Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) can have highly variable clinical manifestations and there is limited coverage in the literature on its ocular manifestation. GCA is a large vessel vasculitis classically affecting the branches of the common carotid artery and is associated with end organ ischemia that could precipitate blindness if left untreated. The incidence of GCA is approximately 52 cases per 100,000 people according to a large meta-analysis and it is typically seen in middle-aged to elderly females.1 The clinical manifestations of GCA include malaise, weight loss, fever, night sweats, proximal muscle pain, headaches, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, and visual loss.2 Current existing diagnostic criteria, established by consensus from the American College of Rheumatologists (ACR) and the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) include clinical, laboratory, and ultrasound criteria which have not been updated for some time, and therefore could potentially lead to inaccurate diagnosis and risk stratification.3 As the population continues to age, the incidence and mortality of GCA are expected to increase and lead to permanent vision loss in the absence of prompt diagnosis and treatment.

GCA patients may be initially seen in departments other than ophthalmology owing to the diversity of its clinical manifestations. Consequently, clinicians from all specialties should be familiar with the ocular manifestations of GCA to allow for a prompt diagnosis, which relies on laboratory values, temporal artery biopsy (TAB), and some form of vascular imaging for best pre-test probability.4 Immediately upon diagnosis, high-dose glucocorticoids should be administered in order to prevent the worsening of ischemic manifestations.5 Although immunosuppressive monoclonal antibody therapy such as with tocilizumab can be used for maintenance management for GCA,5 ongoing clinical studies are currently being conducted to help determine the comparative efficacy of various classes of immunosuppressive medications and adequate treatment duration to prevent relapse. This review focuses on the ocular manifestations of GCA while discussing current and upcoming diagnostic and management strategies. Increased awareness of diagnostic pathways of GCA can improve the disease prognosis and prevent permanent blindness in many patients.

Ocular Manifestations of GCA

Ocular Symptoms

The incidence of any form of visual symptoms such as ocular pain, diplopia, amaurosis fugax, or vision loss in GCA can vary widely according to published studies.6,7 Transient ophthalmic manifestations such as amaurosis fugax and diplopia are commonly associated with GCA. Amaurosis fugax is a form of transient vision loss that can either be monocular or binocular, typically due to decreased perfusion of the optic nerve or retina.8 Diplopia is also another transient ocular symptom that can occur with GCA due to involvement of the arterial branches of the ophthalmic artery supplying oculomotor nerves or muscles.8,9 Prior studies have found that a notable number of patients that experienced these ocular symptoms subsequently suffered from permanent vision loss.8–10 Many of these patients can also present with ocular symptoms without any additional systemic findings indicative of GCA, which may add another layer of complexity. Given that these transient ocular symptoms can often be an early sign of impending blindness, it is crucial to consider GCA in patients presenting with amaurosis fugax or diplopia to allow for timely treatment.

