Abstract

The membrane-bound hyaluronan synthase (HAS) from Streptococcus equisimilis (seHAS), which is the smallest Class I HAS, has four cysteine residues (positions 226, 262, 281, and 367) that are generally conserved within this family. Although Cys-null seHAS is still active, chemical modification of cysteine residues causes inhibition of wildtype enzyme (Kumari et al., J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13943, 2002). Here we studied the effects of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) treatment on a panel of seHAS Cys-mutants to examine the structural and functional roles of the four cysteine residues in the activity of the enzyme. We found that Cys226, Cys262, and Cys281 are reactive with NEM, but that Cys367 is not. Substrate protection studies of wildtype seHAS and a variety of Cys-mutants revealed that binding of UDP-GlcUA, UDP-GlcNAc or UDP can protect Cys226 and Cys262 from NEM inhibition. Inhibition of the six double Cys-mutants of seHAS by sodium arsenite, which can crosslink vicinyl sulfhydryl groups, also supported the conclusion that Cys262 and Cys281 are close enough to be crosslinked. Similar results indicated that Cys281 and Cys367 are also very close in the active enzyme. We conclude that three of the four Cys residues in seHAS (Cys262, Cys281, and Cys367 ) are clustered very close together, that these Cys residues and Cys226 are located at the inner surface of the cell membrane, and that Cys226 and Cys262 are located in or near a UDP binding site.

Keywords: Sulfhydryl reagents, N-ethylmaleimide, enzyme inhibition, Cysteine modification, site directed mutagenesis

Abbreviations: DTE, dithioerythritol; HA, hyaluronan or hyaluronic acid; HAS, HA synthase; NEM, N-ethylmaleimide; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; seHAS, Streptococcus equisimilis HAS; spHAS, Streptococcus pyogenes HAS

Hyaluronan synthase (HAS) is a membrane-bound enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of hyaluronan (HA) in both eukaryotes (Itano, et al. 2002) and prokaryotes (Weigel, 2002). HA is a linear glycosaminoglycan composed of the repeating hetero-disaccharide unit: GlcUAß(1,3)GlcNAcß (1,4). HA is a component of extracellular matrices in all vertebrates, and is present in large amounts for special functions in cartilage, synovial fluid, dermis and the vitreous humor of eye (Abatangelo and Weigel, 2000). This glycosaminoglycan plays critical roles during fertilization, embryogenesis, development and differentiation (Laurent and Fraser, 1992; Toole, 1997; Knudson and Knudson, 1993, Fenderson et al., 1993). In Group A and Group C streptococcal strains, HA forms a capsule that helps these cells evade the host immune system during infection (Kass and Seastone, 1944; Wessels et al. 1994). Progress in understanding the molecular basis for HA biosynthesis accelerated greatly after 1993, when the Streptococcus pyogenes HAS (spHAS) gene was first cloned (DeAngelis et al., 1993). Other members of the HAS family were subsequently identified from mammalian, avian and amphibian species (DeAngelis et al., 1997, 1998; Fulop et al. 1997; Itano et al., 1996; Shyjan et al. 1996; Spicer et al., 1996, Spicer and McDonald, 1998; Watanabe et al. 1996), and also from Group C Streptococcus equisimilis (seHAS) and Streptococcus uberis (Kumari and Weigel, 1997; Ward et al., 2001). The HAS proteins are organized into two groups. The Class I enzymes contain all but one reported HAS; the single Class II enzyme (from Pasteurella multocida) differs from all other HASs in its structure and mechanism of HA biosynthesis (DeAngelis, 1999). The Class I HASs from prokaryotes and vertebrates are ~30% identical, and share a common membrane topology (Weigel et al., 1997; Heldermon et al., 2001).

Although Class I HASs function as glycosyltransferases, they are very different from the vast majority of glycosyltransferases in that their UDP-sugar substrates are acceptors rather than donors (Robbins et al., 1967), because sugar addition occurs at the reducing end of growing HA chains (Prehm, 1983; Asplund et al., 1998; Tlapak-Simmons and Weigel, 2002). The growing HA chain remains bound to the enzyme at the cell membrane, while it is extruded into the extracellular space, and then ultimately shed into the extracellular space or assembled into a pericellular coat around eukaryotic cells or a capsule around bacterial cells. Therefore, despite their relatively small sizes (e.g. seHAS is ~49 kDa), HASs perform multiple discrete functions in order to synthesize HA (Tlapak-Simmons et al., 1999b; Weigel 2002). Radiation inactivation studies demonstrated that the streptococcal (Tlapak-Simmons et al., 1998) and amphibian (Pummill et al., 2001) Class I HASs function as protein monomers, but require phospholipids for activity, probably in both cases. Cardiolipin, phosphatidylserine or phosphatidic acid activate purified spHAS and seHAS, whereas other lipids do not activate these enzymes (Tlapak-Simmons et al., 1999a). The activating lipids for the eukaryotic HASs have not yet been identified.

The recombinant streptococcal enzymes have been purified, characterized kinetically, and studied more extensively than other Class I HASs (Tlapak-Simmons et al., 1999a; Tlapak-Simmons et al., 1999b; Tlapak-Simmons et al., 2004). Yoshida et al. 2000 purified and kinetically characterized recombinant mouse HAS1, but no other eukaryotic Class I enzyme has been purified. All the vertebrate and prokaryote recombinant Class I HASs synthesize high molecular mass HA, although the three mammalian isozymes produce HA of different size distributions (Itano et al., 1999; Brinck and Heldin, 1999; Koprunner et al., 2000). Generally, cells expressing HAS1 or HAS3 synthesize and secrete HA of molecular mass <2 MDa, whereas cells expressing HAS2 produce HA of molecular mass >2 MDa.

We are using seHAS as a model enzyme to study structure-function relationships within the Class I HAS family. The eukaryotic HASs contain about 14 Cys residues, whereas seHAS has only four, and these latter Cys residues are generally conserved among the vertebrate HASs. Since investigators have known for many decades (Markovitz et al., 1959) that HASs are sensitive to oxidation, we recently investigated whether one or more of the conserved Cys residues is vital for seHAS function. Surprisingly, although Cys modification inhibits HAS activity, the Cys-null mutants of seHAS and spHAS are active (Heldermon et al., 2001; Kumari et al., 2002). Also, these enzymes do not contain disulfide bonds. The present study examined the structural and functional roles of the four cysteines in seHAS, using combinations of site directed mutagenesis, chemical modification and substrate protection studies. The results were previously reported in preliminary form (Kumari et al., 1999).

Results

NEM inhibition of single Cys-to-Ala and Cys-to-Ser seHAS mutants

We recently reported that wildtype seHAS and spHAS are inhibited by a variety of sulfhydryl reagents, even though the Cys-null mutants are active (Heldermon et al., 2001; Kumari et al., 2002). The kinetics of NEM inhibition for both wildtype seHAS and spHAS were complex, indicating that enzyme activity is probably very sensitive to the modification of some Cys residues and less sensitive to the modification of others. To explore the role of particular Cys residues in the inhibition of seHAS by sulfhydryl regents, we examined the kinetics of NEM inhibition in a complete panel of seHAS Cys-mutants. NEM treatment of the four single Cys-to-Ala (Fig.1) and Cys-to-Ser seHAS (Fig. 2) mutants caused variable degrees of inhibition. The kinetics and extent of inhibition of particular single Cys-mutants by NEM were similar to, more sensitive than, or less sensitive than wildtype. None of the single Cys-mutants of seHAS was completely insensitive to NEM, which indicates that inhibition is not due to modification of a single Cys residue.

