Abstract

To become mature αβ T cells, developing thymocytes must first assemble a T cell receptor (TCR) β chain gene encoding a TCRβ chain that forms a pre-TCR. These cells then need to generate a TCRα chain gene encoding a TCRα chain, which, when paired with the TCRβ chain, forms a selectable αβ TCR. Newly generated VJα rearrangements that do not encode TCRα chains capable of forming selectable αβ TCRs can be excised from the chromosome and replaced with new VJα rearrangements. Such replacement occurs through the process of TCRα chain gene revision whereby a Vα gene segment upstream of the VJα rearrangement is appended to a downstream Jα gene segment. A multistep, gene-targeting approach was used to generate a modified TCRα locus (TCRαsJ) with a limited capacity to undergo revision of TCRα chain genes. Thymocytes from mice homozygous for the TCRαsJ allele are defective in their ability to generate an αβ TCR. Furthermore, those thymocytes that do generate an αβ TCR have a diminished capacity to be positively selected, and TCRαsJ/sJ mice have significantly reduced numbers of mature αβ T cells. Together, these findings demonstrate that normal T cell development relies on the ability of developing thymocytes to revise their TCRα chain genes.

Keywords: V(D)J recombination, gene rearrangement, T cell repertoire, αβ T cell

The checkpoints imposed on developing T cells mandate that they generate T cell receptor (TCR) α and β chains that form an αβ TCR capable of positive selection (1). TCR α and β chain gene assembly is precisely regulated within the context of normal thymocyte development. TCRβ chain genes are assembled in CD4-/CD8- [double negative (DN)] thymocytes (2-4). Expression of a TCRβ chain, as a pre-TCR, results in signals that promote cellular expansion and developmental stage progression to the CD4+/CD8+ [double positive (DP)] stage of thymocyte development (5). Pre-TCR signals also promote TCRα chain gene assembly and prohibit further TCRβ chain gene assembly through the process of allelic exclusion (5-7). Because allelic exclusion prohibits DP thymocytes from generating new TCRβ chains, these cells must generate TCRα chains that form an αβ TCR capable of positive selection if they are to become mature T cells.

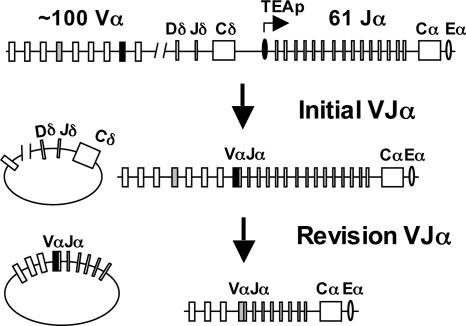

The genes encoding the TCRα chain are intermingled with TCRδ chain genes in the TCRα/δ locus (Fig. 1) (8). TCRα variable region genes are assembled from Vα and Jα gene segments. There are ≈100 Vα gene segments clustered in the 5′ region of the mouse TCRα/δ locus and 61 Jα gene segments, spanning ≈60 kb, clustered in the 3′ region of the locus (Fig. 1) (8). The Vα and Jα gene segments are oriented such that any rearrangement occurs by deletion, excising the intervening DNA from the chromosome (8).

Fig. 1.

Mouse TCRα/δ locus. The Vα, Jα, Dδ, and Jδ gene segments are shown as are the TCRα (Cα) and TCRδ (Cδ) constant region genes. The TEA promoter (TEAp) and TCRα enhancer (Eα) are shown. Examples of initial and revision VJα rearrangements and the circular extrachromosomal reciprocal products from these rearrangements are shown. The TCRα/δ locus is not drawn to scale.

Thymocytes entering the DP compartment from the DN compartment express low TCRβ chain levels, as the pre-TCR, and are referred to as TCRβlow DP thymocytes. Initial Vα rearrangements in these cells are targeted to the most 5′ Jα gene segments through the activity of the T early α (TEA) promoter (9). A nonproductive VJα rearrangement could be followed by a VJα rearrangement on the other allele. Alternatively, a new VJα rearrangement could be generated on the same allele as the nonproductive VJα rearrangement (Fig. 1) (10, 11). This process occurs when an upstream Vα gene segment rearranges to a Jα gene segment downstream of the nonfunctional VJα rearrangement (revision VJα; see Fig. 1). Because all Vα to Jα rearrangements occur by deletion, the nonproductive VJα rearrangement will be excised from the chromosome and replaced by a new, potentially productive VJα rearrangement (Fig. 1).

DP thymocytes that have successfully generated an αβ TCR express higher TCRβ chain levels and are referred to as TCRβint DP thymocytes. TCRβint DP thymocytes continue to undergo Vα to Jα rearrangements until recombinase activating gene (RAG) -1 and -2 expression is terminated by the signals of positive selection (12-18). Thus, a productive VJα rearrangement that does not encode a TCRα chain capable of positive selection could be excised and replaced with a new VJα (Fig. 1) (15, 19-21). Furthermore, in some instances, VJα rearrangements encoding TCRα chains that form autoreactive αβ TCRs could be similarly excised from the chromosome and replaced with a new VJα rearrangement, possibly sparing the developing T cell from death mediated by negative selection (19, 22).

