Abstract

Background

Benign airway stenosis (BAS) is a disease characterized by the formation of fibrotic tissue leading to airway stenosis with unclear underlying molecular mechanisms. This study aimed to identify the key genes regulating fibrosis in BAS.

Methods

In this study, the fibrotic mechanism of BAS was explored through combined transcriptomic and proteomic analysis. We collected tracheal samples from day 7 of a mouse model of BAS, as well as from normal control mice. These samples underwent transcriptomic and proteomic sequencing, followed by integrative analysis to identify key genes associated with the condition. Subsequently, we assessed airway fibrosis in the BAS model mice after treatment with an inhibitor targeting the identified gene.

Results

The analysis revealed 4,336 significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at the transcriptomic level and 1,634 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) at the proteomic level. Through cross-omics integrative analysis, 195 upregulated genes [designated as correlated DEGs and DEPs (cor-DEGs-DEPs)] exhibited significant concordance in expression patterns at both messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein levels, forming differentially co-expressed gene-protein pairs. Utilizing a combined analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics, we identified the ARG1 gene as a significant factor in this process. Inhibition of ARG1 was shown to alleviate the fibrotic progression associated with BAS.

Conclusions

ARG1 may play a key role in the progression of BAS, which may provide a promising therapeutic strategy for BAS.

Keywords: Benign airway stenosis (BAS), fibrosis, transcriptome sequencing, proteome sequencing, ARG1

Highlight box.

Key findings

• A total of 195 upregulated correlated differentially expressed genes and proteins (cor-DEGs-DEPs) genes were finally identified between the benign airway stenosis (BAS) and control groups. Four genes showed the most significant associations: ARG1, Crab1, Crab2, and Ngp. ARG1 was closely associated with fibrosis. The application of the ARG1 inhibitor 2(S)-amino-6-boronohexanoic acid (ABH) further proved the upregulation of ARG1 in the fibrosis process of BAS compared with the control group.

What is known and what is new?

• BAS is a difficult and harmful disease, which is usually caused by a long period of tracheal intubation or tracheotomy.

• ARG1 may play a key role in the process of BAS. Inhibition of ARG1 was proved to alleviate the fibrotic progression associated with BAS.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• These findings may shed light on the mechanism of the fibrosis process of BAS and provide new treatment targets for BAS.

Introduction

Benign airway stenosis (BAS) is a difficult and harmful disease, which is usually caused by a long time of tracheal intubation or tracheotomy (1). Amid the rising prevalence of public health emergencies, exemplified by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in recent years, tracheotomy, endotracheal stenting, and tracheal intubation have emerged as critical interventions in intensive care medicine (2). The incidence of BAS due to these measures has also increased and is emerging as a major challenge to clinical care during public health events (3). BAS is fibroproliferative in nature and after injury to the trachea, this leads to the aggregation of various cells and the release of cytokines that promote fibrosis in the wound (4). Currently, the mainstay of treatment for BAS is bronchoscopic intervention through cryotherapy, electrocautery, balloon bronchoplasty or dilatation (5). However, these treatments carry the risk of secondary stenosis, making BAS a challenge in the field of respiratory intervention. The molecular mechanism of airway stenosis has not been thoroughly studied. Thus, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying BAS represents a critical imperative for advancing targeted therapeutic strategies and optimizing clinical outcomes in airway management. The study of fibrotic diseases through transcriptomic and proteomic analysis has gained significant traction in recent years, offering profound insights into the underlying mechanisms of fibrosis (6,7). Transcriptomics reveals key gene expression changes associated with fibrosis and aids in identifying critical regulatory pathways (8). It enables dynamic monitoring of molecular alterations, enhancing the understanding of disease progression. Additionally, it helps discover potential biomarkers for early diagnosis (9). Proteomics characterizes protein states and functions, identifying specific proteins linked to fibrosis (10). It uncovers crucial post-translational modifications for disease development and provides biomarkers reflecting disease status. Increasing evidence suggests that systematic integration of transcriptomic and proteomic datasets provides an indispensable framework for delineating pan-dimensional gene expression dynamics and deciphering their multilayered regulatory architecture across biological scales (11,12). However, there is no multi-omics method to explore the molecular mechanism of BAS.

In this study, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses were performed in mice with BAS to understand the molecular mechanisms of fibrosis in BAS. Further bioinformatics analysis was performed to investigate the molecular mechanism. In addition, the present study was also to investigate the role of ARG1 in the fibrotic process of BAS and assess the potential therapeutic effects of an ARG1 inhibitor. We present this article in accordance with the ARRIVE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-1987/rc).

Methods

Animal experiments

Male eight-week-old mice with a C57BL/6 background were purchased from the SPF (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Experimental mice were housed in independently ventilated cages (IVC) with free access to sterilized feed and filtered water. Standardized environmental conditions (23±2 ℃ temperature, 55%±5% humidity, 12-hour light/dark cycle) were maintained to minimize external interference with experimental outcomes. In the sequencing experiment, 10 mice were randomly divided into two groups: the control group and the BAS group. In the experiment to verify the function of ARG1, nine mice were randomly divided into three groups: control group, BAS group, and BAS + 2(S)-amino-6-boronohexanoic acid (ABH) (ARG1 inhibitor) group.

