Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a significant threat to human health. The widespread prevalence of AMR is largely due to the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes (ARG), typically mediated by plasmids. Many of the plasmid-mediated resistance genes in pathogens originate from environmental, animal, or human habitats. Despite evidence that plasmids mobilize ARG between these, we have a limited understanding of where ARG emerge and how their ecology and evolutionary trajectories result in them appearing in clinical pathogens. One Health, a holistic framework, enables the exploration of these knowledge gaps. With this in mind, we first provide an overview of how plasmids drive local and global AMR spread and link different habitats. Then we review some of the emerging studies integrating an eco-evolutionary perspective, opening a discussion on factors that affect the ecology and evolution of plasmids in complex microbial communities. Specifically, we discuss how the emergence and persistence of multi-drug resistance (MDR) plasmids can be affected by varying selective conditions, spatial structure, environmental heterogeneity, temporal variation, and coexistence with other members of the microbiome. These factors, along with others yet to be investigated, collectively determine the emergence and transfer of plasmid-mediated AMR within and between habitats at the local and global scale.

Keywords: Antibiotic Resistance, Antimicrobial Resistance, One Health, Horizontal Gene Transfer, Ecology, Evolution

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in bacterial pathogens is a growing pandemic that threatens to render current treatments for microbial infections ineffective. In 2019 an estimated 1.27 million people died worldwide from infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria1. The increased prevalence of these resistant pathogens has led to the recognition of this threat by major political, economic, and public health institutions (WHO/UN, World Bank, CDC, ECDC, etc.)2–4. Beyond the significant burden that AMR infections cause for healthcare, their prevalence has also affected other areas of global importance, such as economic development5. It is thus clear that the AMR pandemic has been, and will continue to be, a significant challenge beyond its impacts on human health.

New obstacles for facing AMR have been raised by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the major shifts it has caused in our healthcare landscape, it has also been accompanied by an increase in reported drug-resistant pathogens in Europe from 2020 to 20213,6. Importantly, the COVID-19 pandemic has also cast a spotlight on the importance of the interconnection between humans, animals, and the shared environment on human health. Indeed, both AMR and COVID-19 are global health threats that have their origin beyond human habitats. Several antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) found in today’s pathogens originated from animal or environmental bacteria7,8. Seminal work published in the 70’s and research over the past decades supports the notion that some animals and environmental habitats are important reservoirs of ARGs9–14, which may indeed cross ecological boundaries15,16. Therefore, it has been advocated that research, surveillance, and intervention strategies require a comprehensive approach recognizing the interconnectedness of human health with that of animals and our shared environments.

One Health, first coined in the scientific literature roughly 10 years ago, has now become a broadly accepted term to describe such a holistic approach17. There is no standard definition of One Health, and the meaning can vary depending on who is using it18. Here, we place the term One Health within the scope of the One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) where it is defined as an approach that “recognizes the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent. The approach mobilizes multiple sectors, disciplines, and communities at varying levels of society to work together to foster well-being and tackle threats to health and ecosystems”19. Importantly, a One Health approach will allow a greater understanding of the trajectories by which ARGs from different habitats rapidly make their way to human pathogens. More broadly, such a holistic perspective is critical for public health, considering amplified interactions between humans, animals, and the environment. These interactions are exacerbated by changes in climate, land use, and demographics, providing more and more opportunities for the emergence of infectious diseases and pathogens resistant to antibiotics20.

The emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is due in large part to the spread of ARG via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Fig. 1). This gene exchange is primarily mediated by plasmids, extrachromosomal genetic elements that can transfer between bacteria via conjugation, often across taxonomic boundaries (Box 1)21. Over the last 20 years, plasmid-mediated resistance has compromised the clinical utility of widely used drugs against Gram-negative bacteria. For example, plasmids are critical players in disseminating resistance to penicillins, quinolones, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, carbapenems, and last-resort antibiotics such as colistin22,23. In addition, plasmids have contributed significantly to the spread of pandemic multi-drug resistant high-risk clones such as Escherichia coli sequence type (ST) 131 and Klebsiella pneumoniae ST25824,25. Although no epidemiological studies have quantified the burden of plasmid-mediated resistance on healthcare systems, one survey found that infections caused by pathogens carrying a plasmid are associated with longer patient hospitalization and comorbidity than their plasmid-free counterparts26. These results have not been peer-reviewed but highlight the need for quantitative studies assessing the burden of plasmid-mediated resistance on healthcare systems. Such studies are needed as plasmids continuously contribute to the rising number of antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Based on recent findings, this may be even more important among urban and industrialized populations, where an increase in HGT within individual gut microbiomes was observed compared to rural non-industrialized lifestyles27.

FIG. 1: Mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

Transformation (top left), transduction (top middle), conjugation (top right), nanotubes (bottom left), gene transfer agents (bottom middle), and membrane vesicles (bottom right). Transformation, transduction, and conjugation are the most well recognized in spread of AMR. Gene transfer agents, nanotubes, and membrane vesicles are other less recognized mechanisms of HGT whose role in spread of AMR remains largely unexplored.

Box 1: AMR transmission by Conjugation.

The machinery needed for conjugation can be encoded by plasmids or by integrative conjugative elements (ICE), and serves to ensure that DNA is properly mobilized from a donor to a recipient bacterium145. In addition to transferring themselves, conjugative plasmids (and ICE) can also facilitate the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) on other mobile genetic elements, thereby serving as vehicles for the spread of these genes between diverse bacteria146. Some conjugative plasmids also have the capacity to mobilize plasmids, and even genes from bacterial chromosomes, genes, from the recipient cell back to the plasmid donor. This process, called retromobilization, brings a new perspective on the ecological role of conjugative plasmids, as they could allow a plasmid carrier to access the pool of ARG in a microbial community147.

Ranging in size from a least one to several thousand kilobases, plasmids are highly diverse genetic elements. Depending on whether they encode their own, or are able to use existing conjugative machinery, plasmids are broadly categorized as conjugative, mobilizable, or non-mobilizable148,149. Genes needed for conjugation form part of the plasmid ‘backbone’, along with other genes involved in stable maintenance, regulatory control, and replication of the plasmid. Plasmids additionally often have one or more ‘accessory’ regions. These plasmid regions contain genes encoding a range of functions that promote their own survival, such as toxin-antitoxin genes, or their host’s survival, such as metal and antibiotic resistance genes, virulence genes, and genes encoding metabolic and catabolic functions150. These ‘accessory’ regions can be highly variable between plasmids, in large part due to the frequent recombination events mediated by transposons, insertion sequences and integron gene cassettes151. This results in the creation of mosaic plasmids, plasmids composed of genetic elements from distinct sources151. Mosaic plasmids have significantly higher proportions of transposase and ARG and tend to be more common among clinically relevant genera such as Escherichia, Klebsiella, or Salmonella151.

In this review, we use the One Health framework to synthesize the recent literature on the ecological and evolutionary factors that determine the successful local and global spread of plasmid-mediated ARG. We first focus on how plasmids act as a cornerstone in the spread of ARG within and between habitats. We do this by providing an overview of the distribution of plasmid-borne ARG in different habitats, and detailing cases of carbapenem and colistin resistance spread that show how plasmids facilitate ARG mobilization between habitats. Subsequently, we discuss some of the eco-evolutionary factors driving the emergence, long-term persistence, and spread of plasmids in natural communities. Specifically, we discuss how the fate of plasmids is influenced by selective conditions, spatial structure, environmental heterogeneity, temporal variation, and community context.

