Abstract

Objective

Advanced ovarian clear cell carcinoma (OCCC) is associated with poor outcomes owing to chemoresistance. Bevacizumab (Bev) is increasingly being used to treat advanced ovarian cancer; however, its efficacy in OCCC remains unclear. This study evaluated the treatment outcomes of frontline bevacizumab chemotherapy in patients with OCCC.

Methods

This retrospective multi-institutional study included patients diagnosed with advanced OCCC at eight institutions in Japan between 2008 and 2018. Patients were categorized into pre and post-market groups based on the Bev approval dates. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were analyzed using univariate and multivariate methods. Additionally, patients were classified into Bev-treated (Bev+) and non-Bev-treated (Bev−) groups, and their prognoses were compared.

Results

A total of 96 patients were in the pre-market group and 82 in the post-market group. The post-market group had a significantly higher proportion of patients with poor performance status and patients who underwent interval debulking surgery (p<0.01 and p<0.01, respectively). Univariate analysis demonstrated a better PFS in the post-market group (p=0.041). In multivariate analysis, better PFS (hazard ratio [HR]=0.52; p=0.002) and OS (HR=0.47; p=0.002) were observed in the post-market group than in the pre-market group. Bev+ patients had significantly better PFS and OS than Bev− patients in univariate (p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively) and multivariate analyses (PFS: HR=0.36; p<0.001 and OS: HR=0.21; p=0.001, respectively).

Conclusion

Incorporating Bev into frontline chemotherapy may improve outcomes in patients with advanced OCCC.

Keywords: Bevacizumab; Adenocarcinoma, Clear Cell; Ovarian Neoplasms

Synopsis

Because of its chemo-resistant nature, specific chemotherapeutic regimen for ovarian clear cell carcinoma has not been established and no molecular targeted therapy has been demonstrated beneficial. This study firstly showed potential benefit of bevacizumab against advanced ovarian clear cell carcinoma, as front-line treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Among the five distinct histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), ovarian clear cell carcinoma (OCCC) has unique biological features, making it a distinct entity with specific treatment challenges [1]. The prevalence of OCCC varies geographically; while it accounts for only 1%–12% of EOC cases in Western countries, OCCC is relatively frequent in Asian countries, especially in Japan, constituting approximately 20% [2]. Additionally, OCCC ranks as the second most common histological type among the four types, and its incidence appears to have increased over time [3,4].

Although OCCC is less sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy than the other histological types of EOC, few clinical trials have specifically explored OCCC, resulting in insufficient evidence regarding the optimal chemotherapeutic approach [5].

Bevacizumab (Bev) was the first molecular-targeted agent used for EOC treatment and was utilized across histological types before poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor approval. GOG218 and ICON7 demonstrated that the addition of Bev to platinum-based chemotherapy improved the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with advanced EOC, albeit in a small number of OCCC cases [6,7]. Subsequently, with the incorporation of PARP inhibitors, the treatment strategy for EOC has evolved from Bev plus platinum regimens to regimens including PARP inhibitors [8]. However, OCCC has a different genetic background than other types of EOC, with few cases showing homologous recombination deficiency and BRCA variants [9]. Consequently, a PARP inhibitor-based regimen does not appear to be a reasonable choice for OCCC treatment. According to our previous retrospective study conducted at a single institution, Bev may be beneficial in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy for OCCC [10]. Therefore, we conducted a multi-institutional retrospective study to confirm the efficacy of Bev with platinum agents as primary chemotherapy for advanced OCCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design and patients

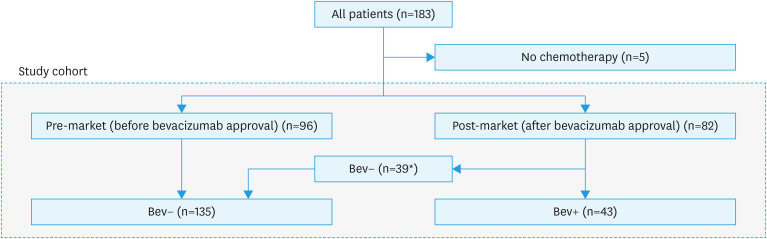

This was a retrospective multi-institutional observational study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (#M10037) of Chiba University Hospital and all the participating institutions. Patient consent was waived in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Research Involving Human Subjects in Japan [11]. We included patients with stage III and IV OCCC who underwent primary treatment at eight participating institutions in Japan between 2008 and 2018. Patients who did not receive chemotherapy were excluded (Fig. 1). Since Bev was approved in November 2013 in Japan, patients were divided into two groups: those who received primary treatment before Bev approval (pre-market) and those who received it after approval (post-market) (Fig. 1). First, to assess the impact of Bev on patient outcomes, we compared PFS and overall survival (OS) between the pre and post-market groups using univariate and multivariate analyses. In addition, we compared the survival outcomes between patients who received Bev and those who did not (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Patients’ cohort.

