Summary

Adjuvant chemotherapy and immune checkpoint blockade exert quite durable anti-tumor responses, but the lack of effective biomarkers limits the therapeutic benefits. Utilizing multi-cohorts of 3,095 patients with gastric cancer, we propose an attention-enhanced residual Swin Transformer network to predict chemotherapy response (main task), and two predicting subtasks (ImmunoScore and periostin [POSTN]) are used as intermediate tasks to improve the model’s performance. Furthermore, we assess whether the model can identify which patients would benefit from immunotherapy. The deep learning model achieves high accuracy in predicting chemotherapy response and the tumor microenvironment (ImmunoScore and POSTN). We further find that the model can identify which patient may benefit from checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. This approach offers precise chemotherapy and immunotherapy response predictions, opening avenues for personalized treatment options. Prospective studies are warranted to validate its clinical utility.

Keywords: chemotherapy response, multitask Swin Transformer, medical imaging, tumor microenvironment, immunotherapy

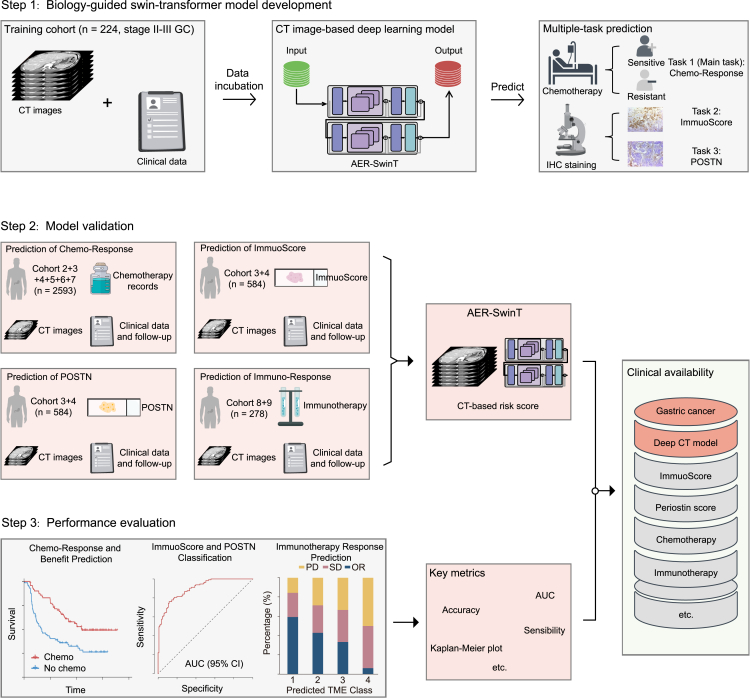

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Developing a multitask deep learning model, residual Swin Transformer network

-

•

The model enables non-invasive evaluation of response to adjuvant chemotherapy

-

•

The model could predict the benefit from immunotherapy in gastric cancer

Sang et al. develop a multitask deep learning model, the residual Swin Transformer network, from radiographic image and clinical data, which allows non-invasive evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy and the tumor microenvironment. The model could further predict the benefit from immunotherapy. This approach paves the way for personalized treatment options.

Introduction

5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy is considered the standard of care for stage II–III gastric cancer (GC) following radical surgery, demonstrating durable anti-tumor responses in some patients.1,2 However, despite the survival benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy, the 5-year overall survival rate for advanced GC remains below 40%, highlighting a significant risk of unnecessary or delayed treatment for a substantial number of patients.3 These conflicting results suggest an urgent clinical need for predictive biomarkers to identify which patients will benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.4 Currently, there is a lack of effective biomarkers for predicting the benefit of 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy, making the identification of predictive biomarkers to personalize treatment for patients with GC crucial and long overdue.

Recently, the emergence of immunotherapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), cancer vaccines, oncolytic viruses, and cell therapies, has revolutionized cancer treatment.5,6,7 Among these, ICIs have become a first-line treatment option for advanced GC.5,8,9 Preliminary positive outcomes have also been observed with perioperative immunotherapy.10,11,12,13 However, the low response rate of ICIs and the difficulty in identifying benefit groups remain major clinical challenges.14 Although biomarkers such as programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), Epstein-Barr virus, microsatellite instability, and tumor mutation burden have been approved to guide ICI therapy, none are fully predictive of immunotherapy responses.14,15,16,17 Therefore, accurately identifying patients who will benefit from immunotherapy to maximize therapeutic outcomes is a critical issue that needs to be addressed.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) consists of innate immune cells, adaptive immune cells, cytokines, and extracellular matrix components.18,19,20 These elements form a complex regulatory network that plays a crucial role in tumor progression and treatment response.19,20,21 Accurate evaluation of the TME can improve the assessment of immunotherapy effectiveness in GC.22 Additionally, the tumor immune status of patients is closely correlated with chemotherapy response, highlighting the value of incorporating TME evaluation into chemotherapy response assessment.23 Our previous studies have shown that ImmunoScore and periostin (POSTN) expression are significantly associated with chemotherapy benefit.21,24 However, the assessment of the TME relying on histopathological staining has limitations, such as invasiveness, sample heterogeneity, high cost, time consuming nature, and technical complexity.25,26,27 Therefore, developing a non-invasive and cost-effective model to assess chemotherapy response while integrating TME status to enhance model performance is imperative.

Radiological imaging is a non-invasive tool routinely used for diagnosis, staging, and treatment evaluation in patients with cancer, including those with GC.28,29 Recently, deep learning has emerged as a transformative methodology for automatically learning representative features from annotated tumor images for disease evaluation. Traditionally, deep learning models have been designed for single-task purposes, such as predicting specific clinical outcomes (e.g., lymph node metastasis).30,31 In contrast, multitask deep learning enables the simultaneous analysis of different tasks within a single model.32 By sharing feature representations and interactions among related tasks, multitask learning is more data efficient and has been shown to reduce overfitting and improve model generalization across various applications, including computer vision, disease diagnosis, and drug discovery.33,34,35

Here, we developed a multitask deep learning model called attention-enhanced residual Swin Transformer (AER-SwinT) for the simultaneous prediction of chemotherapy response and TME characteristics using preoperative computed tomography (CT) images. Compared to existing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or transformer-based methods, our approach captures global feature relationships while leveraging multiple granularities for data analysis. AER-SwinT employs the Swin Transformer to extract hierarchical features from CT images, enabling analysis at various levels of granularity, from fine to coarse.36,37,38,39,40,41 Additionally, channel average-based attention maps and residual connections enhance the AER-SwinT model’s ability to dynamically refine its focus on spatial regions, improving feature extraction across multiple stages.42 Furthermore, this multitask learning approach enables the model to capture more comprehensive features from the training data. By using chemotherapy response as the primary task and ImmunoScore and POSTN expression as intermediate tasks, the model leverages these clinically relevant immune biomarkers to improve predictive accuracy over single-task methods. Given the established clinical importance of these immune biomarkers, we also evaluated the model’s ability to predict immunotherapy outcomes.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table S1 lists the detailed clinicopathological characteristics of the patients and treatment outcomes in the training and validation cohorts. Of these patients, 1,926 (68.4%) were men, and the median age was 57.0 (interquartile range: 49.0–65.0) years. The majority (n = 2,579, 91.6%) had stage II or III disease, among whom 1,403 (54.4%) patients received fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy, which was the cohort used for the prediction task of chemotherapy response (main task). Patients (n = 808, 28.7%) with immunohistochemistry (IHC) slides were used for predicting tasks of TME evaluation (subtasks). The demographic, clinicopathological, and treatment characteristics were mostly similar and well balanced across different cohorts. Table S2 lists the detailed clinicopathological features of the immunotherapy cohorts. Among patients in the ICI cohorts, 161 (57.9%) were men, and the median age was 57.0 (interquartile range: 48.0–65.0) years. The overall study design is shown in Figures 1 and S1.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the study

Pretreatment CT images were retrospectively retrieved to develop and validate the multitask Swin Transformer for non-invasive prediction of chemotherapy response and the tumor microenvironment, which was further used to evaluate the prognosis and response to immunotherapy. Immunotherapy response outcomes are represented as percentage. Cohort 1–3 and 8 from SMU: Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University. Cohort 4–5 from SYSUCC: Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. Cohort 6 from YNCH: Yunnan Cancer Hospital. Cohort 7 from KMU: First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University. Cohort 9 from GPHCM: Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine.

Multitask AER-SwinT for chemotherapy response and IHC expression

We trained an attention-enhanced Swin Transformer network to predict chemotherapy response and IHC expression using preoperative CT image and clinical factors (Figures 2A and 2B). The primary characteristics of AER-SwinT include hierarchical feature extraction and dynamic attention mechanisms (Figure 2A). The source code for our model is available at: https://github.com/ShengtianSang/AER-SwinT. Figure 2B presents four representative cases with CT images and visualizations of the network’s predictions for chemotherapy response and IHC expression. Additional results can be found in Figures S2 and S3.

