Abstract

Based on our previous study of the combination of sorafenib with 5-azacytidine (AZA) in relapsed/refractory patients with FLT3 mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML), we hypothesized that the combination would be efficacious and well tolerated in untreated patients with FLT3 mutated AML who are unsuitable for standard chemotherapy due to advanced age or lack of fitness. Newly diagnosed patients with untreated FLT3 mutated AML who underwent frontline therapy on 2 separate protocols of AZA plus sorafenib were analyzed. The clinical trials were registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02196857 and NCT01254890). Overall, 27 patients with untreated FLT3 mutated AML (median age of 74 years, range, 61–86) were enrolled. The overall response rate was 78% (7 [26%] CR, 12 [44%] CRi/CRp, and 2 [7%] PR). Patients received a median of 3 treatment cycles (1–35). The median duration of CR/CRp/CRi is 14.5 months (1.1–28.7 months). Three (11%) responding patients (1 CR, 2 CRi) proceeded to allogeneic stem cell transplant. The median follow-up for surviving patients was 4.1 months (3.0–17.3 months). The median overall survival for the entire group was 8.3 months, and 9.2 months in the 19 responders. The regimen was well tolerated in elderly patients with untreated FLT3 mutated AML with no early deaths.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

We have previously reported that the combination of sorafenib with 5-azacytidine (AZA) is safe and effective in patients with relapsed and/or refractory FLT3-ITD mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1 Thus, we hypothesized that this combination would be efficacious and well tolerated in untreated patients with AML who are not suitable for standard intense chemotherapy due to advanced age or lack of fitness. Newly diagnosed patients with untreated FLT3 mutated AML who underwent frontline therapy on 2 separate protocols of AZA plus sorafenib were included in this analysis. The clinical trials were registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT02196857 and NCT01254890.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Patient selection

Newly diagnosed patients with AML on the Phase II portion of the Phase I/II study NCT01254890 and the Phase II NCT02196857 were treated with the regimen of AZA and sorafenib. The patients from the first trial have been reported on previously.1 Patients were eligible for participation in the analysis if they had the FLT3-ITD mutation, age ≥ 60 years, ECOG performance status ≤ 2, and adequate organ function. Although the Phase II NCT02196857 trial allowed enrollment of patients younger than 60 years if they were unsuitable for standard cytotoxic chemotherapy, all patients treated were at least 60 years of age. The presence of the FLT3-ITD mutation was not a necessary inclusion criteria on the NCT01254890; however, the NCT02196857 required ≥ 10% FLT3-ITD burden.

Both studies required adequate hepatic function (serum total bilirubin ≤ 1.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN), alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase ≤ 2.5 × ULN and renal function (serum creatinine ≤ 1.5 × ULN). Both studies had the following exclusion criteria: malignant disease of the central nervous system, uncontrolled, hypertension, known history of congestive heart failure > NYHA class II, or advanced malignant hepatic tumors. The studies were approved by the University of Texas – MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board, and all participating patients signed an informed consent document in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 |. Treatment regimen

The regimen included AZA 75 mg/m2 daily × 7 days and sorafenib 400 mg twice daily as previously published.1 Cycles were repeated at approximately 1 month intervals until disease progression or development of intolerable toxicity that precluded continuation on the treatment. Dose adjustments for both sorafenib and azacytidine were allowed based on tolerability and presence of adverse events (AEs).

2.3 |. Laboratory correlative studies

Peripheral blood (PB) samples for plasma inhibitory assay (PIA) and FLT3 ligand (FL) levels were performed at the laboratory of Dr Mark Levis at Johns Hopkins University Medical Center. In vivo FLT3 inhibition was assessed using a surrogate ex vivo assay, the PIA assay, as previously described in.1,2 FL concentrations in plasma samples were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit obtained from R & D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN) as previously described in.3 Changes in the percentage of phosphorylated-FLT3 (%-P-FLT3) by densitometry during treatment were compared with baseline in leukemia cells from patients.

