Abstract

Background:

The groin flap, a reliable pedicled flap first described by McGregor and Jackson, remains a valuable reconstructive option for digital soft tissue defects, especially in settings lacking microsurgical resources. Despite its widespread use, few studies have comprehensively assessed risk factors associated with flap failure and postoperative complications.

Methods:

A retrospective case–control study was conducted on 46 patients who underwent groin flap reconstruction for finger defects between 2015 and 2024. Patients were grouped according to flap success and the occurrence of postoperative complications. Demographic, clinical, and operative variables were compared using appropriate statistical tests.

Results:

Flap success was achieved in 93.5% (n = 43) of cases. Flap failure (n = 3) was associated with higher body mass index (BMI) (29.1 versus 24.5), smaller flap width (3.3 versus 5.5 cm, P = 0.02), and shorter operative time (37.7 versus 55.2 min, P = 0.02). Among the 17 patients (37%) who developed complications, smoking (100% versus 72.4%, P = 0.017), higher BMI (27.1 versus 23.4, P = 0.008), and venous congestion (94.1% versus 17.2%, P < 0.001) were significant predictors. Other variables, including defect and flap size, were not statistically different between groups.

Conclusions:

Groin flaps offer high success rates for finger reconstruction; however, increased BMI, smoking, and venous congestion are significant risk factors for postoperative complications. These findings underscore the importance of patient optimization and vigilant postoperative monitoring to improve surgical outcomes.

Takeaways

Question: What are the clinical outcomes, complication rates, and functional and aesthetic results of groin flap reconstruction in patients with finger defects?

Findings: Groin flap reconstruction for finger defects achieved a high flap success rate (93.5%) with most patients reporting minimal to mild disability and acceptable aesthetic results; complications were more likely in smokers and those with smaller defect sizes.

Meaning: Groin flaps provide a dependable and effective solution for complex finger soft tissue coverage, balancing functional recovery and cosmetic satisfaction, especially in settings without access to microsurgical reconstruction.

INTRODUCTION

The hand plays a central role in performing a wide range of daily functions, placing the fingers specifically at the risk of soft tissue injuries. In clinical practice, those injuries are frequently encountered, which may result from various mechanisms, including mechanical, thermal, electrical, and traumatic injuries.1,2 Urgent and effective reconstruction is critical, with achieving optimal hand function being the main goal in management.

Since the original description by McGregor and Jackson in 1972, pedicled groin flaps have remained a reliable option for the repair of extensive soft tissue injuries.3 Technical simplicity, safety profile, and versatility have made pedicled groin flaps an endurable option for managing various hand and finger defects.4,5 Pedicled groin flaps have been successfully used in the reconstruction of hand and finger defects resulting from a variety of injuries, including burns, malignant excision, crash injuries, degloving trauma, and electrical injuries.2,6–9

Although microvascular surgery has drastically advanced the reconstruction of soft tissue defects, its widespread application is limited due to lack of specialized equipment and surgical expertise, especially in resource-limited settings. This made pedicled groin flaps a realistic and practical alternative in such contexts, especially in high-risk patients.6,10

In this study, our goal was to report our experience with the use of groin flaps for the reconstruction of soft tissue defects in finger injuries. In addition, we aimed to evaluate the clinical and functional outcomes and identify patients’ characteristics and operative parameters that may influence flap viability and incidence of postoperative complications.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

This multicenter retrospective case–control study was conducted to assess the outcomes and identify potential risk factors associated with complications and failure of groin flap procedures used in finger reconstruction in Jordan, covering cases performed between January 2015 and June 2024. Patients were grouped into 2 cohorts based on flap survival status, successful versus failed flaps, and further stratified according to the presence or absence of postoperative complications. Comparative analysis was performed to explore associations between these outcomes and various demographic, surgical, and postoperative variables.

All patients who underwent groin flap reconstruction for soft tissue defect of the fingers during the study period were eligible for inclusion. A census sampling approach was used, ensuring that every case meeting the inclusion criteria was analyzed. Eligibility criteria required that groin flaps be used as the primary reconstructive method, with a minimum postoperative follow-up of 6 months. Patients were excluded if groin flaps were not the main technique or if postoperative documentation was incomplete.