The murine TCRα/δ locus has ≈100 Vα and 61 Jα gene segments. Thus, developing T cells could have many opportunities to excise nonfunctional (nonproductive or productive but nonselectable) VJα rearrangements from the chromosome and replace them with new, potentially functional VJα rearrangements on the same allele. The extent to which normal T cell development relies on this process, hereafter referred to as TCRα gene revision, is not known. We have used a multistep, gene-targeting approach to generate a modified TCRα/δ locus (TCRαsJ) with a single functional Jα gene segment. By analyzing TCRαsJ/sJ mice, we demonstrate that TCRα gene revision is required for thymocytes to efficiently move through two distinct checkpoints of normal thymocyte development. These findings have important implications for T cell development and for the regulation of TCRα chain gene assembly.

Materials and Methods

Generation of the pTEAp/JαKI-Targeting Construct. A 0.2-kb fragment containing the Jα56 segment was amplified by PCR (5′ primer, 5′-CGCG-GGATCC-TGGCTTCATCAGTTAGATTTC-3′; 3′ primer, 5′-CGCG-CTCGAG-AGGTGACGGCTTATGTTTAAAA-3′). A 2.6-kb PCR fragment containing the TEA promoter, TEA exon, and Jα 61ψ segment was also amplified by PCR (5′ primer, 5′-CGCG-GTCGACGATCTCCTGGGGCCCTACCT-3′; 3′ primer, 5′-CGCG-GGATCCCCTTTGCGTCTCTTGGGACA-3′). The 0.2- and 2.6-kb fragments were subcloned into pBluescript (Stratagene) to generate pTEAp/Jα (Fig. 2). pTEAp/JαKI was assembled by using the pLNTK-targeting vector, the 2.8-kb fragment from pTEAp/Jα, a 3.3-kb 5′ homology arm (nucleotides 81594-84851; accession no. M64239), and a 1-kb 3′ homology arm (nucleotides 84851-85800; accession no. M64239), as shown in Fig. 2 (23).

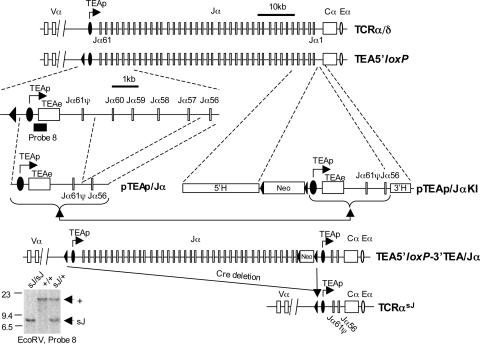

Fig. 2.

The TCRαsJ allele. Shown is the generation of the pTEAp/JαKI-targeting construct and schematics of the targeted alleles as discussed in the text and Materials and Methods. The 5′ homology arm (5′H), 3′ homology arm (3′H), neomycin-resistant gene (Neo) and loxP sites (filled triangles), TEA promoter (TEAp), TEA exon (TEAe), and the position of probe 8 (filled rectangle) are shown. A Southern blot of EcoRV-digested genomic DNA from TCRαsJ/sJ, TCRαsJ/+, and TCRα+/+ mice by using probe 8 is also shown.

Southern and Northern Blot Analyses. Southern and Northern blot analyses were performed as described (24). Appropriate generation of the TEA5′loxP-3′TEA/Jα allele was confirmed by Southern blot analysis of HindIII-digested genomic DNA by using a 0.6-kb ApaI fragment containing the Jα6 gene segment as a 5′ probe (the 8.5-kb wild-type allele vs. the 8.9-kb targeted allele). Appropriate targeting at the 3′ end was confirmed by Southern blot analysis of SpeI-digested genomic DNA (the 6.5-kb wild-type allele vs. the 3.5-kb targeted allele) by using a 0.4-kb probe generated by PCR (5′ primer, 5′-CGCGCTCGAG-TGACTTGTGCCTGTCCCTAA-3′; 3′ primer, 5′-CGCG-GGTACC-TGGCGTTGGTCTCTTTGAAG-3′). After Cre-mediated deletion, the TCRαsJ allele was identified by Southern blot analysis of EcoRV-digested genomic DNA hybridized with probe 7, which has been described (the 14.5-kb TEA5′loxP-3′TEA/Jα allele vs. the 7.1-kb TCRαsJ allele) (25). The RAG-1 probe is a 1.3-kb EcoRI cDNA fragment. Probe 8 (TEA probe), the Cα probe, and the GAPDH probe have been described (24).

