Abstract

Background:

Obesity and metabolic dysregulation can lead to adverse outcomes in people with asthma. We hypothesized that pharmacological treatment of metabolic conditions in youth with asthma is associated with lowered risk of severe asthma exacerbations.

Research Question:

Is metabolic pharmacotherapy associated with a lower risk of severe asthma exacerbations among children and young adults with metabolic dysregulation?

Study Design and Methods:

This retrospective, quasi-experimental, longitudinal study examined severe asthma exacerbations (those requiring hospitalization or an emergency department [ED] visit) among youth aged 5-25 years with asthma and a history of a metabolic condition (obesity, diabetes, or hypertension). Definitions and diagnoses were based on documented international classification of diseases (ICD) codes. We compared the odds of severe asthma exacerbations before and after the initiation of metabolic pharmocotheraphy using adjusted piecewise generalized linear mixed models.

Results:

The cohort consisted of 783 patients, predominantly female (73.7%), white (71.6%), and non-Hispanic (90.4%). Metformin was the most frequently prescribed metabolic medication (75.4%). Before initiating metabolic pharmocotheraphy, the odds of severe asthma exacerbations increased by 29% per year (OR=1.29, 95%CI = 1.12-1.49). Conversely, following the commencement of metabolic pharmacotherapy, the odds of severe asthma exacerbations decreased by 66% per year (OR=0.34, 95%CI = 0.23-0.50), showing a statistically significant and marked difference between the pre- and post-treatment periods.

Interpretation:

Our findings show that the odds of severe asthma excerbations are substantially lower after the initiation of metabolic pharmacotheraphy, highlighting the positive impact that treatment of metabolic syndromes could have in reducing the risk of severe asthma exacerbations. This underscores the interconnectedness of metabolic and respiratory health and the need for further research into effective treatment strategies for individuals with asthma and obesity-related metabolic conditions.

Keywords: Obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, asthma, hospitalization, oral metabolics, metformin

INTRODUCTION

Asthma, a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, affects 25 million people in the U.S., including ~7.5 million children and young adults (ages 18-25 years).1 2 Many observational and epidemiological studies have identified an the association between metabolic conditions, such as obesity and metabolic syndrome, and asthma.3–8 Overweight and obesity, which affect 35-60% of the U.S. population, are associated with a higher risk of incident asthma.9 Moreover, among individuals with asthma, obesity is associated with increased asthma severity and morbidity, including more frequent and prolonged hospitalizations.10 “Obesity-related asthma” is a complex, likely multifactorial phenotype with various underlying mechanisms, including alterations in respiratory physiology and airway resistance, insulin resistance, low-grade systemic inflammation, and production of bioactive molecules that may alter immune responses.10–13

Standard asthma management typically includes the use of bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), and, in severe asthma, including both allergic and non-allergic phenotypes, monoclonal antibodies (often called “biologics”).14 Despite these treatments, many children with moderate-to-severe asthma experience frequent exacerbations and hospitalizations.15 In children with asthma, obesity has been associated with decreased response to bronchodilators and ICS.4,16 Although lifestyle interventions, such as a healthy diet and exercise, remain central to managing overall health as well as obesity-related asthma, sustained adherence is extremely difficult. Pharmacological interventions involving antidiabetic or “metabolic” medications have shown promise for reducing systemic inflammation, promoting weight loss, and improving metabolic health.7,17,18 Some medications –metformin, statins, and thiazolidinediones– have shown anti-inflammatory effects in lab studies and some clinical improvements in studies in adults.19,20 However, their effects on asthma-related outcomes remain unclear, particularly in children and young adults. Metformin, a biguanide used to treat type 2 diabetes,21,22 has anti-inflammatory properties and has been shown to improve airway inflammation in mouse models of obesity-related asthma.19,20 However, there is limited evidence to support the use of metformin as a treatment for patients with an asthma-metabolic syndrome comorbidity, particularly in the pediatric population.23–25 Yet, such pharmacological treatments for metabolic dysregulation may provide additional management options for youth with obesity-related asthma.

In this study, we aimed to investigate whether initiation of metabolic pharmacotherapy among children and young adults with asthma is associated with reduced risk of severe asthma exacerbations.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

Study design

A retrospective, quasi-experimental, longitudinal design was used to evaluate changes in annualized asthma-related hospitalization and ED rates before and after the initiation of metabolic medications. This design was selected to allow for the observation of patients over a significant period of time before and after drug initiation, enabling us to assess the long-term impact of metabolism-related medications on asthma outcomes.

Study setting and data sources

We extracted patient data from the Cerner electronic health record system (EHR) data warehouse used by [X] system affliatied institutions. [XH} is a comprehensive healthcare system that includes provides primary and subspecialty care for over 1.2M residents in our state.

