Abstract

Purpose

Gallbladder cancer is a highly aggressive malignancy with disproportionate incidence in the Gangetic belt of India. Early diagnosis is critical yet most patients present with advanced-stage disease. Serum tumor markers like CEA and Ca 19.9 are often elevated in gallbladder cancer, but their role in rapidly triaging patients for metastatic disease at presentation has not been prospectively validated in prospective cohort.

Methods

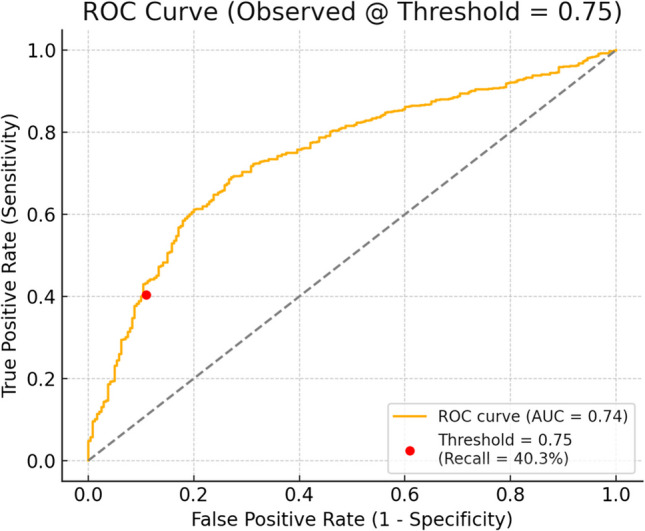

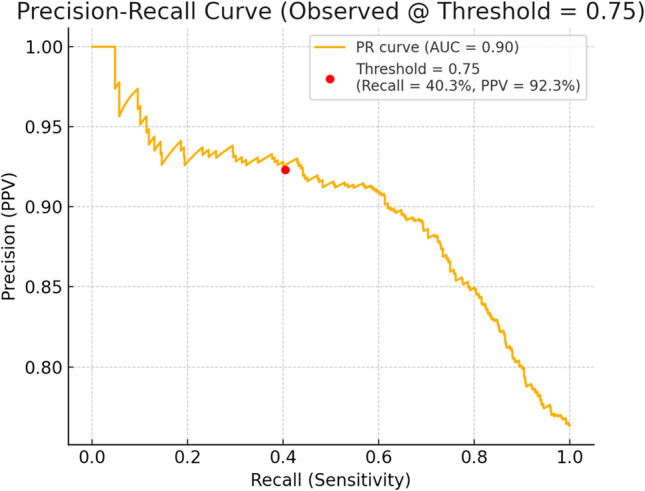

This sub-analysis is part of a larger prospective observational study conducted at a tertiary cancer center in North India. A total of 1500 newly diagnosed, treatment-naïve or incidental gallbladder cancer patients were enrolled between September 2023 and May 2024. Serum CEA and Ca 19.9 levels were measured at baseline. Diagnostic thresholds were derived using the 75th percentile values stratified by obstructive jaundice status. Diagnostic accuracy for predicting metastatic disease was assessed using confusion matrices, ROC curves, and precision-recall analysis.

Results

Of 1500 patients, 1203 (80.2%) presented with metastatic disease. Serum data were available for 1011 patients. Patients with metastatic disease had significantly higher marker levels (CEA: mean 288.4 vs. 22.9 ng/mL; Ca 19.9: 20,917 vs. 2241 U/mL). The model showed high specificity (89.1%) and positive predictive value (92.3%) with moderate AUC (0.74). Sensitivity was limited (40.3%), suggesting strong “rule-in” but weak “rule-out” capability.

Conclusions

Elevated serum CEA and Ca 19.9 adjusted for jaundice status are strong indicators of metastatic gallbladder cancer at presentation. This real-world percentile-based approach offers a rapid, low-cost diagnostic adjunct for early triage in resource-limited settings. The findings provide context-sensitive thresholds that may aid timely treatment decisions in high-burden regions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12029-025-01317-6.

Keywords: CEA, Ca 19.9, Gallbladder cancer, Ca GB, Metastatic

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) remains one of the most aggressive and understudied malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract, with disproportionately high incidence and mortality in specific regions of the world like the Gangetic belt of northern India [1, 2]. Despite being one of the most common biliary tract malignancies, GBC continues to suffer from delayed diagnosis, lack of effective screening programs and suboptimal therapeutic outcomes [3]. The disease is notorious for its insidious onset, rapid progression, and poor prognosis, with most patients presenting at an advanced and often metastatic stage [4].

