Abstract

Purified protein derivative (PPD) skin testing is used to identify persons infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and to assess cell-mediated immune responses to Mtb. However, lack of skin induration to intradermal injection of PPD or PPD anergy is observed in a subset of patients with active tuberculosis (TB). To investigate the sensitivity and persistence of PPD reactivity and its in vitro correlates during active TB disease and after successful chemotherapy, we evaluated the distribution of skin size induration after intradermal injection of PPD among 364 pulmonary TB patients in Cambodia. A subset of 25 pulmonary TB patients who had a positive skin reaction to mumps and/or candida antigens showed persistent anergy to PPD after successful completion of TB therapy. Strikingly, in vitro stimulation of T cells from persistently anergic TB patients with mumps but not PPD resulted in T cell proliferation, and lower levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ and higher levels of IL-10 were detected in PPD-stimulated cellular cultures from PPD-anergic as compared with PPD-reactive pulmonary TB patients. These results show that anergy to PPD is antigen-specific and persistent in a subset of immunocompetent pulmonary TB patients and is characterized by antigen-specific impaired T cell proliferative responses and a distinct pattern of cytokine production including reduced levels of IL-2.

It is estimated that one third of the earth's population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB; ref. 1). Infection with Mtb results in a variety of conditions ranging from asymptomatic infection to progressive pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB and death, with approximately 10% of those infected progressing to some form of active disease during their lifetime (2, 3). TB infection is thus a significant cause of morbidity, claiming the lives of an estimated 1.7 million people globally in the year 2000 (4).

The majority of individuals infected with Mtb develop a delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response 2 to 4 weeks after infection (5), which is manifested as a positive response (skin induration) to intradermal injection with purified protein derivative (PPD) derived from Mtb. PPD or tuberculin testing is used to screen for TB infection and guide decisions about chemoprophylaxis and treatment (6). However, the interpretation of PPD results is affected by the immune status of the individual tested because conditions that interfere with generalized cell-mediated DTH responses including HIV infection, chemotherapy, steroid use, and neoplasia also interfere with reaction to PPD (7–10). Interestingly, the absence of skin reactivity to PPD has been described in immunocompetent individuals with active pulmonary TB disease (8, 11). Recently, we have shown that this anergy is persistent in a certain subset of TB patients who have been successfully cured of TB, where it is associated with IL-10-producing T regulatory (Tr1)-like cells that suppress immune responses to PPD and to nonspecific mitogens in vitro (9).

To characterize further persistent anergy in vivo in the intact human host and to investigate its in vitro correlates, we investigated the PPD-reactivity of 372 Cambodian TB patients within 2 months of diagnosis and after successful chemotherapeutic cure within the context of a community-based TB treatment program in Svay Rieng Province in the southeast of Cambodia (12). We note that the country of Cambodia in Southeast Asia is estimated to have the highest prevalence and incidence of TB globally (1). Strikingly, we found that 37% of acutely ill, HIV-1-negative, pulmonary TB patients had skin indurations of less than 10 mm in response to PPD. Moreover, after successful TB chemotherapy, a subset of 25 of these patients had persistently absent DTH to PPD but detectable DTH responses to candida and mumps antigens.

Consistent with our in vivo findings, our in vitro analyses of T cell responses of persistently PPD-anergic TB patients revealed that although they proliferated in response to mumps, they failed to proliferate in response to PPD. Furthermore, PPD-stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from PPD-anergic patients resulted in less IL-2 production as compared with PBMC from PPD-reactive TB patients. Thus, the absence of DTH to PPD does not exclude a diagnosis of pulmonary TB and, furthermore, it is persistent and antigen-specific in a certain subgroup of immunocompetent TB patients. Moreover, PPD anergy is associated with defective T cell responses including an antigen-specific impaired ability to produce IL-2 and to proliferate in response to PPD challenge.

Methods

Study Site and Subjects.

