Experimental Approach:

A retrospective analysis of the TriNetX datasets was conducted. Serum from healthy controls and IAV-infected patients were analyzed. An inhibitor of PDIA3, Punicalagin, and a neutralizing antibody for SPP1 were administered in mice. Macrophage cells treated with M-CSF were used as a cell culture model.

Key Results:

TriNetX data set showed a significant increase in lung fibrosis and lung function decline in flu-infected ARDS patients compared to non-ARDS patients. Analysis of serum samples revealed a significant increase in SPP1 and PDIA3 in influenza-infected patients. Similarly, lung PDIA3 and SPP1 expression were increased following viral infection in mouse models. Administration of Punicalagin, two weeks post-IAV infection in mice led to a significant decrease in lung fibrosis and improved oxygen saturation. Administration of neutralizing SPP1 antibody decreased lung fibrosis. Inhibition of PDIA3 decreased secretion of SPP1 from macrophages in association with diminished disulfide bonds in SPP1.

Conclusions and Implications:

Over all we found that PDIA3-SPP1 axis promotes post-influenza lung fibrosis in mice and pharmacological inhibition of PDIA3 or SPP1 is a potential avenue to treat virus-induced lung fibrotic sequela.

Keywords: Lung fibrosis, PDIA3, SPP1, M-CSF, Influenza, lung function, AHR

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Respiratory viruses, including Influenza and SARS-CoV-2, cause lung damage and remain risk factors for progression toward lung fibrotic remodeling long after viral infection(Huang & Tang, 2021). Recent papers suggest that more than one-third of patients who survived severe COVID-19 pneumonia later developed pulmonary fibrosis after hospital discharge(Han et al., 2021). Histopathological presentations of autopsies of IAV or SARS-CoV-2 infections show diffuse alveolar damage (DAD (80–90%)), pulmonary thrombosis (20–58%), and organizing fibrosis in 40–50% of patients(D’Agnillo et al., 2021; Harms et al., 2010; Mineo et al., 2012; Nalbandian et al., 2021). High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) studies have also indicated pulmonary fibrosis (PF) as a long-term morbidity in a subset of patients who recovered from H1N1 pneumonia(Li et al., 2011; Valente et al., 2012). However, mediators and mechanisms of progressive lung fibrosis post-IAV infection are not well understood.

Protein disulfide isomerases (PDIs) are endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-based redox chaperones, which catalyze the formation or isomerization of cysteine disulfide bonds (-S-S-) in proteins (Ferrari & Soling, 1999) The PDIA3, a unique member of the PDI family of proteins, is primarily involved in the redox modification of newly synthesized glycoproteins and is upregulated during ER stress(Jessop, Tavender, et al., 2009). Although PDIA3 has been implicated in diverse human diseases,(Caorsi et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2010; Germon et al., 2023; Kim-Han & O’Malley, 2007; Mizwicki et al., 2013) including influenza infection,(Chamberlain et al., 2019) the role of PDIA3 in virus-induced lung remodeling is not fully elucidated.

We reported that influenza A virus (IAV) infection induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and downstream increases in PDIA3, which catalyzes disulfide bond (-S-S-) formation in numerous proteins, including IAV hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA)(Chamberlain et al., 2019; Chamberlain et al., 2022). A recent study from our lab has demonstrated that PDIA3 is increased in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and further mechanistic studies indicated that PDIA3 enhances the production of pro-fibrotic osteopontin (SPP1) and promotes lung fibrosis in a mouse model of fibrosis(Kumar et al., 2022).

The profibrotic growth factor SPP1 has been implicated in various disease pathologies, including lung fibrosis(Tang et al., 2023). Many cell types produce SPP1, which acts as an extracellular matrix protein in certain conditions(Hatipoglu et al., 2021). Various disease models and patient samples indicated that SPP1 could be detected in the serum and other tissues, and macrophages are the major source of SPP1 in acute tissue injury and inflammatory diseases(Gui et al., 2020; Morse et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022). Whether SPP1 is involved in the pathology of virus-induced pulmonary fibrosis in conjunction with PDIA3 is unknown.

In the present study, we aimed to elucidate whether IAV-induced lung fibrotic sequela is associated with the PDIA3-SPP1 axis and whether inhibition of PDIA3 or SPP1 will attenuate IAV-induced lung fibrosis in mice.

Our retrospective analyses of electronic health records (EHRs) indicated that the percent incidence of lung fibrosis was significantly increased in patients with ARDS post-H1N1 infection. Analysis of a separate cohort of serum samples indicated a significant increase in PDIA3 and SPP1 in IAV-infected patients. Therapeutic phase administration of a PDIA3 inhibitor, Punicalagin (PUN), or neutralizing SPP1 antibody, attenuated IAV-induced lung fibrosis in mice. Mechanistic studies indicated that inhibition of PDIA3 decreased secretion of SPP1 by decreasing -S-S- in SPP1. These results indicate that PDIA3 and its substrate SPP1 potentially promote post-IAV lung fibrotic sequela and are targets for future therapeutics in virus-induced lung fibrosis.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. TriNetX and Human Samples

We performed a retrospective cohort study using TriNetX (Cambridge, MA), a global federated health research network that provides access to patient’s electronic medical records from multiple large member healthcare organizations (HCOs) in the United States. Details of the data source are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

We performed a search query to identify all patients diagnosed with IAV. The search criteria for potential IAV patients were based on specific IAV diagnostic codes or positive laboratory confirmation of IAV. Patients identified with IAV were stratified based on the diagnostic codes for acute respiratory distress (ARD). Patients diagnosed with ARD within 1 month of IAV diagnosis were included in the IAV-ARD group. The control group included patients with no documented diagnosis of ARD within 1 month of IAV diagnosis. All patients with COVID-19 at any time and those with a history of pulmonary fibrosis or IPF (i.e., at any time in the preceding years before the diagnosis of IAV) were excluded from both cohorts. Details of patient selection for IAV-ARD and control cohorts are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

The ARD and control groups were compared after 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM). Pulmonary fibrosis was the primary outcome after IAV diagnosis. Details of the statistical analysis and limitations are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods. All the characteristics of this cohort and analysis are available in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2 |. Human serum sample analysis

Serum samples from a different cohort of Control (n=12) and IAV-infected patients (n=50) were analyzed for pro-fibrotic SPP1 and PDIA3 proteins. Patients admitted to Yale New Haven Hospital medicine service for respiratory symptoms who have been diagnosed with IAV infection have been consented for serum collection as per approved Yale IRB protocol “Host Response to Infection” # 0901004619. Samples were collected prior to COVID-19 and patients did not have other respiratory viral infections detected. Subjects’ characteristics are available in Supplementary Table S2.

2.3 |. Virus

Influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 (PR8) (AVS Bio; Cat no.10100374) (Galani et al., 2022) were used in this study.

2.4 |. Animals

All research studies involving the use of animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at the University of Vermont, Vermont. These studies were carried out per the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All mouse studies described herein were approved by IACUC protocol no. PROTO202000102. C57BL/6NJ mice (Jackson Laboratories) aged around 12 weeks were studied. Mice were intranasally infected with (1500PFU/mouse) of influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 (PR8) (AVS Bio; Cat no.10100374)(Galani et al., 2022) or Mock (UV inactivated) virus. Mice were euthanized at the end of the experiment, and BAL fluid for total and differential cell counts and protein analysis, serum for protein analysis, the right upper lung lobe for collagen measurement, and the rest of the two right lung lobes for western blot, immunoprecipitation, ELISA and RT-qPCR analysis, and the left lung for histologic analysis were collected.

2.5 |. IAV TCID50 analysis

The virus was diluted in a 10-fold gradient with a serum-free DMEM medium. The diluted virus solution (100 μl/well) was added to 96-well plates lined with monolayers of MDCK cells, with six replicate wells used for each concentration and a control group of normal cells. The plates were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 72 hours. Cells were then fixed and stained using 1% crystal violet in formaldehyde. Wells were counted and categorized as cytopathic effect positive or cytopathic effect negative. The amount of virus infection in half of the cell cultures (TCID50, 50% tissue culture infective dose) was calculated using the Reed-Muench method.

2.6 |. Immunoprecipitation

From lung tissues prepared for western blotting, PDIA3 was immunoprecipitated using anti-PDIA3 antibody (LifeSpan Biosciences; LS-B9768). Lung lysates from (Mock (n=4), IAV (n=8), and IgG control IAV (n=1)) were mixed with PDIA3 antibody or IgG isotype control (Invitrogen, catalog No. 31245). All lysates were made from 15 dpi mice lung tissues. PDIA3-bound proteins were immunoprecipitated using recombinant G agarose beads (Invitrogen; 15920–010). Samples were then suspended in a loading buffer with dithiothreitol (DTT) and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Visualization of immunoprecipitated proteins was by conventional western blotting.