Ophthalmic vessel involvement

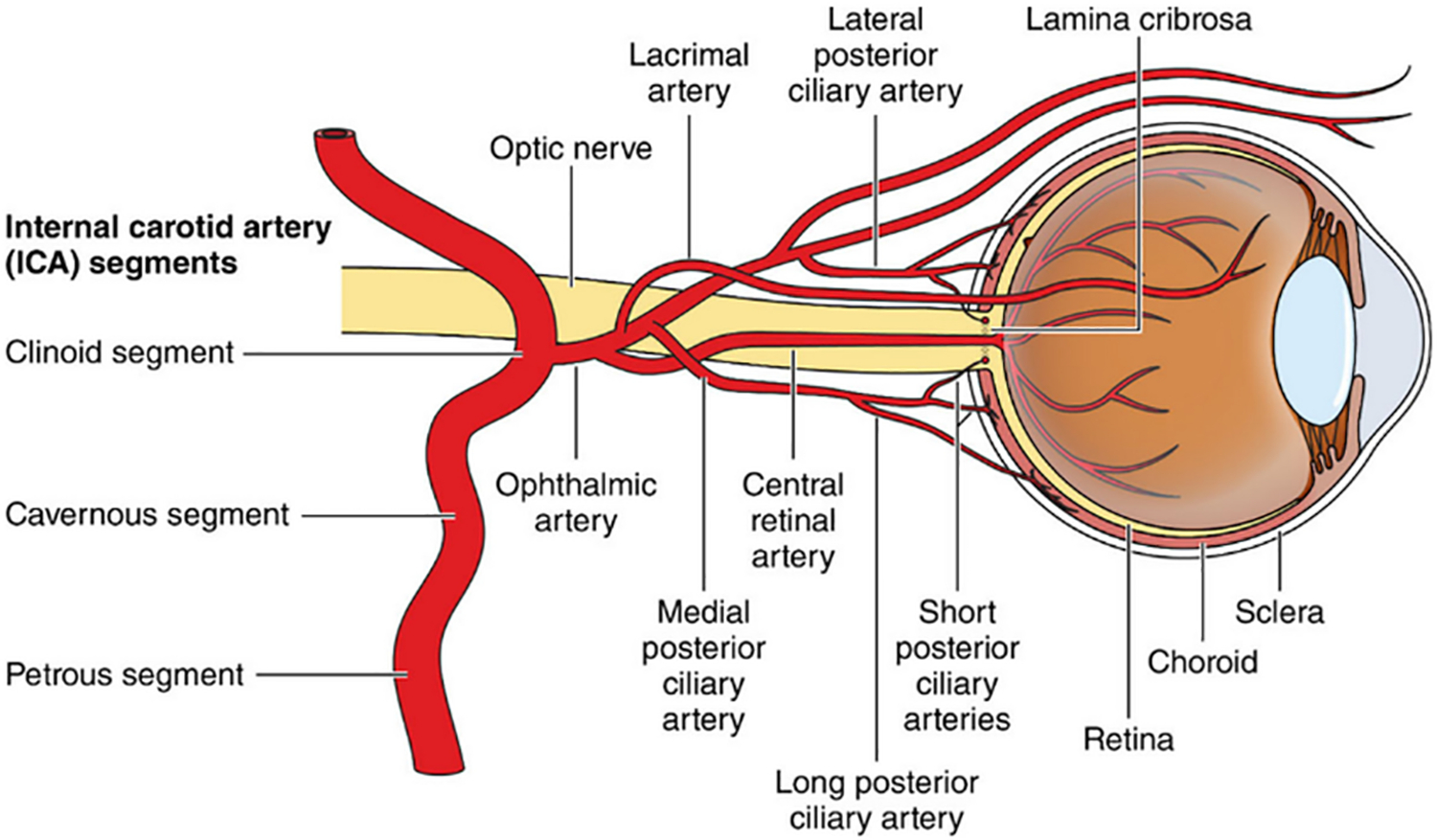

Table 1 lists publications the various cohort studies on GCA and ophthalmic vessel involvement. The most common ophthalmic condition associated with GCA is arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (A-AION) and is responsible for approximately 80% of patients’ prognosis of permanent vision loss.8,11 Since the posterior ciliary artery (PCA) is the main source of blood supply to the optic nerve head which lacks anastomoses with surrounding arteries, any blood flow interruption could lead to optic nerve head infarction and atrophy with cupping.12 Figure 1 demonstrates the blood supply to the retina. Under ophthalmoscopy, the optic disc can appear chalky due to edema and cotton wool spots (Figure 2B) or choroidal ischemia can also be visualized in the posterior fundus.13,14 Choroidal ischemia as an ocular manifestation of GCA has been well demonstrated in the past.15

Table 1.

List of most recent cohort studies for GCA and visual outcomes

| First Author | Title of case | Number of cases/patients | TAB (yes/no) | Findings On Ophthalmic Imaging | Imaging | Treatment | Visual Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaël Dumont64 | Characteristics and Outcomes of patients with ophthalmologic involvement in GCA | 409 patients, 104 with visual symptoms | Yes | Optic disc edema, AION | FA, FP | IV pulses of MP, oral medication | Vision loss, amaurosis fugax, diplopia, and blurred vision |

| Qian Chen65 | GCA presenting with ocular symptoms: Clinical Characteristics and Multimodal Imaging in a Chinese Case Series | 15 patients | Yes | Optic disc edema with thickening GCC and RNFL | OCT, CDUS, MRI | IV pulses of MP, oral medication | Most patients had poor visual function but could still perceive light and less than half had permanent vision loss |

| Emman-uel Héron66 | Ocular Complications of Giant Cell Arteritis: An Acute Therapeutic Emergency | 54 patients | Yes | Chalky white optic disc edema, cilioretinal artery occlusion, cotton wool spots | FP, CDUS, MRI | Corticosteroids | Amaurosis fugax and permanent blindness |

| Mariana Portela67 | Giant cell arteritis: Is there a link between ocular and systemic involvement? | 51 patients | Yes | N/A | CDUS | Corticosteroid | Ocular migraines, diplopia, occipital seizures, and permanent vision loss |

| Carlo Salvarani57 | Risk factors for visual loss in an Italian population – based cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis | 136 patients | Yes | N/A | N/A | Oral and IV corticosteroids | Amaurosis fugax, diplopia, permanent vision loss |

| Antonio Casella15 | Choroidal ischemia as one cardinal sign in giant cell arteritis | 8 patients | Yes | Choroidal ischemia, paracentral acute middle maculopathy lesions, cotton wool spots, AION, and CRAO | FP, FA, OCT, and OCT-A | Corticosteroids | Amaurosis fugax, permanent vision loss |

| Alexandre Dentel68 | Use of Retinal Angiography and MRI in the Diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis with Early Ophthalmic Manifestations | 25 patients | Yes | Choroidal ischemia, cilioretinal artery occlusion, AION, CRAO | FA, ICG, MRA | N/A | Amaurosis fugax, diplopia, and permanent vision loss |