The role of serum tumor markers in gallbladder cancer, particularly carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (Ca 19.9), has gained increasing attention over the past two decades. These markers, although non-specific, are frequently elevated in GBC and have been proposed as adjuncts for diagnosis, staging, and monitoring disease progression [5]. However, their true clinical value remains controversial, with limited prospective data validating their correlation with disease stage, especially at initial diagnosis. Some studies suggest that elevated levels of CEA and Ca 19.9 correlate with tumor burden and advanced disease, while others emphasize their limited utility due to overlap with benign hepatobiliary conditions and the confounding effect of obstructive jaundice [6–8]. Researchers also explored multi-marker panels and dynamic thresholds to improve diagnostic accuracy [9].

In the Indian context, where a large proportion of patients present with locally advanced or metastatic GBC, accessible and cost-effective prognostic tools are urgently needed. Serum markers offer a potential avenue for early triage and treatment intent decision-making, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Yet, there remains a paucity of robust, prospective, real-world data examining their diagnostic thresholds at the time of presentation.

This article presents a focused sub-analysis from a large-scale prospective observational study conducted at a high-volume tertiary cancer centre in North India. We aim to evaluate the diagnostic utility of serum CEA and Ca 19.9 as triage tools for predicting metastatic disease—specifically differentiating metastatic from local/locoregional disease. Using biomarker threshold stratification and real-world performance metrics, we investigate whether these tumor markers can reliably support clinical decision-making in the Indian GBC population.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at a high-volume tertiary referral cancer centre situated in the Gangetic belt of northern India. This institution serves a large catchment area encompassing eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, and adjoining regions which are recognized hotspots for GBC incidence. This study is part of a larger dissertation project investigating diagnostic, prognostic, and socioeconomic variables in GBC through a prospective cohort design. To preserve the analytical clarity and thematic integrity of each component, variables have been addressed in separate focused analyses. The current manuscript specifically evaluates the diagnostic role of serum CEA and Ca 19.9 in relation to disease stage at presentation. Attempting to analyze all collected variables within a single paper would have diluted the focus and potentially led to interpretative confusion.

Patients were recruited over a period from September 1, 2023, to May 18, 2024. A total of 1500 GBC patients, who were ≥ 18 years, were enrolled during this timeframe based on imaging and histopathology. All participants were newly diagnosed cases, either incidental or treatment-naïve, presenting to the outpatient department. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion.

Data was collected prospectively using structured case record forms and institutional electronic medical records. Serum CEA and Ca 19.9 were measured using chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA)–based platforms in institutional NABL-accredited laboratories. Biomarker values were collected at baseline prior to any form of cancer-directed therapy.

Diagnostic thresholds for elevated levels were calculated from the current dataset using the 75th percentile cutoff, stratified by obstructive jaundice (OJ) status to control for confounding due to biliary stasis. To evaluate the diagnostic performance of tumor markers for predicting metastatic disease at presentation, metrics such as precision, recall (sensitivity), specificity, accuracy, and positive predictive value (PPV) were derived using classification matrices. Diagnostic discrimination was further visualized using ROC and precision-recall curves, constructed at a threshold of 0.75.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of the institution with the IEC approval number 11000652 and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patient data were anonymized prior to analysis, and confidentiality was strictly maintained. The authors used OpenAI’s ChatGPT to assist in language refinement, grammar correction, and sentence structuring in this article. No content generation or interpretation of results was delegated to the tool.

Results

A total of 1500 newly diagnosed GBC patients were enrolled between September 2023 and May 2024. The median age at presentation was 55 years (range 18–94) with 68.9% females (n = 1034) and a female-to-male ratio of 2.22:1. At presentation, 1203 patients (80.2%) were diagnosed with metastatic disease and 297 patients (19.8%) had local or locoregional disease.

Among the 1409 patients with complete workup, 643 (45.6%) have OJ at presentation and 766 (54.4%) did not have OJ at presentation. Serum marker data were available for CEA in 1027 patients and Ca 19.9 in 1263 patients. Patients with metastatic disease demonstrated markedly higher serum marker levels compared to those with local/locoregional disease as shown in Table 1 and visualized in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Values of serum tumor markers

| Biomarker | Disease stage | Mean value | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEA | Metastatic | 288.45 ng/ml | 0.03–30,145 |

| CEA | Local/locoregional | 22.91 ng/ml | 0.36–1644 |

| Ca 19.9 | Metastatic | 20,916.95 U/ml | 1.03–1,000,000 |

| Ca 19.9 | Local/Locoregional | 2240.88 U/ml | 0.5–168,659 |

Fig. 1.

