Abstract

Purpose

Lung cancer is currently the most common malignant tumor worldwide and one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths, posing a serious threat to human health. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of endogenous non-coding small RNA molecules that regulate gene expression and are involved in various biological processes associated with lung cancer. Understanding the mechanisms of lung carcinogenesis and detecting disease biomarkers may enable early diagnosis of lung cancer.

Methods

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a critical biological process through which tumor cells acquire migratory and invasive capabilities, playing an important role in the progression of lung cancer. miRNAs regulate the EMT process in lung cancer cells by targeting transcription factors such as Snail, Slug, and ZEB1/2, as well as modulating signaling pathways including TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin, thereby enhancing their migratory and invasive abilities.

Results

NSCLC has been comprehensively elucidated in terms of its pathogenesis, and the detection and therapeutic approaches targeting miRNAs for NSCLC have been systematically summarized.

Conclusion

This review examines the impact of miRNAs on tumor invasiveness through the regulation of key factors or signaling pathways, as well as their potential as biomarkers for the early diagnosis of lung cancer. It provides a theoretical foundation for studying the mechanisms of lung cancer metastasis and developing more precise detection and treatment strategies.

Keywords: Lung cancer, miRNA, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, Signaling pathway, Diagnostic marker

Introduction

Lung cancer, the most common malignant tumor in terms of incidence and mortality worldwide, continues to rank first among cancer-related causes of death (Thai et al. 2021). According to epidemiological data from Global Cancer Statistics 2022 (GLOBOCAN 2022), there are approximately 2.5 million new cases of lung cancer worldwide each year, with 1.8 million deaths, and the burden of disease is increasing (Zhou et al. 2024a). 70% of lung cancer patients are already in the locally advanced (stage III) or distant metastasis (stage IV) stages at the time of initial diagnosis (Hendriks et al. 2024; Su et al. 2020). Studies have shown that distant metastasis of lung cancer is closely related to prognosis. A deeper understanding of the mechanisms of lung cancer metastasis is of great significance for improving treatment outcomes (Rybarczyk-Kasiuchnicz et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2024).

EMT has been widely recognized as a key molecular event driving Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) progression and metastasis (Jiang et al. 2020; Menju and Date 2021). It is a highly dynamic cellular process characterized by loss of epithelial cell polarity, disruption of intercellular connections, and acquisition of a mesenchymal phenotype (Manfioletti and Fedele 2023). This process is accompanied by downregulation of E-cadherin expression and upregulation of mesenchymal markers such as vimentin and N-cadherin, ultimately enhancing tumor cell migration, invasion, and drug resistance. Multiple transcription factors, including Snail, Slug, Twist, and ZEB1/2, play key regulatory roles in the EMT process, regulating the expression of related genes and interacting with various signaling pathways to collectively drive the malignant progression of NSCLC (Chen et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2020a; Perumal et al. 2019).

Recent studies have shown that miRNAs play a crucial regulatory role in the regulation of EMT-related signaling pathways (Feng et al. 2022). miRNA is a class of endogenous non-coding small RNA molecules with a length of 18–24 nucleotides. They primarily function by forming base-pairing interactions with the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of target mRNA, thereby inhibiting protein expression at the post-transcriptional level and mediating the process of mRNA translation inhibition or degradation (Otoukesh et al. 2020; Geng et al. 2017). In lung cancer, miRNA clusters closely associated with EMT, most notably the miR-200 family and miR-34a, serve as core nodes in the EMT regulatory network. They primarily inhibit the EMT process by targeting transcription factors such as ZEB1/2 and Snail, thereby limiting the migratory and invasive capabilities of tumor cells (Kim et al. 2019; Sharma et al. 2023). miRNA is highly tissue-specific and stably present in body fluids such as blood and sputum, making it an ideal molecular biomarker for early screening and prognosis assessment of lung cancer (Fazmin et al. 2020; Zinovkin and Sakharov 2024). With the maturation of liquid biopsy technology, its non-invasive and dynamic monitoring advantages have become increasingly evident, opening up broad prospects for precision diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer (Samson and Parvathi 2023; Li et al. 2020).

This review summarizes the regulatory mechanisms of miRNAs in the EMT process of lung cancer and their impact on tumor invasiveness. It evaluates the sensitivity and specificity of miRNAs as early diagnostic biomarkers and assesses the feasibility and efficiency of miRNA-based detection strategies in different experimental systems. A deeper understanding of the miRNA-EMT regulatory network not only helps to reveal the molecular basis of lung cancer metastasis but also lays the theoretical and experimental foundation for developing more efficient and precise early detection systems.

The effect of miRNA on EMT in lung cancer

The function of miRNA in lung cancer

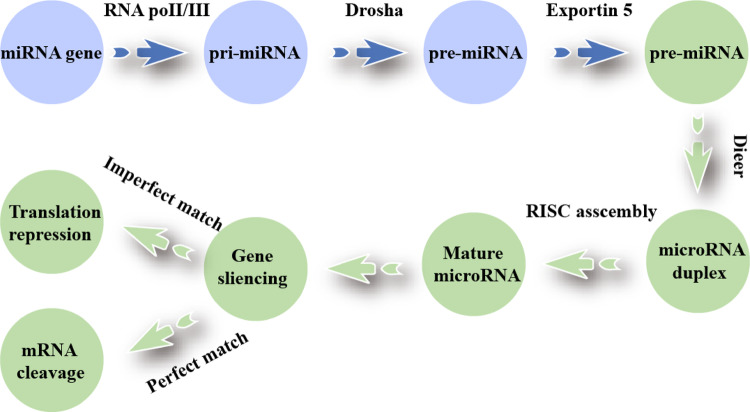

miRNA is an endogenous non-coding RNA of 18–25 nt that can complementarily pair with the 3′-UTR of target mRNA to precisely regulate genes post-transcriptionally (Sarkar and Kumar 2025; Xi et al. 2022). The biosynthesis of miRNAs involves four stages: (1) RNA polymerase II transcribes pri-miRNA; (2) the nuclear DROSHA-DGCR8 microprocessor cleaves pre-miRNA (Gonzalo et al. 2022); (3) Exportin-5/RAN-GTP transports it to the cytoplasm (Nguyen et al. 2015; Rice et al. 2020); (4) DICER recuts, the guide chain is loaded into AGO by HSC70/HSP90, assembles RISC, and inhibits or degrades target mRNA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Biogenesis of miRNA

Research indicates that miRNAs play an important role in the development and progression of tumors (Rac 2024). The miRNA expression profile in tumor tissues is often disrupted. Some miRNAs function as oncogenes (oncomiRs or tumor suppressor genes, tumor suppressor miRNAs) and can regulate tumor cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance (Sadeghi et al. 2023; Khan et al. 2022).

As tumor suppressor genes, miRNAs exert their antitumor effects through the following mechanisms: (1) Inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and survival: miR-330-5p is typically downregulated in NSCLC, and its upregulation can significantly inhibit the proliferation and migration of NSCLC cells, suggesting its potential tumor suppressor function (Cui et al. 2021). (2) Promoting cell apoptosis: Tumor-suppressing miRNAs can increase cell sensitivity to programmed cell death signals by targeting anti-apoptotic genes or upregulating pro-apoptotic genes, thereby inhibiting tumor development (Gasparello et al. 2022). (3) Inhibition of cell migration and invasion: These miRNAs reduce the metastatic potential of cancer cells by downregulating genes related to cytoskeletal remodeling, matrix degradation, or EMT, such as MMPs and vimentin, thereby limiting tumor invasion (Wu et al. 2020a).

Conversely, as oncogenes, miRNAs drive tumor progression through the following mechanisms: (1) Enhancing tumor cell proliferation and migration: Certain miRNAs promote sustained tumor cell growth by activating genes associated with cell cycle progression, signal transduction, or anti-apoptosis. High mobility group A2 (HMGA2) has been identified as an oncogene in NSCLC, and its expression is positively regulated by certain miRNAs (such as miR-21), thereby enhancing the proliferation and invasiveness of NSCLC cells (Gargalionis et al. 2023; Liang et al. 2020). (2) Promoting tumor metastasis: Oncogenic miRNAs can regulate E-cadherin expression, enhance the EMT process, alter intercellular connections and cell–matrix adhesion, thereby improving the migration and invasion capabilities of cancer cells (Wei et al. 2020). (3) Mediating treatment tolerance: Abnormal overexpression of certain miRNAs is closely related to resistance to chemotherapy drugs (such as cisplatin and paclitaxel) or radiotherapy (Fan et al. 2016). miRNA helps cancer cells evade treatment-induced cell death responses and reduce treatment efficacy by targeting genes related to DNA repair, apoptosis inhibition, or drug efflux pumps (Zhu et al. 2021).

Abnormally expressed miRNAs in lung cancer tissues regulate oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, thereby influencing the biological behaviors of lung cancer cells, such as proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis (Morillo-Bernal et al. 2024). microRNA-1246 is downregulated and inhibits the invasion of NSCLC by negatively regulating CXCR4; downregulation of microRNA-218 is associated with poorer prognosis in NSCLC patients. Silencing microRNA-218 promotes NSCLC progression in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting the IL-6 receptor; miR-21 promotes tumor growth by targeting tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN and activating the PI3K/Akt pathway (Li et al. 2017); the miR-34 family exerts its anticancer effects by inhibiting signaling pathways such as Notch and Bcl-2; miR-21 plays a tumor-promoting role in lung cancer. The miR-21-5p/SMAD7 axis promotes the progression of lung cancer (Guo et al. 2021).