Figure 1:

Blood supply to the retina. From Stroke.2021;52:e282-e294 ©2021 American Heart Association, Inc., with permission.62

Figure 2:

[A] is a normal OPTOS widefield image of the right eye which is the unaffected eye. [B] is an OPTOS widefield image of the left eye, which was affected with a cilioretinal artery occlusion. The cotton wool spot (yellow arrow) can be appreciated along the inferior aspect of the macula. [C] is an optical coherence tomography of the left eye affected with the cilioretinal artery occlusion and a paracentral acute middle maculopathy (red arrow) can be appreciated by the hyperreflective (whitening) band-like lesion in the inner nuclear layer of the retina along the inferior aspect of the macula. [D] is a fluorescein angiogram of the left eye affected with the cilioretinal artery occlusion demonstrating delayed filling (green arrow) in the inferior aspect of the macula.

Another ischemic condition affecting the optic nerve in GCA patients include arteritic posterior ischemic optic neuropathy (A-PION); this occurs less commonly than A-AION.8 A-PION is due to ischemia in the posterior segment of the optic nerve. This portion of the optic nerve is supplied by the pial capillary plexus, which contains many collateral branches that provide anastomoses with one another therefore decreasing the visibility of optic nerve abnormalities (pallor, edema) on ophthalmoscopy.16 To further aid in the diagnosis of these ischemic ocular conditions of the optic nerve, testing for visual acuity, direct visualization of the optic nerve, and visual field testing with Humphrey visual field should be deployed. These ocular conditions associated with GCA is an ophthalmic emergency and requires prompt treatment to prevent further irreversible vision loss.

The central retinal artery (CRA) is a branch of the ophthalmic artery that can be occluded in GCA patients, resulting in central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) and permanent blindness. During fundoscopic examination of CRAO, there is a distinct cherry-red spot visible at the maula from ischemia leading to paleness of the retina. In a prior study, the incidence of CRAO was 12% of the eyes in GCA patients.8 This is a result of the CRA branching from the ophthalmic artery with an anastomosis with the PCA; however, the anastomosis is not enough to prevent ischemia.17 Another artery that branches directly or indirectly from the PCA is the cilioretinal artery which can also become occluded (Figures 2A – 2D). For such a rare ocular presentation, there are limited numbers of studies describing cilioretinal artery occlusion being associated with GCA.18,19 These case presentations describe optic disc pallor with the addition of a retinal infarct along the region of the cilioretinal artery leading to choroidal hypoperfusion.18,20 To enhance the diagnosis of retinal artery occlusive conditions, direct fundus visualization for retinal whitening and ancillary diagnostic ophthalmic imaging should be utilized. A prior study demonstrated that visual outcome of patients with GCA due to CRAO is poor even after steroid treatment.7 Even though prognosis is poor, timely diagnosis and recognition of GCA associated retinal ischemia is essential to prevent vision loss in the fellow eye.

Diagnostic Approaches for GCA

To diagnose GCA, it is essential to have a complete clinical framework of recognizing clinical symptoms, laboratory testing, diagnostic imaging, and histopathological findings. The symptom of jaw claudication appears to be the most specific symptom as the odds of a positive TAB were nine times greater when presenting with this symptom.21 The non-specific inflammatory markers of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels can aid in the diagnosis. CRP was shown to be more sensitive (100%) than ESR (92%) for the detection of GCA, but the combination of both laboratory results give the specificity (97%) for GCA.21

There are various imaging modalities that can aid in the diagnosis of GCA including color doppler ultrasound (CDUS), computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and positive electron tomography-computerized tomography (PET-CT). Although each of these imaging modalities has its own advantages and disadvantages, there is a current lack in the literature of comparative diagnostic effectiveness data. The detection of the halo sign on ultrasound (Figure 3), which is a dark area surrounding the lumen of the temporal arteries on CDUS has good accuracy for the diagnosis of GCA.22 CTA and MRA can be utilized to better visualize larger arteries in order to diagnose GCA if the temporal arteries are not affected.22 The Vessel Wall Imaging Study Group of the American Society of Neuroradiology recently outlined the utilization of black-blood MRI which suppresses the signal of blood flow therefore allowing enhancement of the vessel walls to detect inflammation.23 One prior study utilized the black-blood MRI technique in detecting GCA and found that imaging demonstrated inflammatory findings within the orbit.24 Another study also supports this imaging modality as the results showed good diagnostic accuracy and reliability when it comes to detecting GCA in the superficial cranial arteries.25 The use of MRA as the first imaging examination followed by ultrasound or ophthalmic imaging has been shown to have the best diagnostic performance for identifying GCA.26 PET-CT has also been shown to help aid in the early diagnosis of GCA with high sensitivity and specificity. There appears to be a positive correlation between the development of angiographic change in GCA with PET activity.27 However, it has also been demonstrated that the initiation of corticosteroids can lead to a false negative result, although there may be some benefit from utilizing this modality to monitor GCA disease activity after treatment initiation.28 According to a prior study, the use of tocilizumab for patients with GCA demonstrated reduction of vascular inflammation measured with PET and this shows that it could be a useful tool to monitor response to certain treatments for GCA.29 In contrast, there have also been varying reports about the utility of FDG-PET to monitor disease activity suggesting interpretation of FDG-PET is less reliable once immunosuppressive therapy was initiated and reporting persistence of FDG uptake in absence of clinically active disease.30,31

