Abstract

Aims

Varenicline was compared with transdermal nicotine (NRT) for smokers with current substance use disorders (SUD) for effects on 3-month smoking abstinence (primary outcome) and, secondarily, on 3- and 6 month abstinence while adjusting for medication adherence, and on additional smoking and substance use outcomes. Moderation by major depressive disorder history (MDD) and adherence were investigated.

Design

Double-blind double-placebo-controlled randomized design, stratifying by MDD, gender and nicotine dependence, with 3 and 6 months follow-up.

Setting

University offices in Rhode Island, USA.

Participants

Adult smokers (n = 137), in SUD treatment, substance abstinent <12 months (n = 77 varenicline, 60 NRT).

Intervention and comparator

Twelve weeks of varenicline (2 mg/day, after 1-week dose run-up) or NRT (21 mg/day decreasing to 7 mg/day).

Measurements

Primary: point-prevalence smoking abstinence (7-day, confirmed) at 3 months. Secondary: point-prevalence abstinence at 6 months, quantity and frequency of smoking and substance use at 3 and 6 months, and within-treatment abstinence, medication adherence and depressive symptoms. Smoking outcome analyses were repeated controlling for adherence and investigating adherence as a moderator.

Findings

Effects on 3-month abstinence were P < 0.065 without a covariate (Bayes factor 3.35, supporting the effect strongly) and differed significantly when controlling for baseline smoking [varenicline: 13%, NRT: 3%; odds ratio (OR) = 4.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00, 23.13, P < 0.05]. The threefold difference at 6 months was not significant. Medication effect on abstinence across time was significant (P < 0.05) covarying adherence and baseline smoking (OR = 6.40, 95% CI = 1.00, 40.93). Medication differences in 3-month abstinence occurred among participants with ≥ 77% adherence (P < 0.02). No significant medication effects on heavy drinking, drug use or depressive symptoms were found.

Conclusions

Varenicline appears to improve the chances of achieving at least 3 months of smoking abstinence in smokers with substance use disorders trying to stop, compared with transdermal nicotine patches, the effect being independent of history of depressive disorder.

Keywords: Brief advice, depression, nicotine dependence, point-prevalence abstinence, smoking cessation, substance use disorders, varenicline

INTRODUCTION

Smokers with substance use disorders (SUD) are more likely to die from smoking than from alcohol use [1–3] and have limited success quitting smoking early in sobriety [4]. SUD treatment provides an opportunity to intervene with smoking, but pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation have rarely been investigated among people with non-alcohol SUDs and rarely early in recovery. Transdermal nicotine replacement (NRT) with counseling results in only 3.5% abstinence at 12 months on average with recently or long-term sober smokers with alcohol use disorders [5,6]. Smokers with current alcohol use disorders did not benefit from transdermal NRT [7,8].

Low motivation to quit smoking in this population [9–11] correlates significantly with perceiving more barriers to quitting smoking [9]. Expecting to be unable to tolerate the discomforts of tobacco abstinence predicts less tobacco abstinence 3 months later [12], so reducing withdrawal distress may be essential. Another barrier is concern that smoking cessation will make it harder to stay sober [13]. As continued smoking undermines long-term sobriety [14,15], these smokers need corrective information.

Varenicline is more effective for smoking than other medications except combination nicotine replacement in the general population [16,17], even among those who do not complete it [18], and in smokers with low motivation to quit [19]. Varenicline reduces tobacco withdrawal [20,21], smoking pleasure and craving (e.g. [22,23]). Furthermore, in heavy drinkers and in one study with people with alcohol use disorders (e.g. [24,25]), varenicline reduced drinks per day and alcohol craving.

Varenicline increased smoking abstinence compared to placebo in methadone patients [26], but not compared to NRT [27]. However, varenicline has not been tested with smokers with a range of SUDs, nor combined with counseling designed to increase motivation to quit and address perceived barriers [28], and most studies [16] excluded major depressive disorder (MDD). Given frequent MDD in patients in SUD treatment [29], we stratified on MDD history and investigated it as a moderator of outcome.

We hypothesized that 12 weeks of varenicline versus NRT would be more effective in producing (Aim 1) 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 3 months (primary outcome) and 6 months (secondary outcome) and (Aim 2) across 3 and 6 months when controlling for baseline smoking and degree of medication adherence (a secondary outcome) for smokers in SUD treatment receiving brief advice [30,31] to motivate smoking cessation. We considered 3 months as primary for determining the extent of a treatment effect by the end of treatment, while maintenance of treatment effects over time we considered as secondary as only relevant if initial treatment effects occur.1 We also examined effects on (Aim 3) quantity and frequency of smoking, (Aim 4) on within-treatment smoking abstinence and depressive symptoms and (Aim 5) on substance use. Finally, we examined (Aim 6) potential moderators (MDD, medication adherence, nicotine dependence and gender) of medication effects on outcome.

METHODS

Participants

Smokers were recruited via advertisements in Providence, RI, from 2009 to 2014. Inclusionary criteria were: (a) SUD diagnosis; (b) enrollment in any out-patient SUD treatment; (c) 10+ cigarettes per day for the past 6 months; and (d) aged 18–75 years. Exclusionary criteria were: (a) evidence of hallucinations or delusions, (b) current smoking cessation treatment, (c) contraindications for either medication (such as pregnancy, uncontrolled hypertension or severe renal impairment), (d) using medications affected by smoking cessation (antipsychotics, warfarin, theophylline and insulin), (e) suicidal plan or attempts in past 5 years, (f) not willing to try to quit smoking and (g) substance use reported on the day of or before recruitment or positive breath alcohol at recruitment (this could impair accurate answers and ability to consent; they could reschedule once to avoid this rule).Participants did not need to be motivated for smoking cessation treatment; this is a study of cessation induction regardless of motivation.

Recruitment

Brief screening and informed consent by research interviewers was followed by physical examination, laboratory tests and screening interviews. Participants designated someone as a locator and informant.

