Abstract

During sexual development, Neurospora crassa inactivates genes in duplicated DNA segments by a hypermutation process, repeat-induced point mutation (RIP). RIP introduces C:G to T:A transition mutations and creates targets for subsequent DNA methylation in vegetative tissue. The mechanism of RIP and its relationship to DNA methylation are not fully understood. Mutations in DIM-2, a DNA methyltransferase (DMT) responsible for all known cytosine methylation in Neurospora, does not prevent RIP. We used RIP to disrupt a second putative DMT gene in the Neurospora genome and tested mutants for defects in DNA methylation and RIP. No effect on DNA methylation was detected in the tissues that could be assayed, but the mutants showed recessive defects in RIP. Duplications of the am and mtr genes were completely stable in crosses homozygous for the mutated potential DMT gene, which we call rid (RIP defective). The same duplications were inactivated normally in heterozygous crosses. Disruption of the rid gene did not noticeably affect fertility, growth, or development. In contrast, crosses homozygous for a mutation in a related gene in Ascobolus immersus, masc1, reportedly fail to develop and heterozygous crosses reduce methylation induced premeiotically [Malagnac, F., Wendel, B., Goyon, C., Faugeron, G., Zickler, D., et al. (1997) Cell 91, 281–290]. We isolated homologues of rid from Neurospora tetrasperma and Neurospora intermedia to identify conserved regions. Homologues possess all motifs characteristic of eukaryotic DMTs and have large distinctive C- and N-terminal domains.

Keywords: cytosine DNA methyltransferase‖mutagenesis‖RIP‖silencing‖epigenetics

It is becoming increasingly clear that eukaryotic organisms command a variety of genetic systems to counter invasive DNA. The filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa has at least four distinct but potentially interrelated genome defense systems. In vegetative tissues, a process called “quelling” silences arrays of transcribable sequences (1). Similar RNA-induced silencing processes are found in plants (2) and animals (3, 4). DNA methylation constitutes a second silencing system in vegetative cells. DNA sequences with compositions distinct from that of native sequences are recognized and densely methylated (ref. 5; M.F., D. Margineantu, A. Roche, V. Miao, and E.U.S., unpublished work). Methylation interferes with transcript elongation (6). In diploid sexual tissue, meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA reversibly inactivates unpaired genes during meiosis (7, 8). Work in our laboratory revealed a permanent form of silencing during premeiotic sexual development, termed repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) (9–11). RIP operates in a pairwise fashion on linked and unlinked DNA repeats leaving in its wake C:G to T:A transition mutations and, typically, dense DNA methylation (for reviews, see refs. 12 and 13). The incompletely understood relationship between these two signatures motivated this study.

The mechanism of RIP is difficult to study by classical approaches of biochemistry and genetics because the specialized ascogenous tissue in which RIP occurs is microscopic and contains a nucleus from each parent (14). Genetic findings showed that RIP involves G to A changes or C to T changes, but not both (15). The favored model for RIP involves unrepaired deamination of C or mC to U or T, respectively, perhaps catalyzed by a DNA methyltransferase (DMT) (12). To investigate this possibility, we searched for potential DMTs that might be involved in RIP. We found that the genome of Neurospora encodes two putative DMTs that sport the six most highly conserved motifs characteristic of eukaryotic DMTs (16, 17). One (DIM-2) had already been identified by classical genetics and shown to be responsible for all known DNA methylation, i.e., methylation in vegetative hyphae, conidia, and ascospores (18, 19). Here we report the characterization of the second putative DMT. We show that it is critical for RIP and therefore name it RID (RIP Defective).

Materials and Methods

Neurospora Strains, Media, and Growth Conditions.

Strains of N. crassa used are listed in Table 1. We also used Neurospora tetrasperma (FGSC 1270), Neurospora intermedia (FGSC 2316), Neurospora pannonica (FGSC 7221), Neurospora africana (FGSC 1740), Neurospora galapagosensis (FGSC 1739), and N. terricola (FGSC1889). Unless otherwise noted, standard Neurospora growth conditions and genetic techniques were used (20, 21). Scoring for mtr and am mutants has been described (22).

Table 1.

