ABSTRACT

Introduction

Regenerative endodontic treatment (RET) aims to promote root maturation in necrotic immature teeth, where effective microbial disinfection is crucial for treatment success. This study evaluated the effect of calcium hydroxide (CH) and 2% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHD) as intracanal medicaments and their impact on bacterial loads and RET outcomes.

Methods

The material consisted of bacterial samples from 41 patients who participated in a previously conducted randomized controlled clinical trial comparing CH and CHD during RET. A total of 123 microbial samples were analyzed using real‐time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Bacterial loads were assessed at three time points: before root canal disinfection (S1), after root canal disinfection (S2), and after intracanal dressing (S3). The microbial composition was evaluated at the kingdom (Eubacteria), phylum (Actinomycetota), and species ( Enterococcus faecalis ) levels.

Results

Significant reductions in bacterial loads were observed after root canal disinfection (S2) in both CH and CHD subgroups, regardless of treatment outcome. Further reductions after intracanal dressing (S3) occurred exclusively in the successful cases. Actinomycetota loads significantly decreased after root canal disinfection in the successful cases but remained unchanged after intracanal medication. The presence of E. faecalis after intracanal dressing was associated with failed RET (OR = 9.778; p = 0.0432), although no significant differences in the effectiveness of the intracanal medicaments were found.

Conclusion

Both CH and CHD effectively reduced bacterial loads, with greater reductions linked to successful outcomes. The association between E. faecalis and failed RET suggests that this species may play a role in treatment outcomes. Further research, including microbiome profiling, is desirable to identify potential prognostic markers for failed RET.

Keywords: antibacterial effectiveness of calcium hydroxide and 2% chlorhexidine, bacterial loads, immature traumatized teeth, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, regenerative endodontic treatment

1. Introduction

In the last decades, regenerative endodontic treatment (RET) has been introduced as a promising alternative to conventional apexification techniques for the treatment of traumatized immature permanent teeth with root canal infection and apical periodontitis [1]. RET is a biological treatment aimed at achieving regeneration of the pulp‐dentin complex to facilitate continued root maturation in which dental stem cells are an important component [2, 3]. Even though numerous types of stem cells have been isolated from dental tissue, the stem cells of the apical papilla (SCAPs) have been recognized to play a key role in RET [4, 5].

Conventional endodontic treatments for immature necrotic teeth, including apexification with calcium hydroxide (CH) and mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) apical plug, are limited by their inability to promote root maturation and might pose a risk of premature tooth loss [6, 7]. In contrast, studies employing RET report continued root maturation, a critical factor for the long‐term survival of the immature necrotic traumatized teeth [8, 9].

Most importantly, the success of RET is dependent on the elimination of the microorganisms present in the root canal. However, evidence exists that it is challenging to eradicate bacterial infection in immature traumatized teeth due to several complicating issues. First, the bacterial invasion might occur from the external structures of the tooth, for example, from the periodontal ligament in cases with luxation injuries, which makes it difficult to address [10]. Second, the current RET treatment protocol implies no or minimal mechanical instrumentation to avoid further weakening of the tooth [11]. At the same time, the microorganisms are shown to form a biofilm that remains firmly attached to the root canal walls if no mechanical debridement is performed [12, 13]. As a result, there is a risk of persisting bacterial infection after completed treatment leading to treatment failure [14, 15].

Several highly virulent species have been associated with endodontic treatment failure. The most common representatives are the genus Actinomyces [16] containing 14 different anaerobic Gram‐positive species statistically associated with abscesses, cellulitis, and symptomatic teeth [17] and the species E. faecalis [18]. Moreover, it has been reported that E. faecalis or its DNA remnants may interact with SCAPs, causing a significant reduction in their proliferation [19].

Considering the lack of mechanical debridement in RET, a variety of combinations of irrigation solutions and antimicrobial intracanal dressings have been proposed including different combinations of triple antibiotic paste, double antibiotic paste, chlorhexidine gluconate (CHD) and CH [20]. Despite the ability of antibiotic combinations to eradicate bacteria in dentinal tubules [21], their toxicity to SCAPs seems to be a concern at higher concentrations [22, 23]. Based on this evidence, the American Association of Endodontists proposed low concentrations of antibiotics or CH as intracanal dressings, while the European Society of Endodontology proposed CH as a first‐choice intracanal dressing [11, 24]. It was furthermore recently demonstrated that CHD and CH were highly effective in combating endodontic pathogens [25]. Thus, antibiotic pastes should not be seen as a necessity in the disinfection of root canals.

Our previous findings using strict anaerobe culture techniques indicate that the primary microbiota in the successful cases of RET exhibited greater diversity compared to the failed cases. Moreover, the successful cases generally demonstrated more substantial bacterial reductions, though no particular species was consistently linked to treatment outcomes, and no significant differences were found in the disinfection efficacy of intra‐canal dressings with calcium hydroxide or chlorhexidine gluconate [26]. However, a deeper exploration of bacterial load and its association with the outcomes of RET remains an area requiring further investigation.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the disinfection efficacy of CH and CHD dressing regarding total bacterial load and influence on treatment outcomes of RET.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Outcome Measures

The study population, selection of participants and clinical procedures are described in detail in our previous study [26]. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the 64th WMA Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained by the Regional Ethical Review Board at (anonymized). The manuscript of this study has been written according to Preferred Reporting Items for Laboratory studies in Endodontology (PRILE) 2021 guidelines [27].

All patients and their parents signed informed consent to participate prior to onset of the study. The patient data were coded and stored according to principles of the general data protection regulation.

In brief, this study included bacterial samples from 41 children and adolescents (aged 6–13 years) with traumatized, necrotic, immature permanent incisors treated at specialist clinics in (anonymized). Patients were randomized to receive root canal dressings of either CH (calcium hydroxide paste, Calasept, Directa AB, Upplands Väsby, Sweden) or 2% CHD gel (Gluco‐CHeX 2% gel, PPH Cerkamed, Stalowa Wola, Poland) during RET. Patients were monitored clinically and radiographically every 6 months after the traumatic dental injury for up to 7.69 years (mean observation time 3.84 years; range 1.19–7.69 years). Success was defined by the resolution of clinical symptoms, radiographic healing, and continued root development, while failure was marked by persistent symptoms, apical periodontitis, lack of continued root development or no apex closure assessed at the final follow‐up [28].

2.2. Clinical and Microbiological Sampling Procedures

The clinical and microbiological sampling procedures are shown in Figure 1 and have been previously described [26]. Local anesthesia was administered before isolating the tooth with a rubber dam and retainer. Access preparation was confined to the enamel using a high‐speed bur. Disinfection of the tooth crown, retainer, and rubber dam was carried out sequentially with sterile foam pellets soaked in hydrogen peroxide (30%) and chlorhexidine‐ethanol solution (5%), followed by treatment with a 5% sodium thiosulfate solution to neutralize residual disinfectants. To monitor for contamination, bacterial samples were obtained from the disinfected crown surface at both the initial (S1) and the second appointment (S4). Each sample was processed by placing one foam pellet into fluid thioglycolate medium with agar for incubation under 5% CO2 conditions for 7 days. Teeth exhibiting bacterial growth in contamination control Samples S1 and S4 (n = 5) were excluded from subsequent microbiological analyses.

