Abstract

It is now clear that tyrosine kinases represent attractive targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Recent advances in DNA sequencing technology now provide the opportunity to survey mutational changes in cancer in a high-throughput and comprehensive manner. Here we report on the sequence analysis of members of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) gene family in the genomes of glioblastoma brain tumors. Previous studies have identified a number of molecular alterations in glioblastoma, including amplification of the RTK epidermal growth factor receptor. We have identified mutations in two other RTKs: (i) fibroblast growth receptor 1, including the first mutations in the kinase domain in this gene observed in any cancer, and (ii) a frameshift mutation in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α gene. Fibroblast growth receptor 1, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α, and epidermal growth factor receptor are all potential entry points to the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase intracellular signaling pathways already known to be important for neoplasia. Our results demonstrate the utility of applying DNA sequencing technology to systematically assess the coding sequence of genes within cancer genomes.

Keywords: cancer, genome, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α

Protein kinases are key modulators of signal transduction and play essential roles in the regulation of cell cycle, cellular movement, apoptosis, and other processes that are fundamental to the development and progression of cancers (1). Alterations in the genes encoding these proteins, through mutation or altered regulation, such as by gene amplification, have been shown to contribute to tumor formation and, therefore, there is intense interest in this protein family for understanding mechanisms and targets for therapeutic intervention (2). Recent successful development of targeted intervention agents has been based on the use of small molecules and antibodies directed to disregulated tyrosine kinases (2, 3). Therefore, further determining genomic alterations within this gene family and assessing their biological role might provide targets to expand therapeutic interventions for cancer.

A catalog of 518 human protein kinases has been discerned from the human genome sequence (1). Advances in DNA sequencing technology have facilitated rapid resequencing of these genes. The first study to take advantage of both of these advances resequenced 138 genes, including all of the tyrosine kinase and tyrosine-kinase-like genes, in colon cancers, which resulted in the identification of 14 genes with somatic mutations, suggesting potential roles in carcinogenesis (4). Importantly, the results demonstrated the importance of an unbiased and comprehensive approach to mutation analysis because many of these new genes implicated in cancer development may not have been obvious based on our knowledge of their function or placement within a known cancer-related pathway.

Glioblastomas are one of several commonly occurring cancers for which current therapy has little impact on survival. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is amplified in 30-50% of glioblastomas and a potential molecular target, but it is likely that additional targets will be needed to eventually develop effective treatment for the majority of glioblastoma patients. Because the mechanism for rapid trials of novel therapies exist for glioblastoma samples with a high purity of tumor cells were available and because of the dire need for improved treatment, glioblastoma genomes were selected for partial resequencing.

To find molecular targets, we have sequenced the coding exons for the kinase domains of 20 human receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) genes in glioblastomas. We report the identification of somatically derived, nonconserved alterations in two RTKs, fibroblast growth receptor 1 (FGFR1) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA).

Materials and Methods

Samples. A panel of 19 glioblastoma tumors (GBM1-GBM19) all with matching normal genomic DNA samples was assembled (17 from primary tissues, 1 xenograft, and 1 cell line) from the Departments of Neurosurgery and Pathology, Johns Hopkins University. This panel consisted of eight females and 11 males ranging in age from 7 to 77 years of age.

Genetic Identity Testing. The genetic identity of the 19 matching normal and tumor DNAs for GBM1-GBM19 was confirmed by analyzing nine tetranucleotide short tandem repeat loci and the Amelogenin locus using the AmpFLSTR Profile PCR Amplification kit (Applied Biosystems) and 3100 capillary electrophoresis (Applied Biosystems) as per the manufacturer's instructions. One sample (GBM6) showed evidence of microsatellite instability (MSI). The MSI phenotype of GBM6 was determined by analyzing five loci using the assay described by Berg et al. (5). The data were interpreted by following the guidelines set out by Boland et al. (6). GBM6 was classified as MSI-low.

Sequencing Target Identification. Twenty RTKs were selected based on the classification of Manning et al. (1) (Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), and 160 exons encoding the kinase domain and their adjacent region were selected with the Pfam predictions contained within the Ensembl genome browser (www.ensembl.org/Homosapiens). FGFR1 exon structure was defined according to Ensembl annotation NCBI35.

