Abstract

The 26S proteasome plays a central role in the degradation of regulatory proteins involved in a variety of developmental processes. It consists of two multisubunit protein complexes: the proteolytic core protease and the regulatory particle (RP). The function of most RP subunits is poorly understood. Here, we describe mutants in the Arabidopsis thaliana RPN1 subunit, which is encoded by two paralogous genes, RPN1a and RPN1b. Disruption of RPN1a caused embryo lethality, while RPN1b mutants showed no obvious abnormal phenotype. Embryos homozygous for rpn1a arrested at the globular stage with defects in the formation of the embryonic root, the protoderm, and procambium. Cyclin B1 protein was not degraded in these embryos, consistent with cell division defects. Double mutant plants (rpn1a/RPN1a rpn1b/rpn1b) produced embryos with a phenotype indistinguishable from that of the rpn1a single mutant. Thus, despite their largely overlapping expression patterns in flowers and developing seeds, the two isoforms do not share redundant functions during gametogenesis and embryogenesis. However, complementation of the rpn1a mutation with the coding region of RPN1b expressed under the control of the RPN1a promoter indicates that the two RPN1 isoforms are functionally equivalent. Overall, our data indicate that RPN1 activity is essential during embryogenesis, where it might participate in the destruction of a specific set of protein substrates.

INTRODUCTION

The 26S proteasome is an ATP-dependent self-compartmentalized protease of ∼2.4-MD, which degrades proteins that have been marked for destruction by ubiquitin (Voges et al., 1999). The ubiquitin/proteasome pathway plays a central role in the degradation of short-lived and regulatory proteins important in a variety of basic cellular processes, including development and differentiation (Wilkinson et al., 1999; Ciechanover et al., 2000; Weissman, 2001). Most of the proteins of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway are phylogenetically highly conserved.

The 26S proteasome is found in the nucleus and cytoplasm of both plants and animals. It is made up of two multisubunit complexes, the 20S core protease (CP) and the 19S regulatory particle (RP). Access to the cavity of CP, where proteolysis takes place, is restricted by a channel that controls entry of unfolded proteins only (Glickman, 2000). The RP is believed to trigger the identification of appropriate substrates for breakdown, to remove the attached ubiquitin moieties, to open the α-subunit gate, and to direct the entry of unfolded proteins into the CP cavity for degradation. The RP consists of 17 subunits, which form two subparticles, the lid and the base. The base contains three non-ATPase subunits (RPN1, RPN2, and RPN10) and six ATPase subunits (RPT1 to RPT6), which contact the α-subunit ring and likely assist in substrate unfolding and transport (Voges et al., 1999; Glickman, 2000; Fu et al., 2001). The lid binds to the base and contains the other nine subunits (RPN3, RPN5 to RPN9, and RPN11 to RPN13).

Currently, the functions of only a few RPN subunits are known (Smalle and Vierstra, 2004). RPN10 is able to bind polyubiquitin chains. However, since it is not essential in yeast (van Nocker et al., 1996), this subunit is probably not the main ubiquitin recognition component of the RP. RPN11 and RPN13 (or UCH37) are proteases thought to release polyubiquitin chains from the substrates (Verma et al., 2002; Vierstra, 2003). In human, the RPN1 subunit was shown to interact with the ubiquitin protein ligase (E3) KIAA10 (You and Pickart, 2001). It was suggested that RPN1, as well as RPN2, form the receptors for the ubiquitin-like proteins Rad23 and Dsk2 in the base subcomplex (Saeki et al., 2002). Moreover, the leucine-rich-repeat-like domain of RPN1 may participate in the recognition of the cargo proteins carried by Rad23 to be presented to the proteasomal ATPases for unfolding (Elsasser et al., 2002). Deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6 also recognizes the proteasome base via the RPN1 subunit. Deubiquitination by Ubp6 prevents ubiquitin from RPN1-mediated translocation to the 20S CP, resulting in the high turnover rate of ubiquitin observed in Ubp6 mutants (Legget et al., 2002).

The analysis of mutant phenotypes showed that the RPN12a subunit of Arabidopsis thaliana participates in cytokinin responses (Smalle et al., 2002). Recently, the Arabidopsis RPT2a subunit was shown to be essential for the maintenance of cellular organization of the root and shoot apical meristem (Ueda et al., 2004). Disruption of the RPN10 gene in the moss Physcomitrella patens leads to developmental arrest (the mutants being unable to form buds and gametophores; Girod et al., 1999). Moreover, Arabidopsis plants mutated in RPN10 showed a reduction in germination and growth rate, stamen number, transmission through pollen, and hormone-responsive cell division. This is likely due to the downregulation of the cell cycle regulator CDKA;1 observed in rpn10 mutants (Smalle et al., 2003). In yeast, it was recently shown that Rpn10 targets the cell cycle regulator Sic1, which is ubiquitylated by the SCFCdc4 complex at the G1/S transition, to the 26S proteasome for degradation (Mayor et al., 2005).

Despite these advances, the detailed mechanism of action of the 26S proteasome is still poorly understood. In this article, we describe the isolation and characterization of mutants defective in RPN1 from Arabidopsis. RPN1 is encoded by two paralogous genes in Arabidopsis, called RPN1a and RPN1b. Disruption of RPN1a, but not RPN1b, caused embryo lethality, accumulation of cyclin B1 in the embryo, and seed abortion. Thus, the rpn1a mutant phenotype indicates an essential function of the 26S proteasome in the regulation of cell cycle progression and differentiation during plant embryogenesis. Both RPN1a and RPN1b genes are expressed during embryogenesis, but RPN1b is not able to rescue the RPN1a deficiency in planta, suggesting that the expression levels of the paralogs are different and/or that each subunit might have specific properties. Double mutants, hetereozygous for rpn1a and homozygous for rpn1b, have a phenotype similar to rpn1a single mutants, consistent with a nonredundant function of the two RPN1 isoforms during reproductive development. However, rescue of the rpn1a mutation by expression of the RPN1b coding sequence under the control of the RPN1a promoter indicates that two isoforms of RPN1 are functionally equivalent and that differences in their levels of expression may be responsible for the lack of redundancy.

RESULTS

The Arabidopsis Genome Contains Two RPN1 Genes

To identify the RPN1 gene of Arabidopsis, we performed BLAST searches (Altschul et al., 1997) of the Arabidopsis genome sequence (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000) using the yeast Rpn1 sequence as query. We found two predicted proteins with 36 and 32% amino acid identity to yeast RPN1p. We refer to them as RPN1a and RPN1b, respectively (Figure 1A), consistent with the nomenclature proposed by Yang et al. (2004). The RPN1a gene is located on chromosome 2 (At2g20580), while its paralog, RPN1b, is on chromosome 4 (At4g28470). The two genes appear to be located on chromosomal duplicated segments (Blanc et al., 2000, 2003; Vision et al., 2000) and exhibit 78% amino acid identity over their entire length. Based on records in the UniGene database of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/UniGene), both RPN1 genes are expressed in a wide range of tissues, with RPN1a mRNA being somewhat more abundant than RPN1b.

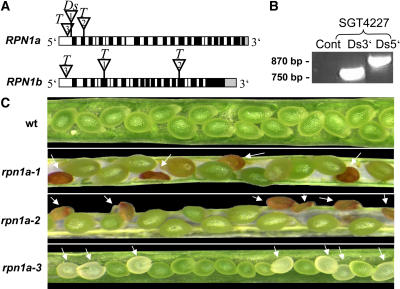

Figure 1.

RPN1 Mutant Alleles and rpn1a Phenotypes.

(A) Schematic representation of the RPN1a and RPN1b genes. RPN1a: insertion of the Ds element (triangle 1) in SGT4227 (rpn1a-1) into the ATG start codon in the first RPN1a exon; the T-DNA insertion (triangle 2) in SALK_12604 (rpn1a-2) disrupts the second exon of RPN1a; the T-DNA insertion in SALK_30503 (rpn1a-3) lies 300 bp upstream of the RPN1a gene coding region. RPN1b: the T-DNA insertion in SALK_115981 (rpn1b-1) disrupts the 5th exon and in SALK_061211 (rpn1b-2) the 17th exon of RPN1b, respectively; in SALK_023490 (rpn1b-3), the T-DNA inserted into the promoter region. Black boxes indicate exons, white boxes introns, and gray boxes the 3′ untranslated region.

(B) PCR analysis of the sequences spanning the 5′ and 3′ junctions of the Ds insertion in rpn1a-1.

(C) rpn1a mutants are embryo lethal. Wild-type siliques show full seed set, while in rpn1a-1, rpn1a-2, and rpn1a-3 heterozygous plants, one-quarter of the seeds abort (arrows).

Characterization of Insertional Mutants in RPN1a and RPN1b

To investigate the function of the Arabidopsis RPN1 genes, we identified insertion mutants from public insertion libraries (Parinov et al., 1999; Alonso et al., 2003). We characterized the gene trap line SGT4227 from the Singapore Collection with a disruption of the RPN1a gene. This mutant was generated using the Activator/Dissociation (Ac/Ds) gene trap transposon system developed by Sundaresan et al. (1995). The Ds element introduces a neomycin phosphotransferase gene (NPTII) conferring resistance to kanamycin as a dominant marker. PCR analysis with primers designed close to both ends of the Ds element and within the flanking sequences of the annotated RPN1a gene revealed bands of the expected size (Figure 1B), confirming that there is a clean insertion in RPN1, which is not associated with a deletion or other rearrangement (Page et al., 2004). Subcloning of these PCR fragments and sequencing showed that the Ds insertion is located in the ATG start codon (between nucleotides T and G) of the first RPN1a exon (Figure 1A).