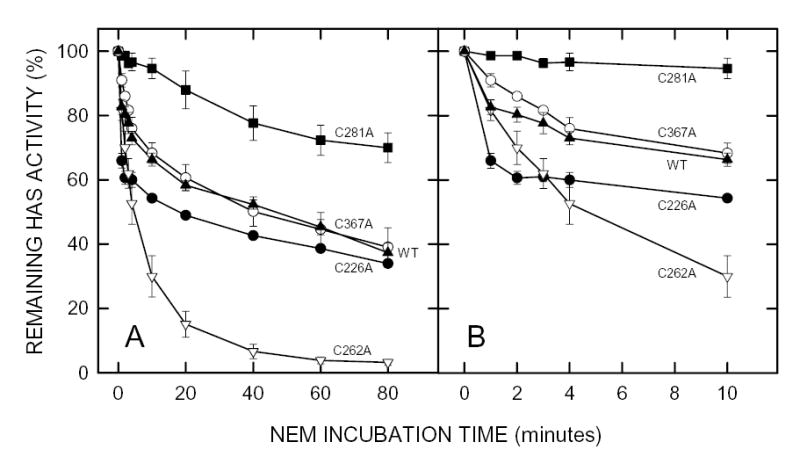

Figure 1. Effect of NEM on the activity of seHAS single Cys-to-Ala mutants.

Membranes containing wildtype seHAS (▴), or the C226A (•), C262A (▿), C281A (▪) or C367A (○) single Cys-mutants of seHAS were treated with 5 mM NEM at 4°C and the HAS activity of samples was determined at the indicated times as described in Methods. Panel B is a blowup of the early incubation times shown in Panel A. Results are the mean ± SEM for three separate experiments using different membrane preparations (n=3).

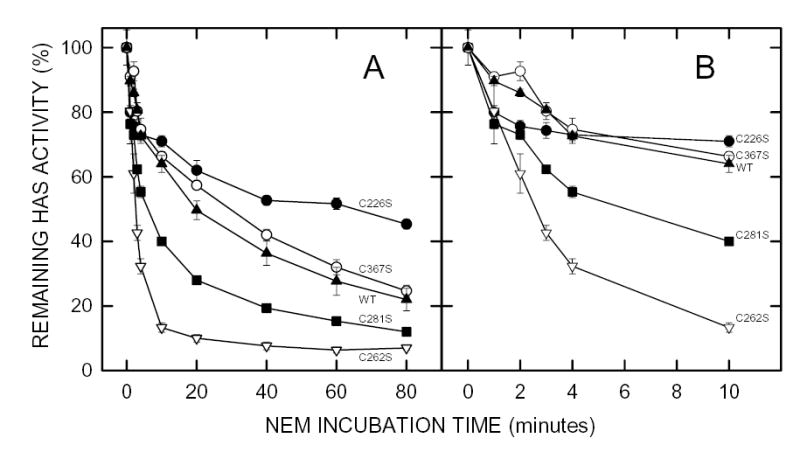

Figure 2. Effect of NEM on the activity of seHAS single Cys-to-Ser mutants.

Membranes containing wildtype seHAS (▴), or the C226S (•), C262S (▿), C281S (▪) or C367S (○) single Cys-mutants of seHAS were treated with 5 mM NEM at 4°C and the HAS activity of samples was determined at the indicated times as described in Methods. Panel B is a blowup of the early incubation times shown in Panel A. Results are the mean ± SEM for three separate experiments using different membrane preparations (n=3).

The C367A or C367S and C226A or C226S mutant pairs were similar to wildtype in both their initial rates (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2B) and their final extents (Fig. 1A and Fig. 2A) of inhibition. The C262A and C262S mutants were inhibited at a greater rate and to a greater extent (>95%) than wildtype enzyme. The C281A mutant was the least sensitive to NEM inhibition, being only ~5% inhibited during the first 10 min (Fig. 1B), but was then slowly inhibited by ~30% over 80 min (Fig. 1A). In contrast, seHAS(C281S) was significantly more sensitive to NEM than the C281A mutant or wildtype. One possible explanation for these varied results is that more than one modified Cys residue can be responsible for substantial seHAS inactivation and the order or extent of Cys modification likely determines the residual seHAS activity. The loss of rapid inactivation in seHAS(C281A) indicates that modification of Cys281 greatly affects the accessibility or reactivity of NEM with other Cys residues. The different behavior of seHAS(C281S) suggests that enhanced modification at another Cys residue occurred, causing greater inhibition of activity. This result could be due to the ability of Ser to engage in an altered H-bond or to the less hydrophobic nature of Ser compared to Cys. Changing Cys262 to either Ala or Ser greatly enhanced activity loss, suggesting that NEM modification of Cys262 slows the further kinetics of inhibition (i.e. modification of Cys262 hinders further modification of other Cys residues responsible for a more rapid activity loss).

NEM inhibition of double seHAS Cys-mutants

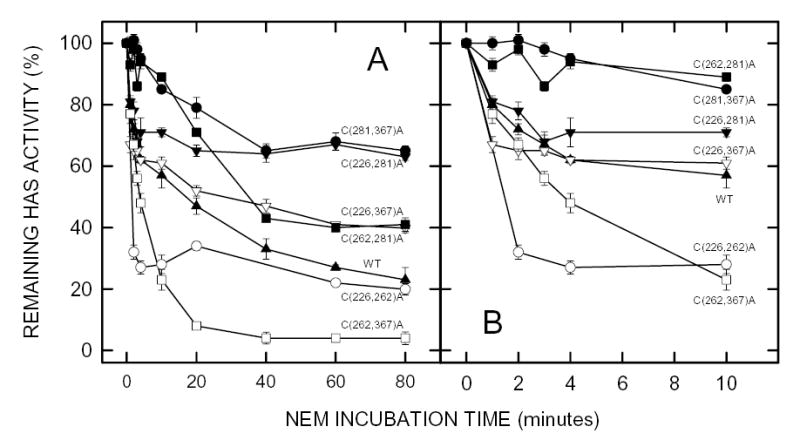

Since it seemed likely that more than one Cys was reactive with NEM, the six possible Cys-to-Ala seHAS double mutants were examined for their sensitivity to NEM. If two specific Cys residues were modified, resulting in activity loss, then some of the double mutants should be NEM insensitive. Surprisingly, none of the double mutants were completely resistant to NEM inhibition (Fig. 3A and 3B). The least sensitive seHAS mutants, C(226,281)A and C(281,367)A, were inhibited to a final extent of ~37% and 35%, respectively. Mutant C(262,281)A showed almost no rapid activity loss, but still showed a significant slow rate of inactivation. The C(226,262)A and C(262,367)A mutants were more sensitive to NEM than wildtype, showing a very rapid inactivation and indicating that Cys281 in these seHAS mutants was readily accessible to react with NEM. The C(262,367)A double mutant was also more sensitive to NEM inactivation, losing >96% of its activity.

Figure 3. Effect of NEM on the activity of seHAS double Cys-to-Ala mutants.

Membranes containing wildtype seHAS (▴), or the 226,262 (○), 226,281 (▾), 226,367 (▿), 262,281 (▪), 262,367 (□) or 281,367 (•) double Cys-to-Ala mutants of seHAS were treated with 5 mM NEM at 4°C and the HAS activity of samples was determined at the indicated times as described in Methods. Panel B is a blowup of the early incubation times shown in Panel A. Results are the mean ± SEM for three separate experiments (n=3).