DNA Sequencing and Data Analysis. The bidirectional dideoxy sequencing of 20 receptor kinase domains and their adjacent regions in 19 glioblastomas was performed using the high-throughput sequencing pipeline at the Venter Institute's Joint Technology Center. The detailed methods for primer design, PCR sequencing, and data analysis are available in the Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. All primer sequences are available in Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR. The wild-type EGFR, EGFRvIII mutant, FGFR1, and PDGFRA genes were analyzed for gene amplification using quantitative PCR. Copy number of changes between normal human genomic DNA (BD Biosciences Clontech) and glioblastoma DNA were determined by quantitative PCR on an iCycler (Bio-Rad). The repetitive element Line-1, which has an equivalent number in cancer and normal genomes, was used for normalization of DNA content. PCR conditions and calculations were performed as described in ref. 7 and 8. All PCR reactions were carried out in triplicate, and the threshold cycle numbers were averaged. The primers used to amplify wild-type EGFR, EGFRvIII, and FGFR1 were designed with primer3. The primers sequences are available in Table 2. Primers used to amplify PDGFRA were reported in ref. 9. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technology (Coralville, IA). To ensure the primers were working effectively, we tested the newly designed primers on glioblastomas with known wild-type EGFR amplification (tumor 15), EGFRvIII amplification (tumor 6), and no EGFR amplification (tumor 16) as assessed by Pandita et al. (10).

Mapping of Mutations to the Three-Dimensional Structure of FGFR1. Several FGFR1 structures have been experimentally solved to date, and we selected Protein Data Bank ID 1FGI (11) to determine the location of the mutated residues given the completeness of this particular structure. Protein alterations were identified on the structure by using residue numbers as a reference. To determine the effects of the kinase mutations on the protein structure, comparative homology modeling was performed as described in ref. 12 by using the solved protein structure and testing each amino acid change individually. The quality of the final optimized structures were verified with procheck (13). Furthermore, the distribution of surface charges was evaluated by using grass (14) to calculate numeric values of partial atomic charges and map them to the surface.

Comparative Analysis of FGFR1 Mutant Residues. To determine the conservation of the residues in the mutated region in the kinase domain the four human paralogs were aligned using clustalw (15). We also assessed the statistical significance of the observed mutations and evaluated residue distribution in the kinases related to FGFR1 by using the Protein Kinase Resource (PKR) (16). The PKR hierarchical classification system includes classes (e.g., tyrosine kinases), groups (smaller subclasses with higher internal sequence similarity, such as FGFR or insulin receptor kinases), and families (the lowest level of closely related kinases). To determine the conservation of the mutated residues in the most closely related kinases, we evaluated the residue frequency distribution across the family members (further information is available from the authors upon request). We used two alternative methods to create sequence alignments of the orthologs and paralogs in the FGFR family. First, we constructed a sequence alignment of FGFR1 with related protein kinases, found in the PKR database with blast (17) and clustalw (15). Second, we displayed alignments of the FGFR1 family available from the PKR master sequence alignment. Because both approaches resulted in identical results, we used the alignment provided by the PKR and visualized it in the sequence viewer integrated within the web site. Residue frequency distributions and side chain conservation were calculated for the positions of the mutations at the family level. We also evaluated the residue frequency distribution in the more distantly related members of the FGFR1 “group” as described above.

Results and Discussion

Sequencing of the Catalytic Domains of 20 RTK Genes. Sequences of the 161 exons encoding the 20 kinase domains of the RTK genes listed in Table 1 were determined by bidirectional dideoxy sequencing, and potential mutations were identified by comparing the tumor sequence to the National Center for Biotechnology Information reference human genome sequence. The protein-altering changes in the tumor DNA were investigated further by sequencing the corresponding normal DNA. From this analysis, we identified mutations in the FGFR1 and PDGFRA genes.

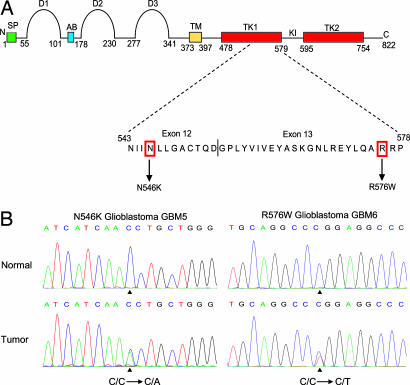

Somatic Mutations in the Kinase Domain of FGFR1. Analysis of the FGFR1 genes identified two somatic mutations encoding alterations in the kinase domain in glioblastomas. These mutations were N546K and R576W in GBM5 and GBM6, respectively (Fig. 1). Further sequencing of the entire FGFR1 coding region in the 19 glioblastomas, including the exon/intron boundaries, did not identify additional mutations.