Data Collection Procedures

Patient data were retrieved retrospectively from electronic health records, paper-based charts, operative reports, surgical logbooks, and follow-up clinical notes from all participating institutions. A standardized data extraction form was used to collect key variables, including demographic information (age, sex, comorbid conditions, smoking status), characteristics of the defect (size, cause), and intraoperative details (flap type, pedicle length, flap dimensions and design, and venous congestion). Additional surgical interventions, such as flap debulking, pseudosyndactyly division, tendon repair, or tendon grafting, were also recorded. Primary outcome measures included flap viability (categorized as successful or failed), as well as postoperative complications and wound healing duration. Functional outcome was assessed during follow-up visits, as documented in the clinical notes, using the quick disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH) score. For aesthetic outcomes, the Vancouver Scar Scale was used to assess the quality of scarring at both the groin flap and donor site, and patient satisfaction was evaluated using a Likert score.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi version 2.5.4. Descriptive statistics—means, medians, SDs, and proportions—were used to summarize patient characteristics and surgical outcomes. Associations between clinical variables (such as age, comorbidities, defect site, and flap type) and flap outcomes were explored using χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical data and independent t tests for continuous variables. A 2-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol received ethical approval from the institutional review board (IRB) of Al-Balqa Applied University. As this was a retrospective study using anonymized patient data, the requirement for informed consent was waived. Confidentiality was strictly upheld through data de-identification and secure handling procedures.

RESULTS

A total of 46 patients underwent groin flap reconstruction for finger defects, with a mean age of 26.5 (SD 6.8) years and a male predominance (87%). Most patients were smokers (82.6%) and had no reported comorbidities. Injuries were evenly distributed between the right and left hands, with degloving (43.5%) and crushing injuries (30.4%) being the most common causes. More than half of the cases (56.5%) involved secondary defects. The average defect area was 33.4 cm², and the corresponding mean flap size was 70.7 cm², primarily designed as tubular flaps (63%). The mean operative time was 54.1 minutes, and additional procedures were required in 65.2% of cases. The average wound healing time was 32.3 days. Intraoperative venous congestion occurred in 21 (45.7%) patients. Postoperative complications occurred in 37% of patients, most commonly partial necrosis, followed by wound dehiscence and infection. The average hospital stay was short (3.2 d), and donor site complications were infrequent (8.7%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Surgical Characteristics of Patients Who Underwent Finger Groin Flaps (N = 46)

| Total (N = 46) | |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Mean (SD) | 26.5 (6.8) |

| Range | 14.0–49.0 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 6.0 (13.0) |

| Male | 40.0 (87.0) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| No | 46.0 (100.0) |

| Smoking, n (%) | |

| No | 8.0 (17.4) |

| Yes | 38.0 (82.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |

| Mean (SD) | 24.8 (4.8) |

| Range | 17.0–33.1 |

| Side, n (%) | |

| Left | 23.0 (50.0) |

| Right | 23.0 (50.0) |

| Injury type, n (%) | |

| Burn | 3.0 (6.5) |

| Postop skin loss | 6.0 (13.0) |

| Crushed | 14.0 (30.4) |

| Degloving | 20.0 (43.5) |

| Infection | 3.0 (6.5) |

| Defect, n (%) | |

| Primary | 20.0 (43.5) |

| Secondary | 26.0 (56.5) |

| Defect length, cm | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 (2.2) |

| Range | 4.0–12.0 |

| Defect width, cm | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.7) |

| Range | 2.0–8.0 |

| Defect size, cm² | |

| Mean (SD) | 33.4 (19.7) |

| Range | 8.0–96.0 |

| Flap length, cm | |

| Mean (SD) | 12.6 (2.5) |

| Range | 8.0–18.0 |

| Flap width, cm | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.4 (1.7) |