The BAS mouse model was induced by scraping the tracheal mucosa. The pretracheal tissue was layered down to expose the trachea, which was then incised transversely for two-thirds of its circumference below the cricoid cartilage. A 1 mm diameter brush was inserted 6 mm deep into the trachea via a 20 G safety intravenous (IV) catheter. The cannula was then pulled out, leaving the brush to scrape the tracheal wall three times, causing a fibrotic process after injury, which leads to BAS.

Finally, the trachea was sutured using 6-0 thread, while the skin and subcutaneous tissue were closed with 3-0 sutures. Mice in the BAS + ABH group were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) ABH (MedChemExpress; 100 µg/day) (13) 2 h before modeling and for 7 consecutive days, while the control group was administered i.p. saline.

After the modeling procedure, the mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) mixture. The pretracheal tissues were collected and stored at −80 ℃. Ethical approval for this animal study was given by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University (No. CHEC2021-006), in compliance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals. A protocol was prepared before the study without registration.

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and Masson’s trichrome staining

Tracheal specimens underwent immobilization in 4% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde for 24 h prior to paraffin embedding. Serial 3 µm axial sections were mounted on slides and subjected to histological evaluation through HE staining and Masson’s trichrome collagen visualization. Quantitative morphometric analysis was performed using ImageJ with standardized protocols. Measurements were taken from the medial side of the tracheal cartilaginous ring to the basement membrane of the airway epithelium (14,15).

Immunohistochemistry

Tracheal paraffin-embedded specimens were sectioned at 3 µm thickness using a rotary microtome, followed by sequential deparaffinization in xylene gradients and antigen retrieval via microwave-mediated citrate buffer treatment. Tissue sections underwent protein blockade using a commercial blocking reagent (Beyotime Biotechnology) prior to overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies targeting arginase-1 (anti-ARG1, dilution 1:200, 93668T, Cell Signaling Technology). Following three phosphate buffered saline (PBS) washes (5 min/wash), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Abmart, Shanghai, China) were applied at room temperature for 120 min. Digital histomorphometry was conducted using ImageJ with color deconvolution algorithms, where ARG1-positive regions were quantified as [(DAB + pixel area)/(total tissue area) ×100%] through adaptive thresholding.

Immunofluorescence

Tracheal tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 24 hours, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned into 3-µm-thick slices. After deparaffinization and antigen retrieval, sections were blocked and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-collagen I (anti-COL1) (dilution 1:100, ab316222, Abcam) and anti-α-smooth muscle actin (anti-αSMA) (dilution 1:200, 19245, Cell Signaling Technology). Following PBS washes, secondary antibodies were applied for 2 hours at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and slides were mounted with anti-fade medium. Fluorescence images were captured and analyzed using ImageJ to quantify staining intensity.

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from tracheal tissues of mice by radio-immuno precipitation assay buffer (RIPA) lysate containing protease/phosphatase inhibitor. After the protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) method, the sample was mixed with 5× sample buffer and boiled at 95 ℃ for 10 minutes. A 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel was prepared with the same amount of protein (40 µg/well) and the prestained protein marker (#WJ103, Epizyme). The gel was electrophoresed at constant pressure, 80–120 V, for 60 min. The proteins were transferred to 0.45 µm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane by wet transfer method, which was enclosed in 5% skim milk at room temperature for 1 hour, and the primary antibody was added successively, including ARG1 (1:5,000, 16001-1-AP, Proteintech) and Actin (1:5,000, 66009-1-Ig, Proteintech), incubate at 4 ℃ overnight, Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) washed the film 3 times (10 min/time), and added horseradish peroxidase (HRP) labeled secondary antibody (1:8,000, SA00001-2, Proteintech) and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. After enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) was developed, the signal was collected by a Tanon chemiluminescence imaging system (Tanon, Shanghai, China), and the band gray value was quantified by ImageJ software (β-Actin was used as the internal parameter).

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Tracheal tissue and cellular RNA were extracted using the RNeasy kit (Vazyme), followed by the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) with the One-step iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme) on a QuantStudio™ 3 System (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and GAPDH was used as the reference gene for normalization. Relative gene expression levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. The qPCR primers used in this study.

| Gene name | Prime |

|---|---|

| ARG1 | CTCCAAGCCAAAGTCCTTAGAG |

| AGGAGCTGTCATTAGGGACATC | |

| GAPDH | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

| TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and data processing

Total RNA was extracted from samples using Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and integrity of the RNA were assessed using a Bioanalyzer 2100, and only samples with an RNA integrity number (RIN) value greater than 7.0 were used for sequencing library preparation. For messenger RNA (mRNA) enrichment, 5 µg of total RNA was subjected to two rounds of purification with Dynabeads Oligo (dT). The purified mRNA was fragmented using divalent cations and reverse transcribed into cDNA with SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase. Second-strand synthesis was performed with U-labeled nucleotides, and the resulting cDNA fragments were ligated to dual-index adapters, followed by size selection using AMPureXP beads. After uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG) treatment, the adapter-ligated products were amplified by PCR, generating a final cDNA library with an average insert size of 300±50 bp. Paired-end sequencing (PE150) was performed on the Illumina Novaseq™ 6000 platform.

Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2 (for comparisons between groups) and edgeR (for comparisons between individual samples). Genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) below 0.05 and an absolute fold change of ≥1 were considered differentially expressed. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed to identify functional enrichment patterns and interpret differences in gene function across samples. GO and KEGG analyses were carried out using the clusterProfiler (v4.1.3) package in R. Functions with P-values less than 0.05 were considered significantly enriched. Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the GSEA software (v4.1.0) with the MSigDB v7.5.1 gene set collection. All RNA-seq data analysis was performed using the OmicStudio tools created by LC-BIO Co., Ltd (Hangzhou, China) at https://www.omicstudio.cn/cell.

Data-independent acquisition (DIA) protein sequencing and data processing

Protein concentration in the supernatant was measured using the BCA protein assay. From each sample, 150 µg of protein was taken, and 3 µg of trypsin was added to achieve a protein-to-enzyme ratio of 50:1. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 14–16 hours to allow enzymatic digestion. After digestion, the peptides were desalted using Waters solid-phase extraction cartridges and then vacuum-dried. The dried peptides were re-suspended in pure water and stored at −20 °C until further analysis by Nano-LC-MS/MS.

Data from DIA were analyzed using the library-free method in DIA-NN. MS/MS spectra were matched to protein sequences obtained from the Uniprot database with the following parameters: enzyme—Trypsin/P; maximum missed cleavages—2; fixed modification—carbamidomethylation (C); variable modifications—oxidation (M) and acetylation (protein N-term); precursor mass tolerance—20 ppm; fragment mass tolerance—0.05 Da. Results were filtered using a 1% FDR, and only protein groups that passed this threshold were used for further analysis. Statistical analysis was carried out using R (version 4.0.0). Hierarchical clustering was conducted using the pheatmap package, and principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the metaX package. Correlations between samples were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. For differential protein expression, a t-test was applied with a significance cutoff of P≤0.05 and a fold change ≥1.2. KEGG pathway and GO enrichment analysis were conducted using a hypergeometric test to annotate the proteins. GSEA (v4.1.0) with the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) was used to evaluate enrichment of gene sets within specific GO terms. A |normalized enrichment score| >1, nominal (NOM) P<0.05, and FDR q<0.25 were considered significant. Subcellular localization predictions were performed using WoLF PSORT, and protein-protein interactions (PPI) were investigated through the STRING database, with interactions having a confidence score ≥0.4 used for subsequent mapping. All DIA protein sequencing analysis was performed using the OmicStudio tools created by LC-BIO Co., Ltd (Hangzhou, China) at https://www.omicstudio.cn/cell.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) throughout the study. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Intergroup comparisons were analyzed using Student’s t-test, whereas multigroup comparisons were evaluated through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Kruskal-Wallis testing. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

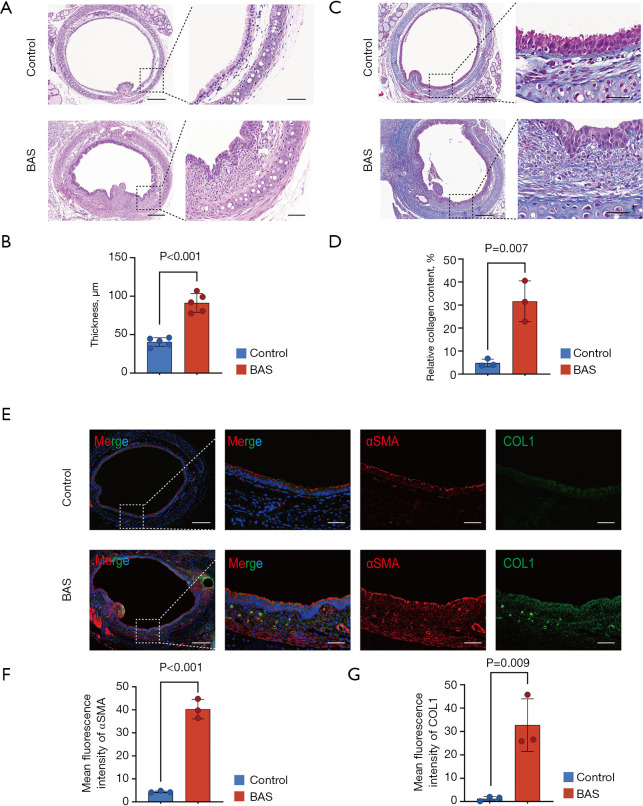

Tracheal fibrosis appeared in BAS mice on the 7th day after modeling

Seven days after modeling, HE staining demonstrated sarcomeric hyperplasia and excessive collagen deposition in BAS mice trachea, resulting in significant thickening of the lamina propria (LP) compared with control mice (Figure 1A,1B). This pathological alteration was corroborated by Masson’s trichrome staining, which quantitatively confirmed a substantial increase in collagen fiber accumulation within the tracheal tissue of BAS mice relative to controls (Figure 1C,1D). Subsequently, the fibroblast activation markers αSMA and COL1 were analyzed by immunofluorescence, with the results indicating that there was a high-level expression of αSMA and COL1 in the trachea of BAS mice (Figure 1E-1G). These results suggested that the tracheae of mice are in the fibrosis stage on the 7th day after tracheal injury; thus, this time point should be chosen in later studies of fibrosis in airway stenosis.

Figure 1.

