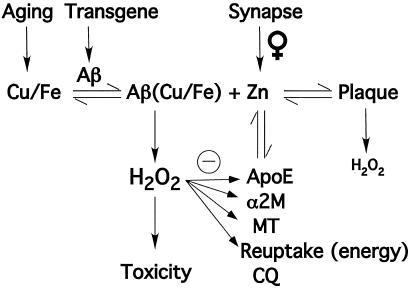

Whereas a decade ago thoughts of metals and Alzheimer's disease (AD) conjured up thoughts of tossing out your aluminum cookware, more recently, zinc, copper, and iron have been implicated in AD pathology. These metals are not derived from your saucepan or deodorant, but are already resident in the brain. Zinc is not a trace metal in the brain. In fact, zinc, copper, and iron concentrations in gray matter are in the same order of magnitude as magnesium (0.1–0.5 mM; refs. 1 and 2) and their participation in major neurological diseases is being increasingly appreciated (3). The argument for exploiting the interaction between β-amyloid (Aβ), and cortical zinc and copper, in designing novel therapies for AD has gathered considerable momentum over the last 5 years. This notion was originally prompted by the finding that the precipitation and redox activity of Aβ are modulated by copper, iron, and zinc (4–11). In this issue of PNAS, Lee et al. (12) report the marked decrease in Aβ deposition in the brains of Tg2576 mice lacking the synaptic ZnT3 zinc transporter. These findings provide in vivo evidence that the characteristic amyloid neuropathology of AD is principally caused by zinc released during neurotransmission. These data will likely have a significant impact on the development of drugs aimed at attenuating β-amyloid pathology underlying AD neurodegeneration (13). The zinc model for AD (Fig. 1) that emerges from these and other findings is more complex than the widely held Aβ autoaggregation model. However, it is also more satisfying because it can explain mysteries such as why Aβ deposits exclusively in the brain, why women more frequently develop Alzheimer's disease, and why rats and mice do not.

Amyloid neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease is principally caused by zinc released during neurotransmission.

Figure 1.

Factors in β-amyloid plaque formation. Plaque exists in a concentration-dependent equilibrium between free Zn2+ and soluble Aβ (which may be bound to Cu2+ or Fe3+). Factors that affect the concentration of Zn2+ are illustrated. Zn2+ is supplied by synaptic activity from the glutamatergic fibers of the corticofugal system, which is amplified in females. The Zn2+ is re-assimilated into the neuron by an energy-dependent reuptake system. Zn2+ may also be sequestered by apolipoprotein E (ApoE), α-2-macroglobulin (α2M), metallothioneins (MT), or by chelating drugs such as clioquinol (CQ). The oxidizing effects of excess H2O2, generated by Aβ, inhibit the ability of several biochemical factors to lower the concentration of free Zn2+. Plaque produces less H2O2 than does Zn2+-free Aβ. Cu and Fe levels rise in senescence. Females undergo increased synaptic release of Zn2+ with age.

AD is the most prevalent of age-dependent neurodegenerative disorders, and the most common cause of dementia, affecting about 10% of people over the age of 60, or over 4 million Americans. With the graying of society, it is becoming increasingly more urgent to find a cure. Current therapeutics aim at enhancing neurotransmitter systems, and do not address the underlying etiology, which remains uncertain. Because Aβ is implicated in the pathogenesis of AD, emerging therapeutic approaches have targeted the inhibition of Aβ production [e.g., protease (secretase) inhibitors that inhibit the generation of Aβ from the amyloid precursor protein, APP], or the enhancement of Aβ clearance (e.g., the Aβ “vaccine”) (14). These approaches simplistically assume that Aβ precipitation in the brain only requires elevated levels of Aβ. However, neurochemical reactions apart from Aβ production also contribute to amyloid deposition in AD. The zinc model can explain why β-amyloid deposits are limited to the neocortex even though Aβ is ubiquitously produced in the brain. At the histological level, the deposits are focal (related to synapses, and the cerebrovascular lamina media), implicating a unique chemical interaction in these microregions that causes Aβ to precipitate. The extracellular concentration of zinc, driven up to 300 μM during synaptic transmission, is likely to be far higher in this space than in any other extracellular compartment in the body (15).

