Abstract

Histone H2A has been found to be efficient in DNA delivery into a number of cell lines. We have reasoned that this DNA-delivery activity is mediated by two mechanisms: (i) electrostatically driven DNA binding and condensation by histone and (ii) nuclear import of these histone H2A⋅DNA polyplexes via nuclear localization signals in the protein. We have identified a 37-aa N-terminal peptide of histone H2A that is active in in vitro gene transfer. This peptide can function as a nuclear localization signal and can bind DNA. Amino acid substitutions that replace positively charged residues and/or DNA-binding residues of this peptide obliterate transfection activity. The introduction of a proline in the first turn of an α-helix of this 37-mer obliterates transfection activity, suggesting that the integrity of the α-helical structure of the N-terminal region of histone H2A is related to its transfection activity.

Keywords: transfection‖nuclear localization signal‖DNA binding

Gene transfer into eukaryotic cells has the potential to treat a large number of incurable diseases. The goal of nonviral gene therapy is to mimic the successful viral mechanisms for overcoming cellular barriers that block efficient expression of the target gene while minimizing the toxicities associated with gene delivery (1). The capabilities of a synthetic nonviral vector could include specific binding to the cell surface, entry, endosomal escape, translocation to the nucleus, and in some cases stable integration into the target cell genome. The rate-limiting step of current nonviral gene delivery techniques is the transfer of encapsulated plasmids from the endosomes to the nucleus (2). The potential advantages of protein/peptide gene transfer include ease of use, production, purity, homogeneity, ability to target nucleic acids to specific cell types, the potential for cost-effective large-scale manufacture, modular attachment of targeting ligands, and the lack of limitation on the size or type of the nucleic acid that can be delivered (1). The critical first step for efficient gene delivery is the formation of the polyplex, or complex between DNA and protein/peptide (1–3).

Eukaryotic DNA within the nucleus is packaged by wrapping around a histone octamer consisting of two molecules each of histone H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, and this packaging has dramatic effects on DNA metabolism and gene regulation (reviewed by Van Holde in ref. 4). We determined that histone octamers mediate transfection into a number of cell lines and that this activity is localized to H2A. It was not observed with other histones or cationic peptides (5, 6). Previous studies have demonstrated that histones H1 (7–12), H2A (5, 6, 13, 14), and H3 and H4 (15) are effective mediators of transfection. The postulated mechanisms by which histone H1 increases gene transfection are through DNA condensation, DNase protection, and the mediation of nuclear import. In these studies, histone H1 was considered to be the subclass of histones that mediates efficient gene transfer in the presence of chloroquine. Bottger et al. (8) characterized transfection-active DNA-packaging proteins in the cell nucleus of calf thymus cells by preparing acid nuclear extracts with perchloric acid and subsequent protein fractions by stepwise acetone precipitation. Histone H1 was purified from an active nuclear extract and identified by N-terminal amino acid sequencing. It was found to be effective in transfection, particularly in the presence of CaCl2, RPMI medium 1640, and chloroquine. In the absence of chloroquine, its effect on transfection was minimal, which is consistent with our findings. The most active fractions identified contained histone H1 and the nonhistone protein HMG17. The nonhistone proteins HMG1 and HMG2 also may have a role as DNA carriers for gene transfer (11). Other investigators claim that histone H3 and H4 are effective in gene delivery of the HIV-1 tat gene in Jurkat cells (15); neither histone H1 nor histone H2A were effective in this study. In our hands, calf thymus H2A was an effective mediator of transfection in the absence of the extensive interactions provided by H2B (18) in the nucleosome. We reasoned that complexing DNA with histones could mediate transfection effectively by two mechanisms: (i) polyplex formation via electrostatically driven DNA binding and condensation by histone and (ii) polyplex nuclear import via nuclear localization signals in histones. Histone H2A, a component of the histone octamer that packages genomic DNA in eukaryotes, can mediate transfection efficiently (5) in a number of cell lines (6) and has been used for transient expression of cytokines to effect antitumor response in a murine neuroblastoma model system (14). This transfection activity is reconstituted with a 37-aa peptide fragment that binds DNA and can function as a nuclear localization signal. Specific substitutions in this peptide on the basis of its local structure in the context of the nucleosome suggest that the peptide conformation may control transfection activity.

