Abstract

This study examines the adoption of sustainable supply chain practices (SSCPs) among three hotel categories: international chain hotels, 5-star local chains, and 4-star local chains located in Egypt. It aims to identify the drivers, barriers, and variations in the implementation of these practices. A qualitative multi-case study methodology was employed, involving in-depth interviews with managers at nine hotels. The study also presents a theoretical framework developed from stakeholder theory that illustrates how stakeholder pressures and organizational capacities drive or hinder the adoption of SSCPs and how these practices contribute to broader sustainability objectives. Significant variations were observed in SSCPs. International chains implement advanced practices such as comprehensive waste management and energy-efficiency programs. 5-star local chains focus on cost-saving initiatives and basic recycling, while 4-star local chains primarily adopt simple waste reduction and local sourcing. Differences in barriers also exist: 4-star local chains face more financial and knowledge limitations, while international chains face additional challenges related to supplier engagement and infrastructure. Hotel owners and managers can enhance sustainability by providing staff training, fostering collaboration with suppliers, and strategically allocating resources. Such activities are crucial for local chains with limited resources. This research fills gaps in the literature by exploring SSCPs in a developing-country context and integrating stakeholder theory to uncover both normative and instrumental drivers of SSCPs. It presents a conceptual framework that links SSCPs with drivers, barriers, and outcomes, providing a practical guide for hotels to enhance their sustainability.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-18819-9.

Keywords: Sustainable supply chain practices, Sustainable hospitality supply chain management, Hotels, Stakeholder theory

Subject terms: Sustainability, Environmental impact

Introduction

Sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) has become a central focus in organizational strategy, as companies increasingly recognize the need to integrate ecological and social considerations into their operations1,2. While some scholars suggest that sustainability may even surpass profitability in importance3, embedding sustainable innovations within supply networks remains a relatively new and evolving practice that challenges organizations to rethink their established systems1.

Academic research has made significant progress in identifying the core components of sustainable supply chains, as well as the triple-bottom-line model, which encompasses environmental, social, and economic outcomes4,5. Nonetheless, most empirical research has focused on the manufacturing sector, while service-related sectors, such as hospitality, have received little attention6–8. Although the impact of SSCM on sustainability performance has been associated with positive findings in studies on hotels and healthcare settings, most studies in these contexts are scarce in terms of well-grounded theory and depth9–12. The hospitality and tourism industries are under increasing scrutiny from stakeholders due to their environmental footprints and social responsibilities13,14. Addressing sustainability challenges in these sectors is vital not only for environmental stewardship but also for social equity and long-term profitability. Creative solutions, such as ecotourism, underscore the interconnectedness of hospitality and tourism, as well as the potential for shared sustainability benefits15.

Hotels are one of the most resource-intensive institutions in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, with water and energy consumption at perilously high levels, CO₂ emissions into the atmosphere, and sustainability initiatives that both harm the environment and undermine the eco-summit. However, some hotels focus on cutting costs, while others in the West emphasize that it is shareholders’ responsibility to promote eco-friendly practices16. In the context of (I) the economic importance of the Egyptian hotel industry and (II) the environmental sensitivity of hotel accommodations, it is inevitable that Egypt’s hotel sector is built on its unique heritage and natural resources. The government has responded to the current challenge with policy measures aimed at promoting sustainable tourism and enhancing Egypt’s competitiveness as a sustainable destination17. However, the adoption of SSCM in Egyptian hotels has been explored narrowly, particularly in the context of the varying responses by different hotel categories to sustainability pressures.

Recent studies have reviewed several recent publications that address shortcomings in the existing literature on the sustainability of hotel supply chains. However, most research to date has narrowly explored the adoption and motivation of environmental practices without examining their actual effects or the broader performance and stakeholder implications of hotel operations18,19. The social dimension of sustainability is often overlooked; however, it is essential to obtain a comprehensive understanding of sustainable supply chain management20. However, a large proportion of the literature also provides a specific focus on hotel types (independent, 5-star). It restricts their investigation to specific stakeholder groups (guests and employees), without addressing the roles of other supply chain members (such as suppliers and tour operators)21–23. This restricted view of complexity and linkages related to sustainability issues in the hotel industry is inappropriate. These limitations underscore the need for an overarching research model that encompasses environmental, social, and economic factors and considers all stakeholder groups involved in the hotel supply chain.

To guide our investigation, we draw on stakeholder theory, which provides a robust ethical and practical foundation for understanding how various groups influence and are influenced by sustainability practices24,25. While traditional SSCM research has often prioritized economic outcomes, stakeholder theory emphasizes the importance of balancing economic, social, and environmental goals26,27. This perspective is particularly relevant in the hospitality industry, where stakeholder expectations and pressures can vary significantly across hotel categories and operational contexts.

Additionally, there is little empirical evidence to support explanatory frameworks that associate SSCM practices with actual impacts on hotels and their stakeholders28,29. In doing so, the present study extends and fills the existing gap, employing a comprehensive stakeholder-based framework to explore the drivers, barriers, and impacts of SSCM in local and international hotel chains operating in Egypt. This method offers novel comparative perspectives and applies relevant guidance to the industry. To inform our inquiry, we employed stakeholder theory, as it provides a solid ethical and practical foundation for examining how different stakeholders shape, and are shaped by, sustainability practices24,25.

In contrast to earlier research, which typically isolates environmental initiatives or single stakeholder views, this study adopts a systemic perspective of the relationship between hotels and their suppliers by (1) taking a systematic perspective across three different hotel categories: international chains, 5-star local chains, and 4-star local chains, and (2) explicitly addressing the roles and perspectives of all of the most important supply chain stakeholders, including suppliers and tour operators. This model offers comprehensive insights into the drivers, barriers, and impacts of SSCM in Egypt’s hotel sector, where the economic significance of tourism and its environmental sensitivity are well recognized. With the multivariate qualitative design implemented, the research helps to fill the existing void in the literature regarding detailed, theory-informed analysis of the sustainability dimension in hospitality supply chains in less developed economies. This investigation is conceptually situated within the framework of stakeholder theory, which provides a robust ethical and practical foundation for understanding how sustainability practices impact various stakeholder groups24,25. Although the traditional SSCM literature tends to focus on economic performance, stakeholder theory emphasizes the importance of addressing not only economic factors but also social and environmental concerns as part of a strategic approach to achieving long-term business success26,27. In the hospitality industry, this equilibrium is particularly relevant, as stakeholder expectations and pressures can vary significantly between hotel types and operational contexts. Therefore, the following research questions (RQs) guided this study.

RQ1. What types of sustainable supply chain practices (SSCPs) are implemented by Egyptian hotel firms?

RQ2. Why do Egyptian hotels implement SSCPs?

RQ3. What key barriers have hindered hotels’ adoption of SSCPs in Egypt?

RQ4. Are there any differences or similarities among local 4-star chain hotels, local 5-star chain hotels, and international chain hotels in terms of SSCPs?

We reviewed the SHSCM literature and collected data on nine hotels operating in Egypt, employing a multi-case study research approach. Drawing on data collected using semi-structured interviews of local and international hotel chains, this study contributes to the literature by: (1) exploring the SSCPs drivers and barriers in a developing country from the hotel’s perspective, which is an under-explored area to date; (2) presenting SSCPs that span through the three dimensions of sustainability, and their impact on the environmental, social, economic, operational, and reputational performance of hotels; (3) performing a multi-level analysis of identified factors implementing SSCPs in supply chains (such as internal and external environmental practices; and organizational, supply chain, and community-level social or economic practices); (4) identifying the commonalities and differences between international chain hotels (ICHs), 5-star local chain hotels (LCHs5), and 4-star local chain hotels (LCHs4); and (5) developing a conceptual framework based on our empirical findings and stakeholder theory. The proposed framework can serve as a guiding paradigm for hotels, offering valuable insights on implementing sustainable practices.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Literature review” presents the background of this study. Section “Methodology” describes the research methodology. Section “Findings” presents the key findings, followed by section “ Discussion and conceptual framework”, which includes a discussion and conceptual framework. Section “Conclusion” concludes the study, outlining its limitations and providing directions for future research.