Figure 2.

Architecture of AER-SwinT and intermediate attention maps

(A) The illustration of the comprehensive architecture of AER-SwinT. The model processes CT images through multiple stages to extract hierarchical features and integrate attention mechanisms.

(B) The intermediate attention maps generated by the AER-SwinT model at various stages. It can be observed that as the model progresses through these stages, it produces more global attention, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the spatial and contextual information within the images.

Model accuracy for predicting chemotherapy response

We tested the performance of AER-SwinT in predicting chemotherapy response in patients with stage II and III disease. The proposed model had a consistently high accuracy for predicting chemotherapy response, with areas under the curve (AUCs) of 0.900 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.862–0.938) and 0.886 (95% CI 0.851–0.920) in the training and internal validation cohorts, respectively (Figure 3). Similar results were also observed in external validation cohort 1 with an AUC of 0.881 (95% CI 0.811–0.950) and external validation cohort 2 with an AUC of 0.871 (95% CI 0.834–0.908) (Figure 3). Another two external cohorts 3–4 also revealed comparatively high accuracy with AUCs of 0.879 (95% CI 0.828–0.930) and 0.876 (95% CI 0.812–0.940) in Figure 3. The distribution of patients between the predicted chemo-response classes in each cohort is shown in Tables S3 and S4. The sensitivity was 74%–91%, specificity was 67%–93%, positive predictive value was 75%–95%, and negative predictive value was 68%–81% in internal and external validation cohorts (Table S5). The overall accuracy for the prediction of chemo-response was over 80%. Consistently, the confusion matrix showed that the model predictions agreed with the actual chemo-response defined by the disease-free survival (DFS) < or ≥2 years classifier (Figure S4).

Figure 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of the deep learning model in the training cohort, internal validation cohort 1, and external validation cohorts 1–4 for predicting chemotherapy response

The ROC curves show the performance for predicting chemotherapy response in stage II–III patients undergone adjuvant chemotherapy. Data are represented as AUC ± 95% CI. ROC, area under the receiver operator characteristic curve.

Model accuracy for predicting ImmunoScore

The proposed model had a consistently high accuracy for predicting ImmunoScore, with AUCs of 0.839 (95% CI 0.789–0.889) and 0.842 (95% CI 0.785–0.899) in stage II and III patients (Figure 4A). Similar results were also observed in the SYSUCC cohorts with AUCs of 0.844 (95% CI 0.765–0.922) and 0.838 (95% CI 0.740–0.936) (Figure 4A). We also explore the potentiality of the model in stage I and IV patients. The AUCs were 0.835 (95% CI 0.776–0.894) and 0.841 (95% CI 0.734–0.948) in stage I and IV patients, respectively (Figure S5). The association between the deep learning ImmunoScore prediction model and clinicopathological variables is reported in Tables S6 and S7. The sensitivity was 79%–95%. The positive predictive value and negative predictive value were 71%–87% (Table S8). The overall accuracy for the prediction of ImmunoScore classes was 74%–83%. Collectively, the confusion matrix showed that the model predictions agreed with the actual ImmunoScore classes (Figure S6).

Figure 4.

Diagnostic accuracy of the deep learning model in the training cohort, internal validation cohort 2, and external validation cohort 1 for predicting the TME classes defined at immunohistochemistry

(A) The ROC curves show the performance for predicting the ImmunoScore in patients with stage II–III disease.

(B) The ROC curves show the performance for predicting the POSTN in patients with stage II–III disease. Data are represented as AUC ± 95% CI. TME, tumor microenvironment; ROC, area under the receiver operator characteristic curve.

Model accuracy for predicting POSTN

For predicting POSTN, the proposed model demonstrated consistently high accuracy with AUCs of 0.825 (95% CI 0.772–0.878) and 0.822 (95% CI 0.762–0.883) in stage II and III patients (Figure 4B). Similar results were also observed in the SYSUCC cohorts with AUCs of 0.817 (95% CI 0.736–0.897) and 0.848 (95% CI 0.759–0.938) (Figure 4B). The AUCs were 0.818 (95% CI 0.760–0.877) and 0.872 (95% CI 0.758–0.987) in stage I and IV patients, respectively (Figure S7). The association between the deep learning POSTN prediction model and clinicopathological variables is reported in Tables S9 and S10. The sensitivity and specificity were 65%–75%, and the positive predictive value or negative predictive value was 68%–83% (Table S11). As shown in the confusion matrix, the overall accuracy for the prediction of POSTN classes was 71%–81% (Figure S8).

Prognostic value of the proposed TME prediction model

We further investigated the prognostic value of the proposed TME prediction model in the training and validation cohorts. The TME prediction model of ImmunoScore (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.501–0.662, p < 0.005) and POSTN (HR: 1.205–2.978, p < 0.05) was significantly associated with survival outcomes in each cohort (Figures S9 and S10). The 5-year DFS and overall survival (OS) for the predicted high ImmunoScore group (40.1% and 45.7%, respectively) were significantly higher than those in the low ImmunoScore group (23.2% and 28.4%, respectively) (p < 0.001). Similar results were observed in the low POSTN group (39.8% and 45.1%, respectively) and the high POSTN group (26.4% and 31.8%, respectively) (p < 0.001). The multivariate analyses confirmed that the TME prediction model remained an independent predictive factor for clinical outcomes after adjusting for other clinicopathological variables. (Tables S12 and S13). Furthermore, as shown in Table S14, the model integrating the imaging signatures and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage consistently improved the accuracy of prognosis prediction, compared with the TNM stage alone across all cohorts (p < 0.0001).