There are significant differences in miRNA expression profiles among different types of lung cancer (Wang et al. 2022a). For example, in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), miR-155 and miR-17-92 clusters are often highly expressed, while in squamous cell carcinoma, miR-205 and miR-944 expression levels are higher (Wang et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2020b). These differentially expressed miRNAs not only reflect the heterogeneity of lung cancer but also provide potential targets for molecular subtyping and personalized treatment of lung cancer. Additionally, the expression levels of miRNAs are closely associated with the prognosis of lung cancer patients. High expression of certain miRNAs, such as miR-21 and miR-155, often indicates poor prognosis, while high expression of miR-34a and the let-7 family is associated with better prognosis (Pop-Bica et al. 2020). In NSCLC, the loss of miR-200c expression is associated with promoter methylation, and downregulation of miR-200c expression is associated with poor differentiation, lymph node metastasis, and reduced E-cadherin expression (Si et al. 2017).

The role of EMT in lung cancer

EMT is a key cellular biological process in the occurrence, progression, and distant metastasis of lung cancer (Tan et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023). This process confers mesenchymal-like characteristics on polarized epithelial cells, causing them to detach from their original epithelial structure and acquire enhanced migratory, invasive, and anti-apoptotic capabilities, as well as the ability to synthesize extracellular matrix (ECM) components. This facilitates tumor cells’ penetration of the basement membrane, invasion of surrounding tissues, and formation of distant metastases (Hong and Xing 2024). The EMT process is driven by a series of transcription programs, whose core features include downregulation of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin, Occludin, and Claudins, and upregulation of mesenchymal markers such as N-cadherin, Vimentin, Fibronectin, etc. (Ma et al. 2022; Sari et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2020b). These molecular changes significantly weaken cell–cell adhesion and promote increased cell motility and invasiveness. The induction of EMT is highly regulated by multiple signaling pathways, including TGF-β, Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, PI3K/AKT, etc., which jointly regulate the expression of EMT-related genes by activating transcription factors such as Snail, Slug, ZEB1/2, and Twist (Lee et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2022a; Xu et al. 2023; Bakir et al. 2020).

Cancer cells can acquire stronger migration and invasion capabilities than normal cells by activating the EMT program, which is a key step in tumor cells breaking through the basement membrane, invading the vascular system, and forming distant metastases (Bakir et al. 2020; Lo and Zhang 2018). During EMT, epithelial cells gradually lose their polarity and typical cell–cell adhesion structures, such as tight junctions and adherens junctions (including downregulation of E-cadherin expression), thereby detaching from neighboring cells. This is accompanied by cytoskeletal remodeling, actin filament reorganization, and enhanced motility, ultimately leading to basement membrane disruption and enhanced cell migration capacity (Lee et al. 2019; Azadi et al. 2023).

The EMT process is mainly mediated by a specific class of transcription factors (EMT-TFs), including Snail, Slug, Twist, and ZEB1/2 (Seo et al. 2021). The activation of these transcription factors not only suppresses the expression of epithelial marker genes but also promotes the upregulation of mesenchymal markers (such as N-cadherin and vimentin), thereby driving the conversion of cell phenotypes. In addition, EMT-TFs can promote the collective migration of tumor cells, enhance their adaptability in the tumor microenvironment, and synergistically regulate extracellular matrix degradation and immune escape (Shi et al. 2025). EMT is not limited to promoting metastasis and invasion; its associated transcription factors also have multiple biological functions. Snail and ZEB1 can enhance the stem cell characteristics of cancer cells by regulating stem cell genes (such as SOX2 and OCT4) or enhance immune escape capabilities through interactions with immune inhibitory factors (such as PD-L1), suggesting that EMT has a broad and complex mechanism of action in cancer progression (Gao et al. 2021a; Guo et al. 2025).Stemness acquisition axis: Directly binds to and activates the promoters of stemness genes such as SOX2 and OCT4, maintaining the self-renewal of cancer stem cells (CSCs); relieves post-transcriptional repression of SOX2/OCT4 by inhibiting the miR-200 family, amplifying stemness signals; induces the CD44/CD24 stem cell phenotype, enhancing spheroid formation, drug resistance, and distant metastasis capabilities. Immune escape axis: Snail/ZEB1 forms a positive feedback loop with PD-L1: ZEB1 inhibits miR-200 → relieves miR-200’s inhibition of PD-L1, upregulating PD-L1 expression; Intracellular PD-L1 further activates the TGF-β/Smad and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, which in turn stabilize Snail protein, forming an “EMT-PD-L1” self-amplifying loop; Induction of an immunosuppressive microenvironment: Increases infiltration of M2-type tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), downregulates MHC-I expression, and weakens CD8 + T cell killing.

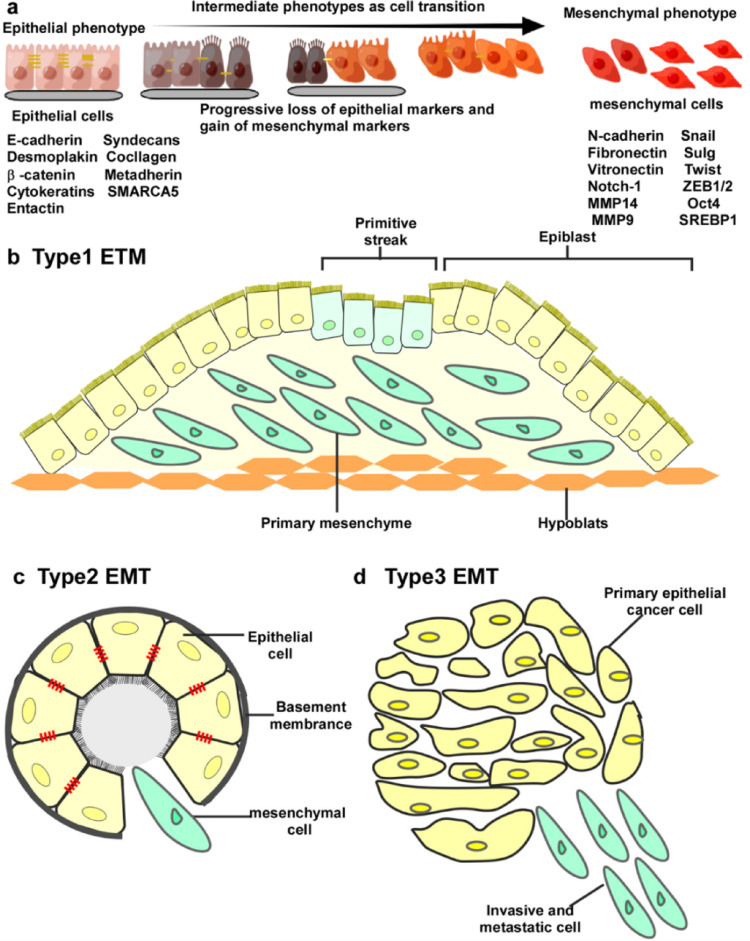

Studies have shown that the expression levels of EMT-related markers are significantly associated with lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, and overall survival in lung cancer patients (Zhu et al. 2024). Downregulation of E-cadherin expression is associated with lung cancer invasiveness and poor prognosis, while high expression of vimentin indicates that tumors have stronger metastatic capacity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

a During the transition from an epithelial phenotype to mesenchymal phenotype, cells lose their intercellular connections and gradually separate from the basement membrane. Four mesenchymal genes, including interstitial N-cadherin and fibronectin, are upregulated, whereas E-cadherin, vitronectin, desmoplakin, and laninmin are downregulated. b Type I EMT c Type II EMT d Type III EMT (Feng et al. 2022)