2.7 |. Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) measurements

Mice were anesthetized through the intraperitoneal injection of 90 mg/kg of mouse-weight sodium pentobarbital solution (Midwest Veterinary Supply) followed by paralysis with 0.8 mg/kg of mouse-weight pancuronium bromide (MP biomedicals, catalog: 156053). The mice were mechanically ventilated using a Flexivent (SCIREQ, Montreal, QC), and bronchoconstriction was induced using aerosolized methacholine at 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/ml. Saline was used as vehicle control. The values of Newtonian resistance (Rn), tissue resistance (G), and tissue elastance (H) were taken every 10 s for 3 min immediately after the challenge, resulting in a total of 18 measurements for each methacholine dose. Averages of the 18 measurements for each parameter were calculated after excluding values for which the fit of the constant-phase model of impedance returned a coefficient of determination (COD). CODs less than 0.85 were excluded(Chandrasekaran, Bruno, et al., 2023; Chandrasekaran, Morris, et al., 2023).

2.8 |. Administration of Punicalagin

C57BL/6NJ mice were treated therapeutically by the oropharyngeal route at 0.15 mg/kg weight of mice of punicalagin (Cayman Chemical; Cat. No. 13069) 5 times on alternate days.

2.9 |. Blocking SPP1

To examine the role of SPP1 in Influenza infection-induced lung fibrosis, infected mice were treated with anti-SPP1 antibody (R&D Systems, AF808; 37.5 μg) or isotype-specific IgG (R&D Systems, AB-108-C; 37.5 μg) by intraperitoneal route using the same regimen as punicalagin treatment. After the experiments, BALF, serum, and lungs were collected for analysis.

2.10 |. Statistical analysis

All mice studies were repeated at least once. Data were pooled and analyzed by one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) where appropriate and corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni test or Mann-Whitney student’s t-test where appropriate. Data for all results were expressed as mean values ± SD or mean values ± SEM. P values <0.05 were regarded as discovery or statistically significant. The ROUT method was first used to identify outliers in GraphPad Prism 10 with a cutoff of Q = 2%, and they were removed from the analysis. The article’s online data repository provides more detailed information on material and methods.

Details of materials and methods are available online in supporting information.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Influenza infection increases PDIA3 and SPP1

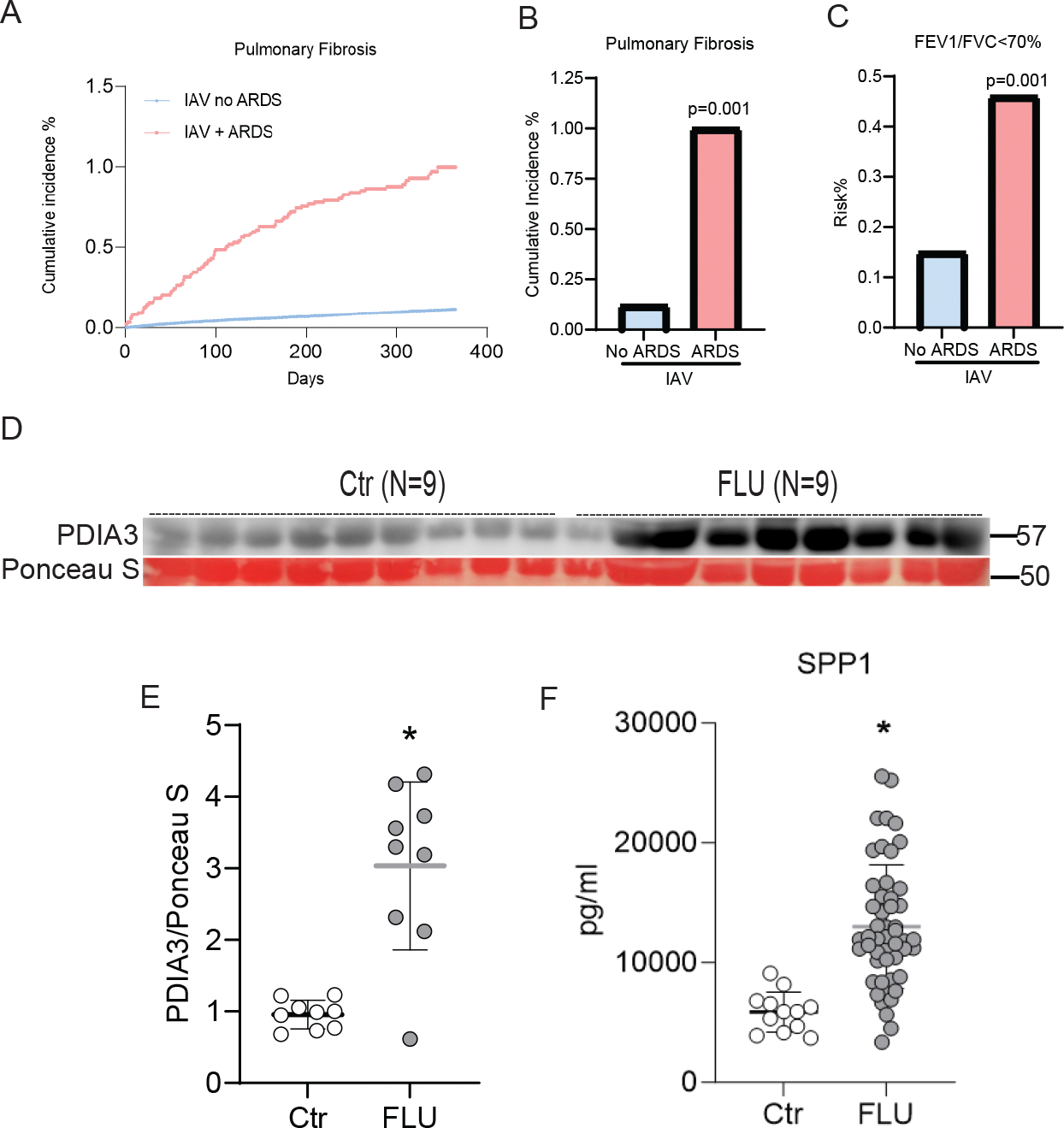

Initially, we wanted to gather data corresponding to increases in the incidence of lung fibrosis in patients with H1N1 infection. After 1:1 propensity score matching by demographics and diagnosis, there were 14,936 IAV patients with and without acute respiratory distress (ARD). Patients from these groups were longitudinally followed for 12 months after the index event to estimate the risk of pulmonary fibrosis and other outcomes. Patients with IAV and ARD were associated with increased risks of pulmonary fibrosis (RR [95% CI] = 1.812 [1.244–2.640]; OR [95% CI] = 1.816 [1.245–2.650]) and FEV1/FVC ≤70% (RR [95% CI] = 3.104 [1.921–5.018]; OR [95% CI] = 3.114 [1.925–5.039]). This retrospective analysis of EHR data sets showed that the percent incidence of lung fibrosis was significantly high in patients with ARDS within one year post H1N1 infection, which is also associated with a higher percentage risk of decline in lung function (FEV1/FVC) (Figure 1 A, B & C).

FIGURE 1. Post-IAV fibrotic sequelae and elevated levels of PDIA3 and SPP1 in patients.

(A and B) Cumulative incidence of pulmonary fibrosis within 1 year post-H1N1 infection; (C) FEV1/FVC predicted (≤ 70%) within 1 year post-H1N1 infection. Patient cohort after propensity matching, IAV without ARDS no IPF n=14,936 and IAV with ARDS no IPF n=14,936. (D) Western blot for PDIA3, (E) quantitation of PDIA3 protein expression in western blot, Control (n=9) and FLU (n=9) patients, and (F) ELISA for SPP1, Control (n=12) and FLU (n=50) patients. * Significance was based on unpaired two-tailed non-parametric Mann-Whitney t-test. Error bars represent ± SD.

The ER-based redox chaperone PDIA3 and its interactor protein SPP1 are important contributors to the progression of lung fibrosis(Gui et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2022; Pardo et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2022). However, there are no known examples of increases in PDIA3 along with SPP1 in patients with H1N1 infection. Therefore in another cohort of patient serum samples from the Yale repository, collected within 48 hours of diagnosis of influenza virus infection, we analyzed PDIA3 and SPP1. These serum analyses showed significant upregulation of PDIA3 and SPP1 in influenza-infected patient serum compared to controls (Figure 1 D, E & F). These results indicated that severe influenza infection leads to significantly elevated levels of lung fibrosis and is potentially associated with increased pro-fibrotic PDIA3 and SPP1 expression in humans.

3.2 |. Influenza A virus (IAV) induces temporal changes in physiological and fibrotic parameters in mice

We infected mice nasopahryngeally with IAV or mock virus to analyze lung injury, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), and lung fibrosis. Mice were euthanized at various time points post-IAV infection (Figure 2 A). While mock-infected mice displayed no significant change in body weight, the IAV-infected mice showed a significant decrease in body weight starting at 10 days post-infection (dpi). Weight loss measured in infected mice was ≤30% at 10 dpi and 15%–20% in most mice at 15 and 21 dpi. Most mice returned to the initial weight by 25 dpi (Figure 2 B). Mice that showed >20% weight loss at 10 dpi are euthanized. Assessment of oxygen saturation (SpO2) levels followed the same trends as body weight. As expected, mock-infected mice maintained ~95% SpO2; however, SpO2 levels in mice infected with IAV decreased to ~70% at 10 dpi and showed significantly low levels even at 15 and 21 dpi. At 25 dpi, the SpO2 level was increased to 85% and returned to the normal levels by 39–60 dpi in IAV-infected mice (Figure 2 C).