| Range | 3.0–10.0 |

| Flap size, cm² | |

| Mean (SD) | 70.7 (33.6) |

| Range | 24.0–180.0 |

| Operation time, min | |

| Mean (SD) | 54.1 (15.4) |

| Range | 32.0–120.0 |

| Angle of rotation, degrees | |

| Classic | 17.0 (37.0) |

| Tube | 29.0 (63.0) |

| Additional procedure, n (%) | |

| No | 16.0 (34.8) |

| Yes | 30.0 (65.2) |

| No. additional procedures, n (%) | |

| 1 | 20.0 (43.5) |

| 2 | 4.0 (8.7) |

| 3 | 1.0 (2.2) |

| 4 | 1.0 (2.2) |

| 5 | 1.0 (2.2) |

| 6 | 3.0 (6.5) |

| Wound healing time, d | |

| Mean (SD) | 32.3 (9.1) |

| Range | 23.0–60.0 |

| Postop complication, n (%) | |

| No | 29.0 (63.0) |

| Yes | 17.0 (37.0) |

| Intraoperative venous congestion, n (%) | |

| No | 25.0 (54.3) |

| Yes | 21.0 (45.7) |

| Wound infection, n (%) | |

| No | 41.0 (89.1) |

| Yes | 5.0 (10.9) |

| Wound dehiscence, n (%) | |

| No | 39.0 (84.8) |

| Yes | 7.0 (15.2) |

| Partial necrosis, n (%) | |

| No | 35.0 (76.1) |

| Yes | 11.0 (23.9) |

| Hospital stay, d | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (2.9) |

| Range | 1.0–18.0 |

| Donor-site complication, n (%) | |

| No | 42.0 (91.3) |

| Yes | 4.0 (8.7) |

| Aesthetic outcome, Likert score, n (%) | |

| Excellent | 6.0 (13.0) |

| Good | 16.0 (34.8) |

| Neutral | 22.0 (47.8) |

| Very poor | 2.0 (4.3) |

| Aesthetic outcome, VSS, n (%) | |

| Normal | 17.0 (37.0) |

| Mild | 15.0 (32.6) |

| Moderate | 11.0 (23.9) |

| Severe | 3.0 (6.5) |

| Functional outcomes, QuickDASH, n (%) | |

| Minimal disability | 26.0 (56.5) |

| Mild disability | 13.0 (28.3) |

| Moderate disability | 3.0 (6.5) |

| Severe disability | 4.0 (8.7) |

| QuickDASH score, n (%) | |

| Mean (SD) | 17.4 (18.7) |

| Range | 2.5–64.1 |

| Flap success, n (%) | |

| Failed | 3.0 (6.5) |

| Success | 43.0 (93.5) |

BMI, body mass index; Postop, postoperative; VSS, Vancouver Scar Scale.

Regarding aesthetic outcomes, most patients rated their result as neutral (47.8%) or good (34.8%) on the Likert scale, whereas 13% rated it as excellent. Vancouver Scar Scale scores indicated that 37% of patients had normal scarring and 32.6% had mild scarring. Functionally, based on the QuickDASH assessment, 56.5% of patients reported minimal disability, with a mean QuickDASH score of 17.4 (SD 18.7). The overall flap success rate was high, with 93.5% of flaps surviving successfully (Table 1).

Comparison Between Successful and Failed Flap Outcomes

Table 2 presents a comparison of continuous variables between patients with failed (3) and successful (43) groin flaps. The mean age was slightly higher in the failed group (28 y) compared with that in the successful group (26.4 y), with no statistically significant difference. Patients in the failed group had a higher average body mass index (BMI) (29.1 versus 24.5), suggesting a potential trend toward poorer outcomes with increased body mass. Although defect length was comparable between groups, the failed group exhibited smaller defect widths (mean 2.7 versus 4.4 cm), with a P value of 0.08, nearing statistical significance. Similarly, the average defect size was notably smaller in the failed group (19.3 versus 34.4 cm²), though not statistically significant (P = 0.12). In terms of flap dimensions, flap length was similar across both groups, but flap width was significantly smaller in failed cases (3.3 versus 5.5 cm, P = 0.02), suggesting that insufficient flap width may contribute to failure. Consequently, the mean flap size was also smaller in the failed group (42 versus 72.7 cm², P = 0.06). Notably, the operative time was significantly shorter in the failed group (37.7 versus 55.2 min, P = 0.02), potentially reflecting technical or procedural differences. Functional outcomes as measured by the QuickDASH score were similar between groups (17.8 versus 17.4, P = 0.51), indicating that failure did not necessarily translate to higher long-term disability in this small subgroup (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Continuous Variables Between Failed and Successful Flaps