Literature review

Sustainable supply chain management

Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM) is defined as [.] the management of material, information, and capital flows as well as cooperation among companies along the supply chain while taking goals from all three dimensions of sustainable development, i.e., economic, environment and social, into account which are derived from customer and stakeholder requirements[30, p. 1700].

Research in the field of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) consistently demonstrates a strong causal relationship between the adoption of SSCM practices and the enhancement of SSCM performance. Numerous studies, such as Hussain et al.11, Kähkönen et al.31, and Wang et al.32 have provided compelling evidence that organizations embracing supply chain sustainability experience improved environmental, social, and economic outcomes. Firms can reduce their environmental footprint, enhance operational efficiency, lower costs, and strengthen their reputation by implementing green procurement, supplier collaboration for sustainability, human rights practices, and philanthropy initiatives.

Research gaps

Based on a review of the most relevant studies related to this study (Table 1), several common gaps between studies have been identified. The current research landscape on sustainable practices within the hotel supply chain reveals several interconnected gaps and limitations. Robin et al.19 focus on the adoption of environmental practices in independent hotels, probing into their drivers and barriers. However, their analysis stops short of examining the actual outcomes of these practices, thereby providing an incomplete assessment of their tangible impact. This gap in outcome analysis is somewhat echoed in the study by Abdou et al.18, which concentrates solely on eco-friendly 5-star hotels and their environmental sustainability, again neglecting broader implications. Cerchione and Bansal20 examined the impact of environmental practices on the environmental and economic performance of hotels. While valuable, their research overlooks the social aspect of sustainability, which is a critical component for a comprehensive understanding of sustainability in the hospitality sector. This oversight was similarly observed by Ibrahim et al.23, who, despite focusing on the social dimension, limited their study to a specific group (Greater Cairo hotel workers) and a single hotel category, thus missing a broader perspective.

Table 1.

Recent contributions in the field of sustainable practices in the hotel supply chain.

| Citation | Region of research | Aim | Methods | Main results | Limitations | Future research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robin et al.19 | Spain & Chile |

Examine the adoption of environmental practices in the hotel industry and its impact on independent hotels in mature and emerging destinations. The study focuses on two destinations, Madrid in Spain and Santiago and Valparaiso in Chile, and aims to compare the implementation of environmental practices in these two contexts |

A qualitative method based on case studies of 24 hotels, data collected through Semi-structured interviews | The adoption of environmental practices in both surveyed destinations elucidates the multifaceted consequences of this implementation, primarily in the financial and operational spheres. Differences are observed in the two countries regarding the proposed model, mainly in terms of barriers to implementing environmental practices, products used, and processes related to clients’ and suppliers’ responsibilities | The interviewees were not hotel guests but senior managers, so it was not possible to obtain a broader picture of guests’ perceptions of sustainable practices |

- Future research could focus on direct customer perceptions and evaluations related to the sustainable practices offered by independent hotels. - Future research can conduct a quantitative study with a representative sample of independent hotels through sampling techniques |

| Alameeri et al.28 | UAE | Developing a framework to identify, categorize, and prioritize sustainable management practices in the UAE hotel sector | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative): an extensive literature review and expert opinions collected through in-depth interviews using: Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), involving numerical scoring and ranking based on a structured survey | Employee management and government management take top priority under the main criteria, and policy requirements, customer culture, and education and training were determined to be the three most relevant sub-criteria for sustainable practices for hotels in the UAE. Furthermore, the hotels mostly focus on economic sustainability; however, the environmental and social dimensions of sustainability are ignored in management practices | The data was collected from only four and five-star hotels in the UAE | Future research can use the sustainability model of this research to measure sustainability in different hotel categories, further, the model can be used in different sectors |

| Ghaderi et al.34 | Iran | Investigating and illuminating critical aspects of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and the performance of four and five-star hotels, focusing on the Iranian capital, Tehran | Quantitative approach: questionnaire survey of 350 employees of hotels; data analyzed using structured equation modeling | CSR initiatives positively on hotels’ performance within the context of four and five-star hotels in Tehran. These effects apply to all the five dimensions of CSR (social, economic, legal, ethical, and environmental) | The data was collected from small number of hotels in Tehran, the majority under a mix of public and private ownership and operation | Future research could focus on different types of hotels in other areas and explore the processes by which CSR impacts financial performance and relevant mediators |

| Cerchione and Bansal20 | India | Exploring the impact of environmental policy and training aspects on hotels’ sustainability practices, along with evaluating the consequential effects of these practices on both environmental and financial performance | Quantitative approach: questionnaire survey of 312 managers from the Indian hospitality industry; data analysis using structural equation modeling | The environmental policy and training positively impact environmental communication, resource preservation, and energy preservation in the Indian hotel sector | The research focused only on the environmental dimension, with the absence of other social and economic dimensions | Future research could focus on the managerial alignment of social perspective with environmental and financial perspectives |

| Asadi et al.21 | Malaysia | Exploring the impact of green innovation on the association of environmental, social, and economic aspects of sustainable performance, and Evaluating the outcomes based on the experiences of a selected sample of Malaysian hotels | Quantitative approach: questionnaire survey from 183 hotels in Malaysia; data was analyzed using structural equation modeling | The study shows that green innovation is positively associated with the environmental and social performance of the business, and economic performance is another important influencing factor | The research focused only on the effect of green practices on the sustainable performance of hotels | Investigate other factors related to CSR or the Economic dimension of sustainability that influence the sustainable performance of the same industry |

| Khatter et al.33 | Australia | Exploring the barriers to and drivers of environmentally sustainable practices in the Australian hotel from the perspective of hotel managers | Qualitative research approach involving semi-structured in-depth interviews with 8 hotel managers | The major barriers to adapting environmental practices are time, financial challenges, availability of resources, and the views and imperatives of hotel owners and shareholders. The major drivers are financial, marketing, owner, and shareholder interests, and guest preferences | The research data were collected from the hotel managers, so it represents only the perspective of hotel managers | Obtain the views of other hotel stakeholders (i.e., suppliers, guests, employees) to gain a deeper understanding of the barriers to and drivers of environmental practices |

| Peña-Miranda et al.29 | Colombia | Exploring the sustainable practices in the Colombian hotel industry | Qualitative method based on case studies of 8 hotels, data collected through Semi-structured interviews | The sustainable practices of Colombian hotels are categorized into three classes: philanthropic-reactive, legal-reactive, and active groups |

- The research only considered eight hotels in Santa Marta, Colombia - The study primarily relied on data collected from hotel managers, which did not include a comprehensive analysis of all stakeholders involved in sustainable practices - The study did not provide a quantitative analysis of the outcomes or impacts of the sustainable practices observed in the hotels |

- Examine the opinions of other hotel stakeholders, such as employees, guests, and the local community, to establish a more comprehensive understanding of sustainable practices in the hospitality industry - Explore the impact and outcomes of sustainable activities by designing and implementing indicators that have a direct relationship with stakeholders. This would help in measuring the results of sustainable initiatives effectively |

| Abdou et al.18 | Egypt | Investigating the impact of environmentally sustainable practices (ESPs) on green satisfaction (GS) and customer citizenship behavior (CCB) in five-star hotels in Egypt and explore the potential mediative role of GS in the nexus between CCB and ESPs | Quantitative approach: questionnaire survey from 437 customers of hotels in Egypt; data was analyzed using structural equation modeling | ESPs significantly positively affect both GS and CCB. GS significantly impacts CCB, and GS partially mediates the relationship between CCB and ESPs | Focus on a specific customer demographic (Egyptian customers in five-star eco-friendly hotels) | Expand the scope of research to include other customer demographics and investigate the role of ESPs in different types of hotels |

| Ibrahim et al.23 | Egypt | Exploring the direct and indirect effects of perceived CSR on employees’ engagement through organizational identification in the hotel industry | Quantitative approach: questionnaire survey from 420 employee in Egypt; data was analyzed using structural equation modeling | CSR practices and identification are crucial drivers of employees’ engagement; CSR toward stakeholders significantly influences both organizational identification and employees’ engagement, except for customers |