Bev+, bevacizumab-treated; Bev−, non-bevacizumab-treated; TC, paclitaxel and carboplatin.

*The reasons of no addition of bevacizumab: patient’s desire (n=2), clinical trial (n=2), doctor’s preference (n=20; thrombosis n=8, dose dense paclitaxel and carboplatin n=8, unknown n=4), unknown (n=15).

The surgical complexity score (SCS) was used to rate the number and complexity of the surgical procedures required for maximal resection [12]. Based on the SCS, the patients were stratified into low (0–3), intermediate (4–7), or high (8–18) SCS groups.

2. Chemotherapy

The treatment is a combination of cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy. The paclitaxel and carboplatin (TC) regimen included triweekly, weekly, and dose-dense regimens. In detail, the triweekly regimen was (carboplatin: area under the curve [AUC] 5–6 on day 1 of every 3 weeks plus paclitaxel: 175 mg/m2 on day 1 of every 3 weeks; 6 cycles without break), weekly regimen was (carboplatin: AUC 2–3 on days 1, 8, and 15 of every 3 weeks plus paclitaxel: 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of every 3 weeks; 6 cycles without break), and dose-dense regimen was (carboplatin: AUC 6 on day 1 of every 3 weeks plus paclitaxel: 80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of every 3 weeks; 6 cycles without break). Docetaxel and carboplatin regimen was (carboplatin: AUC 5–6 on day 1 of every 3 weeks plus docetaxel: 75 mg/m2 on day 1 of every 3 weeks; 6 cycles without break). The irinotecan and cisplatin regimen was (irinotecan: 60 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 plus cisplatin: 60 mg/m2 on day 1; 6 cycles without break). Bev (15 mg/kg every 3 weeks) was administered to patients without any contraindications after its approval in November 2013 in Japan for the treatment of ovarian cancer. Chemotherapy incompletion was defined as fewer than 6 cycles of cytotoxic chemotherapy. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events scale, version 4.0, published by the National Cancer Institute, was used to grade the toxicity.

3. Statistics

Patient characteristics were compared between the pre- and post-market periods using the Fisher exact or χ2 tests. We compared PFS and OS between the 2 groups using the Kaplan-Meier method and Wilcoxon test. A multiple Cox regression model was used for the multivariate analysis to explore the impact of prognostic factors on OS and PFS. Subsequently, we conducted the same analyses to compare outcomes between patients who received Bev and those who did not. In the Cox regression analysis, we determined the maximum number of covariates based on the events per variable criterion [13,14]. Prior to the Cox analysis, we performed multiple imputations to address missing values and minimize bias [15]. The imputation process included the following variables: age, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, D-dimer level, chemotherapy regimen, thrombosis, treatment period (pre-/post-market), serum albumin level, cancer antigen 125 (CA125) level, SCS timing of debulking surgery, Bev use, residual tumor after surgery, performance status (PS), survival events, and Nelson-Aalen estimator. A total of 100 imputations were performed, with 50 iterations per iteration. For the sensitivity analysis, we performed a Cox model analysis with a smaller number of variables than the main analysis.

Regarding the follow-up period, OS and PFS beyond 60 months were censored at 60 months.

All p-values were two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered significant. PFS was defined as the interval between the date of treatment initiation and the date of diagnosis of the first recurrence. OS was defined as the time interval between treatment initiation and the date of death or last follow-up. The results were considered significant at p<0.05. Median PFS and OS with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) also were determined. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP statistical software, version 11.0 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) and R version 4.3.1 (2023-06-16 ucrt) – “Beagle Scouts.”

RESULTS

First, we compared the outcomes between the pre- and post-market groups. The patient characteristics of each group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Pre-market (n=96) | Post-market (n=82) | p-value | Bev− (n=135) | Bev+ (n=43) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 53.0 [46.0–61.2] | 57.0 [49.2–62.0] | 0.11 | 54.0 [47.0–61.5] | 56.0 [49.5–65.0] | 0.25 | ||

