Abstract

Adoptive cell transfers (ACTs) constitute an emerging platform for improving the systemic delivery of nano- and microparticle systems. Macrophages (Mφ) are an attractive cell type for particle-carrying ACTs because their attachment, phagocytosis, and chemotaxis can improve pharmacokinetics and reduce off-target effects. However, little is known about how macrophage transport and function change when carrying particles of different shapes, or whether these changes can be leveraged for improving ACTs. This work investigates macrophage interactions with biodegradable spherical and discoidal particles to promote or suppress phagocytosis, respectively. Adoptively transferred macrophages with internalized spheres (Mφ-S) or surface-bound discs (Mφ-D) possessed enhanced targeted delivery to solid tumors compared to conventional free microparticle administration by 5.2-fold and exhibited distinct phenotypic profiles within the cold B16-F10 tumor microenvironment. Moreover, phenotypic changes were evaluated upon particle association by profiling the transcriptional, chromatin accessibility, and protein state. Mφ-S complexes adopted epigenetic changes and key biomarkers associated with a proinflammatory phenotype. In Mφ-D complexes, we observed a diverse chromatin and protein landscape with simultaneous upregulation of both pro- and anti-inflammatory biomarkers, suggesting functional flexibility. Our findings suggest particle shape can be used as a design parameter to influence the function of adoptive macrophage transfers without compromising their delivery performance.

Keywords: Adoptive Cell Transfer, Macrophage, Drug Delivery, Nanoparticle, Microparticle, Cancer

INTRODUCTION

Nano- and microparticle systems have revolutionized medicine by enhancing drug performance in the body through improved stabilization, controlled release kinetics, and absorption rates.1,2 However, upon systemic administration, physical and biological barriers limit their site-specific accumulation.3 In the case of cancer, injected nanoparticles perform poorly in penetrating solid tumors as only 0.7% are capable of reaching their intended target.4

As a result, adoptive cell transfers have been increasingly explored as next-generation delivery systems for particles due to the enhanced homing capabilities to diseased and inflamed tissues by carrier cells. Adoptive macrophage transfers are particularly promising because they are highly sensitive to inflammatory signals throughout the body.5–9 Additionally, their innate phagocytic capabilities make them well-poised for particle loading. Once arrived at the pathologic site, macrophages (Mφ) have the capacity to engage in therapeutic effects by adopting functional phenotypes, ranging from classical activation (M1-like), henceforth referred to as proinflammatory, to alternative activation (M2-like), henceforth referred to as anti-inflammatory.

Despite the broad interest in using macrophages to deliver particles,10–14 little is known about how particles affect their transport and function. Particles with isotropic geometries are known to undergo macrophage phagocytosis within minutes to hours, and particles with anisotropic geometries are capable of frustrating phagocytosis for days, resulting in cellular spreading along the surface of the particles due to reorganized actin structure formation.15 Previous studies have exploited the internalization of spherical particles for theranostic purposes10,12–14,16,17 or attached discoidal particles to the surfaces of macrophages to promote sustained drug release from the particles in the advent of cellular backpacks.11,18–24 However, these distinct particle shapes, and their promotion of dissimilar cellular programs, have not been studied or leveraged in adoptive macrophage transfer technologies to date.

Herein, we investigated the effect of particle shape—namely shapes that promote or resist phagocytosis—on macrophage transport and function by associating biodegradable spherical and discoidal particles without drugs, referred to as spheres and discs respectively, with primary murine macrophages. We administered the macrophages carrying spheres or discs into a B16-F10 murine melanoma model and demonstrated a ~5.2-fold enhanced tumor-homing compared to free microparticles. Interestingly, the shape of the particles did not affect the transport of the adoptive macrophage carriers. To understand whether particles of different shapes may evoke disparate genetic mechanisms in macrophages, we analyzed gene expression, chromatin accessibility, and protein biomarker expression to connect shape-induced changes to functional cell behavior. We discovered that macrophages associated with internalized spheres (Mφ-S) displayed proinflammatory phenotypes and macrophages associated with surface-bound discs (Mφ-D) displayed functionally programmed states similar to those of the foreign body response. Mφ-S prompted modest phenotypic changes relative to those of Mφ-D. We observed that macrophages adopt highly conserved phenotypes that are predictably shape-dependent, displaying significant differences in specific markers that may be exploited for therapeutic purposes.

RESULTS

Particle fabrication, characterization, and association with macrophages.

Spheres and discs were fabricated to promote or suppress phagocytosis, respectively. To enable comparison of shape only, fabrication of both particle types was optimized to engender the same effective volume (see Supporting Information), and both particles were made from poly(D,L lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), which has been widely used in FDA-approved products because it is biodegradable and biocompatible (Fig. 1A, 1B).25,26

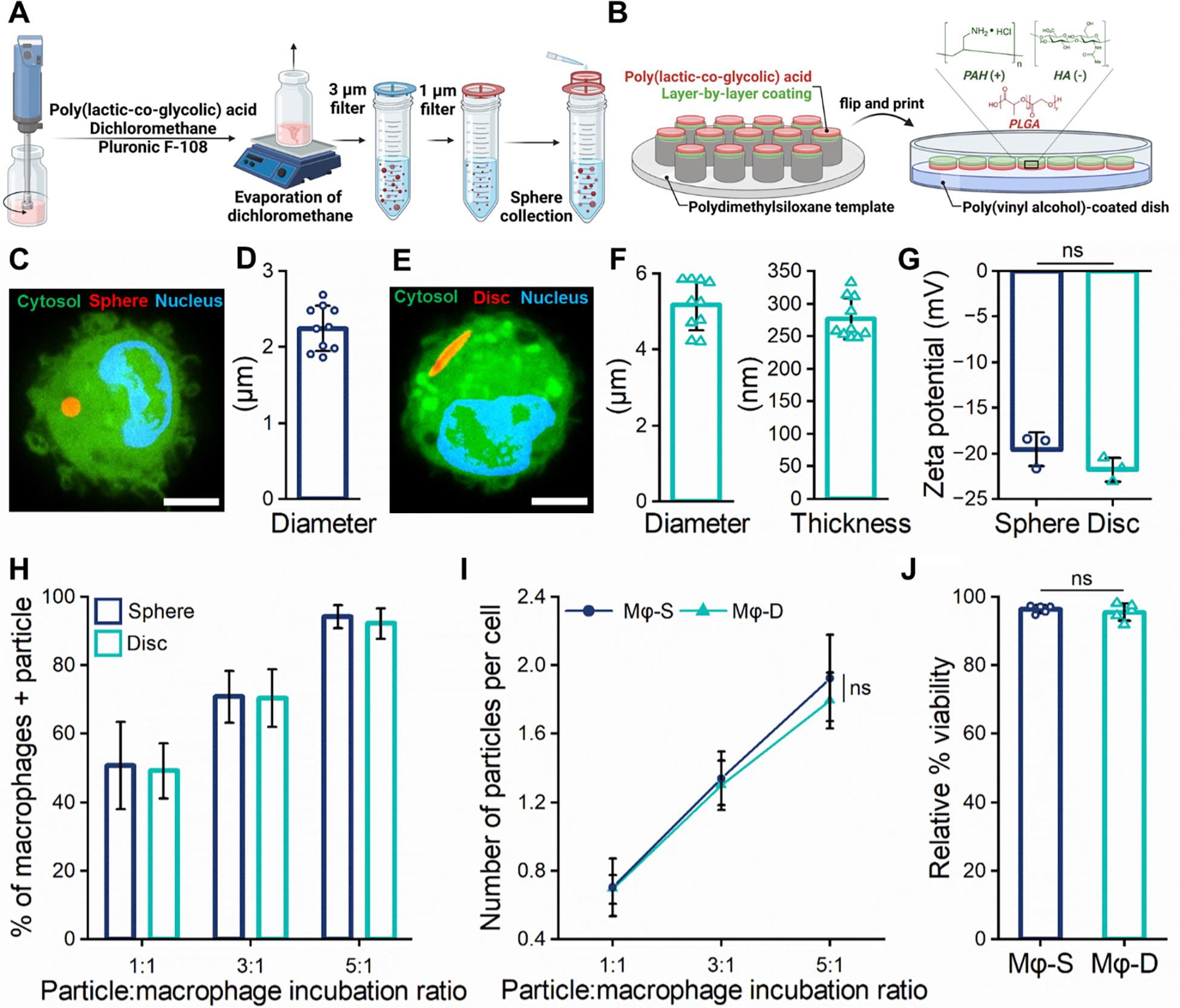

Figure 1. Design and characterization of macrophage-particle complexes.

(A) Schematic illustration of sphere fabrication via homogenization and filtration. (B) Schematic illustration of discoidal particle fabrication via microcontact printing (not to scale). PAH (polyallylamine hydrochloride) and HA (hyaluronic acid) were used via LbL coating and microcontact printing. (C) Confocal micrograph of BMDM (cytosol: green, nucleus: blue) with spherical particle (red); (scale bar: 5 μm). (D) Spherical particle diameter; (n = 10). (E) Confocal micrograph of BMDM (cytosol: green, nucleus: blue) with discoidal particle (red); (scale bar: 5 μm). (F) Disc diameter and thickness; mean ± standard deviation (SD), (n = 10). (G) Zeta potential of discoidal and spherical particles; mean ± SD, (n = 3). (H) Percentage of BMDMs associated with ≥1 particle; mean ± SD, (n ≥ 30). (I) Number of associated particles per cell after washing at a ratio of 1:1, 3:1, and 5:1 particles to cells; mean ± SD, (n ≥ 30). (J) Viability of macrophage-particle complexes measured at 24 h post-association relative to control macrophages; mean ± SD, (n = 5). (G–J) Data were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test; ns, not significant.