Flow Cytometry. Flow cytometric analyses were performed as described (19) by using phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD4 and anti-TCRβ, CyChrome-conjugated anti-CD4, phycoerythrin-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD4, allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD8, and FITC-conjugated anti-Vα2, -Vα3.2, -Vα8.3, -Vα11, and -CD8 (Pharmingen).

BrdUrd Labeling. Mice were injected i.p. with either two doses of 1.5 mg of BrdUrd (Sigma) separated by 1 h during single-pulse experiments or 1.5 mg of BrdUrd every 12 h for the indicated number of days during continuous labeling experiments. BrdUrd incorporation in thymocytes was assayed by flow cytometry by using a BrdUrd FITC-flow kit (Pharmingen).

Results

Generation of the TCRαsJ Allele. We used a previously described (26) embryonic stem cell line that has a single loxP site targeted 5′ of the TEA promoter (see Fig. 2; TEA5′loxP). A 2.6-kb fragment immediately downstream of this loxP site that contains the TEA promoter, TEA exon, and Jα61 gene segment was appended to a 0.2-kb fragment containing the Jα56 gene segment and its flanking recombination signal sequence to generate pTEAp/Jα (Fig. 2). The pTEAp/JαKI-targeting vector was used to target the TEAp/Jα cassette and the loxP-flanked neomycin resistance gene downstream of the Jα1 gene segment on the TEA5′loxP allele generating the TEA5′loxP-3′TEA/Jα allele (Fig. 2). Expression of the Cre recombinase in these embryonic stem cells led to a 66-kb deletion between the loxP sites 5′ of the TEA promoter and 3′ of the neomycin resistance gene generating the TCRαsJ allele (Fig. 2).

The TCRαsJ allele differs from the wild-type TCRα/δ locus in that the 64-kb Jα gene segment cluster, containing 61 Jα gene segments, has been replaced by a 0.5-kb fragment containing two Jα gene segments (Jα61 and Jα56). The regions immediately 3′ and 5′ of the Jα gene segment cluster, including the TEA promoter, are unaltered on the TCRαsJ allele. The Jα61 gene segment was included because many of initial Vα rearrangements occur to the Jα61 gene segment (25). However, the Jα61 gene segment is a pseudogene with two translation termination codons in the correct reading frame. Therefore, on the TCRαsJ allele, only the Jα56 gene segment can give rise to a functional VJα rearrangement. It is important to note that comparison of TCRα cDNAs isolated from wild-type DP thymocytes and mature αβ T cells revealed similar fractions that use the Jα56 gene segment (data not shown). Thus, there is not a significant selection bias for or against TCRα chains encoded by genes that include the Jα56 gene segment. Chimeric mice were generated from TCRαsJ/+ embryonic stem cells, and germ-line transmission of the TCRαsJ allele was achieved.

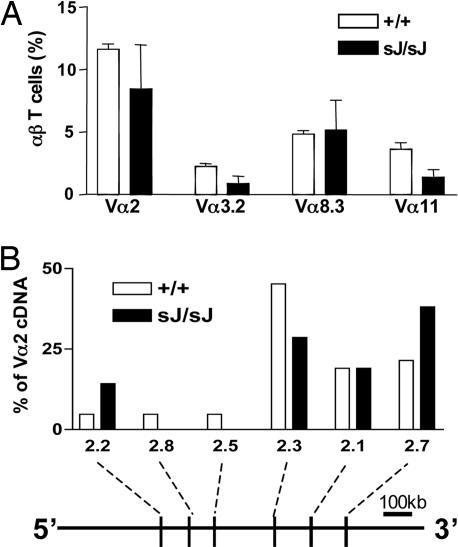

TCRαsJ/sJ Mice Have Increased Thymocytes but Reduced Mature αβ T Cells Numbers. TCRαsJ/sJ mice have increased total thymocyte numbers compared with wild-type TCRα+/+ mice (Fig. 3A). Flow cytometric analyses primarily revealed an increase in the number of DP thymocytes (Fig. 3 B and C). It is notable that this increase in DP thymocyte numbers is coupled with a reduction in the number of CD4+ and CD8+ SP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice (Fig. 3 B and C). Furthermore, TCRαsJ/sJ mice also have reduced numbers of mature CD4+ and CD8+ splenic αβ T cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, despite an increase in the number of DP thymocytes, TCRαsJ/sJ mice have reduced numbers of mature αβ T cells. This reduction is not caused by a significant bias in Vα gene segment use on the TCRαsJ allele as evidenced by flow cytometric analyses, revealing that the fraction of mature T cells using the Vα2, Vα3.2, Vα8.3, and Vα11 gene segments was similar when comparing wild-type and TCRαsJ/sJ αβ T cells (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the frequency of use of the different Vα2 gene segments scattered throughout the Vα gene segment cluster was not significantly different when comparing TCRα cDNAs derived from wild-type and TCRαsJ/sJ αβ T cells (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

T cell development in TCRαsJ/sJ mice. (A) Total thymocyte numbers in 5-week-old TCRαsJ/sJ (sJ/sJ; n = 4) and wild-type TCRα+/+ (+/+; n = 5) mice (P < 0.05). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of TCRαsJ/sJ and TCRα+/+ thymocytes by using anti-CD4 and anti-CD8. (C) Absolute numbers of CD4+CD8+ DP and CD4+ SP and CD8+ SP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ and TCRα+/+ mice. (D) Absolute numbers of splenic αβ T cells and the number of CD4+ and CD8+ splenic αβ T cells in TCRαsJ/sJ and TCRα+/+ mice.

