Abstract

Objective:

Primary care-based literacy promotion enhances caregiver-child shared reading and child language outcomes, yet variation in implementation may dilute its impact. This study examines expert perspectives on intended outcomes of literacy promotion, as well as its core components, those necessary to achieve intended outcomes, and components that are recommended but adaptable to context.

Methods:

We purposively sampled healthcare and policy experts in primary care-based literacy promotion from the U.S. and Canada for online, in-depth interviews. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed iteratively engaging emergent and a priori codes based on the COmponents and Rationales for Effectiveness Fidelity Method and the team’s prior work to identify themes.

Results:

We achieved saturation after 22 interviews with 24 participants (16 U.S. participants, 8 Canadian). We identified four themes: 1) Traditionally, literacy promotion focused on enhancing preliteracy skills and school readiness. Over time, this outcome has evolved to include fostering early relational health as a foundational goal; 2) Core components include a trusted clinician delivering a strength-based, family-centered message, while modeling developmentally-informed shared reading; 3) Components that are adaptable to setting and context include literacy-rich clinical environments and community resource referrals; 4) Experts diverged on whether providing a children’s book during literacy promotion is essential, but there was congruence that book provision alone is insufficient.

Conclusion:

Experts identified strength-based, family-centered guidance from a trusted clinician with developmentally-focused modeling as core to support intended outcomes of early relational health and school readiness. This understanding can inform training and healthcare improvement activities aimed at optimizing primary care-based literacy promotion.

Keywords: Literacy promotion, pediatrics, primary care, shared reading, early childhood, implementation science

Introduction

Low literacy is associated with poor physical and mental health and high acute health service use.1 Caregiver-child shared reading enhances cognitive, language, and social-emotional skills that support long-term wellbeing.2–5 Consequently, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) identify literacy promotion as essential to primary care.6,7

Reach Out and Read (ROR), the most studied and widely disseminated model is implemented in > 6,200 clinics, and >39,000 clinicians are trained in ROR in the United States (U.S.).8 The ROR model includes a new children’s book, anticipatory guidance and clinician modeling, and literacy-rich clinical environments.8 While a compelling body of evidence supports ROR’s effectiveness, more work on ROR implementation is needed. First, while earlier studies on ROR largely focused on outcomes like shared reading frequency and language development,9–13 more recent work has examined additional outcomes including parental mental health,14 developmental screening and preventive visits,15,16 and parent-clinician relationships.17 Work that clearly defines ROR’s intended outcomes and how this understanding evolved over time could help guide future research. Second, more work is needed to understand which components drive impact. The few studies examining ROR implementation note variation especially in the extent to which clinicians model shared reading i.e., demonstrate developmentally appropriate, interactive reading to caregivers during preventive visits.18–20 This is notable since modeling is considered a best practice and is associated with enhanced home literacy environments.21 Previous work found a dose-response pattern.21 With no components as the reference, one component (book or guidance) alone was not associated with enhanced home literacy environments, two components (most commonly book and guidance) were associated with enhanced home literacy environments (standardized beta = 0.27), and three components (book, guidance, and modeling) had the greatest magnitude (standardized beta = 0.33). These findings suggest that the ROR components delivered may impact treatment effects. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) distinguishes between an intervention’s “core components” i.e., components that are necessary to achieve intended outcomes, and its “adaptable periphery” i.e., elements that are recommended but adaptable to context.22 While the AAP policy statement and the CPS position statement provide guidance for pediatric clinicians to promote literacy during preventive visits,6,7 and describe models and strategies, they do not specify core components. Work that enhances the field’s understanding of intended outcomes, core components, and hypothesized mechanisms of action can potentially inform scalable healthcare improvement efforts to amplify ROR’s impact and future research.

This study aims to identify the intended outcomes and core components of literacy promotion from the perspective of healthcare and policy experts. Since both the AAP and CPS have identified literacy promotion as a standard of care, we interviewed experts from the U.S. and Canada to compare and gain additional perspective. Importantly, while models based on ROR and similar initiatives are practiced in Canada, the ROR organization is established in the US, but not in Canada.