FIGURE 2. IAV-driven temporal changes in lung physiology, fibrosis, and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in mice.

(A) Mock or IAV-PR8 virus challenge and harvest regimen; (B) The mean body weight of mice represented as a percentage of the original weight, and (C) mean oxygen saturation levels (SpO2) as determined by pulse-oximetry. *p<0.05 as compared to mock samples by ANOVA; error bars ±SEM. (n=4–10 mice/group). (D) Time-dependent alterations in collagen content in lungs of mice. (E-H) Measurement of Pdia3, Spp1, Fn-1, and Col1a1 mRNA expression from lung tissue. (I) TCID50 measurement of viral burden in the BAL of MOCK and IAV infected mice at different time points. ND: Not Detected and (J) SPP1 protein concentrartion in lung tissues. (K) dead cell protease in BALF and (L) LDH activity in WLL. *p<0.05 as compared to 3-day mock by ANOVA with Bonnferroni’s multiple comparison test; error bars ±SEM. (n=4–10 mice/group). (M) Western blot showing lung SPP1, PDIA3, and β-Actin levels, and (N) Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated PDIA3 and SPP1in lung lysates (n=4–8 samples/group). (O and P) Representative histochemical images of Masson’s trichrome (blue) stained lung sections (n=4 mice/group); Scale bar 2mm and 200 μm, respectively.

IAV-infected mouse lungs also showed a time-dependent increase in collagen deposition compared to the mock-infected lungs as measured by hydroxyproline assay, with significant increases observed by 15 dpi and sustained until 60 dpi (Figure 2 D). Quantitative RT-qPCR revealed a significant upregulation of Pdia3 and Spp1 by 10 dpi in IAV-infected mice compared to mock-infected mice and decreased in the later days. Although not significant, the level of Pdia3 and Spp1 mRNAs tended to be elevated (25–60 dpi) in IAV-infected mice than in mock-infected mice (Figure 2 E & F). The fibrotic markers, including Fn-1 and Col1a1, also showed a similar trend towards increases in post-IAV infection (Figure 2 G & H). IAV PA mRNA expression or median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) from the BALF of mock or IAV infected tissue samples from 3–60 dpi showed that IAV burden was significantly higher in 3 dpi and decreased at 10 dpi and could not be determined beyond 15 dpi (Figures 2 I & S1 A). SPP1 protein levels were significantly increased from 10 to 39 dpi in IAV-infected lungs compared to mock-infected mouse lungs. Although not statistically significant, SPP1 levels tended to be elevated in IAV-infected mice at 60 dpi compared to the control group (Figure 2 J). Lung cytotoxicity, assessed by dead cell protease or LDH activities in BALF, was also significantly elevated in IAV-infected mice (Figure 2 K & L). The increases in pro-fibrotic SPP1 and PDIA3 proteins were also observed in IAV-infected mouse lungs compared to mock-infected lungs by western blot analysis at 15 dpi (Figures 2 M & S1 B & C). PDIA3-SPP1 interaction was assessed by immunoprecipitation of lung tissue lysates with anti-PDIA3 antibody and subsequent western blotting for SPP1 and PDIA3. Here, SPP1 interactions with PDIA3 increased in IAV Infected mice compared to mock at 15 dpi (Figures 2 N & S1 D). Histological changes were observed by Masson’s trichrome staining, revealed lung fibrotic remodeling in mice post-IAV infection (Figure 2 O & P).

We also observed a significant increase in BALF inflammatory cells, including macrophages at 10, 15, 21, and 60 dpi; lymphocytes at 10, 15, 21, and 25 dpi; eosinophils at 10, 21, and 60 dpi; and neutrophils at 3 and 10 dpi in IAV infected mice compared to mock (Figure S1 E–I).

Overall, these data demonstrate that post-IAV infection of mice, various indices of injury, inflammation, and fibrosis were elevated along with profibrotic PDIA3 and its substrate SPP1.

3.3 |. IAV infection increases airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in mice

Viral infection increases methacholine sensitivity and AHR(Chamberlain et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2011; Sterk, 1993). In the present study, we measured AHR in IAV/mock-infected mice in response to increasing doses of inhaled methacholine. At 3 dpi, the methacholine challenge had relatively little differentiating effect in terms of airway resistance (Rn), tissue resistance (G), and parenchymal tissue elasticity (H) in the IAV-infected compared to mock-infected mice, the only significant differences occurring in Rn and G at the maximal methacholine concentration of 50 mg/ml (Figure 3 A–C). More substantial differences between the two mouse groups were apparent at 15 and 21 dpi (Figure 3 D–F and G–I, respectively). Importantly, these differences were manifested most significantly in G and H, with statistical significance occurring at all methacholine doses, in contrast to Rn, which only showed significance at 50mg/ml. At 60 dpi (Figure 3 J–L), the lung function differences had returned almost to those seen at 3 dpi. At other time points, such as 10 dpi, increases in AHR were significant in G and H; at 25 dpi, Rn and G were significantly increased at 50 mg/ml methacholine, and at 39 dpi, only Rn was significantly higher than the mock-infected mice (Figure S 2 A–I). These results indicate that IAV infection exerted its major effects on the pulmonary tissues, with relatively little direct effect on the airways, and that these effects were transient.

FIGURE 3. IAV infection impaired airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR).

Central airway resistance (Rn), peripheral airway resistance (G), and parenchymal tissue elasticity (H) as measured at (A-C) day 3, (D-F) day 15, (G-I), day 25 and (J-L) day 60 using flexivent. *p<0.05 as compared to saline-treated mock samples by ANOVA with Bonnferroni’s multiple comparison test; error bars ± SEM. (n=4–10 mice/group).

3.4 |. The PDIA3 inhibitor Punicalagin (PUN) alleviates IAV-induced lung fibrosis in mice

We previously reported that inhibition or ablation of PDIA3 protects mice from IAV infection- or bleomycin-induced fibrosis(Chamberlain et al., 2019; Chamberlain et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2022). This study explored whether PDIA3 inhibition attenuates IAV-induced lung fibrosis and AHR in mice. We used PUN, a specific inhibitor of PDIA3 activity(Giamogante et al., 2018; Paglia et al., 2021). By measuring dead cell protease activity in IAV-infected lung epithelial cell supernatants, we found ~0.5μM to be the effective concentration, producing 50% of the maximal response (EC50) for PUN (Figure S 3 A). Based on this EC50, we calculated the dose required for oropharyngeal administration in mice by scaling the cell culture dose to mouse lung surface area as described elsewhere(Lenfant, 2000) (Bocci et al., 2011). We tested PUN doses of 0.075 mg/kg and 0.15 mg/kg compared to vehicle control (PBS-VC) instilled via the oropharyngeal route at 14 dpi. We found 0.15 mg/kg significantly decreased IAV-induced lung fibrosis in mice (Figure S 3 B).

We then administered 0.15 mg/kg PUN or VC five times on alternate days between 14 and 22 dpi (Figure 4 A). IAV-infected groups (IAV+VC and IAV+PUN) experienced similarly significant losses in body weight at 15 dpi (Figure 4 B). However, there was an accelerated recovery in %SpO2 in mice treated with the IAV+PUN group, and this gain was just after 3 doses of PUN (Figure 4 C) along with significant decreases in collagen deposition (hydroxyproline) and Col1a1 and Fn-1 expression (Figures 4 D–F). Histological observation of collagen deposition by Masson’s trichrome staining revealed significantly attenuated fibrosis in IAV+PUN mice compared to the IAV+VC group (Figures 4 G & H). Lung injury, assessed by dead cell protease activity, was also significantly diminished in IAV+PUN mice (Figure S3 C). Both the IAV+PUN and IAV+VC groups had 100% survival during the 14–22 dpi treatment period (Figures 4 A & S3 D).

FIGURE 4. PDI inhibitor punicalagin decreases lung fibrosis and AHR in mice.

(A) IAV infection, Punicalagin (0.15 mg/kg administered into the lung via oropharyngeal aspiration) treatment, and harvest regimen. (B) The mean body weight of mice represented as percentage of the original weight. (C) The mean oxygen saturation levels (SpO2) as determined by pulse-oximetry. (D) collagen content in the upper right lung lobe, measured by hydroxyproline content. (E and F) Measurement of Col1a1 (Outlier removed in IAV+PUN (n=1)) and Fn-1 mRNA expression. (G and H) Representative histochemical images of Masson’s trichrome (blue) stained lung sections and histological scoring (n=5–10 mice/group); Scale bar 2mm. (I) Measurement of SPP1 by ELISA. (J) Western blot showing SPP1, PDIA3, and β-Actin expression level in mouse lung lysate and (K) central airway resistance (Rn), peripheral airway resistance (G), and parenchymal tissue elasticity (H) as measured using flexivent. *p<0.05 as compared to MOCK+VC group and #p<0.05 as compared to IAV+VC group by ANOVA with Bonnferroni’s multiple comparison test; error bars ±SEM. (n=5–10 mice/group).