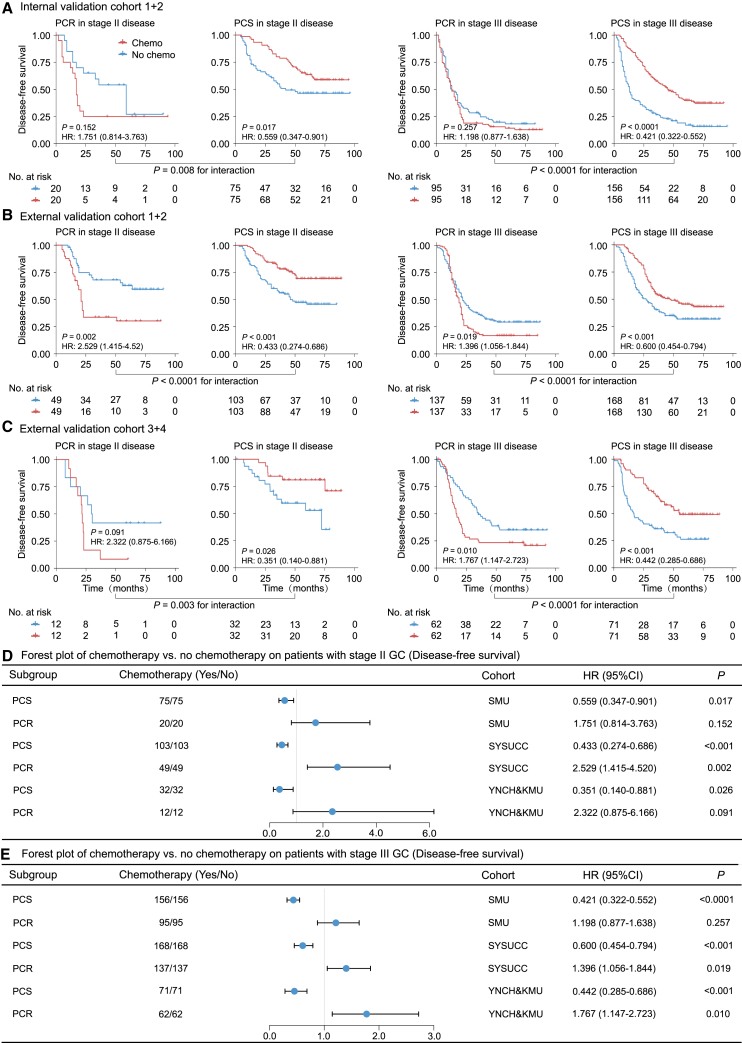

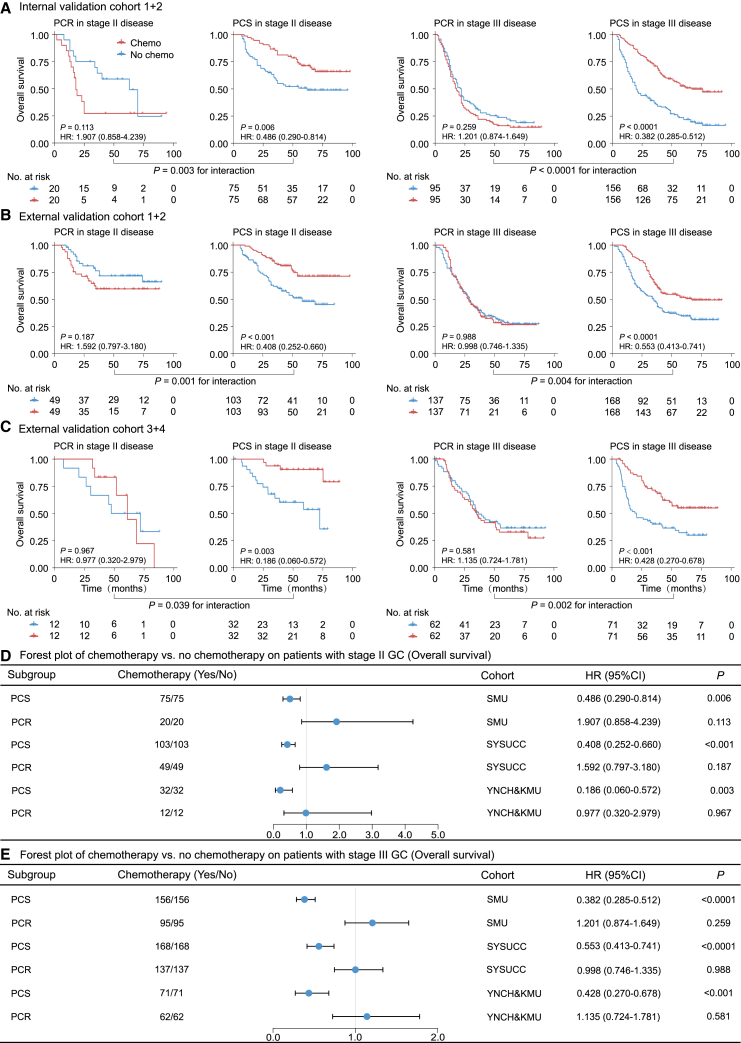

Association with benefit from chemotherapy

We further assessed the predictive value of the deep learning model regarding the survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II and III patients. Initially, we performed propensity score matching (PSM) analysis to balance the characteristics of patients who received chemotherapy and those who did not. Through a 1:1 patient-matching strategy, we achieved comparable clinical characteristics between the two groups. Subsequently, we compared the survival outcomes of patients who either received or did not receive chemotherapy stratified by the predicted chemo-response status, predicted chemo-sensitive (PCS) or predicted chemo-resistant (PCR).

For patients in the PCS group, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with an improved DFS (HR range: 0.351–0.600, p < 0.05) and OS (HR range: 0.186–0.553, p < 0.05) (Figures 5 and 6). However, for patients in the PCR group, adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with any improvement in DFS and OS or even showed adverse effects on survival. Additionally, we performed similar analyses using all stage II–III patients without PSM and obtained consistent results (Figures S11 and S12).

Figure 5.

Predictive value of the proposed deep learning model for survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy on DFS

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves of DFS for patients who are stratified according to receipt of chemotherapy in internal validation cohort after PSM.

(B) Kaplan-Meier curves of DFS for patients who are stratified according to receipt of chemotherapy in external validation cohorts 1–2 after PSM.

(C) Kaplan-Meier curves of DFS for patients who are stratified according to receipt of chemotherapy in external validation cohorts 3–4 after PSM.

(D) Forest plot for the effect of chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy on DFS among stage II patients after PSM.

(E) Forest plot for the effect of chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy on DFS among stage III patients after PSM. Data are represented as hazard ratio ± 95% CI. DFS, disease-free survival; PSM, propensity score matching.

Figure 6.

Predictive value of the proposed deep learning model for survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy on OS

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves of OS for patients who are stratified according to receipt of chemotherapy in internal validation cohort after PSM.

(B) Kaplan-Meier curves of OS for patients who are stratified according to receipt of chemotherapy in external validation cohorts 1–2 after PSM.

(C) Kaplan-Meier curves of OS for patients who are stratified according to receipt of chemotherapy in external validation cohorts 3–4 after PSM.

(D) Forest plot for the effect of chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy on OS among stage II patients after PSM.

(E) Forest plot for the effect of chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy on OS among stage III patients after PSM. Data are represented as hazard ratio ± 95% CI. OS, overall survival; PSM, propensity score matching.

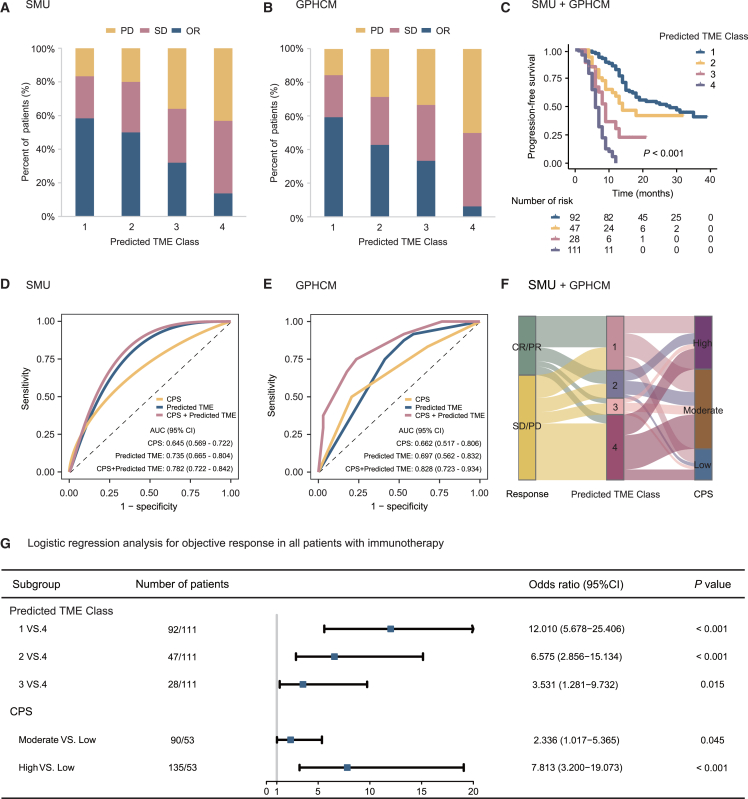

Association with response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy

This study subsequently assessed the relationships between the deep learning TME biomarkers and immunotherapy response in two independent cohorts. The association between the deep learning TME prediction model and clinicopathological variables is reported in Tables S15 and S16. Interestingly, we found that patients in the predicted high ImmunoScore group (55.0% and 56.4%) or low POSTN group (50.6% and 58.3%) had a higher objective response (OR) rate than those in the predicted low ImmunoScore group (17.5% and 10.5%) or high POSTN group (24.5% and 13.6%). The result was also confirmed in the entire immunotherapy cohort (p < 0.0001) (Figures S13 and S14). We then integrated the predicted ImmunoScore and POSTN biomarkers into a TME model. A heterogeneous OR rate was observed among different TME classes: 58.7% of high ImmunoScore and low POSTN (predicted TME class 1), 48.9% of high ImmunoScore and high POSTN (predicted TME class 2), 32.1% of low ImmunoScore and low POSTN (predicted TME class 3), and 12.6% of low ImmunoScore and high POSTN (predicted TME class 4) (p < 0.0001), which was also confirmed in each immunotherapy cohort (Figures 7A and 7B). Furthermore, as shown in Figures 7C and S15, Kaplan-Meier plots of progression-free survival (PFS) confirmed the prognostic value of two predicted biomarkers (ImmunoScore or POSTN) and the predicted TME model (p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Predictive value of the proposed deep learning model for therapeutic response and clinical outcomes in patients treated with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy

(A) The objective response rate of immunotherapy in different predicted TME status in the SMU cohort.

(B) The objective response rate of immunotherapy in different predicted TME status in the GPHCM cohort.

(C) Prognostic value of the predicted TME classes for PFS in patients treated with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy.

(D) Receiver operating characteristic curves of the predicted TME classes for predicting immunotherapy response in the SMU cohort.

(E) Receiver operating characteristic curves of the predicted TME classes for predicting immunotherapy response in the GPHCM cohort.

(F) The association between the predicted TME model and immunotherapy response or CPS.

(G) Forest plot for the effect of predicted TME model and CPS in evaluating immunotherapy response. Immunotherapy response outcomes are represented as percentage. ROC outcomes are represented as AUC ± 95% CI. Logistic regression outcomes are represented as odds ratio ± 95% CI. PD, progressed disease; SD, stable disease; OR, objective response; TME, tumor microenvironment; Predicted TME class 1, predicted high ImmunoScore and low POSTN; Predicted TME class 2, predicted high ImmunoScore and high POSTN; Predicted TME class 3, predicted low ImmunoScore and low POSTN; Predicted TME class 4, predicted low ImmunoScore and high POSTN; CPS, combined positive score; SMU, Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University; GPHCM, Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine.

