Summary

Antibody dynamics models are analytical frameworks that probabilistically link changes in antibody titer timeseries to exposures. To date, antibody dynamics models have not been applied to SARS-CoV-2 datasets and have not incorporated observed exposures (i.e., from vaccination and positive PCR results) directly in their inference. We developed a bespoke framework that incorporates these features and applied it to data from the “Prospective Assessment of COVID-19 in a Community” (PACC) cohort. We used ELISA to measure serum antibody levels against Wuhan-1 spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins and inferred the level of protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection each antigen provided at different titers (protection curves). The S protection curve shifted when the Omicron lineage evolved, indicating that higher Wuhan-1 titers were required for protection. Age and exposure history did not shift the protection curves. This work highlights the utility of antibody dynamics frameworks to inform SARS-CoV-2 vaccination strategies.

Subject areas: Health sciences, Medicine, Medical specialty, Immunology, Public health

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 infections inferred from cohort data using an antibody dynamics model

-

•

Model incorporates PCR+ confirmed infections and vaccinations during inference

-

•

Inferred the antibody titers associated with different degrees of protection

-

•

Protection curves shifted when the Omicron lineage evolved

Health sciences; Medicine; Medical specialty; Immunology; Public health

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 epidemics pose complex challenges for public health management, vaccine strain selection, and the timing of vaccination programs.1,2,3 Effective public health strategies rely on understanding infection dynamics4 and determining the protection conferred by prior infection and vaccination.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Selecting experimental groups for protection studies in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic based on infection histories and vaccination status was straightforward. However, this became progressively difficult as widespread reinfection, evolution of antigenic variants, and vaccination made exposure histories increasingly complex. Simultaneously, an unprecedented quantity of serological data was generated; as of May 15 2025, SeroTracker lists 4,610 COVID-19 seroprevalence studies in 148 countries that include 37.8 million participants.12 Seroprevalence studies typically summarize population seroprevalence, vaccination, and infection rates but do not directly assess the impact of antibody levels on infection risk.

Antibody responses to primary COVID-19 vaccination vary with age5 and correlate with protection from infection. However, little attention has been paid to whether a given antibody titer confers the same protection in different age groups. Furthermore, many studies identified SARS-CoV-2 correlates of protection but fewer quantify protection curves,6,7,8,9,11 which estimate the probability of protection from infection following an exposure at different antibody levels. Although it is known that mRNA vaccines produce higher antibody titers than natural infections,13 it is unknown whether the shapes of protection curves derived from vaccination and natural infections are the same.

Detailed understanding of infection and antibody dynamics in observational cohorts are possible by using models that link processes that produce the data (e.g., infection, antibody production, and antibody waning) to observed data. Such antibody dynamics models have been frequently applied to influenza and dengue14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 but to date have not been applied to SARS-CoV-2. They also typically do not incorporate known exposures from vaccinations and positive PCR tests. Here, we close this gap with a bespoke multi-antigen Bayesian antibody dynamics model package, abdpymc.

We use abdpymc to infer infection histories and monthly spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) antibody timeseries for individuals in the Prospective Assessment of COVID-19 in a Community (PACC) cohort. PACC is a rural community based, observational cohort of 1,520 individuals in Wisconsin, USA with a high vaccination rate of 82%.23 Blood draws were conducted from November 2020 to July 2022 and were used to measure S and N reactivity. Vaccination records were accessed, and symptom surveys were conducted that could trigger additional serum sampling and PCR testing. Detailed seroprevalence analyses based on 1:40 ELISA optical density (OD) measurements revealed that 65% of the cohort had at least one SARS-CoV-2 infection by July 2022 and that by the end of the study 98% of the cohort were seropositive to either S or N.23 In the present study, we analyzed an additional ∼31,000 ELISA OD measurements taken at a range of serum dilutions to measure S and N EC50 titers and then used abdpymc to infer when infections occurred based on titer changes. This allowed us to then infer the impact of an individual’s S and N antibody titers on their protection from infection during the study while accounting for vaccinations and known (PCR+ associated) infections from observational cohort data.

We validated abdpymc by (1) conducting a simulation study, (2) using reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) confirmed infections as positive controls and (3) comparing summary statistics to other studies. We then used abdpymc to reconstruct infection histories and antibody timeseries for each individual and estimated protection curves, i.e., the relationship between ELISA S and N antibody titers and risk of infection during the study period. Omicron B.1.1.52924 evolved during the study24 which allowed us to measure the impact of the emergence of an antigenically novel lineage, and its sublineages, on the association between ELISA titer and risk of infection. Finally, we tested for differences in protection curves in different age groups and for different types of exposure histories (vaccination, infection, and a combination of vaccination and infection).

Complex exposure histories make it challenging to identify distinct experimental groups in cohorts. Simultaneously, it is beneficial to incorporate as much additional information as possible from vaccination and PCR+ records to improve inference. This work and the antibody dynamics model we developed serves as a proof of principle in the ability to predict antibody mediated protection from observational cohort data.

Results

Overview of abdpymc

We developed a Bayesian framework to probabilistically infer when individuals were infected based on changes in S and N ELISA titers, while accounting for expected changes due to vaccination and PCR confirmed infections. Time was discretized into calendar months and spanned from six months before the first blood draw to the final blood draw (May 2020–November 2022 inclusive). The model is split into exposure, antibody timeseries and measurement components, and parameters are inferred jointly in all components simultaneously (Figure 1). The exposure component deals with how PCR+ records and infections that get inferred probabilistically (henceforth “inferred infections”) are treated. The antibody timeseries component describes how exposures impact antibody titers through time, given antibody dynamics parameters. Finally, the measurement component describes how ELISA OD readings are converted to ELISA titers. The model is described completely in the STAR Methods; here follows a high-level description outlining the main features.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of antibody dynamics model

(A) Overview of how exposures and antibody kinetics parameters influence an individual’s ELISA titer, and how the ELISA titer and sigmoid parameters influence ELISA optical density (OD). Observed and unobserved nodes are shaded and unshaded respectively. Indexes indicate what a datum was measured on, or a variable is inferred for. For example, “i,t,x,g” means that a single ELISA OD datum relates to a specific individual (i), time (t), sample dilution (x), and antigen (g), whereas “g” means that sigmoid parameters are inferred for each antigen.

(B) Schematic showing how antibody kinetics parameters influence a titer timeseries. α determines the initial baseline titer, φ is a permanent response added to the baseline after a first exposure, θ is a temporary response that wanes after each exposure and ρ is the monthly waning rate of each temporary response.

(C) A four-parameter sigmoid curve is used to model an ELISA titer given ELISA OD measurements at different sample dilutions. a defines the x-location of the curve (and is the ELISA titer), b is the slope of the curve, c sets the baseline OD, and d determines the maximum OD. b and d are inferred separately for each antigen; a is inferred for each sample, and c is set to zero.

The exposure component controls how PCR+ records and inferred infections are represented. Infections were modeled as binary parameters and were constrained such that: (1) individuals were allowed a single infection during each period that a major antigenic variant circulated; (2) PCR+ records took precedence over inferred infections in any period (because they remove infection timing uncertainty); and (3) inferred infections were not allowed to occur within three months of a prior infection. The antibody timeseries component determines how antibody titers change after infection and vaccination. Infections impact both N and S titers, whereas vaccination impacts only S titers. Titers rise by a permanent amount (Φ, Figure 1B) after a first exposure. Every exposure also generates a temporary response (Θ, Figure 1B) that wanes by a proportion, ρ, each month. More complicated formulations, such as permanent components for secondary exposures21 or biphasic responses25,26,27,28 would have been unlikely to be identifiable with the data in this study. To account for expected higher post-vaccination responses relative to natural infection,13,29,30 two Θ values are estimated for S, one for infections and one for vaccinations. Finally, in the measurement component, titers are inferred by fitting sigmoid curves to ELISA OD readings at different log dilutions. ELISA titers are the estimated serum dilution at which OD drops to half its maximal value in a standardized assay and measure the amount of antibody binding to a target antigen. An in-house ELISA assay was used,31 see STAR Methods for details.

abdpymc accurately infers infection histories and antibody timeseries parameters from simulated data

We generated data from a simulated cohort to evaluate model performance in a setting where inferences could be compared to known parameters and infections (Figure 2). Simulated data matched actual PACC cohort data as thoroughly as possible in order to test performance in the context of the idiosyncrasies of the PACC cohort data, rather than from ideal data with, say, more intense sampling, no measurement error or more individuals. Accordingly, the simulation contained one individual for every cohort participant with matching PCR+ records, vaccination history, blood draws, and dilutions measured for each sample.