Box plot of Serum tumor markers

Using the 75th percentile values derived from the dataset and stratified by OJ status, the following diagnostic thresholds were defined:

CEA > 42.22 ng/mL and Ca 19.9 > 7,344.41 U/mL (if OJ present)

CEA > 50.05 ng/mL and Ca 19.9 > 1,642.49 U/mL (if OJ absent)

Applying these thresholds yielded the following confusion matrix results (Table 2) for predicting metastatic disease at diagnosis (n = 1011 with complete data):

Table 2.

Confusion matrix

| Predicted local | Predicted metastatic | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual local | 212 | 26 |

| Actual metastatic | 461 | 312 |

The diagnostic performance metrics are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance metrics of CEA and Ca 19.9 in predicting metastatic disease

| Accuracy | 51.8% |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity (recall) | 40.3% |

| Specificity | 89.1% |

| Positive predictive value (PPV) | 92.3% |

| F1 score (macro average) | 0.51 |

The diagnostic model demonstrated excellent specificity and PPV, indicating that patients exceeding threshold values were highly likely to have metastatic disease. However, sensitivity was limited, suggesting that normal marker values could not reliably rule out metastasis.

On applying the logistic regression model on the dataset with a threshold of 0.75, the ROC curve for the model confirmed moderate discriminative ability (AUC ~ 0.74) favoring use as a confirmatory rather than screening tool. The precision-recall curve highlighted the high precision in detecting metastatic disease when markers were above thresholds, particularly in a dataset with high metastatic prevalence (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Precision recall curve of CEA and Ca 19.9

Fig. 3.

Precision recall curve of CEA and Ca 19.9

Over 99% of patients in this cohort with available histopathology data were adenocarcinomas.

Discussion

The current sub-analysis offers valuable insight into the diagnostic utility of serum CEA and CA 19.9 in predicting metastatic GBC at initial presentation. CEA and CA 19.9 are glycoprotein epithelial antigens commonly overexpressed in adenocarcinomas, including GBC [10, 11]. Tumor burden and ductal obstruction enhance serum marker release, making them potential indirect indicators of metastatic progression [5, 12]. In high-burden, resource-limited settings like the Gangetic belt, where routine staging imaging may be delayed, tumor marker–driven triage offers a rapid low-cost adjunct for clinical decision-making within hours.

The box plot in Fig. 3 demonstrates a significant elevation in serum CEA among patients presenting with metastatic disease, compared to local/locoregional disease. Log-transformation was applied due to extreme positive skewness. The median CEA for metastatic cases was notably higher, with wide interquartile ranges reflecting tumor heterogeneity. Similarly, the distribution of Ca 19.9 also showed substantial elevation in metastatic patients. Some extreme values approached the assay detection ceiling (up to 1 million U/mL), justifying the log scale. Statistically, both CEA and Ca 19.9 values were significantly higher in metastatic disease (p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test).

Even among patients initially classified as non-metastatic, as evident from the confusion matrix, 26 patients showed extremely elevated serum markers. This subgroup may represent biologically aggressive tumors or harbor subclinical metastasis below the detection threshold of conventional imaging modalities. Their existence highlights the potential value of tumor markers not only in triage but also in prompting closer surveillance in borderline cases.

Our study, leveraging the 75th percentile derived biomarker thresholds from a cohort of more than 1000 patients, demonstrates that elevated tumor marker levels have high specificity (89.1%) and PPV (92.3%) for detecting metastasis. To determine clinically meaningful thresholds for serum CEA and Ca 19.9, we employed the 75th percentile values derived from our own prospective cohort dataset. This approach was selected to reflect the real-world distribution of tumor marker levels within our specific patient population, which is geographically and biologically distinct from Western cohorts. Given the known variability of these markers due to factors such as tumor burden and presence of obstructive jaundice, using internally derived percentile cut-offs allows for a context-sensitive and unbiased stratification [13]. Our dataset’s stratification by OJ status, therefore, addresses OJ as a confounder and supports the higher specificity observed. The 75th percentile, in particular, was chosen to identify the top quartile of patients with the highest marker levels, i.e., those most likely to harbor biologically aggressive or metastatic disease. By anchoring our diagnostic evaluation to a cohort-specific percentile, we ensured that the stratification was both statistically robust and clinically relevant to our target population.