Fig. 1.

FGFR1 mutations in glioblastoma. (A) Schematic representation of the domain structure of FGFR1 showing the location of mutation we identified in this study. The numbers indicate the amino acid residue number at the approximate boundaries of each domain as described by Webster and Donoghue (26). The N and C termini are labeled N and C, respectively. The peptide regions showing locations of the mutations are shown below the domain structure, and the mutated residues are indicated in the amino acid sequence. SP, signal peptide; D1-D3, Ig-like domains; AB, acid box; TM, transmembrane domain; TK1 and TK2, tyrosine kinase domains; KI, kinase insert region. (B) Sequence data showing the two somatic DNA sequence alterations (indicated by vertical arrows); these are (from left to right) N546K (C/C→C/A) and R576W (C/C→C/T), which are located within the kinase domain in glioblastomas.

Specific mutations located within the kinase domain of FGFR1 have previously been reported but are not associated with cancer (reviewed in ref. 18). Two FGFR1 mutations located outside the kinase domain have been described in cancer: A429S in colorectal cancer (4) and S125L in breast cancer (19). Amplification and overexpression of FGFR1 has also been identified in a range of cancers, including overexpression in astrocytomas, and amplification in breast and ovarian tumors (ref. 11 and references therein). By using quantitative PCR, we determined that none of the 19 glioblastomas showed genomic amplification at the FGFR1 locus.

Interestingly, FGFR1 and EGFR stimulate a similar repertoire of intracellular signaling pathways. EGFR has been reported to be amplified in 30-50% of glioblastomas (20). Many patients with EGFR amplification concurrently show gene rearrangements and other mutations. The most frequent gene rearrangement is an in-frame deletion of amino acid residues 6-273, which results in the EGFRvIII mutant (21). To investigate whether the samples with FGFR1 mutations also have EGFR amplifications, we performed quantitative PCR. Three of 19 glioblastomas had EGFR amplification and no EGFRvIII deletion mutations were detected. Although the samples with FGFR1 mutations, GBM5 and GBM6, did not overlap with the three samples with EGFR amplification, the small sample size prevents us from suggesting that the events are mutually exclusive.

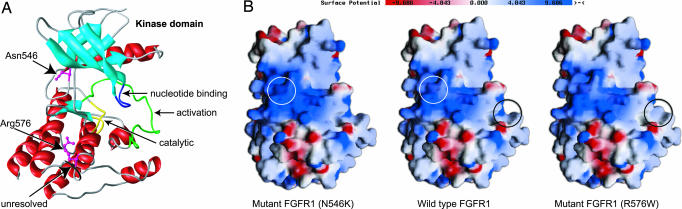

Structural Analysis of the FGFR1 Mutant Residues. To understand the effects of the two mutations within the kinase domain of FGFR1, we analyzed the side-chain composition at the mutated residues in the context of the protein structure. Fig. 2A shows the location of the mutated residues in the wild-type kinase domain of FGFR1. Comparative homology modeling does not predict that the N546K and R576W changes in the FGFR1 protein result in significant modifications in the tertiary structure (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Consequence of mutations on the structure of FGFR1 kinase domain. Structure predictions show effects of FGFR1 kinase mutations on protein properties. (A) A three-dimensional structure of the kinase domain of the human wild-type FGFR1 showing the locations of mutations and functional regions. The residues in the wild-type protein are shown in a ball and stick representation colored in magenta. The other domains are colored accordingly: α-helices, red; β-sheets, light blue; catalytic domain, yellow; activation loop, green; nucleotide-binding loop, dark blue; 14-aa unresolved portion of crystal structure bearing the tyrosine residues (Y583 and Y585), black. The locations of somatic mutations at positions 546 and 576 are indicated. (B) Distribution of surface charges in the human wild-type and mutant FGFR1. The color scale for surface potential is shown. Red color denotes acidic properties of the surface (negative charge), and blue corresponds to basic surface (positive charge). The regions affected by the mutations are circled in white and black on the wild-type FGFR1 and in the corresponding color in the affected region on the relevant mutant FGFR1.