Limited target population (Greater Cairo hotel workers), and focus on five-star hotels |

Include expanding the target population, exploring other industries, and using diverse research methodologies |

| ElBelehy and Crispim22 | Egypt | Identifies adopted social sustainability practices in Egypt and determines factors affecting their implementation, focusing on institutional and stakeholder theories | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative): the research collected 6 managers’ opinions to gain deeper insight through in-depth interviews and a questionnaire answered by a total of 187 practitioners (managers, supervisors, and employees) from hospitality and tourism supply chains in Egypt | Social sustainability practices are adopted but limited to legal requirements and brand policies. Local suppliers boost the adoption of social practices | The study’s primary focus on five-star hotels could potentially limit the generalizability of the findings. This narrow focus might not adequately represent the broader hospitality and tourism industry in Egypt | Expand the scope of research to investigate various sustainability dimensions |

| Zaki16 | Egypt & Saudi Arabia | Assess circular economy practices in green hotels and the role of Industry 4.0 innovations on hotel performance. Develop a conceptual framework linking CE and HP | Quantitative approach: survey of 400 experienced hospitality professionals; data was analyzed using structural equation modeling | Circular economy practices significantly promote low-carbon behavior, and low-carbon behavior improves environmental performance. Finally, eco-friendly behavior strengthens the positive effect of low-carbon behavior on environmental performance | Focused on professionals’ views in two MENA countries; did not address consumer perspectives or long-term effects | Broaden to other regions, include consumer perspectives, and use longitudinal data |

Asadi21, also limit their scope to the impact of environmental practices. However, their study is narrowly confined to hotels and their guests, excluding other key stakeholders in the supply chain, such as tour operators and suppliers. This narrow focus, considering only the effects of environmental practices, overlooks other aspects of sustainability. This narrow lens is comparable to the approach of ElBelehy and Crispim22, which limits their study to the social aspects of five-star hotels and overlooks the multifaceted nature of sustainability once again.

Recent research has begun to explore the circular economy and its impact on hotel performance, with relevance in the MENA region. For instance, Zaki16 measured the effect of circular economy practices in eco-friendly hotels in Saudi Arabia and Egypt, finding that circular economy strategies (redesign, production, circulation, and recovery) positively influence hotel performance, and that Industry 4.0 innovations can augment this influence. However, Zaki16 primarily surveyed hotel employees and did not consider the views of other key stakeholders, the broader supply chain, the differences between categories of hotels, or the integration of social sustainability dimensions.

Khatter et al.33 identify barriers and drivers of environmentally sustainable practices in the Australian hotel industry but confine their exploration to environmental practices alone, not venturing into broader sustainability practices. Ghaderi et al.34 focus on the link between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and financial performance, specifically examining hotels within the supply chain, thereby providing a limited view of CSR’s broader impacts. Peña-Miranda et al.29 highlight a significant gap in not examining the impact and outcomes of sustainable practices through effective stakeholder-related indicators. This oversight highlights the need for research that evaluates the effectiveness of sustainability initiatives in terms of stakeholder engagement. Alameeri et al.28, provide a theoretical framework for categorizing and prioritizing sustainable practices based on expert opinions; however, they do not delve into their practical impacts and outcomes, resulting in a lack of empirical validation and practical insights.

Together, these studies illustrate a fragmented approach to understanding sustainable practices in the hotel industry. They highlight the need for a more integrated research approach that not only considers a wider range of sustainability practices and their outcomes but also encompasses a broader set of stakeholders, including those beyond hotels and their guests, and extends to the entire supply chain. This comprehensive approach offers a holistic view of sustainability in the hospitality sector. This study surpasses previous work, which has predominantly focused on environmental aspects, by encompassing a broader spectrum of sustainability dimensions and comparing their application in both local and international hotel chains. Furthermore, by adopting a supply chain view, this study extends the scope of SSCPs research beyond considering their impact on hotel guests. The creation of an integrated conceptual framework that links SSCPs with their drivers, barriers, and consequent impacts provides a more comprehensive perspective on sustainability in the hotel supply chain, bridging gaps in the existing literature that often overlook these connections.

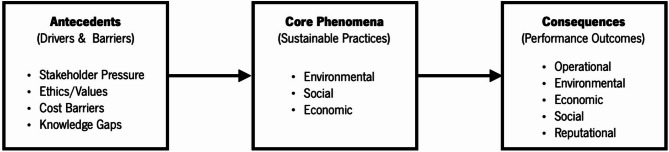

Initial conceptual framework

Based on the integration of the literature and the theoretical foundation of the stakeholder theory, an Initial Conceptual Framework (Fig. 1) was developed for this study to guide data collection and analysis. This framework integrates insights from empirical studies conducted in different geographical and methodological contexts. For instance, drivers and barriers extraction is inspired by Alameeri et al.28; Khatter et al.33, who stress the role of internal motivations (e.g., ethics, cost savings, brand image) and external pressures (e.g., regulations, customer preferences) in explaining the adoption of sustainability. Similarly, the typology of sustainable practices captures the multiple dimensions of approaches used by ElBelehy et al.22, Ibrahim et al.23, and Peña-Miranda et al.29. The performance results were based on those reported by Zaki16, Asadi et al.21, and Ghaderi et al.34.

Fig. 1.

Initial Conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain practices in hotels.

To address these deficiencies, the initial conceptual framework of the current study is based on three main dimensions: antecedents, core phenomena, and consequences.

Antecedents (Drivers and Barriers).

Antecedents encompass the drivers that motivate and the barriers that hinder the adoption of SSCPs in hotels. The key drivers identified include stakeholder pressure (from customers, regulators, and communities), ethical values, operational efficiency imperatives, and regulatory compliance. International hotel chains are subject to more intense stakeholder scrutiny and possess greater internal resources, facilitating the broader adoption of SSCPs. Conversely, barriers such as economic instability, knowledge deficits, limited financial resources, and contextual challenges, including those arising from Egypt’s post-revolution environment, impede the implementation of sustainable practices, especially in local hotels.

Core Phenomena (Sustainable Supply Chain Practices).

The central focus of this framework is the range of SSCPs adopted by hotels. These include responsible sourcing, waste reduction, energy and water efficiency, fair labor practices, and collaboration with suppliers and tour operators. The nature and level of these practices vary between hotel categories, with international chains generally having more advanced systems.

Consequences (Outcomes).

The use of SSCPs yields a range of results, from the obvious to the intangible. These include a better organizational reputation, more efficient resource utilization, cost savings, stronger customer loyalty, and increased stakeholder satisfaction. These results strengthen the business case for sustainability, supporting the long-term competitiveness of hotels.

Sustainability practices in the hotel supply chain

Environmental

There has been growing emphasis on environmentally responsible management within the hotel industry, with green hotels emerging as a prominent model for sustainable development35. Given the inherent functions of hotels, which involve significant energy and water consumption, as well as the generation of substantial solid waste, pose environmental challenges36. The scope of environmental supply chain management in the service industry extends beyond internal functions and incorporates integration with both customers and suppliers37.

Sustainability, a defining feature in the hotel industry over the last decade, promotes the broader application of green practices, such as eliminating plastic disposal items, reducing unnecessary resource use, and minimizing food waste38. Furthermore, the government policy regulating this sector necessitates the incorporation of environmentally sustainable management within their supply chains39. Social activists, environmentalists, and government agencies are debating the global scenario for eco-friendly and sustainable hotels, putting pressure on businesses to change their overall business plans38.

To foster a sustainable and environmentally friendly supply chain, collaboration among all stakeholders is imperative40, (as green supply chain management works to organize interrelationships with all stakeholders41. The relevant stakeholders comprise the internal hotel supply chain, including managers, employees, owners, clients, customers, and suppliers42, as well as external parties such as government agencies, recycling and waste disposal firms, organizations supporting environmental protection, and charitable organizations43.

