Abstract

With the newly approved RSV preventive strategies enabling universal protection of infants, it is crucial to gain a comprehensive understanding of RSV hospitalization incidence, prior to the introduction of these strategies in order to facilitate an assessment of their impact. Children ≤ 2 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed RSV infection between 2020–2023 in France, Germany, Spain, Italy, and United Kingdom were included and compared with the 2018–2019 season. The population-based incidence was calculated as number of RSV hospitalizations divided by market share-adjusted number of children in the catchment area. Across participating countries, we observed a decrease in RSV hospitalization incidence during the 2020–2021 season due to the COVID-19 pandemic, dropping to 5.9/1000 child-years (95%CI 5.4–6.3) compared with 11.3/1000 child-years (95%CI 10.6–11.9) in 2018–2019. This decline was followed by a rebound in incidence, with rates reaching 13.8/1000 child-years (95%CI 13.0–14.5) in 2021–2022 and 18.8/1000 child-years (95%CI 18.0–19.7) in 2022–2023. Distinct patterns of RSV resurgence were observed across countries. During the 2020–2021 season, there was an increase in PICU admissions (29.5% vs 20.0% pre-pandemic, p < 0.001), despite a lower total number of RSV admissions (610 vs 1,238) compared to the 2018–2019 season.

Conclusions: The population-based incidence of RSV hospitalization in children ≤ 2 years is substantial. Considerable variation in incidence was observed between 2020 and 2023, with an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic followed by a rebound in the subsequent seasons. Our study underscores the importance of RSV surveillance and flexibility in RSV preventive strategies.

|

What is Known: • RSV is a major cause of hospitalization in young children under 5 years of age worldwide. • RSV seasonality was disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

|

What is New: • Distinct patterns of RSV resurgence were observed across five European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an initial decline in incidence of RSV associated hospitalizations in children ≤ 2 years, followed by a rebound in the subsequent seasons, reaching 18.8 per 1,000 child-years (95% CI: 18.0 - 19.7) in 2022-2023. |

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00431-025-06218-1.

Keywords: RSV, Population-based incidence, COVID-19 pandemic, Children, RSV hospitalization

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a major cause of hospitalization and mortality in young children worldwide. It is estimated that approximately 3.6 million RSV-associated acute lower respiratory infection (LRTI) hospital admissions and about 100,000 RSV-attributable deaths in children less than 5 years of age occur globally, with more than 95% of these deaths occurring in developing countries [1]. While premature infants and children with comorbidities such as hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and Down syndrome are at higher risk of RSV hospitalization, the majority of hospitalizations occur in healthy, full-term born infants [2, 3].

Until recently, palivizumab (SYNAGIS™), a short-acting monoclonal antibody was the only preventive option against RSV, indicated for the prevention of RSV among children at increased risk for severe LRTI [4]. However, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have recently approved both a long-acting monoclonal antibody and a maternal RSV vaccination for infant RSV prevention. The long-acting monoclonal antibody BEYFORTUS™ (AstraZeneca AB, Södertälje, Sweden) is indicated for the prevention of RSV LRTI in infants entering their first season, and for children up to 24 months at high risk for severe RSV disease. The maternal RSV vaccine ABRYSVO™ (Pfizer, Inc., NY, USA) is indicated for the prevention of RSV-associated LRTI in infants from birth to six months [5, 6]. Another long-acting monoclonal antibody by Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, is in late stage development [7].

It is important to understand the burden of RSV-associated disease in young infants and children prior to implementing an immunization strategy. A recent multi-country birth cohort study in Europe estimated the incidence of RSV-associated hospitalizations in healthy full-term infants during their first year of life to be 1.8% [2]. Other single-center or single-country studies in Europe have reported rates of RSV-associated hospitalizations ranging from 0.9% to 5.6% for infants less than one year old [8–14]. However, comparing data among countries is challenging due to the lack of standardized outcome reporting and limited availability of population-based incidence rates for direct comparison.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which started in early 2020, greatly disrupted RSV seasonality worldwide [15, 16]; after a prolonged period of no RSV activity during the 2020–2021 winter, RSV rebounded with different patterns across the globe. Even within Europe, there were significant variations among countries [17] that were likely influenced by the COVID-19 prevention measures implemented by each country [18]. Population-based incidence for RSV hospitalization during the most recent RSV seasons, including the COVID-19 period, is understudied. The aim of the ‘Burden of RSV Infection in young Children in European countries’ (BRICE) Study Group was to provide population-based incidence estimates of RSV hospitalization in children aged ≤ 2 years in five European countries between 2020–2023.

Methods

Study design

The BRICE study is a prospective multicenter, multicountry cohort study that included children ≤ 2 years (≤ 24 months) old hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed RSV infection. A total of 10 study sites participated in this study across 5 European countries: Spain (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago, Santiago de Compostela and Hospital La Paz, Madrid), France (Hopital Intercommunal de Créteil, Créteil and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Caen Côte de Nacre, Caen), Italy (Pediatric Hospital Meyer, Florence and Bambino Gesù Hospital, Rome), Germany (University Hospital Würzburg, Children’s Hospital and University Hospital Schleswig Holstein—Campus Lübeck, Lübeck) and England (King's College Hospital, London and St George’s University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London).

