Abstract

Background

Glycogen storage disease type 1b (GSD 1b) is an ultra-rare disease worldwide, whereas in Serbia it has an unexpectedly high prevalence. GSD 1b is the result of variants in the SLC37A4 gene and reduced function of the enzyme glucose 6 phosphate translocase (G6PT). In addition to the classic symptoms of GSD 1a, patients with GSD 1b have neutropenia and impaired neutrophil function.

Methods

The genotype and clinical profile were analyzed in 35 patients, 26 of whom were children. In all patients, pathogenic variants in the SLC37A4 gene were confirmed using Sanger or next-generation sequencing (NGS). Eight different variants were found. The following clinical data were analyzed: age at diagnosis, first symptoms of GSD 1b, severity of intestinal symptoms, lowest neutrophil count, mean hemoglobin value, height, body mass index (BMI), and quality of life. Patients were classified into four groups based on the severity of their intestinal symptoms.

Results

In our study 30 patients received empagliflozin therapy. Our data are comprised of information from a total of 62 treatment years and include self-reported quality-of-life surveys before and during empagliflozin therapy. The average age at which empagliflozin was introduced in pediatric patients was 8.5 years, with the youngest two patients, both female, starting SGLT2 inhibitor therapy at the age of two.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that empagliflozin therapy significantly improves neutropenia recovery by reducing the frequency of recurrent infections and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-like symptoms. This improvement was demonstrated by a marked reduction in skin and mucosal infections, particularly oral ulcers, as well as an increase in hemoglobin levels and overall stature.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40291-025-00795-5.

Key Points

| Clinical history and genotype-phenotype correlations of 35 patients with GSD 1b confirmed the importance of early diagnosis and early treatment. |

| Empagliflozin therapy appears to enhance neutropenia recovery by reducing the number of recurrent infections and inflammatory bowel disease-like symptoms. |

Introduction

Glycogen storage disease type 1b (GSD 1b) is an ultra-rare inborn error of carbohydrate metabolism caused by pathogenic variants in SLC37A4, leading to reduced glucose-6-phosphate translocase function. Clinically and biochemically, it resembles GSD 1a, resulting from G6PC variants [1–4]. Both are autosomal recessive disorders characterized by impaired glucose release during fasting and glycogen accumulation, primarily in the liver and kidneys.

The clinical features of GSD 1 include hepatomegaly, nephromegaly, doll-like facial appearance, and metabolic abnormalities such as hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, metabolic acidosis, and hyperlactatemia. Further complications include short stature and osteoporosis. Unlike GSD 1a, GSD 1b is marked by neutropenia and impaired neutrophil function, resulting in frequent infections and inflammatory bowel-like (IBD-like) disease in approximately 70% of patients [1, 5–7]. Neutropenia in GSD 1b is attributed to the accumulation of 1,5-anhydroglucitol-6-phosphate (1,5-AG6P) in neutrophils, which disrupts glycolysis, their primary energy source. Under normal physiological conditions, 1,5-AG6P is transported to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and dephosphorylated by G6PC. In GSD 1b, this process is impaired, resulting in intracellular accumulation and subsequent neutrophil dysfunction [8].

Management of GSD1b includes both dietary and pharmacological interventions [1, 5, 9]. Nutritional therapy focuses on frequent meals with controlled macronutrient composition, particularly uncooked cornstarch, to maintain glucose homeostasis. Pharmacological treatments for metabolic abnormalities such as hyperlipidemia and hyperuricemia are tailored based on individual metabolic control [1]. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) has been used to enhance neutrophil counts, but its effects are often transient [10, 11]. More recently, SGLT2 inhibitors such as empagliflozin have demonstrated the ability to reduce 1,5-AG6P levels, thereby restoring neutrophil function and alleviating infections and IBD-like symptoms [12, 13].

The global incidence of GSD 1 (including both type 1a and type 1b) is estimated at approximately 1:100,000 live births, with an 80%:20% ratio of GSD 1a to GSD 1b [1]. Glycogen storage disease 1b is considered an ultra-rare disease with an incidence of approximately 1 in 500,000 live births [14]. However, in Serbia, available data suggest a markedly higher incidence of 1 in 60,461 live births, with an unexpected 26%:74% ratio of GSD 1a to GSD 1b, significantly divergent from global trends [15].

This study presents a large cohort of GSD 1b patients treated at the Institute for Mother and Child Health Care of Serbia, offering a comprehensive analysis of clinical manifestations and evaluating the therapeutic impact of empagliflozin. It is divided into two phases: pre- and post-empagliflozin therapy, assessing treatment outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The inclusion criteria for this study required a molecular genetic diagnosis of GSD 1b, confirmed by Sanger or next-generation sequencing [15]. Variant interpretation followed a standardized approach, regardless of sequencing method [15, 16]. This study was approved by the Ethics Approval Committee of the Mother and Child Health Care Institute of Serbia “Dr Vukan Cupic” in Belgrade, Serbia (8/2025 and 31/2020).

Genotype and clinical profiles were assessed in 35 patients from 29 unrelated families and three sibling pairs, with no consanguinity. Patients under 18 years of age at the time of the study were classified as children (n = 26), while the remaining nine were adults. In order to clearly display data on our patients and highlight clinical and laboratory details, we created four tables. Patients were categorized into four groups based on intestinal symptom severity: severe IBD-like manifestations (Group 1), severe unresolved symptoms without histopathology confirmation (Group 2), milder gastrointestinal symptoms (Group 3), and asymptomatic patients (Group 4).

Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) below 1500 cells/µL [17]. All patients experienced at least one episode of ANC < 500. A total of 30 patients received the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin. At the initiation of empagliflozin therapy, the G-CSF treatment was discontinued in all patients. Adult patients and parents rated quality of life on a scale from 1 to 10, at baseline and at least 1 year post-therapy. Patients followed a well-established GSD1 management protocol adhering to published clinical guidelines [1]. Compliance was monitored through metabolic control, including assessments of growth, liver and kidney size (via ultrasound), kidney function, and laboratory testing (blood glucose, blood count, acid-base status, uric acid, lactic acid, and lipid profiles; data not shown). Neutrophil count and hemoglobin levels were recorded at each follow-up. G-CSF usage was determined by infection frequency and severity. Patients with good metabolic control attended three scheduled annual check-ups; while others had individualized follow-up schedules based on clinical and laboratory findings. Severe hypoglycemic episodes were defined as events involving convulsions or loss of consciousness.

Statistical Analysis

Data were processed using dplyr (1.1.4) and tidyr (1.3.1) in R, with figures created using ggplot2 (3.5.1) and patchwork (1.3.0). Statistical analysis was performed with p-values < 0.05 considered significant. ANOVA, t-tests, Wilcoxon signed-rank, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to analyze ANC, hemoglobin, and quality-of-life changes before and during therapy. Normality and variance homogeneity were assessed using Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests.

Results

Genotype

Among our 35 patients, spanning 32 families, we identified eight distinct variants. The most common variant in the SLC37A4 gene in the Serbian population is c.81T>A, detected in 25 patients (71.4% of the cohort). Table 1 presents the genotype spectrum of our patients. The largest group consisted of 11 patients who are homozygous for the c.81T>A variant. This variant was also found in 14 patients in a heterozygous form. The second most frequent variant was c.1042_1043delCT deletion, observed in 17 patients (48.6%), including six homozygotes [15].

Table 1.