| Group Descriptives | Group | n | Mean | Median | SD | SE | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | Failed | 3 | 28 | 26 | 7.211 | 4.163 | 0.69 |

| Success | 43 | 26.4 | 25 | 6.82 | 1.041 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | Failed | 3 | 29.07 | 30.2 | 2.686 | 1.551 | 0.11 |

| Success | 43 | 24.46 | 24 | 4.75 | 0.725 | ||

| Defect length, cm | Failed | 3 | 7.33 | 7 | 0.577 | 0.333 | 0.95 |

| Success | 43 | 7.42 | 7 | 2.23 | 0.34 | ||

| Defect width, cm | Failed | 3 | 2.67 | 3 | 0.577 | 0.333 | 0.08 |

| Success | 43 | 4.37 | 4 | 1.68 | 0.256 | ||

| Defect size, cm2 | Failed | 3 | 19.33 | 21 | 2.887 | 1.667 | 0.12 |

| Success | 43 | 34.42 | 28 | 20.01 | 3.051 | ||

| Flap length, cm | Failed | 3 | 12.67 | 13 | 0.577 | 0.333 | 0.82 |

| Success | 43 | 12.6 | 12 | 2.6 | 0.397 | ||

| Flap width, cm | Failed | 3 | 3.33 | 3 | 0.577 | 0.333 | 0.02 |

| Success | 43 | 5.53 | 6 | 1.64 | 0.25 | ||

| Flap size, cm2 | Failed | 3 | 42 | 39 | 5.196 | 3 | 0.06 |

| Success | 43 | 72.72 | 70 | 33.87 | 5.166 | ||

| Operation time first stage, min | Failed | 3 | 37.67 | 40 | 4.933 | 2.848 | 0.02 |

| Success | 43 | 55.23 | 54 | 15.24 | 2.325 | ||

| Wound healing time, d | Failed | 3 | 29.33 | 29 | 5.508 | 3.18 | 0.072 |

| Success | 43 | 32.51 | 29 | 9.35 | 1.425 | ||

| QuickDASH score | Failed | 3 | 17.81 | 20.1 | 6.758 | 3.902 | 0.51 |

| Success | 43 | 17.4 | 4.6 | 19.3 | 2.943 |

BMI, body mass index; SE, standard error.

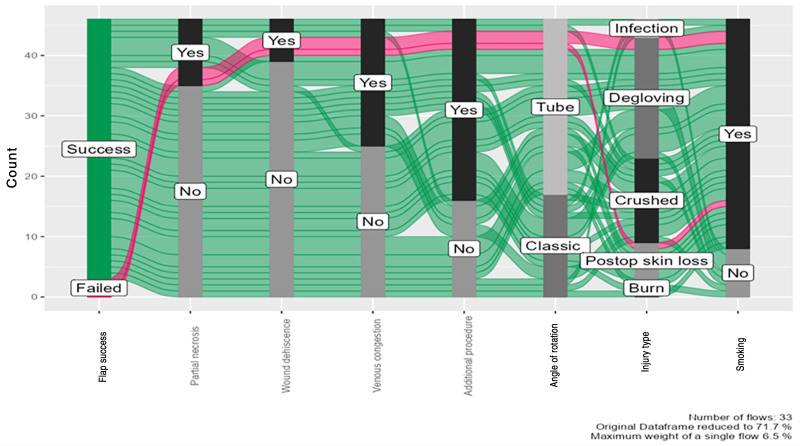

The alluvial diagram illustrates the relationships between key variables influencing flap success. The majority of cases resulted in successful flaps, with a small proportion experiencing failure. Notably, smoking was more prevalent among patients with failed flaps. Degloving injuries were the primary causes of defects, followed by infections and postoperative skin loss. The classic flap technique was preferred over the tube rotation method. Additionally, a significant proportion of patients underwent additional procedures. Overall, these findings suggest that smoking status, defect characteristics, and procedural factors may influence clinical outcomes following groin flap reconstruction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Alluvial diagram—the flow of categorical variables related to flap success. Postop, postoperative.