Participants

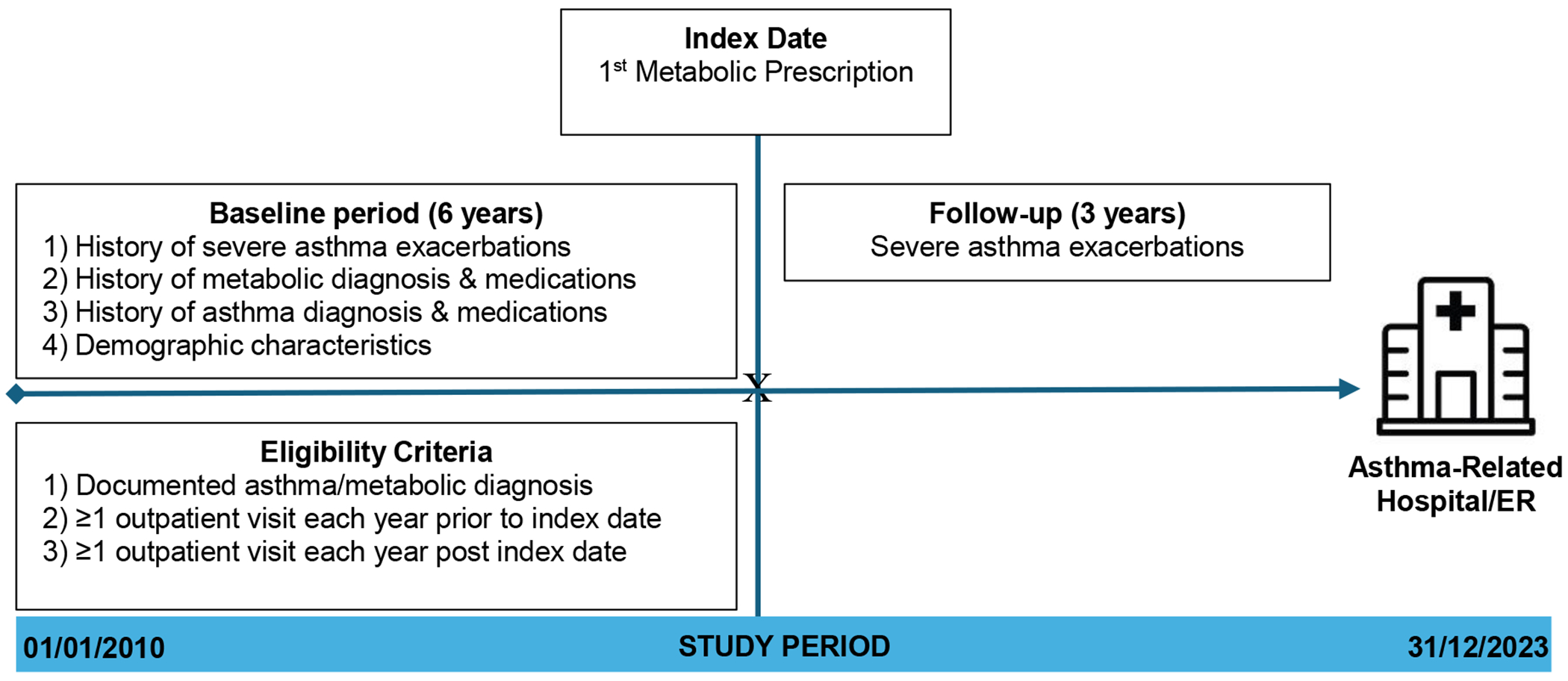

Study data were extracted from the EHR of patients who sought healthcare at the [X] System between January 1st 2010 and December 31st 2023. We used international classification of diseases 9/10 (ICD-9/10) codes to identify diagnoses of asthma, obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and hypertension. A full list of codes is available in Supplemental e-Table 1 Inclusion criteria required patients to be between 5 and 25 years of age at the time of metabolic medication initiation (index date).The patient cohort included children and young adults, and aged 5-25 years, who had a documented diagnosis of asthma (ICD-10 J45.XX; ICD-9 493.XX) and at least one of the following metabolic conditions: obesity (ICD-10 E66.XXX; ICD-9 278.XX), metabolic syndrome (ICD-10 E88.81; ICD-9 277.7X), or type 2 diabetes (ICD-10 E11.XXX; ICD-9 250.XX) prior to their index date (i.e., date of first metabolic medication prescription). Individuals with secondary diabetes (i.e., due to another disease or condition e.g., ICD-10 E08.xx, E09.xx, E10.xx, E13.xx, 250.81) were excluded. We restricted our analysis sample to only patients who sought routine outpatient care at least once each of the 6 years prior to their index date and 3 years after their index date (Figure 1). This longer pre-treatment duration was selected to establish a stable baseline trend. Three years post-treatment were included due to recency of some medications and follow-up data constraints. We excluded patients who had an ICS prescription before their first documented asthma diagnosis (ICD-10 J45.xx, 493.xx) to rule out prevalent asthma cases that might have received asthma-related care outside IUH. Patients with asthma medications preceding their asthma diagnosis were excluded to focus on incident asthma cases and reduce the potential for prevalence-incidence bias (i.e., . Similarly, patients with a metabolic-related medication before any metabolic condition diagnosis were excluded.The final study cohort consisted of 783 children and young adults (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Study Design Schematic

Figure 2:

Flowchart of the study participants selection

Outcome measure

Our primary outcome was the occurrence of at least one severe asthma exacerbation per patient per year (i.e., 12-month intervals) prior to and after the index date. A severe asthma exacerbation was defined as an asthma exacerbation that resulted in a hospitalization or ED visit.26 Asthma-related ED visits and hospitalizations were included only if the encounter listed asthma as a primary or secondary diagnosis (ICD-10 J45.xx).

