Abstract

Background

Data are lacking to guide diagnosis and treatment in patients with skin of color and atopic dermatitis (AD), a population traditionally underrepresented in clinical trials.

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in adults and adolescents with skin of color and moderate-to-severe AD.

Methods

In the open-label ADmirable trial, 90 adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD, Fitzpatrick skin phototype IV–VI, and self-reported race other than White received lebrikizumab 250 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks (Q2W), following a 500-mg loading dose at baseline and Week 2, for 16 weeks. From Week 16 to Week 24, responders, defined as patients with at least 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI 75) and/or Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0/1 with at least a 2-point improvement from baseline, received lebrikizumab every 4 weeks (Q4W); inadequate responders continued lebrikizumab Q2W. The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients achieving EASI 75 at Week 16. Secondary and exploratory efficacy endpoints and safety were assessed throughout. Data were analyzed as observed and using imputation, with Q2W and Q4W populations pooled for Weeks 16–24.

Results

Mean age at baseline was 40.7 years; 43.3% were female; and 43.3%, 24.4%, and 32.2% had Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV, V, and VI, respectively. Baseline mean EASI and Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) scores were 26.4 and 7.0, respectively; 68.9% of patients had moderate disease (IGA = 3). At Week 16 (number of patients with non-missing values [Nx] = 78), EASI 75, EASI 90 (≥ 90% improvement from baseline in EASI), and IGA 0/1 (IGA response of clear or almost clear) were achieved by 69.2%, 44.9%, and 44.9% of patients, respectively; for Pruritus NRS (Nx = 62), 58.1% of patients reported ≥ 4-point improvement. At Week 24 (Nx = 74) (pooled treatment arms), EASI 75, EASI 90, and IGA 0/1 were achieved by 78.4%, 47.3%, and 54.1% of patients, respectively. EASI 75 was achieved by 62.9%, 88.2%, and 95.5% of patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototype IV (Nx = 35), V (Nx = 17), and VI (Nx = 22), respectively, at Week 24. Most patients (64.4%) with baseline PDCA-Derm™-assessed hyperpigmented areas showed reduced hyperpigmentation at Week 24. Most treatment-emergent adverse events were mild or moderate in severity; none were serious or led to discontinuation. One case of conjunctivitis was reported.

Conclusion

In this first lebrikizumab study in patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin phototype IV, V, and VI) and moderate-to-severe AD, lebrikizumab improved signs and symptoms of AD and confirmed its favorable safety profile.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05372419 (registered May 5, 2022).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-025-00970-8.

Key Points

| This open-label, phase IIIb study is the first to assess the efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis exclusively in adult and adolescent patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV, V, and VI), a population traditionally underrepresented in clinical trials. |

| Results from this study show that the majority of patients experienced at least 75% improvement in skin clearance and itch relief, with almost half of patients achieving clear or almost clear skin through 24 weeks of treatment across Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, with continued improvement from Week 16 to Week 24, and confirms lebrikizumab’s favorable safety profile. |

| This study also evaluated novel endpoints measuring AD-related changes in post-inflammatory hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation, finding that hyperpigmentation, assessed through PDCA-Derm™, improved in almost two-thirds of patients by Week 24. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, heterogeneous inflammatory disorder caused by skin barrier dysfunction, immune response dysregulation, and microbiome dysbiosis [1]. In patients with AD, interleukin (IL)-13—a central pathogenic mediator in the disease—is overexpressed, driving multiple aspects of AD pathophysiology by promoting type 2 inflammation resulting in skin barrier dysfunction, pruritus, increased risk of cutaneous infection, and lichenification [2, 3]. In individuals with skin of color, AD often exhibits distinct morphology, distribution, and sequelae compared with AD in those with lighter skin tones [4]. It may present as perifollicular accentuation, nummular plaques, prurigo nodules, or lichenoid papules on extensor surfaces, appearing hyperpigmented or purple in contrast to the classic morphology of erythematous, flexural plaques [4–6]. Excessive inflammation associated with AD can lead to persistent dyspigmentation, which may negatively impact quality of life [5, 7].

Data are lacking to guide diagnosis and treatment in populations traditionally underrepresented in clinical trials, including patients with skin of color [8, 9]. Patients with AD and skin of color may experience a greater disease burden or treatment resistance due to factors such as genetics, environment, socioeconomic status, and healthcare disparities [10–12]. This challenge is further compounded by the complexity of diagnosing moderate-to-severe AD in this patient population, partially due to a historical lack of representation in medical education resources and, in some cases, limited exposure to patients with skin of color in medical training [13–16]. Additionally, the nuances of identifying erythema in patients with skin of color can hinder the accurate and timely diagnosis and treatment of AD and interfere with the application of AD scales commonly used in clinical trials [17].

Lebrikizumab is a novel monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-13 with high affinity and a slow off-rate, thereby blocking the downstream effects of IL-13 with high potency. Phase III studies have demonstrated that lebrikizumab is effective in treating patients with moderate-to-severe AD [18, 19]. A subgroup analysis of these trials showed comparable efficacy among Asian, Black or African American, and White patients [20]. However, to date, no lebrikizumab clinical studies have been conducted exclusively in patients with skin of color. ADmirable (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05372419)—the first lebrikizumab phase IIIb clinical trial to exclusively investigate adult and adolescent patients with AD and skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin phototype IV, V, and VI)—is designed to complement the pivotal phase III findings. By focusing on patients with skin of color, it offers an opportunity to evaluate this underrepresented patient population more accurately and comprehensively than in previous trials.

Methods

Trial Design

This multicenter, open-label, 24-week clinical trial was conducted at 44 sites in the United States (Supplement 1, Table S1, see electronic supplementary material [ESM]). Patients were primarily recruited at investigator sites using internal referrals and site databases. Eligible patients included adults and adolescents (aged ≥ 12 to < 18 years; weight ≥ 40 kg) with AD present for at least 1 year (according to the American Academy of Dermatology Consensus Criteria [21]), moderate-to-severe AD, defined as Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) ≥ 16, Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) ≥ 3, and ≥ 10% body surface area (BSA) of AD involvement at baseline and for whom topical treatments were inadequate or inadvisable. Key eligibility criteria also included Fitzpatrick skin phototype IV, V, or VI and self-reported race other than White, including but not limited to individuals who self-identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander. Patients with history of treatment with tralokinumab or dupilumab were excluded. A washout phase before the baseline visit required discontinuation of topical and systemic AD treatments. An overview of the study design is presented in Supplement 1, Figure S1 (see ESM), and further details, including full inclusion and exclusion criteria, are available in the trial protocol (Supplement 2, see ESM).