A biochemical link between the metabolisms of APP and zinc was first recognized when APP copurified with a zinc-modulated proteolytic complex in human plasma (16). This then led to the identification of a zinc binding site on the cysteine-rich ectodomain of APP, a feature that is conserved in all members of the APP superfamily (17, 18). Importantly, the highest concentrations of synaptic zinc occur in areas of the neocortex that are most prone to Aβ deposition (19). The seminal discovery in 1992 that Aβ is a soluble component of biological fluids (20) prompted studies aimed at determining whether Zn2+ could influence the solubility and metabolism of Aβ. In 1994, it was reported that Zn2+, at physiologically plausible concentrations, rapidly precipitated soluble Aβ1–40 into protease-resistant, amyloid-like aggregates in vitro (4, 5). The histidine at residue 13 plays a critical role in Zn2+-mediated aggregation (21). Intermolecular His(Nτ)–Zn2+–His(Nτ) bridges form (22) as part of a structure that is strikingly similar to superoxide dismutase 1 (23). In contrast, rat/mouse Aβ1–40 [with substitutions of Arg → Gly, Tyr → Phe, and His → Arg at positions 5, 10, and 13, respectively (24), therefore lacking the bridging histidine] is not precipitated by Zn2+ at physiological concentrations (5), which could explain why mice and rats do not deposit cerebral Aβ amyloid (25).

Although Zn2+ is the only physiologically available metal ion to precipitate Aβ at pH 7.4 (5, 8), Cu2+ (and Fe3+, which has much lower affinity) can induce limited Aβ aggregation, which is exaggerated by slightly acidic conditions (8). Importantly, Aβ generates cytotoxic H2O2 through the reduction of Cu2+ and Fe3+ by using O2 as a substrate (9, 10), perhaps explaining the overwhelming H2O2-mediated damage to the neocortex in AD and in Tg2576 mice (11, 26). Aβ can bind Zn2+ and Cu2+ simultaneously through selective binding sites; however, the affinity for Cu2+ is much greater (attomolar for Aβ1–42) (27). Co-incubation with Zn2+ (which is redox inert) partially inhibits Cu2+-mediated H2O2 production and Aβ toxicity (11, 28). Therefore, the high concentrations of Zn2+ in plaques (≈1 mM; ref. 1) could explain the inverse correlation between oxidation (8-OH guanosine) levels in AD-affected tissue and histological amyloid burden (11). Nevertheless, oxidative adducts are still abnormally elevated even in the AD cases where plaque burden is heaviest (11), indicating that the Zn2+ quenching of H2O2 is not sufficient to abolish damage. In this case, neurodegeneration is likely to be mediated by soluble (possibly Cu or Fe bound) forms of Aβ (29–31) dissociating from the amyloid mass (Fig. 1). Unlike the case in AD, plaque formation in Tg2576 mice positively correlates with oxidative damage in the neocortex (26). However, the deposition of Aβ in the mouse model is far more rapid and abundant than in AD, and antioxidant defenses may not be able to compensate to the same extent as in the human disease.

Zn2+-induced precipitation of synthetic Aβ in vitro is completely reversible with chelation (7, 8) and Zn2+ and Cu2+ removal from AD-affected brain homogenates liberates soluble Aβ (32). Recently, clioquinol (CQ), a retired USP antibiotic and bioavailable Cu/Zn chelator was tested as a potential therapeutic for AD (33). Oral CQ treatment for only 9 weeks achieved marked (49%) inhibition of brain Aβ deposition accompanied by improvement in behavior and general health parameters in Tg2576 mice (33), the same mouse model that Lee et al. (12) studied. CQ also inhibits Cu2+-mediated H2O2 formation by Aβ, which may be another important feature of its pharmacological activity. Most recently, CQ was able to arrest cognitive deterioration and significantly lowered plasma Aβ levels in a recent phase II clinical trial in AD patients.§

Lee et al. (12) also found that the levels of soluble Aβ rise as the levels of total and insoluble Aβ are lowered by the effect of the ZnT3 knockout/Tg2576 cross. This recapitulates the reported effects of clioquinol treatment on Tg2576 mice, where similar changes were observed (33). There was no evidence in the study by Lee et al. (12) or in the clioquinol study (33) that the increase in soluble Aβ was accompanied by any adverse effects, abbreviated lifespan, or synaptic loss. However, it remains to be seen whether the ZnT3 knockout promote oxidation damage in the brains of the Tg2576 mice because the Aβ in these animals is unopposed by zinc in its propensity to bind copper and generate H2O2. Bearing in mind that nontoxic soluble Aβ species are found in normal brain tissue (29, 32), the impression from these two studies is that eradication of aggregated Aβ is beneficial even if soluble Aβ levels rise. It is also possible that the cellular compartment that contains the elevated soluble, apparently toxic, Aβ may be different in AD to the Tg2576 brain.

The affinity of clioquinol for Zn is in the nanomolar range, whereas the affinity of Aβ for Zn2+ is in the low micromolar range. This suggests that even a small shift in the dissociation equilibrium of Zn2+ to Aβ would be sufficient to prevent or reverse the precipitation of the peptide, and that high-affinity chelation is not required of a potential drug. Therefore, precipitation of Aβ by Zn2+ is likely induced by inhibition of the brain's energy-dependent mechanisms for clearing Zn2+ from the synapse (34). However, the findings of Lee et al. (12) indicate that increased amyloid deposition in female Tg2576 mice is due to age-related increases in synaptic zinc (which was ablated by knockout of ZnT3). This finding may also shed light on why women have a higher prevalence of AD (even after correcting for longer lifespan than males). The reason for age-dependent hyperactivity of the ZnT3 transporter leading to excessive release of synaptic Zn2+ (Fig. 1) specifically in females is unclear and will require further study.

