SUMMARY

In humans, selective and promiscuous interactions between 46 secreted chemokine ligands and 23 cell surface chemokine receptors of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family form a complex network to coordinate cell migration. While chemokines and their GPCRs each share common structural scaffolds, the molecular principles driving selectivity and promiscuity remain elusive. Here, we identify conserved, semi-conserved, and variable determinants (i.e., recognition elements) that are encoded and decoded by chemokines and their receptors to mediate interactions. Selectivity and promiscuity emerge from an ensemble of generalized (“public/conserved”) and specific (“private/variable”) determinants distributed among structured and unstructured protein regions, with ligands and receptors recognizing these determinants combinatorially. We employ these principles to engineer a viral chemokine with altered GPCR coupling preferences and provide a web resource to facilitate sequence-structure-function studies and protein design efforts for developing immuno-therapeutics and cell therapies.

In brief

Sequence and structure-based analysis highlight the molecular principles driving chemokine-GPCR selectivity and promiscuity, enabling the design of chemokines with altered receptor preferences.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

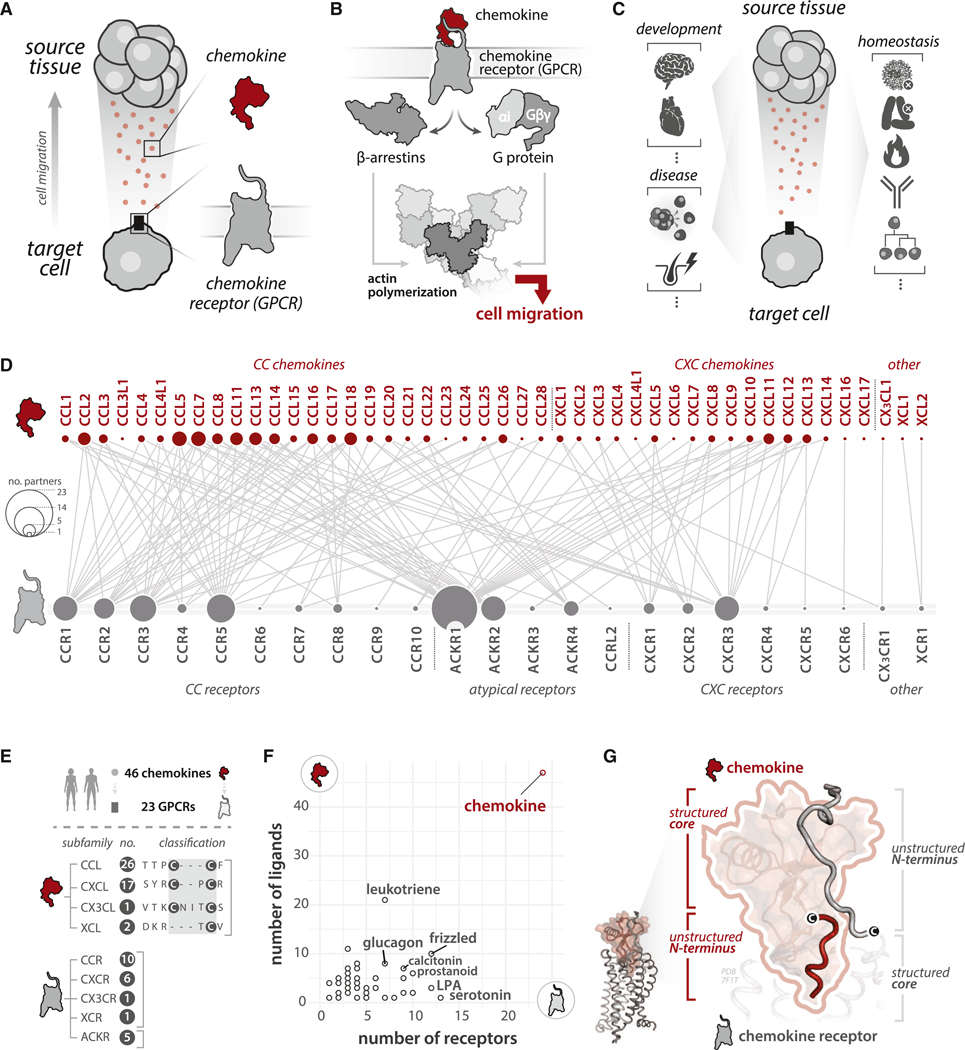

In humans, cell migration is coordinated by interactions between secreted chemokine ligands and their chemokine receptors of the G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) superfamily that are expressed on the surface of the migrating cell (Figure 1A). Chemokine-GPCR interactions initiate signaling cascades through G protein1,2 and β-arrestin3 pathways, resulting in directed migration of the target cell along a chemokine gradient (Figure 1B). In this manner, a combination of chemokines secreted by diverse cell types is interpreted by receptors on receiving cells to coordinate a vast cell migration system throughout the body. This ligand-receptor system forms the molecular basis for cell migration in developmental and homeostatic processes, including cerebellar development,4,5 gastrointestinal vascularization,6 coronary artery development,7 hematopoiesis,8,9 and immunity10,11 (Figure 1C). This system is exploited in disease processes including cancer metastasis,12–15 autoimmune diseases,16 bleeding disorders,17 COVID-19 pathogenicity,18–20 HIV infection,21,22 and viral immune evasion23 (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Structural and functional organization of the chemokine-GPCR system.

(A) Secreted chemokines are sensed by receptors on migrating cells.

(B) Chemokine binding to GPCRs activates G protein and β-arrestin signaling/recruitment, resulting in cell migration.

(C) The chemokine-GPCR system underlies development and immune regulation and is exploited in disease.

(D) Interaction network between chemokine ligands (top) and receptors (bottom) (compiled from Table S1; interaction strength ≥ 2 represented, see STAR Methods). Node size scaled to number of binding partners.

(E) Chemokine ligand (red) and receptor (gray) subfamilies.

(F) The number of GPCR ligands and receptors grouped by family (STAR Methods).

(G) Reciprocal structured-to-unstructured binding mode (PDB: 7F1T). The receptor’s unstructured N terminus interacts with the chemokine’s structured core, and vice versa.

See also Figure S1.

The diverse roles of the chemokine-GPCR system are enabled by a complex network of interactions among 46 chemokine ligands and 23 receptors (Figures 1D and 1E), which together comprise the most abundant genetically encoded ligand-receptor system among the GPCR superfamily (Figure 1F). A comprehensive literature survey allowed us to construct a network >100 experimentally validated chemokine-GPCR interactions highlighting selective (i.e., non-overlapping) and promiscuous (i.e., overlapping) interactions in the network (Figure 1E; Figure S1; Table S1). Spatial (e.g., cell- and tissue-specific) and temporal regulation of chemokine and GPCR expression patterns further enable this system to coordinate an extensive cell migration network throughout the body with remarkable precision. In effect, chemokines function as molecular signposts, controlling the flow of cellular traffic throughout the body via selective GPCR interactions.

Despite its complexity, this system is constructed using conserved chemokine and GPCR structural folds that interact in a prescribed manner24: the receptor’s unstructured N terminus interacts with the chemokine’s structured core and vice versa (Figure 1G). More than a dozen chemokine-GPCR complex structures have demonstrated this reciprocal structured-to-unstructured pairing. Within this framework, additional mechanisms allow chemokines and GPCRs to interact with some binding partners and not others. Uncovering the determinants and how they are encoded can reveal the molecular basis of selectivity and promiscuity in this critical ligand-receptor system and accelerate design of chemokine-based therapeutics.

In this study, we develop a data science framework, integrating diverse data types to uncover molecular principles governing the emergence of a complex interaction network from two highly conserved protein architectures. We used the identified patterns to engineer chemokine mutants with altered receptor binding profiles, providing evidence that these principles can be leveraged to design selective chemokine-GPCR interactions. Finally, we present sequence conservation, genome variation, and disease mutation data, and literature-validated chemokine-GPCR interactions in a comprehensive online resource for the scientific community (https://andrewbkleist.github.io/chemokine_gpcr_encoding/).

RESULTS

Common numbering and sequence alignments

Functionally important residues can be identified by analyzing structurally equivalent positions from protein sequence alignments.25 We identified 46 human chemokine paralogs and their respective one-to-one orthologs from over 60 species (STAR Methods) to construct a master alignment of 1,058 sequences. Using this alignment and 35 available chemokine structures, we devised a common chemokine numbering (CCN) system to annotate structurally equivalent positions for all members of the chemokine family (Figures S2A–S2C). Each position is defined by two attributes (SSE.P): SSE refers to the consensus secondary structure element (SSE) that we defined using the available structures (Figure S2B), and P refers to the position (P) within the consensus SSE. For instance, the last of the four conserved cysteines, residue 50 in CXCL12 and residue 48 in CCL2, are denoted as B3.3 (third position in the third b strand) (Figure S2A). Loops are denoted in lowercase by the SSEs they connect; thus, b1b2.1 refers to the first position in the loop connecting β1 and β2 strands.