Covariates

The main exposure variable of interest was prescription of metabolic-related medications as identified in the EHR. Metabolic medications included biguanides, sulfonylureas, SGLT2 inhibitors, DPP4 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1) receptor agonists (e-Table 2). Other covariates, considered as potential effect moderators and confounders (in the absence of statistically significant moderator effects), included sex, race, ethnicity, age at first metabolic medication exposure (i.e., prescription), age of first asthma diagnosis, history of antidiabetic (or type II diabetes diagnosi), hypertension, ICS, and biologic medication prescriptions prior to the study index date.

Statistical Methods

We used piecewise generalized linear mixed-effects models to estimate the rate of change in the annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations pre-post metabolic medication initiation. We selected these models for their ability to handle the complexity of longitudinal data with repeated measures while accounting for within-subject correlations over time.

We examined the mean profile of the annualized severe exacerbations before and after the critical time point (index year = 0, i.e., the year the first metabolic medication was prescribed) including the pairwise interaction term effects and additive effects of investigated covariates. We included a random intercept for each patient to account for the non-independence of repeated outcome measures (i.e., annualized occurrence of a severe exacerbation). Model fit statistics AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) were compared to inform model selection.

To further characterize the mean profile of severe asthma exacerbations pre-post metabolic medication exposure, we performed a priori planned subgroup analyses by sex, race, history of antidiabetic medication, and ICS exposure prior to the index date. We used a linear combination of coefficients to test for statistical significance on slopes before and after the index date, including a test for the difference in pre-post slopes. Formal corrections for multiple tests were not applied for the exploratory subgroup analyses, and results are interpreted as hypothesis-generating. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.2.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the EHR-based study cohort are shown in Table 1. The cohort comprised 783 youth aged 2-25 years; 73.7% were female and 26.3% were male. Patients were predominantly white (71.6%), followed by non-Hispanic Black or African American (24.5%); other racial groups, such as Asian, Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders, and individuals identified as two or more races made up a smaller percentage. In terms of ethnicity, 6.8% identified as Hispanic/Latinos. The average age at the patient’s first asthma diagnosis was 14 (standard deviation (SD)=7) years. Prior to the index year, 51.5% and 2.6% of the patients had prescriptions for ICS and biologics, respectively. At the index date, majority (50.8%) of the patients were 12-18 years old, 40.1% were 19-25 years old, and only only 9.1% were 5-11 years old. The majority (96%) of the patients were categorized as having obesity, 3% as having overweight, and 1% had healthy weight. Most patients (75.4%) were prescribed metformin as their first metabolic medication, followed by semaglutide (15.2%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic 1 | N = 783 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 577 (73.7%) |

| Male | 206 (26.3%) |

| Race | |

| White | 561 (71.6%) |

| Black/African American | 192 (24.5%) |

| Others 2 | 18 (2.3%) |

| Missing | 12 (1.5%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 708 (90.4%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 53 (6.8%) |

| Others 3 | 22 (2.8%) |

| Age at Time of Asthma Diagnosis (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 14 (7) |

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 15 [9, 20] |

| Min–Max | 0–25 |

| Age Group at Asthma Diagnosis | |

| 0-4 Years | 88 (11.2%) |

| 5-11 Years | 173 (22.1%) |

| 12-18 Years | 270 (34.5%) |

| 19-25 Years | 252 (32.2%) |

| Age at Time of Metabolic Medication Prescription (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 18 (4) |

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 19 [15, 22] |

| Min–Max | 6–25 |

| Age Group at Metabolic Medication Prescription | |

| 5-11 Years | 71 (9.1%) |

| 12-18 Years | 314 (40.1%) |

| 19-25 Years | 398 (50.8%) |

| Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS) | |

| No | 380 (48.5%) |

| Yes | 403 (51.5%) |

| Biologic(s) for Asthma | |

| No | 763 (97.4%) |

| Yes | 20 (2.6%) |

| First Metabolic Medication Prescribed | |

| Metformin | 590 (75.4%) |

| Semaglutide | 119 (15.2%) |

| Others 4 | 74 (9.5%) |

Table shows n(%) for categorical variables, or mean (SD) for continuous variables, unless otherwise specified.

Category included Asian: 8 (1.0%); Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islande 1 (0.1%); two or more races 9 (1.1%)

Category included missing or other ethnicity.