At baseline, eligible patients were assigned to receive lebrikizumab 250 mg administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks (Q2W) for 16 weeks, following a 500-mg loading dose given at baseline and Week 2. After 16 weeks of treatment with lebrikizumab Q2W, patients were assessed for response, defined as achieving at least a 75% improvement in EASI (EASI 75) and/or IGA 0/1 (IGA response of clear or almost clear) with at least a 2-point improvement from baseline. Patients meeting the response criteria were administered lebrikizumab 250 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W) through 24 weeks, while inadequate responders continued to receive lebrikizumab Q2W through 24 weeks.

During the trial, patients were allowed to use low- or mid-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS), high-potency TCS ≤10 days, topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, and/or topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitors like crisaborole. For patients experiencing intolerable clinical worsening of symptoms, investigators were encouraged to recommend topical therapy in a staged fashion, beginning with low-potency treatments, followed by mid-potency treatments as necessary. Escalation to high-potency TCS was only permitted after ≥ 7 days of low- or mid-potency topical therapy. Use of high-potency TCS (for >10 days), topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, phototherapy, or systemic medications was considered rescue therapy and required discontinuation from the study.

The ADmirable clinical trial was conducted in accordance with ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, and Good Clinical Practice guidelines [22]. The ADmirable trial protocol was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board on 17 October 2022 (IRB #: Pro00066938). Additionally, Advarra approved the study at each participating center (Supplement 1, Table S1, see ESM). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the initiation of study procedures. For patients considered to be minors, the written consent of the parent or legal guardian, as well as the assent of the minor, was obtained.

Efficacy and Safety Assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage of patients achieving EASI 75 at Week 16. Key secondary endpoints included percent of patients achieving EASI 75 at Week 24, EASI 90 at Weeks 16 and 24, an IGA score of 0 or 1 with ≥ 2-point improvement from baseline at Weeks 16 and 24, ≥ 4-point improvement on the Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) from baseline at Weeks 16 and 24, and ≥ 2-point improvement on the Sleep-Loss Scale from baseline at Weeks 16 and 24. Detailed descriptions of all assessments are provided in Supplement 1, Table S2 (see ESM).

An investigator training module was developed to accurately assess the visible inflammatory changes in the skin of the patients in the study. Photographs that showed examples of patients with skin of color and moderate-to-severe AD were collected and the skin scoring systems were adjudicated using a panel of dermatologists with expertise in this population. The training materials were used to assess disease severity based on the efficacy outcomes described above.

Exploratory Outcomes

In addition to objectives and endpoints commonly evaluated in AD clinical trials, this study evaluated novel endpoints measuring patient-reported symptoms and AD-related changes in hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation. To support the use of these scales and mitigate the complexities of diagnosing patients with AD and skin of color, in-depth training was provided to study sites prior to patient enrollment. This training, developed by experts treating patients with skin of color, included, for example, clinical photos of disease severity and inflammation that are representative of the study population. Select exploratory endpoints included change in PDCA-Derm™ from baseline, percentage change in Patient-Oriented SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD™) from baseline, and a patient satisfaction questionnaire.

PDCA-Derm™ is an investigator assessment of cutaneous post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation [23]. One area of dyspigmentation was assessed in patients with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation throughout the study. In our analysis, patients could contribute to the hyperpigmented and hypopigmented groups if areas with both types were present at baseline. If a patient had multiple areas of the same type (hypopigmented or hyperpigmented) at baseline, instructions were provided to select only one area to ensure equal contribution from each patient in the analysis. Investigators were asked to select a hypopigmented and/or hyperpigmented area, ideally at a location of prior AD and one that did not include, contain, or was immediately adjacent to the active inflammation of AD and was not on the legs or feet, if possible. This same area was to be evaluated at each timepoint. Actively inflamed AD lesions were excluded. Areas of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (as compared to adjacent normal skin tone) were scored on a scale of 1 (mild hyperpigmentation) to 3 (severe hyperpigmentation). Similarly, areas of post-inflammatory hypopigmentation were scored on a scale of − 1 (mild hypopigmentation) to − 3 (severe hypopigmentation). If an area returned to normal pigmentation, it received a score of zero. Assessments were conducted at baseline, Week 16, and Week 24, with results reported for patients with qualifying lesions and non-missing data.

The PO-SCORAD is a 9-item, patient-reported scale used to evaluate the condition of a patient’s eczema over the last 3 days. The PO-SCORAD total score ranges from 0 to 103, with higher scores indicating more severe AD [24]. This study used a version of the scale that was adapted for patients with skin of color [25]. The question assessing patient satisfaction asked, “How satisfied are you with this treatment’s ability to treat your skin condition?” The response options ranged from 1 (not satisfied) to 5 (completely satisfied).

Routine safety assessments included physical examinations, clinical safety laboratory tests (including hematology and chemistry), and the collection of vital signs and spontaneously reported adverse events.

Statistical Analysis

The planned sample size was based on the precision of the point estimate for the primary endpoint. Assuming a true EASI 75 response rate of 50% at Week 16 in this patient population, a sample size of 80 participants was estimated to provide >95% probability that the half-width of the two-sided 90% Wilson score confidence interval of the EASI 75 response rate is at most 10%. The target sample size was later increased to approximately 95 patients to enable exploratory biomarker analyses. All efficacy analyses were based on the intent-to-treat population, defined as all enrolled patients according to their planned intervention. Safety analyses included enrolled patients who received at least one confirmed dose of lebrikizumab 250 mg. Data were analyzed as observed and summarized using frequencies and percentages for discrete variables and mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables. As a supplemental analysis, data for patients who discontinued due to lack of efficacy were imputed using non-responder imputation (NRI); all other missing data were handled using multiple imputation (MI). This imputation strategy is herein referred to as ‘NRI/MI’. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.0 or higher (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline Demographics, Disease Characteristics, and Patient Disposition

A total of 90 patients were enrolled in the trial. The mean (SD) age of these patients was 40.7 (19.6) years. Fourteen (15.6%) patients were adolescents, and 39 (43.3%) were female. Patients self-reported their race as Black or African American (77.8%), Asian (11.1%), American Indian or Alaska Native (6.7%), and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (4.4%), and 21.1% self-reported their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latino. Patients had Fitzpatrick skin phototypes of IV (rarely burns, tans easily; 43.3%), V (very rarely burns, tans very easily; 24.4%), and VI (never burns, tans very easily; 32.2%). Most patients presented with moderate disease (IGA = 3; 68.9%). The mean EASI score was 26.4, mean BSA affected was 37.8%, and mean body mass index (BMI) was 30.1 kg/m2.

