Abstract

Acute sleep deprivation (SD) rapidly alleviates depression, addressing a critical gap in mood disorder treatment. Rapid eye movement SD (REM SD) modulates the excitability of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) neurons, influencing the synaptic plasticity of pyramidal neurons. However, the precise mechanism remains undefined. To investigate this, we used a modified multiple platform method (MMPM) to induce 12 hours of REM SD, specifically targeting VIP neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Our results show that REM SD mitigated depression by suppressing VIP neurons activity, which directly increased the excitability of pyramidal neurons and, consequently, promoted synaptic plasticity recovery. In addition, the knockdown of VPAC2 on mPFC pyramidal neurons revealed that VPAC2-mediated AC/cAMP/PKA signaling pathway in these neurons is essential for REM SD to mitigate depression-like behavior. These findings suggest that VIP neurons directly regulate pyramidal neurons and are crucial in alleviating depression by REM SD.

Acute REM sleep deprivation alleviates depression by VIP neurons to enhance the synaptic plasticity of mPFC pyramidal neurons.

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a recurring illness with diverse causes (1), substantially affecting physical and emotional well-being. It increases the risk of self-harm, hinders social interactions, and worsens existing conditions (2, 3). Dysfunction in synaptic plasticity is a primary mechanism in MDD (4). Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) neurons are crucial for mood regulation (5–7) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (8). Furthermore, REM sleep influences the development and elimination of dendritic spines, synaptic plasticity, and memory consolidation (9, 10). Although REM sleep deprivation (REM SD) alters synaptic plasticity (11), the role of VIP neurons in this process and the underlying mechanism remain elusive. Understanding the regulation of VIP neuron microcircuits underlying depression-like behaviors is essential for elucidating mechanisms and developing new treatment approaches.

Sleep constitutes a notable portion of our existence, consisting of two main stages: REM sleep and non-REM (NREM) sleep (12–14). Some studies indicate that the ability of the brain to remove waste products diminishes during REM sleep, a process potentially disrupted by SD (15). SD is a potent antidepressant, showing responses within hours in many patients with depression (16). Thus, REM SD is an ideal experimental paradigm to strengthen the synaptic plasticity of pyramidal neurons.

Furthermore, the VIP neurons, vital in the central nervous system (CNS), regulate circadian rhythms (17, 18). VIP regulates synaptic plasticity through modulation of the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor type 2 (VPAC2) receptor (19), influencing synaptic capacity (20). VPAC2 receptor activation is primarily linked to the modulation of transmission to the pyramidal neuron soma (21–23). In this study, we used behavioral tests, Golgi staining, Western blotting, and long-term potentiation (LTP) to investigate how REM SD alleviates depression by enhancing synaptic plasticity. We assessed the necessity of VIP neurons in the mPFC for the antidepressant effects of REM SD using Ca2+ signals, chemogenetic manipulations, and G protein–coupled receptor activation–based (GRAB) probes. Furthermore, we used a viral-mediated short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown strategy to target VPAC2 on pyramidal neurons within the mPFC, clarifying its role in synaptic plasticity via the adenylyl cyclase (AC)/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway alterations associated with REM SD in alleviating depression.

RESULTS

12-hour acute REM SD alleviates depression-like behavior

In this study, we subjected male C57BL/6J mice to the chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) paradigm, a well-established model for inducing depression-like conditions (24, 25). The next day, these mice underwent 12 hour of REM SD, followed by behavioral tests (Fig. 1A). Open field tests (OFTs)—analyzed through trajectory, heat, and activity maps—revealed that CUMS decreased the distance mice traveled in the central area of the open field, a behavior alleviated by REM SD (Fig. 1, B and F). Compared to the CUMS group, REM SD also reduced immobility periods in the tail suspension test (TST) and forced swim test (FST) and elevated sucrose preference in the sucrose preference test (SPT) (Fig. 1, C to E). Subsequently, we explored the effects of REM SD on depressive female mice. The results showed that, consistent with male mice, REM SD also alleviated depression-like behaviors in female mice (fig. S5, M to Q).

Fig. 1. Twelve-hour acute REM SD alleviated depression-like behavior.

(A) Schematic of experimental approach and timeline. (B) Left: Summary data of the distance traveled in OFT. n = 8 mice (CON) and n = 7 mice (CUMS and REM SD). Right: Summary data of the distance traveled in the central zone. n = 8 mice (CON) and n = 7 mice (CUMS and REM SD). (C) Top: Schematic of the conditions for SPT. Bottom: Summary data of the percentage of sucrose preference by volume consumed in SPT. n = 8 mice (CON) and n = 7 mice (CUMS and REM SD). (D) Top: Schematics of the conditions for TST. Bottom: Summary data of the immobility time (s) in TST. n = 7 mice (CON and CUMS) and n = 8 mice (REM SD). (E) Top: Schematics of the conditions for FST. Bottom: Summary data of the immobility time (s) in FST. n = 7 mice (CON and CUMS) and n = 8 mice (REM SD). (F) Left: Representative trajectory map patterns of moving paths of mice in OFT. Middle: Representative heatmap patterns of moving paths of mice in OFT. Right: Representative activity map patterns of moving paths of mice in OFT. Data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test. ns, not significant.

Our previous study indicated that 24 hours of REM SD increased dendritic spines in mice, prompting the assessment of the sleep gradient (11). To comprehensively investigate the impact of shorter (6 hours) or longer (18 hours) REM SD on depression, we exposed CUMS-induced depressed mice to these durations and conducted behavioral tests. Neither 6 nor 18 hours of REM SD affected the mice’s locomotor capacity during the OFT (fig. S1, A to C, and D). However, both durations significantly decreased the distance traveled in the center of the OFT (fig. S1E). In the elevated plus maze test, 12 hours of REM SD reduced anxiety-like behavior in line with the control (CON) group (fig. S1, G and H). In contrast, the REM SD 6-hour group exhibited decreased sucrose preference and increased immobility (fig. S1, F and I to J). These findings demonstrate that only 12 hours of REM SD effectively alleviates depression-like behaviors without inducing anxiety-like behaviors. We also examined whether the 12-hour REM SD paradigm caused abnormal behavior in normal mice, finding no statistically significant difference between the CON group and the CON + REM SD group in the OFT, SPT, TST, and FST (fig. S1K).

Afterward, we monitored behavioral changes for 1 week following 12 hours of REM SD. Five days post–REM SD, the mice showed a reduction in the distance covered in the center region of the open field, decreased sucrose preference, and increased immobility (fig. S1, L to Q).

Recovery of synaptic plasticity following REM SD

We used Golgi staining to quantitatively assess alterations in dendritic complexity, dendritic spine density, and morphology within the mPFC, thereby confirming its structural plasticity (Fig. 2A). By conducting concentric circle (Sholl) analysis, we found that dendritic complexity, spine generation, mushroom spines ratio, and thin spines ratio significantly decreased in the CUMS group compared to the CON group. Substantially, REM SD reversed these effects, indicating augmented synaptic plasticity in mPFC (Fig. 2, B to H). Similarly, the stubby spines ratio significantly increased in the CUMS group, implying a reduction in interneural connectivity, an effect also eliminated by REM SD (Fig. 2G). Compared with the CON group, 18 hours of REM SD enhanced the dendritic complexity of the mPFC and the density of dendritic spines, while 6 hours of REM SD exhibited a reduction (fig. S2, A to C). In the case of mushroom spines, REM SD for 6, 12, and 18 hours rarely influenced their ratio but did affect their density (fig. S2, D to E). The results indicated that 6 hours of REM SD limitedly affected synaptic plasticity, whereas 18 hours substantially enhanced it. We also explored the potential effects of REM SD on synaptic plasticity in normal mice. No significant variations in dendritic complexity and dendritic spine density were observed between the CON + REM SD and CON groups (fig. S2, F to H). Compared to the CON group, REM SD decreased the stubby spines ratio and increased the thin spines ratio in normal mice but had no significant effect on mushroom spines (fig. S2, I to K).

Fig. 2. Recovery of synaptic plasticity following REM SD.