Fig. 4.

Vα gene segment use in TCRαsJ/sJ mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of Vα2, Vα3.2, Vα8.3, and Vα11 expression by lymph node αβ T cells in TCRα+/+ (+/+; open bar) and TCRαsJ/sJ (sJ/sJ; filled bar) mice. Four mice were included in each group, and the SD is indicated. (B) Use of the Vα 2.2, 2.8, 2.5, 2.3, 2.1, and 2.7 family members in Vα2 cDNAs isolated from TCRα+/+ (open bar; n = 45) and TCRαsJ/sJ (filled bar; n = 21) mice. A schematic with the position of the different Vα2 gene segment family members in the Vα gene segment cluster is shown drawn to scale (21).

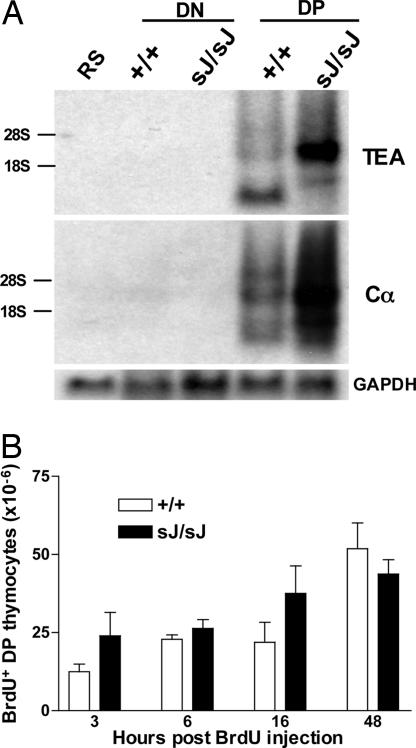

DN to DP Transition Is Not Perturbed in TCRαsJ/sJ Mice. The increased numbers of DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice could be caused by an increase in the generation of these cells from DN thymocytes. Germ-line transcription and rearrangement of TCRα chain gene segments does not occur in DN thymocytes but rather is delayed until the DP stage of thymocyte development (Fig. 5A) (27-31). Likewise, germ-line transcription of the TCRαsJ allele is also delayed until the DP stage of thymocyte development (Fig. 5A). This delay is confirmed by Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from TCRαsJ/sJ·RAG-2-/- DN thymocytes and DP thymocytes from TCRαsJ/sJ·RAG-2-/- mice bearing a TCRβ transgene by using the TEA exon and Cα probes (Fig. 5A). Compared with the wild-type TCRα allele, the germ-line TCRα transcripts templated by the TCRαsJ allele in DP thymocytes have qualitative and quantitative differences (Fig. 5A). These differences are probably caused by TCRαsJ allele modifications that place the TCRα enhancer 63 kb closer to the TEA promoter and remove regions of the Jα gene cluster where lower molecular weight TEA-hybridizing germ-line transcripts normally terminate (32). It is important to note that germ-line TCRα transcripts were not detected in TCRαsJ/sJ·RAG-2-/- DN thymocytes, demonstrating that transcription is not prematurely activated on the TCRαsJ allele in DN thymocytes (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

DN to DP transition in TCRαsJ/sJ mice. (A) Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from RAG-2-/- thymocytes (DN) or RAG-2-/- TCRβ transgenic thymocytes (DP) homozygous for the wild-type TCRα+ (+/+) or TCRαsJ (sJ/sJ) alleles. RNA was probed with probe 8 (TEA), the Cα probe, and the GAPDH probe as an RNA-loading control. RNA isolated from RAG-2-/- splenocytes (RS) was also analyzed as a negative control. The positions of the 28S and 18S RNA are indicated. (B) The number of BrdUrd+ DP thymocytes in individual TCRα+/+ (open bar) and TCRαsJ/sJ (filled bar) mice at 3, 6, 16, and 48 h after BrdUrd injection. Three TCRα+/+ and TCRαsJ/sJ mice were analyzed at each time point.