Methods

Frameworks and study design

This study is informed by CFIR22 and engages the Components and Rationales for Effectiveness (CORE) Fidelity Method.23 CFIR consists of five major domains (the intervention, inner and outer setting, the individuals involved, and implementation process) that interact in complex ways to influence effectiveness. CFIR conceptualizes interventions as having core components and an adaptable periphery. The CORE Fidelity Method, a structured approach to define core components of behavioral interventions,23 informed both the development and analyses of the interviews. The CORE method consists of three stages: (1) Gather information, (2) Synthesize information, and (3) Draft and implement a CORE model that distinguishes core components from the adaptable periphery. Here, we focus on the first stage which includes literature review and expert interviews. Expert interviews offer insight into perspectives on intended outcomes, core components, and hypothesized mechanisms that are difficult to elicit from other sources. Building on our team’s prior scoping review that focused on ROR implementation,24 this study uses interviews with healthcare and policy literacy promotion experts to gain these insights. We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) reporting guidelines.25 The Rutgers Health IRB approved this study. All participants provided verbal consent.

Study team and reflexivity statement:

Our interdisciplinary team, with expertise in basic science, community health, nursing, sociology, and pediatrics, brought perspectives shaped by our professional training, literacy promotion experiences, and personal backgrounds. Frequent meetings facilitated collaborative interpretation and reflection, enabling us to identify themes a single author might have missed. However, our positionality may have also unintentionally shaped the research by overlooking certain information.

Participants and settings

We purposively sampled literacy promotion experts from the U.S. and Canada to compare and gain additional perspectives since both the AAP and CPS have long-standing statements on literacy promotion. We sought recognized experts and focused on those with healthcare and policy expertise given our interest in primary care settings. We defined expertise based on national, state, or provincial leadership roles focused on literacy promotion, publication records, and/or consultation with the ROR national center. We emailed potential participants an explanation of the study purpose and an invitation to participate with a response rate of 79%.

Data collection

We conducted online interviews between November 2023-October 2024 using a video-conferencing platform (i.e., Zoom). One study team member (LM) conducted all interviews and was trained by team members with extensive experience in qualitative research (MEJ and MBP). The team developed an interview guide (Supplemental Table 1) featuring open-ended questions and planned probes, informed by the CORE method, a literature review, and the team’s prior experience with ROR implementation and related research. The interviewer followed the guide, adapting it based on the flow of interviews and emerging themes. Interviews lasted between 25–75 minutes. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by team members. We conducted interviews until our team collectively determined that we had reached saturation (i.e., when additional interviews did not yield new information) on perceptions of intended outcomes and core components during the analysis meetings described in more detail below.26

Analysis

We analyzed interviews iteratively as data were collected based on the approach recommended by Crabtree and Miller.27 We used NVivo software to assist with data management (NVivo 14. Lumivero; 2023). Multiple team members listened to audio recordings, reviewed transcripts, and prepared reflective narrative summaries in preparation for biweekly team meetings. The team developed a codebook of emergent and a priori codes based on the first five interviews, guided by the CORE Fidelity Method23 and the team’s prior work, which included a scoping review focused on ROR implementation. Our team employed codes grounded in the CORE Fidelity Method to facilitate the specification of the core components of literacy promotion; the CORE Fidelity Method specifically led to the development of codes characterizing the theoretical rationale and/or empirical evidence for a core component, as well as expert insights. At least three team members (LM, RS, and JD) coded the remaining interviews using and refining the codebook as additional interviews were conducted and analyzed. Biweekly meetings incorporated opportunities for discussion, review of transcripts, narrative summaries, coded data, and resolution of disagreements through consensus. We identified themes through persistent engagement with the interview text, narrative summaries, coded data, and team discussion. We then compared and contrasted themes based on whether the respondents were from the U.S. or Canada.

Results

We conducted 22 interviews with 24 participants. In two cases, the primary participant asked if they could invite a second person to join the interview. The participation of the second person did not result in any substantive differences when compared to other interviews. Sixteen participants were from the US, and eight were from Canada. Most of the participants (n=15) were pediatricians (general or developmental behavioral pediatricians). The remaining participants (n=9) came from other fields including child psychiatry, family medicine, nursing, and policy. We identified four major themes with the first focused on intended outcomes, and the other three focused on core components (Table 1).