Spheres were prepared by homogenizing PLGA dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM) in a Pluronic F-108 solution, stirring the emulsion to evaporate DCM, and then filtering the particle suspension through 1 and 3 μm filters, saving the intermediate fraction (Fig. 1A). Spheres displayed an average diameter of 2.3 ± 0.3 μm, as determined by analysis of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs (Fig. S1A). The surface charge of spheres was −19.6 ± 1.9 mV (Fig. 1G).

Discs were fabricated from rhodamine B-conjugated PLGA with a cell-adhesive layer and printed on a sacrificial layer of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) to facilitate their release upon PVA dissolution in aqueous media (Fig. 1B). The cell-adhesive layer was made on an elastomeric polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) template through a layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly of hyaluronic acid (HA) and poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH). HA was selected to enhance binding to macrophages via CD44,27 while PAH was selected to promote electrostatic LbL coupling.11 A layer of PLGA was spin-coated onto the LbL template and microcontact-printed on a PVA-coated petri dish (Fig. S2). Discs displayed an average diameter of 5.1 ± 0.7 μm and thickness of 276 ± 32 nm, as determined by analysis of scanning electron by SEM micrographs and profilometry, respectively (Fig. 1F, S1B). The surface charge of discs was −21.8 ± 1.3 mV (Fig. 1G).

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were cultured by harvesting progenitor cells from bone marrow and differentiating into macrophages using macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF). Particle association with BMDMs was visualized using confocal microscopy (Fig. 1C, 1E). To confirm internalization of spheres and surface-binding of discs, cells were imaged using 3D projections (Fig. S3). Spheres and discs exhibited robust association with murine BMDMs that increased proportionately with particle concentration, whereby association is defined as either bound to the surfaces of cells or internalized by cells (Fig. 1H, 1I). Particles were incubated with BMDMs for 4 h in the presence of serum-free media to promote cellular interactions. Unassociated particles were removed by washing after incubation. A particle:macrophage ratio of 5:1 during incubation was used for all subsequent studies, as this ratio resulted in 94.4% and 91.9% of cells with associated spheres and backpacks, respectively (Fig. 1H). Similarly, a 5:1 particle:macrophage ratio resulted in nearly identical association ratios between particle types, resulting in 1.9 internalized spheres per macrophage and 1.8 surface-bound discs per macrophage (Fig. 1I). Neither particle formulation adversely impacted the viability of macrophages, as determined by a 24 h time point MTT assay when BMDMs were incubated with a 5:1 ratio of each particle type (Fig. 1J).

Spherical and discoidal particles do not inhibit cellular tumor infiltration.

In vivo transport of adoptive macrophage transfers was assessed in a B16-F10 (B16) murine melanoma model. B16 is a poorly immunogenic model of cancer;28 therefore, cellular accumulation in the tumor would support the use of an adoptive macrophage transfer platform for particle delivery. BMDMs were stained with VivoTrack 680, and B16 tumor-bearing mice were infused intraveneously (i.v.) in the lateral tail vein with 1×106 VivoTrack 680-stained BMDMs without particles (Mφ), BMDMs with internalized spheres (Mφ-S), or BMDMs with surface-bound discs (Mφ-D) (Fig. 2A). B16 tumors presented no significant volume differences between administered sample groups, and all mice steadily gained weight over the course of tumor growth (Fig. S4A, 4B).

Figure 2. Adoptive macrophage-particle complex biodistribution and phenotypes within B16-F10 tumors in vivo.

(A) Schematic illustration of the timeline for biodistribution studies following i.v. sample administration as well as tumor dissociation studies following intratumoral sample administration in mice bearing B16-F10 tumors. (B) Tumor accumulation for free particles and adoptively transferred macrophages; mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), (n = 8 mice per group). (C) Percent of accumulation per gram of tissue of free spherical microparticles (gray), Mφ (tan), Mφ-S (navy), or Mφ-D (teal) after 72 h. Accumulation (%) per organ was calculated as a fraction of the total detected organ accumulation; mean ± SEM, (n = 8 mice per group). (D) Phenotype of adoptively transferred Mφ (tan), Mφ-S (navy), or Mφ-D (teal) 72 h after intratumoral injection into B16-F10 tumors. Bar graphs indicate the fold-change in the median expression of biomarkers (CD80, MHCII, iNOS, Arg1) relative to their expression in injected Mφ; mean ± SEM, (n ≥ 100,000 events per data point); (n = 4 mice per group). (B-C) Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s Test; *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, (D) Data were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

After 72 h, mice were euthanized and the major organs (i.e., lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, brain, heart, tumor) were homogenized, processed, and fluorescently inspected to quantitatively assess BMDM biodistribution. Using organ-specific calibration curves to account for fluorescence detection and variation in tissue composition (see Supporting Methods), our findings revealed that 8.7 ± 2.3% of the injected dose per gram of tissue (ID/g) of unmodified Mφ infiltrated B16 tumors, compared to 6.0 ± 2.1% ID/g of Mφ-S and 7.6 ± 1.5% ID/g of Mφ-D; however, no significant differences were detected between these three groups (Fig. 2B). In addition, we quantified the biodistribution of i.v. infused spherical microparticles in B16 tumor-bearing mice. Each major organ was mechanically dissociated and microparticle accumulation was enumerated using flow cytometry (Fig. S5). We found that 1.3 ± 0.4% ID/g of freely administered microparticles accumulated in tumor tissue. This work suggests that Mφ, Mφ-S, and Mφ-D, on average can infiltrate tumors ~5.2-fold more specifically than free particles under these conditions. An alternative way to interpret delivery efficiency is without normalization by tissue mass (%ID), and we demonstrate BMDMs can home to tumors with a 12-fold enhancement relative to free particles (Fig. S6). The majority of BMDMs in each sample group accumulated in the spleen, which is consistent with previous reports.5,20 Accumulation in the lungs, spleen, kidneys, brain, heart, and tumor were not significantly affected by particle type. However, differences in liver accumulation were significant, with 20.5 ± 2.6% ID/g accumulation for Mφ-D compared to 12.8 ± 2.2% ID/g for Mφ and 10.3 ± 1.9% ID/g for Mφ-S. The accumulation of adoptive macrophages in the liver remained considerably lower than the corresponding values for free microparticles (50.5 ± 7.6% ID/g), potentially reducing off-target effects and limiting unwanted accumulation in non-target organs. The observed brain accumulation (~3.2 %ID/g) is expected to represent spheres trapped within the cerebral vasculature rather than true blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, as the microparticle size (1 – 3 μm) exceeds the paracellular transport limitations of an intact BBB. Additionally, flow cytometry detection of brain dissociate may be confounded by autofluorescence given the lipid-rich nature of brain tissue. Accumulation of macrophage-particle complexes was qualitatively confirmed with histological sectioning of the liver, spleen, and B16 tumor of fluorescent particles compared to saline-treated controls in a separate animal study (Fig. S7).

After demonstrating that adoptively transferred macrophages migrate to B16 tumors and particle association does not inhibit macrophage transport, we sought to evaluate their phenotype within B16 tumors. VivoTrack 680-stained Mφ, Mφ-S, or Mφ-D were injected intratumorally and the B16 tumors were chemically dissociated 72 h later (Fig. 2A). Flow cytometric analysis of VivoTrack 680+ adoptive macrophages revealed that particle shape significantly influences functional polarization in vivo; hierachical gating schema can be found in the Supporting Information (Fig. S8). While no significant differences were observed in CD80 (p = 0.090 for Mφ-S relative to Mφ), major histocompatibility complex II (MHCII) (p = 0.088 for Mφ-D relative to Mφ), or arginase 1 (Arg1), Mφ-S and Mφ-D presented significantly higher inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression compared to Mφ. Although spheres and discs can respectively promote and suppress phagocytosis, both geometries demonstrate similar potency in triggering proinflammatory activation in vivo. The lack of significant difference in iNOS expression between Mφ-S and Mφ-D suggests that the presence of a particle inside or on the surface of the cell provides sufficient stimulus to drive functional activation even in the immunosuppressive B16 tumor microenvironment. Remarkably, these functional differences were observed from particle shape alone (no drug),29 suggesting a capacity for epigenetic reprogramming by engineered particles.30,31

Mφ-S complexes adopt a proinflammatory chromatin landscape and transcriptional state.

These findings prompted us to further map shape-dependent macrophage polarization through comprehensive in vitro studies to ultimately design cell-based therapies where particles are strategically loaded with drugs that synergize with shape-dependent activation. We studied how particle shape influences transcription and chromatin accessibility within macrophages by applying RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-Seq), respectively. Epigenetic modifications act as key regulators of gene expression in macrophages upon nanoparticle stimulation.30 Therefore, ATAC-Seq is useful to enable mapping of chromatin accessibility landscapes and identification of active regulatory elements (i.e., promoters) that drive the altered gene expression measured from RNA-Seq. We performed RNA-Seq and ATAC-Seq on untreated Mφ, Mφ-S, and Mφ-D 4 h after particle association.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of normalized reads showed that samples cluster by condition, indicating global transcriptomic and chromatin accessibility differences (Fig. 3A, 4A). Mφ and Mφ-S clustered closely, suggesting that Mφ-S adopts a profile similar to untreated BMDMs, contrasting with the distinctive profile of Mφ-D—likely a response to particle shape. This stems from our understanding that macrophages are programmed to phagocytose senescent cells and foreign microbes. High aspect ratio particles, such as discoids, are known to interfere with macrophage phagocytosis, and we hypothesize that this mechanical frustraction drives pronounced epigenetic shifts relative to Mφ and Mφ-S.