Methods

Transfection Assay.

The transfection assay has been described previously (5, 6). Briefly, 20 μl of histone H2A (typical concentration range, 0–150 μM) or peptide (typical concentration range, 0–1,000 μM) is combined with 20 μl of plasmid DNA (typical concentration range, 0–160 μg/ml) and 40 μl of Opti-MEM medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Peptides were synthesized by Genemed Synthesis (South San Francisco, CA), Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL), and the Core Protein and DNA facility of The Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, CA). Peptides 1–8 were synthesized by the Core Protein facility at The Scripps Research Institute. Peptides 11–14 were synthesized by Research Genetics. All remaining peptides were synthesized by Genemed Synthesis. All peptides were HPLC-purified to >90% purity by using reverse-phase column. For all the peptides described, large matrices of differing concentrations of DNA and peptide were assayed to determine the conditions for peak transfection results in COS-7 cells.

Confocal Studies.

Confocal studies were performed by using a Zeiss Axiovert S100TV wide-field fluorescent microscope with a Bio-Rad MRC-1024 confocal laser scanning system equipped with LASERSHARP 3.2 software. H2A at 2 mg/ml in 0.1 M sodium carbonate (pH 9) was incubated in the dark for at least 8 hours with 1 mg/ml rhodamine (tetramethylrhodamine-5-isothiocyanate, Molecular Probes), and excess label was removed by dialysis against sterile endotoxin-free water (LAL reagent water, BioWhittaker). Plasmid DNA was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate by using the Panvera Label IT kit (Madison, WI). The histone H2A⋅DNA polyplexes were prepared with histone H2A at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and DNA at a concentration of 40 μg/ml for the transfection of COS-7 cells with the modification that 10% of the histone H2A and plasmid DNA, respectively, was labeled fluorescently and the cells were grown on coverglasses in 6-well tissue-culture dishes. Confocal microscopy was performed 24 h after the start of transfection on cells washed four times with 1× PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA) for 10 min at room temperature followed by four more washes with 1× PBS. The fixed cells on coverglasses subsequently were mounted onto glass slides with a drop of Slowfade (Molecular Probes) and stored in the dark at 4°C. Serial z sections of 0.2-μm depth were taken by using an ×63 oil immersion lens; 10 z sections were taken per field. Images were displayed by using the Bio-Rad LASERSHARP 3.2 software package.

Nuclear Localization.

The pCMVβ plasmid, encoding β-galactosidase under a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, was mutagenized by QuikChange protocol (Stratagene) to introduce an XmaI site (primers GCTCAAGCGCGATCCCGGGGTTTTACAACGTCG and CGACGTTGTAAAACCCCGGGATCGCGCTTGAGC) to clone fragments corresponding to amino acids 1–37 and 18–34 of H2A generated by PCR from human genomic DNA. Plasmids verified by sequencing were prepared by using Qiagen Plasmid Endofree kits (Chatsworth, CA) and used to transfect COS-7 cells grown on coverglasses in 6-well tissue-culture dishes and transfected with Superfect (Qiagen) according to manufacturer recommendations. Two days after DNA addition, cells were washed twice with PBS and examined by indirect immunofluorescence essentially as described (21) by using a mouse anti-β-galactosidase primary antibody (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and goat anti-mouse secondary antibody.

Results and Discussion

Peptide Reconstitution of DNA Delivery.