Category included liraglutide 35 (4.5%); tirzepatide 24 (3.1%); canagliflozin 1 (0.1%); dulaglutide 5 (0.6%); empagliflozin 5 (0.6%); glipizide 1 (0.1%); saxagliptin 2 (0.3%); and sitagliptin 1 (0.1%)

Severe asthma exacerbations before vs after metabolic medication initiation

Table 2 summarizes the overall and strata-specific odds of severe exacerbations pre-post metabolic medication start. Before metabolic medications were started, the odds of severe asthma exacerbations were 29% higher per year (odds ratio (OR) = 1.29, 95% confidence Interval (CI) = 1.12–1.49, p < 0.001); however, after metabolic medication were started, the odds of severe exacerbations were 66% lower per year (OR = 0.34, 95% CI = 0.23–0.50, p < 0.001) adjusted for sex, race, and age differences at the index date. None of the pairwise interaction terms (involving sex, race, age at first asthma diagnosis and age at index date) examined at baseline, pre and post-metabolic medication exposure were statistically significant (p>0.05). The overall rate of change in the odds of severe asthma exacerbations before and after medication initiation is also depicted in Figure 3. Sex-stratified analyses (Table 2 and Figure 4) revealed that male patients had a 15% higher pre-exposure odds of severe asthma exacerbations per year (OR=1.15, 95%CI=0.86 -1.54) and 62% lower post-exposure odds (OR= 0.38, 95%CI: 0.18, 0.79). Female participants had slightly higher pre-exposure odds (OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.14–1.57) and lower post-exposure odds (OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.22–0.51). White patients had higher pre-exposure odds of severe exacerbations (OR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.15–1.69) but Black patients did not (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 0.95–1.42). However, both White (OR = 0.31, 95%CI: 0.19–0.51) and Black (OR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.23–0.66) patients had lower post-exposure odds of severe exacerbations adjusted for sex and age differences at the index date (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure S1).

Table 2.

Piecewise GLMM Result Asthma Exacerbations Pre-post Metabolic Medication Exposure

| Characteristic | Strata | Variables | Crude Model * | Adjusted Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall 1 | - | Pre-slope | 1.29 (1.14-1.47) | 1.29 (1.12-1.49) |

| - | Post-slope | 0.34 (0.24-0.47) | 0.34 (0.23-0.50) | |

|

| ||||

| By Sex 2 | Male | Pre-slope γ | 1.15 (1.15,−1.16) | 1.15 (0.86-1.54) |

| Post-slope γ | 0.37 (0.36-0.37) | 0.38 (0.18-0.79) | ||

|

|

||||

| Female | Pre-slope | 1.33 (1.16-1.54) | 1.33 (1.14-1.57) | |

| Post-slope | 0.33 (0.23-0.48) | 0.33 (0.22-0.51) | ||

|

| ||||

| By Race 3 | White | Pre-slope | 1.40 (1.18-1.66) | 1.40 (1.15-1.69) |

| Post-slope | 0.31 (0.19-0.48) | 0.31 (0.19-0.51) | ||

|

|

||||

| Black | Pre-slope | 1.16 (0.96-1.41) | 1.16 (0.95-1.42) | |

| Post-slope | 0.39 (0.24-0.64) | 0.39 (0.23-0.66) | ||

|

| ||||

| By prior ICS medication exposure 5 | No | Pre-slope | 1.32 (1.03-1.70) | 1.32(0.99-1.76) |

| Post-slope | 0.33 (0.18-0.62) | 0.33 (0.16-0.69) | ||

|

| ||||

| Yes | Pre-slope | 1.29 (1.11, 1.49) | 1.29 (1.09-1.53) | |

| Post-slope | 0.34 (0.23-0.51) | 0.34 (0.22-0.54) | ||

|

| ||||

| By prior antidiabetic medication exposure 4 | No | Pre-slope | 1.24 (1.08-1.43) | 1.24 (1.05-1.46) |

| Post-slope | 0.30 (0.19-0.46) | 0.30 (0.18-0.50) | ||

|

| ||||

| Yes | Pre-slope | 1.50 (1.14-1.97) | 1.50 (1.09-2.05) | |

| Post-slope | 0.42 (0.25-0.69) | 0.42 (0.24-0.75) | ||

|

| ||||

| By prior history of hypertension 4 | No | Pre-slope | 1.16 (0.99 - 1.35) | 1.16 (0.98 - 1.36) |

| Post-slope | 0.19 (0.09 - 0.41) | 0.19 (0.09 - 0.43) | ||

|

| ||||

| Yes | Pre-slope | 1.34 (1.34 - 1.34) | 1.34 (1.34 - 1.35) | |

| Post-slope | 0.38 (0.38 - 0.38) | 0.38 (0.38 - 0.38) | ||

The crude model includes only time-related variables for estimating pre- and post-slopes, with no covariate adjustments.