(A) Schematics of the timeline of behavioral test and Golgi staining. (B) Top: Representative images of neuron tracing plots and Sholl analysis. Bottom: Quantification of dendritic intersection in the mPFC. n = 12 neurons from four mice (CON) and n = 10 neurons from four mice (CUMS and REM SD). (C) Summary of all intersections of a single neuron from (B). (D) Left: Representative Golgi staining showing dendritic branches in the mPFC. Scale bars, 50 μm. Right: Representative images of secondary dendritic spines in the mPFC. Scale bars, 2 μm. (E) Top: Schematics of the dendritic spine types. Bottom: Quantification of total dendritic spine density in mPFC. n = 26 dendrites from four mice (CON and CUMS) and n = 27 dendrites from four mice (REM SD). (F to H) Quantification of the ratio of spine type in the mPFC dendritic spine: mushroom (F), stubby (G), thin (H). n = 26 dendrites from four mice (CON and CUMS) and n = 27 dendrites from four mice (REM SD). (I) Representative Western blots images. (J) Quantification of GluA1, p-GluA1, GluA2, and p-GluA2 levels expressed as the ratio of the CON groups. n = 4 mice per group for GluA1, GluA2, and p-GluA2. n = 3 mice per group for p-GluA1. (K) Representative field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) in different groups. The black trace represents fEPSP before theta burst stimulation (TBS) stimulation. The red trace represents fEPSP after TBS stimulation. Scale bars, 1 mV, 30 ms. (L) Time course of changes in fEPSPs slopes under different treatments. n = 4 mice per group. (B) Data are presented as means ± SEM, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. [(C) to (K)] Data are presented as means ± SEM, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

We then investigated whether this intervention similarly affected other brain regions beyond the medial PFC (mPFC). Brain regions linked to depression were thus tested, such as cg1 (anterior cingulate cortex) and CA1 in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus (25, 26). We individually examined alterations in the apical and basal dendrites of CA1 (fig. S3, C to H and S4, F to M). Findings indicated that both brain areas recovered normal function following REM SD, aligning with the CON group (figs. S3 and S4), suggesting that REM SD affects not only the mPFC but also the cg1 and CA1, both critical mood centers related to depression (27, 28). At the molecular level, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor subunit glutamate receptor 1 (GluA1) and phosphorylated GluA1 (p-GluA1) decreased in the mPFC of CUMS group, while the REM SD abolished the decrease. No statistically significant change was observed in GluA2 in the CON, CUMS, and REM SD groups (Fig. 2, I and J). Given that the increased expression of phosphorylated GluA2 (p-GluA2) leads to attenuated AMPA receptor transmission (29), we further investigated the function of p-GluA2 in REM SD. The results showed that the expression of p-GluA2 was increased in the CUMS group compared with the CON group. In contrast, the expression of p-GluA2 was restored to no difference with the CON group after REM SD (Fig. 2J). Because REM SD is essential for changes in synaptic plasticity, we recorded LTP induced by theta burst stimulation (TBS). In the mPFC following REM SD, TBS induced synapse-dependent LTP (Fig. 2, K and L), revealing that REM SD enhances functional synaptic plasticity.

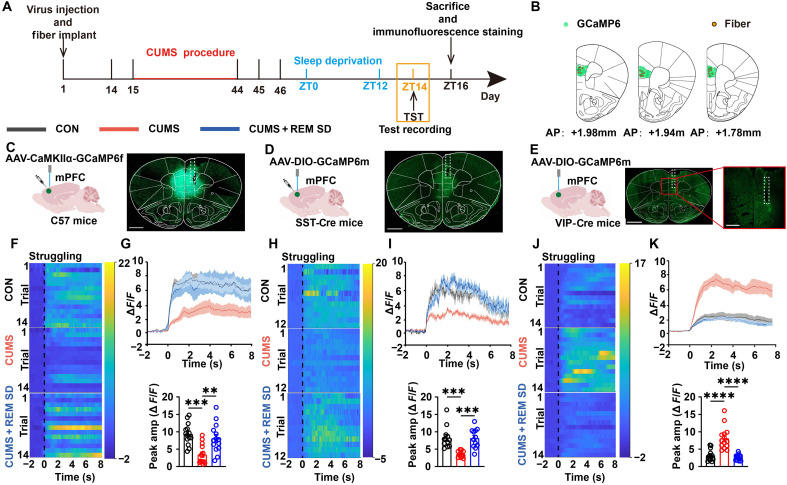

REM SD reduces the facilitative influence of VIP neurons in the mPFC on depression-like behavior

To investigate the activity of different neurons in mPFC during depression alleviation by REM SD, we used fiber photometry to record calcium signals for struggling events from pyramidal, somatostatin (SST), and VIP neurons during the TST (Fig. 3A). We injected either adeno-associated virus (AAV)–expressing GCaMP6f under the CaMKIIα promoter into the mPFC of C57 mice or AAV-expressing Cre-inducible GCaMP6s into the dorsomedial PFC (dmPFC) of SST-Cre or VIP-Cre mice (Fig. 3, B to E). Pyramidal neurons were inactive during CUMS and recovered during REM SD (Fig. 3, C, F, and G). We explored the changes in SST neurons in mPFC. The results showed that CUMS decreased the activity of SST neurons and returned to consistency with the CON group after REM SD (Fig. 3, D, H, and I). VIP neurons, in contrast, showed significantly increased activity during CUMS and a restoration of activity during REM SD (Fig. 3, J and K). Given known sex differences in the pathophysiology of depression and synaptic plasticity mechanisms, we applied similar treatment conditions to VIP-Cre female mice as male mice (30, 31). The observed alterations in VIP-Cre female mice aligned with those in male mice (fig. S5, A to C). To assess alterations in neuronal activity in the mPFC, we measured the expression level of c-fos protein using immunofluorescence staining. In comparison to the CUMS group, REM SD restored c-fos expression in pyramidal and SST neurons (fig. S6, A to D). However, REM SD distinctly decreased c-fos expression in VIP neurons (fig. S6, E, and F). Calcium signaling and immunofluorescence staining results showed that in the CUMS group, VIP neurons were excited, while SST and pyramidal neurons were weakened, REM SD restored them all. Because VIP neurons selectively inhibit other inhibitory neurons, which then inhibit pyramidal cells (32), the present study focused on VIP neurons.

Fig. 3. Different types of mPFC neurons were recruited during struggling in the TST.

(A) Schematics of TST timeline and immunofluorescence staining. (B) Fiber placement in coronal brain sections registered to the common coordinate framework, one to two sections for each animal. (C) Viral injection schematic (left) and representative GCaMP6f expression image in the mPFC were taken from C57 mice. Scale bar, 1 mm. (D and E) Viral injections schematic (left) and representative GCaMP6m-expression image in the mPFC was taken from SST-Cre mice (D) or VIP-Cre mice (E). Scale bars, 1 mm [(D) and (E), left]. Scale bar, 500 μm ([(E), right]. (F, H, and J) Heatmaps of ΔF/F illustrating the Ca2+ signals in mPFC pyramidal, SST, and VIP neurons during the struggling events when C57 mice (F), SST-Cre mice (H), or VIP-Cre mice (J) occurred in TST. Time 0 represents the time at which the struggling events occurred during TST. n = 14 trials from seven mice per group [(F) and (J)]. n = 12 trials from six mice per group (H). (G, I, and K) Top: Peri-event plots of ΔF/F Ca2+ signals in mPFC pyramidal (G), SST (I), and VIP (K) neurons during the struggling events in TST. The solid line and the shaded regions are the means ± SEM. n = 14 trials from seven mice per group [(G) and (K)]. n = 12 trials from six mice per group (I). Bottom: Compared the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signals of mPFC pyramidal (G), SST (I), and VIP (K) neurons when the struggling events occurred during TST. Data are presented as means ± SEM. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

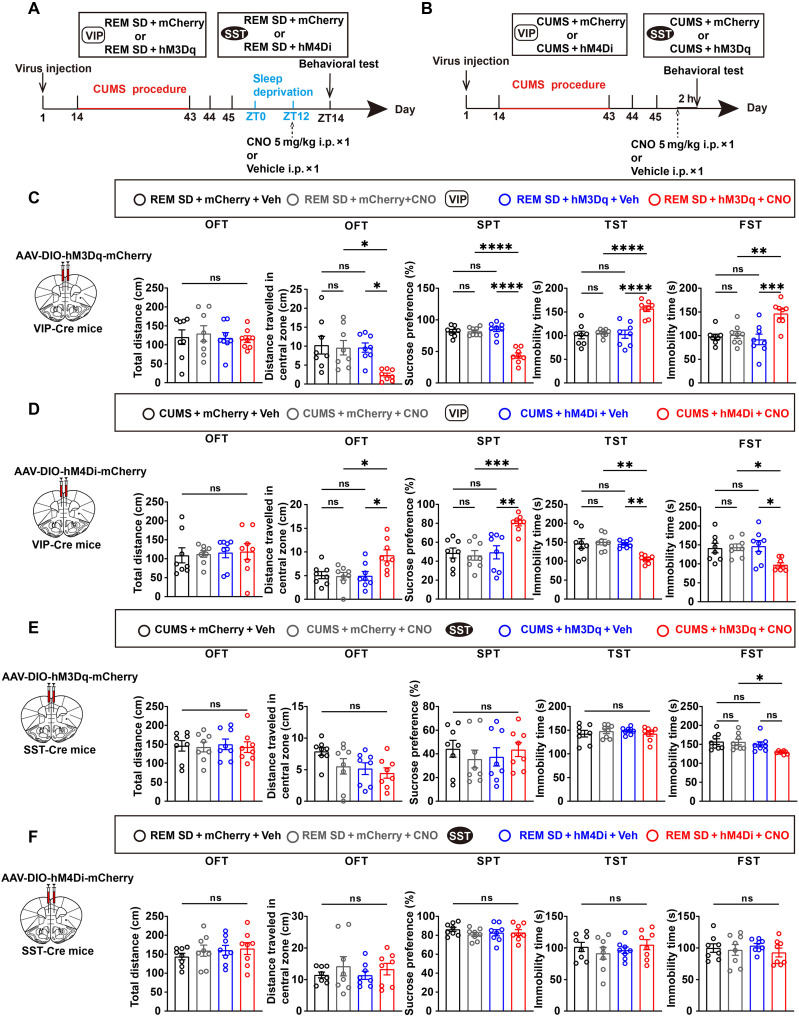

Chemogenetic inhibition of VIP neurons prevents depression-like phenotypes

To understand which interneurons were involved in this regulatory process, given that REM SD affected VIP and SST neurons. Initially, inhibitory or activating designer receptors, exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs), were used, specifically hM4Di or hM3Dq, to target and either block or activate VIP or SST neuron activity in the mPFC (33). Controls included mCherry viruses lacking chemogenetic components. Behavioral tests were conducted 2 hours after administering a dose of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO; 5 mg/kg i.p.) (Fig. 4, A and B). CNO activation increased immobility, decreased distance traveled in the center, and reduced sucrose preference in depressed VIP-Cre mice expressing hM3Dq in the mPFC after REM SD but did not affect mice’s locomotor capacity during the OFT (Fig. 4C). Next, the possibility of mitigating depression-like behavior was explored by inhibiting VIP neurons in the mPFC. The chemogenetic suppression of depressed VIP neurons in the mPFC increased the distance traveled in the central region during OFT, heightened sucrose preference in the SPT, and reduced the immobility in the TST and FST (Fig. 4D). The findings suggest that activating VIP neurons in the mPFC reverted mice experiencing REM SD to depression, while inhibiting these neurons alleviated depression-like phenotypes.