Figure 2.

Validation of antibody dynamics model

(A) Monthly non-PCR+ associated infections in the simulation (blue), whose base rate is determined by scaled wastewater data (black). The number of monthly PCR confirmed infections in the PACC cohort (orange) is shown for comparison.

(B) Comparison of true parameter values to values inferred from simulated data. ɑ, Φ, ϴ, and ρ are the baseline, permanent response, temporary response, and waning parameters in the antibody timeseries framework component. Each of these parameters has a separate value for each antigen (N and S subscripts). ϴ is estimated separately for infections and vaccinations for the S antigen (inf and vac subscripts). b, d, and σ are the slope, difference between maximum and minimum OD, and standard deviation of the ELISA OD sigmoid function. Error lines for inferred parameters show 95% posterior credible intervals.

(C) Inferred infection probability around known infections in simulated data. Inferred infection probabilities shown here were inferred by running abdpymc on simulated serological data. Known infections can occur in any month, but in this visualization timeseries were aligned such that known infections occur in the center. Individual gray lines show infection probability around a single known infection. The solid black line shows the mean probability of infection surrounding all known infections, and the dashed line shows the cumulative mean.

(D) Like (C), except here abdpymc was run on serological data from the actual cohort but excluding PCR+ records. In this visualization known PCR+ records are treated like known infections in (C), so individual, mean, and cumulative infection probabilities relative to a PCR+ test are shown.

We also matched the monthly simulated attack rates to empirical data from the cohort. Firstly, actual PCR+ data were used in the simulation. Secondly, non-PCR+ associated infections were simulated using a baseline attack rate and hypothetical protection curves that quantified the probability of infection at different antibody titers given an attack. Monthly levels of SARS-CoV-2 detected in wastewater32 in Wisconsin, USA (the location of the PACC cohort) were scaled to generate a monthly attack rate that produced a similar ratio of PCR+ associated infections to non-PCR+ associated infections reported in other studies33,34 (Figure 2A).

We visualized the accuracy of infections inferred in the simulated data by plotting the posterior mean infection probability five months before and after each known infection (Figure 2C). Infection probability peaked at the known infection and one month prior and declines symmetrically around the peak, indicating that infections are inferred accurately but with some uncertainty. Such precision is expected given the serum sampling intensity (mean time between consecutive blood draws in the cohort was 117 days). Cumulative posterior mean infection probability in the same window (five months before and after each known infection) was 0.74 indicating that the antibody dynamics inference strongly captures most ground truth infections.

Ground truth values fell in the 95% posterior credible interval for all parameters except αN, αS, ΦN, and ΦS which control the initial (α) and permanent (Φ) N and S responses. For each antigen, errors in α and Φ cancel out; the difference between the posterior mean and true values of αN and ΦN are 0.20 and −0.19, respectively, and of αN and ΦN are 0.27 and −0.26, respectively. Therefore, although titers are modeled faithfully, the values of these titer components may not be inferred accurately. Ground truth titers and inferred titers for S and N were consistent (r = 0.63 and 0.62 for S and N, respectively, Figure S1). Correlations improved when restricting to time points at which blood draws were taken (r = 0.99 and 0.99 for S and N respectively, Figure S2).

abdpymc captures infections associated with PCR+ records

Although care was taken to match the simulation to the actual cohort as thoroughly as possible, no simulation is perfect. Fortunately, the PACC cohort provided an opportunity to test abdpymc using true data by treating PCR+ records as a positive control. We tested how well PCR+ associated infections were inferred after having removed PCR+ records from the data. Similarly to the simulation, abdpymc inferred PCR+ associated infections accurately (Figure 2D); mean infection probability peaked one month after the known infection and then declined rapidly. A one-month lag between an acute infection and detection of increased antibody titer is consistent with the time it takes to develop antibody responses after infection.35,36 Furthermore, 86.1% of PCR+ confirmed infections are inferred from antibody titer changes five months before or after they are known to have occurred.

Constraining the number of infections per period

Before applying abdpymc to PACC cohort data, we tested the legitimacy of restricting individuals to one infection during each period that a major antigenic variant circulated. The study was split into two periods, before and after the predominance of the Omicron variant and its sublineages in the study area (“pre-Omicron”: May 2020–December 2021, “Omicron”: January 2022–November 2022). In the pre-Omicron and Omicron periods only two and six individuals respectively (0.13% and 0.40% of the cohort) had multiple PCR+ records at least six months apart. With unrestricted infections, unrealistically many infections get inferred for many individuals (data not shown). Given the rarity of multiple PCR+ records in the same period, individuals were only allowed a single infection in each of these periods.

Merging proximate vaccination and PCR+ events

Vaccination and PCR+ data were independently preprocessed to remove events occurring within three months of each other. This was done for multiple reasons: (1) vaccinations occurring within three months of each other always consisted of the two components of a prime-boost vaccination series, (2) multiple PCR+ records in quick succession are often caused by single infections, and (3) mean duration between consecutive blood draws was 117 days (3.8 months), meaning we would generally be unable to differentiate independent exposures occurring within a shorter time span.

abdpymc infers exposure histories taking account of vaccination and PCR records for multiple antigens

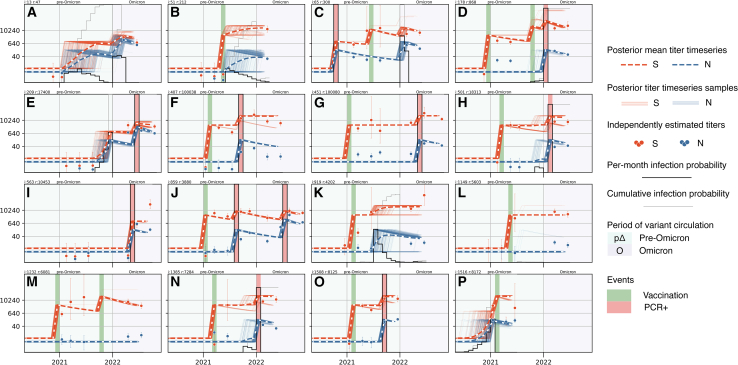

Having validated abdpymc on simulated data, using PCR+ records as positive controls, checking the validity of constraining the number of infections per period, and merging proximate vaccination and PCR+ events, we finally applied abdpymc to PACC cohort data. To illustrate examples of the types of infection dynamics that can be captured, antibody timeseries for 16 individuals selected randomly are shown in Figure 3 (timeseries of all 1,520 individuals in the cohort are available as supplemental data; data-S1.zip). Individual timeseries demonstrate the diverse vaccination and PCR+ histories abdpymc captures exemplified by individuals with: a single vaccination (Figures 3B, 3K, 3L, and 3P); a single PCR+ record (Figures 3E and 3I); PCR+ followed by vaccination (Figure 3C); vaccination followed by PCR+ (Figures 3F–3H, 3N, and 3O); two vaccinations (Figure 3M); two vaccinations followed by PCR+ (Figure 3D) and vaccination followed by two PCR+ (Figure 3J). Inferred infections can occur alone (Figure 3A) or be interspersed with known vaccination and PCR+ events, for example, after vaccination (Figures 3B and 3K), after PCR+ and vaccination (Figure 3C), before PCR+ (Figure 3E), and before vaccination (Figure 3P).