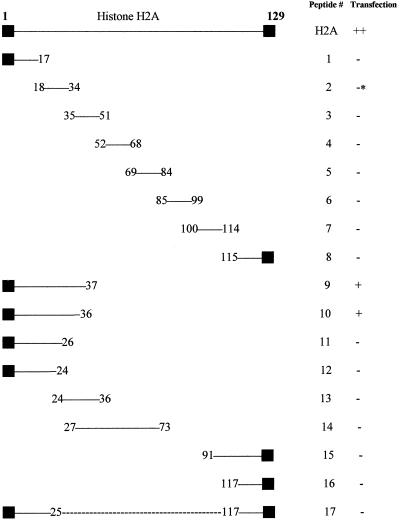

Peptides spanning the calf thymus histone H2A sequence were synthesized and tested for their ability to transform a β-galactosidase reporter gene into COS-7 cells (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Systematically generated peptides 1–8, ≈17-aa long, were inactive. Peptides corresponding to consecutive regions of charged amino acids peptides 10, 12, 13, and 16 were synthesized, and peptide 10, corresponding to residues 1–36 of histone H2A, was found to be active. Peptides that subdivided this N-terminal region (peptides 11–14) or fused it with the C terminus (peptide 17) had background levels of transfection activity. Similarly, peptide chimeras of the N-terminal portion of peptide 10 fused with sequences from H2B, H3, and H4 (peptides 27–29) lacked significant transfection activity. A 17-mer (peptide 2) consisting of residues 18–34 of histone H2A was able to mediate transfection but at higher concentrations than peptides 9 or 10. Reexamination of 1–8 at higher peptide (1,000–2,000 μM) and DNA (1.25–160 μg/ml) concentrations subsequent to these results demonstrated that only peptide 2 was active at these higher concentrations (data not shown). 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactoside staining revealed that histone H2A and the active 37-mer (peptide 9) transfect between 5 and 10% of COS-7 cells, whereas peptide 2, the 17-mer, transfects less than 1% of these cells (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the peptides tested for transfection used in this study. Schematic representation of key peptides synthesized to determine the active region of the histone H2A molecule in the mediation of DNA transfection. Intermediate levels of transfection (+) are defined here as peak transfection levels yielding β-galactosidase activity between 5 and 15,000 pg; high levels of transfection (++) yield higher, and background or low levels of transfection (−) yield lower β-galactosidase activity than those defined for intermediate levels of transfection activity. These peptides were tested in a matrix in a 96-well plate. The dashed line in the representation of peptide 17 illustrates that it is a fusion of the N and C termini of histone H2A, respectively. ■, designates the first and last amino acids of histone H2A. *, see the Table 1 legend.

Table 1.

Peptides used to define the active region of histone H2A

| Sequence | Transfection | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Histone H2A | ++ |

| 1 | S1 GRGKQGGKARAKAKTR17 | − |

| 2 | S18 SRAGLQFPVGRVHRLL34 | −* |

| 3 | R35 KGNYAERVGAGAPVYL51 | − |

| 4 | A52 AVLEYLTAEILELAGN68 | − |

| 5 | A69 ARDNKKTRIIPRHLQ84 | − |

| 6 | L85 AIRNDEELNKLLGK99 | − |

| 7 | V100 TIAQGGVLPNIQAV114 | − |

| 8 | L115 LPKKTESHHKAKGK129 | − |

| 9 | S1 GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF PVGRV HRLLR KG37 | + |

| 10 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF PVGRV HRLLR K36W | + |

| 11 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF P26 | − |

| 12 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQ24W | − |

| 13 | Q24FPVGRVHRLLRK36W | − |

| 14 | V27GRVHRLLRKGNYAERVGAGAPVYLAAVLEYLTAEILELAGNAARDN73 | − |

| 15 | E91ELNKLLGKVTIAQGGVLPNIQAVLLPKKTESHHKAKGK129 | − |

| 16 | P117KKTESHHKAKGK129W | − |

| 17 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQFP117KKTESHHKAKGK129 W | − |

| 18 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF GVGRV HRLLR KG37 | − |

| 19 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF PVGRP HRLLR KG37 | − |

| 20 | S1G SGS QGGSA SASAS TSSSS AGLQF PVGRV HRLLR KG37 | − |

| 21 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF PVG SV HS LLS S G37 | − |