Fig. 4. Chemogenetic inhibition of VIP neurons prevents depression-like phenotypes.

(A and B) Experimental design for hM3Dq-DREADD or hM4Di-DREADD validation after REM SD (A) or CUMS (B). (C and D) Left: Schematic of the bilateral viral transduction in VIP-Cre mice. Veh, vehicle. Right: Summary data of animal behaviors in OFT, SPT, TST, and FST. n = 8 mice per group. (E and F) Left: Schematic of the bilateral viral transduction in SST-Cre mice. Right: Summary data of animal behaviors in OFT, SPT, TST, and FST. n = 8 mice per group. Data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

We also investigated the impact of SST neurons. Notably, chemogenetic activating SST neurons in the mPFC in depressive mice only reduced immobility duration during the FST, but no significant change was observed in the OFT, SPT, and TST (Fig. 4E). Inhibiting SST neurons after REM SD showed no significant changes across the OFT, SPT, TST, or FST (Fig. 4F). As mentioned earlier, our findings indicated that activating VIP neurons alone restored mice to a depressed state, while activating SST neurons seldom produced the same effect.

Chemogenetic manipulation of VIP neurons affects glutamate and somatostatin release

To address the chemogenetic manipulation of mPFC VIP neurons, their influence on network activity within the mPFC was explored. In addition to analyzing struggling events in the TST associated with depression, alterations in minor behaviors, such as climbing events during the OFT, were investigated, considering the complexity of neurotransmitter release (Fig. 5, B to C). Furthermore, fluorescence changes during the behavioral tests were monitored by expressing GRABglutamate [abbreviated as GRABglu, glutamate receptor–based neurotransmitter sensors; GRAB, G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) activation-based] in the mPFC (Fig. 5A). The findings revealed that suppressing VIP neurons during depression increased GRABglu amplitude (Fig. 5, D and E). Conversely, activating VIP neurons in the mPFC after REM SD markedly decreased GRABglu amplitude (Fig. 5, F and G). VIP-Cre female mice were used to eliminate potential sex-based differences in the modulation of VIP neurons, and the findings for female mice matched those observed in male mice (fig. S5, D to H). We observed alterations in glutamatergic neurotransmitter levels associated with climbing behavior in the OFT using adult VIP-Cre male and female mice. Inhibition of VIP neurons during depression substantially enhanced glutamatergic neurotransmitter release in both male and female mice. After REM SD, activating VIP neurons substantially reduced glutamate neurotransmitter release (Fig. 5, H to K, and fig. S5, I to L).

Fig. 5. In the TST and OFT, chemogenetic manipulation of VIP neurons affects glutamate signaling.

(A) Left and middle: Viral injections schematic. Right: Climbing behavior schematic in OFT. (B and C) Schematics of TST or OFT timeline. (D and F) Heatmaps of ΔF/F illustrate glutamate release in the mPFC following chemogenetic inhibition (D) and activation (F) of VIP neurons during the struggling events in TST. Time 0 represents the time at which the struggling events occurred. n = 10 trials from four mice per group. (E and G) Top: Peri-event plots of ΔF/F glutamate levels change from mPFC neurons after chemogenetic inhibition (E) and activation (G) of mPFC VIP neurons during the struggling events in TST. The solid line and the shaded regions are the means ± SEM. Bottom: Compare the peak amplitude of the glutamate levels when the struggling events occurred in VIP-Cre mice. n = 10 trials from four mice per group. (H and J) Heatmaps of ΔF/F illustrate glutamate release in the mPFC following chemogenetic inhibition (H) and activation (J) of VIP neurons during the climbing events in OFT. Time 0 represents the time at which the climbing events occurred. n = 10 trials from four mice per group. (I and K) Top: Peri-event plots of ΔF/F glutamate levels change from mPFC neurons after chemogenetic inhibition (I) and chemogenetic activation (K) of mPFC VIP neurons during the climbing events in OFT. The solid line and the shaded regions are the means ± SEM. Bottom: Compare the peak amplitude of the glutamate levels when the climbing events occurred in VIP-Cre mice. n = 10 trials from four mice per group. Data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001; unpaired t test.

We also inquired about the potential impact of modulating VIP neurons in the mPFC on GRABsomatostatin [abbreviated as GRABsst, somatostatin receptors-based neurotransmitter sensors] (fig. S7A). Activating VIP neurons in the mPFC following REM SD reduced somatostatin levels, while inhibiting them during depression increased these levels (fig. S7, B to E). This indicated that VIP neurons mediated the previously observed shifts in the excitability of pyramidal and SST neurons in the mPFC after REM SD. We used a similar strategy to the CNO administration approach in the TST to investigate alterations in GRABsst within the OFT (fig. S7, F to I). The results indicated that inhibiting VIP neurons during depression elevated somatostatin release, whereas activating VIP neurons following REM SD reduced somatostatin release. These findings demonstrated that the antidepressant properties of REM SD depend on VIP neurons in the mPFC.

VIP neurons modulate VPAC2 receptors located on pyramidal neurons, the major targets of REM SD for alleviating depression

We aimed to determine which of the two VIP-related receptors (VPAC1 or VPAC2) is involved in REM SD’s ability to mitigate depression (34). It was established that CUMS elevated VPAC2 expression compared to the CON group, while REM SD restored it; VPAC1 showed no significant changes (Fig. 6A). To further verify whether VPAC2 regulates depression alleviation by REM SD, we specifically knocked down VPAC2 expression in mPFC pyramidal neurons. Mixed AAV-CaMKIIa-CRE and AAV-DIO-mCherry-Vipr2 shRNA or mixed AAV-CaMKIIa-CRE and AAV-DIO-mCherry-scramble shRNA were injected into the mPFC (Fig. 6B). It was demonstrated that virus-mediated VPAC2shRNA expression led to a reduction in VPAC2 expression in a Cre-dependent manner. Substantially, VPAC2 mediates various functions via intracellular signaling pathways, including PKA (19), phospholipase C (35), and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) (36). Following REM SD, the functional knockdown of VPAC2 on VIPCre+/AAV male and female mice, compared to the scrambled group, led to a reduction in the expression of the AC/cAMP/PKA signaling pathway linked to p-GluA1 in the mPFC (Fig. 6, C and D). However, compared to the scramble group, knocking down VPAC2 decreased the expression of p-GluA1 and increased the expression of p-GluA2 (Fig. 6, C and D). To determine if VPAC2 on SST neurons influences depression remission via REM SD, we targeted knockdown of VPAC2 expression in SST neurons inside the mPFC. The research findings indicate that, compared to the REM SD group, knocking down the VPAC2 receptors on SST neurons in the mPFC did not result in any significant changes in the OFT, SPT, FST, and TST (fig. S8). Knockdown in VIPCre+/AAV male and female mice resulted in a reduction of dendritic spine density and an increase in depression-like behavior compared to the scrambled group (Fig. 6, E to H). These results suggested that the VPAC2 receptor controlled the primary molecular target of REM SD for the relief of depression.

Fig. 6. VIP neurons modulate VPAC2 receptors located on pyramidal neurons, the major targets of REM SD for alleviating depression.