Using PDCA-Derm™, 16 patients (17.8%) had one or more hypopigmented lesion and 52 patients (57.8%) had one or more hyperpigmented lesion at baseline. Additional baseline demographics and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. Prespecified clinical presentations at baseline frequently associated with patients with AD and skin of color included AD on the face (58.4%), AD on the hand (50.6%), follicular/perifollicular accentuation of AD (16.9%), AD with prurigo nodules (14.6%), AD with nummular lesions (13.5%), allergic shiners (10.1%), and pityriasis alba (10.1%). A breakdown of these events by severity is reported in Supplement 1, Fig. S2 (see ESM).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

| Lebrikizumab, 250 mg Q2W (N = 90) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.7 (19.6) |

| Adults (≥ 18 years), n (%) | 76 (84.4) |

| Adolescents (12 to < 18 years; ≥ 40 kg), n (%) | 14 (15.6) |

| Female, n (%) | 39 (43.3) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 6 (6.7) |

| Asian | 10 (11.1) |

| Black or African American | 70 (77.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 4 (4.4) |

| Weight (kg) | 87.7 (23.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.1 (7.7) |

| Duration since AD onset (years) | 19.7 (16.1) |

| Age at AD onset (years) | 21.5 (23.6) |

| Fitzpatrick skin phototype, n (%) | |

| IV—rarely burns, tans easily | 39 (43.3) |

| V—very rarely burns, tans very easily | 22 (24.4) |

| VI—never burns, tans very easily | 29 (32.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 19 (21.1) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 71 (78.9) |

| IGA scorea, n (%) | |

| 3, moderate | 62 (68.9) |

| 4, severe | 27 (30.0) |

| EASI score | 26.4 (12.2) |

| % BSA affected | 37.8 (20.5) |

| Pruritus NRS | 7.0 (2.2) |

| ≥ 3b, n (%) | 73 (93.6) |

| ≥ 4b, n (%) | 70 (89.7) |

| Skin Pain NRS | 5.8 (2.8) |

| ≥ 4b, n (%) | 59 (75.6) |

| Sleep loss score | 2.0 (1.1) |

| ≥ 2b, n (%) | 47 (60.3) |

| PO-SCORAD™ c | 57.1 (17.8) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 hypopigmented area using PDCA-Derm™ d, n (%) | 16 (17.8) |

| -1d | 1 (6.3) |

| -2d | 14 (87.5) |

| -3d | 1 (6.3) |

| Patients with ≥ 1 hyperpigmented area using PDCA-Derm™ d, n (%) | 52 (57.8) |

| +1d | 5 (9.6) |

| +2d | 38 (73.1) |

| +3d | 9 (17.3) |

| Patients who used systemic therapy as prior treatment for ADe, n (%) | 13 (14.6) |

All data are mean (SD) unless otherwise specified

AD atopic dermatitis, BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, NRS numeric rating scale, Nx number of patients with non-missing values, n number of patients, PO-SCORAD Patient-Oriented SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, Q2W every 2 weeks

aOne patient was inadvertently enrolled into the study with an IGA of 2. The patient discontinued the study before their Week 8 visit

bCalculated from the number of subjects with a non-missing baseline value (Nx = 78)

cCalculated from the number of subjects with a non-missing baseline value (Nx = 87)

dAt baseline, investigators evaluated patients for areas of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation compared with adjacent normal skin (score of 0). Patients could have one, both, or neither lesion type. Baseline data was not collected for patients with neither lesion type. The number of participants with this lesion type was used as the denominator. Patients with multiple hypopigmented or hyperpigmented lesions at baseline were counted under the most extreme score within lesion type

e Systemic treatments included systemic corticosteroids (n = 9), mycophenolate mofetil (n = 1), oral Janus kinase inhibitors (n = 1), and phototherapy (n = 3); patients could have received more than one systemic treatment

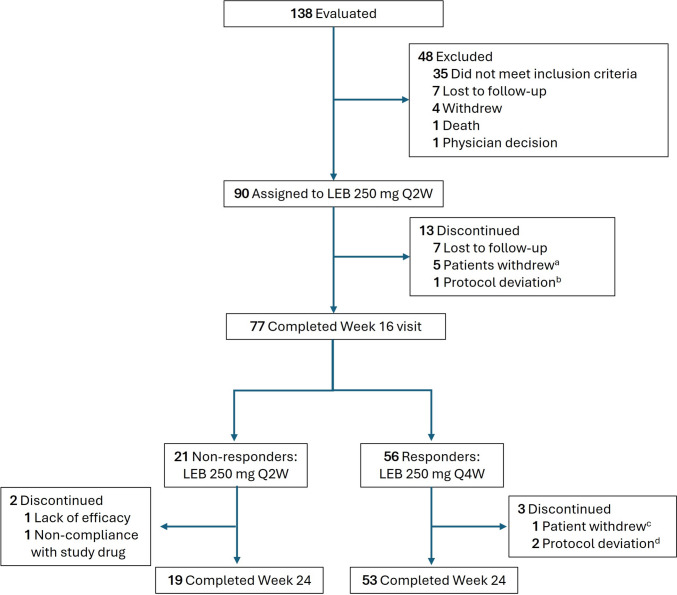

A total of 13 patients (14.4%) discontinued the study on or prior to Week 16 (Fig. 1). Reasons for discontinuation included lost to follow-up (n = 7), withdrawal by the patient (n = 5), and protocol deviation (n = 1). Among the 56 responders and 21 inadequate responders at Week 16, 72 completed Week 24. Between Weeks 16 and 24, two inadequate responders (lack of efficacy, n = 1; non-compliance with study drug, n = 1) and three responders (protocol deviation, n = 2; withdrawal by patient, n = 1) discontinued the study.

Fig. 1.