FIGURE 1.

Flow‐chart of the sampling time‐points during regenerative endodontic treatment.

2.3. The Bacterial Samples Were Collected at Three Different Time‐Points

As previously described [26], Sample S1 was collected by accessing the pulp chamber through the dentine with a sterile burr. Sterile saline was applied into the root canal, allowing it to fill up to the level of the cementum‐enamel junction, while the pulp chamber was left dry. Dentin shavings were produced by striking a sterile hand file (K 20) against the root canal wall to reach adherent biofilm microbiota. The fluid was absorbed with three sterile paper points, which were held in the root canal for 1 min. The collected sample was then immediately transferred into a tube with reduced transport medium (anaerobic sterilized VMG III medium, Department of Oral Microbiology, Umeå) as the samples were intended for both qPCR analysis (in this study) and for cultivation, as previously published [26].

Sample S2 was collected following root canal disinfection. Initially, the root canal was irrigated with 0.5% buffered sodium hypochlorite, followed by ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 2 mL of sterile saline solution. Following debris removal, the irrigants were inactivated using 1 mL of sodium thiosulfate for 1 min. The inactivating solution was dried using sterile paper points, and the canal was flushed again with 2 mL of sterile saline, which remained during the sampling process. A sterile hand file (K 20) was then used to scrape the root canal wall, generating dentinal shavings from which the bacterial sample was collected and transferred to VMG III. Following the sample collection, a dressing material consisting of CH or CHD was applied according to a block randomization protocol, and the access cavity and root canal orifice were sealed with a temporary filling composed of zinc oxide‐eugenol cement and glass ionomer.

Four weeks after the initial procedures, Sample S5 was collected. The residual temporary material was removed with a sterile burr, and the root canal dressing was inactivated by applying 1 mL of sodium thiosulfate for 1 min, followed by irrigation with 2 mL of sterile saline. A sterile hand file (K 20) was then used to scrape the root canal wall, generating dentinal shavings. Bacterial sample S5 was collected from these shavings using the same technique as for Sample S3. Thereafter, the root canal was irrigated with sodium hypochlorite, EDTA, and saline, then dried with sterile paper points. Bleeding was induced from the periapical tissue and monitored for clot stability. A collagen scaffold and 2 mm of bioceramic material were placed, followed by glass ionomer and resin restoration [26].

A total of 123 bacterial samples were collected from the root canals of 41 participants. Successful treatment outcomes were observed in 68% of the RET cases, while 32% were classified as failures. The criteria for success and failure, along with their distribution, are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of bacterial samples according to RET outcomes.

| Total bacterial samples | Participants |

|---|---|

| N = 123 | N = 41 |

| Successful RET cases n = 28 (68%) | Failed RET cases n = 13 (32%) |

|

No clinical symptoms No radiographic signs of apical periodontitis Evidence of continued root development (in length and width and apex closure) |

Post‐operative self‐reported pain and Percussion pain Sinus tract Presence of periodontal disease with periodontal probings > 6 mm Abscess |

2.4. Molecular Based Microbiological Assessment at the Different Stages of the Regenerative Endodontic Procedure

2.4.1. DNA Isolation

The bacterial genomic DNA purification of root canal samples was performed as previously described [29] by using a bacterial genomic extraction kit (Sigma Aldrich, NA2120) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The paper points containing root canal samples were stored at −80°C and later used for DNA extraction in this study. Prior to the genomic DNA purification, the samples were thawed on ice, then vortexed for 30 s and transferred to new Eppendorf tubes, followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 14000 rpm at RT with the Micro 17R Microcentrifuge (Fisher Scientific; 75002440). The supernatant was removed from each tube. Each pellet was resuspended in 200 μL Lysis Solution containing 45 mg/mL Lysozyme (Merck, L6876‐5G) and 250 U/mL Mutanolysin (Merck, M9901‐10KU) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. RNase A (20 μL) was added for 2 min incubation at room temperature, followed by treatment with Proteinase K (20 μL) and Lysis Solution C (200 μL). These three mentioned components are supplied with the DNA purification kit. After 10 min incubation at 55°C, the ethanol (99.5%) was added, and then the contents of the tubes were applied to the column to separate the DNA. The column was washed twice and then 50 μL of the elution solution was applied directly onto the center of the column and incubated for 5 min at room temperature before the DNA was eluted by centrifugation. After the isolation, the concentration of purified DNA for each sample was measured by the Nanodrop instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 01‐058112) and stored in a freezer (−20°C) until usage.

2.4.2. Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reactions of Eubacteria, Actinomycetota, and E. faecalis

Real‐time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was employed to quantify the targeted DNA and assess the bacterial load of three distinct taxa, representing different hierarchical levels of bacterial taxonomy: a kingdom (Eubacteria), a phylum (Actinomycetota), and a species ( E. faecalis ) [1, 16, 30]. The choice to identify bacteria at the phylum level rather than the genus level was made due to ambiguities in taxonomic classification at the genus/species level. This approach provides a broader and clearer overview of the microbial community. The sequences of primers selected in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for qPCR at the different hierarchical levels of the bacterial taxonomy.

| Primer | Sequence 5′‐3′ | |

|---|---|---|

| Kingdom | ||

| 1 | Eubacteria‐forward | TTA AAC TCA AAG GAA TTG ACG G |

| 2 | Eubacteria‐reverse | CTC ACG ACA CGA GCT GAC GAC |

| Phylum | ||

| 3 | Actinomycetota‐forward | GGC TTG CGG TGG GTA CGG GC |

| 4 | Actinomycetota‐reverse | GGC TTT AAG GGA TTC GCT CCA CCT CAC |

| Species | ||

| 5 | Enterococcus faecalis ‐forward | CCG AGT GCT TGC ACT CAA TTG G |

| 6 | Enterococcus faecalis ‐reverse | CTC TTA TGC CAT GCG GCA TAA AC |

qPCR was performed in a reaction mixture that contained a total volume of 10 μL, including 5 μL Fast SYBR Green PCR Master Mix 2X (ThermoFisher Scientific, 4,385,612), 20 pmol of forward (0.25 μL) and reverse primer (0.25 μL), PCR grade water (2.5 μL) and 2 μL of bacterial genomic DNA extracted from the root canal samples using the QuantStudio 6 Pro RT‐qPCR System, 96‐well, 0.1 mL GeneAmp (ThermioFisher Scientific, A43160). A thermocycling program for RT‐qPCR was run at 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s, with an initial cycle of 95°C for 30 s. All amplifications and detections were carried out in a MicroAmp Fast Optical 96‐Well Reaction Plate, 0.1 mL (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 4346907) covered by MicroAmp Optical Adhesive Film (ThermoFisher Scientific, 4311971). All data were analyzed using the QuantiStudio Real‐Time PCR Software v 1.3.