(A) Left: Representative Western blots images. Right: Quantification of the VPAC1 and VPAC2 levels expressed as a ratio of CON group. n = 4 mice per group. (B) Left: Schematic of the bilateral viral transduction in C57 mice. Right: Representative images of the knockdown of VPAC2 in pyramidal neurons. Scale bars, 50 μm. (C and D) Left: Representative Western blots images. Right: Quantification of the p-GluA1, p-GluA2, VPAC2, AC, and PKA levels expressed as a ratio of CON group. n = 5 mice per group (p-GluA1). n = 6 mice per group (VPAC2, p-GluA2, AC, and PKA). (E and F) Summary data of animal behaviors in OFT, SPT, TST, and FST. n = 8 mice per group. (G and H) Top: Representative secondary dendritic spines from mPFC in each group of mice. Scale bars, 2 μm. Bottom: Quantification of total dendritic spine density and the ratio of spine type in the mPFC dendritic spine: mushroom, stubby, and thin. n = 10 dendrites from four mice per group. Data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; unpaired t test. KD, knockdown.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicated that REM SD alleviated depression-like behavior by modulating the VPAC2 mediated by VIP neurons. Experimental data demonstrated that REM SD increased spine formation and maturation, facilitating synaptic transmission, a phenomenon blocked by viral-mediated shRNA knockdown of VPAC2 on pyramidal neurons. Although VPAC (VPAC1 and VPAC2) receptors mediated by VIP neurons modulate synaptic plasticity (22), VPAC2 receptor overactivity disrupts it (19). Our findings provided molecular evidence that REM SD decreased p-GluA2 and VPAC2 expression while enhancing GluA1 and p-GluA1 expression (Figs. 2 and 6). Together, these results confirm that VPAC2 is essential for VIP neurons in regulating synaptic plasticity in pyramidal neurons. We initially identified that VPAC2 regulated mPFC pyramidal neuronal excitability through AC/cAMP/PKA pathways in mPFC, further emphasizing the role of VPAC2 in the antidepressant effect of REM SD (Fig. 6). Previous studies indicated that the activation of the AC/cAMP/PKA signaling pathway correlated with dendritic growth induced by the VPAC2 receptor (19). In addition, PKA directly interacted with CREB, influencing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (37, 38) expression levels across various depression models, thereby affecting neuroplasticity. Recent reports highlighted the pivotal role of BDNF in depression pathophysiology. BDNF exerts its effects through multiple signaling pathways, including: (i) in the tropomyosin-related kinase receptor B (TrkB) signaling pathway, Akt plays an important role in the process of neurogenesis under the action of BDNF (39); (ii) BDNF exerts neuroprotective effects through the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway, ultimately restoring synaptic transmission and ameliorating depression-like behavior (40–42); and (iii) BDNF and Wnt cooperatively regulate dendritic spine formation and alleviate depression (43, 44). Consequently, REM SD may contribute to the alleviation of depression through its impact on the PKA/CREB/BDNF signaling pathway.

The activity of VIP neurons was higher during REM sleep than in NREM (45). Although most prior studies found a disinhibition of REM sleep (shorter REM latency and increased REM sleep time) in patients with depression (46), our data showed that REM SD down-regulated c-fos expression and Ca2+ signal in VIP neurons of depressive mice (Fig. 3 and fig. S6). Chemogenetics activation of VIP neurons after REM SD exhibited depression-like behavior and led to decreased GRABglu and GRABsst signaling (Fig. 5). In contrast, chemogenetic inhibition of VIP neurons in the CUMS state relieved depression-like behavior and led to increased GRABglu and GRABsst signaling. Comprehensive analysis showed that REM SD improved the depression-like phenotype in mice by inhibiting VIP neurons.

Previous studies indicated that SST neurons in the mPFC exhibit different responses in depression (47, 48). Our results demonstrated that the Ca2+ signaling of SST neurons decreased during depression and increased after REM SD (Fig. 3). There are known local microcircuits of VIP-SST-pyramidal neurons in the mPFC. REM SD reduces the activity of VIP neurons, thereby increasing the activity of SST neurons. A study showed that VIP neurons in the PFC during REM sleep had an inhibitory effect on SST neurons (49). Therefore, in this study, the increase of calcium signaling in SST neurons after REM SD was also highly likely to be regulated by VIP neurons. Our results showed that chemogenetically activating SST neurons reduced the immobility time in the FST of mice (Fig. 4), which might be similar to a previous study that knocked down adenylyl cyclase 3 (ADCY3) in SST neurons (50). Furthermore, it had been reported that TST may be mediated through an interaction with the kynurenine pathway and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (51). SPT is highly likely to involve the activation of neurons in the nucleus accumbens that project to the ventral pallidum (52). Further investigation may be needed to improve the underlying mechanisms for the different depressive-like behaviors later.

Parvalbumin (PV) neurons inhibit pyramidal neuron somata activity through feedback and feedforward mechanisms (53). PV neurons are involved in depression. Meanwhile, the function of PV neurons appears to be altered in psychiatric diseases. Previous research pointed out that ablation of PV neurons from the ventral dentate gyrus successfully induced depression-like behavior (54). In addition, running exercise, which is faster and more effective than fluoxetine therapy, reverses depression-like behavior by increasing the number and dendritic complexity of PV neurons, rather than affecting the number of GABAergic neurons (55). According to the research of Aime et al. (49), PV neurons in prelimbic (PrL) were more active during REM sleep. However, acute sleep deprivation increased oxidative stress in PV neurons, thereby disrupting neural oscillations in the CA1 and ultimately leading to a decline in memory precision (56). In the future, the underlying mechanism by which PV neurons alleviate depression-like behaviors after REM SD requires further investigation.

Our study revealed that REM SD decreased the VPAC2 receptor on pyramidal neurons through VIP neurons, activating the AC/cAMP/PKA signaling pathway, enhancing the synaptic plasticity of pyramidal neurons, and alleviating depression. Joo et al. (57) demonstrated that VPAC2 was localized in pyramidal neurons. We used viral-mediated knockdown of the VPAC2 receptor in pyramidal neurons and found that REM SD did not alleviate depression-like behavior in mice. In addition, viral-mediated knockdown of the VPAC2 receptor in SST neurons did not prevent REM SD from alleviating depression-like behavior in mice (fig. S8). Therefore, the local microcircuit of VIP-SST-pyramidal neurons does not play a major role in alleviating depressive-like behaviors after REM SD. Our findings suggest that the VIP neurons directly influence the VPAC2 receptor in pyramidal neurons is essential for alleviating depression-like behaviors after REM SD (fig. S9).

Adenosine signaling is implicated in the control of human sleep (58, 59). In basic research, Hines et al. (60) emphasized that astrocytic signaling to adenosine receptor 1 (A1) was required for the robust reduction of depressive-like behaviors following sleep deprivation. A1 is a category of a subfamily of GPCRs (61); therefore, the adenosine A1 receptor may alleviate depression-like behaviors through the AC-cAMP-PKA signaling pathway. Although our protocol does not involve delta power enhancement after REM SD, the VPAC2 receptor equally alleviates depression-like behavior via the AC-cAMP-PKA signaling pathway (Fig. 6). A1 and VPAC2 receptors may be mediated by a similar molecular mechanism in astrocytes and pyramidal neurons, respectively.

This study primarily used a large cohort of C57BL/6J mice as experimental subjects. However, variations in REM SD effects might exist among various mouse strains, necessitating future investigations with additional strains to assess potential similarities in neural and behavioral outcomes (62, 63). Although certain experiments in this study used female mice as subjects and confirmed that the knockdown of the VPAC2 receptor of pyramidal neurons in the mPFC of female mice produced similar results to male mice, the investigation did not address whether female mice exhibited comparable outcomes to male mice regarding the REM SD effect, the gradient of REM SD, and the duration of depression alleviation induced by REM SD. Both male and female mice exhibited a limited duration of sustained behavioral effects after REM SD. Future research should aim to extend the observation period for the remission of depression-like behaviors following REM SD in depressed mice (64). In addition, it is important to determine if REM SD continues to alleviate depression-like behaviors in mice on the fifth day after the intervention. Our findings indicate that the application of REM SD with pharmacological treatments could help address the therapeutic challenges related to the high incidence of depression and treatment-resistant depression in women within clinical settings (65, 66).

The present study demonstrates that REM SD is an innovative, long-lasting antidepressant treatment (67). Analyzing the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the antidepressant effects of REM SD could facilitate the creation of more targeted and safer treatments for depression. This may guide future interventions for MDD through the regulation of REM sleep.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male and female C57BL/6J mice (2 months old, weighing 23 to 25 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology [license no. SCXK (Jing) 2021-0011, Beijing, China]. All transgenic animals were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (VIP-Cre: stock no. 010908; SST-Cre: stock no. 013044) and bred with C57BL/6J mice for several generations. Either heterozygous or homozygous Cre+ mice were used for experiments. Standard genotyping primers were available on the Jackson Laboratory website. The animals were housed in groups of 5 per cage covered with corn-cob bedding under controlled conditions: a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle [light on at 7:00 a.m. (ZT0)], a temperature of 22° ± 1°C, a humidity of 50 ± 2%, and free access to food and water for at least 1 week before experiments. Mice in the same cage were randomly divided into CUMS, CON, and REM SD groups. All animal experiments (TMUaMEC 2022004) were approved by the Animal Use Committee of Tianjin Medical University and conformed to the ethical guidelines for using experimental animals.

REM sleep deprivation

We adopted the same 12 hours of sleep deprivation duration as Wu et al. (68). We used the modified multiple-platform apparatus to induce REM SD. The water chamber (46 cm by 33 cm by 26 cm) contained 10 circular platforms (5 cm in height, 3 cm in diameter) elevated 1 cm above the water surface, allowing the mice to easily move between platforms. During the REM period, mice experienced muscle flaccidity and weakness, causing them to fall into the water and wake up. A heating apparatus consistently maintained the water temperature at 25°C throughout the experiment. Specifically, for the 6 hours of REM SD, mice underwent REM SD from ZT6 to ZT12, and after a 2-hour rest, groups were started testing at ZT14. For the 12 hours of REM SD, mice were subjected to REM SD from ZT0 to ZT12, followed by a 2-hour rest, with groups were started testing at ZT14. For the 18 hours of REM SD, mice experienced REM SD from ZT0 to ZT18, and after a 2-hour rest, groups were started testing at ZT20.