A genomic DNA gel blot showed that a single Ds insertion is present in the SGT4227 line (data not shown), allowing us to use the kanamycin resistance marker for further genetic characterizations. A segregation analysis among the progeny of selfed heterozygous plants revealed that kanamycin-resistant to -sensitive seedlings were segregating in a ratio of 2:1 (Table 1), suggesting that the homozygous insertion is lethal and/or indicating reduced gametophytic transmission. To determine whether the insertion was transmitted normally through both male and female gametophytes, reciprocal crosses to the wild type were performed. The transmission efficiency of the kanamycin resistance marker was found to be normal through both gametophytes (Table 1). Taken together, these data suggest that SGT4227 carries an embryo lethal mutant linked to the Ds element. To confirm that embryos homozygous for the SGT4227 insertion abort, we analyzed mature siliques for the presence of aborted seeds (Figure 1C). Indeed, 24% of the embryos aborted, suggesting nearly complete penetrance of the embryo lethal phenotype (Table 2).

Table 1.

Segregation Ratio and Transmission Efficiency of the NPTII Gene Conferring Kanamycin Resistance in Transposant SGT4227

| Cross | Kanr | Kans | Total | P Value | TEF | TEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGT4227 selfed | 915 | 470 | 1385 | 0.63 | NA | NA |

| SGT4227/- × wild type | 61 | 62 | 123 | 0.93 | 98% | NA |

| wild type × SGT4227/- | 88 | 76 | 164 | 0.35 | NA | 116% |

Transmission efficiencies were calculated according to Howden et al. (1998): TE = Kanr/Kans × 100%; Kanr, kanamycin-resistant seedlings; Kans, kanamycin-sensitive seedlings; P value, based on an expected 2:1 or 1:1 Kanr:Kans segregation ratio, respectively; TEF, female transmission efficiency; TEM, male transmission efficiency. NA, not applicable.

Table 2.

Seed Abortion in Plants Carrying Different Alleles of rpn1a

| Allele | Normal Seeds | Aborted Seeds | Seeds Scored | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpn1a-1 | 76.0% | 24.0% | n = 1016 | 0.47 |

| rpn1a-2 | 77.6% | 22.4% | n = 459 | 0.20 |

| rpn1a-3 | 72.2% | 27.8% | n = 654 | 0.11 |

Mature seedpods were analyzed for the presence of aborted seeds. A P value of ≥0.05 was considered consistent with the hypothesis that 25% of the seeds abort as expected for a zygotic embryonic lethal mutation.

For RPN1b, we identified and analyzed three insertion lines from the SALK collection (Alonso et al., 2003): SALK_115981 and SALK_061211 with T-DNA insertions in exons 5 and 17, respectively, and SALK_023490 with a T-DNA insertion in the promoter region of RPN1b (referred to as rpn1b-1, rpn1b-2, and rpn1b-3, respectively, in Figure 1A). All three lines appeared wild-type, and the siliques analyzed showed full seed set (data not shown). Since insertions in the RPN1b gene did not display any obvious phenotypes, we concentrated our further characterization on the putative mutation in RPN1a.

Disruption of RPN1a Causes Zygotic Embryo Lethality

Our characterization of SGT4227 indicated that RPN1 might be essential to embryonic development in plants. To demonstrate a causal relationship between the Ds insertion in RPN1a and the observed phenotype, we performed further cosegregation analyses and used two additional genetic approaches: the phenotypic reversion of the putatively transposon-induced mutation and the isolation of additional mutant alleles. An analysis of >250 SGT4227 heterozygous plants showed that the kanamycin resistance marker and embryo lethality strictly cosegregate. Thus, the Ds element was tightly linked to the embryo lethal mutation present in SGT4227.

While cosegregation of the phenotype with the insertion suggests that the Ds element may cause embryo lethality, it does not constitute final proof. To demonstrate a causal relationship, we attempted to revert the phenotype through remobilization of the Ds transposon in SGT4227 by crossing it to a stable Ac line producing Ac transposase (Sundaresan et al., 1995). Different Ac lines were used in these crosses, as epigenetic silencing of Ac transposase has been observed (U. Grossniklaus, unpublished results). Of 24 mutant plants analyzed, 9 plants derived from crosses between SGT4227 heterozygotes and Ac4/Ac4 or Ac5/Ac5 male and female parents, respectively, were mosaic. As shown in Figure 2A, these plants produced both wild-type and mutant sectors. Some wild-type sectors encompassed an entire secondary branch. The fact that remobilization of the Ds element in RPN1a restored the wild-type phenotype strongly suggests that disruption of RPN1a causes embryo lethality. Therefore, we designated SGT4227 as rpn1a-1.

Figure 2.

Analysis of rpn1a-1 Revertant Sectors.

(A) Phenotype of a mosaic hybrid plant obtained from the cross between a Ac4/Ac4 female and a rpn1a-1/RPN1a male, showing siliques from a wild-type (top panel) and a phenotypic sector with aborted seeds (arrows, bottom panel).

(B) PCR analysis of genomic DNA from the phenotypic sector (lanes 3 and 4), the wild-type sector (lanes 5 and 6), and the rpn1a-1/RPN1a control plant (lanes 1 and 2). A fragment of 750 bp specific to the Ds insertion in the rpn1a-1 allele is missing due to excision of the Ds element (lane 5); the 1146-bp fragment specific to the Ds element is present in all samples shown.

(C) DNA sequences flanking the rpn1a-1 Ds insertion, which created a typical 8-bp direct target site duplication. The ATG start codon is underlined. In the revertant allele, one nucleotide was deleted at the 5′ junction and five nucleotides at the 3′ junction, leaving a typical Ds footprint of 2 bp. Excision removed the large insertion restoring the function of RPN1a.

To confirm the reversion at the molecular level, DNA from both mutant and wild-type sectors of the same plant were isolated. Genomic DNA from rpn1a-1 as well as mutant and wild-type sectors of a hybrid plant were amplified with primers specific to the Ds insertion in the rpn1a-1 allele (Figure 2B, 750-bp fragment in lanes 1 and 3) or primers specific to the Ds element (Figure 2B, 1146-bp fragment in lanes 2, 4, and 6). While a Ds element was detected in all samples, the rpn1a-1–specific band was not detectable in the reverted sector, confirming that the Ds element had excised from RPN1a.

To determine the molecular nature of the revertant allele, we first sequenced the 3′ and 5′ junctions of the Ds insertion. As typical for a Ds element, an 8-bp direct target duplication was generated upon insertion (Figure 2C). The target duplication resulted in a disruption of the 5′ untranslated region 6 bp upstream of a recreated ATG. To isolate the revertant allele, PCR fragments spanning the insertion site were amplified from DNA isolated from a revertant sector. As expected for a heterozygous plant, approximately half (6) of the sequenced clones showed a wild-type sequence and half (4) a revertant sequence. In the revertant allele, one nucleotide was deleted at the 5′ junction and five at the 3′ junction, leaving a typical Ds footprint (Rinehart et al., 1997), an insertion of two nucleotides (Figure 2C). The excision removed the large insertion immediately in front of the ATG start codon, restoring the function of RPN1a as evidenced by the phenotypic reversion in this sector.

To determine whether the embryo lethal phenotype of rpn1a-1 is representative of mutations in this gene and constitutes the null phenotype, we isolated additional mutant alleles. In the SALK collection, we found two lines with T-DNA insertions in the RPN1a gene (Figure 1A): SALK_12604 carries an insertion in the second exon (rpn1a-2), and SALK_30503 has a T-DNA insertion 300 bp upstream of the coding region of RPN1a (rpn1a-3). PCR-based genotype analyses of these lines confirmed that the annotated insertion sites were correct. Their phenotypes were characterized by assessment of green siliques for seed abortion (Table 2). Plants heterozygous for the two new alleles produced 22.4 and 27.8% aborted seeds, respectively, consistent with the mutations causing embryo lethality when homozygous. The similarity of phenotypes at the level of seed abortion and cytology (see below) suggests that embryo lethality of rpn1a mutants probably represents the null phenotype. Taken together, these genetic analyses strongly suggest that RPN1a activity is required for normal embryogenesis.

Embryos Homozygous for Mutations in RPN1a Arrest at the Globular Stage

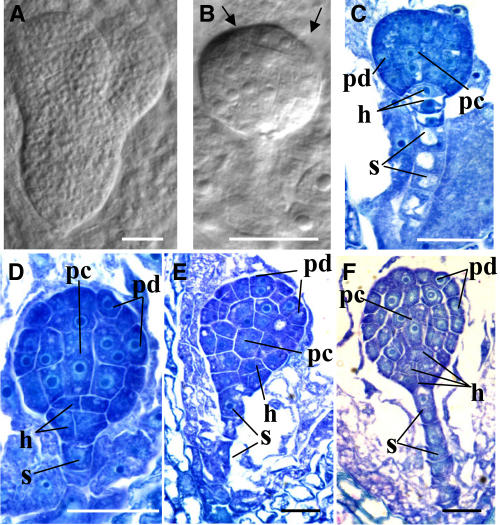

To determine the defects in homozygous rpn1a embryos at the cytological level, we performed light microscopic observations on cleared seeds (Figures 3A and 3B) and sectioned material (Figures 3C to 3F). Analysis of cleared specimen showed that siliques harboring torpedo stage wild-type embryos (Figure 3A) contained ∼25% rpn1a-1/rpn1a-1 mutant embryos arrested at the globular stage (Figure 3B). The same stage of arrest was also observed for rpn1a-2 and rpn1a-3 (data not shown). Therefore, our further analyses concentrated on the rpn1a-1 allele. Embryo development in mutant rpn1a-1 seeds clearly deviated from the normal Onagrad-type of embryogenesis typical of the Brassicaceae family (Johansen, 1950). Arrest of embryogenesis occurred predominantly at the globular stage (Figures 3A and 3B) with (1) premature division of the hypophyseal cell (cf. embryo in Figure 3D with the wild type in Figure 3C, both embryos are from the same silique), (2) underdeveloped, less vacuolated suspensor cells (Figures 3D and 3E), (3) abnormalities in protoderm formation (Figures 3B and 3D to 3F), and (4) abnormalities in procambial cell divisions (Figures 3D to 3F). Moreover, the cells in mutant rpn1a-1 embryos seemed less tightly adjoined to each other than in the wild type as evidenced by the large apoplastic spaces between cells (Figures 3D to 3F).