Trial flow diagram for patient disposition through Week 24. aReasons for withdrawal included concern about study procedures and perceived risks (n = 1); disinterest after informed of requirement for hepatitis testing (n = 1); change of dermatologist (n = 1); resolution of symptoms (n = 1); and patient no longer wanted to receive study drug injections (n = 1). bThis patient was an inadvertent enroller and was discontinued from the study once the sponsor discovered that they had an IGA score of 2 and EASI score < 16 at baseline. cReason for withdrawal was scheduling conflicts. dProtocol deviations included the following: one patient discontinuing from study due to prohibited medication (prednisone), and one patient did not meet inclusion criteria #4: Have chronic AD (according to American Academy of Dermatology Consensus Criteria) that has been present for ≥ 1 year before screening visit. AD atopic dermatitis, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, LEB lebrikizumab, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks

Primary and Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

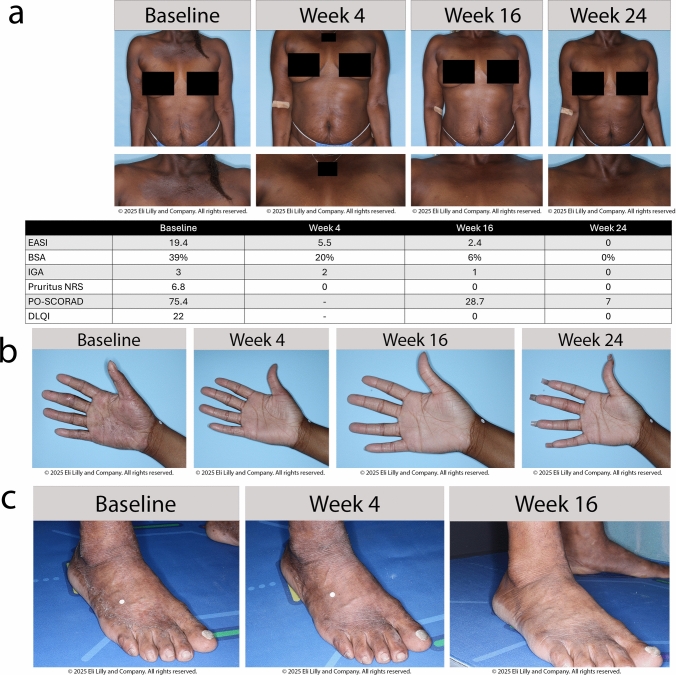

At Week 16 (number of patients with non-missing values [Nx] = 78), 69.2% of patients achieved the primary endpoint of EASI 75, which increased to 78.4% at Week 24 (Nx = 74) (Fig. 2). Among the investigator-assessed secondary endpoints at Weeks 16 and 24, 44.9% and 47.3% of patients achieved EASI 90, and 44.9% and 54.1% of patients achieved IGA 0/1, respectively. Among patients who reported Pruritus NRS and Skin Pain NRS ≥ 4 at baseline (N = 70), over half reported ≥ 4-point improvement at Week 16 (Nx = 62; 58.1% and 58.8%, respectively), which was maintained at Week 24 (Nx = 53; 60.4% and 61.4%, respectively). For patients who reported a Sleep-Loss Scale score ≥ 2 at baseline (Nx = 78), approximately one-third achieved a ≥ 2-point improvement (30.8% and 33.3% at Weeks 16 [Nx = 39] and 24 [Nx = 33], respectively). A ≥ 4-point improvement in the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was achieved by 71.7% and 72.9% of patients at Weeks 16 (Nx = 60) and 24 (Nx = 59), respectively. The primary and secondary endpoints at Weeks 16 and 24 are shown in Supplement 1, Table S3 (see ESM). Values consistent with the primary analysis were obtained using the supplemental NRI/MI imputation strategy (Fig. 2 and Supplement 1, Table S3, see ESM). Photographic representations illustrating visual treatment effects in patients are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Efficacy over time through Week 24. Where applicable, efficacy data collected at an early termination visit was mapped to the next scheduled visit. Pruritus NRS and Skin Pain NRS are based on patients who had baseline scores of ≥ 4. EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI 75 ≥ 75% improvement from baseline in EASI, EASI 90 ≥ 90% improvement from baseline in EASI, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, IGA (0,1) Investigator’s Global Assessment response of clear or almost clear, LEB lebrikizumab, MI multiple imputation, NRI non-responder imputation, NRS numeric rating scale, Nx number of patients with non-missing values, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks

Fig. 3.

Patient photos. a Visual and tabular treatment effects of lebrikizumab through Week 24 in a 50-year old systemic- and biologic-naïve Black/African American woman (Fitzpatrick skin phototype VI) with a history of AD since infancy and food allergy as her only comorbidity. The patient was a responder at Week 16 and thus received lebrikizumab 250 mg Q4W. b Visual treatment effects of lebrikizumab through Week 24 in an 18-year-old systemic- and biologic-naïve Black/African American woman (Fitzpatrick skin phototype V) with a history of AD for 12 years and no comorbidities. The patient was a responder at Week 16 and thus received lebrikizumab 250 mg Q4W. The severity of concomitant hand eczema was classified as severe by the investigator at baseline, but was no longer present at the next formal assessment, conducted at Week 24. At baseline, the EASI, IGA, and DLQI scores were 30.2, 4 (severe), and 20, respectively; at Week 24 the scores were 1.2, 1 (almost clear), and 0 c Visual treatment effects of lebrikizumab through Week 16 in a 53-year-old, systemic- and biologic-naïve Asian man (Fitzpatrick skin phototype V) with a 3-year history of AD and comorbid diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. The patient was a responder at Week 16 and thus continued lebrikizumab 250 mg Q4W. The severity of concomitant foot eczema over time is shown (no images are available for Week 24). At baseline, the EASI, IGA, and DLQI scores were 16.2, 3 (moderate), and 13, respectively, and at Week 24 they were 0, 0 (clear), and 0 AD atopic dermatitis, BSA body surface area, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI 75 ≥ 75% improvement from baseline in EASI, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, IGA (0,1) Investigator’s Global Assessment response of clear or almost clear, NRS numeric rating scale, PO-SCORAD Patient-Oriented SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, Q4W every 4 weeks

At Week 16, responders (n = 56) switched to lebrikizumab 250 mg Q4W and maintained their response at Weeks 16 and 24, respectively, for EASI 75 (94.6% and 90.7%), EASI 90 (60.7% and 63.0%), IGA 0/1 (62.5% and 72.2%), and Pruritus NRS ≥ 4-point improvement (65.9% and 68.4%). Inadequate responders at Week 16 (n = 21), who continued lebrikizumab 250 mg Q2W, had response rates increase from 0%, 0%, 0%, and 37.5% at Week 16 to 45.0%, 5.0%, 5.0%, and 40.0% at Week 24 for EASI 75, EASI 90, IGA 0/1, and Pruritus NRS ≥ 4-point improvement, respectively (Supplement 1, Fig. S3, see ESM).