Tracheal fibrosis phase in the BAS mice model at the 7th day. (A) Representative HE-stained tracheal sections at day 7 post-induction, highlighting subepithelial fibrosis and LP thickening in BAS mice vs. controls. Scale bars: 200 µm (first column), 50 µm (second column). (B) Masson’s trichrome staining of tracheal tissue demonstrates increased collagen deposition (blue) in BAS mice compared to controls at day 7. Scale bars: 200 µm (first column), 50 µm (second column). (C,D) Quantitative histomorphometric analysis revealed an increase in LP thickness (n=5/group) and elevation in collagen content (n=3/group) in BAS mice vs. controls. (E) Immunofluorescence co-staining of αSMA (red) and COL1 (green) showing enhanced fibrotic remodeling in BAS tracheae. Nuclei counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 200 µm (first column), 50 µm (second to fourth columns). (F,G) Fluorescence intensity quantification confirmed significant upregulation of αSMA and COL1 in BAS mice vs. controls (n=3/group). Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test in C,D,F,G. BAS, benign airway stenosis; COL1, collagen I; DAPI, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HE, hematoxylin and eosin; LP, lamina propria; SEM, standard error of the mean; αSMA, α-smooth muscle actin.

Transcriptomics in the mouse model of BAS

A total of 10 cDNA libraries were constructed, five of which were extracted from tracheal tissue in the BAS group, and the others were extracted from tracheal tissue in the control group. The results of PCA showed significant differences existed between the two groups (Figure 2A). After filtering the original sequencing data with an expression log2 |fold change| >2, there were 4,336 quantifiable differentially expressed genes (DEGs), of which 2,123 were upregulated and 2,213 were downregulated in the BAS group compared to the control group (Figure 2B). These DEGs were visualized by a volcano map and a heatmap (Figure 2C, 2D). The DEGs of TOP20 were displayed by a heat map bar graph (Figure 2E). Of these genes, most are associated with fibrosis (Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, Col5a1, Col5a2, Mmp3, P4ha3, and Tnn). Further, GO enrichment analysis of these 4,336 DEGs was conducted by annotating and categorizing them into molecular function (MF), cellular component (CC), and biological process (BP) categories. The top 20 enriched terms were shown in Figure 2F. Extracellular matrix organization, cell adhesion, extracellular region, extracellular space, extracellular matrix, collagen-containing extracellular matrix, collagen trimer, extracellular matrix structural constituent conferring tensile strength and extracellular matrix structural constituent were highly enriched, which indicated the fibrosis process after trachea damage was activated. Likewise, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the DEGs were enriched in fibrosis-related pathways, such as extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interaction, cell adhesion molecules, and focal adhesion (Figure 2G).

Figure 2.

Transcriptomics in the mouse model of BAS. (A) PCA delineating distinct transcriptomic profiles between BAS and control groups (n=5/group). (B) Bar graphs show upregulated and downregulated DEGs (log2 |fold change| ≥2 and FDR ≤0.05). (C) Heatmap analysis of the DEGs. (D) Volcano plots of DEGs. (E) The heatmap bar graph shows the top 20 DEGs. (F) Top 20 enriched GO terms. (G) Top 20 enriched KEGG pathways. BAS, benign airway stenosis; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; FC, fold change; FDR, false discovery rate; GO, Gene Ontology; IDs, identifiers; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; PCA, principal component analysis.

Proteomics in the mouse model of BAS

To explore the mechanism of trachea fibrosis at the protein level, we depicted protein profiling of the BAS group and control group by label-free proteomics analysis. PCA revealed strong intra-group reproducibility and distinct inter-group separation (Figure 3A). Using a differential expression threshold of log2 |fold change| ≥1.2, proteomic profiling identified 1,634 significantly altered proteins, with 796 upregulated and 838 downregulated species in the model group vs. controls (Figure 3B). These differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were visualized by volcano map and heatmap (Figure 3C,3D). Subcellular localization analysis of these DEPs showed that there were 309 differential proteins in the extracellular matrix (Figure 3E), which suggested that these proteins may be pivotal in the fibrotic processes that characterize airway stenosis. Further, GO enrichment analysis of these 1,634 DEPs was conducted by annotating and categorizing them into MF, CC, and BP categories. The top 20 enriched terms were shown in Figure 3F. Extracellular space and collagen-containing extracellular matrix were highly enriched, which were associated with the activation of fibrosis. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the DEPs were enriched in cell metabolism, energy production, and cell signaling (Figure 3G). These pathways could indirectly promote fibrosis progression.

Figure 3.

Proteomics in the mouse model of BAS. (A) PCA delineating distinct proteomics profiles between BAS and control groups (n=5/group). (B) Bar graphs show upregulated and downregulated DEPs (log2 |fold change| ≥1.2 and FDR ≤0.05). (C) Heatmap analysis of the DEPs. (D) Volcano plots of DEPs. (E) Bar graphs show the subcellular localization analysis of DEPs. (F) Top 20 enriched GO terms. (G) Top 20 enriched KEGG pathways. BAS, benign airway stenosis; DEPs, differentially expressed proteins; FDR, false discovery rate; GO, Gene Ontology; IDs, identifiers; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; PCA, principal component analysis.