The customer-facing segment of the supply chain plays a critical role in advancing comprehensive sustainability objectives. Zaki16 investigated the extent to which hotels promote environmental collaboration, specifically by enabling and encouraging customer participation in sustainability initiatives. Espino-Rodríguez and Taha44 posit that customer integration is the reciprocal of supplier integration and hinges on proactively discerning and meeting customer requirements. Furthermore, adopting green practices sends a positive signal about a hotel’s environmental protection efforts, which can serve as a motivator for customers to identify with and associate themselves with the business45. This leads to customers spreading positive word-of-mouth about the hotel, enhancing customer awareness and engagement, and taking action to support employees in the green service process46. Additional measures, as suggested by Moise et al.47, include recycling and reusing, energy efficiency and conservation, water conservation, landscaping, and purchasing locally and ecologically produced goods.

Social

Social sustainability practices in the hotel supply chain can be classified into three categories: organizational level, supply chain level, and community level. The organizational level includes provisions for fair wages and benefits, maintaining a safe and healthy environment, employees’ development and training, employees’ welfare, equity, prohibition of child and forced labor, and regulatory responsibility29,34,48,49. The supply chain level includes practices of local purchasing to support the local economy and offering education and training to suppliers to improve sustainable awareness29,49. Finally, the community level refers to hotel investments in creating employment and business opportunities for the surrounding community, as well as providing education, training, and healthcare facilities, to establish the firm as progressive in the eyes of stakeholders29,34,48,49.

Economical

The economic practices of SSCM aim to achieve long-term profitability while minimizing negative environmental and social impacts50. Studies indicate that implementing environmentally and socially responsible practices is only viable when the economic stability of the enterprise is assured51,52.

Economic sustainability practices in the hotel supply chain can be classified into two categories: organizational level and supply chain level. The organizational level includes cost reduction and efficient resource utilization20; furthermore, the supply chain level includes long-term relationships with suppliers53. Hotels extensively use a wide variety of resources and energy, including air conditioning, lighting, heating, kitchen equipment, laundry, cleaning, as well as construction activities, catering, laundries, swimming pools, spas, and gardens20. Strategic resource conservation practices have become essential for both environmental preservation and improving the financial performance of hotels. Energy-efficient lighting systems, reusing linen and towels, composting food waste, using renewable energy sources, reducing resource quantities, rainwater collection, reusing water and building materials, buying reusable materials, and recycling initiatives are some of the key practices in this regard54. Cerchione and Bansal20 highlighted that there is a positive association between hotels’ financial performance and resource conservation. On the other hand, neglecting to implement sustainable resource usage habits might cause irreversible harm to the ecosystem, endangering economic prosperity55.

To achieve better environmental and financial results, Asadi et al.21 emphasize the need for hotels to adopt clean and energy-efficient technology and equipment. They specifically call for lowering energy usage in lighting and air conditioning systems. Furthermore, Cingoski and Petrevska56 contend that energy-efficient efforts boost the hotel’s overall aesthetic reputation, lower operating expenses and maintenance system failures, increase profitability, and strengthen its position in the market, in addition to ensuring guest comfort.

Drivers and barriers

According to existing literature, an organization may be compelled to adopt sustainable practices in the supply chain due to various factors that can be categorized as either internal or external drivers. The key drivers in the adoption of SSCPs are pressures from stakeholders57, customers33, the government33,58, employees33, investors59, and competitors60. In contrast, studies suggest that for hotels, the primary drivers for SSCM adoption are internal factors, such as financial reasons, operational efficiency, ethics and values, and management commitment21,33,58,61,62 and the government regulations or legislation21,33,58,61,62 .

Barriers are impediments that can hinder or prevent the implementation of sustainable supply chain management practices63. They can be classified into internal and external factors64. External barriers to sustainability include the absence of government and industry regulations65,66, as well as competitive pressures67. Furthermore, a lack of understanding and awareness can hinder the adoption of SSCPs65,66. Hotels also face various barriers to sustainability, such as resource unavailability, high costs of sustainable practices, and resistance to adopting sustainable innovations33,65,66.

Stakeholder theory in the sustainable hotels’ supply chain

Stakeholder theory (ST), as formulated by Freeman68, analyzes the various individuals or parties—stakeholders—and their connections with organizations, which may influence business operations. These organizations may also feel that they are affected by the way society reacts to them in return. In hotels, when applied to sustainable supply chain management (SSCM), it offers a way of understanding why differing stakeholder pressures have so shaped both the adoption and implementation of sustainability practices57.

Our findings suggest that stakeholder theory is a key factor in explaining why hotels in Egypt adopt sustainable practices. For example, international hotel chains respond to global customer expectations and international standards by adopting advanced sustainability initiatives. In contrast, community needs, supplier relationships, and local regulations have a greater influence on local chains. This argument is validated from the ST point of view that the distribution of value and criticism should come more broadly than simply to shareholders. Who are the critics—employees, suppliers, customers, the government, NGOs, and the local community57?

Stakeholder pressures—both internal and external—play a decisive role in influencing a hotel organization to raise awareness of sustainability and subsequently implement it69. In our study, we find that a blend exists between ethical pressures (normative motives) and an incentive to increase name or operational efficiencies, which together shape hotels’ sustainability efforts. This has been mentioned in prior research70,71. Furthermore, stakeholders have varying impacts on hotels and their supply chain links, a point that has been observed in numerous studies70,72.

Outcomes of sustainable supply chain practices

The outcomes of sustainable supply chain management refer to the performance of supply chain practices within firms and encompass all sustainable dimensions of the triple bottom line — economic, environmental, and social73,74. Succeeding research endeavors have augmented the scope of outcomes by introducing two additional categories: operational outcomes75 and public image and reputation76. Companies that implement SSCM generally outperform their competitors in terms of economic performance and have reported advantages, including increased productivity, higher employee retention, fewer operational errors, and fewer accidents77,78. Specific results, such as improving reputation and gaining market share, meet the original motivator to adopt sustainable practices76.

Green supply chain management is one of the most effective strategies for reducing waste, pollution, and environmental degradation, as it has a significant impact on the environment79,80. Specific practices have been linked to positive hotel environmental performance: energy use reduction11, water use reduction81, waste reduction, reduction of carbon emissions, recycling, and reuse80, and green purchasing82. However, rather than preserving the environment, most environmental investments made in developing countries are meant to save operating costs.

By adopting SSCM practices, firms can enhance their capabilities and outperform competitors in terms of environmental efficiency and social responsibility. There are positive outcomes associated with social initiatives. For example, providing employees with training opportunities has a positive impact on their job satisfaction and self-confidence53. Furthermore, the corporate social responsibility practices of hotels influence the local community by strengthening altruistic intentions, such as promoting societal well-being and environmental protection83.

Some argue that investments in sustainability create exceptional value for shareholders84, which has a direct impact on the firm’s economic outcomes85. Chen andChen53 argue that the installation of energy-saving and water-efficient technologies or equipment in hotels leads to saving costs and Improved relationships with stakeholders, partners, and networks. The conservation of used resources has a positive impact on hotels’ financial performance86. Furthermore, energy-efficient initiatives can reduce the failures of maintenance systems and operating costs, improve profits, and impose market competitiveness56.

In terms of operational performance, firms have been incorporating sustainability into business performance measures87. Those that implement sustainable initiatives can enhance their operational efficiency and financial performance by reducing related economic, social, environmental, and political costs, and increasing access to critical resources86,88. Moreover, corporate social responsibility initiatives related to the quality of work-life have led to job satisfaction89.

Methodology

Research setting

Egypt has been selected as the context for the current study to make a contextual contribution, as the country’s economy has grown to be the second largest in Africa, the sixth largest in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and the 36th largest in the world90. Moreover, Egypt’s economy is among the most diverse in the MENA region, encompassing farming, industry, tourism, and services. Egypt’s GDP (gross domestic product) has nearly doubled from $20 billion in 1960 to $412 billion in 202088,90. Statista91 reports that the hospitality and tourism industry contributed approximately $ 12.6 billion to the Egyptian economy in 2018.