Exploratory Efficacy Outcomes

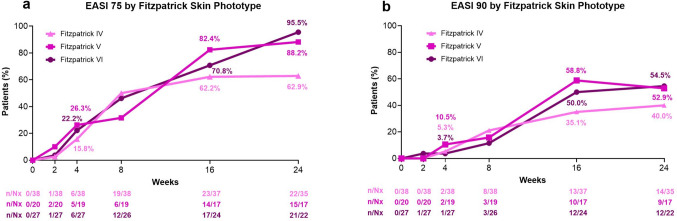

When stratified by Fitzpatrick skin phototype, 62.9% (Nx = 35), 88.2% (Nx = 17), and 95.5% (Nx = 22) of phototype IV, V, and VI patients, respectively, achieved EASI 75 at Week 24, and 40.0%, 52.9%, and 54.5% achieved EASI 90 (Fig. 4). Overall, as assessed with PDCA Derm™, 61.5% (32/52) of patients showed improvement of dyspigmentation (movement closer to but not exceeding normal skin tone) at Week 16 with the percentage remaining similar at week 24 (60.8% [31/51]). Most patients with PDCA Derm™-assessed hyperpigmented areas at baseline (Nx = 45) showed improvement at Week 24, with 64.4% demonstrating reduced hyperpigmentation. Among them, 24.4% achieved normal skin tone comparable to nearby unaffected skin. Of the patients with hypopigmented areas at baseline (Nx = 12), 25.0% showed improvement, with 16.7% achieving normal skin tone comparable to nearby unaffected skin at Week 24 (Supplement 1, Figure S4, see ESM).

Fig. 4.

EASI 75 (a) and EASI 90 (b) by Fitzpatrick skin phototype. Data shown is as observed. Where applicable, efficacy data collected at an early termination visit was mapped to the next scheduled visit. EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI 75 ≥ 75% improvement from baseline in EASI, EASI 90 ≥ 90% improvement from baseline in EASI, Nx number of patients with non-missing values

Using the PO-SCORAD™ (mean baseline score = 57.1) at Week 24 (Nx = 74), the mean (SD) percent change from baseline was − 52.1% (32.2) and the mean (SD) change from baseline was −31.3 (22.3). Regarding patient satisfaction at Week 24, 69.3% reported being mostly or completely satisfied with lebrikizumab’s ability to treat their skin condition, while five patients (6.7%) reported not being satisfied. Additional exploratory outcome details are provided in Supplement 1, Table S4 (see ESM).

Use of Concomitant Treatment

Among the 90 enrolled patients, 32 (35.6%) received at least one concomitant AD treatment through Week 24 (Supplement 1, Table S5, see ESM), with 31 (34.4%) receiving topical therapy. Topical therapies included low-potency TCS (n = 27, 30.0%), mid-potency TCS (n = 26, 28.9%), TCIs (n = 12, 13.3%), and crisaborole (n = 11, 12.2%). No high-potency TCS use was reported through Week 24. One patient used systemic therapy (prednisone) during the trial; although this met the protocol-defined criteria of rescue medication and the patient was discontinued, it was used for a non-AD-related issue.

Safety Profile

Twenty-nine patients (32.2%) reported a treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE). Most TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity; 2 (2.2%) patients reported a TEAE that was considered severe. No serious adverse event or adverse event leading to treatment discontinuation were reported through Week 24 (Table 2). Nine patients (10.0%) reported an infection, none of which were deemed opportunistic. Injection-site reaction and conjunctivitis were each reported by one patient.

Table 2.

Overview of treatment-emergent adverse events through Week 24 in the safety population

| Lebrikizumab Q2W/Q2Wa (N = 21) | Lebrikizumab Q2W/Q4Wa (N = 56) | Any lebrikizumaba (N = 90) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAEb | 10 (47.6) | 17 (30.4) | 29 (32.2) |

| Mild | 6 (28.6) | 9 (16.1) | 17 (18.9) |

| Moderate | 4 (19.0) | 6 (10.7) | 10 (11.1) |

| Severe | 0 | 2 (3.6) | 2 (2.2) |

| Serious adverse event | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAE related to study treatmentc | 1 (4.8) | 6 (10.7) | 7 (7.8) |

| AEs leading to treatment discontinuationc | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infections | 3 (14.3) | 6 (10.7) | 9 (10.0) |

| Skin infectionsd | 2 (9.5) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (3.3) |

| Potential immediatee hypersensitivity | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) |

| Injection-site reactionsf | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) |

| Keratitis cluster | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Conjunctivitis clusterf,g | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) |

| Malignancies | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AD exacerbation | 1 (4.8) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (3.3) |

| Hepatic eventsh | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

All data are n (%)

AD atopic dermatitis, AE adverse event, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, Q2W every 2 weeks, Q4W every 4 weeks, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event, ULN upper level of normal

aLebrikizumab Q2W/Q2W includes inadequate responders (patients who did not achieve IGA 0/1 and EASI 75 at Week 16); Lebrikizumab Q2W/Q4W includes responders (patients who did achieve IGA 0/1 or EASI 75 at Week 16); Any lebrikizumab includes all patients in the safety population, including 13 patients who discontinued before Week 16)

bPatients with multiple events of varying severities are counted according to the most severe event

cAs assessed by the investigator

dSkin infections included patients with pustule on right thenar eminence (moderate severity, not related to study drug, and did not lead to treatment discontinuation), impetigo (mild severity, not related to study drug, and did not lead to treatment discontinuation), and folliculitis (mild severity, assessed by investigator as related to study drug, but did not lead to treatment discontinuation)

eImmediate events occurred on the day of drug administration

fInjection-site reactions were defined using MedDRA Version 27.1 High Level Term for injection-site reactions (excluding joint-related preferred terms)

gIncludes the following preferred terms: conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis allergic, conjunctivitis bacterial, conjunctivitis viral, giant papillary conjunctivitis

hPatient with one-time elevated alanine aminotransferase (< 2× ULN) and aspartate aminotransferase (< 2× ULN) levels that were mild in severity, not related to study drug, and did not lead to treatment discontinuation

Discussion

ADmirable is the first phase IIIb trial dedicated to evaluating the efficacy of lebrikizumab in patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV, V, VI) and moderate-to-severe AD, where, at Weeks 16 and 24, patients improved across all physician-assessed and patient-reported outcomes, including skin pain and pruritus, following treatment with lebrikizumab. Additionally, upon treatment with lebrikizumab, baseline post-inflammatory hyperpigmented and hypopigmented areas trended toward normal skin tone at Week 24.