Genotype spectrum of Serbian GSD 1b patients

| Genotype (groups) | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| c.81T>A/c.81T>A | 11 |

| c.81T>A/c.1042_1043delCT | 7 |

| c.1042_1043delCT/c.1042_1043delCT | 6 |

| c.81T>A/c.785G>A | 3 |

| c.248G>A/c.1042_1043delCT | 2 |

| c.81T>A/c.571C>T | 2 |

| c.785G>A/c.1042_1043delCT | 1 |

| c.81T>A/c.404G>A | 1 |

| c.81T>A/c.1108_1109delCT | 1 |

| c.162C>A/c.1042_1043delCT | 1 |

Study of Clinical History of 35 Glycogen Storage Disease Ttype 1b (GSD 1b) Patients

Age of Diagnosis and Initial Symptoms

The median age for our cohort was 16.8 months. Over the past decade, six patients were diagnosed at a significantly later age. Recurrent infections were the first symptom observed in 60% of children (15 of 26). Interestingly, 28% of children (7 of 26) were initially investigated due to abdominal distension which later led to detection of hepatomegaly (Table 2). Only 12% (3 of 26) exhibited hypoglycemia as the first manifestation of the disease (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of GSD 1b patients with genotype prior to SGLT2 inhibitor therapy

| Patient number | Year of birth | MUT 1 | MUT 2 | Age at diagnosis (month) | Lowest ANC | First symptoms of GSD 1b | Intestinal symptoms (Groups 1, 2, 3, 4) | Mean Hb level (g/L) | Average number of annual hospitalizations due to infections | Body height expressed in percentiles (P) | BMI (kg/m2) and expressed in percentiles (P) | Treatment with G-CSF | Specificities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2015 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 12 | 220 | Infections | 2 | 100 | 2 | P50 |

14.83 P25 |

2 µg/kg 3 times a week | Streptococcal sepsis |

| 2. | 2016 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 10 | 370 | Hypoglycemia | 2 | 100 | 2 | P10 |

14.47 P25 |

3 µg/kg 3 times a week | |

| 3. | 2009 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 60 | 300 | Infections | 3 | 120 | 1 | P50 |

23.7 P95 |

2 µg/kg 3 times a week | Normal stature |

| 4. | 2014 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 18 | 440 | Abdominal distension + hepatomegaly | 2 | 88 | 2 | P10 |

14.88 P25 |

no | |

| 5. | 2011 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 12 | 480 | Infections | 2 | 105 | 3 | P3 |

16.7 P25 |

2 µg/kg 3 times a week | Recurrent arthritis of large joints |

| 6. | 2015 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 78 | 420 | Infections | 3 | 100 | 0 | P3-P10 |

14.97 P25 |

no | GH therapy, prior to diagnosis |

| 7. | 2017 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 48 | 290 | Abdominal distension + hepatomegaly | 3 | 105 | 0 | ↓P3 |

15.04 P50 |

no | GH therapy, prior to diagnosis |

| 8. | 1984 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 52 | 2 | 2 µg/kg twice a week | Severe pancreatitis | ||||||

| 9. | 1999 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 3 | 2 | 2 µg/kg twice a week | Very short stature | ||||||

| 10. | 1991 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 3 | 3 | No | Normal stature, two children | ||||||

| 11. | 1999 | c.81T>A | c.81T>A | 18 | 2 | 2 µg/kg twice a week | |||||||

| 12. | 2014 | c.81T>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 4 | 380 | Infections | 3 | 120 | 2 | P50 |

19.74 P95 |

No | Omphalitis |

| 13. | 2012 | c.81T>A | c.571C>T | 53 | 420 | Abdominal distension + hepatomegaly | 3 | 124 | 0 | ↓ P3 |

18.3 P50 |

No | Without infections |

| 14. | 2014 | c.81T>A | c.571C>T | 29 | 370 | Abdominal distension + hepatomegaly | 3 | 118 | 0 | P3 |

15.7 P50 |

No | Without infections |

| 15. | 2010 | c.81T>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 10 | 200 | Infections | 2 | 80 | 3 | ↓P3 |

18.8 P75 |

2 µg/kg twice a week | Severe infections during first year of life |

| 16. | 2012 | c.81T>A | c.1108_1109delCT | 6 | 240 | Infections | 3 | 100 | 0 | P25 |

16.24 P50 |

2 µg/kg twice per week | |

| 17. | 2013 | c.81T>A | c.404G>A | 14 | 400 | Abdominal distension + hepatomegaly | 3 | 96 | 3 | P10 |

17.0 P75 |

3 mg/kg 3 times a week | Recurrent arthritis of large joint, anaphylaxis to various drugs |

| 18. | 2014 | c.81T>A | c.785G>A | 7 | 480 | Infections | 3 | 100 | 1 | P50 |

18 P25 |

3 µg/kg twice per week | Pseudomonas infection of the tongue |

| 19. | 2010 | c.81T>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 18 | 340 | Abdominal distension + hepatomegaly | 2 | 85 | 1 | P3 |

21.2 P50 |

3 µg/kg twice a week | |

| 20. | 2008 | c.81T>A | c.785G>A | 9 | 150 | Abdominal distension + hepatomegaly | 2 | 100 | 1 | P25–P50 |

28.1 P99 |

2 µg/kg twice a week | |

| 21. | 2008 | c.81T>A | c.785G>A | 12 | 200 | Infections | 1 | 80 | 1–2 | P25 |

14.5 P3 |

3 µg/t3 times a week | IBD like, abdominal surgery |

| 22. | 2020 | c.81T>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 18 | 490 | Asymptomatic hypoglycemia | 3 | 100 | 1 | P3 |

18.87 P75 |

No | |

| 23. | 2009 | c.81T>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 10 | 400 | Infections | 2 | 110 | 1 | ↓P3 |

17.1 P50 |

2 µg/kg twice a week | Recurrent arthritis of large joints Partial GH deficiency |

| 24. | 2005 | c.81T>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 18 | 1 | 2 µg/kg 3 times a week | IBD like | ||||||

| 25. | 1991 | c.81T>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 12 | 1 | 2 µg/kg 3 times a week | Very short stature, one pregnancy | ||||||

| 26. | 2019 | c.1042_1043delCT | c.1042_1043delCT | 6 | 360 | Infections | 4 | 100 | 2–3 | P25 |

14.66 P50 |

No | Without intestinal manifestations |

| 27. | 2011 | c.1042_1043delCT | c.1042_1043delCT | 7 | 450 | Infections | 1 | 50 | 3–4 | P3 |

11.05 P3 |

3 µg/kg 3 times a week | Sever failure to thrive, anemia, IBD like |

| 28. | 2014 | c.1042_1043delCT | c.1042_1043delCT | 5 | 220 | Infections | 1 | 95 | 1 | P3 |

16.32 P50 |

3 µg/kg 3 times a week | IBD like |

| 29. | 2005 | c.1042_1043delCT | c.1042_1043delCT | 10 | 300 | Symptomatic hypoglycemia | 2 | 70 | 3–4 | ↓P3 | 3 µg/kg 3 times a week | Very bad metabolic control | |

| 30. | c.1042_1043delCT | c.1042_1043delCT | 3 | 300 | Infections | 1 | 90 | 3–4 | ↓P3 | 2 µg/kg twice a week | Died at the age of 14 years | ||

| 31. | 2000 | c.1042_1043delCT | c.1042_1043delCT | 6 | 1 | 3 µg/kg 3 times a week | Most severe IBD lost from follow up | ||||||

| 32. | 2011 | c.785G>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 6 | 200 | Infections | 2 | 84 | 3 | ↓↓P3 |

16.0 P50 |

2 µg/kg twice a week | Severe hypoglycemic crises with transient hemiparesis |

| 33. | 2015 | c.162C>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 6 | 300 | Infections | 2 | 90 | 2 | P3 |

15.98 P50 |

3 µg/kg 3 times a week | |

| 34. | 1985 | c.248G>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 3 | 2 | 1 µg/kg twice a week | Low high | ||||||

| 35. | 1999 | c.248G>A | c.1042_1043delCT | 3 | 1 | 1 µg/kg twice a week | IBD like, arthritis |

Intestinal symptoms in four groups: Group 1 (confirmed severe IBD-like changes through histopathological examination after biopsy and the existence of symptoms from groups 2 and 3 is also implied); Group 2 (severe failure to thrive with diarrhea and perianal fistula and abscess+ symptoms from group 3); Group 3 (other symptoms: recurrent diarrhea, constipation, abdominal discomfort, anemia); Group 4 (without intestinal symptoms)

MUT1 first mutation in SLC37A4 gene, MUT2 second mutation in SLC37A4 gene, ANC absolute neutrophil count, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, GH growth hormone, Hb hemoglobin, BMI body mass index, C-GSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