Furthermore, the industry employed 2.16 million people in 2021. It is expected that this sector will contribute 19.5 billion USD to the Egyptian economy by 202892. Furthermore, to promote social responsibility, the Egyptian government has implemented regulations and laws that provide incentives for donations and subsidies to various entities, including associations, public educational institutions, public hospitals, and scientific research institutions. According to the Presidency of the Arab Republic of Egypt93, these donations and subsidies are tax-deductible from the firm’s net profit if they amount to less than 10% of the net profit. However, Egypt ranks 127th out of 180 nations in the 2022 Environmental Performance Index, and its environmental performance in terms of Climate Change, Environmental Health, and Ecosystem Vitality is lower than that of its neighboring MENA nations94. Furthermore, approximately 61% of industrial and investment companies in Egypt do not contribute to supporting activities in any corporate social responsibility area95. These findings underscore the compelling need for research in the field of sustainability in the Egyptian context.

Research design

This research employed a qualitative, exploratory, multi-case study design, an approach that examines one or more instances of social phenomena, gathering large amounts of detailed data from these cases96. Multiple case study is the appropriate method when there is contemporaneity of the content and it is impossible to manipulate the behaviors97, as in our study. Furthermore, following the recommendations of Cooper et al.98, a case study was deemed appropriate because it necessitated detailed and intensive analyses to identify issues and generate insights that would make a contextual contribution. Case studies have already been widely used as a method to explain social and environmental practices in several sectors99. Furthermore, Robin et al.19, Pereira et al.100, Chen and Chen101 have used case studies as the basis for research on the social and environmental development of hotels.

This study aims to develop an integrated conceptual framework that connects sustainable supply chain practices (SSCPs) with their drivers, barriers, and outcomes. Stakeholder theory is used to explain the motivations behind implementing SSCPs. The research also examines how these factors vary or remain consistent across different hotel categories and explores the adoption of sustainable initiatives based on both normative and instrumental logic. This approach aligns with theory elaboration, which involves contextualizing a general theory and designing empirical research using existing conceptual models as a foundation102.

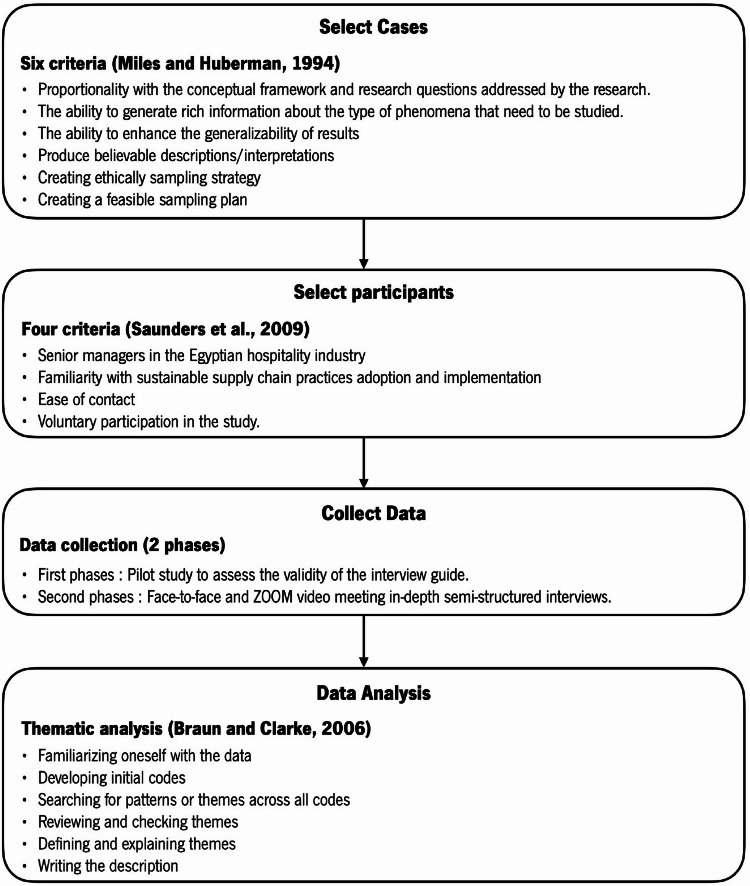

To answer the research questions, we conducted case studies within the Egyptian hotel industry. The case study methodology is an empirical approach suitable for improving our understanding of “real-world” events through an in-depth examination of a current phenomenon over which the researcher has little control97. According to Yin97, the evidence resulting from multiple-case studies is considered more convincing and yields more robust global results. This study employed an exploratory, multiple-case strategy (see, e.g.103,104, to examine sustainable practices in the hotel supply chain. The lack of literature combining the three dimensions of sustainability in the hotel supply chain (see, e.g.105,106, highlights the need to consider possible interactions between environmental, economic, and social sustainability practices to generate financial, environmental, and social value for stakeholders107,108. A multiple-case strategy allowed us to empirically analyze the sustainable practices of several cases in a fine-grained, in-depth, and contextualized way, as well as compare cases and map the SSCM of hotels in a developing country. Figure 2 presents an overview of the methodology.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the methodology.

We selected nine cases according to the six criteria for cases selection by Miles and Huberman104 that prescribe that the sampling strategy should (1) be relevant to the conceptual framework and the research questions addressed by the research; (2) be likely to generate rich information on the type of phenomena which need to be studied; (3) enhance the generalizability of the findings; (4) produce believable descriptions or explanations; be ethical, and be feasible. Indeed, in a multiple-case study design, some degree of generalizability can only be obtained within the context in which the study was conducted.

The sample includes Egyptian hotels of different categories (local chain 4-star hotels, local chain 5-star hotels, and international chain hotels), and from four different regions: Aswan, Luxor, the Red Sea, and Cairo. While the sample size is limited, the selection strategy ensures that the most relevant and diverse perspectives within the Egyptian hotel sector are included. The focus on major hotel categories and regional diversity allows the findings to reflect key trends and challenges in the industry. However, as with most qualitative research, the results are intended to provide in-depth, context-specific insights rather than statistical generalizations98.

Participant selection and data collection

The case studies are hotels of varying types (3 local chain 4-star, three local chain 5-star, and three international chain 5-star) to gather data between August 2020 and December 2022. Purposive sampling109 was implemented to select the participants guided by the four conditions proposed by Soundararajan and Brown110: (1) The involvement and pertinence of informants to the research context were assessed, leading to the establishment of the inclusion criterion “being manager at hotel in Egypt”; (2) their understanding about the adoption and execution of sustainability practices; (3) accessibility for communication of contact, and (4) willingness to voluntarily participate in the study. We conducted in-depth, face-to-face and Zoom video-conferencing semi-structured interviews with 2 participants in the pilot study and 18 in the main study. All participants are hotel managers in Egypt. Information about the selected hotels and interviewed participants is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Profile of interviewees and hotels involved.