Risk Factors Associated with Postoperative Complications

Table 3 compares clinical and demographic characteristics between patients who developed postoperative complications and those who did not. Significant differences were observed in smoking status, BMI, and venous congestion. All patients in the complication group were smokers compared with 72.4% in the no-complication group (P = 0.017), and patients with complications had significantly higher BMI (mean 27.1 versus 23.4; P = 0.008). Venous congestion was strongly associated with complications, occurring in 94.1% of the patients in the complication group compared with only 17.2% of those in the no-complication group (P < 0.001), and its duration was also significantly longer in the complication group (mean 13.4 versus 8.8 d; P = 0.013). Other variables such as age, sex, defect size, flap characteristics, operation time, and healing time showed no statistically significant differences between groups. These findings suggest that higher BMI, smoking, and venous congestion are key risk factors for postoperative complications in this patient population (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison Between Patients Who Developed Complications and Those Who Did Not

| No Complication Group (N = 29) | Complication Group (N = 17) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 0.067* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 25.1 (5.3) | 28.9 (8.4) | |

| Range | 14.0–35.0 | 17.0–49.0 | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.106† | ||

| Female | 2.0 (6.9) | 4.0 (23.5) | |

| Male | 27.0 (93.1) | 13.0 (76.5) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.017† | ||

| No | 8.0 (27.6) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Yes | 21.0 (72.4) | 17.0 (100.0) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.008* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 23.4 (4.0) | 27.1 (5.1) | |

| Range | 17.0–31.6 | 19.3–33.1 | |

| Side, n (%) | 0.359† | ||

| Left | 13.0 (44.8) | 10.0 (58.8) | |

| Right | 16.0 (55.2) | 7.0 (41.2) | |

| Injury type, n (%) | 0.718† | ||

| Burn | 3.0 (10.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Postop skin loss | 4.0 (13.8) | 2.0 (11.8) | |

| Crushed | 8.0 (27.6) | 6.0 (35.3) | |

| Degloving | 12.0 (41.4) | 8.0 (47.1) | |

| Infection | 2.0 (6.9) | 1.0 (5.9) | |

| Defect, n (%) | 0.708† | ||

| Primary | 12.0 (41.4) | 8.0 (47.1) | |

| Secondary | 17.0 (58.6) | 9.0 (52.9) | |

| Defect length, cm | 0.575* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.6 (2.2) | 7.2 (2.0) | |

| Range | 4.0–12.0 | 4.0–12.0 | |

| Defect width, cm | 0.179* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.5 (1.7) | 3.8 (1.6) | |

| Range | 2.0–8.0 | 2.0–8.0 | |

| Defect size, cm2 | 0.266* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 35.9 (19.2) | 29.2 (20.3) | |

| Range | 8.0–72.0 | 8.0–96.0 | |

| Flap length, cm | 0.779* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 12.7 (2.4) | 12.5 (2.8) | |

| Range | 9.0–17.0 | 8.0–18.0 | |

| Flap width, cm | 0.117* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.7 (1.4) | 4.9 (2.1) | |

| Range | 3.0–8.0 | 3.0–10.0 | |

| Flap size, cm | 0.369* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 74.2 (27.6) | 64.8 (42.3) | |

| Range | 30.0–136.0 | 24.0–180.0 | |

| Operation time, min | 0.633* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 54.9 (11.3) | 52.6 (21.0) | |

| Range | 34.0–74.0 | 32.0–120.0 | |

| Angle of rotation, degrees | 0.149† | ||

| Classic | 13.0 (44.8) | 4.0 (23.5) | |

| Tube | 16.0 (55.2) | 13.0 (76.5) | |

| Wound healing time, d | 0.738* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 32.7 (10.4) | 31.7 (6.7) | |

| Range | 23.0–60.0 | 24.0–45.0 | |

| Hospital stay, d | 0.655* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.1) | 3.5 (4.0) | |

| Range | 2.0–10.0 | 1.0–18.0 | |

| Intraoperative venous congestion, n (%) | <0.001† | ||

| No | 24.0 (82.8) | 1.0 (5.9) | |

| Yes | 5.0 (17.2) | 16.0 (94.1) | |

| Intraoperative venous congestion duration, d | 0.013* | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8.8 (3.0) | 13.4 (3.3) | |