To directly assess the rate of generation of TCRαsJ/sJ DP thymocytes from DN thymocytes, wild-type and TCRαsJ/sJ mice were pulsed with BrdUrd, and thymocytes were harvested at 3, 6, 16, and 48 h after injection (Fig. 5B). Because BrdUrd incorporation occurs primarily in proliferating DN thymocytes, the rate of accumulation of BrdUrd+ DP thymocytes will be directly related to the rate of transition of DN cells to the DP compartment. These analyses revealed that the kinetics of BrdUrd+ DP thymocyte accumulation was remarkably similar in wild-type and TCRαsJ/sJ mice (Fig. 5B). Thus, the increased numbers of DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice is probably not caused by a significant increase in the generation of these cells from DN thymocytes.

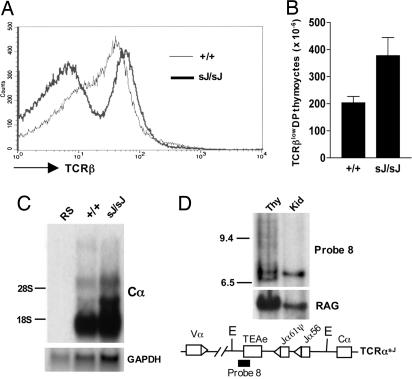

Accumulation of TCRβlow DP Thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ Mice. Flow cytometric analyses revealed that the increase in DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice is primarily caused by an increase in pre-TCR-expressing TCRβlow DP thymocytes (Fig. 6 A and B). Because the kinetics of generation of these cells is not altered (Fig. 5B), this accumulation probably reflects a defect in the ability of TCRαsJ/sJ TCRβlow DP thymocytes to generate an αβ TCR and move to the TCRβint DP stage. Northern blot analyses revealed similar levels of Cα-hybridizing mature TCRα transcripts in wild-type and TCRαsJ/sJ thymocytes (Fig. 6C). Southern blot analyses of EcoRV-digested genomic DNA from TCRαsJ/sJ thymocytes by using the TEA exon probe (probe 8) revealed ≈10% retention of the 7-kb germ-line band and the generation of many nongerm-line size bands caused by the formation of reciprocal products from Vα to Jα rearrangements (Fig. 6D). These findings demonstrate that most of the TCRαsJ alleles in TCRαsJ/sJ thymocytes had undergone a Vα to Jα rearrangement. Moreover, Southern blot and PCR analyses of mature TCRαsJ/+ αβ T cells revealed that essentially all of these cells had undergone a Vα to Jα56 rearrangement on the TCRαsJ allele (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate that TCRαsJ/sJ mice have a diminished capacity to generate αβ TCR-expressing DP thymocytes, which is caused neither by inefficient Vα to Jα rearrangement on the TCRαsJ allele nor by a reduction in the level of mature TCRα transcripts templated by this allele.

Fig. 6.

Accumulation of DP TCRβlow thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of TCRβ chain expression by wild-type TCRα+/+ (+/+; thin line) and TCRαsJ/sJ (sJ/sJ; thick line) DP thymocytes. (B) Number of TCRβlow DP thymocytes in TCRα+/+ (n = 5) and TCRαsJ/sJ (n = 4) mice (P < 0.05). (C) Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from TCRα+/+ (+/+) and TCRαsJ/sJ (sJ/sJ) thymocytes and RAG-2-/- splenocytes (RS) by using Cα and GAPDH probes. (D) Southern blot analysis of EcoRV-digested thymus and kidney DNA from TCRαsJ/sJ mice probed with probe 8 and a RAG-1 probe (RAG) as a DNA-loading control. The positions of 9.4- and 6.5-kb molecular weight markers are indicated. A schematic of the TCRαsJ locus showing the relative position of the EcoRV (E) sites and probe 8 is shown.

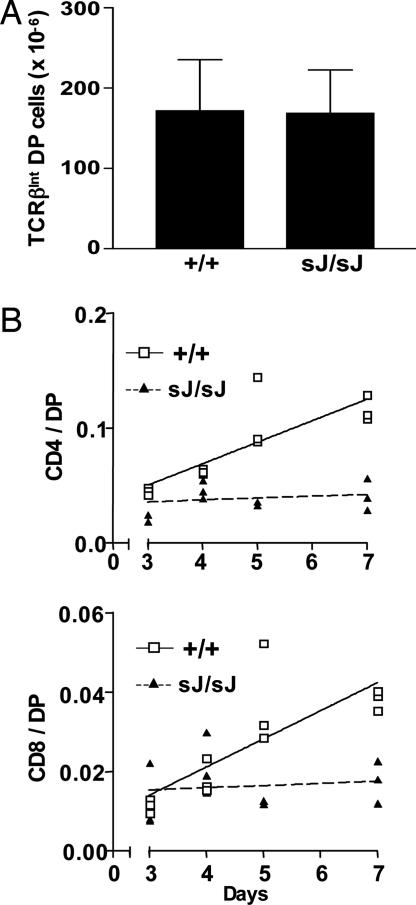

Diminished SP Thymocyte Generation in TCRαsJ/sJ Mice. Paradoxically, the increase in TCRβlow DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice does not lead to a decreased number of TCRβint DP thymocytes in these mice (Fig. 7A). If TCRαsJ/sJ mice had an isolated defect in the TCRβlow DP to TCRβint DP thymocyte transition, they would be expected to have reduced numbers of TCRβint DP thymocytes. However, a concomitant reduction in the efficiency of positive selection could lead to normalization of TCRβint DP numbers in TCRαsJ/sJ mice.