Neutropenia, Infections, and Immune Disorders

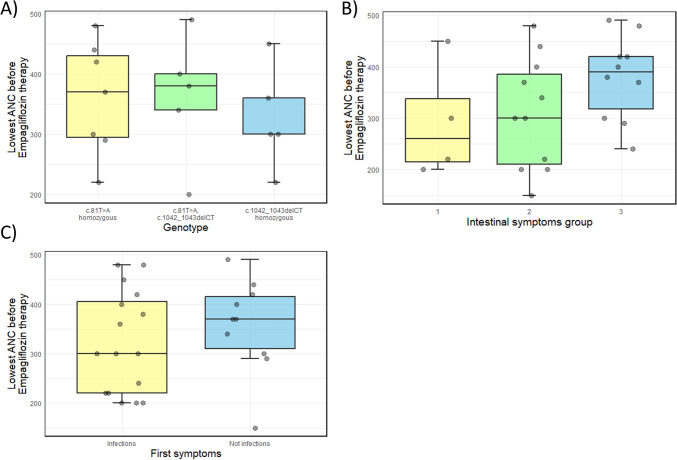

Neutropenia was documented in all patients at some point (Table 2), however, this was not consistently present in all cases, nor was it detected during every outpatient visit. During infections, neutropenia was not registered among the majority of patients. We assessed the lowest ANC prior to empagliflozin therapy in relation to genotype, intestinal symptoms, and type of first symptoms (Fig. 1), but found no statistically significant correlations. In our cohort of patients, there is no statistically significant difference when correlating the lowest absolute neutrophil with different genotype groups (ANOVA, p-value 0.79), nor in correlations with severity of intestinal symptoms (ANOVA, p-value 0.20), nor in relation to the type of the first symptom recorded in a patient (independent t-test, p-value 0.39).

Fig. 1.

Lowest absolute neutrophil count before beginning empagliflozin therapy in GSD 1b patients in Serbia in relation to A most frequent genotypes, B severity of intestinal symptoms, and C type of the first symptoms. The gray dots represent measurements for each patient. A Boxplot (median, 25–75th percentile, 1.5 interquartile range (IQR)) of lowest ANC for the three most common SLC37A4 genotypes in Serbian GSD 1b patients shows no statistically significant difference upon ANOVA (p-value = 0.79) (B) Boxplot (median, 25–75th percentile, 1.5 IQR) of lowest ANC for three groups of Serbian GSD 1b patients with different severity of intestinal symptoms (groups 1, 2, and 3) shows no statistically significant difference upon ANOVA (p-value = 0.20). C Boxplot (median, 25–75th percentile, 1.5 IQR) of lowest ANC for two groups of Serbian GSD 1b patients (in which infections were and were not the first symptom) shows no statistically significant difference upon independent samples t-test analysis (p-value = 0.39)

Skin and mucosal infections were most often reported in children. We evaluated the age of first infections in 33 of 35 patients (Table 3). In 72% of patients considering only those with recurrent infections, the first infections occurred during the first year of life (Table 3). Two sisters (Table 2, patients 13 and 14) who had no history of frequent infections were excluded. Perianal abscesses or fistulas occurred in 14% of cases (Table 2, patients 2, 21, 25, 28, 31). More than half had recurrent otitis in infancy, whereas respiratory infections were less frequent. One patient experienced a Pseudomonas tongue infection (Table 2, patient 18), while another suffered severe streptococcal sepsis at age three (Table 2, patient 1).

Table 3.

Age at onset of first infections

| Age at onset | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| During the first year of life | 24 |

| In the second year of life | 7 |

| After the second year of life | 2 |

Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (G-CSF) Therapy

Before starting empagliflozin therapy, 25% of patients had never received G-CSF. Four declined treatment (Table 2, patients 4, 10, 12, 26), two had neutropenia without infections (Table 2, patients 13, 14), and three were diagnosed when empagliflozin was introduced (patients 6, 7, 22). Most received an initial G-CSF dose of 1 µg/kg/day [10]. While treatment transiently reduced infection [10, 11], all patients developed splenomegaly, although no malignancies were observed.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

According to the specified criteria (see Sect. 2, Materials and Methods) for the division of patients into groups based on the severity of gastrointestinal manifestations, there were eight patients in group 1 who presented with the most severe gastrointestinal symptoms (22.9%), while 15 patients in group 2 (42.9%) with severe symtoms without histopatology confirmations, 11 patients in group 3 (31.4%) with milder gastrointestinal symptoms, and one patient in group 4 reported no gastrointestinal symptoms. This single patient remained asymptomatic until the age of two, when treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors was initiated due to infections (Table 2, patient number 26). Intestinal biopsy is an invasive procedure and was only performed in the most challenging cases when considering specific IBD therapy. Patients in group 1 were treated with G-CSF and specific IBD therapy (mesalazine), with some also receiving enteral nutrition. Groups 2 and 3 primarly received G-CSF and symptomatic therapy occasionally, such as probiotics. While no significant improvements were observed in children from group 1, those in groups 2 and 3 experienced notable fluctuations in the frequency and severity of gastrointestinal complaints.

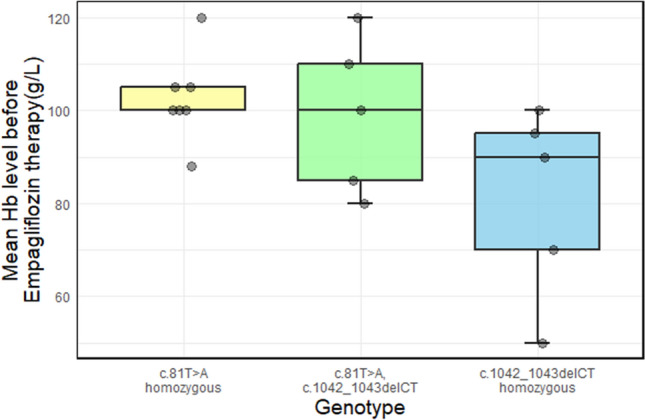

Anemia

Anemia was present in most of our patients. Table 2 presents the mean hemoglobin values of our patients with GSD 1b prior to empagliflozin therapy. Additionally, we analyzed the correlation between hemoglobin values and the most common genotypes (Fig. 2). Our findings indicate that patients homozygous for c.1042_1043delCT exhibited a trend toward lower hemoglobin levels compared to compound heterozygotes (c.81T>A/c.1042_1043delCT) and those homozygous for c.81T>A. Statistical analysis showed a trend toward significance (ANOVA, p = 0.081) for lower hemoglobin levels in patients with the c.1042_1043delCT genotype.

Fig. 2.

Mean hemoglobin level before beginning empagliflozin therapy in GSD 1b patients in Serbia. The gray dots represent measurements for each patient. The boxplot (median, 25–75th percentile, 1.5 interquartile range (IQR)) of mean hemoglobin level before therapy for the three most common SLC37A4 genotypes in Serbian GSD 1b patients shows statistical trend upon ANOVA test with p-value of 0.081

Height

Most children in our study (21 out of a total of 26) exhibited short stature, falling below the 50th percentile (81%) (Table 2). Among these the majority (14 children) were at or below the third percentile, accounting for 66% of this subgroup. Overall, in the total cohort, 53.4% of children were at or below the third percentile.

One boy (Table 2, patient 23) was referred to an endocrinologist at his parents’ request due to concerns about his short stature, despite maintaining relatively good metabolic control of the disease. He was diagnosed with partial growth hormone deficiency, prompting the initiation of growth hormone therapy. However, after 3 years of treatment, no desired therapeutic effects were observed. Similarly, two sisters (Table 2, patients 6 and 7) had undergone 2 years of growth hormone therapy before their GSD 1b diagnosis, but no significant growth acceleration was achieved.

Among the nine adults in our study, only one woman (Table 2, patient number 10) was not classified as having short stature.

Hypoglycemia

The majority of patients (33 of 35) did not show serious symptoms when blood sugar levels fell below 3.3–2 mmol/l. About 30% reported increased feelings of hunger, anxiety, and weakness. Two children exhibited severe symptomatic hypoglycemia (Table 2, patients 29 and 32).