Figure 3.

Antibody trajectories capture diverse dynamics

(A–P) Antibody dynamics timeseries for 16 randomly selected individuals (equivalent plots for all 1,520 individuals in the PACC cohort are available as supplemental data). The horizontal axis displays time (May 2020–July 2022); the vertical axis displays S (orange) and N (blue) ELISA titers. Pre-Omicron and Omicron periods are displayed by light green and purple background colors, respectively. Heavy dashed lines show posterior mean S and N ELISA titer timeseries; thin lines show 250 posterior samples. Circles indicate ELISA titers inferred independently of the antibody dynamics model, error bars show 95% posterior credible intervals. Monthly infection probability is shown by the black stepped line; the bottom and top of each subplot corresponds to a probability of 0 and 1, respectively. A light gray line shows the cumulative infection probability in two intervals: May 2020–December 2021 (pre-Omicron) and January 2022–July 2022 (Omicron). Vaccinations and PCR+ confirmed infections are shown by dark green and red bars, respectively. Timeseries for all 1,520 individuals in the study are available as supplemental data: Data S1.

It is possible to be confident in the occurrence of inferred infections, yet uncertain in their precise timing. This is captured by low infection probability in any individual month but a high cumulative infection probability over a longer period (Figures 3A and 3B, year 2021). The timing of inferred infections can also be captured precisely (Figure 3C) or somewhere between these two extremes (Figures 3K and 3P).

Individuals show variation in antibody response and waning to COVID-19 vaccination and infection.37,38,39 Some PACC cohort individuals with high S responses had no detectable S waning (Figure S3). This was accommodated by assigning individuals a parameter, ω, that determined if S waning is observed in their data. Lack of measurable S waning in some individuals may be caused by such high responses that even after waning titers exceeded the measurement threshold.

Additional results corroborate existing studies and provide further validation. Similar to previous studies,13,29,30 we find S responses are higher after vaccination than infection (posterior mean temporary infection and vaccination parameters were 1.42 and 2.36, respectively). In addition, the proportion of inferred infections (i.e., that were not PCR+ associated) was 51.10%, which is similar to the rate of asymptomatic infections estimated in a 2020 metastudy.34 Lastly, time dependent S and N titers correlate well with time independent titers estimated from samples independently from the antibody dynamics framework (Figure S4, r = 0.82 and 0.82 for S and N, respectively).

S protection curve shifted right when the Omicron variant emerged

We used posterior mean infection probabilities and S and N ELISA titers to estimate the effect of S and N ELISA titers on protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection during the study period. Wuhan-1-like N and S proteins were used in all ELISA assays (see STAR Methods for details). We used a modified Cox-proportional hazards model that used S and N ELISA titers in the previous month to predict infection risk. ELISA S and N titers were linked to infection risk by a sigmoid function parameterized by a 50% protective titer and slope; baseline attack rate is estimated simultaneously. The model was run separately on the pre-Omicron and Omicron periods. Infected individuals are removed from further analysis during a given period. Importantly therefore, protection in the Omicron period is only assessed against pre-Omicron derived exposures and not a mixture of pre-Omicron and Omicron exposures which ELISA assays would not discriminate.

Protection from infection (one minus the Cox proportional hazards risk) is plotted against S and N ELISA titer as protection curves (Figure 4). During the pre-Omicron period an S ELISA titer of 40 yielded a posterior protection rate of 0.59 (0.44, 0.73; 95% credible interval), which rose to 0.94 (0.84, 1.00) at a titer of 10,240 (Figure 4A). The S protection curve shifted right during the Omicron period such that higher titers were required to achieve the same protection (Figure 4B). Differences to pre-Omicron protection are most notable at higher titers. Titers of 40 and 10,240 have estimated protective rates of 0.46 (0.34, 0.56) and 0.79 (0.72, 0.87), respectively. These changes are consistent with Omicron lineages being major antigenic variants relative to prior strains.40,41

Figure 4.

S and N protection curves

(A) Probability of protection from infection at different S antibody titers during the pre-Omicron and Omicron periods. Lines show posterior means, shaded regions show 94% posterior credible intervals.

(B) Probability of protection from infection at different N antibody titers during the Omicron period. Line shows posterior mean, shaded region shows the 94% posterior credible interval.

(C) Distribution of pre-infection S titers during the pre-Omicron period.

(D) Distribution of pre-infection N titers during the pre-Omicron period.

(E) Distribution of pre-infection S titers during the Omicron period.

(F) Distribution of pre-infection N titers during the Omicron period.

ELISA titer to N is not associated with protection from Omicron infection

The N protection curve during the Omicron period is notably flatter than the S protection curve during the same period (Figure 4B). Furthermore, its 95% credible interval contains 0.5 at all titers, consistent with infection risk being independent of N ELISA titer. It was not possible to estimate an N protection curve during the pre-Omicron period. Protection curve inference requires individuals with a range of pre-infection titers in order to test if differences in infection rate can be attributed to differences in titers. However, during the pre-Omicron period, all individuals had low pre-infection N ELISA titers, but variable S ELISA titers (log N and S titers ranged from −2.37 to 1.03 and −1.84 to 5.63, respectively, Figures 4C and 4D), caused by use of vaccines that contained only an S component. Infection was the only way for individuals to achieve an above baseline N titer, which precluded them from the Cox proportional hazards model. During the Omicron period, individuals had a range of S titers (due to vaccination and prior infection) and N titers (due to prior infection) enabling protection curves to be estimated for both antigens (Figures 4E and 4F).

Age and exposure history do not alter protection curves

We next tested if exposure history impacted protection curves. We grouped individuals based on whether they were (1) infected, (2) vaccinated, or (3) infected and vaccinated (hybrid) in the pre-Omicron period and then estimated Omicron period protection curves for each group. We found no substantial differences in the location and slope of protection curves among these groups (Figures S5A–S5C). Mean titer in the hybrid group was higher than in the other groups (consistent with other studies,42,43 Figures S5D–S5F) resulting in higher average protection in the hybrid group. Similarly, to test if there was any evidence that age affects protection curves, we grouped individuals based on their age in decades and inferred separate Omicron infection curves for each age group. We found no differences in 50% protective titers for individuals of different ages (Figure S6).

Inferring protection curves for S and N in isolation produces spurious association between N titer and protection

Inferring protection curves for S and N jointly (Figures 4A and 4B) controls for the effect of each antigen while inferring the effect of the other. To demonstrate this, protection curves for N and S were inferred for each antigen on their own (Figure S7). Misleadingly, the protective effect of N becomes stronger in the N alone model; the slope of the N protection curve has a posterior mean of −0.47 (−1.87, 0.15) in the N alone model but −0.09 (−0.27, 0.08) in the joint model (compare slopes of the curves in Figures 4B and S7B).

Discussion

We developed an antibody dynamics framework and measured changes in antibody-mediated protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection during the PACC cohort that occurred when the Omicron variant emerged. The shift in the S protection curve is consistent with the antigenic novelty of the Omicron lineages and the associated reduced effectiveness of prior immunity.23,44,45,46 Unlike existing frameworks, abdpymc infers undocumented infections in conjunction with known vaccinations and infections that are incorporated directly into unique exposure histories of each individual. The antibody dynamics framework reconstructs S and N antibody titer timeseries for each individual, while inferring unobserved infections and antibody kinetics parameters. Although it is impossible to determine the timing of infections with absolute confidence, the model provides a formal framework to capture uncertainty associated with infection timing and antibody responses. We validated the approach by accurately recovering known parameters from a simulation, recovering left out PCR+ confirmed infections, and observing similar rates of asymptomatic infections to previous studies.