The inhibition kinetics of the six double Cys-mutants were complex, but fell roughly into four groups. (i) Mutant C(226,367)A behaved most similarly to wildtype enzyme. (ii) Two of the mutants in which Cys281 was unaltered, C(226,262)A and C(262,367)A, showed enhanced rapid inactivation compared to wildtype. Mutant C(262,367)A also showed the greatest total activity loss. (iii) Mutant C(226,281)A retained a normal rapid inactivation, but then was not inactivated further compared to wildtype. Mutant C(281,367)A was partially inactivated to the same extent, but more slowly. (iv) Mutant C(262,281)A was also only slowly inactivated, but the final level of inactivation was greater than the group iii mutants, and more similar to wildtype. These double Cys-mutant data are consistent with the conclusion that modification of Cys262 results in the greatest inhibition of seHAS.

NEM inhibition of triple seHAS Cys-mutants

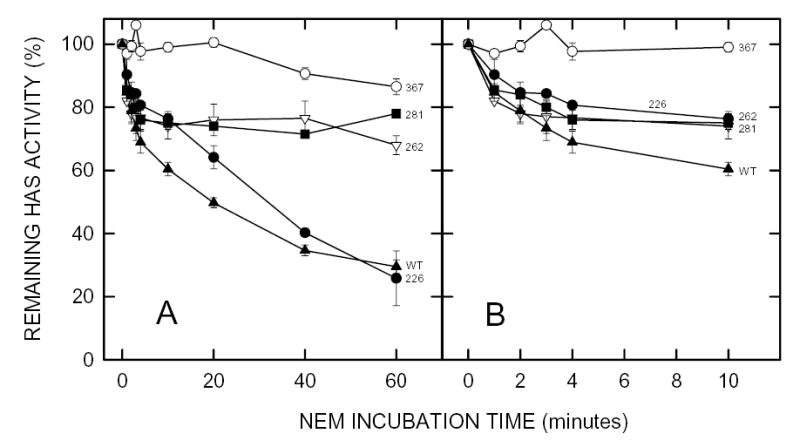

Previous studies demonstrated, as expected, that NEM treatment of Cys-null seHAS has no affect on enzyme activity, and does not modify the protein (Kumari et al., 2002). To determine if any of the four Cys residues might not contribute to the NEM-sensitivity of seHAS, we examined the NEM inhibition of the four triple Cys-mutants (Fig. 4), each of which contains one free Cys residue. Three of these Cys-mutants showed initial rates of inactivation that were similar to wildtype enzyme, whereas the seHAS(Δ3C)C367 mutant was unaffected by NEM treatment (Fig. 4B). The seHAS(Δ3C)262 and seHAS(Δ3C)C281 mutants were inhibited ~25% by NEM during the first 10 min of NEM treatment, but then no further inhibition of activity occurred. In contrast, seHAS(Δ3C)226 also showed a slower activity loss characteristic of wildtype seHAS, which continued to decrease to ~70% inhibition at 60 min (Fig. 4A). The results indicate that Cys281, Cys226, and Cys262 are accessible to react with NEM, that their resulting modification causes inhibition of seHAS activity, and that modification of Cys226 causes the greatest inhibition.

Figure 4. Effect of NEM on the activity of seHAS triple Cys-to-Ala mutants.

Membranes containing wildtype seHAS (▴), or the (3ΔC)C226 (•), (3ΔC)C262 (▿), (3ΔC)C281 (▪), or (3ΔC)C367 (○) triple Cys-mutants of seHAS were treated with 5 mM NEM at 4°C and the HAS activity of samples was determined at the indicated times as described in Methods. Panel B is a blowup of the early incubation times shown in Panel A. Results are the mean ± SEM for three separate experiments (n=3).

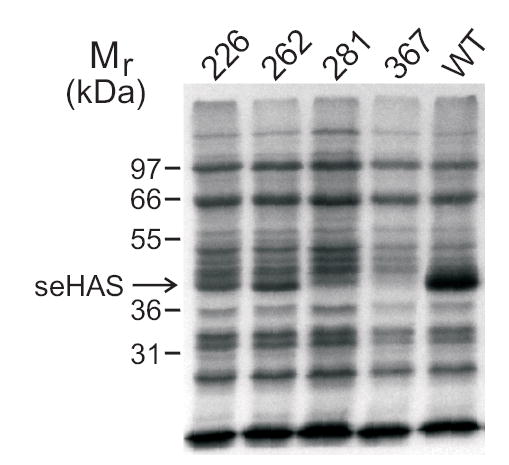

The lack of affect by NEM treatment on the seHAS(Δ3C)C367 mutant could mean that either Cys367 does not react with NEM or modification of this residue by NEM does not alter HAS activity. This issue was examined by treating membranes containing the four triple Cys-mutants with [14C]NEM. Since recombinant seHAS is up to ~10% of the total membrane protein and appears in a region of the gel with little background from endogenous proteins (Kumari et al., 2002), we could monitor the radiolabeling of seHAS by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography of treated membranes (Fig. 5). The results showed that Cys367 was not accessible to NEM, whereas Cys281, Cys226, and Cys262 in the three other triple seHAS Cys-mutants were readily labeled with [14C]NEM. We conclude from studies of the triple Cys-mutants that modification of Cys281, Cys226, or Cys262 results in decreased enzyme activity, and that seHAS function in this series of mutants is more sensitive to modification of Cys226 than any other Cys residue. Table 1 summarizes the NEM inactivation results, at 10 min and 80 min of treatment, for the complete panel of seHAS Cys-mutants.

Figure 5. Reactivity of [14C]NEM with the Cys-to-Ala triple Cys-mutants of seHAS.

Equal amounts of E. coli membranes containing wildtype or a triple Cys-mutant of seHAS were treated with [14C]NEM and subjected to SDS-PAGE as described in Methods. The 367 lane, which showed no labeling with NEM, is identical to the result with the Cys-null seHAS mutant reported previously (Kumari et al., 2002).

Table 1. Effect of Cys-mutations on the inhibition of seHAS by NEM.

The extent of enzyme inactivation after treatment with 5 mM NEM for 10 min or 80 min was determined in three independent experiments. Samples were quenched and assayed for residual HAS activity as described in Methods. The values shown are the mean ± SEM (for three independent experiments; n=3) relative enzyme activity lost compared to the untreated controls (100 percent minus the percent activity of the treated sample).

| Inhibition of activity by NEM (percent) | ||

|---|---|---|

| SeHAS Cys-mutants | 10 min | 80 min |

| C226A | 46 ± 1 | 66 ± 1 |

| C262A | 70 ± 6 | 97 ± 1 |

| C281A | 5 ± 3 | 30 ± 5 |

| C367A | 32 ± 3 | 61 ± 6 |

| WT | 34 ± 2 | 63 ± 3 |

| C226S | 29 ± 2 | 55 ± 2 |

| C262S | 87 ± 2 | 93 ± 1 |

| C281S | 60 ± 1 | 88 ± 1 |

| C367S | 34 ± 2 | 75 ± 2 |

| WT | 36 ± 3 | 78 ± 4 |

| C(226,262)A | 72 ± 2 | 80 ± 2 |

| C(226,281)A | 29 ± 2 | 37 ± 1 |

| C(226,367)A | 39 ± 2 | 60 ± 2 |

| C(262,281)A | 11 ± 2 | 59 ± 2 |

| C(262,367)A | 77 ± 3 | 96 ± 2 |

| C(281,367)A | 15 ± 1 | 35 ± 2 |

| WT | 43 ± 4 | 77 ± 3 |

| 3ΔC(C226) | 24 ± 2 | 81 ± 8 |

| 3ΔC(C262) | 26 ± 4 | 32 ± 3 |

| 3ΔC(C281) | 25 ± 2 | 22 ± 1 |

| 3ΔC(C367) | 1 ± 2 | 14 ± 3 |

| WT | 40 ± 2 | 71 ± 2 |

Double and triple seHAS Cys-mutants show differential sensitivity to sodium arsenite

