Abstract

MmpL3 is a promising new target for antitubercular drugs, but the microbiological properties of MmpL3 inhibitors are not fully understood. We compared the activity and mode of action of 11 structurally diverse compound series that target MmpL3. We confirmed the activity was via MmpL3 using strains with differential expression of MmpL3. MmpL3 inhibitors had potent activity against replicating M. tuberculosis, with increased activity against intramacrophage bacilli and were rapidly bactericidal. MmpL3 inhibition induced cell wall stress concomitantly with a boost in the ATP levels in M. tuberculosis. Mutation in MmpL3 conferred resistance to all series at different levels. The molecules did not negatively impact membrane potential, pH homeostasis, or induce reactive oxygen species and were inactive against starved bacilli. Our study revealed common features related to the chemical inhibition of MmpL3, enabling the identification of off-target effects and highlighting the potential of such compounds as future drug candidates.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, MmpL3, mutations, cell wall, tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a leading cause of mortality due to a single infectious disease, causing 10.8 million active infections and 1.25 million deaths in 2023. Current treatment regimens for TB infections are lengthy, requiring four antibiotics to be taken for four to six months. Drug-resistant infections, accounting for 400,000 infections in 2023, require an extended treatment time of up to 24 months with second-line drugs. Many of the existing TB drugs are associated with adverse effects including visual impairment, hepatotoxicity, neuropathy, and QTc prolongation. − To improve treatment outcomes, there is an urgent need for more effective drugs that shorten treatment times with fewer adverse effects. Identifying compounds with new targets is a key to this goal.

Mycobacterium tuberculosi s, the causative agent of TB, has a thick cell wall that is vital for survival in the host environment. The cell wall consists of a highly hydrophobic layer of mycolic acids linked to arabinogalactan, which forms an impermeable barrier to many antibiotics and is vital for adaptation to the host environment. Preventing M. tuberculosis from maintaining its cell wall by treating with cell wall synthesis inhibitors, isoniazid and ethambutol, − has already proven effective in current TB treatment regimens. As a result, there is great interest in the discovery of compounds with other cell wall targets such as MmpL3. MmpL3 is the sole transporter of mycolic acids in M. tuberculosis. It uses the proton motive force (PMF) to transfer TMM (trehalose monomycolate) across the inner membrane to the periplasmic space, where it is incorporated into the mycolic acid layer by the Ag85 complex. −

MmpL3 is an attractive drug target since it is unique to Mycobacteria sp., is required for survival in macrophages, , for virulence and persistence in murine models of infection and its inhibition results in rapid cell death. ,− Numerous chemical scaffolds targeting MmpL3 have been described but none have reached approval for clinical use. SQ109 is the furthest in development and has reached clinical trials − but may not be suitable for clinical use and likely has additional targets. −

Studies into the activity and mode of action of MmpL3 inhibitors have been confounded by the off-target effects of some of the most well-studied candidates. For example, SQ109 and BM212 appear to disrupt the PMF, , while others do not. SQ109 is active against M. tuberculosis in low oxygen, whereas AU1235 and THPP-2 are inactive. In addition, the fact that these molecules have been studied in different laboratories under different experimental conditions complicates a direct comparison of the activity. Understanding the biology of MmpL3 inhibitors is important in considering how drugs targeting this protein could be used in a multidrug treatment regimen (Table ).

1. Activity of Compounds against M. tuberculosis .

| Extracellular |

MBC (μM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series | Compound | IC90 (μM) | IC50 (μM) | Intramacrophage IC50 (μM) | Medium | Starvation |

| 7-aza | 1 | 0.061 | 0.050 | 0.014 | <0.20 | 100 |

| 2 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.024 | <0.39 | >100 | |

| 3 | 0.17 | 0.061 | 0.022 | <0.20 | 25 | |

| DDU01 | 4 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.62 | 2.4 | >100 |

| 5 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 6.2 | 9.4 | >100 | |

| 6 | 0.19 | 0.094 | 0.057 | <0.39 | >100 | |

| ICA | 7 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.016 | <0.20 | >100 |

| 8 | 0.029 | 0.017 | 0.0060 | <0.20 | >100 | |

| 9 | 0.071 | 0.038 | 0.0094 | <0.20 | >75 | |

| DDU02 | 10 | 32 | 10 | 6.0 | 25 | >100 |

| 11 | 8.6 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 13 | >100 | |

| 12 | 13 | 5.7 | 1.2 | 9.4 | 100 | |

| DDU03 | 13 | 11 | 9.5 | 2.0 | 13 | 75 |

| 14 | 8.3 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 7.8 | >100 | |

| 15 | 20 | 9.2 | 5.7 | 27 | >100 | |

| DDU04 | 16 | 12 | 6.0 | 3.4 | 6.3 | 25 |

| 17 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 50 | |

| 18 | 15 | 7.6 | 4.8 | 13 | >100 | |

| DDU05 | 19 | 8.9 | 4.1 | 12 | 38 | >100 |

| 20 | 6.1 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 9.4 | >100 | |

| 21 | 4.8 | 1.3 | 3.9 | >100 | >100 | |

| Oxazole | 22 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.060 | <0.39 | >100 |

| 23 | 0.078 | 0.061 | 0.017 | <0.20 | >100 | |

| 24 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.062 | 1.2 | >75 | |

| Pyrazole | 25 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.024 | <0.39 | 100 |

| 26 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 0.27 | 1.6 | >100 | |

| ARI | 27 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.063 | 0.78 | >100 |

| 28 | 1.1 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 1.6 | >100 | |

| 29 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 0.19 | 3.1 | >100 | |

| Thiazole | 30 | 0.18 | 0.044 | 0.019 | <0.20 | >100 |

| 31 | 0.19 | 0.081 | 0.051 | <0.20 | >100 | |

| 32 | 0.088 | 0.053 | 0.0057 | <0.20 | >100 | |

| AU1235 | - | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.063 | 0.59 | >100 |