| FIGO stage | ||||||||

| III | 83 (86.5) | 67 (81.7) | 0.51 | 118 (87.4) | 32 (74.4) | 0.07 | ||

| IIIA | 31 (32.3) | 28 (34.1) | 46 (34.1) | 13 (30.2) | ||||

| IIIB | 18 (18.8) | 10 (12.2) | 22 (16.3) | 6 (14.0) | ||||

| IIIC | 34 (35.4) | 29 (35.4) | 50 (37.0) | 13 (30.2) | ||||

| IV | 13 (13.5) | 15 (18.3) | 17 (12.6) | 11 (25.6) | ||||

| Performance status | ||||||||

| 0–1 | 78 (81.2) | 54 (65.9) | <0.01 | 100 (74.1) | 32 (74.4) | 0.01 | ||

| 2–3 | 2 (2.1) | 13 (15.9) | <0.01* | 7 (5.2) | 8 (18.6) | 0.03* | ||

| Unknown | 16 (16.7) | 15 (18.3) | 28 (20.7) | 3 (7.0) | ||||

| BRCA status | ||||||||

| No mutation | 11 (11.5) | 17 (20.7) | 0.1 | 19 (14.0) | 9 (20.9) | 0.14 | ||

| Unknown | 85 (88.5) | 65 (79.3) | 116 (86.0) | 34 (79.1) | ||||

| Serum albumin before treatment (g/dL) | 3.5 [3.1–4.0] | 3.5 [2.9–4.0] | 0.59 | 3.5 [3.0–4.0] | 3.3 [2.9–3.8] | 0.26 | ||

| CA125 (unit) | 314.8 [127.3–901.0] | 233.4 [91.0–547.2] | 0.07 | 279.0 [93.0–800.0] | 258.4 [124.2–612.3] | 0.98 | ||

| D-dimer before treatment (ng/dL) | 4.0 [2.2–13.4] | 3.5 [1.2–10.2] | 0.14 | 3.9 [2.1–12.8] | 3.0 [1.6–8.7] | 0.28 | ||

| D-dimer before treatment (ng/dL) | 4.0 [2.2–13.4] | 3.5 [1.2–10.2] | 0.14 | 3.9 [2.1–12.8] | 3.0 [1.6–8.7] | 0.28 | ||

| Thrombosis (deep vein/pulmonary/Trousseau’s syndrome) | ||||||||

| Absent | 62 (64.6) | 50 (61.0) | 0.37 | 83 (61.5) | 29 (67.4) | 0.4 | ||

| Present | 30 (31.2) | 31 (37.8) | 47 (34.8) | 14 (32.6) | ||||

| Unknown | 4 (4.2) | 1 (1.2) | 5 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Timing of debulking surgery | ||||||||

| Primary | 88 (91.7) | 61 (74.4) | <0.01 | 118 (87.4) | 31 (72.1) | 0.01 | ||

| Interval | 4 (4.2) | 18 (22.0) | <0.01† | 11 (8.1) | 11 (25.6) | 0.03† | ||

| Chemotherapy only | 4 (4.2) | 3 (3.7) | 6 (4.4) | 1 (2.3) | ||||

| SCS | 4.0 [2.0–5.0] | 4.0 [2.0–6.0] | 0.08 | 4.0 [2.0–5.0] | 5.0 [3.5–7.0] | <0.01 | ||

| Low (0–3) | 44 (45.8) | 26 (31.7) | 0.12 | 59 (43.7) | 11 (25.6) | 0.02 | ||

| Moderate (4–7) | 43 (44.8) | 43 (52.4) | 64 (47.4) | 22 (51.2) | ||||

| High (8–18) | 9 (9.4) | 13 (15.9) | 12 (8.9) | 10 (23.3) | ||||

| Residual tumor | ||||||||

| 0 cm | 48 (50.0) | 53 (64.6) | 0.11 | 72 (53.3) | 29 (67.4) | 0.26 | ||

| >0 cm and ≤1 cm | 24 (25.0) | 12 (14.6) | 0.07‡ | 30 (22.2) | 6 (14.0) | 0.12‡ | ||

| >1 cm | 24 (25.0) | 17 (20.7) | 33 (24.4) | 8 (18.6) | ||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Paclitaxel carboplatin, triweekly | 51 (53.1) | 38 (46.3) | <0.01 | 73 (54.1) | 16 (37.2) | |||

| Paclitaxel carboplatin, dose-dense | 16 (16.7) | 19 (23.2) | 26 (19.3) | 9 (20.9) | ||||

| Paclitaxel carboplatin, weekly | 11 (11.5) | 21 (25.6) | 14 (10.4) | 18 (41.9) | ||||

| Docetaxel carboplatin triweekly | 7 (7.3) | 2 (2.4) | 9 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Irinotecan cisplatin | 8 (8.3) | 1 (1.2) | 9 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Others | 3 (3.1) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Completion of 6 first-line chemotherapy | ||||||||

| Complete (≥6 cycles) | 70(72.9) | 65 (79.3) | 0.38 | 98 (72.6) | 37 (86.0) | 0.16 | ||

| Incomplete (<6 cycles) | 26 (27.1) | 17 (20.7) | 37 (27.4) | 6 (14.0) | ||||

| Bev use | ||||||||

| Bev− | 96 (100.0) | 39 (47.6) | <0.01 | 135 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Bev+ | 0 (0.0) | 43 (52.4) | 0 (0.0) | 43 (100.0) | ||||

| Bevacizumab cycles | - | - | - | 16.0 [6.0–21.0] | ||||

Values are presented as median [interquartile range] or number (%).

Bev, bevacizumab; Bev+, bevacizumab-treated; Bev−, non-bevacizumab-treated; CA125, cancer antigen 125; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; SCS, surgical complexity score.