Overview of design, randomization and procedures

Using a double-blind double-placebo design, participants were randomized to 12 weeks of varenicline plus placebo NRT after a 1-week dose run-up, or 12 weeks of transdermal NRT plus placebo capsules after a 1-week placebo capsule lead-in. All were asked to quit smoking at the end of the 7-day capsule lead-in period and attend 10 brief advice sessions. Within-treatment assessments were conducted 2, 5 and 9 weeks after randomization, and follow-up assessments at 3 months and 6 months after randomization. All procedures were conducted at university offices downtown and approved by the university Institutional Review Board. The trial was registered with Clinical trials.gov, with identifier NCT00756275.

Urn randomization [32] to medication condition (1 : 1 assignment) was stratified by gender, median score on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence [33] from a previous study [28] and history of MDD. The randomization program was run by the Project Manager, who concealed the assignment from all other staff. Conditions did not have exactly the same n by chance due to randomization. Participants receiving capsules on randomization day were included in intent-to-treat analyses.

Intervention conditions

Varenicline and placebo capsules

Varenicline and matching placebo capsules were prepared by a compounding pharmacy. Participants received 0.5 mg/day for 3 mornings and 1 mg/day (0.5 mg 2×/day) for the next 4 days (dose run-up), and 2 mg/day (1.0 mg 2×/day) thereafter. Placebo capsules were on the same schedule. Written instructions and a physician contact card were provided.

NRT and placebo patch

NRT followed clinical practice guidelines [30], modified for 12 weeks [34]: 4 weeks each of 21 mg/day, 14 mg/day and 7 mg/day. Placebo patches (Rejuvenation Labs, Inc., Midvale, UT, USA) matched active ones. All were instructed to start using patches on quit day after the 7-day capsule dose run-up.

Counseling for both medication conditions

Fully manualized brief advice [31,35] included a 20-minute session at the start of the dose run-up week, a 30-minute session on quit day a week later, then eight weekly 5–10-minute sessions. Assistance involved advice about cognitive–behavioral methods [35], a self-help handbook [36] and problem-solving around barriers [13] and medication issues. Concerns about effects on sobriety were countered with corrective information [28]. The two research therapists (masters’ level, bachelors’ level) had 10 hours of training. Session audiotapes were reviewed in weekly supervision with a doctoral level clinical psychologist, and rated for competence and adherence with immediate feedback.

Assessments

Assessment procedures

Research interviewers blind to condition conducted assessments at baseline, quit day and 2 weeks, 5 weeks, 9 weeks, 3 months and 6 months after the start of dose run-up. At 3 and 6 months, participants were first tested (Alco Sensor IV by Intoximeters, Totnes, UK) to insure a breath alcohol ≤ 0.02 g/dl [37]. Participants who withdrew from treatment were followed for assessments. Participants received $185 for completing all assessments.

Individual difference measures

Diagnoses were made using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV–patient version [38]. A 6-month time-line follow-back (TLFB) interview [39–41] at baseline was scored for number of days of drug use, number of heavy drinking days (at least six/five drinks/day for men/women [42]), and number of cigarettes per day. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence was given. Breath carbon monoxide (CO) was collected using an EC50 Micro III Smokerlyzer® (Bedfont Scientific Ltd, Kent, UK). Barriers to Quitting Smoking in Substance Abuse Treatment (BQS-SAT [13]) identified barriers for corrective feedback in counseling.

Medication adherence

NRT use and capsule adherence were assessed through counts of returned used patches and MEMSCaps (TM; Aardex, Sion, Switzerland) data.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome for Aim 1 was self-reported 7-day point-prevalence abstinence confirmed with a CO level ≤ 4 parts per million (p.p.m.) and salivary cotinine level ≤ 15 ng/ml [43–45] (cotinine not used if using NRT at the time) at 3 months (to detect maximum medication effect after all medication was completed). Secondary measures included 7-day confirmed point-prevalence abstinence at 6 months (Aims 1 and 2; to detect maintenance of effects) and 3- and 6-month average number of cigarettes per day (including abstinent days as zero) and percentage of smoking days (including abstinent days as zero) based on TLFB data (Aim 3). Other secondary measures included within-treatment (5 and 9 weeks after start of dosing) point-prevalence smoking abstinence confirmed by CO ≤ 4 p.p.m. (to see time–course of medication effects) (Aim 4), length of longest continuous abstinence from weeks 9–12 in days (including non-abstainers as zero) (Aim 4), and drug and alcohol use at 3 and 6 months (Aim 5; any heavy drinking, any drug use, number of heavy drinking days and number of drug use days). To count as abstinent from drugs, both self-report and urine drug screen (On Trak® test cups [Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for screening confirmed with the enzyme multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT), gas chromatography and mass spectrometry] must have been negative. A significant other was interviewed to encourage honest reporting, but as such reports do not increase validity, they were not used as data [46].

Safety monitoring measures

The Beck Depression Inventory–II [47] (BDI) was administered at baseline and every counseling session to monitor depressive symptoms (Aim 5). At each session a checklist assessed adverse effects.

Statistical analysis approach

Power

In our Data and Safety Monitoring Plan we estimated that detecting a difference of 12 versus 4% abstinent would require n = 274, while detecting a difference of 15 versus 4% would require a total n = 162 with 80% power and alpha of 0.05. When funding concluded we had attained n = 137 randomized, with 62% power to detect the actual primary outcome, 32% power for the actual 6-month abstinence outcome.

Preliminary analyses

All variables were checked for assumptions of normality. Number of heavy drinking days, number of drug use days and percentage of smoking days at follow-up were skewed, so were log-transformed for analyses, with untransformed values presented for ease of interpretation. Medication condition differences in baseline characteristics, medication adherence, number of counseling sessions and follow-up rates were examined with one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and χ2 for dichotomous variables.

Handling missing data

At follow-up, participants with a CO > 4 p.p.m., cotinine >15 ng/ml, missing CO or cotinine data (except if using NRT) or self-reported smoking were coded as having smoked. Interviewees with a positive, missing or contaminated drug screen were coded as having used drugs for that follow-up interval. Positive imputation for smoking research is most likely to reflect the true values [48]. However, analyses of smoking outcomes, drug use days and heavy drinking days were re-run using multiple imputation [48,49] (using MIANALYZE procedures [50]) as sensitivity analyses [51] for those missing verified abstinence, cigarettes per day, percentage of smoking days or number of days that any drugs or heavy drinking occurred at each follow-up [49,52]. As none of these results differed in significance level from analyses without multiple imputation, analyses showing multiple imputation of the smoking outcomes are presented only in a supplement (Supporting information, Appendix S1).