| 22 | S1GRGK QGGSA SASAS TSSSS AGLQF PVGRV HRLLR KG37 | − |

| 23 | PKKKRKVV27GRVHRLLRKG37 | − |

| 24 | PEPAKSAPAPKKGSKKAVTKAQKKDGKKRKRSRKV27GRVHRLLRKG37 | − |

| 25 | ARTKQTARKSTGGKAPRKQLATKAARKSAPATGGVKKPHRYRPGV27GRVHRLLRKG37 | − |

| 26 | SGRGKGGKGLGKGGAKRHRKVLRDNIQGITV27GRVHRLLRKG37 | − |

| 27 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF P26 KESY SVYVY KVL | − |

| 28 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF P26 TVAL REIRR YQK | − |

| 29 | S1GRGK QGGKA RAKAK TRSSR AGLQF P26 KPAI RRLAR R | − |

Portions of peptides that contain histone H2A sequences are designated by superscript numbering of the corresponding region of histone H2A. Transfection activity is defined as in the Fig. 1 legend. The underlined bold font of the sequence of peptide 9 corresponds to its DNA contact sites, as illustrated and described in the Fig. 2 legend. The bold font used for parts of peptides 18–22 represent amino acid substitutions in the sequence of peptide 9. Peptides 23–26 represent amino acids 27–37 of histone H2A preceded by the simian virus 40 nuclear localization signal (16, 17) and the N-terminal sequences of histone H2B, H3, and H4, respectively. Peptides 27–29 represent amino acids 1–26 of histone H2A followed by the sequence of the first α-helix of histone H2B, H3, and H4, respectively. The asterisk (*) for the transfection activity of peptide 2 indicates that there was only background transfection activity in the initial screening with this peptide. Peptide 2 can mediate transfection when high concentrations (1,000–2,000 μM) are used in contrast to peptides 1 and 3–8, which yield only background levels of transfection even under these conditions.

DNA Binding.

In previous studies, we demonstrated that histone H2A was effective in transfection, whereas histones H1, H2B, H3, and H4 were ineffective under the same conditions (5, 6). However, each of these histones can bind DNA, as demonstrated by agarose gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Similarly, DNA binding is observed for both peptides effective in DNA transfection (peptides 2, 9, and 10), and those that are ineffective (peptides 18 and 19) bind to DNA, as demonstrated by agarose gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Thus, DNA binding alone is insufficient for effective transfection.

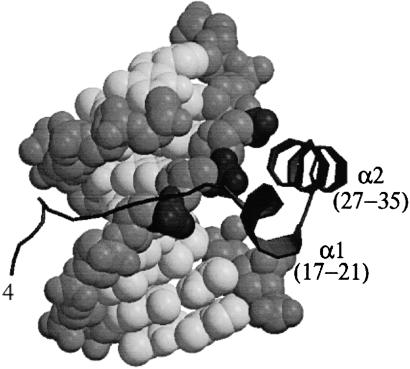

The N-terminal region of H2A delineated by the peptide studies described above constitutes one of the larger DNA-interaction surfaces generated by a contiguous polypeptide in the histone octamer crystal structure (18). This region forms two short α-helices (residues 17–21 and 27–35) interrupted by a short loop that allows the two helices to anchor three adjacent phosphates along one strand of DNA (Fig. 2). Although these peptides may not possess native H2A structural features, peptides that lack sequences corresponding to either one of these helices are not active in transformation (Table 1). Therefore, we designed a number of peptides to test predictions that could be made by analogy to the native H2A structure. Peptides replacing basic residues that make DNA contacts with serines (peptides 20–22; Table 1) do not stimulate transfection relative to background rates. Similarly, peptides designed to disrupt the second α-helix by introducing the P26G and the V30P modifications (peptides 18 and 19; Table 1) are inefficient in transfection.

Figure 2.