We implemented the same approach for chemokine GPCRs, by constructing an alignment of 951 chemokine-receptor sequences, including all 23 human paralogs and one-to-one orthologs from over 60 species (STAR Methods). Structurally equivalent sequence position names were mapped using a modified version of the GPCR database (GPCRdb) numbering system,26 termed chemokine-receptor numbering (CRN, STAR Methods), which considers a conserved N-terminal cysteine among chemokine GPCRs.27

Using CCN and CRN alignments (Figure S2C), we calculated sequence conservation scores for every chemokine and GPCR position among (1) human chemokine and receptor paralogs, i.e., conservation among different (paralogous) chemokines/GPCRs within the same species (humans); and (2) chemokine and receptor orthologs, i.e., conservation of the equivalent (orthologous) chemokine/GPCR among different species (STAR Methods). Only conventional (i.e., non-atypical) chemokine receptors were used to score paralog conservation.

Constrained plasticity in chemokine-receptor-binding mode is mediated by a minimal network of conserved residues

We gathered 14 published chemokine-GPCR complex structures and two validated models available at the time28–41 and assigned CCN and CRN for the residues within each complex (Figure S3A). Despite high structural similarity of chemokines and their GPCRs, we observed a range in the orientation of chemokine-GPCR complexes, with some pairwise root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values varying from 17 to <1 Å (Figure S3B). We used paired GPCR coordinates to perform pairwise structural alignments of all complexes, then calculated pairwise Cα RMSD values for structurally equivalent chemokine positions. While some chemokine regions exhibit a high degree of structural plasticity, others are more constrained, with a mean RMSD of ~5 Å or less, with low-RMSD positions occurring at or near disulfide-bonded cysteines (Figure S3C).

The preserved positioning of some structural elements suggests that broadly preserved molecular contacts may constrain chemokine-GPCR interactions. We use the term “preservation” to refer to the degree of variability of features among different sets of chemokine-GPCR structures (and in contrast to “conservation,” which we use to refer to variability among sets of sequences). To identify those contacts, we calculated all non-covalent, intermolecular residue-residue contacts for all 16 complexes (Figure 2A; Figure S3D).42 We identified 953 total contacts, 442 of which occurred between unique pairs of chemokine and GPCR positions (Figure 2B). Mapping paralog conservation scores to intermolecular chemokine-GPCR contacts (Figure 2C) revealed only 5 contacts were formed between conserved chemokine and GPCR residues (Figure 2D), with at least one such contact being present in a majority of complexes (12/16).

Figure 2. Minimal encoding of generalized chemokine-GPCR recognition.

(A) Residue-residue contacts for 16 chemokine-GPCR complexes.

(B) Contact fingerprint representing all unique contacts (rows) and complexes (columns). Example fingerprint shown with black/white denoting presence/absence of contact between equivalent residues. * denotes two models used.

(C) Human paralog alignments were used to calculate paralog conservation scores, with CCN example given for position B2.3.

(D) Residue-residue contacts among 16 chemokine-GPCR complexes (points), and human paralog conservation scores of chemokine (y axis) and receptor (x axis) residues comprising each contact. Receptor paralog scores are calculated among non-atypical receptors (STAR Methods).

(E) 12/16 complexes have ≥1 contact between conserved chemokine/receptor residues (human paralogs) involving disulfide regions. Paralog conservation scores shown as pie charts.

(F) Interactions between paralog conserved residues by analogy to Lego bricks.

(G) Contacts between conserved (human paralogs) chemokine and GPCR residues (dark gray) are 3% of overall contacts. Contacts involving ≥1 variable residue are 97% of contacts (light blue).

(H) Effects of CXCR4 mutagenesis on CXCL12 binding. Log2 enrichment scores reflect CXCL12-GFP binding to cells harboring WT versus mutated CXCR4 (STAR Methods). Statistical testing by Kruskal-Wallis test with p values determined by post hoc Dunn test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. *p value < 0.05, ***p value < 0.001, ****p value < 0.0001. p values for all other pairwise comparisons > 0.05. Boxplot boxes reflect the median (central line), first and third quartiles (box boundaries), and largest/smallest values no further than 1.5x the interquartile range (whiskers). Raw data from Heredia et al.43

See also Figures S2 and S3.

Among the 5 conserved chemokine and GPCR residues participating in these contacts, all but one participate in or are adjacent to a disulfide bond (Figure 2E). Given the essential functional role of receptor transmembrane domain (TM)1–TM7 disulfides,44 it is likely that the interactions between conserved, disulfide-rich regions in the respective binding partners facilitate the selection of their cognate chemokine receptors from other class A GPCRs; most of which lack a TM1–TM7 disulfide.27 In effect, chemokine disulfides are repurposed for molecular recognition of cognate chemokine GPCRs, thereby maximizing the functional utility of a minimal set of residues. Notably, none of the generalized recognition contacts are structurally preserved among all complexes despite the constituent residues being highly conserved in sequence. Instead of using a single, structurally preserved constraint, chemokine-GPCR interactions employ a series of soft constraints that can be mixed and matched along different registers, allowing pair-specific local rearrangements. This is analogous to two Lego bricks that can be connected to one another in different registers using conserved “knobs” and “holes” (Figure 2F). In turn, the degeneracy of these local constraints may facilitate the variation in chemokine orientation observed in chemokine-GPCR complexes.

We next assessed the extent to which these contacts contribute to the total interface. Pairwise contacts among paralog conserved residues account for only 3% of the total contacts, whereas the remaining contacts involve at least one poorly conserved residue (i.e., paralog conservation scores < 0.5; Figure 2G). These data reveal that generalized recognition between chemokine and GPCR binding partners is encoded at a single interface region using a minimal set of residues, thereby maximizing the surface area dedicated to pair-specific recognition elements.

How important are the residues comprising disulfide-rich hotspots in chemokine-GPCR binding? A recent study43 assessed the effects of CXCR4 mutations on CXCL12 binding via saturation mutagenesis (i.e., substitution of every possible amino acid at every position of CXCR4). Using this dataset, we compared the effects of CXCR4 mutations at conserved hotspot residues (Pro27NTr.Cm1, Cys281×22, and Cys2747x24) with those at other positions that are either (1) known to be important for CXCL12 binding (e.g., Asp2626x58; positive control) or (2) non-interface positions in the vicinity of the binding pocket that are likely to be unimportant for binding (e.g., Val1985x38; negative control; STAR Methods). Mutations of receptor residues involved in or adjacent to contacts among conserved chemokine- and GPCR residues (i.e., NTr.Cm1, 1×22, and 7×24) significantly reduce CXCL12 binding (Figure 2H), consistent with alanine mutagenesis studies of CCR8 (i.e., Cys25Ala1×22 or Cys272Ala7×24)44 and CXCR4 (Cys28Ser1×22 and Cys274Ser7×24).45

Semi-preserved molecular “sensors” guide subfamily-specific recognition

A majority of human chemokines belong to either CC (26 members) or CXC (17 members) subfamilies, named for the presence (i.e., CXC) or absence (i.e., CC) of a single residue (i.e., the “X” in CXC: CCN position CX.4) between the two conserved N-terminal cysteines (Figure 3A). This difference has significant functional consequences, as CC and CXC chemokines predominantly couple to CC or CXC receptors, respectively (Figure 3B). To identify whether positions other than the “X” might confer sub-family-specific recognition, we devised a logistic regression classification algorithm to evaluate the predictive accuracy of other CCN positions at discriminating a chemokine as belonging to CC or CXC subfamilies (Figure 3C, top; STAR Methods). Resulting “subfamily scores,” calculated for each CCN position, reflect the algorithm’s accuracy at predicting the identity (i.e., CC versus CXC) of an unknown sequence. As anticipated, the “X” residue (CCN: CX.4) was the most predictive of chemokine subfamily, but unexpectedly, we identified 34 other positions at the binding interface that are predictive with an accuracy ≥ 75% (Figure S4A). Subfamily-predictive positions were distributed across almost every chemokine SSE, suggesting that subfamily-specific differences are widespread beyond the “X” residue. Of note, residue conservation of subfamily-predictive positions among CC and CXC chemokines was variable, with some subfamily-predictive positions having high paralog conservation in either or both subfamilies (but different amino acids); whereas other subfamily-predictive positions showed low paralog conservation among CC and CXC subfamilies (Figure S4B). The latter positions are predictive despite low paralog conservation because CC and CXC chemokines employ different sets of amino acids even if no specific amino acid is dominant among either subfamily (Figure S4C).

Figure 3. Subfamily-specific sensors encode distinct chemokine-GPCR binding modes.

(A) CC and CXC chemokines differ by the presence (CXC) or absence (CC) of a residue (“X”) between conserved N-terminal cysteines.

(B) Predominance of interactions among like subfamily chemokines/GPCRs (chi-squared test p = 6.76e-11).

(C) Top: logistic regression models were trained to classify a sequence as CC or CXC by residue identity at each sequence position. Positions ranked according to accuracy in subfamily prediction (STAR Methods). Bottom: CC and CXC complexes used to identify consensus subfamily contacts. Contacts in CCL5:CCR5 complexes were considered degenerate (STAR Methods).

(D) Residue-residue contacts among CC and CXC complexes (points), with subfamily-predictive scores of chemokine (y axis) and receptor (x axis) positions comprising each contact.

(E) Consensus, CC- and CXC-specific contacts involving subfamily-predictive positions.

(F) CC- and CXC-specific consensus contacts from (E), with residue positions (chemokine: red, receptor: gray) represented as pie charts depicting position-specific subfamily scores.

(G) CC- and CXC-specific consensus contact (top) with subfamily scores and residue sequence logos (middle). CC and CXC complexes (bottom) with puzzle pieces depicting how the same chemokine position (NTc.Cm3) uniquely accommodates CC versus CXC receptor residues (bottom).