Figure 3. Transcriptomic evaluation of macrophages associated with spherical or discoidal particles in vitro.

(A) Principal component analysis of global transcriptomic profile of Mφ, Mφ-S, and Mφ-D. Each point represents one independent replicate. Axes represent the percent of variance explained by the respective principal components (PC1, PC2); (n = 4). (B) Volcano plots of gene expression associations with pairwise sample group comparisons. Genes of interest are labeled. Threshold for adjusted p value was 0.05. For each volcano plot, data from the former group was normalized by the reference condition in the latter; for example, Mφ-S vs. Mφ indicates the differential gene expression of Mφ-S is normalized to that of Mφ. Therefore, a positive binary logarithm represents gene upregulation in the Mφ-S condition compared to Mφ, but conversely, a negative value represents downregulation. (C) Pathway overrepresentation enrichment analysis results for differentially expressed genes between sample conditions. Generated using Enrichr, focusing on the MSigDB Hallmark 2020 database. The color scale represents the transition from high (orange) to low (blue) values of significance. (D) Violin plots comparing aggregate expression distribution of genes related to M1-like and M2-like phenotypes of macrophages. (A-D) Data were analyzed using generalized linear models as implemented in the DESeq2 R package. Significant associations were identified at a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted false discovery rate (FDR) of ≤ 5%.

Figure 4. Chromatin accessibility evaluation of macrophages associated with spherical or discoidal particles in vitro.

(A) Principal component analysis of global accessibility profile of Mφ, Mφ-S, and Mφ-D. Each point represents one independent replicate. Axes represent the percent of variance explained by the respective principal components (PC1, PC2); (n = 4). (B) Volcano plots of differentially accessible chromatin regions with pairwise sample group comparisons. Genes of interest are labeled. Threshold for adjusted p value was 0.05. For each volcano plot, data from the former group was normalized by the reference condition in the latter; for example, Mφ-S vs. Mφ indicates the differential gene expression of Mφ-S is normalized to that of Mφ. Therefore, a positive binary logarithm represents gene upregulation in the Mφ-S condition compared to Mφ, but conversely, a negative value represents downregulation. (C) Pathway overrepresentation enrichment analysis results for upregulated differentially accessible peaks between sample conditions. Generated using Enrichr, focusing on the MSigDB Hallmark 2020 database. The color scale represents the transition from high (pink) to low (blue) values of significance. (D) Correlation plots of significantly shared genes in RNA-Seq and ATAC-Seq analyses. Colored points indicate regions overlapping known promoter regions. (A-D) Differential peak analysis was performed using the csaw R package. Significant associations were identified at a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted FDR of ≤ 5%.

We compared differential gene expression and chromatin accessibility profiles between all sample group combinations (Fig. 3B, 4B). We also screened for differentially regulated genes between sample groups for overrepresented biological pathways. We observed 4,836 differentially expressed genes (3,204 up and 1,632 down) and 1,875 differentially accessible regions (1,049 up and 826 down) in Mφ-S vs. Mφ (Fig. 3B, 4B, Table S1–S2). The magnitude of change was modest, but revealed significant increases in proinflammatory genes. For example, we observed increased gene expression and chromatin accessibility of Tlr2, H2-M2, and Jag1 alongside proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., Tnf, Ccl3, Cxcl10). Genes and accessible regions from sphere internalization enriched pathways associated with TNFα signaling via the NF-κB and inflammatory response pathways, among others (Fig. 3C, 4C, S9A, S10A). The aggregate expression of M1-associated genes for Mφ-S relative to Mφ was significant, but there were no significant differences for M2-associated genes (Fig. 3D). Differentially expressed genes measured from RNA-Seq had 17.2% overlap with differentially accessible regions from ATAC-Seq, and genes significant in both datasets demonstrated a correlation of 0.78 between effect sizes (Fig. 4D). Overall, the epigenetic changes observed in Mφ-S are representative of a classical proinflammatory state, though the magnitude of downstream gene expression differs between particle shapes, with Mφ-D showing greater M1-associated gene expression compared to Mφ-S. Therefore, both particle shapes activate similar proinflammatory pathways, but the distinct physical properties may influence the strength of the transcriptional response. This type of inflammatory response occurs when tissue-resident macrophages defend the body against microbial pathogens, promote an inflammatory microenvironment, and actively recruit additional immune cells to the site via secreted chemokines.

Mφ-D complexes adopt a mixed chromatin landscape and transcriptional state.

We observed 11,197 differentially expressed genes (5,959 up and 5,238 down) and 11,369 differentially accessible regions (5,721 up and 5,648 down) in Mφ-D vs. Mφ (Fig. 3B, 4B, Table S3–S4). The magnitude of change for the Mφ-D vs. Mφ comparison revealed significant changes in proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes. Notably, inflammation-related (e.g., Irf1, Tnf, Il6) and glycolytic (e.g., Slc2a6, Hk2, Eno2) signatures were induced. While this indicates a potent inflammatory polarization, anti-inflammatory markers (e.g., Cd36, Egr2, Tgm2) along with oxidative phosphorylation metabolic markers (i.e., Hmox1) were also epigenetically activated. Genes and accessible regions from Mφ-D enriched pathways associated with TNFα signaling via the NF-κB, IL-2/STAT5 signaling, inflammatory response as well as anti-inflammatory pathways, such as heme metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 3C, 4C, S9B, S10B). The aggregate expression of both M1- and M2-associated genes was significantly higher in Mφ-D compared to Mφ and Mφ-S (Fig. 3D). Notably, Mφ-D exhibited a complex activation state characterized by concurrent pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression, with greater enrichment of M1-associated genes. This mixed phenotype represents a nuanced cellular response that defies simple categorization and presents itself as a versatile cell-particle pairing across disease microenvironments. Differentially expressed genes overlapped with differentially accessible regions by 38.8% and genes significant in both datasets demonstrated a correlation of 0.84 between effect sizes (Fig. 4D). While this observed phenotype fails to fit neatly into a simple proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory category, the epigenetic changes in BMDMs with surface-bound discs are strikingly similar to a foreign body reaction. During the foreign body response, blood monocytes and tissue-resident macrophages accumulate at the surface of the foreign body. Because these foreign materials frustrate phagocytosis, an acute inflammatory phase proceeds, ultimately leading to fibrous encapsulation.32,33 This appears to be analogous to macrophage interactions with discs because they concomitantly present elevated levels of genes associated with pro- and anti-inflammatory activation.

Epigenetic changes in Mφ-D and Mφ-S reveal functional divergence.

Direct comparison between Mφ-D vs. Mφ-S revealed 10,601 differentially expressed genes (5,497 up and 5,104 down) and 10,217 differentially accessible regions (5,113 up and 5,104 down) (Fig. 3B, 4B, Table S5–S6). Pathways associated with inflammatory signaling were more enriched for Mφ-D, similarly to the Mφ-D vs. Mφ comparison (Fig. 3C, 4C, S9C, S10C). There were likewise significantly higher M1-associated and M2-associated gene aggregates for Mφ-D compared to Mφ-S (Fig. 3D). Differentially expressed genes overlapped with differentially accessible regions by 38.5% and genes significant in both datasets demonstrated a correlation of 0.84 between effect sizes (Fig. 4D). Because macrophage polarization directly affects key functional attributes, including phagocytic capacity34,35 and the expression of chemokine receptors36 and integrin molecules37—all of which are key functions for use in adoptive macrophage transfers—we focused on analyzing genes involved in these processes. Understanding how particle shape impacts extravasation and tissue homing may be leveraged for treatment of certain diseases to enhance the efficacy of macrophages as therapeutic delivery vehicles.