DNA binding to the N-terminal region of histone H2A. The N-terminal 35 residues of histone H2A (black ribbon) bind DNA (gray backbone, white bases, cpk model) in the context of the histone octamer (PDB code 1AOI, www.rcsb.org; ref. 18). The α1–turn–α2 motif (residues 17–35) binds three adjacent phosphates highlighted in dark gray along one DNA strand. The N-terminal extension lies within the adjacent DNA minor groove. This figure was generated with MOLSCRIPT (19) and RASTER3D (20).

Nuclear Localization.

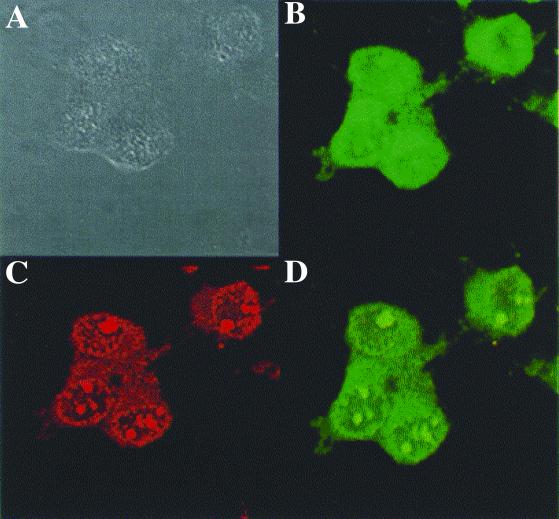

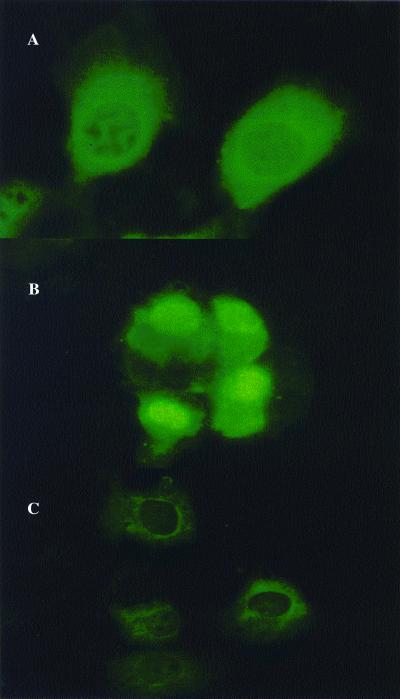

In addition to DNA binding, the active transfection agent likely aids in nuclear localization of the DNA target. Full-length histone H2A was labeled with rhodamine and used to transfect COS-7 cells with fluorescein-labeled pCMVβ. After 24 h, both H2A and plasmid DNA were observed with confocal microscopy to distribute in both the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 3). The active 37-mer peptide was tested also for its ability to direct nuclear localization of β-galactosidase (21, 22). The plasmids encoding β-galactosidase fused to active peptides 9 and 2 at the N terminus (pCMVβ-9 and pCMVβ-2) were transfected into COS-7 cells by using the commercial reagent Superfect. Indirect immunofluorescence of the cells 48 h after transfection demonstrates that β-galactosidase produced from pCMVβ and pCMVβ-2 are in the cytoplasm, whereas pCMVβ-9 is primarily nuclear (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Confocal microscopy of transfected COS-7 cells. Confocal microscopy of COS-7 cells 24 h after transfection with polyplexes of pCMVβ DNA and histone H2A; 10% of this DNA was FITC-labeled and 10% of this histone H2A was rhodamine-labeled. (A) Differential interference contrast (DIC) image of COS-7 cells. (B) The same cells as in A depicting the localization of FITC-labeled DNA transfected with polyplexes of fluorescein-labeled pCMVβ DNA. (C) The same cells as in A depicting the localization of rhodamine-labeled histone H2A. (D) The same cells as in A depicting the colocalization of FITC-labeled DNA and rhodamine-labeled DNA. The same cells as in A depicting the colocalization of FITC-labeled DNA and rhodamine-labeled DNA in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, suggesting that the DNA and histone H2A in these polyplexes not only forms a complex but is capable also of nuclear entry where the target gene can be transcribed.