2. Plasmids Mediate ARG Spread

2.1. ARG spread across different habitats

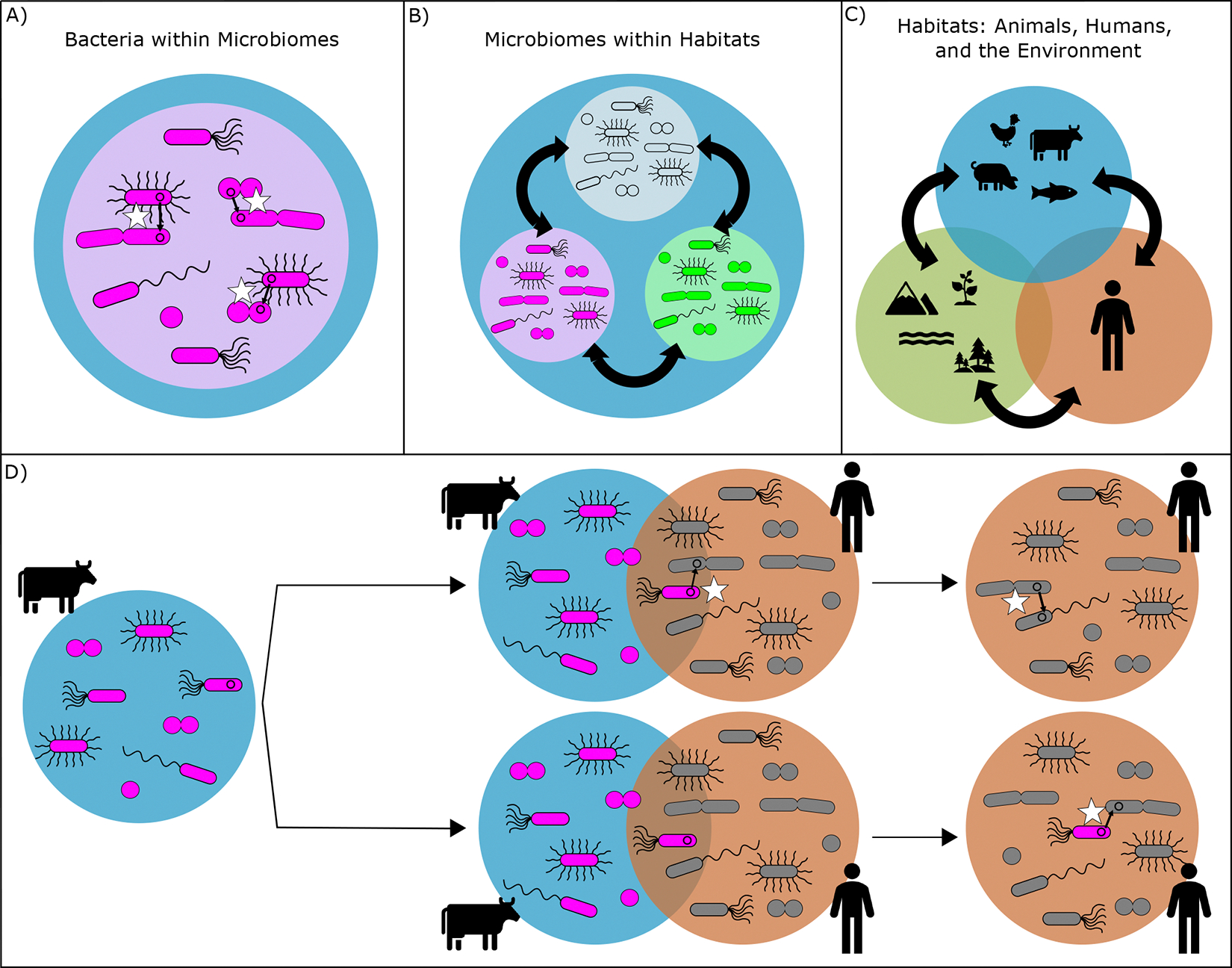

Plasmids are central in ARG spread within the One Health framework. Opportunities for the plasmid-mediated spread of ARG occur at three biological levels: (1) between bacteria within microbiomes, (2) between microbiomes within habitats, and (3) between animals, humans, and the environment (Fig. 2)17.

FIG. 2: Antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) spread under a One Health Framework.

Different biological levels at which ARG spread occurs (A-C). Plasmids do not only play an important role in the spread of ARG between bacteria within a microbiome (white stars in A), and between microbiomes within a habitat (black arrows in B), but they are also pivotal for spreading ARG between habitats (C). A hypothetical pathway of a resistance plasmid from a cow to a human is depicted under (D). The spread of a plasmid can occur at areas of confluence, where microbiomes between two environments overlap. An example of such an area of confluence in farm settings arises when workers interact with cows. In this interaction, a plasmid can spread directly between animal and human bacteria (top pathway), or bacteria from the cow microbiome can survive long enough in the human microbiome to subsequently spread their plasmid (bottom pathway).

Within and between microbiomes, plasmids function as vehicles that shuttle ARG between bacteria, including distantly related species28,29 (Fig. 2A, B). In this role, plasmids are at the center of ARG exchanges between cells, whereas insertion sequences (IS), transposable (Tn) elements, and integrons promote intracellular gene exchange30. A recent study reported that ISs were associated with more than 77% of ARG types and that 63% of recent ARG transfer events between plasmids and bacterial chromosomes were facilitated by ISs31. ISs and Tn elements thus facilitate ARG acquisition by plasmids, which in turn shuttle the genes between members in a microbiome. The result is an ongoing shuffling of genes within microbial communities.

Plasmids are also important for facilitating the spread of ARG across habitats (Fig. 2C, D). In this role, plasmids able to replicate in a broad range of hosts can drive gene exchange over large phylogenetic distances. While broad-host-range (BHR) plasmids probably play a critical ecological role in some habitats32, it is of concern that IncP-1 and other BHR plasmids associated with ARG have been frequently isolated from habitats such as produce33, soils34, manure35, wastewater36–38, or river39. The transfer of these plasmids between habitats can occur at areas of confluence, the interfaces where two habitats overlap. Examples of areas of confluence are sewer systems or wastewater treatment plants (WWTP), where environmental bacteria are mixed with bacteria from humans. Similarly, fertilizing agricultural soil with manure results in the mixing of bacteria of animal origin with environmental bacteria. However, plasmid spread alone cannot be explained solely by their transfer in areas of confluence. The hosts of plasmids, especially hosts belonging to so-called generalist taxa able to persist or thrive in multiple habitats40,41, may play also a critical role in transferring multi-drug resistance (MDR) plasmids between habitats. Indeed as recently found, some of those generalist bacteria tend to carry more ARG and plasmids than others in a natural bacterial community42–44. A recent example includes Aeromonas sp. in WWTP, which were identified as host reservoirs of MDR plasmids42. Strains from the same genus were also found to be good natural recipients of an MDR plasmid when exposed to a donor bacterium in an activated sludge system45. These discoveries have shed light on the importance of successful associations between plasmids and their host in facilitating ARG spread between habitats.

We illustrate the crucial role played by plasmids in ARG dissemination across habitats by mapping the distribution of the ARG carried by plasmids across human, animal, or environmental samples (Fig. 3, Supplementary Methods)46. Despite the bias of database mining, such as the over-representation of clinical bacterial isolates, this overview shows that about half of the plasmid-encoded ARGs in the database were present on plasmids isolated from more than one habitat (Fig. 3B). For example, clinically relevant ARG such as kpc-1 or mcr-1 were found on plasmids across human, animal, and environmental habitats (Fig. 3C). This strongly suggests that plasmids move ARG between animal, environmental and human habitats, and bolsters the need for a One Health holistic approach.

FIG. 3: Meta-analysis on plasmids in PLSDB database.