(H) β-arrestin recruitment by NanoLuc Binary Technology (NanoBiT) with CCR5 (top 3 panels; versus CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5) and CXCR4 (bottom panel; versus CXCL12) receptor mutants at positions 1×24 and 6×58. All experiments n = 3. Error bars reflect SEM. See Table S2.

See also Figure S4.

While chemokine subfamilies are classified by the presence or absence of a residue between two N-terminal cysteines, CC versus CXC receptor classification is based on the subfamily of ligands with which they primarily interact. To identify whether chemokine receptors possess subfamily discriminating positions, we applied the classifier approach to receptor alignments (Figure 3C, top; STAR Methods). We identified 29 CRN positions at the binding interface that were ≥75% accurate in discriminating CC versus CXC receptors (Figure S4A). Some subfamily-predictive positions were broadly conserved, while others displayed low paralog conservation among both subfamilies (Figure S4B). As with ligands, subfamily-predictive positions that have poor conservation among CC and CXC receptor paralogs employ different sets of amino acids among CC and CXC subfamilies (Figure S4C). These differences might enable receptors to customize the level of specificity and promiscuity among individual chemokine-GPCR pairs within a particular subfamily.

How often do subfamily-predictive positions interact with one another in chemokine-GPCR complexes? For all intermolecular residue contacts among complexes made of “like” CC or CXC ligand-receptor pairs (Figure 3C, bottom), we mapped subfamily scores for the chemokine and GPCR residues comprising each contact (Figure 3D). We identified 106 contacts between distinct pairs of chemokine and GPCR positions that have ≥75% accuracy at predicting the respective chemokine or GPCR subfamily. Of these, we identified those present in a majority of CC but not CXC complexes and vice versa (STAR Methods). We considered contacts between subfamily-predictive positions in one binding partner and conserved positions in the other since the subfamily-predictive positions could cause distinct, subfamily-specific modes of interaction with conserved residues. These analyses revealed 15 (CC) and 6 (CXC) contacts involving subfamily-specific residue positions found exclusively in chemokine-GPCR complexes of the respective subfamilies (Figures 3E and 3F).

Comparison of CC- and CXC-specific residue contact networks revealed that the same, conserved receptor position (Cys1×22) is contacted differently by CC and CXC chemokines. CC chemokines contact this residue using position NTc.Cm1, whereas CXC chemokines contact this residue using the “X” position CX.4, both of which are subfamily-predictive positions (Figures 3F and S4A). This subtle structural alteration may function to derivatize the conserved architecture to allow more pronounced differences in interactions in the binding pocket.39,46 In the receptor binding pocket, CC chemokines use position NTc.Cm3 to contact GPCR position 1×24, whereas CXC chemokines use NTc.Cm3 to contact 6×58 (Figure 3G). CC-subfamily GPCRs have a conserved positively charged Lys at position 1×24, whereas CXC subfamily GPCRs have a conserved negatively charged Asp at position 6×58. While the chemokine position NTc.Cm3 contacts these two GPCR positions in CC and CXC complexes, respectively, its residue identity is not strongly conserved among CC or CXC chemokines. Subfamily residues exhibit distinct identities, with ProNTc.Cm3 being predominantly represented among CC chemokines, and GluNTc.Cm3 being predominant represented among CXC chemokines (Figure 3G).

Together, these data suggest that subfamily specificity is enabled using reciprocal, subfamily-specific sensors on the chemokine and GPCR. To test this, we performed paired Ala mutagenesis of GPCR residues predicted to be important for CC versus CXC recognition using representative CC (i.e., CCR5) and CXC (i.e., CXCR4) receptors (Figure 3H; Table S2). At CCR5, Asn258Ala6x58 had negligible effects on β-arrestin recruitment compared with wild-type (WT) CCR5 in response to ligands CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5, whereas Lys26Ala1×24 caused near-complete loss of β-arrestin recruitment in response to all ligands even at high concentrations (Figure 3H). Conversely, at CXCR4, Asp262Ala6x58 resulted in a complete loss of β-arrestin recruitment in response to CXCL12, consistent with prior radioligand results,47 whereas Ala34Lys1×24 had no appreciable effect on β-arrestin recruitment compared with WT CXCR4. These data support a model in which chemokines and their GPCRs possess an intrinsic “handedness” that leads to differences in binding pocket targeting; this enables reciprocal recognition of subfamily-specific binding partners by employing subfamily-specific determinants.

Customization of selectivity preferences among chemokine-GPCR complexes

How do individual chemokines and GPCRs achieve selectivity preferences within their respective subfamilies? We hypothesized that chemokines and GPCRs specify selectivity preferences by customizing amino acid identities at key positions in the chemokine-GPCR interface (i.e., “sequence-level changes”) and/or customizing intermolecular residue contacts (i.e., “structure-level changes) (Figure 4A). To investigate this, we performed pairwise comparisons of sequence and structural similarities and differences at the chemokine-GPCR interface for all pairs of human complexes (Figure 4B). Complexes demonstrated a range of overlapping and distinct features, with the most similar complexes sharing 36% of residue contacts (e.g., CCL3-CCR5 and CCL5-CCR5) and 77% sequence identity (e.g., CXCL8-CXCR1 and CXCL8-CXCR2) of interface residues when averaged among paired chemokines and GPCRs (STAR Methods). The most different complexes shared no common residue contacts (e.g., CCL2-CCR2 and CXCL12-ACKR3), and only 15% sequence identity of interface residues (i.e., CCL20-CCR6 and CXCL12-CXCR4).

Figure 4. Customization of chemokine-GPCR interactions through structure- and sequence-level changes.

(A) Customization through structure-level (contact differences) and sequence-level (residue differences among structurally preserved contacts) changes.

(B) Comparison of the percent identical/equivalent contacts at the interface among all chemokine-GPCR complexes (y axis, related to structure-level changes) and mean pairwise percent identities of interface residues among paired chemokines and GPCRs (x axis, related to sequence-level changes). Points denote a comparison of a pair of chemokine-GPCR complexes; examples given for the three groups of selectivity-network relatedness.

(C) Generalized (i.e., distinguish chemokines/receptors from other molecules/GPCRs), subfamily (i.e., distinguish between chemokines/receptors of different subfamilies, CC or CXC), and network (i.e., found only within specific chemokine-receptor pairs that share interactions) recognition features.

(D) Positive selectivity features facilitate interactions, and negative selectivity features disfavor interactions at generalized, subfamily, and network “layers” of encoding.

(E) Positive selectivity example. 11 shared contacts among identical residues encode CXCL8 recognition by CXCR1 and CXCR2 (STAR Methods).

(F) Selectivity preferences are encoded using compact, discrete interface regions.

(G) Negative selectivity example. The contact cxb1.1–7×27 is preserved among 9/16 chemokine-GPCR complexes but has low paralog conservation (left). Unfavorable chemokine-GPCR interactions are likely to prevent noncognate chemokine-GPCR pairs.

See also Figure S5.

Next, we grouped each pair of complexes by whether constituent chemokines and GPCRs were (1) part of different subfamilies and had non-overlapping interaction networks (group 1), (2) in the same subfamily but had non-overlapping interaction networks (group 2), or (3) in the same subfamily and had overlapping interaction networks (group 3). Groupings reveal that chemokines or GPCRs sharing interaction networks (group 3) typically employ the highest degree of overlapping sequence and structural features to bind their respective partners. Conversely, chemokines or GPCRs with non-overlapping networks (groups 1 and 2) employ largely non-overlapping sets of sequence and residue contacts (Figure 4B). For instance, CCL3-CCR5 and CCL15-CCR1 complexes (group 3), which have highly overlapping selectivity networks (Figure S1B)—share 32% of contacts and 44% sequence identity at interface positions. Conversely, CCL15-CCR1 and CCL20-CCR6 complexes (group 2)—where neither chemokines (CCL20 and CCL15) nor receptors (CCR5 and CCR6) share any respective binding partners (Figure S1B)—share 15% of contacts and 20% sequence identity at interface positions. This observation suggests that when the chemokine or the receptor share interaction partners, this is mediated through similarity in sequence and structural features (i.e., residue contacts). However, when they do not share interaction partners, it may be driven by changes in sequence and structural features. This pattern among functionally related complexes suggests that selectivity determinants are hierarchically “layered” on top of one another where conserved (generalized), semi-conserved (subfamily-specific), and variable (network-specific) sequence and structural features may determine selective and promiscuous interactions in the chemokine-receptor system (Figure 4C).

We next hypothesized that the observed similarities and differences at each “layer” of selectivity encoding (i.e., generalized, subfamily, and network-specific) might allow chemokines and GPCRs to facilitate binding to some partners (“positive selectivity”) while disfavoring binding to other partners (“negative selectivity”; Figure 4D). To identify instances of positive selectivity, we focused on sequence and structural similarities between CXCL8-CXCR1 and CXCL8-CXCR2 complexes (Figure 4E), which feature the same chemokine bound to different receptors. Among the 61 total residue contacts, 11 (18%) are preserved between complexes and comprise identical chemokine and receptor residues (Figure 4E). This highlights how the conservation of a discrete set of positions among two moderately related receptors—sharing 54% sequence identity at interface positions—can allow them to recognize the same binding partner at a compact, discrete interface (Figure 4F). Analogous results are observed when comparing structures of two moderately related chemokines (i.e., CCL3 and CCL5: 43% sequence identity at interface positions) bound to the same receptor (i.e., CCR5; Figure S5A).

