Abstract

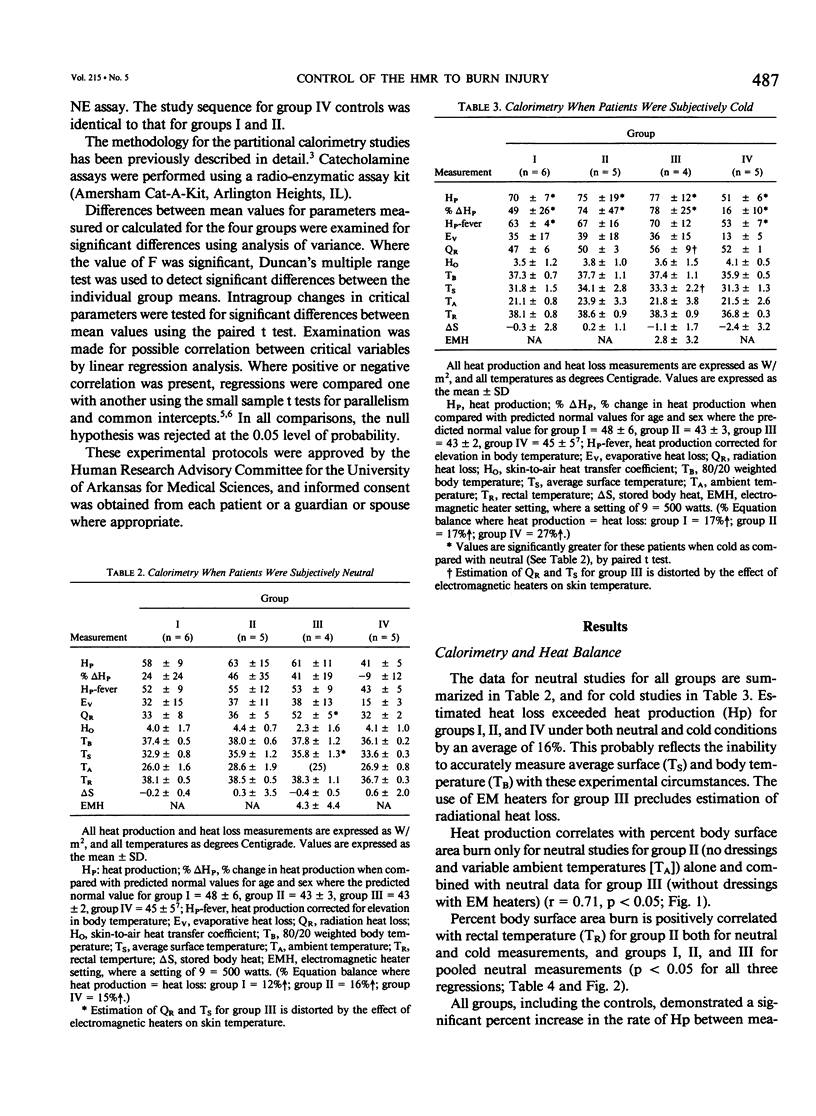

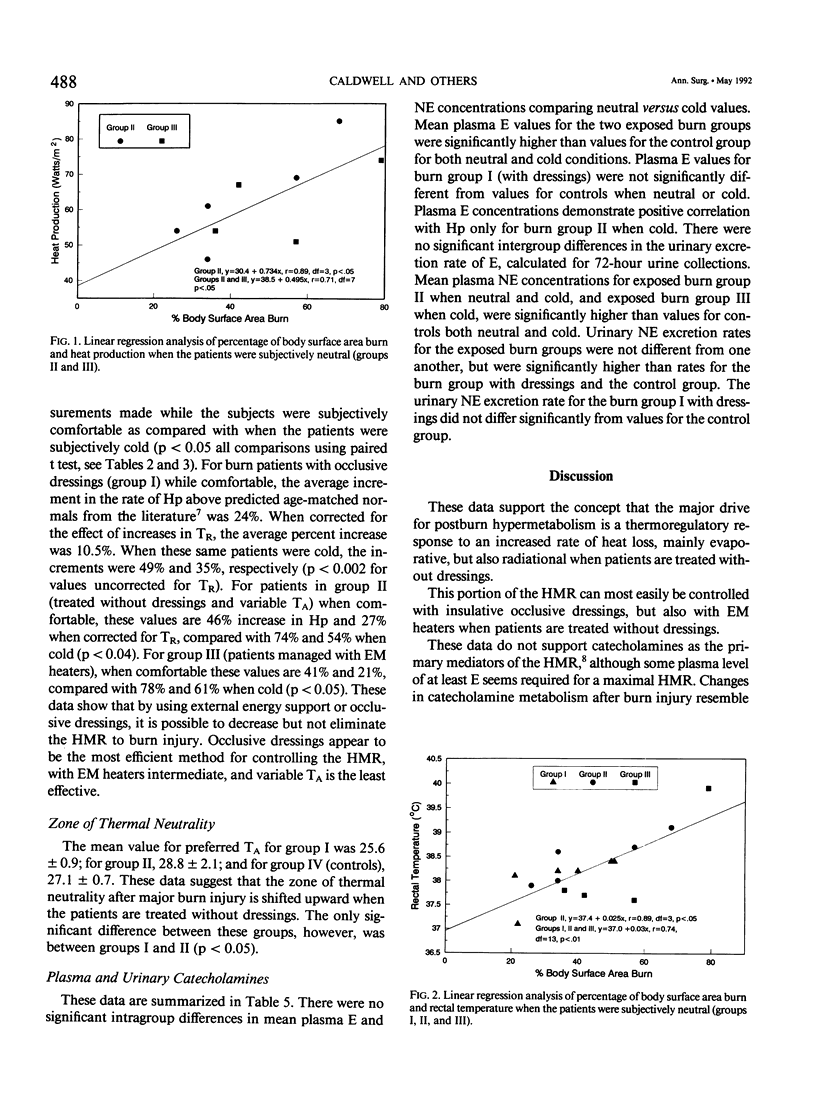

This study was performed to establish the relative efficiency of occlusive dressings and variable ambient temperature (group I) versus no dressings and variable ambient temperature (group II) versus no dressings and electromagnetic heaters (group III) for controlling the postburn hypermetabolic response. Fifteen burn patients and five normal controls (group IV) were studied when subjectively comfortable using partitional calorimetry, after which each patient was cold stressed by sequentially decreasing external energy support, and repeating calorimetry studies and serial plasma catecholamine assays. The percentage increase in heat production above predicted normal values was significantly increased for all groups when cold (C) versus neutral (N) (group I: [N] 24 +/- 24 versus [C] 49 +/- 25%; group II: [N] 46 +/- 35 versus [C] 74 +/- 47%; group III: [N] 21 +/- 20 versus [C] 78 +/- 25%; group IV: [N] -9 +/- 12 versus [C] 16 +/- 10%, p less than 0.05 all comparisons). Plasma catecholamine values did not increase significantly when patients were subjectively cold. These studies do not support the role of catecholamines as the primary mediator in the cause of the postburn hypermetabolic response. Using the patients' subjective comfort status as a guide for external energy support, it is possible to greatly reduce but not to eliminate the hypermetabolic response to burn injury.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arturson M. G. Metabolic changes following thermal injury. World J Surg. 1978 Mar;2(2):203–214. doi: 10.1007/BF01553553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein E., Chioléro R. L., Jéquier E., Dayer P., Krupp S., Schutz Y. Effects of beta-blockade on energy metabolism following burns. Burns. 1990 Aug;16(4):259–264. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(90)90136-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COPE O., NARDI G. L., QUIJANO M., ROVIT R. L., STANBURY J. B., WIGHT A. Metabolic rate and thyroid function following acute thermal trauma in man. Ann Surg. 1953 Feb;137(2):165–174. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195302000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell F. T., Jr, Bowser B. H., Crabtree J. H. The effect of occlusive dressings on the energy metabolism of severely burned children. Ann Surg. 1981 May;193(5):579–591. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198105000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell F. T., Jr Energy metabolism following thermal burns. Arch Surg. 1976 Feb;111(2):181–185. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1976.01360200087017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance W. T., Nelson J. L., Foley-Nelson T., Kim M. W., Fischer J. E. The relationship of burn-induced hypermetabolism to central and peripheral catecholamines. J Trauma. 