Effect of SGLT2 Inhibitor Therapy in 30 GSD 1b Patients

We initiated therapy with the SGLT2 inhibitor, empagliflozin, in patients for GSD 1b patients at the beginning of 2020. Out of 35 patients, 30 began empagliflozin therapy. Within the treated group, 22 children and six adults were on empagliflozin for over a year (see Table 4). One girl (Table 2, patient 18) was on therapy for only 3 months and is excluded from our long-term data analysis. In total, nine patients received therapy for 1–2 years, 18 for 2–3 years, and 2 for over 3 years, cumulatively accounting for 62 treatment years. Our subsequent analysis focused solely on those patients who were on therapy for more than 1 year. In children, the average age at initiation was 8.5 years, with the two youngest patients (both girls) starting at 2 years of age. The empagliflozin dose ranged from 0.1 to 0.44 mg/kg (see Table 4), with a maximum daily dose of 15 mg administered to a girl with severe intestinal manifestations and anemia (Tables 2 and 4, patient 27). Dose adjustments were made based solely on clinical observations including the frequency and severity of infections, the presence of oral ulcers as a sensitive clinical indicator, and the degree of improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and anemia.

Table 4.

Overview of patients during empagliflozin therapy

| Patient number | Introduction of empagliflozin | Duration of empagliflozin therapy years/dosage (mg/kg/day) | Body height expressed in percentiles (P) | BMI (kg/m2) and expressed in percentiles (P) | Mean Hb (g/L) | Specificities during therapy with empagliflozin | Introduction of glycosade (yes/no) | Quality of life before/during empagliflozin therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Yes | 1.5 /0.13 | P50 |

16.8 P50 |

113 | Yes* | 4/9 | |

| 2. | Yes | 2.5/0.32 | P10-P25 |

16.0 P50 |

125 | Yes | 3/9 | |

| 3. | Yes | 1.5/0.15 | P75 |

28.3 P97 |

140 | Yes* | 5/9 | |

| 4. | Yes | 3/0.3 | P25 |

15.6 P25 |

115 | Yes | 3/9 | |

| 5. | Yes | 2/0.18 | P3 |

23.8 P85 |

115 | Arthritis still observed | No | 3/8 |

| 6. | Yes | 1.5/0.35 | P3-P10 |

16.9 P50 |

120 | Yes | 3/9 | |

| 7. | Yes | 1.5/0.36 | P3 |

15.1 P50 |

113 | Yes | 3/8 | |

| 8. | Yes | 2/0.15 | Yes | 5/9 | ||||

| 9. | Yes | 1/0.2 | Yes | 4/8 | ||||

| 10. | No | – | Yes | |||||

| 11. | Yes | 2/0.2 | Yes | 5/9 | ||||

| 12. | Yes | 1/0.15 | P25–P50 |

18.74 P50 |

No | 5/9 | ||

| 13. | No | – | – | Yes | ||||

| 14. | No | – | – | Yes | ||||

| 15. | Yes | 3/0.23 | ↓P3 |

20.3 P75 |

114 | Yes | 3/9 | |

| 16. | Yes | 1.5/0.3 | P50 |

17.32 P50 |

120 | Yes | 5/8 | |

| 17. | Yes | 4 /0.27 | P50 |

18.9 P75 |

115 | Arthritis still observed | Yes | 3/10 |

| 18. | Yes | 3 months/0.27 | She gained 5 kg in 1 month | Yes* | ||||

| 19. | Yes | 2/0.16 | P3 |

20.7 P50 |

105 | No | 5/9 | |

| 20. | Yes | 2/0.16 | P25 |

27.02 P97 |

122 | No | 5/8 | |

| 21. | Yes | 3/0.15 | P50-P75 |

25.38 P85 |

125 | He gained 15kg in 3 months | 3/10 | |

| 22. | Yes | 1.5/0.2 | P10 |

17.7 P50 |

132 | No | 4/9 | |

| 23. | Yes | 3/0.15 | ↓P3 |

20.2 P50 |

128 | Arthritis still observed | Yes | 3/8 |

| 24. | Yes | 2/0.22 | Yes | 4/8 | ||||

| 25. | Yes | Stopped during pregnancy | Yes | – | ||||

| 26. | Yes | 2.5/0.29 | P50 |

17.14 P75 |

120 | No | 3/9 | |

| 27. | Yes | 2/0.44 | P3 |

18.02 P50 |

113 | Severe hypoglycemic crisis at the beginning of Empa therapy due to starvation | Yes | 2/9 |

| 28. | Yes | 2.5/0.18 | P25–P50 |

20.09 P85 |

115 | He gained 13 kg in three month, only child with ANC up to 1500 on all routine checks | Yes | 2/10 |

| 29. | Yes | 2.5/0.1 | ↓P3 | 100 | Developmental delay is the same, but no infections | No | 3/7 | |

| 30. | No | – | – | – | ||||

| 31. | No | – | – | – | ||||

| 32. | Yes | 2.5/0.1 | ↓P3 |

15.5 P25 |

105 | Yes | 4/9 | |

| 33. | Yes | 3/0.3 | P25 |

14.9 P25 |

125 | Severe hypoglycemic crisis at the beginning of therapy due to starvation, but gained 5 kg in few month | Yes* | 3/9 |

| 34. | Yes | 3/0.27 | Arthritis still observed | Yes | 5/9 | |||

| 35. | Yes | 3.5/0.13 | Yes | 5/9 |

Clinical improvement was evident in most patients within a few weeks of commencing empagliflozin therapy. Most initially received two daily doses, later transitioning to a single daily dose while maintaining the total daily dosage. Approximately 60% of patients began empagliflozin therapy in the hospital. Two children experienced severe symptomatic hypoglycemia at the start of empagliflozin therapy due to infection, starvation, or enterocolitis (Tables 2 and 4, patients 32 and 33). All patients undergoing empagliflozin treatment exhibited glycosuria, though measurements were discontinued after several months of treatment. No increased tendency toward urinary infections was observed. Of the 28 patients who remained on therapy for over a year, only one patient consistently maintained neutrophil counts within a normal range during check-ups. Despite ongoing treatment with empagliflozin, the ANC failed to normalize (i.e., ANC > 1500) in most patients. Only one patient exhibited neutrophil normalization during routine outpatient visits (Tables 2 and 4, patient 28).

A marked reduction in infections was observed following the introduction of SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin). Prior to empagliflozin therapy, the total annual number of hospitalizations due to infections in GSD 1b patients was 32 in 2018 and 34 in 2019. Treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors commenced in early 2020, and by 2022 and 2023, the number of hospitalizations for all indications—including infections—had dropped to 13 per year. In 2024, we recorded only four hospitalizations among patients with GSD 1b. These results align with similar findings previously reported in the literature [18, 19]. In several patients, the introduction of glycosade prior to therapy with empagliflozin led to abdominal discomfort, causing reluctance to take this modified cornstarch. However, following the initiation of empagliflozin and subsequent recovery of the intestinal mucosa, these symptoms were resolved (Table 4, patients marked with asterisk).

To quantify the observed clinical improvements particularly in intestinal symptoms and anemia, we analyzed the mean hemoglobin level before and during empagliflozin therapy (Fig. 3a). A highly significant difference was detected in hemoglobin levels among GSD1b patients (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, V = 253, p-value ≈ 4.028e−05). Our data also suggest a persistent trend: patients homozygous for c.1042_1043delCT exhibited a lower level of hemoglobin in comparison to compound heterozygotes c.81T>A/c.1042_1043delCT and homozygotes for c.81T>A. This trend remained evident during enpagliflozin therapy as well (ANOVA, p-value of 0.083, Fig. 3b)

Fig. 3.