N. crassa strains

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| N1 | mat a | FGSC#988 |

| N150 | mat A | FGSC#2489 |

| N623 | mat A his-3 | FGSC#6103 |

| N268 | mat a; amec+; am132 inl | 10 |

| N270 | mat A; amec+; inl | 10 |

| N271 | mat a; amec+; inl | 10 |

| N277 | mat A; amec+ | 10 |

| N571 | mat a his-2 nuc-1; am132 inl; am+∷hph+∷am+ec53 | 22 |

| N1255 | mat a; mtr+∷hph | 19 |

| N1256 | mat A; mtr+∷hph | 19 |

| N1445 | mat a his-3; am132 inl | 5 |

| N1963 | mat A his-3∷rid5′Δ | This study |

| N1977 | mat A ridRIP1 his-3∷riddridR1; am∷hph∷amRIP | This study |

| N2147 | mat a ridRIP2 his-3∷riddridR2 | This study |

| N2148 | mat a ridRIP4 his-3∷riddridR3 | This study |

| N2149 | mat a; mtr+∷hph | This study |

| N2150 | mat A ridRIP1 his-3∷riddridR1; mtr+∷hph | This study |

| N2151 | mat a; mtr+∷hph | This study |

| N2152 | mat A ridRIP1 his-3∷riddridR1; mtr+∷hph | This study |

| N2240, N2241 | mat A ridRIP1 his-3 | This study |

| N2242, N2243, N2244 | mat A ridRIP1 his-3; am132 inl | This study |

| N2245 | mat A his-3 | This study |

| N2246, N2247 | mat A his-3; am132 inl | This study |

| N2248, N2249 | mat A ridRIP1; amec+ | This study |

| N2250 | mat A ridRIP1 | This study |

| N2252 | mat a ridRIP4; amec+ | This study |

| N2257 | mat a ridRIP4; his-3 | This study |

Preparation of DNA and PCR.

Genomic DNA was isolated from Neurospora as previously described (23). The rid gene was amplified from N. crassa, N. tetrasperma, and N. intermedia DNA with primers 977 (5′-CTCCCCGGGATGGCCGAGCAAAACCCCTTTGTTATA-3′; XmaI cloning site underlined) and 980 (5′-TTGCGGCCGCGTCGTCGAAAAGCTCCATTGGCTCCTTC-3′; NotI cloning site underlined) by PCR using Taq, Pfu Turbo or Herculase polymerase with buffers recommended by the manufacturer (Stratagene) under the following conditions: 94°C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 10 sec, 50°C for 20 sec; and 72°C for 3 min on a Hybaid (Middlesex, U.K.) Omnigene temperature cycler. To safeguard against changes introduced by PCR, products of five independent PCR reactions were pooled for each sequencing reaction.

Plasmids.

A 1.7-kb EcoRV–SpeI fragment of the PCR-amplified rid fragment of N. crassa was inserted into SmaI + XbaI-digested pBM61 (24) to create pMF238. Strain N623 was transformed by electroporation as previously described (24, 25). For expression of RID in Escherichia coli, the rid ORF was PCR-amplified (primers 977 and 980) with Herculase polymerase, digested with XmaI and NotI, and inserted into pGEX5–2 (Amersham Pharmacia). Production of recombinant RID followed standard procedures (26).

Nucleic Acid Analyses.

We followed procedures previously described for Southern (5), Northern, and reverse transcription–PCR analyses (6, 19) and for isolation of cDNA clones (26). Southern hybridizations probes for his-3, mtr, Fsr-63 (ψ63), and am were previously described (5). The 2.5-kb rid fragment was used as a probe to find defective rid alleles, to assay for DNA methylation, and to reveal gene duplications. DNA sequencing was performed by the University of Oregon and the Oregon State University central sequencing facilities. A list of sequencing primers is available on request. Protein sequences were aligned with clustalw on the Biology Workbench web site (http://workbench.sdsc.edu/CGI/BW.cgi). Accession numbers for the sequences used: M.NgoVII (Neisseria gonorrhoeae), AAA86270; CMT1 (Arabidopsis suecia), AAC02670; CMT1 (Arabidopsis arenosa), AAC02671; CMT1 (Arabidopsis thaliana), AAC02663; CMT2 (A. thaliana), AAK69757; CMT3 (A. thaliana), AAK69756; MET1 (A. thaliana), AAA32829; MET1 (Nicotiana tabacum), BAA92852; MET1 (Daucus carota), T14288; MET2 (D. carota), T14289; MET1 (Pisum sativum), T06370; MET1 (Zea mays), AAG15406; Masc1 (Ascobolus immersus), AAC49849; Masc2 (A. immersus), CAB09661; DIM-2 (N. crassa), AAK49954; RID (N. crassa), AF500227; RID (N. intermedia), AF500228; RID (N. tetrasperma), AF500229; RID (N. galapagosensis), AF500230; RID (N. terricola), AF500231; DNMT3 (Danio rerio), AAD32631; DNMT3A (Homo sapiens), Q9Y6K1; DNMT3B (H. sapiens), Q9UBC3; DNMT1 (H. sapiens), P26358; Dnmt1 (X. laevis), JC5145; Dnmt1(Gallus gallus), Q92072; Dnmt1 (Mus musculus), NP_034196; Dnmt1 (Paracentrotus lividus), Q27746. The complete sequence of the Emericella nidulans DmtA gene will be published elsewhere (D. W. Lee, M.F., E.U.S., and R. Aramayo, unpublished work). The Aspergillus fumigatus DmtA sequence was deduced from sequences available at TIGR (http://tigrblast.tigr.org/ufmg/). Three ridRIP alleles were partially sequenced (ridRIP1, AF500232; ridRIP2, AF500233; ridRIP4, AF500234).