The above results show that the presence or absence of an NEM-modified Cys residue may influence the subsequent reactivity of other Cys residues in seHAS, indicating that some combination(s) of Cys226, Cys262, or Cys281 are very close spatially in the active enzyme. Sodium arsenite can react to crosslink two vicinyl Cys residues; two SH groups that are adjacent or spatially very close in the folded protein (Chakraborti et al., 1992; Stancato et al., 1993; Bhattacharjee and Rosen, 1996). Wildtype seHAS was inhibited ~41% by treatment with 10 mM sodium arsenite (Table 2). To assess whether specific pairs of Cys residues in seHAS are close together and could account for this sensitivity of wildtype enzyme, we assessed the effect of sodium arsenite treatment on the activity of the six double Cys-mutants. The four triple Cys-mutants, which served as controls for the effects of possible reaction with individual Cys residues, were inhibited only 1–10% by the same sodium arsenite treatment. Four of the double Cys-mutants were also inhibited by <10%. In contrast, the C(226,367)A mutant in which Cys262 and Cys281 are present was inhibited 45%, essentially the same as wildtype seHAS. The C(226,262)A mutant in which Cys281 and Cys367 are present showed 19% inhibition, a sensitivity to NEM that was intermediate between the controls and wildtype. The results suggest that Cys262 and Cys281 are in very close proximity, and that Cys281 and Cys367 are also close enough to be cross-linked by arsenite, although to a lesser extent.

Table 2. Effect of sodium arsenite on the activity of seHAS Cys mutants.

E. coli membranes containing wildtype seHAS or the indicated double or triple Cys-mutants were incubated in PBS with or without 10 mM sodium arsenite at 4°C for 1 h. The activity of seHAS was then determined in triplicate as described in Methods. The values shown are the mean ± SEM inhibition relative to the no sodium arsenite treatment controls based on two experiments (n=6) for the double mutants or one experiment (n=3) for the single mutants (n=9 for wildtype).

| seHAS Mutant | Inhibition (%) |

|---|---|

| C(226,262)A | 19 ± 1 |

| C(226,281)A | 2 ± 1 |

| C(226,367)A | 45 ± 5 |

| C(262,281)A | 9 ± 3 |

| C(262,367)A | 8 ± 1 |

| C(281,367)A | 5 ± 3 |

| Δ3C(C226) | 3 ± 1 |

| Δ3C(C262) | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Δ3C(C281) | 10 ± 2 |

| Δ3C(C367) | 5 ± 1 |

| WT | 41 ± 2 |

Many of the seHAS Cys-mutants are protected from NEM inactivation by UDP-sugars

All of the seHAS Cys-mutants are active (Kumari et al., 2002), although double mutant C(226,262)A and triple mutant (Δ3C)C281 have only ~2% activity relative to wildtype. The cys-null seHAS mutant is substantially more active (~20% of wildtype) than these latter two mutants. Thus, none of the four Cys residues is critical or necessary for enzyme activity, although the above results showed that modification of Cys226, Cys262, or Cys281 by NEM caused inhibition and the arsenite sensitivity indicates that Cys262, Cys281 and Cys367 are very close together. To determine the effect of substrates on NEM inactivation, membranes containing wildtype or mutant seHASs were preincubated with UDP, UDP-GlcUA or UDP-GlcNAc prior to and during treatment with NEM. Changes in the rate of NEM inhibition were evaluated during the first 10 min.

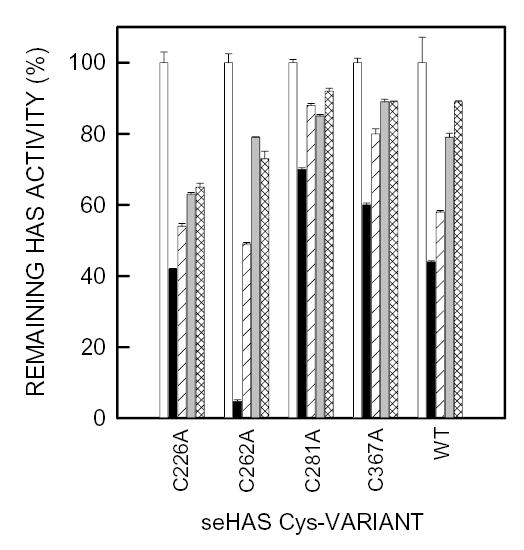

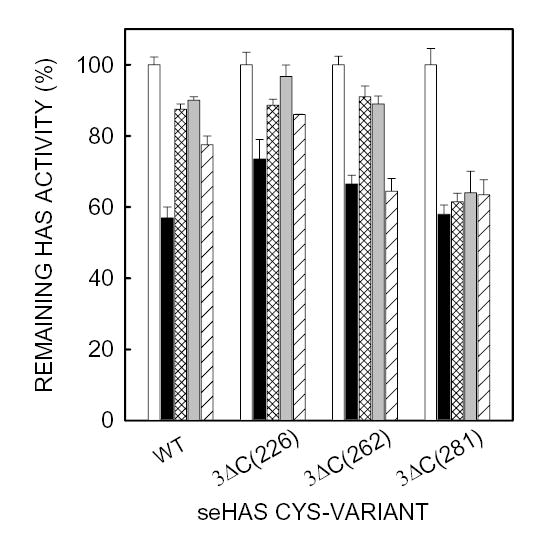

Wildtype seHAS was protected from NEM inhibition by either UDP-GlcUA or UDPGlcNAc, and also somewhat by UDP (Fig. 6). The single Cys-mutants C226A, C262A, C281A and C367A were also protected to varying degrees from NEM inhibition by UDP, UDP-GlcUA, and UDPGlcNAc, although seHAS(C226A) was less protected than the other three mutants by any of the substrates. For the C281A and C367A mutants, any of the substrates provided ≥50% protection from inactivation by NEM. The C262A mutant showed a dramatic protection of ~75% by UDP-sugars. The finding that the UDP-sugars protected all four single Cys-mutants from NEM inhibition is consistent with the conclusion that more than one Cys residue reacts with the sulfhydryl reagent, and that several of the NEM-reactive cysteines are located either in or very close to a UDP-sugar binding pocket. Limited studies with the double Cys-mutants confirmed these general conclusions (not shown). The substrate protection characteristics of the three triple Cys-mutants that were sensitive to NEM inhibition were examined in more detail (Fig. 7). Mutants seHAS(Δ3C)226 and seHAS(Δ3C)262 were protected from NEM inhibition by both UDP-sugar substrates, whereas the seHAS(Δ3C)281 mutant was not protected. The protection from NEM inhibition in the seHAS(Δ3C)226 and seHAS(Δ3C)262 mutants indicates that Cys226 and Cys262 are close enough to a UDP binding site of a substrate that they are not accessible to react with NEM when the site is occupied.

Figure 6. Effect of substrates on NEM inhibition of seHAS single Cys-to-Ala mutants.