| Hotel | Interview | Hotel | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Management area | Work experience | Location | Destination type | Category | Size | |

| Phase 1: Pilot study | |||||||

| Pilot 1 | Female | Marketing and sales | Extensive | Aswan | Cultural | Local chain | Medium |

| Pilot 2 | Male | Purchasing | Extensive | Aswan | International chain | Large | |

| Phase 2: Main study | |||||||

| ICHs.1 | Male | Sustainable program | Extensive | Aswan | Cultural | International chain | Medium |

| Male | Purchasing | Extensive | |||||

| ICHs.2 | Male | Purchasing | Extensive | Cairo | Urban & Cultural | International chain | Large |

| Female | Marketing and sales | Extensive | |||||

| ICHs.3 | Male | Purchasing | Extensive | Cairo | Urban & Cultural | International chain | Large |

| Female | Marketing and sales | Extensive | |||||

| LCHs5.1 | Male | General | Extensive | Aswan | Cultural | Local chain 5-Star | Medium |

| Female | Marketing and sales | Extensive | |||||

| LCHs5.2 | Male | General | Extensive | Red Sea | Natural | Local chain 5-Star | Large |

| Male | Purchasing | Extensive | |||||

| LCHs5.3 | Male | General | Extensive | Luxor | Cultural | Local chain 5-Star | Medium |

| Male | Purchasing | Extensive | |||||

| LCHs4.1 | Male | Purchasing | Extensive | Red Sea | Natural | Local chain 4-Star | Large |

| Male | Financial | Extensive | |||||

| LCHs4.2 | Male | General | Extensive | Red Sea | Natural | Local chain 4-Star | Large |

| Male | Purchasing | Extensive | |||||

| LCHs4.3 | Male | General | Extensive | Luxor | Cultural | Local chain 4-Star | Medium |

| Male | Purchasing | Extensive | |||||

Notes: Work experience - Limited: < 2 years, Moderate: 2–5 years, and Extensive: > 5 years; Hotel size - small hotel up to 100 rooms, medium hotel: 100–300 rooms, large hotel: >300–500 rooms.

Ethical approval for this study, including the experimental protocol, was obtained from the College of International Transport and Logistics Research Ethics Committee, Arab Academy for Science, Technology & Maritime Transport, on 10 July 2020. The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, which regulate ethical research involving human participants in non-medical fields. Furthermore, the study adhered to general ethical principles outlined in international research integrity frameworks.

The pilot study involved two managers, one each from a local chain hotel and another from an international chain hotel, to assess the validity of the interview guide. A face-to-face interview was conducted with the first, and one via ZOOM with the latter. In response to the feedback received during the pilot study, it was deemed necessary to refine the interview protocol questions. Hence, four questions, evenly split between environmental and social practices, were modified to broaden the investigation beyond the focal hotel and to encompass supply chain members. The participants in the pre-study were not included in the main study.

In the second phase (main study), two managers in each of the nine hotels analyzed were interviewed, in a total of 18 interviews (10 face-to-face and eight via ZOOM), 6 with managers from local chain 4-star hotels, six interviews with managers from local chain 5-star hotels, and 6 with managers from international chain hotels. The use of ZOOM was necessary due to the geographically dispersed location of the interviewees. All interviews were conducted in Arabic, recorded with the participant’s consent, and subsequently transcribed and translated into English for data analysis, resulting in 99 pages of transcripts. The average duration of the interviews was 45 min.

To enhance reliability111,112, a constant semi-structured interview guide was employed. Additionally, we maintained a record-keeping system for interviews and field notes to enhance the reliability of our findings64. The interview questions (refer to Appendix A) were derived from the SSCM literature, as detailed below, to ensure a solid rationale; however, issues were reformulated in language suitable for our interlocutors to understand. The interview guide includes an introduction and objectives of the study, general guidelines, questions about demographic information, and questions on the research topic that cover four themes:

SSCPs, including environmental, social, and economic aspects19,61,113;

Drivers sought to explore the motivating factors behind the hotel’s adoption of sustainable practices64,114;

Outcomes, aimed to gain an understanding of the benefits acquired through the application of the practices19,63.

Some of the questions are formulated in a precise manner, seeking a concrete answer, while others are more open-ended, encouraging the interlocutor to respond more freely. Depending on the course of the interview, new questions could arise to clarify and specify some of the answers.

Among the 31 interview questions, six specifically focus on evaluating the hotel’s environmental sustainability practices regarding its supply chain. These questions cover a range of topics, including organizational procedures related to environmental considerations in supplier selection, product purchasing, reverse logistics, and waste management, as well as initiatives aimed at reducing energy, water, and food consumption. The questions further explore monitoring processes for resource usage, collaborations with suppliers and tour operators to promote environmental improvement, and the hotel’s engagement with government agencies to ensure environmental compliance and support local sustainability efforts.

In parallel, of the 31 interview questions, nine are specifically tailored to assess social sustainability practices. These questions assess the organization’s commitment to employee development and welfare, as well as its initiatives promoting equity and supporting women, raising awareness of child and forced labor in the supply chain, and implementing formal procedures related to labor practices, human rights, and fair wages. Additionally, the questions delve into education and training for suppliers, collaboration on health and safety standards, preferences for local sourcing, and practices supporting local communities in Egypt.

Furthermore, within the set of 31 interview questions, three are dedicated to exploring economic sustainability practices. These inquiries center around the strategies employed for cost reduction without compromising service quality, specific examples of successful cost-saving initiatives, and the organization’s practices related to maintaining long-term purchasing relationships. The focus is on evaluating the hotel’s economic efficiency, cost management strategies, and commitment to fostering enduring relationships with suppliers.

In a related vein, out of the 31 interview questions, seven are specifically designed to uncover the drivers behind the hotel’s implementation of sustainable practices in its supply chain. These questions probe the rationale behind each environmental practice, the advantages gained, the influencers shaping the organization’s environmental practices, and the pursuit of green certifications. Additionally, the questions extend this inquiry to social practices, exploring influences, motivations, and reasons behind the creation of social programs and initiatives within the organization.

Lastly, among the 31 interview questions, five are dedicated to exploring the barriers that hinder the hotel’s implementation of sustainable practices in the supply chain. These questions investigate the difficulties encountered in applying both environmental and social practices, the disadvantages associated with their application, and the specific challenges faced in implementing such practices.

Data saturation was achieved through an iterative process of data collection and thematic analysis, continuing until no new themes or significant insights emerged. Specifically, after the seventh interview, recurring patterns and themes became evident, and by the 13th interview, theoretical saturation was reached, with 48 different codes applied. The final five interviews confirmed that no new themes, concepts, properties, or dimensions were uncovered. This approach aligns with established qualitative research standards, which define saturation as the point where additional data no longer yields new codes or themes. Recent literature suggests that saturation in studies with homogeneous objectives and populations is often reached within 9–17 interviews, supporting the adequacy of the sample size used in this research115,116.

Our research involved face-to-face interviews and onsite observations in five of the nine hotels selected. The hotels we have visited are ICHs.1, LCHs5.1, LCHs5.2, LCHs4.1, and LCHs4.2. Through on-site visits, one can observe firsthand how the hotels engage in sustainable practices. The ICH’s one hotel has been the most active in promoting various aspects of environmental sustainability. There were numerous waste separation bins in the guest areas, an obvious use of eco-friendly cleaning products, and a wide adoption of energy-saving lighting. Certificates for environmental work and ISO certifications were displayed in the hotel lobby, as well as in other public spaces, attesting to its commitment to sustainable standards. A careful reading of the employee handbook revealed sensitive information related to labor practices and ethics, demonstrating the hotel’s serious commitment to fair work. Its promotional materials also highlighted its sustainability initiatives. In this way, the guest would understand the extent of the hotel’s environmental responsibility. The first local 5-star hotel (LCHs5.1) was also unique in our sample as it incorporated pieces of craftsmanship as integrated elements into its interior design. The second local 5-star hotel (LCHs5.2), which features a waste and sewage management system incorporating composting, is an ecological option. Two local 4-star hotels (LCHs4.1 and LCHs4.2) were also noticeably geared toward sustainability, with LED lighting and significant evidence of sourcing locally produced goods. For the remaining four hotels (ICHs 2, ICHs 3, LCHs 5.3, and LCHs 4.3), we opted for Zoom meetings due to geographical distances. Despite not physically visiting these establishments, the virtual interviews facilitated a comprehensive exploration of their sustainable initiatives, ensuring a holistic representation of diverse practices across the entire sample.