For patients with OJ, CEA > 42.22 ng/mL and Ca 19.9 > 7344.41 U/mL were strongly associated with metastatic presentation, while in patients without OJ, thresholds of CEA > 50.05 ng/mL and Ca 19.9 > 1642.49 U/mL were similarly predictive. These stratified values outperformed traditional fixed cut-offs by accounting for the confounding effect of cholestasis on Ca 19.9 interpretation [14]. Figure 2 confirms the trade-off of high specificity and lower sensitivity, and Fig. 3 illustrates how precision changes with sensitivity in predicting metastatic disease. The high specificity and PPV demonstrate that if both markers are above the cutoff, there is a high chance that the cancer has already spread in 9 out of 10 patients. If both markers are below threshold, it requires correlation with imaging. This data set is excellent in “ruling in” metastasis but has limited ability to “rule out” metastasis.

In a retrospective paper published from India in 2020, the value of CA19-9 > 109 U/ml was taken to predict metastatic disease with a sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 47.4% [15]. Sachan et al. stated that Ca 19.9 value of more than 72 IU/ml and CEA value of more than 5 ng/ml had a sensitivity and specificity of 52 and 80 and 51 and 72%, respectively, for detection of metastatic disease [5]. This shows that our dataset has significantly improved diagnostic performance using population-adjusted percentiles. Koreans in their paper attempted to differentiate GBC from normal control and early stage GBC from advanced GBC with good specificity [16].

The uniqueness of our study lies in its large, prospectively collected cohort, a scale rarely achieved in existing literature on tumor marker stratification. Unlike previous studies that often apply arbitrary or Western-derived thresholds, we employed internally derived, percentile-based cut-offs for CEA and Ca 19.9, ensuring that the biomarker interpretation is biologically and geographically relevant to our patient population. Furthermore, our approach is distinguished by systematic stratification based on OJ status, a critical confounder in Ca 19.9 interpretation that has been inadequately addressed in earlier work. By tailoring the cut-offs separately for jaundiced and non-jaundiced patients, we achieved high diagnostic specificity and positive predictive value, marking our study as one of the few that provides context-sensitive and clinically actionable thresholds. To our knowledge, this is the first Indian study to rigorously evaluate biomarker thresholds for metastatic prediction in GBC using a percentile-based, jaundice-stratified model. This real-world, resource-sensitive framework can be particularly impactful in low- and middle-income settings where decision-making often depends on optimizing limited diagnostic modalities.

Ultrasonography of the abdomen remains a widely accessible first-line modality for evaluating gallbladder morphology, wall thickening, and mass lesions suggestive of malignancy [17, 18]. When combined with above cut-off values of serum CEA and Ca 19.9 levels, it will enhance the early prediction of metastatic disease, particularly in settings with limited access to cross-sectional imaging. We do not advocate using serum markers as substitutes for imaging or histopathology-based staging. Rather, our percentile-based threshold model offers a context-sensitive triage mechanism, particularly suited to high-burden regions with staging bottlenecks.

Our study has certain limitations. First, the diagnosis of metastatic disease was primarily based on imaging findings without routine histopathological confirmation in all cases, which may introduce misclassification bias. Second, Ca 19.9 levels can be influenced by factors other than tumor burden and jaundice, including subclinical cholestasis, inflammation, and level of jaundice, potentially affecting marker specificity despite jaundice stratification [19]. Third, while our cutoff values were statistically robust within our cohort, they may not be directly generalizable to other populations without external validation. Fourth, this study did not assess longitudinal marker trends or integrate other potential biomarkers such as CYFRA 21–1 or circulating tumor DNA which could further refine diagnostic accuracy [20, 21]. Lastly, this study did not integrate molecular profiling or histological subtypes beyond adenocarcinoma. Future prospective efforts may benefit from combining serum biomarker trends with tumor biology to refine the triage model further.

Conclusions

This study highlights that elevated levels of CEA and Ca 19.9, when interpreted through jaundice-adjusted thresholds, are strong indicators of metastatic GBC. Using a simple “both high” rule enhances the ability to detect advanced disease early, even before full staging is available. With an excellent PPV and a reliable ROC AUC, this approach offers a clinically meaningful, low-cost triage tool. It bridges rigorous statistical validation with real-world applicability, making it valuable for both oncologists and public health practitioners striving for timely cancer care.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

Study conception and design- MT, KV, SNS Formal analysis and investigations- KV, CK, AS, GSG, PKS and BK Writing original draft- KV Review and editing- MT Supervision- MT.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Department of Atomic Energy.