We next compared the performance of the predicted TME model and PD-L1 for predicting immunotherapy response. We found that the combined positive score (CPS) of PD-L1 expression showed a quite modest ability in predicting immunotherapy response, with AUCs of 0.645 (95% CI, 0.569–0.722) and 0.662 (0.517–0.806) in the immunotherapy cohort 1 and 2. However, the predicted TME model presented higher AUCs of 0.735 (0.665–0.804) and 0.697 (0.562–0.832) compared to CPS (Figures 7D and 7E). Importantly, when CPS and the predicted TME model were combined into an integrative model, a significant improvement in the accuracy of immunotherapy response prediction was observed (AUC: 0.782–0.828, p < 0.05) compared with CPS. The association between the predicted TME model and CPS is shown in Figure 7F. Multivariate analyses confirmed that the TME prediction model remained an independent predictive factor for anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) immunotherapy response (Figure 7G).

Extended experimental validation and ablation studies

To provide a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed AER-SwinT model, we conducted additional comparative experiments involving CNN-based methods (Unet,43 VGG,44 ResNet,45 Inception,46 and DenseNet47) and transformer-based methods (ViT48 and SwinUnet49) using the same datasets. These models were selected as comparison methods due to their widespread adoption and proven effectiveness in medical image analysis tasks.36,37,38,39,40 Figure S16 illustrates that AER-SwinT consistently outperformed the baseline models in the primary task and the two intermediate tasks across internal and external datasets. Notably, transformer-based methods generally performed better than CNN-based models, highlighting the advantage of capturing global relationships within the data for enhanced analytical capabilities. Furthermore, we conducted ablation studies to validate the contributions of the multitask training strategy and specific architectural components of our model. First, we compared a single-task version of AER-SwinT, trained solely for chemotherapy response prediction, against our multitask training approach. Figure S17 shows that the multitask training strategy improved performance compared to the single task, emphasizing that incorporating clinically relevant subtasks facilitates more discriminative feature extraction. Additionally, we assessed the impact of the channel average-based attention maps module (SENet),39 which implements channel attention through residual aggregation. We evaluated alternative aggregation methods such as Gather-excite,50 GCT,51 and AvgNet52 in the model. The results demonstrated that the SENet-based design achieved the highest performance.

Discussion

Immune checkpoint blockade and adjuvant chemotherapy have shown quite durable anti-tumor responses, but the lack of effective biomarkers limits the therapeutic benefits.4,14 These challenges highlight the importance of developing cost-effective and accurate prediction models for chemotherapy and immunotherapy. In this retrospective multi-center study of 3,095 patients, we developed a multitask deep learning model called AER-SwinT for the simultaneous prediction of chemotherapy response after radical surgery and the TME (ImmunoScore and POSTN expression) using preoperative CT images. By employing attention-enhanced hierarchical features and multitask learning, AER-SwinT accurately predicts chemotherapy response and TME characteristics. For patients predicted as chemo-sensitive through the proposed deep learning model, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved survival, whereas those predicted as chemo-resistant did not. Furthermore, given the established clinical relevance of TME biomarkers, the multitask deep learning model showed predictive value for prognosis and could distinguish patients who might or might not benefit from anti-PD-1 immunotherapy.

Systemic chemotherapy is considered as a standard treatment for local advanced GC in Western or Eastern nations.1,2 Adding chemotherapy to surgery has improved patient survival. However, larger variation in clinical outcomes and treatment responses is observed even among patients with same clinicopathologic features and similar treatment regimens.3 Given these heterogeneous outcomes, accurate prediction of chemotherapy response after gastrectomy is crucial for making appropriate treatment decisions about adjuvant therapies.4 To address these challenges, several biomarkers associated with chemotherapy response had been reported. Yong and colleagues developed a gene signature to predict response to 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy on a phase 2 clinical trial with 81 patients with GC.53 Chen and colleagues found that pathomics signature was associated with chemotherapy response of GC in two cohorts with 480 patients.54 However, these studies included a relatively small number of patients, and the methodology used was invasive and costly. By analyzing data for 3,095 patients, this study developed a non-invasive deep learning model based on preoperative CT images to directly predict response to 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in resected GC. Our method can identify patients who can benefit from postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II and III GC. Patients identified as chemo-sensitive are likely to experience significant survival benefits from adjuvant chemotherapy, whereas those identified as chemo-resistant do not. The prediction model will allow the optimization of individual decision-making. By utilizing AER-SwinT, we can predict that sensitive patients would benefit from aggressive treatment regimens to improve survival, while resistant patients could be spared from the adverse effects of adjuvant therapies.

The recent success of immunotherapy across various cancer types highlights the need to better understand the mechanisms of effective anti-tumor immune responses and to identify the immunotherapy benefit for individual patient.6,7,8,10,11,55 The TME is cumulatively recognized as the key regulator of all types of anti-cancer therapy.19,20,21 Compared with chemotherapy non-responders, response was associated with on-treatment TME remodeling including natural killer cell recruitment, decreased tumor-associated macrophages, M1-macrophage repolarization, and increased effector T cell infiltration.23 Thus, assessing the TME at treatment will assist decision-making of adjuvant chemotherapy, and introducing TME information in prediction model development for chemotherapy response is of great value. Additionally, increasing evidence established the role of TME as a determinant for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy responses in various cancer.19,20,21,22 To dissect inter-tumor TME heterogeneity, we defined two biomarkers (ImmunoScore and POSTN) with established biological and clinical relevance.21,24 The proposed deep learning model enables non-invasive, economical, accurate, and dynamic monitoring of the TME. Given the limitations in tissue access, as well as the high cost, time-consuming nature, and technical complexity of histological approaches, our method offers a viable alternative to overcome these challenges.

Although immunotherapy has been recommended as a first-line treatment option for advanced GC, its application in the perioperative setting is still in the early stages of exploration, and relevant data remain limited.5,8,9,10,11,12,13 Therefore, this study only explored the application of the developed model in immunotherapy for advanced GC. Besides, 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy is considered the standard of care for stage II–III GC following radical surgery.1,2 Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced GC and immunotherapy for advanced GC are different treatment options targeting patients at different disease stages. Thus, it is worth noting that the predictive effect of the CT-based model developed in this study for chemotherapy and immunotherapy was explored using two distinct cohorts: the former comprising patients with GC receiving postoperative adjuvant therapy, and the latter comprising patients with advanced-stage GC. In the future, as more data become available, we will further investigate the model’s predictive value in the context of perioperative immunotherapy.

Importantly, considering the established relevance between TME biomarkers and immunotherapy, we observed that the proposed deep learning model had potential to improve the prediction of response to immunotherapy. Although several biomarkers, such as PD-L1, had been proposed for evaluating response to immunotherapy, their sensitivity and specificity were unsatisfactory and warrant further investigation.14,15,16,17 While integrating the TME model, the diagnostic accuracy of immunotherapy response prediction by PD-L1 could be improved. These results indicate that the prediction model allows for the optimization of individualized decision-making for adjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

Using deep learning approach to automatically learn quantitative representation from medical images is the development trend of intelligent precision diagnosis and treatment research.28,56 Most deep learning methods for clinical tasks rely on convolutional networks (CNNs) and transformer architectures.36,37,38,39,40,57,58,59 CNN-based approaches are inherently constrained by their limited receptive field, hampering their ability to capture comprehensive global information from medical images. Transformer-based methods, while powerful, often struggle to extract multi-granular details effectively, which is critical for developing a thorough understanding of the data and achieving accurate analysis. This study addresses these limitations by introducing AER-SwinT, a deep learning model designed to predict chemotherapy response and assess the TME using preoperative CT images. Our approach leverages the hierarchical feature extraction capabilities of the Swin Transformer, enabling the model to process data from fine to coarse granularity. This allows AER-SwinT to capture both global and detailed information crucial for accurate clinical predictions. Additionally, our method adopts channel average-based attention maps at multiple stages. These attention maps dynamically highlight regions of interest within the CT images, allowing the model to focus on critical spatial locations through pointwise multiplication and residual connections. This mechanism ensures that the model emphasizes important features at each stage, significantly improving its ability to capture different details and enhance overall performance. Compared to traditional CNN and transformer models, our AER-SwinT integrates hierarchical feature extraction with dynamic attention mechanisms. Comparative experiments demonstrate that AER-SwinT outperforms both CNN-based methods and other transformer-based architectures, underscoring the importance of capturing global context for effective feature representation. Ablation analyses highlight the value of the multitask learning approach and channel attention residual aggregation. By incorporating clinically relevant immune biomarkers, such as ImmunoScore and POSTN expression, as intermediate tasks, our model enhances predictive accuracy for chemotherapy and immunotherapy outcomes. This innovative approach overcomes the limitations of existing methods, offering a robust framework for comprehensive clinical analysis and marking a significant advancement in medical imaging and predictive analytics. Additionally, channel average-based attention maps effectively leverage global relationships within the data, significantly contributing to performance improvements. These findings suggest that integrating a channel attention mechanism helps isolate and amplify critical features, making it a valuable component in transformer-based medical image analysis.