1989 Mar;29(3):306–312. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitch E. A. Intestinal permeability is increased in burn patients shortly after injury. Surgery. 1990 Apr;107(4):411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagge A. P., Burton A. C., Bazett H. C. A PRACTICAL SYSTEM OF UNITS FOR THE DESCRIPTION OF THE HEAT EXCHANGE OF MAN WITH HIS ENVIRONMENT. Science. 1941 Nov 7;94(2445):428–430. doi: 10.1126/science.94.2445.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Dickerson C., Chrest F. J., Adler W. H., Munster A. M., Winchurch R. A. Increased levels of circulating interleukin 6 in burn patients. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990 Mar;54(3):361–371. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90050-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon D. N., Barrow R. E., Rutan T. C., Minifee P., Jahoor F., Wolfe R. R. Effect of propranolol administration on hemodynamic and metabolic responses of burned pediatric patients. Ann Surg. 1988 Oct;208(4):484–492. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198810000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munster A. M., Xiao G. X., Guo Y., Wong L. A., Winchurch R. A. Control of endotoxemia in burn patients by use of polymyxin B. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1989 Jul-Aug;10(4):327–330. doi: 10.1097/00004630-198907000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijsten M. W., Hack C. E., Helle M., ten Duis H. J., Klasen H. J., Aarden L. A. Interleukin-6 and its relation to the humoral immune response and clinical parameters in burned patients. Surgery. 1991 Jun;109(6):761–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijsten M. W., de Groot E. R., ten Duis H. J., Klasen H. J., Hack C. E., Aarden L. A. Serum levels of interleukin-6 and acute phase responses. Lancet. 1987 Oct 17;2(8564):921–921. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt J. T. Fever versus hyperthermia. Fed Proc. 1979 Jan;38(1):39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt J. T. Passage of immunomodulators across the blood-brain barrier. Yale J Biol Med. 1990 Mar-Apr;63(2):121–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B. H., Caldwell F. T., Jr, Cone J. B. Ibuprofen lowers body temperature and metabolic rate of humans with burn injury. J Trauma. 1992 Feb;32(2):154–157. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmore D. W., Long J. M., Mason A. D., Jr, Skreen R. W., Pruitt B. A., Jr Catecholamines: mediator of the hypermetabolic response to thermal injury. Ann Surg. 1974 Oct;180(4):653–669. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197410000-00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winchurch R. A., Thupari J. N., Munster A. M. Endotoxemia in burn patients: levels of circulating endotoxins are related to burn size. Surgery. 1987 Nov;102(5):808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]