From October 1, 2020, to May 31, 2023, we prospectively identified children who were hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed RSV infection. To account for the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the study team also retrospectively identified RSV cases at study hospitals during September 1, 2018, to April 30, 2019. RSV testing was standard of care for children ≤ 2 years who were admitted with respiratory symptoms at all study hospitals throughout the entire study period.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the population-based annual incidence rate of laboratory-confirmed RSV hospitalization in children ≤ 2 years. The numerator represented the number of RSV hospitalizations among all children ≤ 24 months at study hospitals, during four RSV seasons: September 1, 2018, to April 30, 2019 (2018–2019, pre-pandemic season), October 1, 2020, to September 30, 2021 (2020–2021), October 1, 2021, to September 30, 2022 (2021–2022), and October 1, 2022, to May 31, 2023 (2022–2023). The denominator represented the annual total number of children ≤ 24 months living in the catchment area of the study hospitals (September 1, 2018, to August 31, 2019 (2018–2019, pre-pandemic season), October 1, 2020, to September 30, 2021 (2020–2021), October 1, 2021, to September 30, 2022 (2021–2022), and October 1, 2022, to September 30, 2023 (2022–2023)). Numbers were derived from publicly available sources for each calendar year. If there were multiple hospitals located within the same catchment area, numbers were adjusted to account for the market share of each study hospital.

Statistical analysis

In the calculation of annual incidence rates, certain months with low RSV activity, based on publicly available RSV surveillance data of participating countries (May 1, 2019, to August 31, 2019, and June 1, 2023, to September 30, 2023), were considered to have zero occurrences. Incidence rates and exact 95% confidence intervals were estimated using the pois.exact function from the epitools package in R.

Additionally, we describe the distribution of RSV-associated hospitalization by season, patient demographics (age and gender), and clinical characteristics (underlying medical conditions, pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission, and length of stay). For categorical variables, percentages were reported, and chi-square tests were used to compare proportions. Mean (standard deviation, SD) values were reported for length of stay. Pooled SDs were calculated as the square root of the weighted average of squared SDs available for each month per site and for each of the age groups (0–2, 3–5, 6–12 and 13–24 months) and with the corresponding number of hospitalized children minus one as the weight (as individual patient data was not available).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from all study sites prior to the initiation of the research; Ethikkommission der Universität zu Lübeck (no. 20–345) and Ethik-Kommission der Universität Würzburg (no. 1/20_z) in Germany, Comité de Ética de la Investigación de Santiago y Lugo (no. 2020/452) and Comité de Ética de la Investigación Hospital Universitario La Paz (no. 22/2020) in Spain; Comitato Etico Regione Toscana—Pediatrico c/o Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Meyer (no. 247/2020) and Comitato Etico Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù IRCCS (no. 2275/2020) in Italy; London—Brighton & Sussex Research Ethics Committee (no. 21/LO/0578) in England; Comité de protection des personnes Sud Ouest et Outre Mer IV Cabanis Haut – Centre Cabanis Haut (no. 20.10.09.60811/CPP2020-11-094b) in France. Since only anonymized/aggregated data were collected, no informed consent was obtained for this part of the BRICE study.

Results

Distribution of RSV hospitalizations by patient characteristics

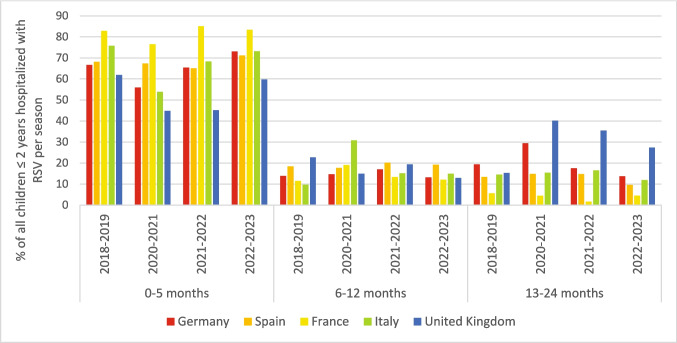

A total of 5,169 RSV hospitalizations were included in the study. Overall, the age distribution of RSV- hospitalizations remained the same across the seasons; over 50% of hospitalizations occurred in infants < 3 months (Table 1). However, there were notable differences within specific countries. In Italy, there was an increase in the proportion of hospitalizations in infants 6–12 months during the 2020–2021 RSV season (31%, 4/13) compared with the pre-pandemic season (10%, 22/227) although numbers during the 2020–2021 season were low. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the proportion of children 13–24 months hospitalized with RSV significantly increased during the 2020–2021, 2021–2022, and 2022–2023 RSV seasons compared with the pre-pandemic season (40% (43/107), 36% (77/217) and 27% (55/201) respectively), compared with 15% (27/176) in the pre-pandemic season (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). However, the increase was less pronounced in the latest season. More than 80% of children hospitalized with RSV had no underlying medical condition. The proportion varied between seasons, but the differences were not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of RSV hospitalizations by patient characteristics and season

| 2018 Sept − 2019 Aug1 | 2020 Oct − 2021 Sept | 2021 Oct − 2022 Sept | 2022 Oct − 2023 Sept2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total number of RSV hospitalizations | 1238 | 610 | 1410 | 1911 | ||||