Figure 4.

Indirect immunofluorescence of β-galactosidase fusions in COS-7 cells. Results of COS-7 cells transfected with pCMVβ (control, A), pCMVβ-9 (B), and pCMVβ-2 (C) are shown. β-Galactosidase is detected in the cytoplasm of cells in A and C and in both the cytoplasm and nuclei of cells in B. These results demonstrate that the sequence of peptide 9 contains a complete and functional nuclear localization signal, whereas that of peptide 2 does not.

Why is histone H2A better than other histones for this activity? DNA binding to histones in chromatin is in the context of the intact core nucleosome made up of eight individual histones. DNA contact regions are thereby scattered across the three-dimensional structures of the different histones. Histone H2A is the only one with a real cluster of DNA binding sites localized in a short region that is defined structurally (ref. 6; Fig. 2). This clustered region is also near the N terminus of the histone H2A molecule that acts as a nuclear localization signal. The histone H2A peptide (peptide 9) representing this isolated region may be uniquely suited to bind DNA and shuttle to the nucleus. Thus, there is a correlation between the structure and function of histone H2A peptide-mediated transfection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Malcolm Wood (The Scripps Research Institute) for his help with confocal microscopy and Dr. Matthias Falk (The Scripps Research Institute) for his help with immunofluorescence. D.B. is the recipient of the Clinician-Scientist Award of The Medical Research Council of Canada/Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MRC/CIHR) and a Clinician-Scientist Award (Chercheur-Boursier-Clinicien) of the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). This work is supported by the Stein Endowment Fund. This is manuscript no. 14309-MEM of The Scripps Research Institute.

Abbreviation

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

References

- 1.Balicki D, Beutler E. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:69–86. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felgner P L. Sci Am. 1997;276(6):102–106. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0697-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felgner P L, Barenholz Y, Behr J P, Cheng S H, Cullis P, Huang L, Jessee J A, Seymour L, Szoka F, Thierry A R, et al. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:511–512. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.5-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Holde K E. Chromatin. New York: Springer; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balicki D, Beutler E. Mol Med. 1997;3:782–787. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balicki D. Ph.D. thesis. La Jolla, CA: The Scripps Research Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fritz J D, Herweijer H, Zhang G, Wolff J A. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:1395–1404. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.12-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bottger M, Zaitsev S V, Otto A, Haberland A, Vorob'ev V I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1395:78–87. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagstrom J E, Sebestyen M G, Budker V, Ludtke J J, Fritz J D, Wolff J A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1284:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budker V, Hagstrom J E, Lapina O, Eifrig D, Fritz J, Wolff J A. BioTechniques. 1997;23:142–147. doi: 10.2144/97231rr02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaitsev S V, Haberland A, Otto, Vorob'ev V I, Haller H, Bottger M. Gene Ther. 1997;4:586–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haberland A, Knaus T, Zaitsev S V, Buchberger B, Lun A, Haller H, Bottger M. Pharm Res. 2000;17:229–235. doi: 10.1023/a:1007581700996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh D, Rigby P W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3113–3114. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.15.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balicki D, Reisfeld R A, Pertl U, Beutler E, Lode H N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11500–11504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210382997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demirhan I, Hasselmayer O, Chandra A, Ehemann M, Chandra P. J Hum Virol. 1998;1:430–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weis K, Mattaj I W, Lamond A I. Science. 1995;268:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.7754385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agah R, Frenkel P A, French B A, Michael L H, Overbeek P A, Schneider M D. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:169–179. doi: 10.1172/JCI119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luger K, Mader A W, Richmond R K, Sargent D F, Richmond T J. Nature (London) 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraulis P J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merritt E A, Bacon D J. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumann G, Castrucci M R, Kawaoka Y. J Virol. 1997;71:9690–9700. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9690-9700.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreland R B, Langevin G L, Singer R H, Garcea R L, Hereford L M. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4048–4057. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.11.4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]