Results

We searched Neurospora sequence databases for potential DMT genes by using the blastx program (27) with various known and putative DMT sequences as query. One homologue with significant similarity was found in addition to the previously known DMT gene, dim-2 (19). The putative DMT gene found on BAC clone 2J23 in the MIPS N. crassa sequence database (http://www.mips.biochem.mpg.de/proj/neurospora/) was eventually named rid (see below). The predicted RID protein is most similar to Masc1, a putative DMT involved in sexual development and MIP (methylation induced premeiotically) in A. immersus (28). MIP inactivates duplicated genes by DNA methylation much as RIP inactivates duplicated genes by point mutations and sometimes methylation in Neurospora (13). We amplified the longest predicted rid reading frame by PCR from wild-type N. crassa genomic DNA and mapped rid to linkage group IL by restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses (29, 30) (Fig. 1A). We did not detect any additional putative DMT homologues in the ≈98% completed N. crassa genome sequence (http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/neurospora).

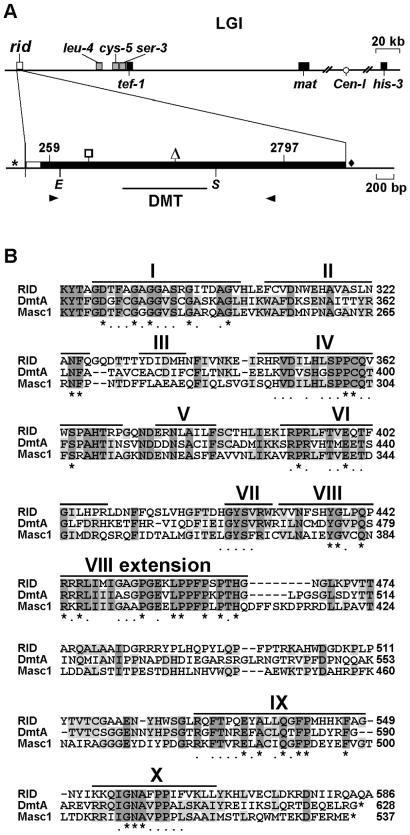

Figure 1.

Structure of rid and the DMT domain of its predicted protein. (A) Segment map of N. crassa linkage group I (top line) and structure of rid (bottom line). The rid gene was mapped near the mating type (mat) locus. Genetic and physical maps were aligned by identifying leu-4, cys-5, and ser-3 (based on orthologs from yeast) and tef-1 (30). The positions of the centromere (Cen-I) and his-3 are shown. The rid coding region spans nt 259-2797 of the rid transcript (filled boxes). One intron (nt 17–177; open box) is present in the untranslated leader sequence. The triangle marks the position of an intron in Ascobolus masc1 and Aspergillus dmtA that is absent from Neurospora rid. A consensus TATA promoter element is indicated by the asterisk, and a putative polyadenylation signal is indicated by a diamond. The 286-aa DMT domain is indicated by a line below the transcript. Arrowheads represent primers used to amplify rid. Restriction sites (E = EcoRV and S = SpeI) used for targeting to his-3 are shown. The nonsense mutation identified in mutant rid alleles is indicated by the open square. (B) Alignment of the catalytic DMT domain of RID homologues from N. crassa (RID), A. fumigatus (DmtA), and A. immersus (Masc 1), DMT motifs are indicated by Roman numerals. Residues identical in all eukaryotic DMTs are marked by asterisks; positions that have conservative substitutions are indicated by dots.

As a first step to investigate the expression of rid, we searched N. crassa expressed sequence tag (EST) databases and screened developmental cDNA libraries (31). No EST was found, and no rid cDNAs were detected in either conidial or mycelial libraries. We isolated and sequenced a full-length rid cDNA clone from a perithecial cDNA library, however, which showed that rid is expressed. It is also consistent with the idea that rid is involved in RIP. The rid transcript covers 3,315 bp and contains a 2,538-bp ORF without introns (Fig. 1A). The untranslated leader sequence contains a 161-bp intron at the same position that Ascobolus masc1 has a 49-bp intron (28). Northern hybridizations failed to detect rid transcript in 7- or 12-h-old vegetative tissue or in sexual tissues 5, 9, or 11 days postfertilization, but low levels of the transcript were detected in vegetative and sexual tissues by reverse transcription-PCR (data not shown).