Table 1:

Themes and representative quotations

| Theme | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Traditionally, literacy promotion focused on enhancing preliteracy skills and school readiness. Over time, this outcome has evolved to include fostering early relational health as a foundational goal that underlies its effects on preliteracy skills and school readiness. | “So thinking, you know, the old or the traditional logic model used to be like, you know, you read books to kids, kids learn more words. The more words they know, the more likely they are to have success with formal reading. But I think understanding… that like development occurs within the context of relationships and for a brain to develop to its full potential it really needs to feel safe … so… sharing books with kids can also be a way to promote like a feeling of a safe and stable nurturing environment even in the midst of other chaos…” “I think that Reach Out and Read… has started off as a program that’s centered in the primary care setting, it’s connecting families with children’s books and giving that advice on the best way to share those books with the child and you know sensibly for the point of increasing that child early literacy right but also to… enhance that bond between the parent or caregiver and the child… that early relational health piece that bond that you’re building and nurturing and fostering between parent, caregiver and the child is really fundamental to so many aspects of their life.” |

| Core components include a (1) trusted clinician delivering (2) a strength-based, family-centered message while (3) modeling developmentally informed shared reading interactions. | “So, it takes advantage of that relationship that providers have …with the parents and also, the fact that it sets that different tone for the visit. It aids in so many different areas to be able to have a warming connection with the family.” “This is truly strength based. The message here is truly that your voice is the center of your baby’s world your baby wants to be in your arms look how she turns to you when you talk this is a strength-based incredibly positive message for parents …” “When you model in the exam room you often find yourself saying ok she’s sort of interested in me telling her what the pictures are now let’s see how she reacts when you do it. Ooo look how she turns to you. I’m ok but you’re the one that she’s really paying attention to and you know I think it’s a good way into helping parents feel that first of all they have this great power and potential.” |

| Additional components that are adaptable to setting and context include literacy-rich clinical environments and referrals to other community resources | “In some of our clinics, we have the best literacy rich waiting rooms, which are great to have, but not all clinics can do that. For whatever reason, some clinics might even not be allowed to put posters on the wall. You know, so like that really differs from clinic to clinic. Ideally kids are sitting in a waiting room filled with books and filled with posters about reading instead of a TV on.” “And of course, addressing all the basic needs issues, right? It’s a little silly to be talking about reading when the family has just told you that they are homeless now because they got kicked out of their apartment or they lost their jobs or whatever the case may be, right? Like, you can’t… you can talk about reading all you want, but if you’re not addressing basic needs as well, then you know that’s not going to help either.” |

| Experts diverged on the extent to which providing a children’s book during literacy promotion is essential, but there was congruence that the book should be culturally tailored if provided and book provision is insufficient on its own. | “But number one is like you have to give the book… You want to make sure that the family has the means to do the intervention when they leave your office? So, you have to get the children’s book. That’s a core component.” “I don’t think the book is essential because I think it’s the smallest component of Reach Out and Read. Which I know sounds silly, but I think the biggest component is the person giving the message and how they deliver it. And I think the book is the reminder of that message.” “… Reach Out and Read is not a book provision program, … it works because it’s… more than book provision… It’s like, here’s a book. let’s open it and look at it with your kid. In a way that models those behaviors, because reading with young children is not always intuitive and doesn’t always look like reading…so it’s, you know, maybe it’s I didn’t read a single word on this page. I just opened a book and let the kid, like, move the pages. Or I made animal noises and I didn’t read any of the words and so I think …another way that it works is helping families to understand what is developmentally appropriate for their child’s interaction with the book at a given phase so that they don’t over or under expect something from their kid and then get frustrated…” |

Theme 1: Traditionally, literacy promotion focused on enhancing preliteracy skills and school readiness. Over time, this outcome has evolved to include fostering early relational health (ERH) as a foundational goal that underlies its effects on preliteracy skills and school readiness.

Experts emphasized that during the early years as ROR started to expand from one site to thousands of sites across the U.S., clinicians focused on promoting preliteracy skills to enhance school readiness. They also noted how earlier studies reflected this emphasis, with language development as the primary outcome. However, experts shared that a focus on supporting ERH has grown overtime.

“So, I think that’s kind of evolved over time… when ROR first started it was much more focused on the early literacy piece … And then most of the early studies looked at … language development … how often parents were reading to kids... I think as ROR evolved … I think probably the biggest benefit …. [is] that … establishment of early healthy relationships that … in the long run is going to be the biggest impact of ROR.”