To generate standard curves for qPCR, the method suggested by Byun et al. the [30] was employed. For specific enumeration of Eubacteria, Actinomycetota, or E. faecalis in clinical samples, the purified genomic DNA of Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum CCUG 9126T, Actinomyces naeslundii CCUG‐18310T, and E. faecalis CCUG19916T in the range 10 fg to 1 ng was used as a standard for determining the amount of the DNA of the corresponding number of bacterial cells. This was equivalent to 3 to 3 × 105 or 4 to 4 × 105 genome copies, based on the genome size data for F. nucleatum [31], A. naeslundii [32] and E. faecalis [33]. The amount of DNA was converted to the numbers of bacterial cells based on the genome size data. Calculation of bacterial cell numbers was performed by conversion of the amount of the DNA of the corresponding taxa determined by the RT‐qPCR to the theoretical genome equivalents. It assumes that the genome size and 16S rRNA gene copy number in bacterial strains used for the construction of standard curves were similar to the corresponding detected strains. The average genome size for the bacteria used for this study is estimated to be 2.7 Mb, so each bacterial cell contains approximately 2.9 fg of DNA. The RT‐qPCR obtained data were used to convert genomic DNA concentration into bacterial cell numbers.

2.4.3. Statistical Analysis

Linear calibration between log‐concentration of target genes and the quantification cycle (Cq) at which measured fluorescence in qPCR reaches some threshold after adjusting for background fluorescence was applied for the standard curve. The data obtained in the qPCR were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 10.0.0 (153) software package (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA). The results are expressed as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison tests were used for analysis of continuous variables. Categorical variables were analyzed by chi‐squared (and Fisher's exact) test. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

The recruited participants were referred to the Department of Endodontology at Eastman Institute, Public Dental Health Services in Stockholm, Sweden. The study population was comprised of children in the ages 6–13 years with one or more traumatized permanent incisors with immature root development with pulp necrosis, and/or apical periodontitis. When apical periodontitis was not present radiographically, in addition to a negative response to cold and electric sensibility tests, teeth were included only when clinical signs and symptoms of pulp necrosis were observed (swelling, sinus tract, self‐reported pain, and pain to percussion and palpation).

Most patients (80%) were between 6 and 11 years old, 64% of whom were male. The mean age distribution was 10.4 years for successful RET, and 9.5 years for failed RET. One or a combination of several clinical and radiographic signs and symptoms was detected pre‐operatively. Approximately 20% of the included teeth were subject to combination trauma to both hard and soft tissues. The types of hard tissue injuries were uncomplicated enamel and dentin fractures (75%) and complicated enamel and dentin fractures (10%). The types of soft tissue injuries were subluxations, lateral luxations, avulsions, and intrusions (35%).

The overall observation period for the treated teeth ranged from 1.19 years to 7.69 years (mean 3.98 years). The characteristics of the study population are depicted in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

The characteristics of the study population.

| Age in years, mean; (range) | 10.4 (6–13) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Males | 26 (64%) |

| Females | 15 (36%) |

| Pre‐operative clinical symptoms | |

| Pre‐operative pain | 9 (21.9%) |

| Pre‐operative sinus tract | 12 (29.3%) |

| Pre‐operative pathological probing > 6 mm | 4 (9.8%) |

| Pre‐operative abscess | 13 (31.7%) |

| Pre‐operative percussion pain | 13 (31.7%) |

| Pre‐operative PAI, mean; [CI] | 3.54 [3.229–3.85] |

| Pre‐operative RDS, mean; [CI] | 3.4 [3.209–3.59] |

| Trauma type | |

| Subluxation | 4 (9.8%) |

| Lateral luxation | 4 (9.8%) |

| Intrusion | 4 (9.8%) |

| Avulsion | 2 (5%) |

| Uncomplicated ED fracture | 31 (75.6%) |

| Complicated ED fracture | 4 (9.8%) |

| Combination trauma | 8 (19.5%) |

| Post‐operative PAI, mean, [CI] | 2.54 [2.1–2.978] |

| Post‐operative RDS mean, [CI] | 3.98 [3.777–4.128] |

| Follow up mean in years, mean; [range] | 3.98 [1.19–7.69] |

| Total number of cases | 41 |

3.2. Total Bacterial Load by qPCR and Its Impact on Regeneration Treatment Outcome

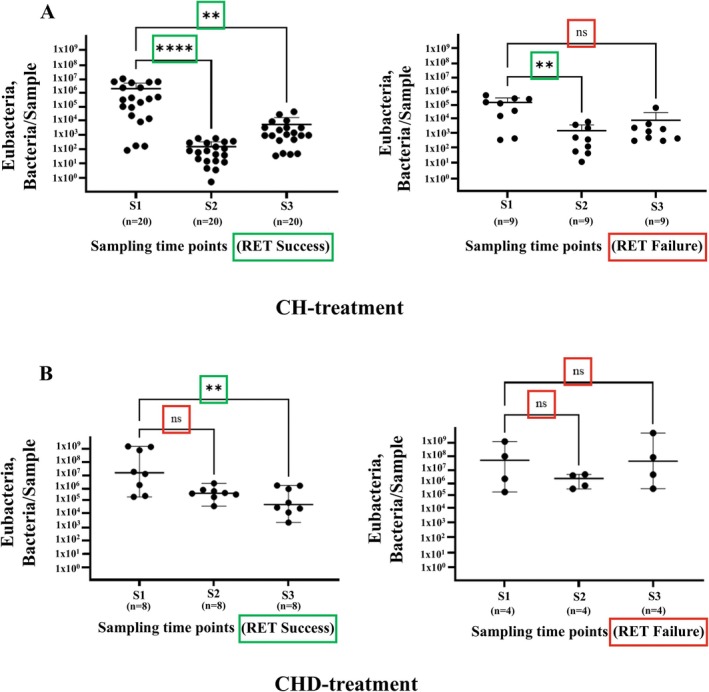

In the CH‐group with successful outcomes, statistically significant reductions in the total bacterial loads were observed both after root canal disinfection (S2) and after the application of the root canal dressing (S3) when compared to baseline levels at S1 (before disinfection) (Figure 2A). These findings were partially confirmed in the CHD‐group with successful outcomes, where statistically significant reductions in the total bacterial loads were observed after S3 but not after S2 (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

qPCR estimation of total loads of Eubacteria. Loads are shown at different time points (S1, S2, and S3) following (A) calcium hydroxide (CH) and (B) chlorhexidine (CHD) treatment. The samples were grouped based on the regenerative endodontic treatment (RET) outcome: Success (left panel) and failure (right panel). Bacterial loads are expressed as a number of bacterial cells per sample, converted from genomic DNA concentrations measured in nanograms per microliter(ng/μL). The figure is based on the number of samples for the CH‐subgroup: RET Success (n = 20) and RET Failure (n = 4); CHD‐subgroup: RET Success (n = 8) and RET Failure (n = 4). Each dot represents individual sample data, and the bars represent the mean value of S1, S2, or S3 grouped samples with SD. The data were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison tests. Statistically significant differences are marked as “**” p = 0.01; “ns” p > 0.05.