To identify instances of negative selectivity, we identified contacts that are found in a majority of complexes but are comprised chemokine and/or GPCR residues that are poorly conserved among paralogs (Figures S5B and S5C). Among these contacts, cxb1.1(chemokine)-7×27(receptor) displays poor paralog conservation but high ortholog conservation among members of chemokine and receptor families (Figure 4G; Figures S5C and S5D), suggesting that it may help encode chemokine- and GPCR-specific selectivity profiles. Indeed, paired interactions between CXCL12 and noncognate receptor CXCR2 would likely be energetically unfavorable because they would oppose two large, positive side chains in proximity (i.e., CXCL12 Arg12cxb1.1 and CXCR2 Arg2897x27) (Figure 4G). Likewise, paired interactions between CCL2/CCL3/CCL5 and noncognate receptors such as CCR4 or CCR6 are likely to be energetically unfavorable because they would oppose large, aromatic side chains (chemokine Phe/Tyrcxb1.1) with negatively charged Glu2797x27 of CCR4 or Glu2917x27 of CCR6. Thus, by convoluting multiple types of selectivity information (e.g., positive and negative design) into the chemokine-GPCR interface, chemokines and GPCRs can facilitate interactions with some partners while preventing interactions with others.

Densely packed selectivity hotspots in unstructured regions and loops

Where are the network-specific selectivity determinants located in chemokine and GPCR structures? Prior analysis (Figures 4E and 4F; Figure S5A) suggests that selectivity determinants are likely to be enriched among contacts that are (1) found in a small set of structures (i.e., structure-level changes) and (2) comprised residues that are poorly conserved among paralogs (i.e., sequence-level changes). We analyzed human chemokine-GPCR complexes and identified contacts that (1) have low structural preservation and (2) are formed by residues that are poorly conserved among paralogs (Figure S5E). Among chemokines, the N terminus demonstrates the highest degree of sequence- and structure-level changes, followed by the b1b2 and cxb1 loops (Figures S5E and S5F). Similarly, among GPCRs, the N terminus demonstrates the region with the highest degree of sequence- and structure-level changes, followed by ECL2 (Figure S5F). In the context of paired interactions among SSEs, most sequence- and structure-level changes involve the chemokine or GPCR N terminus or the GPCR ECL2 (Figure S5G). Consequently, sequence- and structure-level changes are driven by residues in chemokine and receptor N termini and loops, which are thus likely to serve as key regions encoding chemokine- and GPCR-network-specific selectivity preferences.

We next examined whether these regions contribute to chemokine-GPCR recognition using an independent dataset. We mapped saturation mutagenesis data for CXCR443 onto the experimentally guided CXCL12-CXCR4 model36 to identify interface regions that most likely encode CXCL12 selectivity. CXCR4 mutations with the largest impact on CXCL12 binding fell into three regions: (1) a three residue stretch in the CXCR4 N terminus (DYD motif; CXCR4 residues 20–22), (2) a set of 11 residues in TMs 1, 2, 3, and 7 and ECL2 that make contacts with a three residue stretch in the CXCL12 N terminus (KPV motif; CXCL12 residues 1–3) (Figure S5H), and (3) conserved receptor residues Cys261×22, Pro27NTr.Cm1, and Cys7x24 that anchor conserved chemokine-GPCR contacts described in the previous section (Figure 2; Figure 3). In effect, a significant proportion of the CXLC12-CXCR4 interaction is derived from two short residue stretches in chemokine and receptor N termini despite the extensive surface area of the interface. This suggests that a small subset of the chemokine-GPCR interface is responsible for network selectivity, and that selectivity information is enriched in unstructured regions that can be represented as a short linear motif (SLiM) (Figure 4F).

Identification of SLiMs

Short interaction interfaces in unstructured regions—termed SLiMs—mediate protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in various contexts, including protein complex assembly, subcellular trafficking, and enzymatic recruitment for post-translational modifications.48 We postulated that SLiMs in unstructured regions contribute to network-specific interactions. The same SLiM in different positions (within equivalent unstructured regions) of two paralogous proteins can serve the same function, making SLiM identification difficult because their sequences may not be alignable. We developed an alignment-free approach to infer short, functional, conserved sequence fragments in chemokine and receptor unstructured N termini and receptor ECL2 that might encode network-specific selectivity preferences (Figure 5A; STAR Methods).

Figure 5. Encoding interactions via SLiMs in unstructured regions.

(A) Enumeration of all 2-, 3-, and 4-mer fragments for unstructured regions (chemokine/GPCR N termini; GPCR ECL2) using a sliding window approach (STAR Methods).

(B) Inferring fragment functional roles based on ortholog/paralog conservation. Fragments conserved in ≥50% of orthologs are called putative SLiMs.

(C) CCL28 structure (PDB: 6CWS) depicting N-terminal residues 1–5 and fragment ortholog conservation.

(D) LogEC50 of CCL28 N-terminal truncation variants values from calcium flux experiments on CCR3 (left) and CCR10 (right) -expressing cells. Error reflects SEM of nonlinear fit of logEC50 value. All conditions n = 3. See Table S2.

(E) Most frequent variants in chemokines (left) and receptors (right) among interface positions from gnomAD.

(F) Allele frequency of ACKR1 Gly42 and Asp42. Gly42 allele frequency inferred as 1 Asp42 allele frequency.

(G) Log2-fold ratio of chemokine EC50 values for ACKR1 Asp42 versus Gly42 in bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-based binding assay (STAR Methods). See Table S2.

(H) ITC performed by injecting 200 μM ACKR1(1–60) Gly42 (left) and Asp42 (right) into WT-CXCL12. Thermograms representative of n = 2 replicates.

(I) Immune, functional, and phenotypic trade-offs between ACKR1 Gly42 and Asp42 alleles.

See also Figures S6 and S7.

For each sequence in our alignment, we enumerated every 2-mer, 3-mer, 4-mer, and gapped peptide fragment observed in chemokine N termini, receptor N termini, and receptor ECL2 (Figure S6A; STAR Methods). The resulting sequence fragments were then scored for their paralog conservation among other human chemokines and for their ortholog conservation for the same protein across species, agnostic of fragment positioning. Functional relevance of the resulting fragments can be inferred by comparing ortholog and paralog conservation (Figure 5B).25,49 For instance, sequence fragments that are conserved among orthologs and shared among multiple paralogs likely confer mutual chemokine recognition of a shared receptor. Fragments that are conserved among orthologs but not among paralogs likely confer a protein-specific function or unique recognition mode of a chemokine or receptor (Figure S6B). Since functionally relevant peptide fragments in either instance are likely to be conserved among chemokine orthologs from different species,48,50 we define putative SLiMs as peptide fragments with ortholog conservation ≥ 0.5. Relative conservation comparisons at this level help to prioritize fragments with the greatest impact on chemokine or GPCR function. We use the term fragments to refer to any 2–4 residue stretch regardless of conservation.

Among putative SLiMs, only 5% (chemokine N terminus), 12% (receptor N terminus), and 1% (receptor ECL2) were shared among five or more chemokines or receptors (Figures S6C and S6D). For instance, the tyrosine sulfation motif “DYG” was shared among 5 receptors N termini, and the CXCR1/2 recognition motif “ELR” was shared among 7 chemokines N termini (Figure S6B). In contrast, a majority of putative SLiMs in chemokine and receptor N termini (60% and 52%, respectively) and receptor ECL2 (70%) were unique to a single chemokine or receptor (Figure S6C).

To investigate how chemokine SLiMs influence receptor recognition, we characterized conservation of peptide fragments in the N terminus of CCL28 and tested the ability of CCL28 variants beginning with various peptide fragment to activate two different receptors: CCR3 and CCR10.51 All possible CCL28 N-terminal 3-mer peptides are found exclusively within CCL28 (Figure S6E), consistent with CCL28’s limited and distinct receptor repertoire (Figure S1B). While CCL28 N-terminal peptide fragments have low paralog conservation, they vary in ortholog conservation. The first two 3-mer fragments display an ortholog conservation score of ~0.50 (SEA conservation 0.46; EAI conservation 0.51), and the subsequent three peptide fragments (AIL, ILP, and LPI) have conservation ≥ 0.70, suggesting that the latter fragments may have a larger impact on CCL28 function (Figure 5C). To functionally evaluate CCL28 N-terminal fragments, we tested a series of N-terminal truncation mutants in calcium flux assays in cells expressing receptors CCR3 and CCR10 (Figure 5D; Figure S6F; Table S2). WT CCL28 (SEA; beginning with SerNTc.Cm10) and CCL28-EAI were among the least potent of the tested mutants at both receptors, consistent with the relatively poor conservation of CCL28 3-mer fragments SEA and EAI. In contrast, CCL28-AIL and CCL28-ILP were more potent at both receptors relative to CCL28-SEA and CCL28-EAI. In effect, deletion of SerNTc.Cm10 and GluNTc.Cm9 enhanced CCL28 activation of CCR3 and CCR10, suggesting that these residues, which comprise poorly conserved fragments, negatively impact CCL28 signaling. Notably, while CCL28-LPI showed enhanced activation of CCR3, it showed severely diminished activation of CCR10 (Figure 5D). Together, these data highlight how the same chemokine can differentially modulate activity at different receptors via distinct linear motifs in unstructured regions (Figure S6G).