We observed epigenetic upregulation in Mφ-S relative to Mφ-D for genes related to phagocytosis (e.g., Trpv2, Rac1, P2ry6), cytoskeletal regulation (e.g., Myo1g, Sh3bp1), and chemotaxis (e.g., Cxcr3). Trpv2 is critical for macrophage particle recognition,38 while the GTPase Rac1 coordinates cytoskeletal rearrangements for efficient phagocytic uptake.39,40 Meanwhile, the upregulation of cytoskeletal regulators like Myo1g and Sh3bpl in Mφ-S suggests potential alterations in actin dynamics.41–43 Myo1g encodes a myosin motor protein that interacts with actin filaments to regulate membrane remodeling, while Sh3bpl is a cytoskeleton-associated protein that can modulate actin polymerization. Phagocytosis and clearance of internalized particles is dependent on precisely orchestrated cytoskeletal elements. Cytoskeletal regulators like Myo1g and Sh3bp1 may enhance the ability to engulf and degrade foreign microparticles, potentially improving particle clearance and subsequent antigen presentation. The change in expression in this set of genes is likely the result of spherical particle phagocytosis, similar to the recognition, engulfment, and priming that would occur against invading microorganisms and apoptotic cells. Optimizing these functional regulators can be crucial for therapeutic applications as efficient phagocytosis and immune priming are essential in cancer immunotherapies and vaccines for infectious disease. Additionally, Cxcr3 encodes for CXC motif chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3), suggesting Mφ-S could be particularly effective in diseases secreting CXCL9/10/11 (see Discussion).44

Meanwhile, we observed increased epigenetic activation in Mφ-D relative to Mφ-S for Piezo1 as well as several genes related to migration, such as Ccr5 and Cxcr4, Plau, and Icam1. It has been shown that discoidal particles can induce a mechanical force on dendritic cells (DCs) which subsequently initiates the opening of ion channels;45 this aligns with our finding that in response to disc surface binding, the mechanically activated Ca2+ ion channel Piezo1 is epigentically activated. This was also evident by the significant enrichment in PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, a pathway associated with F-actin dynamics (Fig. S9C). Given that discs cause cellular spreading along the surfaces of the particles,15 and cell shape is known to play a deterministic role in regulating macrophage activation,46,47 we ascribe the inflammatory activation of Mφ-D to the high aspect ratio of the particle. Because phagocytosis is dependent on the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, we qualitatively assessed F-actin structures by confocal microscopy (Fig. S11). We observed that BMDMs formed filopodia containing tight bundles of long actin filaments covering the cellular membrane upon particle association. These findings corroborate our epigenetic results, whereby association of both particle types stimulated actin reorganization. Additionally, the migration-associated genes Ccr5 and Cxcr4 respectively encode for CC motif chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) and CXC motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4). This indicates Mφ-D may be encouraged to home to tissues where CCL3/4/5 and CXCL12 are abundant (see Discussion).44,48 Furthermore, Plau encodes for the urokinase plasminogen activator and Icam1 encodes for intercellular adhesion molecule 1, which regulate cell-endothelium adhesion and subsequent tissue invasion.49,50 Because macrophage attachment to the endothelium and subsequent extravasation is mediated by chemokine receptors and integrins, Mφ-D may have compensated for their reduced available surface area for ligand binding—due to disc association—to preserve their migratory properties, which could explain why Mφ-D accumulated in B16 tumors to a greater extent than Mφ-S (N.B., these differences were not statistically significant).

Particle shape alters macrophage protein expression.

To assess the effect of spheres and discs on macrophage polarization, we evaluated the relative expression of proinflammatory biomarkers (CD86, CD40, MHCII, and iNOS) and anti-inflammatory biomarkers (Arg1 and CD206) after BMDMs were associated with particles and cultured for three days (Fig. 5A). Cells were harvested every 24 h, stained, and analyzed for biomarker expression by flow cytometry. This extended time frame permitted ample protein expression, whereas we focused on a 4 h time point for RNA-Seq and ATAC-Seq to capture immediate epigenetic modifications.

Figure 5. Proteomic evaluation of macrophages associated with spherical or discoidal particles in vitro.

(A) BMDMs were cultured for three days with spherical particles (navy lines) or discoidal particles (teal lines). Representative flow cytometry plots of cellular expression for M1 biomarkers (CD86, CD40, MHCII, iNOS) and M2 biomarkers (CD206, Arg1) relative to control Mφ with no particles associated and comparisons between Mφ-S and Mφ-D. Plots are defined by a binary logarithmic change in expression; mean ± SD, (n ≥ 10,000 events per data point); (n = 3). Flow cytometry analyses were carried out using FlowJo V10.10. (B) Cytokine secretion from Mφ-S (left three columns) and Mφ-D (right three columns) after three days. Heatmap columns show data as a binary logarithmic change in secretion compared to the average value of control Mφ with no particles associated and between Mφ-S and Mφ-D (n = 3). (A, B) Data were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 with respect to untreated control macrophages; #p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001 when comparing Mφ-S to Mφ-D.

Relative to untreated Mφ, Mφ-S interactions were subtle and complemented the modest changes in gene expression and chromatin accessibility we observed with RNA-Seq and ATAC-Seq. Mφ-S demonstrated a significant increase followed by a gradual decline in CD86, MHCII, and iNOS. Interestingly, Arg1 expression increased, dropped below baseline, and peaked after 3 days. CD206 had no significant changes across all days. CD40 expression also remained near that of control BMDMs. Mφ-D, on the other hand, demonstrated a significant increase followed by a gradual decline in CD86, MHCII, iNOS, CD206, and Arg1 expression over three days. CD86 was downregulated after 3 days while CD206 and MHCII returned to near baseline. Arg1 and iNOS remained significantly higher than baseline. Mφ-D also demonstrated significantly decreased CD40 expression relative to control BMDMs.

As macrophages have multifaceted roles in disease pathology through the coordinated secretion of cytokines that may drive inflammation and promote tissue growth, the characterization of soluble mediators released from the macrophage-particle complexes can provide critical insight into macrophage cellular activation states as well as downstream impacts on the local tissue microenvironment. To identify the cytokines that were produced in response to particle association, BMDM culture supernatant was contemporaneously collected along with cell samples for flow cytometry analysis over three days and analyzed by a multiplexed bead-based ELISA. In general, we observed that initial particle association on Day 1 triggered substantial changes in cytokine secretion followed by a modest decrease on Day 2 and exhibited the highest levels three days post-association (Fig. 5B). Mφ-S generally elicited low levels of cytokine secretion, but significant increases in IL-6, IL-23, IFNβ, TNFα, and GM-CSF were still observed. Chemokines levels remained largely unchanged across Mφ-S except for significant increases in CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL2 as well as decreases in CCL22 and CXCL10. CCL2 and CCL5 can be particularly useful in maintaining an inflammatory microenvironment by chemoattracting monocytes,51 natural killer cells,52 DCs,53 T cells,54 B cells,55 basophils,56 and myeloid-derived suppressor cells57, where sustained immune cell recruitment is necessary to prevent disease progression (e.g., tumor growth, chronic infection).

In contrast, Mφ-D elicited more potent cytokine secretion with significant increases in IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-23, IFNβ, and TNFα, enhancing cytotoxic activity. Chemokine production was also enhanced for CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CXCL1, and CXCL2. CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5 have the potential to attract additional immune cells, such as monocytes, T cells, DCs, and natural killer cells,58–61 while CXCL1 and CXCL2 mediate neutrophil recruitment.62,63 These chemokine axes suggest that Mφ-D could be beneficial in inititating an anti-tumor immune response. Meanwhile, we observed significant decreases in the secretion of ICAM-1, CCL2, CCL22, and CXCL10. Expanded cytokine analysis from cell media is included in the Supporting Information (Fig. S12). These proteomic findings suggest a temporal pattern in which the association of different particle shapes produces distinct cytokine milieus that may be useful for orchestrating programmed therapeutic outcomes for certain disease scenarios.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that BMDMs associated with internalized spheres and surface-bound discs can serve as drug delivery vehicles by homing to sites of inflammation and adopting distinct and conserved phenotypes. Spheres and discs possessed the same effective volume, and the association of either particle shape did not induce cytotoxic effects. In this work, we selected macrophages as the delivery vector due to their high tumor-infiltrating capacity.64 We show that coupling spherical or discoidal particles to BMDMs does not encumber their transport to nonimmunogenic B16-F10 melanomas as a model tumor. Biodistribution analysis using a quantitative fluorescence-based homogenization method revealed that 8.7 ± 2.3% ID/g of unmodified BMDMs infiltrated B16 tumors, compared to 6.0 ± 2.1% ID/g for Mφ-S and 7.6 ± 1.5% ID/g for Mφ-D, with no significant differences between groups. Mφ-S and Mφ-D exhibited a ~5.2-fold higher tumor specificity than free microparticle administration. This fold-change could potentially be enhanced further through the systemic administration of clodronate to deplete endogenous blood monocytes and resident macrophages, thereby reducing the competition for tumor infiltration and maximizing the accumulation of adoptive macrophages.65,66 Additionally, within the cold B16 tumor microenvironment, we observed that macrophages exhibit distinct polarization states based on particle shape alone. In particular, Mφ-S and Mφ-D showed significant upregulation of proinflammatory marker, iNOS, compared to untreated Mφ even in the absence of immunomodulatory factors. The potential of particle-based adoptive macrophage transfers lies in the ability of particles to be loaded with therapeutic payloads;11,19–21 macrophages can carry particles deep into the tumor microenvironment and reprogram tumor-associated immune states.