In the CH‐group with failed outcomes, a statistically significant decrease in the total bacterial load of Eubacteria was noted after root canal disinfection (S2), but no further reduction was observed after intracanal dressing (S3) (Figure 2A). Notably, in the CHD‐group with failed outcomes, bacterial loads remained unchanged across all sampling points, with no statistically significant reductions observed (p > 0.05) (Figure 2B).

3.3. Actinomycetota Load by qPCR and Its Impact on Regenerative Endodontic Treatment Outcome

Next, the results for the representatives of the phylum Actinomycetota were analyzed and are presented in Figure 3. Samples negative for the presence of Actinomycetota phylum were omitted from the diagrams. This occurred exclusively in the CH group, where, in the RET success group, the proportion of samples negative for the presence of Actinomycetota was 6 out of 20 in S1, 14 out of 20 in S2, and 11 out of 20 in S3. In the RET failure group, 5 out of 9 samples were negative for the presence of Actinomycetota at all sampling points (S1, S2, and S3).

FIGURE 3.

qPCR estimation of total loads of Actinomycetota. Loads are shown at different time points (S1, S2, and S3) following (A) calcium hydroxide (CH) and (B) chlorhexidine (CHD) treatment. The samples were grouped based on the outcome of regenerative endodontic treatment (RET): Success (left panel) and failure (right panel). The figure is based on number of samples for the CH‐subgroup: RET Success (n = 20) and RET Failure (n = 4); CHD‐subgroup: RET Success (n = 8) and RET Failure (n = 4). Bacterial loads are expressed as a number of bacterial cells per sample, converted from genomic DNA concentrations measured in nanograms per microliter (ng/μL). Each dot represents individual sample data, and the bars represent the mean value of S1, S2 or S3 with SD. Data were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison tests. Statistically significant differences are marked with “**” p = 0.01; “ns” p > 0.05.

A statistically significant decrease in Actinomycetota bacterial loads was observed between sampling time points S1 and S2 (p = 0.01) in the CH group. Nevertheless, no significant difference was found at S3 (ns, p > 0.05), indicating a potential reduction in bacterial load immediately after root canal disinfection, but not after intracanal medication. For both the CH and CHD failure groups, no significant differences were observed across the sampling time points (S1, S2, and S3) (Figure 3A,B). No significant changes in Actinomycetota bacterial load were observed throughout the treatment, regardless of the treatment outcome, in patients treated with CHD (Figure 3B).

Further statistical analyses for the Actinomycetota phylum were conducted using the chi‐squared test and Fisher's exact test to determine whether the presence of Actinomycetota statistically influenced the odds for treatment failure in the CH subgroup (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Odds ratios for failure of RET in the presence of Actinomycetota in the CH subgroup. RET outcome ratio in Actinomycetota positive versus Actinomycetota negative samples in the subgroup of CH‐treated root canals. The data are presented as the total number of analyzed samples. Differences between the ratio of successful and failed RET was estimated by chi‐squared test, and statistical significance was estimated by Fisher's exact test. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The 95% CI = 0.0783–1.962 for OR at S1 sampling. The 95% CI = 0.4373–8.251 for OR at S2 sampling. The 95% CI = 0.2416–5.346 for OR at S3 sampling.

No statistical significance for the odds ratio of successful and failed RET outcomes in Actinomycetota positive versus negative samples from the CH‐treated subgroup was shown. The odds ratio could not be assessed for Actinomycetota in the CHD group because this phylum was present in all samples, leaving no variability in its distribution.

3.4. Enterococcus fecalis Load by qPCR and Its Impact on Treatment Outcome

E. faecalis bacterial loads, as quantified by qPCR, did not differ significantly between patients with successful and failed RET outcomes (Figure 5). After root canal dressings (S3), higher numbers of E. faecalis cells were observed in the failed CHD cases (Figure 5B). Moreover, most samples exhibited a very low number of E. faecalis cells.

FIGURE 5.

qPCR estimation of total loads of E. faecalis . Loads are shown at different time points (S1, S2, and S3) following (A) calcium hydroxide (CH) and (B) chlorhexidine (CHD) treatment. The samples were grouped based on the outcome of regenerative endodontic treatment (RET): Success (left panel) and failure (right panel). Bacterial loads are expressed as a number of bacterial cells per sample, converted from genomic DNA concentrations measured in nanograms per microliter (ng/μL). Each dot represents individual sample data, and the bars represent the mean value of S1, S2, or S3 with SD. Data were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison tests. Statistically significant differences are marked with “**” p = 0.01; “ns” p > 0.05.

Further statistical analyses were performed to estimate if the presence of E. faecalis statistically influenced the odds for treatment failure as observed in Figure 6A,B.

FIGURE 6.

Odds ratios for failure of RET in the presence of E. faecalis in the CH subgroup (A) and in the CHD subgroup (B). RET outcome ratio in E. faecalis positive versus E. faecalis negative samples according to the intracanal medication. The data are presented as percentages of the total number of analyzed samples. The differences between the ratio of successful versus failed RET was estimated by chi‐square test (except those samplings when at least one event frequency was zero), and statistical significance was estimated by Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. In the CH‐subgroup (A): the 95% CI = 1.166–116.8 for OR at S3 sampling. In the CHD‐subgroup (B): the 95% CI = 0.053–11.16 for OR at S1 sampling; the 95% CI = 17.59–14.74 for OR at S2 sampling.

At S1, the E. faecalis was more prevalent in the success group compared to the failure group, while all E. faecalis ‐negative cases were observed exclusively in the success group. The absence of E. faecalis ‐negative cases in the failure group made the odds ratio (OR) calculations impossible to perform. Similarly, at S2, the presence of E. faecalis was equal in both groups, and negative cases were only present in the success group, again precluding OR analysis due to a lack of variability. At S3, there were more E. faecalis ‐positive cases in the failure group than in the success group, while E. faecalis ‐negative samples were observed predominantly in the success group except for one case from the failure group that exhibited a very low number of cells. At this point, an OR of 9.778 (p = 0.0432) indicated a statistically significant association between the presence of E. faecalis and failed RET outcomes (Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of the disinfection efficacy of calcium hydroxide and chlorhexidine gluconate in successful versus failed RET outcomes. Disinfection efficacy in the successful versus failed RET outcomes, calcium hydroxide and chlorhexidine subgroups. Each dot represents the individual value of disinfection efficacy. The boxes represent the range of standard deviation, the horizontal lines in the boxes represent the median value per group, and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values. The data set was analysed using Šídák's multiple comparisons test. Statistically significant difference was accepted at the level < 0.05. Disinfection efficacy was calculated using the formula Efficacy = Log N0/N, where N0 represents the bacterial cell number based on concentration of DNA/sample before root canal debridement at S1 and N represents the bacterial cell number based on concentration of DNA/sample after root canal disinfection at S3. “ns” – not significant; “RET success” – successful cases of pulp regenerative treatment; “RET failure” –failed cases of pulp regenerative treatment.