2.4 |. Response criteria

Complete response (CR) was defined as per revised working group criteria4 by ≤ 5% blasts in the bone marrow (BM) with PB demonstrating > 1 × 109/L neutrophils and 100 × 109/L platelets with no detectable extramedullary disease. Patients who met the above criteria but had neutrophil or platelet counts less than the stated values were considered to have achieved CRi (CR with incomplete recovery of PB counts). Partial response required all of the hematologic values for a CR but with a reduction of at least 50% in the percentage of blasts to 5%−25% in the BM aspirate. Relapse was defined by the recurrence of > 5% blasts in BM aspirate not related to count recovery or the development of extramedullary disease.

2.5 |. Statistical analysis

CR duration (CRD) was calculated from the time of achieving CR until relapse. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of initiation of treatment until death. Patients were censored at the time of last contact with health care professionals at our institution. Survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Differences in subgroups by different covariates were evaluated using the chi-square test for nominal values, and the Mann-Whitney U and Fischer’s exact test for continuous variables.

3 |. RESULTS

Overall, 27 patients with untreated AML (median age of 74 years; range, 61–86 years) were enrolled. The clinical characteristics of the patients are described in Table 1. A total of 17 (63%) patients had a normal karyotype, 2 (7%) had a complex karyotype, 4 (15%) had other miscellaneous abnormalities, and 4 (15%) had insufficient metaphases for analysis (Supporting Information Table S1). In addition to FLT3-ITD mutations being present in 100% of patients, 41% (n = 11) had NPM1 mutations, 22% (n = 6) had DNMT3A mutations, and 19% (n = 5) had IDH2 mutations. Other molecular mutations that were noted are shown in Supporting Information Table S1. Prior to the initiation of treatment, FLT3-ITD was detected in all patients with a median allelic ratio of 0.379 (range, 0.009–0.65).

TABLE 1.

Clinical data of patients treated with AZA plus sorafenib

| Patient characteristic | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74 | 61-86 |

| FLT3-ITD Burden | 0.379 | 0.009-0.65 |

| WBC (K/uL) | 5.7 | 0.3-93.1 |

| Platelets (K/uL) | 25 | 3-326 |

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 9.2 | 7.9-13.1 |

| Blasts (%) | 27 | 0-98 |

| LDH (U/L) | 1059 | 388-3921 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 | 0.2-2.9 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.83 | 0.48-1.77 |

| BM blasts (%) | 61 | 22-94 |

| BM Progranulocytes (%) | 1 | 0-17 |

| BM Monocytes (%) | 2 | 0-25 |

| BM Granulocytes (%) | 5 | 0-30 |

| PS | 1 | 0-2 |

| Courses to response | 2 | 1-5 |

| Total courses | 3 | 1-35 |

|

| ||

3.1 |. Elderly patients receiving AZA combined with sorafenib experienced favorable response rates