Difference in mean hemoglobin level before and during empagliflozin therapy in GSD 1b patients in Serbia. Gray dots represent measurements for each patient. A Boxplot (median, 25–75th percentile, 1.5 interquartile range (IQR)) of mean hemoglobin level before and during empagliflozin therapy in GSD 1b patients in Serbia. For comparison of mean hemoglobin level before and during empagliflozin therapy, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used, showing that the difference is statistically significant (V = 253, p ≈ 4.028e−05). Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p-value < 0.0001). B Boxplot (median, 25–75th percentile, 1.5 IQR) of mean hemoglobin level during therapy for the three most common SLC37A4 genotypes in Serbian GSD 1b patients shows statistical trend upon ANOVA with p-value of 0.083

We also analyzed mean hemoglobin (Hb) levels across three groups of Serbian GSD 1b patients with different severity of intestinal symptoms (groups 1, 2, and 3) before and during empagliflozin therapy (Fig. 4). A statistically significant difference in the mean Hb level was observed before the initiation of empagliflozin therapy, with Group 3 showing a significant difference compared to both Group 1 (ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD, p-value = 0.0024) and Group 2 (ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD p-value = 0.023) (Fig. 4a). During empagliflozin therapy the mean Hb level increased for all GSD 1b patients, regardless of the severity of previously observed gastrointestinal symptoms. No statistically differences were observed (ANOVA, p-value = 0.146) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Boxplot (median, 25–75th percentile, 1.5 interquartile range (IQR)) of mean hemoglobin (Hb) levels for three groups of Serbian GSD 1b patients with different severity of intestinal symptoms (groups 1, 2, and 3). Gray dots represent measurements for each patient. A A statistically significant difference was observed in mean Hb level before empagliflozin therapy between group 3 in comparison to both group 1 (p-value = 0.0024) and group 2 (p-value = 0.023) upon ANOVA. Asterisks indicate statistical significance and the gray dots represent measurements for each patient. B No statistically significant difference was observed in mean Hb level after empagliflozin therapy between any of the groups upon ANOVA test (p = 0.146). The gray dots represent measurements for each patient

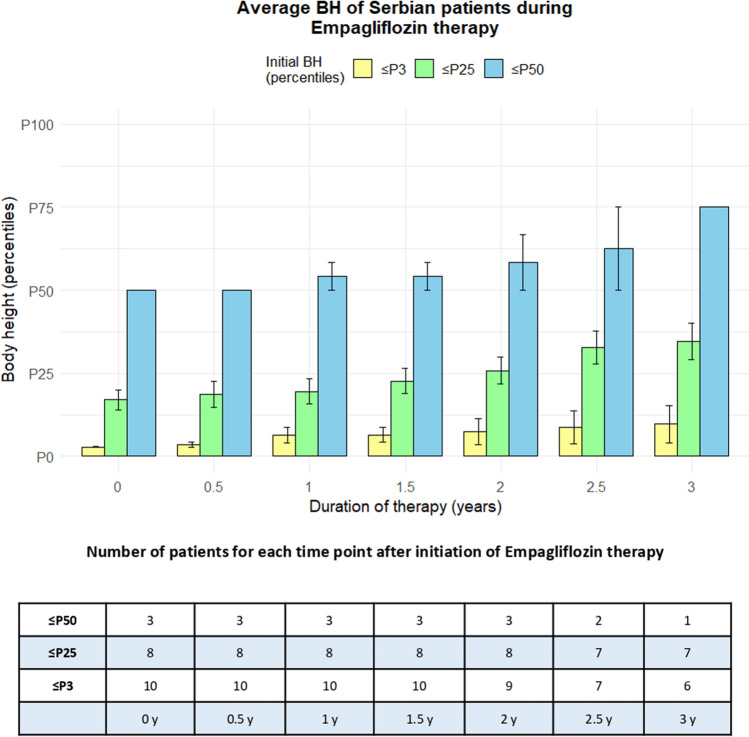

Height was expressed in percentiles (height-for-age) in 6-month intervals during empagliflozin therapy (Fig. 5, Online Supplementary Figures S1, S2, and S3). An equal number of children exhibited no change in growth rate (11) compared to those with increased growth rate (10), suggesting that empagliflozin therapy positively influenced body height of GSD 1b patients. The age at therapy initiation was not considered in this analysis.

Fig. 5.

Bar graph representing average body height of Serbian GSD 1b patients during empagliflozin therapy. Body height is expressed in percentiles (height-for-age), while duration of therapy is expressed in years, ranging from the initiation of treatment to 3 years, with 6-month intervals. The group of 21 Serbian GSD 1b patient was divided into three subgroups, depending on their body height at the beginning of empagliflozin therapy (≤ P3 represented as yellow bars, between P4 and P25 represented as green bars, and between P26 and P50 represented as blue bars). Number of patients for each subgroup at each time point was shown in the table (number decreases because some patients receive therapy for longer period of time than others)

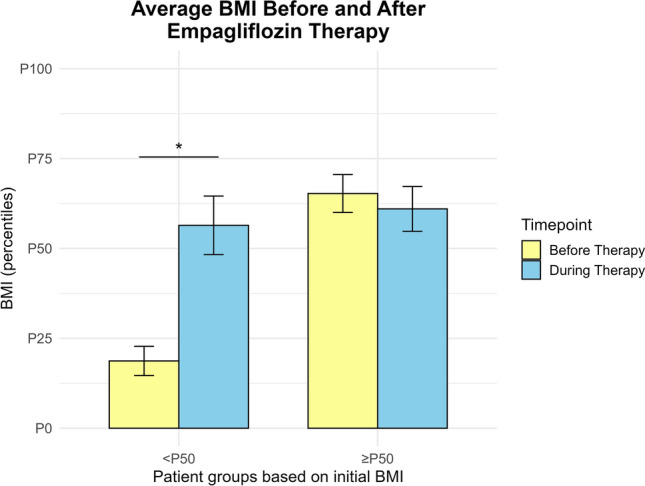

We showed that there was no statistically significant difference (paired t-test, p-value = 0.45) in BMI before and during empagliflozin therapy in children with BMI at P50 and above, while a statistically significant difference (paired t-test, p-value = 0.01) was present when BMI before therapy was below P50 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Bar graph representing the body mass index (BMI) of Serbian GSD 1b patients before and during empagliflozin therapy. Patients were stratified into two groups based on their pre-therapy BMI percentiles: below average (< 50th percentile) and average or above (≥ 50th percentile). Serbian GSD 1b patients with above average initial BMI show no statistically significant difference in BMI achieved during therapy (paired t-test, p-value = 0.45), while patients with initial below average BMI show significant increase in BMI upon empagliflozin therapy (paired t-test, p-value = 0.01). Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks

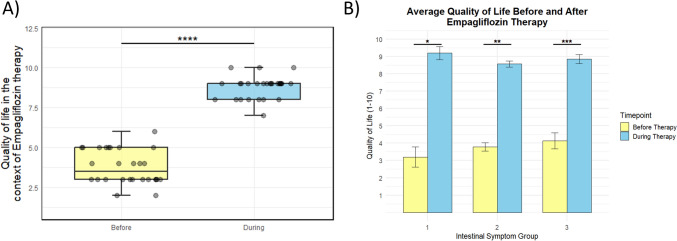

Finally, we compared self-reported quality of life and parents’ reported quality of life before and during empagliflozin therapy (Fig. 7a). In our study, a significant difference in self-reported quality of life and parents’ reported quality of life before and during empagliflozin therapy was observed (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, V = 406, p-value ≈ 3.466e−06). Moreover, we correlated self-reported quality of life and parents’ reported quality of life before and during empagliflozin therapy with severity of intestinal symptoms (groups 1, 2, and 3) (Fig. 7b). We found that the quality of life improved for all GSD 1b patients during empagliflozin therapy (paired t-test, p-value = 0.02; p-value = 0.001; p-value = 0.0016, for groups 1, 2, and 3 respectively). Quality of life did not correlate with previously observed severity of gastrointestinal symptoms (Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test, p-value = 0.37, p-value = 0.27 before and after empagliflozin therapy, respectively).

Fig. 7.