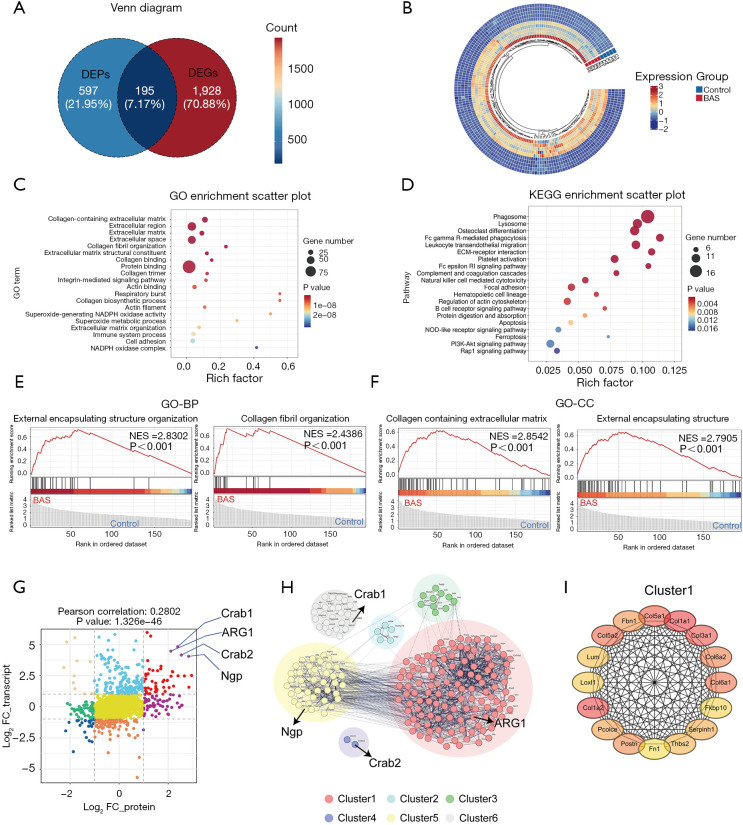

Combined analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics

Integrated transcriptomic-proteomic analysis identified 195 co-upregulated gene-protein pairs demonstrating concurrent significant alterations at both transcriptional and translational levels in the model group vs. controls (Figure 4A). This multi-omics integration specifically targeted genes and proteins showing coordinated upregulation (log2 |fold change| > threshold) with concordant expression patterns across mRNA and protein dimensions. These upregulated genes were visualized by heatmap (Figure 4B). Further, GO enrichment analysis found that most of the terms were directly related to fibrosis, such as collagen-containing extracellular matrix, extracellular region, extracellular matrix, extracellular space, collagen fibril organization, extracellular matrix structural constituent, collagen binding, collagen trimer, actin binding, collagen biosynthetic process, respiratory burst, actin filament, extracellular matrix organization, and cell adhesion (Figure 4C). Similarly, KEGG analysis revealed significant enrichment of fibrosis-related pathways, such as ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion, and regulation of actin cytoskeleton (Figure 4D). Subsequently, GSEA was performed according to the GO database to further identify the biological functions associated with the process of fibrosis. The results showed that the external encapsulating structure organization, collagen fibril organization, collagen-containing extracellular matrix, and external encapsulating structure were enriched (Figure 4E,4F). The nine-quadrant graph tool was used to analyze the correlation between protein and mRNA expression, and the red dots in the quadrant represented the expression of upregulated mRNA corresponding to the related upregulated protein (Figure 4G). Four genes showed the most significant associations: ARG1, Crab1, Crab2, and Ngp (Figure 4G). The potential interaction network of the 195 upregulated correlated DEGs and DEPs (cor-DEGs-DEPs) genes was examined with STRING analysis, and was grouped into six clusters by K-means cluster analysis (Figure 4H). ARG1, which was associated with fibrosis, was one of the top genes in cluster 1 among these (Figure 4I). Therefore, we hypothesized that ARG1 may play a role in fibrosis related to airway stenosis.

Figure 4.

Combined analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics. (A) Venn diagram of upregulated DEGs and the upregulated DEPs quantity. (B) Heatmap analysis of the upregulated cor-DEGs-DEPs genes. (C) Top 20 enriched GO terms. (D) Top 20 enriched KEGG pathways. (E) GSEA analysis of increasingly expressed genes showing the top 2 enriched GO-BP in the BAS group compared with the control group. (F) GSEA analysis of increasingly expressed genes showing the top 2 enriched GO-CC in the BAS group compared with the control group. (G) Nine-quadrant diagram analyzes the correlation between DEGs and DEPs. The expression of differential proteins and differential genes was categorized into nine quadrants (each quadrant is of a different color), where red represents high expression in both. (H) PPI of upregulated cor-DEGs-DEPs genes. (I) Top genes of cluster 1 in the PPI network. BAS, benign airway stenosis; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; DEPs, differentially expressed proteins; FC, fold change; GO, Gene Ontology; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; NES, normalized enrichment score; PPI, protein-protein interaction.