In the CHD group, E. faecalis presence did not show a statistically significant association with RET outcomes across any sampling points (Figure 7B).

No statistically significant differences could be found in the disinfection efficacy between successful and failed outcomes. However, the disinfection efficacy of both root canal dressings was lower in the failed RET cases (Figure 7).

4. Discussion

RET aims to promote root maturation in necrotic immature teeth, with effective microbial control being essential for clinical success. This study assessed the antibacterial efficacy of CH and 2% CHD as intracanal medicaments and their influence on bacterial loads and RET outcomes. Both CH and CHD demonstrated significant antibacterial activity, with greater reductions in bacterial loads correlating with successful treatment outcomes. The presence of E. faecalis was associated with failed RET, reinforcing the notion that this species may have a potential impact on treatment prognosis.

These findings highlight the importance of effective microbial disinfection in RET and underscore the need for further research.

4.1. Microbiological Analyses Performed on Kingdom Level (Eubacteria)

The main finding of this study was that total bacterial loads were significantly reduced in successful outcomes compared to failed ones. In the CH‐group, Eubacteria loads were significantly reduced after both root canal disinfection (S2) and intracanal dressing (S3) in successful cases, while failed cases only showed a reduction after root canal disinfection (S2). In the CHD‐group, significant reductions occurred only after intracanal dressing (S3) in successful cases, with no significant changes in failed cases. The findings of this study partially align with those from our previous cultivation‐based study [26]. There, in both successful and failed cases, decreases in total CFU/sample were observed at S3. However, at S3, a significant increase in CFU/sample and taxa/sample was observed in the failed group of the CH group, whereas no such increase was seen in the successful group.

A possible explanation for this finding might be leakage. It is known that traumatic dental injuries might cause bacterial invasion through the injured periodontal tissues and through cracks or fractures [10]. This, in our opinion, might be a possible way for new microbial invasion after endodontic root canal medication. As traumatic dental injuries tend to occur at young ages, the affected teeth are immature with wide dentinal tubules facilitating bacterial invasion of both more tubules per unit area and deeper tubuli penetration compared to mature teeth [34].

Another possible reason for the increases in the total loads of bacterial DNA at S3 might be persisting bacterial biofilm. Instead of following the ESE treatment protocol, which recommends no or minimal root canal instrumentation to prevent further weakening of immature teeth, we utilized ultrasonic activation of the irrigating solutions while maintaining minimal or no mechanical instrumentation. This approach may have allowed bacterial regrowth from the untouched biofilm, leading to the observed increase in DNA. These findings are of key importance for the treatment outcomes. The persistence of microorganisms inside the root canal after treatment is a contributing factor for non‐healing apical periodontitis considered as endodontic failure [35].

4.2. Microbiological Analyses Performed on Phylum Level (Actinomycetota)

Interestingly, the findings in this study regarding the total bacterial load of Actinomycetota phylum did not correlate with the outcomes of the performed RET because the decreases in total DNA were non‐significant after both root canal dressings (S3) in the successful and failed outcomes. However, we observed that the total bacterial load of this phylum decreased significantly after root canal disinfection (S2) only in the successful cases from the CH group. Although previous studies have indicated an association between species from this phylum and endodontic failure [36], no such correlation was observed in the present study. A possible explanation is that Actinomycetota phyla are opportunistic pathogens of the oral cavity of humans and other mammals [37]. These are normally present in the supragingival plaque and are capable of invading periodontal tissues, being the most common cause of actinomycosis, presenting clinically with chronic oral abscesses associated with tissue fibrosis and draining sinuses [38]. Studies show that this species enables initiation of dental biofilm which provides resistance to endodontic disinfecting procedures [39]. Moreover, it was found that A. israelii and A. naeslundii are most involved in symptomatic post‐treatment endodontic failures [16]. Notably, we showed that the odds ratio for failure in the presence of Actinomycetota could not be assessed because this phylum was present in all samples treated with CHD. A possible reason for this result is that the Actinomycetota phylum includes many different species which might play different underexplored roles, not necessarily pathogenic [40].

Notably, in our previous study, we found the total load of Actinomycetota in the CH subgroup was significantly higher in successful outcomes, whereas in the CHD subgroup, the values were significantly higher in the failed outcomes [26]. A possible explanation for those ambiguous findings could be that the antibacterial mechanisms of action of the two root canal dressings differ. Hydroxyl ions in CH may damage the DNA, which would influence the amount/quality of DNA that could be extracted from the samples, therefore impacting the real‐time PCR results [41]. The effect of CH and CHD on the persistence of bacterial DNA in infected dentinal tubules has been studied by molecular techniques. Nevertheless, the researchers have come to contradictory findings. Some authors state that CHD is more effective in removing DNA than CH [42]. In agreement with this, it has been stated that CHD has superior effectiveness in failed root canal treatments, especially against E. faecalis [43]. Inconsistent results are exhibited regarding the antibacterial effectiveness of CH as an intracanal medicament. It has been shown that dentine has a buffering capacity, which might reduce the antibacterial effect of CH [44]. On the other hand, chlorhexidine exhibits prolonged antimicrobial activity as it adheres to dentin [45]. The medicament decreases the bacterial load unselectively, which might suppress the commensal microbiota, posing risks for increases in bacterial loads of other strains, for example, pathogenic periodontitis related taxa [46].

4.3. Microbiological Analyses on Species Level ( E. faecalis )

The results on species level were difficult to analyze due to the low levels of cell numbers. Indication of E. faecalis having higher cell numbers in the successful CHD cases before treatment (S1) and in the failed CHD cases after root canal dressings (S3), (Figure 5A,B) was observed. No statistically significant difference in the cell number of the E. faecalis between the successful and failed outcomes could be shown due to small sample sizes. The absence of variability in some categories (e.g., S3, where no E. faecalis ‐negative samples were detected in the RET failure group) may limit broader generalization of the findings.

Interestingly, after calculating the odds for failure in the presence of E. faecalis after completed treatment, our findings might suggest that the risk for RET failure is 10 times higher compared to when this species is absent after the treatment. This might highlight the potential role of E. faecalis as a negative prognostic factor for treatment outcome.