Post-treatment outcome analyses

For Aim 1, the primary and secondary outcomes (3- and 6-month confirmed 7-day point-prevalence abstinence) were each analyzed with two-group logistic regression, with and without covarying baseline number of cigarettes per day, as this covariate controls for variance due to individual differences unrelated to treatment assignment. For abstinence outcomes close to significant without using the covariate, a Bayes factor (http://www.lifesci.sussex.ac.uk/home/Zoltan_Dienes/inference/Bayes.htm) was calculated to determine whether the results were likely to support the hypothesis in comparison to the expected effect size [53]. For Aim 2, as clinicians want to know if a medication works better when patients have greater adherence, we next entered 3- and 6-month confirmed point-prevalence abstinence into a medication × time analysis while covarying percentage of capsules taken and pre-treatment cigarettes per day. Generalized estimating equations (GEE [54]) models included terms for time and medication × time interaction while being insensitive to missingness. For Aim 3, the average number of cigarettes per day and percentage of smoking days were also analyzed with GEE, entering as covariates the baseline value of the same variable and percentage of capsules taken. The Wald statistic was used for significance testing for dichotomous outcomes and effect size d for continuous outcomes.

Within-treatment (Aim 4)

GEE analyses of confirmed 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at weeks 5 and 9 covaried pre-treatment cigarettes smoked per day. The length of longest continuous abstinence from weeks 9 to 13 was analyzed with regression, entering pre-treatment cigarettes per day as a covariate.

Moderator analyses (Aim 6)

Potential moderators of 3-month point-prevalence abstinence were MDD, percentage of medication capsules taken, gender and Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, investigated using medication by moderator path analysis (using PROCESS [55]). The significant interaction with capsule adherence was followed with simple slopes analyses of medication effects on abstinence at three levels of adherence (the moderator): low [≤ 1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean], average (from > −1 SD to < +1 SD) and high (≥ 1 SD above the mean).

Safety and substance use

BDI total score (Aim 4) was analyzed with group × time GEE of data at baseline and weeks 2, 5, 9 and 3 months, with post-hoc Tukey tests within time. Adverse events are handled descriptively due to low incidence. Substance use outcomes during each follow-up period (Aim 5) were analyzed using t-tests or χ2 tests at each time-point and then across time with GEE, without covariates.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics, attrition and confirmation of abstinence

See Fig. 1 for recruitment figures and for data collected for the primary outcome. Follow-up interviews were completed by 89 of 137 (65%) at 3 months and 80 of 137 (58%) at 6 months, but point-prevalence abstinence was analyzed for all 137. Follow-up completion did not differ significantly by medication condition, race, gender, age, education, FTND, MDD or number of drinking days. CO and cotinine collection did not differ significantly by condition.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram of participant flow

See Table 1 for characteristics. No medication condition differences were significant for pre-treatment demographic, smoking or substance use variables.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics and treatment compliance: mean (standard deviation) or percentage.

| Full sample (n = 137) | Varenicline (n= 77) | Nicotine replacement therapy (n = 60) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Male | 53% | 55% | 51% |

| Race | |||

| White/Caucasian | 83% | 82% | 83% |

| Black/African American | 15% | 16% | 15% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | <1% | 1% | 0% |

| Multi-racial | 2% | 1% | 2% |

| Hispanic | 5% | 4% | 7% |

| Married or cohabiting | 13% | 9% | 18% |

| Annual household income | |||

| $0–9999 | 57% | 61% | 52% |

| $10000–29 999 | 28% | 26% | 30% |

| $30000–49 999 | 12% | 10% | 13% |

| $50000+ | 2% | 0% | 5% |

| Age | 39.6 (10.0) | 40.0 (10.5) | 39.2 (9.7) |

| Years education | 12.1 (2.20) | 12.1 (2.3) | 12.4 (2.1) |

| Employed | 13% | 12% | 15% |

| Cigarettes per day | 19.5 (7.4) | 20.4 (11.1) | 18.3 (9.3) |

| Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence | 5.5 (1.9) | 5.5 (1.9) | 5.5 (1.9) |

| History of life-time major depression | 28% | 28% | 29% |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 11.3 (8.1) | 11.9 (8.9) | 10.5 (6.9) |

| No. of past substance abuse treatments | 1.4 (1.27) | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.1) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 72% | 73% | 70% |

| Cocaine use disorder | 61% | 64% | 57% |

| Opiate use disorder | 34% | 35% | 34% |

| Marijuana use disorder | 23% | 35% | 22% |

| Percentage of heavy drinking days | 18.8 (27.8) | 18.8 (27.3) | 18.9 (28.6) |

| Percentage of drug use days | 21.9 (29.3) | 23.6 (30.2) | 19.9 (28.4) |

| Counseling sessions completed | 4.2 (2.5) | 4.2 (2.4) | 4.2 (2.6) |

| No. of weeks with 85% of capsules taken | 3.7 (4.2) | 3.4 (4.0) | 4.2 (4.5) |

| Percentage of capsules taken | 39.6 (37.1) | 37.4 (35.1) | 42.4 (39.7) |

| Percentage of patches used | 40.9 (39.0) | 40.0 (37.5) | 43.3 (41.0) |

Of participants reporting 7-day smoking abstinence, 95% (19 of 20) at week 5, 100% (of 17) at week 9, 86% (12 of 14) at 3 months, and 100% (of nine) at 6 months were confirmed abstinent. Of participants reporting abstinence from drugs at each follow-up, 91% (63 of 69) at 3 months and 95% (54 of 57) at 6 months were confirmed abstinent.

Compliance

There were no significant medication condition differences in number of counseling sessions attended or medication adherence (see Table 1). See Fig. 2 for weekly capsule use. (Patch adherence was collinear with capsule adherence, r = 0.89, so only capsule adherence was used.)

Figure 2.