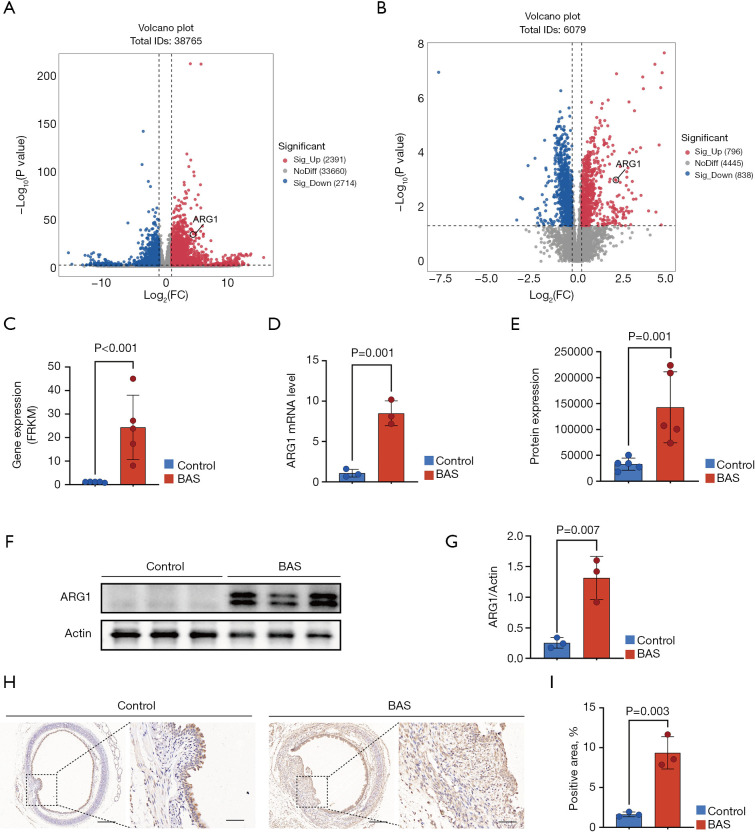

ARG1 was upregulated in the trachea of mice with BAS at the fibrotic stage

By combined transcriptome and proteome analysis, we found that ARG1 may be involved in the fibrotic process of airway injury. The volcano plot demonstrated that ARG1 was upregulated in both transcriptome sequencing and proteome sequencing (Figure 5A,5B). At the mRNA level, ARG1 was significantly upregulated in the BAS group compared to the control group (Figure 5C). Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) verification results also showed that ARG1 was highly expressed in the BAS group (Figure 5D). At the protein level, ARG1 was significantly upregulated in the BAS group compared to the control group (Figure 5E). Similarly, western blot results showed that ARG1 expression was upregulated in the trachea of BAS mice (Figure 5F,5G). Immunohistochemical results showed that ARG1 expression was significantly higher in tracheal sections of BAS mice than in those of controls (Figure 5H,5I). These results suggested that ARG1 was highly expressed in the trachea of mice with BAS at the fibrotic stage.

Figure 5.

ARG1 expression in the trachea of a mouse with BAS at the fibrotic stage. (A) Differential expression analysis identified ARG1 as a top-ranked gene in the volcano plots of transcriptomic. (B) Differential expression analysis identified ARG1 as a top-ranked protein in volcano plots of proteomic datasets. (C) ARG1 expression levels in transcriptome sequencing. (D) RT-qPCR validation confirmed higher ARG1 transcript levels in the BAS group vs. controls (n=3/group). (E) ARG1 expression levels in proteomic sequencing. (F,G) Western blot demonstrated that increased ARG1 protein expression in BAS group vs. controls (n=3/group). (H,I) Immunohistochemical staining revealed intensified ARG1 signal in the BAS group vs. controls (n=3/group). Scale bars indicate 200 µm (left) and 50 µm (right). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. A Student’s t-test was used in D,G,I. BAS, benign airway stenosis; FC, fold change; FRKM, fuzzy robust K-means; IDs, identifiers; mRNA, messenger RNA; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean.

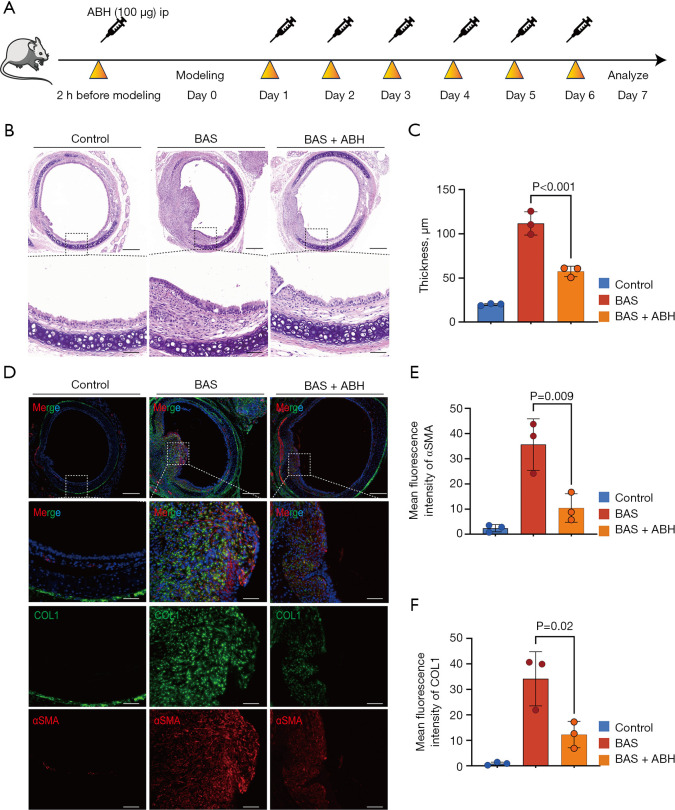

Inhibition of ARG1 attenuated the development of BAS

To confirm the effect of ARG1 on the progression of BAS, mice were treated with the ARG1 inhibitor ABH (Figure 6A). On the 7th day after modeling, the group of mice with BAS that were treated with ABH showed a significant reduction in the development of granulation tissue, proliferation of the airway epithelium, collagen deposition, and degree of fibrosis compared to the BAS group of mice treated with PBS, as observed on histological examination (Figure 6B). Moreover, quantitative assessment of LP thickness revealed a thinner LP in the ABH-treated BAS mice compared to the PBS-treated BAS mice (Figure 6C). Immunofluorescence quantification revealed significant upregulation of αSMA and COL1 in BAS model mice compared to controls. Notably, pharmacological intervention with ABH substantially attenuated this fibrotic phenotype, demonstrating reductions in αSMA and COL1 fluorescence intensity, respectively, vs. PBS-treated BAS counterparts (Figure 6D-6F). These results suggested that ARG1 inhibition alleviated fibrotic progression in BAS.

