Key Teaching Points.

-

•

The infundibular septum, which is anteriorly and superiorly displaced in tetralogy of Fallot, is the most common site implicated in ventricular tachycardia.

-

•

Marked infundibular hypertrophy or the presence of graft material can hinder right-sided ablation.

-

•

If right-sided ventricular tachycardia ablation is incomplete or unsuccessful, alternative strategies include mapping and ablation within the coronary cusps, endocardial left ventricular outflow tract, or great cardiac vein as it courses over the left ventricular summit.

-

•

Ablation within the great cardiac vein requires caution, particularly in ensuring a safe distance from coronary arteries.

Introduction

Ventricular arrhythmias are a common complication years after corrective surgery for tetralogy of Fallot (TOF).1 Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) is most often due to macroreentrant circuits that involve well-defined anatomic isthmuses within the right ventricle (RV), bordered by nonexcitable tissue, such as surgical scars or patches and tricuspid and pulmonary annuli.2 Focal VT has also been described and frequently originates within the same anatomic isthmuses that are implicated in macroreentrant VT, reflecting the arrhythmogenic characteristics of diseased tissue marked by fibrosis and heterogeneous conduction.3 The infundibular septum is the most common site involved in VT in patients with TOF, with right-sided ablation often effective in transecting the implicated isthmus or in abolishing the focal source. However, successful ablation occasionally requires a left-sided approach, with a few cases described of ablation within coronary cusps when a right-sided approach proved ineffective.4 Herein, we report a patient with TOF in whom focal VT was effectively ablated in the left ventricular (LV) summit via the great cardiac vein (GCV).

Case report

A 48-year-old man underwent primary repair for TOF at 5 years of age involving a sub-annular patch repair via ventriculotomy. He was lost to follow-up in early adulthood and presented in an intra-atrial reentrant tachycardia associated with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy (LV ejection fraction 25%) at the age of 40 years. A right atrial lateral wall circuit was successfully ablated, accompanied by prophylactic ablation of the cavotricuspid isthmus. Years later, he presented with palpitations associated with dizziness, along with dyspnea on exertion. He was diagnosed with symptomatic ventricular ectopy (Figure 1A). A 24-hour Holter monitor showed a ventricular ectopy burden of 50% with 138 episodes of nonsustained VT and up to 36 seconds of sustained self-terminating VT at 179 beats/min (Figure 1B). His LV ejection fraction was 50%, with septal hypokinesia and no diastolic dysfunction. He had a sinus rhythm QRS duration of 152 ms, mild RV dilation, preserved RV function, peak pulmonary gradient of 25 mm Hg, trace pulmonary regurgitation, and a multilobulated calcified RV outflow tract. The ventricular ectopy was unresponsive to a beta-blocker and calcium channel antagonist, and sotalol was poorly tolerated.

Figure 1.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and Holter monitoring. A: A 12-lead ECG that captured ventricular ectopic beats. The premature ventricular contractions have an rS pattern in V1, an early precordial transition (V3), and an inferior axis compatible with an outflow tract origin. The biphasic pattern in lead I suggests an origin close to the midline. B: Holter monitor recorded ventricular bigeminy followed by sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia.

An electrophysiological procedure was performed under conscious sedation using a robotic magnetic-guided navigation system (Niobe platform, Stereotaxis, St. Louis, MO) in conjunction with 3-dimensional electroanatomic mapping (CARTO 3, Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA), and integration of computed tomography imaging. No sustained reentrant VT was inducible using a previously described programmed ventricular stimulation protocol.5 The isthmus between the ventricular septal defect patch and pulmonary annulus had a conduction velocity of 0.62 m/s. Mapping of ventricular ectopy within the RV identified the site of earliest activation in the posteroseptal region of the outflow tract. At this location, ventricular activation preceded the QRS complex by 30 ms, the unipolar electrogram recorded a QS pattern, and pace mapping using the PASO Module (Biosense Webster) revealed a 95% match. Catheter ablation with a Navistar RMT Thermocool Catheter (Biosense Webster; 35–50 Watts; 17 mL/min) resulted in an accelerated ventricular response, but failed to eliminate the premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) and runs of nonsustained VT. The aortic cusps and endocardial LV outflow tract were subsequently mapped by a retrograde aortic approach. No site with earlier ventricular activation was identified.