Experts noted that the promotion of safe, secure, and positive caregiver-child interactions through literacy activities is now recognized as a foundational goal of literacy promotion that underlies its other effects.

“...you could have the traditional definition of early literacy promotion which would be only focused about helping develop the early skills that will … help that child develop literacy skills down the line. But … before that even happens, it’s about the connection and bonding with the child that sets the stage for learning in general.”

Intended outcomes as described by U.S. and Canadian participants were largely similar.

Theme 2: Core components include a (1) trusted clinician delivering (2) a strength-based, family-centered message while (3) modeling developmentally informed shared reading interactions.

Experts noted that messaging was significant for families and a driver of behavioral change when it came from a trusted clinician. A strong clinician-caregiver-child relationship encouraged uptake of the advice.

“I think it works first in that it comes from a trusted person in a child’s life. So, it comes from often a pediatrician or pediatric medical home somewhere that typically a parent really trusts and believes in. I think that is one big reason why ROR works.”

To leverage the strong and trusted caregiver-clinician relationships, experts highlighted the need for continuous training. Experts noted that clinicians must have strong buy-in and a champion to keep them motivated.

“Another core component … is having very strong buy in and having some sort of leadership on the ground … leadership is very core to ensuring that early literacy promotion is successful…”

Experts noted how caregivers look to clinicians for guidance, which creates an opportunity to identify shared reading as important for families. Experts emphasized that positive, strengths-based messages highlight the caregiver’s central role in their child’s development and boost confidence in their relationship. When using the term strengths-based experts included examples like positive messaging, meeting parents where they are, and highlighting the central role caregivers play in their children’s lives.

“And so that’s the kind of coaching that is strength-based, that meets parents where they are that helps create more harmony in the family and really gets to the point of like hey one of your jobs as a parent is to really figure out this child development thing.”

Experts highlighted modeling as a core component that sets age-appropriate expectations and gives caregivers the confidence to go home and read with their child through different developmental stages.

“But there’s a second piece, and that’s the skills piece. How am I supposed to read to my squirmy toddler? They won’t sit still, right? And that’s where helping model things like dialogic reading makes a difference”

Theme 3: Additional components that are adaptable to setting and context include literacy-rich clinical environments and referrals to other community resources

Experts also identified components that were adaptable to context including a literacy-rich clinical environment.

“Some of the emphasis on like a literacy-rich clinic environment isn’t necessarily as important …it’s nice to have like flyers in the waiting room or, you know, things on display about other local library resources… but I don’t think those are necessarily a place to put the most effort until some of those other core components are in place.”

Experts emphasized that clinicians must be mindful of context, which sometimes means addressing caregiver stress and other social drivers of health first by helping with access to community resources.

“Because it’s short-sighted to say ‘Hey go into a room, be jolly and talk about shared reading’ if you can’t understand the realities of what your families are facing …because nobody is at their best when they’re that stressed …”

Experts mentioned other examples related to community resources including library cards and community support groups, as well as reinforcing the literacy promotion message outside of clinical settings through social media messages and reminders (e.g., text messages).

This theme was similar across experts from U.S. and Canada.

Theme 4: Experts diverged on the extent to which providing a children’s book during literacy promotion is essential, but there was congruence that the book should be culturally tailored if provided and book provision is insufficient on its own.

A key difference between Canadian and many U.S. participants was their view on whether the provision of a children’s book is essential to literacy promotion. Many U.S. participants, but not all, identified the children’s book as essential to literacy promotion. Some noted the key role book provision plays in creating access, particularly for families from under-resourced communities, which is necessary to make shared reading possible.

“… and then the family is taking the book home with them as a reminder and they have it available to like then do exactly what you already talked about. So, it activates the process… to not have a book … it’s like one of many things we went home and talked about like brushing teeth without a toothbrush.”

U.S. participants also noted how diverse and culturally tailored books could empower children and families. Book provision can serve many purposes including promoting cultural identity and enriching the home literacy environment.

“It’s really important to have books that are representative of a diverse range of races, ethnicities, lived experiences, abilities, family structures, all of the different ways that people in places and families can be diverse. I think it’s really important to have books that represent that full spectrum of experience…”

Additionally, U.S. participants noted how children’s books could enrich the pediatric well-visit. They noted how books can be a tool for developmental monitoring, including assessment of caregiver-child interactions, and promoting the clinician-caregiver relationship by providing opportunities to connect with families.