Comparison of the structures of wild-type FGFR1 and the two mutants did reveal changes in the surface charges (Fig. 2B). There is a dramatic reduction in the positive charge/basic properties on the surface of the R576W mutant in the region affected by this mutation. Tryptophan is a nonpolar amino acid; therefore, the mutation of residue 576 from a positively charged arginine renders the local protein surface more hydrophobic. This increased hydrophobicity in the region of amino acid 576 might enhance protein-protein interactions, given the need to shield from solvent interactions, and therefore increase the likelihood of autophosphorylation events on the adjacent tyrosine residues Y583 and Y585. These residues are located in the unresolved part of the protein. Mohammadi et al. (22) have reported the detection of autophosphorylation events involving these residues. The sum total effects of these changes could mean an up-regulation of kinase activity, potentially in a constitutive manner. The region affected by the N546K mutation is predicted to become more basic. Furthermore, the hydrogen bonding of the N546 side chain to the H541 main chain that is observed in the native FGFR1 structure would be absent in the N546K mutation.

Germline Mutations at Paralogous Positions in FGFR2 and FGFR3. FGFR1 is one of four FGFR transmembrane proteins in the human genome. FGFR1-FGFR4 all have a similar sequence, exon/intron organization, and domain structure. We aligned the four FGFR protein sequences to determine the conservation of the residues of the FGFR1 mutated region in FGFR2-FGFR4. This comparison revealed that the FGFR1 mutated residues are absolutely conserved between the paralogs (Fig. 3A). Intriguingly, mutations have previously been reported in FGFR2 and FGFR3 at the equivalent paralogous position to residue 546 of FGFR1. These mutations actually occur within a stretch of nine amino acids that are absolutely conserved among all four FGFR paralogs.

Fig. 3.

Evolutionary conservation of FGFR at the mutated residues in the kinase domain. (A) Sequence alignment of the region containing mutations within the kinase domains of human paralogs FGFR1-FGFR4. The mutated residues in FGFR1 are indicated with an arrow, and the residue number is given. The corresponding residues in FGFR2-FGFR4 are boxed in blue along with the residue on FGFR1. Sequence identities of aligned proteins to FGFR1 are shown with a hyphen. (B) Residue distribution within the FGFR1 family at positions 546 and 576. The height of each bar is proportional to the total number of kinases with the corresponding residue at this position in the alignment. The color of the fragments within each bar denotes the organism from which kinases with the given residue have originated. The residues at positions 546 and 576 in the wild-type FGFR1 are indicated with a black arrow, and the residue in the mutant FGFR1 is indicated with a red arrow.

Mutations at the mutation hotspot, residue 540 in FGFR3, the paralogous position to 546 in FGFR1, have been associated with hypochondroplasia (HCH), a form of dwarfism (18, 23). The mutation N540K accounts for the great majority of patients with HCH, in whom a mutation has been found (24). The mutated residue 540 in FGFR3 is located in the proximal kinase domain (tyrosine kinase 1) within the ATP-binding domain and confers weak constitutive activation. Biochemical studies have shown that the mutation of the N540 residue to lysine in HCH results in weak ligand-independent autophosphorylation of an immature receptor protein (25). The crystal structure of FGFR1 suggests that the side chain of N546 is hydrogen-bonded to the main chain of H541 (22). Therefore, if the N546K substitution is gain-of-function, it would suggest that the N546 interactions observed in the FGFR1 crystal structure are inhibitory, and disruption of this bond has been predicted to stabilize the active conformation of the receptor (22, 26).