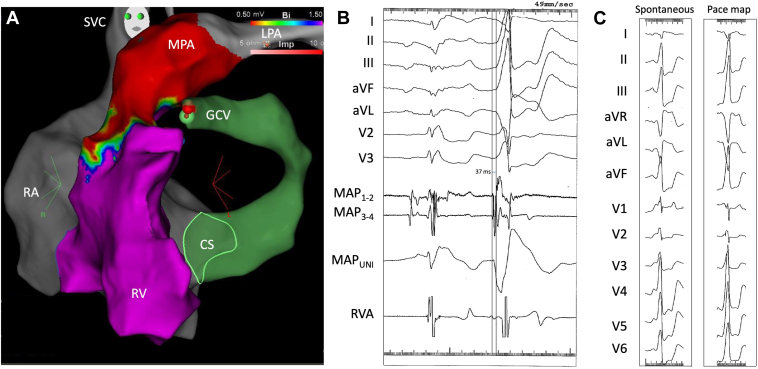

Returning to femoral venous access, the GCV was mapped using robotic magnetic guidance. The most distal portion reachable by the mapping catheter was overlying the LV summit adjacent to the posteroseptal RV outflow tract (Figure 2A). Earlier activation during PVCs and runs of nonsustained VT was noted at this site. Ventricular activation preceded the surface QRS by 37 ms and a Q-wave pattern was observed on unipolar mapping (Figure 2B). Pace mapping revealed a 95% match (Figure 2C). Proximity to epicardial coronary arteries was verified prior to ablation by integrating computed tomography angiographic images with 3-dimensional electroanatomic maps (Figure 3). The site of earliest activation within the GCV was 6.1 mm lateral to the left anterior descending coronary artery over the LV summit. At this site, irrigated radiofrequency ablation at an initial power of 20 W resulted in complete abolition of ventricular ectopy within 10 seconds (Figure 4). After a 60-second application, an attempt to consolidate the site with a 25-W ablation lesion was aborted due to a rise in impedance. The procedure was well-tolerated and without complication. The patient was discharged the following day and remained asymptomatic at 10 months of follow-up. Holter monitoring revealed a reduction in PVC burden to <1%.

Figure 2.

Mapping in the great cardiac vein (GCV). A: Left anterior oblique view of an electroanatomic voltage map of the right ventricle (RV), with voltages <0.50 mV shown in red and voltages >1.50 mV shown in purple. The scar below the pulmonary annulus is consistent with the subannular patch repair. Note how the ablation catheter in GCV is adjacent to the septal RV outflow tract. The green sphere indicates the site of the premature ventricular contraction (PVC) recorded in (B) and of the pace map displayed in (C). B: Surface electrocardiographic recordings, bipolar intracardiac electrograms from the distal (MAP1-2) and proximal (MAP3-4) mapping catheter and right ventricular apex (RVA), and unipolar recording from the mapping catheter (MAPUNI) during a sinus beat followed by a spontaneous PVC. At this site, the onset of ventricular activation precedes the surface QRS by 37 ms and a Q-wave pattern is noted on the unipolar recording. C: QRS morphology of a spontaneous PVC followed by a paced ventricular beat. The pace mapping algorithm detected a match of 95%. CS = coronary sinus; LPA = left pulmonary artery; MPA = main pulmonary artery; RA = right atrium; SVC = superior vena cava.

Figure 3.

Assessment of proximity to coronary arteries. Computed tomography (CT) angiographic images of the aorta and proximal coronary arteries in anteroposterior (A) and left anterior oblique (B) views. C: CT imaging is integrated with electroanatomic mapping in a left anterior oblique view with caudal angulation. The site of successful ablation (green sphere) is over the septal left ventricular (LV) summit adjacent to the posteroseptal right ventricle outflow tract (RVOT). Cx = circumflex artery; GCV = great cardiac vein; LAD = left anterior descending artery; RCA = right coronary artery; RV = right ventricle.

Figure 4.

Catheter ablation in the left ventricular (LV) summit. A: Left anterior oblique view of activation mapping of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). Local activation at a distal portion of the great cardiac vein (GCV; in red) overlying the LV summit precedes the site of earliest activation in the posteroseptal right ventricle outflow tract (RVOT). The map is tilted caudally to show the relationship between the site of successful ablation and earliest activation in the RVOT. B: Interruption of ventricular bigeminy during irrigated radiofrequency ablation in the GCV. IVC = inferior vena cava; SVC = superior vena cava.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of successful VT ablation in the GCV coursing over the LV summit in a patient with TOF. The case highlights the importance of the infundibular septum in arrhythmogenesis and elucidates the anatomic complexity of this region, which is highly relevant to catheter ablation. Indeed, the infundibular septum is displaced anteriorly and superiorly in TOF, which gives rise to the classic subaortic ventricular septal defect, overriding aorta, and subpulmonary stenosis. It is anatomically located between the ventriculo-infundibular fold and the septomarginal trabecula, which connects the interventricular septum to the anterior wall of the RV.6 The infundibular septum is an integral component of the most common anatomic isthmus associated with VT in TOF, a region that extends from the ventricular septal defect patch to the pulmonary annulus.3 Histologic studies show that interstitial fibrosis is often present in the infundibular septum prior to surgery,7 which, combined with the added insult of surgical scarring, could provide the substrate for slow conduction that promotes reentrant circuits and triggered activity. Although it cannot be definitively established that the patient’s VT was related to TOF or its sequelae, the presence of structural heart disease and adjacent scar precludes a purely “idiopathic” designation.