Different amounts of membrane protein, to compensate for their different levels of enzyme activity, containing wildtype or mutant seHAS were incubated at 4°C for 1 h in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 containing 10 mM MgCl2 and either PBS alone (open and solid bars) 1.5 mM UDP (diagonal line bars), 1.5 mM UDP-GlcNAc (gray bars), or 0.6 mM UDP-GlcUA (cross-hatched bars). The membranes were then incubated with 5 mM NEM (solid, diagonal line, gray and cross-hatched bars) or PBS alone (open bars) for 10 min at 4°C. DTE was then added to all samples to a final concentration of 25 mM, and the remaining HAS activity in each sample was determined as described in Methods. For each HAS variant, the activity without NEM (control) was set at 100% and the activity with NEM is expressed as a % of control. Results are the mean ± SEM for three separate experiments (n=3). The specific activities of the seHAS single Cys-mutants used (as a percent relative to the wildtype) were approximately 25% for C226A, 60% for C262A, 62% for C281A, and 140% for C367A (Kumari et al, 2002).

Figure 7. Substrate Protection from NEM inhibition of seHAS triple Cys-mutants.

Different amounts of membrane protein, to compensate for their different levels of enzyme activity, containing wildtype or mutant seHAS were treated with NEM and processed as described in Fig. 6 and Methods. Samples were either untreated (open bars) or treated with NEM in the presence of UDP-GlcUA (cross-hatched bars), UDP-GlcNAc (gray bars), UDP (diagonal line bars) or no additions (solid bars). For each HAS variant, the activity without NEM (control) was set at 100% and the activity with NEM was expressed as a % of control. Results are the mean ± SEM for assays performed in triplicate from two separate experiments (n=6), using different membrane preparations. The specific activities of the seHAS triple Cys-mutants used (as a percent relative to the wildtype) were approximately 48% for 3ΔC226, 50% for 3ΔC262, and 3% for 3ΔC281 (Kumari et al, 2002).

Discussion

Cysteines play a variety of catalytic, structural, and functional roles in many types of proteins (Saito, 1989; Carugo et al., 2003; Jose-Estanyol et al., 2004). Although reducing agents have been included in assay buffers since the first report identifying HAS activity (Markovitz et al., 1959), it was not appreciated until recently how sensitive these enzymes are to inhibition by sulfhydryl reagents (Kumari et al., 2002, Pummill and DeAngelis, 2002). We previously found that seHAS and spHAS do not contain disulfide bonds, and that their Cys-null mutants are active. Thus, the role of cysteines in Class I HAS function is not straightforward, since they are not absolutely required for activity, but yet their modification results in substantial activity loss. To understand this intriguing result and determine the function of Cys residues in this simplest member of the family, we studied a panel of 18 seHAS Cys-mutants, which were characterized earlier in terms of protein expression levels and kinetic parameters (Kumari et al., 2002).

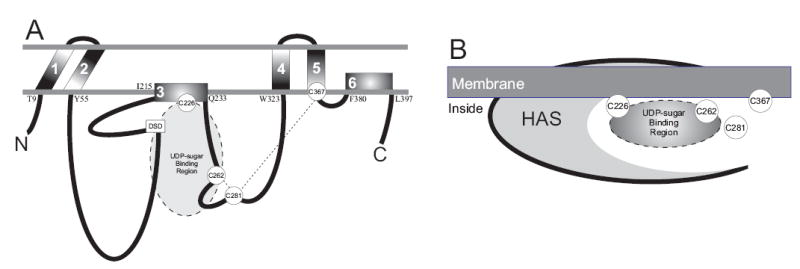

Our present findings showed complicated patterns of NEM inactivation of the seHAS Cys-mutants that presumably reflected the reactivity of their cysteines with NEM. Only in a few cases was a Cys-mutant unaffected by NEM treatment. The question of which Cys residues were modified by NEM was addressed by determining the ability of the triple Cys-mutants to be labeled by [14C]NEM (Fig. 5). Of the four Cys residues in seHAS, only Cys367 was not covalently modified by [14C]NEM. Cys367 is either inaccessible to or does not react well with NEM (137 Da), but yet it does react with the slightly smaller arsenite (AsO2−; 107 Da). This differential reactivity is consistent with the localization of Cys367 at the membrane-cytoplasm junction of MD5 (Heldermon et al., 2001), and indicates that this Cys residue may be partially buried within MD5 (Fig. 8A). Since modification of Cys226, Cys262, or Cys281 in the triple Cys-mutants caused inhibition, we conclude that inhibition of the single and double seHAS Cys-mutants results from the NEM modification of any of these three residues, either singly or in combination.

Fig. 8. Model for the topology of seHAS and the orientation of cysteines relative to the membrane.

A. The topological scheme shows the location of the six membrane domains (numbered 1–6) and the four cysteines (circled in white). The amino acid predicted to be at each membrane junction is indicated on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. The dashed lines between Cys262- -Cys281 and Cys281- -Cys367 indicate that these Cys pairs are close enough to be crosslinked by sodium arsenite. The shaded oval indicates a UDP-sugar binding site. The small box indicates the DXD motif (DSD161) in seHAS that is characteristic of UDP binding sites in glycosyltransferases. Details of the model are described in the text. B. The schematic illustrates that all four Cys residues of seHAS are clustered in or near a UDP-sugar binding site (either one or two) located at the interface between the inner membrane and the protein.

Although the reactivity kinetics of individual Cys residues may be altered in some of the Cys-mutants, it is likely that the same cysteines are modified in the wildtype enzyme. The much greater labeling of wildtype seHAS compared to the individual triple Cys-mutants (Fig. 5) also supports the conclusion from the activity inhibition studies (Figs 1-4) that multiple Cys residues are modified. Based on all of the above results, we conclude that Cys226, Cys262, and Cys281 in wildtype seHAS can react with NEM, resulting in inhibition, whereas Cys367 essentially does not react with NEM (i.e. the reaction rate is extremely slow; Fig 4A). The overall pattern of modification (i.e. the combinations of modified Cys residues) and the resulting effect on activity is likely dependent on which residue is modified first.

The Cys-to-Ala and Cys-to-Ser mutant pairs at positions 226, 262 and 367 showed similar changes in sensitivity to NEM, relative to wildtype. Interestingly, however, changing Cys281 to Ser281 made the enzyme very susceptible to NEM inhibition, whereas the Cys281-to-Ala281 change made it resistant. We interpret this result to indicate that the nature of the side chain at position 281 influences the accessibility or reactivity of other Cys residues to NEM. Although the atomic volume difference between the side chains of Ala and Ser is relatively small, the ability of Ser to interact differently than Cys with a nearby H-bond acceptor or donor might stabilize a conformation in which NEM access to the other Cys residues is enhanced. Alternatively, these opposite effects could be due to the difference in hydrophobicity between Ala and Ser.

Since the NEM inhibition kinetics of seHAS(C226A) and seHAS(C367A) were similar to wildtype, it is likely that Cys262 and Cys281 are accessible to and modified by NEM in all three seHAS variants. Since we know that Cys367 does not react with NEM, we also conclude from this result that Cys226 may not be responsible for the sensitivity of wildtype seHAS to NEM inhibition. In contrast, seHAS(C262A) and seHAS(C262S) were almost completely inhibited by NEM, indicating that altering Cys262 actually made Cys226, Cys281, or both residues more accessible to or reactive with NEM, resulting in greater enzyme inactivation. Our interpretation of the above results is that Cys226 can react with NEM in many of the Cys-mutants, although in wildtype seHAS the NEM modification of Cys262 or Cys281 inhibits the NEM modification of Cys226. When Cys262 is changed to Ala or Ser, NEM can then react with Cys226 as well.