4.4. The Disinfection Efficacy of Calcium Hydroxide and Chlorhexidine Gluconate

It was shown that there were no statistical differences in CH and CHD efficacy. Although not statistically significant, the results showed that the disinfection efficacy was lower in the failed cases in both CH and CHD subgroups. These results are supported in our previous study [26] showing that after root canal dressing, microbiota persisted in both successful and failed outcomes, but bacterial loads increased only in the failed cases.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

The present study utilized qPCR techniques, which offer several advantages, including rapid detection and quantification of DNA from pathogens without the need for cultivation [47]. Even though qPCR has high sensitivity, specificity, and the ability to detect DNA, it is not possible to determine if that DNA comes from live or dead microorganisms. In fact, it was found that bacterial DNA is detectable 6–24 months after root canal treatment [48, 49]. In this context, as the present study did not employ cultivation, it is not defined if the DNA originated from living microbiota. Thus, even if the results were confirmed by our previous study using cultivation, the method might be considered a limitation. It has been discussed that remnants from dead bacterial species after completed antimicrobial root canal treatment might affect the outcomes of RET negatively. The role of live bacteria is poorly understood. Some studies have shown that live bacteria might stimulate the inflammatory response of SCAPs, affecting the success of RET, while DNA from dead bacteria might not have this effect [19].

This study focused specifically on the root canal microbiota of traumatized immature necrotic teeth. Nevertheless, the methods used for collecting the samples cannot distinguish the exact sampling location. It is known that immature teeth have wide root canals and open apices, which might lead to sampling from different regions of the root canals. It has been discussed in methodological studies that the bacterial microbiome in the apical part of the root canal might differ compared to that of the coronal [50].

The analyses on a phylum level targeted the whole Actinomycetota phylum, which might be considered a limitation. A more specific analysis of Actinomyces israelii , reported to be the most commonly cultured species of Actinomyces from periapical infections, could have been applied.

Another limitation is difficulties in designing primers for the 16S rRNA gene for Actinomyces species, and there might be a need to target another gene of these species.

However, targeting A. israelii at the species level by qPCR could risk further reducing detection sensitivity, especially given the inherent challenges of recovering sufficient bacterial DNA from biofilm‐limited samples. By focusing on the phylum level, the analysis accounted for broader microbial diversity, potentially mitigating the risk of underestimating bacterial contributions to the observed outcomes.

Another possible limitation is that the samples were collected from immature incisors with wide root canals, which might pose a risk of only entrapping species from a niche not representative for the whole root canal [51].

A limitation of this study was the unequal group sizes, despite blocked randomization, which may have impacted the statistical power to detect significant differences. The dropout rate in the CHD subgroup was mainly due to technical issues, such as bacterial contamination and transport delays. Additionally, patient recruitment challenges during the COVID‐19 pandemic contributed to the smaller sample size. Future studies with larger, more balanced cohorts are needed to validate these findings and further investigate the microbiological and clinical outcomes of different intracanal medicaments in regenerative endodontics.

Additional matter to discuss is the current recommendations on the concentrations of sodium hypochlorite in regenerative endodontics. The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) and the European Society of Endodontology (ESE) recommend the use of sodium hypochlorite in concentrations of 1.5%–3%. Nevertheless, we used a buffered solution of 0.5% NaOCl (Dakin's solution). In Swedish dental practice, there is a recommendation from the National Board of Health and Welfare to use low concentrations of irrigating solutions (0.5 buffered NaOCl or 1.0% unbuffered NaOCl) during endodontic treatment. The scientific evidence behind this strategy is that the buffering of the NaOCl (Dakin's solution) provides a high pH with good antimicrobial and biofilm efficiency and a low incidence of postoperative concentration‐associated symptoms [52]. Furthermore, low concentrations of irrigation solutions have been proposed due to concerns about the potential cytotoxicity of high concentrations of NaOCl solutions on stem cells of the apical papilla [53, 54].

4.6. Future Research Questions

Two future research questions were identified. The first question regards single‐visit regenerative endodontic treatment. Up to date, there is an insufficient body of scientific evidence for the efficacy of single‐visit regenerative endodontic treatment. It is difficult to rely on the results of the articles available on this subject as these are case reports/series not including controls. Also, these articles do not provide any information about the microbiological outcomes of this new treatment modality, such as evaluation of the antimicrobial efficacy of different irrigating medicaments. Although we observed reductions in bacterial loads after root canal disinfection in both CH and CHD subgroups and treatment outcomes, further bacterial reductions occurred exclusively in the successful cases after intracanal dressing. Although not significant, it is important to emphasize that the presence of E. faecalis after intracanal dressing was associated with failed RET. This finding should be investigated further in studies with a bigger sample size ensuring that statistical significance would not be a concern.

The second research question regards the impact of traumatic dental injuries on the disinfection efficacy in RET. It is reported in the literature that the trauma type can have an impact on continued root development. Severe injuries to the periodontal region, such as avulsion or intrusion, might cause interruption of the blood supply and injury to the dental papilla and Hertwig's epithelial root sheath. In this situation, the continued viability and integrity of stem cells might be compromised, leaving the root canal walls thin and with loss of normal root morphology [55]. Moreover, it has been shown that the clinical and radiographical outcomes of RET in non‐trauma cases have a better prognosis compared to trauma cases [56]. Additional bacterial infection invading the root canal via cracks or via injuries in the periodontal ligament might jeopardize pulp vitality causing not only ceased root maturation but also providing favorable conditions for the bacterial biofilm to infiltrate the large tubules in young immature teeth [57]. A recent study shows that the root canal microflora of traumatized teeth is highly diverse and differs significantly from root canal infections not caused by trauma [58].

Nevertheless, there is still a knowledge gap regarding the question of whether trauma type might influence the disinfection efficacy in RET. Thus, future research needs to elucidate how traumatic dental injuries influence the microbiological outcomes of regenerative endodontic treatment.

5. Conclusions

Both CH and CHD effectively reduced bacterial loads, with greater reductions associated with successful outcomes, suggesting that microbial load reduction may serve as a prognostic factor for successful outcomes of RET. However, no significant differences in disinfection efficacy between the intracanal medicaments were observed. The presence of E. faecalis was associated with treatment failure, indicating its potential role in failed outcomes of RET. These findings emphasize the critical importance of thorough bacterial reduction for the success of RET.

Author Contributions

A.W.: conceptualization; data curation; investigation; project administration; software; writing the original draft preparation and reviewing. O.R.: laboratory analyses, statistical analyses and interpretation of the results; methodology; writing; reviewing and editing. P.C.: laboratory analyses, statistical analyses and interpretation of the results. M.B.: conceptualization; methodology; formal analysis; funding acquisition; supervision; validation; writing, reviewing, and editing. G.T.: conceptualization; methodology; funding acquisition; supervision; reviewing, and editing. N.R.V.: conceptualization, data curation; validation, methodology, funding acquisition, writing, reviewing and editing.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was obtained by the Regional Ethical Review Board at Umeå University, Sweden (Ref: 2016/520‐31), by the Stockholm Central Ethical Board (Ref: 2018/692‐31), and by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Ref: 2022‐05715‐02).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Yulia Shavva, Rebecca Ebata, and Sara Abbas for their contributions to the experimental work undertaken in this study.