Fig. 7.

Diminished generation of SP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice. (A) The number of TCRβint DP thymocytes in TCRα+/+ (n = 5) and TCRαsJ/sJ (n = 4) mice. (B) The ratio of BrdUrd+ CD4+ to BrdUrd+ DP thymocytes (CD4/DP) (Upper) and BrdUrd+ CD8+ to BrdUrd+ DP thymocytes (CD8/DP) (Lower) was determined for each TCRα+/+ (open square) and TCRαsJ/sJ (filled triangle) mouse analyzed at 3, 4, 5, and 7 days of continuous BrdUrd labeling. Three TCRα+/+ and TCRαsJ/sJ mice were analyzed at each time point. Linear regression analysis was performed on data from analysis of TCRα+/+ (solid line) and TCRαsJ/sJ (dashed line) mice.

To investigate this possibility, TCRαsJ/sJ and TCRα+/+ mice were injected with BrdUrd every 12 h, and the thymocytes were harvested at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 days. Flow cytometric analyses revealed that maximal BrdUrd labeling of DP thymocytes (≈80%) occurred by day 3 in TCRαsJ/sJ and TCRα+/+ mice (data not shown). Therefore, the accumulation of BrdUrd+ SP thymocytes after day 3 should primarily reflect the rate of transition of DP thymocytes into the CD4+ and CD8+ SP compartments. The product (BrdUrd+ CD4+ or CD8+ SP thymocytes) to precursor (BrdUrd+ DP thymocytes) ratio was determined for each of the mice analyzed (Fig. 7B). These analyses revealed a progressive accumulation of BrdUrd+ CD4+ and BrdUrd+ CD8+ SP thymocytes between days 3 and 7 in the wild-type mice (Fig. 7B). In striking contrast, very little accumulation of BrdUrd+ CD4+ and BrdUrd+ CD8+ SP thymocytes was observed in TCRαsJ/sJ mice during the same time interval (Fig. 7B). These data demonstrate that there is a significant reduction in the generation of SP thymocytes from DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice.

Discussion

We have generated and analyzed mice with a modified TCRα locus (TCRαsJ) that has a limited capacity to undergo TCRα gene revision. Although the wild-type TCRα locus has 61 Jα gene segments, the TCRαsJ allele has just two Jα gene segments of which only one, Jα56, is capable of generating a productive VJα rearrangement. The reduction in mature αβ T cells in TCRαsJ/sJ mice demonstrates that T cell development depends on the process of TCRα gene revision. Furthermore, this reduction is caused by the compound effects of a requirement for TCRα gene revision for both efficient generation of αβ TCR-expressing DP thymocytes and the positive selection of these cells into the CD4+ and CD8+ SP thymocyte compartments.

TCRαsJ/sJ mice have an increased number of pre-TCR-expressing (TCRβlow) DP thymocytes (Fig. 6 A and B). This increase is not caused by either an increased generation of these cells from the DN compartment or the proliferative expansion of these cells in the DP compartment (Fig. 5B; data not shown). Furthermore, annexin V staining did not reveal significant differences in the fraction of apoptotic DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ and wild-type mice (data not shown). Thus, the increase in TCRβlow DP thymocytes probably reflects a diminished capacity of pre-TCR-expressing TCRαsJ/sJ DP thymocytes to generate an αβ TCR and move to the TCRβint DP compartment. This diminished capacity could, in part, reflect a requirement for TCRα gene revision to optimize for the generation of a productive TCRα chain gene. In this regard, ≈44% (2/3 × 2/3) of TCRβlow DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice would rearrange both TCRα alleles nonproductively and, thus, would be expected to remain at the TCRβlow stage until death. In contrast, through the process of TCRα gene revision, wild-type DP thymocytes could replace a nonproductive VJα rearrangement with a new, potentially productive (1/3) VJα rearrangement on the same allele.

The accumulation of TCRβlow DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice may also reflect the diminished capacity of these cells to generate a productive VJα rearrangement that encodes a TCRα chain capable of pairing with the specific TCRβ chain (33-35). Thus, TCRα chain gene revision may be important at the TCRβlow to TCRβint DP thymocyte checkpoint to optimize for the generation of a VJα rearrangement that both is productive and encodes a TCRα chain capable of pairing with the TCRβ chain to generate an αβ TCR.