Figure 3.

Seed and Embryo Development in rpn1a-1/RPN1a Plants.

(A) and (B) Cleared seeds from the same silique: torpedo stage of a wild-type seed (A), aborted seed with the embryo arrested at the globular stage (B). Note the irregular protoderm layer (arrows).

(C) to (F) Toluidine blue–stained sections of a wild-type embryo at the early globular stage (C) and rpn1a-1 mutant embryos at the globular stage with abnormalities described in the text ([D] to [F]). h, derivatives of hypophyseal cell; pc, procambial cells; pd, protoderm; s, suspensor.

Bars = 25 μm in (A) and 50 μm in (B) to (F).

In order to compare the developmental progression of mutant and wild-type embryos, we hand-pollinated flowers of both mutant and wild-type plants with self-pollen and investigated cleared specimens under differential interference contrast (DIC) optics at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 d after pollination (DAP; Table 3). In general, the development of embryos in rpn1a mutant siliques was somewhat delayed and less synchronous within a silique than in the wild type. Already at 1 DAP the number of embryos at the two- to four-celled stage was increased by 14% in the siliques of heterozygous rpn1a-1 mutants as compared with the wild type, with a concomitant decrease of 13% in the number of embryos at the octant to dermatogen stage. At this early stage also the first deviations from normal ontogeny become apparent. While wild-type embryos have a seven- to eight-celled suspensor, rpn1a-1 mutants had suspensors consisting of only two to five cells. Once a wild-type globular embryo consists of 32 cells (2 to 3 DAP), the uppermost suspensor cell becomes incorporated into the embryo proper. This so-called hypophyseal cell divides once periclinally and then remains mitotically inert until further divisions occur at the heart stage. In mutant embryos of the same silique, however, the hypophyseal cell had already undergone two or more divisions. The derivatives of the hypophyseal cell in mutant embryos had a denser cytoplasm, were larger than those of wild-type embryos, and showed less regular division planes (Figure 3D). At the same stage, the procambium is formed from the inner embryonic cells. In wild-type embryos, eight narrow procambial cells situated in two layers were directly apical to the two hypophyseal cell derivatives. By contrast, rpn1a mutant embryos in the same silique had only one or two elongated procambial cells apical to the multiple derivates of the hypophyseal cell (cf. Figures 3C and 3D). Despite these abnormalities, mutant embryos developed further until they arrested predominantly at the globular stage as evidenced by the fact that at 4 and 5 DAP, the number of globular embryos was increased by 21 and 28%, respectively, in the siliques of heterozygous rpn1a-1 mutants as compared with the wild type (Table 3).

Table 3.

Developmental Progression of Embryogenesis in Wild Type and rpn1a Heterozygous Plants

| DAP | Zygote | First Division | Two- to Four-Celled Embryo | Octant-Dermatogen Stage | Globular Embryo | Early Heart Embryo | Late Heart Embryo | Torpedo Embryo | No. of Seeds Examined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type plants | |||||||||

| 1 | 6% | 7% | 29% | 58% | – | – | – | – | 144 |

| 2 | 5% | – | 9% | 53% | 33% | – | – | – | 92 |

| 3 | 2% | – | 1% | 5% | 38% | 54% | – | – | 191 |

| 4 | 2% | – | – | – | 14% | 33% | 51% | – | 111 |

| 5 | – | – | – | – | – | 13% | 36% | 51% | 124 |

| rpn1a heterozygous plants | |||||||||

| 1 | 5% | 7% | 43% | 45% | – | – | – | – | 130 |

| 2 | 5% | 2% | 18% | 54% | 21% | – | – | – | 136 |

| 3 | 2% | – | 2% | 26% | 42% | 28% | – | – | 235 |

| 4 | 2% | – | 1% | 7% | 35% | 47% | 8% | – | 119 |

| 5 | – | – | – | – | 28% | 9% | 7% | 56% | 53 |

Flowers of both mutant and wild-type plants were pollinated with self-pollen, fixed at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 DAP, cleared, and observed under DIC optics.

In summary, our data suggest that rpn1a homozygous embryos are developmentally delayed and show abnormal cell division patterns leading to a less synchronized seed development. The defects observed in rpn1a-1 mutant embryos suggest that RPN1a is involved in the regulation of cell division planes, as we observed irregularly oriented divisions in protoderm and procambial cells. Moreover, RPN1a seems both to restrict cell proliferation (e.g., in the hypophysis and the protoderm where we saw extra divisions in mutant embryos) and to promote cell proliferation, as evidenced by the reduced divisions of suspensor and procambial cells.

rpn1a Mutant Embryos Are Defective in Cell Cycle Progression

In order to better define the mutant phenotype of rpn1a-1 embryos with respect to cell cycle control, we analyzed whether the mutant affects cell cycle progression. The rpn1a-1 mutant was crossed to a marker line expressing a CyclinB1;1-β-glucuronidase (GUS) fusion protein. Mitotic CyclinB1;1 is known to be expressed only during the G2/M transition of the cell cycle (Colón-Carmona et al., 1999). The fusion protein contained a cyclin destruction box that leads to the degradation of the protein at the end of M phase (de Almeida Engler et al., 1999; Donnelly et al., 1999). Young seeds just after fertilization, which undergo numerous mitotic divisions, showed elevated levels of CyclinB1;1-GUS activity. A fraction of the embryos showed increased levels of staining at this stage consistent with the early phenotypes observed (data not shown). Later in development, 75.2% of the embryos (n = 351) showed an undetectable to weak level of CyclinB1;1-GUS expression (Figure 5Q), typically with staining in just a few individual cells (data not shown). By contrast, 24.8% of the embryos accumulated high levels of CyclinB1;1-GUS. These embryos arrested at the globular stage and, thus, represented the homozygous rpn1a-1 mutants.

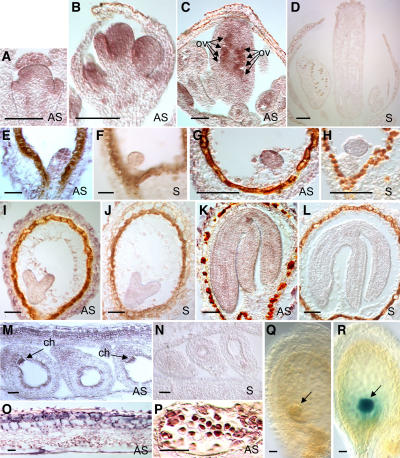

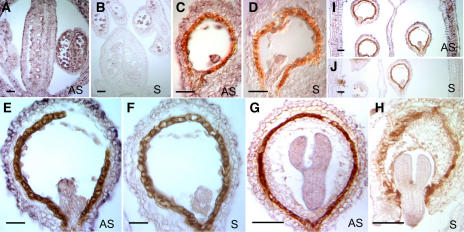

Figure 5.

In Situ Detection of RPN1a mRNA in Developing Flowers, Seeds, and Siliques and cyclinB1;1 Expression in the rpn1a-1 Mutant.

(A) to (D) Longitudinal sections of a floral meristem and flower buds at various stages.

(E) and (F) Embryo at the octant stage.

(G) and (H) Embryo at the globular stage.

(I) and (J) Embryo at the late heart stage.

(K) and (L) Embryo at the walking stick stage.

(M) to (O) Fragment of a silique.

(P) Tetrads of microspores. The hybridization signal appears as dark staining.

(Q) Embryo carrying at least one wild-type RPN1a allele. The cyclinB1;1-GUS fusion protein is degraded and barely detectable in the embryo (arrow).

(R) rpn1a-1 homozygous mutant embryo from the same silique as in (Q) accumulates cyclinB1;1-GUS fusion protein (arrow).

AS, antisense probe; S, sense probe; ch, chalaza; ov, ovules. Bars = 25 μm in (A), (B), (E) to (H), (O), and (P) and 50 μm in (C), (D), and (I) to (N).

These data indicate that CyclinB1;1-GUS degradation does not occur in rpn1a-1 homozygous embryos and suggest that the cells may be arrested in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, where the CyclinB1;1 protein level is expected to be high.