Data analysis

We deployed the thematic analysis technique117 to code and analyze the interview data. First, we transcribed all interviews word for word, read them repeatedly to ensure familiarity with the content, and noted early ideas. Next, we developed the initial codes from the transcribed interviews. An inductive approach was adopted to generate all codes, themes, and dimensions from the interview data, which means that the codes and themes derive more from the concepts and ideas the researcher brings to the data during analysis118. We adopted a similar process to develop the second-order themes and aggregate themes, which involved collating the initial codes to form the next-order themes based on comparable topics and assembling them to generate main themes related to SSCPs, drivers, and barriers. Table 3 provides the step-by-step process of thematic analysis adopted in this study.

Table 3.

Step-by-step process of thematic analysis Braun and Clarke117

| Steps of thematic analysis | Description |

|---|---|

|

Familiarizing oneself with the data |

Significant time reading and re-reading the interview transcripts, taking notes on main ideas and thoughts, and keeping detailed records of all collected data |

|

Developing initial codes |

After data has been thoroughly examined and identify and develop the initial code |

|

Searching for patterns or themes across all codes |

Examine the initial codes to capture significant information related to the research question, such as SSCPs (significant statements or comments made by participants), drivers, and barriers. Comprehensive records of theme generation should be maintained |

|

Reviewing and checking themes |

Adjust and assess the initial themes, review them against the data, and ensure they accurately capture the essence of the research question |

|

Defining and explaining themes |

Once the themes have been reviewed and refined, defined, and explained them in detail; this may involve renaming themes, maintaining records of theme naming, and presenting distinct evidence to support each theme |

| Writing the description |

Finally, explain and unfold the coding analysis process in detail, including explanations of the specifics of the research findings. It is important to provide clear and concise explanations in writing to ensure the research is accurately understood |

The collected data were analyzed with ATLAS.ti 23, a computer-aided qualitative data analysis software program. ATLAS.ti 23 software assisted in organizing the interview transcripts to develop the analysis. This tool enabled us to systematically code and analyze the data, including counting the frequency of codes mentioned in the passages, and to efficiently identify and compare codes across the different categories of hotels (local chain 4-star hotels, local chain 5-star hotels, and international chain hotels). Furthermore, ATLAS.ti 23 helped to ensure the accuracy and consistency of our analysis, as we were able to easily track and compare codes across the different types of hotels.

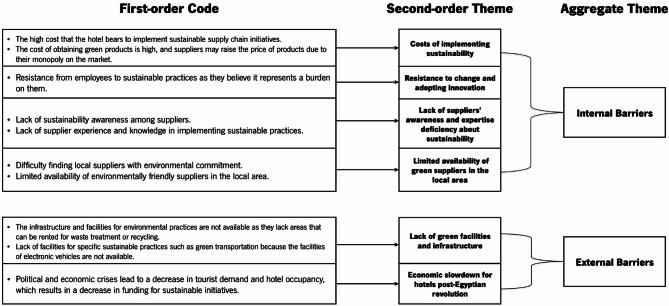

The data analysis process generated two aggregate themes related to Environmental Sustainability Practices (SPs) for the hotels (at the company or supply chain level), three aggregate themes for Social SPs (organizational, supply chain, and community levels), two aggregate themes for Economic SPs (organizational and supply chain), and two aggregate themes for drivers and barriers (internal and external). The analytical coding method for deriving aggregate themes is illustrated in Figs. 3 (Environmental SPs), 4 (Social SPs), 5 (Economic SPs), 6 (drivers), and 7 (barriers). We further analyzed the drivers in consideration of stakeholder theory. A central feature of qualitative research is the removal of doubts regarding the validity and reliability of the results64. We ensured validity by corroborating the findings through multiple sources of evidence111. We triangulated data through site visits, verbatim comments, and careful attention to various explanations related to sustainability across hotels111.

Fig. 3.

Coding structure of aggregate dimensions for environmental pratices derived from interviews content.

Fig. 4.

Coding structure of aggregate dimensions for social pratices derived from interviews content.

Fig. 5.

Coding structure of aggregate dimensions for economic pratices derived from interviews content.

Fig. 6.

Coding structure of aggregate dimensions for drivers pratices derived from interviews content.

Fig. 7.

Coding structure of aggregate dimensions for barriers pratices derived from interviews content.

Findings

The following sub-sections discuss the similarities and differences among 4-star local chain hotels (LCHs4), 5-star local chain hotels (LCHs5), and international chain hotels (ICHs) associated with SSCPs and their drivers and barriers (see Tables 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Table 4.

Mentions to environmental sustainability practices by managers of case hotels.

| Environmental Sustainability | Hotel category | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Chain Hotels 4* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

Local Chain Hotels 5* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

International Chain Hotels (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

|

| Organizational level | |||

|

Waste Reduction Practices (c = 6) |

10/36 | 23/36 | 32/36 |

|

Energy Use Reduction Practices (c = 2) |

4/12 | 5/12 | 12/12 |

|

Water Use Reduction Practices (c = 3) |

4/18 | 9/18 | 10/18 |

|

Reducing the Carbon Emission (c = 3) |

0/18 | 0/18 | 12/18 |

|

Recycling and Reuse (c = 4) |

2/24 | 8/24 | 12/24 |

|

Green Certifications (c = 2) |

4/12 | 4/12 | 4/12 |

| Green training (c = 2) | 0/12 | 3/12 | 4/12 |

| Supply chain level | |||

|

Green Supplier Selection (c = 7) |

12/42 | 17/42 | 37/42 |

|

Green Purchasing (c = 7) |

10/42 | 11/42 | 11/42 |

|

Green Supply Chain Collaboration with Suppliers (c = 3) |

0/18 | 1/18 | 12/18 |

|

Green Supply Chain Collaboration with Tour Operators (c = 3) |

9/18 | 11/18 | 13/18 |

|

Supply Chain Collaboration with Logistics and Green Providers (c = 5) |

6/30 | 9/30 | 13/30 |

|

Green Supply Chain Collaboration with Government agencies (c = 3) |

0/18 | 1/18 | 4/18 |

|

Collaboration with Green Consultant (c = 4) |

2/24 | 6/24 | 1/24 |

|

Number of mentions by the interviewees |

63/324 | 108/324 | 177/324 |

Notes: c - number of subcategories in the category; n - number of hotels from each category; m - number managers interviewed in each hotel; c*n*m = number of mentions if each manager mentions each subcategory once.

The number of mentions reflects the total frequency with which each practice was discussed by interviewees. Managers could refer to the same practice multiple times within a single interview, and each mention was counted separately. Thus, the totals may exceed the number of interviewees or hotels.

Table 5.

Mentions to social sustainability practices by managers of case hotels.

| Social sustainability | Hotel category | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Local chain Hotels 4* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

Local chain Hotels 5* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

International chain Hotels (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

|

| Organizational level | |||

|

Development and Training (c = 4) |

6/24 | 11/24 | 12/24 |

| Equity (c = 6) | 15/36 | 12/36 | 16/36 |

| Ethics (c = 2) | 12/12 | 20/12 | 54/12 |

|

Employees Welfare (c = 3) |

10/18 | 11/18 | 21/18 |

|

Maintaining Health and Safety Environment (c = 4) |

16/24 | 29/24 | 29/24 |

| Wages (c = 4) | 17/24 | 12/24 | 17/24 |

|

Prohibition of Child labor (c = 2) |

5/12 | 6/12 | 9/12 |

|

Prohibition of Forced labor (c = 2) |

10/12 | 8/12 | 7/12 |

|

Regulatory Responsibility (c = 2) |

11/12 | 14/12 | 9/12 |

|

Women Centric Initiatives (c = 6) |

4/36 | 5/36 | 11/36 |

| Supply chain Level | |||

| Local sourcing (c = 2) | 12/12 | 12/12 | 22/12 |

|

Education and Training for Suppliers (c = 2) |

0/12 | 3/12 | 8/12 |

|

Ensuring Health and Safety (c = 2) |

1/12 | 0/12 | 13/12 |

|

Prohibition of Child labor (c = 2) |

12/12 | 5/12 | 21/12 |

|

Prohibition of Forced labor (c = 2) |

6/12 | 3/12 | 16/12 |

| Community Level | |||

| Philanthropy (c = 7) | 12/42 | 17/42 | 32/42 |

|

Number of mentions by the interviewees |

149/312 | 168/312 | 297/312 |

Notes: c - number of subcategories in the category; n - number of hotels from each category; m - number managers interviewed in each hotel; c*n*m = number of mentions if each manager mentions each subcategory once.