| Age group (months) | ||||||||

| 0–2 | 635 | 51.3 | 312 | 51.1 | 743 | 52.7 | 1063 | 55.6 |

| 3–5 | 252 | 20.4 | 98 | 16.1 | 230 | 16.3 | 358 | 18.7 |

| 6–12 | 190 | 15.3 | 110 | 18.0 | 226 | 16.0 | 276 | 14.4 |

| 13–24 | 161 | 13 | 90 | 14.8 | 211 | 15.0 | 214 | 11.2 |

| PICU admission | 248 | 20.0 | 180 | 29.5 | 279 | 19.8 | 427 | 22.3 |

| Age 0–2 | 175 | 27.6 | 134 | 43.0 | 181 | 24.4 | 296 | 27.9 |

| Age 3–5 | 34 | 13.5 | 21 | 21.4 | 41 | 17.8 | 68 | 18.9 |

| Age 6–12 | 26 | 13.7 | 14 | 12.7 | 25 | 11.1 | 33 | 11.9 |

| Age 13–24 | 13 | 8.1 | 11 | 12.2 | 32 | 15.2 | 30 | 14.0 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 550 | 45.73 | 278 | 45.6 | 609 | 45.83 | 769 | 43.53 |

| Underlying medical conditions4 | ||||||||

| No underlying medical Conditions | 781 | 80.8 | 396 | 83.7 | 979 | 82.0 | 1133 | 80.9 |

| Chronic lung disease | 19 | 2.0 | 8 | 1.7 | 29 | 2.4 | 38 | 2.7 |

| Congenital heart disease | 42 | 4.3 | 17 | 3.6 | 40 | 3.4 | 63 | 4.5 |

| Prematurity (GA < 36 weeks) | 90 | 9.3 | 34 | 7.2 | 96 | 8.0 | 101 | 7.2 |

| Immunodeficiency (e.g., Cancer, transplant, chemotherapy) | 11 | 1.1 | 3 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.5 |

| Down syndrome | 7 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.6 | 13 | 0.9 |

| Others (e.g., congenital abnormalities of airway, neuromuscular disease, neurologic problems, cystic fibrosis) | 64 | 6.6 | 38 | 8.0 | 99 | 8.3 | 86 | 6.1 |

| Unknown medical conditions5 | 272 | 22 | 137 | 22.5 | 216 | 15.3 | 511 | 26.7 |

| LOS, days (mean, SD)6 | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Total | 5.7 | 4.2 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 6.0 |

| Age 0–2 | 6.3 | 4.1 | 6.3 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 3.9 | 6.0 | 6.3 |

| Age 3–5 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 5.8 | 6.1 |

| Age 6–12 | 4.9 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 2.6 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 3.6 |

| Age 13–24 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 6.7 |

1The data were collected between October 1, 2018, and April 30, 2019, assuming that no cases occurred outside this period

2The data were collected between 1 Sept 2022 and 31 May 2023, assuming that no cases occurred outside this period

3The proportion was calculated among those for whom gender information was available. It was 1204, 1329, and 1815 for the 2018–2019, 2020–2021, and 2022–2023 seasons, respectively

4The proportion was calculated among those for whom the presence of underlying medical conditions is known

5One site (3302) was not able to collect information on underlying medical conditions

6LOS of entire hospital stay (including HDU and/or PICU). Pooled standard deviations were calculated as the square root of the weighted average of squared standard deviations available for each month per site and for each of the age group (0–2, 3–5, 6–12 and 13–24 months) and with the corresponding number of hospitalized children minus one as the weight (as individual patient data was not available). The resulting pooled SDs do not account for any systematic variation between year, site and age groups in the mean LOS and may therefore underestimate the true standard deviations

Sept September, Aug August, Oct October, RSV Respiratory Syncytial Virus, PICU Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, LOS length of stay, GA Gestational Age, SD standard deviation

Fig. 1.

Country-specific age distribution of RSV hospitalizations by season

The proportion of children admitted to the PICU was significantly higher in 2020–2021 with 29.5% (180/610), compared with the other seasons, with 20.0% (248/1238) in 2018–2019, 19.8% (279/1410) in 2021–2022, and 22.3% (427/1911) in 2022–2023 (p < 0.05, Table 1). This increase was primarily driven by a higher proportion of infants 0–2 months being admitted to the PICU during 2020–2021 (43.2%, 134/312, Table 1).

The proportion of PICU admissions varied considerably between countries. Spain had a significantly higher percentage of PICU admissions during 2020–2021 (35.5%, 50/141) compared with the pre-pandemic season (21.2%, 87/402 p < 0.05, Supplementary Table 2) despite fewer hospital and PICU admissions in that season. In the 2022–2023 season, the proportion decreased to pre-pandemic level. In the United Kingdom, the proportion of PICU admissions was lower in the 2021–2022 season (25.3%, 55/217) compared with the pre-pandemic season (36.4%, 64/176, p < 0.05).

Overall, the length of stay was similar across seasons. The mean (SD) number of days ranged from 5.5 (3.7) in 2020–2021 to 5.8 (6.0) in 2022–2023 (Table 1), which was comparable with the pre-pandemic season (mean number of days: 5.7 (4.2)).