ELISA for SPP1 also showed that the IAV+PUN group produced significantly lower SPP1 (Figure 4 I). Western blots showed that PUN decreased the production of pro-fibrotic SPP1 in IAV+PUN mouse lung lysates compared to the IAV+VC group. However, as found at 15 dpi, there was no robust increase in PDIA3 in IAV-infected mouse lungs at 24 dpi (Figuress 4 J & S3 E–H).

Interestingly, total BALF inflammatory cells, including macrophages, lymphocytes, and eosinophils, were significantly elevated in both groups, with neutrophils being significantly higher in the IAV+VC group and was decreased in IAV+PUN group at 24 dpi (Figure S3 I).

Similar degrees of AHR to methacholine challenge were observed in the IAV+PUN and IAV+VC groups, reflected in elevated levels of Rn and G. The H was not significantly elevated in either IAV group compared to mock-infected mice (Figure 4 K).

To understand the effect of PDIA3 inhibition prior to fibrotic phase (15 dpi), we administered 0.15 mg/kg PUN from 5 dpi (Figure S3 J). Interestingly, 60% of the IAV+PUN but none of the IAV+VC mice died (Figure S3 K). The surviving IAV+PUN mice were in poor condition and were not subjected to methacholine challenge. In addition, their BALF inflammatory cells (macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils) were significantly increased compared to the IAV+VC mice (Figure S3 L). Interestingly we observed that IAV PA mRNA expression was significantly higher in IAV+PUN than IAV+VC(Figure S3 M).

These results suggest that PDIA3 inhibition can be beneficial or detrimental depending on the timing of treatment post-IAV infection. Together, these experiments indicate that PDIA3 promotes IAV-induced lung fibrosis in mice, and inhibiting PDIA3 at 14–22 dpi attenuates lung fibrosis and improves oxygen saturation.

3.5 |. Neutralizing SPP1 attenuates lung fibrosis in mice

We have reported a comprehensive set of PDIA3-interacting proteins, including the pro-fibrotic growth factor, Osteopontin (SPP1)(Kumar et al., 2022). We have also demonstrated that neutralizing SPP1 using an antagonistic antibody decreases bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice(Kumar et al., 2022). Data in figures 1 and 2 showed clear increases in SPP1 post-IAV infection in human and mice. To investigate the role of SPP1 in IAV-induced lung fibrosis, we blocked SPP1 using a neutralizing antibody administered every other day beginning at 14 dpi and assessed on day 26 (Figure 5 A). Lung collagen levels were significantly higher in IAV-infected mice treated with an isotype control IgG antibody compared to mock-infected IgG control mice (Figure 5 B). The anti-SPP1 antibody treatment significantly decreased collagen levels compared to IAV-infected groups treated with IgG control (Figure 5 B). The mRNA analysis for Col1a1 and Fn-1 revealed attenuated fibrosis in mice treated with anti-SPP1 antibody (Figure 5 C & D). Measurement of SPP1 by ELISA also showed a significant decrease of SPP1 protein level in the lung tissue after treatment with anti-SPP1 antibody compared to IAV-infected groups treated with IgG control (Figure 5 E).

FIGURE 5. Blocking SPP1 attenuates lung fibrosis and AHR in mice.

(A) IAV infection, IgG/SPP1-Ab treatment, and harvest regimen. (B) Collagen content in the upper right lung lobe, measured by hydroxyproline content. (C and D) Measurement of Col1a1 and Fn-1 mRNA expression in the lungs. (E) Measurement of SPP1 by ELISA. (F and G) Representative histochemical images of Masson’s trichrome (blue) stained lung sections and histological scoring (n=4 mice/group); Scale bar 2mm. and (H) AHR measurement as Rn, G and H using flexivent. *p<0.05 as compared to MOCK/IgG group and #p<0.05 as compared to IAV/IgG group by ANOVA with Bonnferroni’s multiple comparison test; error bars ±SEM. (n=7–10 mice/group).

Furthermore, Masson’s trichrome staining also indicated a decrease in lung fibrosis in groups administered anti-SPP1 antibody compared to IAV-infected groups treated with isotype control (Figure 5 F & G). We observed significant increases in BALF inflammatory cells post-IAV infection. Furthermore, we observed significant increases in BALF inflammatory cells (macrophages, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils) in the IAV-infected anti-SPP1 group compared to IAV+IgG treated mice (Figure S4 A).

The AHR parameters Rn, G, and H were significantly increased in IAV-infected anti-SPP1 or IgG-treated mice, and there were no significant decreases in AHR parameters in anti-SPP1 antibody groups (Figure 5 H).

These findings suggest that SPP1 plays an important role in IAV-induced fibrosis and that blocking SPP1 decreases lung fibrosis. Interestingly, blocking SPP1 also significantly increases airway inflammatory cells in mice.

Since SPP1 controls inflammation(Wang et al., 2022), we neutralized SPP1 at the early phase of IAV infection. To do so, we initiated anti-SPP1 antibody treatment 1 dpi, performing the treatment 4 times on alternate days (Figure S4 B). This study observed slightly increased Rn and G after blocking SPP1 in the acute phase of IAV infection compared to IAV-infected IgG control-treated mice (Figure S4 C). Interestingly, we observed significantly decreased lymphocytes but increased neutrophils in BALF after blocking SPP1 during the acute phase of IAV infection compared to IAV-infected IgG control-treated mice (Figure S4 D). IAV PA mRNA expression was also not affected by blocking SPP1 during the acute phase of IAV infection compared to IAV-infected IgG control-treated mice (Figure S4 E). Together, these experiments indicate that SPP1 promotes IAV-induced lung fibrosis in mice and that neutralizing SPP1 decreases lung fibrosis. However, neutralizing SPP1 also leads to exacerbated immune during acute phase of infection in mice.

3.6 |. The PDIA3 inhibitor PUN alters disulfide bonds (-S-S-) of SPP1

SPP1 is a secreted protein produced by numerous cell types, including macrophages(Takahashi et al., 2000). Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF or CSF-1) is the primary regulator of macrophage proliferation, differentiation, and survival(Pixley & Stanley, 2004). It has been reported that M-CSF increased the expression of numerous genes in cancer cells, including the SPP1, a major player in lung fibrosis(Mougel et al., 2022). This prompted us to test if M-CSF regulates SPP1 gene expression in macrophages, which are then used as a model for studying PDIA3-based SPP1 regulation in cell culture. As shown in Figure 6 A, murine RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with the PDIA3 inhibitor, PUN, along with M-CSF stimulation. M-CSF stimulation of RAW macrophages significantly increased SPP1. However, PUN treatment markedly decreased SPP1 levels in supernatants of M-CSF-stimulated cells (Figure 6 B). Since PDIA3 is a redox chaperone, we speculated that PUN-based PDIA3 inhibition would affect SPP1 protein -S-S- bonds and may affect secretion but not SPP1 transcription or protein production. When SPP1 was measured in whole cell lysate (WCLs), there was a clear increase in SPP1 protein in the cell lysates with PUN or PUN+M-CSF group compared to PBS or PBS+M-CSF groups (Figure 6 C), indicating PUN based inhibition of PDIA3 increases retention of SPP1 in the cells. This contrasting difference between extracellular and intracellular SPP1 levels in PUN-treated samples pointed towards a deficiency in SPP1 secretion after PUN treatment, leading to the accumulation of SPP1 inside the cells.

FIGURE 6. The PDI inhibitor punicalagin alters the disulfide bond of SPP1.

(A) M-CSF stimulation, Punicalagin treatment, and harvest regimen in RAW 264.7 cells. (B) Measurement of SPP1 24 hr post-M-CSF stimulation and punicalagin treatment in the supernatant, and (C) in whole cell lysate. *p<0.05 compared to PBS treated cells and #p<0.05 compared to M-CSF/PBS group by ANOVA with Bonnferroni’s multiple comparison test; error bars ±SEM. (n=3 samples/group). (D) Schematic showing biotin switch assay and subsequent labeling of reduced sulfhydryl groups by MPB. (E and F) Western blot and densitometry analysis of thiol content of SPP1 following punicalagin treatment and MPB labeling with neutravidin pulldown in whole cell lysate (upper blot) (n=3 samples/group), Western blot showing SPP1, PDIA3, and β-Actin expression level in whole cell lysate (lower blots) (n=3 samples/group) and (G and H) Western blot and densitometry analysis of thiol content of SPP1 following punicalagin treatment and MPB labeling with neutravidin pulldown in mouse lung lysate (upper blot) (n=4 samples/group), Western blot analysis of SPP1, PDIA3 and β-Actin in mouse lung lysate (lower blots) (n=4 samples/group).