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP growth was measured after compound exposure for 5 days in axenic culture (extracellular) or infected THP-1 cells (intramacrophage). Bactericidal activity of compounds against M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP under replicating conditions (medium) and nonreplicating conditions (starvation) after 14 days of exposure. Values show the geometric mean of at least two independent experiments to 2 s.f.

To understand the microbiological properties of MmpL3 inhibitors, we collected a set of structurally diverse compounds that target MmpL3 and simultaneously compared their activity against M. tuberculosis, their mechanism of action, and their interaction with MmpL3 mutant strains. Our study revealed a common set of features across MmpL3 inhibitors, some of which make these compounds promising drug candidates.

Results and Discussion

Compound Selection

The goal of our study was to understand the microbiological effects of chemical MmpL3 inhibition in M. tuberculosis. To avoid identifying effects related to specific chemical scaffolds, we used 11 chemically diverse compound series as a tool for our study (Figure ). All 11 series originated from phenotypic hits identified in whole cell M. tuberculosis screens of chemical libraries (unpublished data) except for the pyrazole series, which were derived from the previously described BM212 scaffold to improve its drug-like properties. The selected series encompass varying stages of drug discovery in which activity against M. tuberculosis and drug-like properties are optimized. The DDU01, DDU02, DDU03, DDU04, and DDU05 series were early in discovery (hit assessment), in which some structure–activity relationship exploration had been performed. The indolecarboxamide (ICA) series were the furthest progressed (preclinical candidate declaration) of the 11 series; activity and drug-like properties have been well optimized, and compounds have proven efficacy in mouse models of infection. The remaining series, pyrazole, ARI, 7-aza, oxazole, and thiazole, were in midstage discovery (hit-to-lead or lead optimization). Two to three compounds representing each of the 11 series were selected for our study (Figure ; compounds 1–32). AU1235 was included as a reference since it is a well-characterized MmpL3 inhibitor with no known secondary targets. ,

1.

Chemical structures of MmpL3 inhibitors included in the study. Molecules are grouped by compound series. Page 20 of 25 ACS Paragon Plus Environment ACS Infectious Diseases 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54.

Compound Series Target MmpL3

To confirm MmpL3 as the target, compound activity was measured in M. tuberculosis strains with altered MmpL3 expression. The mmpL3-TetON strain was used, in which MmpL3 expression is regulated by anhydrotetracycline (ATc). In the absence of ATc, expression of the MmpL3 protein is decreased by 80% and the mmpL3-TetON strain is more susceptible to MmpL3 inhibitors such as AU1235 (Figure ). Similarly, compounds across all 11 series were 2- to 6-fold more active against the mmpL3-TetON strain in the absence of ATc relative to the wild-type H37Rv (Figure ). In the presence of ATc, MmpL3 expression in the mmpL3-TetON strain is increased by more than 7-fold. Interestingly, MmpL3 overexpression conferred resistance to only a subset of the MmpL3 inhibitor compounds in our study and did not confer resistance to AU1235, a well-established MmpL3 inhibitor (Figure ). Overall, altered activity against strains with differential MmpL3 expression is consistent with MmpL3 being the target of our compound series. Ethambutol was used as a negative control since MmpL3 underexpression does not affect sensitivity (Figure ).

2.

Differential expression of MmpL3 alters the susceptibility to compounds. H37Rv (black circles) and the mmpL3-TetON strain with ATc (gray filled squares) or without ATc (gray empty squares) were exposed to compounds for up to 14 days. OD580 was read. Plots show the mean and standard error for three independent experiments.

MmpL3 Mutations Confer Resistance

Mutations in the M. tuberculosis mmpL3 gene confer resistance to a broad range of MmpL3 inhibitors. ,− Most MmpL3 inhibitors, including AU1235, SQ109, and NITD-349, bind in the same pocket site and induce a conformational change in the MmpL3 protein structure that disrupts the two Asp-Tyr pairs required for proton transport. To further confirm MmpL3 as the target of our compounds, we looked for resistance using an M. tuberculosis MmpL3 mutant strain, RM301 (MmpL3F255L,V646M,F644I). This strain was generated via multiple rounds of selection for resistance to different MmpL3 inhibitors and has been shown to confer resistance to structurally diverse MmpL3 inhibitor scaffolds. The RM301 strain was >4-fold more resistant to most of our compounds relative to wild-type H37Rv-LP (25 out of 32 compounds; Table ), consistent with MmpL3 being the primary target. RM301 was most resistant to the 7-aza series; activity against compound 1 was reduced >1639-fold relative to wild-type (Table ). Of note, the RM301 strain conferred varying levels of resistance between the series, suggesting the various chemical scaffolds represented in our compound set may have different interactions or binding affinities with MmpL3 (Table ). However, mutations in the RM301 strain did not confer resistance to pyrazole or DDU05 series compounds; therefore, we selected compound 26 and tested its activity against another MmpL3 mutant strain, MmpL3S591I. This strain was 23-fold more resistant to compound 26 relative to wild-type (Table ) suggesting this chemical structure may have a different mode of MmpL3 protein binding to the other series.