The relationship between miRNA and EMT

Multiple miRNAs influence the EMT process in lung cancer cells by targeting and regulating EMT-related transcription factors (such as Snail, Slug, ZEB1/2, and Twist) and their downstream effector molecules. For example, the miR-200 family directly inhibits the expression of ZEB1/2, maintaining E-cadherin levels and thereby blocking the EMT process; whereas miR-21 promotes EMT by regulating the PTEN/Akt signaling pathway (Korpal et al. 2008; Fan et al. 2021) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of miRNAs on EMT in lung cancer

| miRNA type | Phenotypic effects | |

|---|---|---|

| miR-200 | Including miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-141, and miR-429, these microRNAs play a central regulatory role in maintaining the epithelial phenotype of cells and inhibiting EMT. This family directly targets key EMT transcription repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2, effectively preventing the downregulation of E-cadherin (CDH1) expression, thereby maintaining tumor cell adhesion and polarity and inhibiting their migration and invasion capabilities. ZEB1/2, as E-box-binding zinc finger proteins, can directly inhibit CDH1 transcription and are one of the most critical transcription regulatory factors in EMT induction. Additionally, the miR-200 family constructs a complex positive and negative feedback regulatory network by targeting other molecules associated with EMT regulation, such as GATA3, miR-132, miR-149, and the forkhead box protein FOXM1. For example, miR-132 and miR-149 can further target ZEB2 and FOXM1, regulating the EMT process at different levels | miR-200a downregulates key cycle/survival signals such as CDK6 and AKT, inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis. miR-200 suppresses the self-renewal capacity of cancer stem cells (CSCs) in NSCLC by inhibiting the ZEB1/2-SOX2/OCT4 axis, reducing spheroid formation and drug resistance potential |

| miR-21 | miR-21 is considered a tumor-promoting miRNA and is highly expressed in various cancers. It promotes EMT by targeting and inhibiting PTEN, TGF-βRII, and other genes that suppress EMT | In NSCLC, high expression of miR-21 is associated with the loss of epithelial characteristics and the acquisition of mesenchymal characteristics, enhancing the invasiveness of tumor cells. High expression of miR-21 is associated with tumor invasiveness, metastasis, and poor prognosis |

| miR-483-3p | miR-483-3p reverses EMT and inhibits migration, invasion, and metastasis of gefitinib-resistant lung cancer cells. Mechanistically, miR-483-3p directly targets integrin β3, thereby inhibiting the downstream FAK/Erk signaling pathway | In NSCLC, low expression of miR-483-3p is associated with downregulation of epithelial markers (E-cadherin) and upregulation of mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin, Snail, ZEB1), significantly promoting the EMT process; this enhances the migration and invasion capabilities of tumor cells and is associated with acquired resistance to gefitinib and shorter overall survival |

| miR-34a | miR-34a is a miRNA that suppresses tumor development by regulating multiple target genes. Studies have shown that miR-34a can inhibit EMT by suppressing the expression of transcription factors such as SNAIL and TWIST | Low expression of miR-34a is associated with enhanced EMT processes and metastatic capacity in NSCLC cells. In NSCLC, miR-34a expression is typically downregulated, and low expression is associated with enhanced EMT processes and metastatic capacity in tumor cells |

| miR-155 | miR-155 plays a promoting role in various tumors by regulating EZH2, TGF-β, and other signaling pathways to promote EMT | In NSCLC, high expression of miR-155 is associated with tumor cell migration and invasion |

| miR-143/145 | miR-143 and miR-145 are considered tumor suppressor miRNAs that exert their inhibitory effects by targeting and regulating EMT-related genes such as SNAIL, ZEB, and TWIST | Low expression of miR-143 and miR-145 is closely related to the EMT process of NSCLC cells, promoting cell migration and invasion capabilities |

| miR589 | The miR589-5p/HDAC5 pathway plays a key role in the migration, invasion, and tumorigenicity of NSCLC cells | In NSCLC, high expression of miR-589 is closely associated with downregulation of epithelial markers and upregulation of mesenchymal markers. By targeting LIFR to activate the PI3K/AKT/c-Jun axis, it drives EMT and significantly enhances tumor cell invasiveness, distant metastasis capacity, and poor prognosis |

| miR-448 | miR-448 promotes tumor progression in NSCLC by targeting SIRT1. Studies have found that downregulation of miR-448 expression upregulates NF-KB signaling pathway activity, leading to EMT and tumorigenesis | In NSCLC, low expression of miR-448 is associated with downregulation of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and upregulation of the mesenchymal marker vimentin, suggesting EMT activation. Restoration of its expression reverses the above phenotypes, significantly inhibits tumor cell migration, invasion, and distant metastasis, and improves patient prognosis |

| miR-205 |

miR-205 directly targets the 3′UTR of ZEB1 and ZEB2, blocking their translation → preventing downregulation of E-cadherin Results: Cells maintain epithelial phenotype, with reduced migration/invasion capacity; when miR-205 is absent, EMT is enhanced |

tumor suppressor/inhibits EMT in LUAD; oncogene/maintains squamous phenotype in LUSC |

| miR-375 | In NSCLC, miR-205 and miR-375 antagonize EMT by “inhibiting the ZEB/AKT-Snail axis”; their expression deficiency leads to E-cadherin loss, increased stromal markers, and subsequently promotes invasion and metastasis and reshapes the immune microenvironment | Both LUAD and SCLC are tumor suppressors/inhibit EMT, but its expression decreases with LUAD progression and increases with SCLC progression |

| miR-1269a | miR-1269a is an oncogenic miRNA that promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by downregulating FOXO1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines (A549 and H1975) | Downregulation of FOXO1 (mediated by oncogenic miR-1269a, miR-421, miR-629, and miR-183) weakens the efficacy of chemotherapy drugs by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, inhibiting apoptosis, and causing cell cycle arrest, thereby promoting chemotherapy resistance. Concurrently, FOXO1 inhibition may enhance tumor invasiveness through EMT-related pathways such as the Wnt/β-catenin pathway(Ebrahimnezhad et al. 2023) |

In lung cancer, miRNAs act as key regulatory factors in the EMT process, participating in the regulation of tumor cell invasiveness and metastatic potential. Studies have shown that miR-34a can inhibit the EMT process by targeting and downregulating the transcription factor Snail1, thereby suppressing the migration and invasiveness of lung adenocarcinoma cells; conversely, miR-155 promotes the EMT process by targeting CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ), thereby enhancing the invasiveness of tumor cells (Siemens et al. 2011; Johansson et al. 2013; Jiang and Lonnerdal 2022). In NSCLC, miR-9 has been found to directly target and inhibit E-cadherin expression, weakening cell–cell adhesion, thereby promoting EMT and enhancing cell migration capacity; miR-30a, on the other hand, inhibits EMT by suppressing the expression of Snail1 and Vimentin, exhibiting significant tumor-suppressing functions.

In addition, miRNAs play a “signaling hub” role in the EMT process: on the one hand, they drive tumor cell phenotype conversion, and on the other hand, they remodel the TME through exosomes, cytokines, and metabolites. Targeting these miRNAs or their downstream pathways can simultaneously attack tumor cells and the immunosuppressive microenvironment, providing a multidimensional strategy for overcoming immune escape and improving the efficacy of immune and targeted therapies. For example, miR-31: EMT-related transcription factor ZEB1↑ → inhibition of miR-31 → release of inhibition on FGF2 → CAFs produce large amounts of ECM proteins, forming a “fibrotic barrier” that hinders drug and immune cell penetration; iR-29 family: downregulated during EMT → release of inhibition on COL1A1, LOX → increased ECM collagen cross-linking → increased tumor hardness, promoting invasion and limiting T cell infiltration; miR-210, miR-21: synergistically upregulate glycolytic rate-limiting enzyme PKM2 → provide ATP and biosynthetic precursors required for EMT cell migration; simultaneously induce tumor-promoting phenotypes in CAFs and TAMs via lactate (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

The role of miRNA and EMT in different signaling pathways

| miRNA regulation | ||

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β signaling pathway | TGF-β is one of the key upstream factors that induce EMT. It promotes the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 and the formation of Smad complexes that translocate into the cell nucleus by activating TGF-β receptors I/II, thereby initiating the expression of key EMT transcription factors such as SNAIL, TWIST, and ZEB |

miR-21: As a pro-EMT factor, it accelerates the EMT process by enhancing TGF-β signal sensitivity miR-34a: It inhibits TGF-β-induced EMT by targeting multiple regulatory factors in the Smad pathway miR-145 and miR-497: negatively regulate EMT by synergistically inhibiting the TGF-β pathway and targeting metadherin (MTDH) in NSCLC Clinical studies indicate that high methylation of the miR-34 and miR-200 promoters is associated with downregulation of their expression, promoting EMT; conversely, their high expression is significantly associated with favorable prognosis miR-138: Effectively inhibits EMT occurrence in NSCLC by targeting GIT1 and SEMA4C miR-483-5p: Targets RhoGDI1, indirectly activating the leukocyte adhesion molecule ALCAM. EMT activation is further observed only in lung adenocarcinoma cells with ALCAM dysfunction, suggesting context-dependent regulation |

| Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | Wnt signaling inhibits β-catenin degradation, leading to its accumulation in the cytoplasm and nuclear translocation, where it binds to T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF) and activates the expression of multiple EMT-related genes |

miR-205: negatively regulates the Wnt signaling pathway, reduces β-catenin stability, and inhibits EMT occurrence miR-1 and miR-124: directly target key components of the Wnt pathway (such as Frizzled or β-catenin itself) and indirectly regulate EMT through feedback |

| Notch signaling pathway | Notch signaling activates key EMT transcription factors (such as SNAIL and HEY family) through cell–cell contact-mediated receptor-ligand interactions, promoting mesenchymalization |

miR-146a: Downregulates Notch receptor expression, reduces pathway activity, and inhibits EMT miR-30 family: Affects Notch ligand (such as Jagged or Delta-like) expression and regulates Notch signal activation levels |

| PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | The PI3K/Akt pathway plays a central role in promoting cell proliferation, survival, and migration. Akt activation enhances the stability of EMT transcription factors such as SNAIL and TWIST, promoting the EMT process |

miR-155: Enhances PI3K/Akt pathway activity, promotes EMT and lung cancer cell migration ability miR-143 and miR-145: Negative regulation of PI3K/Akt activity, blocking downstream EMT-inducing factor expression, thereby inhibiting EMT progression |

| RAS/MAPK signaling pathway | The RAS/MAPK pathway (including ERK, JNK, and p38 branches) participates in EMT regulation by regulating the cell cycle, proliferation, and stress response. Its sustained activation promotes the expression of transcription factors such as ZEB and SNAIL, enhancing tumor cell migration | miR-221/222: Regulates MAPK activity by targeting RAS or its downstream factors (such as RAF and MEK), thereby affecting the expression of EMT-related genes. Enhances the migration ability of tumor cells. miR-7: Downregulates ERK/MAPK signaling, thereby inhibiting the EMT process |

Table 3.