| Range | 7.0–14.0 | 7.0–17.0 | |

| Additional procedure, n (%) | 0.220† | ||

| No | 12.0 (41.4) | 4.0 (23.5) | |

| Yes | 17.0 (58.6) | 13.0 (76.5) | |

| If yes: no. additional procedures | |||

| 1 | 13.0 (44.8) | 7.0 (41.2) | |

| 2 | 1.0 (3.4) | 3.0 (17.6) | |

| 3 | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (5.9) | |

| 4 | 1.0 (3.4) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| 5 | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (5.9) | |

| 6 | 2.0 (6.9) | 1.0 (5.9) | |

Linear model analysis of variance.

Pearson χ2 test.

BMI, body mass index; Postop, postoperative.

DISCUSSION

This multicenter retrospective case–control study demonstrated a high overall success rate (93.5%) for groin flap procedures in finger reconstruction, with acceptable aesthetic and functional outcomes. However, complications were observed in 37% of cases, most commonly venous congestion, partial necrosis, and wound dehiscence. Flap failure was rare but seemed to be associated with narrower flap dimensions, shorter operative times, and higher BMI. Additionally, patients who developed postoperative complications were more likely to be smokers and have higher BMI, with venous congestion emerging as a significant predictor. These findings highlight the groin flap’s reliability in reconstructive hand surgery while underscoring key risk factors that may compromise outcomes.

Finger injuries that require flap reconstruction are prevalent in both industrialized and developing countries, and they are frequently due to machinery accidents, crush trauma, or road traffic accidents. Male predominance has been consistently reported in hand and finger injuries, especially in the age group between 15 and 35 years. In general, this is attributed to increased participation in mechanical work, contact sports, and lack of proper safety measures.1,9,11,12 In our series, patients with a mean age of 26.5 (range, 14–49) years had finger injuries, and 87% of them were men, reflecting this global demographic distribution.

In comparison to existing literature, our findings demonstrate favorable functional and aesthetic outcomes following groin flap reconstruction for finger defects. Aesthetic satisfaction was largely positive, and functionally, the QuickDASH score revealed minimal disability in the majority of patients. Notably, there was no significant difference in functional outcomes between patients with flap failure and those with successful outcomes (17.8 versus 17.4, P = 0.51), indicating that even among those who experienced partial flap loss, long-term disability was not necessarily exacerbated. Our results compare favorably with those of prior studies. For instance, Altuntas et al13 reported significantly higher QuickDASH scores in pedicled groin flap patients, suggesting substantial disability (subacute mean = 92, chronic mean = 72), whereas free flaps yielded more moderate impairments (subacute mean = 52, chronic mean = 24). Likewise, Żyluk1 found a mean QuickDASH score of 21.5, with most patients experiencing residual stiffness and pain, and only 2 regaining full range of motion. The relatively low mean QuickDASH score observed in our cohort may reflect superior functional preservation resulting from more refined surgical techniques and rehabilitation protocols, warranting further investigation into the impact of standardized postoperative care on functional outcomes.

However, it is also important to consider that fingertip injuries often heal well with secondary intention.14 In some cases, a groin flap may not have been necessary.15 Moreover, even when successful, groin flaps do not provide normal fingertip skin and cannot fully address issues such as stiffness, numbness, or other posttraumatic limitations.16 These observations underscore the importance of careful patient selection and setting realistic expectations for functional recovery.

In our series of 46 patients, the overall flap success rate was 93.5%, which falls within the range reported in the literature (60%–95%).17 This reaffirms the groin flap’s reliability when appropriately selected and performed. All cases of flap failure occurred in patients with higher BMI, with a mean BMI of 29.1 kg/m2compared with 24.5 kg/m2 in the successful group. These findings support previous studies that identify obesity as a negative prognostic factor in reconstructive surgery.18,19 The detrimental impact of obesity may be due to impaired tissue perfusion, delayed wound healing, and the pro-inflammatory state associated with increased adiposity.20 Interestingly, flap failures were associated with shorter operating times and smaller defects and flap dimensions. This may suggest that technically simpler reconstructions may be associated with a higher risk of complications due to potentially reduced surgical vigilance, suggesting that maintaining consistent operative standards across all case complexities could improve outcomes. Future investigations should systematically explore this observation by comparing complication rates, surgical techniques, and intraoperative decision-making processes across cases of varying complexities to determine whether case simplicity truly correlates with reduced attention and poorer outcomes.