Annual incidence rates of RSV hospitalizations

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall population-based annual incidence rate across the five countries in children 0–24 months was 11.3/1000 child-years (95%CI 10.6–11.9) (Table 1). During the 2020–2021 season, the annual incidence rate declined to 5.9/1000 child-years (95%CI 5.4–6.3) but rebounded in the 2021–2022 season to 13.8/1000 child-years (95%CI 13.0–14.5). In the 2022–2023 season, the annual incidence rate was even higher at 18.8/1000 child-years (95%CI 18.0–19.7). This pattern was observed across all age groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Annual incidence rates of RSV hospitalizations across countries, by season and age group

| Number of RSV hospitalizations (numerator) | Number of children in catchment area (denominator)1 | Incidence rate per 1000 child-years (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 Sept – 2019 Aug | |||

| Age (months) | |||

| 0–5 | 887 | 25,487 | 34.8 (32.6–37.2) |

| 6–12 | 190 | 29,925 | 6.4 (5.5–7.3) |

| 13–24 | 161 | 54,591 | 3.0 (2.5–3.4) |

| 0–12 | 1077 | 55,412 | 19.4 (18.3–20.6) |

| 0–24 | 1238 | 110,003 | 11.3 (10.6–11.9) |

| 2020 Oct – 2021 Sept | |||

| Age (months) | |||

| 0–5 | 410 | 24,493 | 16.7 (15.2–18.4) |

| 6–12 | 110 | 28,576 | 3.9 (3.2–4.6) |

| 13–24 | 90 | 51,294 | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) |

| 0–12 | 520 | 53,069 | 9.8 (9.0–10.7) |

| 0–24 | 610 | 104,363 | 5.9 (5.4–6.3) |

| 2021 Oct – 2022 Sept* | |||

| Age (months) | |||

| 0–5 | 973 | 24,056 | 40.4 (38.0–43.1) |

| 6–12 | 226 | 28,033 | 8.1 (7.1–9.2) |

| 13–24 | 211 | 50,439 | 4.2 (3.6–4.8) |

| 0–12 | 1199 | 52,089 | 23.0 (21.7–24.3) |

| 0–24 | 1410 | 102,528 | 13.8 (13.0–14.5) |

| 2022 Oct – 2023 Sept* | |||

| Age (months) | |||

| 0–5 | 1421 | 23,889 | 59.5 (56.4–62.7) |

| 6–12 | 276 | 27,836 | 9.9 (8.8–11.2) |

| 13–24 | 214 | 49,905 | 4.3 (3.7–4.9) |

| 0–12 | 1697 | 51,725 | 32.8 (31.3–34.4) |

| 0–24 | 1911 | 101,630 | 18.8 (18.0–19.7) |

1The number of children in the catchment area was adjusted for the market share of the participating hospital if there were other hospitals in the same catchment area

*Denominator numbers for various sites in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy were used from 2021 (sites 3401, 4401, and 4902) and 2022 (sites 3301, 3302, 3402, 3902, 4402, and 4901) due to unavailability of numbers for 2022 and/or 2023

RSV Respiratory Syncytial Virus, CI Confidence Interval, Sept September, Aug August, Oct October

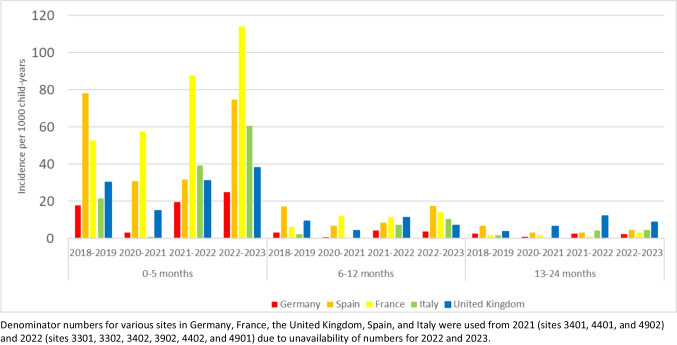

Across all countries and seasons, the incidence rate was highest in the 0–6 months age group. In most seasons, France had the highest incidence rates in this age group (range 52.7 [95%Cl 46.0–60.1]—114.1 [95%CI 103.9–125.0] per 1000 child-years) and Germany the lowest (range 3.1 [95%Cl 1.9–4.8]—24.8 [95%CI 21.0–29.1] per 1000 child-years) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). In all countries except Spain, the incidence rate in infants 0–6 months in the 2022–2023 season was higher than in the pre-pandemic season.

Fig. 2.