Other mutations of the same residue in FGFR3 to different amino acid residues have also been associated with HCH; these mutations are N540T (27) and N540S (28). Furthermore, mutation of the N549 residue in FGFR2 to a histidine (29) or threonine (18) also occurs at the paralogous position to the mutation N546K we identified in FGFR1. These mutations are associated with the craniosynostosis syndromes Crouzon syndrome and Pfeiffer syndrome, respectively.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of the FGFR1 Mutant Residues. The N546K and R576W mutations encode the replacement of highly conserved residues with side chains atypical for this kinase family. For position 546, asparagine is observed in 75% of the family sequences, whereas lysine is seen in only 6%. In position 576, arginine is found in 78% of the wild-type sequences, whereas none contain tryptophan, which contains a hydrophobic side chain (Fig. 3B). Hence, the mutations have introduced residues that are dramatically different from those found in the wild-type members of the FGFR family. In addition, we did not find a substantial difference between residue distributions between the family and group levels. In the larger group the content of lysine at position 546 was 8%, and arginine was found in 78% of the wild-type sequences at position 576, and none contained tryptophan. These findings suggest that the positions in question are generally conserved within the large group of FGFR kinases, thus participating in contacts or structural networks that are characteristic of the general kinase structures rather than individual families with distinct binding partners.

FGFR1 and Cancer. The discovery of acquired FGFR1 point mutations in glioblastoma supports previous studies linking FGFR1 and the fibroblast growth factor pathway to glioblastomas. For example, functional inhibition of fibroblast growth factor with a neutralizing antibody inhibits a malignant phenotype in glioblastoma cell lines (30). The expression of the FGFR1 receptor and, in particular, an alternative splice form, FGFR1-β, is higher in glioblastoma compared with normal white matter (31). Also, antisense inhibition of FGFR1 reduces glioblastoma cell line growth (32).

FGFR1 has been implicated in several other cancers (33). For example, the translocation (8, 13) found in some leukemia and lymphomas fuses the zinc-finger domains of ZNF-198 to the tyrosine kinase domain of FGFR1 (34). FGFR1 is also overexpressed and possibly implicated in colorectal tumors (35); however, there was only one FGFR1 somatic mutation found in a screen of 182 colorectal cancers (4), suggesting that, although the pathway may be important, the receptor is infrequently mutated in colon cancers.

Discovery of a 2-bp Deletion in the C Terminus of PDGFRA That Results in a Mutant Truncated Protein. Our study is a systematic survey of the mutations of the kinase domain and the surrounding intragenic regions of PDGFRA in glioblastomas. We identified a 2-bp deletion in exon 23 (the final exon) within the C terminus in one of 19 glioblastoma tumors sequenced (Fig. 4). The 2-bp deletion occurs within the codon encoding the serine residue at position 1048. Deletion of two of the three nucleotides in the serine codon results in a frameshift that changes the serine to cysteine. Consequently, the amino acid residues from position 1049 to the last residue at position 1089 are replaced by a single histidine, resulting in an alternate, shorter C terminus. The structural function of the C-terminal tail of PDGFRA is poorly understood. It is known that the C-terminal region from residue 977 to 1024 of PDGFRA is required for ligand-dependent focus formation (36). The tyrosine residues 988 and 1018 within this domain constitute the major binding site for phospholipase Cγ (36). The function of the deleted region 1049-1089 is unknown. With this additional potential mutation found in PDGFRA, the case is building for PDGFRA involvement in glioblastoma. There is one other mutation reported in glioblastoma: a 2,100-bp genomic deletion. This deletion results in an in-frame deletion of 81 aa in the extracellular domain in PDGFRA (37) and has subsequently been shown to be oncogenic (38). PDGFRA is also implicated in glioblastomas by the reports of a few cases of glioblastoma in which the PDGFRA gene is amplified (37, 39-42), leading to receptor overexpression. High levels of PDGFRA expression, possibly independent of genomic amplification, are found in tumors without EGFR gene amplification (43). We determined that the sample (GBM17) containing the partial PDGFRA deletion does not have PDGFRA or EGFR amplification. It has been shown that the growth of certain human glioma cells in vitro (44) and in vivo (45) can be blocked by platelet-derived growth factor antagonists.

Fig. 4.

Models of the wild-type (Upper) and mutant (Lower) PDGFRA to demonstrate the effects of a 2-bp deletion. Both forms of PDGFRA have five extracellular Ig domains (Ig-like domains), a transmembrane domain (TM), a juxtamembrane domain (JM), and a bipartite tyrosine kinase catalytic domain (TK1 and TK2) separated by a kinase insert region (KI) and a C-terminal tail (CT). The N-terminal is labeled N. We identified a 2-bp deletion (AG shown in red text) within the codon encoding a serine residue. The deletion occurs at position 1048 in the final exon (exon 23) of the C-terminal tail. This deletion results in a 2-bp frameshift that introduces two alternative amino acid residues (CH underlined) and a premature STOP codon (indicated by *). The wild-type PDGFRA encodes a 1,089-residue protein, whereas our mutant PDGFRA encodes a 1,049-residue protein.