The number of mentions reflects the total frequency with which each practice was discussed by interviewees. Managers could refer to the same practice multiple times within a single interview, and each mention was counted separately. Thus, the totals may exceed the number of interviewees or hotels.

Table 6.

Mentions to economic sustainability practices by managers of case hotels.

| Economic sustainability | Hotel category | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Chain Hotels 4* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

Local Chain Hotels 5* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

International Chain Hotels (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

|

| Organizational level | |||

| Cost reduction (c = 5) | 8/30 | 8/30 | 16/30 |

|

Efficient resource utilization (c = 5) |

19/30 | 37/30 | 46/30 |

| Supply chain level | |||

|

Long-term relationship with suppliers (c = 4) |

8/24 | 11/24 | 16/24 |

|

Number of mentions by the interviewees |

35/84 | 56/84 | 78/84 |

Notes: c - number of subcategories in the category; n - number of hotels from each category; m - number managers interviewed in each hotel; c*n*m = number of mentions if each manager mentions each subcategory once.

The number of mentions reflects the total frequency with which each practice was discussed by interviewees. Managers could refer to the same practice multiple times within a single interview, and each mention was counted separately. Thus, the totals may exceed the number of interviewees or hotels.

Table 7.

Mentions to sustainability drivers by managers of case hotels.

| Drivers | Hotel category | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Chain Hotels 4* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

Local Chain Hotels 5* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

International Chain Hotels (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

|

| Normative internal drivers | |||

|

Ethics and values (c = 6) |

15/36 | 20/36 | 59/36 |

|

Top management commitment (c = 6) |

4/36 | 7/36 | 48/36 |

| Instrumental internal drivers | |||

|

Operational efficiency (c = 9) |

37/54 | 52/54 | 87/54 |

|

Tour operators’ pressure and collaboration (c = 3) |

7/18 | 21/18 | 16/18 |

| Instrumental external drivers | |||

|

Government regulations/ legislation (c = 6) |

25/36 | 30/36 | 20/36 |

| Market (c = 2) | 11/12 | 14/12 | 11/12 |

|

Reputation and competitive advantages (c = 4) |

20/24 | 32/24 | 24/24 |

|

Number of mentions by the interviewees |

118/216 | 176/216 | 265/216 |

Notes: c - number of subcategories in the category; n - number of hotels from each category; m - number managers interviewed in each hotel; c*n*m = number of mentions if each manager mentions each subcategory once.

The number of mentions reflects the total frequency with which each practice was discussed by interviewees. Managers could refer to the same practice multiple times within a single interview, and each mention was counted separately. Thus, the totals may exceed the number of interviewees or hotels.

Table 8.

Mentions of sustainability barriers by managers of case hotels.

| Barriers | Hotel category | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Chain Hotels 4* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

Local Chain Hotels 5* (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

International Chain Hotels (n*m = 3*2 = 6) |

|

| Internal barriers | |||

|

Costs of implementing sustainability (c = 2) |

5/12 | 6/12 | 2/12 |

|

Resistance to change and adopting innovation (c = 1) |

6/6 | 2/6 | 1/6 |

|

Lack of suppliers’ awareness and expertise deficiency about sustainability (c = 2) |

0/12 | 2/12 | 5/12 |

|

Limited availability of green suppliers in the local area (c = 2) |

2/12 | 1/12 | 3/12 |

| External barriers | |||

|

Lack of green facilities and infrastructure (c = 2) |

0/12 | 0/12 | 7/12 |

|

Economic slowdown for hotel post-Egyptian revolution (c = 1) |

4/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 |

|

Number of mentions by the interviewees |

17/60 | 12/60 | 18/60 |

Notes: c - number of subcategories in the category; n - number of hotels from each category; m - number managers interviewed in each hotel; c*n*m = number of mentions if each manager mentions each subcategory once.

The number of mentions reflects the total frequency with which each practice was discussed by interviewees. Managers could refer to the same practice multiple times within a single interview, and each mention was counted separately. Thus, the totals may exceed the number of interviewees or hotels.

Environmental sustainability practices

Egyptian hotels implement environmental practices related to waste reduction, energy use reduction, and water use reduction; reducing carbon emission; recycling, and reuse; green certifications; green training; green supplier selection; green purchasing; green collaboration with suppliers; green collaboration with tours operators; collaboration with logistics and green providers; green collaboration with government, and collaboration with a green consultant (See Fig. 3). Our exploration of environmental practices encompasses the coding structure of aggregate dimensions for environmental practices employed by hotels. Table 4 summarizes the number of mentions of ecological sustainability practices by the managers of case hotels.

4-star local chain hotels

The LCHs4 in the sample prioritize waste, water use, and energy use reduction as their Organizational Environmental SPs: “We monitor the consumption of energy, water, and food, and we always strive to reduce waste and preserve the environment.” (General Director, LCHs4*2). Two of the three LCHs also implement recycling and reuse initiatives, including collaborating with recyclers who collect their waste and recycle it, as well as supporting corporations and NGOs. All three hotels prioritize green certifications to enhance their reputation and present to tour operators.

Regarding the supply chain level of environmental practices, the LCHs4 prioritize Environmental SPs related to selecting suppliers based on their ecological characteristics. This was mentioned 12 times by the three LCHs4. As noted by a purchasing director, “A committee composed of members of the hotel’s purchasing department also makes a field visit to the supplier’s factories to make sure the environment reduces resource consumption.” (Purchasing Director, LCHs4*3).

Green product purchasing is also essential, mentioned 10 times by the hotel managers. The hotels also collaborate with tour operators, offering green services and amenities to promote long-term contracts: “In the beginning, one of the tour operators sent a group of trainers to the hotel to train employees on how to implement environmental practices and how to preserve the environment by training them on how to reduce resource and energy consumption and others.” (Financial Director, LCHs4*1). Collaboration with logistics and green service providers was mentioned six times, where specialized companies are contracted to manage waste disposal. For example, “We contract with a specialized company in waste management that collects waste from the hotel, processes it, recycles it, and safely disposes of some of it.” (Purchasing Director, LCHs4*2). Two of the three hotels (LCHs4*1 and LCHs4*2) also highlight the importance of consulting with green consultants to improve the quality of their Environmental SPs.

5-star local chain hotels

LCHs5 prioritize waste reduction practices (mentioned 23 times by the interviewed managers). Regular check-ups and awareness programs are also in place. In addition to reducing water use, these hotels prioritize recycling and reuse to conserve resources. Three LCHs5 monitor energy consumption to reduce usage (mentioned 5 times). Holding a green certification is also emphasized to enhance public image: “One of the main reasons for the hotel’s focus on obtaining environmental certificates and implementing environmental initiatives was to increase its sales and improve its image among tour operators.” (General Director, LCHs5*1). Regarding green training in hotel operations, the hotels overcome the employees’ resistance to applying Environmental SPs by training and introducing their importance to the hotel and community:

“One of the most important things that we are currently focusing on is environmental procedures. For this reason, the hotel has contracted with a consulting company specializing in sustainability to train the hotel employees on how to apply sustainable practices and to conduct regular inspections twice a month.” (General Director, LCHs5*2).

Regarding the supply chain level of Environmental SPs, the LCHs5 prioritize green supplier selection practices (17 mentions). The interviewees also emphasized the importance of applying green supplier selection practices, as environmentally responsible suppliers are a crucial step in achieving a sustainable supply chain and enhancing the hotel’s image among guests. Purchasing green products is also highly valued (11 mentions): “We have a set of requirements that must be available in the product before making a purchase, and one of the most important of these requirements is that these products should not contain any harmful materials to the environment and should be environmentally friendly.” (General Director, LCHs5*3).