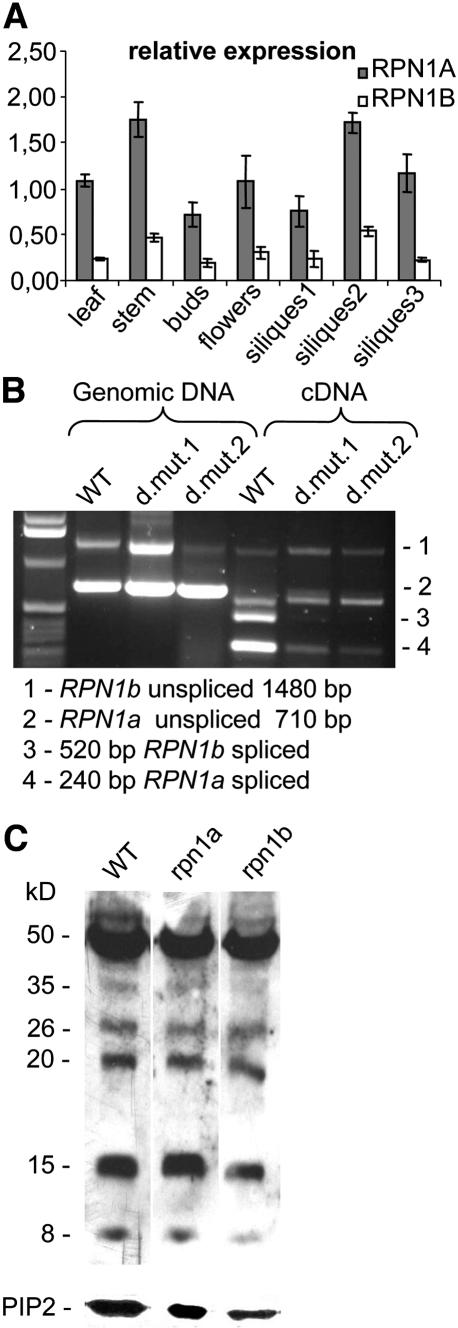

The RPN1 Genes Are Expressed in Vegetative and Reproductive Organs

To gain insight into the spatial and temporal expression pattern of the RPN1 genes, we performed quantitative RT-PCR with RNA isolated from leaves, stems, floral buds, open flowers, and siliques at three stages of development (Figure 4A). Both RPN1 genes are expressed in all organs tested but show a higher level of expression in stem tissue and siliques containing embryos at approximately the globular stage. Strikingly, the level of RPN1a expression is threefold to fivefold higher than that of RPN1b in all tissues analyzed.

Figure 4.

Expression and Function of the RPN1 Genes in the Wild Type and Mutants.

(A) Relative RPN1a and RPN1b transcript accumulation in wild-type tissues. Both transcripts were detected in vegetative and reproductive tissues. RPN1a was consistently expressed at higher levels than RPN1b. Data are presented as values relative to 18S RNA expression. Identical results were obtained using ACTIN1 as a reference gene (data not shown). Error bars represent sd on the basis of three biological replicates.

(B) RT-PCR analysis for expression of the RPN1a and RPN1b genes in double mutants heterozygous for rpn1a-1 and homozygous for rpn1b-2 and rpn1b-3, respectively (here indicated as d.mut.1 and d.mut.2). No RPN1b mRNA is detected in the double mutants, and RPN1a mRNA levels are reduced compared with the wild type, likely due to heterozygosity.

(C) Polyubiquinated proteins in siliques from the wild type, rpn1a/RPN1a, and rpn1b/rpn1b mutants. Total protein was separated on a gel and transferred to a membrane, and polyubiquinated proteins were detected using a polyclonal antiubiquitin antibody. The bottom panel shows the AtPIP2b plasma membrane protein as loading control. The position of molecular mass marker is shown at the left (in kD).

Given that RPN1a is abundantly expressed in reproductive tissues and rpn1a mutants affect embryogenesis, we determined its expression pattern at the cellular level in developing flowers and seeds. To this aim, we performed in situ hybridization experiments on sections of flower buds and siliques using RPN1a-specific antisense and sense control probes (Figure 5). The RPN1a expression pattern can be summarized as follows: Transcripts were detected in the floral meristem and primordia of floral organs, which showed a somewhat higher expression level in the adaxial part of the primordia (Figures 5A and 5B). During early stages of flower development, transcripts were detected in the whole floral meristem with low levels in the sepals. Particularly strong signals were observed in emerging primordia (Figure 5B). Later on, a prominent signal was detected in developing carpels, especially in emerging ovule primordia (Figure 5C). After fertilization, the RPN1a expression was observed in the embryo (Figures 5E to 5L) and the chalazal endosperm (Figure 5M). Early in seed development, for instance in embryos of the octant (Figure 5E) and globular stages (Figure 5G), the signal intensity was high but decreased at later stages (Figures 5I to 5L). From the late heart stage (Figure 5I) onwards, the RPN1a transcript level in the embryo was low, and the signal obtained with the antisense probe was only slightly stronger than that of the sense control (Figure 5J). Nevertheless, up to the walking stick stage, we consistently obtained somewhat higher signals with the antisense (Figure 5K) than with the sense probe (Figure 5L). Signal was also observed in the developing seed coat, the septum, and, rather strongly, in the silique wall (Figures 5M and 5O).

In the stamens, RPN1a transcripts were detected at high levels in the anthers but not in the filaments (data not shown). A strong signal was observed in sporogenous cells and then in tetrads of microspores (Figure 5P), whereas only background levels were detected in parietal and tapetal tissues. After the release of pollen from the tetrads, the hybridization signal was very faint in the free microspores and barely above background in three-celled pollen (data not shown).

The recovery of RPN1b ESTs from different tissues suggested that it was also widely expressed, possibly in a pattern overlapping with that of RPN1a. To visualize the expression pattern of the paralogous RPN1b gene in flowers and seeds, we performed in situ hybridization experiments using an RPN1b-specific probe. An analysis of hybridized sections of flower buds and seeds of different developmental stages provided the following results: RPN1b transcripts were detected in the entire flower with strong signals in carpels, especially in differentiating ovules and the carpel wall (Figure 6A). The signal appears patchy and was very strong in particular cells. Such dotted patterns are typical for cell cycle–regulated genes (e.g., Fobert et al., 1994; Lukowitz et al., 1996) and may reflect differential regulation of RPN1b during the cell cycle. In anthers, transcripts were present at a high level in tetrads of microspores and the tapetum (Figure 6A). After fertilization, the strongest signal was observed in the embryo up to the heart stage (Figures 6C to 6F) and in the chalazal endospem (Figure 6I). From the late heart stage onward, the amount of RPN1b transcripts in the embryo was very low, and the signal detected by the antisense probe was only slightly stronger than that of the sense control (Figures 6G and 6H). A faint signal was observed in the developing seed coat and the septum, while the silique wall showed high levels of expression at all stages of carpel development (Figure I).

Figure 6.

In Situ Detection of RPN1b mRNA in Developing Flowers, Seeds, and Siliques.

(A) and (B) Longitudinal sections of a flower.

(C) and (D) Embryo at the octant stage.

(E) and (F) Embryo at the globular stage.

(G) and (H) Embryo at the torpedo stage.

(I) and (J) Fragment of a silique. Hybridization signal appears as dark staining.

AS, antisense probe; S, sense probe. Bars = 25 μm in (C) to (F) and 50 μm in (A), (B), and (G) to (J).

In summary, these data suggest that the RPN1 paralogs are expressed differentially but in a largely overlapping pattern during flower and seed development. Expression levels are high in, but not restricted to, early stages of embryogenesis when the developmental arrest is observed in the rpn1a mutants.

RPN1a and RPN1b Do Not Share Redundant Functions

Analysis of the RPN1a and RPN1b expression patterns showed that these paralogous genes are expressed in a partially overlapping pattern and, therefore, may function redundantly. Genetic analyses showed that mutations in RPN1a lead to embryo lethality, while RPN1b mutants showed no obvious phenotypes. As the proteasome plays a crucial role in the control of cell division, we were surprised that development of the haploid gametophytes, which undergo two or three mitotic divisions, respectively, was not affected in the rpn1a mutants. This could be due to either (1) partial loss of function in the rpn1a alleles we studied, (2) perdurance of RPN1a protein or proteasome particles for several cell division cycles, or (3) genetic redundancy between RPN1a and RPN1b. To distinguish between these possibilities, we first determined whether the rpn1a and rpn1b alleles we studied are null alleles. The demonstration of this point is crucial for the interpretation of double mutant phenotypes, which provide information about functional redundancy.

Because mutations in RPN1a are homozygous lethal, we could not analyze the expression levels in the mutant by conventional methods such as RT-PCR. Rather, we performed in situ hybridization experiments on sections of developing seeds from an rpn1a-1/RPN1a-1 plant. We analyzed seeds up to the globular stage and found that 26.9% of the seeds (n = 67) showed no detectable signal when using a RPN1a-specific antisense probe (data not shown), while the wild-type control showed a clear signal in globular stage embryos. In the remaining 73.1% of the seeds, which likely correspond to RPN1 heterozygotes and wild-type embryos, a signal could be detected with the antisense RPN1a probe. Maternal tissues, such as the seed coats and carpel walls, showed an intensity of the signal comparable to the wild type (data not shown).

To characterize the rpn1b mutants at the molecular level, we performed RT-PCR experiments to investigate whether the T-DNA insertions did indeed create null alleles as expected. As shown in Figure 4B, no expression of RPN1b could be detected in flowers from two double mutant lines that were heterozygous for rpn1a-1 and homozygous for rpn1b-2 or rpn1b-3, respectively. These expression studies strongly suggest that the rpn1a and rpn1b alleles we used were indeed null alleles providing no residual RPN1 activity.