Interactions between miRNAs and EMT-related transcription factors (such as SNAIL, ZEB, TWIST)

| EMT-related transcription factors | Functional mechanism | miRNA regulation |

|---|---|---|

| SNAIL | Members of the SNAIL family (including SNAIL1 and SNAIL2/Slug) are classic EMT inducers that inhibit E-cadherin expression by directly binding to the E-box sequence on the E-cadherin promoter, thereby promoting cell loosening and migration |

miR-34 family (particularly miR-34a): directly binds to the 3′-UTR of SNAIL1 mRNA, inhibiting its translation and thereby suppressing EMT. This effect is one of the downstream events mediated by the p53 pathway, suggesting its synergistic role in tumor suppression miR-203: Similarly, by targeting SNAIL1 mRNA, it exhibits tumor cell migration and EMT inhibitory functions in breast cancer and lung adenocarcinoma, demonstrating clear anticancer properties miR-200 family: Although its direct targets are primarily ZEB1/2, it also indirectly downregulates SNAIL expression through a feedback regulatory axis, synergistically inhibiting EMT |

| ZEB | The ZEB family (ZEB1 and ZEB2) can bind to the E-box site of the CDH1 promoter to inhibit E-cadherin transcription. It is widely involved in the regulation of EMT in NSCLC and forms an interactive regulatory loop with miRNA |

miR-200 family: Includes miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-141, and miR-429, which directly target the 3′-UTR of ZEB1 and ZEB2. They are currently the most well-defined negative regulators of ZEB. Their downregulation is significantly associated with the initiation of EMT and enhanced metastasis in lung cancer cells miR-153: Studies indicate that this miRNA targets ZEB2 and exhibits EMT-inhibitory activity in various solid tumors, although its mechanism of action in lung cancer remains to be further elucidated |

| Notch signaling pathway | Notch signaling activates key EMT transcription factors (such as SNAIL and HEY family) through cell–cell contact-mediated receptor-ligand interactions, promoting mesenchymalization |

miR-146a: Downregulates Notch receptor expression, reduces pathway activity, and inhibits EMT miR-30 family: Affects Notch ligand (such as Jagged or Delta-like) expression and regulates Notch signal activation levels |

| TWIST | TWIST1 is a basic helix-helix transcription factor widely expressed in metastatic tumors. It inhibits epithelial markers and activates mesenchymal marker expression, making it an important regulator of the EMT process. It is often associated with poor prognosis and drug resistance |

miR-214: Inhibits tumor cell migration and metastasis by directly targeting the 3′-UTR of TWIST1, thereby suppressing its translation. This effect has been reported in both breast cancer and lung cancer cells. miR-1238: A newly discovered miRNA, studies suggest that it can inhibit the EMT process by downregulating TWIST1 levels in certain lung cancer models miR-203: In addition to acting on SNAIL, it can also indirectly regulate TWIST expression, highlighting its importance in multi-pathway, multi-target regulation of EMT. EMT-related transcription factors such as SNAIL, ZEB, and TWIST play crucial roles in cell migration, invasion, and tumor metastasis. The expression of these transcription factors is regulated by miRNAs |

Heterogeneity of lung cancer miRNA expression among different subtypes and disease stages

The miRNA expression profile of lung cancer exhibits high heterogeneity across different subtypes and disease stages. The following is a systematic review from two dimensions, along with potential clinical implications.

miRNA heterogeneity between different stages

- Early (I-II) and advanced (III-IV) stages

- miR-101-3p Decreases with increasing stage in both LUAD and LUSC, issignificantly associated with distant metastasis, and can be used for early recurrence risk assessment.

- miR-144-3p Decreases with increasing stage in both subtypes; low expression is associated with poorer overall survival.

- miR-375 In LUAD, its expression level is positively correlated with p-TNM staging and lymph node metastasis, and can assist in N staging assessment.

- Metastatic vs. non-metastatic

- miR-7-5p Higher expression in LUAD without distant metastasis, suggesting that it may inhibit the metastasis process.

- miR-195-5p Low expression in primary LUSC lesions, associated with an increased risk of brain metastasis, and may become a predictive biomarker for CNS metastasis.

miRNA heterogeneity between different histological subtypes

- LUAD vs lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC)

- LUAD miR-6785-3p↑, miR-101-3p↓, miR-139-5p↓

- LUSC miR-21-3p↑, miR-650↑, miR-95-5p↓, miR-4689-3p↓, miR-744-3p.

- SCLC vs NSCLC

- miR-375 is upregulated in SCLC and downregulated in LUSC, suggesting that this miRNA can be used to distinguish between small cell and NSCLC.

- miR-7-5p is upregulated in LUAD, LUSC, and SCLC, but its expression intensity is negatively correlated with lymph node metastasis, making it useful for non-invasive monitoring of early-stage NSCLC.

The expression heterogeneity of miRNAs in lung cancer is not only evident among histological subtypes such as LUAD, LUSC, and SCLC, but also across different molecular subtypes and TNM stages within the same subtype. By integrating multi-omics data, standardizing testing procedures, and conducting large-scale validation, miRNAs can be transformed into important tools for subtype identification, staging refinement, prognosis assessment, and treatment selection.

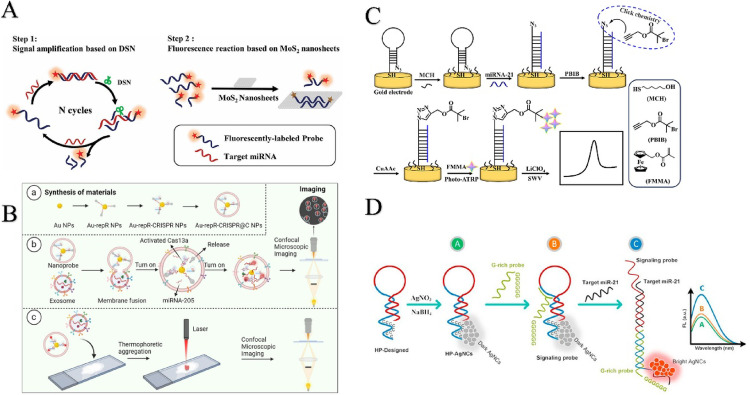

miRNAs as lung cancer disease markers in diagnosis

Early-stage lung cancer often presents as “asymptomatic” or with subtle symptoms, and most patients are diagnosed at stage III/IV. To improve patient survival rates, early screening and diagnosis are crucial. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new detection methods to identify lung cancer-related biomarkers with superior sensitivity. miRNAs hold great potential as diagnostic markers for lung cancer (Garbo et al. 2023; Cabrera et al. 2023). Since miRNAs are stably present in body fluids and their expression profiles exhibit tissue-specificity and disease-specificity, they can serve as non-invasive or minimally invasive diagnostic tools for lung cancer. For example, elevated levels of miR-21 and miR-155 in serum, along with reduced levels of miR-126, have been shown to be closely associated with the development of lung cancer. Additionally, miRNA expression can be used for molecular subtyping and prognostic assessment of lung cancer, providing a basis for personalized testing. Various methods have been employed to aid in lung cancer detection, including sputum cytology analysis, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, chest X-ray computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and breath analysis (Huang et al. 2025; Shimazaki et al. 2022; Yang et al. 2022b). However, each of these detection strategies has limitations in lung cancer screening and diagnosis, such as high cost, suboptimal sensitivity, radiation-related risks, and challenges in sample collection. Although enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) are the gold standard method for detecting many biomolecules associated with cancer detection, they still require longer assay times. In addition to the above options, there are several advanced technologies, including electrochemical sensing, fluorescence, Raman scattering, and colorimetry, which can also be applied to the detection of lung cancer biomarkers (Bhattacharjee et al. 2024; Liao et al. 2022). These methods are gradually becoming powerful tools for detecting lung cancer biomarkers due to their superior sensitivity and selectivity, non-invasive or minimally invasive nature, portability, and cost-effectiveness (Ao et al. 2022) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Lung Cancer Disease Detection Sensing and mRNA

miRNA target classification

miR-1290

miR-1290 has been reported as a potential biomarker for lung cancer. Studies have shown that the expression level of miR-1290 is significantly up-regulated in NSCLC tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues, which is one of the key drivers of tumorigenesis and cancer progression in human NSCLC (Liu et al. 2023). Interferon regulatory factor 2 (IRF2) has also been suggested to be a direct target of miR-1290, and overexpression of miR-1290 down-regulated IRF2 protein expression, suggesting that miR-1290 may be a potential target for NSCLC therapy.