Viral injection and fiber implantation

For virus injection, mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were anesthetized with an isoflurane/oxygen mixture (adjustment of isoflurane concentration by the respiratory rate in mice) and mounted on a stereotaxic instrument. During surgery, erythromycin eye ointment was applied to prevent corneal drying, and body temperature was maintained at 37° ± 0.5°C with an electric heated pad. After the scalps of the mice were cut open and their skulls were exposed, a small hole (compliant with virus injection and fiber implantation) was drilled into the surface of the skull with a dental drill. Viruses were injected bilaterally or unilaterally using a glass micropipette with a tip filled with 150 to 200 nl of virus solution into the mPFC, primarily the PrL subregion, of VIP-Cre, SST-Cre, and C57BL/6J mice [anterior-posterior (AP), +1.85 mm; medial-lateral (ML), ± 0.20 mm; dorso-ventral (DV), −1.95 mm from the dura] using a stereotactic instrument. An optical fiber (inner diameter: 200 μm, outer diameter: 2.5 mm, numerical aperture of 0.37, Shanghai Fiblaser Technology Co. Ltd.) was implanted 0.1 mm above the virus injection area for fiber photometry tests. All fibers were implanted on the same day after the viral injection. For chemogenetic activation or inhibition, the virus was injected into the bilateral mPFC at the coordinates mentioned above. Specifically, for the integration of chemogenetic manipulation and the somatostatin neurotransmitter fluorescent probe, mice were initially administered bilateral injections of chemogenetic manipulation viruses, followed by injections of the somatostatin neurotransmitter fluorescent probe 14 days later. The mice were allowed a recovery period of 2 weeks before participating in the CUMS program. In trials targeting VPAC2 receptor knockdown in pyramidal neurons, two viruses were bilaterally injected into mPFC at specified coordinates. Mice recovered in their familiar environments for at least 14 days after surgeries.

The following viruses were used: rAAV-CaMKIIα-GCaMp6m-WPRE-hGH polyadenylate [poly(A)] (Brainvta, for the per side of mPFC of C57/BL6J mice); rAAV-EF1α-DIO-GCaMp6m-WPRE-hGH poly(A) (Brainvta, for the per side of mPFC of VIP-Cre mice and SST-Cre mice); PFD-rAAV-hSyn-iGluSnFR(A184S)-WPRE-hGH poly(A) (Brainvta, for the one side of mPFC of VIP-Cre mice and SST-Cre mice); rAAV-hSyn-SST1.0 (Brain Case, for the one side of mPFC of VIP-Cre mice); rAAV-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry-WPRE-hGH poly(A), rAAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry-WPRE-hGH poly(A) and rAAV-Ef1α-DIO-mCherry-WPRE-hGH poly(A) (Brainvta, per side of mPFC of VIP-Cre mice and SST-Cre mice); rAAV-CaMKIIα-CRE-WPRE-hGH poly(A) (Brainvta, per side of mPFC of C57/BL6J mice); rAAV-CMV-DIO-(mCherry-U6)-shRNA(VIPR2)-WPRE-hGH poly(A) (Brainvta, per side of mPFC of C57/BL6J mice and SST-Cre mice); and rAAV-CMV-DIO-(mCherry-U6)-shRNA(scramble)-WPRE-hGH poly(A) (Brainvta, per side of mPFC of C57/BL6J mice and SST-Cre mice).

Chemogenetic modulation of the activity of specific neurons.

For chemogenetic manipulation of VIP or SST neurons in the mPFC, we injected hM4Di or hM3Dq viruses bilaterally into the mPFC. These DREADDs were selectively activated or inhibited by CNO. Mice received intraperitoneal injections of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg) at different time points and rested for 2 hours before behavioral tests.

For chemogenetic activation of VIP neurons in the mPFC, AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice. Subsequently, these mice underwent the CUMS procedure followed by REM SD (ZT0 to ZT12). At ZT12, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg) or vehicle, and behavioral tests were conducted 2 hours later.

For chemogenetic inhibition of VIP neurons in the mPFC, AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice, and subsequently, these mice underwent the CUMS procedure. At ZT12, depressive mice received an intraperitoneal injection of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg) or vehicle, and behavioral tests were conducted 2 hours later.

For chemogenetic activation of SST neurons in the mPFC, AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the mPFC of SST-Cre mice, and subsequently, these mice underwent the CUMS procedure. At ZT12, depressive mice received an i.p. injection of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg) or vehicle, and behavioral tests were conducted 2 hours later.

For chemogenetic inhibition of SST neurons in the mPFC, AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the mPFC of SST-Cre mice. Subsequently, these mice underwent the CUMS procedure followed by REM SD (ZT0 to ZT12). At ZT12, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg) or vehicle, and behavioral tests were conducted 2 hours later.

Golgi staining, imaging, and quantification

The brains of euthanized mice were impregnated using the FD Rapid Golgi Stain Kit (FD Neuro Technologies, Columbia, MD, USA, catalog no. PK401) to visualize the morphological details of dendritic spines and dendritic complexity. Mice were euthanized after REM SD or CUMS or control conditions. Their brains were immersed in Golgi solution (A:B = 1:1) for 24 hours. The solution was replaced with a fresh solution the next day and maintained for 13 days. Subsequently, the brains were transferred to the Golgi solution C for 72 hours. All three solutions containing the brain were stored in the dark at room temperature. Brains were then sectioned into 100-μm coronal sections in the fresh Golgi solution C using a vibratome (VT1200 S, Leica). Brain sections were affixed onto Gelatin-covered slides and dried overnight. Samples were washed twice with Milli-Q water and immersed in Solution (D:E:Milli-Q water = 1:1:2) for 10 min, followed by 4-min washes in 50, 75, 95, and 100% alcohol and xylol. Images of secondary dendritic spines in the apical dendrites of selected pyramidal neurons were visualized by bright-field microscopy (BX51, Olympus) at ×100 (oil) and ×20 magnifications. Three-dimensional reconstruction of dendritic spines and dendritic branches was performed using NeuronStudio software (Bioimage Informatics Index, New York, USA) (69, 70). We use the highest optical resolution to ensure that dendritic spines are clear. We selected secondary dendrites of neurons that had a clean background, clear visibility, sharp edges, and consistent staining and were relatively isolated for imaging, followed by quantitative analysis using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Exclude dendrites with discontinuous staining or ill-defined imaging. Also excludes swollen, bead-like dendrites. Based on the previously described criteria, with minor modifications, the dendritic spines were categorized into three subtypes: thin dendritic spines, mushroom dendritic spines, and short stubby dendritic spines (71). Thin dendritic spines had head-to-neck diameter ratios less than 1.1 and lengthy spines with head diameters greater than 2.0. Mushroom-type dendritic spines had head diameters greater than 0.5 μm and head-to-neck ratios greater than 1.1. Stubby-type dendritic spines lacked a clear distinction between the head and the connection with the shaft. For Sholl analysis, continuous focus adjustment was used to capture as much detail as possible of the entire structure of a single neuron. Individual neuron structures were visualized using NeuronStudio software. Scholl analysis, total dendrite length, number of branch points, and spine density were subsequently performed using ImageJ software and the Simple Neurite Tracer plugins (72). Spine density was quantified as the number of dendritic branching protrusions per micrometer of dendritic length.

Western blot analysis

Following all behavioral experiments, the total protein of the mPFC was isolated from the animals’ brains. The tissue was lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Beyotime Technology, Shanghai, China) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Technology, Shanghai, China) on ice and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Lysates were added to the loading buffer (Cowin Biotech, Jiangsu, China) and denatured by boiling at 65°C for 5 min. Target proteins were separated by 8, 4 to 12, or 4 to 20% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (ACE biotechnology, Jiangsu, China) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membrane was blocked for 2 hours in TBST [150 mM NaCl, 10 mM tris, and 0.1% Tween 20 (pH 7.6)] containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated with primary antibodies against phosphor-GluR1 (1:1000; ABclonal, AP1289), GluA1 (1:1500; #13185, Cell Signalling Technology), phosphor-GluR2 (1:1000; absin, abs147627), GluA2 (1:5000; ab133477, Abcam), VPAC1(1:100; PA5-142782, Thermo Fisher Scientific), VPAC2 (1:200; SC-52795, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PKA alpha/beta/gamma CAT Antibody (1:1000; #AF7746, Affinity), adenylate cyclase 2 antibody (1:1000; PA5-114701, Thermo Fisher Scientific), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:1000; AF0006, Beyotime Technology), GAPDH (1:5000; 60004-1-Ig, Proteintech), β-actin (1:5000; 60008-1-IG, Proteintech), and α-tubulin (1:1000;14555-1-AP, Proteintech) at 4°C overnight. The membrane was washed three times with TBST and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary anti-rabbit (1:10,000; ab6721, Abcam), anti-mouse antibodies (1:10,000; ab6728, Abcam), and anti-goat (1:1000; A0181, Beyotime Technology). Protein bands were visualized using an ECL Western blot Detection kit (P0018FS, Beyotime), and the images were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Electrophysiological experiment

Acute brain slice preparation

The animals were euthanized immediately after finishing REM SD, and their brains were swiftly removed and deposited in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) comprising 2 mM CaCl2.2H2O, 2.5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 120.0 mM NaCl, 10 mM C6H12O6·H2O, and 26 mM NaHCO3 for 1 to 2 min. The brains were sectioned into coronal slices (300 μm) encompassing the mPFC, immersed in ice-cold ACSF, and placed in a holding chamber within an incubator. Slices were let to recuperate at 33°C for 30 min, subsequently transferred to room temperature for 1 hour, and then fixed in a recording chamber perfused with heated ACSF (25° to 28°C) for recording. All ACSF used in the experiment was continuously perfused with 95% O2 and 5% CO2.