Country-specific annual incidence rates of RSV hospitalizations by season and age group

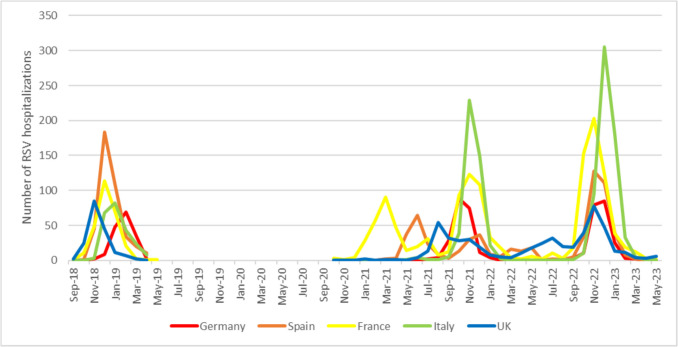

Distinct patterns of RSV resurgence across five European countries

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the RSV season experienced significant disruptions in all five countries included in the study. However, as later seasons unfolded, the re-emergence of RSV activity varied across the five countries (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Monthly distribution of RSV hospitalizations of children ≤ 2 years between September 2018 and April 2019 (pre-pandemic season) and October 2020 and May 2023

In France, RSV hospitalizations first peaked in March 2021, three months later than the peak in the pre-pandemic season (December 2018). The hospitalization rate was low through the summer of 2021, followed by an increase in cases during the fall and a second peak in November 2021. France was the only country to report a significant number of hospitalizations (n = 230) during the typical RSV season (from October to April) in 2020–2021. In comparison, the other four countries reported 0–5 RSV hospitalizations during the same period. In November 2022, RSV hospitalization rates peaked again, followed by a rapid decline starting from January 2023 onwards. This decline occurred earlier compared with the pre-pandemic season.

During the typical 2020–2021 season, Spain and England reported a negligible number of hospitalizations (five and four hospitalizations, respectively). In both countries, there was an increase in RSV hospitalizations between seasons, with peaks occurring in June and August 2021, respectively. In Spain, cases were almost absent during the summer of 2022, but started to rise from October onwards, peaking sharply in November–December 2022, followed by a steep decline and minimal cases from March 2023 onwards. In England, there was continuous circulation of RSV throughout 2022, peaking in November 2022 and then declining from January 2023 onwards. Both countries experienced a final season that was comparable with the pre-pandemic season.

Germany did not report any RSV hospitalization cases during the typical RSV season in 2020–2021, while Italy reported one case. In both countries, RSV hospitalizations started to rise in the fall of 2021, which was four and two months earlier than the pre-pandemic season in those countries, respectively. The number of RSV hospitalizations peaked in October–November 2021, followed by a sharp decline and virtually no cases after February 2022. In Italy, RSV cases increased sharply during December and January of the 2022–2023 season. In Germany, hospitalizations peaked in December 2022, which was again earlier compared with the pre-pandemic season.

Discussion

This study is one of the few studies to compare RSV hospitalization incidence in different European countries during recent RSV seasons, including periods prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The annual incidence rate in children 0–24 months was lowest during the 2020–2021 pandemic season (5.9/1000 child-years) but rebounded in the following seasons to rates higher than pre-pandemic levels. The highest rate of 18.8/1000 child-years was observed in the 2022–2023 season.

There were remarkable differences in circulation between countries during the pandemic. Countries that experienced an early or interseason resurgence of RSV in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, had a prolonged period of RSV circulation, leading to persistent hospitalizations throughout the year, albeit at a low rate. In contrast, countries with a more delayed resurgence closer to the subsequent season followed a more typical seasonal pattern, with a sharp decline in RSV cases after reaching a peak. During the 2022–2023 season, all countries returned to a more or less normal RSV season. However, the overall annual incidence rate was higher compared with the pre-pandemic season, and the peak remained earlier than normal in France, Italy, and Germany. Higher PICU admission rates in young infants, and in some countries a higher proportion of older children being hospitalized due to RSV, was largely limited to 2020–2021.

The persistent higher annual RSV hospitalization rates during the 2021–2022 and 2022–2023 seasons compared to the pre-pandemic season, has also been reported in Denmark, Canada and USA [19–21]. This increased hospitalization rate may suggest a prolonged period of "immunity debt" following the COVID-19 pandemic, which suggests that a larger proportion of the population may have reduced levels of immunity to RSV due to limited exposure, possibly including pregnant women. However, the varying patterns observed may be influenced by country-specific factors, particularly the COVID-19 restrictions and relaxations implemented. Factors such as school reopening and the reopening of international borders can also impact the transmission dynamics of RSV [16, 18, 22]. Furthermore, our study indicated that the pattern of the RSV resurgence had an impact on the relative incidence during different months of the season. This finding is consistent with previous studies conducted in the Netherlands [23] and United States [24].

We observed a shift in hospitalizations towards older ages in the 2020–2021 season in the United Kingdom and Italy only. Inconsistency in the age distribution of RSV hospitalizations has also been observed within and across countries. For example, a recent nationwide study conducted in Canada found no change in the age distribution of hospitalized RSV cases [25], while a single center study in British Columbia reported an increase in age during the 2020–2021 season [20], indicating regional differences. A nationwide study in Denmark found the highest increase in the risk of hospital admission in children 24–60 months [26], not included in the study presented here. This observation could also potentially be attributed to the concept of "immunity debt"in older children.