*0–1 versus 2–3; †Primary versus interval or chemotherapy alone; ‡0 cm versus the presence of a residual tumor.

The median follow-up duration was 31 months (pre-market, 26 months; post-market, 38 months). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of age (p=0.11), FIGO stages III and IV (p=0.51), initial CA125 levels (p=0.07), thrombosis (p=0.37), SCS (p=0.08), or residual tumor size after debulking surgery (p=0.07) (Table 1). The prevalence of poor PS (PS 2 and 3) and interval debulking surgery (IDS)/chemotherapy was higher in the post-market group than in the pre-market group (p<0.01 and p<0.01, respectively; Table 1).

Regarding chemotherapy regimens, the triweekly TC regimen was predominant in the pre- and post-market periods, whereas weekly and dose-dense regimens were more commonly used in the post-market period. With respect to debulking surgery, the complete resection rates of patients who underwent IDS were lower than those of patients who underwent primary debulking surgery (PDS) during both periods (Table S1) [16,17,18,19,20]. The surgical methods are listed in Table S2. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of the specific procedures performed.

In the post-market period, 47.6% of the patients did not receive Bev (Table 1). The reasons for the non-administration of Bev, even in the post-market period, are detailed in Fig. 1. Of the 39 patients who did not receive Bev, 20 did not because of physician policies. This includes decisions not to use Bev with dose-dense paclitaxel and carboplatin regimen or concerns about thrombosis.

The median PFS was 10.6 months in the pre-market group and 17.8 months in the post-market group, and univariate analysis using the Wilcoxon test demonstrated significantly better PFS in the post-market group than in the other groups (p=0.041) (Fig. 2A). The median OS was 30.8 months in the pre-market group and 41.7 months in the post-market group, with no statistically significant difference in OS between the 2 groups (p=0.104) (Fig. 2B). The 4-year PFS rates were 21% and 28%. The 4-year OS rates were 37% and 50% in the pre- and post-market groups, respectively.

Fig. 2. Survival curves of pre- and post-market period.

(A) PFS and (B) OS.

OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors was conducted using a Cox regression model, which included nine covariates: age, PS, baseline CA125 levels, thrombosis, FIGO stage, SCS, pre-/post-market status, timing of debulking surgery, and residual tumor at debulking surgery. This analysis identified several independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS. Specifically, post-market period (hazard ratio [HR]=0.52; p=0.002 and HR=0.47; p=0.002 for PFS and OS, respectively), PS ≥2 (HR=3.00; p=0.001 and HR=3.09; p=0.001), CA125 (HR=1.00; p=0.046 and HR=1.00; p=0.019), IDS (HR=2.05; p=0.004 and HR=2.17; p=0.003), and residual tumor (HR=2.62; p<0.001 and HR=3.11; p<0.001) were all significant prognostic factors for PFS and OS (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariable Cox proportional analysis of risk factors, including the factor of pre-/post-market of Bev for PFS and OS for advanced clear cell carcinoma.

| Variables | PFS | OS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | HR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | ||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.250 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.026 | |

| PS | 0–1/2–3 | 3.00 | 1.60 | 5.64 | 0.001 | 3.09 | 1.62 | 5.90 | 0.001 |

| Thrombosis | −/+ | 1.05 | 0.72 | 1.52 | 0.803 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.378 |

| CA125 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.046 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.019 | |

| FIGO stage | III/IV | 1.36 | 0.86 | 2.16 | 0.189 | 1.44 | 0.87 | 2.37 | 0.153 |

| Pre-/Post-market | Pre/Post | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.78 | 0.002 | 0.47 | 0.3 | 0.75 | 0.002 |

| SCS | ≤4/≥5 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 1.2 | 0.283 | 1.14 | 0.73 | 1.79 | 0.555 |

| Debulking surgery | PDS/IDS* | 2.05 | 1.27 | 3.3 | 0.004 | 2.17 | 1.31 | 3.6 | 0.003 |

| Residual tumor | −/+ | 2.62 | 1.82 | 3.78 | <0.001 | 3.11 | 2.03 | 4.75 | <0.001 |

CA125, cancer antigen 125; CI, confidence interval; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratio; IDS, interval debulking surgery; OS, overall survival; PDS, primary debulking surgery; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, performance status; SCS, surgical complexity score.

*Includes chemotherapy only.

For the sensitivity analysis, we performed a Cox model analysis with a reduced number of variables, such as age, PS, pre-/post-market, and residual tumor, and demonstrated consistent results of significantly better PFS and OS in the post-market period (Table S3).