The study subjects were Cambodian patients recruited from the Cambodian Health Committee (CHC) TB treatment program in southeastern rural Cambodia (Svay Rieng Province; ref. 12). The diagnosis of clinical TB was made on the basis of medical history, physical examination, and the detection by light microscopy of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in sputum, pleural fluid, or lymph node drainage. All patients completed anti-TB chemotherapy according to the protocol of the Cambodian National TB Program: isoniazid/rifampin/pyrazinamide/ethambutol for 2 months (inpatient phase) and isoniazid/ethambutol for 6 months (outpatient phase). All patients were tested for clearance of AFB from their sputum at 2, 6, and 8 months after beginning anti-TB therapy.

TB inpatients were screened with PPD within 2 months of diagnosis and initiation of drug therapy in three district hospitals in July 1996, February 1998, January 1999, March 2000, and March 2001. After consent was obtained, 0.1 ml of Tubersol [5 tuberculin units (TU) PPD; Aventis-Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA] was injected intradermally in the forearms of TB patients and was evaluated for induration 48 h later with the ballpoint method (13). Tuberculin readings were performed by trained and experienced members of the CHC staff (S.S. and S.T.) and supervised by an infectious disease specialist (A.E.G.). Patients were classified as PPD-negative or anergic if they had no induration to PPD. All anergic patients identified during initial screenings were followed up in their home villages after successful completion of therapy on successive screening dates. These persistently anergic patients then were tested with 0.1 ml of Mumps Skin Test Antigen USP (MSTA; Aventis-Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA) and 0.1 ml of Candida Albicans Skin Test Antigen (Candin; Allermed Laboratories, San Diego) in addition to PPD; DTH was evaluated 48 h later.

Sample Collection and Serology Testing.

After consent was obtained, 30 ml of peripheral blood was drawn, and serum and PBMC were separated according to standard techniques and stored at 4°C and in liquid nitrogen, respectively. All serum samples were tested for evidence of antibodies to HIV-1 by ELISA (Sanofi Diagnostic Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquete, France).

Proliferation and Cytokine Analyses.

T cell and antigen-presenting cell (APC) fractions were isolated from cryopreserved PBMC, as described (9). Where indicated, APCs were loaded with PPD (10 μg/ml; Tuberculosis Research Materials Contract, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) or mumps antigen (1 μg/ml; Aventis-Pasteur) by incubating at 37°C for 3 h during constant end-to-end mixing. Optimal concentrations of peptide, responder:stimulator ratio, and time length of culture were established in pilot experiments with samples from healthy volunteer donors. Proliferation of T cell-specific populations was assessed by incorporation of [3H]thymidine during the last 18 h of 5-day cultures. For ELISA determination of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-10 levels (PharMingen), we collected PBMC culture supernatants at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 h after stimulation of 2 × 106 cells with 10 μg/ml PPD or 1 μg/ml mumps, which was added directly to the cell cultures.

Statistical Analysis.

Normally distributed variables were analyzed by the paired t test. Overall frequencies were compared by using a 2 × 2 Fisher exact test. We report levels of significance as P values for all experiments and comparisons. We performed all data analyses with the aid of INSTAT software (GraphPad, San Diego).

Results

Identification of PPD-Anergic Patients with Pulmonary TB in Southeastern Cambodia.

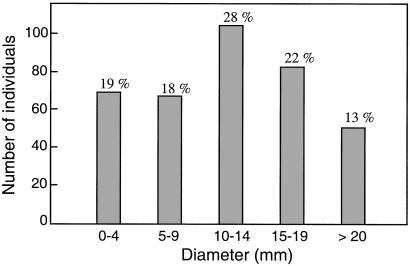

TB inpatients (372) undergoing anti-TB chemotherapy in Svay Rieng Province, Cambodia were evaluated for response to PPD in five randomly conducted screenings in July 1996, February 1998, January 1999, March 2000, and March 2001 (Table 1). All initial screenings on TB inpatients were performed within 2 months of diagnosis and the initiation of therapy. Of those screened, 364 carried the diagnosis of pulmonary TB with AFB-positive sputum, and 8 individuals had extrapulmonary TB (Table 2). Of the total 364 pulmonary TB patients who were screened for DTH to PPD, 136 (37%) had induration of less than 10 mm during initial screening; among this group, 69 patients (19%) had no detectable dermal reactivity to PPD (Fig. 1). Serologic testing to determine whether the absence of DTH response to PPD was caused by HIV-1 infection revealed that four patients who were PPD-anergic upon initial screening were HIV-1 positive (one in January 1999, two in March 2000, and one in March 2001), and they were thus excluded from the study (Table 1). All eight extrapulmonary TB patients displayed a skin reaction of greater than 10 mm. Thus, lack of DTH to PPD or a skin reaction of less than 10 mm is not a useful indicator for ruling out active pulmonary TB.