In addition, Figures 2B and S3 show the attention generated at each stage of our model. In the initial stage, our model primarily focuses on the edge information of the tumor within the CT images. As the model deepens, it progressively extracts coarser granularity information while simultaneously increasing attention on the internal regions of the tumor. These examples demonstrate that our method, through hierarchical feature extraction and guided attention mechanisms, enables the model to focus on different areas of the tumor at various granularities. Consequently, this approach allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the patient’s image data.

During the primary task of chemotherapy response prediction, we adopted training strategies that introduced TME and routine clinical features, which further improved the model’s performance and outperformed a traditional single-task deep learning model or single-scale convolution neural network. Compared with traditional machine-learning-based radiomics models and deep-learning-based single-task imaging models, the proposed multitask AER-SwinT model optimized the training procedure and achieved cost-effective, accurate predictions. Future research should appropriately adopt deep learning techniques that offer cost and time advantages and ensure the development of robust models that meet clinical requirements.

Although some methods were adored to reduce the heterogeneity of CT images, the heterogeneity of these data should not be ignored. In the future, several strategies should be addressed to reduce the impact of CT scanner heterogeneity on model performance. First, we aim to standardize the models and parameters of CT machines across different centers to reduce variability in imaging data. Second, we plan to develop and incorporate advanced normalization algorithms that dynamically adjust for scanner-specific differences during preprocessing, ensuring consistent feature extraction across datasets. Third, we will leverage data augmentation techniques, such as adding noise simulated from different scanning protocols and domain adaptation methods, to enhance the model’s adaptability to data from diverse scanners. These efforts will help minimize scanner-induced variability and improve the model’s reliability in clinical applications.

Limitations of the study

This study has some limitations. The primary limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. The second limitation is that the data were obtained from patients of East Asian origin only, and the pathological subtype and distribution of clinical characteristics might be different in patients from other geographical regions, necessitating validation by other diverse populations and ethnic groups in a large cohort. The third point is that CT images were achieved from various scanners in different institutions, which may increase the heterogeneity of the data. Fourthly, this study only explored the application of the developed model in immunotherapy for advanced GC. Further investigation in the context of perioperative immunotherapy is need. Additionally, gender was included as a demographic variable in the dataset, but no gender-specific analyses were conducted. We recognize this as a limitation of the current study, and further investigations are warranted to determine whether gender may affect the study outcomes. Finally, the patients enrolled in the study were treated over decades and not within a randomized trial setting. Although the treatment was 5-fluorouracil based, the treatment drugs and cycles are not uniform, and the decision to treat patients with chemotherapy or not was made by the clinicians or patients, or both. As such, a rigorously designed randomized controlled trial to validate the generalizability and reproducibility is required.

In conclusion, we developed a multitask deep learning model of CT images that allowed the simultaneous prediction of chemotherapy response and the TME. The imaging model also enabled improved assessment of prognosis and immunotherapy response. These results warrant prospective validation in future randomized trials to test the clinical utility of our imaging model to optimize individual decision-making.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yuming Jiang (yumjiang@wakehealth.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

The CT image data used in this study are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns and ethical restrictions. To request access, please contact the lead contact Yuming Jiang (yumjiang@wakehealth.edu). All requests will be reviewed by the institutional ethics committee and data-sharing board to ensure compliance with data privacy regulations and informed consent agreements. Access will be granted for non-commercial, academic research purposes only. Personally identifiable clinical information will be provided upon reasonable request. Summary-level statistics are deposited in the supplementary tables and are publicly available as of the date of publication.

-

•

This is the DOI for our paper: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15580785, and the source code used in this study has been deposited in Zenodo and is publicly available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15580785.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

Y.J., Z.L., G.L., and S.S.: conceptualization; Y.J., S.S., Z.S., W.Z., T.Z., Z.H., W.X., and J.Y.: data curation; S.S., Z.S., and W.Z.: formal analysis; W.W., Yijun Chen, Q.Y., C.C., and S.X.: investigation; Y.J., S.S., and Z.S.: methodology; L.W., W.L., J.X., W.F., and Yan Chen: software; Y.J. and G.L.: project administration; Y.J. and Z.L.: supervision; S.S., Z.S., W.Z., and M.T.I.: writing – original draft; S.S., Z.S., W.Z., and Y.J.: writing – review and editing.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| CD3 | NeoMarker | clone SP7 |

| CD8 | NeoMarker | clone SP16 |

| CD45RO | Invitrogen | clone UCHL1 |

| CD66b | BD Pharmingen | Cat#555723 |

| POSTN | Abcam | ab92460 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| R 4.1.0 | The R Project for Statistical Computing | https://www.r-project.org |

| GraphPad PRISM 8 | GraphPad software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| SPSS software version 21.0 | IBM SPSS software | https://www.ibm.com/spss |

| Python version 3.9 | Python software | https://www.python.org/ |

Experimental model and study participant details

Patient enrollment and data collection

The overall study design is shown in Figure 1. This study followed the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) reporting guideline. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Yunnan Cancer Hospital, First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, and Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine. Patient consent was waived for this retrospective analysis. We retrospectively reviewed data for 5,668 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma who underwent treatment in five academic medical centers from China. All patients satisfied the following inclusion criteria (except for 156 patients in internal cohort two and 82 patients in external cohort one with stage I or IV disease with IHC): presence of primary stage II or III GC, no combined malignant neoplasm, no preoperative chemotherapy, no distant metastasis, R0 resection (no residual macroscopic or microscopic tumor), more than 15 examined lymph nodes, preoperative contrast-enhanced abdominal CT available, complete clinicopathological and follow-up data available. We excluded patients who had other synchronous malignant neoplasms, or previously received neoadjuvant chemotherapy; cases were also excluded if the primary tumor could not be identified on CT. For patients received immunotherapy, we included those with histologically confirmed gastric adenocarcinoma, standard unenhanced and contrast-enhanced abdominal CT imaging performed before immunotherapy, and complete information about clinicopathological characteristics and follow-up data available. We excluded those patients who had other synchronous malignant neoplasms, or if the tumor lesions could not be identified on CT images. Our study included cohorts from different regions and centers, spanning across the eastern and western regions of China, with a time frame ranging from 2005 to 2022. The internal and external validation cohorts from various centers and time periods effectively demonstrate the generalizability and robustness of the model, reducing biases caused by regional discrepancies.

A total of 3,095 patients in nine independent cohorts were enrolled in this study (Figure S1). We collected data of 1,262 patients in the training and two internal validation cohort who underwent surgery at Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University (SMU) between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2015. We included another 1039 patients who met the inclusion criteria and underwent surgery in two independent validation cohorts at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC) between June 1, 2008 and June 30, 2013. We further enrolled 516 patients who met the inclusion criteria and underwent surgery in another two cancer centers of Yunnan Cancer Hospital (YNCH) and First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (KMU) between January 1, 2011 and December 30, 2017. Of note, the training cohort contained patients with complete data available that are necessary for model development. The patients in the training cohort, internal cohort 2, and external cohort 1 were with the IHC staining image, and patients in the internal cohort 1 and external validation cohort 2–4 were without the IHC staining image. All patients (>90%) were diagnosed with primary stage II or III GC, except for 156 from internal cohort two and 82 from external cohort one with stage I or IV disease.

Additionally, we enrolled 278 advanced GC patients treated with anti-PD1 immunotherapy at two institutions of Nanfang Hospital (220 patients) and Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (GPHCM, 58 patients) between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2022. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the five participating centers, and informed consent was waived for this retrospective analysis.

Clinicopathologic data including age, gender, tumor and lymph node status, tumor differentiation, Lauren type, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) were collected. Anti-PD-1 drugs included: Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab, and Toripalimab. D2 lymph node dissection was performed in most patients (>90%) in accordance with the Japanese guidelines.60 All patients were restaged according to the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria.61 In the training cohort, internal validation cohorts 1 from Nanfang Hospital, there were 224 and 346 patients who received 5-fluorouracil–based chemotherapy, respectively. In the external validation cohort 1 and 2 from SYSUCC, 103 and 391 patients received 5-fluorouracil–based chemotherapy. In the external validation cohort 3 and 4 from YNCH and KMU, 216 and 123 patients received 5-fluorouracil–based chemotherapy, respectively. DFS was defined as the time from surgery to disease progression or death due to any cause. OS was defined as the time from surgery to death due to any cause or the last date of follow-up.