While previous studies have characterized macrophage responses to spherical67–71 and discoidal particles made from PLGA,11,20,21,72,73 this work represents a head-to-head comparison using multiomics approaches. Our findings are consistent with previous reports demonstrating that particle geometry can induce distinct macrophage phenotypes, with high aspect ratio particles eliciting more pronounced cellular responses, likely due to frustrated phagocytosis. When profiling the transcriptome, epigenome, and proteome, we investigated functional changes driven by particle association with primary BMDMs. Mφ-S adopted a modest canonical inflamed phenotype, characterized by changes to proinflammatory epigenetic markers (e.g., Tnf, Ccl3, Nlrp3), protein biomarker expression (e.g., MHCII, CD86, iNOS), and cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-1β, GM-CSF). Mφ-D assumed a more dramatic and coordinated phenotype related to both pro- and anti-inflammatory states, which is a functional reprogramming state similar to the foreign body response. The integrative analysis of epigenetic (e.g., Irf1, Eno2, Cd36), protein biomarker expression (e.g., Arg1, MHCII, iNOS), and cytokine secretion (e.g., TNFα, IL-6, CCL3) changes revealed that Mφ-D complexes also adopt a unique cell state associated with the suppression of phagocytosis. Interestingly, while our in vitro studies demonstrated complex phenotypic signatures for both particle shapes, our in vivo data demonstrated selective persistence of iNOS signaling for Mφ-S and Mφ-D within cold B16 tumors. The narrowing phenotypic response reflects the influence of tumor-derived immunosuppressive factors that may dampen certain signaling pathways while others persist due to the association of the particle itself. Future work involves evaluating the phenotypic response in other murine melanoma model (e.g., YUMM1.7, HCmel1274, Cloudman S91). Such studies would provide critical insights into the therapeutic potential of adoptive macrophage transfers for particle delivery across diverse models with varying degrees of immunogenicity. This study ultimately underscores the plasticity of macrophages and their ability to assume specialized phenotypes, which begs the question of what other types of physical cues can drive distinct functional states.74,75

Taken together, our findings provide a pathway to rationally select particle shape as a means to regulate the transcription and translation of certain sets of genes and proteins that may aid in the functional performance of adoptive macrophage transfers. One may rationally select a macrophage-particle pairing that can benefit specific therapeutic use cases; rather than pairing a particle shape with macrophages based on phagocytic capacity alone, researchers should also consider cellular tropism, particle-induced activation states, and disease-specific factors.

By way of example, Mφ-S could be particularly useful for pathogen clearance during infection or tumor suppression in cancer as the cell assumes a proinflammatory phenotype. Mφ-S upregulates Cxcr3, and the CXCR3-CXCL9/10/11 axis is found in certain cancers (e.g., melanoma,76–79 colorectal,80 breast,81–83 ovarian84,85, renal cell carcinoma86) and infectious diseases87–89. After arrival at the pathologic site, Mφ-S causes expression of CD86 and MHCII which could contribute to a broad adaptive immune response via antigen presentation, generation of reactive species via iNOS expression, and secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, and CCL5 to promote an inflammatory microenvironment. On the other hand, Mφ-D functions are versatile and could be beneficial in resolving a wide array of immune responses. They could be applied to cancer treatment due to upregulation of proinflammatory signals, or used to address chronic inflammation or autoimmune diseases through the expression of anti-inflammatory signals. Mφ-D upregulates Ccr5 and Cxcr4. The CCR5-CCL3/4/5 axis can be applied to targeting multiple sclerosis,90,91 HIV,92 viral infections,93–96 and COVID.97 Meanwhile, the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis can be targeted to autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis,98–100 lupus nephritis101) and various cancers (e.g., breast,102 prostate,103 ovarian,104 glioblastoma105). Mφ-D can stimulate inflammation through iNOS expression and the secretion of IL-6, TNFα, type I interferons, and various chemokines. However, it may also suppress inflammation through the expression of Arg1 to promote T cell suppression87 and CD206 to clear pathogenic or apoptotic cells. The activation properties of either particle shape could potentially work synergistically with existing therapeutic agents, offering opportunities to enhance drug efficacy through coordinated cell-particle engagement.

CONCLUSION

Nano- and microparticle systems consistently present poor pathologic site-specific accumulation. By leveraging the natural homing abilities of macrophages and taking into consideration the effect of particle type on macrophage activation states, we propose shape-informed macrophage-based delivery systems for specific disease applications. It is important to note that while a certain particle shape may be more beneficial for specific diseases, there is often overlap in their efficacy across pathologies. A certain shape does not necessitate pairing with a certain disease, rather cell-particle interactions may have effects to consider when looking at the disease state. For example, researchers should consider the interplay between particle properties (i.e., composition, association location, drug release kinetics), cellular activation state, potential off-target side effects, and the heterogeneity of the diseased tissue microenvironments. This work can assist in establishing criteria for selecting a cell-particle pairing that expresses a specific phenotype beneficial for a certain disease state. Although our dataset contains multiple complementary elements, there are limitations regarding mechanistic evidence of the particle shape on phenotype. We suggest further interrogation of epigenetics to study cell-particle interactions coupled with protein-based assays. Additionally, whether the concordant macrophage genomic and proteomic changes due to particle association might influence the immune microenvironment once arrived at the pathological site warrants further scientific investigation. Taken together, our findings create a new framework for engineering macrophage-particle complexes as an ACT modality.

METHODS

Sphere fabrication.

Spheres were prepared by homogenization. Briefly, PLGA (38 – 54 kDa, 25 mg) with Nile Red (1 mg mL−1 in methanol, 200 μL) was dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM, 400 μL) by vortexing. A solution of 1% w/v poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(propylene glycol)-block-poly(ethylene glycol) (Pluronic F-108, PEG-PPG-PEG; ~14.6 kDa) in deionized water (DIW) was prepared. Then, 1 vol.% F-108 solution (7.25 mL) was added to the fluorescent PLGA solution and homogenized for 1 min using a high shear homogenizer at 30,000 rpm. The homogenized solution was stirred for 3 h at 300 rpm to evaporate the DCM. The spheres were filtered through a 3 μm filter to remove particles greater than 3 μm, and the filtrate was then passed through a 1 μm filter to remove particles below 1 μm in diameter. Milli-Q ultrapure water was backwashed through the 1 μm filter to obtain spheres of 1 to 3 μm. The spheres were washed twice in Milli-Q water by centrifugation at 12,000xG for 10 min and stored at −20°C until needed.

Disc fabrication.

Discs were fabricated following techniques similar to those previously described.11 Briefly, poly(dimethyl siloxane) (PDMS) templates were prepared by soft lithography to generate a series of 10 μm wide hexagonal posts. PDMS templates were LbL-coated with aqueous solutions of HA and PAH prepared in 150 mM NaCl. A 4% w/v of PLGA in chloroform was prepared from a 100:1 weight ratio of nonfluorescent PLGA to rhodamine B-conjugated PLGA. LbL-coated PDMS templates were spin-coated with the PLGA solution (300 μL) at 1,000 rpm for 15 s. Petri dishes were coated with 3% w/v PVA in DIW and dried. PDMS stamps with deposited PLGA were microcontact printed onto the PVA-coated dishes to collect material from top of the posts only. Discs were collected by washing PVA dishes with DIW. Detailed fabrication and characterization methods are described in Supporting Information.

Mouse care and experimentation.

Male wild type C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Animal research was performed at the University of Colorado Boulder under the protocol approved for this study by the University of Colorado Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol 2836) in accordance with guidelines from the National Institutes of Health (USA).

Bone marrow isolation.

Progenitor cells were isolated from murine bone marrow, as described previously.106 Healthy 6 to 8-week-old male C57BL/6 were sacrificed via CO2 overdose and cervical dislocation. Sterile surgical scissors were used to extract the tibias, femurs, and humeri. Bones were immersed in 70% ethanol twice followed by a thorough rinse with PBS. After rinsing, the bones were placed in a separate PBS solution. Using a 21G needle, microcentrifuge tubes (500 μL) were punctured through the bottom multiple times. In a sterile environment, epiphyses of each bone were cut and bones were added to each punctured tube (2 bones per tube). The microcentrifuge tubes (500 μL) were placed inside microcentrifuge tubes (1.5 mL) and centrifuged at 20,000xG for 30 s to flush bone marrow cells. Bone marrow pellets were resuspended in of Gey’s balanced salt solution (1 mL), passed through a 40 μm cell strainer, and centrifuged at 400xG for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in Bambanker and stored in cryovials in liquid nitrogen until needed.

BMDM culture.

Frozen bone marrow was thawed and mixed with 4°C bone marrow media (BMM-) (i.e., 500 mL DMEM F12, 50 mL heat-inactivated (HI)-fetal bovine serum (FBS), 25 mL of 200 mM GlutaMAX, 5 mL PenStrep). The solution was centrifuged at 400xG for 10 min at 4°C, aspirated, cells were resuspended in BMM+ (i.e., BMM- supplemented with 20 ng mL−1 of M-CSF). Approximately 5×106 bone marrow cells were added to a non-treated tissue culture T175 flask containing BMM+ (25 mL). Cells were incubated and left undisturbed at 37°C and 5% CO2 for three days. Additional BMM+ media (25 mL) was added to the flask on Day 3 and left to incubate for four additional days. BMDMs were extracted and seeded into non-treated tissue culture 12-well plates at a concentration of 0.25×106 cells per well, and incubated under standard conditions for 24 h.

Particle association with BMDMs.

Spheres and discs were thawed and centrifuged at 12,000xG and 3,000xG, respectively, for 10 min at 4°C and resuspended in serum-free BMM- (i.e., BMM- sans HI-FBS). Media was exchanged for BMDMs cultured in 12-well plates from BMM+ to serum-free BMM-. Both particle types were counted separately on a hemocytometer and the corresponding amount of each particle type was added to separate wells (obtaining a 1:1, 3:1, or 5:1 ratio of particles:cells). Well plates were centrifuged at 300xG for 8 min to promote contact between the particles and adherent BMDMs then incubated at standard conditions for 4h. Unassociated excess particles were washed away by aspirating the media, washing twice with dPBS, and resuspending with BMM+.

Tumor model establishment.