Table 1.

Persistent anergy in successfully treated patients with pulmonary TB

| Initial screening | No. patients | No. anergic patients | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 1996 | 72 | 3 | 1 persistently anergic 2 converted to PPD+ |

| February 1998 | 62 | 5 | 4 persistently anergic 1 died of PTB |

| January 1999 | 68 | 17 | 9 persistently anergic 7 converted to PPD+ 1 HIV + |

| March 2000 | 105 | 37 | 15 persistently anergic 17 converted to PPD+ 3 died of PTB 2 HIV + |

| March 2001 | 65 | 7 | 1 HIV + |

A total of 372 patients with TB were screened at five separate times for skin reaction to PPD, in three district hospitals in Svay Rieng Province, Cambodia. All anergic patients were rescreened at least two times in February 1998, January 1999, March 2000, or March 2001. Of the five anergic patients identified in February 1998, one died of massive hemoptysis after completion of treatment. Of the 17 anergic patients identified in January 1999, one tested positive for HIV-1 infection and died with clinical AIDS. Of the 37 anergic patients identified in March 2000, three died of PTB complications and two tested positive for HIV-1 infection. In March 2001, seven anergic patients were identified, one tested positive for HIV-1 infection. Sex- and age-matched PPD+ patients with TB who were PPD+ on initial screening remained PPD+ on subsequent screening (data not shown). We also note that all patients were tested for clearance of AFB from their sputum at 2, 6, and 8 months after beginning anti-TB therapy and there was no statistical difference between the time to AFB clearance between the persistently PPD-anergic patients and the PPD+ patients (data not shown). PTB, pulmonary TB.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of PPD-positive and anergic patients

| PPD-positive (n = 329) | Anergic (n = 29) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean | 47.9 ± 14.2 | 43.3 ± 14.9 | 0.08 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 120 (36.5%) | 6 (21.7%) | 0.1 |

| Female | 209 (63.5%) | 23 (79.3%) | |

| Tuberculosis | |||

| Pulmonary | 321 (97.6%) | 29 (100%) | 1.00 |

| Extrapulmonary* | 8 (2.4%) | 0 |

Four anergic patients with HIV-1 infection are not included in this analysis. Six anergic HIV-1-negative patients identified in March 2001 are currently being followed-up. Four anergic patients died and were unavailable for retesting.

Extrapulmonary cases of TB disease included 4 cases of TB of the spine (Pott's disease) and 4 cases of pleural TB.

Figure 1.

Distribution of skin test reaction sizes to PPD among 364 pulmonary TB patients in Cambodia. The numbers of individuals with the indicated size of skin induration upon initial PPD screening determined within the first 2 months of initiation of TB therapy are shown in the histograms. The numbers at the top of each bar are the percentage of subjects in each size range of the total group of 364 individuals. We note that all 69 patients under the 0–4 mm range had no induration (zero).

The four initial screenings identified 59 HIV-1-negative individuals who had no induration 48 h after intradermal injection with 5 TU PPD and were thus PPD-anergic (Table 1). Four of these individuals died of complications from pulmonary TB during therapy and were thus unavailable for PPD rescreening. Of the surviving 55 HIV-1-negative PPD-anergic TB patients identified during the four initial screenings, 26 became PPD+ upon rescreening after completion of therapy. Follow-up of the remaining 29 anergic individuals revealed that, although they had all been successfully treated and had no clinical evidence of TB, including AFB-negative sputum, they remained anergic to PPD upon rescreening in at least two separate visits (Table 1). The six HIV-1-negative PPD-anergic TB patients identified in March 2001 (Table 1) are still under treatment and will be followed up for persistent lack of DTH response to PPD after cure has been achieved. We note that analysis of the baseline characteristics including age, gender, and diagnosis of pulmonary vs. extrapulmonary TB of the PPD-reactive and PPD-anergic patients showed no statistically significant differences (Table 2). Taken together, we conclude that lack of DTH to PPD in the 29 anergic patients identified was not a transient phenomenon associated with active pulmonary TB but was persistent after successful completion of therapy, as documented by AFB-negative sputum and the absence of clinical signs or symptoms of active TB infection.