A seroprevalence study using PACC cohort data demonstrated that 65% of individuals had evidence of at least one SARS-CoV-2 infection before the study ended in July 2022 and that SARS-CoV-2 incidence was substantially higher during a period of Omicron circulation compared to previous periods.47 These findings were based on ELISA OD readings on single serum dilution of 1:40. Here, we use 19,750 additional ELISA OD readings measured at different serum dilutions to infer ELISA titers. The additional measurements allowed us to quantify antibody levels more precisely and enabled us to robustly detect infections in individuals that were already seropositive, infer rates of S and N waning, and measure the association between S and N antibody titers with protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection during the study.

An estimated 51% of infections were not associated with a PCR+ record. PCR testing was conducted when participants reported any new onset of respiratory illness; therefore, this proportion reflects a combination of the asymptomatic infection rate, participants failing to report new illness and late PCR specimen collection resulting in missed positive results. A 2020 metastudy estimated a SARS-CoV-2 asymptomatic infection rate of 40%–45%34 which is broadly consistent with the proportion of non-PCR+ associated infections we observe. Asymptomatic infections in that metastudy were first exposures whereas many infections in PACC occurred against existing prior immunity. It is interesting to speculate whether greater prior immunity increased the rate of asymptomatic infections in the present study relative to the 2020 metastudy estimate. This speculation is supported by the observation that reinfections are more likely to cause mild illness and have a reduced risk of severe illness.48 In addition, the evolution of variants with lower virulence, in particular Omicron,49 may have increased rates of asymptomatic infection.

The antibody dynamics framework implemented in the abdpymc python package is innovative in several ways. To our knowledge, vaccination exposures have not been accounted for during inference in existing antibody dynamics frameworks. Existing frameworks have to be run separately for different exposure types, or the posterior distribution has to be stratified into vaccinated vs. unvaccinated groups.20 Similarly, to our knowledge, PCR confirmed infections have not been integrated during inference of existing frameworks. Doing so removes uncertainty about the occurrence of a subset of infections and makes use of all available data in a unified analytic framework. Having known infections likely aids inference of antibody kinetics parameters by introducing fixed infections that antibody kinetics parameters must accommodate. Advances in Bayesian inference libraries allowed us to code this model using off-the-shelf distributions and samplers.50 Unlike existing antibody dynamics frameworks, which incorporate infections using a reversible jump MCMC mechanism,21 here infections are treated as regular parameters which simplified the implementation.

Limitations of the study

Use of ELISA, rather than a more resource intensive neutralization assay, allowed us to measure antibody responses of all 7,294 serum samples in the study. However, care must be taken while interpreting ELISA titers as a correlate of protection because they measure antibody binding, not neutralization capacity. To highlight this, we tested sera from individuals infected by Wuhan-1 or Delta strains in ELISA assays using Wuhan-1, Delta, and Omicron S proteins and found that ELISA titers did not differentiate these variants (Figure S8). This seems to contradict the observation that the ELISA S protein protection curve shifted when the Omicron antigenic variant emerged (Figure 4A). We hypothesize that antigenic uniformity of pre-Omicron strains accounts for this apparent discrepancy. Individuals exposed to Omicron for the first time would only ever have been exposed to a pre-Omicron strain, which were relatively antigenic uniform.40 Furthermore, Wuhan-1 S ELISA titers of sera from individuals with pre-Omicron exposures correlate well with neutralization titers (r = 0.81, Figure S9). Therefore, S ELISA titer was a suitable surrogate of neutralization capacity in individuals only ever exposed to a pre-Omicron strain. Critically therefore, the protection curves we infer are only applicable during the time frame of this study. Notably, the antibody dynamics model we present here is not restricted to ELISA data and could be applied to neutralization-based assays in the future.

A major simplifying assumption was to effectively treat all strains that circulated within each of the pre-Omicron and Omicron periods as antigenically equivalent. However, it is well established that there is measurable antigenic variation within B.1-like viruses,51,52,53,54 that the original Omicron BA.1 lineage was a major antigenic variant,55,56,57,58,59 and that antigenic variation within Omicron sublineages is greater than that between original BA.1 viruses and B.1-like viruses.40,41,55 This assumption manifests itself in our analyses in two ways. Firstly, individuals were restricted to a single infection within each period. While re-infection was rare among B.1-like viruses,60 it was more common among Omicron sublineages, and cross protection between Omicron viruses was only high between relatively similar strains.61,62 In the PACC cohort specifically, we observe low rates of individuals with multiple positive PCR records within a period, suggesting that repeat Omicron infections were rare. Secondly, as discussed previously, the ELISA used is not able to distinguish antigenic variants. Therefore, the protection curve analysis depends on the antigenic uniformity of BA.1 viruses and that individuals infected during the Omicron period are, by definition, removed from the survival analysis. This limitation means that interpretation of the ELISA protection curves should be restricted to the time frame of the study.

We inferred the protective effect of both S and N proteins simultaneously and demonstrate notable, expected, differences in the protection either protein mediates. Given that most protection studies were designed to test vaccine efficacy, and that most vaccines target the S protein,63 most protection studies have appropriately focused on S-mediated protection. S mRNA vaccines show strong correlation between efficacy and the levels of neutralizing antibodies they elicit,8 and given that ELISA and neutralization titers correlate well for individuals with pre-Omicron exposures (Figure S9), the protection curve we infer matches expectations.

We have presented an antibody dynamics framework that is innovative in that it directly integrates the effects of vaccination and PCR+ confirmed infections during inference. We applied this to data from the well-characterized PACC cohort to measure the roles that antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 S and N proteins made to protection while also testing the impact of age and infection history. We measured the shift in the S protection curve caused by the emergence of the Omicron antigenic variant, demonstrating the utility of antibody dynamics models to uncover important epidemiological insights from uncontrolled observational data.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Gabriele Neumann (gabriele.neumann@wisc.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

De-identified data, scripts, and ipython notebooks that were used to run all analyses have been deposited at Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/r7675pg8hf.1.

-

•

Code for fitting the antibody dynamics model used in this study and conducting downstream analysis was written in a python package called abdpymc and is publicly available. The package is available to install via “pip install abdpymc” and the version used in this study (1.0.3) has been deposited at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16813218.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants in the PACC cohort for their involvement in this study and all other individuals at the Influenza Research Institute and Marshfield Clinic Research Institute who made this study possible. This work was supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (contract: 75D30120C09259) and in part through philanthropic support of medical research through Marshfield Clinic Health System Foundation (406030-00).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, D.J.P., J.G.P., J.P.K., E.A.B., H.Q.N., Y.K., and G.N.; methodology, D.J.P. and G.N.; software, D.J.P.; validation, D.J.P.; formal analysis, D.J.P.; investigation, D.J.P., P.J., and L.G.; resources, J.P.K., P.H., E.A.B., and H.Q.N.; data curation, D.J.P.; writing – original draft, D.J.P.; writing – review and editing, D.J.P., J.G.P., P.J., E.A.B., H.Q.N., Y.K., and G.N.; visualization, D.J.P.; supervision, Y.K. and G.N.; project administration, J.G.P., J.P.K., H.Q.N., Y.K., and G.N.; funding acquisition, H.N., Y.K., and G.N.