Second, patients who received Bev (Bev+) were compared with those who did not (Bev−). The patient characteristics of the Bev+ and Bev− groups are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age (p=0.25), FIGO stage (p=0.07), initial CA125 level (p=0.98), thrombosis (p=0.4), or residual tumor size after debulking surgery (p=0.12) (Table 1). However, the Bev+ group had a higher prevalence of poor PS (PS 2 and 3), higher SCS, and more patients who underwent IDS/chemotherapy only, with statistical significance observed for these factors (p=0.03, p<0.01, and p=0.03, respectively) (Table 1).

In terms of chemotherapy regimens, triweekly TC was the most common regimen in the Bev− group, whereas weekly and dose-dense regimens were more frequently used in the Bev+ group. The median number of Bev cycles in the Bev+ group was 16 (interquartile range: 6–21) (Table 1).

The median PFS was 10.5 months in the Bev− group and 29.7 months in the Bev+ group. Wilcoxon test demonstrated significantly better PFS in patients who received Bev than in those who did not (p<0.001) (Fig. 3A). The median OS was 27.4 months in the pre-market group and 51.4 months in the post-market group, respectively. The Wilcoxon test demonstrated significantly better OS in patients who received Bev than in those who did not (p<0.001) (Fig. 3B). Multivariate analysis of prognosis was performed using a Cox regression model, which comprised nine covariate factors including age, PS, CA125 level at baseline, thrombosis, FIGO stage, SCS, Bev use, timing of debulking surgery, and residual tumor at debulking surgery. The analysis showed Bev use (HR=0.36; p<0.001 and HR=0.37; p=0.001), PS ≥2 (HR=3.75; p<0.001 and HR=3.37; p<0.001), IDS (HR=1.96; p=0.005 and HR=1.96; p=0.008), and residual tumor (HR=2.65; p<0.001 and HR=3.19; p<0.001) were independent prognostic factors for PFS and OS. Additionally, CA125 levels were associated with OS (HR=1.00; p=0.027), and FIGO stage IV was associated with poor PFS (HR=1.63; p=0.047) (Table 3).

Fig. 3. Survival curves according to bevacizumab use.

(A) PFS and (B) OS.

Bev+, bevacizumab-treated; Bev−, non-bevacizumab-treated; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Table 3. Multivariable Cox proportional analysis of risk factors, including the factor of Bev use for PFS and OS for advanced clear cell carcinoma.

| Variables | PFS | OS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | HR | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | p-value | ||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.404 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.036 | |

| PS | 0–1/2–3 | 3.75 | 1.92 | 7.3 | <0.001 | 3.37 | 1.74 | 6.54 | <0.001 |

| Thrombosis | −/+ | 0.98 | 0.67 | 1.42 | 0.899 | 1.14 | 0.76 | 1.72 | 0.515 |

| CA125 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.064 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.027 | |

| FIGO stage | III/IV | 1.63 | 1.01 | 2.64 | 0.047 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 2.79 | 0.052 |

| Bevacizumab | −/+ | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.64 | 0.001 |

| SCS | ≤4/≥5 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 1.43 | 0.826 | 1.31 | 0.83 | 2.06 | 0.246 |

| Debulking surgery | PDS/IDS* | 1.96 | 1.23 | 3.12 | 0.005 | 1.96 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 0.008 |

| Residual tumor | −/+ | 2.65 | 1.84 | 3.81 | <0.001 | 3.19 | 2.09 | 4.86 | <0.001 |

Bev, bevacizumab; CA125, cancer antigen 125; CI, confidence interval; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratio; IDS, interval debulking surgery; OS, overall survival; PDS, primary debulking surgery; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, performance status; SCS, surgical complexity score.

*Includes chemotherapy only.

For sensitivity analysis, we performed Cox model analysis with a reduced number of variables, such as age, PS, Bev use, and residual tumor, and demonstrated consistent results of significantly better PFS and OS in patients who received Bev (Table S4).

As a subgroup analysis, we compared the survival curves between the Bev− and Bev+ groups in patients with or without residual tumors after debulking surgery. Among patients without residual tumors, those who received Bev demonstrated significantly better PFS than those who did not (p=0.019) (Fig. S1). Similarly, in patients with residual tumors, Bev administration was associated with better PFS than no Bev administration (p=0.048) (Fig. S2).

Regarding adverse events of Bev, hypertension was the most common adverse event associated with Bev use. Gastrointestinal tract fistula formation occurred in only one patient (Table S5). The reasons for Bev discontinuation are listed in Table S6; disease progression was the most common reason, followed by proteinuria. No treatment-related deaths occurred in either of the groups.

DISCUSSION

This multi-institutional retrospective observational study demonstrated that patients with advanced OCCC may benefit from adding Bev to platinum-based chemotherapy as frontline adjuvant chemotherapy, supporting previous data with a smaller sample size [10].

Most patients with OCCC are diagnosed at an early stage and it has a favorable prognosis, and the 5-year disease-free survival rate of patients with stage I clear cell carcinoma is approximately 90% [21,22,23]. On the other hand, advanced OCCC, which accounts for approximately 30% of all OCCCs, exhibits significantly worse prognosis than serous carcinoma, with median disease-free survival reported to be 0.85 years, due to its chemo-resistant nature [5,21,22,23].