Lack of Response to PPD Is Antigen-Specific in Vivo and in Vitro in Persistently PPD-Anergic TB Patients.

To determine whether the lack of DTH to PPD in the cohort of 29 persistently PPD-anergic patients was antigen-specific, we next evaluated their DTH response to other antigens. As shown in Table 3, 25 of the 29 PPD-anergic individuals had a positive skin reaction to mumps or candida. Four PPD-anergic patients who had no clinical evidence of immunosuppression, and who remained HIV-1-negative on rescreening, also did not react to either mumps or candida (Table 3), which is consistent with the observation that reactivity to these two antigens in immunocompetent individuals is approximately 50 to 80% and 55 to 75%, respectively (7, 14). Thus, lack of DTH to PPD is antigen-specific in a certain subset of TB patients and furthermore, a positive response to control antigens is not predictive of a positive response to PPD in immunocompetent Cambodian individuals with active TB.

Table 3.

Antigen-specific anergy to PPD in a subset of pulmonary patients with TB

| PT no. | Age | Sex | PPD, mm | Mumps, mm | Candida, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | M | 0 | 9 × 10 | 8 × 8 |

| 2 | 15 | F | 0 | 20 × 34 | 5 × 5 |

| 3 | 63 | F | 0 | 27 × 20 | 15 × 13 |

| 4 | 35 | F | 0 | 5 × 8 | 8 × 12 |

| 5 | 62 | F | 0 | 7 × 7 | 6 × 6 |

| 6 | 29 | F | 0 | 5 × 5 | 14 × 11 |

| 7 | 55 | F | 0 | 5 × 5 | 21 × 22 |

| 8 | 35 | F | 0 | 10 × 8 | 10 × 8 |

| 9 | 62 | F | 0 | 7 × 5 | 5 × 5 |

| 10 | 33 | F | 0 | 5 × 5 | 6 × 6 |

| 11 | 44 | F | 0 | 5 × 6 | 5 × 5 |

| 12 | 19 | F | 0 | 5 × 6 | 10 × 9 |

| 13 | 45 | F | 0 | 20 × 20 | 0 |

| 14 | 33 | F | 0 | 8 × 12 | 0 |

| 15 | 42 | M | 0 | 0 | 4 × 6 |

| 16 | 28 | F | 0 | 0 | 7 × 9 |

| 17 | 40 | M | 0 | 0 | 13 × 14 |

| 18 | 27 | F | 0 | 0 | 7 × 8 |

| 19 | 45 | M | 0 | 0 | 9 × 9 |

| 20 | 33 | F | 0 | 0 | 5 × 5 |

| 21 | 55 | F | 0 | 0 | 8 × 8 |

| 22 | 71 | M | 0 | 0 | 13 × 14 |

| 23 | 20 | F | 0 | 0 | 5 × 5 |

| 24 | 53 | F | 0 | 0 | 9 × 13 |

| 25 | 55 | F | 0 | 0 | 6 × 8 |

| 26 | 55 | M | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 27 | 49 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | 38 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 | 65 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Twenty-nine persistently anergic patients with TB were tested with 5 tuberculin units of PPD, and 0.1 ml of mumps and candida antigens. DTH to PPD, mumps, or candida was evaluated 48 h later.