Percentage of participants compliant with medication (> 85% of capsules) by assignment to varenicline versus placebo capsules after the week of dose run-up

Smoking outcomes

Smoking abstinence

For Aim 1, the primary outcome of smoking abstinence at 3 months just missed significance when analyzed without the covariate (13% for varenicline, 3% for NRT; odds ratio = 4.33, 95% confidence interval 0.91, 20.56, P = 0.065). A Bayes factor of 3.35 suggests that the data provide positive strong evidence in support of our hypothesis [53,56,57]. When including baseline smoking as a covariate, abstinence at 3 months differed significantly by medication condition. Treatment conditions did not differ significantly for smoking abstinence at 6 months with or without the covariate. A Bayes factor of 1.60 indicated only weak evidence for supporting the hypothesis [53,57], not enough evidence to distinguish our 6-month results from the null [56]. See Table 2 for results at each time-point and for statistics covarying pre-treatment smoking. For Aim 2, when also covarying medication adherence, GEE showed a significant medication effect on point-prevalence abstinence across both 3 and 6 months; those in varenicline were 6.4 times more likely to be abstinent during follow-up when covarying medication adherence (see Table 3). Main and interaction effects for time were not significant.

Table 2.

Outcomes by treatment condition: descriptive statistics and analyses at each time-point. Regressions were used for smoking variables with cigarettes per day included as a covariate; t-tests or χ2 tests were used for substance use or depression.

| Variable | Varenicline n (%) or mean (SD) (n = 77) | NRT n (%) or mean (SD) (n = 60) | n in analysis | Effect size d or OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Primary outcome: confirmed 7-day smoking abstinence at 3-month Follow-upa,b | 10/77 (13) | 2/60 (3) | 137 | 4.81* | 1.00, 23.13 |

| Confirmed 7-day smoking abstinenceb | |||||

| 5 weeks | 10/77 (13) | 9/60 (15) | 137 | 0.85 | 0.33, 2.26 |

| 9 weeks | 10/77 (13) | 7/60 (12) | 137 | 1.25 | 0.44, 3.55 |

| 6-month follow-upa | 7/77 (9) | 2/60 (3) | 137 | 3.17 | 0.63, 15.90 |

| Average no. cigarettes per dayc | |||||

| 3-month follow-up | 7.31 (7.35) | 4.96 (5.54) | 89 | 0.29 | −0.13, 0.72 |

| 6-month follow-up | 8.60 (7.88) | 9.62 (9.85) | 80 | −.02 | −.064, 0.26 |

| Percentage of smoking daysc | |||||

| 3-month follow-upd | 70.37 (38.79) | 62.39 (38.84) | 89 | 0.17 | −0.26, 0.59 |

| 6-month follow upe | 77.12 (37.61) | 84.52 (31.25) | 80 | −0.25 | −0.70, 0.20 |

| Longest continuous smoking abstinence weeks 9–13 c | 5.19 (9.96) | 3.75 (8.34) | 89 | 0.19 | −0.15, 0.53 |

| Relapse to any heavy drinkingb | |||||

| 3-month follow-up | 9/52 (17) | 7/37 (19) | 89 | 0.82 | 0.28, 2.44 |

| 6-month follow-up | 8/49 (16) | 9/31 (29) | 80 | 0.48 | 0.16, 1.41 |

| Number of heavy drinking daysc | |||||

| 3-month follow-upf | 3.18 (9.02) | 1.16 (5.11) | 89 | 0.19 | −0.22, 0.61 |

| 6-month follow-upf | 3.20 (10.26) | 3.71 (14.22) | 80 | −0.07 | −0.52, 0.38 |

| Relapse to any drug useb | |||||

| 3-month follow-up | 14/52 (27) | 12/37 (32) | 89 | 0.77 | 0.31, 1.93 |

| 6-month follow-up | 18/49 (37) | 8/31 (26) | 80 | 1.67 | 0.62, 4.50 |

| Number of drug use daysc | |||||

| 3-month follow-upf | 2.25 (6.29) | 2.89 (14.78) | 89 | 0.15 | −0.26, 0.57 |

| 6-month follow-upg | 5.94 (17.87) | 3.74 (14.32) | 80 | 0.24 | −0.21, 0.69 |

| Beck Depression Inventorya | |||||

| 2 weeks | 6.75 (6.79) | 5.64 (6.05) | 107 | 0.17 | −0.02, 0.56 |

| 5 weeks | 6.51 (8.22) | 5.59 (7.42) | 93 | 0.12 | −0.29, 0.53 |

| 9 weeks | 4.50 (6.06) | 6.34 (7.97) | 78 | −0.26 | −0.72, 0.19 |

| 3-month follow-up | 5.75 (8.47) | 5.19 (6.53) | 89 | 0.07 | −0.07, 0.52 |

All participants were included in this analysis due to positive imputation.

Dichotomous variable; effect size is expressed as an odds ratio.

Continuous variable; effect size is in standardized units of the dependent variable (d).

Percentage of smoking days 3-month follow-up, median = 88.33, interquartile range = 82.78. As significantly skewed, values were log-transformed prior to analysis.

Percentage of smoking days 6-month follow-up: median = 100, interquartile range = 24.17. As significantly skewed, values were log-transformed prior to analysis.

Number of heavy drinking days 3- and 6-month follow-up, number of drug use days 3-month follow-up: median = 0.00, interquartile range = 1.00. As significantly skewed, values were log-transformed prior to analysis. SD = standard deviation; NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Number of drug use days 6 month follow up: median = 0.00, interquartile range = 0.00. As significantly skewed, values were log-transformed prior to analysis.