The NEM inhibition of wildtype seHAS and some of the Cys-mutants tested were partially prevented by UDP-GlcNAc or UDP-GlcUA, and even UDP. Since triple Cys-mutant seHAS(ΔC)C281 was not protected by any of these substrates, we conclude that Cys281 is not in or close enough to a UDP-sugar binding site. However, substrate protection was observed for Cys226 and Cys262, indicating that these cysteines are located close enough to one or more substrate binding sites of seHAS that NEM reactivity is lost when the site is occupied. Since both substrates protected the enzyme from NEM inhibition, we conclude that either there is only one UDP-sugar binding site, which alternates its sugar specificity, or there are two very close binding sites so that occupancy of one site blocks access to other Cys residues in or near the second binding site.

An alternative possibility is that binding of a UDP-sugar may cause a conformation change that hinders NEM access to other Cys residues that are not spatially close to the UDP-sugar binding site. However, we previously noted that all the UDP-containing molecules tested (e.g. UTP and UDP-sugars) inhibit seHAS activity, although there is no evidence for misincorporation of other sugars by the enzyme (Kumari and Weigel, 1997; Tlapak-Simmons et al., 1999b). We previously found that the kinetics of HA synthesis is also slowed if one of the normal UDP-sugar substrates is in large excess over the other. The UDP portion of any of these molecules is apparently able to bind to either UDP-sugar binding site. In a similar study, a broad range of pyrophosphoryl-containing compounds protected xlHAS1 from inactivation by NEM (Pummill and DeAngelis, 2002).

The present observation that substrates protect HAS from inactivation by NEM provides a rationale to explain the effect of sulfydryl modification on HAS activity. We found previously that the Km values for UDP-sugar utilization by seHAS Cys-mutants were changed only slightly by NEM inhibition, but the Vmax value decreased substantially (Kumari et al., 2002). The current findings are consistent with the earlier conclusion that sulfhydryl group modification results in hindered substrate utilization by the enzyme, which slows the overall polymerization rate of substrates into HA. Inhibition could be caused by several effects of NEM-modified Cys residues. For example, they could affect enzyme function by altering interactions with a bound substrate, by changing a conformation of the protein, or a local chemical environment needed for one of the enzyme’s multiple functions.

Other proteins and enzymes have been reported to contain clusters of Cys residues involved in the binding of ligands or substrates, including the retinoic acid receptor protein (Wolfgang et al., 1997), glutathione synthetase (Kato et al., 1988), the glucocorticoid receptor (Stancato et al., 1993), and the ArsA ATPase (Bhattacharjee and Rosen, 1996). Single Cys residues are often part of a substrate binding site, such as in the lactose permease of E. coli, in which Cys148 interacts weakly and hydrophobically with the galactosyl moiety of the substrate (Jung et al., 1994). In Class I HAS family members, Cys226 is adjacent to a conserved motif, (S/G)GPL, which is associated with β-GlcUA transferase activity in mouse HAS1 (Yoshida et al., 2000). Our present results could support the involvement of Cys226 either in UDP-GlcUA binding or hyaluronyl transfer from HA-UDP to UDP-GlcUA. Cys262 is also in the middle part of conserved motif GDDR(C/H)LTN, found in all HAS 1 family members. The function of this region is not yet known.

A model that explains the present results is that Cys281 is near the entrance to a groove or pocket within the enzyme that contains Cys226 and Cys262, and that access to the interior of this groove is limited (Fig. 8B). This suggestion is also consistent with the organization of the three NEM-sensitive Cys residues within the enzyme and relative to the membrane. Based on the experimentally determined topology of spHAS (Heldermon et al., 2001), Cys226, Cys262, and Cys281 in seHAS are located in the large central sub-domain (Fig. 8A) between MD3 (which does not traverse the membrane) and MD4 (a transmembrane domain). The adjacent central subdomain between MD2 and MD3 contains a D-X-D sequence (DSD161), which is a conserved motif involved in UDP-sugar binding in β-glycosyltransferases (Breton and Imberty, 1999). Cys367 is at the C-terminal intracellular side of MD5, which spans the membrane. Interestingly, Cys226 is the only Cys residue that is absolutely conserved among all family members, and this residue is within MD3, which is an amphipathic helix.

We suggested previously that the growing HA chain is made at or within the membrane and translocated through the Class I HAS and the bilayer to the cell exterior (Tlapak-Simmons et al., 1999a). An alternative explanation for how HA is delivered to the cell exterior in streptococcal cells is that an ABC transport system for HA is required (Ouskova et al., 2004). Such ABC transporter systems are needed for the export of many different bacterial polysaccharides. However, if extracellular HA requires a transport system, it must not be specific for just HA, since Enterococcus facaelis (Deangelis et al., 1993) and Bacillus subtilis (unpublished results), bacteria that do not make HA, can synthesize and secrete large amounts of HA when transformed with the spHAS or seHAS gene, respectively. Also, the lipid dependence of the streptococcal Class I enzymes and the present finding that UDP-sugar binding sites are at the inner membrane surface are consistent with the growing HA chain being made at or within the membrane and then translocated through the enzyme to the exterior. If a separate transporter system is needed to deliver HA across the membrane, it is unclear why Class I HASs would have evolved to contain 6–8 transmembrane and membrane-associated domains instead of a single membrane domain, like the vast majority of glycosyltransferases - including the Class II HAS. Further studies are clearly required to define the mechanism by which HA is transferred across the cell membrane. The present findings suggest that Cys residues could be involved in this process, although this cannot yet be assessed.

The arsenite-sensitivity results indicate that Cys367 can be crosslinked to Cys281 and that Cys281 can also be crosslinked to Cys262. Two Cys residues can react with arsenite if their -SH groups are within about 3–5 Å (Bhattacharjee and Rosen, 1996; Sowerby, 1994). Based on our results, Cys281 is probably slightly closer to Cys262 than to Cys367. Since Cys367 is located at the membrane junction, Cys281 and Cys262 must also be very close to the membrane as illustrated in Fig. 8B. Therefore, three of the four Cys residues in seHAS are clustered very close together near substrate binding sites, and all four Cys residues are very close to or at the inner surface of the cell membrane. Since the four Cys residues in seHAS are generally conserved within the Class I HAS family, these enzymes also likely contain a similar Cys cluster near the membrane and near or in a substrate binding site.

Materials and Methods

Vectors, Primers and Reagents

The expression vector pKK223 was from Pharmacia Biotech Inc. E. coli SURE™ cells were from Stratagene. QuikChange™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits were from Stratagene. All mutagenic oligonucleotides were synthesized by Genosys Biotechnologies, Inc. (Spring, TX) and purified by reverse-phase chromatography. Cy-5 fluorescent sequencing primers were synthesized by the Molecular Biology Resource Facility, Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center. Other oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by The Great American Gene Co. (Ransom Hill Bioscience, Inc., CA.). UDP-GlcUA and UDP-GlcNAc were from Fluka and Sigma, respectively. UDP-[14C]GlcUA (300 mCi/mmol) and [14C]NEM (40 mCi/mmol) were from New England Nuclear. NEM and all other reagents were the highest grade available from Sigma unless otherwise noted. PBS was prepared according to the GIBCO formulation.

Site Directed Mutagenesis

The seHAS gene with a fusion at the 3′ end encoding a His6 tail (seHAs-His6) was cloned into pKK233 as described earlier (Kumari and Weigel, 1997). The following mutagenic primers were designed to change Cys to either Ala or Ser at positions 226, 262, 281 and 367 (primers are shown in the sense orientation with the altered codon in boldface font).