2. Compound Activity against M. tuberculosis MmpL3 Mutant Strains .

| WT |

MmpL3F255L,V646M,F644I

|

MmpL3S591I

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series | Compound | IC90 (μM) | IC90 (μM) | Fold change | IC90 (μM) | Fold change |

| 7-aza | 1 | 0.061 | >100 | >1639 | - | - |

| 2 | 0.14 | >13 | >93 | - | - | |

| 3 | 0.17 | >50 | >294 | - | - | |

| DDU01 | 4 | 2.0 | >20 | >10 | - | - |

| 5 | 5.5 | >100 | >18 | - | - | |

| 6 | 0.19 | >100 | >526 | - | - | |

| ICA | 7 | 0.024 | 1.3 | 54 | - | - |

| 8 | 0.029 | >2.5 | >86 | - | - | |

| 9 | 0.071 | >5.0 | >70 | - | - | |

| DDU02 | 10 | 32 | >100 | >3 | - | - |

| 11 | 8.6 | >100 | >11 | - | - | |

| 12 | 13 | >95 | >7 | - | - | |

| DDU03 | 13 | 11 | >20 | >1.8 | - | - |

| 14 | 8.3 | >100 | >12 | - | - | |

| 15 | 20 | >100 | >5 | - | - | |

| DDU04 | 16 | 12 | >20 | >1.7 | - | - |

| 17 | 3.0 | >20 | >6.7 | - | - | |

| 18 | 15 | >100 | >6.7 | - | - | |

| DDU05 | 19 | 8.9 | 9.6 | 1.1 | - | - |

| 20 | 6.1 | 2.3 | 0.38 | - | - | |

| 21 | 4.8 | 7.1 | 1.5 | - | - | |

| Oxazole | 22 | 0.48 | 13 | 27 | - | - |

| 23 | 0.078 | 5.1 | 65 | - | - | |

| 24 | 0.62 | >100 | >161 | - | - | |

| Pyrazole | 25 | 0.27 | 0.64 | 2.4 | - | - |

| 26 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.96 | 52 | 23 | |

| ARI | 27 | 0.58 | 9.5 | 16 | - | - |

| 28 | 1.1 | >20 | >18 | - | - | |

| 29 | 2.3 | 12 | 5.2 | - | - | |

| Thiazole | 30 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 5.1 | - | - |

| 31 | 0.19 | >100 | >526 | - | - | |

| 32 | 0.088 | 3.0 | 34 | - | - | |

| AU1235 | - | 0.22 | >100 | 454 | 6.0 | 27 |

Inhibition of growth was measured after 5 days exposure to the compound. IC90 values show the geometric mean of at least two independent experiments to 2 s.f.. Fold change was calculated relative to WT IC90.

MmpL3 Inhibitors Inhibit Growth of M. tuberculosis

We measured the MICs (minimum inhibitory concentrations) of our compounds against M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP after 5 days in standard growth medium. All compounds inhibited the growth of M. tuberculosis, some with excellent potency (IC90 < 1 μM) (Table ). Compounds 7, 8, and 9 from the ICA series were the most active with an IC90 of 0.024, 0.029, and 0.071 μM respectively (Table ). Compounds from the DDU02, DDU03, and DDU04 series were the least potent; compound 10 had the highest IC90 of 32 μM (Table ). In general, compound activity correlated with the stage in discovery as compounds in later stages of discovery were more potent than those in early discovery.

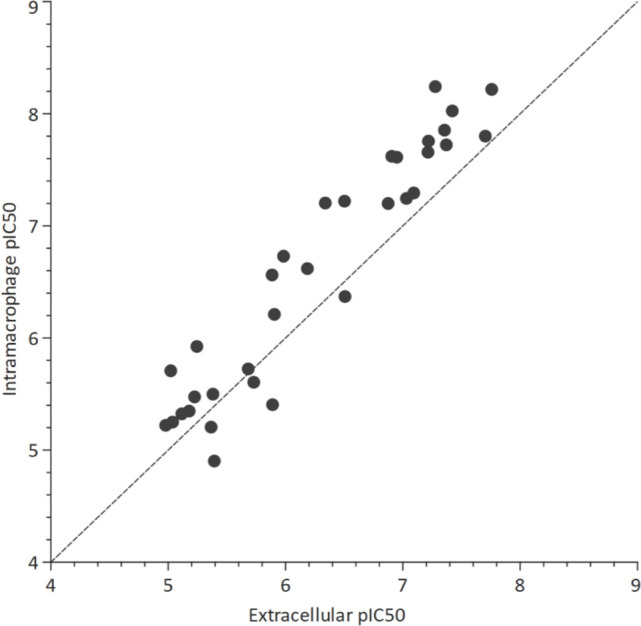

MmpL3 Inhibitors Have Enhanced Activity against Intracellular Bacteria

We measured the activity of compounds against intramacrophage M. tuberculosis. Differentiated THP-1 cells were infected with M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP and exposed to compound for 3 days. We found that all compounds across all 11 series, as well as AU1235, strongly inhibited the growth of intramacrophage M. tuberculosis (Table ). As with extracellular activity, compound activity correlated with the stage in discovery. The ICA series was the most potent; the intramacrophage IC50 for compounds 7, 8, and 9 was 0.063, 0.0060, and 0.0094 μM respectively (Table ). Compound 19 from the DDU05 series was the least potent with an intramacrophage IC50 of 12 μM (Table ). Comparison of intramacrophage and extracellular activity revealed that most compounds, including AU1235, were up to 10-fold more active against M. tuberculosis (Figure ). The increased potency against intramacrophage M. tuberculosis was observed across chemically distinct compound series, so it is likely a feature of MmpL3 inhibition rather than an effect related to a particular chemical structure.