Plasmids were classified according to the source of isolation, i.e. the habitat they were found in: Animal, Environment, or Human. A) Breakdown of habitats that plasmids with and without ARG were classified into. B) Breakdown of the number of plasmid borne antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) that were detected solely in one habitat, or in each combination of habitats. For example, there were ~ 120 ARG that were found only on plasmids in samples of Human origin. The second highest category was of ARG that were found on plasmids in all three habitats (Animal, Environment, and Human). C) Detection of a subset of ARG conferring resistance to clinically important antibiotics in the three habitats. For each gene, the percentage of plasmids within each habitat that carry that gene is shown. The bars at the bottom depict the number of habitats in which at least one plasmid carried that gene; Red = All three habitats, Black = two out of three, White= only one. Methods about this meta-analysis are detailed in the supplementary material.

The implementation of holistic approaches has already resulted in well-studied examples of plasmid-mediated mobilization of ARG from environmental and animal reservoirs to humans. This is the case for the global spread of colistin resistance as well as the spread of carbapenem resistance in clinical settings, both involving antibiotics of paramount importance for human health.

2.2. Global spread of colistin

The global spread of colistin resistance is a paradigm for the role of plasmids in mobilizing resistance genes between animal and human habitats. Colistin is an antibiotic of last resort for infections caused by multi-drug resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria47. A combination of the increased occurrence of MDR Gram-negative bacterial infections and the limited development of novel antibiotics has contributed to the increased importance of colistin for clinical use.

The first plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, was identified in late 20157. Initially detected in E. coli isolates from food animals, subsequent screening revealed that mcr-1 was also present in isolates from raw meat and hospital patients, although to a lesser degree7. The higher prevalence of colistin resistance amongst animal isolates raised the hypothesis that it may have originated in animals and subsequently spread to humans. This was confirmed by a phylogenetic analysis carried out on a global dataset of 457 mcr-1-positive isolates25. The study supports the notion that mcr-1 was initially mobilized by the composite transposon ISApl1, followed by loss of the insertion sequence and subsequent stabilization of mcr-1 on multiple distinct plasmids25,48. This study further revealed that mcr-1 was present across 31 countries across 5 continents and 13 different plasmid backgrounds, with a likely origin from agricultural settings in China in the mid-2000s. Collectively, these studies show how plasmids have played a central role in the now widespread prevalence of colistin resistance.

2.3. Carbapenem resistance spread in clinics

Wide-spread resistance to carbapenems among Gram-negative bacteria is another serious global public health concern driven by plasmids. Carbapenems were long considered as the most reliable last-resort treatment of infections by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria49. Unfortunately, carbapenemases genes (which confer bacterial resistance to carbapenems) have spread worldwide and have drastically limited treatment options. The emergence of carbapenem resistance is not recent, but the alarming rate at which carbapenemase genes are spreading globally is of extreme concern. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases, for example, were first discovered in the US in 1996 and are now endemic in many regions of the world, including the US, Brazil, Argentina, and China50–52. In the US, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter and Enterobacteriaceae have been recognized as urgent threats by the CDC, having respectively caused an estimated 8,500 and 13,100 cases amongst hospitalized patients in 20172. In the European Union, carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae have been linked to an increase in attributable deaths by a factor of 3.3, 4.8, and 6.2, respectively, from 2007 to 201553. The spread of carbapenem resistance worldwide has been and will continue to be, a major concern for human health.

While the original habitat(s) from which carbapenemase resistance genes emerged is not as clear as it is for colistin resistance, many studies have investigated how carbapenem resistance spreads during local outbreaks. These outbreaks are largely driven by a few plasmid-mediated carbapenemase variants such as New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) or the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), one of the most widespread carbapenem resistance genes 50,54,55. Studies show that KPC transmission during a clinical outbreak can be a dynamic process that is not only driven by the spread of bacterial clones but also by horizontal gene transfer via conjugative plasmids and transposons56–58.

Some hospitals have been investigating transmission routes underlying carbapenemase resistance gene transmission. In one of them, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) isolates have been studied since the initial identification of blaKPC-positive Klebsiella pneumonia and Klebsiella oxytoca harboring blaKPC plasmids in 200759,60. The isolate collection at this institution also includes Klebsiella quasipneumoniae strains that were later collected from hospital sink drains. KPC genes were found to be present in “nested doll-like structures”, within a Tn4401 transposon that is nested within a Tn2-like element61. Sampling of the hospital environment revealed that K. quasipneumoniae was persisting both in humans and in the hospital environment over the course of the outbreak. Throughout this time, K. quasipneumoniae demonstrated a high propensity for the acquisition of blaKPC-containing plasmids, including from different bacterial species in the hospital environment62. By including hospital environmental samples in their study, the researchers gained important insight into the spread of carbapenem-resistant pathogens between patients and the environment.

Another hospital has also carried out sampling of a hospital environment, to identify KPC routes of transmission63. Following an initial outbreak of blaKPC-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae in 2011, patient and hospital environment samples were collected between 2012 and 2016. Despite the low prevalence of blaKPC-positive infections, multiple carbapenemase-producing organism (CPO) reservoirs had been created. CPOs in the hospital sink drains were able to persist and recombine via HGT, creating a reservoir of CPOs carrying multiple resistance plasmids. Importantly, the study showed evidence of transmission from the hospital environment to patients. The transmission was of a Leclercia sp. strain with blaKPC encoded on a conjugative plasmid. This is another case highlighting the importance of the hospital environment as a reservoir where plasmid-mediated resistance can evolve and transfer between habitats.

Our understanding of colistin and carbapenem resistance epidemiology at the local and global scale advanced in part by applying the One Health framework through the integration of animal and environmental habitats with clinical research. Through this work, we learned that 1) to address AMR emergence and spread more efforts should be made to identify environmental strains that carry clinically relevant ARGs on plasmids, both inside and outside of hospitals, and 2) that plasmids act as cornerstones for the emergence and spread of AMR. Furthermore, to predict where ARGs emerge and their subsequent trajectories, we must understand the mechanisms that drive plasmid distribution, abundance, and evolution. Ultimately this knowledge will aid the development of future sustainable strategies to limit the emergence and spread of AMR.

3. Eco-evolutionary Plasmid Trajectories

3.1. MDR plasmid maintenance

As established back in the seventies by Stewart and Levin64, there are a set of basic molecular mechanisms that allow MDR plasmids to be maintained in a bacterial population. They allow plasmids to (i) properly replicate and segregate into daughter cells to minimize the formation of plasmid-free cells, (ii) infect newly formed plasmid-free cells by conjugation to counteract plasmid loss, and (iii) alleviate plasmid-imposed fitness costs on their bacterial hosts through compensatory mutations. A combination of these parameters determines whether a plasmid will be maintained in a bacterial population64. For example, plasmid loss via improper segregation or plasmid-imposed fitness costs can be offset by a high rate of plasmid transfer, allowing for its persistence without positive selection for a plasmid-encoded trait65. In contrast, a plasmid can be lost from a population if plasmid-free cells are formed at a higher rate than plasmid-containing cells. This can occur when the segregational loss rate or plasmid fitness cost are too high to be compensated by plasmid reinfection. Other factors, however, can also affect plasmid maintenance, such as the presence of a co-residing plasmid that can improve or worsen the persistence of a focal plasmid by affecting its segregational loss, transfer, or cost parameters66–68.