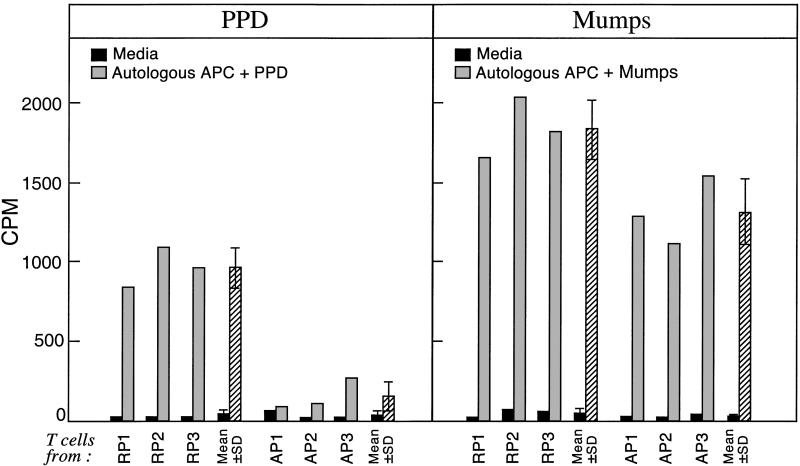

We next isolated CD4+ T cells and autologous APC from TB patients who were anergic to PPD but who had a skin reaction to mumps and from PPD+ TB patients; we measured T cell proliferation in response to PPD or mumps stimulation in vitro. Strikingly, the proliferative response of T cells from PPD-anergic TB patients to PPD was significantly reduced as compared with the response of T cells from PPD+ TB patients. By contrast, stimulation of T cells from anergic TB patients with mumps antigen resulted in proliferation, although the response to mumps was slightly lower in the anergic patients (Fig. 2). We note that we previously demonstrated that APC from PPD-anergic and PPD-responsive patients stimulate a mixed lymphocyte reaction equivalently (9). Here, by demonstrating that T cells from PPD-anergic but mumps-responsive proliferate in response to mumps, we have ruled out defective antigen presentation by APC as the cause of impaired T cell responses to PPD in anergic patients. Taken together, we conclude that the lack of antigen-specific DTH to PPD in vivo observed with skin testing is associated with an ineffective and antigen-specific clonal response of T cells in vitro.

Figure 2.

T cells from anergic TB patients do not generate a PPD-specific proliferative response but can efficiently respond to mumps stimulation. CD4+ T cells from PPD-reactive patients (RP) and persistently PPD-anergic patients (AP) were stimulated with autologous APC loaded with PPD and mumps; [3H]thymidine incorporation (cpm) was determined 5 days later. As shown in Table 3, of the 29 persistently anergic patients, 13 were reactive to mumps and were persistently not reactive to PPD. Three of these six patients were randomly chosen, and three age- and sex-matched PPD-responsive patients were chosen and studied. The results also are presented as the mean ± SD of experiments from the three different RP and the three different AP pulmonary TB patients (all experiments performed in triplicate). The optimal concentrations of antigen loading of autologous APC (10 μg/ml for PPD or 1 μg/ml for mumps) and time length of culture (5 days) were first established in control experiments with samples from healthy PPD+ and mumps+ volunteer blood donors (data not shown). Results of three representative patients are shown.