These analyses support a role for SLiMs in customizing chemokine-GPCR interactions through multiple mechanisms, such as employing the same SLiMs to serve analogous functions (e.g., the ELR motif in CXCR1/2-binding chemokines34,35), or unique SLiMs to customize chemokine- or GPCR-specific functions (e.g., distinct CCL28 SLiMs to encode CCR3 and CCR10 recognition). By concentrating chemokine and GPCR selectivity preferences into SLiMs, chemokine and GPCR selectivity can rapidly evolve through emergence or loss of SLiMs rather than re-engineering the entire interface.

Variant and phenotype mapping to selectivity determinants

We hypothesized that population variants at the chemokine-GPCR interaction interface in the human population might influence selectivity. We gathered variant information for all human chemokines and receptors from three databases: (1) naturally occurring variants from >140,000 healthy individuals from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD)52; (2) cancer-associated variants from >10,000 individuals and 33 different cancer types from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)53; and (3) genome-wide statistical associations between variants and disease- or phenotype-associated traits based on data from ~500,000 individuals from the GeneATLAS database (using data from the UK Biobank).54 Only missense variants were considered. We mapped variants to CCN and CRN numbering systems and identified genes with the most abundant naturally occurring variants, cancer-associated variants, and phenotypic associations affecting chemokine-GPCR interface residue positions (Figures S6H and S6I; Tables S3, S4, and S5).

At the gene level, cancer-associated variants were infrequent, with the most variable gene, CCR2, bearing cancer-associated variants in only ~0.3% of tumor samples (Figure S6H; Table S3). In effect, despite established roles for chemokines and receptors in cancer,55–58 chemokine-GPCR interface mutations are unlikely to constitute a major oncogenic mechanism. Naturally occurring variants were far more common than cancer-associated variants, with (cumulative) interface variant allele frequencies of ~31% (i.e., CCL24) and ~52% (i.e., ACKR1) for the most variable chemokines and receptors, respectively (Figure 6I; Table S4). Disease- and phenotype-associated variants at interface positions in the UK Biobank dataset revealed 8 chemokines and 6 receptors with statistically significant variant-phenotype associations (Figure S6J; Table S5).59 Among these, the chemokine and GPCR with the most associated phenotypes were CCL1 and ACKR1, respectively. Phenotypes most associated with chemokine and receptor variants commonly involve immune-related traits such as blood/immune cell type counts, inflammatory diseases, and infections, consistent with the essential role of chemokines and GPCRs in innate and adaptive immune functions (Table S4).

Figure 6. Rational design of altered selectivity using a promiscuous viral chemokine.

(A) HHV-8-mediated expression of vMIP-II, which binds CC and CXC receptors to modulate host immunity.

(B) Distribution of “prediction probability scores” among chemokine interface residues from chemokine-GPCR complexes by histogram (STAR Methods; Figure S7F). Scores assess likelihood that a queried residue belongs to a CC (i.e., closer to 0) or CXC (i.e., closer to 1) chemokine. Interface residues from Zheng et al.31 model were used for CCL5.

(C) Percentage interface residues from (B) comprising CC- versus CXC-like residues and mapping onto CCL5/vMIP-II structures.

(D) Positions of vMIP-II mutants tested.

(E) Log fold change of IC50 (or EC50 for CCR3) of vMIP-II mutants versus WT for vMIP-II “reversion” mutants, tested at CCR3, CCR5, and CXCR4 in β-arrestin recruitment assays (Figure S7I; STAR Methods). All data n = 3. WT vMIP-II and mutants tested as agonists (CCR3) or antagonists (CCR5: in competition with CCL5; CXCR4: in competition with CXCL12). See Table S2.

See also Figure S7.

Altered selectivity of a common variant in the ACKR1 unstructured N terminus

The most frequently occurring chemokine-GPCR interface variant—ACKR1 Gly42AspNTr.Cm9 (Figure 5E)—influences Plasmodium vivax susceptibility.60,61 Individuals with the ACKR1 Gly42 NTr.Cm9 allele have resistance to P. vivax, whereas individuals with the ACKR1 Asp42NTr.Cm9 allele are P. vivax susceptible.62 ACKR1 is an erythrocyte coreceptor for P. vivax, which directly interacts with the sulfated ACKR1 residue Tyr41NTr.Cm10 (adjacent to Gly/Asp42 NTr.Cm9) via its Duffy binding protein (PvDBP).63 Importantly, sulfation of Tyr41NTr.Cm10 is necessary for PvDBP binding to ACKR1.63,64 Differences in P. vivax susceptibility are thought to have shaped divergent, population-specific allele frequencies. Indeed, while the overall allele frequencies of Gly42NTr.Cm9 and Asp42NTr.Cm9 are roughly equivalent (Figure 5F), the P.-vivax-resistant Gly42NTr.Cm9 allele is enriched in Southeast Asia where P. vivax endemicity is highest62 (Figure S7A).

Since P. vivax infection is influenced by adjacent residues in the unstructured ACKR1 N terminus, we hypothesized that Tyr41NTr.Cm10 and Gly/Asp42NTr.Cm9 function in tandem as a SLiM. We analyzed ortholog and paralog conservation of sequence fragments comprising Tyr41NTr.Cm10 and Gly/Asp42 NTr.Cm9 (e.g., fragments YG, YD, DYD, DYG, etc.) in ACKR1 and other chemokine receptors (Figure S7B). YD-containing fragments are shared among 11 receptors versus 6 receptors containing YG fragments, suggesting a broader role for YD-containing fragments. Likewise, YD-containing fragments have higher ortholog conservation among all chemokine receptors and are thus more likely to represent a functional SLiM (Figure S7C).

To evaluate whether Gly42NTr.Cm9 versus Asp42 NTr.Cm9 influences ACKR1 chemokine selectivity, we developed a BRET-based ACKR1 binding assay (Figure S7D; STAR Methods). Among CCL2, CCL7, CXCL1, CXCL8, and CXCL11, all showed modest but consistent decreases in potency against ACKR1 Gly42NTr.Cm9 as compared with ACKR1 Asp42NTr.Cm9 (Figure 5G; Table S2). While CXCL12 binding to ACKR1 was weak in the assays, we assessed CXCL12 binding in vitro via isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) using purified ACKR1 N-terminal peptides (1–60). As with other chemokines, CXCL12 showed modestly reduced potency for ACKR1 Gly42 NTr.Cm9 versus Asp42NTr.Cm9 (Figure 5H).

The consistency of observed differences across chemokines suggests that common variants might influence chemokine/GPCR function and phenotype. Indeed, ACKR1 Asp42NTr.Cm9 had the most phenotypic associations, and all were related to changes in immune cell counts (Figure S7E). Given key roles for ACKR1 at endothelial surfaces involved in leukocyte trafficking and diapedesis, we propose that binding differences between ACKR1 Gly42NTr.Cm9 and Asp42 NTr.Cm9 might modulate circulating lymphocyte counts. More broadly, variations at key selectivity positions within the chemokine-GPCR interface might present functional, phenotypic, evolutionary, and disease-relevant trade-offs (Figure 5I).

Rewiring selectivity preferences of a promiscuous, viral chemokine

We next tested whether we could leverage the identified selectivity determinants to rationally manipulate chemokine-GPCR selectivity, using the chemokine viral macrophage inflammatory protein II (vMIP-II) as a test case. vMIP-II is secreted by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV, a.k.a. HHV-8)-infected cells to facilitate viral immune evasion.65,66 Despite being a CC-subfamily chemokine, vMIP-II acts through receptors in both CC and CXC subfamilies (Figure 6A).

We hypothesized that vMIP-II recognizes receptors of both subfamilies by encoding CC- and CXC-specific sequence features. We evaluated the similarity of vMIP-II residues to those of CC versus CXC subfamily chemokines by using our logistic regression model to assign prediction probability scores (Figure 3C), with human CC and CXC chemokine sequences as controls (STAR Methods). While vMIP-II possesses some CXC-like residues, its sequence predominantly comprises CC-like residues, “true” to its identity as a CC chemokine (Figure S7F; all residues). We next mapped vMIP-II prediction probability scores to the vMIP-II-CXCR4 complex,39 which features the viral CC chemokine bound to a receptor of the CXC subfamily. Despite its overall similarity to CC chemokines, vMIP-II preferentially utilizes CXC-like residues to contact CXCR4 (Figures 6B and 6C; interface residues only).

Given the small number of CXC-like residues at the vMIP-II-CXCR4 interface, we hypothesized that targeted mutations of these residues would selectively diminish its interactions with CXCR4 while preserving interactions with CC receptors. We selected vMIP-II Arg7NTc.Cm4 and Lys10NTc.Cm1, since both residues contact subfamily-specific positions in CXCR4 and are also likely to influence vMIP-II recognition of CC receptors (Figure 3F). Based on similarities of the GPCR interaction profile of vMIP-II to CCL8 (Figure 6A; Table S1), we used CCL8-specific residues Ile7NTc.Cm4 and Thr10NTc.Cm1 as templates for residue substitutions. Indeed, the proposed mutations are likely to convert them from CXC-like to CC-like residues using logistic regression scoring (Figure S7G). Moreover, the vMIP-II mutations Lys10ThrNTc.Cm1 and Arg7IleNTc.Cm4 would introduce putative SLiMs, PxT, and IP, which are found in chemokines with overlapping interaction profiles to vMIP-II (Figure S7H). We introduced Leu13Phecxb1.1, which we predicted would preserve vMIP-II’s interactions with CC receptors but diminish its interactions with CXCR4 by opposing the aromatic Phecxb1.1 with a large, negatively charged Glu2777x27 in CXCR4, (i.e., negative selectivity filter; Figure 4G).