miR-126

MiR-126 is thought to be associated with the aggressiveness of lung cancer (Huang et al. 2023). To reveal the relationship between miR-126 and lung cancer evolution, Sun et al. constructed an overexpressed miR-126 plasmid and transfected it into NSCLC cell line A549 cells. The results showed that overexpression of miR-126 in A549 cells increased the expression of epidermal growth factor-like structural domain 7 (EGFL7) in cancer cells, thereby promoting the proliferation of lung cancer cells (Sun et al. 2010).

miR-141

Human miR-141, a member of the miR-200 family, is thought to be associated with many human malignancies (Wu and Yan 2020). miR-141 expression is significantly increased in NSCLC tissues, and overexpression can accelerate both NSCLC cell proliferation in vitro and tumor growth in vivo (Mao et al. 2020).

miR-155

MiR-155-5p is located on chromosome 21 and has been reported to be an oncogenic miR in a number of cancers such as liver and breast cancer (Li et al. 2021a; Fu et al. 2024). In addition, miR-155 has shown its value in regulating respiratory diseases such as asthma and allergy, with miR-155-5p observed to be overexpressed in lung cancer cells (Pang et al. 2023; Zhu et al. 2020).

miR-21

MiR-21 is one of the most representative miRNAs associated with human malignant tumors (Nikolova et al. 2022). It is aberrantly expressed in lung and hepatocellular carcinomas (Ni et al. 2019; Zai et al. 2025). Recent studies have shown that miR-21-5p can promote cell survival, proliferation and migration by targeting the B cell translocation 2 gene (BTG2), while inhibiting apoptosis (Wang et al. 2023).

miR-25

MiR-25 is an atypical cancer marker associated with cervical and liver cancers. Recent studies have suggested that miR-25 may be associated with the development of lung cancer (Koohi et al. 2023). Wu et al. found that miR-25 could promote the proliferation of lung cancer cells while inhibiting their apoptosis. The regulator of apoptosis 1 (MOAP1) gene was identified as a novel target of miR-25, resulting in reduced cell proliferation and apoptosis (Wu et al. 2019).

Target amplification system

In the case of low RNA concentration in extracted cells or extremely low abundance of viral RNA in human body fluids, in order to improve the sensitivity of the detection reaction, nucleic acid sequence-based amplification is used to exponentially amplify the amount of the target nucleic acid, thus improving the sensitivity of the assay.

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is an amplification system that mimics the process of DNA replication, and it is one of the most widely used molecular biology techniques to amplify specific DNA fragments in vitro, belonging to the variable-temperature amplification (Terpe 2013). The principle of PCR is a three-step process, and three temperature points are set for denaturation, annealing, and extension: first, the DNA is denatured by high temperature (about 95 °C), then annealed at low temperature (about 25 °C), and finally extended at medium temperature (about 75 °C), under the action of Taq DNA polymerase. First, the ds DNA is denatured at high temperature (around 95 °C), then annealed at low temperature (around 25 °C), and finally extended at medium temperature (around 75 °C), and the primer strand is extended along the template under the action of Taq DNA polymerase. Other PCR-based amplification systems include real-time fluorescent PCR (qPCR), reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), and digital PCP (dPCR) (Vynck et al. 2023).

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) requires four specific primers as well as DNA polymerase with strand-substitution activity to thermostatically amplify nucleic acids at 60–65 °C (Asiello and Baeumner 2011). The basic principle of LAMP technology: based on six regions at the 3′ and 5′ ends of the target genes, design four pairs of specific primers, forward outward primer (FOP), forward inward primer (FIP), backward outward primer (BOP) and backward inward primer (BIP). During the reaction, the primer binds to the target gene, and under the catalytic action of strand replacement DNA polymerase, the primer extends and forms a dumbbell-like structure, which in turn triggers the strand replacement reaction to continuously synthesize new DNA strands, and ultimately forms a large number of amplification products. LAMP has the portability of a constant temperature and the specificity brought by the four specific primers, and it does not require costly reagents, which makes it have a more extensive application potential compared to PCR (Niessen 2014).

Recombinase polymerase amplification

Recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) has been described as an alternative to PCR for the detection of nucleic acids. RPA relies on three enzymes: recombinase that binds single-stranded nucleic acids (oligonucleotide primers), single-stranded DNA-binding proteins (SSBs), and strand-substitution DNA polymerases. The optimal reaction temperature for a mixture of these three enzymes is around 37 °C. The principle of the RPA reaction: first the recombinase protein forms a complex with the primer and searches for homologous sequences in the double-stranded DNA. The primer is then inserted into the homologous site by the strand displacement activity of the recombinase, and the single-stranded binding protein stabilizes the displaced DNA strand. The recombinase is then disassembled so that the 3′ end of the primer is strand-displaced and binds to the polymerase, which extends the primer and exponentially amplifies the target region on the template by repeating the process in a loop. In this system, complex instrumentation is not required and the amplification product can usually be detected in about 20 min (Zhao et al. 2022).

Rolling circle amplification

Rolling circle amplification (RCA) mimics the process of rolling circle replication of microbial circular DNA in nature. The main principle of RCA technology: using circular DNA as a template, dNTPs are converted into single-stranded nucleic acid products catalyzed by DNA or RNA polymerase through DNA or RNA primers (Li et al. 2021b). The RCA reaction can be carried out under isothermal conditions and does not require special instrumentation, which has the advantages of simple, rapid and efficient operation (Qing et al. 2021).

Hybridization chain reaction

Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) is an isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique without enzyme involvement. The principle is based on two or more hairpin-structured DNA probes. In the initial state, the hairpin probes are in a stable closed state. When the initiating strand is present, the initiating strand hybridizes with the loop portion of the first hairpin probe and opens the hairpin structure, and the exposed sticky ends are in turn able to hybridize with the second hairpin probe and open it, and so on, forming a long-stranded hybridized DNA polymer(Li et al. 2022).

Catalyzed hairpin assembly

Catalyzed Hairpin Assembly (CHA) is an isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique. The technique utilizes the specific binding of nucleic acid aptamers to the target molecule to trigger the self-assembly and amplification of the hairpin structure, thereby enabling the detection of the target molecule (Wang et al. 2022b). CHA technology mainly relies on two hairpin-structured DNA probes (H1 and H2), which work as follows: in the initial state the H1 and H2 hairpin structures are in a stable closed state. When the initiating strand is present, the initiating strand hybridizes with the loop of the first hairpin probe (H1) and opens the hairpin structure, and the exposed sticky end is able to hybridize with the second hairpin probe (H2) and open its hairpin structure. Subsequently, its sticky end hybridizes with the sticky end of H1 to form a longer double-stranded structure and displaces the sticky end of H1. Finally, the displaced H1 sticky end can in turn hybridize with and open another H2 hairpin structure, thus triggering a new round of chain displacement synthesis reaction (Wen et al. 2023). Through this cyclic reaction, new double-stranded structures can be continuously generated to achieve nucleic acid amplification (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of Detection of NSCLC via miRNA

| Author | Target | Technology | LOD | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Han | miR-25 | SWCNTs | 31.3 pM | Han et al. (2023) |

| Li | miR-155 | PAA | 10aM | Li et al. (2019) |

| Khodadoust | miR-141 | HCR | 0.89fM | Khodadoust et al. (2023) |

| Khodadoust | miR-141 | HCR | 1.24fM | Khodadoust et al. (2023) |

| Shao | miR-21 | HCR and Exo III-assisted amplification | 0.15 fM | Shao et al. (2025) |

| Chen | lncRNA | Au NCs/MWCNT-NH 2 | 42.8 fM | Chen et al. (2021) |

| Koohi | miR-25 | PEC Sensors | 3.4 fM | Koohi et al. (2023) |

| Si | miR-21 | Au@PDA@Ag | 0.2 fM | Si et al. (2020) |

| Xia | miR-196a | AgNW@AuNPs | 96.58 aM | Xia et al. (2020) |

| Xu | circRNA | CHA | 0.766 fM | Xu et al. (2024) |

| Chen | miR-21 | Au-DTNB@Ag | 2 nM | Chen et al. (2024) |

| Gao | miR-21 | MoS2s | 426 pM | Gao et al. (2021b) |

| Zhou | miR-205 | CRISPR-Cas13a | 1.1μL | Zhou et al. (2024b) |

| Yu | miR-21 | photo-ATRP | 1.35 fM | Yu et al. (2023) |

| Zoughi | miR-21 | AgNC | 2 pM | Zoughi et al. (2024) |

Entropy-driven amplification

Entropy-Driven Amplification (EDA), is an isothermal nucleic acid amplification technique. Unlike enzyme-driven, entropy-driven amplification does not require the involvement of enzymes and complex temperature changes, which also reduces unnecessary experimental conditions and prevents non-specific amplification (Zhang et al. 2019). The principle is that a DNA trigger strand is first required to bind to a substrate strand consisting of three DNA strands, followed by the introduction of a fuel strand, which triggers a strand displacement reaction and finally releases the trigger strand and another DNA strand (Cui et al. 2024). The trigger strand continues to trigger the next round of entropy-driven amplification, which is then cyclically activated to amplify biological signals, while the output DNA can be combined with other materials to expand to more applications (Zhu et al. 2023). EDA has excellent properties such as enzyme-free, isothermal and modular.