Declaration of interests

J.G.P., J.P.K., E.A.B., and H.Q.N. receive research support from ModernaTX. H.Q.N. participates in a scientific consultancy group for ModernaTX. Y.K. has received grant support from Daiichi Sankyo Pharmaceutical, Toyama Chemical, Tauns Laboratories, Shionogi, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, KM Biologics, Kyoritsu Seiyaku, Shinya Corporation and Fuji Rebio. Y.K. and G.N. are co-founders of FluGen.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-human IgG-Peroxidase antibody produced in goat | Sera Care-KPL | #5220-0277 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| SARS-CoV-2/UT-HP095-1N/Human/2020/Tokyo | Imai et al.64 | GenBank: PQ571724 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein | Sino Biological | 40588-V08B |

| Wuhan-1 like SARS-CoV-2 full length spike protein | This paper | 10222020-S |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) SARS-CoV-2 full length spike protein | This paper | 08172021-S |

| Omicron (B.1.1.529) SARS-CoV-2 full length spike protein | This paper | 01112022-S |

| Deposited data | ||

| ELISA OD measurements | This paper | Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/r7675pg8hf.1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| abdpymc python module | This paper | Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16813218 |

Experimental model and study participant details

Human participants

PACC cohort description

The Prospective Assessment of COVID-19 in a Community (PACC) is a longitudinal prospective cohort study initiated with individuals recruited from the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area – Central (MESA).65 MESA is a population cohort served primarily by the Marshfield Clinic Health System (MCHS) that includes approximately 50,000 residents living within approximately 1,300 square miles surrounding Marshfield, Wisconsin, USA. MESA offers electronic health record (EHR) data for institutional review board (IRB)-approved research purposes.

For the PACC study, individuals were randomly selected from MESA using 10-year age groups, with an oversampling of younger children and older adults.47 Individuals residing in institutional or group settings, that intended to move out of the MESA study area during the PACC study, or that participated in clinical trials evaluating investigational COVID-19 vaccines or therapeutics were excluded.

PACC participants provided information on demographic factors such as age, sex, and race/ethnicity at enrollment and during periodic surveys. COVID-19 vaccine records were obtained through MCHS EHR data, the Wisconsin Immunization Registry, and self-report. Age and sex distributions of PACC participants are shown in Table S2.

Consent statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute. Participants, or parents of minor participants, provided informed consent prior to participation. Participating children ≥7 years also provided assent for participation.

Method details

Serum sample collection

Blood samples were collected during scheduled sampling, following suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection and following a subset of vaccinations.

Scheduled sampling

Phase 1: a serum sample was obtained from each participant at enrollment (November 2020 – March 2021), and approximately 12 weeks (January – June 2021) and 24 weeks (April – September 2021) later. Phase 2: a fourth serum sample was obtained from each participant beginning in February 2022 (February – May), and a fifth was collected roughly 12 weeks later (May – July 2022).

Following suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection

Routine surveillance: Study participants were asked to report any new acute respiratory illnesses symptoms (cough, fever, chills, sore throat, muscle or body aches, loss of smell or taste, shortness of breath, diarrhea). Participants completed weekly surveys that recorded these symptoms for the previous week. Those reporting a new onset of acute respiratory illnesses within the past week self-collected nasal swabs to test for SARS-CoV-2.

Enhanced surveillance: A subset of participants underwent weekly testing from enrollment through August 2021 and from February to July 2022 which involved collecting a nasal swab every week regardless of symptoms.47

Nasal swabs from routine and enhanced study surveillance were tested for SARS-CoV-2 via RT-PCR. The MCHS EHR was also searched for positive test results conducted outside the study. Participants were required to report positive SARS-CoV-2 tests conducted outside the study during enrollment, 26- and 52-weeks post-enrollment, and weekly starting from February 2022. Those reporting a positive outcome from an external test were asked to provide the month and year.

Participants confirmed to have contracted SARS-CoV-2 through RT-PCR testing had blood drawn 4- and 16-weeks post-infection. Select individuals who received COVID-19 vaccination had serum drawn 4 to 6 weeks after each dose. Post-infection and post-vaccination blood draws counted towards scheduled post-enrollment visits if obtained within 30 days of the scheduled date to minimize blood draws.

All samples collected during the PACC cohort were included in the present study regardless of the reason they were collected. For more details on serum sample collection during the PACC cohort see47.

ELISA assay

Dilution strategy

Measuring at multiple dilutions increase workload but enables more accurate inference of the EC50 titer; conversely a single dilution is usually sufficient to infer seropositivity but gives a less precise EC50 titer and is less work. Different sets of dilutions were conducted on samples during phase 1 (three blood draws between late 2020 to mid 2021) and 2 (two rounds of blood draws in early and mid-2022) as the proportion of seropositive individuals changed. During phase 1 (when most individuals were SARS-CoV-2 seronegative) samples were screened at a dilution of 1:40. The 1:40 OD was then used to classify the sample as seronegative or seropositive, and seropositive samples were subsequently measured at three dilutions. Seropositivity classification was based on bivariate logistic regression of N and S 1:40 OD readings with a dataset containing pre-pandemic negative samples and PCR+ convalescent samples.66 During phase 2 most individuals had had either a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 vaccination and were therefore samples immediately tested at three dilutions. 162 samples were measured at eight dilutions before we had validated the use of three.66 A summary of the dilutions used for all samples is shown in Table S1.

Antigens

Two antigens were used in ELISA against all sera in this study: SARS-CoV-2 N antigen was purchased from Sino Biological (catalog number: 40588-V08B). WA1 SARS-CoV-2 full-length spike protein (S1S2) was expressed in Expi293F cells and purified using TALON metal affinity resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the Krammer group protocol.31 The S1S2 construct included the ‘hexaproline’ stabilizing amino acid (AA) substitutions (F817P, A892P, A899P, A942P, K986P, V987P) which increased production yield while maintaining prefusion spike confirmation,67 the cleavage site RRAR (682-685) was replaced with GSAS, and AA15-1208 was followed by T4 foldon trimerization motif, 3C protease cleavage site, and hexa-histidine tag (AA1-14 is a signal peptide). S1S2 proteins of two additional variants were generated to test whether ELISA could detect differences between variants. Recombinant Delta B.1.617.2 and Omicron B.1.1.519 strains were generated in the same manner as described above.

ELISA protocol

96-well ELISA plates (Thermo Scientific #:14245153) were coated with antigen at 100 ng/well and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T) and 3% milk for 1 h at room temperature and washed. All washes were conducted three times with PBS-T. Sera were diluted 1:40 in PBS-T and 1% milk. 100 μl of serum was added to the ELISA plates and incubated for 2-4 h at room temperature. Anti-human IgG-Peroxidase antibody produced in goat (Sera Care-KPL #5220-0277), diluted 1:3,000 in PBS-T and 1% milk, was used as the secondary antibody. Plates were washed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 50 μl/well of diluted secondary antibody. Plates were washed, and then incubated with 100 μl OPD solution (SIGMAFAST™ OPD, Sigma-Aldrich #P9187) for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl 3 M HCl and the OD at 490 nm was recorded.

ELISA data pre-processing

At least two blank wells (PBS only) were run on each 96-well plate during ELISA measurement. The mean of the blank values on a plate was subtracted from other values on a plate to correct for background.

Inferring ELISA titers of seronegative samples from single dilutions

Although measuring OD at multiple dilutions generally improves inference of ELISA titers, we inferred them from single dilutions on a subset of seronegative serum samples. PACC sample collection occurred in two phases (November 2020 - September 2021 and February 2022 – July 2022). During the first phase seroprevalence was low, so all sera were screened at a single 1:40 dilution and seropositive sera were then measured at three dilutions (1:40, 1:640 and 1:10,240). During the second phase seroprevalence was high, so all sera were immediately measured at three dilutions. Therefore, due to our conditional workflow, only seronegative sera were measured at a single dilution.

We tested whether a single 1:40 dilution was sufficient to accurately infer titers for seronegative sera by censoring 1:640 and 1:10,240 OD measurements for a random subset of 250 sera that were measured at three dilutions and comparing them to titers that were inferred from uncensored data. At titers below 160, the correlation between titers inferred from a single 1:40 serum dilution and those inferred from uncensored data was excellent (r = 1.00 for S and N, Figure S10). The correlation is this good because at low titers the 1:40 serum dilution has the most power among the other dilutions to influence the inference.