CIs include the point estimate due to rounding to 2 decimal places and provide an example

The adjusted models for all subjects include sex, race, and age of first metabolic medication exposure.

Models stratified by sex include race, and age of first metabolic medication exposure as covariates.

Models stratified by race include sex, and age of first metabolic medication exposure as covariates.

Models stratified by prior antidiabetic medication exposure/type II diabetes diagnosis or hypertension diagnoses include sex, race, and age of first metabolic medication exposure as covariates.

Models stratified by prior ICS medication exposure include sex, race, and age of first metabolic medication exposure as covariates.

Figure 3:

Severe Asthma Exacerbations Before and After Metablic-Related Medication Initiation

Figure shows the observed proportion (and 95% confidence interval) of subjects with an asthma-related hospitalization / ED visit before and after starting a metabolic medication (time 0).

Figure 4:

Severe Asthma Exacerbations, Subgroup Analysis by Sex and ICS

Figure shows the observed proportions (and 95% confidence interval) of subjects with an asthma-related hospitalization / ED visit before and after starting a metabolic medication (time 0), stratified by sex (top) and by ICS use (bottom)

To evaluate the effect of metabolic medication exposure by asthma severity, we performed an analysis stratified by prior ICS medication exposure (Table 2 and Figure 4). Patients with prior ICS exposure had higher odds of severe exacerbations pre-metabolic medication exposure (OR=1.29, 95%CI: 1.09–1.53) and 66% lower odds of severe exacerbations post-exposure (OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.22–0.54). Similar trends were observed among patients without prior ICS exposure with a slightly lower pre-exposure odds of severe exacerbations and better post-exposure odds ratios.

Furthermore, to assess the effect of baseline diabetes (Type 2) disease, we performed an analysis stratified by prior antidiabetic medication exposure. Having prior anti-diabetic medication exposure was associated with higher odds of severe exacerbation pre-metabolic medication exposure(OR=1.50, 95%CI: 1.09–2.05) but lower odds post-exposure (OR=0.42, 95%CI: 0.24–0.75). Among patients without prior antidiabetic medication exposure, the magnitude of pre and post-exposure odds ratios of severe exacerbations was lower and followed a similar trend to that observed among patients with prior antidiabetic medication exposure (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure S2). Similarly, patients with a history of hypertension had higher pre-metabolic exposure odds of severe exacerbations per year (OR=1.34, 95%CI: 1.34 – 1.35); conversely, the pre-metabolic odds of severe exacerbations per year did not change among patients without a history of hypertension. Post-metabolic exposure, patients without (vs with) a history of hypertension had a more pronounced reduction in the odds of severe exacerbations (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This is the first long-term longitudinal, retrospective, quasi-experimental study of metabolic pharmacotherapy and severe asthma exacerbations that necessitate hospitalization or ED visit. Our main finding was that patients with an obesity-related asthma phenotype who initiated metabolic pharmacotherapy, experienced a significant reduction in severe asthma exacerbations. Prior to the initiation of metabolic medication, we observed increasing odds of asthma exacerbations, which may indicate worsening asthma symptoms that would require a change in a patient’s usual asthma treatment plan. In contrast, the odds of severe exacerbations were markedly decreased post-metabolic medication exposure; this considerable reduction underscores the potential benefits of metabolic pharmacotherapy to substantially improve asthma sysmptom control. Notably, the lower odds of severe exacerbations were observed across adjusted models, suggesting effectiveness may be independent of demographic factors such as sex, race, and age. Future studies should explore whether anti-inflammatory, insulin-sensitizing, or immunomodulatory properties of medications such as metformin underlie the observed reduction in exacerbation risk.

The relatively high pre-metabolic medication exposure odds of severe exacerbations among patients with (vs without) prior ICS suggests that, for patients who are overweight or obese, asthma targeted treatment alone may not be enough to avert excess acute healthcare utilization. Moreover, the benefits of initiating metabolic pharmacotherapy seem to be slightly attenuated among patients with (vs without) prior ICS exposure. A similar pattern of pre-post odds of severe exacerbations was observed for prior exposure to antidiabetic medications. The relatively high odds of severe exacerbations and attenuated benefit of initiating metabolic pharmacotherapy among patients with (vs without) prior exposure to antidiabetic medications may be linked to poorly controlled diabetes. Having diabetes has been shown to significantly increase the risk of developing severe asthma; this is likely due to shared mechanisms like chronic inflammation and insulin resistance present in both diseases.27. However, because our study analyses did not detect such moderation effects (i.e., the pairwise interaction terms involving prior exposure to antidiabetic x ICS medications were not statistically significant), replication of our findings in other study cohorts is warranted.

The non-significant hypothesis tests involving pairwise interaction terms (time by sex, age, or race) suggest that the effects of initiating metabolic pharmacotherapy may not vary depending on a patient’s demographic characteristics. However, the consistent and marked increase in the odds severe exacerbations pre-metabolic medication exposure in our subgroup analyses support the hypothesis that metabolic dysregulation, which is common in conditions such as obesity and diabetes, may indeed be associated with worse asthma control.7,28,29 Conversely, the initiation of metabolic pharmacotherapy may lead to improved asthma symptom control resulting in reduced risk of severe exacerbations.