Previously, we reported that T cell receptor (TCR)-mediated stimulation of T cells from PPD-anergic patients resulted in defective phosphorylation of TCRζ and defective activation of ZAP-70 and MAPK (9), proteins that are critical for IL-2 gene transcription and protein production after antigen stimulation of T cells (15, 16). Given that the clonal expansion of T cells in response to antigen depends upon IL-2 production, we hypothesized that antigen-specific impairment of IL-2 production may play a role in PPD-anergy. Thus, we next investigated the kinetics of induction of IL-2 in PBMC from PPD-anergic and PPD-reactive TB patients after in vitro stimulation with PPD or mumps. As shown in Fig. 3, IL-2 levels were dramatically increased by PPD in PPD-reactive individuals but only minimally induced in PPD-anergic patients 24 h after stimulation. By contrast, mumps-stimulated IL-2 levels reached similar levels in cells from PPD-reactive and PPD-anergic individuals (Fig. 3). Thus, the inability of T cells to respond to PPD in vivo as measured by a negative DTH skin reaction in PPD-anergic patients is associated in vitro with lower levels of IL-2.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-10 production in PBMC from anergic and PPD+ TB patients. PBMC cultures were prepared from PPD-reactive patients (RP) and persistently PPD-anergic patients (AP) and were stimulated with 10 μg/ml of PPD or 1 μg/ml of mumps added directly to the bulk cultures. Supernatants were collected 0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 h later. The levels of IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-10 at the indicated times were assessed by ELISA. Cytokine levels are depicted as the amount of secreted cytokine in PPD-stimulated cultures minus the amount in medium alone. As shown in Table 3, of the 29 persistently anergic patients, 13 were reactive to mumps and were persistently not reactive to PPD. Four of these six patients were chosen randomly, and four age- and sex-matched PPD-responsive patients were chosen and studied. The results are presented as the mean ± SE of experiments using cells from four different PPD-responding patients (RP) and four different anergic (AP) pulmonary TB patients (all experiments performed in triplicate) at each time point. We note that in previous studies, we detected the constitutive presence of IL-10-producing Tr1-like immunosuppressive T cells and a decreased number of IFN-γ-producing T cells in PBMC from PPD-anergic patients by intracellular cytokine staining (9). We were unable to detect IL-2-producing T cells by intracellular staining (data not shown). Furthermore, we did not detect IL-4, IL-12, or TGF-β protein levels in PBMC stimulated with aqueous sonicate of Mtb (H3Rv7) as measured by ELISA (9).

After 24 h of PPD stimulation, IFN-γ production also was impaired in response to PPD, and increased levels of IL-10 were detected in cellular culture supernatants from PPD-anergic patients; these differences persisted up to 36 h after stimulation with PPD (Fig. 3). Notably, the levels of IFN-γ and IL-10 reached similar levels in mumps-stimulated PBMC from both PPD-reactive and PPD-anergic TB patients (Fig. 3). Taken together, we conclude that in addition to impaired production of IFN-γ and higher levels of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10, the inability of T cells from PPD-anergic patients to respond to PPD in vivo is associated in vitro with antigen-specific impaired T cell proliferation and production of IL-2.

Discussion

Tuberculin skin testing is the major initial screening method used to diagnose both latent and active TB infection (17). Notably, more than a third of 364 Cambodian patients with active pulmonary TB had less than a 10 mm intradermal reaction to PPD, and 19% of these patients had no detectable skin reaction. Furthermore, 86% (25/29) of persistently PPD-anergic Cambodian pulmonary TB patients had a positive skin reaction to intradermal injection of mumps or candida antigens. Taken together, we conclude that negative PPD testing is not a useful indicator for ruling out active pulmonary TB and, therefore, does not obviate the need for further microbiologic or modern nucleic acid testing when there is clinical suspicion of active TB disease. Furthermore, although positive responses to control antigens are commonly used to rule out generalized anergy and to validate a negative PPD skin test (11, 18), our results argue against the value of anergy testing with control antigens because responsiveness to other antigens was not predictive of responsiveness to PPD in our cohort (19–21).

Previously, we demonstrated that IL-10-producing T cells were constitutively present in the peripheral blood of anergic patients. Furthermore, we showed that T cell proliferation in response to PPD as well as nonspecific mitogens was significantly impaired in anergic patients, and that an anti-IL-10-neutralizing antibody resulted in the restoration of proliferation of these T cells in response to PPD or nonspecific mitogens (9). Intriguingly, T cell proliferation in response to mumps was only slightly lower than in response to PPD, which is consistent with the hypothesis that PPD and nonspecific mitogens activate an IL-10-producing PPD-responsive T cell clone that is immunosuppressive, whereas the specific mumps antigen does not. The slightly lower T cell proliferation in response to mumps is likely because of the constitutive presence of IL-10-producing T cells (9). Taken together, we conclude that PPD-anergy can be specifically induced by mycobacterial antigens in vivo in certain Mtb-infected individuals.

Notably, we have shown here that T cells from persistently PPD-anergic patients display an antigen-specific impairment of IL-2 production. Taken together with our previous results demonstrating that T cells from anergic TB patients display defective phosphorylation of TCRζ and defective activation of ZAP-70 and MAPK proteins (9), we speculate that impaired signaling through the TCR and defective activation of these early intracellular signal events of T cell activation are directly involved in PPD-induced IL-2 gene transcription and subsequent protein production. In addition to impaired IL-2 production, we also have shown here that anergic patients display antigen-specific impaired IFN-γ production and antigen-specific increased production of IL-10 in response to PPD.