In the small subset of patients who experienced flap failure in our cohort, smoking was prevalent among these cases, supporting previous research that links tobacco use to impaired vascular perfusion and delayed tissue healing.21–24 Furthermore, flap failures were more commonly associated with smaller flap widths. This may reflect the inherent challenges of ensuring adequate vascular supply in confined anatomical regions, where limited perfusion and greater technical demands could increase the risk of failure.25,26

Despite the high overall success rate, postoperative complications occurred in 17 (37%) patients. Intraoperative venous congestion emerged as the most common and significant risk factor for developing postoperative complications, occurring in 94.1% of the patients in the complication group compared with 17.2% in the no-complication group (P < 0.001). The duration of venous congestion was also significantly longer in the complication group (mean 13.4 versus 8.8 d; P = 0.013). Venous congestion is a well-documented challenge in flap surgery, and prompt recognition and intervention are critical to prevent flap loss.2,27

Higher BMI was also significantly associated with postoperative complications (mean 27.1 versus 23.4; P = 0.0081), reinforcing the role of patient-related factors in surgical recovery. Smoking was another significant predictor of complications: all 17 patients who developed complications were smokers, compared with 72.4% in the group without complications (P = 0.017). These findings are consistent with previous reports of higher complication rates in smokers undergoing various flap procedures, including head and neck reconstruction and breast reconstruction with free flaps.22,28,29 These findings shed light on the need for preoperative optimization and implementation of smoking cessation protocols wherever feasible.

In contrast, anatomical factors such as defect size and flap dimensions were not significantly different between complication groups, suggesting that these variables may not independently predict postoperative complications.30 Nonetheless, they remain essential considerations in surgical planning.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, its retrospective design may introduce selection and information bias, with potential inconsistencies in the documentation of clinical variables. Second, the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. Third, unmeasured confounders such as surgeon experience, intraoperative techniques, and postoperative care compliance could have influenced the outcomes.

Despite these limitations, the study also has notable strengths. It provides focused, clinically relevant insight into the outcomes of groin flaps for finger reconstruction in a real-world, resource-limited setting. The analysis of both flap success and complication risk factors, including modifiable variables such as BMI and smoking status, offers valuable guidance for patient selection and preoperative optimization. Furthermore, the study is among the few that quantitatively examine the relationship between flap dimensions, operative time, and outcomes, contributing to the evidence base on this widely used reconstructive technique.

CONCLUSIONS

The groin flap remains a reliable and effective reconstructive option for complex finger injuries, particularly in settings with limited access to microsurgical techniques. Our findings demonstrate a high success rate but highlight the influence of modifiable risk factors such as BMI, smoking, and venous congestion on postoperative complication rates. These results emphasize the importance of comprehensive preoperative assessment, patient education, and risk factor optimization. Future prospective, multicenter studies with larger sample sizes and long-term follow-up are warranted to further validate these findings and guide best practices in flap selection and perioperative management.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

PATIENT CONSENT

The requirement for written informed consent was waived for this study due to its retrospective design and the use of anonymized data. This waiver was approved by the IRBs of all participating centers, in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to all individuals who have contributed to the successful completion of this research endeavor. Their unwavering support, expertise, and dedication have been crucial in advancing the authors’ understanding of outcomes of groin flap for finger reconstruction in Jordan. The authors express their deepest appreciation to the IRB at Al-Balqa Applied University for their meticulous review and invaluable feedback, ensuring the ethical conduct of the study and safeguarding the safety of participants. This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Al-Balqa Applied University.

Footnotes

Published online 16 September 2025.

Disclosure statements are at the end of this article, following the correspondence information.