P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Analyses of smoking outcomes by medication and time [generalized estimating equations (GEE)] while covarying amount of capsules taken and baseline smoking.

| Dependent variable | Predictor | Model coefficient | SE | Wald | Effect size d or OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 3- and 6-month follow-up | |||||||

| 7-day point-prevalence abstinencea,b | |||||||

| Varenicline (versus NRT) | 1.86 | 0.95 | 3.84 | 6.40 | 1.00, 40.93 | 0.05 | |

| Pre # cigarettes/day | −0.07 | 0.03 | 5.19 | 0.93 | 0.87, 0.99 | 0.02 | |

| % capsules taken | 0.03 | 0.01 | 8.00 | 1.03 | 1.01, 1.05 | 0.01 | |

| Time (centered) | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.22, 4.47 | 1.00 | |

| Time × medication | −0.48 | 0.88 | 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.11, 3.47 | 0.58 | |

| Number of cigarettes per dayc | |||||||

| Varenicline (versus NRT) | 1.04 | 1.12 | 0.87 | 0.13 | −0.15, 0.42 | 0.35 | |

| Pre # cigarettes/day | 0.39 | 0.08 | 22.15 | 0.05 | 0.03, 0.07 | <0.01 | |

| % capsules taken | −0.06 | 0.02 | 10.95 | −0.01 | −0.01, 0.00 | <0.01 | |

| Time (centered) | 4.46 | 1.32 | 11.43 | 0.57 | 0.24, 0.90 | <0.01 | |

| Time × medicationd | −3.12 | 1.54 | 4.07 | −0.79 | −0.79, −0.01 | 0.04 | |

| Percentage of smoking daysc | |||||||

| Varenicline (versus NRT) | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.37, 0.46 | 0.82 | |

| Pre # cigarettes/day | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.56 | 0.33 | −0.54, 1.20 | 0.46 | |

| % capsules taken | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.53 | 0.00 | −0.01, 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Time (centered) | 0.20 | 0.07 | 8.59 | 0.36 | 0.12, 0.60 | <0.01 | |

| Time × medicatione | −0.22 | 0.11 | 3.83 | −0.40 | −0.79, 0.00 | 0.05 | |

| Within-treatment: weeks 5 and 9 | |||||||

| 7-day point-prevalence abstinencea,b | |||||||

| Varenicline (versus NRT) | −0.12 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.88 | 0.33, 2.36 | 0.81 | |

| Pre # cigarettes/day | −0.03 | 0.02 | 3.55 | 0.97 | 0.94, 1.00 | 0.06 | |

| Time (centered) | −0.29 | 0.35 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.37, 1.50 | 0.41 | |

| Time × medicationc | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 1.34 | 0.58, 3.07 | 0.49 | |

All participants were included in this analysis due to positive imputation.

Dichotomous variable; effect size is expressed as an odds ratio.

Normally distributed variable; effect size is in standardized units of the dependent variable (d).

Simple slopes test within nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), Wald , P < 0.001.

Simple slopes test within NRT (nicotine replacement therapy), Wald , P < 0.004. SE = standard error; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Secondary smoking variables

For Aim 3, for both cigarettes per day and percentage of smoking days, there was no main effect for medication condition but significant main and interaction effects for time (see Table 3), with a significant increase during the 6 month follow-up period in each smoking variable within the NRT condition but not within the varenicline condition (see Table 2 for means, Table 3 for simple slopes tests). For Aim 4, the longest continuous abstinence and within-treatment abstinence were not significantly different by medication group.

Moderator analyses (Aim 6)

Moderation of medication effects on 3-month point-prevalence abstinence by adherence showed a trend for significance, B = 0.04, standard error (SE) = 0.02, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.003, 0.09, P < 0.06. In simple slopes tests, abstinence at 3 months was significantly greater for varenicline versus NRT when adherence was ≥1 SD above the mean, B = 2.21, SE = 0.94, 95% CI = −363, 4.05, P < 0.02, but not when around the mean or below the mean. The predicted conditional probability of abstinence for participants with high adherence (77% or more of capsules taken) was 27% for varenicline versus 4% for NRT. There was no significant moderation by gender, MDD or nicotine dependence.

Safety and substance use

Adverse events

There were no medication-attributable serious adverse events. Twenty participants were discontinued from capsules due to non-serious adverse events, 11 on varenicline [one each for agitation, depression or seizure (with a history of seizures and her physician thought other changes were possible causes); other events were insomnia/nightmares, rash, upset stomach, anxiety)] and eight on NRT (one for agitation, three for depression; other events were insomnia/nightmares, rash, anxiety, tension and itch).

Depressive symptoms

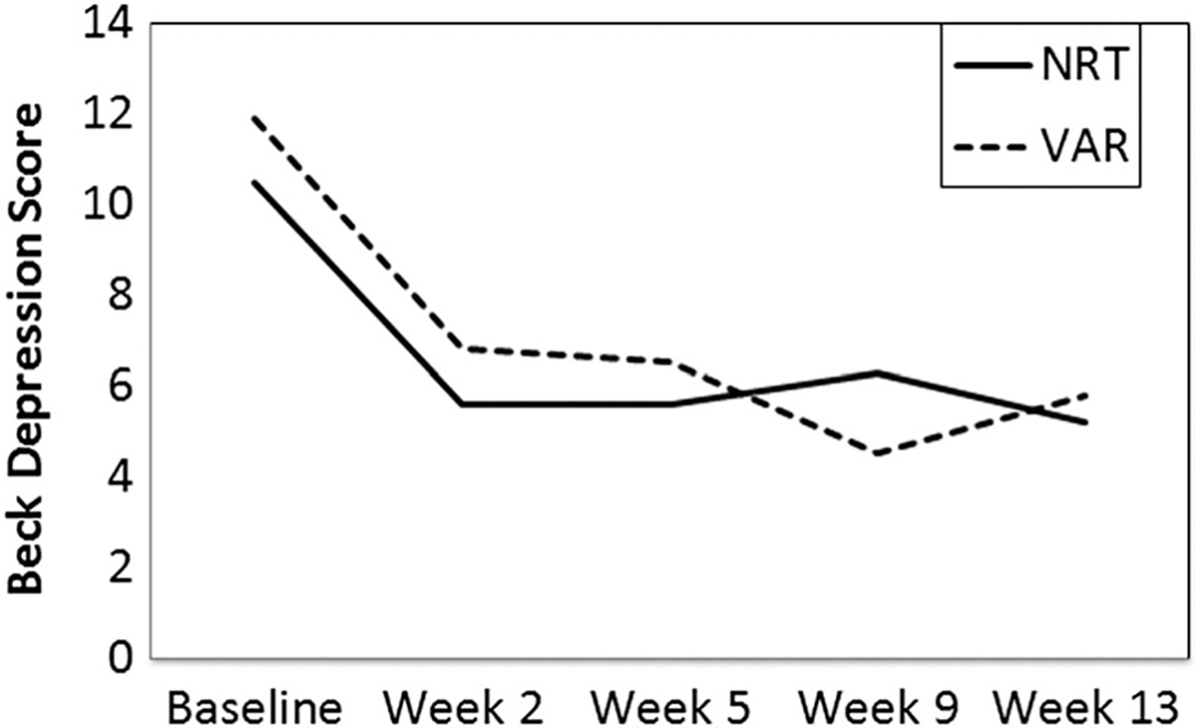

For Aim 4, GEE was not significant for medication nor medication × time, but showed a significant main effect for time (see Fig. 3). Adding history of MDD to the GEE showed no significant main or interaction effects with MDD.