Microneutralization assay

We conducted microneutralization (MN) assays on a sample of seropositive PACC cohort samples in order to compare MN and ELISA titers. MN assays were conducted on 162 randomly selected serum samples from the PACC cohort that were previously identified as seropositive in ELISA.66 SARS-CoV-2/UT-HP095-1N/Human/2020/Tokyo was used in the assay.

30,000 Vero E6 TMPRSS2 cells per well were seeded in 96-well flat-bottom plates and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Serum samples were thawed on ice for 30-40 minutes vortexed briefly. Two-fold serial dilutions of serum were made in calcium free 5% FBS-DMEM medium in 96-well sterile U-bottom plates. Equal volumes of virus diluent (100 pfu/60 μl) were added to each diluted serum samples. The virus/serum mixture was incubated at 37° C for 30 minutes and then added to 95% confluent Vero E6 TMPRSS2 cells. Cells were incubated at 37° C for three days and then cytopathic effects were observed by the eye under a microscope. The reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that induced at least a 50% reduction in the cytopathic effect (CPE) was considered the neutralizing antibody titer.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Notation

Normal and Gamma distributions with mean, , and standard deviation, , are denoted Normal and Gamma ; Beta is a Beta distribution with shape parameters and ; Bernoulli is a Bernoulli distribution with probability ; Exponential is an Exponential distribution with rate parameter . Invlogit is the inverse logistic function: . Log-titers are used throughout and were converted from sample dilutions using (we used 4-fold dilution series beginning at a dilution of 1:40).

Bayesian inference

Bayesian inference was used throughout this study. The No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS),67 implemented in PyMC,50 was used to sample posterior distributions of continuous parameters. Binary parameters were sampled using the Metropolis-within-Gibbs step method. In the main abdpymc run 64 chains each drew 125 posterior samples in parallel resulting in a total of 8,000 samples. R hat was less than or equal to 1.05 for all scalar parameters except for (the N waning factor), which had an R hat value of 1.07. No diverging samples were detected. For all other analyses 4,000 samples across four chains were sampled using NUTS.

Antibody dynamics model

Overview

The aim of this antibody dynamics framework is to probabilistically infer when individuals were infected based on changes in ELISA OD readings and estimate parameters describing expected changes in S and N ELISA EC50 titers following infection and vaccination. This framework also incorporates PCR+ confirmed infections and apparent low rates of spike waning. The framework can be divided into different components: (a) the exposure model determines how infections are inferred probabilistically, and how vaccination and PCR+ records are incorporated; (b) the antibody timeseries model controls how infection and vaccination impact S and N titers; and (c) the measurement model specifies how ELISA OD readings are used to infer EC50 titers and ultimately constrain inferences in the exposure and antibody timeseries model components.

Exposure model

Time was discretized into time steps of calendar months from May 2020 - November 2022 inclusive. At a higher-level, time was divided into two periods corresponding to before (May 2020 - December 2021) and after (January 2022 - November 2022) the predominance of the Omicron variant in the study area. Individuals were allowed a single infection in each time period (similar to other studies that constrain the total number of infections per individual21).

Vaccination, , and PCR+ records, , were encoded as arrays where values of 0 and 1 indicate the absence and presence of events (vaccination or positive PCR tests) during month for individual . and were preprocessed to remove events occurring within three months of each other for any individual. This was done for multiple reasons: firstly, vaccination events occurring within three months comprised the two components of prime-boost vaccination series, which we wanted to treat as a single event; secondly, individuals testing PCR positive in successive months is likely caused by a single infection; thirdly (and pragmatically), the average duration between consecutive blood draws for an individual in this cohort is 117 days, so we would be unable to distinguish the independent effects of multiple vaccinations or infections in quick succession.

An array of constrained infections, , was generated by manipulating raw inferred infections, , and incorporating PCR+ records. Like and , is a array where values of 0 and 1 encode the absence and presence of an infection at time for individual . Raw inferred infections were assigned the following prior:

given that we expect approximately one infection per individual, there are 31 months in the analysis and Beta has a mean value of .

Constrained infections were generated from raw infections via:

where consists of applying three processing steps in the following order for each individual:

If multiple infections occur during a period, the first takes precedence. Concretely, if multiple 1s occur in the first is kept, and the rest are converted to 0s. For example, would be become .

PCR+ records remove uncertainty about the occurrence and timing infections, so PCR+ records took precedence over inferred infections in a period. For example, raw infections, , and PCR+ records would become . Here, the PCR+ record takes precedence even though it occurs after the infection in . Multiple PCR+ records with a time period are allowed (but given the preprocessing of PCR+ data describe above, never occur within three months of another PCR+ record.)

Infections are prevented from occurring within three months of another infection. Given only single infections are allowed during a time period anyway, this only affects infections occurring in the first three months of a time period if there has been an infection in the last three months of the previous time period.

The output of is a array of constrained infections, , where individuals have at most one infection per time period, PCR+ records are included and take precedence, and at the boundaries between periods multiple infections do not occur within three months of each other.

Antibody timeseries model

This section describes how exposures (vaccination and infection) impact S and N antibody titers. The titer of each antigen, , for an individual is modelled as a length array, . is decomposed as the sum of baseline, , permanent, , and temporary, , responses:

The baseline response of antigen , , is a scalar that captures the titer measured for unexposed individuals. It is loosely expected to have a log titer equivalent to a titer of 2.5, and was therefore given the following prior:

Permanent responses for each individual are a length array, . Elements in are assigned the first month an individual is exposed and all subsequent months. should be a positive and is loosely expected to be approximately two log units, so was assigned the prior:

Temporary responses for each individual are a length array, . Temporary responses increase by infection, vaccination (for S) and decay exponentially. Infection at time causes to be added to . should be a positive value and is weakly expected to be slightly lower than the permanent response, so is assigned this prior:

Similarly, vaccination at time , causes to be added to . Given that the COVID-19 vaccines used by participants in the PACC cohort contain the S antigen, vaccination responses are not added to the N response. has the same prior as :

Temporary responses decrease by a fixed proportion each month:

where is a value between and is weakly expected to be close to :

Some individuals had undetectable levels of S waning. This was captured by assigning each individual a value of or , , with some unknown hyperprior :

and then assigning as:

such that when , , and when , . Then, was used in place of in equation for .

ELISA OD measurement model

The OD, , of a sample at log dilution, , is described by the following sigmoid curve and priors:

where:

-

•

is the inflection point of the sigmoid curve (it is the EC50 titer or ELISA titer).

-

•

determines the slope of the curve, OD decreases at high log dilution, so has a weakly informed negative value.

-

•

sets the minimum OD value, the OD of a blank ELISA well is subtracted from each plate, hence the minimum OD value is defined as 0.

-

•

is the difference between the minimum and maximum OD value, so is weakly informed to have a value around 2.

Finally, OD data, , is modelled as:

where captures the standard deviation of OD measurements for antigen .

Implementation

This framework was written in python and uses the No-U-Turn Sampler implemented in PyMC to draw posterior samples. It is installable via ’pip install abdpymc’ and kept in this GitHub repository: https://github.com/davipatti/abdpymc.

Validation analysis simulation

Similar data to that derived from the real cohort was simulated with known parameters and infections. The antibody dynamics framework was applied to the simulated data and the accuracy of the parameter estimates and infection inferences was assessed. Simulated data was intended to be as similar to that of the cohort data in as many ways as possible to test the validity of applying this antibody dynamics framework applied to the true data. 1,520 individuals (matching the real cohort) were simulated. Each true participant had a simulated version of themselves with matched blood draw timing, PCR+ records and vaccination history. The dilutions that were measured in ELISA for each sample was also matched.