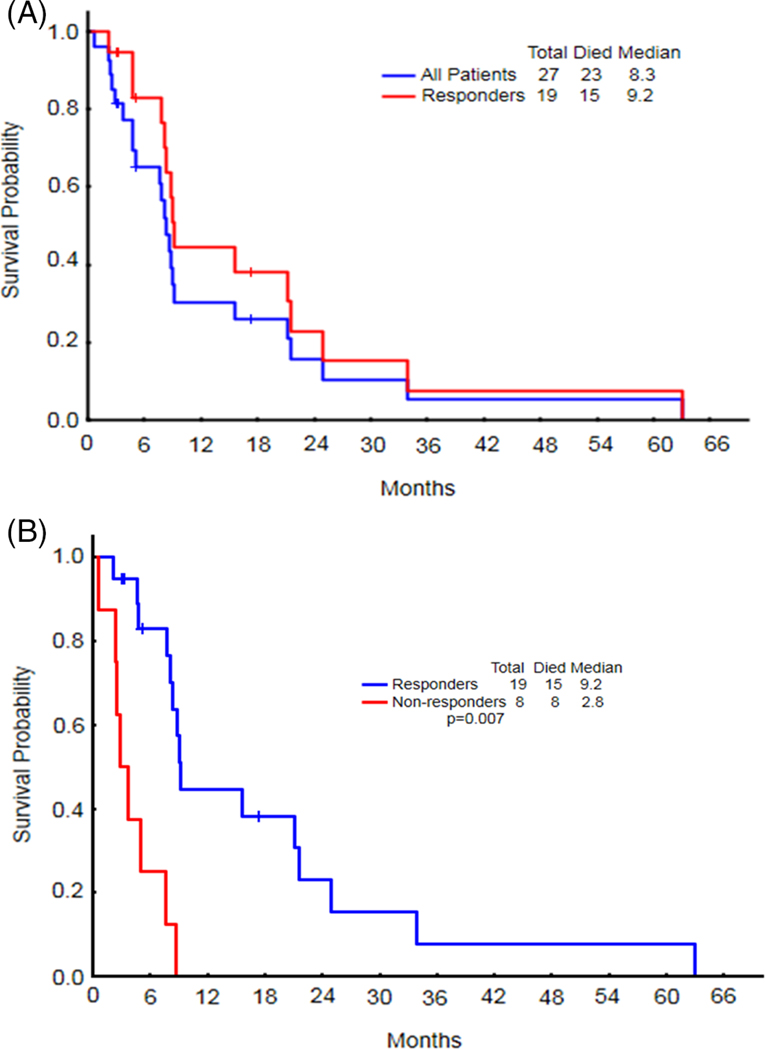

The overall response rate in the 27 evaluable patients was 78% (7 [26%] CR, 12 [45%] CRi/CRp, and 2 [7%] PR). Patients underwent a median of 3 (range, 1–35) treatment cycles. The median number of cycles to response was 2 (range, 1–5), and the median time to achieve response, 1.8 months (range, 0.62–4.96 months). Three (11%) responding patients (1 CR, 2 CRi) proceeded to allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT). Four patients remained alive at the time of this analysis, with a median follow-up of 4.1 months (range, 3.0–17.3 months). All 4 surviving patients had achieved CR/CRp/CRi; however, only 3 remained in remission at the time of analysis. The surviving patient who relapsed remained in CR for 14.7 months before relapse. The median overall survival (OS) was 8.3 months (range, 1–63 months) for the entire group and 9.2 months (range, 2–63 months) for the 19 responders (Figure 1A). As expected, the median OS in responders was significantly longer than for nonresponders (9.2 months [range, 2–63 months] vs. 2.8 months [range, 1–9 months]; P = .007) (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

A, The median OS for the entire group was 8.3 months, and 9.2 months in the 19 responders. B, The median OS in responders was significantly longer than for non-responders [Color figure can be viewed at wieyonlinelibrary.com]

Three patients stayed on this treatment even after relapsing and maintained disease control over an additional median period of 4 months after relapse (range, 2–12 months); thus, the maximum number of cycles received on study exceeded the maximal remission duration. Notably, 1 patient who achieved CRp after 3 cycles of AZA plus sorafenib relapsed 14.5 months later (after 17 cycles total), but remained on the treatment for another year, deriving continued clinical benefit during cycles 18–35. However, upon disease progression, this patient discontinued AZA plus sorafenib and subsequently received an investigational therapy for 3 months (with no response) before dying.

The median duration of CR/CRp/CRi was 14.5 months (range, 1.1–28.7 months) (Figure 2A). The median relapse-free survival duration, which was censored for loss of response/relapse and death while in CR, was 7.1 months (range, 1–29 months) (Figure 2B). There was no significant difference in FLT3-ITD burden between responders and nonresponders (P = .525).

FIGURE 2.