Figure 3.

Beck Depression Inventory score at baseline and weeks 2, 5, 9 and 13 after starting dose run-up. generalized estimating equations (GEE) showed a significant main effect for time, Wald χ2 (d.f. = 1) = 13.43, P < 0.001, but not for medication or medication by time. Depression scores decreased from pre-treatment to week 2 [mean difference = −4.99, standard error (SE) = 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −7.65, −2.33), P < 0.01], with no significant change thereafter. NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; VAR = varenicline

Substance use

For Aim 5, GEEs (see Table 4) showed no significant effects. Fewer than 4% of days involved any heavy drinking and fewer than 7% of days involved drug use (Table 2).

Table 4.

Analyses of substance use at follow-up by medication and time [generalized estimating equations (GEE)] and covarying amount of capsules taken and baseline value of the substance use variable.

| Dependent variable | Predictor | Model coefficient | SE | Wald | d or OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Relapse to any heavy drinkingb | |||||||

| Varenicline (versus NRT) | −0.36 | 0.58 | 0.38 | 0.71 | 0.22, 2.18 | 0.54 | |

| Pre-heavy drinking days | 0.56 | 0.26 | 3.85 | 1.68 | 1.00, 2.81 | 0.05 | |

| % capsules taken | −0.02 | 0.01 | 4.20 | 0.99 | 0.97, 1.00 | 0.04 | |

| Time (centered) | 0.58 | 0.33 | 3.16 | 1.79 | 0.94, 3.38 | 0.08 | |

| Time × medication | −0.59 | 0.49 | 1.42 | 0.55 | 0.21, 1.45 | 0.23 | |

| Number of heavy drinking daysa | |||||||

| Varenicline (versus NRT) | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.13 | −0.22, 0.47 | 0.48 | |

| Pre-heavy drinking days | 0.09 | 0.04 | 5.36 | 0.22 | 0.03, 0.40 | 0.02 | |

| % capsules taken | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.45 | 0.00 | −0.01, 0.00 | 0.12 | |

| Time (centered) | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.59 | 0.21 | −0.12, 0.53 | 0.21 | |

| Time × medication | −0.13 | 0.08 | 2.40 | −0.30 | −0.67, 0.08 | 0.12 | |

| Relapse to any drug useb | |||||||

| Varenicline (versus NRT) | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 1.57 | 0.61, 3.99 | 0.35 | |

| Pre # drug use days | −0.32 | 0.24 | 1.81 | 0.72 | 0.45, 1.16 | 0.18 | |

| % capsules taken | 0.01 | 0.01 | 3.07 | 1.01 | 0.10, 1.02 | 0.08 | |

| Time (centered) | 0.10 | 0.07 | 2.15 | 1.11 | 0.97, 1.27 | 0.14 | |

| Time × medication | −0.60 | 0.32 | 3.31 | 0.55 | 0.29, 1.05 | 0.07 | |

| Number of drug use daysa | |||||||

| Varenicline (versus NRT) | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.01 | −0.13, 0.15 | 0.89 | |

| Pre # drug use days | 0.12 | 0.04 | 7.11 | 0.12 | 0.30, 0.21 | 0.46 | |

| % capsules taken | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.65 | 0.00 | −0.01, 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Time (centered) | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.44 | 0.06 | −0.11, 0.22 | 0.51 | |

| Time × medication | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.33 | 0.06 | −0.14, 0.26 | 0.56 | |

Normally distributed variable; effect size is in standardized units of the dependent variable (d).

Dichotomous variable; effect size is expressed as an odds ratio. NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; SE = standard error; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Varenicline was more effective than NRT in producing point-prevalence smoking abstinence 3 months after medication started (the primary outcome) in smokers with SUD who had not sought smoking treatment, with four times greater odds observed with varenicline (13 versus 3% abstinent for NRT). When analyzed without covarying pre-treatment smoking levels, the evidence was strong that varenicline increases smoking abstinence at 3 months compared to NRT according to the Bayes factor, and the results were significant when controlling for pre-treatment levels of smoking. Differences were no longer significant at 6 months, when 9% of smokers were still abstinent on varenicline compared to 3% on NRT (comparable with the 2% abstinent at 3 and 6 months in our previous study with NRT [28]). This indicated that varenicline had less effect after 3 months off of it when people needed to stay abstinent without the help of a medication, consistent with other studies in this population [4]. However, clinicians also want to know how well a medication works for patients who take more of it. When accounting for amount of medication adherence in analyses, an average of 6.5 times as many people on varenicline compared to NRT had confirmed 7-day point-prevalence abstinence across 3 and 6 months (a significant difference) in analyses of medication × time effects, with no significant decrease over time. When looking at the participants who took at least 77% of the capsules they were given (1 SD above the mean), much larger differences in 3-month abstinence occurred: 27% for varenicline versus 4% for NRT. Thus, for these smokers with substance use disorders who took most of the medication, varenicline worked considerably better than NRT at 3 months and with no significant decrease in effects at 6 months.

In a review of smoking treatments for smokers in SUD treatment [4], only five of 17 studies found effects at 6 months (nicotine patch or gum, behavioral treatment or some combination), with four other studies finding effects at 3 months or less (behavioral treatment, patch or counseling plus exercise), with no effect of varenicline versus NRT in the only study to investigate it [27]. Thus, this is the first study to find more smoking cessation with varenicline than NRT in this population, although differences were only significant at 3 months and the study was underpowered to detect the differences that occurred at 6 months.