Because the concentration of Zn2+ constitutively released by synaptic transmission is sufficient to precipitate Aβ, why do β-amyloid plaques not form all of the time? Indeed, the tonic release of Zn2+ could explain why patients with temporal lobe epilepsy have a high incidence of plaques in the absence of dementia (35), and could also explain the deposition of Aβ after head injury (36). However, in AD, other events probably combine to elevate the ambient concentration of Zn2+ in the extracellular space. Abnormalities of the metallothioneins have been described in AD, and may contribute to pooling of extracellular metals (reviewed in ref. 15). Metallothionein III is specifically found in the ZnT3-positive neurons (37), and is markedly decreased in AD (38). Intriguingly, apolipoprotein E (apoE) and α2-macroglobulin (α2M) are also Cu2+/Zn2+-binding proteins and contain genetic polymorphisms that confer risk for AD. Zn2+ promotes the binding of α2M to Aβ (39), whereas the apoE4 isoform mediates greater Cu2+/Zn2+-induced precipitation of Aβ in vitro than the other two apoE isoforms (40). It is also possible that mitochondrial failure, a stochastic consequence of aging exaggerated by Aβ-mediated H2O2 production, inhibits neuronal Zn2+ recycling and thereby promotes the deposition of Aβ adjacent to sites of highest flux. Increased extracellular Zn2+ and Cu2+ levels might also be the result of oxidative damage to apoE, α2M, and MT-mediated metal ion clearance mechanisms (Fig. 1).

It will be interesting to inspect the APP+ZnT3−/− mice for congophilic angiopathy, which, if absent, would imply that the released synaptic Zn2+ also affects the cerebrovasculature. The contribution of Lee et al. (12) should now shift the research emphasis away from regarding Aβ as an undesirable by-product of APP processing and toward an appreciation of the metallically befouled milieu of the aging brain. Zn2+ is certainly not the sole inorganic factor contributing to Aβ aggregation. Lee et al. show that although the levels of insoluble Aβ, plaque number, and size are markedly attenuated by ZnT3 knockout, the age-dependent precipitation of Aβ is not completely abolished. They hypothesize that nonsynaptic Zn2+, as well as neocortical Cu2+ or Fe3+, could be contributing to Aβ precipitation. A contribution of Cu2+, which is also released during cortical synaptic transmission but at an order of magnitude lower concentration than Zn2+ (41), is very likely because its affinity for Aβ1–42 is extremely strong (attomolar) and non-metal-bound Aβ will not aggregate (27). Cu and Fe levels in the brain rise markedly as mice age (42), and therefore could induce some degree of Aβ precipitation and H2O2 production. Furthermore, sequestration of metals in Aβ aggregates may cause an intracellular deficiency and impairment of essential metal-dependent activities—e.g., a decrease in zinc-dependent carbonic anhydrase activity, which plays an important role in memory function and pH homeostasis in the hippocampus (43).

Lessons learned from the biochemistry of zinc and copper interactions with Aβ in AD may also apply to other neurodegenerative diseases with implications for therapeutics. Metal interactions with proteins implicated in neurodegenerative disorders include superoxide dismutase 1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease, and PrPc in the transmissible spongioform encephalopathies (reviewed in ref. 3). Further genetic manipulation studies of metal homeostasis and transport pathways, such as those of Lee and colleagues, will be very valuable in appraising the contribution of inorganic neurochemistry to the etiology and pathogenesis of these disorders.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 7705.

Masters, C., 7th International Geneva/Springfield Alzheimer's Symposium, April 4, 2002, Geneva, Switzerland.