“…you have an opportunity to watch what they do with [the book], right? A few seconds can tell you how are those child’s fine motor skills, gross motor skills, language, … social… interaction, et cetera. Do they walk over to their parent and hold it out in that ‘read to me’ gesture right.”

In contrast, Canadian participants and a few U.S. participants viewed the book as useful and important, but not essential. Canadian experts stressed the importance of a public health approach with messaging that encompasses shared reading as one activity among other literacy-promoting activities noting emphasis on encouraging caregivers to also speak, tell stories and sing with children.

“…talking about books is very good, but families need to know that storytelling and other language activities like singing and speaking are very important as well, and for some families in particular cultures, the storytelling is even more important than looking at the book.”

While there was divergence on the extent to which book provision was a core component, there was agreement that book provision alone is insufficient to have a meaningful impact.

“[Some parents] … don’t necessarily have an association, with books and pleasure. And so, they need through relationship … a new exposure. You know, a real relearning of what it can be. So, when it comes to book giving my answer is it depends … Because I think just having a whole bunch of books that come and sit on the shelf is a waste of money and I would rather see the money put into the delivering of training for how to be in relationship with families as you’re talking about early literacy…”

Experts identified funding, specifically funding for books, as an important barrier to literacy promotion. Experts also identified other barriers to implementing literacy promotion including limited clinician time, lack of incentives and reimbursement, and pressing social needs like food and housing insecurity.