To investigate whether the two RPN1 paralogous genes are functionally redundant, we analyzed seed abortion and embryo lethality in the double mutants described above. No significant difference in the percentage of aborted seeds was observed if rpn1b was mutated in addition to rpn1a (23% aborted seeds in rpn1a-1/RPN1a rpn1b-3/rpn1b-3, n = 846 seeds and 21% aborted seeds in rpn1a-1/RPN1a rpn1b-1/rpn1b-1, n = 450 seeds), and embryonic arrest occurred at the same stage as in the rpn1a-1 single mutant (data not shown). Thus, the double mutant did not show a stronger phenotype (e.g., an arrest during megagametophyte development or early embryogenesis). This finding strongly suggests that there is no functional redundancy between RPN1a and RPN1b with respect to reproductive development where RPN1a plays a crucial role. Therefore, the RPN1 subunits of the proteasome either play no essential role prior to the globular stage of embryogenesis or, more likely, RPN1a is a rather stable and abundant protein that persists after meiosis over several division cycles in the gametophytes and during early seed development.

In order to reveal possible functional differences between the paralogous RPN1 genes, we investigated the general level of ubiquitination in siliques containing globular embryos. In the absence of functional 26S proteasomes, the number and/or level of polyubiquinated proteins should increase. Polyubiquinated proteins were analyzed in rpn1a/RPN1a plants, where homozygous mutant embryos may fail to degrade ubiquinated substrates, and in rpn1b/rpn1b homozygotes (Figure 4C). If proteasome function were impaired in the mutants, this should affect the level of polyubiquitinated proteins, as it was described, for instance, after application of 26S proteasome inhibitors, which is accompanied by a drastic elevation in the general level of polyubiquitinated proteins (Speranza et al., 2001). Although the rpn1a mutant cells only constitute a small fraction of the cells from which protein extracts were made, a failure to degrade highly unstable substrates is expected to lead to changes in the profile of polyubiquitinated proteins (e.g., the appearance of new bands). We could not detect any difference in the total level of polyubiquitinated proteins between either of the two mutants and the wild type. This finding indicates that proteasome function on the whole was not effectively impaired in the mutants and that the RPN1 isoforms may have rather specific functions leading to subtle changes. It is possible that the rpn1 mutants affect only a subset of specific substrates, rather than all polyubiquinated proteins, and these are not detectable in this assay.

The Two Isoforms of RPN1 Are Functionally Equivalent

The experiments showing that the two isoforms of RPN1 are nonredundant during reproductive development did not address the question whether these highly similar paralogous genes are functionally equivalent. Several reasons could explain why the RPN1b gene is unable to complement the rpn1a mutation during gametogenesis and embryogenesis, for instance, differences in the level or pattern of expression of the two genes. Moreover, it is also possible that the two RPN1 isoforms have distinct functions, for instance, with respect to substrate specificity.

In order to test whether the two RPN1 isoforms are functionally equivalent, we attempted to complement the rpn1a-1 mutant with constructs expressing either the RPN1a or RPN1b cDNA under the control of the RPN1a promoter (pRPN1a), respectively. Moreover, we used the ubiquitous 35S promoter from Cauliflower mosaic virus (p2x35S) to drive RPN1a expression. The promoter exchange experiments showed that all three constructs could complement rpn1a-1 mutation, as evidenced by a reduced level of seed abortion (Table 4). However, the success rate of complementation varied between rpn1a heterozygous plants carrying the different constructs. Of 16 plants carrying the p2X35S-RPN1a construct, 9 plants showed a phenotype similar to rpn1a (∼25% aborted seeds), while in 7 plants, the phenotype was partially rescued (seed abortion ranging from 15.6 to 2.5%). Of 15 plants carrying the pRPN1a-RPN1a construct, only 2 plants showed the rpn1a phenotype, while in the remaining 13 plants, seed abortion varied from 18 to 2%. Of 13 plants carrying the pRPN1a-RPN1b construct, 7 plants showed the rpn1a phenotype, and 6 plants had a reduced seed abortion ranging from 11.7 to 1.7%.

Table 4.

Seed Abortion in Complemented rpn1a-1/RPN1a Plants

| Complementation Construct | Plant | Normal Seeds | Aborted Seeds | TotalSeeds Scored | No. of T-DNA Copies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p2x35S-RPN1a | 16 | 94.8% | 5.2% | 224 | 3 |

| 19 | 87.9% | 12.1% | 198 | 1 | |

| 21 | 86.0% | 14.0% | 262 | 3 | |

| pRPN1a-RPN1a | 26 | 87.6% | 12.4% | 239 | 5 |

| 27 | 92.0% | 8.0% | 191 | 2 | |

| 28 | 98.0% | 2.0% | 188 | 4 | |

|

pRPN1a-RPN1b

|

29 | 94.7% | 6.3% | 202 | 4 |

| 34 | 88.3% | 11.7% | 214 | 1 | |

| 35 | 98.3% | 1.7% | 226 | 6 |

Mature siliques were analyzed for the presence of aborted seeds. The copy number of T-DNA insertions was determined using DNA gel blots.

The different degrees of seed abortion observed in rpn1a heterozygous plants carrying the individual constructs are likely due to the number of segregating complementation constructs and/or their chromosomal location. To assess the number of the complementation constructs, we performed DNA gel blot analysis (data not shown) for three independent lines of each construct that differed in their level of seed abortion (Table 4). In a line carrying a single copy of the complementation construct, seed abortion in the T2 generation is expected to be reduced to ∼12.5%, if the rpn1a mutation and the complementation construct segregate independently. If a line has two independently segregating copies of the construct, seed abortion is expected to be ∼6.25%, etc. In the lines we tested, there was a clear trend showing a lower frequency of seed abortion with an increasing number of the complementation constructs (Table 4). For instance, we observed 12.1 and 11.7% aborted seeds in lines with a single copy (plants 19 and 34) or 8 and 5.2% of aborted seeds in lines with two or three copies, respectively (plants 27 and 16). These observed seed abortion rates are consistent with one, two, or three fully complementing, independently segregating complementation constructs (P values ranging from 0.12 to 0.83). However, the number of complementation constructs was not always correlated with the reduction of seed abortion. This may be due to the position of the insertion, gene silencing, or tandem insertion of the complementation constructs.

Taken together, these promoter exchange experiments show that the two isoforms of the RPN1 gene can functionally replace each other if expressed under the appropriate promoter. In planta, however, the two genes do not act redundantly, at least during the reproductive phase of development.

DISCUSSION

The 26S proteasome is essential in a myriad of cellular processes, which are controlled by the selective degradation of proteins that have been tagged with ubiquitin (Voges et al., 1999; Vierstra, 2003). As such, the proteasome can be considered as the last step in the life cycle of many regulatory proteins. Until recently, the selectivity of the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway was thought to rely on the ubiquitination reaction. In this mechanism, the E3 ubiquitin ligases play the key role in substrate selection because they bind to both the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and to unique signals present in the protein substrates to catalyze the transfer of ubiquitin (Ciechanover et al., 2000; Pickart, 2004). However, recent genetic analyses also suggest that the RP of the 26S proteasome contributes to this specificity (Vierstra, 2003; Mayor et al., 2005). Mutants affecting individual Arabidopsis RP subunits display a wide range of phenotypes, consistent with each participating in the destruction of distinct sets of substrates. Thus, the 26S proteasome might distinguish among its substrates and presumably use different routes for entry (van Nocker et al., 1996; Bailly and Reed, 1999; Smalle et al., 2002, 2003). For example, a mutant affecting RPN12a confers decreased sensitivity to cytokinins, whereas a mutant affecting RPN10 confers hypersensitivity to abscisic acid. Furthermore, the rpn10-1 mutant is able to degrade HY5 and PHYA normally but dramatically stabilizes the abscisic acid–response regulator ABI5, showing that rpn10-1 only affects a subset of ubiquitin/26S proteasome substrates (Smalle et al., 2003). In yeast, it has been shown that RPN10 contributes to the turnover of the cell cycle regulator Sic1 and the transcriptional activator Gcn4 (Mayor et al., 2005). Interestingly, in Arabidopsis, most of the RP subunits are encoded by two paralogous subunits, leading to the hypothesis that plants might synthesize multiple 26S proteasome forms with unique properties and/or substrate specificities (Yang et al., 2004).

To get more insights into the function of 26S proteasome RP subunits, we investigated one of its largest subunits: RPN1. The RPN1 subunit belongs to the base complex of the RP and is known to physically interact with two proteins carrying ubiquitin-like domains, Rad23 and Dsk2 in yeast (Elsasser et al., 2002). Moreover, the RPN1 subunit also binds the deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6 (Leggett et al., 2002). In Arabidopsis, mutations in the ubiquitin-specific protease UBP14, which is possibly involved in the recycling of polyubiquitin chains after degradation, cause embryo lethality at the globular stage but show a phenotype distinct from that of rpn1a (Doelling et al., 2001; Tzafrir et al., 2002). It has been proposed that RPN1 may serve as a platform for the assembly of proteins that bind or hydrolyze polyubiquitin chains (Elsasser et al., 2004). Nevertheless, the interference with polyubiquitin recycling may have feedback effects on the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. For all these reasons, the RPN1 subunit might directly participate in proteasome regulation and/or target specificity. Whereas this gene is essential in budding yeast (Hampton et al., 1996) and fission yeast (Wilkinson et al., 1997), to our knowledge, no rpn1 mutant has yet been described in a higher eukaryote. The most surprising findings of this work were (1) the loss-of-function rpn1 mutants were able to accomplish gametogenesis and the earliest phase of embryogenesis, and (2) the absence of functional redundancy between RPN1a and RPN1b in reproductive development despite the functional equivalency of two RPN1 isoforms.