All three vMIP-II mutations (Arg7IleNTc.Cm4, Lys10ThrNTc.Cm1, and Leu13Phecxb1.1) were tested alone and in tandem alongside WT vMIP-II, in β-arrestin-1 recruitment assays against CCR3, CCR5, and CXCR4 (STAR Methods) (Figures 6D and 6E; Figure S7I; Table S2). Since vMIP-II is a CCR5 and CXCR4 antagonist, vMIP-II WT and variants were tested in concentration-response in the presence of a set concentration of agonist chemokines (i.e., CCL5 and CXCL12, respectively) to observe the potency of vMIP-II at inhibiting β-arrestin recruitment. Since vMIP-II is a CCR3 agonist, we performed standard concentration-response β-arrestin-1 recruitment assays. All three vMIP-II mutants (Arg7IleNTc.Cm4, Lys10ThrNTc.Cm1, and Leu13Phecxb1.1), individually or in tandem, showed similar or enhanced potency versus WT vMIP-II at CCR3 and CCR5 (Figure 6D; Figure S7I). The vMIP-II triple mutant, which converts vMIP-II into a mild partial agonist (Figure S7I), showed more drastically enhanced IC50 than the individual mutants at CCR5. Jointly, these results suggest how strategic single amino acid substitutions in key, selectivity-determining positions can result in an alteration of function (e.g., enhancement in CCR3 or a gain of function in CCR5).

In contrast to their neutral-to-positive effects at CCR3 and CCR5, vMIP-II mutants caused decreases in potency at CXCR4 in all but one instance. The vMIP-II triple mutant had the largest effect, followed closely by Arg7IleNTc.Cm4 and Leu13Phecxb1.1. These results are consistent with the proposed roles of these mutations in disrupting numerous subtype-specific interactions within CXCR4 (NTc.Cm4) or introducing negative selectivity by opposing a bulky aromatic (cxb1.1) with a large, acidic residue. In contrast, Lys10ThrNTc.Cm1 had minimal effects versus WT vMIP-II at CXCR4. Testing vMIP-II mutants in a chemotaxis assay using CXCR4-expressing, human-derived T cells generally mirrored the pharmacology results. All mutants except vMIP-II Lys10ThrNTc.Cm1, showed a diminished ability to inhibit chemotaxis relative to WT vMIP-II (Figures S7J–S7L). These results support the notion that the basic principles of chemokine-GPCR selectivity and promiscuity identified here can guide targeted changes to chemokine sequences to modulate binding preferences and effects on cell migration. Moreover, the ability to modulate the selectivity of a viral chemokine for human chemokine receptors using the framework developed here suggests that the hierarchical organization of selectivity determinants is a robust and generalizable concept.

DISCUSSION

We find that chemokine-GPCR selectivity is hierarchically encoded in conserved, semi-conserved, and poorly conserved sequence and structural elements. Conserved and semi-conserved elements comprise a small fraction of the chemokine-GPCR interface, which is largely dominated by customized interactions involving unstructured regions. The results presented here suggest that different levels of promiscuity are encoded by “tuning” contact similarities among unstructured regions, which contain many 2–4 residue functional hotspots known as SLiMs. In effect, complex patterns of chemokine-GPCR selectivity and promiscuity may emerge from the rapid evolution of unstructured regions.

Encoding and decoding selectivity using public and private “keys”

Selectivity encoding in chemokine-GPCR interactions shares features with digital encryption methods in which two parties (e.g., buyer and seller) can exchange a message (e.g., credit card information) in a public online space using shared public codes and party-specific private codes (Figure 7A). In this scheme, the sender ensures only the intended recipient can unlock the message by providing a composite of public and private codes. The recipient then combines their own public and private codes with those of the sender to form a shared secret message, which is distinct from those used by all other possible pairs of parties.

Figure 7. Encoding and decoding chemokine-GPCR selectivity and promiscuity.

(A) Encryption model for chemokine-GPCR selectivity encoding.

(B) Chemokine-GPCR network editing applications.

(C) Chemokine regulation of complex multicellular circuits for therapeutic applications.

As with digital encryption, the chemokine-GPCR systems distribute selectivity information comprised of generalized (“public”), subfamily-specific (“semi-private”), and network-specific (“private”) sequence and structural elements. During chemokine-GPCR engagement, codes are presented by each party as a composite, where different codes are intermixed among one another on the chemokine (or GPCR) surface and within structured and unstructured regions. In turn, the GPCR binding partner decodes the specific message by structurally positioning its own composites alongside that of chemokine (or vice versa). Importantly, the robustness of encryption results from the distinctiveness of the private codes, which are concentrated in rapidly evolving, unstructured regions. The complexity of private codes (unstructured regions) ensures that every unique pair of chemokines and GPCRs will distinctly encode messages from all other pairs, which may additionally help explain how even closely related chemokines can generate qualitatively distinct signaling profiles.67

Design principles and applications for selectivity-edited chemokines and GPCRs

We leveraged principles of selectivity encoding in the chemokine-GPCR system to design variants of the viral chemokine vMIP-II with a more restricted GPCR selectivity profile. While analogous applications will require context-specific considerations, a generalized framework may help guide design applications. First, one should consider the intended application, including network edge deletion (i.e., removing a subset of existing interactions), network edge addition (i.e., adding new interactions while preserving existing ones), and network orthogonalization (i.e., devising chemokines and GPCRs that exclusively bind one another without engaging native binding partners; Figure 7B). Second, one should gather aligned sequences, including (1) the desired chemokine/GPCR to edit, (2) “in-network” chemokines/GPCRs (e.g., other chemokines that bind the same GPCR as the chemokine of interest), and (3) “out-of-network” chemokines/GPCRs (e.g., chemokines within the same subfamily that do not bind the same GPCR(s) as the chemokine of interest). Third, one should examine residues participating in (1) subfamily-specific interactions (Figure 3F) and (2) structurally preserved contacts between poorly conserved sequence positions (Figure 4A) and identify opportunities to either introduce or remove residues that are likely to participate in unfavorable interactions, using out of network chemokines and GPCRs to guide. Finally, one should identify opportunities to remove or introduce SLiMs, using those contained within the unstructured regions of in-network or out-of-network chemokines/GPCRs to guide (Figure 7B).

Some applications are likely to be more difficult than others. Network edge addition applications may require the introduction of several mutations, some of which may negatively impact the existing function (e.g., native selectivity preferences) and stability of the WT protein.68 We also anticipate that network edge addition applications that attempt to introduce interactions to more unrelated chemokines/GPCRs (e.g., CC chemokine interactions with a CXC receptor) or network edge deletion applications that attempt to eliminate interactions among closely related chemokines/GPCRs (e.g., eliminate CCR3 but not CCR5 coupling of CCL5) will be challenging.

How might “network-edited” chemokines and GPCRs be utilized in therapeutic applications? Cell-based therapies, such as engineered chimeric antigen receptor T cells, have a number of limitations, including a lack of precision trafficking, imprecise tumor recognition, and transient efficacy (e.g., T cell “exhaustion”).69 Incorporating network-edited chemokines and GPCRs into the design of cell-based therapies could help overcome these limitations, for instance, by enhancing targeting prior to activation.70,71 As master regulators of cell migration, chemokines and GPCRs have the potential to function as programmable logic gates that control cell migration in complex multicellular circuits (Figure 7C).72

Limitations of the study

Chemokine-GPCR selectivity is modulated by tissue-specific expression patterns,73–75 chemokine-glycosaminoglycan (GAG) interactions,76 oligomerization,77 and other factors not considered here. Future work should investigate selectivity encoding among ACKRs, which may have distinct chemokine-binding modes.37,78 Structures of human chemokine-GPCR complexes that were published during the late stages of manuscript preparation or review78–86 could not be included in our analysis. Some structures used in this study have limited resolution of interface interactions involving unstructured regions, which play important roles in recognition.24 Regarding SLiMs, we employ conservation as a proxy for functional importance; however, organism-specific motifs can emerge, especially when unique selective pressures such as host-pathogen interactions are considered.87,88 Relatedly, the specific functional roles of SLiMs (e.g., contributions to specific binding partner interactions) cannot be distinguished from other functions by our method alone due to interface customization among complexes and contributions of conformational dynamics to binding.89,90 Additional experiments will be needed to explore applicability of selectivity principles to chemokine-GPCR interactions not tested here. For instance, future efforts that pursue network edge addition applications, applications using human-only chemokine-GPCR networks, and network orthogonalization, among others, can further validate the findings and the presented framework.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, M. Madan Babu (madan.babu@stjude.org).