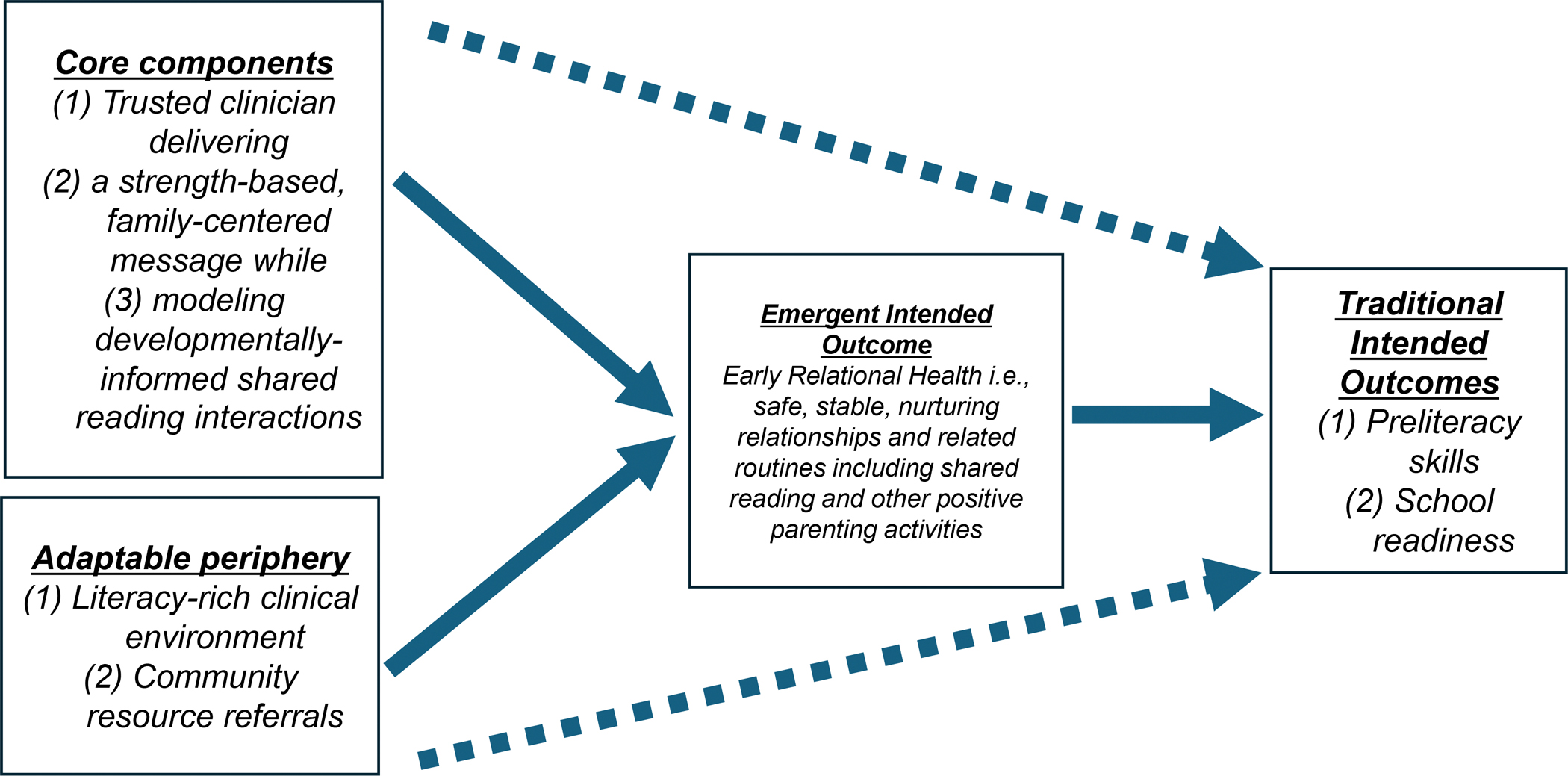

Figure 1 provides a parsimonious summary of intended outcomes, core components, and potential mechanisms derived from the study findings.

Figure 1:

Summary of intended outcomes, core components, and potential mechanisms

Discussion

Health care and policy experts from the U.S. and Canada provided insight into the intended outcomes and core components of primary care-based literacy promotion. First, participants identified ERH as a foundational goal that underlies the other effects of literacy promotion. Second, core components included strengths-based family-centered messages as part of anticipatory guidance and developmentally-informed modeling from a trusted clinician. Notably, while experts differed on whether book provision was essential to literacy promotion, they agreed that book provision alone is insufficient. These findings have implications for clinicians implementing literacy promotion in primary care and policymakers seeking strategies to maximize its impact.

Clarity on intended outcomes is essential to guide implementation of an intervention and conduct research on its effectiveness. Yet there are notable differences regarding the outcomes highlighted in early AAP guidance on literacy promotion and more recent policy statements, and the current study provides insight into this evolution. While early editions of Bright Futures described literacy promotion mainly supporting language development,28 both the 2014 policy statement on literacy promotion and the 2024 update placed an emphasis on safe, stable, and nurturing relationships.7,29 In this study, participants identified ERH as a foundational goal that underlies other effects on child development and school readiness. They also described how this focus on ERH crystallized over time. There are good reasons to hypothesize that literacy promotion can enhance ERH. Studies document how shared reading is associated with increased parental warmth and sensitivity, and less harsh parenting.4,30 Other work has demonstrated how PlayReadVIP, a pediatric-based preventive program designed as an enhancement to ROR, can support ERH through the promotion of parent-child play and reading.31 Traditionally, studies examining literacy promotion, more specifically ROR, have focused on home literacy environment and language development as primary outcomes,9–13 although research on other outcomes is emerging.14–17 Future research should include measures of ERH to better understand the role of literacy promotion in supporting it and what components may be most important. Additionally, given the important role of other sectors like early childhood education and childcare in promoting ERH and literacy, more work is needed to understand how to create synergies across healthcare and other sectors like education.

Clinicians identified strengths-based anticipatory guidance from a trusted clinician and developmentally-informed modeling as core components. ROR is notable for its strong evidence base and remarkable uptake at a national scale.32 However, recent work has identified variations that could dilute its impact.18,24 There is inherent tension between high-fidelity implementation, which minimizes variation, and flexibility that allows wide-scale uptake. Intentionally distinguishing the core components that drive clinical change from components that are recommended but adaptable can help relieve some of this tension.23 Experts and thought leaders offered insights into the components they see as driving clinical change as well as other components that can be adapted to context. For example, the literacy-rich waiting room, which the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted at many sites, was identified as an example. Some sites with a rich supply of volunteers (e.g., sites with nearby universities) may enlist readers in waiting rooms while other sites may choose other options. More empirical work that builds on the perspective of experts identified here is necessary to examine components, their mechanism of action, and guide which components are core and which are in the adaptable periphery.