Most randomly generated αβ TCRs are unable to mediate positive selection of DP thymocytes (36-38). The notion that efficient positive selection of DP thymocytes relies on TCRα gene revision is supported by the significant reduction in the generation of CD4+ and CD8+ SP thymocytes from DP thymocytes in TCRαsJ/sJ mice (Figs. 3C and 7B). TCRα gene revision would permit DP thymocytes with a productive but nonselectable VJα rearrangement the opportunity to generate a new VJα rearrangement, which may lead to the generation of an αβ TCR capable of positive selection (20, 21). In addition, TCRα gene revision may rescue DP thymocytes from negative selection by excising and replacing VJα rearrangements that encode the TCRα chains of autoreactive αβ TCRs (19, 22).

Our findings demonstrate that most developing T cells generate more than two complete VJα rearrangements in an attempt to successfully traverse the checkpoints of normal thymocyte development. The maximum number of VJα rearrangements that can be generated through TCRα gene revision in developing T cells is not known but seems limited primarily by the survival parameters of DP thymocytes (39). In this regard, RORγ-/- DP thymocytes, which exhibit diminished survival, seem to undergo a limited number of VJα rearrangements compared with wild-type DP thymocytes or DP thymocytes from BclXL transgenic mice, which exhibit increased survival (39).

The requirement for TCRα gene revision during T cell development is consistent with the notion that many complete TCRα chain genes fail to fully satisfy the requirements imposed by thymocyte developmental checkpoints. Thus, mechanisms may be in place to allow newly generated VJα rearrangements sufficient time to be “tested” to determine whether they encode suitable TCRα chains before the process of TCRα gene revision replaces them with another, likely nonfunctional, VJα rearrangement. Moreover, once a functional VJα rearrangement has been generated, mechanisms must be in place to prevent further Vα to Jα rearrangements on the same allele that would excise the functional VJα rearrangement. In this regard, it is notable that RAG-1/-2 gene expression in DP thymocytes is regulated by a cohort of cis-acting elements that may have evolved, in part, to permit rapid cessation of RAG-1/-2 gene expression and Vα to Jα rearrangement on the positive selection of developing thymocytes (12, 18, 40, 41).

The reliance of developing T cells on their ability to generate more than two complete TCRα chain genes stands in marked contrast to the constraints imposed by the development on TCRβ chain gene generation. Two complete VDJβ rearrangements (one to each of the two DJβ gene clusters) can be generated on each TCRβ allele; thus, developing T cells can generate up to four complete VDJβ rearrangements. However, mice with modified TCRβ loci such that developing T cells can generate only a single complete VDJβ rearrangement have no measurable defect in T cell development (42). Perhaps this normal development is because of the requirement that TCRβ chain gene rearrangements need only be productive and encode a TCRβ chain that forms a pre-TCR. In contrast, TCRα chain genes must be productive, must encode a TCRα chain capable of pairing with the TCRβ chain, and must generate an αβ TCR that can be positively selected. The process of TCRα gene revision increases the likelihood that a developing T cell will generate a VJα rearrangement that meets these three criteria. It is tempting to speculate that the requirement for this process may have been a driving force behind the expansion of the Vα and Jα gene segment clusters during evolution.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michel Nussenzweig for helpful discussion and suggestions. This work is supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant AI47829AI47829 (to B.P.S.) and American Cancer Society Grant RSG-05-070-01-LIB (to B.P.S.). C.H. is supported by a postdoctoral training grant from NIH. Mice were raised in a transgenic core facility supported by the Rheumatic Diseases Core Center at Washington University (NIH Grant P30-AR48335) and housed in a facility supported by National Center of Research Resources (NCRR) Grant RR012466.

Author contributions: C.-Y.H., B.P.S., and O.K. designed research; C.-Y.H. performed research; C.-Y.H., B.P.S., and O.K. analyzed data; and C.-Y.H. and B.P.S. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: TCR, T cell receptor; DN, double negative; DP, double positive; TEA, T early α; RAG, recombinase activating gene; SP, single positive.