Biosensor-based pairs for detection of miRNAs in lung cancer

A biosensor is a device or equipment capable of converting biological signals into detectable signals, the concept of which was first proposed by Leland C. Clark Jr., an expert in electroanalytical chemistry and known as the “father of biosensors”, in 1962 (Clark and Lyons 1962). A typical biosensor consists of three components: a biorecognition element, a signal transducer, and a data analysis system. During the detection process, first, the biorecognition element (e.g., enzyme, cell, nucleic acid sequence, antibody, or protein) reacts with the target analyte in a specific recognition reaction to produce a measurable physical or chemical signal. Subsequently, a signal transducer converts and amplifies these raw signals to generate electrical, thermal, and optical signals. Finally, the data is processed by a data analysis system to produce a clear and intuitive visualization of the test results. Biosensors have a wide range of applicability, and can be used to detect liquid samples, solid samples, and are even suitable for live cell imaging. In addition, their development potential also includes in vivo imaging technology, which shows significant promise in the field of medical diagnosis and biological research. Biosensors can be categorized according to the detection principle: thermal biosensors (Zheng et al. 2006; Bjarnason et al. 1998), optical biosensors (Wu et al. 2023), electrode biosensors (Rajarathinam et al. 2021).

Electrochemical sensing

Electrochemical detection technology is a rapidly evolving field that has established simple and low-cost manufacturing methods. Its advantage lies in the direct generation of electronic signals through electrochemical reactions, which can be effectively combined with miniaturized hardware to achieve fast, accurate and economical detection. The main features of electrochemical detection are high accuracy and a wide measurement range. Liu et al. designed a 3D DNA origami structure to enable electrochemical detection of miRNAs associated with lung cancer (Liu et al. 2015). The structure consists of ferrocene-labeled DNA with a stem-loop structure and a bottom thiolate tetrahedral DNA nanostructure. The principle is that the top DNA hybridizes with specific miRNAs (e.g., miRNAs associated with lung cancer), while the bottom self-assembles onto the surface of a gold disk electrode modified with gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) and closed with mercaptothion (MCH). The preparation process and performance of this electrochemical gene sensor were fully characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV).

Under optimized experimental conditions, the developed gene sensor exhibited a detection limit of 10 pM and good linearity in the concentration range of 100 pM to 1 µM, demonstrating great potential for application in highly sensitive clinical cancer diagnosis. In addition, a recently developed electrochemical nanogene sensor based on AgNPs/SWCNTs nanohybrids was also effective in detecting miR-25 (shown in Fig. 3A) (Han et al. 2023). The detection mechanism of this sensor involves the interaction of multiple components, each of which plays a specific role in the detection process. SWCNTs (single-walled carbon nanotubes) interact with the probe molecules, while AgNPs (silver nanoparticles) share electrolytic signals. Specifically, DNA and CNTs bind via π–π superposition, but it is worth noting that the π-π interactions between CNTs and dsDNA are weaker, while those with ssDNA are stronger. When the probe and target are fully complementary, the nanotubes cannot bind to double-stranded DNA and vice versa. Based on this principle, the sensor distinguishes between complementary, single-base mismatches, and non-complementary targets by comparing the peak currents to achieve highly specific detection of miR-25. The sensor exhibited a high sensitivity with an LOD of 31.33 pM. Nanopore technology has unique advantages in separation, catalysis and biosensing, especially nanopores with special molecular and ionic transport properties. In recent years, porous anodized aluminum oxide (PAA) nanopore array/Au electrodes have demonstrated superior performance over conventional metal nanoparticles (NPs) electrodes in miRNA detection. In order to further improve the detection performance, Li et al. improved the traditional nanopore technology and prepared a new PAA/Au electrode, which was successfully applied to the detection of miR-155 (e.g., Fig. 3B) (Li et al. 2019). The direct use of PAA nanopores requires the early removal of the barrier layer, which leads to an increase in nanopore size and a decrease in spatial impedance and charge repulsion. To solve this problem, gold nanowires were first electrodeposited into nanopores in porous anodized aluminum oxide films. Then, the inner surfaces of the nanopores were functionalized with electroneutral morpholino with a specially designed sequence. After the introduction of the target miRNA-155, a morpholine-miRNA structure was developed. The resulting electrodes exhibited excellent sensitivity and selectivity due to enhanced spatial impedance and charge repulsion. At the lowest sample concentration, the true LOD was only 10 aM, demonstrating ultra-high sensitivity. Graphite electrodes, glassy carbon electrodes, paper-based electrodes, and nanowires for miRNA detection were presented by Chen (2023; Yarali et al. 2022). The sensor consists of graphene oxide (GO) and gold nanoparticle (GNR)-modified glassy carbon electrodes (GCEs). Compared to glassy carbon electrodes, graphene oxide electrodes are less time-consuming, with a miRNA detection time of 35 min. It is simple, low cost, disposable and portable. Polyamide-amine dendritic functionalized polypyrene nanowires have a high active specific surface area, allowing more DNA probes to attach to the modified electrode, and the resistance of the modified electrode to contamination has not been discussed. The detection of miRNA using the nanowire electrode was in the range of 10–14–10–8 M, with a LOD of 0.34 × 10–14 M. Due to the advantages of the covalent grafting method of PAMAM, such as short time, simple operation, and no need for pretreatment of pyrrole monomers, this method can effectively increase the sensitivity of the analysis of lung cancer. The detection of a single miRNA is not sufficient for rapid detection, therefore, Ali Khodadoust et.al developed a hairpin structured DNA (dhDNA) probe based on dual-signal labeling to construct a new type of nano biosensor (Fig. 3C) (Khodadoust et al. 2023). This single hairpin structured probe consists of a thiolated methylene blue labeled hairpin capture probe (MB-HCP) as an internal reference probe and a ferrocene-modified anti-miRNA-21 DNA probe (Fc-AP-21). The novel integrated structure of MB-HCP and Fc-AP-21 is designed at a sensing interface for sensitive and simultaneous detection of miRNA-141 and miRNA-21 in a single assay. In addition, the biosensor was first prepared by immobilizing dhDNA (Fc-AP-21/MB-HCP) on a modified glassy carbon electrode. After hybridization with the anti-miRNA-141 complementary sequence (ACP-141), the dhDNA structure was forced to open and form the final structure of the biosensor. In addition, miRNA-141 and miRNA-21 dissociate from the double-stranded structure due to the high sequence match between miRNA-141 and ACP-141 as well as miRNA-21 and Fc-AP-21. A linear relationship was found between the logarithm of miRNA-141 and miRNA-21 concentrations and signal changes. This feature is used to detect two miRNAs. This sensitive biosensor provides low detection limits of 0.89 and 1.24 fM for miRNA-141 and miRNA-21. In addition, it has a wide linear range of 2.0 to 105 fM for highly selective and accurate results in plasma samples. Therefore, this strategy is expected to be a suitable platform for simultaneous and early detection of various cancer biomarkers. Recently, Shao et.al proposed a ratiometric electrochemical sensor for the ultrasensitive detection of miRNA-21 using dual-signal amplification, hybridization chain reaction and Exo III-assisted amplification (Fig. 3D) (Shao et al. 2025). Methylene blue (MB) and heme were selected as the two electrochemical. A ratiometric electrochemical sensor was then developed that showed good miRNA-21 detection performance with a concentration range of 1 fM to 10 nM. Notably, the detection limit of this biosensor was 0.15 fM. Overall, this miRNA detection strategy holds significant promise for early lung cancer screening.

Fig. 3.

A Recent strategies for electrochemical sensing detection of miRNAs in lung cancer; B Ultrasensitive detection of microRNA using an array of Au nanowires deposited within the channels of a porous anodized alumina membrane; C High-performance strategy for the construction of electrochemical biosensor for simultaneous detection of miRNA-141 and miRNA-21 as lung cancer biomarkers; D Detection of microRNA-21 based on smartly designed ratiometric electrochemical sensor and dual-signal amplification

In addition, Chen et al. developed a novel effective and ultrasensitive electrochemical biosensor (Fig. 4A) based on the combination of gold nanocages and amidated multi-walled carbon nanotubes (Au NCs/MWCNT-NH 2) decorated screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) (Chen et al. 2021). Due to its large surface area, excellent electrical conductivity and superior biocompatibility, this SPCE Au NCs/MWCNT-NH 2 lncRNA biosensor showed a wide linear range (10−7–10−14 M) and low detection limit (42.8 fM), providing satisfactory screening for NSCLC and monitoring of the disease progression with high selectivity and stability. On the basis of electrochemistry, on this basis, Fereshteh Koohi et al. developed a photoelectrochemical (PEC) biosensor to measure the concentration of miR-25 as a biomarker of lung cancer (Fig. 4B) (Koohi et al. 2023). To fabricate the PEC biosensor, suitable amino-modified probes were immobilized on the surface of fluorotic oxide (FTO) electrodes modified with bismuth vanadate (BiVO4) film and gold nanoparticles (AuNP). The fabrication steps of the PEC biosensor were monitored by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and PEC measurements. The results showed that BiVO4 films and AuNPs enhanced the separation of photogenerated electrons and increased the photocurrent signal. The photocurrent was significantly reduced after hybridization of the probe immobilized on the biosensor with miR-25. This decrease in current is due to the fact that the hybridization process blocks the electrode surface by creating a spatial site resistance and reducing the diffusion of AA to the electrode surface, which reduces AA oxidation and subsequently reduces the capture of photogenerated holes. Therefore, the amount of photocurrent reduction depends on the concentration of miR-25, and this PEC biosensor can be used to measure miR-25. The developed PEC biosensor shows good sensitivity for the determination of miR-25 over a linear concentration range of 1.0 × 10–14–1.0 × 10–6 M, and under optimal conditions, the limit of detection is 3.4 fM. With this biosensor, the detection of miR-25 from non-complementary and one-base heterodimers is possible. Using this biosensor, miR-25 can be detected from non-complementary and one base mismatch sequences. miR-25 can also be measured in human serum samples using the PEC biosensor with satisfactory results.