References

- 1.Lovell M A, Robertson J D, Teesdale W J, Campbell J L, Markesbery W R. J Neurol Sci. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atwood C S, Huang X, Moir R D, Tanzi R E, Bush A I. Metal Ions Biol Syst. 1999;36:309–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bush A I. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:184–191. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bush A I, Pettingell W H, Jr, Paradis M D, Tanzi R E. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12152–12158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush A I, Pettingell W H, Multhaup G, Paradis M D, Vonsattel J P, Gusella J F, Beyreuther K, Masters C L, Tanzi R E. Science. 1994;265:1464–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.8073293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush A I, Moir R D, Rosenkranz K M, Tanzi R E. Science. 1995;268:1921–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.268.5219.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang X, Atwood C S, Moir R D, Hartshorn M A, Vonsattel J-P, Tanzi R E, Bush A I. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26464–26470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atwood C S, Moir R D, Huang X, Bacarra N M E, Scarpa R C, Romano D M, Hartshorn M A, Tanzi R E, Bush A I. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12817–12826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang X, Atwood C S, Hartshorn M A, Multhaup G, Goldstein L E, Scarpa R C, Cuajungco M P, Gray D N, Lim J, Moir R D, et al. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7609–7616. doi: 10.1021/bi990438f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Cuajungco M P, Atwood C S, Hartshorn M A, Tyndall J, Hanson G R, Stokes K C, Leopold M, Multhaup G, Goldstein L E, et al. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37111–37116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuajungco M P, Goldstein L E, Nunomura A, Smith M A, Lim J T, Atwood C S, Huang X, Farrag Y W, Perry G, Bush A I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19439–19442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J-Y, Cole T B, Palmiter R D, Suh S W, Koh J-Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7705–7710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092034699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush A I. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2001;14:341–348. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, Hu K, Huang J, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, et al. Nature (London) 1999;400:173–177. doi: 10.1038/22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frederickson C J, Bush A I. Biometals. 2001;14:353–366. doi: 10.1023/a:1012934207456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bush A I, Whyte S, Thomas L D, Williamson T G, Van Tiggelen C J, Currie J, Small D H, Moir R D, Li Q X, Rumble B, et al. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:57–65. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bush A I, Multhaup G, Moir R D, Williamson T G, Small D H, Rumble B, Pollwein P, Beyreuther K, Masters C L. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16109–16112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bush A I, Pettingell W H, de Paradis M, Tanzi R E, Wasco W. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26618–26621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frederickson C J. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1989;31:145–328. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Esch F, Lee M, Dovey H, Davis D, Sinha S, Schlossmacher M, Whaley J, Swindlehurst C, et al. Nature (London) 1992;359:325–327. doi: 10.1038/359325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S T, Howlett G, Barrow C J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9373–9378. doi: 10.1021/bi990205o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miura T, Suzuki K, Kohata N, Takeuchi H. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7024–7031. doi: 10.1021/bi0002479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtain C, Ali F, Volitakis I, Cherny R, Norton R, Beyreuther K, Barrow C, Masters C, Bush A, Barnham K. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20466–20473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shivers B D, Hilbich C, Multhaup G, Salbaum M, Beyreuther K, Seeburg P H. EMBO J. 1988;7:1365–1370. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaughan D W, Peters A. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1981;40:472–487. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198107000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith M A, Hirai K, Hsiao K, Pappolla M A, Harris P, Siedlak S, Tabaton M, Perry G. J Neurochem. 1998;70:2212–2215. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70052212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atwood C S, Scarpa R C, Huang X, Moir R D, Jones W D, Fairlie D P, Tanzi R E, Bush A I. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1219–1233. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovell M A, Xie C, Markesbery W R. Brain Res. 1999;823:88–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLean C, Cherny R, Fraser F, Fuller S, Smith M, Beyreuther K, Bush A, Masters C. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:860–866. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::aid-ana8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Dickson D W, Trojanowski J Q, Lee V M. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:328–337. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lue L F, Kuo Y M, Roher A E, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, Beach T, Kurth J H, Rydel R E, Rogers J. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cherny R A, Legg J T, McLean C A, Fairlie D, Huang X, Atwood C S, Beyreuther K, Tanzi R E, Masters C L, Bush A I. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23223–23228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cherny R A, Atwood C S, Xilinas M E, Gray D N, Jones W D, McLean C A, Barnham K J, Volitakis I, Fraser F W, Kim Y-S, et al. Neuron. 2001;30:665–676. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howell G A, Welch M G, Frederickson C J. Nature (London) 1984;308:736–738. doi: 10.1038/308736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mackenzie I R, Miller L A. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;87:504–510. doi: 10.1007/BF00294177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts G W, Gentleman S M, Lynch A, Graham D I. Lancet. 1991;338:1422–1423. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92724-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masters B A, Quaife C J, Erickson J C, Kelly E J, Froelick G J, Zambrowicz B P, Brinster R L, Palmiter R D. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5844–5857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-05844.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida Y, Takio K, Titani K, Ihara Y, Tomonaga M. Neuron. 1991;7:337–347. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du Y, Ni B, Glinn M, Dodel R C, Bales K R, Zhang Z, Hyslop P A, Paul S M. J Neurochem. 1997;69:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moir R D, Atwood C S, Romano D M, Laurans M H, Huang X, Bush A I, Smith J D, Tanzi R E. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4595–4603. doi: 10.1021/bi982437d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartter D E, Barnea A. Synapse. 1988;2:412–415. doi: 10.1002/syn.890020408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morita A, Kimura M, Itokawa Y. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1994;42:165–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02785387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun M K, Alkon D L. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)01899-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]