Self-reported quality of life before and during empagliflozin therapy in GSD 1b patients from Serbia. A Difference in self-reported quality of life before and during empagliflozin therapy in GSD 1b patients in Serbia. Gray dots represent measurements for each patient. Boxplot (median, 25h–75th percentile, 1.5 interquartile range (IQR)) of quality of life before and during empagliflozin therapy in GSD 1b patients in Serbia. The quality of life was obtained in a patient self-administered survey. For comparison of quality of life before and during empagliflozin therapy, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used, showing that the difference is statistically significant (V = 406, p-value ≈ 3.466e−06). Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p-value < 0.00001). B Bar graph representing the quality of life before and during empagliflozin therapy for three groups of Serbian GSD 1b patients with different severities of intestinal symptoms (groups 1, 2, and 3). The quality of life was obtained in a patient self-administered survey before the beginning of therapy (yellow bars), as well as during empagliflozin therapy (blue bars). Serbian GSD 1b patients with different severity of intestinal symptoms (groups 1, 2, and 3) show no statistically significant difference in quality of life, neither before (p-value = 0.37) nor during (p-value = 0.27) empagliflozin therapy upon a Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test. However, statistically significant improvements in quality-of-life scores during therapy, compared to before therapy, were observed in all three patient groups with varying levels of intestinal symptom severity. The p-values for groups 1, 2, and 3 were 0.02, 0.001, and 0.00016, respectively. Statistical significance is indicated by the asterisks

Data on adult patients are limited as many rarely attend check-ups and lack early medical documentation. In the case of adult patients, we obtained information from all those who were on empagliflozin therapy for more than 1 year (6 of 9). In patient number 25 (Table 4), therapy with empagliflozin stopped during pregnancy, while patient number 10 (Table 4) refused therapy with empagliflozin, and patient number 31 (Table 4) was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

The high incidence of GSD 1b in the Serbian population, as reported by Skakić et al., is most likely due to the founder effect and genetic drift [15]. Based on data from the Statistical Office of Serbia in the period from 2003 to 2023, the incidence of GSD 1b could be estimated at 1:62,870, which corresponds to the previously published incidence. The largest number of children with GSD 1b were born in 2014, indicating an annual incidence of 1:13,292.

The most prevalent variant identified in the present cohort was c.81T>A (p.Asn27Lys), which was found in 71.4% of the GSD 1b patients and in 51.4% of the tested alleles. This variant is classified as pathogenic based on the ACMG standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. It has only been reported in four patients within the European (non-Finnish) population and exhibits a very low allele frequency of 3.42e-6 in the gnomAD Exomes database [20–22]. Notably, the p.Asn27Lys variant was first described in a homozygous form in a GSD 1b patient from Bosnia and Herzegovina [23] and was not identified in subsequent studies until its high prevalence was reported in the Serbian population [15]. The high frequency of this variant in GSD 1b patients from Serbia suggests that the p.Asn27Lys change in the SLC37A4 gene likely represents a unique variant originating in this region.

This sequence change p.Asn27Lys substitutes the neutral and polar amino acid asparagine with lysine, a basic and polar residue, at codon 27 of the G6PT protein. Advanced modeling of protein sequence properties, including structural and functional features as well as amino acid conservation, predicts that this missense variant is likely to disrupt G6PT protein function. The variant is in the first luminal loop of the G6PT protein, a region predicted to play a crucial role in microsomal glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) uptake. Functional studies assessing microsomal G6P uptake activities revealed a complete lack of detectable G6P uptake activity associated with this variant, confirming its pathogenic impact on G6PT protein function [24]. In addition to its well-established role in microsomal G6P transport, emerging evidence suggests that G6PT may also be involved in the regulation of autophagy, a cellular process essential for maintaining metabolic homeostasis and immune function [25]. Impaired autophagy has been implicated in the pathophysiology of GSD 1b, contributing to neutropenia and intestinal inflammation. Interestingly, most patients harboring the c.81T>A variant do not exhibit severe intestinal manifestations or frequent infections, suggesting that this specific variant might partially preserve or even enhance autophagic activity, alleviating some clinical symptoms. Furthermore, a pair of siblings (Tables 2 and 4, patients 13 and 14) with two different missense variants (c.81T>A/c.571C>T) are free of frequent infections, they have never had oral ulcer or skin infections. This observation raises the possibility of a genotype-phenotype correlation in GSD 1b, making c.81T>A the first variant potentially linked to a milder disease course. Further studies are needed to explore this hypothesis and determine whether the c.81T>A variant exerts a protective effect through autophagy modulation.

However, in contrast to this milder phenotype, a boy harboring the c.81T>A/c.785G>A genotype presented with a severe intestinal form of the disease and frequent infections (Tables 2 and 4, patient number 21). The c.785G>A variant appears to have a dual effect on protein function, which may contribute to the severity of his clinical presentation. In addition to being a missense variant, functional analysis in our previous study [16] confirmed that it leads to altered splicing, resulting in the formation of a truncated transcript that lacks the ER membrane anchoring domain. If the splicing machinery succeeds in generating a full-length mRNA, the resulting G6PT protein would still be functionally compromised due to the p.Gly262Asp substitution, which has been predicted to be damaging [26]. Therefore, the c.785G>A variant exhibits a dual pathogenic mechanism, producing either p.Ser263Glyfs*33 (a frameshift leading to premature truncation) or p.Gly262Asp (a damaging amino acid substitution), securing its strong pathogenic effect.

The pathogenic variant c.1042_1043del (p.Leu348Valfs*53) in the SLC37A4 gene was the second most frequent variant in our cohort, detected in 32.9% of the tested alleles. It is also the second most common variant in England [27]. It has been frequently reported in mixed Caucasian (27–31%), German (32%), and Korean (33.3%) populations [1, 23, 28] and is classified as pathogenic according to ACMG standards. This variant is observed in the gnomAD Exomes and gnomAD Genomes databases with an overall allele frequency of 1.75e−4 and 2.56e−4, respectively [29].

The small deletion of CT nucleotides between positions 1042 and 1043 in the coding region of the SLC37A4 gene results in the substitution of leucine with valine at position 348, followed by a premature stop codon 53 amino acids downstream of the original sequence. The consequence of this frameshift is the truncation of the G6PT protein, leading to a loss of its normal functional domains, as it severely disrupts the transporter’s ability to function properly, impairing G6P uptake in the ER [30]. As a result, G6P accumulation occurs, contributing to the hallmark features of the disease, including neutropenia, neutrophil dysfunction, and hepatic glycogen storage. Experimental studies confirm that this frameshift variant results in a nonfunctional protein, underscoring its pathogenic role in GSD 1b. Additionally, the intactness of helix 10 in G6PT including the ER transmembrane protein retention motif KKAE (amino acids 426–429), play an essential role in maintaining the structural integrity and proper localization of the transporter [3, 31]. The loss of these structural elements due to the frameshift variant, such as p.Leu348Valfs*53, likely contributes to the inability of the transporter to function normally, causing the clinical manifestations of the disease.

In our study, patients carrying c.1042_1043delCT generally exhibited more severe intestinal complications. Among homozygous patients, five out of six (83%) presented with severe IBD-like symptoms, including a girl who passed away and a young man with extensive gastrointestinal narrowing and intestinal perforations, who was ultimately lost to follow-up. However, within this group of homozygotes with deletion, one girl was diagnosed with glycogen storage disease type 1b at 6 months of age, following investigations for neutropenia and recurrent otitis media. By the age of two, when she started therapy with empagliflozin, she had not experienced gastrointestinal symptoms (Tables 2 and 4, patient 26). This example suggests that an absolute genotypic-phenotypic correlation cannot be conclusively established based on our findings [32]. Further research is required on the factors that influence the phenotype of patients with GSD 1b as well.

However, in the past decade, six patients received a significantly delayed diagnosis. A study conducted in Poland on 13 patients with GSD 1b showed that the median age at diagnosis was 6 months [33]. In a cohort of 35 patients in England, the median age at diagnosis was 4 months, but with several patients not diagnosed until their third year of life and two patients diagnosed incidentally in adulthood [23]. If we exclude six patients with a very late diagnosis, the average age when the diagnosis was made in our center is 10 months, which remains later than ideal. Notably, all six patients with a delayed diagnosis were either homozygous for the c.81T>A variant or compound heterozygous for c.81T>A and c.571C>T, suggesting a potential correlation between these genetic variants and a milder disease presentation (Table 2, four patients, numbers 3, 6, 7, 8, 13, 14). The absence of severe early metabolic symptoms, particularly significant hypoglycemia or marked hepatomegaly, may have contributed to the later clinical recognition of GSD 1b in these individuals. This pattern raises the possibility that c.81T>A, alone or in combination with c.571C>T, may modulate disease severity, delaying the onset of hallmark symptoms that typically prompt an earlier diagnosis. The data showing that recurrent infections are the first manifestations of GSD1b (in our cohort 60%) correlates with publications by Polish authors [33].

Patients experiencing more severe disease progression, including frequent infections, and serious intestinal complications exhibited recurrent infections from infancy. Additionally, in 40% of all cases, primary immunodeficiency was initially suspected due to neutropenia prior to the confirmation of GSD 1b. We also support French study group findings, suggesting that individuals with severe IBD-like symptoms tend to present earlier with intestinal symptoms and exhibit a more severe overall phenotype [6].