An orthotopic B16-F10 murine melanoma model was established in mice. Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and inoculated with 0.5×106 B16-F10 cells (>95% viability) in saline (100 μL) by subcutaneous injection into the lower right hind flank with a 26-gauge needle. The tumor size was measured every two days via caliper measurements and the tumor volume was calculated using the equation , where is the smaller of the two caliper measurements. Body weight was contemporaneously measured with the tumor volume. Detailed methods are described in Supporting Information.

Quantitative biodistribution analysis of VivoTrack 680 fluorescence.

Quantitative methods of biodistribution detection were adapted from methods similar to those described previously.107 We developed a homogenization-based biodistribution method using VivoTrack 680 (Perkin Elmer) to quantify cellular infiltration across major organs. VivoTrack 680 is a lipophilic, near-infrared dye that can intercalate into cellular membranes. Once stained, cells can be injected in vivo, whereafter mice can be sacrificed, their organs removed and processed by homogenization, and biodistribution can be quantitatively assessed after dye extraction using a series of VivoTrack 680 standard curves and measured extraction efficiencies.

We first established the fluorescence saturation of dye within cells by using a fixed number of 6×104 BMDMs and staining with VivoTrack 680 serial dilutions in 1x PBS per instructions from the manufacturer. Cells were lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100 on a shaker at 150 rpm for 60 min. Fluorescence was inspected on an Infinite® M Plex (Table S7) and saturation was determined by identifying where the linear region of the calibration curve diminished (Fig. S13). The optimal dye concentration of 0.242 ug of VivoTrack 680 was determined for 6×104 BMDMs. Next, we developed VivoTrack 680 standard curves for each major organ tissue extract (i.e., lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, brain, heart, tumor) by tissue homogenization, rapid centrifugation, and fluorophore recovery. To obtain organ tissue extract, euthanized mice were dissected and whole organ tissues were processed via homogenization (see Extraction of VivoTrack 680 from organ tissues). Organ-specific calibration curves were generated by serially diluting a stock solution of VivoTrack 680 in the respective tissue extracts (Fig. S14).

Finally, to validate the accuracy of our biodistribution method, we conducted recovery experiments by introducing 0.1×105 VivoTrack 680-stained BMDMs into homogenization tubes containing different whole organ tissues. Organs with VivoTrack 680-stained BMDMs were then homogenized and harvested for tissue extract. Initial results revealed incomplete cell recovery, necessitating the development of organ-specific extraction efficiencies—or, the ratio of known VivoTrack 680 concentration in an organ and the detected value, accounting for chemical differences across organs (Table S8). Bootstrap analysis determined that ten replicates provided optimal statistical power for determining the extraction efficiencies, as the standard deviation stabilized beyond this sample size (Fig. S15). These extraction efficiencies can be subsequently applied to calculate the actual number of infiltrating cells in each organ. Fluorescence measurements were conducted in a CellStar® Clear 96-Well, Cell Culture-Treated, Flat-Bottom Microplate (Greiner Bio-One™) at an excitation of 676 nm and emission of 708 nm. Detailed biodistribution calculations are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Intravenous injections.

Tumor-bearing mice received a single intravenous infusion of saline, Mφ (106), Mφ-S (106), or Mφ-D (106) through the tail vein 13 days after inoculation. In all groups, injection volumes were 100 μL, and macrophages were suspsended in saline. Prior to injection, macrophage-particle complexes were labeled with VivoTrack 680, a near-infrared dye. Mice were euthanized by CO2 overdose and cervical dislocation 72 h after i.v. injection for biodistribution studies.

Extraction of VivoTrack 680 from organ tissues.

Organs were harvested from euthanized mice and weighed. Each organ was placed in a screw cap tube (2 mL) with one 5 mm diameter stainless steel bead from Omni International (Kennesaw, GA) and methanol (250 μL). Large organs were divided into multiple tubes as necessary. Organs were then homogenized using a Fisherbrand™ Bead Mill 24 Homogenizer (Waltham, MA) for 5 min. The homogenate was then centrifuged at ~20,000xG for 15 min. The supernatant was aspirated into a new tubes, and the volume of each organ tissue extract was estimated. VivoTrack 680 fluorescence of the extracted solution was measured, and total VivoTrack 680 accumulation was calculated for each organ using the standard curves (Fig. S14) and extraction efficiencies (Table S8) described above.

Tissue dissociation and microparticle enumeration.

Organs were harvested from euthanized mice and weighed. Each organ was placed in a screw cap tube (50 mL) with PBS (5 mL) and mechanically dissociated with a pestel. The dissociate was transferred into a 40 μm cell strainer and pushed through with a syringe plunger. The collected solution was diluted in PBS and a fixed amount (60 μL) was subjected to inspection by flow cytometry. Microparticles were distinguished from tissue components by gating, particle counts were determined based on events within the defined gate (Fig. S5), and total accumulation was adjusted for by the dilution factor.

Tumor dissociation and phenotyping.

B16-F10 tumors were established in mice as described above. Tumor-bearing mice received a single intratumoral infusion of Mφ (106), Mφ-S (106), or Mφ-S (106) using the particle association ratios describe earlier. Tumors were then dissociated as previously described.108 Briefly, B16 tumors were harvested and placed in a 24-well plate with tumor digestion media (2 mL). Tumor digestion medium composed of BMM- with 1 mg mL−1 collagenase D and 0.09 mg mL−1 DNase. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 60 min with orbital shaking. The solutions were transferred into a 40 μm cell strainer and pushed through with a syringe plunger. The collected solution was centrifuged at 400xG for 10 min at 4°C. Solution was then resuspended in stain buffer and separated using a F4/80+ cell selection kit (Stem Cell). Each sample underwent three rounds of magnetic separation. F4/80+ cells were counted, divided into four aliquots, and stained with fluorescent anti-CD11b, anti-CD80, anti-MHCII, anti-iNOS, anti-Arg1 antibodies.

Bulk ATAC-Seq.

BMDMs were incubated with spherical or discoidal particles for 4 h. Upon completion of particle association and washing of unassociated particles, Mφ-S and Mφ-D as well as control Mφ were subjected to bulk ATAC-Seq. Cells were counted for viability using trypan blue exclusion. Cells achieved a viability of ≥ 95%. After the cells were counted, 50,000 viable cells were used for ATAC-seq, while the remaining cells were reserved for RNA extraction and sequencing described below. New England Biolabs NEBNext Library Quant Kit for Illumina was substituted for the KAPA Library Quantification Kit, and libraries were normalized to 10 nM. Sequencing at a minimum depth of 40 million reads was performed by the Genomics Shared Resource at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System (Illumina Inc.). Differential accessibility analysis between groups was performed by annotating peaks to gene regions with the ChIPseeker R package.109,110 Pathway overrepresentation enrichment analysis was performed using the Enrichr web interface111–113 and the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) mouse hallmark gene set collection database.114–116 Detailed analytical methods are described in the Supporting Information.

Bulk RNA-Seq.

Cells remaining after ATAC-Seq were subjected to bulk RNA-Seq to allow for profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in the same cell culture well. mRNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy Kit with optional DNase digestion, quantified using a Qubit fluorometer, and RNA integrity number (RIN) was obtained using Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Sequencing was performed by the Genomics Shared Resource at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System using the TruSeq RNA Library Prep kit. Samples were sequenced at a minimum depth of 40 million reads. Differential expression analysis between groups was performed using the DESeq2 R package. Significant differentially expressed genes were tested for pathway overrepresentation using Enirchr and MSigDB. Detailed analytical methods are described in the Supporting Information.

In vitro immunophenotyping.

BMDMs were incubated with spherical or discoidal particles for 24, 48, or 72 h. Upon completion of particle association and washing of unassociated particles, media was collected for multiplexed ELISA, while Mφ, Mφ-S, and Mφ-D were collected, stained, and subjected to inspection by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with either a panel of fluorescent anti-CD86, anti-CD40, anti-MHCII, and anti-CD206 antibodies or permeabilized and stained with a panel of fluorescent anti-iNOS and anti-Arg1 antibodies (Table S9). Detailed methods are provided in the Supporting Information.

In vitro multiplexed bead-based ELISA.

Media collected from each experimental group prior to flow cytometry was analyzed using a custom 23-Plex ProcartaPlex™ Panel. Briefly, supernatant sample (25 μL) was incubated with the bead mix and washed multiple times using a magnetic handheld plate washer. Then, 1x detection antibody mixture (25 μL) was added to each sample and incubated for 30 min. Each sample was diluted with streptavidin phycoerythrin (50 μL) and incubated for 30 min. Samples were analyzed with a MAGPIX instrument (Luminex). Standard curves for each cytokine were generated (Fig. S16).