Other secondary analyses showed that while NRT and varenicline had nearly equivalent effects during the first 9 weeks of treatment, thereafter the benefits of NRT decreased markedly for abstinence, cigarettes per day and frequency of smoking, while the benefits of varenicline were mainly maintained. Our findings are notable, given several important aspects of this study: first, smokers did not need to be seeking smoking cessation to enroll; the study was designed to increase motivation while reducing barriers to cessation. Secondly, medication adherence was equivalently poor for both medications, with only 63% of participants taking most of their capsules during the first week after dose run-up, only 40–41% of all patches or capsules used and with on average 3.5–4-week adherence, so varenicline seemed to maintain effects after stopping it more effectively than did NRT. It is important to show that a medication can produce effects that persist after the medication is discontinued not just while taking it, as does this study, especially in smokers not very motivated to quit smoking. Thus, even in a SUD population that struggles with motivation and adherence, varenicline can improve smoking cessation 3–6 months after starting it in those who take most of it. Given that varenicline can be used with most smokers who rule out bupropion due to comorbid conditions or medications, this means varenicline with brief counseling may be a more effective treatment for smokers with SUD.

The lack of any significant increase in suicidality, depression or serious events despite 28% of participants having comorbid MDD is consistent with large randomized studies of smokers in the general population with or without psychiatric disorders [17]. The lack of any significant ill effects on substance recovery is also consistent with all other studies of voluntary smoking treatments [14,58]. Beneficial effects of varenicline on heavy drinking seen elsewhere [25] may have not been detectable, because all were alcohol-abstinent at treatment initiation, so little heavy drinking occurred. Thus, given the preponderance of evidence across studies, varenicline can apparently be used in early recovery from SUD even with patients with a history of MDD who are not currently suicidal.

Varenicline’s effects on smoking did not differ significantly by gender, MDD or degree of nicotine dependence. Women have 31% lower odds than men of quitting smoking without medications [46]. However, this study is consistent with others that found no significant differences in odds of quitting smoking for men versus women when using varenicline or NRT [46,59].

Limitations

There was insufficient power to detect the threefold difference in abstinence observed in 6-month outcomes. However, the lack of significant differences in substance use outcomes or depressive symptoms did not appear to reflect low power, given their small effect sizes. This study is limited to one low-income urban population with 17% minorities. Results may underestimate medication effectiveness among smokers with SUD who are seeking smoking treatment. We did not test varenicline against combination NRT, but in a study [28] where we offered combination NRT, only approximately 1% of smokers with SUD used anything but patches, suggesting low acceptance of combination NRT in smokers with SUD, at least in this community. Complier average causal effect modeling could improve the accuracy of evaluating treatment benefit for those adhering to medication, but we did not use this type of modeling.

Conclusions

There is strong evidence that varenicline increased smoking abstinence at 3 months compared to NRT for smokers with SUD regardless of MDD. Although the rates of abstinence were modest compared to results with smokers in the general population who had sought smoking treatment, abstinence results were favorable when compared to many other randomized trials of smokers in early SUD recovery, at least for short-term effects. Furthermore, effects of varenicline versus NRT at 6 months were approximately double those from a major meta-analysis [16], suggesting that low power prevented the 6-month results from reaching significance. By reducing the aversiveness of cessation [20,21], varenicline may make these smokers more willing to attempt cessation. However, ways to improve adherence to medication in this population are very much needed.

Supplementary Material

Table S1 Multiple Imputation Results of Medication Condition Effects on Smoking Outcomes: Descriptive statistics are the averaged results across the imputations without adjustment for the covariate. Effect size estimates covary baseline cigarettes per day.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Appendix S1 Multiple Imputation Analysis.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant 1R01DA024652 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to D.J.R. and by a Senior Career Research Scientist Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs to D.J.R. The funding agencies had no further role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Grateful appreciation is expressed to Suzanne Sales for her data analyses. Preliminary results were presented at the 2015 meetings of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Philadelphia, PA; of the College on Problems in Drug Dependence, Phoenix, AZ; and of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco—Europe, Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

All authors report no financial interests or potential conflicts of interest except for the following: R.M.S. has received travel and honorarium from D&A Pharma and has received consultant fees from CT Laboratories.

Clinical trial registration

Clinical trials.gov identifier: NCT00756275.

While 12-month follow-ups were planned, funding ran out before enough were collected for valid analyses.