Funding: This work was supported by Region of Västerbotten (Sweden) via TUA under grant number RV‐977100 and RV‐70040; ALF (RV‐966705) and the Kempe Foundation (JCSMK23‐0158).

Alina Wikström and Olena Rakhimova Shared first authorship.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. Nagata J. Y., Soares A. J., Souza‐Filho F. J., et al., “Microbial Evaluation of Traumatized Teeth Treated With Triple Antibiotic Paste or Calcium Hydroxide With 2% Chlorhexidine Gel in Pulp Revascularization,” Journal of Endodontia 40, no. 6 (2014): 778–783, 10.1016/j.joen.2014.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banchs F. and Trope M., “Revascularization of Immature Permanent Teeth With Apical Periodontitis: New Treatment Protocol?,” Journal of Endodontia 30 (2004): 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hargreaves K. M., Diogenes A., and Teixeira F. B., “Treatment Options: Biological Basis of Regenerative Endodontic Procedures,” Pediatric Dentistry 35 (2013): 129–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu Q., Gao Y., and He J., “Stem Cells From the Apical Papilla (SCAPs): Past, Present, Prospects, and Challenges,” Biomedicine 11 (2023): 2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chrepa V., Pitcher B., Henry M. A., and Diogenes A., “Survival of the Apical Papilla and Its Resident Stem Cells in a Case of Advanced Pulpal Necrosis and Apical Periodontitis,” Journal of Endodontia 43 (2017): 561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cvek M., “Prognosis of Luxated Non‐Vital Maxillary Incisors Treated With Calcium Hydroxide and Filled With Gutta‐Percha. A Retrospective Clinical Study,” Endodontics & Dental Traumatology 8 (1992): 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Twati W. A., Wood D. J., Liskiewicz T. W., Willmott N. S., and Duggal M. S., “An Evaluation of the Effect of Non‐Setting Calcium Hydroxide on Human Dentine: A Pilot Study,” European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry: Official Journal of the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry 10 (2009): 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bose R., Nummikoski P., and Hargreaves K., “A Retrospective Evaluation of Radiographic Outcomes in Immature Teeth With Necrotic Root Canal Systems Treated With Regenerative Endodontic Procedures,” Journal of Endodontia 35 (2009): 1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Al‐Qudah A., Almomani M., Hassoneh L., and Awawdeh L., “Outcome of Regenerative Endodontic Procedures in Nonvital Immature Permanent Teeth Using 2 Intracanal Medications: A Prospective Randomized Clinical Study,” Journal of Endodontia 49 (2023): 776–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fouad A. F., “Microbiological Aspects of Traumatic Injuries,” Journal of Endodontia 45 (2019): 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galler K. M., Krastl G., Simon S., et al., “European Society of Endodontology Position Statement: Revitalization Procedures,” International Endodontic Journal 49 (2016): 717–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin L. M., Shimizu E., Gibbs J. L., Loghin S., and Ricucci D., “Histologic and Histobacteriologic Observations of Failed Revascularization/Revitalization Therapy: A Case Report,” Journal of Endodontia 40 (2014): 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Siqueira J. F. and Rocas I. N., “Diversity of Endodontic Microbiota Revisited,” Journal of Dental Research 88 (2009): 969–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fouad A. F., Diogenes A. R., Torabinejad M., and Hargreaves K. M., “Microbiome Changes During Regenerative Endodontic Treatment Using Different Methods of Disinfection,” Journal of Endodontia 48 (2022): 1273–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Verma P., Nosrat A., Kim J. R., et al., “Effect of Residual Bacteria on the Outcome of Pulp Regeneration in Vivo,” Journal of Dental Research 96 (2017): 100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xia T. and Baumgartner J. C., “Occurrence of Actinomyces in Infections of Endodontic Origin,” Journal of Endodontia 29 (2003): 549–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. J. F. Siqueira, Jr. , Rôças I. N., Souto R., Uzeda M., and Colombo A. P., “Microbiological Evaluation of Acute Periradicular Abscesses by DNA‐DNA Hybridization,” Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics 92 (2001): 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siqueira J. F., Rôças I. N., Souto R., de Uzeda M., and Colombo A. P., “Actinomyces Species, Streptococci, and Enterococcus Faecalis in Primary Root Canal Infections,” Journal of Endodontia 28 (2002): 168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zymovets V., Rakhimova O., Wadelius P., et al., “Exploring the Impact of Oral Bacteria Remnants on Stem Cells From the Apical Papilla: Mineralization Potential and Inflammatory Response,” Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 13 (2023): 1257433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kontakiotis E. G., Filippatos C. G., Tzanetakis G. N., and Agrafioti A., “Regenerative Endodontic Therapy: A Data Analysis of Clinical Protocols,” Journal of Endodontia 41 (2015): 146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sato I., Ando‐Kurihara N., Kota K., Iwaku M., and Hoshino E., “Sterilization of Infected Root‐Canal Dentine by Topical Application of a Mixture of Ciprofloxacin, Metronidazole and Minocycline In Situ,” International Endodontic Journal 29 (1996): 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruparel N. B., Teixeira F. B., Ferraz C. C., and Diogenes A., “Direct Effect of Intracanal Medicaments on Survival of Stem Cells of the Apical Papilla,” Journal of Endodontia 38 (2012): 1372–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Althumairy R. I., Teixeira F. B., and Diogenes A., “Effect of Dentin Conditioning With Intracanal Medicaments on Survival of Stem Cells of Apical Papilla,” Journal of Endodontia 40 (2014): 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. AAE , “Clinical Considerations for a Regenerative Procedure, 2016”.