Several efforts have been made to overcome this chemoresistance. JGOG 3017 is the only phase III trial that has investigated OCCC-specific treatments. This trial included patients with newly diagnosed stage I to IV OCCC and compared survival outcomes between patients treated with a combination of irinotecan and cisplatin therapy (CPT-P) and those treated with TC therapy as standard therapy. Unfortunately, the CPT-P regimen did not improve PFS or OS in patients with OCCC compared with TC therapy [24]. Therefore, we continued to use TC therapy, the original regimen developed for serous ovarian cancer, to treat OCCC.

The molecular landscape of OCCC has been investigated and revealed genetic alterations such as ARID1a and PIK3CA mutation [25,26,27] and hyperactivation of several signaling pathways, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and interleukin-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathways in OCCC [28,29,30]. These pathways are activated in hypoxic environments and promote angiogenesis within the OCCC microenvironment [31,32,33]. For instance, Mabuchi et al. [34] reported that OCCC cells under intratumoral hypoxia strongly expressed VEGF, and Bev demonstrated antitumor efficacy against OCCC both in vitro and in vivo.

Bev has been incorporated into the frontline treatment of EOC based on the positive results of the GOG218 and ICON7 trials, which have proven beneficial for PFS in patients with advanced EOC [6,7]. In the ICON7 trial, an explanatory subgroup analysis for OCCC showed that Bev with platinum-based chemotherapy had no significant benefit compared to platinum-based chemotherapy alone [35]. In contrast, some reports have shown benefits of Bev in patients with OCCC. In a retrospective study, Kim et al. [36] reported that adding Bev to platinum-based chemotherapy improved PFS and OS in patients with recurrent OCCC. JGOG3022, a prospective observational cohort study on the frontline chemotherapy for EOC, showed that Bev plus platinum-based chemotherapy exhibited a high response rate (63.6%) in the OCCC cohort [37]. Gallego et al. [38] also demonstrated a high response rate to a Bev-containing regimen against OCCC, although only 6 patients with OCCC were included.

In this study, Bev was administered in combination with a dose-dense or weekly regimen of paclitaxel and carboplatin to many patients. However, 8 patients did not receive Bev because their physicians did not recommend the use of these regimens. At the time of the study, there was no evidence to support the benefit of combining Bev with a dose-dense or weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin regimen. Nevertheless, in clinical practice, Bev is used in a dose-dense regimen during this period based on the expectation of additional benefits from the higher dose of paclitaxel delivered by these regimens [39]. The launch of the ICON8B trial in 2011 may have fueled this expectation among gynecologic oncologists. Subsequently, the results of the ICON8B trial demonstrated that a dose-dense regimen combined with Bev was more beneficial for high-risk patients with EOC than a triweekly regimen [40]. However, Katsumata et al. [41] showed that patients with OCCC did not derive the same benefit from a dose-dense regimen as those with serous ovarian cancer. Further studies are required to determine the optimal chemotherapy regimen for patients with OCCC.

Furthermore, we found that the absence of residual tumor after debulking surgery was strongly associated with PFS and OS. In other types of EOC such as serous type, maximum surgical tumor reduction became the standard of care for the advanced ovarian cancer around based on previous studies [42]. Regarding OCCC, Takano et al. [42] reported that the absence of a macroscopic residual tumor was independently associated with better survival. It seems natural that maximum surgical effort is important for the treatment of OCCC because of its chemoresistance.

In our study, the complete resection rate in patients who underwent PDS increased from the pre- to the post-market period. These rates were higher than or comparable to those reported in previous studies, particularly for serous ovarian cancer [16,17,18,19,20], regardless of the pre- or post-market group (Table S1). However, the complete resection rate in patients who underwent IDS was lower than that in those who underwent PDS. This finding is likely due to the low sensitivity of OCCC to chemotherapy, which limits its ability to reduce tumor burden following neoadjuvant chemotherapy, thus hampering the achievement of complete resection.

This study had some limitations. First, the retrospective design prevented elimination of potential confounding biases in the analysis of this study. We used historical controls to compare the two treatment groups, in which there may be potential differences in surgical skills and materials and supportive care related to chemotherapy. Second, owing to the omission of central pathological assessment, there may be a degree of diagnostic imprecision, thereby compromising the accuracy of the diagnosis, even though the JGOG3017 study showed that central pathological review excluded only 6% of cases because of histological diagnosis [24]. Furthermore, this study included a relatively small number of patients compared to studies on other major cancers, owing to the rarity of OCCC. We believe that an international collaborative study can help to overcome this limitation.