Infection

Additional (i.e. non-PCR+ associated) infections were simulated using (a) a baseline attack rate and (b) protection curves that quantified the probability of infection at different antibody titers given an attack.

A monthly attack rate similar to the true cohort was estimated to test whether the sampling in the true cohort and antibody dynamics framework caused the accuracy of inferring infections to vary, even if the simulated attack rate didn’t precisely match the true cohort. Monthly measurements of SARS-CoV-2 detected in wastewater in Wisconsin, USA (the state in which the study population is located) were used to inform a monthly attack rate.34 Raw monthly wastewater values were divided by a value of 4,000 to generate a monthly attack rate. 4,000 was selected because in trials it generated a ratio of PCR+ associated infections to non-PCR+ associated infections of approximately 2.5 : 1 which is similar to the rate of asymptomatic infections that have been reported in other studies.34

Attacks were stochastically simulated for each individual in each month using the monthly attack rate. If an individual was attacked, their probability of infection was computed based on their antibody titers that month and protection curves. We used protection curves for each antigen of the form:

where:

-

•

is the slope of the protection curve.

-

•

is the 50% protective titer (the titer at which ).

-

•

is the individual’s titer that month.

Protection curves for both N and S were simulated. An individual was protected if the result of a Bernoulli trial using for either antigen was 1.

Antibody timeseries

Antibody responses were modelled using the equation for . S and N responses were decomposed into permanent and temporary components which were computed as described in the "Antibody dynamics model" section.

Antibody protection curves

We used a modified Cox’s proportional hazards model to infer the joint effect of S and N antibody titers on the probability of protection from infection. All monthly time steps from the antibody dynamics model were analyzed. Like in the antibody dynamics model, time steps were divided into two periods corresponding to before and after the predominance of the Omicron variant in the study area (May 2020 - December 2021 and January 2022 - November 2022).

The probability of infection in each month for each individual () was used as a probabilistic representation of when individuals were infected. Note that incorporates PCR+ data. Infections were limited to a maximum of one per period; for most individuals was used directly, however for individuals with multiple PCR+ records in a single period only the first PCR+ record was used. Antibody titer timeseries for each individual and antigen () were used to predictor risk of infection.

The antibody protection curve analysis was run as a separate inference step after inferring the posterior distributions of parameters from the main antibody dynamics model. The posterior mean of infections, , and antibody titers, were used as inputs to the antibody protection curve analysis.

The probability of protection from infection was predicted using S and N antibody titers of the previous month. The first interval of the first time period was excluded because there is no estimate of a prior antibody titer. The first interval of the second period used antibody titers from the last interval of the first period.

A degree of risk array, , was constructed for each time period which quantified the amount of risk of infection indiviudal experienced at time . For each individual this value decreases as their infection probability accumulates through the time period. for each individual is 1 minus the cumulative sum of posterior mean infection probabilities in all preceding time steps in the period:

An individual’s probability of protection in any month based on their antibody titers was calculated as:

where:

-

•

is a length 2 array of the posterior mean S and N antibody titers from the previous time interval

-

•

is a length 2 array of the S and N 50% protective titers, with priors

-

•

is a length 2 array of the gradient of the S and N protection curves, with priors

-

•

is the baseline attack rate at time , and captures the variable attack rate during the cohort in different intervals. Partial pooling across intervals in the period was implemented using the priors:

where weakly sets the expected baseline infection rate to be approximately 0.05 and invlogit transforms to the interval 0-1.

Finally, the risk of infection is modelled as:

Protection curves for antigens in isolation

The analysis was identical to that of the combined S and N analysis except that independent models were run separately for S and N and the 50% protective titer and slope parameters in the equation for were single values with the following weakly informed priors:

Prior exposure and age stratified analyses

We inferred protection curves for individuals with different prior exposures and in different age groups. Given that N ELISA titers are not correlated with protection from infection (Figure 4), and to simplify this analysis, we ran these analyses using only S data. Both the prior exposure and age stratified analyses were identical to that presented above, except that was a length array, where the th value was a 50% protective titer for each group. Concretely:

For the prior-exposure analysis three groups were identified based on exposures in the pre-Omicron time period:

-

•

Vaccinated only (n=614). Any individual that was vaccinated and had no inferred or PCR+ confirmed infection.

-

•

Infected only (n=229). Any individual that had either an inferred or PCR+ confirmed infection and that was unvaccinated.

-

•

Infected and vaccinated (n=387). Any individual that was both vaccinated and had either a PCR+ confirmed or inferred infection. The order of vaccination and infection was not considered.

For the age group analysis, individuals were grouped based on their age in decades at enrollment.

ELISA titers inferred from one vs three dilutions

Seronegative samples collected during Phase 1 of PACC were measured in ELISA at a single dilution of 1:40. We previously demonstrated that three dilutions (1:40, 1:640 and 1:10,240) are sufficient to infer ELISA EC50 titers in this cohort.66 We tested the accuracy of ELISA EC50 titers inferred from a single 1:40 dilution.

500 PACC samples that were measured at at least dilutions of 1:40, 1:640 and 1:10,240 were selected at random. ELISA titers were then inferred for these 500 samples in two separate analyses. In the first analysis all dilutions were kept for all samples. In the second analysis only the 1:40 dilution was used for a test group comprising a random selection of 250 samples. Titers of samples in the test group inferred using a single 1:40 dilution were then compared to those inferred using all three dilutions. This was conducted independently for the S and N antigens.

The following model was used:

where:

-

•

indexes sera.

-

•

indexes serum dilutions.

-

•

is the ELISA OD measured on serum at dilution j.

-

•

is the log dilution of serum i.

-

•

is the ELISA EC50 titer of serum i.

-

•

and capture the mean and standard deviation of the distribution of ELISA EC50 titers. The priors weakly express the expectation that these values will be positive.

-

•

is the slope of the sigmoid curve. The prior puts no strong expectation on its scale but forces the value to be negative given that it is known that OD values will tend to zero at high serum log dilutions.

-

•

is the maximum response of the ELISA OD reading. The prior is a weakly informed, positive value.

-

•

is the standard deviation of ELISA OD measurements. It’s prior is a weakly informed, positive value.

The comparison was conducted between test samples that retained different numbers of dilutions in the two analyses. The 250 samples that retained all three dilutions in both analyses play an important role in helping constrain posterior distributions of shared parameters slope and maximum response parameters ( and respectively), which consequently aids the inference of titers from single dilutions. This is similar to the usage of samples with different numbers of dilutions in the antibody dynamics model - inference of titers from samples measured at a single dilution is enabled by the presence of many other samples measured at multiple dilutions which inform posterior distributions of the shared slope and maximum response parameters.

Published: August 16, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.113386.

Contributor Information

David J. Pattinson, Email: david.pattinson@wisc.edu.