Conceptual translation from the likely start codon of rid predicts an 845-aa tripartite protein. Various conserved regions have been identified in bona fide or putative DMTs (17, 32, 33). The center domain (amino acids 283–569) has all motifs found in known eukaryotic DMTs in the conventional order, including the AdoMet-binding and catalytic Pro-Cys sites (motifs I and IV, respectively; Fig. 1B). The RID N-terminal domain does not contain previously identified motifs, except for a poor match to a bromo-adjacent homology (BAH) motif, which we also found in Ascobolus Masc1 and which had been identified previously in several other putative and known DMTs (33, 34). Some DMT motifs (e.g., II, III, V, and VII) are poorly conserved in eukaryotes overall but are similar in RID and related proteins (see below). RID sports a long C-terminal domain that lacks conserved motifs. This domain is rich in short DNA repeats, and the codon bias of this domain is strikingly different from that of Neurospora genes generally (35).

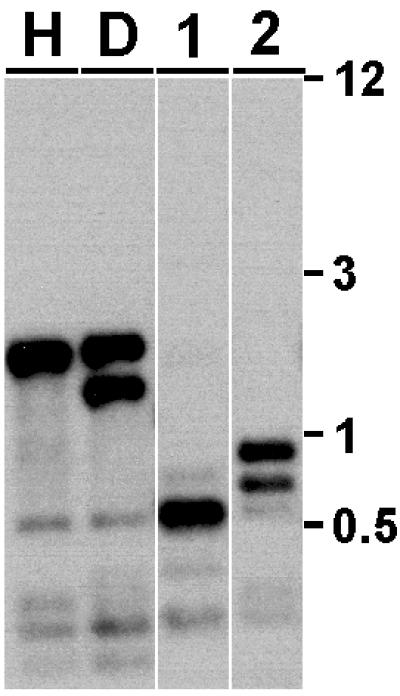

To investigate the function of RID, we took advantage of RIP as a tool for gene disruption (e.g., see ref. 36) to mutate rid. Unlinked gene-sized duplications are typically inactivated at frequencies of ≈50% by RIP. We targeted a 1.7-kb rid fragment to the his-3 locus on linkage group IR of strain N623, isolated a homokaryotic rid duplication strain (Fig. 2, Dup., N1963), crossed it to strain N571 and screened progeny by Southern hybridization with a rid probe. Numerous strains showed mutant alleles, as evidenced by DNA methylation (data not shown) and restriction fragment length polymorphisms within both duplicated segments of the gene (illustrated by representative strains in Fig. 2). We isolated and sequenced several heavily mutated rid alleles of the native locus. Allele ridRIP1 was found to have several missense mutations and a nonsense mutation at predicted amino acid 143, well upstream of the conserved DMT domain. Because rid is tightly linked to the mating type (mat) locus, we generated independent null alleles of rid in strains of each mating type to test for effects of rid disruptions in homozygous crosses. Alleles ridRIP2 and ridRIP4 (mat a strains N2147 and N2148, respectively) were found to bear nonsense mutations in the same codon as the ridRIP1 allele (mat A strain N1977). Backcrosses to his-3 strains yielded progeny that carried only the mutated endogenous copy of rid (Fig. 2). Strains bearing the ridRIP1 or ridRIP4 alleles were used for subsequent experiments. No rid transcript was detected in N1977 or N2148 by reverse transcription–PCR (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Generation of rid mutants by RIP. Genomic DNA from host strain N623 (H), the rid his-3∷rid duplication strain N1963 (D) and strains bearing ridRIP1 (N2248, 1) and ridRIP4 (N2257, 2) alleles was digested with RsaI, transferred to nylon membranes, and probed with a 2.5-kb rid fragment to detect novel fragments resulting from RIP. Molecular weight size standards (kb) are shown on the right.

To determine whether RID is involved in RIP, we tested rid mutants for their ability to inactivate three different gene duplications in various strain backgrounds. To assay RIP frequencies, we used unlinked duplications of the mtr gene, which encodes a permease responsible for uptake of neutral aliphatic and aromatic amino acids, and unlinked and linked duplications of the am gene, which encodes an NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase (30). We found that rid function is not essential for fertility; even homozygous rid crosses produced abundant ascospores, in contrast to the situation with masc1 mutants of Ascobolus, which are sterile in homozygous crosses (28). The frequency of mutation by RIP normally depends on the “age” of the cross; spores produced early show lower frequencies of RIP than those produced later (37). We therefore tested random ascospores harvested at various times (13, ≈21, and 31 days postfertilization).