Based on our patient records, we did not find a direct correlation between severe infection history and neutropenia severity, lowest neutrophil counts and infection severity, or severe intestinal disease and earliest recorded neutropenia. We speculate that neutropenia is present in all patients from birth, but may not always be consistently documented [11]. Possible reasons include routine blood testing is not routinely done in the first months of life, the increase in neutrophils number during infections, and also fluctuations in neutrophil count numbers. Among all living GSD 1b children (a total of 25 out of 26) every individual had ANC levels below 500, at least once. Given the lack of correlation between neutrophil count and the severity or frequency of infections, we suggest that ANC measurements are not useful predictors of GSD 1b phenotype.

Autoimmune thyroiditis was not observed in a higher percentage of our patients, as reported in other centers [34, 35]. To date only one adult women with GSD 1b was investigated for suspected thyroid dysfunction, but it was not proven (Table 2, patient number 34). However, four patients with GSD 1b (Table 2, patient numbers 5, 17, 23, and 35) in our study developed arthritis in large joints, which was initially treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but symptom resolution occurred after corticosteroid therapy was introduced. In a Chinese study, among 44 patients with IBD, six (14%) developed IBD-associated arthritis [36]. In our cohort, four of 35 patients (11.4%) exhibited arthritis. Considering that our two patients exhibited symptoms of arthritis early (around 5 years of age), before clear signs of inflammatory bowel disease appeared, but while they experienced gastrointestinal symptoms, we speculate that arthritis is associated with IBD, and may be an autoimmune condition like autoimmune thyroiditis. It should be noted that intestinal problems do not have to be present early, for example, in a study from North America found that the average age at the diagnosis of IBD-like symptoms was 8.7 years [37]. Many authors highlight that distinguishing chronic or cyclic gastrointestinal symptoms from IBD is challenging. Most studies suggest that over 70% of GSD 1b patients develop IBD like [6, 36, 37]. However, many reports take all gastrointestinal symptoms into account, including oral ulcers which are recognized as a highly sensitive marker for IBD [37]. All our patients had oral ulcers at least once. Based on our observations, we believe that before the introduction of empagliflozin in the treatment of GSD 1b, each patient exhibited at least some IBD-like symptoms.

According to our study (Fig. 2), anemia serves as a reliable indicator of gastrointestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases [38, 39]. Similarly, a Chinese study of 35 patients observed a significant increase in hemoglobin during empagliflozin therapy [40]. Although recommendations for the introduction and dosing of empagliflozin were published after the drug was introduced to most patients, clinical practice aligned well with these recommendations [41].

Several studies based on endoscopic findings support the success of empagliflozin treatment. Endoscopic examinations conducted during empagliflozin therapy have shown significant improvement and remission in patients receiving this therapy [8, 42, 43]. Through clinical monitoring, including growth parameters, reduced hospitalizations, hemoglobin levels, and quality-of-life assessments, we concur that empagliflozin therapy has significantly improved intestinal function in our patients [44]. However, determining whether patients with IBD-like symptoms, particularly those with severe disease, benefit more from continuing conventional IBD therapy (such as mesalazine) alongside SGLT2 inhibitors remains challenging. Among the four patients previously receiving conventional IBD therapy, treatment was discontinued in two and continued in two. Based on our observations, we cannot conclude that patients who remained on conventional therapy had better clinical outcomes.

All patients treated with empagliflozin experienced an improved quality of life. We observed that the most significant improvements in quality of life occurred among children with the most severe forms of the disease (Tables 2 and 4, patients 21, 28, 33). However, due to the small sample size, we were unable to confirm this trend statistically. Tolerance to glycosade (modified cornstarch) significantly improved with empagliflozin therapy, especially in younger children, but also in older patients. It is likely that co-administration of empagliflozin and glycosade contributed to the overall improvement in patient quality of life [38].

Limitations

All conclusions drawn on the severity of SLC37A4 genetic variants, the genotype-phenotype correlation, and clinical and biochemical observations, are limited by the number of patients included in our study, and should be confirmed in larger cohorts of patients with the same genotype. Additionally, in the case of the c.81T>A variant in the SLC37A4 gene, further functional in vitro studies are needed to assess its specific effect on the autophagy process.

For an ultra-rare disease, our cohort includes an impressive number of patients, yet for more precise and comprehensive research, collaboration in trials with larger patient groups is necessary. The lack of clinical and laboratory data in adult patients limits us in drawing conclusions for this population. Furthermore, other factors influencing anemia were not considered in this study. Since endoscopic and pathohistological findings were not available for all patients, a more thorough evaluation including clinical indicators, such as anemia, would provide deeper insight into the severity of gastrointestinal symptoms. One of the main facets of empagliflozin therapy is its relatively short duration of use, spanning only a few years. Regarding compliance, patient adherence to therapy is largely debatable, though this is more related to dietary adherence than to empagliflozin therapy itself. A minimum treatment duration of 1 year was set for analysis, though treatment duration varied across patients over different timeframes. Finally, this study did not account for metabolic control assessment, which could further contribute to understanding disease management.

Conclusions

The Serbian population exhibits the highest incidence of GSD 1b ever recorded worldwide. Our most common missense mutation is generally associated with a milder phenotype. It can be concluded that the majority of patients with small deletions, particularly homozygotes, have the most severe intestinal manifestations and belong to those with the most severe clinical picture. However, it is important to note that serious gastrointestinal tract manifestations can occur in patients with any genotype. While recurring phenotypic patterns were observed in specific genotypic groups, establishing a direct association between genotype and clinical presentation remains challenging.

Our study suggests that neutrophil count is not a reliable predictor of GSD 1b phenotype or the severity of intestinal symptoms. However, we propose that hemoglobin level should be further explored as a marker that mirrors genotype-phenotype correlation and a marker of improvements during empagliflozin therapy. Based on medical documentation analysis, we conclude that patients experiencing later onset of first infection generally are not the most severe cases and tend to exhibit less serious intestinal manifestations. Furthermore, we believe that neutropenia is present from birth in all patients, but ANC varies due to multiple factors. As reported in other centers, an excellent therapeutic response to empagliflozin was observed. Clinically, patients exhibited significant reduction in the number of infections, improved bowel function symptoms, increased hemoglobin levels, improved body weight and stature, and notable enhancement in overall quality of life. Additionally, we found that after initiating empagliflozin therapy, most patients experienced relief from abdominal discomfort when taking glycosade.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, Prisma program, Grant Number 6999 and Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia [Number: 451-03-136/2025-03/200042].

Conflict of Interest

The authors MDjM, AS, BK, SS, IK, SP, MS declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Approval Committee of the Mother and Child Health Care Institute of Serbia “Dr Vukan Cupic” in Belgrade, Serbia (8/2025 and 31/2020).

Human Ethics and Consent to Participate

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

Raw genetic data are generated and stored at Institute of Molecular Genetics and Genetic Engineering, University of Belgrade, and are available on reasonable request.