ADmirable included patients who self-reported race other than White, including but not limited to persons who self-identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander. These populations are collectively referred to as individuals with skin of color and have been reported to have a high burden of AD, including notable variations in prevalence, persistence, severity, and impact [4, 26]. By 2044, these groups are projected to constitute more than half of all Americans [27]. While these populations are heterogenous and encompass a wide range of phototypes, skin of color is most commonly defined as Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI. By focusing on populations with skin of color, we aimed to include patients who are traditionally underrepresented in research despite an urgent need driven by diagnostic challenges, uncertainty regarding treatment responses, and potential socioeconomic disparities related to access to care.

ADmirable’s results confirm and extend post-hoc analysis from lebrikizumab’s pivotal trials, ADvocate1 and ADvocate2 [20] as well as post-hoc analysis results from dupilumab’s pivotal trials [28], which demonstrated significant clinical improvement across racial and ethnic subgroups. However, in those analyses, Black or African American patients comprised fewer than 10% of the study populations, limiting the strength of subgroup conclusions and highlighting the need for dedicated studies. In ADmirable, patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes V and VI achieved the highest EASI 75 and EASI 90 response rates at Week 24—exceeding 88.2% and 52.9% for type V and 95.5% and 54.5% for type VI, respectively. While the sample sizes were relatively small, these findings underscore the similar biology and underlying mechanisms of inflammation across the spectrum of skin phototypes. Although some differences between White and non-White populations have been identified, their meaning and implications for the treatment of AD remain unclear [4]. One explanation for the finding of higher response rates in the darker skin tones could be lower use of prior systemic treatments for AD. As noted in Table 1, only 14.6% of patients in the current study reported prior use of systemic treatments, while more than half of patients in other lebrikizumab studies, with predominately White study populations, reported prior use of systemic treatment (~50–60% of patients in the pivotal phase III lebrikizumab trials [18]). They also potentially highlight noticeable disparities in the care and management of AD in patients with skin of color, which need to be addressed [27].

It is well established that one of the most burdensome AD symptoms is itching, and this holds true for patients with skin of color, with almost 90% of patients in this study having Pruritus NRS ≥ 4 at baseline. In previous trials, including ADvocate1, ADvocate2, and ADhere (which evaluated patients treated with lebrikizumab plus TCS), itching was significantly improved in lebrikizumab-treated patients as early as Week 4 [18, 29]. Similarly, in the current trial, nearly 30% of patients achieved ≥ 4-point improvement in Pruritus NRS by Week 4, and this proportion increased to nearly 50% by Week 6 (Fig. 2). These consistent findings reinforce the robust and rapid impact of lebrikizumab on itching in patients with AD, including in those with skin of color.

A defining feature of this study is its use of novel exploratory assessments. Dyspigmentation is a major concern for patients with skin of color, with dyschromia reported as the second most common diagnosis for Black patients in a hospital-based dermatology center, and can have negative psychosocial effects leading to reduced quality of life [30–32]. PDCA Derm™ was developed to provide a standardized, objective method to assess post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation in patients with skin of color and AD, supporting diagnosis, treatment, and research [23]. Although post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation is more persistent and clinically visible in patients with darker skin [33, 34], a quarter of lebrikizumab-treated patients in ADmirable with hyperpigmented areas achieved skin tone normalization, and 64.4% showed at least some lightening of the target lesion at Week 24. Interestingly, three of 45 patients experienced worsening of their hyperpigmented lesions, while four progressed to hypopigmented areas—possibly linked to labile melanocyte responses observed under inflammatory conditions [35, 36].

Overall, our results, using the PDCA Derm™ [23], build upon observations from a case report [37] and a small, open-label study of patients treated with dupilumab [38], showing improvement in hyperpigmentation of clinically non-lesional skin. Notably, post-inflammatory hypopigmentation was observed less frequently. While one-quarter of patients showed improvement towards normal skin color, the small sample size precludes meaningful analysis. The extent to which dyspigmentation improvement alleviates disease burden and enhances quality of life remains to be explored, although new questionnaires are under development to address this gap [39].

Although disease severity and symptom burden are reportedly higher in patients with AD and skin of color, patients enrolled in ADmirable had comparable disease severity—as measured by EASI and IGA—to those in ADvocate1 and ADvocate2. This may be partially due to the in-depth training provided to ADmirable investigators to improve the accuracy of disease severity assessments in patients with skin of color, which involved examples of patients with skin of color and moderate-to-severe AD. While some evidence indicates that patients with skin of color are disproportionately affected by more severe disease, the social impact of AD in this population may be more deeply rooted in the lack of access to healthcare and stigmatization related to pigmentary sequelae. Additionally, the mean BMI of patients in this trial was greater than that in lebrikizumab’s pivotal trials, a factor often associated with lower socioeconomic status [40, 41]. AD morphology is known to vary considerably across diverse patient populations—a factor that was historically underrecognized—and is a major contributor to delayed diagnosis or even underdiagnosis [4]. In ADmirable, after AD on the face and hands, the most frequently observed variants were perifollicular accentuation of AD and AD with prurigo nodules (Fig. S2, see ESM). These findings underscore the importance of recognizing diverse variations in AD morphology to improve diagnostic accuracy and optimize patient care.

No new safety findings were noted with lebrikizumab treatment. All reported events were non-serious, did not lead to discontinuation, and were mostly mild/moderate. The frequency of reported TEAEs was numerically lower than that observed in the ADvocate and ADhere studies [18, 29], supporting a favorable benefit–risk profile in this patient population.

Limitations

This trial is limited by its open-label design, the absence of a placebo control, and the relatively short treatment period. Additionally, to better reflect real-world practice, concomitant topical medications for AD were permitted and utilized by more than one-third of patients by Week 24. Moreover, the Fitzpatrick scale—originally intended to categorize a person's response to phototherapy—was not developed to evaluate skin of color. Despite these limitations, it was used in this study in the absence of other widely accepted classification systems for skin color [26, 42], an issue that is being addressed with new scales currently in development [43]. Moreover, severity assessments in patients with skin of color are nuanced; specifically, erythema may appear in a range of hues beyond red, complicating the assessment of severity. Although ADmirable investigators received training on the nuances of AD assessments in darker skin, the scoring systems used likely underestimated the actual AD severity in ADmirable’s participants, particularly due to their reliance on erythema [17, 44]. Similarly, while the development and use of the PDCA Derm™ to objectively assess patients’ hyperpigmented and hypopigmented dyspigmentation fills an important gap in existing instruments, future studies must also address patients' perceptions of these significant disease sequelae, which are not captured by the current patient-reported outcomes for patients with skin of color [40]. Specific studies are needed to determine whether treating patients with biologics can not only improve clinical signs, as demonstrated in ADmirable, but also improve patients’ perceptions of hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation—disease sequelae shown to impact quality of life for individuals with darker skin. Finally, this study was conducted exclusively at US sites, increasing the likelihood of selection bias and potentially limiting the generalizability to patients with skin of color outside the US.