Field potential recording

Extracellular field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were conducted as previously outlined (73). Double patch-clamp EPC10 plus (HEKA, USA) was used to record fEPSPs. The brain slice chamber system (Harvard Apparatus, USA) preserved brain slice preparations and facilitated stable recordings. Brain slices were maintained in the Brain slice chamber system at 28°C for 2 hours before experimentation. Glass recording electrodes filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid were placed in the mPFC. Bipolar mental stimulation electrodes were placed in approximately layer V of the mPFC, and recordings were obtained from layer II/III (filled with ACSF, 5 to 7 megohm resistance). Stable baseline recordings were acquired for 40 min before LTP stimulation to guarantee a steady recording before stimulation. Stimuli intensity was adjusted to 30% of the maximal response. All recordings persisted for 120 min. Subsequently, mPFC LTP was induced through electrical stimulation known as theta-burst stimulation (TBS), consisting of a sequence of 10 bursts, each containing four stimuli at a frequency of 100 Hz (200-ms interval) (73, 74).

Immunofluorescence staining

Mice were perfused with 40 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 20 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Isolated brains were collected and postfixed in 4% PFA at 4°C for 18 to 24 hours and then dehydrated sequentially in a gradient of 20 and 30% sucrose in PBS and stored at 4°C until bottoming out. The brains were coronally sectioned into 40-μm sections using a frozen microtome (Leica CM 1950). Fluorescent brain sections were selected for the next step in the experiments. Sections were washed with PBS three times (10 min each), blocked in blocking solution (5% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C: anti–c-Fos (1:1200; 226003, Synaptic system). The following day, the sections were washed with PBS three times (10 min each) and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with the corresponding Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000; 1942295, Invitrogen). The sections were washed with PBS three times (10 min each) and incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:800; D1306, Thermo Fisher Scientific) staining solution for 15 min. Last, all the sections were washed three times (5 min each). All of the above processes were carried out under light-proof conditions. Stained immunofluorescence images were acquired with laser confocal microscopy (LSM 800 and LSM 900, ZEISS, Jena, Germany), and quantitative analysis was performed with ImageJ.

Fiber photometry recording and data analysis

GCaMP6m, GCaMP6f, GRABglu, and GRABsst fluorescence signals were collected at a frequency of 50 Hz through the optic fiber with a fiber photometry system (Thinker Tech, Nanjing). The fluorescence signal was acquired under the stimulation of a 470-nm light-emitting diode (20 to 30 μW at the fiber tip). During recording, a video camera (Logitech, Switzerland) was placed directly to track the mice’s behavior. A screen recorder (EV Capture, Hunan Yiwei) was used to simultaneously capture the mouse behaviors and fluorescence signals. Data were recorded with customized LabVIEW software (National Instruments). For Ca2+, GRABglu, and GRABsst, the duration of the suspension was estimated to be 6 min. The final 4 min of data, where mice struggled, were selected for analysis. For GRABglu and GRABsst, signals were recorded for 30 min in the freely moving mice during wall-climbing exploration in an open field; the final 28 min of data was chosen as the available data. Only one behavioral test (OFT or TST) was performed per mouse.

To calculate the ∆F/F ratio of fluorescence signals, raw data were exported by processing software and analyzed with custom-made MATLAB codes. The data were segmented on the basis of behavioral events within individual trials. We derived the values of fluorescence change (∆F/F) by calculating (F − F0)/F0, where F0 is the baseline fluorescence signal averaged over a 2-s long control time window preceding the trigger events. ∆F/F values are presented as heatmaps or average plots, with the shaded area indicating the SEM. After collecting all behaviors and calcium signals, mice were sedated with isoflurane, perfused, and postfixed with ice-cold PBS and 4% PFA. We analyzed the tissue to confirm successful AAV expression at the intended site and also performed immunofluorescence staining.

GRAB fluorescence signal of glutamate and somatostatin

The AAV carrying the gene for green fluorescent GRAB glutamate and somatostatin sensors (PFD-rAAV-hSyn-iGluSnFR (A184S)-WPRE-hGH poly(A) and rAAV-hSyn-SST1.0) was injected into the mPFC (AP, +1.85 mm; ML, ±0.20 mm; DV, −1.95 mm from the dura). This high-performance GRAB sensor provides a powerful tool for studying neuropeptide release and the unique release kinetics and molecular regulation of small-molecule neurotransmitters (75). GRABglu mainly detected glutamate neurotransmitters released by pyramidal neurons in the target brain region, and GRABsst mainly detected somatostatin neurotransmitters released by SST neurons in the target brain region. The GRAB fluorescence signal was recorded in the same way as calcium imaging, and the fluorescence signal was collected from the GRABglu and GRABsst for data analysis.

For chemogenetic activation of VIP neurons in the mPFC, AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry was bilaterally injected while simultaneously recording changes in glutamate neurotransmitter levels. In addition, PFD-rAAV-hSyn-iGluSnFR (A184S)-WPRE-hGH poly(A) was unilaterally injected into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice. Subsequently, mice after surgery proceed to the CUMS procedure after a 14-day rest followed by REM SD (ZT0 to ZT12). At ZT12, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg), and fiber recordings were conducted 2 hours later. Only one test (OFT or TST) was performed per mouse.

For chemogenetic inhibition of VIP neurons in mPFC, while recording changes in glutamate neurotransmitters were recorded simultaneously, AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry was bilaterally injected, and PFD-rAAV-hSyn-iGluSnFR (A184S)-WPRE-hGH poly(A) was unilaterally injected into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice. Subsequently, mice after surgery proceed to the CUMS procedure after a 14-day rest. At ZT12, depressive mice received an intraperitoneal injection of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg), and fiber recordings were conducted 2 hours later. Only one test (OFT or TST) was performed per mouse.

For chemogenetic activation of VIP neurons in mPFC, while recording changes in somatostatin neurotransmitters were recorded simultaneously, AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice. After 14 days of chemogenetic virus injection, rAAV-hSyn-SST1.0 was injected unilaterally into the mPFC. Subsequently, mice after surgery proceed to the CUMS procedure after a 14-day rest followed by REM SD (ZT0 to ZT12). At ZT12, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg), and fiber recordings were conducted 2 hours later. Only one test (OFT or TST) was performed per mouse.

For chemogenetic inhibition of VIP neurons in mPFC, while recording changes in somatostatin neurotransmitters were recorded simultaneously, AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry was bilaterally injected into the mPFC of VIP-Cre mice. After 14 days of chemogenetic virus injection, rAAV-hSyn-SST1.0 was injected unilaterally into the mPFC. Subsequently, mice after surgery proceed to the CUMS procedure after a 14-day rest. At ZT12, depressive mice received an intraperitoneal injection of CNO (dissolved in the vehicle, 5 mg/kg), and fiber recordings were conducted 2 hours later. Only one test (OFT or TST) was performed per mouse.

Behavioral assays

Chronic unpredictable mild stress

All mice subjected to CUMS were housed individually. They were exposed to two random mild stressors each day for 6 weeks, including restraint (4 hours), food or water deprivation (24 hours), forced swimming in ice water (5 min), moist sawdust (12 hours), inversion light/dark cycle (24 hours), and white noise (85 dB, 1 hour).

Sucrose preference test

Mice were housed individually and acclimated to two bottles of liquid—one with pure water and one with 1% (w/v) sucrose solution for 24 hours. The bottles were of identical size and appearance. Then, two bottles (one 1% sucrose and one pure water) and food were provided. Bottle positions were switched after 12 hours. Water and sucrose consumption were measured by weighing the bottles after 24 hours.

Open field test

An open-field test evaluated depression-like behavior in a white experiment chamber (44 cm by 44 cm). The behavioral software autodefined the center square. The activity of mice was recorded for 6 min. The first 2 min was defined as adapting the equipment, with the activity in the last 4 min monitored. Total and center distance were recorded as indices of exploratory activity and depression, respectively.

Forced swimming test

Mice were briefly placed in a glassed cylinder (height: 24.8 cm, diameter: 16 cm) containing water (24° ± 1°C) and forced to swim for 6 min. The mice were acclimated for the first 2 min, and the immobility time was monitored over the next 4 min. Immobility time was defined as when the mice kept floating or remained motionless, with only movements necessary to maintain water balance.

Tail suspension test

Mice were suspended 40 cm above the floor and attached approximately 2 to 3 mm from the tip of their tails, secured with sticky tape for 6 min. The mice were accustomed for the first 2 min, and the immobility was monitored over the next 4 min. The immobility period referred to slight forelimb movements without hindlimb involvement. Swinging caused by inertia was also considered immobility.