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses and data visualization were performed using OriginPro 2024 software and R 4.3.1. Data presentation, sample sizes, and statistical methods are indicated in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Prof. Corrella S. Detweiler, Dr. Edward M. C. Courvan, Taylor R. Ausec, for helpful discussions as well as Katie A. Trese for assistance with collecting discoidal particle thickness measurements, Collin C. Kemper for assistance with bootstrapping, Dr. Joseph Dragavon for helpful discussion on imaging complexes. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R35GM147455). Additional support by the NIH/CU Interdisciplinary Bioengineering Research Training in Diabetes Program (T32 5T32DK120520-5), NIH (R21CA267608), and the Office of Naval Research (ONR N000142212541) is acknowledged. C.W.S. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences, supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts. C.W.S. would like to thank the Packard Foundation for their support of this project. The authors also recognize the BioFrontiers Institute Advanced Light Microscopy Core (RRID: SCR_018302), the Colorado Shared Instrumentation in Nanofabrication and Characterization (RRID: SCR_018985), and the Flow Cytometry Shared Core (S10ODO21601) at the University of Colorado Boulder. Spinning disc confocal microscopy was performed on a Nikon Ti-E microscope supported by the BioFrontiers Institute and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Some of the figures in this article were made using BioRender.com.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Mitchell MJ; Billingsley MM; Haley RM; Wechsler ME; Peppas NA; Langer R Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20 (2), 101–124. 10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kohane DS Microparticles and Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2007, 96 (2), 203–209. 10.1002/bit.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Blanco E; Shen H; Ferrari M Principles of Nanoparticle Design for Overcoming Biological Barriers to Drug Delivery. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33 (9), 941–951. 10.1038/nbt.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wilhelm S; Tavares AJ; Dai Q; Ohta S; Audet J; Dvorak HF; Chan WCW Analysis of Nanoparticle Delivery to Tumours. Nat Rev Mater 2016, 1 (5), 16014. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Combes F; Mc Cafferty S; Meyer E; Sanders NN Off-Target and Tumor-Specific Accumulation of Monocytes, Macrophages and Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells after Systemic Injection. Neoplasia 2018, 20 (8), 848–856. 10.1016/j.neo.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Muthana M; Rodrigues S; Chen Y-Y; Welford A; Hughes R; Tazzyman S; Essand M; Morrow F; Lewis CE Macrophage Delivery of an Oncolytic Virus Abolishes Tumor Regrowth and Metastasis after Chemotherapy or Irradiation. Cancer Research 2013, 73 (2), 490–495. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zambito G; Mishra G; Schliehe C; Mezzanotte L Near-Infrared Bioluminescence Imaging of Macrophage Sensors for Cancer Detection In Vivo. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.867164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Liao X; Gong G; Dai M; Xiang Z; Pan J; He X; Shang J; Blocki AM; Zhao Z; Shields IV CW; Guo J Systemic Tumor Suppression via Macrophage-Driven Automated Homing of Metal-Phenolic-Gated Nanosponges for Metastatic Melanoma. Advanced Science 2023, 10 (18), 2207488. 10.1002/advs.202207488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Park KS; Gottlieb AP; Janes ME; Prakash S; Kapate N; Suja VC; Wang LL-W; Guerriero JL; Mitragotri S Adoptively Transferred Macrophages for Cancer Immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2025, 13 (5), e010437. 10.1136/jitc-2024-010437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Tylek T; Wong J; Vaughan AE; Spiller KL Biomaterial-Mediated Intracellular Control of Macrophages for Cell Therapy in pro-Inflammatory and pro-Fibrotic Conditions. Biomaterials 2024, 308, 122545. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Shields CW; Evans MA; Wang LL-W; Baugh N; Iyer S; Wu D; Zhao Z; Pusuluri A; Ukidve A; Pan DC; Mitragotri S Cellular Backpacks for Macrophage Immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6 (18), eaaz6579. 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Evans MA; Shields CW; Krishnan V; Wang LL; Zhao Z; Ukidve A; Lewandowski M; Gao Y; Mitragotri S Macrophage‐Mediated Delivery of Hypoxia‐Activated Prodrug Nanoparticles. Adv. Therap. 2020, 3 (2), 1900162. 10.1002/adtp.201900162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Evans MA; Huang P-J; Iwamoto Y; Ibsen KN; Chan EM; Hitomi Y; Ford PC; Mitragotri S Macrophage-Mediated Delivery of Light Activated Nitric Oxide Prodrugs with Spatial, Temporal and Concentration Control. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9 (15), 3729–3741. 10.1039/C8SC00015H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wang Y; Zhang L; Liu Y; Tang L; He J; Sun X; Younis MH; Cui D; Xiao H; Gao D; Kong X-Y; Cai W; Song J Engineering CpG-ASO-Pt-Loaded Macrophages (CAP@M) for Synergistic Chemo-/Gene-/Immuno-Therapy. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2022, 11 (15), 2201178. 10.1002/adhm.202201178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Champion JA; Mitragotri S Role of Target Geometry in Phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103 (13), 4930–4934. 10.1073/pnas.0600997103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Xue F; Zhu S; Tian Q; Qin R; Wang Z; Huang G; Yang S Macrophage-Mediated Delivery of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetothermal Therapy of Solid Tumors. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 629, 554–562. 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.08.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ausec TR; Carr LL; Alina TB; Day NB; Goodwin AP; Shields CWI Combination of Chemical and Mechanical Tumor Immunomodulation Using Cavitating Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024. 10.1021/acsanm.4c03005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kapate N; Liao R; Sodemann RL; Stinson T; Prakash S; Kumbhojkar N; Chandran Suja V; Wang LL-W; Flanz M; Rajeev R; Villafuerte D; Shaha S; Janes M; Park KS; Dunne M; Golemb B; Hone A; Adebowale K; Clegg J; Slate A; McGuone D; Costine-Bartell B; Mitragotri S Backpack-Mediated Anti-Inflammatory Macrophage Cell Therapy for the Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury. PNAS Nexus 2023, pgad434. 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kapate N; Dunne M; Kumbhojkar N; Prakash S; Wang LL-W; Graveline A; Park KS; Chandran Suja V; Goyal J; Clegg JR; Mitragotri S A Backpack-Based Myeloid Cell Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120 (17), e2221535120. 10.1073/pnas.2221535120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kapate N; Dunne M; Gottlieb AP; Mukherji M; Suja VC; Prakash S; Park KS; Kumbhojkar N; Guerriero JL; Mitragotri S Polymer Backpack-Loaded Tissue Infiltrating Monocytes for Treating Cancer. Advanced Healthcare Materials n/a (n/a), 2304144. 10.1002/adhm.202304144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Day NB; Orear CR; Velazquez-Albino AC; Good HJ; Melnyk A; Rinaldi-Ramos CM; Shields CW IV Magnetic Cellular Backpacks for Spatial Targeting, Imaging, and Immunotherapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023. 10.1021/acsabm.3c00720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wang LL-W; Gao Y; Chandran Suja V; Boucher ML; Shaha S; Kapate N; Liao R; Sun T; Kumbhojkar N; Prakash S; Clegg JR; Warren K; Janes M; Park KS; Dunne M; Ilelaboye B; Lu A; Darko S; Jaimes C; Mannix R; Mitragotri S Preclinical Characterization of Macrophage-Adhering Gadolinium Micropatches for MRI Contrast after Traumatic Brain Injury in Pigs. Science Translational Medicine 2024, 16 (728), eadk5413. 10.1126/scitranslmed.adk5413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Klyachko NL; Polak R; Haney MJ; Zhao Y; Gomes Neto RJ; Hill MC; Kabanov AV; Cohen RE; Rubner MF; Batrakova EV Macrophages with Cellular Backpacks for Targeted Drug Delivery to the Brain. Biomaterials 2017, 140, 79–87. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Anselmo AC; Gilbert JB; Kumar S; Gupta V; Cohen RE; Rubner MF; Mitragotri S Monocyte-Mediated Delivery of Polymeric Backpacks to Inflamed Tissues: A Generalized Strategy to Deliver Drugs to Treat Inflammation. Journal of Controlled Release 2015, 199, 29–36. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Xu Y; Kim C-S; Saylor DM; Koo D Polymer Degradation and Drug Delivery in PLGA-Based Drug-Polymer Applications: A Review of Experiments and Theories. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2017, 105 (6), 1692–1716. 10.1002/jbm.b.33648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Lü J-M; Wang X; Marin-Muller C; Wang H; Lin PH; Yao Q; Chen C Current Advances in Research and Clinical Applications of PLGA-Based Nanotechnology. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2009, 9 (4), 325–341. 10.1586/erm.09.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Huang G; Huang H Application of Hyaluronic Acid as Carriers in Drug Delivery. Drug Deliv 2018, 25 (1), 766–772. 10.1080/10717544.2018.1450910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lechner MG; Karimi SS; Barry-Holson K; Angell TE; Murphy KA; Church CH; Ohlfest JR; Hu P; Epstein AL Immunogenicity of Murine Solid Tumor Models as a Defining Feature of in Vivo Behavior and Response to Immunotherapy. J Immunother 2013, 36 (9), 477–489. 10.1097/01.cji.0000436722.46675.4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kumbhojkar N; Prakash S; Fukuta T; Adu-Berchie K; Kapate N; An R; Darko S; Chandran Suja V; Park KS; Gottlieb AP; Bibbey MG; Mukherji M; Wang LL-W; Mooney DJ; Mitragotri S Neutrophils Bearing Adhesive Polymer Micropatches as a Drug-Free Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2024, 1–14. 