Figure 6.

Suppression of the ARG1 attenuates the development of BAS. (A) Experimental timeline of ABH treatment (20 mg/kg, i.p.) administered daily from day 0 to day 7 post-BAS induction. (B) HE-stained tracheal sections demonstrating attenuated LP thickening in ABH-treated BAS mice compared to PBS-treated BAS controls at day 7. Scale bars: 200 µm (first row), 50 µm (second row). (C) Morphometric quantification revealed a reduction in LP thickness in ABH-treated BAS mice vs. BAS controls (n=3/group). (D) Immunofluorescence staining showing αSMA (red), COL1 (green) in tracheal tissues. ABH treatment substantially reduced fibrotic marker expression. Scale bars: 200 µm (first row), 50 µm (second to fourth rows). (E,F) Quantitative fluorescence intensity analysis confirmed a decrease in αSMA and COL1 expression with ABH intervention vs. BAS controls (n=3/group). Data expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test in C,E,F. ABH, 2(S)-amino-6-boronohexanoic acid; ANOVA, analysis of variance; BAS, benign airway stenosis; COL1, collagen I; DAPI, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HE, hematoxylin and eosin; i.p., intraperitoneally; LP, lamina propria; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; SEM, standard error of the mean; αSMA, α-smooth muscle actin.

Discussion

In recent years, the rising use of critical care procedures such as endotracheal intubation and tracheotomy has led to an increased incidence of BAS (16). While current respiratory interventions can manage symptoms in the short term, they also pose a risk of restenosis (17). Consequently, it is imperative to identify therapeutic targets to prevent BAS.

At present, there are increasing reports on omics methods to study the molecular mechanisms of fibrotic diseases. Transcriptomic analysis enables the comprehensive profiling of gene expression patterns, identifying key regulatory pathways involved in the fibrotic response (18). Meanwhile, proteomic studies provide critical information about protein modifications, interactions, and abundance, shedding light on the dynamic changes that occur during the fibrotic process (19). In this study, 4,336 genes and 1,634 proteins were differentially expressed in mice with BAS. These DEGs and DEPs were mainly enriched in fibrosis-related terms, which was consistent with the process of fibrosis after airway injury. These fibrosis-related terms were mainly related to extracellular matrix and collagen deposition. The ECM provides structural support to cells and regulates their behavior. In the context of fibrosis, the balance of ECM components is disrupted, resulting in the excessive accumulation of collagen and other matrix proteins (20). Collagen, the most abundant protein in the ECM, experiences increased synthesis and reduced degradation during the fibrotic process (21).

Integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data can unveil novel biomarkers for early diagnosis and prognosis, as well as potential therapeutic targets (22). By integrating upregulated DEGs and DEPs, 195 upregulated cor-DEGs-DEPs genes at both the mRNA and protein levels were screened. Then, STRING analysis and K-means cluster analysis were performed on the 195 genes. Four genes showed significant associations: ARG1, Crab1, Crab2, and Ngp, among which ARG1 was found to be the most closely related to fibrosis.

ARG1 is an enzyme that plays a pivotal role in the urea cycle, primarily catalyzing the hydrolysis of arginine into urea and ornithine (23). Urea and ornithine lead to the production of polyamines and proline, both of which are essential for fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis (24). This shift in metabolic pathways promotes fibroblast activation and migration, contributing to the accumulation of fibrotic tissue. Several studies have confirmed that ARG1 plays a crucial role in the development and progression of fibrosis (25,26). In this study, we found that ARG1 was highly expressed in the trachea of mice with BAS, and ARG1 inhibition could effectively alleviate the fibrotic process of BAS. Therefore, ARG1 was not only a key enzyme in the progression of fibrosis but also a potential therapeutic target that may help slow or reverse the progression of BAS.

Admittedly, there are some limitations in this study. First, the experiments were performed only on mice, which may not apply to humans. Clinical researches are needed in future studies. Secondly, the sample size in this study was small. This may result in the omission of some potential targets in the experiment. Thirdly, attention was paid to the function of ARG1, a target that was closely associated with fibrosis. Other targets (Crab1, Crab2, and Ngp) with significant associations should be drawn to attention in additional experiments.