Our study findings are consistent with existing research that shows a strong association between obesity, metabolic dysregulation, and asthma.4,10,30–32 Moreover, with the longer follow-up pre and post metabolic exposure, our findings suggest the risk of severe asthma exacerbations is not transient, nor are the benefits of initiating metabolic pharmacotherapy. These findings in youth may mirror similar trends seen in adult populations, which have been explored in prior studies using administrative or cohort data. Our findings are supported by prior research in adult populations that demonstrate a consistent association between metabolic medications and improved asthma outcomes. For instance,a study using data from the Genetic Epidemiology of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (COPDGene), a multicenter U.S. cohort designed to explore genetic factors in COPD, reported that metformin use was associated with improved respiratory outcomes in adults with asthma-COPD overlap.18 Similarly, a retrospective cohort study based on the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database reported that metformin users with both asthma and diabetes had better asthma control and fewer exacerbations compared to non-users.7 In a large Taiwanese cohort, it observed that insulin use increased asthma risk, while metformin use significantly reduced it.8 Together, these studies reinforce the hypothesis that metabolic pharmacotherapy may improve asthma outcomes through anti-inflammatory or metabolic regulatory mechanisms. Our study builds on this body of evidence, extending these findings to a younger population, and suggests that the respiratory benefits of metabolic medications may manifest early in the disease course.These findings suggest that incorporating metabolic-related medications into treatment regimens for patients with the obesity asthma phenotype could have substantial benefits in reducing healthcare utilization, attenuating severe exacerbations, and improving asthma control.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Our findings underscore the importance of managing metabolic conditions in children and youth with asthma. Demonstrating a significant decrease in severe asthma exacerbations after initiation of metabolic medications emphasizes the importance of an integrated care approach addressing both respiratory and metabolic health. This approach could involve routine screening for metabolic disorders in pediatric patients with asthma, ensuring early identification and management of comorbid conditions. Implementing routine screening protocols for metabolic disorders in youth with asthma can facilitate the early detection of conditions, such as obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes, which are known to exacerbate asthma symptoms. 27,33,34 The incorporation of pharmacological treatments for these metabolic conditions into asthma management plans may yield substantial benefits. Healthcare providers may be able improve patient outcomes by adopting a holistic approach to address underlying metabolic disturbances that contribute to asthma severity.

Limitations and Strengths

This study had some limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. One key limitation was the lack of a concurrent control group and therefore the possibility that effects observed were due to other reasons, such as changes in institution-specific asthma management practices, cannot be ruled out. Moreover, the reliance on data from a single healthcare system may restrict the generalizability of the results. However, our health system emcompases a large population of the state which makes out findings more likely representative. Additionally, the relatively small sample size, especially when divided into subgroups, may have reduced the statistical power to detect potential moderated associations (i.e., tested as statistical interactions). Adjusting for multiple variables may introduce collider bias, and this risk was considered in the final model specification. Odds ratios do not directly translate into risk reductions; interpretations should be made with caution, especially given the quasi-experimental design. Because this was a quasi-experimental study without randomization, causal inferences cannot be made.35 Despite rigorous adjustments, there is still potential for residual confounding from unmeasured factors, such as socioeconomic status or environmental exposures, which may have influenced the results. Finally, recent changes in asthma guidelines (e.g., NAEPP 2020 focused updates, Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2020 and later) may have had an effect in asthma outcomes; however, it is important to note that a large proportion of subjects had index dates that did not coincide with those guideline changes, and the impact of guidelines is likely not immediate nor homogeneous in clinical practice.

This study also had notable strengths. There is a notable lack of large, prospective randomized clinical trials specifically addressing asthma in the context of obesity;23 while studies on antidiabetic medications show promise, they have been predominantly observational with a focus on adult populations, making this one of the few studies focused on children and young adults.36 The use of comprehensive healthcare system data ensured that all relevant healthcare interactions were captured, leading to a more accurate analysis of the impact of metabolism-related medications on asthma outcomes. This study was enhanced by using long-term longitudinal data to track asthma related hospitalization or ER visits before and after initiation of metabolic pharmacotherapy in the same patients. Furthermore, we minimized potential confounding factors by adjusting for multiple covariates, including demographic factors, pre-index date exposure to antidiabetic medications, and inhaled corticosteroids. This careful adjustment ensured that the observed changes in the odds of severe exacerbations were more likely to be due to initiation of metabolic pharmacotherapy.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate a substantial reduction (60-70%) in severe asthma exacerbations that require hospitalizations or emergency department visits after initiation of metabolic medications. This study provides important insights into the potential benefits of metabolic-related medications for patients with asthma and an obesity-related phenotype.