In one set of experiments, we crossed ridRIP strains bearing unlinked mtr+ duplications (Table 2). As controls, we crossed rid+ wild-type strains N1 and N150 to rid+ mtr duplication strains N1256 and N1255, N2149 or N2151, respectively (Type I, Table 2). To assay for possible effects of rid on RIP in heterozygous crosses where the mtr duplication is not in the same nucleus as the mutated rid allele (Type II, Table 2), ridRIP1 strain N1977 was crossed to mtr duplication strain N1255. Sibling progeny that carried rid+ alleles and mtr duplications (N2149 and N2151) were backcrossed to N1977 in a second set of heterozygous reciprocal crosses. No effect of rid mutations on RIP frequencies was observed in these crosses. We next asked whether RIP is affected in crosses in which the ridRIP allele is contained in the same nucleus as the mtr duplication (Type III, Table 2). We crossed ridRIP1 mtr duplication strains N2150 and N2152 to wild-type N1. As in Type II heterozygous crosses, RIP frequencies were unchanged (Type III, Table 2). To assay the effect of rid in homozygous crosses, we crossed N2150 and N2152 to N2148, a ridRIP4 strain with a single mtr+ gene (Type IV, Table 2). No RIP was detected. We observed a few p-fluorophenylalanine+ strains in direct plating assays of progeny from some mtr crosses, but analysis of the mtr locus revealed no mutations. In contrast, progeny from control and heterozygous crosses showed heavily mutated and methylated mtr alleles (data not shown). N1977 was also crossed to a his-3 strain (N1445) to isolate progeny without the mutated, partially deleted rid copy at his-3. Strains N2240 to N2247 were used in heterozygous or homozygous ridRIP crosses to verify results obtained with strains N1977 and N2148. No significant differences in RIP frequency were obtained when comparing single copy ridRIP and ridRIP duplication strains.

Table 2.

Effect of rid disruptions on RIP frequency in unlinked copies of mtr

| Type | Relevant genotype | RIP frequency, %* |

|---|---|---|

| I | rid+ mtr+ X rid+ mtr+ mtrec+ | 73 (106/290) |

| II | ridRIP mtr+ X rid+ mtr+ mtrec+ | 70 (1094/3140) |

| III | rid+ mtr+ X ridRIP mtr+ mtrec+ | 66 (118/354) |

| IV | ridRIP mtr+ X ridRIP mtr+ mtrec+ | 0 (0/2944) |

Random progeny of mtr crosses described in the text were analyzed by spot-testing on FPA-containing medium 31 days after fertilization. Because only one parent carries an mtr duplication, the actual RIP frequency is calculated as (FPA+/total) × 200. Values for individual type I–III crosses varied from 60 to 80%.

We also tested the effect of rid on RIP frequencies with an unlinked am duplication (Table 3). Control crosses (Type I) were performed with am duplication strains N270 and N271 to wild-type N1 and N150, respectively. To assay the effect of rid in heterozygous crosses in which the am duplication was not in the same nucleus as ridRIP (Type II, Table 3), we crossed ridRIP4 strain N2148 to rid+ am duplication strain N277. We also constructed unlinked am duplication strains by crossing ridRIP1 strain N1977 to rid+ strain N268, which bears an ectopic am+ allele and a deletion of the endogenous am gene. N2250 (ridRIP1) was crossed to rid+ am duplication strain N271. We assayed RIP in heterozygous crosses in which the am duplication was in the same nucleus as ridRIP (Type III, Table 3), by crossing N2248 and N2249 to wild type (N1) and by crossing N2252 (ridRIP4) to N2245. As was the case with mtr duplications, RIP frequencies were not affected in heterozygous am ridRIP crosses. It is interesting that RIP frequencies did not depend on whether the duplications tested were in the same or opposite nucleus with ridRIP (Type II and III cross), in contrast to the effect of masc1 on MIP in Ascobolus (28). To assay the effect of rid in homozygous crosses (Type IV, Table 3), we crossed N2252 to N2250, N2240 and N2241, and N2257 to N2248 and N2249, respectively. In no case did we observe RIP in homozygous crosses with unlinked am duplications.

Table 3.

Effect of rid disruptions on RIP frequency in unlinked copies of am

| Type | Relevant genotype | RIP frequency, %,

after*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 days | 21 days | 31 days | ||

| I | rid+ am+ X rid+ am+ amec+ | 44 (13/58) | 62 (36/116) | 64 (64/199) |

| II | ridRIP am+ X rid+ am+ amec+ | 24 (11/92) | 42 (20/96) | 49 (47/193) |

| III | rid+ am+ X ridRIP am+ amec+ | 36 (18/98) | 57 (56/198) | 60 (60/200) |

| IV | ridRIP am+ X ridRIP am+ amec+ | 0 (0/151) | 0 (0/236) | 0 (0/285) |

Random progeny of am crosses described in the text were harvested 13, 20–24 (∼21), and 31 days after fertilization, analyzed by spot testing on growth medium containing glycine or alanine, and RIP frequency determined as (Gly−/total) × 200. Values for individual type I–III crosses varied from 21 to 50% (13 days), 35 to 66% (21 days), and 46 to 71% (31 days).

Because RID shows hallmarks of eukaryotic DMTs, we assayed DNA methylation in vegetative cells of rid mutants by restriction analyses and Southern hybridizations with known methylated sequences of N. crassa as probes (Fig. 3). No global or localized changes in DNA methylation were found, consistent with previous indications that the DIM-2 DMT is responsible for all DNA methylation in vegetative tissues of N. crassa (18, 19).