DTH is generated by class II-mediated presentation of antigens to CD4+ T cells and clinical conditions that cause impaired cell-mediated immunity such as AIDS results in impaired DTH responses, negative tuberculin conversion, and an increase in clinical TB in latently infected individuals (7, 18). Although in animal models, bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccination of the host results in a reduction of the number of viable mycobacteria in the stationary phase relative to nonvaccinated hosts (22), a correlation of bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccination, PPD reactivity, and resistance to TB infection has not been demonstrated in humans (23). Here, we have characterized a group of individuals who despite active pulmonary TB followed by successful chemotherapeutic cure, display no DTH to PPD. Given that these persistently anergic TB patients have impaired clonal expansion of PPD-specific T cells, compromised production of the effector cytokines IL-2 and IFN-γ, and high levels of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10, it seems likely that they are at a disadvantage for clearing Mtb infection and at a higher risk for developing progressive TB disease. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the only four patients among the individuals screened in this study who died of TB disease were anergic to PPD upon initial screening. Moreover, one of the persistently anergic individuals had reported two previous episodes of pulmonary TB, which by history had been adequately treated, which suggests either exogenous reinfection or persistence. Long-term follow up of this cohort of patients will be necessary to determine whether lack of DTH to PPD predisposes individuals to reactivation of persistent organisms or to reinfection (24). Before effective TB chemotherapy, approximately 50% of those who developed active TB died (25). Thus, it is interesting to speculate that in the absence of TB treatment, persistently anergic patients would be at a particular disadvantage for containing TB infection and would more often fall into the group that did not survive their TB in the pretreatment era.

Previous studies have suggested that certain populations display greater resistance and that others seem to be at greater risk for both increased susceptibility to infection and progressive disease caused by Mtb. For example, the frequency of protection from TB infection in Caucasians seems to be greater compared with African-Americans (26). Other studies have demonstrated an association between the HLA class II DR2 serotype with the development of clinical TB in diverse populations including persons from India, Indonesia, Russia, and Mexico (27–30). The demonstration in Cambodia of an association between the HLA-DQB1*0503 allele and TB disease progression (31) further supports the contention that genetic factors are involved in susceptibility to developing progressive, clinical TB.

The results presented here that a certain subset of pulmonary TB patients display persistent and PPD-specific anergy strongly suggests that certain individuals have an innate genetic inability to mount an antigen-specific DTH response to PPD. Interestingly, a high incidence of PPD-anergy was demonstrated in Amazonian Yanomami TB patients, where 46% of 26 acutely ill patients had PPD skin reactions less than 10 mm (32). This finding was attributed to the recent exposure of the indigenous Yanomami population to TB infection and thus to the lack of selection pressures favoring the survival of individuals with DTH among the Yanomami population. Thus, in addition to the historical and social realities that exist in Cambodia (12, 33), it is interesting to speculate that genetic factors may have played a significant role in the severe TB epidemic currently ongoing in Cambodia. It will be of interest, therefore, to determine whether other, distinct ethnic groups have the same rate of persistent anergy among immunocompetent TB patients as we have observed in Cambodia.

Finally, this study demonstrates that community-based TB program design and implementation in an impoverished rural setting of high TB prevalence and incidence where patient follow-up is possible, even years after treatment (12), provides a model approach for providing basic knowledge about genetic and biochemical factors involved in effective immunity to Mtb. This information could provide a basis for immunotherapeutic approaches including strategies to reverse PPD-anergy that may lead to cure and eradication of TB.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Fred Rosen for critical research support, Audrey Bernfield for her support, and Dr. William Stead for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. We also thank Dominique Rousset, Christopher Dascher, Megan Murray, and Shahin Ranjbar for assistance with sample collection in Cambodia. We are deeply indebted to the TB patients in Svay Rieng who generously participated in this study and to the assistance of the Cambodian Health Committee staff, particularly Riel Sarom, without whom this study would not have been possible. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL-59838 (to A.E.G. and E.J.Y.), a grant from the American Heart Association (to A.E.G.), and by a Paul Dudley White Traveling Fellowship from Harvard Medical School (to E.Y.T.).