RPN1a but Not RPN1b Is Required for Normal Embryogenesis

In Arabidopsis, two related genes, RPN1a and RPN1b, encode the RPN1 subunit. Both genes are expressed and the fact that their expression patterns exhibit some differences suggests that certain functions might not be totally redundant (Yang et al., 2004). During embryogenesis, the expression profiles of both genes were very similar, as revealed by in situ hybridization. Both RPN1a and RPN1b were detected in the seeds with the strongest signals in the chalazal endosperm and the embryo up to the late globular stage. Then, at the heart, torpedo, and walking stick stages, hybridization signals were significantly reduced and only slightly above background level. These expression patterns suggest that RPN1a and RPN1b genes play a critical function(s) during early embryogenesis.

Indeed, we observed that the disruption of the RPN1a gene causes embryo lethality with abortion of ∼25% of the seeds. The rpn1a mutation is segregating as a recessive monogenic trait. Embryonic lethality caused by disruption of the RPN1a gene was confirmed by the reversion of the mutant phenotype after transposon excision, as well as the isolation of two additional mutant alleles with a similar phenotype. Homozygous rpn1a embryos arrested at the globular stage due to deviation from the normal pattern of Onagrad-type embryogenesis peculiar to Arabidopsis and other Brassicaceae. The arrested embryos did not show any sign of asymmetric growth, characteristic of bilateral differentiation (Laux and Jürgens, 1997). Cytological analysis indicated that the developmental arrest of rpn1a embryos was accompanied by the combination of several factors, such as premature division of the hypophyseal cell, abnormalities in the suspensor region, and disturbances in protoderm and procambial cell divisions. Therefore, the RPN1 subunit might play an important role in the control of cell cycle progression and differentiation during embryogenesis.

One of the well-established functions of the plant ubiquitin/proteasome pathway is in auxin signaling (Hellmann and Estelle, 2002). In this pathway, auxin promotes the breakdown of certain auxin/indole-3-acetic acid repressor proteins, which are believed to block the auxin-response factors. Auxin seems to play an essential role during embryogenesis. In Arabidopsis, a loss-of-function mutant in the auxin binding protein ABP1 is arrested at the globular stage and is unable to make the transition to a bilateral embryo (Chen et al., 2001). In the axr6 homozygous mutant, embryonic development is disrupted, which is accompanied by aberrant patterns of cell division (Hobbie et al., 2000). Moreover, the embryo patterning mutants, bodenlos (bdl) and monopteros (mp), mutated in auxin/indole-3-acetic acid and auxin-response factor genes, respectively, are severely affected during embryo development (Hardtke and Berleth, 1998; Hamann et al., 2002). In bdl mutants, the hypophysis develops abnormally (Hamann et al., 1999). Although homozygous bdl embryos do not arrest at the globular stage, the bdl phenotype shows similarities to that of rpn1a mutant embryos: the hypophysis makes additional periclinal divisions, suggesting that BDL or other proteins involved in auxin signaling may be substrates of RPN1a.

Another mutant providing a possible link to hypophyseal cell development and auxin signaling is hobbit (hbt), in which root meristem formation is abnormal (Blilou et al., 2002). From the quadrant stage onward, the hypophyseal cell of hbt embryos develops abnormally (Willemsen et al., 1998). At the heart stage, cells adjoining the hypohyseal cell develop aberrantly, such that the formation of a lateral root cap is disturbed. However, unlike rpn1a, hbt mutants complete embryogenesis, but hbt seedlings lack the quiescent center and columella root cap cells, the cell types derived from the hypophyseal cell. The HBT gene encodes a protein homologous to the CDC27 subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC). In hbt mutants, the AXR3/IAA17 repressor accumulates with a concommitant reduction in the expression of the DR5-GUS auxin reporter gene (Blilou et al., 2002). Thus, HBT may link cell division to cell differentiation by regulating the response of dividing cells in the root meristem to auxin.

Based on the fact that like bdl, mp, and hbt, rpn1a affects the development of the hypophyseal cell, it is conceivable that plants impaired in 26S proteasome function are disturbed in auxin signaling, causing abnormal development and arrest of the embryo at the globular stage. However, the 26S proteasome is involved in many other cellular processes, which may cause embryo lethality. For example, in budding yeast, RPN1 is involved in the degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (Hampton et al., 1996). In plants, this enzyme acts at the top of complex biosynthetic pathways producing many important molecules, including sterols. A role for sterols in plant embryogenesis has already been established, and it was found that defects in sterol biosynthesis affect embryo development, already at the globular stage (Schrick et al., 2000).

Interference with Protein Ubiquitination but Not RPN1 Function Disrupts Gametogenesis

Critical functions of the 26S proteasome in controlling the cell cycle have been demonstrated in both yeast and animals (Reed, 2003), especially at the G1/S and G2/M phase transitions. Similar functions may exist in plants, and at least D-type and mitotic cyclins seem to be degraded by the 26S proteasome (Criqui and Genschik, 2002; Planchais et al., 2004). The control of the cell cycle is mainly exerted at the level of two E3 ligases, the SCF and APC/C complexes (Reed, 2003). Arabidopsis loss-of-function mutants of APC/C components are arrested during female gametogenesis (Capron et al., 2003; Kwee and Sundaresan, 2003), whereas the knockout of the CUL1 gene, which is a component of the SCF complex, arrests embryogenesis at the zygote stage (Shen et al., 2002). In agreement with these findings, we have found that the rpn1a homozygous mutant accumulates the cyclinB1;1-GUS fusion protein at high levels in the arrested embryos. Overaccumulation of B1-type cyclins in plant cells, due to a mutation in the degradation signal, has recently been shown to induce cell cycle defects (Weingartner et al., 2004). It is noteworthy that many other cell cycle regulatory proteins might also be stabilized in the rpn1a mutants, which could explain alterations in cell cycle progression.

As discussed above, different mutants in genes encoding ubiquitin E3 ligases were shown to be impaired in gametogenesis and/or the first division of the zygote (Shen et al., 2002; Capron et al., 2003; Kwee and Sundaresan, 2003; Zhao et al., 2003). It seems rather unlikely that these steps in the plant life cycle do require ubiquitination without degradation. It is therefore surprising that the rpn1a rpn1b double mutant did not show an earlier phenotype during gametogenesis or the first divisions of embryo development. We propose that the 26S proteasome is still, at least partially, functional during gametogenesis and the very early stages of embryogenesis and that the depletion of its activity only results in the arrest at the globular stage of embryo development. Cyclin B1 overaccumulation argues in favor of the proteolytic defect in the rpn1a mutant at this stage. Alternatively, gametophyte development may involve other proteolytic systems that can compensate for the loss of proteasome function, as was described in human (Glas et al., 1998).

RPN1a and RPN1b Are Functionally Equivalent but Act Nonredundantly during Reproductive Development

While mutations in RPN1a cause embryo lethality at the globular stage, RPN1b does not seem to play an essential role at any stage of development. Of course, the early embryonic lethality of rpn1a homozygotes does not mean that the RPN1 isoforms function exclusively at this stage of development, and a functional overlap of the two isoforms at later stages cannot be excluded. It is likely that they also regulate protein degradation at other stages, which, however, cannot be analyzed due to the embryonic lethality of rpn1a.

Because an analysis of double mutant rpn1a/RPN1a rpn1b/rpn1b embryos did not reveal a more severe effect than the rpn1a single mutant, a functional complementation by the paralogous RPN1b gene can be excluded for this phase of the life cycle. However, complementation of the rpn1a-1 mutant by both RPN1a and RPN1b under the control of the pRPN1a promoter shows that the two isoforms are functionally equivalent if expressed identically.

Although RPN1a and RPN1b show significant, if not strong, conservation at the amino acid level and both genes show a similar expression pattern during seed development, the RPN1b gene was clearly unable to substitute for a loss of RPN1a function during embryogenesis. This could be due to differences in the pattern or level of expression of the paralogs. Although subtle differences in their cellular expression patterns or cell cycle regulation could be responsible for the lack of redundancy, the simplest explanation is the low level of expression of RPN1b in comparison to RPN1a, which is expressed at threefold to fivefold higher levels in all tissues examined. It is likely that in planta, RPN1a, but not RPN1b, interacts with specific substrates that are essential during embryogenesis, although RPN1b can take over this function if expressed under the control of the pRPN1a promoter. Subtle differences in expression level or timing could be important in the assembly of specific 26S proteasome isoforms. The existence of different 26S proteasome isoforms in plants has already been suspected (Yang et al., 2004). The Arabidopsis rpn1 mutants described here can serve as the entry point for further investigations into 26S proteasome isoforms, the roles of the RP in the ubiquitin/ 26S proteasome pathway, and its function in plant development.

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The wild-type strain was Arabidopsis thaliana Heynh. var Landsberg (erecta mutant). The SGT4227 line was in the Landsberg erecta background, while the T-DNA insertion lines from the SALK collection were in the Columbia background. Plants were grown on soil ED73 mit Bims (Universal Erde) in a growth room with 70% relative humidity and a day–night cycle of 16 h light at 21°C and 8 h darkness at 18°C. For crosses with dehiscent anthers, closed flower buds were emasculated 1 or 2 d before pollination.

Histological Analysis

For phenotypic characterization, seeds were cleared with chloral hydrate following the protocol of Yadegari et al. (1994). Specimens were observed using a Leica DMR microscope (Leica Microsystems) under DIC optics. For preparation of semithin sections, plant siliques were fixed overnight in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PHEM buffer (60 mM Pipes, 25 mM Hepes, 10 mM EGTA, and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.9) on ice. Specimen were dehydrated in an ethanol series (30, 50, 70, 80, 90, 95, and 3× 100%) and transferred into Technovit 7100 (Heraeus Kulzer) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The tissue was sectioned at 8-μm thickness on a Leica RM 2145 microtome. After staining with 0.05% Toluidine blue, sections were observed under bright-field optics using a Leica DMR microscope.