Data Availability

Data is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed on the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. IEC of MPMMCC and HBCH, Varanasi, India, approved this study for the thesis with study number: 11000652.

Consent to Participate

Informed written consent was taken from each participant on the consent form approved by IEC.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dutta U, Bush N, Kalsi D, Popli P, Kapoor VK. Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer in India. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(4):33. 10.21037/cco.2019.08.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afzal A, Liu YY, Noureen A, et al. Epidemiology of gall bladder cancer and its prevalence worldwide: a meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2025;20(1):143. 10.1186/s13023-025-03652-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu S, Xu M. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of gallbladder cancer: current status and future directions. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2025;17(5):104957. 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i5.104957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:99–109. Published 2014 Mar 7. 10.2147/CLEP.S37357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Sachan A, Saluja SS, Nekarakanti PK, et al. Raised CA19–9 and CEA have prognostic relevance in gallbladder carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):826. Published 2020 Aug 31. 10.1186/s12885-020-07334-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Wen Z, Si A, Yang J, et al. Elevation of CA19-9 and CEA is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with resectable gallbladder carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2017;19(11):951–6. 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang YF, Feng FL, Zhao XH, et al. Combined detection tumor markers for diagnosis and prognosis of gallbladder cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(14):4085–92. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin MS, Huang JX, Yu H. Elevated serum level of carbohydrate antigen 19–9 in benign biliary stricture diseases can reduce its value as a tumor marker. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(3):744–750. Published 2014 Mar 15. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Shukla VK, Gurubachan, Sharma D, Dixit VK, Usha. Diagnostic value of serum CA242, CA 19–9, CA 15–3 and CA 125 in patients with carcinoma of the gallbladder. Trop Gastroenterol. 2006;27(4):160–165. [PubMed]

- 10.Agrawal S, Gupta A, Gupta S, et al. Role of carbohydrate antigen 19–9, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 125 as the predictors of resectability and survival in the patients of carcinoma gall bladder. J Carcinog. 2020;19:4. 10.4103/jcar.JCar_10_20. (2020 Jun 27). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altshuler E, Richhart R, King W, et al. Importance of carbohydrate antigen (CA 19–9) and carcinoembrionic antigen (CEA) in the prognosis of patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma: a retrospective single-institution cohort study. Oncotarget. 2023;14(1):351–7. 10.18632/oncotarget.28406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyev A, Prakash LR, Chiang YJ, et al. Elevated CA 19–9 is associated with worse survival in patients with resected ampullary adenocarcinoma. Surg Oncol. 2023;51:101994. 10.1016/j.suronc.2023.101994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Greca G, Sofia M, Lombardo R, et al. Adjusting CA19-9 values to predict malignancy in obstructive jaundice: influence of bilirubin and C-reactive protein. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(31):4150–5. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mery CM, Duarte-Rojo A, Paz-Pineda F, Gómez E, Robles-Díaz G. Modifica la colestasis la utilidad clínica del CA 19–9 en cáncer pancreatobiliar? [Does cholestasis change the clinical usefulness of CA 19–9 in pacreatobiliary cancer?]. Rev Invest Clin. 2001;53(6):511–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar N, Rajput D, Gupta A, et al. Utility of triple tumor markers CA19-9, CA125 and CEA in predicting advanced stage of carcinoma gallbladder: a retrospective study. Int Surg J. 2020;7(8):2527. 10.18203/2349-2902.isj20203049. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang JS, Hong SY, Han Y, et al. Limits of serum carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 as the diagnosis of gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2021;101(5):266–73. 10.4174/astr.2021.101.5.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okaniwa S. How can we manage gallbladder lesions by transabdominal ultrasound? Diagnostics. 2021;11(5):784. 10.3390/diagnostics11050784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Sarangi Y, Gupta A, Sharma A. Gallbladder cancer: progress in the Indian subcontinent. World J Clin Oncol. 2024;15(6):695–716. 10.5306/wjco.v15.i6.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wannhoff A, Rupp C, Friedrich K, et al. Inflammation but not biliary obstruction is associated with carbohydrate antigen 19–9 levels in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(13):2372–9. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang L, Chen W, Liang P, et al. Serum CYFRA 21–1 in biliary tract cancers: a reliable biomarker for gallbladder carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(5):1273–83. 10.1007/s10620-014-3472-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García P, Lamarca A, Díaz J, Carrera E, Roa JC, On Behalf Of The European-Latin American Escalon Consortium. Current and new biomarkers for early detection, prognostic stratification, and management of gallbladder cancer patients. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(12):3670. 10.3390/cancers12123670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.