Future Research Directions

Our findings suggest several key directions for future research. First, larger multicenter studies in more diverse populations will be necessary to confirm the generalizability of our results and expand our understanding of how metabolic medications may improve asthma control. If these findings are consistently replicated, future research should include carefully designed, controlled, randomized clinical trials, before any clinical recommendations can be made. Future investigations should explore the biological mechanisms linking metabolic dysfunction and asthma outcomes, ideally through mechanistic or biomarker-based studies. Randomized controlled trials are also necessary to confirm these observational findings and to better understand causal pathways. Further research on the biological mechanisms linking metabolic dysregulation and asthma is crucial. Exploring combined therapeutic strategies that integrate metabolic medications with other treatments, such as biologics and lifestyle interventions, could improve outcomes in patients with severe asthma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Regenstrief Data Services at the Regenstrief Institute, Indiana University, and the Indiana University Health data team for providing access to the Indiana Network for Patient Care electronic health records data, which we utilized for this analysis.

Funding statement:

This study was supported by US NIH grants HL149693 and HL170368 (EF), HL166436 and HS029088 (AO), and the Riley Children’s Foundation (EF and AO).

List of Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence Interval

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- ED

Emergency Department

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- ICS

Inhaled Corticosteroids

- OR

Odds Ratio

Footnotes

Summary conflict of interest statements: The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Approval Statement/Ethics Statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Indiana University School of Medicine, with a waiver consent for de-identified data (Protocol #:15869).

Permission to reproduce material from other sources: Not applicable.