In patients with TOF, the thickness of the infundibular septum can range from a slim layer of fibrous tissue to a massively hypertrophied myocardium.6 Although the infundibulum can be approached from the right side for catheter ablation, excessive hypertrophy and/or graft material may prevent the isthmus from being transected or a focal source from being reached. In such cases, left-sided ablation within the aortic root has been described.4 Herein, we expand possibilities for accessing sites deep within the infundibulum to include the GCV overlying the LV summit. In the case presented with ineffective right-sided ablation, mapping of the aortic root, endocardial LV outflow tract, and GCV identified earliest ventricular activation within the GCV. Importantly, as the GCV ascends in the anterior ventricular sulcus and over the LV summit, which is bound by left anterior descending and circumflex arteries, it runs adjacent and lateral to the left anterior descending artery.8 Proximity to coronary arteries should, therefore, be verified before ablating within the GCV. The septal portion of the LV summit may be considered part of the infundibular septum, as the summit's deep components can blend with the septal RV outflow tract. The veins draining the infundibular septum empty into the GCV and can exhibit significant anatomic variation in size and number, ranging from a single dominant conal branch to multiple branches that supply the infundibular region.

A VT origin deep within the infundibulum combined with the altered anatomy in TOF renders electrocardiography algorithms less precise for localization. For example, according to Park and Della Rocca algorithms, the rS pattern in V1 combined with the inferior axis, transition in V3, and R in V6 is compatible with a site of origin either in the posterior RV outflow tract or right coronary cusp.9,10 Additional criteria, such as the R wave in lead I and absence of a broad R wave in V2 tip the balance toward an origin in the posterior RV outflow tract.9,10 No electrocardiography VT localization algorithm was specifically developed for patients with TOF. Finally, the use of robotic magnetic navigation was deemed helpful in steering the ablation catheter within the GCV due to ease of maneuverability and the less traumatic nature of its soft and pliable shaft.11 Extra caution should be exerted when handling more rigid manual catheters within this structure.

Conclusion

The infundibular septum is the predominant site of VT in patients with TOF. Although catheter ablation can be addressed via a right-sided approach in most patients, alternative strategies may be necessary when ablation is impeded by significant infundibular hypertrophy or intervening graft material. The GCV course adjacent to the posteroseptal RV outflow tract and over the LV summit making mapping and ablation within this region a viable option in select cases of unsuccessful right-sided ablation, provided a safe distance from coronary arteries is confirmed.

Disclosures

Dr. Aguilar has received consultant and speaker fees from Biosense Webster and Abbott. The remaining authors have no relevant potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Geneviève Tetreault Lefebvre for her expert technical support.

Funding Sources

Dr. Khairy is supported by the André Chagnon Research Chair in Electrophysiology and Congenital Heart Disease.

References

- 1.Khairy P., Harris L., Landzberg M.J., et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in tetralogy of Fallot. Circulation. 2008;117:363–370. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.726372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bessiere F., Waldmann V., Combes N., et al. Ventricular arrhythmias in adults with congenital heart disease, part I: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:1108–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapel G.F., Sacher F., Dekkers O.M., et al. Arrhythmogenic anatomical isthmuses identified by electroanatomical mapping are the substrate for ventricular tachycardia in repaired tetralogy of Fallot. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:268–276. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapel G.F., Reichlin T., Wijnmaalen A.P., et al. Left-sided ablation of ventricular tachycardia in adults with repaired tetralogy of Fallot: a case series. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:889–897. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khairy P., Landzberg M.J., Gatzoulis M.A., et al. Value of programmed ventricular stimulation after tetralogy of Fallot repair: a multicenter study. Circulation. 2004;109:1994–2000. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126495.11040.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson R.H., Tynan M. Tetralogy of Fallot—a centennial review. Int J Cardiol. 1988;21:219–232. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(88)90100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhury U.K., Sathia S., Ray R., Singh R., Pradeep K.K., Venugopal P. Histopathology of the right ventricular outflow tract and its relationship to clinical outcomes and arrhythmias in patients with tetralogy of Fallot. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das S.K., Hawson J., Koh Y., et al. Left ventricular summit arrhythmias: state-of-the-art review of anatomy, mapping, and ablation strategies. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2024;10:2516–2539. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2024.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park K.M., Kim Y.H., Marchlinski F.E. Using the surface electrocardiogram to localize the origin of idiopathic ventricular tachycardia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:1516–1527. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Della Rocca D.G., Gianni C., Mohanty S., Trivedi C., Di Biase L., Natale A. Localization of ventricular arrhythmias for catheter ablation: the role of surface electrocardiogram. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2018;10:333–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ccep.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khairy P., Dyrda K., Mondesert B., et al. Overcoming access challenges to treat arrhythmias in patients with congenital heart disease using robotic magnetic-guided catheter ablation. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5432. doi: 10.3390/jcm13185432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]