Importantly, all these key mechanisms underlying plasmid persistence can rapidly evolve through single mutations, making evolution a central factor in the fate of plasmids. Genomic mutations on the plasmid, its host, or both, can result in improved plasmid segregation, infectious transfer, or amelioration of fitness cost. Additional details on the molecular mechanisms of how bacteria and plasmids co-evolve are thoroughly reviewed by Brockhurst & Harrison or McLean & San Millan69,70. Theoretically, the right combination of these factors can ensure the persistence of MDR plasmids. However, bacterial populations evolve in complex environments, most often within a diverse microbial community and under various environmental conditions. Under such conditions, multiple layers of factors are predicted to interfere with the emergence, maintenance, and transfer of MDR plasmids, which we discuss below.

3.2. Factors determining plasmid fate

To predict where plasmids can invade new bacterial strains, species, or habitats we more than ever need to determine the habitats in which MDR plasmids are found and the main mechanisms that drive their emergence, long-term persistence, and spread within and between habitats. Some of those habitats and environmental factors such as pH, temperature, nutrients or soil type, etc. are known to influence the ecology of plasmids, in particular, their transfer, and are therefore not discussed here71–74. As we describe below, the long-term maintenance and spread of MDR plasmids is the result of the interaction between the plasmid, host, and environment (i.e., GxGxE). Thus, in most habitats, plasmid ecology and evolution are probably driven by a combination of factors across different biological scales, which we detail in Fig. 4. The One Health approach provides the holistic framework to address these questions by integrating theories and approaches from multiple disciplines. With this perspective in mind, we discuss recent studies focused on plasmid persistence, loss, or transfer in natural settings. We focus in particular on how plasmid ecology and evolution are influenced by varying levels of selection, spatial structure and environmental heterogeneity, temporal variations, and interaction with other members of the microbiome.

FIG. 4: In natural communities, plasmid fate is determined by multiple compounding factors at multiple biological scales.

Each box shows a biological scale in which different factors can affect plasmid ecology and evolution in natural settings. Text within each box provides a non-exhaustive list of those factors.

3.2.1. Various levels of selection

While strains that acquire a new clinically relevant ARG or mutation may arise at extremely low frequencies, they are not uncommon due to the extremely large bacterial population sizes on our planet75. A great example of this is the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 which has now spread globally due to a combination of selection and successful associations with plasmids and IS elements (described above). The right recombination of events creating successful MGE/ ARG associations was probably rare but occurred among trillions of bacteria anywhere on the planet, and the constant selection on these rare strains in some environments undoubtedly led to the emergence of new resistant strains with mobile ARG.

Selection for MDR plasmids can be direct or indirect. Direct selection happens when the plasmid encodes the resistance to the antibiotic present. Indirect selection occurs when the benefit is caused by another gene on the plasmid. Such co-selection, or indirect selection, of MDR plasmids has been described in the context of selection by metals or biocides. Their corresponding resistance genes have been found to often co-localize on plasmids with AMR genes76,77. In environments where bacteria are in contact with multiple compounds, the occurrence of these diverse selective conditions thus becomes highly relevant.

Selection for AMR is often perceived as the presence of an antibiotic inhibiting or killing sensitive cells, allowing only resistant cells to live. However, the concentrations in most environments are often too low to have such an effect. High concentrations above what is defined as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) are likely experienced only in human and animal microbiomes during periods of antibiotic treatment78 or in some environments, such as hospital wastewater or wastewater from pharmaceutical factories79. Outside of these few cases, antibiotic concentrations are usually not high enough to inhibit or kill sensitive cells80. Nevertheless, these antibiotic concentrations, defined as sub-inhibitory or sub-lethal, are still sufficient to provide a fitness advantage to plasmid-bearing cells81,82. The seminal work by Gullberg et. al found that the minimal concentration of antibiotics or metals necessary to select for the maintenance of a large 220-kb MDR plasmid in a bacterial population could be up to 140-fold lower than the MIC83. This study, and others conducted outside the context of plasmid-mediated resistance, have suggested that low concentrations of antibiotics present in the environment can be above the minimal selective concentration for ARG84–87. Thus plasmid-mediated resistance may be selected for in any place where relatively low antibiotic concentrations, or low levels of pollution by co-selecting agents, are found (e.g., WWTP, rivers receiving discharge from WWTP, or agricultural soil). As most studies done on the evolution of plasmids and their ARG are focused on simple models using high antibiotic concentrations above the MIC, it remains to be seen if sub-MIC can also affect the emergence and evolution of plasmid-mediated resistance. The rapid improvement of plasmid persistence even in the absence of selection88,89 suggests it can, thus creating potential new host reservoirs in various environments.

Selection for AMR not only results in the emergence of ARG but can also affect their acquisition on plasmids. It was recently shown that encoding an ARG on a plasmid, as opposed to the bacterial chromosome, conferred a selective advantage due to higher gene dosage90. Thus, under selection, ARG carriage was favored on plasmids as opposed to chromosomes, allowing for further spread to other bacteria90. While the mechanisms that determine whether an ARG ends up on a plasmid or a chromosome are complex and still not fully understood91, it is important to emphasize that the flexible gene dosage provided by plasmids may be an important driver of the evolution of AMR and other traits encoded by plasmids92.

In addition to selecting resistant cells after HGT or mutation, sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics have also been suggested to increase HGT itself by affecting the conjugation and transformation processes93,94. However, in many of these studies, the experimental design could not distinguish between the effects of the antimicrobial on conjugation and transformation rates and its subsequent effect on selection dynamics, making conclusions on the effect of sub-MIC on plasmid transfer controversial95,96. Even so, an increasing number of papers have explored the effects of other compounds on plasmid transfer. Amongst these are lead, metal nanoparticles, nonnutritive sweeteners, and other metal stressors97–102. These compounds were found to have varied effects, with some promoting, and others inhibiting, plasmid spread. However, some of these studies also suffer from our limited ability to truly measure the effect of a compound on the rate of plasmid transfer. Newer methods to measure conjugation rate open new avenues to determine which molecules can indeed enhance the rate by which plasmids transfer between cells103,104. The range of effects observed by recent studies emphasizes the need to explore how environmental pollutants can influence plasmid persistence and spread. These represent promising avenues for targeted approaches that could limit ARG-associated plasmid transfer105.

3.2.2. Spatial structure and heterogeneity

Most bacterial cells on our planet exist in spatially structured and heterogeneous environments such as biofilms, microbial aggregates (e.g., WWTP-activated sludge flocs), soils, etc. As opposed to well-mixed laboratory conditions, bacteria in structured environments interact more with their neighbors than with other bacteria further away. As a result, not all individuals in a population are in direct competition with each other. By impeding global competition between cells, spatially structured environments protract selective sweeps of beneficial mutations and slow down the rate of adaptation106–108.

Differences within and between habitats caused by spatial heterogeneity can also interfere with ARG emergence and spread. At the macroscopic scale, interference can occur due to factors such as climate (e.g., temperature, humidity) or anthropogenic activities109–111. At the microscopic scale, bacteria often experience gradients of metabolic substrates, electron acceptors, or even selective agents such as antimicrobials. For example, one study found that antibiotic concentrations were heterogeneous across activated sludge flocs and higher in the microbial aggregates than in the surrounding solution112. Spatial heterogeneity results in local adaptation, allowing bacteria from the same population to explore different adaptive trajectories. Such niche adaptation can, in turn, have pleiotropic effects on the evolution of plasmid persistence where the adaption to a new environment indirectly impacts plasmid persistence113,114. Together, spatial structure and heterogeneity promote the coexistence of genetically distinct individuals, which would not coexist in a well-mixed environment, and results in the maintenance of genetic diversity, allowing the populations to harbor multiple distinct evolutionary outcomes115–118.