Conclusions

Lebrikizumab treatment is associated with improved signs and symptoms of AD in adult and adolescent patients with skin of color and moderate-to-severe AD, while maintaining a favorable safety profile. Additionally, lebrikizumab treatment was associated with improvements in post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and quality of life, with over half of patients reporting being mostly or completely satisfied with their treatment.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors worked on behalf of all ADmirable investigators who are listed in the Supplement (Supplement 1, Table S1). Eli Lilly and Company and Almirall S.A. would like to thank the clinical trial participants and their caregivers, without whom this work would not be possible. Medical writing assistance was provided by Tyler Albright, PharmD, an employee of Eli Lilly and Company. Data analysis was provided by Avinaba Banerjee, an employee of Eli Lilly and Company. Expert review was provided by Maria Lucia Buziqui Piruzeli, an employee of Eli Lilly and Company. They did not receive compensation beyond their usual salary for their contribution to this work. Kathy Oneacre, MA, CMPP (Syneos Health, Morrisville, NC, USA) provided medical writing assistance; editorial assistance was provided by Raena Fernandes and Abbas Kassem (Syneos Health, Morrisville, NC, USA), which were funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The ADmirable clinical trial was conducted in accordance with ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The ADmirable trial protocol was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board on 17 October 2022 (IRB #: Pro00066938). Additionally, Advarra approved the study at each participating center (Supplement 1, Table S1). All investigation sites received approval from the appropriate authorized institutional review board or ethics committee. The ADmirable study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05372419).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all patients before study procedures were initiated. For patients considered to be minors, the written consent of the parent or legal guardian, as well as the assent of the minor, was obtained.

Consent to Publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Figures 3a, 3b, and 3c.

Funding and Role of the Funder/Sponsor

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Eli Lilly and Company had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Almirall, S.A. has licensed the rights to develop and commercialize lebrikizumab for the treatment of dermatology indications, including atopic dermatitis, in Europe. Lilly has exclusive rights for development and commercialization of lebrikizumab in the United States and the rest of the world outside of Europe.

Competing Interests

Andrew Alexis has received grant support (funds to institution) from Leo, Amgen, Galderma, Arcutis, Dermavant, Abbvie, Castle Advisory board/Consulting: Leo, Galderma, Pfizer, Sanofi-Regeneron, Genzyme, Dermavant, Beiersdorf, Ortho, L’Oréal, BMS, Bausch health, UCB, Arcutis, Janssen, Allergan, Almirall, Abbvie, Amgen, VisualDx, Eli Lilly and Company, Swiss American, Cutera, Cara, EPI, Incyte, Castle, Apogee, Canfield, Alphyn, Avita Medical, Genentech; has served as a speaker for Regeneron, SANOFI-Genzyme, BMS, L’Oreal, Janssen, and J&J; has received royalties from Springer, Wiley-Blackwell, Wolters Kluwer Health; and has received equipment from Aerolase. Ali Moiin has received reimbursement for travel costs from and conducted clinical trials for Eli Lilly and Company. Jill Waibel has served as a consultant, investigator, and/or on scientific advisory boards for Allergan (Consultant), Amgen (Clinical Trial), ArgenX (Clinical Trial), Bellamia (Advisory Board), Bristol Myers Squibb (Clinical Trial), Candela (Speaker, Consultant, Advisory Board), Cytrellis Biosystems (Advisory Board, Consultant, Clinical Trial), Eli Lilly and Company (Clinical Trial, Speaker), Emblation (Clinical Trial), Galderma (Clinical Trial, Consultant), Horizon (Clinical Trial), Janssen/J&J (Clinical Trial), Lumenis (Advisory Board, Consultant, Speaker), Neuronetics (Clinical Trial), Pfizer (Clinical Trial), P & G (Consultant), RegenX (Clinical Consultant, Clinical Trial, Board of Directors), Sanofi (Clinical Trial), Skinceuticals (Clinical Trial, Consultant, Advisory Board), and Shanghai Biopharma, PWB (Clinical Trial); and has received a VA Merit Grant for Amputated Veterans. Paul Wallace has served as a principal investigator, advisor and/or speaker for Abbvie, Amgen, Arcutis, Biogen, Bristol Myers, Celgene, Centocor, Cynosure, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB; and has received equipment (loan to institution) from Cynosure. David Cohen reports no financial conflicts of interest. Vivian Laquer conducts research for Abbvie, Acelyrin, Acrotech, Amgen, Argenx, Arcutis, Aslan, Biofrontera, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Cara, Dermavant, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Horizon Therapeutics, Incyte, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Padagis, Pfizer, Q32, Rapt, Sun, UCB, and Ventyx. Pearl Kwong is a principal investigator for Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, Dermavant, Incyte, Arcutis, Galderma, Novartis, Abbvie, CastleCreek Biosciences, Amgen, and UCB; a consultant/advisor for Leo, Galderma, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, Incyte, EPI Health, Novan, Verrica, BMS, Sanofi-Regeneron, UCB, and Ortho; and a speaker for Abbvie, Regeneron Sanofi, Incyte, Verrica, Sun Pharma, Ortho, L’Oréal, EPI, and Arcutis. Amber Reck Atwater is a former employee of Eli Lilly and Company. Jennifer Proper, Evangeline Pierce, Christopher Schuster, Maria Silk, Sreekumar Pillai, and Maria Jose Rueda are employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. Angela Moore has received research grants or honoraria from Abbvie, Acrotech, Arcutis, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Cara, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen J&J, Pfizer, Rapt, and Sanofi-Regeneron.

Authors’ Contribution

A. Alexis has contributed to conception of the study and interpretation of the data. A. Moiin has contributed to conception of the work. A. Moore, J. Waibel, and P. Wallace have contributed to acquisition and interpretation of data. D. Cohen and V. Laquer have contributed to acquisition of data. P. Kwong has contributed to interpretation of data. A. Atwater, M. Silk, E. Pierce, S. Pillai, and M.J. Rueda have contributed to study conception, design, analysis, and data interpretation. J. Proper has contributed to study analysis and interpretation. C. Schuster has contributed to data interpretation. All authors contributed to the drafting or critical review of the manuscript and give final approval of the manuscript.