The data underlying this article are available in the article and upon request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Żyluk A. Outcomes of coverage of the soft tissue defects in the hand with a groin flap. Pol Przegl Chir. 2022;95:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amouzou KS, Berny N, El Harti A, et al. The pedicled groin flap in resurfacing hand burn scar release and other injuries: a five-case series report and review of the literature. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2017;30:57–61 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGregor IA, Jackson IT. The groin flap. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Qattan MM, Al-Qattan AM. Defining the indications of pedicled groin and abdominal flaps in hand reconstruction in the current microsurgery era. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:917–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naalla R, Chauhan S, Dave A, et al. Reconstruction of post-traumatic upper extremity soft tissue defects with pedicled flaps: an algorithmic approach to clinical decision making. Chin J Traumatol. 2018;21:338–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdelrahman M, Zelken J, Huang RW, et al. Suprafascial dissection of the pedicled groin flap: a safe and practical approach to flap harvest. Microsurgery. 2018;38:458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hidajat NN, Damayanthi ED, Akbar HF, et al. Replantation using groin flap in thirty-four years old male with traumatic total degloving of little finger: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;108:108377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta P, Tawar RS, Malviya M. Groin flap in paediatric age group to salvage hand after electric contact burn: challenges and experience. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:PC01–PC03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohd Amin MF, Harun Nor Rashid SA, Wan Sulaiman WA, et al. Ancient but efficient: two case reports of pedicle-tubed groin flap for soft tissue coverage in upper limb defects. Cureus. 2022;14:e23610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Climo MS. Split groin flap. Ann Plast Surg. 1978;1:489–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen CF, Mulder S, Johansen AMT, et al. The epidemiology of hand injuries in the Netherlands and Denmark. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorock GS, Lombardi DA, Hauser R, et al. A case-crossover study of transient risk factors for occupational acute hand injury. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:305–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altuntas SH, Dilek OF, Gurdal O, et al. The use of groin flap for hand defects: which should be prior, free or pedicled, based on patient-reported outcomes? Selcuk Univ Med J. 2023;39:128–134. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krauss EM, Lalonde DH. Secondary healing of fingertip amputations: a review. Hand (N Y). 2014;9:282–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pencle F, Doehrmann R, Waseem M. Fingertip injuries. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner RD, Carr L, Netscher DT. Current indications for abdominal-based flaps in hand and forearm reconstruction. Injury. 2020;51:2916–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goertz O, Kapalschinski N, Daigeler A, et al. The effectiveness of pedicled groin flaps in the treatment of hand defects: results of 49 patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:2088–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacMahon A, Rao SS, Chaudhry YP, et al. Preoperative patient optimization in total joint arthroplasty—the paradigm shift from preoperative clearance: a narrative review. HSS J. 2022;18:418–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spear SL, Ducic I, Cuoco F, et al. Effect of obesity on flap and donor-site complications in pedicled TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:788–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franz S, Ertel A, Engel KM, et al. Overexpression of S100A9 in obesity impairs macrophage differentiation via TLR4-NFkB-signaling worsening inflammation and wound healing. Theranostics. 2022;12:1659–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan Chiang YH, Lee YW, Lam F, et al. Smoking increases the risk of postoperative wound complications: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Int Wound J. 2023;20:391–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garip M, Van Dessel J, Grosjean L, et al. The impact of smoking on surgical complications after head and neck reconstructive surgery with a free vascularised tissue flap: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;59:e79–e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDaniel JC, Browning KK. Smoking, chronic wound healing, and implications for evidence-based practice. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2014;41:415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spear SL, Ducic I, Cuoco F, et al. The effect of smoking on flap and donor-site complications in pedicled TRAM breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1873–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto T, Yamamoto N, Kageyama T, et al. Supermicrosurgery for oncologic reconstructions. Glob Health Med. 2020;2:18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khurshid J, Mir B, Bhat B. Cross-finger flaps outcome and modification. Int J Res Rev. 2023;10:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boissiere F, Gandolfi S, Riot S, et al. Flap venous congestion and salvage techniques: a systematic literature review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:e3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrl D, Heidekrüger PI, Haas EM, et al. Does cigarette smoking harm microsurgical free flap reconstruction? J Reconstr Microsurg. 2018;34:492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puyana S, Puyana C, Hajebian HH, et al. Smoking as a risk factor for forehead flap wound outcomes: an analysis of 1030 patients. Eplasty. 2022;22:e55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arner M, Möller K. Morbidity of the pedicled groin flap. A retrospective study of 44 cases. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1994;28:143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]