3.

Activity of compounds against M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP in an axenic culture (extracellular) and infected THP-1 cells (intramacrophage). Points represent the geometric mean of at least two independent replicates. The dotted line shows y = x.

MmpL3 Inhibitors Are Bactericidal against Replicating M. tuberculosis

We next compared the bactericidal activities of the compounds. The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined after 14 days of exposure to compound in standard growth medium, in which the bacilli are in a replicating state. Almost all compounds were bactericidal against M. tuberculosis in this condition, a number of which were bactericidal at submicromolar concentrations (Table ). Compounds from the Thiazole and ICA series had the most potent bactericidal activity with an MBC of less than 0.2 μM (the lowest concentration tested) (Table ). DDU05 series compound 21 was the only compound for which no bactericidal activity against replicating bacteria was observed up to 100 μM (the highest concentration tested) (Table ). Across all series, the concentration required for bactericidal activity (MBC) was very close to the inhibitory concentration (IC90; Table ). Such potent bactericidal activity is an unusual but promising property for antimicrobial compounds.

Since M. tuberculosis can also exist in a nonreplicating state in the host, we looked for bactericidal activity against M. tuberculosis cells starved for 7 days prior to compound exposure. All compounds, including AU1235, had little or no bactericidal activity against starved cells at the concentrations tested (up to 100 μM; Table ). Thus, in contrast to previous studies using SQ109, we found that MmpL3 inhibitors are not active against bacteria in a nonreplicating state. This was not surprising since the synthesis of the mycolic acid layer, and therefore mycolic acid export, is less important in cells that are not growing. However, the different methods used to induce a nonreplicating state (low oxygen compared to nutrient starvation) between studies should be considered.

MmpL3 Inhibitors Induce Cell Wall Stress

To confirm the mode of action of MmpL3 inhibitors and to identify any molecules with secondary targets, we ran all compounds through a series of assays testing their effects on different biological pathways. We first measured the induction of cell wall stress using an M. tuberculosis reporter strain in which luciferase expression is controlled by the iniB promoter, which is induced by cell wall stress. As anticipated for inhibitors of mycolic acid transport, all compounds induced the PiniB reporter indicating cell wall stress (Figure ). Test compounds induced the reporter at similar levels to ethambutol, an inhibitor of cell wall arabinogalactan synthesis. , Reporter signal was strongest around the IC50 for each compound linking compound activity to the induction of cell wall stress.

4.

MmpL3 inhibitors induce cell wall stress. A M. tuberculosis strain expressing a luciferase operon under the control of the cell wall stress-induced iniB promoter was exposed to compounds, and luminescence (RLU) was measured. Ethambutol was used as a positive control. Plots show one of at least two independent experiments. Dotted vertical lines represent the IC50.

MmpL3 Inhibitors Cause Increased ATP Levels

We measured intracellular ATP following compound exposure. All compounds caused substantial increases in ATP levels in our assay (Figure ). This increase occurred at the concentration required to inhibit bacterial growth, directly linking chemical MmpL3 inhibition to the elevated ATP levels detected. Q203, a QcrB inhibitor, was used as a control for ATP depletion and demonstrated the expected decrease in ATP levels at subinhibitory concentrations. Kanamycin exposure (negative control) led to a drop in ATP levels concomitant with decreased growth.

5.

MmpL3 inhibitors induce an ATP boost. M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP was exposed to compounds and ATP levels were measured after 24 h by the addition of BacTiter-Glo reagent and reading luminescence (RLU). OD590 was measured after 5 days. Q203 was used as a positive control (ATP depletion), and kanamycin was used as a negative control (no effect). Plots show one representative of at least two independent replicates.

The increase in ATP levels in response to MmpL3 inhibition has not been previously described in M. tuberculosis. However, our finding is consistent with studies in other Mycobacteria sp., such as Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium bovis BCG, where treatment with cell wall inhibitors leads to increased ATP concentrations, , suggesting that the ATP increase could be a general response to cell wall perturbations in Mycobacterium species. Alternatively, it is possible that the observed ATP increase is an artifact of more efficient cell lysis by the BacTiter-Glo reagent due to a weakened cell wall. Further work is required to understand the mechanistic link between cell wall inhibition and increased ATP levels in Mycobacterium sp.

MmpL3 Inhibitors to Do Not Affect ROS, Membrane Potential, or pH Homeostasis

Compounds were also tested for their effects on reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, dissipation of membrane potential, and disruption of intracellular pH to look for any off-target effects. ROS were quantified using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA), an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye with econazole used as a positive control. Changes in membrane potential were detected using the fluorescent probe 3,3′-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC2(3)) with CCCP, an ionophore, as a positive control. The ability to maintain intracellular pH was tested using M. tuberculosis expressing a pH-dependent ratiometric GFP. In general, none of the compounds induced ROS, or disrupted membrane potential, or pH homeostasis (Figures and S1 – S3). The exceptions were compound 24 from the oxazole series and compound 20 from the DDU05 series, which induced intracellular alkalinization (Figures and S2), suggesting these molecules have a secondary target. Our finding that structurally diverse MmpL3 inhibitors do not dissipate membrane potential suggests that the effect SQ109 has on membrane potential , is structure specific, perhaps as a consequence of a second target rather than MmpL3 inhibition.