Since PDIA3 is involved in -S-S- formation in many proteins, we speculated that inhibition of PDIA3 by PUN may alter -S-S- bonds in SPP1. Using a -S-S- labeling method (Chamberlain et al., 2019-see materials methods), the SPP1 -S-S- modification was analyzed. Briefly, -S-S- were labeled with a biotin switch method using DTT and biotinylated alkylating agent (MPB); the proteins that were labeled with MPB were recognized as proteins with intact -S-S- bonds, and biotinylated proteins were pulldown using streptavidin beads and analyzed using a Western blot for specific proteins (Figure 6 D). In the subsequent Western blots, we found that M-CSF+PUN samples had no -S-S- formed in SPP1 (no bands) compared to M-CSF+VC (PBS) lanes (Figure 6E-upper blot and desitomtery Figure S5 F). Western blots of whole cell lysates (WCL) showed more SPP1 retained in the cells in PUN-treated samples compared to PBS or M-CSF alone (Figure 6 E-lower blots, & desitomtery Figure S5 F). We did not observe any M-CSF-dependent increases in PDIA3 in WCL. Next, we investigated whether PUN treatment altered -S-S- bond formation of SPP1 in mice. We performed a biotin switch assay with lung lysates from the mouse experiments. IAV-infected PUN-treated mice (IAV+PUN) showed a significant decrease in the -S-S- bond of SPP1 compared to IAV+VC mice, as observed in Western blot (Figure 6 G-top blot, & densitometry Figure S5 H). The western blots with whole lung lysates (WLL) showed that IAV+VC samples have increased SPP1, which was diminished with PUN treatment. Since this is an analysis of the whole mouse lung, we could not discern the intracellular and extracellular status of SPP1 in mice post-PUN treatment.

These results suggest that PDIA3 inhibitor PUN decreases -S-S- in SPP1, and that deficit in the formation of PDIA3-mediated -S-S- has significantly decreased SPP1 secretion/production in cells and mice.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Influenza virus infection is a global public health challenge with mild to severe complications. The subsequent development of lung remodeling following influenza virus infection has become an area of intense research(Cipolla et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019), as several clinical cases have also been reported about post-influenza fibrotic sequelae(Gao et al., 2021; Mineo et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2023). IAV infection in vulnerable populations can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and result in pulmonary fibrosis(Nakajima et al., 2012). A long-term follow-up study reported that some patients who recovered from H1N1-induced ARDS developed pulmonary fibrosis at later stages, as also reported for COVID-19(Saha et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2023).

Our study has several strengths that make our findings robust. First, to avoid COVID-19-related confounding, we restricted the analysis to IAV diagnoses by including individuals who tested positive with an RNA or antigen test and excluding any patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis or positive test. Second, the study population we used is racially diverse and includes Caucasian, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, and others, representing a more diverse population than previous similar studies. Socioeconomic and structural determinants, geographical factors, and healthcare delivery may affect the care of patients with IAV and ARD; however, these factors were beyond the scope of this study. Given that our study population is representative of multiple centers across the United States, the results are more generalizable than results from single-center or regional experiences.

Our study has certain limitations. Almost 80% of the HCOs in TriNetX are American; therefore, the generalizability of our conclusions is limited to other countries. EHR-based data is susceptible to coding errors when patient information is translated into codes. Extensive data quality assessment, including data cleaning and quality checks, minimizes the risk of data collection errors at the investigator’s end. Although validated outcome definitions and propensity score matching were used to avoid bias and confounding, misclassification bias, residual confounding, and other inherent weaknesses in EHRs cannot be completely avoided.

We have reported that the pro-fibrotic factors PDIA3 and SPP1 promote the development of lung fibrosis. Whether these proteins participate in IAV-induced lung fibrosis was previously unknown. Studies have suggested that ER-based chaperones, including PDIA3 downstream of ER stress, play an important role in influenza pathogenesis(Kim & Chang, 2018; Roberson et al., 2012). (Aghaei et al., 2020; Kropski & Blackwell, 2018). Knockdown of PDIA3 led to reduced IAV burden, indicating that PDIA3 controls virus burden in the lung(Kim & Chang, 2018). Previous short-term studies (5–7 dpi) in our lab with PDIA3 suggested its roles in the formation of disulfide bonds of IAV proteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) and the subsequent establishment of infection, inflammation, and AHR(Chamberlain et al., 2019; Chamberlain et al., 2022). The current study extends the role of PDIA3 to IAV-induced lung fibrotic remodeling.

PDIA3 functions as a redox chaperone to support the proper folding and secretion of several growth factors(Hellewell et al., 2022). A recent study from our lab demonstrated that PDIA3 interacts with growth factor SPP1, enhances its production, and promotes lung fibrosis(Kumar et al., 2022). In the current paper, analysis of serum samples from humans infected with Influenza showed elevated levels of PDIA3 and SPP1 in IAV-infected patients compared to healthy controls. Like influenza patients, we also found a high level of PDIA3 and SPP1 in a mouse model of IAV infection. This PDIA3 and SPP1 upregulation promoted a significant increase of collagen in the lungs of infected mice that was significantly decreased after therapeutic administration of a PDIA3 inhibitor, punicalagin. Mechanistically, we observed a reduction in -S-S- bonds of SPP1 after punicalagin treatment in both mouse and cell culture models, and our experiments further showed that reduction in disulfide bonds resulted in decreased secretion, rather than decreased intracellular production, of SPP1. These results for the first time indicate mechanisms of a PDIA3-dependent SPP1 modification and production in cells.

SPP1 plays an important role in lung damage caused by influenza-induced pneumonia and implicates serum SPP1 levels as a marker of lung injury(Zhu et al., 2015). A few studies also suggested elevated SPP1 levels as a biomarker for acute exacerbation of IPF and as a predictor of survival in IPF patients(Gui et al., 2020; Pardo et al., 2005). Supporting the causative effects of SPP1 in pulmonary fibrotic remodeling, we have previously reported that neutralizing SPP1 attenuates bleomycin-induced murine lung fibrosis(Kumar et al., 2022).

Our results revealed a significant upregulation of SPP1 following IAV infection (15 dpi) and maintained until 60 dpi. At the same time, IAV-induced lung fibrosis was also sustained from 15 to 60 dpi compared to mock-infected mice. Our analysis showed that the IAV burden was high at 3 dpi and significantly decreased at 10 dpi. However, the SPP1 signature was high at 10–60 dpi, suggesting that SPP1 is induced following IAV infection and was maintained at a higher level even after the virus is cleared. This sustained high level of SPP1 promoted fibrosis, as using an antagonistic antibody for SPP1 decreased post-IAV fibrosis in mouse lungs. Our results also agree with several previous studies that showed a direct link between SPP1 production and the development of pulmonary fibrosis, and deletion or silencing of SPP1 resulted in attenuated pulmonary fibrosis(Berman et al., 2004; Hatipoglu et al., 2021; Oh et al., 2015).

Interestingly, our results showed that inhibition of SPP1 using the antagonistic antibody during early time points following IAV infection resulted in a significant decrease in lymphocytes but increased neutrophils in the lung. These results suggested that biphasic effects of SPP1 inhibition during/post-IAV infection, i.e., neutralizing SPP1 during infection, resulted in increased immunopathology, whereas neutralizing SPP1 at more protracted time points following IAV infection resulted in resolution of lung fibrosis.

In contrast, SPP1 systemic ablation decreases ALI in mice(Wang et al., 2022). However, in our short-term neutralization study, we observed increases in inflammatory indices. This could be because we used an antagonistic SPP1 antibody approach instead of systemic ablation of SPP1, as described previously(Wang et al., 2022). Our experimental regimen was also longer as we neutralized SPP1 compared to the earlier study that reported a decrease in ALI 24 hours following IAV infection in SPP1 systemically ablated mice(Wang et al., 2022).

Airway mechanics assessed by the methacholine challenge in our mice were significantly altered by IAV infection in agreement with other studies(Bozanich et al., 2008; Chamberlain et al., 2019). AHR is closely linked to airway inflammation, remodeling, and increased mucus secretion(Rubin et al., 2014), so it was not surprising that we found AHR up to 60 dpi. The parameters G and H were consistently elevated at 10, 15, and 21 dpi, characterizing the viscoelastic nature of the lung tissues, and are both elevated in inverse proportion to the amount of lungs that remain open after the small airways have become blocked as a result of excessive narrowing or mucus plugging(Wagers et al., 2004). The patterns of AHR we observed in our IAV-infected mice are thus compatible with the pathologic process that predominantly affects the lung parenchyma, as would be expected of lung fibrosis.

We have previously reported that increased PDIA3 is an important driver of allergen- or IAV-induced AHR(Chamberlain et al., 2019; Hoffman et al., 2016). Nevertheless, we found in the present study that neither inhibition of PDIA3 nor neutralizing SPP1 resulted in a significant attenuation of AHR. The likely explanation for these findings is that we measured AHR while remodeling changes to the parenchyma were still present. We speculate that these pharmacological treatments may require additional time to promote resolution.