Bacterial biofilms are notable examples of spatially structured populations creating environmental heterogeneity. They represent the main mode of bacterial growth on our planet75 and are the main cause of microbial infections119,120. Because of their important role in human, animal, and environmental health, as well as industrial processes121,122, they have been used as model systems to investigate the persistence and evolution of MDR plasmids. Recent studies comparing the evolution of plasmid-host pairs in biofilms and well-mixed cultures, for example, have found that biofilms resulted in the retention of a higher diversity of phenotypes and genotypes in the populations114,123. Importantly, variants with an improved ability to retain plasmids in the absence of selection were more common in biofilm populations114. Such unique evolutionary trajectories of plasmids in biofilms also led to the retention of costly conjugation systems otherwise removed when the same strain was evolved in a well-mixed pure culture124. These seminal studies emphasize that if we want to accurately predict the habitats where MDR plasmids persist and spread, we must study plasmid ecology and evolution in realistic and complex ecosystems.

In addition to affecting evolutionary trajectories, biofilms can also act as refugia for MDR plasmids124–126. This is due to their stratified composition, whereby both chemical and microbial gradients are established by metabolism and diffusion127,128. As a result, deeper layers farther away from the nutrient source mostly consist of non- or slowly dividing cells129. These layers can contain a record of the evolutionary history of the population where even costly or maladapted plasmid hosts, lost in upper layers of dividing cells, could be kept. This means that even when the MDR plasmid is lost in most of the population, it may still be present in these ‘dormant’ cells, remaining available for a future ‘rescue’ of the population if a selection event were to occur. This potential role of biofilms as archives for plasmid hosts is especially relevant as bacterial communities undergo temporal fluctuations124,126.

3.2.3. Temporal Variations

In natural environments, bacteria constantly experience diverse temporal changes. Examples include the variable concentration of antibiotics during the course of antibiotic treatment or the seasonality of pollution from anthropogenic activities130–132. Due to these temporal changes, bacteria undergo fluctuating selection that can influence long-term plasmid persistence.

Studies testing pulses of selection in monoculture have suggested that short-term selection was sufficient to change the population structure and favor the sweep of individuals with compensatory mutation able to better retain the plasmid in absence of selection133,134. Depending on the rate at which compensatory mutations occur, rare events of selection can be sufficient to maintain a plasmid in its population134. Importantly the authors highlighted how few pulses of selection could be sufficient to see the emergence of hosts able to better retain MDR plasmids in the absence of selection. Thus, these studies showed that even short periods of selection, which would be more representative of the selection dynamic bacteria experience in their environment, can have a long-term positive effect on plasmid persistence.

3.2.4. Community context

The role that members of a microbial community play in plasmid persistence is substantial, but still poorly understood. Depending on the context, they can either promote the spread of a given plasmid or drive it to extinction135. Regardless of the type of effect the community context may elicit, it is essential to note that plasmid persistence in a monoculture cannot be necessarily translated to that in bacterial communities.

Interestingly, some recent studies have demonstrated the double edge sword effects that community composition could have on plasmid persistence. In a study using a simple bacterial community embedded in sterile soil, plasmid maintenance in a focal strain was reduced in the presence of other bacterial species136. This was attributed to a dilution effect, where other community members impede the reinfection of the plasmid into the focal host. In contrast, another study predicted that overall plasmid persistence increased with increasing community diversity. This was based on a model using empirical plasmid cost data across a range of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from the human gut137. The underlying mechanism was attributed to the idea that the higher the host diversity, the higher the probability that one or more strains will be a favorable host for a particular plasmid, thus improving its persistence. Similar variations of plasmid effects on the growth of phylotypes were inferred in a complex community derived from a sewage treatment plant45. The observed differences in the effects a microbial community can have on the fate of a plasmid suggests that more research is needed to understand how microbial interactions determine the persistence and spread of MDR plasmids. Some of these factors have recently been reviewed in depth and are therefore only briefly described here138.

Beyond affecting plasmid spread, the community context can also be pivotal for maintaining access to MDR plasmids. For example, the presence of proficient hosts able to maintain and transfer a plasmid can result in source-sink dynamics that allow for maintenance of the plasmid in less proficient hosts139. Among other examples, recent studies on plasmid transfer in complex communities have highlighted the importance of the rare microbiome as a source of MDR plasmids33,140. These strains may escape cultivation-independent or metagenomic detection yet can facilitate plasmid transfer to human pathogens or commensals. In a zebrafish model, a plasmid-carrying donor was introduced via food. The bacterial species to which the plasmid transferred was present at a relative abundance of less than 0.01% of the gut community140. In a second study, exogenously captured plasmids from produce microbiomes were undetectable via molecular assays33. Host reservoirs of MDR plasmids present at very low frequencies in communities may thus play an important role in the persistence and spread of MDR plasmids.

Cultivation-based approaches or exogenous plasmid capture can access some of these rare plasmids, but at the cost of losing diversity. Indeed most bacterial cells remain non-culturable with the classical culture media, and not all plasmids can be isolated by exogenous capture of their hosts. New metagenomic approaches recently developed can circumvent this bottleneck (Box 2). However, these approaches cannot detect potential key players that are in low abundance in a community without relying on a priori information (e.g., reference genomes). Combinations of multiple approaches may be a solution to studying plasmids in complex communities. Other methods still in development including a target capture approach for identifying hosts of particular plasmids in microbiomes will be instrumental in the continued investigation of plasmid spread in natural habitats141. These methods may be able to bypass current limitations and allow us to gain greater insight into the effect of the microbial community on plasmid spread.

Box 2: Development in methods to identify plasmid hosts in microbiomes.

In recent years, several novel approaches have enriched our toolbox for identifying the hosts of multi-drug resistance (MDR) plasmids152. Those approaches represent promising avenues for exploring the ecology and evolution of these and other plasmids in natural microbial communities.

Proximity ligation methods (e.g., Hi-C and meta3C) crosslink DNA in proximity within a cell in vivo. These physical links remain after cell lyses and result in the creation of chimeric fragments that are derived from DNA that was adjacent within the cell. By sequencing these chimeric fragments of DNA, researchers can identify bacterial hosts of antibiotic resistance genes (ARG), plasmids, and other mobile genetic elements (MGE). It has been successfully used to reconstruct the reservoirs of ARG in wastewater as well as in human and pig guts42,153–155.

DNA methylation approaches associate plasmids to their hosts’ chromosome through DNA methylation signatures. Metagenomic DNA undergoes shotgun SMRT (single-molecule, real-time) sequencing where methylation can be detected. The assembled contigs are then binned based on methylation profiles and composition features, improving genome reconstruction and enabling to match plasmids with their hosts in complex samples156.

Fusion PCR approaches (e.g., EpicPCR or OIL-PCR157) detect plasmid-host associations by linking known genes of interest to a 16S ribosomal RNA gene. This is accomplished by designing primers that amplify a target gene and have an overhang of 16S rRNA gene homology. The amplicons are fused, resulting in fragments that contain both the target gene and partial 16S rRNA gene. When sequenced, this fused product can be used to identify the host that carried the gene of interest. This protocol has been utilized to determine the host range of ARG in wastewater and water microbial communities 44,158,159.

It should be noted that for sequencing-based metagenomic approaches, the complexity of microbial communities makes the reconstruction of host and plasmid genomes complex. Thus, these still bear a certain level of uncertainty that the characterization of isolates does not have. Nevertheless, these approaches could help elucidate plasmid eco-evolutionary dynamics in natural settings.

4. Concluding Remarks

It is now well-recognized that the spread of AMR is an issue that goes beyond human and animal healthcare settings. In that regard, the integration of the One Health framework by the research community tackling the environmental dimensions of AMR has led to important findings. Examples include identification of settings where AMR is more prevalent, anthropogenic impacts enriching for AMR, and strategies for AMR surveillance.12,142,143. Unfortunately, challenges underlying the study of HGT, and particularly plasmids, in natural microbial communities have left us with major gaps in our understanding of the emergence and spread of AMR in today’s pathogens144.