C226A: 5′-GGTAATATCCTTGTTGCCTCAGGTCCGCTTAGC;

C226S: 5′-GGTAATATCCTTGTTTCCTCAGGTCCGCTTAGC;

C262A: 5′- ATTGGTGATGACAGGGCCTTGACCAACTATGCA;

C262S: 5′-ATTGGTGATGACAGGTCCTTGACCAACTATGCA;

C281A: 5′-CAATCCACTGCTAAAGCTATTACAGATGTTCCT;

C281S: 5′-CAATCCACTGCTAAATCTATTACAGATGTTCCT;

C367A: 5′-TTCATTGTTGCCCTGGCTCGGAACATTCATTAC;

C367S: 5′-TTCATTGTTGCCCTGTCTCGGAACATTCATTAC.

Two complementary oligonucleotide primers encoding the desired mutation were used to create the single Cys mutations using the Quick Change method according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pKK233 plasmid containing the seHAS-His6 gene was amplified in SURE cells, purified using a Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis to verify the correct size. The purified pDNA was used as the template for the primer extension reactions with each pair of mutagenic primers. PCR, using pfu DNA polymerase, was performed for 16 cycles: 95°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 18 min. This amplification generated mutated plasmids with staggered nicks, which were then treated with DpnI to digest the methylated and hemi-methylated parental DNA. The digested pDNA was transformed into SURE cells and colonies were screened for the desired mutations by sequencing isolated pDNA using fluorescent terminators (ABI Prism 377 MODEL program, v2.1.1). The promoter and complete ORF of selected mutants were confirmed by sequencing in both directions with Cy-5 labeled vector primers using a Pharmacia ALF Express DNA Sequencer. Data were analyzed using ALF Manager, v3.02. The double, triple and null Cys-mutants of seHAS-His6 were made using an appropriate single, double or triple Cys-mutant pDNA as the template, respectively. The designation of triple Cys-mutants as seHAS(Δ3C)Cyyy denotes the deletion of three Cys residues leaving one free Cys at position yyy.

Effect of NEM modification on seHAS activity: Stock solutions of NEM (100 mM) were made in PBS. Membrane suspensions containing seHAS variants were incubated with 5 mM NEM at 4°C and aliquots were removed at different times, and added to assay buffer containing 10 mM DTE to quench unreacted NEM. The seHAS activity was determined at 37°C in 100 μl of 50 mM sodium and potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, with 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 240 μM UDP-GlcUA, 0.7 μM UDP-[14C]GlcUA and 600 μM UDP-GlcNAc. Reactions were terminated after 1 hr by the addition of SDS to a final concentration of 2% (w/v). The incorporation of [14C]GlcUA was determined by descending paper chromatography (Markovitz et al., 1959). Protein content was determined by the method of Bradford (1976) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. All seHAS Cys-mutants were assayed in duplicate or triplicate in two or three experiments using independent membrane preparations. Different amounts of membrane protein were used for each seHAS variant, so that similar levels of HAS activities were compared; all untreated samples showed good and similar HA synthesis (at least several thousand CPM). For each mutant or wildtype seHAS, the activity at zero-time (no NEM treatment) was set at 100% (control) and the remaining activities at different times are presented as a percentage of this control HAS activity. Results are presented as the mean ± standard error. All enzyme assays were performed under conditions that were linear with respect to time and protein concentration, and all the seHAS variant enzymes were stable under the conditions employed.

Substrate Protection of NEM inhibition: Different amounts of E. coli membrane protein containing seHAS variants, as noted above, were preincubated at 4°C for 1 hr in 50 mM sodium and potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, containing 10 mM MgCl2 and either 600 μM UDP-GlcUA, 1.5 mM UDP-GlcNAc or 1.5 mM UDP and then treated for 10 min at 4°C with or without 5 mM NEM. The reaction with NEM was terminated by addition of 10 mM DTE and HAS activity was then determined at 37°C in the assay buffer described above. The membrane samples were diluted 40-fold in the final assay buffer, so that the final concentration of unlabeled UDP-GlcUA was reduced to 15 μM. Since the concentration of radiolabeled UDP-GlcUA in the assay was 240 μM, the final change in specific radioactivity was small enough that it was ignored. Also since this dilution effect would cause a slight apparent inhibition of HA synthesis, our results slightly under-estimate (rather than over estimate) any protective effects for UDP-GlcUA. Under these conditions, there were also no effects of UDP or the other unlabeled UDP derivatives on seHAS activity in the absence of NEM.

Labeling of seHAS with [14C]NEM

Isolated membranes containing wildtype seHAS or one of the four triple Cys-mutants of seHAS were incubated at 4°C in PBS with 2.5 mM [14C]NEM (~8 × 106 dpm) for 5 min. The reactions were terminated by the addition of DTE to a final concentration of 5 mM. Membrane proteins were precipitated by incubation with 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid overnight at 4°C and free [14C]NEM was then removed by two cycles of centrifugation and resuspension with 5% trichloroacetic acid. The precipitated proteins were dissolved in 1× Laemmli (1970) sample buffer, neutralized by the addition of 0.1 N NaOH and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using a 10% gel. Coomassie Blue-stained gels were scanned using a Model PDSIP60 densitometer (Molecular Dynamics), treated with scintillants and subjected to fluorography using Biomax-MR (Kodak) film and an exposure of about one week. E. coli membranes prepared from cells transformed with vector alone, containing no seHAS, were included as a control.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM35978 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

References

- Abatangelo, G. and Weigel, P.H. (editors) New Frontiers in Medical Sciences: Redefining Hyaluronan.Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam. 2000.