Materials availability

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. All original code has been deposited at github.com and is publicly available at https://github.com/andrewbkleist/chemokine_gpcr_encoding as of the date of publication. Any additional information required to re-analyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

STAR★METHODS

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Cell lines

Cell lines used in this study include HEK293T cells (ACKR1 binding assays; CCR5 and CXCR4 β-arrestin recruitment assays; Abcam, ab255449), Chem-1 Ready-to-Assay™ CCR3 Chemokine Receptor Frozen Cells (CCR3 calcium flux assays; Eurofins, HTS008RTA), Chem-1 Ready-to-Assay™ CCR10 Chemokine Receptor Frozen Cells CCR10 calcium flux assays; Eurofins, HTS014RTA), and healthy donor T cells (derived from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PBMCs). HEK293T cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C with 5% CO2. HEK293T cells were checked for mycoplasma contamination upon receipt (Venor®GeM OneStep kit; Cat. No.: 11–8100, Minerva Biolabs GmbH) and routinely every 3 months. Ready-to-Assay™ CCR3 and CCR10 Chemokine Receptor Frozen Cells were prepared per manufacturer instructions by thawing supplied frozen cell stocks, washing, resuspending using supplied reagents, and plating in 96-well plate for 24h for calcium flux assays (see below for assay details). CCR3/CCR10 cells were used shortly after receipt and were not specifically tested for mycoplasma. T cells were isolated from PBMCs by direct enrichment of leukapheresis product by immunomagnetic separation using CD4+/CD8+ microbeads (Miltenyi, Germany), an LS column (Miltenyi), and an AutoMACS separator (Miltenyi). Cells were then frozen in Recovery™ Cell Culture freezing media (Gibco, NY, USA) at 1 × 107 cells/mL in a 1 ml cryovial. Frozen stocks of PBMC-enriched T cells were grown in RPMI 1640 (Cytiva, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA), 1% GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and cytokines IL7 and IL15 (10 ng/mL each) (Biological Resources Branch, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD, USA, and PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) prior to experimental setup. PBMCs were obtained from deidentified healthy donor pheresis products and are exempt from IRB permissions. Enriched T cells were authenticated by measuring CD4, CD8, and CXCR4 expression (among other markers, see below) by flow cytometry. All other cell types were purchased directly from suppliers prior to experimental use and were thus not independently authenticated.

METHOD DETAILS

Chemokine-GPCR interaction network

An initial matrix of reported chemokine-GPCR interactions was established using published interaction matrices from review articles108–113 and pairwise chemokine-GPCR interactions extracted from CellphoneDB.74,114 Additional interactions and annotations were incorporated during table annotation. Each entry (i.e. row) encompasses a single chemokine-GPCR interaction associated with a specific reference, such that two different references reporting the same interaction are listed as two entries. For each entry in which ligand binding data, signaling data (e.g. calcium flux or cAMP accumulation), or chemotaxis data were presented, an “Interaction Strength” was assigned, with “3” assigned for ligand binding Kd or Ki, ligand binding EC50 or IC50, signaling data EC50 or IC50, and/or maximal chemotaxis values ≤ 100nM; “2” assigned for the same parameters with values > 100nM and ≤ 1000nM; “1” assigned for the same parameters with values > 1000nM; and “0” assigned if the interaction was tested but no effect was observed. Each entry was also assigned an “Evidence Grade”, with “A” assigned for quantitative evidence derived from dose-response testing (e.g. binding Kd, binding or signaling EC50, IC50); “B” assigned for semi-quantitative evidence derived from testing of numerous ligand concentration points but without a derivation of a quantitative summary statistic such as EC50/IC50, etc. (e.g., dose of maximal chemotaxis among three tested doses); “C” assigned for qualitative evidence (e.g., lack of response noted in raw calcium flux traces from stimulation using a single concentration); and “D” assigned for indirect evidence (e.g., ligand-stimulated chemotaxis of native cells known to express receptor of interest). Claims made based on evidence not provided (e.g., “data not shown”) were not considered. For interactions supported by evidence in multiple papers, not all instances were compiled. Data from transfected cells were prioritized over that from primary cells due to higher confidence of receptor expression profiles in the former.

Interactions with an Interaction Strength ≥ 2 and supported by at least one reference with Evidence Grade C were considered for analyses that incorporate network information (Figure 1D; Figure S1B; Figure 3B). Network information is available as Table S1. The network representation of CC and CXC chemokine receptors (Figure 3B) incorporates human CC and CXC chemokines and GPCRs from Table S1 (inclusive of interactions with an Interaction Strength ≥ 2 and supported by at least one reference with Evidence Grade C). The chemokine-GPCR network representations were generated with Cytoscape.

Endogenous ligand and receptor numbers among GPCR families from Classes A, B, C, and F

Endogenous ligand and receptor data were downloaded from the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology/British Pharmacological Society (IUPHAR/BPS) Guide to Pharmacology (http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ReceptorFamiliesForward?type=GPCR) from the GPCR list page.115 Data for Class A, Class B, Class C, Class Frizzled, and Adhesion class, and ligand sets were manually edited to retain only human ligands. All data were processed and plotted in R.

Chemokine sequence acquisition and sequence alignment

Acquisition of human chemokine paralog sequences and alignment

Human chemokine paralogs were compiled from Pfam116 and Uniprot117 yielding the following list of 46 human chemokines: CCL1, CCL2, CCL3L1, CCL3, CCL4L1, CCL4, CCL5, CCL7, CCL8, CCL11, CCL13, CCL14, CCL15, CCL16, CCL17, CCL18, CCL19, CCL20, CCL21, CCL22, CCL23, CCL24, CCL25, CCL26, CCL27, CCL28, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL4L1, CXCL4, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL7, CXCL8, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL12, CXCL13, CXCL14, CXCL16, CXCL17, CX3CL1, XCL1, XCL2. The chemokines CCL3L3 and CCL4L2 were found in Ensembl but not Uniprot and were thus excluded from analysis. For each of the 46 human chemokine paralogs, full length, unprocessed sequences were downloaded from www.uniprot.org by selecting the listed ‘canonical’ sequence.

Sequence alignment of human chemokine paralogs proceeded as follows. First, experimental structures were downloaded from the PDB for the 35 of 46 human chemokines having at least one structure at the time of initial alignment construction (March 2017), which included the following PDBs (PDB ID is listed with the selected chain indicated after the underscore): 1EL0_A, 1DOK_A, 3FPU_B, 1JE4_A, 1U4P_A, 1NCV_A, 1ESR_A, 1EOT_A, 2RA4_A, 2Q8R_A, 2HCC_A, 1NR4_A, 4MHE_A, 2MP1_A, 1M8A_A, 5EKI_A, 1G91_A, 1EIG_A, 1G2S_A, 2KUM_A, 1MSG_A, 1QNK_A, 1RHP_A, 2MGS_A, 1NAP_A, 5D14_A, 1LV9_A, 1RJT_A, 2J7Z_A, 4ZAI_A, 2HDL_A, 4XT1_B, 1J9O_A, 4HSV_A, 6CWS_A. Waters, cofactors, and other non-protein components were removed using the ‘trim’ command from the “Bio3D” package in R.98 Second, trimmed PDBs were used to generate a structure-based sequence alignment via MUSTANG.105 Third, for the 25 sequences for which structures were available, Uniprot sequences substituted into the structure-based alignment for the corresponding chemokine while preserving the overall alignment. Fourth, full length Uniprot sequences for all 46 chemokine paralogs were independently aligned via MUSCLE.104 Fifth, sequences for each of the 10 chemokines lacking structures were paired with those of closely related chemokines for which structures were available from the MUSCLE alignment. The two sequences were then adjusted in tandem to align the sequence-based MUSCLE alignment to the structure-based MUSTANG alignment using sequence represented in both MUSTANG and MUSCLE alignments as a “bridge”. Sixth, the alignment containing all 46 human chemokine sequences was manually inspected and refined. Sequence visualization and manual refinement was performed in Jalview.101

Since chemokine N- and C-termini are unstructured, they were not considered during structure (MUSTANG)- and sequence (MUSCLE)-based alignment steps. Instead, they were positioned without gaps adjacent to the first chemokine cysteine that is involved in disulfide bonding (N-terminus) and the C-terminal helix (C-terminus), respectively. The boundaries of the N-terminal, core, and C-terminal master alignments were chosen by demarcating the core as spanning the first Cys of the Cys motif (i.e., CC, CXC, CX3C, XC) to the last residue of the helix as defined by CXCL12 residue Ala65 (numbered from the CXCL12 N-terminus starting with 1-KPVS-…), which is defined as the end of the helix in the CXCL12 using PDB ID 2J7Z. Residues on either side of these boundaries were defined as belonging to the N- and C-termini, respectively. While the N- and C-terminal regions are unstructured, inspection of isolated chemokine-GPCR complex structures indicates that the core-adjacent residues within these regions are constrained by proximity to the structured core, such that alignment positions of core-adjacent residues are likely to encode functionally relevant relationships between chemokines.