Figure 3.

Disruption of rid does not affect DNA methylation in vegetative cells. Genomic DNA from rid+ (WT; N150) and ridRIP1 (RIP1; N1977) strains was digested with Sau3AI (S) or DpnII (D), fractionated in 1% agarose, stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr), transferred to a nylon membrane, and probed sequentially for the indicated methylated chromosomal regions. Molecular weight size standards (kb) are shown on the left.

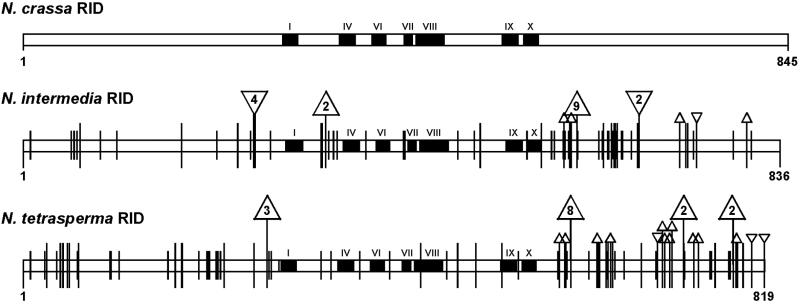

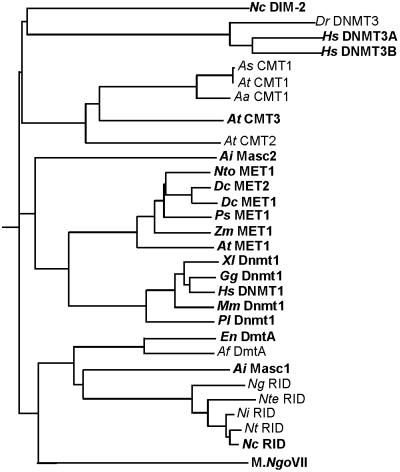

To determine which regions of RID have been conserved over evolutionary time, we isolated and sequenced part or all of rid from several other Neurospora species. We sequenced the complete rid gene from N. intermedia and N. tetrasperma and fragments of the gene from N. terricola and N. galapagosensis. We found that RID is highly conserved across the whole genus Neurospora, consistent with the possibility that heterothallic, pseudohomothallic, and homothallic species of Neurospora are all competent for RIP (Fig. 4 and data not shown). All differences between the amino acid sequences of N. crassa and N. intermedia RID fall outside of conserved motifs. The same is true for differences between N. crassa and N. tetrasperma RID, except for three changes on the edges of motifs VIII and IX. Even in the N-terminal domain, which is not similar to previously identified proteins in other organisms, the amino acid sequence is largely conserved among these Neurospora species, but the C-terminal is more variable. Predictably, the genes from N. crassa, N. intermedia, and N. tetrasperma are more closely related to each other than to those of the homothallic Neurospora (Fig. 5). Among the homothallics, N. terricola and N. pannonica, and N. galapagosensis and N. africana, respectively, form distinct groups (data not shown), confirming results obtained previously with gpd and mating type genes (38) and with dim-2 (R.L.W., M.F., and E.U.S., unpublished work). To gain insight into the relationship of RID to other known or putative DMTs, we used clustalw (39) to align their respective central domains (Fig. 5). On the basis of our alignment, eukaryotic DMTs and DMT-like proteins fall into four major groups: (i) de novo DMTs characterized by DNMT3-type proteins and Neurospora DIM-2; (ii) plant chromomethylases; (iii) “maintenance methyltransferases” of the animal DNMT1 or the plant MET type; and (iv) Masc1/RID homologues. On the basis of available genomic data from plants and metazoans, the latter group may be specific to the fungi.

Figure 4.

Structure of predicted RID proteins from N. crassa, N. intermedia, and N. tetrasperma. Conserved motifs in the DMT domain are shown as black boxes (Roman numerals). Conservative and nonconservative substitutions in the protein sequences of RID from N. intermedia and N. tetrasperma, relative to that of N. crassa, are indicated by short and long vertical ticks, respectively. The number of amino acids inserted or deleted is indicated within the inverted and upright triangles, respectively; small triangles indicate single insertions or deletions. The 8- and 9-aa deletions in the C-terminal domain of N. intermedia and N. tetrasperma RID remove one copy of a 24-bp identical direct repeat in the N. crassa DNA sequence.

Figure 5.