The divergent perspectives on whether a children’s book is a core component of literacy promotion warrants additional inquiry. While the perspectives of experts from the U.S. and Canada were largely similar, the extent to which a children’s book is a core component was a notable exception. Some U.S. experts shared the view that the book may not always be necessary. In fact, the AAP policy statement on literacy promotion makes provisions for scenarios when no book is available.7 The emphasis of the CPS’s position statement on the importance of singing, talking, and storytelling in addition to reading is also worth noting.6Such an emphasis could be especially valuable for caregivers from cultures that prioritize storytelling or those with low literacy who may have had varying past experiences with reading.33,34 Consistent with prior studies,24 experts identified funding for children’s books as a common barrier to literacy promotion implementation. Our findings suggest that literacy promotion may still be possible even when children’s books are unavailable. Importantly, we found agreement among experts that giving a children’s book alone is insufficient, which corresponds with the available evidence.21,35

To our knowledge, this is the first study to purposively sample healthcare and policy experts across two countries to gain an in-depth perspective on the intended outcomes and core components of primary care-based literacy promotion. The international and interprofessional group of experts brought an impressive range of experiences and perspectives that offer unique insights. However, there are also limitations. We focused on interviewing healthcare and policy experts as a first step to understanding primary care-based literacy promotion as intended. While these perspectives are useful and important, they may differ from the perspectives of frontline clinicians, educators, other professionals, and caregivers which should be the focus of future work. Additionally, while the perspectives of experts on core components enhances our understanding and generates useful hypotheses, empirical work examining components and mechanisms of action is needed.

Conclusion

Primary care-based literacy promotion is an intervention that has capitalized on pediatric professionals’ near-universal access to children, reached millions of families, and built an impressive evidence base. An intentional focus on clarifying intended outcomes and distinguishing core versus adaptable components offers a path towards amplifying this impact and ensuring sustainability. This study provides expert insights as an early step toward achieving these goals.

Supplementary Material

What’s new:

Literacy promotion is a pediatric care standard, yet variation in implementation may dilute its impact. Experts identified intended outcomes as well as core and adaptable components that can inform literacy promotion training and healthcare improvement efforts to maximize its impact.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for their time and expertise, and Jennifer Hemler, PhD for her contributions to the interview guide.

Funding/support:

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number K24NR021198. Dr. Jimenez receives additional grant support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through its support of the Child Health Institute of New Jersey under grant number 74260. Dr. Dillon receives grant support from Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of award number T32HP49552. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINR, HRSA, or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Role of funder/sponsor:

The funder/sponsor did not participate in the work.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: Drs. Jimenez, Mendelsohn, and Ramachandran have disclosed an uncompensated relationship with Reach Out and Read as advisory board members. Dr. Ramachandran also discloses an uncompensated relationship as medical director of Reach Out and Read New Jersey. Dr Shearman is an employee of Reach Out and Read, Chief of Research and Innovation, responsible for overseeing the research strategy. The authors report no other conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, in the production of this manuscript. This manuscript or parts of this manuscript have not been published elsewhere.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Navsaria D, Sanders LM. Early literacy promotion in the digital age. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62(5):1273–1295. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26318952/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mol SE, Bus AG. To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(2):267–296. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21219054/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1037/a0021890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Farrelly C, Doyle O, Victory G, Palamaro-Munsell E. Shared reading in infancy and later development: Evidence from an early intervention. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2018;54:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jimenez ME, Mendelsohn AL, Lin Y, Shelton P, Reichman N. Early shared reading is associated with less harsh parenting. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2019;40(7):530–537. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31107765/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimenez ME, Reichman NE, Mitchell C, Schneper L, McLanahan S, Notterman DA. Shared reading at age 1 year and later vocabulary: A gene-environment study. J Pediatr. 2020;216:189–196.e3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6917887/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw A. Read, speak, sing: Promoting early literacy in the health care setting. Paediatr Child Health. 2021;26(3):182–196. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33936340/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxab005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klass P, Miller-Fitzwater A, High PC. Literacy promotion: An essential component of primary care pediatric practice: Policy statement. Pediatrics. 2024;154(6):e2024069090. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39342414/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1542/peds.2024-069090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reach out and read https://reachoutandread.org. Accessed March 1, 2024.