Authors’ Contributions

MDj conceived the study, collected all data, performed analysis, wrote the paper; AS performed the genetic analysis and wrote the paper; SS prepared all figures; BK and IK collected the patients’ phenotype data; SP reviewed the paper; MS wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Kishnani PS, Austin SL, Abdenur JE, et al. Diagnosis and management of glycogen storage disease type I: a practice guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2014;16(11): e1. 10.1038/gim.2014.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rake JP, Visser G, Labrune P, et al. Glycogen storage disease type I: diagnosis, management, clinical course and outcome. Results of the European Study on Glycogen Storage Disease Type I (ESGSD I). Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(Suppl 1):20–34. 10.1007/s00431-002-0999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou JY, Jun HS, Mansfield BC. Type I glycogen storage diseases: disorders of the glucose-6-phosphatase/glucose-6-phosphate transporter complexes. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38(3):511–9. 10.1007/s10545-014-9772-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Froissart R, Piraud M, Boudjemline AM, et al. Glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:27. 10.1186/1750-1172-6-27-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chena MA, Weinstein DA. Glycogen storage diseases: diagnosis, treatment and outcome. Transl Sci Rare Dis. 2016;1:45–72. 10.3233/TRD-160006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wickera C, Rodab C, Perryc A, et al. Infectious and digestive complications in glycogen storage disease type Ib: Study of a French cohort. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2020;23: 100581. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2020.100581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visser G, Rake JP, Fernandes J, et al. Neutropenia, neutrophil dysfunction, and inflammatory bowel disease in glycogen storage disease type Ib: results of the European Study on Glycogen Storage Disease type I. J Pediatr. 2000;137:187–91. 10.1067/mpd.2000.105232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veiga-da-Cunha M, Chevalier N, Stephenne X, et al. Failure to eliminate a phosphorylated glucose analog leads to neutropenia in patients with G6PT and G6PC3 deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(4):1241–50. 10.1073/pnas.1816143116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grünert SC, Elling R, Maag B, et al. Improved inflammatory bowel disease, wound healing and normal oxidative burst under treatment with empagliflozin in glycogen storage disease type Ib. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:218. 10.1186/s13023-020-01503-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dale DC, Bolyard AA, Marrero T, et al. Neutropenia in glycogen storage disease Ib: outcomes for patients treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Curr Opin Hematol. 2019;26:16–21. 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visser G, Rake JP, Labrune P, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in glycogen storage disease type 1b: results of the European Study on Glycogen Storage Disease Type 1. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(Suppl 1):S83–7. 10.1007/s00431-002-1010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wortmann SB, Van Hove JLK, Derks TGJ, et al. Treating neutropenia and neutrophil dysfunction in glycogen storage disease type Ib with an SGLT2 inhibitor. Blood. 2020;136:1033–43. 10.1182/blood.2019004465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veiga-da-Cunha M, Wortmann SB, Grünert SC, Van Schaftingen E. Treatment of the Neutropenia Associated with GSD1b and G6PC3 Deficiency with SGLT2 Inhibitors. Diagnostics. 2023;13:1803. 10.3390/diagnostics13101803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaczor M, Malicki S, Folkert J, Dobosz E, et al. Neutrophil functions in patients with neutropenia due to glycogen storage disease type 1b treated with empagliflozin. Blood Adv. 2024;8(11):2790–802. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023012403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skakic A, Djordjevic M, Sarajlija A, et al. Genetic characterization of GSD I in Serbian population revealed unexpectedly high incidence of GSD Ib and 3 novel SLC37A4 variants. Clin Genet. 2018;93:350–5. 10.1111/cge.13093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connelly JA, Walkovich K. Diagnosis and therapeutic decision-making for the neutropenic patient. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2021;2021(1):492–5. 10.1182/hematology.2021000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grünert SC, Derks TGJ, Adrian K, et al. Efficacy and safety of empagliflozin in glycogen storage disease type Ib: data from an international questionnaire. Genet Med. 2022;24(8):1781–8. 10.1016/j.gim.2022.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derks TGJ, Venema A, Köller C, et al. Repurposing empagliflozin in individuals with glycogen storage disease Ib: a value-based healthcare approach and systematic benefit-risk assessment. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2024;47(2):244–54. 10.1002/jimd.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trioche P, Petit F, Francoual J, et al. Allelic heterogeneity of glycogen storage disease type Ib in French patients: a study of 11 cases. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2004;27(5):621–3. 10.1023/b:boli.0000042987.43395.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beyzaei Z, Geramizadeh B. Molecular diagnosis of glycogen storage disease type I: a review. EXCLI J. 2019;18:30–46. 10.1002/1098-1004(200008)16:2%3c177::AID-HUMU13%3e3.0.CO;2-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paesold-Burda P, Baumgartner MR, Santer R, et al. Elevated serum biotinidase activity in hepatic glycogen storage disorders–a convenient biomarker. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30(6):896–902. 10.1007/s10545-007-0734-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santer R, Rischewski J, Block G, et al. Molecular analysis in glycogen storage disease 1 non-a: DHPLC detection of the highly prevalent exon 8 mutations of the G6PT1 gene in German patients. Hum Mutat. 2000;16(2):177. 10.1002/1098-1004(200008)16:2%3c177::AID-HUMU13%3e3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen LY, Pan CJ, Shieh JJ, Chou JY. Structure–function analysis of the glucose-6-phosphate transporter deficient in glycogen storage disease type Ib. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(25):3199–207. 10.1093/hmg/11.25.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andjelkovic M, Skakic A, Urin M, et al. Crosstalk between glycogen-selective autophagy, autophagy and apoptosis as a road towards modifier gene discovery and new therapeutic strategies for glycogen storage diseases. Life. 2022;12(9):1396. 10.3390/life12091396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C, Zhi D, Wang K, et al. MetaRNN: differentiating rare pathogenic and rare benign missense SNVs and InDels using deep learning. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):115. 10.1186/s13073-022-01120-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halligan R, White FJ, Schwahn B, et al. The natural history of glycogen storage disease type Ib in England: a multisite survey. JIMD Reports. 2021;59:52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi R, Park HD, Ko JM, et al. Novel SLC37A4 mutations in Korean patients with glycogen storage disease 1b. Ann Lab Med. 2017;37:261–6. 10.3343/alm.2017.37.3.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–43. 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. (Erratum in: Nature. 2021;597(7874):E3-E4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y, Kishnani PS, Koeberl D, et al. Glycogen storage diseases. In: Valle DL, Antonarakis S, Ballabio A, et al., editors. The online metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. 10.1036/ommbid.380. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cappello AR, Curcio R, Lappano R, Maggiolini M, Dolce V. The physiopathological role of the exchangers belonging to the SLC37 family. Front Chem. 2018;17(6):122. 10.3389/fchem.2018.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melis D, Fulceri R, Parenti G, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlation in glycogen storage disease type 1b: a multicentre study and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164(8):501–8. 10.1007/s00431-005-1657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaczor M, Wesół-Kucharska D, Greczan M, et al. Clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes of patients with glycogen storage disease type 1b: a retrospective multi-center experience in Poland. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2022;28(3):207–12. 10.5114/pedm.2022.116115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melis D, Pivonello R, Parenti G, et al. Increased prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity and hypothyroidism in patients with glycogen storage disease type I. J Pediatr. 2007;150:300–5. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melis D, Carbone F, Minopoli G, et al. Cutting edge: increased autoimmunity risk in glycogen storage disease type 1b is associated with a reduced engagement of glycolysis in T cells and an impaired regulatory T cell function. J Immunol. 2017;198(10):3803–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia Y, Sun Y, Du T, Sun C, et al. Genetic variants and clinical features of patients with glycogen storage disease type Ib. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(2): e2461888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dieckgraefe BK, Korzenik JR, Husain A, Dieruf L. Association of glycogen storage disease 1b and Crohn disease: results of a North American survey. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161(Suppl 1):S88-92. 10.1007/s00431-002-1011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao BB, Koutroubakis IE, Ramos Rivers C, et al. Correlation of anemia status with worsening bowel damage as measured by Lémann Index in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:626–31. 10.1016/j.dld.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson A, Reyes E, Ofman J. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116(Suppl 7A):S44–9. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shao YX, Liang CL, Su YY, et al. Clinical spectrum, over 12-year follow-up and experience of SGLT2 inhibitors treatment on patients with glycogen storage disease type Ib: a single-center retrospective study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024;19(1):155. 10.1186/s13023-024-03137-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grünert SC, Derks TGJ, Mundy H, et al. Treatment recommendations for glycogen storage disease type IB associated neutropenia and neutrophil dysfunction with empagliflozin: consensus from an international workshop. Mol Genet Metab. 2024;141: 108144. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2024.108144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calia M, Arosio AML, Crescitelli V, et al. Crohn-like disease long remission in a pediatric patient with glycogen storage disease type Ib treated with empagliflozin: a case report. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:1–7. 10.1177/17562848231202138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klinc A, Groselj U, Mlinaric M, et al. Case report: the success of empagliflozin therapy for glycogen storage disease type 1b. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;11(15):1365700. 10.3389/fendo.2024.1365700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grünert SC, Venema A, LaFreniere J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes on empagliflozin treatment in glycogen storage disease type Ib: an international questionnaire study. JIMD Reports. 2023;64:252–8. 10.1002/jmd2.12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw genetic data are generated and stored at Institute of Molecular Genetics and Genetic Engineering, University of Belgrade, and are available on reasonable request.