Abbreviations

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- TB

tuberculosis

- DTH

delayed-type hypersensitivity

- PPD

purified protein derivative

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- AFB

acid-fast bacilli

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- TCR

T cell receptor

References

- 1.Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione M C. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez S, McCabe W R. Medicine (Baltimore) 1984;63:25–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nardell E, McInnis B, Thomas B, Weidhaas S. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1570–1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612183152502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The World Health Report 2001 (2001) (W.H.O., Geneva), pp. 144–5.

- 5.Tsicopoulos A, Hamid Q, Varney V, Ying S, Moqbel R, Durham S R, Kay A B. J Immunol. 1992;148:2058–2061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S221–S247. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham N M, Nelson K E, Solomon L, Bonds M, Rizzo R T, Scavotto J, Astemborski J, Vlahov D. J Am Med Assoc. 1992;267:369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holden M, Dubin M R, Diamond P H. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1506–1509. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112302852704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boussiotis V A, Tsai E Y, Yunis E J, Thim S, Delgado J C, Dascher C C, Berezovskaya A, Rousset D, Reynes J M, Goldfeld A E. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1317–1325. doi: 10.1172/JCI9918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohn D L, Dobkin J F. AIDS. 1993;7:S195–S202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nash D R, Douglass J E. Chest. 1980;77:32–37. doi: 10.1378/chest.77.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thim S, Goldfeld A E. Curing Tuberculosis: A Manual for Developing Communities. Boston, MA: Center for Blood Research; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokal J E. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:501–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197509042931013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright P W, Crutcher J E, Holiday D B. J Fam Pract. 1995;41:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sloan-Lancaster J, Shaw A S, Rothbard J B, Allen P M. Cell. 1994;79:913–922. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boussiotis V A, Freeman G J, Berezovskaya A, Barber D L, Nadler L M. Science. 1997;278:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1376–1395. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.16141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huebner R E, Schein M F, Cauthen G M, Geiter L J, Selin M J, Good R C, O'Brien R J. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1160–1166. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.5.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slovis B S, Plitman J D, Haas D W. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283:2003–2007. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Federal Drug Administration. Federal Register. 1977;62:52709–52712. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin D P, Osmond D, Page-Shafer K, Glassroth J, Rosen M J, Reichman L B, Kvale P A, Wallace J M, Poole W K, Hopewell P C. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1982–1984. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dannenberg A M, Jr, Collins F M. Tuberculosis. 2001;81:229–242. doi: 10.1054/tube.2001.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart P D, Sutherland I, Thomas J. Tubercle. 1967;48:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Rie A, Warren R, Richardson M, Victor T C, Gie R P, Enarson D A, Beyers N, van Helden P D. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1174–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grzybowski S, Enarson D. Bull Int Union Tuberc. 1978;53:70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stead W W, Senner J W, Reddick W T, Lofgren J P. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:422–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002153220702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajalingam R, Mehra N K, Jain R C, Myneedu V P, Pande J N. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:669–676. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teran-Escandon D, Teran-Ortiz L, Camarena-Olvera A, Gonzalez-Avila G, Vaca-Marin M A, Granados J, Selman M. Chest. 1999;115:428–433. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.2.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khomenko A G, Litvinov V I, Chukanova V P, Pospelov L E. Tubercle. 1990;71:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(90)90074-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bothamley G H, Beck J S, Schreuder G M, D'Amaro J, de Vries R R, Kardjito T, Ivanyi J. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:549–555. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldfeld A E, Delgado J C, Thim S, Bozon M V, Uglialoro A M, Turbay D, Cohen C, Yunis E J. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279:226–228. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sousa A O, Salem J I, Lee F K, Vercosa M C, Cruaud P, Bloom B R, Lagrange P H, David H L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13227–13232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldfeld A E. Congressional Hunger Caucus Round Table Hearing on the Tuberculosis Emergency. United States Congress; 1994. [Google Scholar]