A, The median remission duration for the responding patients treated with AZA plus sorafenib (soraf) was 14.5 months (1.1–28.7). B, The median relapse-free survival, which censored for loss of response/relapse and death in CR, was 7.1 months (1–29) [Color figure can be viewed at wieyonlinelibrary.com]

3.2 |. AZA combined with sorafenib was well tolerated

Overall, the majority of AEs reported during the study were grade 1 or grade 2, as described in Figure 3. The most common grade 1/grade 2 AEs were hyperbilirubinemia (22%), diarrhea (22%), fatigue (22%), and nausea (19%). Among the grade 3/grade 4 AEs, infections (26%) and neutropenic fever (26%) were the most common (Figure 3). There were no early deaths within 14 days of the study.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of AEs reported during the clinical trial of AZA plus sorafenib. The majority of AEs were grades 1–2 [Color figure can be viewed at wieyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3 |. Forty-four percent of patients had secondary AML

In total 44% of patients (12/27) had secondary AML, either therapy-related AML (n = 4) or AML transformed from antecedent hematologic malignancy (n = 8). Eight patients had antecedent hematologic disorders, among which 4 had received prior treatment with hypomethylating agents: myelodysplastic syndrome (n = 1), refractory anemia with excess blasts (n = 3), myeloproliferative neoplasm (n = 1), MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasm (n = 1), essential thrombocytosis (n = 1), and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (n = 1).

3.4 |. Correlative data confirmed inhibition of FLT3 phosphorylation

Plasma from the indicated study days (Supporting Information Figure S1) from 3 evaluable subjects who volunteered for correlative studies was used in the plasma inhibitory activity assay for FLT3, as described previously.2 Inhibition of FLT3 phosphorylation was seen in all evaluable patients, as demonstrated by significant reductions in phosphorylated-FLT3 (%P-FLT3) by densitometry. In total, 2 out of 3 patients demonstrating significant inhibition of FLT3 phosphorylation achieved CR after cycle 1. Both of these responding patients underwent testing for %P-FLT3 at 2 time points; the first patient had inhibition of P-FLT3 by 97% (on day 7), and the second patient by 90% (on day 28). Although the third patient showed P-FLT3 inhibition by 98% on day 7 and 100% on day 28, he did not achieve a CR.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Older patients with FLT3-ITD-mutated AML have a worse outcome than those with wild-type FLT3. In patients older than 60 years of age with normal-karyotype AML who received standard front-line induction therapy on CALGB protocols, those with FLT3-ITD mutations had similar complete remission rates (P = .64) but shorter disease-free survival (P = .007) and OS (P < .001).5 When sorafenib was combined with 7 + 3 in patients ≥ 60 years of age, the observed 1-year OS was 62% (95% CI, 45%−78%) for the FLT3-ITD-mutated patients compared with 30% for a historical control group (P = .0001).6

Progress has been slow in improving outcomes for elderly patients with AML, particularly for elderly patients harboring FLT3-ITD mutations. Serve et al.7 previously reported no advantage over placebo when sorafenib was combined with daunorubicin and cytarabine in elderly patients with both mutated and wild-type FLT3. Higher rates of treatment-related mortality and lower CR rates occurred in the sorafenib arm. AEs events, particularly infections, were more common in the sorafenib arm. Furthermore, sorafenib was discontinued due to toxicity or patient refusal more often than the placebo.7 In contrast, the regimen of AZA plus sorafenib was well tolerated, with good patient compliance, and rarely required treatment interruptions or dose reductions. These observations and the fact that many elderly patients are not candidates for standard induction therapy suggest the need for less intensive yet effective regimens such as those combining target-specific drugs with epigenetic agents.

Given the significant toxicity observed in elderly patients receiving sorafenib in combination with standard chemotherapy reported by Serve et al.,7 lower-intensity combinations with sorafenib have been greatly needed, yet previous attempts to utilize sorafenib in combination with low-intensity therapy for elderly, unfit AML patients have been disappointing. For example, when sorafenib was combined with low-dose cytarabine in elderly patients with untreated high-risk MDS and AML (n = 21), an overall response rate of only 11.8% was observed.8 In contrast, our study, with an overall response rate of 78% and a median CRD of 14.5 months, suggests that the combination of AZA and sorafenib is both well tolerated and effective in older patients with untreated FLT3-ITD-mutated AML. The results demonstrated by this regimen are encouraging, particularly when considering that large studies of AZA monotherapy in elderly patients reported overall response rates of only 18.9%9-27.8%10 and median CRDs of 10.410-11.1 months.9 Furthermore, our study had a uniform population of FLT3-ITD-mutated patients and a larger proportion of higher-risk patients with secondary AML, thus reflecting an overall higher-risk group of patients.