- 25. Soares A. D. J., Lins F. F., Nagata J. Y., et al., “Pulp Revascularization After Root Canal Decontamination With Calcium Hydroxide and 2% Chlorhexidine Gel,” Journal of Endodontia 39, no. 3 (2013): 417–420, 10.1016/j.joen.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wikström A., Romani Vestman N., Rakhimova O., Lazaro Gimeno D., Tsilingaridis G., and Brundin M., “Microbiological Assessment of Success and Failure in Pulp Revitalization: A Randomized Clinical Trial Using Calcium Hydroxide and Chlorhexidine Gluconate in Traumatized Immature Necrotic Teeth,” Journal of Oral Microbiology 16 (2024): 2343518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagendrababu V., Murray P. E., Ordinola‐Zapata R., et al., “PRILE 2021 Guidelines for Reporting Laboratory Studies in Endodontology: A Consensus‐Based Development,” International Endodontic Journal 54 (2021): 1482–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wikström A., Brundin M., Romani Vestman N., Rakhimova O., and Tsilingaridis G., “Endodontic Pulp Revitalization in Traumatized Necrotic Immature Permanent Incisors: Early Failures and Long‐Term Outcomes‐A Longitudinal Cohort Study,” International Endodontic Journal 55 (2022): 630–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vestman N. R., Timby N., Holgerson P. L., et al., “Characterization and In Vitro Properties of Oral Lactobacilli in Breastfed Infants,” BMC Microbiology 13 (2013): 193, 10.1186/1471-2180-13-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Byun R., Nadkarni M. A., Chhour K.‐L., Martin F. E., Jacques N. A., and Hunter N., “Quantitative Analysis of Diverse Lactobacillus Species Present in Advanced Dental Caries,” Journal of Clinical Microbiology 42 (2004): 3128–3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kapatral V., Anderson I., Ivanova N., et al., “Genome Sequence and Analysis of the Oral Bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum Strain,” Journal of Bacteriology 184 (2002): 2005–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mashimo C., Yamane K., Yamanaka T., et al., “Genome Sequence of Actinomyces naeslundii Strain ATCC 27039, Isolated From an Abdominal Wound Abscess,” Genome Announcements 4, no. 6 (2016): e01443‐16, 10.1128/genomeA.01443-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Minogue T. D., Daligault H. E., Davenport K. W., et al., “Complete Genome Assembly of Enterococcus Faecalis 29212, a Laboratory Reference Strain,” Genome Announcements 2 (2014): 968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kakoli P., Nandakumar R., Romberg E., Arola D., and Fouad A. F., “The Effect of Age on Bacterial Penetration of Radicular Dentin,” Journal of Endodontia 35 (2009): 78–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sjogren U., Figdor D., Persson S., and Sundqvist G., “Influence of Infection at the Time of Root Filling on the Outcome of Endodontic Treatment of Teeth With Apical Periodontitis,” International Endodontic Journal 30 (1997): 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dioguardi M., Quarta C., Alovisi M., et al., “Microbial Association With Genus Actinomyces in Primary and Secondary Endodontic Lesions, Review,” Antibiotics (Basel) 9, no. 8 (2020): 433, 10.3390/antibiotics9080433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Madigan M. and Martinko J., Brock Biology of Micro‐Organisms (Prenticehall, inc, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 38. Åberg C. H., Kelk P., and Johansson A., “ Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans : Virulence of Its Leukotoxin and Association With Aggressive Periodontitis,” Virulence 6 (2015): 188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dige I., Raarup M. K., Nyengaard J. R., Kilian M., and Nyvad B., “ Actinomyces naeslundii In Initial Dental Biofilm Formation,” Microbiology (Reading) 155 (2009): 2116–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hourigan D., de Miceli Farias F., O'Connor P. M., Hill C., and Ross R., “Discovery and Synthesis of Leaderless Bacteriocins From the Actinomycetota,” Journal of Bacteriology 206 (2024): 0029824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. J. F. Siqueira, Jr. and Lopes H. P., “Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Activity of Calcium Hydroxide: A Critical Review,” International Endodontic Journal 32 (1999): 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cook J., Nandakumar R., and Fouad A. F., “Molecular‐ and Culture‐Based Comparison of the Effects of Antimicrobial Agents on Bacterial Survival in Infected Dentinal Tubules,” Journal of Endodontia 33 (2007): 690–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ballal V., Kundabala M., Acharya S., and Ballal M., “Antimicrobial Action of Calcium Hydroxide, Chlorhexidine and Their Combination on Endodontic Pathogens,” Australian Dental Journal 52 (2007): 118–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mohammadi Z., Shalavi S., and Yazdizadeh M., “Antimicrobial Activity of Calcium Hydroxide in Endodontics: A Review,” Chonnam Medical Journal 48 (2012): 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haapasalo M., Qian W., Portenier I., et al., “Effects of Dentin on the Antimicrobial Properties of Endodontic Medicaments,” Journal of Endodontia 33 (2007): 917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chatzigiannidou I., Teughels W., van de Wiele T., and Boon N., “Oral Biofilms Exposure to Chlorhexidine Results in Altered Microbial Composition and Metabolic Profile,” npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 6 (2020): 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kubista M., Andrade J. M., Bengtsson M., et al., “The Real‐Time Polymerase Chain Reaction,” Molecular Aspects of Medicine 27, no. 2–3 (2006): 95–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brundin M., Figdor D., Roth C., Davies J. K., Sundqvist G., and Sjögren U., “Persistence of Dead‐Cell Bacterial DNA in Ex Vivo Root Canals and Influence of Nucleases on DNA Decay In Vitro,” Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics 110 (2010): 789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brundin M., Figdor D., Johansson A., and Sjögren U., “Preservation of Bacterial DNA by Human Dentin,” Journal of Endodontics 40 (2014): 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rôças I. N., Alves F. R. F., Santos A. L., Rosado A. S., and J. F. Siqueira, Jr. , “Apical Root Canal Microbiota as Determined by Reverse‐Capture Checkerboard Analysis of Cryogenically Ground Root Samples From Teeth With Apical Periodontitis,” Journal of Endodontia 36 (2010): 1617–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. de Castro Kruly P., Alenezi H., Manogue M., et al., “Residual Bacteriome After Chemomechanical Preparation of Root Canals in Primary and Secondary Infections,” Journal of Endodontia 48, no. 7 (2022): 855–863, 10.1016/j.joen.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rosenfeld E. F., James G. A., and Burch B. S., “Vital Pulp Tissue Response to Sodium Hypochlorite,” Journal of Endodontia 4 (1978): 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Martin D. E., de Almeida J. F., Henry M. A., et al., “Concentration‐Dependent Effect of Sodium Hypochlorite on Stem Cells of Apical Papilla Survival and Differentiation,” Journal of Endodontia 40 (2014): 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Trevino E. G., Patwardhan A. N., Henry M. A., et al., “Effect of Irrigants on the Survival of Human Stem Cells of the Apical Papilla in a Platelet‐Rich Plasma Scaffold in Human Root Tips,” Journal of Endodontia 37, no. 8 (2011): 1109–1115, 10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu C. Y. and Abbott P. V., “Responses of the Pulp, Periradicular and Soft Tissues Following Trauma to the Permanent Teeth,” Australian Dental Journal 61 (2016): 39–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hu X., Wang Q., Ma C., Li Q., Zhao C., and Xiang K., “Is Etiology a Key Factor for Regenerative Endodontic Treatment Outcomes?,” Journal of Endodontia 49 (2023): 953–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fouad A., “The Microbial Challenge to Pulp Regeneration,” Advances in Dental Research 23 (2011): 285–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Manoharan L., “New Insights Into the Microbial Profiles of Infected Root Canals in Traumatized Teeth,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 9 (2020): 3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.