In conclusion, the addition of Bev to platinum-based chemotherapy is a promising treatment strategy for advanced OCCC. Further investigation is warranted to confirm these results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We extend our sincere appreciation to T. Enomoto, H. Akashi, and K. Yoshihara from Niigata University Graduate School of Medicine and Dental Sciences; A. Iwase, T. Hirakawa, and S. Ikeda from Gunma University Hospital; and N. Yanaihara and S. Yanagida from Jikei University School of Medicine for their invaluable support. We also appreciate S. Takahashi from Jikei University School of Medicine for his statistical advice.

Footnotes

Presentation: An outline of the study was presented at the 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting. (Chicago, IL, USA, 2022, abstract e18086, oral presentation) by T. Seki.

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Conceptualization: T.S., S.T.

- Data curation: T.S., S.T.

- Formal analysis: S.T.

- Investigation: T.S., S.T., N.K., U.Y., I.M., I.S., Y.N., A.H., S.E., T.N., H.T., K.H., Y.K.

- Methodology: S.T.

- Project administration: T.S.

- Visualization: S.T.

- Writing - original draft: T.S., S.T.

- Writing - review & editing: T.S., S.T., K.H., T.H., Y.K., K.K., O.A., S.M.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Complete resection rate compared to previous study for epithelial ovarian cancer

Summary of surgical method

Sensitivity analysis for Cox model analysis with 4 variables including the factor of pre-/post-market

Sensitivity analysis for cox model analysis with 4 variables including factor of bevacizumab use

Selected adverse events in patients received bevacizumab (n=43)

Reasons of bevacizumab discontinuation (n=25)

Survival curves according to bevacizumab use in patients without residual tumor after debulking surgery.

Survival curves according to bevacizumab use in patients with residual tumor after debulking surgery.