Sorafenib has been previously combined with AZA,1 as well as with high-intensity regimens (idarubicin plus cytarabine11 and daunorubicin plus cytarabine6, and administered in the post-allo-SCT setting.12–14 A previous study conducted at our institution demonstrated that sorafenib combined with AZA was effective in relapsed and refractory FLT3-ITD-mutated AML patients of all ages (median, 64 years; range, 24–87 years).1 Thus, we hypothesized that this combination would be efficacious and well tolerated in untreated AML patients with FLT3-ITD mutations who are elderly or too deconditioned for standard intense chemotherapy.

Sorafenib is a multikinase inhibitor with significant FLT3 inhibitory effects,15 which are enhanced by standard chemotherapy in younger patients11 and hyopomethylating agents in AML patients of all ages.1 The combination of hypomethylating agents such as AZA or decitabine plus FLT3 inhibitors is based on a strong scientific rationale. Both FLT3 inhibitors and hypomethylating agents induce terminal differentiation of myeloid blasts and apoptosis. In vitro studies have shown synergistic effects between the 2 agents.16 Although increased FL levels is a common mechanism of resistance to FLT3 inhibitors, hypomethylating agents are associated with only minimal increases of the FL,1 which is a particularly complementary feature to FLT3 inhibitors. In vitro studies suggest that AZA combined with the FLT3 inhibitor quizartinib was significantly more cytotoxic than equimolar concentrations of decitabine with quizartinib, in terms of growth inhibition and apoptosis of FLT3-ITD-mutated AML cells both in the presence and absence of stroma, thus providing a rationale for the combination of AZA and sorafenib,16 One possible explanation for this is that in contrast to decitabine being solely incorporated into DNA, AZA results in enhanced incorporation into RNA, and thus AZA results in increased interference with protein synthesis. Additionally, in vitro studies of patient samples showed that differentiating effects of AZA were more prominent than those of decitabine, providing further support for this regimen. Notably, marked myeloid differentiation with AZA plus sorafenib has also been observed clinically, manifesting as a neutrophil surge followed by loss of FLT3 expression over time.16

Multiple studies demonstrated the clinical benefit of sorafenib as post-allo-SCT maintenance therapy in FLT3-ITD-mutated AML patients.12–14 Furthermore, the combination of AZA plus sorafenib has also demonstrated benefit in the context of post-transplantation relapse.17,18 In 1 series (n = 8) of FLT3-ITD-mutated AML patients with early proliferative relapse (within a median of 91 days) after allo-SCT, AZA plus sorafenib was administered. The CR rate was 50%, with a median duration of 182 days (range, 158–496 days).18 These observations raise the question of whether FLT3-ITD-mutated AML patients who do not have SCT options could receive AZA plus sorafenib as a continuous maintenance regimen in lieu of SCT, which would be particularly relevant for elderly patients who generally are not candidates for SCT.

A limitation of our study is the small sample size; however, this reflects the fact that fewer elderly patients harbor FLT3-ITD mutations at diagnosis.19–21 For example, Uy et al.6 screened 474 untreated AML patients ≥ 60 years of age, and only 62 (13%) had the FLT3-ITD mutation, among which only 39 (8%) were candidates for standard induction therapy. Similarly, at our institution between 2000 and 2016, among 1357 untreated AML patients ≥ 60 years of age (range, 60–92 years) who were tested for FLT3-ITD mutations, only 195 (14%) harbored mutated FLT3-ITD. Nonetheless, the lack of options for older patients with mutated FLT3-ITD is an unmet medical need.

Due to the small sample size and the high-risk nature of the patient population, the median follow-up for the small number of surviving patients (n = 4) was only 4.1 months (range, 3.0–17.3 months). Based on the encouraging findings observed with AZA plus sorafenib in unfit, elderly FLT3-ITD-mutated patients with AML, larger randomized studies are required to fully understand the potential benefit of this regimen in the elderly. While longer follow-up and larger patient numbers are needed to better understand whether AZA plus sorafenib could improve survival, the safety and tolerability of this regimen, with no early deaths in our study, offer the opportunity to combine other targeted agents that are currently benefiting elderly patients with AML (eg, venetoclax)22 with this regimen to further enhance its benefits.