Elevated plus maze test

An intersected apparatus was raised 36 cm above the floor. Mice were carefully positioned in the center of the maze, with their heads facing an open arm. A video camera positioned above the apparatus was used to track each mouse. The number of entries into open arms and the time spent there were analyzed throughout the 6-min experiment. The initial 2 min was allocated for equipment adaptation, while the subsequent 4 min was subject to monitoring.

Analysis and statistics

For all experiments, we adopted randomized grouping and double-blind testing. All significant statistical results are indicated in the figures following the conventions: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.0001. The results were presented as means ± SEM, and statistical analysis was performed using Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). All data were assessed for normality. For two-group comparisons, statistical significance was determined by unpaired t tests. For multiple group comparisons, one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used for the data, followed by Tukey’s post hoc analyses or Bonferroni’s post hoc test. In particular, for Golgi staining, in the analysis of dendritic spines and dendritic branch intersections, we used one-way ANOVA (three or more groups) or unpaired t tests (two groups); however, in the analysis of dendritic complexity, we used two-way ANOVA.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Tianjin Medical University Animal Department for its assistance with animal care and the Tianjin Medical University Basic Medical Research Center for contributing to scientific instruments.

Funding: This work was supported by the Joint Funds for the STI2030 major project no. 2021ZD0202900 (to H.S.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China nos. 62027812, 62273186, and 82101608.

Author contributions: Investigation and formal analysis: Y.Z., T.W., and Q.J. Conceptualization: Y.Z., T.W., Q.J., and H.S. Methodology and software: Y.W., Q.X., K.L., A.L., and C.T. Data curation: Z.L., H.C., P.W., and H.H. Validation: Y.Z., T.W., Q.J., and B.C. Writing—original draft: Y.Z. and T.W. Writing—reviewing and editing: Y.Z., T.W., Q.J., and H.S. Resources: H.S. and A.L. Visualization: Y.Z., T.W., and H.S. Supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition: H.S.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S9