Most studies have found no significant difference in the severity of RSV disease during the COVID-19 pandemic [16, 19–21, 25–27]. However, in the current study, a higher percentage (29.5%) of hospitalized children were admitted to the PICU during the 2020–2021 period compared to the pre-pandemic period (20%), particularly in the youngest age group (0–2 months), although the absolute numbers of overall hospital and PICU admissions were considerably lower compared with other seasons (50% fewer overall hospital admissions and 25% fewer PICU admissions compared to the pre-pandemic season). One possible explanation could be a modified threshold for admitting children to the PICU during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Spain, France, and England, the percentage in PICU admissions exceeded 20% during all seasons, which is higher compared with other literature focused on the pre-pandemic era [28–30]. One plausible explanation for this difference is that our study specifically targeted hospitals with a PICU, which may have resulted in an overrepresentation of PICU admissions as children from hospitals without a PICU would be referred to these selected hospitals. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that most other studies of RSV hospitalizations have been conducted in tertiary hospitals. Additionally, our study found that the average length of hospital stay was consistent at around 5–6 days across countries and seasons, similar to other studies conducted in Germany and Italy [29, 30]. However, it is essential to note that our aggregated dataset only allowed for the calculation of the mean, not the median, which could have been lower.

In our study, more than 80% of children hospitalized with RSV did not have any underlying medical condition. We did not observe an increase in the proportion of premature children or children with underlying medical conditions hospitalized due to RSV during the COVID-19 pandemic, consistent with previous reports [20, 21, 26]. This is likely attributed to the continued use of immunoprophylaxis in these vulnerable populations.

The BRICE study has several strengths and limitations. One strength is the inclusion of sites that routinely test children ≤ 2 years hospitalized for acute respiratory tract infections. This allowed for the inclusion of a control season prior to the pandemic and minimized the risk of underestimating RSV hospitalizations. Importantly, the identification of cases were standardized during the prospective seasons, enabling comparisons among countries. However, thresholds for admitting children to hospitals and to the PICU can vary by country, as reflected in the differing incidence and prevalence estimates between countries. A more granular severity index, along with an understanding of incidence rates of outpatient RSV—which was not collected in our study—could have provided a better insight into hospitalized cases in each country. In addition, testing practices and propensity were dynamic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Routine nasal swab testing has become more common during the pandemic period, and it may have subsequently increased the testing rate for RSV. Also, a few hospitals used rapid antigen detection (RAD) in conjunction with PCR. Since the sensitivity of RAD is known to be lower than that of PCR [31], our incidence rate might have been slightly underestimated. Additionally, during the retrospective season, not every child may have been tested, potentially leading to an underestimation of the true incidence. A previous study with routine testing estimated that the rate of missed testing could be up to 15% [2]. We compared RSV incidence during the study period with only one prepandemic season (2018–2019). This may have resulted in an under- or overestimation of prepandemic incidence, as it is known that RSV circulation varied between seasons before the pandemic. However, this variation is considered minimal compared to the changes in RSV seasonality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, there were variations across sites in determining the denominator for calculating incidence rates, mainly due to limited data availability regarding the exact market share of hospitals. However, the pre-pandemic annual incidence in this study aligns with other literature [2, 32–35]. While children from outside the catchment area, such as those on vacation, could have been included in the numerator, the impact on the incidence rate is likely minimal. Third, the study did not specifically examine co-infections with other viruses. Differences in co-infection rates during the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially impact the severity of RSV disease and hospitalization rates. However, previous studies have not consistently demonstrated a clear association between co-infection and more severe RSV disease [36–39]. Fourth, underlying medical conditions were unknown in 15–27% of hospitalized children. This primarily stemmed from missing data at one site, whereas the data from the other sites was almost complete. Finally, despite the geographic span of participating sites, incidence rates may not fully represent the entire country.

Conclusion

The population-based incidence of RSV hospitalization in children ≤ 2 years is substantial. Considerable variation in incidence was observed between 2020 and 2023, with an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic followed by a rebound in the subsequent seasons. Our study underscores the importance of RSV surveillance and flexibility in RSV preventive strategies.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jorge Atucha (Hospital Universitario La Paz), Mélanie Vassal (Centre hospitalier intercommunal de Créteil), Cécile Valentin and Virginie Boscher (Clinical Research Center, CAEN University Hospital), Daniela Lupia, Priscilla Molinaro and Beatrice Tani (Hospital University Pediatrics Clinical Area, Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital IRCCS), Antonella Mollo and Federica Attaianese (Pediatric Unit Meyer Children's Hospital, IRCCS), Ana Isabel Dacosta Urbieta and Carmen Rodríguez-Tenreiro Sánchez (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela), Katrin Hartmann, Fabian Rothbauer, Valerie Schwägerl, Denise Yilmaz (Department of Pediatrics, University Hospital Würzburg), Christine Wolff, Maureen Weckmann (Department of Paediatrics, University Hospital Schleswig Holstein—Campus Lübeck), Konstantinos Karampatsas, Rebecca Mangion, Kirsty Portazier and Sana Ibrahim (St George's University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London) for their assistance in data collection at local study sites. FM-T research work was also supported by Framework Partnership Agreement between the Consellería de Sanidad de la Xunta de Galicia and GENVIP-IDIS-2021–2024 (SERGAS-IDIS March 2021; Spain); ReSVinext: PI16/01569, Enterogen: PI19/01090, OMI-COVI-VAC: PI22/00406 co-funded with FEDER funds; GEN-COVID (IN845D 2020/23), Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CB21/06/00103).