Method details

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining

FFPE samples were cut into 4-μm sections, which were then processed for immunohistochemistry as previously described.21 After incubation with an antibody against human CD3 (NeoMarker, clone SP7), CD8 (NeoMarker, clone SP16), CD20 (Invitrogen, clone L26), CD45RO (Invitrogen, clone UCHL1), CD45RA (Zhong-shan Goldenbridge), CD57 (NeoMarker, clone NK1), CD66b (BD Pharmingen), CD68 (Dako, clone PG-M1), FoxP3 (R&D AF3240), and periostin (POSTN) (NeoMarker, clone SP16), the adjacent sections were stained with diaminobenzidine or 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole in an Envision System (Dako Cytomation). The antibody dilutions and antigen retrieval are shown in Table S17. Every staining run contained a slide treated with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) buffer in place of the primary antibody as a negative control. Every staining run contained a slide of positive control. Prior to staining, sections were blocked with endogenous peroxidase (prepared in 1% H2O2/methanol solution) for 10 min and then microwaved for 30 min in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. The sections were blocked using 10% normal rabbit serum for 30 min. Furthermore, all slides were stained with the same concentrations of primary antibody for each antibody and incubated with monoclonal primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with an amplification system with a labeled polymer/HRP (EnVision, DakoCytomation, Denmark) at 37°C for 30 min. The sections were developed with 0.05% 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) and counterstained with modified Harris hematoxylin. And all slides were stained with DAB dyeing for the same time for each antibody.

At low power (100x), the tissue sections were screened using an inverted research microscope (model DM IRB; Leica, Germany). Two areas of interest, i.e., center of tumor (CT) and invasive margin (IM), were evaluated at 200× magnification to measure the density of stained immune cells for ISGC calculation. The nucleated stained cells in each area were quantified and expressed as the number of cells per field. For a representative analysis of POSTN, five high-power fields sampled randomly over the entire tumor area in the total specimen were selected for evaluation at 200× magnification. Stain intensity was graded as 0 (negative staining), 1 (weak staining), 2 (moderate staining), and 3 (strong staining); stain extent was graded as 0 (0%–4%), 1 (5%–24%), 2 (25%–49%), 3 (50%–74%), and 4 (>75%).62 Values of the stain intensity and extent were multiplied and then averaged over the five fields as the final score for each marker. IHC evaluation was independently performed by two gastroenterology pathologists (T.L. and S.X. with 5–10 years of experience) who were blinded to the outcome data. In cases where differences arose between the two primary pathologists, a third pathologist was consulted to reach a consensus.

Definition of immunoscore and periostin expression

We defined immunoscore using the previously validated immune biomarkers in GC, i.e., the ImmunoScore of Gastric Cancer (ISGC). As previously described, the ISGC score consists of several important immune cell types and is calculated as: ISGC = (0.149∗CD3invasive margin) + (0.021∗CD3center of tumor) + (0.044∗CD8invasive margin) + (0.096∗CD45ROcenter of tumor) – (0.173∗CD66binvasive margin).21 POSTN is an extracellular matrix protein secreted predominantly by stromal cells, which regulates cancer cell migration, invasion, metastatic dissemination, and chemoresistance.62,63,64 These biomarkers represent two major axes of the TME. Specifically, both the ISGC and POSTN were dichotomized into low vs. high expression according to their medium values in the training cohort.

Immunohistochemistry assessment of TME biomarkers

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples were processed for IHC staining as previously described.21 Following incubation with antibodies against human human CD3, CD8, CD45RO, CD66b, and POSTN, the tumor sections were stained in an EnVision System (Dako) (Table S16). At low power (100x), the tissue sections were screened using an inverted research microscope (model DM IRB; Leica, Germany). Two areas of interest, i.e., center of tumor (CT) and invasive margin (IM), were evaluated at 200× magnification to measure the density of stained immune cells for ISGC calculation. The nucleated stained cells in each area were quantified and expressed as the number of cells per field. For a representative analysis of POSTN, five high-power fields sampled randomly over the entire tumor area in the total specimen were selected for evaluation at 200× magnification. Stain intensity was graded as 0 (negative staining), 1 (weak staining), 2 (moderate staining), and 3 (strong staining); stain extent was graded as 0 (0%–4%), 1 (5%–24%), 2 (25%–49%), 3 (50%–74%), and 4 (>75%).62 Values of the stain intensity and extent were multiplied and then averaged over the five fields as the final score for each marker. IHC evaluation was independently performed by two gastroenterology pathologists who were blinded to the outcome data. In cases where differences arose between the two primary pathologists, a third pathologist was consulted to reach a consensus.

CT acquisition and image processing

All patients underwent contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scans prior to surgery or immunotherapy. All patients underwent contrast-enhanced abdominal CT using the multidetector row CT (MDCT) systems (GE Lightspeed 16, GE Healthcare Milwaukee, WI; 64-section LightSpeed VCT, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI; USA). Following intravenous contrast administration, arterial and portal venous-phase contrast-enhanced CT scans were performed after delays of 28 s and 60 s, respectively. Iodinated contrast material in the amount of 90–100 mL (Ultravist 370, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) was injected at a rate of 3.0 or 3.5 mL/s with a pump injector (Ulrich CT Plus 150, Ulrich Medical, Ulm, Germany). The CT acquisition protocols were as follows: 120 kV; 150–190 mAs; 0.5- or 0.4-s rotation time. Contrast-enhanced CT was reconstructed with a field of view, 350 × 350 mm; data matrix, 512 × 512; in-plane spatial resolution 0.607–0.751 mm; axial slice thickness 5.0 mm for 98% patients with a range of 1.25–7.5 mm. Portal venous-phase CT images were retrieved from the picture archiving and communication system (Carestream, Canada).

The procedures for image preprocessing were similar to a previous work.24 Briefly, the CT scans were retrieved from the picture archiving and communication system (Carestream, Canada). The portal venous-phase images were analyzed given a better contrast between the tumor and adjacent normal tissue. The CT number (i.e., Hounsfield units) was normalized with the soft tissue window of [-150, 150] HU. The primary tumor was delineated on the CT images by two radiologists (C.C. and Q.Y. with 11 and 10 years of clinical experience in abdominal CT interpretation, respectively) using the ITK-SNAP software. Both radiologists were present and reached consensus regarding tumor delineation. To focus analysis on the most relevant region, the image outside the primary tumor was cropped by applying the binary tumor mask. Finally, an image patch with a size of that centered around the tumor was fed into the network for subsequent analysis.

Clinical data preprocessing

We preprocessed the clinical data by normalization and imputation. The features with missing values in the dataset are imputed as −1.

Development of the AER-SwinT model

We proposed a deep learning network named AER-SwinT, which integrates multi-level features from CT images with enhanced attention mechanisms, designed to predict chemotherapy response as its primary task. The model was trained based on a DFS< or ≥2 years classifier. The classes were labeled ‘Chemo-Sensitive’ (Chemo-sensitive, i.e., those patients that derive a survival benefit from Chemotherapy, DFS≥2 years) and ‘Chemo-Resistant’ (Chemo-resistant, i.e., those patients that lack a survival benefit from Chemotherapy, DFS< 2 years). Two subtasks, Immunoscore and POSTN expression, were used as intermediate tasks to improve the model’s performance.

We utilized attention-enhanced SwinTransformer architecture to extract features at different granularities of CT images.41 An overview of the model architecture is presented in Figure 2A. The architecture mainly contains four stages that generate various resolution features and attention maps of the CT image. Each step’s theoretical dimensions of feature maps are displayed above the framework, while the practical dimensions are given below. Given a CT image as input, the model first splits it into non-overlapping patches by patch partition layer (Figure S2A). Each image patch is stretched as a vector, and its value is the concatenation of the raw input values of the CT image. We employ a patch size of following the typical settings in our implementation. As a result, the original CT image is split into patches, and the patch partition layer generates a feature map. Then we use a linear embedding layer to project the stretched image patch to an arbitrary dimension (denoted as ), where the output of linear embedding layer is . Following that, multiple SwinTransformer blocks (Figure S2B) are applied to these patches. Subsequently, a channel average operation is performed on the features extracted by the Swin-Transformer to compute the average attention map for each channel. This attention map represents the model’s attention levels across different spatial locations of the feature map. Finally, the attention map is combined with the features extracted by the Swin-Transformer through pointwise multiplication and residual connections to produce the output of “Stage 1”. The patch merging layer produces a hierarchical representation of features, which obtains more high-level features by down-sampling 2 of the feature resolution and increasing 2 of the channels (Figure S2C). Then Swin-Transformer and channel average blocks are applied to the converted feature maps (Stage 2), which generates a feature map. The procedure is repeated twice, as “Stage 3” and “Stage 4”, with output resolutions of and , respectively. Next, we use an average pooling layer to transform the feature maps, which produce a vector as the CT image features of each patient. Meanwhile, we concatenate the clinical features of patients to the image features as the final features of each patient for two subtasks. Finally, we concatenate the output of the two subtasks with the image and clinical features as the final input to the linear layer associated with the main task. In our experiment, the initial input of the CT image is , and the output resolution of “Stage 4” is . Since we use eight clinical features (as shown in preprocessing), the final feature dimension input to the main task-related discriminant model is 778 (768 + 8+2). As shown in Figure 2A, patch partition, patch merging, and shifted window-based Transformer are the main three parts of our method.