Segregation Analysis

Seeds were surface sterilized and plated onto Murashige and Skoog medium (1% sucrose and 0.9% agar, pH 5.7) supplemented with kanamycin (50 mg/L). After 2 d at 4°C, the seeds were grown under 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycles at 22°C. The kanamycin phenotype (resistant or sensitive) was scored on plates after 2 weeks.

Analysis of rpn1 Mutants by PCR

DNA of the Arabidopsis T-DNA lines, the SGT4227 transposant, or the progeny of crosses (depending on the experiment) was extracted and screened for the T-DNA or Ds transposon insertions at the RPN1a or RPN1b locus. Forward and reverse primers from the sequences of the RPN1a or RPN1b gene were designed for PCR screening with a combination of T-DNA left and right border-specific (Alonso et al., 2004) or Ds-3′ and Ds-5′ primers (Grossniklaus et al., 1998). PCR fragments were confirmed by sequencing. Sequences of primers used are as follows: for RPN1a-5′, 5′-GTCTTGCAGTTTTGTCTGCGACC-3′, 5′-GAGTTTTCGATAGCACAAGC-3′, and 5′-GATGGCTCCAACTCAGGATCCCAACAGT-3′; for RPN1a-3′, 5′-CTTCAACTCGATCGAGACTCC-3′ and 5′-GGGAACTGAAGTCATGGAACTTGTTGAA-3′; for RPN1b-5′, 5′-CGATCGAATTAGTTGCTTCG-3′ and 5′-GAAGCTACGACGAAGATTCC-3′; for RPN1b-3′, 5′-CAGCTGCCAATCAAACCAGC-3′, 5′-TCAATAGAGGACTCTTCACC-3′, and 5′-GCAGATAGATTTTGCCTAGC-3′. PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, then 34 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 15 s at 53°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 5 min at 72°C.

Reversion of the rpn1 Mutation

Gene trap transposant SGT4227 was crossed with homozygous Ac/Ac lines in order to remobilize the Ds element. Genomic DNA was extracted from both phenotypic and wild-type sectors of a hybrid plant. For analysis of revertant sequences, we used the following primers: PRN1a sequence flanking the rpn1a-1 Ds element and 3′-end sequence of the Ds element (Grossniklaus et al., 1998) (lanes 1, 3, and 5, Figure 2B) and two primers within the Ds element (5′-CTGTTGTGTCATTTGTGTGC-3′ and 5′-CAGCAAGAACGGAATGCGCG-3′) (lanes 2, 4, and 6, Figure 2B). Genomic DNA, extracted from the wild-type sector, was amplified by PCR with the primers RPN1-3′ (5′-GAGTTTTCGATAGCACAAGC-3′) and RPN1-5′ (5′-CTTCAACTCGATCGAGACTCC-3′) designed within the RPN1a gene 5′ and 3′ of the Ds insertion. For sequencing, the PCR fragment of 720 bp was ligated into the pDrive plasmid and subcloned into Escherichia coli (strain DH5α), then isolated, purified, and sequenced on an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) with primers m13-20 and m13-reverse (Qiagen PCR Cloning Handbook).

DNA Gel Blot Analysis

Genomic DNA from individual plants was prepared with the Nucleon Phytopure kit (Amersham Pharmacia Life Sciences) digested by EcoRI, EcoRV, SacI, and SpeI restriction enzymes. DNA gel blot analysis was performed according to the supplier's protocol (Roche Diagnostics) with DIG-labeled 500-bp probe from the hygromycin gene. The number of bands per individual plant obtained by restriction with the different enzymes was consistent.

RNA Extraction and cDNA Preparation

For quantitative RT-PCR experiments, tissues of leaves, stems, floral buds, open flowers, and siliques (2 to 3 mm = silique 1; 4 to 7 mm = silique 2, and mature siliques = silique 3) were frozen in liquid nitrogen and grinded two times for 7 s with autoclaved glass beads in a Silamat S5 mixer (Ivoclar Vivadent). Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the supplier's recommendation. Five micrograms of total RNA were treated with 2 units of RNase-free DNaseI (Amersham Pharmacia Life Sciences) and purified with Phenol:Chloroform (1:1) before ethanol precipitation. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed 1 h at 42°C using 0.5 μg of random primers, 0.25 mM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 5 mM DTT, and 200 units of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), followed by heat inactivation at 72°C for 15 min.

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

The accumulation of RPN1a, RPN1b, and ACTIN1 transcripts was measured using quantitative real-time RT PCR as described by Köhler et al. (2003) with detection using a Sybr Green Assay together with the reference gene 18S rRNA (ABI PDAR) or ACTIN1. One-twenty-fourth of the cDNA preparation was used at a concentration of 384 nM in 26-μL reaction volume. The PCR reaction and quantitative measurements were performed with an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) using standard conditions. Three replicates were performed for each sample. The specificity of the unique amplicon was determined by melting curve analysis according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR products were cloned and sequenced. The primers were designed to span an exon-exon junction to ensure a cDNA-specific amplification. The sequences of the forward and reverse primers are given hereafter, and their cDNA position relative to the start codon is indicated in parentheses: RPN1a, 5′-CACAGATTCGGAAGTTGCCA-3′ (+2094) and 5′-TGGAGAGGTTCCGAAGCATC-3′ (+2194); RPN1b, 5′-CTGACTCAACCAGTGGATCGG-3′ (+1176) and 5′-CTAGTCCGGTCTCCACATCCC-3′ (+1293); ACTIN1, 5′-GAGACTTTCAATGCCCCTGC-3′ (+379) and 5′-CCATCTCCAGAGTCGAGCACA-3′ (+479). Primers were all designed using PrimerExpress software according to the guidelines of Applied Biosystems.

Protein Gel Blot Analysis

Arabidopsis siliques containing globular stage embryos were harvested and homogenized in extraction buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, 15 mM EGTA,150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 1 mM DTT, and complete protease inhibitor mix [Roche Molecular Biochemicals]) using a Silamat S5 mixer (Ivoclar Vivadent) and centrifuged at 20,000g. Protein concentration was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Twenty micrograms of proteins per sample were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). To detect ubiquitin-protein conjugates, we used a commercial rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog no. UG9510; Affinity Research Products), which was used at a dilution of 1:1000. As a loading control, we detected the AtPIP2b plasma membrane protein using an anti-PIP2 antibody, kindly provided by Tony Schaeffer, at a dilution of 1:1000. The immunoreactive proteins were detected using peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) and the SuperSignal West Dura extended duration substrate protein gel blot analysis system (Socochim).

In Situ Hybridization

Fixation and in situ hybridization experiments on Arabidopsis flower buds and siliques were performed as described (Vielle-Calzada et al., 1999). To synthesize the RPN1a (At2g20580) probe, primers 5′-CATTCCTCTGTCGCCAATAC-3′ and 5′-GTCAGGTCATACAAAGATCC-3′ spanning the region from 5910 to 6113 (203 bp) of the RPN1a sequence were used to amplify the appropriate fragment from Arabidopsis cDNA. To amplify the fragment specific for RPN1b (At4g28470), primers 5′-TTGAAGAAAGAGAGAGAGCC-3′ and 5′-GGATTTGGAAACTTATCCAGC-3′ spanning the region from 3108 to 3301 (193 bp) were used. The DNA fragments from both genes were inserted into the plasmid pKS (Stratagene). Sense and antisense digoxygenin-UTP–labeled riboprobes were generated by run-off transcription using T7 and Sp6 RNA polymerases according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Diagnostics). Hybridization was performed on the 10 μm Paraplast Plus (Sigma-Aldrich) sections.

Expression of CyclinB1;1-GUS Fusion Protein in the rpn1a-1 Mutant Background

The rpn1a-1 mutant was crossed with a homozygous line containing a transgene derived from pCDG (Colón-Carmona et al., 1999), where the CycB1;1 promoter plus sequences encoding the first 150 amino acids of CYCB1;1, including a cyclin destruction box, were fused in frame to the uidA gene, encoding GUS. Seeds for this line were kindly provided by John Celenza. F2 seeds were stained for GUS activity as described (Rodrigues-Pousada et al., 1993); after staining, the specimen were cleared following the protocol of Yadegari et al.(1994) and observed under the Leica DMR microscope.

RT-PCR Analysis of Double Mutants

RNA from the lines heterozygous for rpn1a-1 and homozygous for rpn1b-2 or rpn1b-3 was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II RNase H free reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). cDNA from each line was subjected to PCR applying forward and reverse primers designed to span an intron of RPN1a or RPN1b to distinguish cDNA from contaminating genomic DNA. For RPN1a, primers 5′-GATGGCTCCAACTCAGGATCCCAACAGT-3′ and 5′-GGGAACTGAAGTCATGGAACTTGTTGAA-3′ were used. For RPN1b, primers 5′-GAAGCTACGACGAAGATTCC-3′ and 5′-TCAATAGAGGACTCTTCACC-3′ were used.

Complementation of the rpn1a Mutation

For complementation, we used Gateway cloning technology as described elsewhere (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003). We designed three constructs based on the plasmid pMDC32 (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003), where two copies of the 35S promoter were either retained or exchanged by the RPN1a promoter spanning the region from 56072 to 57803 of the BAC F23N11 (1731 bp) using PmeI and AscI restriction sites. RPN1a or RPN1b cDNA was inserted downstream of the selected promoter by recombination cloning. rpn1a/RPN1a heterozygous plants were transformed by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998) using Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Transformed plants were evaluated for their seed abortion phenotype and the number of T-DNA insertions.