References

- 1.Hurt RD, Patten CA Treatment of tobacco dependence in alcoholics. Recent Dev Alcohol 2003; 16: 335–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, Morse RM et al. Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment: Role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA 1996; 275: 1097–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zacny JP Behavioral aspects of alcohol-tobacco interactions. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism: Volume 8. Combined Alcohol and Other Drug Dependence. New York: Plenum Press; 1990, pp. 205–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thurgood SL, McNeill A, Clark-Carter D, Brose LS A systematic review of smoking cessation interventions for adults in substance abuse treatment or recovery. Nicotine Tob Res 2016; 18: 993–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes JR Treatment of smoking cessation in smokers with past alcohol/drug problems. J Subst Abuse Treat 1993; 10: 181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurt RD, Dale LC, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Hays JT, Gomez-Dahl L Nicotine patch therapy for smoking cessation in recovering alcoholics. Addiction 1995; 90: 1541–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hays JT, Schroeder DR, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Patten CA, Hurt RD et al. Response to nicotine dependence treatment in smokers with current and past alcohol problems. Ann Behav Med 1999; 21: 244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novy PL, Hughes JR, Jensen JA, Hatsukami DK, Huston J The efficacy of the nicotine patch in recovering alcoholic smokers. In: Harris L, editor. Problems of Drug Dependence 1998. NIDA Research Monograph no. 179. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. p. 91 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin RA, Rohsenow DJ, MacKinnon SV, Abrams DA, Monti PM Correlates of motivation to quit smoking among alcohol dependent patients in residential treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006; 83: 73–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter KP, Gibson CA, Ahluwalia JS, Schmelzle KH Tobacco use and quit attempts among methadone maintenance clients. Am J Public Health 2001; 91: 296–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohsenow DJ, Martin RA, Tidey JW, Monti PM, Colby SM Comparison of the cigarette dependence scale with four other measures of nicotine involvement: correlations with smoking history and smoking treatment outcome in smokers with substance use disorders. Addict Behav 2013; 38: 2409–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohsenow DJ, Tidey JW, Kahler CW, Martin RA, Colby SM, Sirota AD Intolerance for withdrawal discomfort and motivation predict voucher-based smoking treatment outcomes for smokers with substance use disorders. Addict Behav 2015; 43: 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin RA, Cassidy R, Murphy C, Rohsenow DJ Barriers to quitting smoking among substance dependent patients predict outcome. J Subst Abuse Treat 2016; 64: 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohsenow DJ Why we should treat smoking in substance dependence programs. Addict Newsletter; 2015; Spring: 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberger AH, Platt J, Jiang B, Goodwin RD Cigarette smoking and risk of alcohol use relapse among adults in recovery from alcohol use disorders. Alc Clin Exper Res 2015; 39: 1989–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancanster T Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; Issue 5. Art. No.: CD009329. 10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, St Aubin L, McRae T, Lawrence D et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 2507–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grassi MC, Enea D, Ferketich AK, Lu B, Pasquariello S, Nencini P Effectiveness of varenicline for smoking cessation: a 1-year follow-up study. J Subst Abuse Treat 2011; 411: 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB et al. Varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs. sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006; 296: 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs. placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking-cessation. JAMA 2006; 296: 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashare RL, Tang KZ, Mesaros AC, Blair IA, Leone F, Strasser AA Effects of 21 days of varenicline versus placebo on smoking behaviors and urges among non-treatment seeking smokers. J Psychopharmacol 2012; 2610: 1383–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandon TH, Drobes DJ, Unrod M, Heckman BW, Oliver JA, Roetzheim RC et al. Varenicline effects on craving, cue reactivity, and smoking reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011; 2182: 391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gass JC, Wray JM, Hawk LW, Mahoney MC, Tiffany ST Impact of varenicline on cue-specific craving assessed in the natural environment among treatment-seeking smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012; 223: 107–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKee SA, Harrison EL, O’Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Tetrault JM et al. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 662: 185–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Fertig JB, Falk DE, Johnson B, Dunn KE et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy of varenicline tartrate for alcohol dependence. J Addict Med 2013; 74: 277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nahvi S, Ning Y, Segal KS, Richter KP, Arnsten JH Varenicline efficacy and safety among methadone maintained smokers: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Addiction 2014; 1099: 1554–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein MD, Caviness CM, Kurth ME, Audet D, Olson J, Anderson BJ Varenicline for smoking cessation among methadone-maintained smokers: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013; 1332: 486–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohsenow DJ, Martin RA, Monti PM, Colby SM, Day AM, Abrams DB et al. Motivational interviewing versus brief advice for cigarette smokers in residential alcohol treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2014; 46: 346–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acosta MC, Haller DL, Schnoll SH Cocaine and stimulants. In: Frances RJ, Miller SI, Mack AH, editors. Clinical textbook of addictive disorders, 3rd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2005, pp. 184–218. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. USDHHS, Rockville, MD: USDHHS: US Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manley M, Epps RP, Husten C, Glynn T, Shopland D Clinical interventions in tobacco control. A National Cancer Institute training program for physicians. JAMA 1991; 266: 3172–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stout RL, Wirtz P, Carbonari JP, Boca FD Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol 1994, Supplement No. 12, 70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström K-O The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict 1991; 86: 1119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes JR, Novy P, Hatsukami DK, Jensen J, Callas PW Efficacy of nicotine patch in smokers with a history of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003; 27: 946–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollis JF, Lichenstein E, Vogt TM, Stevens VJ, Biglan A Nurse-assisted counseling for smokers in primary care. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118: 521–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strecher VJ, Rimer BK, Monaco KD Development of a new self-help guide—freedom from smoking® for you and your family. Health Educ Q 1989; 16: 101–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sobell LC, Sobell MB Can we do without alcohol abusers’ self-reports? Behav Therapist 1986; 7: 141–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition SCID-I/P, version 2.0. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychol Addict Behav 1998; 12: 101–12. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ Reliability and validity of 6-month timeline reports of cocaine and heroin use in a methadone population. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62: 843–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobell LC, Sobell MB Convergent validity: An approach to increasing confidence in treatment outcome conclusions with alcohol and drug abusers. In: Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Ward E, editors. Evaluating Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Effectiveness: Recent Advances. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1980, pp. 177–83. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flannery BA, Allen JP, Pettinati HM, Rohsenow DJ, Cisler RA, Litten RZ Using acquired knowledge and new technologies in alcoholism treatment trials. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002; 26: 423–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cropsey KL, Trent LR, Clark CB, Stevens EN, Lahti A, Hendricks PS How low should you go? Determining the optimal cutoff for exhaled carbon monoxide to confirm smoking abstinence when using cotinine as a reference. Nicotine Tob Res 2014; 16: 1348–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res 2003; 5: 13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Jao NC Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res 2013; 15: 978–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith PH, Kasza KA, Hyland A, Fong GT, Borland R, Brady K et al. Gender differences in medication use and cigarette smoking cessation: results from the international tobacco control four country survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2015; 17: 463–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. In: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available at: http://handbook.cochrane.org/ (accessed 8 June 2017) (Archived at www.webcitation.org/6r4P7Kq05). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubin DB Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 50.SAS/STAT User’s Guide: Version 12.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenbaum PR Sensitivity analysis in observational studies. Encyclopedia Stats Behav Sci 2005; 4: 1809–14. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schafer JL, Graham JW Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods 2002; 7: 147–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarosz AF, Wiley J What are the odds? A practical guide to computing and reporting Bayes factors. J Prob Solv 2014; 7: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeger SL, Liang K-Y Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986; 42: 121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayes AF Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raftery AE Bayesian model selection in social research. In: Marsden PV, editor. Social Methodology 1995. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell; 1995, pp. 111–96. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeffreys H Theory of Probability, 3rd edn. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rohsenow DJ, Tidey JW, Martin RA, Colby SM, Sirota AD, Swift RM et al. Contingent vouchers and motivational interviewing for cigarette smokers in residential substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2015; 55: 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McKee SA, Smith PH, Kaufman M, Mazure CM, Weinberger AH Sex differences in varenicline efficacy for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2015; 18: 1002–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Multiple Imputation Results of Medication Condition Effects on Smoking Outcomes: Descriptive statistics are the averaged results across the imputations without adjustment for the covariate. Effect size estimates covary baseline cigarettes per day.