Legend for data S1

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Data S1

REFERENCE AND NOTES

- 1.Karageorgiou V., Casanova F., O’Loughlin J., Green H., McKinley T. J., Bowden J., Tyrrell J., Body mass index and inflammation in depression and treatment-resistant depression: A Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med. 21, 355 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdin E., Chong S. A., Vaingankar J. A., Shafie S., Verma S., Luo N., Tan K. B., James L., Heng D., Subramaniam M., Impact of mental disorders and chronic physical conditions on quality-adjusted life years in Singapore. Sci. Rep. 10, 2695 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X., Zhang H., Wu K., Fan B., Guo L., Liao Y., McIntyre R. S., Wang W., Liu Y., Shi J., Chen Y., Shen M., Wang H., Li L., Han X., Lu C., Impact of painful physical symptoms on first-episode major depressive disorder in adults with subthreshold depressive symptoms: A prospective cohort study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 86, 1–9 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duman R. S., Aghajanian G. K., Sanacora G., Krystal J. H., Synaptic plasticity and depression: New insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat. Med. 22, 238–249 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Loh B. M., Yaw A. M., Breuer J. A., Jackson B., Nguyen D., Jang K., Ramos F., Ho E. V., Cui L. J., Gillette D. L. M., Sempere L. F., Gorman M. R., Tonsfeldt K. J., Mellon P. L., Hoffmann H. M., The transcription factor VAX1 in VIP neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus impacts circadian rhythm generation, depressive-like behavior, and the reproductive axis in a sex-specific manner in mice. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1269672 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shukla R., Newton D. F., Sumitomo A., Zare H., McCullumsmith R., Lewis D. A., Tomoda T., Sibille E., Molecular characterization of depression trait and state. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 1083–1094 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arbabi K., Newton D. F., Oh H., Davie M. C., Lewis D. A., Wainberg M., Tripathy S. J., Sibille E., Transcriptomic pathology of neocortical microcircuit cell types across psychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 30, 1057–1068 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.F. Weber, J. Hong, D. Lozano, K. Beier, S. Chung, Prefrontal cortical regulation of REM sleep. Res. Sq., doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1417511/v1 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Zhou Y., Lai C. S. W., Bai Y., Li W., Zhao R., Yang G., Frank M. G., Gan W. B., REM sleep promotes experience-dependent dendritic spine elimination in the mouse cortex. Nat. Commun. 11, 4819 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng X., Wu X., Zhang Y., Li W., Feng L., You H., Yang S., Yang D., Chen X., Pan X., LRRK2 deficiency aggravates sleep deprivation-induced cognitive loss by perturbing synaptic pruning in mice. Brain Sci. 12, 1200 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiao Q., Dong X., Guo C., Wu T., Chen F., Zhang K., Ma Z., Sun Y., Cao H., Tian C., Hu Q., Liu N., Wang Y., Ji L., Yang S., Zhang X., Li J., Shen H., Effects of sleep deprivation of various durations on novelty-related object recognition memory and object location memory in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 418, 113621 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamaki M., Wang Z., Barnes-Diana T., Guo D., Berard A. V., Walsh E., Watanabe T., Sasaki Y., Complementary contributions of non-REM and REM sleep to visual learning. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 1150–1156 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perogamvros L., Baird B., Seibold M., Riedner B., Boly M., Tononi G., The phenomenal contents and neural correlates of spontaneous thoughts across wakefulness, NREM sleep, and REM sleep. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 1766–1777 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vyazovskiy V. V., Delogu A., NREM and REM sleep: Complementary roles in recovery after wakefulness. Neuroscientist 20, 203–219 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miao A., Luo T., Hsieh B., Edge C. J., Gridley M., Wong R. T. C., Constandinou T. G., Wisden W., Franks N. P., Brain clearance is reduced during sleep and anesthesia. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1046–1050 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemmeter U.-M., Hemmeter-Spernal J., Krieg J.-C., Sleep deprivation in depression. Expert Rev. Neurother. 10, 1101–1115 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahan A., Mahe K., Dutta S., Kassraian P., Wang A., Gradinaru V., Immediate responses to ambient light in vivo reveal distinct subpopulations of suprachiasmatic VIP neurons. iScience 26, 107865 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng Y., Tsuno Y., Matsui A., Hiraoka Y., Tanaka K., Horike S. I., Daikoku T., Mieda M., Cell type-specific genetic manipulation and impaired circadian rhythms in Vip tTA knock-in mice. Front. Physiol. 13, 895633 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi S., Kawanai T., Yamauchi R., Chen L., Miyaoka T., Yamada M., Asano S., Hayata-Takano A., Nakazawa T., Yano K., Horiguchi N., Nakagawa S., Takuma K., Waschek J. A., Hashimoto H., Ago Y., Activation of the VPAC2 receptor impairs axon outgrowth and decreases dendritic arborization in mouse cortical neurons by a PKA-dependent mechanism. Front. Neurosci. 14, 521 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Couvineau A., Laburthe M., VPAC receptors: Structure, molecular pharmacology and interaction with accessory proteins. Br. J. Pharmacol. 166, 42–50 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonas P., Bischofberger J., Fricker D., Miles R., Interneuron Diversity series: Fast in, fast out—Temporal and spatial signal processing in hippocampal interneurons. Trends Neurosci. 27, 30–40 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunha-Reis D., Ribeiro J. A., Sebastião A. M., VIP enhances synaptic transmission to hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells through activation of both VPAC1 and VPAC2 receptors. Brain Res. 1049, 52–60 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunha-Reis D., Ribeiro J. A., SebastiÃO A. M., VPAC2 receptor activation mediates VIP enhancement of population spikes in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1070, 210–214 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang M. J., Song M. L., Zhang Y., Yang X. M., Lin H. S., Chen W. C., Zhong X. D., He C. Y., Li T., Liu Y., Chen W. G., Sun H. T., Ao H. Q., He S. Q., SNS alleviates depression-like behaviors in CUMS mice by regluating dendritic spines via NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 312, 116360 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu R., Zhou H., Qu H., Chen Y., Bai Q., Guo F., Wang L., Jiang X., Mao H., Effects of aerobic exercise on depression-like behavior and TLR4/NLRP3 pathway in hippocampus CA1 region of CUMS-depressed mice. J. Affect. Disord. 341, 248–255 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan Z., Qi Z., Wang R., Cui Y., An S., Wu G., Feng Q., Lin R., Dai R., Li A., Gong H., Luo Q., Fu L., Luo M., A corticoamygdalar pathway controls reward devaluation and depression using dynamic inhibition code. Neuron 111, 3837–3853.e5 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bijata M., Bączyńska E., Müller F. E., Bijata K., Masternak J., Krzystyniak A., Szewczyk B., Siwiec M., Antoniuk S., Roszkowska M., Figiel I., Magnowska M., Olszyński K. H., Wardak A. D., Hogendorf A., Ruszczycki B., Gorinski N., Labus J., Stępień T., Tarka S., Bojarski A. J., Tokarski K., Filipkowski R. K., Ponimaskin E., Wlodarczyk J., Activation of the 5-HT7 receptor and MMP-9 signaling module in the hippocampal CA1 region is necessary for the development of depressive-like behavior. Cell Rep. 38, 110532 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inaba H., Li H., Kawatake-Kuno A., Dewa K. I., Nagai J., Oishi N., Murai T., Uchida S., GPCR-mediated calcium and cAMP signaling determines psychosocial stress susceptibility and resiliency. Sci. Adv. 9, eade5397 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briand L. A., Deutschmann A. U., Ellis A. S., Fosnocht A. Q., Disrupting GluA2 phosphorylation potentiates reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Neuropharmacology 111, 231–241 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bekhbat M., Neigh G. N., Sex differences in the neuro-immune consequences of stress: Focus on depression and anxiety. Brain Behav. Immun. 67, 1–12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X., Zhang Y., Wang J., Qin L., Li Y., He Q., Zhang T., Wang Y., Song L., Ji L., Long B., Wang Q., Role of SIRT1-mediated synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis: Sex-differences in antidepressant-like efficacy of catalpol. Phytomedicine 135, 156120 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C., Zhu H., Ni Z., Xin Q., Zhou T., Wu R., Gao G., Gao Z., Ma H., Li H., He M., Zhang J., Cheng H., Hu H., Dynamics of a disinhibitory prefrontal microcircuit in controlling social competition. Neuron 110, 516–531 e516 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang S., Gumpper R. H., Huang X. P., Liu Y., Krumm B. E., Cao C., Fay J. F., Roth B. L., Molecular basis for selective activation of DREADD-based chemogenetics. Nature 612, 354–362 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunha-Reis D., Ribeiro J. A., de Almeida R. F. M., Sebastiao A. M., VPAC1 and VPAC2 receptor activation on GABA release from hippocampal nerve terminals involve several different signalling pathways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 4725–4737 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKenzie C. J., Lutz E. M., Johnson M. S., Robertson D. N., Holland P. J., Mitchell R., Mechanisms of phospholipase C activation by the vasoactive intestinal polypeptide/pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide type 2 receptor. Endocrinology 142, 1209–1217 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hara M., Takeba Y., Iiri T., Ohta Y., Ootaki M., Watanabe M., Watanabe D., Koizumi S., Otsubo T., Matsumoto N., Vasoactive intestinal peptide increases apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting the cAMP/Bcl-xL pathway. Cancer Sci. 110, 235–244 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A R.-H., Gong Q., Tuo Y.-J., Zhai S.-T., He B.-L., Zou E.-G., Wang M.-L., Huang T.-Y., Zha C.-L., He M.-Z., Zhong G.-Y., Feng Y.-L., Li J., Syringa oblata Lindl extract alleviated corticosterone-induced depression via the cAMP/PKA-CREB-BDNF pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 341, 119274 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S. C., Chen Y. H., Song Y., Zong S. H., Wu M. X., Wang W., Wang H., Zhang F., Zhou Y. M., Yu H. Y., Zhang H. T., Zhang F. F., Upregulation of phosphodiesterase 7A contributes to concurrent pain and depression via inhibition of cAMP-PKA-CREB-BDNF signaling and neuroinflammation in the hippocampus of mice. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 27, pyae040 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Itoh N., Enomoto A., Nagai T., Takahashi M., Yamada K., Molecular mechanism linking BDNF/TrkB signaling with the NMDA receptor in memory: the role of Girdin in the CNS. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 481–490 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caviedes A., Lafourcade C., Soto C., Wyneken U., BDNF/NF-κB signaling in the neurobiology of depression. Curr. Pharm. Des. 23, 3154–3163 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marini A. M., Jiang X., Wu X., Tian F., Zhu D., Okagaki P., Lipsky R. H., Role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and NF-kappaB in neuronal plasticity and survival: From genes to phenotype. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 22, 121–130 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lipsky R. H., Xu K., Zhu D., Kelly C., Terhakopian A., Novelli A., Marini A. M., Nuclear factor kappaB is a critical determinant in N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated neuroprotection. J. Neurochem. 78, 254–264 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hiester B. G., Galati D. F., Salinas P. C., Jones K. R., Neurotrophin and Wnt signaling cooperatively regulate dendritic spine formation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 56, 115–127 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang F., Liu C. L., Tong M. M., Zhao Z., Chen S. Q., Both Wnt/beta-catenin and ERK5 signaling pathways are involved in BDNF-induced differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into neural stem cells. Neurosci. Lett. 708, 134345 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brécier A., Borel M., Urbain N., Gentet L. J., Vigilance and behavioral state-dependent modulation of cortical neuronal activity throughout the sleep/wake cycle. J. Neurosci. 42, 4852–4866 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nutt D., Wilson S., Paterson L., Sleep disorders as core symptoms of depression. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 10, 329–336 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerhard D. M., Pothula S., Liu R.-J., Wu M., Li X.-Y., Girgenti M. J., Taylor S. R., Duman C. H., Delpire E., Picciotto M., Wohleb E. S., Duman R. S., GABA interneurons are the cellular trigger for ketamine’s rapid antidepressant actions. J. Clin. Investig. 130, 1336–1349 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xue X., Pan J., Zhang H., Lu Y., Mao Q., Ma K., Baihe Dihuang (Lilium Henryi Baker and Rehmannia Glutinosa) decoction attenuates somatostatin interneurons deficits in prefrontal cortex of depression via miRNA-144-3p mediated GABA synthesis and release. J. Ethnopharmacol. 292, 115218 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aime M., Calcini N., Borsa M., Campelo T., Rusterholz T., Sattin A., Fellin T., Adamantidis A., Paradoxical somatodendritic decoupling supports cortical plasticity during REM sleep. Science 376, 724–730 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang X. Y., Ma Z. L., Storm D. R., Cao H., Zhang Y. Q., Selective ablation of type 3 adenylyl cyclase in somatostatin-positive interneurons produces anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in mice. World J. Psychiatry 11, 35–49 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Arruda C. M., Doneda D. L., de Oliveira V. V., da Silva R. A. L., de Matos Y. A. V., Fernandes I. L., Rohden C. A. H., Viola G. G., Rios-Santos F., de Lima E., da Silva Buss Z., Vandresen-Filho S., Involvement of kynurenine pathway and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in the antidepressant-like effect of vilazodone in the tail suspension test in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 218, 173433 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He L. W., Zeng L., Tian N., Li Y., He T., Tan D. M., Zhang Q., Tan Y., Optimization of food deprivation and sucrose preference test in SD rat model undergoing chronic unpredictable mild stress. Animal Model Exp. Med. 3, 69–78 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu H., Gan J., Jonas P., Interneurons., Fast-spiking, parvalbumin+ GABAergic interneurons: From cellular design to microcircuit function. Science 345, 1255263 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen S., Chen F., Amin N., Ren Q., Ye S., Hu Z., Tan X., Jiang M., Fang M., Defects of parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the ventral dentate gyrus region are implicated depression-like behavior in mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 99, 27–42 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qin L., Liang X., Qi Y., Luo Y., Xiao Q., Huang D., Zhou C., Jiang L., Zhou M., Zhou Y., Tang J., Tang Y., MPFC PV+ interneurons are involved in the antidepressant effects of running exercise but not fluoxetine therapy. Neuropharmacology 238, 109669 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao Y. Z., Liu K., Wu X. M., Shi C. N., He Q. L., Wu H. P., Yang J. J., Yao H., Ji M. H., Oxidative stress-mediated loss of hippocampal parvalbumin interneurons contributes to memory precision decline after acute sleep deprivation. Mol. Neurobiol. 62, 5377–5394 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joo K. M., Chung Y. H., Kim M. K., Nam R. H., Lee B. L., Lee K. H., Cha C. I., Distribution of vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide receptors (VPAC1, VPAC2, and PAC1 receptor) in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 476, 388–413 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mazzotti D. R., Guindalini C., Pellegrino R., Barrueco K. F., Santos-Silva R., Bittencourt L. R., Tufik S., Effects of the adenosine deaminase polymorphism and caffeine intake on sleep parameters in a large population sample. Sleep 34, 399–402 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bachmann V., Klaus F., Bodenmann S., Schafer N., Brugger P., Huber S., Berger W., Landolt H. P., Functional ADA polymorphism increases sleep depth and reduces vigilant attention in humans. Cereb. Cortex 22, 962–970 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hines D. J., Schmitt L. I., Hines R. M., Moss S. J., Haydon P. G., Antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation require astrocyte-dependent adenosine mediated signaling. Transl. Psychiatry 3, e212 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jespers W., Schiedel A. C., Heitman L. H., Cooke R. M., Kleene L., van Westen G. J. P., Gloriam D. E., Muller C. E., Sotelo E., Gutierrez-de-Teran H., Structural mapping of adenosine receptor mutations: Ligand binding and signaling mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 39, 75–89 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Halladay L. R., Kocharian A., Holmes A., Mouse strain differences in punished ethanol self-administration. Alcohol 58, 83–92 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mekada K., Yoshiki A., Substrains matter in phenotyping of C57BL/6 mice. Exp. Anim. 70, 145–160 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma S., Chen M., Jiang Y., Xiang X., Wang S., Wu Z., Li S., Cui Y., Wang J., Zhu Y., Zhang Y., Ma H., Duan S., Li H., Yang Y., Lingle C. J., Hu H., Sustained antidepressant effect of ketamine through NMDAR trapping in the LHb. Nature 622, 802–809 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mathers C. D., Loncar D., Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 3, e442 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kverno K. S., Mangano E., Treatment-resistant depression: Approaches to treatment. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 59, 7–11 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mendlewicz J., Sleep disturbances: Core symptoms of major depressive disorder rather than associated or comorbid disorders. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 10, 269–275 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]