Supplementary Material

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

FR received research funding and honoraria from Onyx/Bayer and Celgene. JC received research funding from Celgene.

Funding information

Onyx/Bayer and Celgene

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ravandi F, Alattar ML, Grunwald MR, et al. Phase 2 study of azacytidine plus sorafenib in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and FLT-3 internal tandem duplication mutation. Blood. 2013;121:4655–4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levis M, Brown P, Smith BD, et al. Plasma inhibitory activity (PIA): a pharmacodynamic assay reveals insights into the basis for cytotoxic response to FLT3 inhibitors. Blood. 2006;108:3477–3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato T, Yang X, Knapper S, et al. FLT3 ligand impedes the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2011;117:3286–3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheson BD, Cassileth PA, Head DR, et al. Report of the National Cancer Institute-sponsored workshop on definitions of diagnosis and response in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitman SP, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, et al. FLT3 internal tandem duplication associates with adverse outcome and gene- and microRNA-expression signatures in patients 60 years of age or older with primary cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood. 2010;116:3622–3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uy G, Mandrekar S, Laumann K, et al. A phase 2 study incorporating sorafenib into the chemotherapy for older adults with FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: CALGB 11001. Blood Adv. 2017;1:331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serve H, Krug U, Wagner R, et al. Sorafenib in combination with intensive chemotherapy in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:3110–3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macdonald DA, Assouline SE, Brandwein J, et al. A phase I/II study of sorafenib in combination with low dose cytarabine in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome from the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group: trial IND.186. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:760–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pleyer L, Dohner H, Dombret H, et al. Azacitidine for Front-Line Therapy of Patients with AML: Reproducible Efficacy Established by Direct Comparison of International Phase 3 Trial Data with Registry Data from the Austrian Azacitidine Registry of the AGMT Study Group. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dombret H, Seymour JF, Butrym A, et al. International phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with >30% blasts. Blood. 2015;126:291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravandi F, Arana Yi C, Cortes JE, et al. Final report of phase II study of sorafenib, cytarabine and idarubicin for initial therapy in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28:1543–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antar A, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Mahfouz R, et al. Sorafenib Mainte-nance Appears Safe and Improves Clinical Outcomes in FLT3-ITD Acute Myeloid Leukemia After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15:298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Battipaglia G, Ruggeri A, Massoud R, et al. Efficacy and feasibility of sorafenib as a maintenance agent after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2017;123:2867–2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarlock K, Chang B, Cooper T, et al. Sorafenib treatment following hematopoietic stem cell transplant in pediatric FLT3/ITD acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1048–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, et al. BAY 43–9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang E, Ganguly S, Rajkhowa T, et al. The combination of FLT3 and DNA methyltransferase inhibition is synergistically cytotoxic to FLT3/ITD acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2016;30:1025–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Freitas T, Marktel S, Piemontese S, et al. High rate of hematological responses to sorafenib in FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia relapsed after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur J Haematol. 2016;96:629–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rautenberg C, Nachtkamp K, Dienst A, et al. Sorafenib and azacitidine as salvage therapy for relapse of FLT3-ITD mutated AML after allo-SCT. Eur J Haematol. 2017;98:348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Alo F, Fianchi L, Fabiani E, et al. Similarities and differences between therapy-related and elderly acute myeloid leukemia. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2011;3:e2011052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai CH, Hou HA, Tang JL, et al. Genetic alterations and their clinical implications in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:1485–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beran M, Luthra R, Kantarjian H, et al. FLT3 mutation and response to intensive chemotherapy in young adult and elderly patients with normal karyotype. Leuk Res. 2004;28:547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiNardo CD, Pratz KW, Letai A, et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy of venetoclax with decitabine or azacitidine in elderly patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukaemia: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;191:216–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.