Conclusions

DEGs and DEPs between the BAS and the control group were identified by a mouse model in our study. Four genes showed the most significant associations (ARG1, Crab1, Crab2, and Ngp) via combined analysis of transcriptomics and proteomics. ARG1, which was associated with fibrosis, was found upregulated in this study. These findings provide critical insights into the molecular mechanisms of BAS and provide potential targets for subsequent clinical treatment.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Ethical approval for this animal study was given by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University (No. CHEC2021-006), in compliance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the ARRIVE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-1987/rc

Funding: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82270112, No. 82000102).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-1987/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Sharing Statement

Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-1987/dss

References

- 1.Chang E, Wu L, Masters J, et al. Iatrogenic subglottic tracheal stenosis after tracheostomy and endotracheal intubation: A cohort observational study of more severity in keloid phenotype. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2019;63:905-12. 10.1111/aas.13371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piazza C, Lancini D, Filauro M, et al. Post-COVID-19 airway stenosis treated by tracheal resection and anastomosis: a bicentric experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2022;42:99-105. 10.14639/0392-100X-N1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangiameli G, Perroni G, Costantino A, et al. Analysis of Risk Factors for Tracheal Stenosis Managed during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Retrospective, Case-Control Study from Two European Referral Centre. J Pers Med 2023;13:729. 10.3390/jpm13050729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchioni A, Tonelli R, Andreani A, et al. Molecular Mechanisms and Physiological Changes behind Benign Tracheal and Subglottic Stenosis in Adults. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:2421. 10.3390/ijms23052421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravikumar N, Ho E, Wagh A, et al. The role of bronchoscopy in the multidisciplinary approach to benign tracheal stenosis. J Thorac Dis 2023;15:3998-4015. 10.21037/jtd-22-1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weckerle J, Mayr CH, Fundel-Clemens K, et al. Transcriptomic and Proteomic Changes Driving Pulmonary Fibrosis Resolution in Young and Old Mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2023;69:422-40. 10.1165/rcmb.2023-0012OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velázquez-Enríquez JM, Ramírez-Hernández AA, Navarro LMS, et al. Proteomic Analysis Reveals Differential Expression Profiles in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Cell Lines. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:5032. 10.3390/ijms23095032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Govaere O, Cockell S, Tiniakos D, et al. Transcriptomic profiling across the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease spectrum reveals gene signatures for steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 2020;12:eaba4448. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aba4448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng X, Zhang Y, Du M, et al. Identification of diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in peripheral immune landscape from coronary artery disease. J Transl Med 2022;20:399. 10.1186/s12967-022-03614-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun J, Tang L, Shan Y, et al. TMT quantitative proteomics and network pharmacology reveal the mechanism by which asiaticoside regulates the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway to inhibit peritoneal fibrosis. J Ethnopharmacol 2023;309:116343. 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Zhou Q, Zhang J, et al. Liver transcriptomic and proteomic analyses provide new insight into the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis in mice. Genomics 2023;115:110738. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2023.110738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi L, Deng J, He J, et al. Integrative transcriptomics and proteomics analysis reveal the protection of Astragaloside IV against myocardial fibrosis by regulating senescence. Eur J Pharmacol 2024;975:176632. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.176632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arlauckas SP, Garren SB, Garris CS, et al. Arg1 expression defines immunosuppressive subsets of tumor-associated macrophages. Theranostics 2018;8:5842-54. 10.7150/thno.26888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillel AT, Namba D, Ding D, et al. An in situ, in vivo murine model for the study of laryngotracheal stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:961-6. 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motz KM, Lina IA, Samad I, et al. Sirolimus-eluting airway stent reduces profibrotic Th17 cells and inhibits laryngotracheal stenosis. JCI Insight 2023;8:e158456. 10.1172/jci.insight.158456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayten O, Iscanli IGE, Canoglu K, et al. Tracheal Stenosis After Prolonged Intubation Due to COVID-19. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2022;36:2948-53. 10.1053/j.jvca.2022.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chrissian AA, Diaz-Mendoza J, Simoff MJ. Restenosis Following Bronchoscopic Airway Stenting for Complex Tracheal Stenosis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2023;30:268-76. 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonatti M, Pitozzi V, Caruso P, et al. Time-course transcriptome analysis of a double challenge bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis rat model uncovers ECM homoeostasis-related translationally relevant genes. BMJ Open Respir Res 2023;10:e001476. 10.1136/bmjresp-2022-001476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enomoto T, Shirai Y, Takeda Y, et al. SFTPB in serum extracellular vesicles as a biomarker of progressive pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 2024;9:e177937. 10.1172/jci.insight.177937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su W, Guo Y, Wang Q, et al. YAP1 inhibits the senescence of alveolar epithelial cells by targeting Prdx3 to alleviate pulmonary fibrosis. Exp Mol Med 2024;56:1643-54. 10.1038/s12276-024-01277-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siadat SM, Ruberti JW. Mechanochemistry of collagen. Acta Biomater 2023;163:50-62. 10.1016/j.actbio.2023.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takemon Y, Chick JM, Gerdes Gyuricza I, et al. Proteomic and transcriptomic profiling reveal different aspects of aging in the kidney. Elife 2021;10:e62585. 10.7554/eLife.62585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mossmann D, Müller C, Park S, et al. Arginine reprograms metabolism in liver cancer via RBM39. Cell 2023;186:5068-5083.e23. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Failla M, Molaro MC, Schiano ME, et al. Opportunities and Challenges of Arginase Inhibitors in Cancer: A Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. J Med Chem 2024;67:19988-20021. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Q, Wang Y, Shi L, et al. Arginase-1 promotes lens epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in different models of anterior subcapsular cataract. Cell Commun Signal 2023;21:236. 10.1186/s12964-023-01210-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang M, Wu Z, Salas SS, et al. Arginase 1 expression is increased during hepatic stellate cell activation and facilitates collagen synthesis. J Cell Biochem 2023;124:808-17. 10.1002/jcb.30403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]