Figure 3:

CDUS of a TAB specimen demonstrating classical hypoechoic halo sign of GCA (arrows). (Left) Cross sectional view. (Right) Longitudinal view. From “The impact of temporal artery biopsy on surgical practice” by A. Cristaudo 2016 with permission.63

Furthermore, the use of ophthalmic imaging modalities such as fluorescein angiography (FA), optical coherence tomographic angiography (OCT-A), and laser speckle fluoroscopy (LSFS) can also aid in the diagnosis of GCA. The use of FA can visualize the retinal vasculature, which has shown to be useful in diagnosing GCA in addition to imaging the temporal artery. On FA, choroidal filling delay is an established sign of GCA due to the thrombosis that occurs in the PCA, which is more proximal to the choroidal vasculature.15,32 It has been shown that the choroidal filling time was delayed by approximately one minute in a biopsy-confirmed GCA group compared to a non-arteritic AION group.33 The OCT-A imaging technique is another modality that can be utilized to visualize the microcirculation of the retina and choroid, which allows for the isolation of vascular pathology and individual analysis of each vascular plexus.34 OCT-A has proven useful in diagnosing and monitoring choroidal ischemic pathologies.35 LSFS is another scanning modality that can help diagnose GCA by quantifying the relative changes in blood flow. It was initially created to measure blood flow within the retina and now is a technique commonly used in research of systemic conditions that affect microcirculation such as diabetes, ischemic stroke, peripheral artery disease, and coronary artery disease.36,37 There are currently no studies in the literature investigating the utilization of OCT-A and LSFS in the diagnosis of GCA, but these imaging modalities can be a promising tool given their ability to diagnose choroidal ischemia, which is a known ocular manifestation of GCA.

Despite the various imaging modalities available to assist in the diagnosis of GCA, TAB remains the gold standard. On histology, a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate can be seen within the arterial wall with destruction of the internal elastic lamina.38 This test yields a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 100%; however, it is not a mandatory criteria as outlined by the American College of Rhuematology.3,39 There have also been instances of false-negative biopsies as there can be inactive areas of arteritis on the temporal artery or the sample length acquired during biopsy was too small.40 Prior studies have shown that corticosteroid treatment has limited effects on TAB results.41,42 It is important to initiate treatment of high-dose corticosteroids when GCA is suspected as the risk of irreversible vision loss is far more detrimental to the patient.

Treatment and Management

The initial treatment for GCA consists of high dose oral or intravenous corticosteroids. Corticosteroids often result in early improvement within hours to days of initiating treatment and have demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of permanent visual loss by up to 80%.43 The dosing recommendation vary widely in prior literature with higher doses reserved for patients with neuroophthalmological symptoms of GCA.44 When comparing the differences between oral or intravenous corticosteroids, visual improvement was seen in both groups with no significant differences, but early treatment is the most important prognostic factor to prevent further visual loss.7,45 However, according to the EULAR recommendations for the management of GCA, it is best to use high dose intravenous pulse methylprednisolone for three days prior to switching to oral formulations in order to preserve vision in the contralateral eye.46 Small retrospective cohort studies have demonstrated the superiority of utilizing high dose intravenous glucocorticoids to prevent visual involvement in contralateral eyes, but the recommendations remain controversial.47,48 Additional prospective studies are necessary to determine the use of oral compared to intravenous corticosteroids for GCA with visual involvement.

Additional forms of management include immunomodulators that are steroid sparing such as tocilizumab. Tocilizumab is a recombinant antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor with immunosuppressant activity. Studies have demonstrated that tocilizumab used as monotherapy or in association with glucocorticoids can be clinically beneficial49,50; however, additional studies are needed to standardize treatment guidelines. Methotrexate, for example, is another immunomodulator that can reduce relapses and the need for glucocorticoids for treatment.51 No other disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs have been tested extensively in clinical trials for the use of GCA to date.