References

- 1.del Carmen MG, Birrer M, Schorge JO. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:481–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okamoto A, Glasspool RM, Mabuchi S, Matsumura N, Nomura H, Itamochi H, et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review for clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:S20–S25. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matz M, Coleman MP, Sant M, Chirlaque MD, Visser O, Gore M, et al. The histology of ovarian cancer: worldwide distribution and implications for international survival comparisons (CONCORD-2) Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yahata T, Banzai C, Tanaka K Niigata Gynecological Cancer Registry. Histology-specific long-term trends in the incidence of ovarian cancer and borderline tumor in Japanese females: a population-based study from 1983 to 2007 in Niigata. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38:645–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter WE, 3rd, Maxwell GL, Tian C, Carlson JW, Ozols RF, Rose PG, et al. Prognostic factors for stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3621–3627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Huang H, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, Kristensen G, et al. A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2484–2496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González-Martín A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, DePont Christensen R, Graybill W, Mirza MR, et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2391–2402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iida Y, Okamoto A, Hollis RL, Gourley C, Herrington CS. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a clinical and molecular perspective. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:605–616. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tate S, Nishikimi K, Matsuoka A, Otsuka S, Shiko Y, Ozawa Y, et al. Bevacizumab in first-line chemotherapy improves progression-free survival for advanced ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:3177. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eba J, Nakamura K. Overview of the ethical guidelines for medical and biological research involving human subjects in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2022;52:539–544. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyac034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aletti GD, Dowdy SC, Podratz KC, Cliby WA. Relationship among surgical complexity, short-term morbidity, and overall survival in primary surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:676.e1–676.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Concato J, Peduzzi P, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards analysis. I. Background, goals, and general strategy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:1495–1501. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Feinstein AR, Holford TR. Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards regression analysis. II. Accuracy and precision of regression estimates. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:1503–1510. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White IR, Royston P. Imputing missing covariate values for the Cox model. Stat Med. 2009;28:1982–1998. doi: 10.1002/sim.3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagotti A, Ferrandina G, Vizzielli G, Fanfani F, Gallotta V, Chiantera V, et al. Phase III randomised clinical trial comparing primary surgery versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer with high tumour load (SCORPION trial): final analysis of peri-operative outcome. Eur J Cancer. 2016;59:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onda T, Satoh T, Ogawa G, Saito T, Kasamatsu T, Nakanishi T, et al. Comparison of survival between primary debulking surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy for stage III/IV ovarian, tubal and peritoneal cancers in phase III randomised trial. Eur J Cancer. 2020;130:114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergote I, Coens C, Nankivell M, Kristensen GB, Parmar MKB, Ehlen T, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus debulking surgery in advanced tubo-ovarian cancers: pooled analysis of individual patient data from the EORTC 55971 and CHORUS trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1680–1687. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, Jayson GC, Kitchener H, Lopes T, et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:249–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S, Pérol D, González-Martín A, Berger R, et al. Olaparib plus bevacizumab as first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2416–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Köbel M, Kalloger SE, Huntsman DG, Santos JL, Swenerton KD, Seidman JD, et al. Differences in tumor type in low-stage versus high-stage ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010;29:203–211. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181c042b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan JK, Teoh D, Hu JM, Shin JY, Osann K, Kapp DS. Do clear cell ovarian carcinomas have poorer prognosis compared to other epithelial cell types? A study of 1411 clear cell ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiyama T, Kamura T, Kigawa J, Terakawa N, Kikuchi Y, Kita T, et al. Clinical characteristics of clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a distinct histologic type with poor prognosis and resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer. 2000;88:2584–2589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiyama T, Okamoto A, Enomoto T, Hamano T, Aotani E, Terao Y, et al. Randomized phase III trial of irinotecan plus cisplatin compared with paclitaxel plus carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy for ovarian clear cell carcinoma: JGOG3017/GCIG trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2881–2887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takenaka M, Köbel M, Garsed DW, Fereday S, Pandey A, Etemadmoghadam D, et al. Survival following chemotherapy in ovarian clear cell carcinoma is not associated with pathological misclassification of tumor histotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3962–3973. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson CT, Miller R, Pemberton HN, Jones SE, Campbell J, Konde A, et al. ATR inhibitors as a synthetic lethal therapy for tumours deficient in ARID1A. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13837. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedlander ML, Russell K, Millis S, Gatalica Z, Bender R, Voss A. Molecular profiling of clear cell ovarian cancers: identifying potential treatment targets for clinical trials. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:648–654. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuroda T, Kohno T. Precision medicine for ovarian clear cell carcinoma based on gene alterations. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:419–424. doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01622-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi K, Takenaka M, Kawabata A, Yanaihara N, Okamoto A. Rethinking of treatment strategies and clinical management in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:425–431. doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01625-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gershenson DM, Okamoto A, Ray-Coquard I. Management of rare ovarian cancer histologies. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2406–2415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iida Y, Aoki K, Asakura T, Ueda K, Yanaihara N, Takakura S, et al. Hypoxia promotes glycogen synthesis and accumulation in human ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:2122–2130. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seki T, Yanaihara N, Shapiro JS, Saito M, Tabata J, Yokomizo R, et al. Interleukin-6 as an enhancer of anti-angiogenic therapy for ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2021;11:7689. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86913-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mabuchi S, Sugiyama T, Kimura T. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: molecular insights and future therapeutic perspectives. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27:e31. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mabuchi S, Kawase C, Altomare DA, Morishige K, Hayashi M, Sawada K, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2411–2422. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oza AM, Cook AD, Pfisterer J, Embleton A, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ICON7): overall survival results of a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:928–936. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00086-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SI, Kim JH, Noh JJ, Kim SH, Kim TE, Kim K, et al. Impact of bevacizumab and secondary cytoreductive surgery on survival outcomes in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian clear cell carcinoma: a multicenter study in Korea. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;166:444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komiyama S, Kato K, Inokuchi Y, Takano H, Matsumoto T, Hongo A, et al. Bevacizumab combined with platinum-taxane chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced ovarian cancer: a prospective observational study of safety and efficacy in Japanese patients (JGOG3022 trial) Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:103–114. doi: 10.1007/s10147-018-1319-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallego A, Ramon-Patino J, Brenes J, Mendiola M, Berjon A, Casado G, et al. Bevacizumab in recurrent ovarian cancer: could it be particularly effective in patients with clear cell carcinoma? Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23:536–542. doi: 10.1007/s12094-020-02446-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komazaki H, Takahashi K, Tanabe H, Shoburu Y, Kamii M, Tsuda A, et al. A retrospective study of dose-dense paclitaxel and carboplatin plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2024;35:e76. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2024.35.e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clamp A, Mcneish I, Lord R, Hall M, Essapen S, Cook A, et al. #159 ICON8B: GCIG phase III randomised trial comparing weekly dose-dense chemotherapy + bevacizumab to three-weekly chemotherapy+ bevacizumab in first-line high-risk stage III-IV epithelial ovarian cancer treatment: primary progression-free survival analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023;33:A424. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Isonishi S, Takahashi F, Michimae H, Kimura E, et al. Long-term results of dose-dense paclitaxel and carboplatin versus conventional paclitaxel and carboplatin for treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (JGOG 3016): a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1020–1026. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takano M, Kikuchi Y, Yaegashi N, Kuzuya K, Ueki M, Tsuda H, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a retrospective multicentre experience of 254 patients with complete surgical staging. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1369–1374. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Complete resection rate compared to previous study for epithelial ovarian cancer

Summary of surgical method

Sensitivity analysis for Cox model analysis with 4 variables including the factor of pre-/post-market

Sensitivity analysis for cox model analysis with 4 variables including factor of bevacizumab use

Selected adverse events in patients received bevacizumab (n=43)

Reasons of bevacizumab discontinuation (n=25)

Survival curves according to bevacizumab use in patients without residual tumor after debulking surgery.

Survival curves according to bevacizumab use in patients with residual tumor after debulking surgery.