Our model explores global information and extracts multi-level features of the CT image. Figure 2B shows the model’s attention to feature maps at different stages of the model. Figure S3 shows more results of the attention maps on CT images. We introduce the details of each module in the following.

Figure S2B illustrates the processing of patch partition layer. It splits the input image into evenly non-overlapping patches. Each patch is transformed into a vector. These equal-length vectors are used as input to the Transformer to learn the relationship between individual patches and extract the global information of the whole input image.

Figure 2B shows the details of Swin Transformer block. The architecture consists of two consecutive standard multi-head self-attention (MSA) modules.65 First, a regular window partitioning strategy is adopted for an input feature map to split the feature map evenly. Each window contains patches, which is in our example. Partition feature map by windows is for calculating the self-attention between patches within each window. A LayerNorm (LN) layer is applied before both the MSA module and the MLP layers, ensuring normalized feature representations at each stage of processing. The output feature map from the first MSA module undergoes shifted window partitioning before being processed by the next MSA module. This step enables the self-attention computation to extend across window boundaries, facilitating better feature interaction between neighboring patches. The self-attention computation in the new windows crosses the boundaries of the previous windows, allowing patches to communicate with one another. The following steps can derive the final output of the whole Swin Transformer block:

The Transformer modules maintain the number of patches and the resolution of features, then the and the same resolution of the .

Figure 2C illustrates the patch merging layer. For an input feature maps . The patch merging layer first concatenates neighboring patches, converting the feature maps to dimensions. Then a linear layer is applied to compress the feature map to . The number of patches is reduced by patch merging layers as the network gets deeper. The operation decreases the resolution of feature maps, allowing the model to extract higher-level features and produce a hierarchical representation.

Hierarchical attention on feature maps

Our model explores global information and extracts multi-level features of the CT image. Figure 2B shows the model’s attention to feature maps at different stages of the model. We adopt the squeeze-and-excitation method to extract the salient feature map () from a feature map () generated in an intermediate stage.66 The squeeze-and-excitation module emphasizes important spatial regions within feature maps based on channel-wise information. Specifically, the method computes the average activation values across spatial dimensions for each feature channel. These average values are then used to generate weights for each channel, effectively highlighting the most informative channels while suppressing less relevant ones. Each point in the extracted salient feature map indicates the model’s attention to feature maps. Figures 2B and S3 shows several attention results. From the figures, we can see that our model focuses on the edge information of the tumor at first. As the feature granularity increases, our model gradually focuses on the central region of the tumor. From this attention diagram, it can be seen that our model focuses on the information of different regions of the tumor at different stages and finally extracts the multi-scale global features.

Network training

The overall training objective consists of three loss terms: (1) one binary cross entropy loss for the main task, which aims to minimize the difference between the prediction and the ground truth label; (2) other two binary cross entropy losses for the two sub-tasks.

The , and denote the loss for main task, sub task 1 and sub task 2, respectively, and is the overall training objective.

In our experiments, the proposed model was implemented using PyTorch, with the Swin Transformer implementation adopted from the original paper. We use mini-batch stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with momentum 0.9, weight decay of 5 × 10−4 and adaptive learning rates. The batch size is set to 16 and the initial learning rate was set to 0.001, and it was decayed by a factor of 10 at epochs 200, 300, and 400. We perform all experiments under CUDA 11.1 and on a computer equipped with Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8180 (28 cores, 3.4 GHz) CPU, 4 NVIDIA GTX 8000 GPUs, and 256G RAM.

Evaluation of the model’s accuracy for chemotherapy response and TME expression

We evaluated the accuracy of the CT imaging-based model to predict chemotherapy response, the IHC-defined ImmunoScore and POSTN expression. Beside the training cohort, the main predicting task (chemotherapy response) was tested in five independent cohorts (internal validation cohort 2 and external validation cohort 1–4) for stage II-III GC patients with chemotherapy, and the predicting subtasks (ImmunoScore and POSTN expression) was tested in two independent cohorts (internal validation cohort 2 and external validation cohort 1) for which IHC data was available. In all cohorts, cases with a probability greater than 50% predicted by the AER-SwinT model were considered chemotherapy-sensitive, while others were chemotherapy-resistant. Thus, the cutoff value for the training and validation cohorts was 0.5 (probability value 0–1). Consistent cutoff values were used in predicting the IHC-defined ImmunoScore and POSTN expression. Metrics including the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), per-class and overall accuracy were computed. Additionally, we also evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values. The confusion matrix was used to quantify the pairwise classification accuracy among different TME classes. We further investigated the prognostic value of predicted TME classes using survival analyses. And Harrell’s concordance index (C-index) was used to evaluate the improved performance of prognosis prediction provided by the predicted TME classes.

Evaluation of the model’s association with benefit from chemotherapy

We investigated the deep learning model for its ability to predict the survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage II and III GC in a post-hoc exploratory analysis. To minimize selection bias and confounding effects, we used a matching strategy to balance patients between predicted chemo-sensitive and chemo-resistant group. Specifically, PSM was performed for patients who received vs. did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy using 1:1 nearest matching. Propensity scores were calculated using the following clinicopathologic variables: age, gender, differentiation, CEA, CA19-9, location, depth of invasion (T stage), lymph node metastasis (N stage), tumor size, and Lauren type.

Evaluation of the model’s association with response to anti-PD1 immunotherapy

We analyzed an independent cohort of 278 advanced GC patients treated with anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade, and assessed clinical response and outcomes in relation to the deep learning model predicted TME classes. Response to immunotherapy was evaluated according to the irRECIST criteria and defined as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressed disease (PD). Objective response (OR) was defined for patients who achieved either CR or PR. PFS was calculated from the start of treatment until disease progression, death, or last follow up.

The CPS was defined as the total number of PD-L1 positive cells (tumor, lymphocytes, and macrophages) divided by the total number of viable tumor cells multiplied by 100. The pathologist identified regions of interest with good PD-L1 staining under the microscope 5X field, excluding areas with scratches, blood contamination, or necrosis. Subsequently, five non-overlapping regions were randomly selected under a 20X field. In each selected region, the number of PD-L1-stained cells (tumor cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages) and the total tumor cells were counted. Based on the CPS calculation formula, CPS = (PD-L1-stained cells/total tumor cells) × 100, the CPS score for each non-overlapping region was calculated, and the final CPS score was obtained after the average count. Finally, CPS was categorized as high (CPS≥10), intermediate (10>CPS≥1), and low (CPS<1). An integrated model that combined CPS and predicted TME was built using the Classification and Regression Tree algorithm.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis

We compared two groups using the t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Comparisons in AUC were performed using the DeLong’s method. Survival curves were generated according to the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses for survival were performed with the Cox proportional hazard model. Interaction between the predicting model and chemotherapy was also assessed by the Cox model. p value less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant in two-tailed analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.0 and SPSS version 21.0.

Published: July 21, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102242.

Contributor Information

Guoxin Li, Email: gzliguoxin@163.com.

Zhenhui Li, Email: lizhenhui@kmmu.edu.cn.