Prior Meeting Presentation

Initial baseline characteristics were presented at Maui Derm for Dermatologists, 22 January 2024, Maui, USA. An interim analysis of the results was presented at the American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting, 10 March 2024, San Diego, USA. Primary results were presented at the Fall Clinical Dermatology Conference, 24 October 2024, Las Vegas, USA. The 24-week results were presented at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis (RAD) Conference 2025, June 7, 2025, Nashville, USA.

Data Availability

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:345–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Kim BE, Leung DYM. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis: clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40:84–92. 10.2500/aap.2019.40.4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rerknimitr P, Otsuka A, Nakashima C, et al. The etiopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: barrier disruption, immunological derangement, and pruritus. Inflamm Regen. 2017;37:14. 10.1186/s41232-017-0044-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quan VL, Erickson T, Daftary K, et al. Atopic dermatitis across shades of skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24(5):731–51. 10.1007/s40257-023-00797-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverberg JI. Racial and ethnic disparities in atopic dermatitis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2015;4(1):44–8. 10.1007/s13671-014-0097-7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czarnowicki T, He H, Krueger JG, et al. Atopic dermatitis endotypes and implications for targeted therapeutics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):1–11. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexis A, Woolery-Lloyd H, Andriessen A, et al. Insights in skin of color patients with atopic dermatitis and the role of skincare in improving outcomes. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21(5):462–70. 10.36849/jdd.6609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price KN, Hsiao JL, Shi VY. Race and ethnicity gaps in global hidradenitis suppurativa clinical trials. Dermatology. 2021;237(1):97–102. 10.1159/000504911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen V, Akhtar S, Zheng C, et al. Assessment of changes in diversity in dermatology clinical trials between 2010–2015 and 2015–2020: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(3):288–92. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croce EA, Levy ML, Adamson AS, et al. Reframing racial and ethnic disparities in atopic dermatitis in Black and Latinx populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(5):1104–11. 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunner PM, Guttman-Yassky E. Racial differences in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(5):449–55. 10.1016/j.anai.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottlieb S, Madkins K, Lio P. An Updated Scoping Review of Disparities in Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025. 10.1111/pde.15914. (Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40166858). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):687–90. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(1):194–6. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibraheim MK, Gupta R, Dao H, et al. Evaluating skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: data from a national survey. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40(2):228–33. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtti A, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Representation of skin color in dermatology-related Google image searches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(3):705–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao CY, Wijayanti A, Doria MC, et al. The reliability and validity of outcome measures for atopic dermatitis in patients with pigmented skin: a grey area. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1(3):150–4. 10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, et al. Two phase 3 trials of lebrikizumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(12):1080–91. 10.1056/NEJMoa2206714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blauvelt A, Thyssen JP, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: 52-week results of two randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188(6):740–8. 10.1093/bjd/ljad022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexis A, Ardern-Jones M, Chovatiya R, et al. Lebrikizumab demonstrates significant efficacy versus placebo across racial and ethnic subgroups in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2024;190(Suppl 2):ii20–1. 10.1093/bjd/ljad498.024. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):338–51. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexis A, Pierce E, Cohee A, et al. Assessing post-inflammatory pigmentation in atopic dermatitis: reliability of the PDCA-Derm™. J Skin. 2025;9(1):s514. 10.25251/skin.9.supp.514. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stalder JF, Barbarot S, Wollenberg A, et al. Patient-Oriented SCORAD (PO-SCORAD): a new self-assessment scale in atopic dermatitis validated in Europe. Allergy. 2011;66(8):1114–21. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faye O, Meledie N’Djong AP, Diadie S, et al. Validation of the Patient-Oriented SCORing for Atopic Dermatitis tool for black skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(4):795–9. 10.1111/jdv.15999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis DMR, Drucker AM, Alikhan A, et al. Executive summary: Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with phototherapy and systemic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90(2):342–5. 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.08.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narla S, Heath CR, Alexis A, et al. Racial disparities in dermatology. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(5):1215–23. 10.1007/s00403-022-02507-z. (Ref #8 in this: Bureau UC. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population. In: Bureau UC, ed2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexis AF, Rendon M, Silverberg JI, et al. Efficacy of Dupilumab in Different Racial Subgroups of Adults With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis in Three Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(8):804–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simpson EL, Gooderham M, Wollenberg A, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial (ADhere). JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(2):182–91. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.5534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaowattanapanit S, Silpa-Archa N, Kohli I, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: a comprehensive overview: Treatment options and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):607–21. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80(5):387–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maymone MBC, Neamah HH, Wirya SA, et al. The impact of skin hyperpigmentation and hyperchromia on quality of life: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):775–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor S, Grimes P, Lim J, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13(4):183–91. 10.2310/7750.2009.08077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mar K, Maazi M, Khalid B, et al. Prevention of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in skin of colour: a systematic review. Australas J Dermatol. 2025;66(3):119–26. 10.1111/ajd.14432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markiewicz E, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Mammone T, et al. Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in dark skin: molecular mechanism and skincare implications. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:2555–65. 10.2147/CCID.S385162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papa CM, Kligman AM. The behavior of melanocytes in inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 1965;45(6):465–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grayson C, Heath CR. Dupilumab Improves Atopic Dermatitis and Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Patient With Skin of Color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(7):776–8. 10.36849/JDD.2020.4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahn HJ, Shin MK. Improvement of Nonlesional Skin Tone and Skin Barrier in Severe Atopic Dermatitis after Dupilumab Treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2023;2023:6218587. 10.1155/2023/6218587. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartford C, Alexis A, Wang Z, et al. Development of novel patient-reported outcome instruments to assess atopic dermatitis-associated dyspigmentation and xerosis in patients with skin of colour. Br J Dermatol. 2025;192(5):863–73. 10.1093/bjd/ljae494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgenstern M, Sargent JD, Hanewinkel R. Relation between socioeconomic status and body mass index: evidence of an indirect path via television use. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(8):731–8. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anekwe CV, Jarrell AR, Townsend MJ, et al. Socioeconomics of obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(3):272–9. 10.1007/s13679-020-00398-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105(2):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dadzie OE, Sturm RA, Fajuyigbe D, et al. The Eumelanin Human Skin Colour Scale: a proof-of-concept study. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187(1):99–104. 10.1111/bjd.21277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(5):920–5. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.