Image Processing

All images were processed for publication using Adobe Photoshop 5.5 (Adobe Systems).

Database Searches and Sequence Analysis

DNA sequences were analyzed using a locally installed BLAST server (Altschul et al., 1997) against public and local nucleotide and protein databases. Detailed analysis was performed with the GCG sequence analysis software package version 10.1, the EMBOSS package (Rice et al., 2000), and by dot plot (DOTTER; Sonnhammer and Durbin, 1995). The physical locations of genes in the Arabidopsis genome were determined using the maps available at The Arabidopsis Information Resource (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). Data on Arabidopsis chromosomal duplications were found at http://wolfe.gen.tcd.ie/athal/dup. Information about the expression of RPN1a and RPN1b was found at the UNIGENE website from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/UniGene).

Accession Numbers

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative locus identifiers for the two genes described here are At2g20580 (RPN1a) and At4g28470 (RPN1b).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Arabidopsis Stock Centers in Nottingham and Ohio for providing seeds of insertional mutants, John Celenza (Boston University, Boston, MA) for donating the CycB1;1-GUS line, and Anton Schäffner (GSF Forschungzentrum, Neuherberg, Germany) for providing the anti-PIP2 antibody. We are indebted to Romain Guyot (University of Zürich) for help with bioinformatics, Umut Akinci (University of Zürich) for help with protein gel blots, Michi Federer (University of Zürich) for producing semithin sections, and Mark Curtis (University of Zürich) for help with the design of complementation constructs. V.B. is thankful to the Kredit zur Förderung des akademischen Nachwuchses der Stiefel-Zangger-Stiftung for financial support. This project was supported, in part, by grants to U.G. from the Bundesamt für Bildung und Wissenschaft (BBW 00.0313) as part of the EXOTIC project within Framework V of the European Union, by the Novartis Foundation, and by the University of Zürich.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Ueli Grossniklaus (grossnik@botinst.unizh.ch).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.105.034975.

References

- Alonso, J.M., et al. (2003). Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301, 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D.J. (1997). Gapped BLASTand PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000). Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly, E., and Reed, S.U. (1999). Functional characterization of Rpn3 uncovers a distinct 19S proteasomal subunit requirement for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of cell cycle regulatory proteins in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 6872–6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, G., Barakat, A., Guyot, R., Cooke, R., and Delseny, M. (2000). Extensive duplication and reshuffling in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant Cell 12, 1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, G., Hokamp, K., and Wolfe, K.H. (2003). A recent polyploidy superimposed on older large-scale duplications in the Arabidopsis genome. Genome Res. 13, 137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blilou, I., Frugier, F., Folmer, S., Serralbo, O., Willemsen, V., Wolkenfelt, H., Eloy, N.B., Ferreira, P.C.G., Weisbeek, P., and Scheres, B. (2002). The Arabidopsis HOBBIT gene encodes a CDC27 homolog that links the plant cell cycle to progression of cell differentiation. Genes Dev. 16, 2566–2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capron, A., Serralbo, O., Fulop, K., Frugier, F., Parmentier, Y., Dong, A., Lecureuil, A., Guerche, P., Kondorosi, E., Scheres, B., and Genschik, P. (2003). The Arabidopsis anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome: Molecular and genetic characterization of the APC2 subunit. Plant Cell 15, 2370–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.G., Ullah, H., Young, J.C., Sussman, M.R., and Jones, A.M. (2001). ABP1 is required for organized cell elongation and division in Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 15, 902–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover, A., Orian, A., and Schwartz, A.L. (2000). Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis: Biological regulation via destruction. Bioessays 22, 442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Argobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colón-Carmona, A., You, R., Haimovitch-Gal, T., and Doerner, P. (1999). Spatio-temporal analysis of mitotic activity with a labile cyclin-GUS fusion protein. Plant J. 20, 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criqui, M.C., and Genschik, P. (2002). Mitosis in plants: How far we have come at the molecular level? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M.D., and Grossniklaus, U. (2003). A Gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 133, 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Engler, J., De Vleesschauwer, V., Burssens, S., Celenza, J.L., Inzé, D., van Montagu, M., Engler, G., and Gheysen, G. (1999). Molecular markers and cell cycle inhibitors show the importance of cell cycle progression in nematode-induced galls and syncytia. Plant Cell 11, 793–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doelling, J.H., Yan, N., Kurepa, J., Walker, J., and Vierstra, R.D. (2001). The ubiquitin-specific protease UBP14 is essential for early embryo development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 27, 393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, P.M., Bonetta, D., Tsukaya, H., Dengler, R.E., and Dengler, N.G. (1999). Cell cycling and cell enlargement in developing leaves of Arabidopsis. Dev. Biol. 215, 407–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser, S., Chandler-Militello, D., Mueller, B., Hanna, J., and Finley, D. (2004). Rad23 and Rpn10 serve as alternative ubiquitin receptors for the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26817–26822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser, S., Gali, R.R., Schwickart, M., Larsen, C.N., Leggett, D.S., Muller, B., Feng, M.T., Tubing, F., Dittmar, G.A.G., and Finley, D. (2002). Proteasome subunit Rpn1 binds ubiquitin-like protein domains. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fobert, P.R., Coen, E.S., Murphy, G.J.P., and Doonan, J.H. (1994). Patterns of cell division revealed by transcriptional regulation of genes during the cell cycle in plants. EMBO J. 13, 616–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H., Reis, N., Lee, Y., Glickman, M., and Vierstra, R.D. (2001). Subunit interaction maps for the regulatory particle of the 26S proteasome and COP9 signalosome. EMBO J. 20, 7096–7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girod, P.A., Fu, H.Y., Zryd, J.P., and Vierstra, R.D. (1999). Multiubiquitin chain binding subunit MCB1 (RPN10) of the 26S proteasome is essential for developmental progression in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 11, 1457–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glas, R., Bogyo, M., McMaster, J.S., Gaczynska, M., and Ploegh, H.L. (1998). A proteolytic system that compensates for loss of proteasome function. Nature 392, 618–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman, M.H. (2000). Getting in and out of the proteasome. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus, U., Vielle-Calzada, J.-P., Hoeppner, M.A., and Gagliano, W.B. (1998). Maternal control of embryogenesis by MEDEA, a Polycomb-group gene in Arabidopsis. Science 280, 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, T., Benkova, E., Baurle, I., Kientz, M., and Jürgens, G. (2002). The Arabidopsis BODENLOS gene encodes an auxin response protein inhibiting MONOPTEROS-mediated embryo patterning. Genes Dev. 16, 1610–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, T., Mayer, U., and Jürgens, G. (1999). The auxin-insensitive bodenlos mutation affects primary root formation and apical-basal pattering in Arabidopsis. Development 126, 1387–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, R.Y., Gardner, R.G., and Rine, J. (1996). Role of 26S proteasome and HRD genes in the degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, an integral endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 2029–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardtke, C.S., and Berleth, T. (1998). The Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS encodes a transcription factor mediating embryo axis formation and vascular development. EMBO J. 17, 1405–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, H., and Estelle, M. (2002). Plant development regulation by protein degradation. Science 297, 793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie, L., McGovern, M., Hurwitz, L.R., Pierro, A., Liu, N.Y., Bandyopadhyay, A., and Estelle, M. (2000). The axr6 mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana define a gene involved in auxin response and early development. Development 127, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howden, R., Park, S.K., Moore, J.M., Orme, J., Grossniklaus, U., and Twell, D. (1998). Selection of T-DNA-tagged male and female gametophytic mutants by segregation distortion in Arabidopsis. Genetics 149, 621–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, D.A. (1950). Plant Embryology. (Waltham, MA: Chronica Botanica).

- Köhler, C., Hennig, L., Spillane, C., Pien, S., Gruissem, W., and Grossniklaus, U. (2003). The Polycomb-group protein MEDEA regulates seed development by controlling expression of the MADS-box gene PHERES1. Genes Dev. 17, 1540–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwee, H.S., and Sundaresan, V. (2003). The NOMEGA gene required for female gametophyte development encodes the putative APC6/CDC16 component of the Anaphase Promoting Complex in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 36, 853–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laux, T., and Jürgens, G. (1997). Embryogenesis: A new start in life. Plant Cell 9, 989–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, D.S., Hanna, J., Borodovsky, A., Crosas, B., Schmidt, M., Baker, R.T., Walz, T., Ploegh, H., and Finley, D. (2002). Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol. Cell 10, 495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukowitz, W., Mayer, U., and Jürgens, G. (1996). Cytokinesis in the Arabidopsis embryo involves the syntaxin-related KNOLLE gene product. Cell 84, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, T., Lipford, J.R., Graumann, J., Smith, G.T., and Deshaies, R.J. (2005). Analysis of polyubiquitin conjugates reveals that Rpn10 substrate receptor contributes to the turnover of multiple proteasome substrates. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, D.R., Köhler, C., da Costa-Nunes, J.A., Baroux, C., Moore, J.M., and Grossniklaus, U. (2004). Intrachromosomal excision of a hybrid Ds element induces large genomic deletions in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2969–2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parinov, S., Sevugan, M., Ye, D., Yang, W.C., Kumaran, M., and Sundaresan, V. (1999). Analysis of flanking sequences from dissociation insertion lines: A database for reverse genetics in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11, 2263–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]