6.

MmpL3 inhibitors do not induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, disrupt membrane potential, or intracellular pH maintenance. M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP was exposed to compounds. ROS was quantified using the oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) and fluorescence measured at Ex485/Em535 nm (RFU). Membrane potential was measured using cells stained with the fluorescent probe 3,3′-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC2(3)) and calculating the ratio between Ex488/Em530 nm and Ex488/Em530 nm fluorescence reads. Intracellular pH was measured using an M. tuberculosis strain expressing a ratiometric GFP. Fluorescence was read at Ex390/Em505 and Ex475/Em510 nm and the ratio was calculated. Intracellular pH was interpolated using a standard curve. Dotted lines represent the limit of intracellular pH measurement. Plots show one representative of at least two independent experiments.

Taken together, our assays confirmed the mode of action of MmpL3 inhibitors, which induced cell wall stress and increased ATP levels. Changes in membrane potential, pH homeostasis, and ROS are not a general feature of MmpL3 inhibition, but rather off-target effects related to specific chemical scaffolds.

Conclusions

We performed a systematic comparison of 11 structurally diverse MmpL3 inhibitor series, in which 32 representative compounds were run in parallel through a set of biological assays aimed at increasing our understanding of their activity against M. tuberculosis, mode of action, and interaction with MmpL3 mutant strains. AU1235 was chosen as a reference for the study since there is no evidence for off-target activity, to our knowledge.

We confirmed MmpL3 as the target of our compounds by using MmpL3 mutant strains. The specificity of resistance to certain compound series in our study also suggests different modes of binding within the drug pocket. Further understanding of the global landscape of MmpL3 mutations and how they relate to resistance will be key to predicting clinical resistance to MmpL3 inhibitors in future treatment regimens.

Compounds from all 11 series behaved similarly to AU1235 in our study, highlighting a set of common biological features of MmpL3 inhibitors: a) potent growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis; b) bactericidal activity against replicating bacilli; c) increased potency against intramacrophage M. tuberculosis; d) induction of cell wall stress; and e) increased ATP. The identification of core biological features of MmpL3 inhibitors in this study has reinforced the potential of such compounds as antitubercular drugs. Many compounds had excellent bactericidal and inhibitory activity against M. tuberculosis. The contribution of these properties to treatment shortening warrants further study. It will also aid the identification of off-target activity in future drug discovery efforts and inform how such compounds may be used in combinatorial treatment regimens.

Methods

M. tuberculosis Culture

Unless otherwise stated, experiments were performed using M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP (ATCC 25618). M. tuberculosis strains were cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 medium plus 10% v/v Middlebrook OADC supplement and 0.05% w/v Tween 80 and incubated at 37 °C. For starvation, log-phase bacteria were harvested and resuspended in PBS plus 0.05 w/v % Tyloxapol and incubated for 7 d.

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

M. tuberculosis was grown to the log phase and inoculated to a final OD590 of 0.02 in 96-well plates containing compounds as 2-fold dilutions. Plates were incubated for 5 days at 37 °C. OD590 was read by using a Synergy H4 plate reader. Dose-response curves were fit using the variable Hill slope model from which IC50 and IC90 values, the concentrations at which 50% or 90% growth inhibition occurred, respectively, were determined.

Determination of Activity Using Recombinant Strains

The assay was performed as previously described. Briefly, the mmpL3-TetON strain was grown in 7H9 medium supplemented with 25 μg/mL kanamycin, 25 μg/mL zeocin, and ±500 ng/mL anhydrotetracycline (ATc). Cultures were diluted to an OD580 of 0.01 in medium ± ATc and 50 μL was dispensed into 384-well plates containing the compound. Plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. OD580 was read after 14 d incubation.

Determination of Activity against Intracellular Bacilli

THP-1 cells were obtained from ATCC (TIB-202) and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. THP-1 cells were differentiated by treatment with 80 nM PMA for 24 h prior to overnight infection with an M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP strain constitutively expressing luciferase from the pMV306hsp + LuxG13 plasmid at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1:1. Infected cells were harvested using Accumax solution, resuspended in fresh cRPMI and inoculated to a final density of 9 × 105 cells/mL in 96-well plates containing compounds. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 72 h. Luminescence was read by using a Synergy H4 plate reader. Dose-response curves were fit using the variable Hill slope model and the IC50 was determined.

Determination of Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP was grown to log phase and inoculated to a final OD590 of 0.02 in 96-well plates containing compounds as 2-fold dilutions. Plates were incubated at 37 °C. Samples were taken at 0, 7, and 14 days, spotted onto 7H10 agar plates, and incubated at 37 °C for 2 weeks. The MBC (minimum bactericidal concentration) was determined visually as the lowest concentration at which no growth was observed.