PDGFRA and Cancer. PDGFRA has been implicated in other cancers. A translocation involving the BCR and PDGFRA genes has been described in BCR-ABL-negative chronic myelogenous leukemia and is predicted to result in dimerization and kinase activation of the fusion protein (46). Activating mutations of PDGFRA are oncogenic events in a subset of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) that has a wild-type KIT gene (47). Corless et al. (48) studied the PDGFRA mutation frequencies and spectrums in 1,105 GISTs. They found that ≈7% GIST have PDGFRA mutation. These mutations were found in exon 18 (82.5%), exon 12 (13.7%), and exon 14 (3.7%). They also found that one-third of GISTs with the specific PDGFRA mutations may respond to Gleevec. It will be important to determine whether PDGFRA mutations play a role in other human malignancies. Such tumors could be sensitive to Gleevec and other small-molecule drugs that inhibit PDGFRA kinase activity. The growing number of PDGFRA genomic alterations reported for glioblastoma suggests that a subset of these tumors might be responsive to PDGFRA kinase inhibitors.

Systematic Genomics and Cancer Target Discovery. Advances in genomic information and technology have set the stage for a new era of discovery based on genomic knowledge of pathways and networks and perhaps a complete catalog of molecular alterations that contribute to cancer. In this study, we have focused on genes in the tyrosine kinase family. Interest in this family derives from the key role that they play in signaling between cancer cells and their microenvironment and the remarkable successes that have been seen in human patients based on molecular targeting of this family. Importantly, although our current study focused on the discovery of mutations in glioblastomas, it is very important to strive for comprehensive databases of all genome alterations in all common cancers. For example, the successes with Gleevec (3), Herceptin (49, 50), and Iressa (51) are based on the discovery of very different molecular events, ranging from translocation to gene amplification and mutation, and the response to these inhibitors is correlated better to these events than to histological classification of cancers. The importance of obtaining sequence information and an assessment of mutational status has been highlighted for Iressa, which was initially developed based on the observation of overexpression of the EGFR gene, but for which it is now clear that specific sequence changes can determine tumor response (51).

This study, although covering only a small fraction of the genome, indicates that informative mutations can be found by systematic mutation screening. The genetic lesions that we have identified could each activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and/or mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, in particular when amplification of EGFR is absent. In total, mutations in growth factor receptors and in PIK3CA and PTEN are common in glioblastoma, and it appears that activation of one of these signaling components is sufficient for pathway activation.

To implicate the utility of FGFR1 or the fibroblast growth factor pathway as a target for glioblastoma therapy, further studies are needed. It is not known whether FGFR1 mutations act in a complementary manner to EGFR amplification, although both genes use similar downstream activation events, and we did not observe overlap in the samples effected by genomic alterations in these genes. The mutations found here in the receptor further implicate the pathway and show the receptor can be a direct target, but the frequency of mutations is low. However, targeting the receptor may not be unreasonable because the pathway may also be activated by other means through ligand binding to the receptor. Determining the extent and frequency to which FGFR1 receptor inhibition can alter growth in glioblastomas should be a useful next step.

Although the frequency of FGFR1 mutations in cancer cannot be determined from our analysis, it is interesting that within a relatively small panel of glioblastomas, we have identified two FGFR1 mutations and an alteration in PDGFRA. It will be important to extend this study to a larger glioblastoma panel and to other types of cancer. Moreover, a more extensive analysis of the RTK gene family should reveal features of the biological interfaces within this gene family and within signaling pathways. The larger challenge for cancer genomics is to build a comprehensive database of cancer-causing alterations and to integrate this knowledge with high-throughput functional screens to better predict which molecular targets will yield effective cancer intervention therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bert Vogelstein, Ken Kinzler, and Victor Velculescu (Johns Hopkins University) for helpful advice and Nina M. Haste (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla) and Matthew LaPointe (J. Craig Venter Institute) for help in creating illustrations. This work was supported by funding from the Ludwig Trust, the Children's Cancer Foundation, the Irving J. Sherman Research Professorship (G.J.R.), and the J. Craig Venter Science Foundation.