- Asplund T, Brinck J, Suzuki M, Briskin MJ, Heldin P. Characterization of hyaluronan synthase from a human glioma cell line. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1380:377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee H, Rosen BP. Spatial proximity of Cys113, Cys172, and Cys422 in the metalloactivation domain of the ArsA ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24465–24470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton C, Imberty A. Structure/function studies of glycosyltransferases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:563–571. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinck J, Heldin P. Expression of recombinant hyaluronan synthase (HAS) isoforms in CHO cells reduces cell migration and cell surface CD44. Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:342–351. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carugo O, Cemazar M, Zahariev S, Hudaky I, Gaspari Z, Perczel A, Pongor S. Vicinal disulfide turns. Protein Eng. 2003;16:637–639. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti PK, Garabedian MJ, Yamamoto KR, Simons SS., Jr Role of cysteines 640, 656, and 661 in steroid binding to rat glucocorticoid receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11366–11373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis PL. Hyaluronan synthases: fascinating glycosyltransferases from vertebrates, bacterial pathogens, and algal viruses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:670–682. doi: 10.1007/s000180050461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis PL, Jing W, Drake RR, Achyuthan AM. Identification and molecular cloning of a unique hyaluronan synthase from Pasteurella multocida. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8454–8458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis PL, Jing W, Graves MV, Burbank DE, Van Etten JL. Hyaluronan synthase of chlorella virus PBCV-1. Science. 1997;278:1800–1803. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5344.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis PL, Papaconstantinou J, Weigel PH. Molecular cloning, identification, and sequence of the hyaluronan synthase gene from Group A Streptococcus pyogenes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19181–19184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenderson BA, Stamenkovic I, Aruffo A. Localization of hyaluronan in mouse embryos during implantation, gastrulation and organogenesis. Differentiation. 1993;54:85–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1993.tb00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Laurent UB. Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J Intern Med. 1997;242:27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulop C, Salustri A, Hascall VC. Coding sequence of a hyaluronan synthase homologue expressed during expansion of the mouse cumulus-oocyte complex. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;37:261–266. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.9793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldermon CD, DeAngelis PL, Weigel PH. Topological organization of the hyaluronan synthase from Streptococcus pyogenes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2037–2046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002276200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldermon CD, Tlapkak-Simmons VL, Baggenstoss BA, Weigel PH. Site directed mutation of conserved cysteine residues does not inactivate the Streptococcus pyogenes hyaluronan synthase. Glycobiol. 2001;11:1–8. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.12.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itano N, Kimata K. Mammalian hyaluronan synthases. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:195–199. doi: 10.1080/15216540214929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itano N, Kimata K. Expression cloning and molecular characterization of HA synthase protein, a eukaryotic hyaluronan synthase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9875–9878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.9875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itano N, Sawai T, Yoshida M, Lenas P, Yamada Y, Imagawa M, Shinomura T, Hamaguchi M, Yoshida Y, Ohnuki Y, Miyauchi S, Spicer AP, McDonald JA, Kimata K. Three isoforms of mammalian hyaluronan synthases have distinct enzymatic properties. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25085–25092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose-Estanyol M, Gomis-Ruth FX, Puigdomenech P. The eight-cysteine motif, a versatile structure in plant proteins. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2004;42:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Jung K, Kaback HR. Cysteine 148 in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli is a component of a substrate binding site. 1 Site-directed mutagenesis studies. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12160–12165. doi: 10.1021/bi00206a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass EH, Seastone CV. The role of the mucoid polysaccharide (hyaluronic acid) in the virulence of group A hemolytic streptococci. J Exp Med. 1944;79:319–330. doi: 10.1084/jem.79.3.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Tanaka T, Nishioka T, Kimura A, Oda J. Role of cysteine residues in glutathione synthetase from Escherichia coli B. Chemical modification and oligonucleotide site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11646–11651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson CB, Knudson W. Hyaluronan-binding proteins in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease. FASEB J. 1993;7:1233–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koprunner M, Mulleggerl J, Lepperdinger G. Synthesis of hyaluronan of distinctly different chain length is regulated by differential expression of Xhas1 and 2 during early development of Xenopus laevis. Mech Dev. 2000;90:275–278. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari K, Weigel PH. Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of the authentic hyaluronan synthase from Group C Streptococcus equisimilis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32539–32546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari K, Tlapak-Simmons VT, Weigel PH. The structural and functional role of cysteine residues in the hyaluronan synthase from Streptococcus equisimilis. Glycobiol. 1999;9:1134–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari K, Tlapkak-Simmons VL, Baggenstoss BA, Weigel PH. The streptococcal hyaluronan synthases are inhibited by sulfhydryl modifying reagents but conserved cysteine residues are not essential for enzyme function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13943–13951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markovitz M, Cifonelli JA, Dorfman A. The biosynthesis of hyaluronic acid by Group A streptococcus. VI Biosynthesis from uridine nucleotides in cell-free extracts. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:2343–2350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouskova G, Spellerberg B, Prehm P. Hyaluronan release from Streptococcus pyogenes: export by an ABC transporter. Glycobiology. 2004;14:931–938. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prehm P. Synthesis of hyaluronate in differentiated teratocarcinoma cells: Mechanism of chain growth. Biochem J. 1983;211:191–198. doi: 10.1042/bj2110191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pummill PE, DeAngelis PL. Evaluation of critical structural elements of UDP-sugar substrates and certain cysteine residues of a vertebrate hyaluronan synthase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21610–21616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pummill PE, Kempner ES, DeAngelis PL. Functional molecular mass of a vertebrate hyaluronan synthase as determined by radiation inactivation analysis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39832–39835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins PW, Bray D, Dankert M, Wright A. Direction of chain growth in polysaccharide synthesis. Science. 1967;158:1536–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.158.3808.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin-Toth M, Frillingos S, Lawrence MC, Kaback HR. The sucrose permease of Escherichia coli: functional significance of cysteine residues and properties of a cysteine-less transporter. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6164–6169. doi: 10.1021/bi000124o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N. Principles of protein architecture. Adv Biophys. 1989;25:95–132. doi: 10.1016/0065-227x(89)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyjan AM, Heldin P, Butcher EC, Yoshino T, Briskin MJ. Functional cloning of the cDNA for a human hyaluronan synthase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23395–23399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowerby, D.P. (1994) in The Chemistry of Organic Arsenic and Bismuth Compounds (Patai, S., ed) pp. 25–88, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York.

- Spicer AP, McDonald JA. Characterization and molecular evolution of a vertebrate hyaluronan synthase gene family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1923–1932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer AP, Augustine ML, McDonald JA. Molecular cloning and characterization of a putative mouse hyaluronan synthase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23400–23406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancato LF, Hutchison KA, Chakraborti PK, Simons SS, Jr, Pratt WB. Differential effects of the reversible thiol-reactive agents arsenite and methyl methanethiosulfonate on steroid binding by the glucocorticoid receptor. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3729–3736. doi: 10.1021/bi00065a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlapak-Simmons VL, Baggenstoss BA, Clyne T, Weigel PH. Purification and lipid dependence of the recombinant hyaluronan synthases from Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus equisimilis. J Biol Chem. 1999a;274:4239–4245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlapak-Simmons VL, Baggenstoss BA, Kumari K, Heldermon C, Weigel PH. Kinetic characterization of the recombinant hyaluronan synthases from Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus equisimilis. J Biol Chem. 1999a;274:4246–4253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlapak-Simmons VL, Baron CA, Weigel PH. Characterization of the purified hyaluronan synthase from Streptococcus equisimilis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9234–9242. doi: 10.1021/bi049468v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlapak-Simmons VL, Kempner ES, Baggenstoss BA, Weigel PH. The active streptococcal hyaluronan synthases (HASs) contain a single HA synthase monomer and multiple cardiolipin molecules. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26100–26109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.26100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlapak-Simmons VL, Weigel PH. Hyaluronan synthesis by the purified Class I hyaluronan synthase from S. pyogenes and S. equisimilis occurs by addition to the reducing end. Glycobiol. 2002;12:708. [Google Scholar]

- Toole BP. J. Intern. Med. 1997;242:35–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PN, Field TR, Ditcham WG, Maguin E, Leigh JA. Identification and disruption of two discrete loci encoding hyaluronic acid capsule biosynthesis genes hasA, hasB and hasC in Streptococcus uberis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:392–399. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.392-399.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Yamaguchi Y. Molecular identification of a putative human hyaluronan synthase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22945–22948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.22945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel PH. Functional characteristics and catalytic mechanisms of the bacterial hyaluronan synthases. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:201–211. doi: 10.1080/15216540214931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel PH, Hascall VC, Tammi M. Hyaluronan synthases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13997–14000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.13997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels MR, Goldberg JB, Moses AE, Dicesare TJ. Infect. Immun. 1994;62:433–441. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.433-441.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang CL, Zhang ZP, Gabriel JL, Pieringer RA, Soprano KJ, Soprano DR. Identification of sulfhydryl-modified cysteine residues in the ligand binding pocket of retinoic acid receptor beta. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:746–753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Itano N, Yamada Y, Kimata K. In vitro synthesis of hyaluronan by a single protein derived from mouse HAS1 gene and characterization of amino acid residues essential for the activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:497–506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]