References

- 1.Goldrath, A. W. & Bevan, M. J. (1999) Nature 402, 255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snodgrass, H. R., Kisielow, P., Kiefer, M., Steinmetz, M. & von Boehmer, H. (1985) Nature 313, 592-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samelson, L. E., Lindsten, T., Fowlkes, B. J., van den Elsen, P., Terhorst, C., Davis, M. M., Germain, R. N. & Schwartz, R. H. (1985) Nature 315, 765-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raulet, D. H., Garman, R. D., Saito, H. & Tonegawa, S. (1985) Nature 314, 103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Boehmer, H. & Fehling, H. J. (1997) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 433-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aifantis, I., Buer, J., von Boehmer, H. & Azogui, O. (1997) Immunity 7, 601-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khor, B. & Sleckman, B. P. (2002) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14, 230-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glusman, G., Rowen, L., Lee, I., Boysen, C., Roach, J. C., Smit, A. F., Wang, K., Koop, B. F. & Hood, L. (2001) Immunity 15, 337-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villey, I., Caillol, D., Selz, F., Ferrier, P. & de Villartay, J. P. (1996) Immunity 5, 331-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marolleau, J. P., Fondell, J. D., Malissen, M., Trucy, J., Barbier, E., Marcu, K. B., Cazenave, P. A. & Primi, D. (1988) Cell 55, 291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okazaki, K. & Sakano, H. (1988) EMBO J. 7, 1669-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yannoutsos, N., Barreto, V., Misulovin, Z., Gazumyan, A., Yu, W., Rajewsky, N., Peixoto, B. R., Eisenreich, T. & Nussenzweig, M. C. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borgulya, P., Kishi, H., Uematsu, Y. & von Boehmer, H. (1992) Cell 69, 529-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kouskoff, V., Vonesch, J. L., Benoist, C. & Mathis, D. (1995) Eur. J. Immunol. 25, 54-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrie, H. T., Livak, F., Schatz, D. G., Strasser, A., Crispe, I. N. & Shortman, K. (1993) J. Exp. Med. 178, 615-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turka, L. A., Schatz, D. G., Oettinger, M. A., Chun, J. J., Gorka, C., Lee, K., McCormack, W. T. & Thompson, C. B. (1991) Science 253, 778-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandle, D., Muller, C., Rulicke, T., Hengartner, H. & Pircher, H. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 9529-9533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yannoutsos, N., Wilson, P., Yu, W., Chen, H. T., Nussenzweig, A., Petrie, H. & Nussenzweig, M. C. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194, 471-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, F., Huang, C. Y. & Kanagawa, O. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11834-11839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buch, T., Rieux-Laucat, F., Forster, I. & Rajewsky, K. (2002) Immunity 16, 707-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, C. & Kanagawa, O. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 2597-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGargill, M. A., Derbinski, J. M. & Hogquist, K. A. (2000) Nat. Immunol. 1, 336-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cogne, M., Lansford, R., Bottaro, A., Zhang, J., Gorman, J., Young, F., Cheng, H. L. & Alt, F. W. (1994) Cell 77, 737-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sleckman, B. P., Bardon, C. G., Ferrini, R., Davidson, L. & Alt, F. W. (1997) Immunity 7, 505-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak, F., Petrie, H. T., Crispe, I. N. & Schatz, D. G. (1995) Immunity 2, 617-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khor, B., Wehrly, T. D. & Sleckman, B. P. (2005) Int. Immunol. 17, 225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearse, M., Wu, L., Egerton, M., Wilson, A., Shortman, K. & Scollay, R. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 1614-1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson, A., Held, W. & MacDonald, H. R. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 179, 1355-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson, A., de Villartay, J. P. & MacDonald, H. R. (1996) Immunity 4, 37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrie, H. T., Livak, F., Burtrum, D. & Mazel, S. (1995) J. Exp. Med. 182, 121-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez-Munain, C., Sleckman, B. P. & Krangel, M. S. (1999) Immunity 10, 723-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Villey, I., Quartier, P., Selz, F. & de Villartay, J. P. (1997) Eur. J. Immunol. 27, 1619-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuida, K., Furutani-Seiki, M., Saito, T., Kishimoto, H., Sano, K. & Tada, T. (1991) Int. Immunol. 3, 75-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Couez, D., Malissen, M., Buferne, M., Schmitt-Verhulst, A. M. & Malissen, B. (1991) Int. Immunol. 3, 719-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malissen, M., Trucy, J., Letourneur, F., Rebai, N., Dunn, D. E., Fitch, F. W., Hood, L. & Malissen, B. (1988) Cell 55, 49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Correia-Neves, M., Waltzinger, C., Mathis, D. & Benoist, C. (2001) Immunity 14, 21-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sant'Angelo, D. B., Lucas, B., Waterbury, P. G., Cohen, B., Brabb, T., Goverman, J., Germain, R. N. & Janeway, C. A., Jr. (1998) Immunity 9, 179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huesmann, M., Scott, B., Kisielow, P. & von Boehmer, H. (1991) Cell 66, 533-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo, J., Hawwari, A., Li, H., Sun, Z., Mahanta, S. K., Littman, D. R., Krangel, M. S. & He, Y. W. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 469-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu, W., Misulovin, Z., Suh, H., Hardy, R. R., Jankovic, M., Yannoutsos, N. & Nussenzweig, M. C. (1999) Science 285, 1080-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monroe, R. J., Chen, F., Ferrini, R., Davidson, L. & Alt, F. W. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 12713-12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bassing, C. H., Alt, F. W., Hughes, M. M., D'Auteuil, M., Wehrly, T. D., Woodman, B. B., Gartner, F., White, J. M., Davidson, L. & Sleckman, B. P. (2000) Nature 405, 583-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]