Clinical trial registration: Not applicable.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Pate CA, Zahran HS, Qin X, Johnson C, Hummelman E, and Malilay J (2021). Asthma Surveillance - United States, 2006-2018. MMWR Surveill Summ 70, 1–32. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7005a1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zablotsky B, Black LI, and Akinbami LJ (2023). Diagnosed Allergic Conditions in Children Aged 0-17 Years: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forno E (2016). Asthma and diabetes: Does treatment with metformin improve asthma? RESPIROLOGY 21, 1144–1145. 10.1111/resp.12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forno E, Lescher R, Strunk R, Weiss S, Fuhlbrigge A, and Celedón JC (2011). Decreased response to inhaled steroids in overweight and obese asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127, 741–749. 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forno E, and Celedón JC (2017). The effect of obesity, weight gain, and weight loss on asthma inception and control. CURRENT OPINION IN ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY 17, 123–130. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foer D, Beeler P, Cui J, Snyder WE, Mashayekhi M, Nian H, Luther J, Karlson E, Boyce J, and Cahill K (2023). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist use is associated with lower serum periostin. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 10.1111/CEA.14284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li CY, Erickson SR, and Wu CH (2016). Metformin use and asthma outcomes among patients with concurrent asthma and diabetes. RESPIROLOGY 21, 1210–1218. 10.1111/resp.12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CZ, Hsu CH, Li CY, and Hsiue TR (2017). Insulin use increases risk of asthma but metformin use reduces the risk in patients with diabetes in a Taiwanese population cohort. JOURNAL OF ASTHMA 54, 1019–1025. 10.1080/02770903.2017.1283698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beuther D, and Sutherland ER (2007). Overweight, obesity, and incident asthma: a meta-analysis of prospective epidemiologic studies. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 10.1164/RCCM.200611-1717OC. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters U, Dixon AE, and Forno E (2018). Obesity and asthma. JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY 141, 1169–1179. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forno E, Weiner DJ, Mullen J, Sawicki G, Kurland G, Han YY, Cloutier MM, Canino G, Weiss ST, Litonjua AA, and Celedón JC (2017). Obesity and Airway Dysanapsis in Children with and without Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195, 314–323. 10.1164/rccm.201605-1039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shore SA, Terry RD, Flynt L, Xu A, and Hug C (2006). Adiponectin attenuates allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in mice. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 10.1016/J.JACI.2006.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shore SA, Schwartzman IN, Mellema MS, Flynt L, Imrich A, and Johnston RA (2005). Effect of leptin on allergic airway responses in mice. JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY 115, 103–109. 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddel HK, Bacharier LB, Bateman ED, Brightling CE, Brusselle GG, Buhl R, Cruz AA, Duijts L, Drazen JM, FitzGerald JM, et al. (2022). Global initiative for Asthma Strategy 2021: executive summary and rationale for key changes. EUROPEAN RESPIRATORY JOURNAL 59, 2102730. 10.1183/13993003.02730-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacharier L, Strunk R, Mauger D, White D, Lemanske R, and Sorkness C (2004). Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 10.1164/RCCM.200308-1178OC. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGarry ME, Castellanos E, Thakur N, Oh SS, Eng C, Davis A, Meade K, LeNoir MA, Avila PC, Farber HJ, et al. (2015). Obesity and bronchodilator response in black and Hispanic children and adolescents with asthma. Chest 147, 1591–1598. 10.1378/chest.14-2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li CY, Erickson SR, and Wu CH (2017). Metformin use and asthma: Further investigations. RESPIROLOGY 22, 203–204. 10.1111/resp.12922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu TD, Fawzy A, Kinney GL, Bon J, Neupane M, Tejwani V, Hansel NN, Wise RA, Putcha N, and McCormack MC (2021). Metformin use and respiratory outcomes in asthma-COPD overlap. RESPIRATORY RESEARCH 22, 70. 10.1186/s12931-021-01658-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu CJ, Loube J, Lee RC, Bevans-Fonti S, Wu TD, Barmine JH, Jun JC, McCormack MC, Hansel NN, Mitzner W, and Polotsky VY (2022). Metformin Alleviates Airway Hyperresponsiveness in a Mouse Model of Diet-Induced Obesity. FRONTIERS IN PHYSIOLOGY 13, 883275. 10.3389/fphys.2022.883275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo YM, Shi JT, Wang QJ, Hong LN, Chen M, Liu SY, Yuan XQ, and Jiang SP (2021). Metformin alleviates allergic airway inflammation and increases Treg cells in obese asthma. JOURNAL OF CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR MEDICINE 25, 2279–2284. 10.1111/jcmm.16269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schernthaner G, and Schernthaner GH (2020). The right place for metformin today. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 159, 107946. 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad E, Sargeant JA, Zaccardi F, Khunti K, Webb DR, and Davies MJ (2020). Where Does Metformin Stand in Modern Day Management of Type 2 Diabetes? Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 13. 10.3390/ph13120427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Averill SH, and Forno E (2024). Management of the pediatric patient with asthma and obesity. ANNALS OF ALLERGY ASTHMA & IMMUNOLOGY 132, 30–39. 10.1016/j.anai.2023.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Althoff MD, Gaietto K, Holguin F, and Forno E (2024). Obesity-related Asthma: A Pathobiology-based Overview of Existing and Emerging Treatment Approaches. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 10.1164/rccm.202406-1166SO. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ararat E, Landes RD, Forno E, Tas E, and Perry TT (2024). Metformin use is associated with decreased asthma exacerbations in adolescents and young adults. PEDIATRIC PULMONOLOGY 59, 48–54. 10.1002/ppul.26704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet LP, Boushey HA, Busse WW, Casale TB, Chanez P, Enright PL, Gibson PG, et al. (2009). An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 180, 59–99. 10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres RM, Souza MD, Coelho ACC, de Mello LM, and Souza-Machado C (2021). Association between Asthma and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Impact on Asthma Control-A Literature Review. CANADIAN RESPIRATORY JOURNAL 2021, 8830439. 10.1155/2021/8830439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein OL, Aviles-Santa L, Cai LW, Collard HR, Kanaya AM, Kaplan RC, Kinney GL, Mendes E, Smith L, Talavera G, et al. (2016). Hispanics/Latinos With Type 2 Diabetes Have Functional and Symptomatic Pulmonary Impairment Mirroring Kidney Microangiopathy: Findings From the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). DIABETES CARE 39, 2051–2057. 10.2337/dc16-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeryomenko GV, and Bezditko TV (2018). THE TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH ASTHMA AND COMORBIDITY. MEDICAL PERSPECTIVES-MEDICNI PERSPEKTIVI 23, 50–59. 10.26641/2307-0404.2018.1(part1).127209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holguin F, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Erzurum SC, Fitzpatrick AM, Gaston B, Israel E, Jarjour NN, et al. (2011). Obesity and asthma: An association modified by age of asthma onset. JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY 127, 1486–U1249. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu TD, Keet CA, Fawzy A, Segal JB, Brigham EP, and McCormack MC (2019). Association of Metformin Initiation and Risk of Asthma Exacerbation A Claims-based Cohort Study. ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY 16, 1527–1533. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-897OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li W, Wang Z, Chai YH, Qin Z, Jie G, Guan LC, Zhang MZ, Liu HQ, Yu HY, Wang QX, et al. (2020). Association of Metformin Use with Asthma Exacerbation in Patients with Concurrent Asthma and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. CANADIAN RESPIRATORY JOURNAL 2020, 9705604. 10.1155/2020/9705604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thuesen BH, Husemoen LLN, Hersoug LG, Pisinger C, and Linneberg A (2009). Insulin resistance as a predictor of incident asthma-like symptoms in adults. CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL ALLERGY 39, 700–707. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nie ZY, Jacoby DB, and Fryer AD (2014). Hyperinsulinemia Potentiates Airway Responsiveness to Parasympathetic Nerve Stimulation in Obese Rats. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY CELL AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY 51, 251–261. 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0452OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, and Lash TL (2008). Modern epidemiology (Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Philadelphia). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ge DR, Foer D, and Cahill KN (2023). Utility of Hypoglycemic Agents to Treat Asthma with Comorbid Obesity. PULMONARY THERAPY 9, 71–89. 10.1007/s41030-022-00211-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.