Determination of Intracellular ATP Levels

M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP was grown to late log phase and inoculated at OD590 0.04 in 96-well plates containing compounds as 2-fold dilutions. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. ATP was quantified by adding 50 μL of BacTiter-Glo reagent per well, incubating for 10 min, and reading luminescence using a Synergy H4 plate reader. Kanamycin and Q203 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Induction of Cell Wall Stress

The PiniB reporter assay was adapted from Alland et al., 2000. The M. tuberculosis PiniB-Lux strain, in which luciferase expression is controlled by the iniB promoter, was grown in GAST-Fe medium and inoculated to a final OD590 of 0.02 in 96-well plates containing compounds as 2-fold dilutions. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. A 100 μL of substrate solution (28 μg/mL D-luciferin, 50 mM DTT in 1 M HEPES buffer) was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 25 min at RT. Luminescence was read using a Synergy H4 plate reader. Ethambutol was used as a positive control.

Induction of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

ROS was measured as previously described. Briefly, M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP was grown to an OD590 of 1, resuspended in 7H9-Tw + 40 μM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells were washed, resuspended in fresh 7H9-Tw medium, and inoculated to a final OD590 of 0.5 in 96-well plates containing the compound. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 90 min and fluorescence at Ex485/Em535 nm was measured using a Synergy H4 plate reader. Econazole was used as a positive control.

Determination of Membrane Potential

M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP was grown to late log phase and adjusted to an OD590 of 1 in fresh medium. 3,3′-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC2) was added to a final concentration of 15 μM and incubated at RT for 20 min. Cells were harvested, resuspended in fresh medium, and inoculated to a final OD590 of 0.5 in 96-well plates containing compounds. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Fluorescence was read using an H4 Synergy plate reader at Ex488/Em530 and Ex488/Em610 nm. Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) was used as a positive control.

Determination of Intracellular pH Homeostasis

Intracellular pH was measured as previously described. Briefly, M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP expressing a pH-responsive ratiometric GFP (rGFP) from the pHLUOR plasmid was grown to late log phase, washed, and resuspended in phosphocitrate buffer at pH 4.5 (0.0896 M Na2HPO4, 0.0552 M citric acid, 0.05% tyloxapol). The culture was inoculated to a final OD590 of 0.3 into 96-well assay plates containing compounds in 2-fold dilutions. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Fluorescence was measured using an H4 Synergy plate reader at Ex395/Em510 and Ex475/Em510 nm. Monensin was used as a control. A standard curve was generated using cell-free extracts as follows: M. tuberculosis H37Rv-LP rGFP was lysed using a bead beater then passed through a 0.2 μm filter to obtain cell-free extracts. Cell-free extracts (10 μg/mL protein) were adjusted to pH 5.5 to 8.5 and fluorescence was measured to generate a ratio: the standard curve was fit using a four-parameter logistic model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nikki Nguyen, David (Zach) Wilkins, and Stephanie Jade Anover-Sombke for their technical assistance.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsinfecdis.5c00394.

Data describing the effect of all molecules on cellular processes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The effect of compounds on membrane potential, intracellular pH homeostasis and generation of reactive oxygen species. Figure S1: Compounds do not affect membrane potential. Figure S2: Compounds do not affect intracellular pH homeostasis. Figure S3: Compounds do not affect reactive oxygen species generation (PDF)