- 9.Mendelsohn AL, Mogilner LN, Dreyer BP, et al. The impact of a clinic-based literacy intervention on language development in inner-city preschool children. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):130–134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11134446/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.High P, Hopmann M, LaGasse L, Linn H. Evaluation of a clinic-based program to promote book sharing and bedtime routines among low-income urban families with young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(5):459–465. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9605029/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golova N, Alario AJ, Vivier PM, Rodriguez M, High PC. Literacy promotion for hispanic families in a primary care setting: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1999;103(5 Pt 1):993–997. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10224178/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Needlman R, Toker KH, Dreyer BP, Klass P, Mendelsohn AL. Effectiveness of a primary care intervention to support reading aloud: A multicenter evaluation. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(4):209–215. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16026185/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1367/A04-110R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Needlman R, Silverstein M. Pediatric interventions to support reading aloud: How good is the evidence? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25(5):352–363. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15502552/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200410000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar MM, Cowan HR, Erdman L, Kaufman M, Hick KM. Reach out and read is feasible and effective for adolescent mothers: A pilot study. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(3):630–638. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26520158/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1862-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Needlman RD, Dreyer BP, Klass P, Mendelsohn AL. Attendance at well-child visits after reach out and read. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019:9922818822975. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30614260/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1177/0009922818822975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunlap M, Lake L, Patterson S, Perdue B, Caldwell A. Reach out and read and developmental screening: Using federal dollars through a health services initiative. J Investig Med. 2021:jim–001629. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33441482/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1136/jim-2020-001629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burton H, Navsaria D. Evaluating the effect of reach out and read on clinic values, attitudes, and knowledge. WMJ. 2019;118(4):177–181. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31978286/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jimenez ME, Hemler JR, Uthirasamy N, et al. A mixed-methods investigation examining site-level variation in reach out and read implementation. Acad Pediatr. 2023;23(5):913–921. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36496152/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khandekar AA, Augustyn M, Sanders L, Zuckerman B. Improving early literacy promotion: A quality-improvement project for reach out and read. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):1067. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21402630/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King TM, Muzaffar S, George M. The role of clinic culture in implementation of primary care interventions: The case of reach out and read. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(1):40–46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19329090/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jimenez ME, Uthirasamy N, Hemler JR, et al. Maximizing the impact of reach out and read literacy promotion:Anticipatory guidance and modeling. Pediatr Res. 2024;95(6):1644–1648. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38062258/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1038/s41390-023-02945-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19664226/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edmunds SR, Frost KM, Sheldrick RC, et al. A method for defining the CORE of a psychosocial intervention to guide adaptation in practice: Reciprocal imitation teaching as a case example. Autism. 2022;26(3):601–614. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8934256/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1177/13623613211064431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uthirasamy N, Reddy M, Hemler JR, et al. Reach out and read implementation: A scoping review. Acad Pediatr. 2023;23(3):520–549. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36464156/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24979285/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dicicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ. 2006;40(4):314–321. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16573666/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. Third ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green M. Bright futures : Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents / morris green, editor.; 1994. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2887621692.

- 29.High PC, Klass P, Donoghue E, et al. Literacy promotion: An essential component of primary care pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):404–409. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24962987. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canfield CF, Miller EB, Shaw DS, Morris P, Alonso A, Mendelsohn A. Beyond language: Impacts of shared reading on parenting stress and early parent-child relational health. Dev Psychol. 2020;56(7):1305–1315. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7319866/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1037/dev0000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piccolo LR, Roby E, Canfield CF, et al. Supporting responsive parenting in real-world implementation: Minimal effective dose of the video interaction project. Pediatr Res. 2024;95(5):1295–1300. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38040989/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1038/s41390-023-02916-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuckerman B, Augustyn M. Books and reading: Evidence-based standard of care whose time has come. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(1):11–17. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21272819/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jimenez ME, Crabtree BF, Veras J, et al. Latino parents’ experiences with literacy promotion in primary care: Facilitators and barriers. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(8):1177–1183. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32795690/. Accessed Jul 21, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avelar D, Weisleder A, Golinkoff RM. Hispanic parents’ beliefs and practices during shared reading in english and spanish. Early Education and Development. 2025;36(2):364–385. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2024.2389368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Bondt M, Willenberg IA, Bus AG. Do book giveaway programs promote the home literacy environment and children’s literacy-related behavior and skills? Review of Educational Research. 2020;90(3):349–375. doi: 10.3102/0034654320922140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.