BRICE Study Group

Celine Delestrain and Mickael Shum (Centre hospitalier intercommunal de Créteil), Caroline Faucon (Department of Medical Pediatrics, CAEN University Hospital), Nicola Ullmann (Respiratory and Cystic Fibrosis Unit, Academic Pediatric Department, Bambino Gesù Children Hospital, IRCCS, Rome, Italy), Anna Chiara Vittucci (Hospital University Pediatrics Clinical Area, Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital IRCCS, Rome, Italy), Clara Haug and Niklas Jaboks (University Hospital Schleswig Holstein - Campus Lübeck, Lübeck), Silvia Ricci (Immunology Unit Meyer Children's Hospital, IRCCS), Chiara Rubino (Pediatric Unit Meyer Children's Hospital, IRCCS), Geraldine Engels, Katharina Hecker, Andrea Streng, Julia Bley (Department of Pediatrics, University Hospital Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany), Natasha Thorn (St George's University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London).

Authors' Contributions

JL, EH, RE, CF, CC, FMT, CA, RC, AG and SD collected data.

JGW, DC and YC analysed and interpreted data. JGW wrote the

first draft. JGW and DC accessed and verified the data.

All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored and funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, who was involved in protocol development and writing the manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interest

Yoonyoung Choi and Madelyn Ruggieri are employees at Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. FM-T has acted as principal investigator in randomized controlled trials of Ablynx, Abbot, Seqirus, Sanofi Pasteur, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, Regeneron, Jansen, Medimmune, Novavax, Novartis and GSK, with honoraria paid to his institution. FM-T reports a relationship with GSK Vaccines SRL that includes consulting or advisory. FM-T reports a relationship with Pfizer Inc that includes consulting or advisory. FM-T reports a relationship with Sanofi Pasteur Inc that includes consulting or advisory. FM-T reports a relationship with Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc that includes consulting or advisory. FM-T reports a relationship with MSD that includes consulting or advisory. FM-T reports a relationship with Seqirus Pty Ltd that includes consulting or advisory. SBD has previously received honoraria from Sanofi for taking part in RSV advisory boards and has provided consultancy and/or investigator roles in relation to product development for Janssen, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Moderna, Valneva, MSD, iLiAD and Sanofi with fees paid to my institution. SBD is a member of the UK Department of Health and Social Care’s (DHSC) Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) RSV subcommittee and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency’s (MHRA) Paediatric Medicine Expert Advisory Group (PMEAG), but the reviews expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of DHSC, JCVI, MHRA or PMEAG. JGW has been an investigator for clinical trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies including AstraZeneca, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Janssen and has been an investigator for clinical trials funded by IMI/Horizon2020 and ZonMw. All funds have been paid to UMCU. JGW participated in advisory boards of Janssen and Sanofi and was a speaker at Sanofi and MSD sponsored symposia with honoraria paid to UMCU. LB has regular interaction with pharmaceutical and other industrial partners. He has not received personal fees or other personal benefits. UMCU has received major funding (> €100,000 per industrial partner) for investigator initiated studies from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Janssen, Pfizer, MSD and MeMed Diagnostics. UMCU has received major funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. UMCU has received major funding as part of the public private partnership IMI-funded RESCEU and PROMISE projects with partners GSK, Novavax, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Sanofi. UMCU has received major funding by Julius Clinical for participating in clinical studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Merck and Pfizer. UMCU received minor funding (€1000–25,000 per industrial partner) for consultation, DSMB membership or invited lectures by Ablynx, Bavaria Nordic, GSK, Novavax, Pfizer, Moderna, Astrazeneca, MSD, Sanofi, Janssen. LB is the founding chairman of the ReSViNET Foundation. EH has received speaking fees and travel support from Pfizer, MSD, Sanofi, Abbvie/AstraZeneca and Chiesi. RE has previously received honoraria for lectures, expertise or educational events. RE has previously received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Sanofi for taking part in RSV advisory boards and also from AstraZeneca, GSK Pfizer, and Sanofi for lectures, expertise or educational events. JL has been an investigator for clinical trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies including AstraZeneca, GSK, MSD, Pfizer and Sanofi and received consulting or lecture fees from Enanta, Engelhard Pharma, Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi and Siemens Health Care. CA has received fees for meetings or consulting or advisory boards from Astra Zeneca, GSK, MSD, Moderna, Novavax, Pfizer, Sanofi.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Joanne G. Wildenbeest, Email: j.g.wildenbeest@umcutrecht.nl

BRICE Study Group:

Celine Delestrain, Mickael Shum, Caroline Faucon, Nicola Ullmann, Anna Chiara Vittucci, Clara Haug, Niklas Jaboks, Silvia Ricci, Chiara Rubino, Geraldine Engels, Katharina Hecker, Andrea Streng, Julia Bley, and Natasha Thorn

References

- 1.Li Y et al (2022) Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399(10340):2047–2064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wildenbeest JG et al (2023) The burden of respiratory syncytial virus in healthy term-born infants in Europe: a prospective birth cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 11(4):341–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall CB et al (2009) The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med 360(6):588–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell I et al (2022) Respiratory Syncytial Virus Immunoprophylaxis with Palivizumab: 12-Year Observational Study of Usage and Outcomes in Canada. Am J Perinatol 39(15):1668–1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Medicines Agency. News. New medicine to protect babies and infants from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. Sept 16, 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/new-medicine-protect-babies-infants-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-infection (Accessed Sept 9, 2023)