Acquisition and alignment of chemokine ortholog sequences

For each of the 46 human chemokine paralogs, 1:1 orthologs were acquired by searching the Orthologous MAtrix (OMA) database using human canonical Uniprot sequences.93,118 For the chemokines CCL14, CCL15, CCL19, CCL23, CXCL12, CXCL16, and CX3CL1, the given human sequence from OMA did not match the human canonical sequence from Uniprot, so the OMA sequence was used. OMA did not report 1:1 orthologs for the chemokines CCL4, CCL4L1, CCL5, XCL1, and XCL2. 1:1 orthologs for CCL4 and CCL5 (but not CCL4L1, XCL1, and XCL2) were identified via Ensembl Compara.119 The final alignment contained orthologs lists for 43/46 human paralogs with 3 or more orthologs per chemokine. Sequences were downloaded from OMA between April 21, 2017 and June 24, 2017 and from Ensembl Compara on June 24, 2017. To create a master alignment of all ortholog and paralog sequences, ortholog sequences for each chemokine were independently aligned using MUSCLE, then mapped to the structure-based alignment of human chemokine paralogs using the human paralog sequence in both alignments as a “bridge”. The master alignment of chemokine sequences contains 1058 sequences, comprised of 46 human chemokine paralogs and ortholog sets for 43/46 human paralogs. After making the master alignment, additional alignments were generated by selecting different subsets of chemokine sequences for conservation analysis. The following alignments were utilized: (1) a master alignment containing 1058 sequences, including all 46 human paralog sequences and sets of ortholog sequences for 43/46 chemokines; (2) a human paralog alignment containing 46 human chemokine paralog sequences; (3) subfamily-specific human paralog alignments containing 26 (CC subfamily) or 17 (CXC subfamily) human chemokine sequences, (4) a CC-/CXC-alignment containing only CC and CXC ortholog and paralog sequences (i.e., excluding CX3CL1, XCL1, and XCL2 orthologs/paralogs); and (5) chemokine-specific ortholog alignments containing ortholog sequences for each of the 43/46 human chemokines for which at least 3 one-to-one orthologs could be obtained.

Alignment of N-termini for chemokine ortholog sequences

For the 43/46 chemokines having 1:1 orthologs, ortholog N-terminal sequences (i.e., up to but not including the first conserved cysteine) were aligned using the KMAD knowledge-based multiple sequence alignment algorithm, which is optimized for enrichment of short linear motifs (SLiMs) in unstructured regions.102 The KMAD algorithm produces “insertion free” alignments by removing residues that fail to match motifs identified in a reference sequence. Each set of ortholog sequences were aligned independently, using the human sequence as the reference sequence.

Common chemokine numbering scheme

Common chemokine numbering (CCN) positions (Figure S2) are defined as follows: each secondary structural element (SSE) is given an identifier (i.e., NTc = N-terminus; CX = Cys region; cxb1 = N-loop; B1 = β1-strand; b2b2 = 30s-loop; B2 = β2-strand; b2b3 = 40s-loop; B3 = β3-strand; b3h = 50s-loop; H = helix; CT = C-terminus) and each position within the SSE is given an index (e.g., b1b2.3 = third residue in the 30s-loop), analogous to previous studies on G proteins, GPCRs, arrestin, and TATA-box-binding protein (TBP).26,120–122 Loops are designated using the two adjacent structured SSEs in lowercase lettering (e.g., the loop region referred to as the “30s-loop” occurs between the β2- and β3-strands and is designated as b2b3). N-terminal positions are named using the SSE identifier NTc (i.e. N-terminus of chemokine), followed by a period and a modified numerical index prefaced by “Cm”, to indicate that the residue position in question is at position “cysteine minus” the indicated number of residues. For instance, “NTc.Cm3” indicates a residue in the chemokine N-terminus three residues preceding the first disulfide-bonding cysteine.

Chemokine receptor sequence acquisition, sequence alignment, and common numbering

Compilation of human chemokine receptor paralogs from Pfam,116 Uniprot,117 and GPCRdb26 yielded the following list of human chemokine receptors: CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, CCR6, CCR7, CCR8, CCR9, CCR10, CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR3, CXCR4, CXCR5, CXCR6, CX3C1, XCR1, ACKR1, ACKR2, ACKR3, ACKR4, CCRL2. At least one study reports a seventh CXC family receptor (GPR35, referred to as “CXCR8”),123 however this was disputed in another report124 and thus excluded. Human chemokine receptor paralog sequences were downloaded from Uniprot. For each of the 23 human chemokine receptor paralogs, 1:1 ortholog sequences were downloaded from OMA.93,118 In cases for which OMA and Uniprot canonical sequences did not match, the OMA human sequence was used. Ortholog sequences were independently aligned using MUSCLE, resulting in 23 sequence alignments (i.e., one alignment containing multiple chemokine receptor orthologs for each of the 23 human chemokine receptor paralogs). Insertions in chemokine receptor ortholog sequences that were not present in the human sequence were remove since this study focuses on the human chemokine-GPCR system. The 23 ortholog sequence alignments were manually maped to the structure-based alignment of the chemokine receptor family downloaded from GPCRdb26 by using human chemokine receptor sequences as a “bridge”. The resulting chemokine receptor master alignment contains 951 sequences, comprised of 23 human chemokine receptor paralog sequences, and ortholog sequences for 23/23 human paralogs. Using the master alignment, additional alignments were generated by selecting different subsets of sequences for analysis. The following alignments were utilized: (1) a master alignment containing 951 sequences, including all 23 human paralog sequences and sets of ortholog sequences for all 23 human receptors; (2) a human paralog alignment containing only the 23 human receptor paralog sequences; (3) subfamily-specific human paralog alignments containing 10 (CC family) or 6 (CXC family) human receptor sequences; (4) a CC-/CXC- subset of the master alignment contains only CC and CXC orthologs and paralogs (i.e., excluding ACKR1–4, CCRL2, XCR1, and CX3CR1); and (5) receptor-specific ortholog alignments containing ortholog sequences for each of the 23 human receptors.

Common chemokine receptor numbering scheme

The existing GPCRdb numbering was used to refer to structurally equivalent positions across GPCR structures with minor modifications. The GPCRdb alignment used at the time of sequence acquisition designates the first common numbering position as occurring in transmembrane domain 1 (TM1) at position 24 (GPCRdb numbering: 1×24). We extended the common numbering scheme toward the N-terminus of our master chemokine receptor alignment to include a conserved N-terminal cysteine. The conserved N-terminal cysteine forms a disulfide bond with a cysteine in TM7 in chemokine receptors (common chemokine receptor numbering [CRN] position 7×24).27,44,125 To implement this modification, conserved cysteines were manually aligned in the master alignment (i.e. the alignment containing all chemokine receptor paralogs and orthologs) and the N-terminal cysteine residue was designated 1×22. The residues following 1×22 were then aligned without gaps adjacent to the cysteine and designated as position 1×23. While existing GPCRdb assignments were not changed, alignments for which gaps were present in the existing GPCRdb alignment were modified in our CRN to move unassigned residues into gapped TM1 positions. For example, in the GPCRdb alignment for CCR2, Lys34, Phe35, and Asp36 are unassigned (and positioned to the N-terminus of the start of TM1) and CCR2 has gaps at positions 1×24–1×26. In our CRN, we moved these three residues into the gapped region, yielding Lys341×24, Phe351×25, and Asp361×26 CRN assignments. As with the chemokine sequence alignment, N-terminal positions were “stacked” against Cys1×22 and designated with the SSE identifier NTr (i.e. N-terminus of receptor) followed by a period and a modified index prefaced by “Cm” to indicate that the residue position in question is at position “cysteine minus” the indicated number of residues. For instance, “NTr.Cm3” refers to the residue in the receptor N-terminus that precedes the first disulfide-bonding cysteine by three residues. The chemokine receptor alignment in the region of extracellular loop 2 (ECL2) was left unmodified relative to the existing GPCRdb alignment between positions 4×56–45×52. Residue positions succeeding 4×56 and preceding 45×50 were assigned identifiers ECL2.1-ECL2.13. The GPCRdb alignment in this region adjusts sequence positions without gaps and coming after TM4, such that positions after 4×65 and prior to 45×50 are non-structurally equivalent. As such, conservation scoring of this region was not performed. The region between the residue position succeeding 45×52 and the residue preceding 5×31 were modified by removing all gaps and thus “collapsing” all residues coming after the GPCRdb-aligned positions 45×50–45×52 toward the C-terminal end of this region. Following our convention used for chemokine receptor N-terminus, residues succeeding 45×52 were designated with SSE identifier ECL2 followed by a period and a modified index beginning with “Cp” to indicated “cysteine plus.” Since the conserved ECL2 Cys occurs at position 45×50 and GPCRdb provides alignments through 45×52, the modified nomenclature starts at ECL2.Cp3 in our CRN. At ECL3, CCR2 was adjusted to move Cys277 into position 7×24, which contains the conserved Cys that is disulfide-bonded to Cys1×22 in all other chemokine receptors except CXCR6 – the only chemokine receptor that does not have a Cys at this position or at the N-terminus-TM1 junction.

Conservation scoring of chemokine and GPCR orthologs and paralogs

CCN- and CRN-specific conservation scores were generated for the following sets of sequences for both chemokines and chemokine GPCRs: human chemokine and GPCR paralogs (1 alignment each), human CC paralogs (1 alignment each), human CXC paralogs (1 alignment each), human CC and CXC paralogs combined (1 alignment each), human atypical chemokine receptor (ACKR) paralog sequences only (1 GPCR alignment), and chemokine and GPCR orthologs (43 and 23 alignments, respectively). Conservation was calculated on a scale from 0 to 1 using the trident scoring algorithm from the software MstatX using default settings (https://github.com/gcollet/MstatX), with 0 representing no conservation and 1 representing complete identity.103

Subfamily-specific classification of chemokine and GPCR residue positions