Author contributions: V.R., J.H., A.J.G.S., J.C.V., G.J.R., and R.L.S. designed research; V.R., J.H., T.S., S.F., O.B., S.L., D.B., K.L., J.B.E., K.M.M., and K.B. performed research; C.E. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; V.R., J.H., T.S., O.B., S.L., A.T., G.J.R., and R.L.S. analyzed data; and V.R., J.H., G.J.R., and R.L.S. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FGFR1, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1; PDGFRA, platelet-derived growth factor-α; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase.

References

- 1.Manning, G., Whyte, D. B., Martinez, R., Hunter, T. & Sudarsanam, S. (2002) Science 298, 1912-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes, N. E. & Lane, H. A. (2005) Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 341-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Druker, B. J. (2004) Adv. Cancer Res. 91, 1-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardelli, A., Parsons, D. W., Silliman, N., Ptak, J., Szabo, S., Saha, S., Markowitz, S., Willson, J. K., Parmigiani, G., Kinzler, K. W., et al. (2003) Science 300, 949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg, K. D., Glaser, C. L., Thompson, R. E., Hamilton, S. R., Griffin, C. A. & Eshleman, J. R. (2000) J. Mol. Diagn. 2, 20-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boland, C. R., Thibodeau, S. N., Hamilton, S. R., Sidransky, D., Eshleman, J. R., Burt, R. W., Meltzer, S. J., Rodriguez-Bigas, M. A., Fodde, R., Ranzani, G. N. & Srivastava, S. (1998) Cancer Res. 58, 5248-5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, T. L., Maierhofer, C., Speicher, M. R., Lengauer, C., Vogelstein, B., Kinzler, K. W. & Velculescu, V. E. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16156-16161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, T. L., Diaz, L. A., Jr., Romans, K., Bardelli, A., Saha, S., Galizia, G., Choti, M., Donehower, R., Parmigiani, G., Shih Ie, M., et al. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 3089-3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Actor, B., Cobbers, J. M., Buschges, R., Wolter, M., Knobbe, C. B., Lichter, P., Reifenberger, G. & Weber, R. G. (2002) Genes Chromosomes Cancer 34, 416-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandita, A., Aldape, K. D., Zadeh, G., Guha, A. & James, C. D. (2004) Genes Chromosomes Cancer 39, 29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohammadi, M., McMahon, G., Sun, L., Tang, C., Hirth, P., Yeh, B. K., Hubbard, S. R. & Schlessinger, J. (1997) Science 276, 955-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sali, A. & Blundell, T. L. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laskowski, R. A., Macarthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nayal, M., Hitz, B. C. & Honig, B. (1999) Protein Sci. 8, 676-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins, D. G., Thompson, J. D. & Gibson, T. J. (1996) Methods Enzymol. 266, 383-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith, C. M., Shindyalov, I. N., Veretnik, S., Gribskov, M., Taylor, S. S., Ten Eyck, L. F. & Bourne, P. E. (1997) Trends Biochem. Sci. 22, 444-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altschul, S. F., Madden, T. L., Schaffer, A. A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W. & Lipman, D. J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkie, A. O. (2005) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 187-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stephens, P., Edkins, S., Davies, H., Greenman, C., Cox, C., Hunter, C., Bignell, G., Teague, J., Smith, R., Stevens, C., et al. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37, 590-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong, A. J., Bigner, S. H., Bigner, D. D., Kinzler, K. W., Hamilton, S. R. & Vogelstein, B. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 6899-6903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugawa, N., Ekstrand, A. J., James, C. D. & Collins, V. P. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 8602-8606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadi, M., Schlessinger, J. & Hubbard, S. R. (1996) Cell 86, 577-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellus, G. A., McIntosh, I., Smith, E. A., Aylsworth, A. S., Kaitila, I., Horton, W. A., Greenhaw, G. A., Hecht, J. T. & Francomano, C. A. (1995) Nat. Genet. 10, 357-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Passos-Bueno, M. R., Wilcox, W. R., Jabs, E. W., Sertie, A. L., Alonso, L. G. & Kitoh, H. (1999) Hum. Mutat. 14, 115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raffioni, S., Zhu, Y. Z., Bradshaw, R. A. & Thompson, L. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 35250-35259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webster, M. K. & Donoghue, D. J. (1997) Trends Genet. 13, 178-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deutz-Terlouw, P. P., Losekoot, M., Aalfs, C. M., Hennekam, R. C. & Bakker, E. (1998) Hum. Mutat. 1, S62-S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mortier, G., Nuytinck, L., Craen, M., Renard, J. P., Leroy, J. G. & de Paepe, A. (2000) J. Med. Genet. 37, 220-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kan, S. H., Elanko, N., Johnson, D., Cornejo-Roldan, L., Cook, J., Reich, E. W., Tomkins, S., Verloes, A., Twigg, S. R., Rannan-Eliya, S., et al. (2002) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 472-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi, J. A., Fukumoto, M., Kozai, Y., Ito, N., Oda, Y., Kikuchi, H. & Hatanaka, M. (1991) FEBS Lett. 288, 65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison, R. S., Yamaguchi, F., Saya, H., Bruner, J. M., Yahanda, A. M., Donehower, L. A. & Berger, M. (1994) J. Neurooncol. 18, 207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada, S. M., Yamaguchi, F., Brown, R., Berger, M. S. & Morrison, R. S. (1999) Glia 28, 66-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eswarakumar, V. P., Lax, I. & Schlessinger, J. (2005) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 139-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao, S., Nalabolu, S. R., Aster, J. C., Ma, J., Abruzzo, L., Jaffe, E. S., Stone, R., Weissman, S. M., Hudson, T. J. & Fletcher, J. A. (1998) Nat. Genet. 18, 84-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jang, J. H. (2005) Oncogene 24, 945-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu, J. C., Li, W., Wang, L. M., Uren, A., Pierce, J. H. & Heidaran, M. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 7033-7036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumabe, T., Sohma, Y., Kayama, T., Yoshimoto, T. & Yamamoto, T. (1992) Oncogene 7, 627-633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke, I. D. & Dirks, P. B. (2003) Oncogene 22, 722-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleming, T. P., Saxena, A., Clark, W. C., Robertson, J. T., Oldfield, E. H., Aaronson, S. A. & Ali, I. U. (1992) Cancer Res. 52, 4550-4553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hermanson, M., Funa, K., Koopmann, J., Maintz, D., Waha, A., Westermark, B., Heldin, C. H., Wiestler, O. D., Louis, D. N., von Deimling, A. & Nister, M. (1996) Cancer Res. 56, 164-171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joensuu, H., Puputti, M., Sihto, H., Tynninen, O. & Nupponen, N. N. (2005) J. Pathol. 207, 224-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki, T., Maruno, M., Wada, K., Kagawa, N., Fujimoto, Y., Hashimoto, N., Izumoto, S. & Yoshimine, T. (2004) Brain Tumor Pathol. 21, 27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heldin, C. H. & Westermark, B. (1999) Physiol. Rev. 79, 1283-1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vassbotn, F. S., Ostman, A., Langeland, N., Holmsen, H., Westermark, B., Heldin, C. H. & Nister, M. (1994) J. Cell Physiol. 158, 381-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shamah, S. M., Stiles, C. D. & Guha, A. (1993) Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 7203-7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baxter, E. J., Hochhaus, A., Bolufer, P., Reiter, A., Fernandez, J. M., Senent, L., Cervera, J., Moscardo, F., Sanz, M. A. & Cross, N. C. (2002) Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1391-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heinrich, M. C., Corless, C. L., Duensing, A., McGreevey, L., Chen, C. J., Joseph, N., Singer, S., Griffith, D. J., Haley, A., Town, A., et al. (2003) Science 299, 708-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corless, C. L., Schroeder, A., Griffith, D., Town, A., McGreevey, L., Harrell, P., Shiraga, S., Bainbridge, T., Morich, J. & Heinrich, M. C. (2005) J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 5357-5364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baselga, J., Gianni, L., Geyer, C., Perez, E. A., Riva, A. & Jackisch, C. (2004) Semin Oncol. 31, 51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sawyers, C. L. (2002) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 111-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobayashi, S., Boggon, T. J., Dayaram, T., Janne, P. A., Kocher, O., Meyerson, M., Johnson, B. E., Eck, M. J., Tenen, D. G. & Halmos, B. (2005) N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 786-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.