Relationship between bona fide and putative DNA methyltransferases. Eukaryotic DMTs fall into four major classes: (i) de novo DMTs (DIM-2 and DNMT3) from N. crassa (Nc) and animals (Dr, D. rerio; Hs, H. sapiens); (ii) chromomethylases (CMT) from plants (At, A. thaliana; As, A. suecia; Aa, A. arenosa); (iii) maintenance DMTs (MET- and DNMT1-like) from plants (Nto, N. tabacum; Dc, D. carota; Ps, P. sativum, Zm, Z. mays), fungi (Ai, A. immersus Masc2), and animals (Xl, X. laevis; Gg, G. gallus; Mm, M. musculus; P/, P. lividus); and (iv) Masc1 homologues (Masc1, DmtA, RID) from fungi (En, E. nidulans; Af, A. fumigatus; Ng, N. galapagosensis; Nte, N. terricola; Nt, N. tetrasperma). Alignment of the catalytic domain of bona fide and putative DMTs was performed by clustalw analyses with default settings (39). The sequence of the bacterial DNA methyltransferase most closely related to RID, Neisseria gonorrhoeae VII methylase (M.NgoVII), was used as an outgroup. Proteins with known in vivo and/or in vitro DMT activity or phenotypes potentially associated with DNA methylation are shown in bold, whereas putative DMTs identified only by sequence homology are shown in plain type. For simplicity, we have not included the Dnmt2 group of putative DMTs (e.g., see ref. 33), because to date there are no indications that these proteins are involved in methylation.

Discussion

The discovery of RIP provided the first example of an apparent genome defense system (12). In the intervening years, additional homology-based systems capable of silencing illegitimate sequences have been discovered. These include MIP in Ascobolus (40), transcriptional and posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants (2), RNA interference in animals (41), and quelling (1) and meiotic silencing in Neurospora (7, 8). Because RIP occurs in specialized dikaryotic ascogenous tissue, the process has been recalcitrant to classical genetic and biochemical approaches. One important question concerns the mechanism that generates the hallmark C:G to A:T mutations. Two alternative pathways for the enzymatic generation of C to T mutations by a DMT have been proposed (12). One hypothetical pathway involves de novo DNA methylation of C in paired sequences, followed by catalyzed deamination of some fraction of the resulting 5mC to give T. The second pathway involves direct deamination without the release of 5mC-DNA. The proposed mechanism for all DMTs involves an intermediate that is thought to be ≈104 times more likely to be spontaneously deaminated than cytidine itself (42–44). A DMT may carry out initial steps typical of cytosine methylation but proceed from the intermediate to direct deamination of carbon 4. Evidence of this reaction has been obtained with bacterial DMTs, especially when AdoMet is limiting (45–47). Our finding that RID is essential for RIP supports the idea that a DMT or DMT-like enzyme is involved in RIP by one of these mechanisms.

The cardinal question remaining is whether RID has DMT and/or deaminase activity. Preliminary attempts to detect either activity in a preparation of recombinant RID failed (data not shown). Ascobolus masc1 is thought to encode a de novo DMT because its disruption resulted in lack of MIP, but expression of recombinant Masc1 also resulted in inactive protein (28). It seems likely that accessory proteins are required for catalytic activity of both Masc1 and RID. Instances of DNA methylation associated with products of RIP reflect methylation that is initiated in the sexual phase of the life cycle (perhaps during RIP) and then propagated by “maintenance methylation” (22, 48). These observations are consistent with the possibility that RID is a bona fide DMT.

Interestingly, RID is not required for vegetative or sexual development, unlike its homologue from Ascobolus, Masc1 (28). Crosses of strains carrying rid at both his-3 and its native locus did not exhibit meiotic abnormalities, aberrant asci, or low germination of ascospores. The significance of these observations is highlighted by the recent discovery of a meiotic silencing process (MSUD) that inactivates unpaired genes (7, 8). MSUD presumably operated on rid in some of our crosses and would have resulted in arrest of development or loss of fertility if the gene played an important role in meiosis. Given the striking parallels between RIP in Neurospora and MIP in Ascobolus and the strong structural similarities between Neurospora RID and Ascobolus Masc1, it seems likely that these proteins carry out similar or identical functions. What could account for the fact that disruption of Masc1, but not RID, blocks sexual development? One possible explanation is related to the absence of RIP but higher level of DNA methylation in Ascobolus relative to Neurospora (49). DNA methylation is known to be dispensable in Neurospora (18, 19), consistent with evidence that nearly all methylation is associated with sequences mutated by RIP (E.U.S., N. Tountas, S. Cross, B. Margolin, and A. Bird, unpublished work). It is not known whether methylation is essential in Ascobolus. If Masc1 and RID are indeed sexual-specific DMTs, lethality of masc1 mutants may reflect a requirement for methylation in Ascobolus.Perhaps the absence of RIP in Ascobolus leaves methylation solely responsible for the silencing of selfish DNA.

Our identification of RID, the first known component of the RIP machinery, should facilitate progress in elucidating the mechanism of RIP. Because RIP depends on DNA pairing during premeiosis, we expect to find factors that interact with RID during or shortly after pairing. A thorough understanding of this prototypical homology-based silencing system should provide insight into other genome defense systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jon Murphy for technical assistance. We appreciate insights and comments on the work by many current and former members of the Selker lab. M.F. is grateful for encouragement by Matthew Sachs, David Perkins (who helped find a name for this methyltransferase homologue), and Bob Metzenberg. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to M.F. (CA73123) and E.U.S. (GM35690).