We acknowledge some limitations in our study. The data retrieved from TriNetX are from patients’ whose follow-up was conducted at various health clinics. Therefore, we do not have other biological samples to test for the pro-fibrotic SPP1 or PDIA3 alterations in TrinetX cohorts. These patients were also followed up for one year; however, fibrotic-like changes require longer follow-up to determine whether the fibrosis is permanent, progressive, or reversible. The SPP1 and PDIA3 are measured in a different cohort, who are acutely infected with IAV, and samples were collected with in 2 days of diagnosis of influenza infection. This may not exactly represent the cohort of TrinetX. We believe that to understand and correlate the development of lung fibrosis and the role of PDIA3 and SPP1 in post-influenza infection in humans; a prospective clinical study is needed during several influenza seasons. Another limitation is that the synergistic impact of punicalagin and SPP1 treatment during IAV infection in mice was not confirmed. It will be an important future direction for our research. We did not perform detailed experiments to show which lung cell types express PDIA3 and SPP1 and how these cells contribute to IAV-induced fibrosis in mice. Future research is needed to explore the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which the SPP1- PDIA3 axis contributes to IAV-induced lung fibrosis.

While exploring the temporal changes in physiological parameters post-IAV infection, we observed that although SpO2 levels returned to normalcy in IAV-infected mice at 60 dpi, hydroxyproline, Masson’s trichrome, and AHR (Rn and G), measurements indicated a sustained (patchy) lung fibrosis, and increased airway/tissue resistance, suggesting that mechanical and structural alterations have not been fully resolved even at 60 dpi. Although, at present, there is no clear explanation for this occurance, we speculate that these parameters may persist for a longer time, and a decrease in SpO2 predictably occurs with strenuous exercises. This has been observed in humans with post-influenza or SARS-CoV-2 infection, where oxygen desaturation is observed with strenuous activities post-virus infection(Bai et al., 2011; Carlucci et al., 2023; Schafer et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2012).

We also observed that PUN-mediated PDIA3 inhibition at the early phase of IAV infection (3 to 12 dpi) was detrimental to mice. We speculate that PDIA3 inhibition at the early phase may inhibit antigen loading of MHC I, post-translational modifications of antibodies, and thrombosis(Chamberlain & Anathy, 2020; Stepensky et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2013). These processes are essential at the immediate time following IAV infection. Therefore, Inhibiting PDIA3 is predictably counterproductive in the early phase of infection.

Interestingly, we measured influenza-PA mRNA in early-phase treatment experiments with PUN as we could not clearly determine viral titers at 8 or 10 dpi in mice. Here, we found that PA mRNA was significantly high in infected mice treated with PUN (Figure S3 K). There may be an increased viral burden due to PDIA3 inhibition, which probably induced mortality in mice. However, we found that epithelial-specific deletion of PDIA3 or inhibition with another molecule (LOC14) decreased viral burden and AHR in 3–5 dpi(Chamberlain et al., 2019; Chamberlain et al., 2022). Compared to the current report, we believe this discrepancy can be attributed to epithelial (club cell) specific deletion of PDIA3, and LOC14 not considered as a potent inhibitor of PDIA3, and measurements carried out at acute time points.

The increases in PDIA3 and its continued presence are pro-fibrotic, as demonstrated in our earlier work(Kumar et al., 2022). Furthermore, PDIA3 is known to catalyze disulfide bonds in the pro-fibrotic proteins such as collagens, LOXL2, integrins, and fibronectin(Jessop et al., 2007; Jessop, Watkins, et al., 2009), therefore inhibiting PDIA3 14 dpi is beneficial and decreased fibrosis in our experiments.

SPP1 regulates chemotaxis and functions of various inflammatory and immune cells in a context-dependent manner(Kahles et al., 2014). Therefore, inhibiting SPP1 is harmful at the initial stage of viral infection(Lund et al., 2009). Although we observed increases in neutrophils and AHR in an early phase inhibition study (by anti-SPP1 antibody), blocking SPP1 did not alter the viral PA mRNA (Figure S4 E). However, SPP1 is known to be pro-fibrotic in models of fibrosis and human fibrotic conditions(Ouyang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

Recent studies in fibrosis have revealed that monocytes and alveolar macrophages are altered in fibrotic disorders(Perrot et al., 2023). Within this context, lung fibrosis-associated macrophages that are positive for CD14 or MERTK are also SPP1 high and thought to be associated with fibrosis progression(Morse et al., 2019; Perrot et al., 2023; Suga et al., 2000). Although our study did not elucidate the cell type responsible for SPP1 production, it provides evidence that SPP1 is pro-fibrotic post–influenza, and blocking SPP1 14–24 dpi is beneficial and decreases fibrosis.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

With the data presented here, we conclude that patients with IAV-ARD exhibited higher pulmonary fibrosis risk outcomes. The 12-month risk of pulmonary fibrosis was significantly higher in patients with IAV with ARD than in non-ARD IAV. The present study supports the hypothesis that increases in PDIA3 and its interacting pro-fibrotic growth factor SPP1 promote lung fibrosis post-IAV infection. Our findings also demonstrate that inhibition of PDIA3 or SPP1 significantly attenuates post-IAV lung fibrosis and improves physiological and biochemical parameters in mice, making the PDIA3/SPP1 axis a potential drug target in IAV-induced lung remodeling.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank excellent technical support from the University of Vermont Microscopy center and financial support from the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, the University of Vermont. The authors would like to thank the TriNetX (Cambridge, MA) healthcare network for design assistance in completing the analysis.

FUNDING

This work is supported by NIH R01s HL122383, HL141364, & HL136917 to VA; R35 HL135828 to YJ-H; 1UG3TR002612 to AGJ; R01 HL142081 and HL133920 to MEP. Imaging work was performed at the Microscopy Imaging Center at the University of Vermont (RRID# SCR_018821) and Leica-Aperio VERSA whole slide imaging system from College of Medicine Shared Instrumentation.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

Yvonne Janssen-Heininger (YJH), and Vikas Anathy (VA) hold patents: United States Patent No. 8,679,811, “Treatments Involving Glutaredoxins and Similar Agents”, United States Patent No. 8,877,447, “Detection of Glutathionylated Proteins”, United States Patent, 9,907,828 (to YJH), “Treatments of oxidative stress conditions” (YJH and VA). In the past YJH and VA have received consulting fees and laboratory contracts from Celdara Medical LLC, NH. AGJ serves as a member of Scientific Advisory Board of Gen1E Lifesciences, Palo Alto, CA, United States.

Amit Kumar and VA hold patent: United States Patent No. 11883395, “Methods and uses of protein disulfide isomerase inhibitory compounds.”

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data supporting the findings reported here are available from the TriNetX Analytics Network. https://trinetx.com.