Yuming Jiang, Email: yumjiang@wakehealth.edu.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Joshi S.S., Badgwell B.D. Current treatment and recent progress in gastric cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:264–279. doi: 10.3322/caac.21657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X., Liang H., Li Z., Xue Y., Wang Y., Zhou Z., Yu J., Bu Z., Chen L., Du Y., et al. Perioperative or postoperative adjuvant oxaliplatin with S-1 versus adjuvant oxaliplatin with capecitabine in patients with locally advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma undergoing D2 gastrectomy (RESOLVE): an open-label, superiority and non-inferiority, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1081–1092. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noh S.H., Park S.R., Yang H.K., Chung H.C., Chung I.J., Kim S.W., Kim H.H., Choi J.H., Kim H.K., Yu W., et al. Adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): 5-year follow-up of an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundar R., Tan P. Genomic Analyses and Precision Oncology in Gastroesophageal Cancer: Forwards or Backwards? Cancer Discov. 2018;8:14–16. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janjigian Y.Y., Ajani J.A., Moehler M., Shen L., Garrido M., Gallardo C., Wyrwicz L., Yamaguchi K., Cleary J.M., Elimova E., et al. First-Line Nivolumab Plus Chemotherapy for Advanced Gastric, Gastroesophageal Junction, and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: 3-Year Follow-Up of the Phase III CheckMate 649 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024;42:2012–2020. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.01601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felip E., Altorki N., Zhou C., Csőszi T., Vynnychenko I., Goloborodko O., Luft A., Akopov A., Martinez-Marti A., Kenmotsu H., et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:1344–1357. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zappasodi R., Merghoub T., Wolchok J.D. Emerging Concepts for Immune Checkpoint Blockade-Based Combination Therapies. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:581–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajani J.A., D'Amico T.A., Bentrem D.J., Chao J., Cooke D., Corvera C., Das P., Enzinger P.C., Enzler T., Fanta P., et al. Gastric Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2022;20:167–192. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J., Jiang H., Pan Y., Gu K., Cang S., Han L., Shu Y., Li J., Zhao J., Pan H., et al. Sintilimab Plus Chemotherapy for Unresectable Gastric or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer: The ORIENT-16 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;330:2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.19918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan S.Q., Nie R.C., Jin Y., Liang C.C., Li Y.F., Jian R., Sun X.W., Chen Y.B., Guan W.L., Wang Z.X., et al. Perioperative toripalimab and chemotherapy in locally advanced gastric or gastro-esophageal junction cancer: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat. Med. 2024;30:552–559. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02721-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin J.X., Tang Y.H., Zheng H.L., Ye K., Cai J.C., Cai L.S., Lin W., Xie J.W., Wang J.B., Lu J., et al. Neoadjuvant camrelizumab and apatinib combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for locally advanced gastric cancer: a multicenter randomized phase 2 trial. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:41. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44309-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verschoor Y.L., van de Haar J., van den Berg J.G., van Sandick J.W., Kodach L.L., van Dieren J.M., Balduzzi S., Grootscholten C., IJsselsteijn M.E., Veenhof A.A.F.A., et al. Neoadjuvant atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in gastric and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: the phase 2 PANDA trial. Nat. Med. 2024;30:519–530. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02758-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang Y.K., Terashima M., Kim Y.W., Boku N., Chung H.C., Chen J.S., Ji J., Yeh T.S., Chen L.T., Ryu M.H., et al. Adjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for stage III gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer after gastrectomy with D2 or more extensive lymph-node dissection (ATTRACTION-5): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024;9:705–717. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(24)00156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs C.S., Doi T., Jang R.W., Muro K., Satoh T., Machado M., Sun W., Jalal S.I., Shah M.A., Metges J.P., et al. Safety and Efficacy of Pembrolizumab Monotherapy in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Gastric and Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer: Phase 2 Clinical KEYNOTE-059 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y.T., Guan W.L., Zhao Q., Wang D.S., Lu S.X., He C.Y., Chen S.Z., Wang F.H., Li Y.H., Zhou Z.W., et al. PD-1 antibody camrelizumab for Epstein-Barr virus-positive metastatic gastric cancer: a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021;11:5006–5015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pietrantonio F., Randon G., Bartolomeo M.D., Luciani A., Petrelli F. Predictive role of microsatellite instability for of PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. ESMO Open. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2020.100036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marabelle A., Fakih M., Lopez J., Shah M., Shapira-Frommer R., Nakagawa K., Chung H.C., Kindler H.L., Lopez-Martin J.A., Miller W.H., Jr., et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becht E., de Reyniès A., Giraldo N.A., Pilati C., Buttard B., Lacroix L., Selves J., Sautès-Fridman C., Laurent-Puig P., Fridman W.H. Immune and Stromal Classification of Colorectal Cancer Is Associated with Molecular Subtypes and Relevant for Precision Immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:4057–4066. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fridman W.H., Zitvogel L., Sautès-Fridman C., Kroemer G. The immune contexture in cancer prognosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14:717–734. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binnewies M., Roberts E.W., Kersten K., Chan V., Fearon D.F., Merad M., Coussens L.M., Gabrilovich D.I., Ostrand-Rosenberg S., Hedrick C.C., et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 2018;24:541–550. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang Y., Zhang Q., Hu Y., Li T., Yu J., Zhao L., Ye G., Deng H., Mou T., Cai S., et al. ImmunoScore Signature: A Prognostic and Predictive Tool in Gastric Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2018;267:504–513. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Q., Tian C., Wu H., Min L., Chen H., Chen L., Liu F., Sun Y. Tertiary lymphoid structure patterns predicted anti-PD1 therapeutic responses in gastric cancer. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2022;34:365–382. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2022.04.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim R., An M., Lee H., Mehta A., Heo Y.J., Kim K.M., Lee S.Y., Moon J., Kim S.T., Min B.H., et al. Early Tumor-Immune Microenvironmental Remodeling and Response to First-Line Fluoropyrimidine and Platinum Chemotherapy in Advanced Gastric Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:984–1001. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Y., Liang X., Han Z., Wang W., Xi S., Li T., Chen C., Yuan Q., Li N., Yu J., et al. Radiographical assessment of tumour stroma and treatment outcomes using deep learning: a retrospective, multicohort study. Lancet Digit. Health. 2021;3:E371–E382. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derks S., de Klerk L.K., Xu X., Fleitas T., Liu K.X., Liu Y., Dietlein F., Margolis C., Chiaravalli A.M., Da Silva A.C., et al. Characterizing diversity in the tumor-immune microenvironment of distinct subclasses of gastroesophageal adenocarcinomas. Ann. Oncol. 2020;31:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang C., Wang X.Y., Zuo J.L., Wang X.F., Feng X.W., Zhang B., Li Y.T., Yi C.H., Zhang P., Ma X.C., et al. Localization and density of tertiary lymphoid structures associate with molecular subtype and clinical outcome in colorectal cancer liver metastases. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2023;11 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-006425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng D., Li M., Zhou R., Zhang J., Sun H., Shi M., Bin J., Liao Y., Rao J., Liao W. Tumor Microenvironment Characterization in Gastric Cancer Identifies Prognostic and Immunotherapeutically Relevant Gene Signatures. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019;7:737–750. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kann B.H., Hosny A., Aerts H.J.W.L. Artificial intelligence for clinical oncology. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:916–927. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillies R.J., Kinahan P.E., Hricak H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology. 2016;278:563–577. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong D., Fang M.J., Tang L., Shan X.H., Gao J.B., Giganti F., Wang R.P., Chen X., Wang X.X., Palumbo D., et al. Deep learning radiomic nomogram can predict the number of lymph node metastasis in locally advanced gastric cancer: an international multicenter study. Ann. Oncol. 2020;31:912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Y., Liang X., Wang W., Chen C., Yuan Q., Zhang X., Li N., Chen H., Yu J., Xie Y., et al. Noninvasive Prediction of Occult Peritoneal Metastasis in Gastric Cancer Using Deep Learning. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Y., Zhang Z., Yuan Q., Wang W., Wang H., Li T., Huang W., Xie J., Chen C., Sun Z., et al. Predicting peritoneal recurrence and disease-free survival from CT images in gastric cancer with multitask deep learning: a retrospective study. Lancet Digit. Health. 2022;4:e340–e350. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson C.M., Choi J., Lim M. Mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance: lessons from glioblastoma. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:1100–1109. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0433-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H., Liu H., Shen Z., Lin C., Wang X., Qin J., Qin X., Xu J., Sun Y. Tumor-infiltrating Neutrophils is Prognostic and Predictive for Postoperative Adjuvant Chemotherapy Benefit in Patients With Gastric Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2018;267:311–318. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000002058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu M.Y., Chen T.Y., Williamson D.F.K., Zhao M., Shady M., Lipkova J., Mahmood F. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary. Nature. 2021;594:106–110. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan A., Rauf Z., Khan A.R., Rathore S., Khan S.H., Shah N.S., Farooq U., Asif H., Asif A., Zahoora U., Khalil R.U. A recent survey of vision transformers for medical image segmentation. arXiv. 2023 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2312.00634. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai L., Gao J., Zhao D. A review of the application of deep learning in medical image classification and segmentation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020;8:713. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.02.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J., Cui Y., Wei K., Li Z., Li D., Song R., Ren J., Gao X., Yang X. Deep learning predicts resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer: a multicenter study. Gastric Cancer. 2022;25:1050–1059. doi: 10.1007/s10120-022-01328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song Z., Zou S., Zhou W., Huang Y., Shao L., Yuan J., Gou X., Jin W., Wang Z., Chen X., et al. Clinically applicable histopathological diagnosis system for gastric cancer detection using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4294. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18147-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]