Abbreviations

- DMT

DNA methyltransferase

- RIP

repeat-induced point mutation

- RID

RIP Defective

- MIP

methylation induced premeiotically

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database [accession nos.: RID (N. crassa), AF500227; RID (N. intermedia), AF500228; RID (N. tetrasperma), AF500229; RID (N. galapagosensis), AF500230; RID (N. terricola), AF500231; N. crassa ridRIP1, AF500232; ridRIP2, AF500233; ridRIP4, AF500234].

References

- 1.Cogoni C. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:381–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaucheret H, Beclin C, Fagard M. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3083–3091. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.17.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery M K, Kostas S A, Driver S E, Mello C C. Nature (London) 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elbashir S M, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Nature (London) 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miao V P, Freitag M, Selker E U. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:249–273. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rountree M R, Selker E U. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2383–2395. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aramayo R, Metzenberg R L. Cell. 1996;86:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiu P K, Raju N B, Zickler D, Metzenberg R L. Cell. 2001;107:905–916. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00609-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selker E U, Stevens J N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8114–8118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selker E U, Garrett P W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6870–6874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cambareri E B, Jensen B C, Schabtach E, Selker E U. Science. 1989;244:1571–1575. doi: 10.1126/science.2544994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selker E U. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:579–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selker E U. Adv Genet. 2002;46:439–450. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(02)46016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selker E U, Cambareri E B, Jensen B C, Haack K R. Cell. 1987;51:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watters M K, Randall T A, Margolin B S, Selker E U, Stadler D R. Genetics. 1999;153:705–714. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar S, Cheng X, Klimasauskas S, Mi S, Posfai J, Roberts R J, Wilson G G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bestor T H. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2395–2402. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foss H M, Roberts C J, Claeys K M, Selker E U. Science. 1993;262:1737–1741. doi: 10.1126/science.7505062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kouzminova E A, Selker E U. EMBO J. 2001;20:4309–4323. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis R H, De Serres F J. Methods Enzymol. 1970;17A:47–143. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis R H. Neurospora: Contributions of a Model Organism. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford Univ. Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irelan J T, Selker E U. Genetics. 1997;146:509–523. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo Z, Freitag M, Sachs M S. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5235–5245. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margolin B S, Freitag M, Selker E U. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1997;44:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margolin B S, Freitag M, Selker E U. Fungal Genet Newsl. 2000;47:112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malagnac F, Wendel B, Goyon C, Faugeron G, Zickler D, Rossignol J L, Noyer-Weidner M, Vollmayr P, Trautner T A, Walter J. Cell. 1997;91:281–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metzenberg R L, Stevens J N, Selker E U, Morzycka-Wroblewska E. Neurospora Newsl. 1984;31:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkins D D, Radford A, Sachs M S. The Neurospora Compendium. Chromosomal Loci. San Diego: Academic; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson M A, Kang S, Braun E L, Crawford M E, Dolan P L, Leonard P M, Mitchell J, Armijo A M, Bean L, Blueyes E, et al. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;21:348–363. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1997.0986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finnegan E J, Kovac K A. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;43:189–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1006427226972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colot V, Rossignol J L. BioEssays. 1999;21:402–411. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199905)21:5<402::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callebaut I, Courvalin J C, Mornon J P. FEBS Lett. 1999;446:189–193. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edelmann S E, Staben C. Exp Mycol. 1994;18:70–81. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selker E U. In: More Gene Manipulations in Fungi. Bennet J W, Lasure L, editors. New York: Academic; 1991. pp. 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singer M J, Kuzminova E A, Tharp A, Margolin B S, Selker E U. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1995;42:74–75. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poggeler S. Curr Genet. 1999;36:222–231. doi: 10.1007/s002940050494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossignol J-L, Faugeron G. Experientia. 1994;50:307–317. doi: 10.1007/BF01924014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishikura K. Cell. 2001;107:415–418. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santi D V, Wataua Y, Matsude A. In: International Symposium on Substrate-Induced Irreversible Inhibition of Enzymes. Seiler N, Jung M J, Koch-Weser J, editors. Strasbourg, France: Elsevier/North–Holland; 1978. pp. 291–303. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu J C, Santi D V. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4778–4786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bestor T H, Verdine G L. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:380–389. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen J-C, Rideout W M, III, Jones P A. Cell. 1992;71:1073–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yebra M J, Bhagwat A S. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14752–14757. doi: 10.1021/bi00045a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macintyre G, Atwood C V, Cupples C G. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:921–927. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.921-927.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singer M J, Marcotte B A, Selker E U. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5586–5597. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goyon C, Barry C, Gregoire A, Faugeron G, Rossignol J L. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3054–3065. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]