To effectively manage GCA, it is essential to have a multidisciplinary team consisting of rheumatologists, radiologist, and ophthalmologists. Rheumatologists have extensive experience in managing systemic inflammatory conditions and overall corticosteroid regimen by monitoring for systemic side effects. Radiologists play an integral role in the diagnosis of GCA as imaging studies can have significant positive predictive diagnostic value. Ophthalmologists directly evaluate ocular manifestations of GCA by monitoring the response of visual symptoms to corticosteroid treatment and identify associated ocular complications such as cataracts or steroid-induced glaucoma. Multidisciplinary collaboration maximizes the probability of early detection and treatment, which is crucial to prevent impairment of vision. Since GCA is a chronic condition with potential for relapse, multidisciplinary management is the most effective holistic approach to the patient’s health.

Treatment response and detection of recurrent disease

Relapses can frequently occur within the first year during the corticosteroid taper affecting up to 50% of patients.52 Major relapses are defined as reactivation that may lead to another ischemic event resulting in ophthalmologic damage, jaw claudication, or scalp necrosis; however, patients can also experience mild clinical symptoms in the form of minor relapse.3 A study revealed normal ESR and CRP values in patients who experience relapses, raising concern about a lack of reliable prognostic markers available to monitor the disease.53 Though corticosteroids have significant benefits in the treatment of GCA, their significant side effects are such that it is critical for clinicians to find the right balance in the delivery of treatment. Adverse effects of steroids are often dose-dependent and duration-dependent with some common adverse effects including osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome, infections, and even adrenal insufficiency.54

Biomarkers for disease status and treatment response monitoring

There are limitations to the use of PET-CT to monitor GCA. Currently, studies are underway to address the lack of accurate blood biomarkers of GCA, necessitating the assessment of all inflammatory markers for the diagnostic workup. A highly specific biomarker could improve diagnostic accuracy, patient management, and even reduce or obviate the need for a temporal artery biopsy. Several categories of biomarkers are being investigated in the diagnosis of GCA. Currently, CRP, ESR, leukocytes, and platelets are being utilized to help with risk stratification for GCA diagnosis, but there is only moderate agreement between the values.55 Biomarkers involved in inflammation, vascular involvement, macrophage involvement, extracellular remodeling, lymphocyte activation, and cell migration can be indicative of inflammation processes that are specific for GCA.56 Some of these biomarkers could possibly play a role in monitoring disease status and/or treatment response in the future.

Biomarkers may also be predictive of complications or treatment options for GCA. A higher ESR at diagnosis has been linked to a smaller risk of large vessel stenosis.57 It has been postulated that CRP and ESR levels may not be an accurate way to measure the severity of GCA since some patients can present with normal levels.56 When evaluating the risk for complications, one study found that GCA patients with ischemic complications had lower IL-6 levels both in serum and in the temporal artery at diagnosis compared to patients who had no complications.58 The loss of self-tolerance in the adaptive immune system, specifically in the NOTCH pathway has demonstrated to be an immunosuppressive pathogenesis of GCA.59 Another study has shown that the loss of function in inhibitory immune checkpoints CD155-CD96 can contribute to aberrant activation of IL-9 production also contributing to GCA.60 The GM-CSF signaling cascade is another pathway that plays an vital role in GCA, which is currently being investigated as a target for pharmacotherapy.61 All these checkpoint inhibitors and signaling pathways are integral in the prevention and development of therapeutic management for autoimmune diseases like GCA. Treatment response can ultimately be difficult to monitor as there are currently no well-studied biomarkers that can accurately determine severity. Additional studies will need to evaluate these newly discovered biomarkers in GCA and their specific role in ocular involvement.

Summary

GCA can have a highly variable clinical presentation, which can cause difficulties and delays in reaching the diagnosis. Patients who are not diagnosed in a timely manner may experience ocular manifestations that could possibly result in permanent unilateral or bilateral vision loss. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are crucial in GCA as any form of delayed treatment can have dire consequences to a patient’s visual prognosis. Currently, there are limited studies evaluating the visual outcomes and ophthalmic manifestations in patients with GCA. No standardized guidelines have been developed to determine the best strategy in detecting visual relapse. There also appears to be continued debate on treatment modality, treatment duration, and the role of maintenance therapy. We anticipate that the discovery of additional ophthalmic biomarkers will aid in better earlier recognition of GCA and decrease the incidence of vision loss

Key Points:

Jaw claudication is a hallmark of GCA and plays a critical role in its diagnosis.

Ocular involvement in GCA can result in irreversible vision loss; prompt treatment is essential to preserve vision.

Early administration of intravenous corticosteroids is crucial for managing ocular involvement in GCA.