Fig. 4.

A A novel biosensor for the ultrasensitive detection of the lncRNA biomarker MALAT1 in non-small cell lung cancer; B Photoelectrochemical biosensor based on FTO modified with BiVO4 film and gold nanoparticles for detection of miRNA-25 biomarker and single-base mismatch

The electrochemical strategy has good reproducibility and high selectivity, and the discussion of experimental data can be expressed in various forms, which can better reflect the reality of the experiment. It has good prospects for the detection of lung cancer markers. However, the technique has the disadvantage of relying on time and signal value changes for analysis. The detection time sometimes takes hours and is too long. Prolonged assays have a particular impact on the accuracy of experimental results, with electrode surface defects and redox reactions affecting the results. This often limits the selectivity of the biosensor to complex substrates and controls the background response.

Raman sensing

When certain molecules are adsorbed on the surface of certain rough metals (e.g. silver, copper, gold, etc.), the intensity of their Raman effect increases accordingly, a phenomenon known as the Surface Enhanced Raman Effect (SERS). When a laser beam is shone on a metal surface, a Raman reflection is formed. Different Raman values are obtained when different substances are combined on the metal surface. On this basis, Si et al. constructed a CHA-SERS sensor array with four different sensing units using four different hairpin structures immobilized on four Au/Ag alloy nanoparticles (Au-AgNPs) (Fig. 5A) (Si et al. 2020). The SERS sensor successfully detected a variety of lung cancer-associated miRNAs in buffer, serum and cellular RNA extracts. The SERS sensor successfully detected multiple lung cancer-associated miRNAs (miR-1246, miR-221, miR-133a, and miR-21) in buffer, serum, and cellular RNA extracts. A unique “hotspot” consisting of Au@PDA@Ag nanocomposites enhanced the Raman signal and sensitivity. To improve detection sensitivity, a cyclic enzyme amplification system was developed in which a punctate endonuclease triggers the nucleic acid reaction system into an amplification cycle. The addition of the dot endonuclease to the cyclic enzyme amplification system resulted in a detection limit as low as 0.2 fM, which significantly improved the sensitivity. Xia et al. were used for the rapid detection of lung cancer-associated miRNAs (miR-196a) (Fig. 5B) using bimetallic Au–Ag nanowires (AgNW@AuNPs) substrate with the target hairpin DNA (Xia et al. 2020). Finite-difference time-domain simulations demonstrated that a large number of “hot spots” were generated between AgNW and AuNPs, leading to a huge enhancement of the Raman reporter signal. Filter paper hydrophobically treated with hexadecenyl succinic anhydride and modified with AgNWs@AuNPs was used as the capture substrate. miR-196a detection limits in PBS and serum were as low as 96.58 aM and 130 aM, respectively. Studies of non-specific sequence and single-base mismatches of miRNAs showed that the SERS-based platform was highly selective, extremely homogeneous and reproducible. Finally, the platform was used to show that the expression of miR-196a in the serum of lung cancer patients was much higher than that of healthy individuals. The assay results indicate that the SERS platform has potential applications in cancer diagnosis and may be a viable alternative to the traditional miRNA detection method of real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technology. Xu et al. combined SERS with a CHA for the detection of cyclic RNA associated with tumor formation and progression (circRNA) (Fig. 5C) (Xu et al. 2024). The signal of the Raman Reporter is significantly enhanced by the use of core–shell nanoprobes and 2D SERS substrates with calibrated functionality to generate abundant SERS “hotspots”. This method enables sensitive (LOD: 0.766 fM) and reliable quantitative detection of the target circRNA. In addition, we used the developed biosensor to detect circRNA in human serum samples and found that circRNA concentrations were higher in lung cancer patients than in healthy subjects. In addition, the article describes unique circRNA concentration distributions in early stages (IA and IB) and subtypes (IA1, IA2, and IA3) of lung cancer. These results demonstrate the potential of the proposed optical sensing nanoplatform as a liquid biopsy and prognostic tool for early screening of lung cancer. Chen et al. designed a novel up conversion-based multimodal lateral flow assay (LFA) system for detecting microRNAs in body fluids by simultaneously generating three unique signals within the assay strips (Fig. 5D) (Chen et al. 2024). Core–shell Au-DTNB@Ag nanoparticles acted as both Raman reporter molecules and acceptors, bursting the fluorescence of upconverted nanoparticles (UCNP, NaYF: Yb, Er) via a Förster resonance energy transfer mechanism. Using microRNA-21 as a representative analyte, the LFA system provided an excellent detection range from 2 nM to 1 fM, which was comparable to the results of the signal amplification method, due to the successful monolayer self-assembly of UCNP on the NC membrane, which dramatically increased the detection range and enhanced the convenience and sensitivity for lung cancer detection.

Fig. 5.

A Catalytic Hairpin Self-Assembly-Based SERS Sensor Array for the Simultaneous Measurement of Multiple Cancer-Associated miRNAs; B SERS Platform Based on Bimetallic Au–Ag Nanowires-Decorated Filter Paper for Rapid Detection of miR-196ain Lung Cancer Patients Serum; C Optical Nanobiosensor Based on Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy and Catalytic Hairpin Assembly for Early-Stage Lung Cancer Detection via Blood Circular RNA; D A versatile upconversion-based multimode lateral flow platform for rapid and ultrasensitive detection of microRNA towards health monitoring

SERS offers exceptionally high sensitivity, excellent specificity, diverse analytical capabilities, and better stability, leading to less background noise, non-destructive and nondestructive detection, and resistance to autofluorescence interference, effectively avoiding the need for in vivo detection. Interference of autofluorescence signals from biomolecules has been applied to the detection and measurement of tumor biomarkers in clinical samples. However, there are some shortcomings, such as poor spectral reproducibility due to substrate inhomogeneity, lack of SERS probes limiting the application of SERS technology, and short assay lifetime when activated gold and silver nanoparticles are exposed to corrosive or toxic environments for long periods of time, and are susceptible to interferences, such as chemical corrosion, physical damages, and bio-contamination, leading to false-positive signal or reduced SERS activity of the substrate.

Fluorescent sensors

Gao et al. developed a fluorescence quantitative detection method for exosomal miRNAs in lung cancer cells using the fluorescence bursting property of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) (Fig. 6A) (Gao et al. 2021b). Enzyme-assisted signal amplification properties of nanosheets and double-strand-specific nuclease (DSN). First, target miRNAs were hybridized using fluorescently labeled nucleic acid probes to form DNA/RNA heterodimeric structures. In the presence of DSN, the DNA single strand in the DNA/RNA heteroduplex is selectively digested into smaller oligonucleotide fragments. At the same time, the released miRNA target triggers the next reaction cycle, resulting in signal amplification. MoS2 then selectively quenches the fluorescence of the undigested probe with the “oligonucleotide”, leaving the fluorescence signal of the fluorescently labeled probe fragment. miRNA-21 fluorescence signals have a maximum excitation/emission wavelength of 488/518 nm. Most importantly, the biosensor was then used to extract the fluorescence signal of the miRNA-21 from the exosomal lysate of human plasma. Exosome lysates for accurate quantitative detection of miRNA-21. miRNAs encapsulated in tumor-associated exosomes have emerged as valuable biomarkers for early cancer detection. However, the flexible structure and inherent instability of RNAs limit their application in bio diagnostics. The CRISPR-Cas13a system, known for its target-responsive “collateral effects” is a powerful tool for advancing cancer diagnostics. In this study, we utilized the CRISPR-Cas13a system as an innovative signal amplification tool for fluorescence imaging of cancer-associated exosomal miRNAs (Fig. 6B) (Zhou et al. 2024b). In addition, we utilized the thermophoretic aggregation effect exhibited by AuNPs to consolidate the fluorescent signals generated by the CRISPR-Cas13a system. Subsequently, the developed nanoprobes were used to detect exosomal miRNAs associated with lung cancer in human serum, thus enabling the visualization of aggregation of low abundance cancer exosomes in individuals with lung cancer compared to healthy individuals. This sensitive thermophoretic aggregation assay provides a diagnostic tool for clinical lung cancer. Yu et al. The development of a convenient and efficient assay using miRNA-21 as a lung cancer marker is important for the early prevention of cancer (Fig. 6C) (Yu et al. 2023). Here, an electrochemical biosensor for the detection of miRNA-21 was successfully prepared using click chemistry and photocatalytic atom transfer radical polymerization (photo-ATRP) under blue light excitation. The biosensor employs a hairpin DNA recognition probe and utilizes a photocatalytic system comprising fluorescein and pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA) to deposit numerous electroactive monomers (ferrocenylmethyl methacrylate, FcMMA) on the electrode surface, achieving significant signal amplification. The biosensor is sensitive, precise and selective for miRNA-21 and highly specific for RNAs with different base mismatches. Under optimal conditions, the biosensor was linear in the range of 10 fM–1 nM (R2 = 0.995), with a detection limit of 1.35 fM. In addition, the biosensor showed anti-interference performance in analyzing RNA in serum samples. The biosensor is based on green chemistry and has the advantages of low cost, high specificity, and high interference resistance, which provides economic benefits while achieving the detection goals and has a promising application in the analysis of complex samples. Sheida Zoughi et al. introduced a novel biosensor based on silver nanoclusters (AgNC) for the detection of miR-21 (Fig. 6D) (Zoughi et al. 2024). As fluorescent probes, rationally designed hairpin sequences containing polycytosine motifs were used to promote AgNC formation. Guanine-rich sequences were also used to enhance the sensing signal. It was found that in the absence of miR-21, the addition of guanine-rich sequences to the detection probe caused only a slight change in the fluorescence emission intensity of AgNCs. When miR-21 was present, the emission signal was enhanced. There was a direct correlation between the increase in AgNC fluorescence and miR-21 concentration. The performance of the proposed biosensor was thoroughly characterized and confirmed. The biosensor detected miR-21 in the applicable linear range of 9 pM to 1.55 nM (LOD: 2 pM). The designed biosensor was successfully applied to detect miR-21 in human plasma samples as well as in human lung cancer cells. This biosensing strategy can be used as a model for the detection of other miRNAs. The designed nano biosensor can measure miR-21 without using any enzyme, with fewer experimental steps and at a lower cost compared to biosensors reported in the field.