This work was supported in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Grant Numbers INV-056399, INV-004761, and INV-055896. Under the grant conditions of the foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission. Compounds from DDU01 to DDU05 were identified during work funded by FNIH (WYATT11HTB0 and WYAT17STB). This work was funded in part by the Division of Intramural Research of NIAID (NIH).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Global Tuberculosis Report, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Forget E. J., Menzies D.. Adverse Reactions to First-Line Antituberculosis Drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2006;5(2):231–249. doi: 10.1517/14740338.5.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezer N., Benedetti A., Darvish-Zargar M., Menzies D.. Incidence of Ethambutol-Related Visual Impairment during Treatment of Active Tuberculosis [Review Article] Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2013;17(4):447–455. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmetti L., Jaspard M., Le Dû D., Lachâtre M., Marigot-Outtandy D., Bernard C., Veziris N., Robert J., Yazdanpanah Y., Caumes E., Fréchet-Jachym M.. Long-Term Outcome and Safety of Prolonged Bedaquiline Treatment for Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2017;49(3):1601799. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01799-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulberger C. L., Rubin E. J., Boutte C. C.. The Mycobacterial Cell Envelope a Moving Target. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020;18(1):47–59. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A., Dubnau E., Quemard A., Balasubramanian V., Um K. S., Wilson T., Collins D., de Lisle G., Jacobs W. R.. inhA, a Gene Encoding a Target for Isoniazid and Ethionamide in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Science. 1994;263(5144):227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8284673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goude R., Amin A. G., Chatterjee D., Parish T.. The Arabinosyltransferase EmbC Is Inhibited by Ethambutol in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53(10):4138–4146. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00162-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenti A., Philipp W. J., Sreevatsan S., Bernasconi C., Stockbauer K. E., Wieles B., Musser J. M., Jacobs W. R.. The Emb Operon, a Gene Cluster of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Involved in Resistance to Ethambutol. Nat. Med. 1997;3(5):567–570. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Meshcheryakov V. A., Poce G., Chng S.-S.. MmpL3 Is the Flippase for Mycolic Acids in Mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114(30):7993–7998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700062114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C. M., Babii S. O., Pandya A. N., Li W., Li Y., Mehla J., Scott R., Hegde P., Prathipati P. K., Acharya A.. et al. Proton Transfer Activity of the Reconstituted Mycobacterium Tuberculosis MmpL3 Is Modulated by Substrate Mimics and Inhibitors. Proc. Int. Acad. Sci. 2022;119(30):e2113963119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2113963119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degiacomi G., Benjak A., Madacki J., Boldrin F., Provvedi R., Palù G., Kordulakova J., Cole S. T., Manganelli R.. Essentiality of mmpL3 and Impact of Its Silencing on Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Gene Expression. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):43495. doi: 10.1038/srep43495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C.-Y., McNeil M. B., Cook G. M.. Utilization of CRISPR Interference to Investigate the Contribution of Genes to Pathogenesis in a Macrophage Model of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022;77(3):615–619. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Obregón-Henao A., Wallach J. B., North E. J., Lee R. E., Gonzalez-Juarrero M., Schnappinger D., Jackson M.. Therapeutic Potential of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Mycolic Acid Transporter, MmpL3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60(9):5198–5207. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00826-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzegorzewicz A. E., Pham H., Gundi V. A. K. B., Scherman M. S., North E. J., Hess T., Jones V., Gruppo V., Born S. E. M., Korduláková J., Chavadi S. S., Morisseau C., Lenaerts A. J., Lee R. E., McNeil M. R., Jackson M.. Inhibition of Mycolic Acid Transport across the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Plasma Membrane. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8(4):334–341. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil M. B., Cook G. M.. Utilization of CRISPR Interference To Validate MmpL3 as a Drug Target in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;63(8):e00629-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00629-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North E. J., Schwartz C. P., Zgurskaya H. I., Jackson M.. Recent Advances in Mycobacterial Membrane Protein Large 3 Inhibitor Drug Design for Mycobacterial Infections. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2023;18(7):707–724. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2023.2218082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahlan K., Wilson R., Kastrinsky D. B., Arora K., Nair V., Fischer E., Barnes S. W., Walker J. R., Alland D., Barry C. E., Boshoff H. I.. SQ109 Targets MmpL3, a Membrane Transporter of Trehalose Monomycolate Involved in Mycolic Acid Donation to the Cell Wall Core of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56(4):1797–1809. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05708-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich N., Dawson R., Du Bois J., Narunsky K., Horwith G., Phipps A. J., Nacy C. A., Aarnoutse R. E., Boeree M. J., Gillespie S. H., Venter A., Henne S., Rachow A., Phillips P. P. J., Hoelscher M., Diacon A. H., Mekota A. M., Heinrich N., Rachow A., Saathoff E., Hoelscher M., Gillespie S., Colbers A., Van Balen G. P., Aarnoutse R., Boeree M., Bateson A., McHugh T., Singh K., Hunt R., Zumla A., Nunn A., Phillips P., Rehal S., Dawson R., Narunsky K., Diacon A., Du Bois J., Venter A., Friedrich S., Sanne I., Mellet K., Churchyard G., Charalambous S., Mwaba P., Elias N., Mangu C., Rojas-Ponce G., Mtafya B., Maboko L., Minja L. T., Sasamalo M., Reither K., Jugheli L., Sam N., Kibiki G., Semvua H., Mpagama S., Alabi A., Adegnika A. A., Amukoye E., Okwera A.. on behalf of the Pan African Consortium for the Evaluation of Antituberculosis Antibiotics (PanACEA);Early Phase Evaluation of SQ109 Alone and in Combination with Rifampicin in Pulmonary TB Patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015;70(5):1558–1566. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeree M. J., Heinrich N., Aarnoutse R., Diacon A. H., Dawson R., Rehal S., Kibiki G. S., Churchyard G., Sanne I., Ntinginya N. E., Minja L. T., Hunt R. D., Charalambous S., Hanekom M., Semvua H. H., Mpagama S. G., Manyama C., Mtafya B., Reither K., Wallis R. S., Venter A., Narunsky K., Mekota A., Henne S., Colbers A., Van Balen G. P., Gillespie S. H., Phillips P. P. J., Hoelscher M.. High-Dose Rifampicin, Moxifloxacin, and SQ109 for Treating Tuberculosis: A Multi-Arm, Multi-Stage Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017;17(1):39–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Upadhyay A., Fontes F. L., North E. J., Wang Y., Crans D. C., Grzegorzewicz A. E., Jones V., Franzblau S. G., Lee R. E., Crick D. C., Jackson M.. Novel Insights into the Mechanism of Inhibition of MmpL3, a Target of Multiple Pharmacophores in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58(11):6413–6423. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03229-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Zhu W., Schurig-Briccio L. A., Lindert S., Shoen C., Hitchings R., Li J., Wang Y., Baig N., Zhou T.. et al. Antiinfectives Targeting Enzymes and the Proton Motive Force. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112(51):E7073–E7082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521988112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malwal S. R., Mazurek B., Ko J., Xie P., Barnes C., Varvitsiotis C., Zimmerman M. D., Olatunji S., Lee J., Xie M., Sarathy J., Caffrey M., Strynadka N. C. J., Dartois V., Dick T., Lee B. N. R., Russell D. G., Oldfield E.. Investigation into the Mechanism of Action of the Tuberculosis Drug Candidate SQ109 and Its Metabolites and Analogues in Mycobacteria. J. Med. Chem. 2023;66(11):7553–7569. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poce G., Consalvi S., Venditti G., Alfonso S., Desideri N., Fernandez-Menendez R., Bates R. H., Ballell L., Barros Aguirre D., Rullas J., De Logu A., Gardner M., Ioerger T. R., Rubin E. J., Biava M.. Novel Pyrazole-Containing Compounds Active against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;10(10):1423–1429. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stec J., Onajole O. K., Lun S., Guo H., Merenbloom B., Vistoli G., Bishai W. R., Kozikowski A. P.. Indole-2-Carboxamide-Based MmpL3 Inhibitors Show Exceptional Antitubercular Activity in an Animal Model of Tuberculosis Infection. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59(13):6232–6247. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S., Engelhart C. A., Pérez-Herrán E., Li W., Abrahams K. A., Papavinasasundaram K., Bean J. M., Sassetti C. M., Mendoza-Losana A., Besra G. S., Jackson M., Schnappinger D.. Two-Way Regulation of MmpL3 Expression Identifies and Validates Inhibitors of MmpL3 Function in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . ACS Infect. Dis. 2021;7(1):141–152. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remuiñán M. J., Pérez-Herrán E., Rullás J., Alemparte C., Martínez-Hoyos M., Dow D. J., Afari J., Mehta N., Esquivias J., Jiménez E., Ortega-Muro F., Fraile-Gabaldón M. T., Spivey V. L., Loman N. J., Pallen M. J., Constantinidou C., Minick D. J., Cacho M., Rebollo-López M. J., González C., Sousa V., Angulo-Barturen I., Mendoza-Losana A., Barros D., Besra G. S., Ballell L., Cammack N.. Tetrahydropyrazolo[1,5-a]Pyrimidine-3-Carboxamide and N-Benzyl-6′,7′-DihydrospiroPiperidine-4,4′-Thieno3,2-c]Pyran] Analogues with Bactericidal Efficacy against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Targeting MmpL3. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Stevens C. M., Pandya A. N., Darzynkiewicz Z., Bhattarai P., Tong W., Gonzalez-Juarrero M., North E. J., Zgurskaya H. I., Jackson M.. Direct Inhibition of MmpL3 by Novel Antitubercular Compounds. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019;5(6):1001–1012. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil M. B., O’Malley T., Dennison D., Shelton C. D., Sunde B., Parish T.. Multiple Mutations in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis MmpL3 Increase Resistance to MmpL3 Inhibitors. mSphere. 2020;5(5):e00985-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00985-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Li J., Yang X., Wu L., Zhang J., Yang Y., Zhao Y., Zhang L., Yang X., Yang X.. et al. Crystal Structures of Membrane Transporter MmpL3, an Anti-TB Drug Target. Cell. 2019;176(3):P636–648.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naran K., Moosa A., Barry C. E., Boshoff H. I. M., Mizrahi V., Warner D. F.. Bioluminescent Reporters for Rapid Mechanism of Action Assessment in Tuberculosis Drug Discovery. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60(11):6748–6757. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01178-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethe K., Bifani P., Jang J., Kang S., Park S., Ahn S., Jiricek J., Jung J., Jeon H. K., Cechetto J., Christophe T., Lee H., Kempf M., Jackson M., Lenaerts A. J., Pham H., Jones V., Seo M. J., Kim Y. M., Seo M., Seo J. J., Park D., Ko Y., Choi I., Kim R., Kim S. Y., Lim S., Yim S.-A., Nam J., Kang H., Kwon H., Oh C.-T., Cho Y., Jang Y., Kim J., Chua A., Tan B. H., Nanjundappa M. B., Rao S. P. S., Barnes W. S., Wintjens R., Walker J. R., Alonso S., Lee S., Kim J., Oh S., Oh T., Nehrbass U., Han S.-J., No Z., Lee J., Brodin P., Cho S.-N., Nam K., Kim J.. Discovery of Q203, a Potent Clinical Candidate for the Treatment of Tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 2013;19(9):1157–1160. doi: 10.1038/nm.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty A., Dick T.. Mycobacterial Cell Wall Synthesis Inhibitors Cause Lethal ATP Burst. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1898. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindman M., Dick T.. Bedaquiline Eliminates Bactericidal Activity of β-Lactams against Mycobacterium Abscessus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;63(8):e00827. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00827-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell Wescott H. A., Roberts D. M., Allebach C. L., Kokoczka R., Parish T.. Imidazoles Induce Reactive Oxygen Species in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Which Is Not Associated with Cell Death. ACS Omega. 2017;2(1):41–51. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.6b00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early J., Ollinger J., Darby C., Alling T., Mullen S., Casey A., Gold B., Ochoada J., Wiernicki T., Masquelin T., Nathan C., Hipskind P. A., Parish T.. Identification of Compounds with pH-Dependent Bactericidal Activity against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019;5:272–280. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu N., Zelmer A., Fletcher T., Elkington P. T., Ward T. H., Ripoll J., Parish T., Bancroft G. J., Schaible U., Robertson B. D., Wiles S.. Optimisation of Bioluminescent Reporters for Use with Mycobacteria. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alland D., Steyn A. J., Weisbrod T., Aldrich K., Jacobs W. R. Jr. Characterization of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis iniBAC Promoter, a Promoter That Responds to Cell Wall Biosynthesis Inhibition. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182(7):1802–1811. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.7.1802-1811.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby C. M., Ingólfsson H. I., Jiang X., Shen C., Sun M., Zhao N., Burns K., Liu G., Ehrt S., Warren J. D., Anderson O. S., Brickner S. J., Nathan C.. Whole Cell Screen for Inhibitors of pH Homeostasis in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.