- 6.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA news release. FDA Approves New Drug to Prevent RSV in Babies and Toddlers. July 17, 2023.https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-prevent-rsv-babies-and-toddlers (Accessed Sept 9, 2023)

- 7.Mazur NI et al (2023) Respiratory syncytial virus prevention within reach: the vaccine and monoclonal antibody landscape. Lancet Infect Dis 23(1):e2–e21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeves RM et al (2017) Estimating the burden of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) on respiratory hospital admissions in children less than five years of age in England, 2007–2012. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 11(2):122–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jepsen MT et al (2018) Incidence and seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalisations in young children in Denmark, 2010 to 2015. Euro Surveill 23(3). 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.3.17-00163

- 10.Oskarsson Y et al (2022) Clinical and Socioeconomic Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Iceland. Pediatr Infect Dis J 41(10):800–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gil-Prieto R et al (2015) Respiratory Syncytial Virus Bronchiolitis in Children up to 5 Years of Age in Spain: Epidemiology and Comorbidities: An Observational Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 94(21):e831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramer R et al (2018) Cost and burden of RSV related hospitalisation from 2012 to 2017 in the first year of life in Lyon. France Vaccine 36(45):6591–6593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demont C et al (2021) Economic and disease burden of RSV-associated hospitalizations in young children in France, from 2010 through 2018. BMC Infect Dis 21(1):730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinon-Torres F et al (2023) Clinical and economic hospital burden of acute respiratory infection (BARI) due to respiratory syncytial virus in Spanish children, 2015–2018. BMC Infect Dis 23(1):38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeoh DK et al (2021) Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Public Health Measures on Detections of Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Children During the 2020 Australian Winter. Clin Infect Dis 72(12):2199–2202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatter L et al (2021) Respiratory syncytial virus: paying the immunity debt with interest. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 5(12):e44–e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Summeren J et al (2021) Low levels of respiratory syncytial virus activity in Europe during the 2020/21 season: what can we expect in the coming summer and autumn/winter? Euro Surveil 26(29):2100639

- 18.Billard MN et al (2022) International changes in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) epidemiology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Association with school closures. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 16(5):926–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nygaard U et al (2023) The magnitude and severity of paediatric RSV infections in 2022–2023: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Paediatr 112(10):2199–2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vineta Paramo M et al (2023) Respiratory syncytial virus epidemiology and clinical severity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in British Columbia, Canada: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Reg Health Am 25:100582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMorrow ML et al (2024) Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Hospitalizations in Children <5 Years: 2016–2022. Pediatrics. 10.1542/peds.2023-065623

- 22.Eden JS et al (2022) Off-season RSV epidemics in Australia after easing of COVID-19 restrictions. Nat Commun 13(1):2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowensteyn YN et al (2023) Year-round RSV transmission in the Netherlands following the COVID-19 pandemic - A prospective nationwide observational and modeling study. J Infect Dis. 10.1093/infdis/jiad282

- 24.Daniels D et al (2023) Epidemiology of RSV bronchiolitis among young children in central new york before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 10.1097/INF.0000000000004101

- 25.Bourdeau M et al (2023) Pediatric RSV-Associated Hospitalizations Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 6(10):e2336863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nygaard U et al (2023) Hospital admissions and need for mechanical ventilation in children with respiratory syncytial virus before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 7(3):171–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiefer A et al (2023) Comparative analysis of RSV-related hospitalisations in children and adults over a 7 year-period before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Virol 166:105530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bont L et al (2016) Defining the Epidemiology and Burden of Severe Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection Among Infants and Children in Western Countries. Infect Dis Ther 5(3):271–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartmann K et al (2022) Clinical Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Hospitalized Children Aged </=5 Years (INSPIRE Study). J Infect Dis 226(3):386–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bozzola E et al (2020) Respiratory Syncytial Virus Bronchiolitis in Infancy: The Acute Hospitalization Cost. Front Pediatr 8:594898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onwuchekwa C et al (2023) Pediatric Respiratory Syncytial Virus Diagnostic Testing Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Infect Dis 228(11):1516–1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johannesen CK et al (2022) Age-Specific Estimates of Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Hospitalizations in 6 European Countries: A Time Series Analysis. J Infect Dis 226(Suppl 1):S29–S37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wick M et al (2023) Inpatient burden of respiratory syncytial virus in children </=2 years of age in Germany: A retrospective analysis of nationwide hospitalization data, 2019–2022. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 17(11):e13211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gea-Izquierdo E et al (2023) Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalization in children aged <2 years in Spain from 2018 to 2021. Hum Vaccin Immunother 19(2):2231818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Del Riccio M et al (2023) Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in the European Union: estimation of RSV-associated hospitalizations in children under 5 years. J Infect Dis 228(11):1528–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asner SA et al (2015) Is virus coinfection a predictor of severity in children with viral respiratory infections? Clin Microbiol Infect 21(3):264 e1–6

- 37.Emanuels A et al (2020) Respiratory viral coinfection in a birth cohort of infants in rural Nepal. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 14(6):739–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y et al (2020) The role of viral co-infections in the severity of acute respiratory infections among children infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 10(1):010426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazur NI et al (2017) Severity of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Lower Respiratory Tract Infection With Viral Coinfection in HIV-Uninfected Children. Clin Infect Dis 64(4):443–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.