10.1038/s41551-024-01180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Italiani P; Della Camera G; Boraschi D Induction of Innate Immune Memory by Engineered Nanoparticles in Monocytes/Macrophages: From Hypothesis to Reality. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Fukuta T; Kumbhojkar N; Prakash S; Shaha S; Silva-Candal AD; Park KS; Mitragotri S Immunotherapy against Glioblastoma Using Backpack-Activated Neutrophils. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine n/a (n/a), e10712. 10.1002/btm2.10712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Saleh LS; Amer LD; Thompson BJ; Danhorn T; Knapp JR; Gibbings SL; Thomas S; Barthel L; O’Connor BP; Janssen WJ; Alper S; Bryant SJ Mapping Macrophage Polarization and Origin during the Progression of the Foreign Body Response to a Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogel Implant. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2022, 11 (9), 2102209. 10.1002/adhm.202102209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Barone DG; Carnicer-Lombarte A; Tourlomousis P; Hamilton RS; Prater M; Rutz AL; Dimov IB; Malliaras GG; Lacour SP; Robertson AAB; Franze K; Fawcett JW; Bryant CE Prevention of the Foreign Body Response to Implantable Medical Devices by Inflammasome Inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119 (12), e2115857119. 10.1073/pnas.2115857119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Shapouri-Moghaddam A; Mohammadian S; Vazini H; Taghadosi M; Esmaeili S-A; Mardani F; Seifi B; Mohammadi A; Afshari JT; Sahebkar A Macrophage Plasticity, Polarization, and Function in Health and Disease. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233 (9), 6425–6440. 10.1002/jcp.26429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wynn TA; Chawla A; Pollard JW Macrophage Biology in Development, Homeostasis and Disease. Nature 2013, 496 (7446), 445–455. 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Nieto M; Frade JMR; Sancho D; Mellado M; Martinez-A C; Sánchez-Madrid F Polarization of Chemokine Receptors to the Leading Edge during Lymphocyte Chemotaxis. Journal of Experimental Medicine 1997, 186 (1), 153–158. 10.1084/jem.186.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Brown EJ Integrins of Macrophages and Macrophage-Like Cells. In The Macrophage as Therapeutic Target; Gordon S, Ed.; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; pp 111–130. 10.1007/978-3-642-55742-2_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Link TM; Park U; Vonakis BM; Raben DM; Soloski MJ; Caterina MJ TRPV2 Has a Pivotal Role in Macrophage Particle Binding and Phagocytosis. Nat Immunol 2010, 11 (3), 232–239. 10.1038/ni.1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Mishra AK; Rodriguez M; Torres AY; Smith M; Rodriguez A; Bond A; Morrissey MA; Montell DJ Hyperactive Rac Stimulates Cannibalism of Living Target Cells and Enhances CAR-M-Mediated Cancer Cell Killing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120 (52), e2310221120. 10.1073/pnas.2310221120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hoppe AD; Swanson JA Cdc42, Rac1, and Rac2 Display Distinct Patterns of Activation during Phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell 2004, 15 (8), 3509–3519. 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Dart AE; Tollis S; Bright MD; Frankel G; Endres RG The Motor Protein Myosin 1G Functions in FcγR-Mediated Phagocytosis. J Cell Sci 2012, 125 (Pt 24), 6020–6029. 10.1242/jcs.109561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Schlam D; Bagshaw RD; Freeman SA; Collins RF; Pawson T; Fairn GD; Grinstein S Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Enables Phagocytosis of Large Particles by Terminating Actin Assembly through Rac/Cdc42 GTPase-Activating Proteins. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8623. 10.1038/ncomms9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ito T; Nakamura R; Sumimoto H; Takeshige K; Sakaki Y An SH3 Domain-Mediated Interaction between the Phagocyte NADPH Oxidase Factors P40phox and P47phox. FEBS Lett 1996, 385 (3), 229–232. 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Jacquelot N; Duong CPM; Belz GT; Zitvogel L Targeting Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors in Melanoma and Other Cancers. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2480. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Yu H; Liu Z; Guo H; Hu X; Wang Y; Cheng X; Zhang LW; Wang Y Mechanoimmune-Driven Backpack Sustains Dendritic Cell Maturation for Synergistic Tumor Radiotherapy. ACS Nano 2024. 10.1021/acsnano.4c08701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).McWhorter FY; Wang T; Nguyen P; Chung T; Liu WF Modulation of Macrophage Phenotype by Cell Shape. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110 (43), 17253–17258. 10.1073/pnas.1308887110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Jain N; Vogel V Spatial Confinement Downsizes the Inflammatory Response of Macrophages. Nature Mater 2018, 17 (12), 1134–1144. 10.1038/s41563-018-0190-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Oberlin E; Amara A; Bachelerie F; Bessia C; Virelizier JL; Arenzana-Seisdedos F; Schwartz O; Heard JM; Clark-Lewis I; Legler DF; Loetscher M; Baggiolini M; Moser B The CXC Chemokine SDF-1 Is the Ligand for LESTR/Fusin and Prevents Infection by T-Cell-Line-Adapted HIV-1. Nature 1996, 382 (6594), 833–835. 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Fleetwood AJ; Achuthan A; Schultz H; Nansen A; Almholt K; Usher P; Hamilton JA Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Is a Central Regulator of Macrophage Three-Dimensional Invasion, Matrix Degradation, and Adhesion. J Immunol 2014, 192 (8), 3540–3547. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Bui TM; Wiesolek HL; Sumagin R ICAM-1: A Master Regulator of Cellular Responses in Inflammation, Injury Resolution, and Tumorigenesis. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2020, 108 (3), 787–799. 10.1002/JLB.2MR0220-549R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Matsushima K; Larsen CG; DuBois GC; Oppenheim JJ Purification and Characterization of a Novel Monocyte Chemotactic and Activating Factor Produced by a Human Myelomonocytic Cell Line. J Exp Med 1989, 169 (4), 1485–1490. 10.1084/jem.169.4.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Allavena P; Bianchi G; Zhou D; van Damme J; Jílek P; Sozzani S; Mantovani A Induction of Natural Killer Cell Migration by Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-1, −2 and −3. Eur J Immunol 1994, 24 (12), 3233–3236. 10.1002/eji.1830241249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Zhu K; Shen Q; Ulrich M; Zheng M Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells Expressing Both Chemotactic Cytokines IL-8, MCP-1, RANTES and Their Receptors, and Their Selective Migration to These Chemokines. Chin Med J (Engl) 2000, 113 (12), 1124–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Carr MW; Roth SJ; Luther E; Rose SS; Springer TA Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 Acts as a T-Lymphocyte Chemoattractant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91 (9), 3652–3656. 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Frade JM; Mellado M; del Real G; Gutierrez-Ramos JC; Lind P; Martinez-A C Characterization of the CCR2 Chemokine Receptor: Functional CCR2 Receptor Expression in B Cells. J Immunol 1997, 159 (11), 5576–5584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Conti P; Pang X; Boucher W; Letourneau R; Reale M; Barbacane RC; Thibault J; Theoharides TC Impact of Rantes and MCP-1 Chemokines on in Vivo Basophilic Cell Recruitment in Rat Skin Injection Model and Their Role in Modifying the Protein and mRNA Levels for Histidine Decarboxylase. Blood 1997, 89 (11), 4120–4127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Huang B; Lei Z; Zhao J; Gong W; Liu J; Chen Z; Liu Y; Li D; Yuan Y; Zhang G-M; Feng Z-H CCL2/CCR2 Pathway Mediates Recruitment of Myeloid Suppressor Cells to Cancers. Cancer Letters 2007, 252 (1), 86–92. 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Schaller TH; Batich KA; Suryadevara CM; Desai R; Sampson JH Chemokines as Adjuvants for Immunotherapy: Implications for Immune Activation with CCL3. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017, 13 (11), 1049–1060. 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1384313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Liu JY; Li F; Wang LP; Chen XF; Wang D; Cao L; Ping Y; Zhao S; Li B; Thorne SH; Zhang B; Kalinski P; Zhang Y CTL- vs Treg Lymphocyte-Attracting Chemokines, CCL4 and CCL20, Are Strong Reciprocal Predictive Markers for Survival of Patients with Oesophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2015, 113 (5), 747–755. 10.1038/bjc.2015.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Allen F; Bobanga ID; Rauhe P; Barkauskas D; Teich N; Tong C; Myers J; Huang AY CCL3 Augments Tumor Rejection and Enhances CD8+ T Cell Infiltration through NK and CD103+ Dendritic Cell Recruitment via IFNγ. OncoImmunology 2018, 7 (3), e1393598. 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1393598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Hugues S; Scholer A; Boissonnas A; Nussbaum A; Combadière C; Amigorena S; Fetler L Dynamic Imaging of Chemokine-Dependent CD8+ T Cell Help for CD8+ T Cell Responses. Nat Immunol 2007, 8 (9), 921–930. 10.1038/ni1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Sawant KV; Poluri KM; Dutta AK; Sepuru KM; Troshkina A; Garofalo RP; Rajarathnam K Chemokine CXCL1 Mediated Neutrophil Recruitment: Role of Glycosaminoglycan Interactions. Sci Rep 2016, 6 (1), 33123. 10.1038/srep33123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).De Filippo K; Dudeck A; Hasenberg M; Nye E; van Rooijen N; Hartmann K; Gunzer M; Roers A; Hogg N Mast Cell and Macrophage Chemokines CXCL1/CXCL2 Control the Early Stage of Neutrophil Recruitment during Tissue Inflammation. Blood 2013, 121 (24), 4930–4937. 10.1182/blood-2013-02-486217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Adebowale K; Guerriero JL; Mitragotri S Dynamics of Macrophage Tumor Infiltration. Applied Physics Reviews 2023, 10 (4), 041402. 10.1063/5.0160924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]