Synopsis:

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a large-vessel vasculitis that can present with ocular manifestation and lead to irreversible blindness if left untreated. Initially, patients can present with a wide array of systemic symptoms and ophthalmic manifestations varying from jaw claudication to amaurosis fugax. The use of ancillary ophthalmic imaging can be promising in aiding the diagnosis of GCA. Accurate and early diagnosis of GCA is critical in guiding prompt treatment with corticosteroids to preserve vision. Studies are currently underway to determine the best treatment regimen for GCA to prevent relapse and vision loss.

Abbreviations:

- GCA

giant cell arteritis

- TAB

temporal artery biopsy

- A-AION

arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy

- A-PION

arteritic posterior ischemic optic neuropathy

- ESR

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CDUS

color doppler ultrasound

- MRA

magnetic resonance angiography

- CTA

computed tomographic angiography

- PET-CT

positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- FA

fluoresceine angiography

- OCT-A

optical coherence tomographic Angiography

- LSFS

laser speckle fluoroscopy

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement:

The Authors have nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Li KJ, Semenov D, Turk M, Pope J. A meta-analysis of the epidemiology of giant cell arteritis across time and space. Arthritis Res Ther. Mar 11 2021;23(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02450-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Dairi MA, Chang L, Proia AD, Cummings TJ, Stinnett SS, Bhatti MT. Diagnostic Algorithm for Patients With Suspected Giant Cell Arteritis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2015;35(3):246–253. doi: 10.1097/wno.0000000000000234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponte C, Grayson PC, Robson JC, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/EULAR classification criteria for giant cell arteritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2022;81(12):1647–1653. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilton EJ, Mollan SP. Giant cell arteritis: reviewing the advancing diagnostics and management. Eye. 2023/08/01 2023;37(12):2365–2373. doi: 10.1038/s41433-023-02433-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponte C, Rodrigues AF, O’Neill L, Luqmani RA. Giant cell arteritis: Current treatment and management. World J Clin Cases. Jun 16 2015;3(6):484–94. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i6.484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liozon E, Herrmann F, Ly K, et al. Risk factors for visual loss in giant cell (temporal) arteritis: a prospective study of 174 patients. Am J Med. Aug 15 2001;111(3):211–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00770-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B, Kardon RH. Visual improvement with corticosteroid therapy in giant cell arteritis. Report of a large study and review of literature. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2002;80(4):355–367. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol. Apr 1998;125(4):509–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80192-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagener HP, Hollenhorst RW. The ocular lesions of temporal arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol. May 1958;45(5):617–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Gay MA, García-Porrúa C, Llorca J, et al. Visual manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Trends and clinical spectrum in 161 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). Sep 2000;79(5):283–92. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200009000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issa M, Donaldson L, Margolin E. Incidence of giant cell arteritis mimicking non-arteritic anterior optic neuropathy. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2023/06/15/ 2023;449:120661. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2023.120661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayreh SS. Giant cell arteritis: Its ophthalmic manifestations. Indian J Ophthalmol. Feb 2021;69(2):227–235. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1681_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi JH, Shin JH, Jung JH. Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Associated with Giant-Cell Arteritis in Korean Patients: A Retrospective Single-Center Analysis and Review of the Literature. J Clin Neurol. Jul 2019;15(3):386–392. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2019.15.3.386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu A, Moussa K, Zeng T, Liu YA. Giant Cell Arteritis with Choroidal Infarction. [NOVEL] PPT. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6wzk46r [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casella AMB, Mansour AM, Ec S, et al. Choroidal ischemia as one cardinal sign in giant cell arteritis. International Journal of Retina and Vitreous. 2022/09/24 2022;8(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s40942-022-00422-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schobel GA, Schmidbauer M, Millesi W, Undt G. Posterior ischemic optic neuropathy following bilateral radical neck dissection. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1995/08/01/ 1995;24(4):283–287. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(95)80030-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Occult giant cell arteritis: ocular manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol. Apr 1998;125(4):521–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80193-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizzo C, Kilian R, Savastano MC, Fossataro C, Savastano A, Rizzo S. A case of cilioretinal artery occlusion: Diagnostic procedures. American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports. 2023/12/01/ 2023;32:101949. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2023.101949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasimov M, Popovic MM, Micieli JA. Cilioretinal Sparing Central Retinal Artery Occlusion from Giant Cell Arteritis. Case Reports in Ophthalmology. 2022;13(1):23–27. doi: 10.1159/000521679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayreh SS. Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy Differentiation of arteritic from non-arteritic type and its management. Eye. 1990/01/01 1990;4(1):25–41. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Raman R, Zimmerman B. Giant cell arteritis: validity and reliability of various diagnostic criteria. Am J Ophthalmol. Mar 1997;123(3):285–96. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70123-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger CT, Sommer G, Aschwanden M, Staub D, Rottenburger C, Daikeler T. The clinical benefit of imaging in the diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis. Swiss Med Wkly. Aug 13 2018;148:w14661. doi: 10.4414/smw.2018.14661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang N, Qiao Y, Wasserman BA. Essentials for Interpreting Intracranial Vessel Wall MRI Results: State of the Art. Radiology. 2021;300(3):492–505. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021204096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guggenberger KV, Vogt ML, Song JW, et al. Intraorbital findings in giant cell arteritis on black blood MRI. Eur Radiol. Apr 2023;33(4):2529–2535. doi: 10.1007/s00330-022-09256-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seitz L, Bucher S, Bütikofer L, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: a comparison with T1-weighted black-blood imaging. Rheumatology. 2023;63(5):1403–1410. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lecler A, Hage R, Charbonneau F, et al. Validation of a multimodal algorithm for diagnosing giant cell arteritis with imaging. Diagn Interv Imaging. Feb 2022;103(2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2021.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn KA, Ahlman MA, Alessi HD, et al. Association of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose–Positron Emission Tomography Activity With Angiographic Progression of Disease in Large Vessel Vasculitis. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2023;75(1):98–107. doi: 10.1002/art.42290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vitiello G, Orsi Battaglini C, Carli G, et al. Tocilizumab in Giant Cell Arteritis: A Real-Life Retrospective Study. Angiology. Oct 2018;69(9):763–769. doi: 10.1177/0003319717753223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn KA, Dashora H, Novakovich E, Ahlman MA, Grayson PC. Use of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to monitor tocilizumab effect on vascular inflammation in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology. 2021;60(9):4384–4389. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narváez J, Estrada P, Vidal-Montal P, et al. Usefulness of 18F-FDG PET-CT for assessing large-vessel involvement in patients with suspected giant cell arteritis and negative temporal artery biopsy. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2024/01/04 2024;26(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13075-023-03254-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen AW, Hansen IT, Nielsen BD, et al. The effect of prednisolone and a short-term prednisolone discontinuation for the diagnostic accuracy of FDG-PET/CT in polymyalgia rheumatica—a prospective study of 101 patients. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2024/07/01 2024;51(9):2614–2624. doi: 10.1007/s00259-024-06697-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bei L, Lee I, Lee MS, Van Stavern GP, McClelland CM. Acute vision loss and choroidal filling delay in the absence of giant-cell arteritis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1573–1578. doi: 10.2147/opth.S112196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mack HG, O’Day J, Currie JN. Delayed choroidal perfusion in giant cell arteritis. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. Dec 1991;11(4):221–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koutsiaris AG, Batis V, Liakopoulou G, Tachmitzi SV, Detorakis ET, Tsironi EE. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography (OCTA) of the eye: A review on basic principles, advantages, disadvantages and device specifications. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2023;83(3):247–271. doi: 10.3233/ch-221634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Özdal P, Tugal-Tutkun I. Choroidal involvement in systemic vasculitis: a systematic review. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. Apr 4 2022;12(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12348-022-00292-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li D-Y, Xia Q, Yu T-T, Zhu J-T, Zhu D. Transmissive-detected laser speckle contrast imaging for blood flow monitoring in thick tissue: from Monte Carlo simulation to experimental demonstration. Light: Science & Applications. 2021/12/03 2021;10(1):241. doi: 10.1038/s41377-021-00682-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srienc AI, Kurth-Nelson ZL, Newman EA. Imaging retinal blood flow with laser speckle flowmetry. Front Neuroenergetics. 2010;2 doi: 10.3389/fnene.2010.00128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabian M, Walker M. Histological interpretation of temporal artery biopsies. Diagnostic Histopathology. 2022/09/01/ 2022;28(9):399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.mpdhp.2022.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luqmani R, Lee E, Singh S, et al. The Role of Ultrasound Compared to Biopsy of Temporal Arteries in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis (TABUL): a diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness study. Health Technol Assess. Nov 2016;20(90):1–238. doi: 10.3310/hta20900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poller DN, van Wyk Q, Jeffrey MJ. The importance of skip lesions in temporal arteritis. J Clin Pathol. Feb 2000;53(2):137–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.2.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narváez J, Bernad B, Roig-Vilaseca D, et al. Influence of previous corticosteroid therapy on temporal artery biopsy yield in giant cell arteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. Aug 2007;37(1):13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Achkar AA, Lie JT, Hunder GG, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. How does previous corticosteroid treatment affect the biopsy findings in giant cell (temporal) arteritis? Ann Intern Med. Jun 15 1994;120(12):987–92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffman GS. Giant Cell Arteritis. Ann Intern Med. Nov 1 2016;165(9):Itc65–itc80. doi: 10.7326/aitc201611010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B. Management of giant cell arteritis. Our 27-year clinical study: new light on old controversies. Ophthalmologica. Jul-Aug 2003;217(4):239–59. doi: 10.1159/000070631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.González-Gay MA, Blanco R, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Permanent visual loss and cerebrovascular accidents in giant cell arteritis: predictors and response to treatment. Arthritis Rheum. Aug 1998;41(8):1497–504. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hellmich B, Agueda A, Monti S, et al. 2018 Update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of large vessel vasculitis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2020;79(1):19–30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B. Visual deterioration in giant cell arteritis patients while on high doses of corticosteroid therapy. Ophthalmology. Jun 2003;110(6):1204–15. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(03)00228-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan CC, Paine M, O’Day J. Steroid management in giant cell arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol. Sep 2001;85(9):1061–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.9.1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muratore F, Marvisi C, Cassone G, et al. Treatment of giant cell arteritis with ultra-short glucocorticoids and tocilizumab: the role of imaging in a prospective observational study. Rheumatology (Oxford). Jan 4 2024;63(1):64–71. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Higashida-Konishi M, Akiyama M, Shimada T, et al. Giant cell arteritis successfully treated with subcutaneous tocilizumab monotherapy. Rheumatol Int. Mar 2023;43(3):545–549. doi: 10.1007/s00296-022-05217-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahr AD, Jover JA, Spiera RF, et al. Adjunctive methotrexate for treatment of giant cell arteritis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. Aug 2007;56(8):2789–97. doi: 10.1002/art.22754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lozachmeur N, Dumont A, Deshayes S, et al. Frequency and characteristics of severe relapses in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology. 2024;doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keae174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kermani TA, Warrington KJ, Cuthbertson D, et al. Disease Relapses among Patients with Giant Cell Arteritis: A Prospective, Longitudinal Cohort Study. J Rheumatol. Jul 2015;42(7):1213–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buttgereit F, Matteson EL, Dejaco C, Dasgupta B. Prevention of glucocorticoid morbidity in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology. 2018;57(suppl_2):ii11–ii21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan FLY, Lester S, Whittle SL, Hill CL. The utility of ESR, CRP and platelets in the diagnosis of GCA. BMC Rheumatology. 2019/04/10 2019;3(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s41927-019-0061-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carvajal Alegria G, Nicolas M, van Sleen Y. Biomarkers in the era of targeted therapy in giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: is it possible to replace acute-phase reactants? Front Immunol. 2023;14:1202160. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1202160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salvarani C, Cimino L, Macchioni P, et al. Risk factors for visual loss in an Italian population-based cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. Apr 15 2005;53(2):293–7. doi: 10.1002/art.21075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hernández-Rodríguez J, Segarra M, Vilardell C, et al. Elevated Production of Interleukin-6 Is Associated With a Lower Incidence of Disease-Related Ischemic Events in Patients With Giant-Cell Arteritis. Circulation. 2003;107(19):2428–2434. doi:doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066907.83923.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Immunology of Giant Cell Arteritis. Circ Res. Jan 20 2023;132(2):238–250. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.122.322128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohtsuki S, Wang C, Watanabe R, et al. Deficiency of the CD155-CD96 immune checkpoint controls IL-9 production in giant cell arteritis. Cell Rep Med. Apr 18 2023;4(4):101012. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esen I, Jiemy WF, van Sleen Y, et al. Functionally Heterogenous Macrophage Subsets in the Pathogenesis of Giant Cell Arteritis: Novel Targets for Disease Monitoring and Treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021;10(21):4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mac Grory B, Schrag M, Biousse V, et al. Management of Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Stroke. Jun 2021;52(6):e282–e294. doi: 10.1161/str.0000000000000366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cristaudo AT, Mizumoto R, Hendahewa R. The impact of temporal artery biopsy on surgical practice. Ann Med Surg (Lond). Nov 2016;11:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dumont A, Lecannuet A, Boutemy J, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with ophthalmologic involvement in giant-cell arteritis: A case-control study. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2020/04/01/ 2020;50(2):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen Q, Chen W, Feng C, et al. Giant Cell Arteritis Presenting With Ocular Symptoms: Clinical Characteristics and Multimodal Imaging in a Chinese Case Series. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:885463. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.885463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Héron E, Sedira N, Dahia O, Jamart C. Ocular Complications of Giant Cell Arteritis: An Acute Therapeutic Emergency. J Clin Med. Apr 2 2022;11(7)doi: 10.3390/jcm11071997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Portela MG, Correia MR, Baptista ML, Bruxelas CP, Pinto D, Costa JM. Giant cell arteritis: Is there a link between ocular and systemic involvement? The Pan-American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2023;5(1):3. doi: 10.4103/pajo.pajo_65_22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dentel A, Clavel G, Savatovsky J, et al. Use of Retinal Angiography and MRI in the Diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis With Early Ophthalmic Manifestations. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2022;42(2):218–225. doi: 10.1097/wno.0000000000001517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]