Fig. 6.

A In situ detection of plasma exosomal microRNA for lung cancer diagnosis using duplex-specific nuclease and MoS2 nanosheets; B Thermophoretic Aggregation Imaging of Tumor-Derived Exosomes by CRISPR-Cas13a-Based Nanoprobes; C Ultrasensitive detection of miRNA-21 by click chemistry and fluorescein-mediated photo-ATRP signal amplification; D Rapid enzyme-free detection of miRNA-21 in human ovarian cancerous cells using a fluorescent nanobiosensor designed based on hairpin DNA-templated silver nanoclusters

Currently, miRNAs have great potential for application in NSCLC research, but they also face many limitations and challenges. The following are some of the major limitations and challenges: 1. Complexity of target selection. Diversity and complexity: miRNAs can target multiple genes and affect complex biological pathways, and certain miRNAs may have different functions in different cell types and tumor microenvironments. This leads to complexity in selecting appropriate miRNA targets in specific cancer types. Redundancy: Many miRNAs may have redundant functions, and the same pathway may be regulated by multiple miRNAs, so the effectiveness of a single miRNA assay may be limited. 2. Complexity of clinical trial design: Insufficient sample size: Many miRNA-related clinical trials have small sample sizes, which limits the statistical significance of the results and the ability of clinical generalization. Validation of prognostic markers: the study of miRNAs as prognostic biomarkers is not yet fully mature, and larger long-term follow-up studies are needed to validate their effectiveness in the clinic. 3. Non-specific expression of biomarkers. Changes in expression profiles: The expression levels of miRNAs in cancer patients are affected by a variety of factors (e.g., age, gender, lifestyle, etc.), which may lead to a decrease in the specificity of miRNAs as biomarkers. Individual differences: the miRNA expression profiles of different patients vary greatly, which limits the individualization and promotion of the application of therapeutic regimens. 4. Inadequacy of mechanism research: Inadequate knowledge of miRNA function: although the roles of some miRNAs have been identified, the specific mechanisms of most miRNAs are still unclear, and a comprehensive understanding of their complex roles in cell biology has yet to be achieved. Influence of the tumor microenvironment: the role of miRNAs in the tumor microenvironment needs to be studied in depth, as cellular and signaling pathway interactions in the tumor microenvironment may affect miRNA function.

Treatment of NSCLC with miRNA

Among all treatment strategies, chemotherapy remains the primary treatment method for patients with non-small cell lung cancer, particularly for those with advanced-stage cancer. Tumor cell resistance mechanisms have reduced the therapeutic efficacy of most chemotherapy drugs currently used for NSCLC (Arora et al. 2022; Ettinger 2000). Research has identified that some common signaling pathways, namely the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR and MDM2/p53 signaling pathways, are involved in chemotherapy resistance in lung cancer (Deng et al. 2023). In addition to these signaling pathways, other important mechanisms, such as overexpression of efflux transporters (ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters), activation of the TME, and EMT processes, also contribute to chemotherapy resistance (Bouzbib et al. 2022).

Taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel, and cabazitaxel) are the drugs of choice for treating NSCLC and are usually used in combination with other lung cancer drugs (Zhang et al. 2023). Similarly, NSCLC patients often exhibit paclitaxel resistance. In an experimental study, miR-650 caused lung cancer cells to become resistant to docetaxel treatment by controlling the expression of Bcl-2/Bax (Alkhathami et al. 2024). Numerous other miRNAs have been analyzed for their therapeutic effects in regulating resistance to the aforementioned and other chemotherapy drugs. Given the aforementioned advantages of miRNAs in regulating key deficiencies in chemotherapy operations, miRNAs can be considered as potential biomarkers for predicting drug resistance in NSCLC patients (Li et al. 2024; Zu et al. 2023).

Treatment of NSCLC remains difficult due to the complex pathogenic pathways that drive tumor progression and metastasis, including the intrinsic resistance of tumor cells to chemotherapy, radiation, and other currently available treatment regimens (Sampat et al. 2024; Zhang et al. 2021). The rising importance of miRNAs in cancer therapeutic research, notably in NSCLC, has been validated by multiple preclinical studies and a small number of Phase I clinical trials. miRNAs’ potential and utility as biomarkers for NSCLC management and treatment can be attributed to their multifaceted characteristics, which regulate various stages of tumorigenesis, including cell proliferation, cancer stem cell properties, apoptosis, cell migration and invasion, EMT and metastasis, angiogenesis, and related signaling pathways.

Although the use of miRNAs for NSCLC treatment offers tremendous benefits, there is still a need to apply these beneficial therapeutic biomarkers in an ad hoc manner. Some of the key challenges that need to be addressed include improving tissue/tumor specificity, elucidating the pharmacokinetics of delivery, the stability of therapeutic biomarkers, potential off-target effects, miRNA-mediated toxicity, dose determination, and immunological activation.

Conclusion

miRNAs play a crucial regulatory role in the EMT process of lung cancer, modulating EMT-related signaling pathways through complex networks and influencing the progression and metastasis of lung cancer. In-depth investigation of the relationship between miRNAs and lung cancer EMT not only helps elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying lung cancer development but also provides new insights for the early diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. Future research should focus on: (1) Systematically analyzing the spatiotemporal regulatory map of miRNA-driven lung cancer EMT through multi-level molecular networks; (2) Developing a highly sensitive miRNA detection platform based on multi-omics integration, establishing a three-dimensional early screening scheme involving plasma exosomes, tissue, and single cells, and achieving ultra-early precise diagnosis of lung cancer; (3) Developing next-generation miRNA mimics/inhibitors delivery systems and constructing intelligent treatment models capable of real-time monitoring of efficacy and safety; (4) Integrate interaction information between miRNA and DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin remodeling to map the comprehensive epigenetic regulatory network of lung cancer EMT. As clinical translation accelerates, miRNA will become a core target for early diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer, bringing breakthrough survival benefits to patients.

miRNAs play a key role in the EMT process of lung cancer, which is believed to be closely related to tumor invasiveness and metastasis. The expression levels of certain miRNAs are closely related to the prognosis of lung cancer patients and can serve as potential biomarkers for evaluating treatment efficacy and prognosis. The main challenges facing clinical application are the cultivation of high-quality talent. To address this issue, scientific researchers can be recruited, or hospital technical personnel can undergo regular technical training to overcome this limitation. The variability of patient responses or the validation of biomarkers can be achieved through pathological tissue sections or by screening for nucleic acid aptamers of mutated biomarkers for detection, thereby assisting in validation. In the future, we will conduct in-depth research into the specific mechanisms of miRNAs in lung cancer EMT to identify new targets and treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

Inner Mongolia Medical University Science and Technology Innovation Team—Pleural Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Innovation Team (No. YKD2022TD013); Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation Joint Project (No.2023LHMS08062); National Natural Science Foundation Cultivation Project (No.2023NYFYPY005); Inner Mongolia Medical Academy Key Project—Public Hospital Research Joint Fund Science and Technology Project (No.2024GLLH0314). Clinical Application Study on the Construction of a Predictive Model for Risk Factors Associated with Pulmonary Infection by Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Using BALF Combined with mNGS (No. YSXH2024KYF028). Clinical Medical Research and Promotion of New Clinical Technologies Project of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Medical Association, 202407-202612.

Author contribution

Shi, Zhao, Wang and Xiao edited the manuscript and Feng and Gu examined it.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note