REFERENCES

- Aghaei M, Dastghaib S, Aftabi S, Aghanoori MR, Alizadeh J, Mokarram P, Mehrbod P, Ashrafizadeh M, Zarrabi A, McAlinden KD, Eapen MS, Sohal SS, Sharma P, Zeki AA, & Ghavami S (2020). The ER Stress/UPR Axis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Life (Basel), 11(1). 10.3390/life11010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Gu L, Cao B, Zhai XL, Lu M, Lu Y, Liang LR, Zhang L, Gao ZF, Huang KW, Liu YM, Song SF, Wu L, Yin YD, & Wang C (2011). Clinical features of pneumonia caused by 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus in Beijing, China. Chest, 139(5), 1156–1164. 10.1378/chest.10-1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JS, Serlin D, Li X, Whitley G, Hayes J, Rishikof DC, Ricupero DA, Liaw L, Goetschkes M, & O’Regan AW (2004). Altered bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in osteopontin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 286(6), L1311–1318. 10.1152/ajplung.00394.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocci V, Zanardi I, & Travagli V (2011). Ozone: a new therapeutic agent in vascular diseases. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs, 11(2), 73–82. 10.2165/11539890-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozanich EM, Gualano RC, Zosky GR, Larcombe AN, Turner DJ, Hantos Z, & Sly PD (2008). Acute Influenza A infection induces bronchial hyper-responsiveness in mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol, 162(3), 190–196. 10.1016/j.resp.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caorsi C, Niccolai E, Capello M, Vallone R, Chattaragada MS, Alushi B, Castiglione A, Ciccone G, Mautino A, Cassoni P, De Monte L, Alvarez-Fernandez SM, Amedei A, Alessio M, & Novelli F (2016). Protein disulfide isomerase A3-specific Th1 effector cells infiltrate colon cancer tissue of patients with circulating anti-protein disulfide isomerase A3 autoantibodies. Transl Res, 171, 17–28 e11–12. 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci A, Paneroni M, Carotenuto M, Bertella E, Cirio S, Gandolfo A, Simonelli C, Vigna M, Lastoria C, Malovini A, Fusar Poli B, & Vitacca M (2023). Prevalence of exercise-induced oxygen desaturation after recovery from SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and use of lung ultrasound to predict need for pulmonary rehabilitation. Pulmonology, 29 Suppl 4, S4–S8. 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2021.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain N, & Anathy V (2020). Pathological consequences of the unfolded protein response and downstream protein disulphide isomerases in pulmonary viral infection and disease. J Biochem, 167(2), 173–184. 10.1093/jb/mvz101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain N, Korwin-Mihavics BR, Nakada EM, Bruno SR, Heppner DE, Chapman DG, Hoffman SM, van der Vliet A, Suratt BT, Dienz O, Alcorn JF, & Anathy V (2019). Lung epithelial protein disulfide isomerase A3 (PDIA3) plays an important role in influenza infection, inflammation, and airway mechanics. Redox Biol, 22, 101129. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain N, Ruban M, Mark ZF, Bruno SR, Kumar A, Chandrasekaran R, Souza De Lima D, Antos D, Nakada EM, Alcorn JF, & Anathy V (2022). Protein Disulfide Isomerase A3 Regulates Influenza Neuraminidase Activity and Influenza Burden in the Lung. Int J Mol Sci, 23(3). 10.3390/ijms23031078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran R, Bruno SR, Mark ZF, Walzer J, Caffry S, Gold C, Kumar A, Chamberlain N, Butzirus IM, Morris CR, Daphtary N, Aliyeva M, Lam YW, van der Vliet A, Janssen-Heininger Y, Poynter ME, Dixon AE, & Anathy V (2023). Mitoquinone mesylate attenuates pathological features of lean and obese allergic asthma in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 324(2), L141–L153. 10.1152/ajplung.00249.2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran R, Morris CR, Butzirus IM, Mark ZF, Kumar A, Souza De Lima D, Daphtary N, Aliyeva M, Poynter ME, Anathy V, & Dixon AE (2023). Obesity exacerbates influenza-induced respiratory disease via the arachidonic acid-p38 MAPK pathway. Front Pharmacol, 14, 1248873. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1248873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YJ, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, Dekruyff RH, & Umetsu DT (2011). Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol, 12(7), 631–638. 10.1038/ni.2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Olivares-Navarrete R, Wang Y, Herman TR, Boyan BD, & Schwartz Z (2010). Protein-disulfide isomerase-associated 3 (Pdia3) mediates the membrane response to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem, 285(47), 37041–37050. 10.1074/jbc.M110.157115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolla EM, Huckestein BR, & Alcorn JF (2020). Influenza sequelae: from immune modulation to persistent alveolitis. Clin Sci (Lond), 134(13), 1697–1714. 10.1042/CS20200050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agnillo F, Walters KA, Xiao Y, Sheng ZM, Scherler K, Park J, Gygli S, Rosas LA, Sadtler K, Kalish H, Blatti CA 3rd, Zhu R, Gatzke L, Bushell C, Memoli MJ, O’Day SJ, Fischer TD, Hammond TC, Lee RC, . . . Taubenberger JK (2021). Lung epithelial and endothelial damage, loss of tissue repair, inhibition of fibrinolysis, and cellular senescence in fatal COVID-19. Sci Transl Med, 13(620), eabj7790. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj7790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari DM, & Soling HD (1999). The protein disulphide-isomerase family: unravelling a string of folds. Biochem J, 339 ( Pt 1)(Pt 1), 1–10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10085220 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galani IE, Triantafyllia V, Eleminiadou EE, & Andreakos E (2022). Protocol for influenza A virus infection of mice and viral load determination. STAR Protoc, 3(1), 101151. 10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Chu W, Duan J, Li J, Ma W, Hu C, Yao M, Xing L, & Yang Y (2021). Six-Month Outcomes of Post-ARDS Pulmonary Fibrosis in Patients With H1N1 Pneumonia. Front Mol Biosci, 8, 640763. 10.3389/fmolb.2021.640763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germon A, Heesom KJ, Amoah R, & Adams JC (2023). Protein disulfide isomerase A3 activity promotes extracellular accumulation of proteins relevant to basal breast cancer outcomes in human MDA-MB-A231 breast cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 324(1), C113–C132. 10.1152/ajpcell.00445.2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamogante F, Marrocco I, Cervoni L, Eufemi M, Chichiarelli S, & Altieri F (2018). Punicalagin, an active pomegranate component, is a new inhibitor of PDIA3 reductase activity. Biochimie, 147, 122–129. 10.1016/j.biochi.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui X, Qiu X, Xie M, Tian Y, Min C, Huang M, Hongyan W, Chen T, Zhang X, Chen J, Cao M, & Cai H (2020). Prognostic Value of Serum Osteopontin in Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biomed Res Int, 2020, 3424208. 10.1155/2020/3424208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Fan Y, Alwalid O, Li N, Jia X, Yuan M, Li Y, Cao Y, Gu J, Wu H, & Shi H (2021). Six-month Follow-up Chest CT Findings after Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia. Radiology, 299(1), E177–E186. 10.1148/radiol.2021203153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms PW, Schmidt LA, Smith LB, Newton DW, Pletneva MA, Walters LL, Tomlins SA, Fisher-Hubbard A, Napolitano LM, Park PK, Blaivas M, Fantone J, Myers JL, & Jentzen JM (2010). Autopsy findings in eight patients with fatal H1N1 influenza. Am J Clin Pathol, 134(1), 27–35. 10.1309/AJCP35KOZSAVNQZW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatipoglu OF, Uctepe E, Opoku G, Wake H, Ikemura K, Ohtsuki T, Inagaki J, Gunduz M, Gunduz E, Watanabe S, Nishinaka T, Takahashi H, & Hirohata S (2021). Osteopontin silencing attenuates bleomycin-induced murine pulmonary fibrosis by regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biomed Pharmacother, 139, 111633. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellewell AL, Heesom KJ, Jepson MA, & Adams JC (2022). PDIA3/ERp57 promotes a matrix-rich secretome that stimulates fibroblast adhesion through CCN2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 322(4), C624–C644. 10.1152/ajpcell.00258.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman SM, Chapman DG, Lahue KG, Cahoon JM, Rattu GK, Daphtary N, Aliyeva M, Fortner KA, Erzurum SC, Comhair SA, Woodruff PG, Bhakta N, Dixon AE, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YM, Poynter ME, & Anathy V (2016). Protein disulfide isomerase-endoplasmic reticulum resident protein 57 regulates allergen-induced airways inflammation, fibrosis, and hyperresponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 137(3), 822–832 e827. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Goplen NP, Zhu B, Cheon IS, Son Y, Wang Z, Li C, Dai Q, Jiang L, Xiang M, Carmona EM, Vassallo R, Limper AH, & Sun J (2019). Macrophage PPAR-gamma suppresses long-term lung fibrotic sequelae following acute influenza infection. PLoS One, 14(10), e0223430. 10.1371/journal.pone.0223430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WJ, & Tang XX (2021). Virus infection induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Transl Med, 19(1), 496. 10.1186/s12967-021-03159-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop CE, Chakravarthi S, Garbi N, Hammerling GJ, Lovell S, & Bulleid NJ (2007). ERp57 is essential for efficient folding of glycoproteins sharing common structural domains. EMBO J, 26(1), 28–40. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop CE, Tavender TJ, Watkins RH, Chambers JE, & Bulleid NJ (2009). Substrate specificity of the oxidoreductase ERp57 is determined primarily by its interaction with calnexin and calreticulin. J Biol Chem, 284(4), 2194–2202. 10.1074/jbc.M808054200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop CE, Watkins RH, Simmons JJ, Tasab M, & Bulleid NJ (2009). Protein disulphide isomerase family members show distinct substrate specificity: P5 is targeted to BiP client proteins. J Cell Sci, 122(Pt 23), 4287–4295. 10.1242/jcs.059154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahles F, Findeisen HM, & Bruemmer D (2014). Osteopontin: A novel regulator at the cross roads of inflammation, obesity and diabetes. Mol Metab, 3(4), 384–393. 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Han JS, & O’Malley KL (2007). Cell stress induced by the parkinsonian mimetic, 6-hydroxydopamine, is concurrent with oxidation of the chaperone, ERp57, and aggresome formation. Antioxid Redox Signal, 9(12), 2255–2264. 10.1089/ars.2007.1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, & Chang KO (2018). Protein disulfide isomerases as potential therapeutic targets for influenza A and B viruses. Virus Res, 247, 26–33. 