Gabriele Neumann, Email: gabriele.neumann@wisc.edu.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Markov P.V., Ghafari M., Beer M., Lythgoe K., Simmonds P., Stilianakis N.I., Katzourakis A. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023;21:361–379. doi: 10.1038/s41579-023-00878-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viana R., Moyo S., Amoako D.G., Tegally H., Scheepers C., Althaus C.L., Anyaneji U.J., Bester P.A., Boni M.F., Chand M., et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Om icron variant in southern Africa. Nature. 2022;603:679–686. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monto A.S., Lauring A.S., Martin E.T. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine strain selection: guidance from influenza. J. Infect. Dis. 2022;227:4–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang L., Wang Z., Wang L., Vrancken B., Wang R., Wei Y., Rader B., Wu C.-H., Chen Y., Wu P., et al. Association of vaccination, international travel, public health and social measures with lineage dynamics of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2305403120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lustig Y., Sapir E., Regev-Yochay G., Cohen C., Fluss R., Olmer L., Indenbaum V., Mandelboim M., Doolman R., Amit S., et al. BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine and correlates of humoral immune responses and dynamics: a prospective, single-centre, longitudinal cohort study in health-care workers. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021;9:999–1009. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(21)00220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earle K.A., Ambrosino D.M., Fiore-Gartland A., Goldblatt D., Gilbert P.B., Siber G.R., Dull P., Plotkin S.A. Evidence for antibody as a protective correlate for COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine. 2021;39:4423–4428. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert P.B., Montefiori D.C., McDermott A.B., Fong Y., Benkeser D., Deng W., Zhou H., Houchens C.R., Martins K., Jayashankar L., et al. Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Science. 2022;375:43–50. doi: 10.1126/science.abm3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoury D.S., Cromer D., Reynaldi A., Schlub T.E., Wheatley A.K., Juno J.A., Subbarao K., Kent S.J., Triccas J.A., Davenport M.P. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2021;27:1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt P., Narayan K., Li Y., Kaku C.I., Brown M.E., Champney E., Geoghegan J.C., Vásquez M., Krauland E.M., Yockachonis T., et al. Antibody-mediated protection against symptomatic COVID-19 can be achieved at low serum neutralizing titers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023;15 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adg2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldblatt D., Alter G., Crotty S., Plotkin S.A. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease. Immunol. Rev. 2022;310:6–26. doi: 10.1111/imr.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei J., Pouwels K.B., Stoesser N., Matthews P.C., Diamond I., Studley R., Rourke E., Cook D., Bell J.I., Newton J.N., et al. Antibody responses and correlates of protection in the general population after two doses of the ChAdOx1 or BNT162b2 vaccines. Nat. Med. 2022;28:1072–1082. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01721-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora R.K., Joseph A., Van Wyk J., Rocco S., Atmaja A., May E., Yan T., Bobrovitz N., Chevrier J., Cheng M.P., et al. SeroTracker: a global SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence dashboard. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021;21:e75–e76. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30631-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X., Chen Z., Azman A.S., Sun R., Lu W., Zheng N., Zhou J., Wu Q., Deng X., Zhao Z., et al. Neutralizing antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants induced by natural infection or vaccination: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022;74:734–742. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranjeva S., Subramanian R., Fang V.J., Leung G.M., Ip D.K.M., Perera R.A.P.M., Peiris J.S.M., Cowling B.J., Cobey S. Age-specific differences in the dynamics of protective immunity to influenza. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1660. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09652-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minter A., Hoschler K., Jagne Y.J., Sallah H., Armitage E., Lindsey B., Hay J.A., Riley S., de Silva T.I., Kucharski A.J. Estimation of seasonal influenza attack rates and antibody dynamics in children using cross-sectional serological data. J. Infect. Dis. 2022;225:1750–1754. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsang T.K., Perera R.A.P.M., Fang V.J., Wong J.Y., Shiu E.Y., So H.C., Ip D.K.M., Malik Peiris J.S., Leung G.M., Cowling B.J., Cauchemez S. Reconstructing antibody dynamics to estimate the risk of influenza virus infection. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1557. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kucharski A.J., Lessler J., Cummings D.A.T., Riley S. Timescales of influenza A/H3N2 antibody dynamics. PLoS Biol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsang T.K., Ghebremariam S.L., Gresh L., Gordon A., Halloran M.E., Katzelnick L.C., Rojas D.P., Kuan G., Balmaseda A., Sugimoto J., et al. Effects of infection history on dengue virus infection and pathogenicity. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1246. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09193-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X., Ning Y., Chen M.I.-C., Cook A.R. Individual and population trajectories of influenza antibody titers over multiple seasons in a tropical country. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018;187:135–143. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hay J.A., Minter A., Ainslie K.E.C., Lessler J., Yang B., Cummings D.A.T., Kucharski A.J., Riley S. An open source tool to infer epidemiological and immunological dynamics from serological data: Serosolver. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salje H., Cummings D.A.T., Rodriguez-barraquer I., Katzelnick L.C., Lessler J., Klungthong C., Thaisomboonsuk B., Nisalak A., Weg A., Ellison D., et al. Reconstruction of antibody dynamics and infection histories to evaluate dengue risk. Nature. 2018;557:719–723. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0157-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hay J., Routledge I., Takahashi S. A primer and synthetic review of methods for epidemiological inference using serological data. Epidemics. 2004;49:100806. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2024.100806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrie J.G., Pattinson D., King J.P., Neumann G., Guan L., Jester P., Rolfes M.A., Meece J.K., Kieke B.A., Belongia E.A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 incidence, seroprevalence, and antibody dynamics in a rural, population-based cohort: March 2020 – July 2022. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2025;194:1574–1583. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwae125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC COVID-19 Response Team SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant — United States, December 1–8, 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:1731–1734. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White M.T., Bejon P., Olotu A., Griffin J.T., Bojang K., Lusingu J., Salim N., Abdulla S., Otsyula N., Agnandji S.T., et al. A combined analysis of immunogenicity, antibody kinetics and vaccine efficacy from phase 2 trials of the RTS,S malaria vaccine. BMC Med. 2014;12:117. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0117-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White M.T., Griffin J.T., Akpogheneta O., Conway D.J., Koram K.A., Riley E.M., Ghani A.C. Dynamics of the antibody response to plasmodium falciparum infection in African children. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;210:1115–1122. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amanna I.J., Slifka M.K. Mechanisms that determine plasma cell lifespan and the duration of humoral immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2010;236:125–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.2010.00912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le D., Miller J.D., Ganusov V.V. Mathematical modeling provides kinetic details of the human immune response to vaccination. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014;4:177. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Townsend J.P., Hassler H.B., Sah P., Galvani A.P., Dornburg A. The durability of natural infection and vaccine-induced immunity against future infection by SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2204336119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amodio E., Capra G., Casuccio A., Grazia S.D., Genovese D., Pizzo S., Calamusa G., Ferraro D., Giammanco G.M., Vitale F., Bonura F. Antibodies responses to SARS-CoV-2 in a large cohort of vaccinated subjects and seropositive patients. Vaccines. 2021;9:714. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amanat F., Stadlbauer D., Strohmeier S., Nguyen T.H.O., Chromikova V., McMahon M., Jiang K., Arunkumar G.A., Jurczyszak D., Polanco J., et al. A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1033–1036. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0913-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.COVID-19: Wisconsin Wastewater Monitoring Program Wisconsin Department of Health Services. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/wastewater.htm.

- 33.Buitrago-Garcia D., Egli-Gany D., Counotte M.J., Hossmann S., Imeri H., Ipekci A.M., Salanti G., Low N. Occurrence and transmission potential of asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oran D.P., Topol E.J. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;173:M20–M3012. doi: 10.7326/m20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamayoshi S., Yasuhara A., Ito M., Akasaka O., Nakamura M., Nakachi I., Koga M., Mitamura K., Yagi K., Maeda K., et al. Antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 decline, but do not disappear for several months. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;32 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Röltgen K., Powell A.E., Wirz O.F., Stevens B.A., Hogan C.A., Najeeb J., Hunter M., Wang H., Sahoo M.K., Huang C., et al. Defining the features and duration of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with disease severity and outcome. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shrotri M., Fragaszy E., Nguyen V., Navaratnam A.M.D., Geismar C., Beale S., Kovar J., Byrne T.E., Fong W.L.E., Patel P., et al. Spike-antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccination by demographic and clinical factors in a prospective community cohort study. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5780. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33550-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J.S., Sun Y., Balte P., Cushman M., Boyle R., Tracy R.P., Styer L.M., Bell T.D., Anderson M.R., Allen N.B., et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 spike 1 antibody response among vaccinated US adults: the C4R study. Nat. Commun. 2024;15:1492. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-45468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]