As described throughout the review, plasmids are a cornerstone in the dissemination of AMR between bacteria and within and between habitats. Considering plasmid-mediated spread is thus primordial to tackle the AMR threat. From a global perspective, doing so can provide important insight into the trajectories of ARG from animal or environmental reservoirs to human pathogens (e.g., the case of colistin resistance). From a more local perspective, the characterization of plasmids and integration of samples or isolates from the environment can be the missing piece to the puzzle in clinical investigations into the culprit behind a MDR plasmid-mediated infectious disease outbreak. The utility of this has been demonstrated by studies investigating the spread of carbapenem resistance within hospitals.

In recent years, a transition has occurred from descriptive research of MDR plasmids in the environment towards more hypothesis-driven research. This has been enabled by a combination of progress in molecular methods and the incorporation of ecological and evolutionary perspectives on AMR in the One Health context. With this approach, studies have shed light on how plasmid-mediated resistance emergence, transfer, and persistence in natural communities are complex and driven by mechanisms occurring at different biological levels. For example: 1) biofilms protract plasmid-host evolution, leading to increased genomic diversity, and also seem to act as refugia of plasmids that would go extinct otherwise; 2) low and transient concentrations of antibiotics or co-selecting agents can be sufficient to drive the emergence and spread of MDR plasmids; 3) the community context can either improve persistence of a plasmid or lead to its extinction; and 4) the rare microbiome may contain important players in the long term maintenance of MDR plasmids and their transmission. These insights would not have been possible without interdisciplinary and holistic approaches. It also opens questions on how these factors, and new ones to be discovered, act in concert in natural habitats (gut, soil, WWTP, etc.). While in vitro studies provide invaluable knowledge, it is now important to also incorporate experimental set-ups that aim to reflect the natural conditions of bacteria and their plasmids. Doing so will enable us to better predict the ARG trajectories that result in pathogens acquiring multi-drug resistance plasmids.

One of the ultimate goals of determining the ecological and evolutionary trajectories of MDR plasmids that result in MDR pathogens is to develop strategies to temper their spread (Box 3). Indeed, understanding the conditions that facilitate plasmid spread is only half the battle. As strategies continue to emerge, it is important to place their potential within the global context of MDR plasmid flow between habitats.

Box 3: Approaches for limiting spread of multi-drug resistance (MDR) plasmids.

Limiting the transfer of MDR plasmids within microbiomes and between habitats requires that we address plasmid spread at multiple biological levels. Here, we discuss proposed approaches to limit spread 1) within microbiomes and 2) between habitats.

Limiting plasmid spread in microbiomes

Several studies have focused on developing strategies to prevent plasmids from spreading by vertical or horizontal transfer. This has led to the identification of plasmid-curing compounds, of chemicals that can limit plasmid spread by inhibiting plasmid replication or conjugation160. Biological approaches for achieving this have also been identified. Some of the most promising include use of bacteriophages, transmissible incompatible vectors, and CRISPR-Cas9. Bacteriophages that bind to the plasmid-encoded mating pair complex have the potential to be used for curing resistance plasmids from a population161. The use of transmissible vectors relies on the natural inability of two plasmids with similar replication machinery to coexist stably over generations, also known as plasmid incompatibility162. Using plasmid incompatibility, researchers can design transmissible vectors able to displace a target plasmid from a population 163–165. With the CRISPR-Cas9 system, vectors carrying guide RNA designed to target specific plasmid replicons or ARG can create double-strand breaks leading to the loss of the MDR plasmid from a population166,167. Each of these approaches represent promising avenues for limiting the spread of MDR plasmids. For more detail on each method, we refer to recent reviews160,163.

Limiting plasmid spread on the One Health continuum

Strategies that target plasmid-containing cells or inhibit plasmid transfer in microbiomes could work as therapies but may not be suitable outside clinical settings. Limiting the transfer of plasmids between habitats, on a One Health scale, remains a major gap in fighting the AMR crisis.

Among the actions proposed, reducing the exposure of bacteria to selection and co-selection has been most often promoted by policymakers. Reducing exposure can be achieved by improving antibiotic stewardship. In this regard, banning the use of antibiotics as growth promoters in Europe, or their limitation in the US, has already been an important step forward. Improving the treatment of human or animal wastes to reduce environmental pollution with antimicrobials and addressing anthropogenic activities that enrich AMR are other proposed actions. Reducing exposure of bacteria to selection would slow down the emergence of new plasmid-mediated resistance originating from environmental bacteria. However, such actions may have a limited influence on resistance already widespread globally. As we discussed in the review, AMR can be found in many habitats where there is no selection for the retention of those plasmids. Experimental evolution work in the laboratory supports the idea that MDR plasmids can become ‘endemic’ to bacteria after very few generations of selection. Thus, the evolutionary trajectories leading to the formation of these host reservoirs might be irreversible. However, leveraging ecological tools and approaches can provide future directions to control AMR spread across the One Health continuum.

Improving sanitation and hygiene are also critical in reducing AMR transmission. Indeed, antibiotic consumption is not the only culprit. Sanitation and hygiene have been pointed out as major drivers of the AMR crisis168,169. Microbiome overlap between habitats likely enhances transmission of MDR plasmids17. Thus, reducing contact between bacteria from different habitats will ultimately reduce the cross-habitat exchange of MDR plasmids. Following the same reasoning, vaccines are also a promising strategy. Vaccines aid in reducing the number of pathogen infections and antibiotic consumption170, thereby limiting the emergence and spread of MDR plasmids.

Finally, to design intervention strategies able to curtail the emergence, evolution, and spread of AMR between habitats, it is critical to expanding current AMR surveillance to include a One Health perspective. This means integrating environmental surveillance of AMR with current surveillance systems such as the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) or the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS). Conceptual frameworks that address this shortcoming, and include monitoring of AMR in non-human habitats, have also been proposed171–173. In addition, multiple international and national joint actions pave the way to build One health surveillance of AMR174–176. Such frameworks need to additionally integrate surveillance of MDR plasmids and the hosts that carry them. Identification and characterization of these plasmids is a cornerstone in defining AMR risk177. However, there is currently no single approach in our toolbox that achieves the resolution needed to pinpoint the plasmids that mediate ARG transfer between habitats. Plasmid-mediated AMR surveillance may have to use a combination of multiple approaches. Ultimately, the information generated by surveillance efforts can guide policy and will continue to be important for addressing the global AMR crisis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Clinton Elg and Olivia Kosterlitz for critical reading of this manuscript. The authors were partially supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) grant no. 2018–67017-27630 of the United States Department of Agriculture, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Extramural Activities grant no. R01 AI084918 of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under grant number P30 GM103324.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Murray CJ et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/82532 (2019) doi: 10.15620/cdc:82532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2022 – 2020 data. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-europe-2022-2020-data (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report: 2021. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240027336 (2021).

- 5.Jonas OB, Irwin A, Berthe FCJ, Le Gall FG & Marquez PV Drug-resistant infections : a threat to our economic future (Vol. 2) : final report (English). (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antimicrobial resistance in the EU/EEA (EARS-Net) - Annual epidemiological report for 2021. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/surveillance-antimicrobial-resistance-europe-2021 (2022).