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropski JA, & Blackwell TS (2018). Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disease. J Clin Invest, 128(1), 64–73. 10.1172/JCI93560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Elko E, Bruno SR, Mark ZF, Chamberlain N, Mihavics BK, Chandrasekaran R, Walzer J, Ruban M, Gold C, Lam YW, Ghandikota S, Jegga AG, Gomez JL, Janssen-Heininger YM, & Anathy V (2022). Inhibition of PDIA3 in club cells attenuates osteopontin production and lung fibrosis. Thorax, 77(7), 669–678. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-216882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SW, Sharma L, Kang YA, Kim SH, Chandrasekharan S, Losier A, Brady V, Bermejo S, Andrews N, Yoon CM, Liu W, Lee JY, Kang MJ, & Dela Cruz CS (2018). Impact of Cigarette Smoke Exposure on the Lung Fibroblastic Response after Influenza Pneumonia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 59(6), 770–781. 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0004OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenfant C (2000). Lung Surfactants, Basic Science and Clinical Applications. [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Su DJ, Zhang JF, Xia XD, Sui H, & Zhao DH (2011). Pneumonia in novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus infection: high-resolution CT findings. Eur J Radiol, 80(2), e146–152. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund SA, Giachelli CM, & Scatena M (2009). The role of osteopontin in inflammatory processes. J Cell Commun Signal, 3(3–4), 311–322. 10.1007/s12079-009-0068-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineo G, Ciccarese F, Modolon C, Landini MP, Valentino M, & Zompatori M (2012). Post-ARDS pulmonary fibrosis in patients with H1N1 pneumonia: role of follow-up CT. Radiol Med, 117(2), 185–200. 10.1007/s11547-011-0740-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizwicki MT, Liu G, Fiala M, Magpantay L, Sayre J, Siani A, Mahanian M, Weitzman R, Hayden EY, Rosenthal MJ, Nemere I, Ringman J, & Teplow DB (2013). 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and resolvin D1 retune the balance between amyloid-beta phagocytosis and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis, 34(1), 155–170. 10.3233/JAD-121735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse C, Tabib T, Sembrat J, Buschur KL, Bittar HT, Valenzi E, Jiang Y, Kass DJ, Gibson K, Chen W, Mora A, Benos PV, Rojas M, & Lafyatis R (2019). Proliferating SPP1/MERTK-expressing macrophages in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J, 54(2). 10.1183/13993003.02441-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougel A, Adriaenssens E, Guyot B, Tian L, Gobert S, Chassat T, Persoons P, Hannebique D, Bauderlique-Le Roy H, Vicogne J, Le Bourhis X, & Bourette RP (2022). Macrophage-Colony-Stimulating Factor Receptor Enhances Prostate Cancer Cell Growth and Aggressiveness In Vitro and In Vivo and Increases Osteopontin Expression. Int J Mol Sci, 23(24). 10.3390/ijms232416028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima N, Sato Y, Katano H, Hasegawa H, Kumasaka T, Hata S, Tanaka S, Amano T, Kasai T, Chong JM, Iizuka T, Nakazato I, Hino Y, Hamamatsu A, Horiguchi H, Tanaka T, Hasegawa A, Kanaya Y, Oku R, . . . Sata T (2012). Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings of 20 autopsy cases with 2009 H1N1 virus infection. Mod Pathol, 25(1), 1–13. 10.1038/modpathol.2011.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS, Ahluwalia N, Bikdeli B, Dietz D, Der-Nigoghossian C, Liyanage-Don N, Rosner GF, Bernstein EJ, Mohan S, Beckley AA, . . . Wan EY (2021). Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med, 27(4), 601–615. 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh K, Seo MW, Kim YW, & Lee DS (2015). Osteopontin Potentiates Pulmonary Inflammation and Fibrosis by Modulating IL-17/IFN-gamma-secreting T-cell Ratios in Bleomycin-treated Mice. Immune Netw, 15(3), 142–149. 10.4110/in.2015.15.3.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang JF, Mishra K, Xie Y, Park H, Huang KY, Petretto E, & Behmoaras J (2023). Systems level identification of a matrisome-associated macrophage polarisation state in multi-organ fibrosis. Elife, 12. 10.7554/eLife.85530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paglia G, Antonini L, Cervoni L, Ragno R, Sabatino M, Minacori M, Rubini E, & Altieri F (2021). A Comparative Analysis of Punicalagin Interaction with PDIA1 and PDIA3 by Biochemical and Computational Approaches. Biomedicines, 9(11). 10.3390/biomedicines9111533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo A, Gibson K, Cisneros J, Richards TJ, Yang Y, Becerril C, Yousem S, Herrera I, Ruiz V, Selman M, & Kaminski N (2005). Up-regulation and profibrotic role of osteopontin in human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Med, 2(9), e251. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrot CY, Karampitsakos T, & Herazo-Maya JD (2023). Monocytes and macrophages: emerging mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 325(4), C1046–C1057. 10.1152/ajpcell.00302.2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley FJ, & Stanley ER (2004). CSF-1 regulation of the wandering macrophage: complexity in action. Trends Cell Biol, 14(11), 628–638. 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson EC, Tully JE, Guala AS, Reiss JN, Godburn KE, Pociask DA, Alcorn JF, Riches DW, Dienz O, Janssen-Heininger YM, & Anathy V (2012). Influenza induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, caspase-12-dependent apoptosis, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated transforming growth factor-beta release in lung epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 46(5), 573–581. 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0460OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin BK, Priftis KN, Schmidt HJ, & Henke MO (2014). Secretory hyperresponsiveness and pulmonary mucus hypersecretion. Chest, 146(2), 496–507. 10.1378/chest.13-2609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Vaidya PJ, Chavhan VB, Achlerkar A, Leuppi JD, & Chhajed PN (2018). Combined pirfenidone, azithromycin and prednisolone in post-H1N1 ARDS pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis, 35(1), 85–90. 10.36141/svdld.v35i1.6393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer H, Teschler M, Mooren FC, & Schmitz B (2023). Altered tissue oxygenation in patients with post COVID-19 syndrome. Microvasc Res, 148, 104551. 10.1016/j.mvr.2023.104551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V, Sharma BB, & Patel V (2012). Pulmonary sequelae in a patient recovered from swine flu. Lung India, 29(3), 277–279. 10.4103/0970-2113.99118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepensky D, Bangia N, & Cresswell P (2007). Aggregate formation by ERp57-deficient MHC class I peptide-loading complexes. Traffic, 8(11), 1530–1542. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterk PJ (1993). Virus-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in man. Eur Respir J, 6(6), 894–902. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8393410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M, Iyonaga K, Okamoto T, Gushima Y, Miyakawa H, Akaike T, & Ando M (2000). Characteristic elevation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 162(5), 1949–1956. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.9906096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi F, Takahashi K, Maeda K, Tominaga S, & Fukuchi Y (2000). Osteopontin is induced by nitric oxide in RAW 264.7 cells. IUBMB Life, 49(3), 217–221. 10.1080/713803614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z, Xia Z, Wang X, & Liu Y (2023). The critical role of osteopontin (OPN) in fibrotic diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 74, 86–99. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2023.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente T, Lassandro F, Marino M, Squillante F, Aliperta M, & Muto R (2012). H1N1 pneumonia: our experience in 50 patients with a severe clinical course of novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus (S-OIV). Radiol Med, 117(2), 165–184. 10.1007/s11547-011-0734-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagers S, Lundblad LK, Ekman M, Irvin CG, & Bates JH (2004). The allergic mouse model of asthma: normal smooth muscle in an abnormal lung? J Appl Physiol (1985), 96(6), 2019–2027. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00924.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Li X, Wang Y, Li Y, Shi F, & Diao H (2022). Osteopontin aggravates acute lung injury in influenza virus infection by promoting macrophages necroptosis. Cell Death Discov, 8(1), 97. 10.1038/s41420-022-00904-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wu Y, Zhou J, Ahmad SS, Mutus B, Garbi N, Hammerling G, Liu J, & Essex DW (2013). Platelet-derived ERp57 mediates platelet incorporation into a growing thrombus by regulation of the alphaIIbbeta3 integrin. Blood, 122(22), 3642–3650. 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wang S, Goplen NP, Li C, Cheon IS, Dai Q, Huang S, Shan J, Ma C, Ye Z, Xiang M, Limper AH, Porquera EC, Kohlmeier JE, Kaplan MH, Zhang N, Johnson AJ, Vassallo R, & Sun J (2019). PD-1(hi) CD8(+) resident memory T cells balance immunity and fibrotic sequelae. Sci Immunol, 4(36). 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Choi T, & Al-Aly Z (2023). Long-term outcomes following hospital admission for COVID-19 versus seasonal influenza: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00684-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Guan Q, Tian Y, Shao X, Zhao P, Huang L, & Li J (2023). Integrated bioinformatics analysis for the identification of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-related genes and potential therapeutic drugs. BMC Pulm Med, 23(1), 373. 10.1186/s12890-023-02678-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao AY, Unterman A, Abu Hussein N, Sharma P, Flint J, Yan X, Adams TS, Justet A, Sumida TS, Zhao J, Schupp JC, Raredon MSB, Ahangari F, Zhang Y, Buendia-Roldan I, Adegunsoye A, Sperling AI, Prasse A, Ryu C, . . . Kaminski N (2023). Peripheral Blood Single-Cell Sequencing Uncovers Common and Specific Immune Aberrations in Fibrotic Lung Diseases. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2023.09.20.558301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Wei Y, Chen J, Cui G, Ding Y, Kohanawa M, Xu X, & Diao H (2015). Osteopontin Exacerbates Pulmonary Damage in Influenza-Induced Lung Injury. Jpn J Infect Dis, 68(6), 467–473. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2014.467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings reported here are available from the TriNetX Analytics Network. https://trinetx.com.