- 7.Liu Y-Y et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 161–168 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham DW, Knapp CW, Christensen BT, McCluskey S & Dolfing J Appearance of β-lactam resistance genes in agricultural soils and clinical isolates over the 20th century. Sci. Rep. 6, 21550 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsberg KJ et al. The shared antibiotic resistome of soil bacteria and human pathogens. Science 337, 1107–1111 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen HK et al. Call of the wild: antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 251–259 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry J, Waglechner N & Wright G The prehistory of antibiotic resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, a025197 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsson DGJ & Flach C-F Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 257–269 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersson DI et al. Antibiotic resistance: turning evolutionary principles into clinical reality. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44, 171–188 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy SB, Fitzgerald GB & Macone AB Spread of antibiotic-resistant plasmids from chicken to chicken and from chicken to man. Nature 260, 40–42 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pehrsson EC et al. Interconnected microbiomes and resistomes in low-income human habitats. Nature 533, 212–216 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smillie CS et al. Ecology drives a global network of gene exchange connecting the human microbiome. Nature 480, 241–244 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baquero F, Coque TM, Martínez J-L, Aracil-Gisbert S & Lanza VF Gene transmission in the One Health microbiosphere and the channels of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 10, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackenzie JS & Jeggo M The One Health approach—Why is it so important? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 4, 88 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panel (OHHLEP) OHH-LE. et al. One Health: A new definition for a sustainable and healthy future. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010537 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muehlenbein MP Human-wildlife contact and emerging infectious diseases. HEI 1, 79–94 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez-Beltrán J, DelaFuente J, León-Sampedro R, MacLean RC & San Millán Á Beyond horizontal gene transfer: the role of plasmids in bacterial evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 347–359 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawkey PM & Jones AM The changing epidemiology of resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64, i3–i10 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.When the drugs don’t work. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 1–2 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathers AJ, Peirano G & Pitout JDD The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 565–591 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang R et al. The global distribution and spread of the mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Nat. Commun. 9, 1179 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans DR Genomic epidemiology of horizontal plasmid transfer among healthcare-associated bacterial pathogens in a tertiary hospital. (University of Pittsburgh, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groussin M et al. Elevated rates of horizontal gene transfer in the industrialized human microbiome. Cell 184, 2053–2067 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redondo-Salvo S et al. Pathways for horizontal gene transfer in bacteria revealed by a global map of their plasmids. Nat. Commun. 11, 3602 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acman M, van Dorp L, Santini JM & Balloux F Large-scale network analysis captures biological features of bacterial plasmids. Nat. Commun. 11, 2452 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas CM & Nielsen KM Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 3, 711–721 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Che Y et al. Conjugative plasmids interact with insertion sequences to shape the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shintani M et al. Plant species-dependent increased abundance and diversity of IncP-1 plasmids in the rhizosphere: New insights into their role and ecology. Front. Microbiol. 11, 590776 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blau K et al. The transferable resistome of produce. mBio 9, e01300–18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heuer H et al. IncP-1ε plasmids are important vectors of antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural systems: Diversification driven by class 1 integron gene cassettes. Front. Microbiol. 3, 2 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kyselková M et al. Characterization of tet(Y)-carrying LowGC plasmids exogenously captured from cow manure at a conventional dairy farm. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Law A et al. Biosolids as a source of antibiotic resistance plasmids for commensal and pathogenic bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 12, 606409 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Chang W, Zhang H, Hu D & Wang X The role of plasmids in the multiple antibiotic resistance transfer in ESBLs-producing Escherichia coli isolated from wastewater treatment plants. Front. Microbiol. 10, 633 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahube TO, Viana LS, Koraimann G & Yost CK Characterization and comparative analysis of antibiotic resistance plasmids isolated from a wastewater treatment plant. Front. Microbiol. 5, 558 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De la Cruz Barrón M, Merlin C, Guilloteau H, Montargès-Pelletier E & Bellanger X. Suspended materials in river waters differentially enrich class 1 integron- and IncP-1 plasmid-carrying bacteria in sediments. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1443 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sriswasdi S, Yang C & Iwasaki W Generalist species drive microbial dispersion and evolution. Nat. Commun. 8, 1162 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berry D & Widder S Deciphering microbial interactions and detecting keystone species with co-occurrence networks. Front. Microbiol 5, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stalder T, Press MO, Sullivan S, Liachko I & Top EM Linking the resistome and plasmidome to the microbiome. ISME J 13, 2437–2446 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Che Y et al. Mobile antibiotic resistome in wastewater treatment plants revealed by Nanopore metagenomic sequencing. Microbiome 7, 44 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hultman J et al. Host range of antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater treatment plant influent and effluent. FEMS Microbiol. 94, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li L et al. Plasmids persist in a microbial community by providing fitness benefit to multiple phylotypes. ISME J. 14, 1170–1181 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galata V, Fehlmann T, Backes C & Keller A PLSDB: a resource of complete bacterial plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D195–D202 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nation RL & Li J Colistin in the 21st century. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22, 535–543 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snesrud E et al. A model for transposition of the Colistin resistance gene mcr-1 by ISApl1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 6973–6976 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meletis G Carbapenem resistance: overview of the problem and future perspectives. Ther Adv Infect Dis 3, 15–21 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munoz-Price LS et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 785–796 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cui X, Zhang H & Du H Carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae: Detection and antimicrobial therapy. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1823 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brink AJ Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative infections globally. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 32, 609–616 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cassini A et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19, 56–66 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MA & Bonomo RA Carbapenems: Past, present, and future ▿. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 4943–4960 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Farfour E et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales outbreak: Another dark side of COVID-19. Am J Infect Control 48, 1533–1536 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schweizer C et al. Plasmid-mediated transmission of KPC-2 carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae in critically ill patients. Front. Microbiol. 10, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tofteland S, Naseer U, Lislevand JH, Sundsfjord A & Samuelsen Ø A long-term low-frequency hospital outbreak of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae involving intergenus plasmid diffusion and a persistingenvironmental reservoir. PLOS ONE 8, e59015 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Evans DR et al. Systematic detection of horizontal gene transfer across genera among multidrug-resistant bacteria in a single hospital. eLife 9, e53886 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mathers AJ et al. Fatal cross infection by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella in two liver transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 11, 257–265 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mathers AJ et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-producing K. pneumoniae at a single institution: Insights into endemicity from whole-genome sequencing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. (2015) doi: 10.1128/AAC.04292-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheppard AE et al. Nested russian doll-like genetic mobility drives rapid dissemination of the carbapenem resistance gene blaKPC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 3767–3778 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mathers AJ et al. Klebsiella quasipneumoniae provides a window into carbapenemase gene transfer, plasmid rearrangements, and patient interactions with the hospital environment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weingarten RA et al. Genomic analysis of hospital plumbing reveals diverse reservoir of bacterial plasmids conferring carbapenem resistance. mBio 9, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stewart FM & Levin BR The population biology of bacterial plasmids: A PRIORI conditions for the existence of conjugationally transmitted factors. Genetics 87, 209–228 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lopatkin AJ et al. Persistence and reversal of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance. Nat. Commun. 8, 1689 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.San Millan A, Heilbron K & MacLean RC Positive epistasis between co-infecting plasmids promotes plasmid survival in bacterial populations. ISME J 8, 601–612 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dionisio F, Zilhão R & Gama JA Interactions between plasmids and other mobile genetic elements affect their transmission and persistence. Plasmid 102, 29–36 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gama JA, Zilhão R & Dionisio F Plasmid interactions can improve plasmid persistence in bacterial populations. Front. Microbiol. 11, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brockhurst MA & Harrison E Ecological and evolutionary solutions to the plasmid paradox. Trends Microbiol. 0, (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.MacLean RC & San Millan A Microbial evolution: Towards resolving the plasmid paradox. Curr. Biol. 25, R764–R767 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van Elsas JD & Bailey MJ The ecology of transfer of mobile genetic elements. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42, 187–197 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van Elsas JD, Fry J, Hirsch PR & Molin S Ecology of plasmid transfer and spread. in The Horizontal Gene Pool; Bacterial Plasmids and Gene Spread (ed. Thomas CM) 175–206 (Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heuer H & Smalla K Plasmids foster diversification and adaptation of bacterial populations in soil. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 1083–1104 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smalla K, Jechalke S & Top EM Plasmid detection, characterization and ecology. Microbiol. Spectr. 3, 10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0038-2014 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flemming H-C & Wuertz S Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 247–260 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stepanauskas R et al. Coselection for microbial resistance to metals and antibiotics in freshwater microcosms. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 1510–1514 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gómez-Sanz E et al. Novel erm(T)-carrying multiresistance plasmids from porcine and human isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 that also harbor cadmium and copper resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3275–3282 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Levison ME & Levison JH Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibacterial agents. Infect. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 23, 791–vii (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Paulus GK et al. The impact of on-site hospital wastewater treatment on the downstream communal wastewater system in terms of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 222, 635–644 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chow LKM, Ghaly TM & Gillings MR A survey of sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics in the environment. J. Environ. Sci. 99, 21–27 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaplan E, Marano RBM, Jurkevitch E & Cytryn E Enhanced bacterial fitness under residual fluoroquinolone concentrations is associated with increased gene expression in wastewater-derived ,qnr plasmid-harboring strains. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1176 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cairns J et al. Ecology determines how low antibiotic concentration impacts community composition and horizontal transfer of resistance genes. Commun. Biol. 1, 1–8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gullberg E, Albrecht LM, Karlsson C, Sandegren L & Andersson DI Selection of a multidrug resistance plasmid by sublethal levels of antibiotics and heavy metals. mBio 5, e01918–14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ngigi AN, Magu MM & Muendo BM Occurrence of antibiotics residues in hospital wastewater, wastewater treatment plant, and in surface water in Nairobi County, Kenya. Environ. Monit. Assess. 192, 18 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodriguez-Mozaz S et al. Antibiotic residues in final effluents of European wastewater treatment plants and their impact on the aquatic environment. Environ. Int. 140, 105733 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.He Y et al. Antibiotic resistance genes from livestock waste: occurrence, dissemination, and treatment. NPJ Clean Water 3, 1–11 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stanton IC, Murray AK, Zhang L, Snape J & Gaze WH Evolution of antibiotic resistance at low antibiotic concentrations including selection below the minimal selective concentration. Commun. Biol. 3, 1–11 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wein T, Hülter NF, Mizrahi I & Dagan T Emergence of plasmid stability under non-selective conditions maintains antibiotic resistance. Nat. Commun. 10, 2595 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hall JPJ, Wright RCT, Guymer D, Harrison E & Brockhurst MAY 2020. Extremely fast amelioration of plasmid fitness costs by multiple functionally diverse pathways. Microbiology 166, 56–62 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yao Y et al. Intra- and interpopulation transposition of mobile genetic elements driven by antibiotic selection. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1–10 (2022) doi: 10.1038/s41559-022-01705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lehtinen S, Huisman JS & Bonhoeffer S Evolutionary mechanisms that determine which bacterial genes are carried on plasmids. Evol. Lett. 5, 290–301 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schneiders S et al. Spatiotemporal variations in growth rate and virulence plasmid copy number during Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 89, e00710–20 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kasagaki S, Hashimoto M & Maeda S Subminimal inhibitory concentrations of ampicillin and mechanical stimuli cooperatively promote cell-to-cell plasmid transformation in Escherichia coli. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 3, 100130 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xiao X, Zeng F, Li R, Liu Y & Wang Z Subinhibitory concentration of colistin promotes the conjugation frequencies of Mcr-1- and blaNDM-5-positive plasmids. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lopatkin AJ et al. Antibiotics as a selective driver for conjugation dynamics. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16044 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu G, Thomsen LE & Olsen JE Antimicrobial-induced horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes in bacteria: a mini-review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 77, 556–567 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cyriaque V et al. Lead drives complex dynamics of a conjugative plasmid in a bacterial community. Front. Microbiol. 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yu Z, Wang Y, Lu J, Bond PL & Guo J Nonnutritive sweeteners can promote the dissemination of antibiotic resistance through conjugative gene transfer. ISME J 1–14 (2021) doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-00909-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hu X et al. Plasmid binding to metal oxide nanoparticles inhibited lateral transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Sci. Nano 6, 1310–1322 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Klümper U et al. Metal stressors consistently modulate bacterial conjugal plasmid uptake potential in a phylogenetically conserved manner. ISME J 11, 152–165 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Parra B, Tortella GR, Cuozzo S & Martínez M Negative effect of copper nanoparticles on the conjugation frequency of conjugative catabolic plasmids. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 169, 662–668 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xiong R et al. Indole inhibits IncP-1 conjugation system mainly through promoting korA and korB expression. Front. Microbiol. 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kosterlitz O et al. Estimating the transfer rates of bacterial plasmids with an adapted Luria–Delbrück fluctuation analysis. PLOS Biol. 20, e3001732 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Huisman JS et al. Estimating plasmid conjugation rates: A new computational tool and a critical comparison of methods. Plasmid 121, 102627 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cabezón E, de la Cruz F & Arechaga I Conjugation inhibitors and their potential use to prevent dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2329 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nahum JR et al. A tortoise–hare pattern seen in adapting structured and unstructured populations suggests a rugged fitness landscape in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 7530–7535 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Perfeito L, Pereira MI, Campos PRA & Gordo I The effect of spatial structure on adaptation in Escherichia coli. Biol. Lett. 4, 57–59 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.France MT & Forney LJ The relationship between spatial structure and the maintenance of diversity in microbial populations. Am. Nat. 193, 503–513 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yang Y, Liu G, Ye C & Liu W Bacterial community and climate change implication affected the diversity and abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in wetlands on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Hazard Mater. 361, 283–293 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Maciel-Guerra A et al. Dissecting microbial communities and resistomes for interconnected humans, soil, and livestock. ISME J 1–15 (2022) doi: 10.1038/s41396-022-01315-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.MacFadden DR, McGough SF, Fisman D, Santillana M & Brownstein JS Antibiotic resistance increases with local temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 510–514 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Louvet JN et al. Vancomycin sorption on activated sludge Gram+ bacteria rather than on EPS; 3D Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy time-lapse imaging. Water Research 124, 290–297 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kloos J, Gama JA, Hegstad J, Samuelsen Ø & Johnsen PJ Piggybacking on niche adaptation improves the maintenance of multidrug‐resistance plasmids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3188–3201 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stalder T et al. Evolving populations in biofilms contain more persistent plasmids. Mol Biol Evol 37, 1563–1576 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ponciano JM, La H-J, Joyce P & Forney LJ Evolution of diversity in spatially structured Escherichia coli populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6047–6054 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Boles BR, Thoendel M & Singh PK Self-generated diversity produces “insurance effects” in biofilm communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16630–16635 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Eastman JM, Harmon LJ, La H-J, Joyce P & Forney LJ The onion model, a simple neutral model for the evolution of diversity in bacterial biofilms. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 2496–2504 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Santos-Lopez A, Marshall CW, Scribner MR, Snyder DJ & Cooper VS Evolutionary pathways to antibiotic resistance are dependent upon environmental structure and bacterial lifestyle. eLife 8, e47612 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lewis K Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 999–1007 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Donlan RM Biofilms: Microbial life on surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8, 881–890 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Galié S, García-Gutiérrez C, Miguélez EM, Villar CJ & Lombó F Biofilms in the food industry: Health aspects and control methods. Front. Microbiol. 9, 898 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]